Dimitrios Konidaris's Blog, page 3

June 4, 2024

TENDERNESS - EMOTIONS - PATHOS IN ANCIENT ART: AMARNA & HELLENISTIC..

ΤΡΥΦΕΡΟΤΗΤΑ ΣΤΗΝ ΑΝΑΚΤΟΡΙΚΗ ΕΙΚΟΝΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ ΤΗΣ AMARNA: ΜΙΑ ΑΙΓΑΙΑΚΗ ΕΙΣΡΟΗ??

[image error]

[image error] Figure 7Amarna relief from Hermopolis Magna, the Brooklyn Museum, New York, accession number 60.197.8

Shocking, based on the intimacy, Fragment of a Stela of the Royal Family; New Kingdom (Dynasty 18th; Tell el-Amarna; Limestone; Inv. No. E 11624 Musée du Louvre

Shocking, based on the intimacy, Fragment of a Stela of the Royal Family; New Kingdom (Dynasty 18th; Tell el-Amarna; Limestone; Inv. No. E 11624 Musée du LouvreΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΟ ΠΑΘΟΣ ΣΤΗΝ GANDHARA ΑΛΛΑ ΚΑΙ ΣΤΟΝ ΓΟΤΘΙΚΟ ΡΥΘΜΟ! [image error] Fig. 13. Head of a Devata. NW Pakistan, 3rd c. A.D. or later. H. 6 2 inches.Ross Collection. 31.191, MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

Rowland 1965, p. 121:

The Antonine revival of the Hellenistic style, with its deep pictorial undercutting and wildly dynamic expression of movement and pathos, makes its appearance in the complex Gandhara carvings of the mid-second century.20

