Dimitrios Konidaris's Blog, page 6

September 18, 2022

ASCSA AS A LONG ARM OF AMERICAN POLITICS & VEHICLE OF ANTIHELLENISM

Î ÏÏÏÏαÏα ÎºÏ ÎºÎ»Î¿ÏÏÏηÏε Ïο βιβλίο ΠΥÎÎΣ: ÎÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ ÎΡÎΤÎΣ ΥΠΠÎÎΤÎΣÎÎÎ¥ÎÎ (A Greek State in Formation: The Origins of Mycenaean Pylos) αÏÏ Ïον Jack L. Davis και με ÏÏ Î¼Î¼ÎµÏοÏή ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Î¶ÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Sharon R. Stocker.

Î ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎÎ±Ï Ï ÏήÏξε Î´Î¹ÎµÏ Î¸Ï Î½ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎμεÏÎ¹ÎºÎ±Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î£ÏÎ¿Î»Î®Ï ÎλαÏικÏν ΣÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ïν ÏÏην Îθήνα (ASCSA) καθÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏ Î½Î´Î¹ÎµÏ Î¸Ï Î½ÏÎ®Ï ÏÏν αναÏκαÏÏν ÏÏην Î Ïλο, Î¼Î±Î¶Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην ÏÏÎ¶Ï Î³Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Stocker, ÎµÎ½Ï Î±Î¼ÏÏÏεÏοι ÏιÏÏÏνονÏαι Ïην αναÏκαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÏα ΠολεμιÏÏή!η οÏοία ÏÏ Î¼Î¼ÎµÏείÏε και Το ÏÏολιαζÏμενο βιβλίο ÏεÏιλαμβάνει μιά ÏειÏά αÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏοκαλοÏν Ïον Îλληνα αναγνÏÏÏη και θα ÏÏολιαÏθοÏν εν ÏÏ Î½Ïομία ÏÏα εÏÏμενα. Τα αÏοÏÏάÏμαÏα ÏαÏαÏίθενÏαι καÏÏÏÎÏÏ, μεÏαÏÏαÏμÎνα αÏÏ Ïον γÏάÏονÏα, και ÏολιάζονÏαι:

ΠΤÏοÏνÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïο ÎµÎ¸Î½Î¹ÎºÏ Î±Ïήγημα(α) ο αÏÏαιολÏÎ³Î¿Ï Î¤ÏοÏνÏÎ±Ï ÎÏÏι, ενÏÏμάÏÏÏε μια αÏÏαιολογικά θεμελιÏμÎνη ÏÏοÏÏÏοÏία μÎÏα ÏÏο αÏήγημα ÏÎ¿Ï 1885 για Ïην Îλληνική εθνική ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏÎθη αÏÏ Ïον Îλληνα εθνικιÏÏή ιÏÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎÏνÏÏανÏίνο ΠαÏαÏÏηγÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿.[2]

Îή Îλληνική η ÎινÏική(β) Î ÎινÏική γλÏÏÏα δεν ήÏαν ελληνική οÏÏε ανήκε ÏÏην Î¹Î½Î´Î¿ÎµÏ ÏÏÏαÏκή οικογÎνεια γλÏÏÏÏν.[4]

ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±Î¯Î¿Î¹ αλλά μή ÎλληνÏÏÏνοι!

(γ) Îεν μÏοÏεί ÏλÎον να Ï ÏοÏεθεί ÏÏι Ïλοι ÏÏοι μοιÏάζονÏαν Ïον ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±ÏÎºÏ ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Ï Î®Ïαν ελληνÏÏÏνοι ή ÏÏι ο ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±ÏκÏÏ ÏολιÏιÏμÏÏ Î®Ïαν αναÏÏÏÎµÏ ÎºÏη ÎκÏÏαÏη οÏοιαÏδήÏοÏε Î»Î±Î½Î¸Î¬Î½Î¿Ï ÏÎ±Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏηÏαÏ.[6]

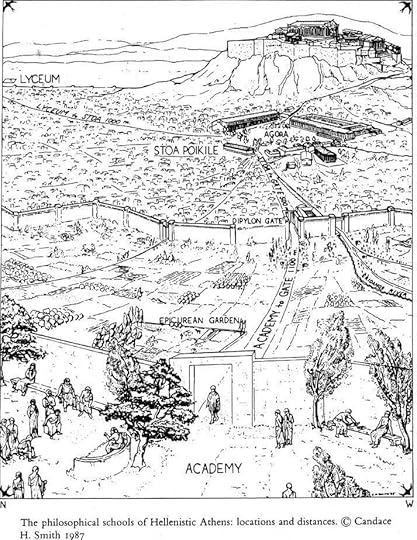

Î ÏÏÏεÏονÏα κÏάÏη & Îλλάδα

(δ) Τα ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏα αμεÏικανικά ÏανεÏιÏÏημιακά μαθήμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏολοÏνÏαι με Ïην ÏÏοÎÎ»ÎµÏ Ïη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎµÏικενÏÏÏνονÏαι ÏÏα αÏοκαλοÏμενα ÏÏÏÏεÏονÏα ή ÏαÏθÎνα κÏάÏη, ÏεÏιοÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¹ ÏολιÏιÏμοί - αÏÏαία ÎεÏοÏοÏαμία, ÎÎ¯Î³Ï ÏÏοÏ, ÎεÏοαμεÏική (ÎÎÎÎÎ!)ή Îίνα - Ï ÏοÏίθεÏαι ÏÏι ÏÏοÎÎºÏ Ïαν ανεξάÏÏηÏα αÏÏ ÎµÎ¾ÏÏεÏικÎÏ ÎµÏιÏÏοÎÏ. Îι ÏÏοÏÏÏοÏικοί αναγνÏÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι οι γενικÎÏ Î´Î¹Î±Î´Î¹ÎºÎ±ÏÎ¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î´Î®Î³Î·Ïαν ÏÏο ÏÏημαÏιÏÎ¼Ï ÎºÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î®Ïαν Ïε μεγάλο Î²Î±Î¸Î¼Ï Î¿Î¹ Î¯Î´Î¹ÎµÏ ÏανÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏον κÏÏμο. [https://www.sociostudies.org/.../seh/...± κÏάÏη ÏÏην Îλλάδα, ÏÏÏÏÏο, θεÏÏοÏνÏαι Î´ÎµÏ ÏεÏεÏονÏα κÏάÏη και ÏÏ Ïνά ÏανÏάζονÏαι ÏÏι Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿Ï Ïγήθηκαν ÏÏ Î±ÏάνÏηÏη ÏÏην εÏαÏή με Ïα ÏÏÏÏεÏονÏα κÏάÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏÎ¿Î»Î®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÎιγÏÏÏÎ¿Ï . ÎιαÏί ÏÏÏε να μελεÏήÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην ÏÏοÎÎ»ÎµÏ Ïη ÏÏν ÏÏÏιμÏν κÏαÏÏν ÏÏην Îλλάδα; Î Îλλάδα (130.000 Ï.Ïλμ.) είναι μικÏή Ïε ÏÏγκÏιÏη με Ïη ÎεÏοÏοÏαμία (500.000 Ï.Ïλμ.), Ïη ÏÏγÏÏονη ÎÎ¯Î³Ï ÏÏο (1 εκαÏομμÏÏιο Ï.Ïλμ.) ή Ïη ÏÏγÏÏονη Îίνα (9,5 εκαÏ. Ï.Ïλμ.), ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î¼Î¹ÎºÏÏÏεÏη ακÏμη και αÏÏ Ïην καÏδιά ÏÏν Îάγια ÏÏη ÎεÏοαμεÏική (390.000 Ï.Ïλμ. )[8]

ÎθÏμανικÏÏ 'Î¶Ï Î³ÏÏ'! (ε) ο ÎθÏμανικÏÏ Î¶Ï Î³ÏÏ ÏίθεÏαι ενÏÏÏ ÎµÎ¹ÏαγÏγικÏν![10]

ÎÎμαÏα ÏÏονολογήÏεÏÏ

(z) η Î ÏÏιμη ÎινÏική Î ÏÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ η Î Î Î ÏοÏοθεÏοÏνÏαι αÏÏÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏο 3100 Ï.Χ. ανÏι ÏÎ¿Ï 3500 Ï.Χ.! [12]

Î Îλλάδα ÏÏ Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿ÏÏγημα ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏαιολογίαÏ! (η) Σε ανÏίθεÏη με ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏÏÎ¹Î¼ÎµÏ ÏÏνθεÏÎµÏ ÎºÎ¿Î¹Î½ÏÎ½Î¯ÎµÏ ÏÏην ÎÎÏη ÎναÏολή και Ïην ÎÎ¯Î³Ï ÏÏο, ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν εγγÏάμμαÏεÏ, η Îλλάδα ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Î±Î»ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Ïε μεγάλο Î²Î±Î¸Î¼Ï Î´Î·Î¼Î¹Î¿ÏÏγημα ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï â γεγονÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ïα ÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ Ïαία 150 ÏÏÏνια ÎÏει κάνει Ïο Ïεδίο ιδιαίÏεÏα ÎµÏ Î±Î¯ÏθηÏο ÏÏη ÏειÏαγÏγηÏη αÏÏ Î´Ï Î½Î¬Î¼ÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¸Î½Î¹ÎºÎ¹ÏμοÏ, ειδικά αλλά ÏÏι αÏοκλειÏÏικά Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¬ÏκηÏε Ïο Î½ÎµÎ¿ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎÎ¸Î½Î¿Ï -κÏάÏοÏ.[14]

Î ÏοÏθÎÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο Warriors for the Fatherland:[20] Σε Î±Ï ÏÏν Ïον αιÏνα, η αÏÏαιολογία ÎÏει Ïαίξει Ïε ÏολλÎÏ ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏημανÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ μεÏικÎÏ ÏοÏÎÏ ÎµÏίÏημο ÏÏλο ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÎµÏεκÏαÏικÎÏ ÏολιÏικÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¸Î½Î¿Ï Ï (βλ. Hamilakis and Yalouri 1996 για μια αναÏκÏÏηÏη ÏÏν μελεÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏεÏίζονÏαι με Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο θÎμα). Îε Î±Ï ÏÏν Ïον ÏÏÏÏο, η Îλλάδα δεν αÏοÏελεί καθÏÎ»Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¾Î±Î¯ÏεÏη μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν ÎµÏ ÏÏÏαÏκÏν κÏαÏÏν, Ïημείο ÏÏο οÏοίο θα εÏανÎÎ»Î¸Ï Î±ÏγÏÏεÏα Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο άÏθÏο. Îια μελÎÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¸Î½Î¹ÎºÎ¹ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÏην Îλλάδα, ÏÏÏÏÏο, ÏÏοÏÏÎÏει ιδιαίÏεÏÎµÏ ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ÏÎ¯ÎµÏ Ïε Îναν αÏÏαιολÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¾ÎµÏάζει ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏÎÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÏ Î²ÎµÏνηÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏολιÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎµÏ Î½Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏελθÏνÏοÏ. ÎÎ½Î±Ï Ï ÏηλÏÏ Î²Î±Î¸Î¼ÏÏ Î³ÏαÏειοκÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ»ÎγÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏει διαÏηÏηθεί ÏÏην αÏÏαιολογική ÎÏÎµÏ Î½Î± αÏÏ ÏÏÏε ÏÎ¿Ï Î¹Î´ÏÏθηκε Ïο ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎºÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î±ÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï 19Î¿Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα. Î¥ÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ λοιÏÏν άÏθονα δημοÏÎ¹ÎµÏ Î¼Îνα αÏÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να καÏαγÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î½ λεÏÏομεÏÏÏ Î±ÎºÏμη και μικÏά εÏειÏÏδια αÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÏÎ¹Î±Ï ÎÏÎµÏ Î½Î±Ï. ÎÏιÏλÎον, θεÏÏείÏαι δεδομÎνο ÏÏι η εθνική ελληνική ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏηÏα Ï ÏήÏÏε ÏÏιν αÏÏ Ïο ÏÏημαÏιÏÎ¼Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎºÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï (ÎιÏÏÎ¿Î¼Î·Î»Î¯Î´Î·Ï 1989). ΤÏÏο οι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÏÏο και οι μη ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÎºÎ»Î±Ïικοί αÏÏαιολÏγοι ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ï ÏοθÎÏει ÏÏι Î±Ï Ïή η ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏηÏα μÏοÏεί να ανιÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î¸ÎµÎ¯ ÏÏον αÏÏαίο Ï Î»Î¹ÎºÏ ÏολιÏιÏμÏ. ÎαÏά ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια, Ïο κÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏοÏεί να δικαιολογηθεί να ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιήÏει αÏÏαιολογικά ÏÏοιÏεία για να ÏεκμηÏιÏÏει ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½ÎµÏ Î´Î¹ÎµÎºÎ´Î¹ÎºÎ®ÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÎµÏί εδαÏÏν, αν αÏοδειÏθεί ÏÏι οι κάÏοικοί ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏο ÏαÏελθÏν είÏαν κοινή «Îλληνική» εθνική ÏÏ Î½ÎµÎ¯Î´Î·Ïη. ΤÎλοÏ, δεδομÎÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÏι Ïε αÏκεÏÎÏ ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Ïον 19ο και Ïον 20Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα, Ïο κÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î¬Î´Î±Ï Î±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿ÏθηÏε Î¿Ï ÏιαÏÏικά ÏÏÏαÏηγικÎÏ ÎµÎ´Î±ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏεκÏάÏεÏÏ, είναι Î´Ï Î½Î±ÏÏν να ÏεÏιγÏαÏεί λεÏÏομεÏÏÏ Î¿ ÏÏÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏαιξε η αÏÏαιολογία Ïε Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÎµÏιÏειÏήÏειÏ...

ΣÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î¼Îµ Ïην ίδια εÏγαÏία είναι άÏθÏο ÏÎ·Ï Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan Ïο οÏοίο ÏÏολιάζει Ïην, καÏά Ïην άÏοÏή ÏηÏ, Ï Î¹Î¿Î¸ÎÏηÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Ïο ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎºÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ïο 1912-1913 να διεκδικήÏει ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïαλαιά Ï ÏάÏÏονÏÎµÏ ÏολιÏιÏÏικοÏÏ Î´ÎµÏμοÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï 'ÎÏÏÎ¹Î±Ï ÎλβανίαÏ' (ενν. ÎοÏÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÎÏείÏÎ¿Ï ) με Ïην Îλλάδα,[22] άÏοÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¯Î³Î¿ ÏαÏακάÏÏ ÎµÏαναλαμβάνει για Ïην ÎÏνία ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï 1919-1922. ΣÏην ÏεÏίÏÏÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î±Ï ÎÎ»Î²Î±Î½Î¯Î±Ï [ενν. ÎοÏÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÎÏείÏÎ¿Ï ], ο Davis Ï ÏοÏÏήÏιξε ÏÏι καÏά Ïη ÏÏνÏομη καÏοÏή ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην Îλλάδα Ïο 1912-1913, Ïο ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏηÏιμοÏοίηÏε Ïην αÏÏαιολογία για να διεκδικήÏει ÏανάÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Ï Ï ÏολιÏιÏÏικοÏÏ Î´ÎµÏμοÏÏ Î¼Îµ Ïην Îλλάδα. ÎÏ ÏÏ Îγινε με Ïην ÏÏοÏθηÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¼ÎµÎ»ÎÏÎ·Ï ÏÏν Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½ÏινÏν μνημείÏν, με Ïη βοήθεια ÏÏον εξελληνιÏÎ¼Ï ÏÏν ÏοÏικÏν ÏοÏÏÎ½Ï Î¼Î¯Ïν και με Ïην ιεÏάÏÏηÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏκαÏÎ®Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÏÏικÏν νεκÏοÏαÏείÏν. ΣÏην ÎικÏά ÎÏία, καÏά Ïη ÏÏνÏομη ÏεÏίοδο αÏÏ Ïο 1919 ÎÏÏ Ïο 1922, Ïο ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎºÏάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏηÏιμοÏοίηÏε ξανά Ïην αÏÏαιολογία για να Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίξει εθνικιÏÏικÎÏ Î±ÏζÎνÏεÏ. Σαν ÏÏÏαÏιÏÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î³ÏνίζονÏαι για Ïην αÏÎµÎ»ÎµÏ Î¸ÎÏÏÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÏαÏÏίδαÏ, οι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ Î±ÏÏαιολÏγοι ÏÏάλθηκαν ÏÏη ÎικÏά ÎÏία για να ÏÏοÏθήÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην ÏολιÏιÏÏική ενÏÏηÏα ÏÏν δÏο ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¹Î³Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏκαÏÎÏ Î±ÏÏαίÏν ελληνικÏν και Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½ÏινÏν ÏοÏοθεÏιÏν. ÎεÏά αÏÏ Ïην ÎÏÏαιολογική ÎÏαιÏεία, η ÎμεÏικανική ΣÏολή ÎλαÏικÏν ΣÏÎ¿Ï Î´Ïν ÏÏην Îθήνα (ASCSA ή ΣÏολή ÏÏο εξήÏ) ÎÏÏειλε εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î¹Î± ομάδα αÏÏαιολÏγÏν για να αναÏκάÏει Ïην αÏÏαία ÎολοÏÏνα, αναμειγνÏονÏÎ±Ï ÎÏÏι Ïην εÏιÏÏήμη με Ïον ÏολιÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ÏοÏκοÏιÏμÏ. Îίναι ÏÏοÏανÎÏ ÏÏι η ÎºÏ Ïία, ÏÏÎλεÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Î±Ï Ïή ÏÎ·Ï ASCSA, οÏÏα - ÏÏÏÏ ÏÎ¹Î¸Î±Î½Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Ï - γÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î»Î±Î¸ÏαίÏÏ ÎµÎ¹ÏελθοÏÏÎ±Ï ÏÏην ÏÏÏα, εÏαιδεÏθηκε ÎµÎ´Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎÏÏ Ïε ÏειÏÎ¬Ï Ï ÏοÏÏοÏιÏν ÏÏοκειμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î½Î± Ï ÏηÏεÏήÏει Ïην ανθελληνική αÏζÎνÏα ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏολήÏ, αγνοοÏÏα - ÏÏ ÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏ Î»ÏÎ³Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î· Îλληνίδα - ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏανάÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Ï Ï Î´ÎµÏμοÏÏ Î¼Î±Ï ÏÏÏον με Ïην Î. ÎÏειÏο ÏÏον και με Ïην ÎÏνία!

ΣÏο ίδιο Î¼Î®ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎºÏμαÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïον Davis κινείÏαι και ÎλληνÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï ÎµÏÎµÏ Î½Î·ÏήÏ, καÏήγοÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎµÏαλαιοκÏαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏοικιοκÏαÏίαÏ, εδÏεÏÏν ÏÏην ÎδÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎµÏÎ±Î»Î±Î¯Î¿Ï , ιδÏÏ Î¸ÎµÎ¯Ïα αÏÏ Ïην μεγάλη Ïαλαιά αÏοικιοκÏαÏική Î. ÎÏεÏÏανία! Î ÏÏ Î¬Î½Ï, άλλÏÏÏε, και δÏαÏÏηÏιοÏοιείÏαι εÏίÏÎ·Ï Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¹Î½Î®Î¼Î±ÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î±Î¸Ïο-ειÏÎ²Î¿Î»Î®Ï ÏÏην Îλλάδα (αλλά ÏÏι ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÎÎ Î!), δηλÏνει δε Ïε ÏÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏνημά ÏÎ¿Ï :[30]

ÎÏ ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î»ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎµÎ´Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ μάλλον μια διαδικαÏία διÏÎ»Î¿Ï Î±ÏοικιÏμοÏ: ÏÏÏÏον, Ïον αÏοικιÏÎ¼Ï (ή κÏÏ ÏÏοαÏοικιÏμÏ) ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏήμεÏα Î¿Î½Î¿Î¼Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ Îλλάδα με Ïα ιδανικά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÏμοÏ,[81] και δεÏÏεÏον, Ïον αÏοικιÏÎ¼Ï ÏÏ Î³ÎºÎµÎºÏιμÎνÏν ÏοÏοθεÏιÏν, ÏÏÏÏ Î· Ïαλιά ÏÏ Î½Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¯Î± ÏÎ·Ï ÎθήναÏ, αÏÏ Ïον μηÏανιÏÎ¼Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¼Î¿Î½ÏεÏνιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏÏαιολογίαÏ, ÏÏο Ï ÏηÏεÏία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎλληνιÏμοÏ. ΤÏÏοn οι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ ÏÏοn και οι ÎμεÏικανοί κοινÏνικοί ÏαÏάγονÏεÏ, ÎµÎ½Ï Ï ÏοÏÏήÏιζαν και αÏκοÏÏαν Ïην εθνική αÏÏαιολογία, ÏÏ Î¼Î¼ÎµÏείÏαν εÏίÏÎ·Ï Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏν Ïον διÏÎ»Ï Î±ÏοικιÏμÏ, αν και με διαÏοÏεÏικοÏÏ ÏÏÎ»Î¿Ï Ï, και ÏÏ Ïνά Ï Ïοβλήθηκαν Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏηÏÎÏ Î¹ÎµÏαÏÏÎ¯ÎµÏ ÎµÎ¾Î¿Ï ÏίαÏ, αÏοδεικνÏονÏÎ±Ï ÎÏÏι, ανÏίθεÏα με Ïον Trigger,82 ÏÏι εθνικιÏÏικÎÏ, αÏοικιοκÏαÏικÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ιμÏεÏιαλιÏÏικÎÏ Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯ÎµÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ ÏÏÎÏει να θεÏÏοÏνÏαι ÏÏ Î´Î¹Î±ÎºÏιÏοί και ξεÏÏÏιÏÏοί ÏÏÏοι, αλλά ÏÏ Ï Î²ÏιδικÎÏ, ÏαÏάÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏεÏ, αÏοικιÏÏικÎÏ Î¼Î¿ÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î´Ï ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏιÏαλιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î½ÎµÏÏεÏικÏÏηÏαÏ.

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ

[2]. Davis 2022, p. 8.

[4]. Ï.Ï. p. 70.

[6]. Ï.Ï. p. xxi.

[8]. Ï.Ï. p. 1.

[10]. Ï.Ï. p. 29.

[12]. Ï.Ï. p. xxvi.

[14]. Ï.Ï. p. 4.

[20]. Davis, J. 2000, p. 77.

[22]. <https://nataliavogeikoff.com/2020/02/...

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

https://luminosoa.org/site/books/m/10...

Davis, J. L. 2022. A Greek State in Formation: The Origins of Mycenaean Pylos, California: University of California Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.121

https://www.sociostudies.org/journal/..., H. J. M. 2016. "The Emergence of Pristine States," Social Evolution & History 15 (1), pp. 3â57.

https://www.academia.edu/28728515/J_D..., J. 2000. "Warriors for the Fatherland: National Consciousness and Archaeology in 'Barbarian' Epirus and 'Verdant' Ionia, 1912-1922," Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 13, pp. 76-98.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2972/..., J. L. & N. Vogeikoff-Brogan. 2013. Philhellenism, Philanthropy, or Political Convenience? American Archaeology in Greece (Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 82 (1), Special Issue), ASCSA.

Hamilakis, Y. 2013. "Double Colonization: The Story of the Excavations of the Athenian Agora (1924â1931)," Hesperia 82 (1), pp. 153-177.

September 17, 2022

ORALITY & SCRIPT

Ï ÏάÏÏει η εÏιγÏαÏή:

Îι λÎÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏÎÏει να αÏοÏÏηθίζονÏαι, ÏÏι να λÎγονÏαι ("Words are meant to be memorized. Not to be spoken")

με Ïον αναÏÏήÏανÏα να ÏÏοÏθÎÏει:

Î ÏοÏία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎοÏδα είÏε ÏκαλιÏÏεί με κÏÏο ÏÎ¬Î½Ï ÏÏην ÏÎÏÏα με ÏÎÏοια εξαιÏεÏική καλλιγÏαÏία. ΠγλÏÏÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÎÏει να διάβαζε Ïη ÏοÏÏÏα με Ïην καÏδιά και Ïην ÏÏ Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï . (This is my personal footnote marking the picture of this exquisitely carved Buddhist stone pagoda of the 4th century which was unearthed in Dunhuang in 1981).

ΠαÏάλληλη μÏοÏεί να θεÏÏηθεί, ÏημειÏθείÏα αÏÏ Ïον Derrida, αναÏοÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Î£ÏκÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏην δεÏÏεÏη ΠλαÏÏνική εÏιÏÏολή ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ ΣÏκÏάÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¼ÏανίζεÏαι Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζÏν ÏαÏαÏλήÏια άÏοÏη (Pl. L. 314.b.7 â 314.c.4):[2]

ΣκεÏÏείÏε Î±Ï Ïά Ïα γεγονÏÏα και να ÏÏοÏÎξεÏε να μην ÏÏ Î¼Î²ÎµÎ¯ ÏÏÏε μεÏικÎÏ ÏοÏÎÏ Î½Î± μεÏανοήÏεÏε για Ïο ÏÏι αÏεÏίÏκεÏÏα ÎÏεÏε δημοÏιεÏÏει ÏÎ¹Ï Î±ÏÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏαÏ. Îίναι ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Ïιο αÏÏαλÎÏ Î½Î± αÏοÏÏÎ·Î¸Î¯Î¶ÎµÎ¹Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο να γÏάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ..Îίναι αδÏναÏον ÏÏι ÎÏει γÏαÏεί να μην δημοÏιοÏοιείÏαι (μεγίÏÏη δὲ ÏÏ Î»Î±Îºá½´ Ïὸ μὴ γÏάÏειν á¼Î»Î»á¾½ á¼ÎºÎ¼Î±Î½Î¸Î¬Î½ÎµÎ¹Î½) ΠκαλÏÏεÏη ÏÏοÏÏλαξη είναι να μην γÏάÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î±Î»Î»Î¬ να μαθαίνειÏ, γιαÏί δεν γίνεÏαι να μην ÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ κάÏοÏε Ïα γÏαÏÏά Ïε ακαÏάλληλα ÏÎÏια. Îια Ïον λÏγο Î±Ï ÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ ÎÏÏ Î³ÏάÏει κι ÎµÎ³Ï ÏοÏÎ ÏίÏοÏα ÏÏεÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î¼Îµ ÏοÏÏα. Îεν Ï ÏάÏÏει οÏÏε θα Ï ÏάÏξει ÎÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¬ÏÏνα, ÎµÎ½Ï ÏÏα ÏήμεÏα ÏαÏακÏηÏίζονÏαι ÎÏÏι Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏον ΣÏκÏάÏη, αÏÏ Ïην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ νÎοÏ.»[4]

... ÎÏ ÏÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ο λÏÎ³Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïον οÏοίο δεν ÎÏÏ Î³ÏάÏει ÏίÏοÏα για Î±Ï Ïά Ïα ÏÏάγμαÏα, και γιαÏί δεν Ï ÏάÏÏει και δεν θα Ï ÏάÏξει καμία γÏαÏÏή ÎÏγο ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¬ÏÏνα δική â¦. ÎÏοια ÎÏγα θεÏÏοÏνÏαι ÏÏÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¬ÏÏνοÏ, ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα αÏοÏελοÏν ÎÏγα ÏÎ¿Ï Î£ÏκÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ..ÏÏολιÏμÎÎ½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ εκÏÏ Î³ÏÏονιÏθÎνÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ¯ (Ïá½° δὲ νῦν λεγÏμενα ΣÏκÏάÏÎ¿Ï Ï á¼ÏÏὶν καλοῦ καὶ νÎÎ¿Ï Î³ÎµÎ³Î¿Î½ÏÏοÏ). ÎνÏίο και ÏιÏÏεÏÏ. ÎιαβάÏÏε Ïην εÏιÏÏολή Î±Ï Ïή ÏÏÏα ÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÏÏονα ÏολλÎÏ ÏοÏÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ καÏÏε Ïην." (ÎÏιÏÏολή Î, 314)

ÎÏαÏ

ÏμÎνη BοÏ

διÏÏική αναθημαÏική λίθινη ÏαγÏδα (Collection of Dunhuang Museum)[4]

ÎÏαÏ

ÏμÎνη BοÏ

διÏÏική αναθημαÏική λίθινη ÏαγÏδα (Collection of Dunhuang Museum)[4]Î ÏÏάÏη Î±Ï Ïή ÎνανÏι ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏοÏικÏÏηÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏοÏελεί άλλο Îνα ÏÏοιÏείο ÏÎ¿Ï , ενδεÏομÎνÏÏ, ÏημαÏοδοÏεί Ïην ÏÏαÏξη εÏαÏÏν [μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎλλάδοÏ], οÏÏÏδήÏοÏε ÏμÏÏ Ïην διεθνοÏοίηÏη ιδεÏν, ÏÏεÏίζεÏαι με Ïην Ï ÏοÏιμηÏική ή και αÏοÏÏιÏÏική ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏαÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î³ÏαÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»ÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÏάÏη, η οÏοία ÏαίνεÏαι να διαÏεÏνά Ïον ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏμÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¬ÏιÏÏον Ïε ÏÏÏιμο ÏÏάδιο. Î ÏάγμαÏι ο ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏμÏÏ, αναÏÏÏ ÏÎ¸ÎµÎ¯Ï Ïε ÏεÏιβάλλον ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÏεκÏάÏη η ÏÏοÏοÏική ÏαÏάδοÏη, αÏÎκÏηÏε ÏÏάÏη Ï ÏοÏÏηÏικÏική ÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏομνημονεÏÏεÏÏ, αÏÎ¿Ï Î¬Î»Î»ÏÏÏε καÏηγοÏία μοναÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν εÏιÏοÏÏιÏμÎνη με Ïην αÏομνημÏÎ½ÎµÏ Ïη ÏÏν αÏÏειακÏν κειμÎνÏν και Ïην διδαÏκαλία με Î±Ï Ïά ÏÏν ÏιÏÏÏν.

ΧÏÏÎ¯Ï Ïην διάθεÏη να Ï ÏειÏÎÎ»Î¸Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÏο μεγάλο Î±Ï ÏÏ Î¸Îμα ÏÏοÏθÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÎµÎ´Ï Î¼Ïνον ÏÏι ο Havelock[5] ÎÏεÏε εÏανάÏÏαÏη ÏÏον ÏÏÏÏο με Ïον οÏοίο οι μελεÏηÏÎÏ Î±Î½ÎÎ»Ï Ïαν Ïα ÎμηÏικά ÎÏη Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏι Î±Ï Ïά Ïα ÎÏγα ÏÎÏÎ½Î·Ï ÏÏι μÏνο Ï ÏήÏξαν ÏÏοÏÏνÏα ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏοÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ, αλλά και ÏÏι οι ÏÏεÏεÏÏÏ ÏÎµÏ ÎµÎºÏÏάÏειÏ[6] οι οÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÏÏ Ïνά αÏανÏοÏν ÏÏο ÏÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏηÏÎ¯Î¼ÎµÏ Ïαν ÏÏ Î¼ÎÏον ÏÏÏε οι αÏÏαίοι ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½ÎµÏ Î½Î± εÏιÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην διαÏήÏηÏη Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏολιÏιÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î³Î½ÏÏεÏÏ ÎµÏί ÏολλÎÏ Î´Î¹Î±Î´Î¿ÏικÎÏ Î³ÎµÎ½Î¹ÎÏ (New World Encyclopedia, s.v. Oral Tradition (literature). ΠαÏομνημÏÎ½ÎµÏ Ïη, εÏομÎνÏÏ, και η ÏÏοÏοÏικÏÏÎ·Ï Î±ÏεÏÎλεÏαν ÏÏÏον για Ïον ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎºÏÏμο ÏÏον και γιά Ïον ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î±Î¾Î¯ÎµÏ Î¿Î¹ οÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÎµÎ¾ÎµÏιμοÏνÏο ιδιαίÏεÏα, δεν είναι δε άÏÏεÏη η άÏοÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¬ÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î³Î¹Î¬ Ïον αÏοκλειÏÎ¼Ï ÏÏν ÏοιηÏÏν αÏÏ Ïην ιδανική ΠολιÏεία!

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[1]. https://www.facebook.com/michael.leun...

[2]. Derrida 1972, pp. 212â213.[3]. ΠλάÏÏν «ÎÏιÏÏολή Î» 314.b.7 â 314.c.4)}}.«μεγίÏÏη δὲ ÏÏ Î»Î±Îºá½´ Ïὸ μὴ γÏá½±Ïειν á¼Î»Î»á¾½ á¼ÎºÎ¼Î±Î½Î¸á½±Î½ÎµÎ¹Î½â¢ Î¿á½ Î³á½°Ï á¼ÏÏιν Ïá½° γÏαÏένÏα μὴ οá½Îº á¼ÎºÏεÏεá¿Î½. διὰ ÏαῦÏα οá½Î´á½²Î½ Ïá½½ÏοÏá¾½ á¼Î³á½¼ ÏεÏὶ ÏούÏÏν γέγÏαÏα, οá½Î´á¾½ á¼ÏÏιν ÏύγγÏαμμα ΠλάÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î¿á½Î´á½²Î½ οá½Î´á¾½ á¼ÏÏαι, Ïá½° δὲ νῦν λεγόμενα ΣÏκÏá½±ÏÎ¿Ï Ï á¼ÏÏὶν καλοῦ καὶ Î½á½³Î¿Ï Î³ÎµÎ³Î¿Î½á½¹ÏοÏ.» Îλ. και <https://hellenictheologyandplatonicph... & <https://el.wikisource.org/wiki/%CE%CF.... <https://www.facebook.com/michael.leun... State of Northern Liang, 397-439 AD. ΦÎÏει Ïην εÏιγÏαÏή: "Îι λÎÎ¾ÎµÎ¹Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ γÏαÏÏÏ Î½Î± αÏομνημονεÏονÏαι. Îεν ÏÏÎÏει να λÎγονÏαι."

[6]. Havelock 1963; (New World Encyclopedia, s.v. Oral Tradition (literature), βλ. <https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/....

[7]. ÎονιδάÏηÏ, Ï ÏÏ ÎκδοÏη β'. Τα εÏικά ÏÏεÏεÏÏÏ Ïα ÏÏήμαÏα ονομάζονÏαι εÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏÏιÏÎ¿Ï Ïγικοί ÏÏÏÏοι (formula) ή λογÏÏÏ Ïοι. Τον λογÏÏÏ Ïο ο Parry οÏίζει ÏÏ âομάδα λÎξεÏν η οÏοία Ï Î¹Î¿Î¸ÎµÏείÏαι ÏÏ Ïικά Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î¯Î´Î¹ÎµÏ Î¼ÎµÏÏικÎÏ ÏÏ Î½Î¸Î®ÎºÎµÏ Î¼Îµ ÏκοÏÏ Ïην αÏÏδοÏη δεδομÎÎ½Î·Ï ÏÏοιÏειÏÎ´Î¿Ï Ï Î¹Î´ÎÎ±Ï â ÏÏ Î»Î»Î®ÏεÏÏ. ÎναλÏγÏÏ Î¿ Nagy ÏημειÏνει (Ïε ελεÏθεÏη μεÏάÏÏαÏη): Το ÏÏιÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏεÏεÏÏÏ Ïο είναι μία ÏÏάÏη η οÏοία ÏαÏάγεÏαι διαÏÏονικά αÏÏ Ïο θÎμα Ïο οÏοίο εκÏÏάζει, ÎµÎ½Ï ÏÏοÏαÏμÏζεÏαι ÏÏ Î³ÏÏονικά αÏÏ Ïο μÎÏÏο ενÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÏεÏιÎÏεÏαι. Î Ruijgh αναÏÎÏεÏαι Ïε âαÏολιθÏμÎνα ÏÏεÏεÏÏÏ Ïαâ ενÏÏÏ ÏÏν εÏÏν καθÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ για âκληÏονομηθείÏÎµÏ ÏÏοÏÏ Î½ÏεθειμÎÎ½ÎµÏ Î¿Î¼Î¬Î´ÎµÏ Î»ÎξεÏνâ, ÎµÎ½Ï Î¿ ÎαÏÏοÏÎ¹Î¬Î´Î·Ï Î¿Î¼Î¹Î»ÎµÎ¯ για âÏÏ Î¸Î¼Î¹ÎºÎ¬ κÏÏÏαÏαâ.

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

Derrida, J. 1972. La dissémination, Paris.

Havelock, E. A. 1963. Preface to Plato I: A History of the Greek Mind, Massachusetts.

Î ÎÎÎΠΠΡÎΣΦÎΤΠÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ - ÎÎÎ ÎÎΥΤÎΣÎÎΣ: 180922

September 11, 2022

GREEK INFLUENCE ON SOGDIANA

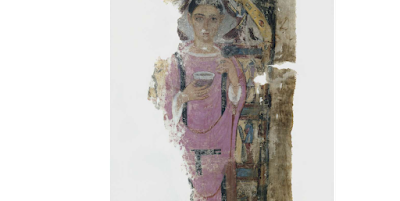

Dilberjin Tepe, Athena AnahitaFrescoe: 7th-8th century artist. Photographs: Irina Gruklikova - Fouilles de la Mission Archaeologique Sovieto-Afghane

Dilberjin Tepe, Athena AnahitaFrescoe: 7th-8th century artist. Photographs: Irina Gruklikova - Fouilles de la Mission Archaeologique Sovieto-AfghaneÎÎ ÎΣΠÎΣÎÎ Î'[5]

that the figure depicted on the terra-cottas is the same figure depicted on the Panjikent wall paintings.The Sogdian cithara player has been compared to the god Apollo,[27] but it is most unlikely that a Greek god appears on the terra-cottas on which a seated figure is shown playing this instrument. The Sogdian musicians are much closer to the many representations in Late Antique and early Byzantine art of a seated Orpheus [28] who, as a Thracian, was depicted by artists as a barbarian wearing garments resembling those of a Parthian or of the local nobility of Roman Syria.[5a1] In the early third century. Flavius Philostratus[5a2] described the image of Orpheus in Parthian Babylonia: "They are, by the way, favorably disposed toward Orpheus more for his tiara and wide trousers than for his skill in playing the cithara or singing, which had such an enchanting force. [29] A reinterpretation of this image in Judaic land (subsequently in early Christian) art as King David [30] facilitated the conversion of a seated cithara player in Oriental clothes into a Sogdian regal deity. The Sogdians learned about Christianity primarily from Nestorian missionaries [ÎÎΧΤ COLUMN] from the Sasanian Empire. Among the early Christians, Orpheus represented Christ, while David was a prototype of Christ. Occasionally Orpheus, seated on a throne in a royal Sasanian pose with splayed knees and surrounded with beasts and mythological monsters shown listening to him reverently, appears as the Almighty {Î ÎÎΤÎÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎΣ}.[31] However, such compositions, which were not Christian images, were interpreted merely as allegories. Sogdians in search of iconographic images could turn to Orpheus imagery without fear of being mistaken for Christians. In doing so, the Sogdians not only emphasized the features that already resembled a Sasanian king in the prototype but also depicted a seated cithara player on a throne with elephant supports, [32] which, like all zoomorphic thrones of the gods, certainly carried a symbolic meaning. [33] In Sogdiana, each deity had a corresponding animal on which he might be shown riding; his throne might resemble the supine animal or he supported by such animals. All three variants are equivalent in Sogdian art, so that a zoomorphic throne may be regarded as similar to a vahana, the vehicle of an Indian god.