Η παρουσίαση της ανθρώπινης μάσκας ως ενδεικτικής των εσωτερικών συναισθηματικών καταστάσεων ήταν μια καινοτομία των γλυπτών του δ' αι. π.Χ. και την ελληνιστική περίοδο. Η δυναμική αναταραχή της σχολής της Περγάμου που κορυφώθηκε με τον διάσημο Λαοκόοντα γνώρισε μιαν αναγέννηση κατά την περίοδο των Αντωνίνων, όπως φαίνεται κυρίως στις τραγικές μάσκες των ετοιμοθάνατων βαρβάρων στις σαρκοφάγους μάχης του β' αι. μ.Χ. Το ΒΔ Πακιστάν φαίνεται να δείχνει μια μεταφορά αυτού του αναβιωμένου ελληνιστικού πάθους στην σχολή Gandhara και είναι προφανές ότι η υποβλητική εκφραστικότητα των προσώπων στις σκηνές του Nirvana ή της επιθέσεως της Mara πρέπει να ήταν συμβατή με μια κοινωνία που συνέλαβε τα θρησκευτικά της ιδεώδη με ανθρωπιστικούς όρους.Η κεφαλή ενός devati (πιστού) στη συλλογή του Μουσείου (Εικ. 13) είναι ένα τέλειο παράδειγμα αυτών των τεχνουργημάτων της Gandhara. Αυτή η κεφαλή είναι μια θαυμάσια απεικόνιση της φρεσκάδας της εκτελέσεως και της εντελώς ελεύθερης αποδόσεως τόσον στην ζωγραφική επεξεργασία των βοστρύχων όσον και στην ευαίσθητη απόδοση της απαλότητας των ανοιγόμενων χειλιών και του πηγουνιού. Είναι πιθανόν ορισμένα μέρη του προσώπου, όπως τα μάτια και τα φρύδια, πιο έντονα οριοθετημένα και περισσότερον ινδικά κατά το ύφος, να κατασκευάστηκαν με μήτρα. Όπως πολλά από τα κεφάλια των δευτερευόντων θεοτήτων και των συνοδών που δεν επηρεάζονται από τις συμβάσεις που διέπουν το κεφάλι του Βούδα, αυτό το ντεβάτα εκφράζει ένα είδος λαμπερής εκστάσεως που υπενθύμισε σε ορισμένους κριτικούς τον πνευματικό ρεαλισμό της γοτθικής τέχνης (Εικ. 14).35 Τεμάχια από ασβεστοκονίαμα όπως αυτό, διαχωρισμένα από το αρχικό τους πλαίσιο και χωρίς βέβαιη προέλευση, είναι εξαιρετικά δύσκολο να χρονολογηθούν. Αυτό το όμορφο κεφάλι, όπως τα καλύτερα παραδείγματα από την Hadda και Taxila, [ΕΠΟΜΕΝΗ ΣΕΛΙΔΑ 127] θα μπορούσε κάλλιστα να χρονολογηθεί ήδη από τον δεύτερο ή τον τρίτο αιώνα μ.Χ., και, όπως έχει προταθεί, είναι πιθανώς μια σύγχρονη αντανάκλαση του μπαρόκ των Αντωνίνων.Ένα δεύτερο θραύσμα από ασβεστοκονίαμα από την ίδια συλλογή (Εικ. 15), και αρχικά μέρος των λεγόμενων ευρημάτων Tash Kurgan, είναι μία μερική κόγχη που αντιπροσωπεύει τον Bodhi-sattva Maitreya και δύο συνοδούς.36 Όπως και άλλες συνθέσεις παρόμοιου σχήματος, η ομάδα όταν ήταν πλήρης ήταν πιθανώς κλεισμένη σε ένα βαρύ ημικυκλικό πλαίσιο ή αψίδα chaitya όπως εμφανίζεται σε ένα παράδειγμα στη συλλογή του μουσείου Fogg (Εικ. 16).37 Η σκηνή στην Εικ. 15 αντιπροσωπεύει τον Βουδιστή Μεσσία στον Ουρανό Tushita, την κατοικία του μέχρι την κάθοδό του για να γίνει ο Βούδας του επόμενου παγκόσμιου κύκλου.