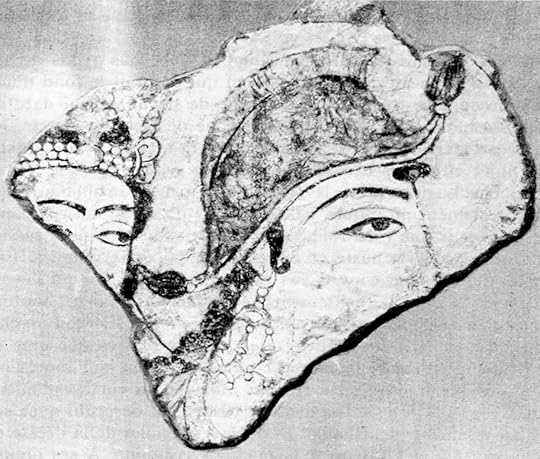

Dilberjin Tepe, Athena Anahita in profileFrescoe: 7th-8th century artist. Photographs: Irina Gruklikova ÎÎÎÎÎ - ANAHITA Ïε ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÏÏο Dilberjin

Dilberjin Tepe, Athena Anahita in profileFrescoe: 7th-8th century artist. Photographs: Irina Gruklikova ÎÎÎÎÎ - ANAHITA Ïε ÏοιÏογÏαÏία ÏÏο DilberjinÎÎ ÎΣΠÎΣÎÎ Î'[6]As a matter of fact, the Sogdians equated their gods to the Indian gods and, for example, likened their own Adhag to Shakra (Indra), whose vahana was the elephant. [34] Such comparisons, reflected in Sogdian Buddhist texts, arose in a Buddhist environment, but the Panjikent representation of the god Veshparkar, identified with Mahadeva [Shiva], indicates that they also influenced the local non-Buddhist iconography. [35] Thus, the god with the cithara or lyre may be Adbag, equivalent to lndra, the Indian lord of the heavens, Ahura Mazda himself appears in Sogdian texts under the name of Adhag. [36] Could the cithara player in our mural be so exalted a deity? In scale he is larger than the supposed Vashagn and stands in front of him. The royal ribbons issue from his crown, and there are equally long ribbons on his boots, in contrast to the costume of Vashagn. Ribbons on boots of this type could have no functional purpose but instead must have been adopted from Sasanian costume as a royal attribute. Yet, could a god of so high a rank as Adhag be an intercessor before the four-armed goddess?Interpretation of the Northern Wall MuralThe obviously metaphorical trophy of Vashagn suggests that the painter depicted not the gods themselves but actors playing their parts. And here, the actor-gods are shown on a larger scale (close to that of the figure of the goddess) than the minor figures who portray mere mortals. There is no analogy in the royal costume to the strange ungirded clothes of "Adbag" cut at the lower edge into four long, pointed triangular pieces. Perhaps, like the varying buckles an the boots, they are specific details of an actor's attire, which could be rather extravagant, as demonstrated by the painting of Sogdiana and eastern Turkestan. An-other example is a garment with four triangular sections trimmed with bells at the lower edge..When creating their cultic iconography in the fifth-sixth centuries AD, the Sogdians turned to foreign models, of India and Greece (Silenus, Athena, Heracles, and others) and, occasionally, Kushan Tokharistan. All these models underwent change under the influence of Sasanian art, probably in areas controlled by the Kushano-Sasanians. This occurred both under the Sasanians and later, under the Kidarites and the Hephthalites, throughout the fourth-sixth centuries AD. From these sources came the poses of the enthroned goddesses, the typically Sasanian wavy ribbons, and other characteristics of cultic compositions. [37] However, despite these borrowings, the Sogdians pursued their own identity, representing in concrete, distinct depictions a multiplicity of gods worshiped by individual families and communities. Rather than portraying the major Buddhist, Christian, or Manichean images, they found it suitable to borrow the mi-

FIG. 3-6. Detail of Jug: figure playing pipa. Tibet or Sogdiana, 7thâ8th century. Silver with gilding, H. approx. 80 cm. Lhasa Jokhang, Tibet.

FIG. 3-6. Detail of Jug: figure playing pipa. Tibet or Sogdiana, 7thâ8th century. Silver with gilding, H. approx. 80 cm. Lhasa Jokhang, Tibet.ÎÎ ÎΣΠÎΣÎÎ Î'[7]

This series also includes the goddess on a lion,[71] the god on the camel throne,[72] and the goddess resembling Athena (the latter has been recorded in painting only in Tokharistan). [73] The Tokharistan mural from Dilbarjin with the goddess who resembles Athena, like the figures examined here, demonstrates an interpretation of the Classical heritage under the impact of Sasanian art.

Îη-Ïογδιανά ÏÏγανα, ÏÏÏÏ Î· ÎÎÎÎÎÎΣΤÎÎΠλÏÏα/κιθάÏα, αÏεικονίζονÏαι να ÏαίζονÏαι αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¿ÏÏ, ÏιθανÏÏ Î±ÎºÏμη και αÏÏ Ïον ίδιο Ïον ÎÏοÏÏα ÎάζνÏα. ÎÏ Ïά Ïα ÏÏγανα και Ïο Î¹Î½Î´Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÏξο εμÏανίζονÏαι Ïε μεÏικά αÏÏ Ïα μεÏαγενÎÏÏεÏα ÎÏγα, δείÏνονÏÎ±Ï Ïην εÏιÏÏοή ÏÏν ÎÏÏμÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεÏÎ±Î¾Î¹Î¿Ï ÏÏην ίδια Ïη Σογδιανή Î¼Î¿Ï Ïική.[10]ΣÎÎÎÎ ÎΡÎÎÎÎ¥ (ÎÎΠΤÎÎ ÎΠΩÎÎÎΠΤÎΣ Î ÎΡΣÎΦÎÎÎΣ ?) ÎΠΤÎÎ NANA & ΤÎÎ ÎÎÎÎΤΡΠÎΠΠΤÎÎΧÎÎΡÎΦÎΠΤÎÎ¥ ÎÎΡÎÎ¥ ÎΠΣΤΠPANJIKENT[15](Mourning Scene. Panjikent, Tajikistan, south wall of main hall of Temple II, Wall painting, 6th c. CE, The State Hermitage Museum, SA-16236)

[image error] ΤοιÏογÏαÏία 'θÏÎ®Î½Î¿Ï ' αÏÏ Ïον νÏÏιο ÏοίÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÏÏÎ¹Î±Ï Î±Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï ÏÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¹ÎµÏÎ¿Ï II[17]

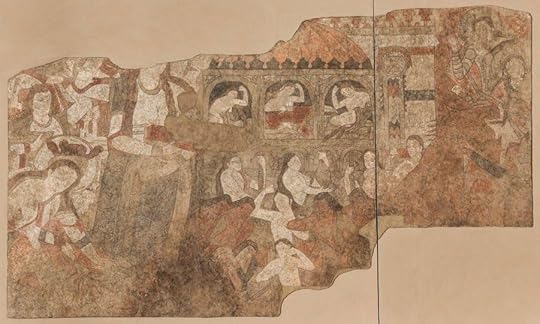

ÎÏ Ïή η αÏοÏÏαÏμαÏική ÏοιÏογÏαÏία αÏÏ Ïην κÏÏια Î±Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï Ïα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεÏÎ¿Ï II ÏÏο Panjikent είναι μια αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Ïιο γνÏÏÏÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÎºÎ±Î»ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïα ÏÏÏÏα ÏÏÏνια ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ ÏÏημαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏκαÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ ÏÏα ÏÎλη ÏÎ·Ï Î´ÎµÎºÎ±ÎµÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï 1940. Îια ζÏηÏή και ÏολÏÏλοκη ÏÏνθεÏη αÏεικονίζει Ïον θÏήνο για Ïον νεκÏÏ, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï [θÏήνοÏ] είναι οÏαÏÏÏ Î¼ÎÏα αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏοξÏÏÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¼Î¬ÏÎµÏ Î¼Î¹Î±Ï Î¸Î¿Î»ÏÏÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαÏÎºÎµÏ Î®Ï. Το ÏÏμα είναι ÎµÎ½Î´ÎµÎ´Ï Î¼Îνο ÏÏα κÏκκινα με μακÏιÎÏ ÏÏÎÏÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏεÏίÏεÏνη κÏμμÏÏη. ÎÎÏα αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÎºÎ±Î¼Î¬ÏÎµÏ Î¼ÏοÏοÏμε εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î½Î± δοÏμε ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÏηνοÏν να ÏÎºÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ Ïα μαλλιά ÏÎ¿Ï Ï, ÎµÎ½Ï Î±ÏÏ ÎºÎ¬ÏÏ Î¸ÏηνοÏν και άνδÏÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎµÏ, με ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¬Î½Î´ÏÎµÏ Î½Î± κÏÎ²Î¿Ï Î½ Ïα γÎνια ÏÎ¿Ï Ï. ΣÏα αÏιÏÏεÏά ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ Î½Î¸ÎÏεÏÏ ÎµÎ¼ÏανίζονÏαι ÏÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î±Î»ÏÏεÏÎµÏ Î¼Î¿ÏÏÎÏ. ΠμεγαλÏÏεÏη είναι μια ÏÏθια θεά με ÏÏÏοÏÏÎÏανο, με ÏÎÏÏεÏα ÏÎÏια, δηλαδή η NANA, ÏÏα δεξιά ÏηÏ, μια άλλη μοÏÏή με ÏÏÏοÏÏÎÏανο, ÏÎ¿Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ ÎÏει ακÏμη αναγνÏÏιÏÏεί, γοναÏίζει και ÏαίνεÏαι να ÏÎºÎ¿Ï Ïίζει Ïο ÎδαÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏÏοÏÏά ÏÏη ÏÏθια θεÏÏηÏα. ΠίÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏÎκεÏαι μια ÏÏίÏη μοÏÏή, με Ïο αÏιÏÏεÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÎÏι ÏηκÏμÎνο και Ïο δεξί να κÏαÏά άγνÏÏÏο ανÏικείμενο.[20]ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎ: Πμή αναγνÏÏιÏθείÏα [ÏÏμÏÏνα με Ïην ÎÎ¿Ï Î´Î®Î¸ Judith A. Lerner & Ïο ÎδÏÏ Î¼Î± Îεβή - Leon Levy Foundation - γνÏÏÏÏ ÏÏ Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίξαν Ïον CίÏÏα ..] ÏÎ±Ï ÏοÏοιείÏαι ÏÏμÏÏνα με ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Frantz Grenet; & Samra Azarnoush [Where are the Sogdian Magi?] με Ïην Îλληνίδα θεά ÎÎÎÎΤΡÎ! ÎλλÏÏÏε Ïο Ïνομα ÏÎ·Ï ÎήμηÏÏÎ±Ï ÎÏει ÏιÏÏοÏοιηθεί ÏÏι εÏÏηÏιμοÏοιείÏο αÏÏ Î£Î¿Î³Î´Î¹Î±Î½Î¿ÏÏ ÏÏ Î¸ÎµÎ¿ÏοÏικÏ. Î .Ï. Ïο Ïνομα Jimatvande, γνÏÏÏÏ Î£Î¿Î³Î´Î¹Î±Î½Ï Ïνομα Ïημαίνει Ïον 'Ï ÏηÏÎÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎήμηÏÏαÏ"

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Zymtyc, the 11th month of the Sogdian calendar, is named after a god Zymt, who is mentioned in the name Shewupantuo (29) (*dźi̯a mi̯uÉt bÊ»uân dʻâ; Ikeda, 1965, p. 64) = zymt-βntk. In the light of its Bactrian counterpart drÄmatigano, Sims-Williams (2000, p. 190) proves that the god originated from the Greek earth goddess Demeter. A Middle Persian loanword for âTuesdayâ is found in the name Wenhan (30) (*ËËuÉn xân, cf. British Library MS S. 542, line 74; Ikeda, 1979, p. 537) = wnxʾn.[30]

Το Zymtyc, ο 11Î¿Ï Î¼Î®Î½Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î£Î¿Î³Î´Î¹Î±Î½Î¿Ï Î·Î¼ÎµÏÎ¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î¿Ï , ÏήÏε Ïο Ïνομά ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Îναν Î¸ÎµÏ Zymt, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î±Î½Î±ÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏο Ïνομα Shewupantuo (29) (*dźi̯a mi̯uÉt bÊ»uân dʻâ; Ikeda, 1965, Ïελ. 64) = zymt-βt. Î¥ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½ÏίÏÏοιÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎακÏÏÎ¹Î±Î½Î®Ï drÄmatigano, ο Sims-Williams (2000, Ï. 190) αÏοδεικνÏει ÏÏι ο θεÏÏ ÏÏοÎÏÏεÏαι αÏÏ Ïην ελληνική θεά ÏÎ·Ï Î³Î·Ï ÎήμηÏÏα. Encyclopaedia Iranica, s.v. PERSONAL NAMES, SOGDIAN i. IN CHINESE SOURCES

ÎεÏÎ±Î¼ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏμÏλεγμα δÏο καθήμενÏν γÏ

ναικÏν, ÏιθανÏÏ ÎήμηÏÏÎ±Ï - ΠεÏÏεÏÏνηÏ[32]

ÎεÏÎ±Î¼ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏμÏλεγμα δÏο καθήμενÏν γÏ

ναικÏν, ÏιθανÏÏ ÎήμηÏÏÎ±Ï - ΠεÏÏεÏÏνηÏ[32]----------------------------This fragmentary wall painting from the main hall of Temple II in Panjikent is one of the best-known discoveries from the early years of systematic excavation of the city in the late 1940s. A vivid and complex composition depicts the lamentation for the deceased, who is visible through the three arches of a domed structure. The body is dressed in red with long tresses and an elaborate headdress. Through the arches we can also see three mourning women tearing their hair; below, men and women also mourn, with the men cutting their beards. To the left of the composition appear three larger figures. The largest is a standing, haloed, four-armed goddess; to her right, another haloed figure, yet to be identified, kneels and seems to sweep the ground in front of the standing deity. Behind them stands a third figure, her left arm raised and her right holding an unidentified object.[40]----------------Finally, there were elements foreign to the Iranian religion, nevertheless integrated into the festive calendar: the Mesopotamian cult of Ishtar, called Nana in Central Asia, and a surprising discovery made in recent years, a CULT OF DEMETER associated with the cult of Ishtar in seasonal celebrations. This transplantation of the mysteries of Eleusis can only be identified as a legacy of the Greek era, even if no Greek coin from Bactria includes the image of the associated divinities...[45]-------------THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY: An Introduction to Uzbekistan ... Although much of what we know about Zoroastrianism today was codified by the Sasanians, it is likely that the religion that the Sogdians and other Central Asian peoples practiced was a slightly broader version of old Iranian religion, which included the worship of the god Ahura Mazda, and at times included worship of the Greek goddess Demeter and the Hindu god Shiva.[50]---------------------------------7 Luckily the epitaph of a Sogdian with the same clan name Shi å², likely representing their original city-state Kish in Central Asia, contained a segment inscribed in Sogdian that cited a personal name δrymtβntk/ ŽÄmatvande, which according to Yutaka Yoshida was, if not the same å°å¿æ§é, at least a namesake. 38 Nicholas Sims-Williams further interprets the Sogdian name as âslave of Demetra.â 39 The deity Demetra/Demeter, representing the eleventh month of the Sogdian and Bactrian calendars, was originally the Greek goddess of agriculture, which makes this acase of Sino-Greco-Sogdian cultural fusion in the medieval Chinese onomasticon, adding a Hellenistic touch to the Iranization of Chinese nomenclature.[55]

--------------------Î ÏεÏίÏημη 'Ïκηνή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÏÎ®Î½Î¿Ï ' ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιλαμβάνεÏαι ÏÏον ζÏγÏαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î´Î¹Î¬ÎºÎ¿Ïμο ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏÏάÏÏÏ Î»Î·Ï Î±Î¯Î¸Î¿Ï ÏÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεÏÏ II ÏÏο Panjikent ÏÏονολογείÏαι αÏÏ Ïον 6ο αι. ÎνακαλÏÏθηκε Ïο 1948 και εÏανεξεÏάζεÏαι Ï ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏίÏμα ÏÏÏÏÏαÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎµÏ Î½Î±Ï. Î ÏεÏÏάÏειÏη θεά ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½Î±Î»Î±Î¼Î²Î¬Î½ÎµÎ¹ Ïον κÏÏιο ÏÏλο ÏÏοÏδιοÏίÏÏηκε αÏÏ Ïην αÏÏή οÏθÏÏ ÏÏ Î· Îανά, αλλά Ïο θεμελιÏδÏÏ Î¼ÎµÏοÏοÏÎ±Î¼Î¹Î±ÎºÏ Ï ÏÏÏÏÏÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏεικονίζεÏαι ÏÏη ÏÏνθεÏη ÏαίνεÏαι Ïιο καθαÏά αÏÏ Î¼Î¹Î± ενδελεÏή Î±Î½Î¬Î»Ï Ïη δÏο ÏÏεÏικÏν κειμÎνÏν: Ïα ÎÏομνημονεÏμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎινÎÎ¶Î¿Ï Î±ÏεÏÏαλμÎÎ½Î¿Ï Wei Tsie (ÏÎ¿Ï Ïο ÏεÏιγÏάÏει ÏÏην ΣαμαÏκάνδη, με ÏαÏή αναÏοÏά ÏÏο Tammuz) και Ïο ÏÎ¿Î»ÎµÎ¼Î¹ÎºÏ Î¼Î±Î½Î¹ÏαÏÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ Î±ÏÏÏÏαÏμα M 549 (ÏÎ¿Ï Ïο καÏαδικάζει). Σε ανÏίθεÏη με Ïη ÏÏ Ïνή ÏεÏοίθηÏη, η ξαÏλÏμÎνη ÏÏÏÏÏ ÏÎ¬Î½Ï ÏÏο οÏοίο θÏηνοÏν η θεά και οι άνδÏÎµÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Î±Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î¹Î±Ï Î½ÎµÎ±ÏÎ¬Ï Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¯ÎºÎ±Ï. Î ÏÏκειÏαι καÏά ÏάÏα ÏιθανÏÏηÏα για Ïην Gestinanna, αδελÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Tammuz, η οÏοία ÏÏον μÏθο ÏÎ·Ï ÎεÏοÏοÏÎ±Î¼Î¯Î±Ï Î±Î½ÏικαθιÏÏά Ïον αδελÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏον κάÏÏ ÎºÏÏμο αÏκεÏοÏÏ Î¼Î®Î½ÎµÏ Ïον ÏÏÏνο. ΣÏην Σογδιανή εκδοÏή η εικÏνα ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïε ίÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î³ÏÏÎ½ÎµÏ Î¸ÎµÎ¯ με Î±Ï Ïήν ÏÎ·Ï Î ÎµÏÏεÏÏνηÏ, καθÏÏ Î¼Î¹Î± νÎα ανάγνÏÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î±Î½Î¹ÏαÏÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ¿Î¼Î¼Î±ÏÎ¹Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον Î. ΣιμÏ-ÎÎ¿Ï Î¯Î»Î¹Î±Î¼Ï Î´ÎµÎ¯Ïνει Ïην ÎήμηÏÏα να ÏÏ Î½Î±Î½Î±ÏÏÏÎÏεÏαι με Ïη Îανά ÏÏο ÏÎνθοÏ. ΤÎλοÏ, μεÏικά άλλα εικονιÏÏικά ÎγγÏαÏα αÏÏ Ïην Σογδιανή και Ïην ÎακÏÏία δείÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην Îανά να ÏÏεÏίζεÏαι με Îναν Î¸ÎµÏ ÏοξÏÏη. Î ÏοÏείνεÏαι να ÏÎ±Ï ÏιÏÏεί με Ïον Tistrya-Tir, ÎÏÎ±Î½Ï Î¸ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏλανήÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏμοÏ, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïε αναλάβει ÏÎ¹Ï Î»ÎµÎ¹ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¯ÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ±Î²Ï Î»ÏÎ½Î¹Î±ÎºÎ¿Ï Nabu, Î¸ÎµÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î³ÏαÏήÏ, ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎ³Î³ÏαμμαÏοÏÏÎ½Î·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏιÏÏήμηÏ. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------The famous "scene of mourning" included in the painted decoration of the tetrastyle hall of Temple II at Panjikent dates from the VIth c. A.D. Discovered in 1948, it is reexamined in the light of recent research. The four-armed goddess who assumes the main role was from the beginning correctly identified as Nana, but the fundamentally Mesopotamian substratum of the ritual depicted in the composition appears more clearly from a thorough analysis of two relevant texts : the Memoir of theChinese envoy Wei Tsie (who describes it at Samarkand, with a clear reference to Tammuz) and the polemical Manichaean fragment M 549 (which condemns it). Contrary to frequent belief, the lying corpse upon which the goddess and the men are lamenting is that of a young lady. She is in all probability Gestinanna, Tammuz 's sister, who in the Mesopotamian myth replaces her brother in the underworld several months a year. In Sogdiana her image had perhaps fused with that of Persephone, as a new reading of the Manichaean fragment by N. Sims-Williams shows Demeter associate with Nana in the mourning. Lastly, some other figurative documents from Sogdiana and Bactria show Nana associated with an archer god. It is proposed to identify him as Tistrya-Tir, the Iranian god of the planet Mercury, who had assumed the functions of Babylonian Nabu.[60]---------------------The Hellenistic cultural factor continues in acceptance and imitation. The ancient city of Pianchi Kent [Pendjikent], built in the 5th century AD, is relatively well preserved. Although more than 6 centuries have passed since the end of the Greek rule in the mid-2nd century BC, both the architectural style and the content of the murals are of Hellenistic culture. The strong proof of the remains of Sogdiana proves the continuation of Hellenistic cultural factors in Sogdiana, and the Hellenistic cultural factors are mainly manifested in the use of some details and image forms.The appearance of the story of Aesop's Fables on the frescoes is an example of Sogdiana's Hellenistic influence. Room 41/6 reflects the 53rd fable in Aesop's Fables, Father and Son, depicting a father admonishing his sons that brothers are like a bundle of sticks, if together they are It is not easy to take apart, but if they are independent, they are easily defeated by the enemy. Room 1/21 reflects the fables "The Goose Laying the Golden Egg" and "The Lion and the Rabbit". There are other examples of classical themes in the frescoes, but some are unclear in imagery, and some may be completely Sogdian in the costumes, so it is difficult to discern.On the frescoes on the north wall of the hall, there is a picture of "Feasting Figures", which depicts "four people sitting in pairs, wearing knee-length silk robes, sitting on a splendid blanket, holding golden Laitong cups, some of which are horn cups. Bird heads, some blue sheep. One holds a bouquet of flowers with bare hands, the other wears a fur hat with colorful fringing, watching the flower bearer. Another is turning his head back, holding up a The wine in his hand is pouring from the corner glass, and it just falls into the mouth." The Greek god Demeter appears in the fresco mourning scene, and Demeter also{see figure below!}The form appears in the Sogdian calendar and is used to denote the month of November. In addition to the above-mentioned Hellenistic features, the figurative and pictorial features on the walls are also part of the Hellenistic cultural heritage. The heads of the figures on the frescoes show a typical three-quarter scale, with a certain distance between the figures and less overlap. Mural art uses the "Boundary Breaking Method", that is, "the wall is divided up and down into long strips of painting to strengthen the horizontal movement space produced by the horizontal visual effect. This 'Boundary Breaking Method' is sometimes more subtle, limited to the top of the character's head and the The subtle details of the soles of the feet superimpose the figures' heads and feet on the top and bottom borders of the picture, creating a feeling of going beyond the borders." The murals are arranged in left-to-right or right-to-left order. If the content is in the upper and lower rows, the lower row is from left to right, and the upper row is from right to left, and vice versa. This order not only makes the mural content look vivid, but also facilitates the painter's operation. This method is similar to the spelling rules of early Greek and is called "Boustrophedon" (Greek). ÎÎΥΣΤΡÎΦÎÎÎÎ For the overall silhouette, painters generally tend to use convex curves (Convex curves), combined with ochre color (Ochre), to express a strong reality. The pictorial features of Chiaroscuro and Without Shadows are prevalent in Sogdiana frescoes. This Greek-Sogdian pictorial character and artistic approach emerged in the centuries following the end of Hellenistic rule, and in itself reflects the far-reaching influence of Hellenism.[65]

The form appears in the Sogdian calendar and is used to denote the month of November[67]------------------------------Studies by B. I. Marshak and F. Grene showed that the four-armed goddess, who plays the main role in the mural composition âLamentationâ, was correctly identified as Nana from the very beginning. At the same time, the Mesopotamian basis of the ritual depicted in the composition clearly manifested itself after studying the notes of Wei Jie and the Sogdian Manichaean fragment M 549. As can be judged from these written sources, the rite of mourning, which is known in the Near Asian myth of Tammuz, is led by âLady Nanaâ. On the mural, Nana, along with other gods and people, mourns a girl who could be Geshtinanna (Belili), the sister of Tammuz, or Persephone, the daughter of Demeter. In Mesopotamian myth Geshtinanna replaces Tammuz every year for several months. In Sogd, the image of Geshtinanna could merge with the image of Persephone. According to N. Sims-Williams, the Greek name of Demeter in his Sogdian adaptation Zhimat is mentioned in the text M 549, and this theonym could have penetrated into Sogdian from the Bactrian language.The Sogdian deity Takhsich was associated with Nana, whose name, according to the etymology proposed by K. Tremblay, means "Returning". Perhaps, as V. B. Henning suggested, Takhsich is the Sogdian hypostasis of Tammuz, who annually returns to earth. It is also possible that Takhsich is an epithet that replaces the main name of the deity. In Sogdian iconography, Nana has many companions, one of the most important being the deity with an arrow in his hand. This image reminiscent of a play on words in Middle Persian - mir - âarrowâ and Tir (i) - the name of the Near Asian deity and the name of the planet Mercury, as well as the name of the deity, often identified with the Avestan Tishtriya, the genius of the star Sirius and the deity rain (Grenet, Marshak 1998, pp. 5â18). This interpretation once again showed the complexity of the tasks facing the researcher studying the ambiguous and multifaceted Sogdian paintings. B. I. Marshak solved such problems more than once with brilliance thanks to attention to detail, his erudition and the ability to see a well-known fact from a new perspective, which always led to unexpected discoveries in the history of culture. This was the essence of the researcher's method.[70]Thus, from small pieces, combining the reconstructing of figures from small details, analogies and logical analysis he solved the âjigsaw-puzzleâ of a painting in XXVI/3, the depiction of a festival with dancers, acrobats, masters of puppets, Dionysian mysteries and exposition of figures of gods.[72]

The form appears in the Sogdian calendar and is used to denote the month of November[67]------------------------------Studies by B. I. Marshak and F. Grene showed that the four-armed goddess, who plays the main role in the mural composition âLamentationâ, was correctly identified as Nana from the very beginning. At the same time, the Mesopotamian basis of the ritual depicted in the composition clearly manifested itself after studying the notes of Wei Jie and the Sogdian Manichaean fragment M 549. As can be judged from these written sources, the rite of mourning, which is known in the Near Asian myth of Tammuz, is led by âLady Nanaâ. On the mural, Nana, along with other gods and people, mourns a girl who could be Geshtinanna (Belili), the sister of Tammuz, or Persephone, the daughter of Demeter. In Mesopotamian myth Geshtinanna replaces Tammuz every year for several months. In Sogd, the image of Geshtinanna could merge with the image of Persephone. According to N. Sims-Williams, the Greek name of Demeter in his Sogdian adaptation Zhimat is mentioned in the text M 549, and this theonym could have penetrated into Sogdian from the Bactrian language.The Sogdian deity Takhsich was associated with Nana, whose name, according to the etymology proposed by K. Tremblay, means "Returning". Perhaps, as V. B. Henning suggested, Takhsich is the Sogdian hypostasis of Tammuz, who annually returns to earth. It is also possible that Takhsich is an epithet that replaces the main name of the deity. In Sogdian iconography, Nana has many companions, one of the most important being the deity with an arrow in his hand. This image reminiscent of a play on words in Middle Persian - mir - âarrowâ and Tir (i) - the name of the Near Asian deity and the name of the planet Mercury, as well as the name of the deity, often identified with the Avestan Tishtriya, the genius of the star Sirius and the deity rain (Grenet, Marshak 1998, pp. 5â18). This interpretation once again showed the complexity of the tasks facing the researcher studying the ambiguous and multifaceted Sogdian paintings. B. I. Marshak solved such problems more than once with brilliance thanks to attention to detail, his erudition and the ability to see a well-known fact from a new perspective, which always led to unexpected discoveries in the history of culture. This was the essence of the researcher's method.[70]Thus, from small pieces, combining the reconstructing of figures from small details, analogies and logical analysis he solved the âjigsaw-puzzleâ of a painting in XXVI/3, the depiction of a festival with dancers, acrobats, masters of puppets, Dionysian mysteries and exposition of figures of gods.[72]ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ

[5]. Marshak and Raspopova 1994, p. 197.[5a1]. ΠΣογδιανÏÏ ÎºÎ¹Î¸Î±ÏÏδÏÏ ÎÏει ÏÏ Î³ÎºÏιθεί με Ïον Î¸ÎµÏ ÎÏÏλλÏνα, αλλά είναι ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î±Ïίθανο ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î±Ï Î¸ÎµÏÏ Î½Î± εμÏανίζεÏαι ÏÏα κεÏαμεικά ÏÏα οÏοία εμÏανίζεÏαι μια καθιÏÏή μοÏÏή να Ïαίζει Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏγανο. Îι Σογδιανοί Î¼Î¿Ï Ïικοί είναι ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Ïιο κονÏά ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏολλÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏαÏαÏÏάÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏÏην ÎÏÏεÏη ÎÏÏαιÏÏηÏα και Ïην Î ÏÏιμη ÎÏ Î¶Î±Î½Ïινή ÏÎÏνη ενÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¸Î¹ÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎÏÏ Î¿ οÏοίοÏ, ÏÏ ÎÏακιÏÏηÏ, αÏεικονιζÏÏαν αÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î»Î»Î¹ÏÎÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏ Î²Î¬ÏβαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏοÏοÏÏε ενδÏμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¿Î¹Î¬Î¶Î¿Ï Î½ με εκείνα ενÏÏ Î Î¬ÏÎ¸Î¿Ï Î® ÏÏν ÏοÏικÏν ÎµÏ Î³ÎµÎ½Ïν ÏÎ·Ï Î¡ÏμαÏÎºÎ®Ï Î£Ï ÏίαÏ. [5a2]. Greek sophist of the Roman period Athens.[6]. Marshak and Raspopova 1994, p. 198.[7]. Marshak and Raspopova 1994, p. 202.[10]. Furniss, I. THE SOGDIANS.[15]. Mourning Scene. Panjikent, Tajikistan, south wall of main hall of Temple II, Wall painting, 6th c. CE, The State Hermitage Museum, SA-16236.[17]. pl. 6 in p. 156 of: V. G. Skoda (St. Petersburg)[20]. de la Vaissière 2003.[30]. Encyclopaedia Iranica, s.v. PERSONAL NAMES, SOGDIAN i. IN CHINESE SOURCES.[32]. Terracotta group of two seated women, perhaps Demeter and her daughter Persephone. Made at Myrina, north-west Asia-Minor (????), circa 180 BCE. Said to be from Asia-Minor. (The British Museum 1885,0316.1).[40]. ICOSMOS. Spring 2021.[45]. Grenet 2013.[50]. The Ohio State University.[55]. Sanping Chen 2019, p. 423.[60]. Grenet and Marshak 1998[65]. Qi Xiaoyan 2022.[67]. Qi Xiaoyan 2022.[70]. Shkoda 2013, pp. 156-157.[72]. Shkoda 2013, pp. 484.

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎhttps://www.jstor.org/stable/24048774

Marshak, B. I. and V. I. Raspopova. 1994. "Worshipers from the Northern Shrine of Temple II, Panjikent," Bulletin of the Asia Institute (New Series) 8 (The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia Studies From the Former Soviet Union), pp. 187-207.

https://sogdians.si.edu/sidebars/retr..., I. THE SOGDIANS Influencers on the Silk Roads. RETRACING THE SOUNDS OF SOGDIANA. Online exhibition by the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

https://dnkonidaris.blogspot.com/2022...

https://www.academia.edu/35720137/Div..., A. 2017. "Divine and Human Figures on the Sealings Unearthed from Kafir-kala," Japan Society for Hellenistic-Islam Archaeological Studies 24, pp. 203-212.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048351..., B., and V. Solov'ev. 1990. "The Architecture and Art of Kafyr Kala (Early Medieval Tokharistan)," Bulletin of the Asia Institute 4 (In honor of Richard Nelson Frye: Aspects of Iranian Culture), pp. 61-75. p. 61:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048767..., G. V. 1994. "Ancient Samarkand: Capital of Soghd," Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 8 (The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia Studies From the Former Soviet Union), pp. 81-99.

https://www.academia.edu/36102643/_Th..., M. 2017. "The Religion and the Pantheon of the Sogdiands (5thâ8th centuries CE) in Light of their Sociopolitical Structures,â Journal Asiatique 2017/2, pp. 191-209.

https://archive.org/details/legendsta..., B. 2002. Legends, Tales, and Fables in the Art of Sogdiana, New York.

https://www.academia.edu/23521408/%D0... of the State Hermitage Museum LXII. Sogdians, their precursors, contemporaries and heirs, Based on proceedings of conference âSogdians at Home and Abroadâheld in memoryof Boris Ilâich Marshak (1933â2006), St. Petersburg The State Hermitage Publishers 2013

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048897..., B. I. 1996. "The Tiger, Raised from the Dead: Two Murals from Panjikent," Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 10 (Studies in Honor of Vladimir A. Livshits), pp. 207-217.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24048903..., V. G. 1996. "Fifty Years of Archaeological Exploration in Panjikent," Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 10 (Studies in Honor of Vladimir A. Livshits), pp. 259-264.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arasi_0004-... Grenet, F. and B. Marshak. 1998. "Le mythe de Nana dans l'art de la Sogdiane," Arts Asiatiques 53, pp. 5-18.

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/new... la Vaissière, E. 2003. "Sogdians in China," The Silk Road 1 (2), pp. 23-27.

ICOSMOS. Spring 2021. Serial Transnational Nomination For World Heritage of Silk Roads, <http://www.iicc.org.cn/UserFiles/Arti...

https://www.academia.edu/24470615/Whe..., S., and F. Grenet. 2007. "Where Are the Sogdian Magi?," Bulletin of the Asia Institute (New Series) 21, pp. 159-177.

Grenet, F. 2013. "Refocusing Central Asia. Inaugural Lecture delivered on Thursday 7 November 2013. <https://books.openedition.org/cdf/429...

The Ohio State University. "An Introduction to Uzbekistan," The Ohio State University, <https://u.osu.edu/uzbekistan/history/... (11 Sept. 2022).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7817/... Chen. 2019. â'Godly Worm' and the 'Literati Prism' of Chinese Sources," Journal of the American Oriental Society 139.2, pp. 417-431.

https://www.academia.edu/23521408/%D0..., V. G. 2013. "Boris Marshak and Panjikent Painting (Researcher's Method)," in Sogdians, their precursors, contemporaries and heirs , St. Petersburg (The State Hermitage Publishers), pp. 147-158.

https://www.academia.edu/24461082/Le_..., F. and B. Marshak. 1998. "Le mythe de Nana dans l'art de la Sogdiane," Arts Asiatiques 53, pp. 5-18.

https://inf.news/en/travel/9871506597... Xiaoyan. 2022. "Frontier Time and Space, The introduction and continuation of Hellenistic culture in the ancient city of Sogdiana," <https://inf.news/en/travel/9871506597... (11 Sept. 2022).