Ο Μαϊτρέγια παρουσιάζεται καθισμένος με ευρωπαϊκό τρόπο, πιθανώς σε χαμηλό θρόνο με τα πόδια του σταυρωμένα στους αστραγάλους, μια στάση που καθιερώθηκε για αυτόν στην πέτρινη γλυπτική της Gandhara38 και συνεχίστηκε ως τυπικό χαρακτηριστικό της εικονογραφίας του Μαϊτρέγια στην κινεζική γλυπτική της περιόδου των Έξι Δυναστειών.39 Εφόσον ο Μαϊτρέγια θα γεννηθεί ως Βραχμάνος, φοράει τον κορυφαίο κόμβο (κότσο) orjata-inukuta και κρατά την φιάλη νερού ή κούντικα ως χαρακτηριστικά της κάστας του. Η φορεσιά του, που περιλαμβάνει βαριά κρεμαστά κοσμήματα, βραχιόνια, βραχιόλια και μια παραλλαγή της βουδιστικής ρόμπας, είναι κατάλληλα ένας συνδυασμός των ιδιοτήτων του Βούδα και του Μποντισάτβα. Η άρθρωση των μορφών του Μαϊτρέγια και των συντρόφων του και η απαλή μοντελοποίηση των σωμάτων κάτω από τις διαφανείς ρόμπες θυμίζουν την ελληνορωμαϊκή τεχνική και ταυτόχρονα τη βαριά πληρότητα των προσώπων και την αιχμηρή, στυλιζαρισμένη επεξεργασία των φρυδιών και των ματιών φαίνεται να προσδοκά το ινδικό ιδεώδες της βουδιστικής γλυπτικής στην περίοδο Gupta.Αν τοποθετήσουμε τη λεγόμενη σχολή Gandhara μεταξύ των αρχαιότερων και πιο κλασικών γλυπτών περίπου του 100 μ.Χ. και της τελευταίας μανιεριστικής φάσεως του στυλ στην γλυπτική και ζωγραφική του έβδομου αιώνα του Bamiyan και του Fondukistan,40 η άνθιση της ως ομοιογενές στυλ περιλαμβάνει μισό χιλιετία ιστορίας της Ινδίας και της Κεντρικής Ασίας, μια εξαιρετική μακροζωία που υπερβαίνει τη διάρκεια ζωής οποιασδήποτε άλλης σχολής ή περιόδου της ανατολικής τέχνης.Για τους ελληνόφιλους η τέχνη του Γκαντάρα είναι μια εξαιρετική απεικόνιση της επιμονής και της ζωτικότητας των κλασικών μορφών σε μια ξένη γη και της καθολικής προσαρμοστικότητας αυτών των ιδανικών στα ιθαγενή ιδιώματα. Όπως έχει συχνά επισημανθεί, παρόλο που η εικονογραφία της τέχνης των Gandhara είναι άκρως ινδική, η γλώσσα εφράσεώς της είναι μια διάλεκτος της ρωμαϊκής επαρχιακής τέχνης. Δεδομένου ότι αυτό το ουμανιστικό ύφος ήταν ίσως ακατάλληλο για να εκφράσει την ουσιαστικά μυστικιστική φύση του Βουδισμού, το γεγονός παραμένει ότι τέτοιες συνεισφορές όπως η ανθρωπόμορφη αναπαράσταση του Βούδα και η γλυπτική αφήγηση της ζωής του επηρέασαν ολόκληρη τη μετέπειτα πορεία της θρησκευτικής τέχνης στην Ασία.