Î ÎÎÎΠΠΡÎΣΦÎΤÎΣ ÎÎÎ ÎÎΥΤÎΣÎÎΣ - ÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ: 110922

September 9, 2022

THE ARCHIMEDES CODEX, Netz & Noel

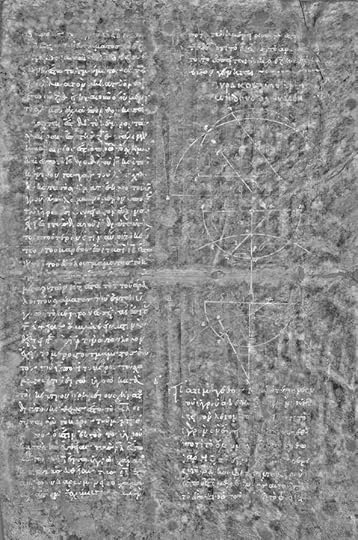

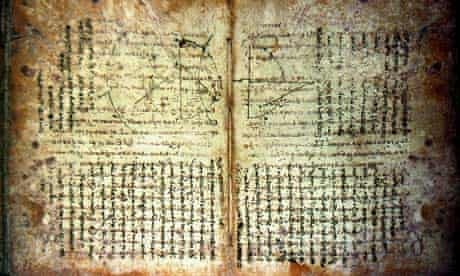

ΠΡεβίλ ÎεÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ ÏίÏÏÎµÏ Îµ ÏÏα μάÏια ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏαν άνοιξε Ïο e-mail ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¹Î± μÎÏα ÏÎ¿Ï 1998. ÎαιÏÏ ÏÏÏα εÏοίμαζε μια νÎα μεÏάÏÏαÏη και ÎκδοÏη ÏÎ»Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ³Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏιμήδη, και η ÏημανÏικÏÏεÏη Ïηγή κειμÎνÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎλειÏε ήÏαν Îνα γνÏÏÏÏ Î±Î»Î»Î¬ ÏαμÎνο Î²Ï Î¶Î±Î½ÏÎ¹Î½Ï ÏαλίμÏηÏÏο. Το ηλεκÏÏÎ¿Î½Î¹ÎºÏ Î³Ïάμμα Îλεγε ÏÏι Ïο ÏολÏÏιμο Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏειÏÏγÏαÏο είÏε αίÏÎ½Î·Ï ÎµÎ¼ÏανιÏÏεί. Îαι ήÏαν ÎÏοιμο να βγει Ïε δημοÏÏαÏία ÏÏν ÎÏίÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏη ÎÎα Î¥ÏÏκη...ΣÏον ÎÏδικα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î¿Ï Ï, ο ÎεÏÏ, μαζί με Ïον ÎÎ¿Ï Î¯Î»Î¹Î±Î¼ ÎοÎλ, ÎÏοÏο ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î¿Ï ÏÎµÎ¯Î¿Ï ÏÏο οÏοίο καÏÎληξε Ïο ÏαλίμÏηÏÏο μεÏά Ïην αγοÏά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎνανÏι 2.000.000 δολαÏίÏν αÏÏ Î¬Î³Î½ÏÏÏο ÏλειοδÏÏη (ÏημειÏÏÎον ÏÏι ÏÏη δημοÏÏαÏία ÏήÏε μÎÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï ÎµÏιÏÏ Ïία και Ïο ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÎºÏάÏοÏ), ÏαÏÎ±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸Î¿Ïν Ïο αÏίÏÏÎµÏ Ïο Ïαξίδι Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï ÎºÏδικα αÏÏ Ïη γÎννηÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Ï' Îνα μοναÏÏήÏι ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏνÏÏανÏινοÏÏÎ¿Î»Î·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην εξοÏία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎÎ³Î¯Î¿Ï Ï Î¤ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏην εμÏÏλεμη ÎÏ ÏÏÏη, μÎÏÏι Ïην ÏÏÏÏÏαÏη εÏανεμÏάνιÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÎÎ Î. ΣÏη διαδÏομή Î±Ï Ïή, ÎÏονÏÎ±Ï Î±Î½Î±ÎºÏ ÎºÎ»Ïθεί Ïαν ÏÏοÏÎµÏ ÏηÏάÏιο γÏαμμÎνο ÏÎ¬Î½Ï ÏÏο αÏÏαίο κείμενο, Ï ÏÎÏÏη ÏοβαÏÎÏ ÏθοÏÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Îμεινε ξεÏαÏμÎνο Ïε Î²Î¹Î²Î»Î¹Î¿Î¸Î®ÎºÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ï ÏÏγεια. ΣήμεÏα, ÏάÏη Ïε μια ενÏÏ ÏÏÏιακή διεθνή ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏγαÏία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιλαμβάνει ÏÏ Î½ÏηÏηÏÎÏ ÏειÏογÏάÏÏν, ειδικοÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î·Î»ÎµÎºÏÏÎ¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏεικÏνιÏηÏ, κλαÏικοÏÏ ÏιλολÏÎ³Î¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½Î¿Ï Ï Î¼Î±Î¸Î·Î¼Î±ÏικοÏÏ, Ïα ÏαμÎνα κείμενα και ÏÏεδιαγÏάμμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏιμήδη ÎÏÏονÏαι εÏιÏÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏο ÏÏÏ.ÎÏÏÏ ÏÏοκÏÏÏει αÏÏ Ïο βιβλίο, ÏμήμαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏδικα ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼ÏÏÏεÏαν να διαβαÏÏοÏν για ÏÏÏÏη ÏοÏά δείÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ ÏÏι ο ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î·Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïε μια ανÏίληÏη ÏÎ¿Ï "αÏείÏÎ¿Ï " ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î¼ÏÏοÏÏά αÏÏ Ïην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï , ήÏαν δε ο ÏÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î±ÏÏολήθηκε ÏοβαÏά με Ïη ÏÏ Î½Î´Ï Î±ÏÏική. ÎÏÏÏ Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει ο ÎεÏÏ, αν Ïο μαθημαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏγο, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏα αÏοκαλÏÏÏεÏαι Ï' Ïλο ÏÎ¿Ï Ïο εÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïο βάθοÏ, ÏÏοÏÏεθεί ÏÏÎ¹Ï Ïιο γνÏÏÏÎÏ ÏÏ Î¼Î²Î¿Î»ÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏη ÏÏ Ïική και Ïη μηÏανική, γίνεÏαι ολοÏάνεÏο ÏÏι ο ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î·Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ "Î Î ÎΠΣÎÎÎÎΤÎÎÎΣ ÎÎ ÎΣΤÎÎΩΠΠÎÎ¥ ÎÎÎΣΠΠÎΤÎ". " ... ΠκαÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏειÏογÏάÏÎ¿Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ είναι καθÏÎ»Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î»Î®. ΣÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα η καÏάÏÏαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν κακή ήδη Ïην εÏοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Ïο μελÎÏηÏε για ÏÏÏÏη ÏοÏά ο ΧάινμÏεÏγκ, ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î±ÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï 20Î¿Ï Î±Î¹Ïνα ... ΣήμεÏα ÏμÏÏ Ïο ÏειÏÏγÏαÏο διαβάÏÏηκε ÏÏο ÏÏÎ½Î¿Î»Ï ÏÎ¿Ï , ÏάÏη ÏÏη βοήθεια ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÏÏεÏε η ÏÏγÏÏονη ÏεÏνολογία. ΧÏηÏιμοÏοιήθηκε ÎÎ½Î±Ï ÏÏ Î½Î´Ï Î±ÏμÏÏ Î´Î¹Î±ÏÏÏÏν ÏεÏνικÏν. ÎξελιγμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏεÏνικÎÏ ÏηÏÎ¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏÏογÏάÏηÏÎ·Ï (ÏÎ¿Î»Ï ÏαÏμαÏική αÏεικÏνιÏη, αÏεικÏνιÏη ÏθοÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Î±ÎºÏίνÏν Χ), ÏεÏνικÎÏ ÎµÏεξεÏγαÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ βελÏιÏÏοÏοίηÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏηÏÎ¹Î±ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÎ¹ÎºÏναÏ, ÎµÎ½Ï ÏÏεδιάÏÏηκε και Îνα ÎµÎ¹Î´Î¹ÎºÏ Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÏÎ¼Î¹ÎºÏ Î±Î½Î±Î³Î½ÏÏίÏεÏÏ ÏαÏακÏήÏÏν (ÎCR) ... ΤÏία αÏÏ Ïα εÏÏά κείμενα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏιμήδη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏεÏιÎÏει Ïο ÏαλίμÏηÏÏο δεν Î±Î½ÎµÏ ÏίÏκονÏαι Ïε κανÎνα άλλο αÏÏ Ïα γνÏÏÏά ÏειÏÏγÏαÏα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏιμήδη, και Î±Ï ÏÏ Î±ÎºÏιβÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î¹ÏÏά ανεκÏίμηÏη Ïην αξία ÏÎ¿Ï . Îν δεν Ï ÏήÏÏε Ïο ÏαλίμÏηÏÏο, δεν θα γνÏÏίζαμε Ïα εν λÏÎ³Ï ÎÏγα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏιμήδη και εÏομÎνÏÏ Î· εικÏνα ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸Î± είÏαμε για Ïην εÏιÏÏημονική ÏÏοÏÏÏικÏÏηÏά ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸Î± ήÏαν ÏεÏιοÏιÏμÎνη και αÏελήÏ." (ÎÏÏ Ïην ÏαÏÎ¿Ï ÏίαÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÎºÎ´ÏÏεÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î ÎÎÎΤÎÎÎΣ)

Î Îγγλική ÎκδοÏη (AMAZON 2007) αναÏÎÏει Ïον ÎÏÏιμήδη ÏÏ 'Ïον μεγαλÏÏεÏο ÎαθημαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï ÎºÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ' και 'Îναν αÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î¼ÎµÎ³Î±Î»ÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î´Î¹Î±Î½Î¿Î·ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎζηÏαν ÏοÏÎ' (ÏÏÏλογοÏ, Ïελ. 1). ΦαίνεÏαι ÏÏι η ÎκδοÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î ÎÎÎΤÎÎÎÏ ÏÏÏÏοÏÏÏηÏε ονομαζονÏÎ¬Ï Ïον "Î Î ÎΠΣÎÎÎÎΤÎÎÎΣ ÎÎ ÎΣΤÎÎΩΠΠÎÎ¥ ÎÎÎΣΠΠÎΤÎ" ÏÏάÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏάγμαÏι εξεÏÏÏμιÏε ο ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎÎ±Ï ÏÏην Ïελ. 284! ..

ΠΡÎΣÎÎÎÎ Î: ΦαίνεÏαι ÏÏι κάÏοια ÏÏιγμή νÏÏÎ¯Ï ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î±ÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¿Ï Ï 1229, ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î±Ï Î¹ÎµÏÎαÏ, ονÏμαÏι ÎÏÎ¬Î½Î½Î·Ï ÎÏÏÏναÏ, ÏÏειάÏÏηκε ÏεÏγαμηνή για Îνα βιβλίο ÏÏοÏÎµÏ ÏήÏ, ÏήÏε λοιÏÏν μία ÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿Î³Î® ÎÏγÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν γÏαμμÎνη Ïε ÏεÏγαμηνή ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï 250 ÏÏÏνια νÏÏίÏεÏα και διÎγÏαÏε, ÏÏο καλÏÏεÏα μÏοÏοÏÏε, Ïο κείμενο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î¿Ï Ï Î±ÏÏ ÎµÎºÎµÎ¯Î½ÎµÏ ÏÏν ÏελίδÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î®Ïαν ακÏμη ÏÏήÏιμεÏ. ÎÏ ÏÏÏ ÎµÎ½ ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏεία ÏÏηÏιμοÏοίηÏε Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÎµÎ»Î¯Î´ÎµÏ Î³Î¹Î± να γÏάÏει Ïο κείμενο Î¼Î¹Î±Ï ÏÏ Î»Î»Î¿Î³Î®Ï ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏν ÏÏοÏÎµÏ ÏÏν Ïε οÏθή γÏνία ÏÏÏÏ Ïο ÎÏÏιμήδειο κείμενο αÏÏ ÎºÎ¬ÏÏ. ΣÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα ÏμÏÏ Î¿ ÎÏÏÏÎ½Î±Ï ÏÏειαζÏÏαν ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏη ÏεÏγαμηνή αÏÏ Ï, Ïι θα μÏοÏοÏÏε να ÏÏοÏÏÎÏει ο ÏαλιÏÏ ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´ÎµÎ¹Î¿Ï ÎºÏδικαÏ, οÏÏÏε εÏενÎβη καÏά Ïον ίδιο ÏÏÏÏο και Ïε άλλα εÏίÏÎ·Ï ÏημανÏικά και ÏÏÏα ÏαμÎνα, κείμενα ..... (Îλλά Î±Ï Ïή είναι μια άλλη ιÏÏοÏία.)[5]

ΠΡÎΣÎÎÎÎ Î': âThe safest general characterization of the European scientific tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Archimedes.â ή "ΠαÏÏαλÎÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î³ÎµÎ½Î¹ÎºÏÏ ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏμÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏ ÏÏÏαÏÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏÏι ÏÏ Î½Î¯ÏÏαÏαι αÏÏ Î¼Î¯Î± ÏειÏά Ï ÏοÏημειÏÏεÏν ÏÏον ÎÏÏιμήδη."

ÎÎÎ ÎΡΩΤÎÎÎ: ΦανÏάζεÏÏε - ÏÏÏÏ Î¸Î± ÏÏοÏιμοÏÏα και ÎµÎ³Ï ÎºÎ±Ï' αÏÏήν - Ïο ÏαλίμÏηÏÏο να αγοÏαζÏÏαν ÏελικÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïο 'ÎλληνικÏ' ÎημÏÏιο και να ανεÏίθεÏο η μελÎÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Ï.Ï. ÏÏον κ. Î ÎÎÎΤÎÎ ? ÎÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ να ανεÏίθεÏο Î¿Ï Î´ÎµÎ¯Ï ÎλληνÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î·Î³Î·ÏÎ®Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ θα αÏοÏολμοÏÏε να γÏάÏει ÏÏι ÎγÏαÏαν οι ÎÏÏαηλινoί ειδικοί Netz & Noel .. Σε Ïλην Ïην ομάδα ÏÏÏÏÏάμε Ïολλά ..

ΠΡÎΣÎÎÎÎ Î': The Newtonian program of reducing physical systems to geometrical representations obeying mathematical laws was taken from the Archimedean blueprint for science.And so, without Archimedes, there would be neither Galileo nor Newton. And for that matter, there would be no Boltzmann or Shannon either. Το ÎÎµÏ ÏÏνειο ÏÏÏγÏαμμα αναγÏÎ³Î®Ï ÏÏν ÏÏ ÏικÏν ÏÏ ÏÏημάÏÏν Ïε γεÏμεÏÏικÎÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏαÏαÏÏάÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î¿Î¹ οÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ Ï ÏακοÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïε μαθημαÏικοÏÏ Î½ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Ï ÏÏοήλθε αÏÏ Ïο ÏÏÎδιο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î¿Ï Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïην εÏιÏÏήμη. Îαι ÎÏÏι, ÏÏÏÎ¯Ï Ïον ÎÏÏιμήδη, δεν θα Ï ÏήÏÏε κανÎÎ½Î±Ï Galileo οÏÏε Newton, οÏÏε Boltzmann or Shannon .. [10]

ÎÎÎÎ ÎÎÎÎΣÎÎΥΣÎ: Archimedes is the most important scientist who ever lived. This conclusion can be reached as follows.The British philosopher A. N. Whitehead once famously remarked: âThe safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.â This judgment may sound outrageous, but in fact it is quite sober minded. Platoâs immediate followers, such as Aristotle, tried above all to refute or to refine Platoâs arguments.Later philosophers debated whether it was best to follow Plato or Aristotle. And so, in a real sense, all later Western philosophy is but a footnote to Plato.The safest general characterization of the European scientific tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Archimedes. By which I mean, roughly the same kind of genealogy that Whitehead meant for Plato applies to Archimedes. As an example, we need only to look at one of the most influential books of modern science, Galileoâs Discourses Concerning Two New Sciences. This book was published in 1638, by which time Archimedes had been dead for exactly 1,850 yearsâa very long time indeed.Yet throughout it, Galileo is in debt to Archimedes. Essentially, Galileo advances the two sciences of statics (how objects behave in rest) and dynamics (how objects behave in motion). For statics, Galileoâs principal tools are centers of gravity and the law of the balance. Galileo borrows both of these conceptsâ explicitly, always expressing his admirationâfrom Archimedes. For dynamics, Galileoâs principal tools are the approximation of curves and the proportions of times and motions. Both of which, once again, derive directly from Archimedes. No other authority is as frequently quotedor quoted with equal reverence. Galileo essentially started out from where Archimedes left off, proceeding in the same direction as defined by his Greek predecessor.This is true not only of Galileo but also of the other great figures of the so-called âscientific revolution,â such as Leibniz, Huygens, Fermat, Descartes, and Newton. All of them were Archimedesâ children.With Newton, the science of the scientific revolution reached its perfection in a perfectly Archimedean form. Based on pure, elegant first principles and applying pure geometry, Newton deduced the rules governing the universe. All of later science is a consequence of the desire to generalize Newtonian, that is, Archimedean methods.The two principles that the authors of modern science learned from Archimedes are:⢠The mathematics of infinity⢠The application of mathematical models to the physicalworldThanks to the Palimpsest,we now know much more about these two aspects of Archimedesâ achievement.