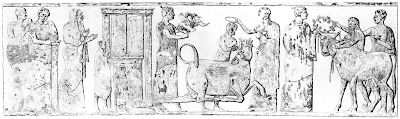

p. 125: The presentation of the human mask as a dial registering inner emotional states was an innovation of the sculptors of the fourth century B.C. and the Hellenistic period. The dynamic turbulence of the school of Pergamum climaxed by the famous Laocoon enjoyed a revival during the Antonine period, as seen primarily in the tragic masks of dying barbarians in the battle sarcophagi of the second century A.D.34 Many of the stucco heads both from Hadda and northwestern Pakistan seem to indicate a transference of this revived Hellenistic pathos to the Gandhara school, and it is evident that the [NEXT PAGE 126] evocative expressiveness of faces in the scenes of the Nirvana or the onslaught of Mara must have been congenial to a society that conceived its religious ideals in humanistic terms.The head of a devati in the Museum collection (Fig. 13) is a perfect example of these Gandhara bozzetti. This head is a wonderful illustration of the freshness of execution and completely freehand modeling both in the pictorial working of the ringlets and in the sensitive rendering of the softness of the parted lips and chin. It is possible that some parts of the face, like the eyes and brows, more sharply defined and Indian in shape, were made with a mould. Like so many of the heads of minor divinities and attendants not affected by the conventions governing the Buddha head, this devata expresses a kind of radiant ecstasy that has reminded some critics of the spiritual realism of Gothic art (Fig. 14).35 Stucco pieces like this, separated from their original context and with no certain provenience, are extremely difficult to date. This beautiful head, like the better examples from Hadda and Taxila, might [NEXT PAGE 127] very well be dated as early as the second or third century A.D., and, as has been suggested, is possibly a contemporary reflection of the Antonine baroque.A second stucco fragment in this collection (Fig. 15), and originally part of the so-called Tash Kurgan finds, is a partial lunette or niche representing the Bodhi-sattva Maitreya and two attendants.36 Like other compositions of similar shape, the group when complete was probably enclosed in a heavy semicircular enframement or chaitya arch such as appears in an example in the Fogg Museum Collection (Fig. 16).37 The scene in Fig. 15 represents the Buddhist Messiah in the Tushita Heaven, his abode until his descent to become the Buddha of the next world cycle.Maitreya is shown seated in European fashion, presumably on a low throne with his legs crossed at the ankles, a posture that became established for him in Gandhara stone sculpture38 and continued as a standard feature of the Maitreya iconography in Chinese sculpture of the Six Dynasties period.39 Since Maitreya will be born as a Brahmin, he wears the topknot orjata-inukuta and holds the water bottle or kundika as attributes of his caste. His costume, comprising heavy ear pendents, torque,16 bracelets, and a variation of the Buddhist robe, is appropriately a combination of the attributes of Buddha and Bodhisattva. The articulation of the figures of Maitreya and his companions and the soft modeling of the bodies under the diaphanous robes are reminiscent of Graeco-Roman technique, and at the same time the heavy fullness of faces and the sharp, stylized treatment of the brows and eyes seems to anticipate the Indian ideal of Buddhist sculpture in the Gupta period.If we bracket the so-called Gandhara school between the earliest and most classical carvings of about A.D. 100 and the final mannerist phase of the style in the seventh century sculpture and painting of Bamiyan and Fondukistan,40 its florescence as a homogeneous style embraces half a millennium of Indian and Central Asian history, an extraordinary longevity exceeding the life span of any other school or period of Oriental art.For Hellenophiles the art of Gandhara is an extraordinary illustration of the persistence and vitality of classical forms in an alien land and the universal adaptabilityνof these ideals to native idioms. As has often been pointed out, although the iconography of Gandhira art is perforce Indian, the language of its expression is a dialect of Roman provincial art. Granted that this humanistic style was perhaps inappropriate to express the essentially mystical nature of Buddhism, the fact remains that such contributions as the anthropomorphic representation of Buddha and the sculptural narrative of his life affected the entire later course of religious art in Asia.