ΣΤÎÎ ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ (κÏιÏική καλοδεÏοÏμενη ..): Î ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î·Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ο Ïιο ÏημανÏικÏÏ ÎµÏιÏÏήμÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎζηÏε ÏοÏÎ. ÎÏ ÏÏ Ïο ÏÏ Î¼ÏÎÏαÏμα μÏοÏεί να ÏÏ Î½Î±Ïθεί ÏÏ ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï. Î ÎÏεÏανÏÏ ÏιλÏÏοÏÎ¿Ï A. N. Whitehead κάÏοÏε Ï ÏεÏÏήÏιξε: "ΠαÏÏαλÎÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î³ÎµÎ½Î¹ÎºÏÏ ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏμÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏ ÏÏÏαÏÎºÎ®Ï ÏιλοÏοÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏÏι Î±Ï Ïή ÏÏ Î½Î¯ÏÏαÏαι αÏÏ Î¼Î¹Î± ÏειÏά Ï ÏοÏημειÏÏεÏν ÏÏον ΠλάÏÏνα." ÎÏ ÏÏ Ïο αÏÏÏθεγμα μÏοÏεί να ακοÏγεÏαι εξÏÏÏενικÏ, αλλά ÏÏην ÏÏαγμαÏικÏÏηÏα είναι αÏοÏÎλεÏμα ÏÏÎ¯Î¼Î¿Ï ÏκÎÏεÏÏ. Îι άμεÏοι οÏαδοί ÏÎ¿Ï Î Î»Î¬ÏÏνοÏ, ÏÏÏÏ Î¿ ÎÏιÏÏοÏÎληÏ, ÏÏοÏÏάθηÏαν ÎºÏ ÏίÏÏ Î½Î± ανÏικÏοÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ή να βελÏιÏÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïα εÏιÏειÏήμαÏά ÏÎ¿Ï . ÎÏγÏÏεÏα οι ÏιλÏÏοÏοι ÏÏ Î¶Î®ÏηÏαν εάν ήÏαν καλλίÏεÏο ÎºÎ±Î½ÎµÎ¯Ï Î½Î± Î±ÎºÎ¿Î»Î¿Ï Î¸Î®Ïει Ïον ΠλάÏÏνα ή Ïον ÎÏιÏÏοÏÎλη. Îαι ÎÏÏι, Ï ÏÏ Î±Ï Ïήν Ïην Îννοια, Ïλη η μεÏαγενÎÏÏεÏη Î´Ï Ïική ÏιλοÏοÏία είναι μÏνον μια Ï ÏοÏημείÏÏη ÏÏον ΠλάÏÏνα.ΠαÏÏαλÎÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Î³ÎµÎ½Î¹ÎºÏÏ ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏμÏÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏ ÏÏÏαÏÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏαÏαδÏÏεÏÏ ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ ÏÏι αÏοÏελείÏαι αÏÏ Î¼Î¹Î± ÏειÏά Ï ÏοÏημειÏÏεÏν ÏÏον ÎÏÏιμήδη. Îε Î±Ï ÏÏ ÎµÎ½Î½Î¿Ï, ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï Ïο ίδιο ÎµÎ¯Î´Î¿Ï Î³ÎµÎ½ÎµÎ±Î»Î¿Î³Î¯Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Whitehead διαÏÏÏÏÏε για Ïον ΠλάÏÏνα και ιÏÏÏει εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î³Î¹Î± Ïον ÎÏÏιμήδη. Îια ÏαÏάδειγμα, ÏÏειάζεÏαι μÏνο να δοÏμε Îνα αÏÏ Ïα ÏλÎον ÏημανÏικά βιβλία ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½Î·Ï ÎµÏιÏÏήμηÏ, Ïο Discourses Concerning Two New Sciences [ÏÏαγμαÏεία εÏι ÏÎ·Ï Î¦Ï ÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Ï ÏÏ Ïην μοÏÏή διαλÏγÏν] ÏÎ¿Ï Galileo. ÎÏ ÏÏ Ïο βιβλίο εκδÏθηκε Ïο 1638, ÏÏαν ο ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î·Ï ÎµÎ¯Ïε ήδη Ïεθάνει ÏÏιν 1.850 ÏÏÏνια - ÏÏάγμαÏι ÏÎ¿Î»Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ÏÏ. ΩÏÏÏÏο, Ïε Ïλο Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο ÎÏγο, ο ÎÎ±Î»Î¹Î»Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Î±Î½Î±Î³Î½ÏÏίζει Ïην οÏειλή ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏον ÎÏÏιμήδη, Ïην οÏοίαν εκÏÏάζει ÏηÏά. ÎÏ ÏιαÏÏικά, ο ÎÎ±Î»Î¹Î»Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏÏοάγει ÏÎ¹Ï Î´Ïο εÏιÏÏÎ®Î¼ÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î£Î¤ÎΤÎÎÎΣ (ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¼ÏεÏιÏÎÏονÏαι Ïα ÏÏμαÏα εν ηÏεμία) και ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎÎÎÎΣ (ÏÏÏ Ïα ανÏικείμενα ÏÏ Î¼ÏεÏιÏÎÏονÏαι εν κινήÏει). Îια Ïην ÏÏαÏική, κÏÏια εÏγαλεία ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½Î±Î»ÏÏεÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ±Î»Î¹Î»Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ Ïο κÎνÏÏο βάÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ο νÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î¹ÏοÏÏοÏίαÏ. Î ÎÎ±Î»Î¹Î»Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Î´Î±Î½ÎµÎ¯Î¶ÎµÏαι και ÏÎ¹Ï Î´Ïο Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÎÎ½Î½Î¿Î¹ÎµÏ - ÏÏ Î»Î»Î®ÏειÏ, εκÏÏάζονÏÎ±Ï ÏάνÏα Ïον Î¸Î±Ï Î¼Î±ÏÎ¼Ï ÏÎ¿Ï - αÏÏ Ïον ÎÏÏιμήδη. Îια Ïη Î´Ï Î½Î±Î¼Î¹ÎºÎ®, Ïα κÏÏια εÏγαλεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ±Î»Î¹Î»Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ η ÏÏοÏÎγγιÏη ÏÏν καμÏÏ Î»Ïν και η αναλογία ÏÏν ÏÏÏνÏν και ÏÏν κινήÏεÏν. Îαι Ïα δÏο, για άλλη μια ÏοÏά, ÏÏοÎÏÏονÏαι αÏÎµÏ Î¸ÎµÎ¯Î±Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÎÏÏιμήδη. Îαμμία άλλη Î±Ï Î¸ÎµÎ½Ïία - ÏÎÏαν Î±Ï ÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î¿Ï Ï - δεν αναÏÎÏεÏαι ÏÏÏο ÏÏ Ïνά οÏÏε ÏαίÏει ίÏÎ¿Ï ÏεβαÏμοÏ. Î ÎÎ±Î»Î¹Î»Î±Î¯Î¿Ï Î¿Ï ÏιαÏÏικά ξεκίνηÏε αÏÏ ÎµÎºÎµÎ¯ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏαμάÏηÏε ο ÎÏÏιμήδηÏ, ÏÏοÏÏÏÏνÏÎ±Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïην ίδια καÏεÏÎ¸Ï Î½Ïη ÏÏÏÏ Î¿ÏίÏÏηκε αÏÏ Ïον Îλληνα ÏÏοκάÏοÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï . ÎÏ ÏÏ Î¹ÏÏÏει ÏÏι μÏνον για Ïο Îαλιλαίο αλλά και για ÏÎ¹Ï Î¬Î»Î»ÎµÏ Î¼ÎµÎ³Î¬Î»ÎµÏ ÏÏοÏÏÏικÏÏηÏÎµÏ ÏÎ·Ï Î»ÎµÎ³ÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î·Ï 'εÏιÏÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏαναÏÏάÏεÏÏ', ÏÏÏÏ Î¿ Leibniz, Huygens, Fermat, Descartes και Newton. Îλοι ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Ï ÏήÏξαν Ïαιδιά ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î¿Ï Ï. Îε Ïον ÎεÏÏÏνα, η ÏÏ Ïική ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎ·Î¼Î¿Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏαναÏÏάÏεÏÏ ÎÏθαÏε ÏÏην ÏελειÏÏηÏά ÏÎ·Ï Ïε ÏÎλεια ÎÏÏιμήδεια μοÏÏή. ÎαÏιζÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Ïε ÏαÏείÏ, κομÏÎÏ ÏÏÏÏÎµÏ Î±ÏÏÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ εÏαÏμÏζονÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Î¸Î±Ïή γεÏμεÏÏία, ο ÎεÏÏÏν ÏÏ Î½Î®Î³Î±Î³Îµ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï Î½ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¹ÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïο ÏÏμÏαν. Îλη η μεÏαγενÎÏÏεÏη εÏιÏÏήμη είναι ÏÏ Î½ÎÏεια ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏÎ¹Î¸Ï Î¼Î¯Î±Ï Î³ÎµÎ½Î¹ÎºÎµÏÏεÏÏ ÏÏν ÎÎµÏ ÏÏνειÏν, δηλαδή ÏÏν ÎÏÏιμήδειÏν μεθÏδÏν.Îι δÏο αÏÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Îμαθαν οι ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎµÎ¯Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½Î·Ï ÎµÏιÏÏÎ®Î¼Î·Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïον ÎÏÏιμήδη είναι:⢠Τα μαθημαÏικά ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏείÏÎ¿Ï â¢ Î ÎµÏαÏμογή μαθημαÏικÏν Ï ÏοδειγμάÏÏν ÏÏον ÏÏ ÏικÏκÏÏμο ..ΧάÏη ÏÏο ΠαλίμÏηÏÏο ÏÏÏα γνÏÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÎ¿Î»Ï ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏεÏα για Î±Ï ÏÎÏ ÏÎ¹Ï Î´Ïο ÏÏÏ ÏÎÏ ÏÏν εÏιÏÎµÏ Î³Î¼Î¬ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏÎ¹Î¼Î®Î´Î¿Ï Ï.

Pages from the Archimedes Palimpsest. Photograph: AP[20]

Pages from the Archimedes Palimpsest. Photograph: AP[20]ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[5]. Berggren 2008.[10]. Netz & Noel 2007, p. 291.[20]. <https://www.theguardian.com/books/201...

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎReviel Netz and William Noel. 2007. Î ÎÏÎ´Î¹ÎºÎ±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÏιμήδη, Ïα Î¼Ï ÏÏικά ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏαλίμÏηÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏον κÏÏμο, ΠολιÏεία.

Reviel Netz and William Noel. 2007. The Archimedes Codex: How a Medieval Prayer Book is Revealing the True Genius of Antiquityâs Greatest Scientist, Da Capo Press.

https://www.ams.org/notices/200808/tx..., J. L. 2008. Rev. of Reviel Netz and William Noel, The Archimedes Codex: How a Medieval Prayer Book is Revealing the True Genius of Antiquityâs Greatest Scientist , in Notices of the AMS, pp. 943-947.

https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do...

Henry Mendell. 2008. Rev. of. Reviel Netz and William Noel, The Archimedes Codex: How a Medieval Prayer Book is Revealing the True Genius of Antiquityâs Greatest Scientist, in Physics Today 61 (5), pp. 55-56.

August 25, 2022

PHRYGIAN & GREEK LANGUAGE

Î ÎÏÎ¸Î¿Ï ÏοÏ

Îίδα[1]ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÏÏ ÏÏο γνÏÏίζοÏ

με ÏήμεÏα, η ΦÏÏ

γική ήÏαν ÏÏενά ÏÏ

νδεδεμÎνη με Ïην Îλληνική, ÏÏÏÏ Î¬Î»Î»ÏÏÏε καÏά Ïην ÏÏγÏÏονη εÏοÏή Ï

ÏοÏÏήÏιξε ο Î. ÎÏμÏÏοÏ

λοÏ.[2] ÎÏ

Ïή η εÏιβεβαίÏÏη είναι ÏÏ

νεÏÎ®Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην άÏοÏη ÏοÏ

ÎÏει διαÏÏ

ÏÏθεί αÏÏ ÏοÏ

Ï Neumann, Brixhe και Ligorio and Lubotsky και με ÏολλÎÏ ÏαÏαÏηÏήÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏοÏ

δίνονÏαι αÏÏ Î±ÏÏαίοÏ

Ï ÏÏ

γγÏαÏείÏ.[3] Î ÏάγμαÏι ÏÏον ÎÏαÏÏλο ÏοÏ

ΠλάÏÏνοÏ, Plat. Crat. 410a, εÏιÏημαίνεÏαι:ΣÏκÏάÏηÏ: á½

Ïα ÏοίνÏ

ν καὶ ÏοῦÏο Ïὸ á½Î½Î¿Î¼Î± Ïὸ âÏῦÏâ μή Ïι βαÏβαÏικὸν á¾. ÏοῦÏο Î³á½°Ï Î¿á½Ïε ῥᾴδιον ÏÏοÏάÏαι á¼ÏÏὶν á¼Î»Î»Î·Î½Î¹Îºá¿ ÏÏνá¿, ÏανεÏοί Ïá¾½ εἰÏὶν οá½ÏÏÏ Î±á½Ïὸ καλοῦνÏÎµÏ Î¦ÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ ÏμικÏÏν Ïι ÏαÏακλίνονÏεÏ: καὶ ÏÏ Î³Îµ âá½Î´ÏÏâ καὶ Ïá½°Ï âκÏναÏâ καὶ á¼Î»Î»Î± Ïολλά. á¼ÏμογÎνηÏ:á¼ÏÏι ÏαῦÏα. ήÏοι [4] ΣÏκÏάÏηÏ: Î ÏÏÏεξε λοιÏÏν μήÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¯ αÏ

ÏÏ ÏÏ Ïνομα ÏÎ°Ï 410a εÎναι εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î²Î±ÏβαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏγήÏ. ÎιαÏί αÏ

ÏÏ Î´Îν είναι εÏκολο νά ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏη ÎºÎ±Î½ÎµÎ¯Ï Î¼Î Ïήν Îλληνική γλÏÏÏα, καί ακÏμη βλÎÏομε ÏÏι ÎÏÏι ÏÏ Î»Îνε οί ΦÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ Î¼Î Î¼Î¹ÎºÏή ÏÏοÏοÏοίηÏη. 'ÎÏίÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¯ ÏÏ Î°Î´ÏÏ (νεÏÏ) καί ÏοÏ

Ï ÎºÏÎ½Î±Ï (ÏκÏλοÏ

Ï ) καί άλλα Ïολλά. á¼ÏμογÎνηÏ: Τά ÏαÏαδÎÏομαι.

Î ÎÏÎ¸Î¿Ï ÏοÏ

Îίδα[1]ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÏÏ ÏÏο γνÏÏίζοÏ

με ÏήμεÏα, η ΦÏÏ

γική ήÏαν ÏÏενά ÏÏ

νδεδεμÎνη με Ïην Îλληνική, ÏÏÏÏ Î¬Î»Î»ÏÏÏε καÏά Ïην ÏÏγÏÏονη εÏοÏή Ï

ÏοÏÏήÏιξε ο Î. ÎÏμÏÏοÏ

λοÏ.[2] ÎÏ

Ïή η εÏιβεβαίÏÏη είναι ÏÏ

νεÏÎ®Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην άÏοÏη ÏοÏ

ÎÏει διαÏÏ

ÏÏθεί αÏÏ ÏοÏ

Ï Neumann, Brixhe και Ligorio and Lubotsky και με ÏολλÎÏ ÏαÏαÏηÏήÏÎµÎ¹Ï ÏοÏ

δίνονÏαι αÏÏ Î±ÏÏαίοÏ

Ï ÏÏ

γγÏαÏείÏ.[3] Î ÏάγμαÏι ÏÏον ÎÏαÏÏλο ÏοÏ

ΠλάÏÏνοÏ, Plat. Crat. 410a, εÏιÏημαίνεÏαι:ΣÏκÏάÏηÏ: á½

Ïα ÏοίνÏ

ν καὶ ÏοῦÏο Ïὸ á½Î½Î¿Î¼Î± Ïὸ âÏῦÏâ μή Ïι βαÏβαÏικὸν á¾. ÏοῦÏο Î³á½°Ï Î¿á½Ïε ῥᾴδιον ÏÏοÏάÏαι á¼ÏÏὶν á¼Î»Î»Î·Î½Î¹Îºá¿ ÏÏνá¿, ÏανεÏοί Ïá¾½ εἰÏὶν οá½ÏÏÏ Î±á½Ïὸ καλοῦνÏÎµÏ Î¦ÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ ÏμικÏÏν Ïι ÏαÏακλίνονÏεÏ: καὶ ÏÏ Î³Îµ âá½Î´ÏÏâ καὶ Ïá½°Ï âκÏναÏâ καὶ á¼Î»Î»Î± Ïολλά. á¼ÏμογÎνηÏ:á¼ÏÏι ÏαῦÏα. ήÏοι [4] ΣÏκÏάÏηÏ: Î ÏÏÏεξε λοιÏÏν μήÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¯ αÏ

ÏÏ ÏÏ Ïνομα ÏÎ°Ï 410a εÎναι εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î²Î±ÏβαÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±ÏαγÏγήÏ. ÎιαÏί αÏ

ÏÏ Î´Îν είναι εÏκολο νά ÏÏ ÏÏεÏίÏη ÎºÎ±Î½ÎµÎ¯Ï Î¼Î Ïήν Îλληνική γλÏÏÏα, καί ακÏμη βλÎÏομε ÏÏι ÎÏÏι ÏÏ Î»Îνε οί ΦÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ Î¼Î Î¼Î¹ÎºÏή ÏÏοÏοÏοίηÏη. 'ÎÏίÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±Î¯ ÏÏ Î°Î´ÏÏ (νεÏÏ) καί ÏοÏ

Ï ÎºÏÎ½Î±Ï (ÏκÏλοÏ

Ï ) καί άλλα Ïολλά. á¼ÏμογÎνηÏ: Τά ÏαÏαδÎÏομαι.ÎμεÏÎµÏ ÏηγÎÏ Î³Î¹Î± Ïην ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® αÏοÏελοÏν εÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î²ÏÎθηκαν ÏÏην κενÏÏική ÎναÏολία, Î±Ï ÏÎÏ Î´Îµ διακÏίνονÏαι Ïε δÏο κÏÏια ÏÏμαÏα: Î Ïαλαιά ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® (OPhr.) ή ΠαλαιοÏÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® ÏεÏιλαμβάνει εÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏεÏιÏÎ´Î¿Ï 800 ÎÏÏ 330 Ï.Χ., οι οÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÏÏηÏιμοÏοιοÏÏαν εÏιÏÏÏιο αλÏάβηÏο, βαÏιÏμÎνο ÏÏο ÎλληνικÏ.[5] Το ÏÏμα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏαÏÏίζει Ïα ÏεκμήÏια ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎÎ±Ï Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏεÏιλαμβάνει 118 εÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏÏονολογοÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏην ÎÏ ÏοκÏαÏοÏική ΡÏμαÏκή ÏεÏίοδο, Î±Ï ÏÎÏ Î´Îµ είναι γÏαμμÎÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏο ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ Î±Î»ÏάβηÏο και ÏεÏιÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ ÎºÏ ÏίÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±ÏάÏÎ±Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά ÏÏν βεβηλÏÏÏν. Îιά Ïην ÎÎα ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® ÏημειÏνεÏαι ÎµÎ´Ï Î· άÏοÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î§Ï. ΤζιÏζιλή[6], ÏÏι ÏÏακÏικÏÏ ÏÏÏκειÏαι ÏÏι για γλÏÏÏα αλλά γιά μιά αÏÏαÏκή ÎÏαÏκή διάλεκÏο! Îξίζει να ÏÏοÏÏεθεί ÏÏεÏικÏÏ ÏÏι και ο Woudhuizen ÏίÏÏÎµÏ Îµ αÏÏικÏÏ ÏÏι η ÎÎα ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® είÏε εÏηÏÏεαÏÏεί αÏÏ Ïην Îλληνική, η οÏοία ÏÏην Î. ÎεÏÏγειο αÏεÏÎλη Ïην lingua franca αÏÏ Ïην ÎλληνιÏÏική εÏοÏή και μεÏά, ÎµÏ ÏίÏκεÏο δε εν μÎÏÏ Î´Î¹Î±Î´Î¹ÎºÎ±ÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î¼ÎµÏαÏÏοÏÎ®Ï ÏÎ·Ï Ïε ÏεÏιÏεÏειακή διάλεκÏο ÏÎ·Ï ÎλληνικήÏ, άÏοÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏμÏÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏκεÏαÏε εν ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏεία.[6a1] ÎÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎλληνιÏÏικοÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ½Î¿Ï Ï Ï ÏάÏÏει μια ÏημανÏική εÏιγÏαÏή, η W-11 (εÏίÏÎ·Ï Î³ÏαμμÎνη ÏÏην ελληνική γÏαÏή), Ïην οÏοία οι μελεÏηÏÎÏ Î¸ÎµÏÏοÏν ÏÏ Ïνά ÏÏ Îνα ÏÏίÏο ÏÏάδιο ÏÎ·Ï Î³Î»ÏÏÏαÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î½Î¿Î¼Î¬Î¶ÎµÏαι ÎÎÏη ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® (MPhr.).

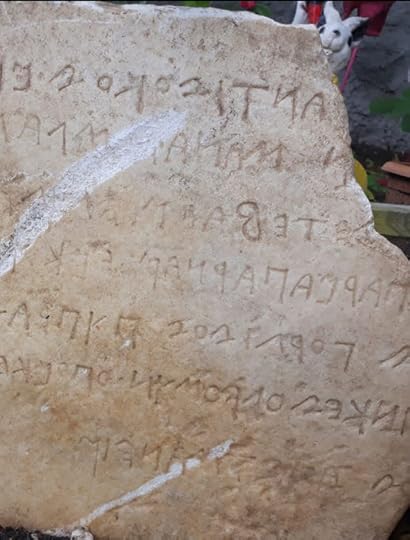

An inscription bearing the name of the ancient city was found at the excavation site in Gordion, the capital of the Phrygians[6a2]

An inscription bearing the name of the ancient city was found at the excavation site in Gordion, the capital of the Phrygians[6a2]Î ÎÏÏδοÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î±Ï ÏληÏοÏοÏεί γιά Ïην μεÏανάÏÏÎµÏ Ïη ÏÏν ΦÏÏ Î³Ïν αÏÏ Ïην Îακεδονία ÏÏην ÎικÏά ÎÏία ÏÏοÏθÎÏονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏι, καÏά Ïην γνÏμη ÏÎ¿Ï , οι ÎÏμÎνιοι ήÏαν αναÏολικοί άÏοικοι ÏÏν ΦÏÏ Î³Ïν, Hdt. 7.73.1. ΠΣÏÏάβÏν, Strab. 7.3.2, ÏÏονολογεί Ïην μεÏανάÏÏÎµÏ Ïη 'λίγο μεÏά Ïα ΤÏÏικά', ÎµÎ½Ï Î· εμÏάνιÏη 'βαÏβαÏικήÏ' κεÏÎ±Î¼ÎµÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïην ΧεÏÏÏνηÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¯Î¼Î¿Ï ÏαίνεÏαι να ÏιÏÏοÏοιείÏαι ÏÏην ΤÏÏάδα αÏÏ Ïον 11ο αιÏνα Ï.Χ.[7] Îι ÏληÏοÏοÏÎ¯ÎµÏ ÏÏν αÏÏαίÏν ÏÏ Î³Î³ÏαÏÎÏν ÏεÏί μεÏαναÏÏεÏÏεÏÏ ÏÏν ΦÏÏ Î³Ïν αÏÏ Ïην ΧεÏÏÏνηÏο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¯Î¼Î¿Ï ÏÏην ÎικÏά ÎÏία ÏαίνεÏαι να Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζονÏαι αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏγÏÏÎ¿Î½ÎµÏ Î³Î»ÏÏÏολογικÎÏ ÎÏÎµÏ Î½ÎµÏ. Î ÏάγμαÏι η Alonso θεÏÏεί ÏÏι η ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® ανήκει ÏÏον λεγÏμενο γλÏÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏÏο ÏÎ·Ï Î§ÎµÏÏονήÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ¯Î¼Î¿Ï , γεγονÏÏ Ïο οÏοίο εÏμηνεÏει Ïην βαθιά γενεÏική ÏÏÎÏη μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÎ·Ï Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï.[8] Îι δÏο γλÏÏÏÎµÏ Î±Î½Î±ÏÏÏÏθηκαν λοιÏÏν ÏÏο ίδιο γλÏÏÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏεÏιβάλλον, αλλά η μεÏανάÏÏÎµÏ Ïη ÏÏν ΦÏÏ Î³Ïν ÏÏην ÎναÏολία ÏÏα ÏÎλη ÏÎ·Ï Î´ÎµÏÏεÏÎ·Ï ÏιλιεÏÎ¯Î±Ï Ï.Χ. διÎκοÏε Ïη γεÏγÏαÏική ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏ Î½Î¬Ïεια. ΠΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ®, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Î±ÏÏÏ ÏείÏαι αÏÏ Îναν μεγάλο αÏÎ¹Î¸Î¼Ï ÎµÏιγÏαÏÏν αÏÏ Ïον ÎναÏο αιÏνα Ï.Χ. ÎÏÏ Ïον ÏÏίÏο αιÏνα μ.Χ., αÏοδείÏθηκε - καÏά Ïην ίδια ÏÏοÏÎγγιÏη - ÏÏι ÏÏην ÎναÏολία αÏεÏÎλη μία Îαλκανική γλÏÏÏική νήÏο, ÏεÏιβαλλÏμενη αÏÏ ÏολλÎÏ Î±Ï ÏÏÏÎ¸Î¿Î½ÎµÏ Î³Î»ÏÏÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½Î®ÎºÎ¿Ï Î½ ÏÏην γλÏÏÏική ομάδα ÏÎ·Ï ÎικÏαÏίαÏ. Îι ΦÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ ÎµÎ½ÏάÏθηκαν Ïε εκείνο Ïο ÏεÏιβάλλον ÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏολίαÏ, ÏÏÏÏ Î¼ÏοÏοÏν εÏκολα να αÏÎ¿Î´ÎµÎ¯Î¾Î¿Ï Î½ ÏολλÎÏ ÏολιÏιÏÏικÎÏ ÎµÏιÏÏοÎÏ, αλλά και οÏιÏμÎνα γλÏÏÏικά ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά. ΩÏÏÏÏο, ο αÏÏικÏÏ Î´ÎµÏμÏÏ Î¼Îµ Ïην αδελÏή Îλληνική γλÏÏÏα ανθίÏÏαÏο, καÏÎÏÏη δε ακÏμη Ïιο ιÏÏÏ ÏÏÏ Î¼ÎµÏά Ïον ÏÏÎ±Î´Î¹Î±ÎºÏ ÎµÎ¾ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÏÎ¼Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎναÏολίαÏ, ÎµÎ½Ï Î¿Î¹ εÏιγÏαÏÎÏ ÏαÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïα ÏÏοιÏεία για Ïη διεÏεÏνηÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î³ÎµÎ½ÎµÏÎ¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏ Î³Î³ÎνειαÏ.ÎΦÎÎΡΩÎÎΤÎÎΠΦΡΥÎÎÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎΡÎΦΠM-01a ΠΡÎΣ ΤÎÎÎΠΤÎÎ¥ ÎÎÎÎ (Midas Phrygian inscription M-01) [image error]

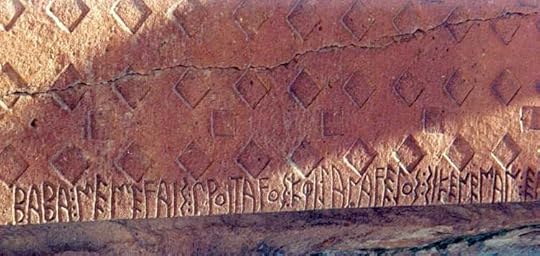

We have to note that this Phrygian alphabet, used in the above inscription of c 800 BC, is clearly of Greek association - origin.[9] Note the following excerpt from Young:[10]

If we put credence in the tales of Herodotos (I, 14) and of Pollux (IX, 83) that King Midas dedicated a throne at ÎÎÎΦÎÎ - Delphi, and that he married ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎ - Demodike the daughter of ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΩΠ- Agamemnon King of Kyme, we have evidence for contact, casual or regular, between eighth-century Phrygia and the Greek settlements of the west coast.

A COMMENT FOR THE Phrygian Inscription M-01a word by word: (a) ÎΤÎΣ is the name of the dedicator, found in the LGPN database of Greek personal names, the companion and lover of the Great Goddess, Agdistis - á¼Î³Î´Î¹ÏÏÎ¹Ï or Kybele[11](b) ÎΡÎÎÎÎFÎÎΣ can be interpreted as a patronymic adjective built on the Greek personal name ÎÏκιαÏ, also found in LGPN, (b*) ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎFÎΣ: αÏÏ Ïον Woudhuizen εÏμηνεÏεÏαι ÏÏ Î¹ÎµÏÎÎ±Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÏελεÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ³Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÏÏ ÏάÏ,[12] ÎµÎ½Ï ÎºÎ±Ïά Watkins η λÎξη ενδεÏομÎνÏÏ ÏÏ Î½Î´ÎεÏαι με Ïον ιεÏÎα κοίη ή κÏη ÏÏν Î¼Ï ÏÏηÏίÏν ÏÎ·Ï Î£Î±Î¼Î¿Î¸ÏάκηÏ.[14] (c) ÎÎÎÎÎ is the dative form referred to the receiver of the dedication, (d) ÎÎFÎÎΤÎÎÎ & (e) FANAKTEI (both in dative) are the Greek words λαÏαγÎÏÎ·Ï & άναξ mentioned in Linear B as ra-wa-ke-ta and wa-na-ka,[13](f) ÎÎÎÎΣ: 3rd. sing. preterite verb meaning "set (up)", "he has made", "has placed" he gave" or "he made" said to be a morphological isogloss shared between Armenian, Greek and Indo-Iranian. Note that δα is used for γᾶ, γῠsee f.e. "ÏάνÏÏν á¼Î´Î¿Ï á¼ÏÏαλÎÏ" (Hes. Th. 117). According to LSJ: á¼Î´Î¿Ï, εοÏ, ÏÏ, is the sitting-place, base. Îλ. εÏίÏÎ·Ï Paleolexicon, s.v. ÎÎÎÎΣ.CONCLUSION: IF THIS LANGUAGE IS NOT GREEK THEN WHAT KIND IS, GIVEN - ALSO - THAT IN THIS VERY FIRST ATTESTATION OF PHRYGIAN WE ALSO FIND ONE OF THE OLDEST ATTESTATIONS OF THE GREEK ALPHABET!? SOURCES USED: <http://www.palaeolexicon.com/Word/Sho..., LGPN name search, <http://mnamon.sns.it/index.php?page=E... LSJ lexicon

ΠεÏιγÏαÏή Î-01a ÏοÏ

Îίδα

ΠεÏιγÏαÏή Î-01a ÏοÏ

ÎίδαΣΥÎÎ ÎÎΡΩÎÎ ÎΠΠΤΠ'Î ÎÎÎΣÎÎÎÎ' ΤÎÎ¥ ÎΩÎÎÎ ÎÎ¥ÎÎÎ¥ 1993 [1912][20]

ÎΤÎΣ κÏÏιον Ïνομα, ÏÏβλ. ÎÏÏηÏ, ÎÏÏιÏ, ÎÏÏ Ï, Îλβαν. άÏε-α 'ÏαÏηÏ', ελλ. άÏÏαÎΡÎÎÎÎFÎÎΣ: ÎΡÎÎÎ ÏαÏÏÏÎ½Ï Î¼Î¹ÎºÏν (ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏκία ή ÎÏÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ) ή αιÏ. Î¿Ï Ï. ÏÏ Ïο Îλβ. άÏκε-α, λαÏιν. arca 'κιβÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¬Ïναξ' FÎÎΣ Ïήμα 'εÏοίηÏα, εÏοίηÏεν' λÎÎ¾Î¹Ï Î¸ÎµÏÏοÏμενη ανÏίÏÏοιÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏ ÎºÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÎÎÎΣ, Îλβ. bai Ï, 'εÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï Î½, εÏοίηÏα' Î ÎÏμÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï ÏημειÏνει Ïο ÎλληνοκαÏÏαδοκικÏν Ïήμα Î´Î¬Î¶Ï Ïημαίνον 'ÏοιÏ, εÏγάζομαι', ÏÏβλ. δαιδάλλÏ, ÎαίδαλοÏ

ÎÎÎÎΣ θεÏÏείÏαι Ïήμα ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸ÎμαÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïο νεοÏÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÏν ÎÎÎÎΤ 'ÏοιήÏη', Ïημαίνον 'εÏοίηÏε'. Το αÏÏικÏν ε- ÏÏ Î½Î¹ÏÏά Ïην αÏξηÏιν ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î¿ÏίÏÏοÏ

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎÎFOS: ίÏÏÏ ÏÏνθεÏον αÏÏ Ïο ακενανÏ- (εκ ÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÎºÎµÏ, ακÎομαι βλ. LSJ ) & λαFoÏ = λαÏÏ Î±Î½ÏίÏÏοιÏον ÏÏ ÎµÎ»Î»Î·Î½. ÎκεÏίλαοÏ

ÎÏÏική μελανÏμοÏÏη Ïιάλη με ÏείλοÏ, κεÏαμοÏÎ¿Î¹Î¿Ï ÎÏγοÏίμοÏ

& ζÏγÏάÏοÏ

ÎλειÏία, ÏÏÎ¼Î²Î¿Ï V ÎοÏδίοÏ

[100]

ÎÏÏική μελανÏμοÏÏη Ïιάλη με ÏείλοÏ, κεÏαμοÏÎ¿Î¹Î¿Ï ÎÏγοÏίμοÏ

& ζÏγÏάÏοÏ

ÎλειÏία, ÏÏÎ¼Î²Î¿Ï V ÎοÏδίοÏ

[100]ÎÎÎÎÎÎ-ΦΡΥÎÎÎÎ ÎÎ ÎÎΡÎΦΠΣΠÎΦÎÎΡΩÎÎΤÎÎΠΣΤÎÎÎ Vezirhan (B-05) ÎÎÎÎ¥ÎÎÎΣ

[image error]

Î ÏÏκειÏαι για εÏιγÏαÏή Ïε αÏβεÏÏολιθική ÏÏήλη ελληνοÏεÏÏÎ¹ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î¸Î¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î²ÏÎθηκε Ïε δÏο κομμάÏια ÏÏην κοιλάδα ÏÎ¿Ï Î£Î±Î³Î³Î±ÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ÎºÎ¿Î½Ïά ÏÏην ÏεÏιοÏή ÎεζιÏÏάν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏιλεÏζίκ. Î ÏÏήλη ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï 1,5 μÎÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏει ÏÏία ξεÏÏÏιÏÏά Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïα ÏÏο εÏÎ¬Î½Ï Î¼ÎÏοÏ. ΣÏην κοÏÏ Ïή διακÏίνεÏαι Ïο Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïο Î³Ï Î½Î±Î¹ÎºÎµÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏοÏÎ¿Î¼Î®Ï Î¼Îµ ανοιÏÏÎÏ Î±Î³ÎºÎ¬Î»ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î´Ïο ÏÎ»ÎµÏ ÏÎÏ. Î¥ÏάÏÏει Îνα ÏÏÎ·Î½Ï Ïε κάθε ÏÎÏι και ÎÎ½Î±Ï Î»ÎÏν κάÏÏ Î±ÏÏ ÎºÎ¬Î¸Îµ ÏÎÏι. ÎÏÎ³Ï Î±Ï ÏÏν ÏÏν ζÏÏν, ÏιÏÏεÏεÏαι ÏÏι Ïο Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïο ανÏιÏÏοÏÏÏεÏει Ïη μηÏÎÏα θεά Matar. ÎάÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Î±Ï ÏÏ ÎµÏ ÏίÏκεÏαι Ïο Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïο Î¼Î¹Î±Ï ÏÎºÎ·Î½Î®Ï ÏÏ Î¼ÏοÏÎ¯Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ïεικονίζει οÏθοÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ ÎºÎ±Î¸Î®Î¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Ï Î±Î½Î¸ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Ï. Το ÏÏίÏο Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïο δείÏνει Îναν ιÏÏÎα Ïε ÎºÏ Î½Î®Î³Î¹ κάÏÏÎ¿Ï . ÎάÏÏ Î±ÏÏ Ïα Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïα Ï ÏάÏÏει μια ÏαλαιοÏÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® εÏιγÏαÏή 13 γÏαμμÏν. Το κείμενο Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏεÏιβάλλεÏαι αÏÏ Î¼Î¹Î± Ïιο αÏÏÏÏεκÏα ÏαÏαγμÎνη ελληνική εÏιγÏαÏή 7 γÏαμμÏν, ÏÎ¿Ï ÏιÏÏεÏεÏαι ÏÏι ÏÏοÏÏÎθηκε εκ ÏÏν Ï ÏÏÎÏÏν. ÎÎ»ÎµÏ Î¿Î¹ γÏαμμÎÏ ÏÎ·Ï ÏαλαιοÏÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï ÎµÏιγÏαÏÎ®Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ γÏαμμÎÎ½ÎµÏ Î²Î¿Ï ÏÏÏοÏηδÏν, ÎµÎ½Ï Î· ελληνική εÏιγÏαÏή είναι δεξιÏÏÏÏοÏη. ΧÏονολογείÏαι ÏÏον 5ο αιÏνα Ï.Χ. Î ÏÏήλη ÎµÏ ÏίÏκεÏαι ÏÏο ÎÏÏÎ±Î¹Î¿Î»Î¿Î³Î¹ÎºÏ ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏνÏÏανÏινοÏÏοληÏ.[120]

Î Gorbachov 2008 ÏÏεÏικά με Ïην εÏιγÏαÏή αÏÏ Ïον Vezirhan (B-05) Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει ÏειÏÏικά ÏÏι, λÏÎ³Ï ÏÎ·Ï Î±Î½ÏιÏÏοιÏÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏην ÏÏÏÏαÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏάÏÎ±Ï Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î´Î¯Î³Î»ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎµÎ¹Î¼ÎÎ½Î¿Ï Î¼ÎµÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï sin-t imenan kaka oskavos kakey kan dedapitiy tubeti και ÏÎ¿Ï ÎλληνικοÏá½ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏεÏὶ Ïὸ ἱεÏὸν ÎºÎ±ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏãγãεÏήÏαι , á¼Ì δÏῦν á¼(κ)κÏÏαι, Î±Ï ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÎÏει να διαβαÏÏεί ÏÏα ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¬ ÏÏ sin timenan (γÏαμμÎÏ 1 και 8 ) ανÏιÏÏοιÏεί ÏÏο Ïὸ ἱεÏὸν ÏÏην Îλληνική εκδοÏή και ÏÏι αμÏÏÏεÏοι οι ÏÏοι αναÏÎÏονÏαι Ïε ιεÏÏ Î¬Î»ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÏÎÎ¼Î¹Î´Î¿Ï (γÏαμμή 3: ÎÏÏίμηÏοÏ· ÏημειÏÏÏε ÏÏι η κοÏÏ Ïή ÏÎ»ÎµÏ Ïά ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏÎ®Î»Î·Ï ÎµÎ¯Î½Î±Î¹ διακοÏμημÎνη με μια εικÏνα ÏÎ·Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¬Ï Î¼Îµ Ïην ιδιÏÏηÏά ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏ ÏÏÏÎ½Î¹Î±Ï Î¸Î·ÏÏν). Σε Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο ÏλαίÏιο, η ÏαÏÏιÏη ÏÎ·Ï Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï Î¼Î¿ÏÏÎ®Ï Î¼Îµ Ïο ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÏ ÏÎÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï ÏÏοκÏÏÏει αβίαÏÏα και λαμβάνει ÏεÏαιÏÎÏÏ ÎµÏιβεβαίÏÏη αÏÏ Ïην γÏαÏική ÏαÏαλλαγή t1emeney (D sg.) ÏÏην αÏÏδοÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±ÏάÏÎ±Ï (γÏαμμή 13), ÏÎ¿Ï ÏαÏεμÏιÏÏÏνÏÏÏ ÎµÏιβεβαιÏνει Ïην οδονÏική αξία ÏÎ¿Ï ÏÏ Î¼Î²ÏÎ»Î¿Ï Ïε μοÏÏή βÎÎ»Î¿Ï Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î±Î½ÏιÏÏοιÏεί ÏÏο ÎÏ ÏÏο-ÎινÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÏÏμβολο ti-ÏÏÏÏ Î¿ Woudhuizen Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει αÏÏ Ïο 1982-3.[125]