Birth of Buddha. NW Pakistan, 3rd century A.D. or later., The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University (1935.24)https://harvardartmuseums.org/collect...

Birth of Buddha. NW Pakistan, 3rd century A.D. or later., The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University (1935.24)https://harvardartmuseums.org/collect... 14. Angel from the west facade of the Cathedral, Reims (detail). I3th century.https://www.ncregister.com/features/t...

14. Angel from the west facade of the Cathedral, Reims (detail). I3th century.https://www.ncregister.com/features/t...MALRAUX’s BUDDHA HEADS, Gregory P. A. Levine Ο Malraux επανεπεξεργάσθηκε την συσχέτιση του γοτθικού - Βουδιστικού ζεύγους. Για να κάνει τα γλυπτά από κονίαμα (stucco) γνωστά και συναρπαστικά, και γιά να ενισχύσει την αξία τους, προσπάθησε να εξηγήσει την μακρυνή χρονικά και γεωγραφικά διάσταση δύο γοτθικών τέχνεργων: του γοτθικού της Κεντρικής Ασίας από τον 3ο έως τον 5ο αιώνα μ.Χ. και εκείνου της Ευρώπης του 13ου αιώνα.65«Αλλά», μου λέει κάποιος, «οι ίδιες αιτίες παράγουν τα ίδια αποτελέσματα: και οι γοτθικοί, αυτός εδώ και αυτός από τη Reims, μας δείχνουν τη μεταμόρφωση μιας κλασικής τέχνης από ένα θρησκευτικό πνεύμα που κυριαρχείται από τον οίκτο. . .» Κλασική τέχνη; Στην Ασία – μια ελληνιστική τέχνη που κυριαρχείται από τη θέληση της αποπλάνησης, απόλυτα κυρίαρχος των μέσων της, στην Ευρώπη – μια ρωμαϊκή ή βυζαντινή τέχνη, αδιάφορη για την αποπλάνηση, υποταγμένη στο πορτραίτο ή στο σχήμα, ουσιαστικά κακή. . . Μεταξύ του τέλους της αυτοκρατορίας και της γοτθικής ευρωπαϊκής, υπήρχε η Ρωμαϊκή, και εδώ είναι το συναρπαστικό στοιχείο αυτών των αγαλμάτων [από το Αφγανιστάν]: βρισκόμαστε μπροστά σε έναν γοτθικό τέχνεργο χωρίς το ρωμαϊκό. Το γοτθικό της Ευρώπης, που προέκυψε από την κλασική εποχή με την ενδιάμεση επίδραση της ρωμαϊκής τέχνης, ενσαρκώνεται για τον Malraux στο πυκνό, ποικιλόμορφο γλυπτικό πρόγραμμα της Notre-Dame de Reims (μέσα του δέκατου τρίτου αιώνα). Το γοτθικό των 'Αφγανικών' stucco, εν τω μεταξύ, αναπτύχθηκε από μια εξελληνισμένη αρχή (όπως η ελληνοβουδιστική γλυπτική) χωρίς την παρέμβαση της ρωμαϊκής τέχνης. Στη συνέχεια, ο Malraux συνδέει τους δύο γοτθικούς όχι μέσω επιρροής αλλά μέσω ενός κοινού γλυπτικού «συναισθήματος»:«Στη Ρεμς και εδώ, εκφράζεται το ίδιο συναίσθημα: τρυφερότητα μπροστά στον άνθρωπο που συλλαμβάνεται ως ζωντανό πλάσμα και όχι ως πλάσμα του πόνου. Και στις δύο τέχνες, ένα εξαχνωμένο πρόσωπο: εδώ ο πρίγκιπας που θα γίνει ο Βούδας δίνει την ουσιαστική νότα, εκεί ο άγγελος, και αυτά τα δύο πρόσωπα, από τη φύση τους, ξεφεύγουν από τον πόνο.67 ------------------------------------------------------------------ p. 641: Malraux reworked the Gothic-Buddhist pairing. To make his stuccos knowable and enthralling, and enhance their value, he sought to explain (away) the temporal and geographic disjuncture of two Gothics: the Gothic of third- through fifth-century ce Central Asia and that of thirteenth-century Europe.65“But,” someone says to me, “the same causes produce the same effects: both Gothics, this one here and the one from Reims, show us the transformation of a classical art by a religious spirit that dominates pity . . .” Classical art? In Asia – a Hellenistic art dominated by the will of seduction, absolutely master of its means; in Europe – a Roman or Byzantine art, indifferent to seduction, submitted to the portrait or to the schema, essentially maladroit . . . Between the end of the empire and the Gothic European, there was the Roman, and here is the fascinating element of these statues [from Afghanistan]: we are in the face of a Gothic without the Roman. The Gothic of Europe, which arose from the classical age with the intervening impact of Roman art, is embodied for Malraux in the dense, diverse sculptural program of Notre-Dame de Reims (mid-thirteenth century). The Gothic of the Afghan stuccos, meanwhile, developed from a Hellenized beginning (like GrecoBuddhist sculpture) without the intervention of Roman art. Malraux then links the two Gothics not through influence but through shared sculptural “sentiment”:'at Reims and here, the same sentiment expresses itself: tenderness in front of the human being conceived as a living creature and not as a creature of pain. In both arts,a sublimated face: here the prince that will become the Buddha gives the essential note, there the angel, and these two faces, by their very nature, escape from pain.67'66