ΣÏμÏÏνα με Ïην εÏιγÏαÏή: ο ÎÎ±Î»Î»Î¯Î±Ï [kaliyaâ¹sâº] ανήγειÏε - á¼Î½ÎθεÌκεν [⺠ti(:)tedat] ÏÎÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï / ιεÏÏ [tâ imenan / timena-, t1emene-], ÏιθανÏÏ ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïιμήν ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÏÎÎ¼Î¹Î´Î¿Ï [artimitos] ÎÏÎ±Î½Î±Î¯Î±Ï Î® ÎÏÎ·Î½Î±Î¯Î±Ï Î® ÎÏÎ®Î½Î·Ï Î® ÏÏν Ï Î´Î¬ÏÏν [kraniyas'] η οÏοία άλλÏÏÏε ÏÏ Î ÏÏνια θηÏÏν εικονίζεÏαι ÏÏην Î±Î½Î¬Î³Î»Ï Ïη ÏÏήλη εν μÎÏÏ Î»ÎµÏνÏÏν & ÏÏηνÏν.[130] Îξίζει να ÏημειÏθεί ÎµÎ´Ï ÏÏι ο ΦÏÏÎ³Î·Ï ÏÏÏαÏιÏÏÎ·Ï ÏÏο ÎÏγο Î ÎÏÏÎµÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î¤Î¹Î¼Î¿Î¸ÎÎ¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎιλήÏÎ¿Ï Î±Ïοκαλεί ÏÏον ÏÏ. 160 Ïην θεά "á¼ÏÏιμιÏ" (ÏÏ. 160),[132] ÏαÏαÏλήÏια με Ïο ÎµÎ´Ï artimitos. ΣημειÏÏÏε ÏÏι ÏÏην εÏιγÏαÏή Î-01 ÏÎ¿Ï Îίδα η ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® ÎÎÎÎΣ ÎÏει ομοίÏÏ Ïο νÏημα ÏÎ¿Ï 'ανεγείÏÏ', ÏαÏάβαλε Ïο 'ÏάνÏÏν á¼Î´Î¿Ï á¼ÏÏαλÎÏ'! ÎÏοιοÏ, ÏÏ Î½ÎµÏÎ¯Î¶Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ Ïον ÏÏολιαÏÎ¼Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎµÏιγÏαÏήÏ, ÏÏοÏÏÏήÏει Ïε κακÎÏ [kakos] ενÎÏÎ³ÎµÎ¹ÎµÏ / ÎºÎ±ÎºÎ¿Ï ÏγήÏει Ïε βάÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Î¹ÎµÏÎ¿Ï Î® κÏÏει δÏÏν - ÏιθανÏÏ Î±ÏÏ ÏαÏακείμενο ιεÏÏ Î±Î»ÏÏλλιον - Î±Ï ÏÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ οι εÏίγονοί ÏÎ¿Ï Î¸Î± Ï ÏοÏÏοÏν δεινά .. αναÏαÏάγονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏ ÏοÏοιημÎνη, ÏÏεÏεÏÏÏ Ïη ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® αλλά και Îλληνική ÏÏάÏη ÏεÏί ÏιμÏÏÎ¯Î±Ï Î±Ï ÏÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÎµÎ½ÎµÏγοÏν ανÏÏÎ¹ÎµÏ ÏÏάξειÏ.[135] ÎÏιγÏαμμμαÏικά αναÏÎÏÎ¿Ï Î¼Îµ ÏÎ¹Ï ÏÏÏÏθεÏÎµÏ Î±Î½ÏιÏÏοιÏίεÏ: ÏÎκμÏÏ, ÏÎκμαÏ, Ïήμα, ÏÏιον [tekmor, tekmar], και [key] καθÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην εÏλογη Ï ÏÏθεÏη ÏÏι Ïα ÏÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¬ ÏαÏάγÏγα ÏÏν IE *nep(ÅÌ)t- και *neptih2- εÏιβεβαιÏνονÏαι Ïε Î±Ï ÏÏ Ïο κείμενο Ïε ÏολλÎÏ Î´Î¹Î±ÏοÏεÏικÎÏ ÏεÏιÏÏÏÏειÏ.[140]

ΦÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ & ÎÎ¿Ï ÏάÏÎ¹Î¿Ï ÏολιÏιÏμÏÏ

Î Hammond[150] λίγο ÏÎ¿Î»Ï Î³ÏάÏει ÏÏι η εξάÏλÏÏη ÏÏν ΦÏÏ Î³Ïν ÏÏην Îακεδονία ÏÎ±Ï ÏίζεÏαι με Ïην εξάÏλÏÏη ÏÏν ÏÏοιÏείÏν ÏÎ¿Ï ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÏαÏίαÏ/Lausitz. ÎÏ ÏÏ Î´ÎµÎ½ Ïημαίνει αναγκαÏÏικά ÏÏι οι ΦÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ ÎºÎ±ÏάγονÏαι αÏÏ Ïην ÎÎ¿Ï ÏαÏία, ÏμÏÏ ÎµÏ' Î±Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏάÏÏει ÎλλειÏη ÏÏοιÏείÏν & αÏάÏεια. ÎÏλÏÏ, ÏÏο ζοÏÏαν ÏÏην ÏημεÏινή ÎÏÏειο Îακεδονία, δÎÏÏηκαν Ïην εÏίδÏαÏη ÏÎ¿Ï ÏολιÏιÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¿Ï ÏαÏίαÏ, Ï Î¹Î¿Î¸ÎÏηÏαν κάÏοια ÏÏοιÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎºÎ±Î¹ καÏÏÏιν Ïα διÎδÏÏαν με Ïην εξάÏλÏÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÏÏην νοÏιÏÏεÏη Îακεδονία και Ïην νÏÏια ÎÎ»Î»Ï Ïίδα.[155]

Î Hammond ÏιÏÏεÏει ÏÏι ÏÏÏÏεÏÎ¿Ï Ïα ÏÏν ÎÏÏ Î³Ïν ÏÏη Îακεδονία ÏÏιν αÏÏ Ïον 8ο αιÏνα Ï.Χ. ήÏαν ÏιθανÏÏ Î· ÎδεÏÏα, ÏÏο βÏÏειο άκÏο ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεÏÎ¼Î¯Î¿Ï , αÏÏ Ïο οÏοίο ÏήÏε Ïο Ïνομά ÏÎ·Ï Î· ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® λÎξη για Ïο νεÏÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ κονÏά ÏÏην οÏοία βÏίÏκονÏαν οι ÏεÏίÏημοι κήÏοι ÏÎ¿Ï Îίδα.[160]Τα Ï ÏÏλοιÏα ÏÎ¿Ï Î»Îει ÏμÏÏ Î³ÎµÎ½Î½Î¿Ïν κάÏοια ÏÏγÏÏ Ïη ÏÏον αÏοÏά ÏÏην ÎδεÏÏα, ÏÎ¹Ï ÎιγÎÏ ÎºÎ±Î¹ Ïην ÎεÏγίνα. Îια να ÏαÏÎ±Î¼ÎµÎ¯Î½Î¿Ï Î½ ιÏÏÏ Ïοί, Ï ÏοÏÏηÏίζει ο ίδιοÏ, οι ÎÏÏÎ³ÎµÏ ÎÏÏεÏε να ελÎγÏÎ¿Ï Î½ Ïην ÏεÏιοÏή ÏεÏί Ïην Ïεδιάδα ÏÎ¿Ï ÎξιοÏ. Îία αÏÏ ÏÎ¹Ï ÎµÏÎ¯Î¶Î·Î»ÎµÏ ÏÏÏÏ ÎλεγÏο θÎÏÎµÎ¹Ï Î®Ïαν Î±Ï Ïή ÏÎ¿Ï Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î¿Î¹ÎºÎ¹ÏÎ¼Î¿Ï ÏÎ·Ï ÎεÏγίναÏ, ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿Î½Î¿Î¼Î±Î¶ÏÏαν αÏÏικÏÏ ÎδεÏÏα και μεÏονομάÏÏηκε Ïε ÎιγÎÏ Î±ÏÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎακεδÏÎ½ÎµÏ ÏÏαν Ïην καÏÎλαβαν. ÎÎÏÏι εκείνη Ïην εÏοÏή, ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï Î±ÏÏ Ïο 1140 ÎÏÏ ÏεÏίÏÎ¿Ï Ïο 800 Ï.Χ., η ÎεÏγίνα-ÎδεÏÏα ήÏαν - ÏÏμÏÏνα με Ïον Hammonds ÏάνÏα - Îνα αÏÏ Ïα μεγάλα κÎνÏÏα ÏÎ·Ï Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¯Î±Ï. Τα λÏγια ÏÎ¿Ï Hammond Ï ÏοδηλÏÎ½Î¿Ï Î½ Ïην ÏÏαÏξη δÏο ÏÏλεÏν με Ïο Ïνομα ÎδεÏÏα, μία η ÏημεÏινή ÎδεÏÏα (βÏÏεια ÏÎ¿Ï ÎεÏÎ¼Î¯Î¿Ï ) και η άλλη ÏÏη ÎεÏγίνα (βÏÏεια ÏÎ·Ï Î Î¹ÎµÏίαÏ), μεÏÎÏειÏα ÎιγÎÏ.ÎαÏαληκÏικά ΣÏÏλια ΣÏμÏÏνα με ÏÏ Î³ÎºÏιÏική μελÎÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Obrador-Cursach βαÏιÏθείÏα Ïε Îνα ÏÏνολο ιÏογλÏÏÏÏν αμÏÏÏεÏÎµÏ Î· Îλληνική και η ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® μοιÏάζονÏαι 34 αÏÏ Ïα εξεÏαÏθÎνÏα ÏÏην μελÎÏη 36 ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά.[200] Τα ÏαÏακÏηÏιÏÏικά Î±Ï Ïά ήÏαν ÏÏνηÏικά, μοÏÏολογικά, λεξιλογικά,[205] και η εξÎÏαÏή ÏÎ¿Ï Ï ÎºÎ±ÏÎδειξε Ïην ÏÏ Î½Î¬Ïεια ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ®Ï - ÎλληνικήÏ. ÎÏÏ Ïην ÏÎ»ÎµÏ Ïά ÏÎ¿Ï Î¿ Woudhuizen ÎÏει ομοίÏÏ ÎºÎ±ÏαÏÏίÏει καÏάλογο ανάλογÏν λÎξεÏν μεÏÎ±Î¾Ï ÏÏν δÏο γλÏÏÏÏν, εÏγαζÏÎ¼ÎµÎ½Î¿Ï Î¼Îµ βάÏη ÏÎ¹Ï Ï ÏάÏÏÎ¿Ï ÏÎµÏ ÎµÏιγÏαÏÎÏ, ο οÏÎ¿Î¯Î¿Ï ÏεÏιλαμβάνει 167 ÏαÏαÏλήÏÎ¹ÎµÏ Î»ÎξειÏ,[210] ÏÏÎ¹Ï Î¿ÏÎ¿Î¯ÎµÏ ÏμÏÏ Î¸Î± ÏÏÎÏει να ÏÏοÏÏεθοÏν και άλλεÏ![220]

ΣÎÎÎÎΩΣÎÎΣ[1]. ΣÏην Ï ÏÏ Ïον Nathaniel Hawthorne εκδοÏή ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÏÎ¸Î¿Ï ÏÎ¿Ï Îίδα, η κÏÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î±ÏιλÎα μεÏαÏÏÎÏεÏαι Ïε ÏÏÏ ÏÏ Î¬Î³Î±Î»Î¼Î± ÏÏαν Î±Ï ÏÏÏ Ïην Î±ÎºÎ¿Ï Î¼Ïά (εικÏνα Ï ÏÏ Walter Crane γιά Ïην ÎκδοÏη ÏÎ¿Ï 1893).[2]. ÎÏμÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï, Î. 1993 [1912], Ïελ. 429-452.[3]. Obrador-Cursach. 2019, p. 238.[4]. μÏÏ. Îλία ÎÎ¬Î³Î¹Î¿Ï , Îθήνα (ÎαÏαÏÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï).[5]. Obrador-Cursach. 2019, p. 233, nn. 2,3; Anfosso 2019, pp. 1-2.[6]. Anfosso 2019, p.; Tzitzilis 2013. Το αÏÏÏÏαÏμα αÏÏ Ïον ΤζιÏζιλή ÎÏει ÏÏ ÎµÎ¾Î®Ï: "the Neo-Phrygian inscriptions, found in several places of central Anatolia, are actually written in a Greek, and more specifically in an archaic Achaean dialect, with some phonetic peculiarities that should be attributed to Anatolian influence".[6a1]. Woudhuizen 2008-2009, p. 181: The exclusion of New Phrygian forms from the demonstration of the intimate relationship of Phrygian with Greek in the aforesaid work was intentional because I believed at that time that New Phrygian was influenced by the lingua franca in the east-Mediterranean region from the Hellenistic period onwards, i.c. Greek, to the extent that it actually was well on its way to become a provincial dialectal variant of Greek. I now hold this to be an error of judgment.. [6a2]. https://arkeonews.net/an-inscription-.... Îλ. <https://smerdaleos.wordpress.com/cate.... ÎÏίÏηÏ: ÎανÏÎ»ÎµÎ´Î¬ÎºÎ·Ï 2016, Ïελ. 55-56.[8]. Anfosso 2021. [9]. Young 1969, p. 253. ÎμÏÏ Î· ÏÏονική ÏÏοÏοÏεία ÏÎ¿Ï ÎÎ»Î»Î·Î½Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î±Î»ÏαβήÏÎ¿Ï ÎνανÏι ÏÎ¿Ï Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ¿Ï Î´ÎµÎ½ θεÏÏείÏαι δεδομÎνη![10]. Young 1969, p. 253.[11]. Young 1969, p. 262.[12]. Woudhuizen 2008-2009, pp. 194-195. [13]. Î Obrador-Cursach θεÏÏεί Ïο ÎÎFÎÎΤÎÎÎ ÏÏ Î¦ÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÏ Î´Î¬Î½ÎµÎ¹Î¿ αÏÏ Ïο ÎÏ ÎºÎ·Î½Î±ÏÎºÏ ra-wa-ke-ta (Obrador-Cursach 2019, p. 240). ΣÏην ίδια θÎÏη ÏÏολιάζεÏαι η λÎξη άναξ και Ïο ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÏ Î±Î½ÏίÏÏοιÏο.[14]. LSJ, s.v. ÎÎ¿Î¯Î·Ï or ÎÏηÏ, Î¿Ï , á½, priest in the mysteries of Samothrace, Hsch., who also has κοιᾶÏαι· ἱεÏᾶÏαι, κοιÏÏαÏο· á¼ÏιεÏÏÏαÏο, καθιεÏÏÏαÏο.[20]. ÎÏμÏÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î¿Ï 1993 [1912], Ïελ. 441, 442 κ.ε.[100]. Young 1969, p. 295: The cup painted by the Attic craftsman Klitias ÎλειÏίαÏ, found by the Koertes in Tumulus V, bears the sign in EAPA4'%EN; it dates from about the same time as the Phrygian inscription, <https://smb.museum-digital.de/index.p.... https://www.phrygianmonuments.com/vez.... Woudhuizen 2008-2009, p. 190, n. 11.[130]. Î Obrador-Cursach (Obrador-Cursach 2018, p. 75) αναγιγνÏÏκει Ïο kraniyas ÏÏ ÎºÏηναία ή ÏÏν ÏηγÏν. ÎαÏ' άλλην εκδοÏή μÏοÏεί η λÎξη να αναγνÏÏθεί ÏÏ ÎÏαναία, ÏαÏαÏÎμÏονÏÎ±Ï ÏÏην ÎÏαναία Îθηνά! Î ÎÏαναία Îθηνά, Paus. 10.34.7 διÎθεÏε Î½Î±Ï ÏÏην ÎλάÏεια, ÏÏÎ¹Ï ÏλαγιÎÏ ÏÎ¿Ï Î²Î¿Ï Î½Î¿Ï ÎαλιδÏÏÎ¼Î¿Ï Î¦Î¸Î¹ÏÏιδοÏ. ΣÏην αÏÏαία εÏοÏή ήÏαν μÎÏÎ¿Ï Î»Î±ÏÏÎµÎ¯Î±Ï ÏÏν ÎοκÏÏν, ÏÏÎ¿Ï Ïιμή ÏÎ·Ï Î¸ÎµÎ¬Ï ÎθηνάÏ, κÏÏÎ·Ï ÏÎ¿Ï ÎιÏÏ. ÎÏείÏια ÏÏζονÏαι μÎÏÏι ÏήμεÏα. ÎναÏÎÏει ο αÏÏÎ±Î¯Î¿Ï ÏεÏιηγηÏÎ®Ï Î Î±Ï ÏÎ±Î½Î¯Î±Ï ÏÏα ΦÏκικά, ÏÏÏ ÏÏο Î½Î±Ï Ï ÏηÏεÏοÏÏαν μÏνο νεαÏά αγÏÏια μÎÏÏι Ïην εÏηβεία ÏÎ¿Ï Ï. Î ÏÎ¿Ï Ïιμήν ÏÎ·Ï ÎÏÎ±Î½Î±Î¯Î±Ï ÎÎ¸Î·Î½Î¬Ï Î¿Î¹ αÏÏαίοι κάÏοικοι είÏαν κÏÏει και νÏμιÏμα ÏÎ·Ï ÏÏλεÏÏ, με ÏαÏάÏÏαÏη ÏÎ·Ï ÎÎ¸Î·Î½Î¬Ï Î¼Îµ κÏÎ¬Î½Î¿Ï (ÎομιÏμαÏÎ¹ÎºÏ ÎÎ¿Ï Ïείο ÎθηνÏν). Îιά Ïην ÏÏοκαÏάληÏη ÏÎ¿Ï Hammond βλ. Î ÎÏÏα (Î ÎÏÏÎ±Ï 1973).[132]. Anfosso 2021.[135]. Obrador-Cursach 2019, pp. 108-109. Πκοινή μοÏÏή ÏÎ·Ï ÎºÎ±ÏάÏÎ±Ï ÏÏην Îλληνική & ΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® εκÏιμάÏαι ÏÏ Î¬Î»Î»Î¿ Îνα ÏεκμήÏιο ÏÏν εÏαÏÏν.[140]. Hämmig 2013.[150]. Hammond 1962, pp. 707=710.[155]. <https://smerdaleos.wordpress.com/2014.... ÎανÏÎ»ÎµÎ´Î¬ÎºÎ·Ï 2016, Ïελ. 50-51, Ïημ. 9; Hammond 1972, pp. 410-411. ÎαÏά Ïον Hammond oί ÎÏÏγοι είναι «the Lausitz invaders»(Ïελ. 305 κ.Î.), ÏÎ¿Ï ÎξελληνίÏθηκαν (Ïελ. 72), άÏÎ¿Ï Â«they were defeated by Odysseus inThesprotia» (Ïελ. 381)! [200]. Obrador-Cursach 2019, p. 238.[205]. Obrador-Cursach 2019, p. 239, table 1.[210]. Woudhuizen 2008-2009, pp. 183-191.[220]. Hämmig 2013. Îλ. και ÏαÏαÏάνÏ.

ÎÎÎÎÎÎÎΡÎΦÎÎ

https://smerdaleos.wordpress.com/2014...

smerdaleos, s.v. ΠΦÏÏ Î³Î¹ÎºÎ® γλÏÏÏα #1: Î ÏολεγÏμενα