ΜΗΔΕΙΑ ΤΟΥ ΤΙΜΟΜΑΧΟΥ (ΕΔΩ Η ΡΩΜΑΪΚΗ ΕΚΔΟΧΗ ΤΗΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΕΠΑΥΛΙΝ ΤΩΝ ΔΙΟΣΚΟΥΡΩΝ) [image error] Medea, Museo archeologico nazionale di Napoli, (inv. nr. 8977). Da Pompei, Casa dei Dioscuri. Η Μήδεια σκέφτεται να σκοτώσει τα παιδιά της ενόσω αυτά παίζουν με τους αστραγάλους, ο δε παιδαγωγός την παρακολουθεί με θλίψη.

ΕΠΙΓΡΑΜΜΑ ΑΝΤΙΠΑΤΡΟΥ ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΟΣ Gourd 2007Μηδείης τύπος οὗτος· ἴδ', ὡς τὸ μὲν εἰς χόλον αἴρειὄμμα, τὸ δ' εἰς παίδων ἕλκυσε συμπαθίην. ... Το αρχαιότερο διαθέσιμο επίγραμμα σχετικά με την ζωγραφική του Τιμομάχου συνετέθη από τον Αντίπατρο της Μακεδονίας στα τέλη του 1ου αι. π.Χ. Δεν αναφέρεται ονομαστικά στον Τιμόμαχο, αλλά συσχετίζεται με αυτόν σύμφωνα με τους Gow & Page, οι οποίοι επισημαίνουν την αναπαράσταση αντικρουόμενων συναισθημάτων, χαρακτηριστικό κοινό σε πολλά άλλα επιγράμματα του προαναφερθέντος. Μηδείης τύπος οὗτος· ἴδ', ὡς τὸ μὲν εἰς χόλον αἴρειὄμμα, τὸ δ' εἰς παίδων ἕλκυσε συμπαθίην. Αυτό συνιστά μιά σκιαγράφηση της Μήδειας. Παρατηρήστε πώς σηκώνει το ένα μάτι από θυμό και απαλύνει το άλλο υποδηλούσα την συμπάθεια για τα παιδιά της. (API 143 - Πλανούδειος Ανθολογία)Όπως η ματιά της Μήδειας, έτσι και το ποίημα εν γένει κινείται σε δύο αντιφατικές τροχιές{PREGNANT MOMENT / ΣΗΜΕΙΟ ΚΑΜΠΗΣ ή ΕΓΚΥΜΟΝΟΥΣΑ ΣΤΙΓΜΗ / Gotthold Ephraim Lessing}: η μία συνιστά μιά κίνηση νοηματοδοτήσεως - αποδόσεως / καταλογισμού μακριά από τον πίνακα, η άλλη προς αυτόν και προς την παρουσία. Κατά την πρώτη τροχιά - μακριά από αυτόν - αποδίδει ευφάνταστα συναισθήματα στην ζωγραφική σκηνή: «παρατηρήστε», λέει ο Αντίπατρος, «πώς σηκώνει το ένα μάτι υπονοούσα τον θυμό και απαλύνει το άλλο κάνοντας σαφή την συμπάθειά της για τα παιδιά της». Τίποτα από αυτά δεν μπορεί να ειπωθεί ότι σαφώς υπάρχει στην εικόνα. H αντιπροσώπευση / μεταφορά που υπονοείται από την υιοθέτηση των συγκεκριμένων ρημάτων από τον Αντίπατρο είναι ξένη προς αυτό. Κανείς δεν μπορεί να ζωγραφίσει τον θυμό ούτε να δείξει την συμπάθεια. Αυτά τα συναισθήματα «εμφανίζονται» μόνον μετά από μια ψυχική μεταμόρφωση, εν προκειμένω με την ανάμνηση της στιγμής προς το τέλος της Μήδειας του Ευριπίδου, όταν οι εκδικητικές προθέσεις της ηρωίδας διακόπτονται από το βλέμμα εμπιστοσύνης των παιδιών της. Δεν είναι ασυνήθιστο στον αρχαίο κόσμο τα μάτια να θεωρούνται ως ο 'τόπος' του χαρακτήρα στις καλλιτεχνικές αναπαραστάσεις. Αυτό δεν σημαίνει, ωστόσο, ότι τα μάτια είναι ο τόπος του χαρακτήρα' σημαίνει, μάλλον, ότι παρέχουν έναν χώρο όπου τα αρχαία ερμηνευτικά συστήματα επέτρεπαν την ανάγνωση του χαρακτήρα. Αλλά η ανάγνωση του χαρακτήρα, για την αρχαία θέαση, σήμαινε συχνά την κατασκευή ή τον στοχασμό ενός ευρύτερου αφηγηματικού πλαισίου. Στον Αριστοτέλη, για παράδειγμα, το ἦθος είναι άρρηκτα συνδεδεμένο με την δράση και επομένως άρρηκτα εξαρτημένο από την αφήγηση. Όπως το θέτει ο Stephen Halliwell, "η βάση του χαρακτήρα στον Αριστοτέλη συνίσταται από ανεπτυγμένες διαθέσεις για ενάρετη ή άλλη δράση. Αυτές οι προθέσεις αποκτώνται και πραγματοποιούνται στην πράξη· δεν μπορούν να δημιουργηθούν ή να συνεχίσουν να υπάρχουν για πολύ, ανεξάρτητα από την πρακτική δραστηριότητα. " ------------------------------------------------------- -------------- The earliest datable epigram on Timomachus's painting was composed by Antipater of Macedonia at the end of the 1E century BCE. It does not refer to Timomachus by name but is linked to him by Gow and Page, who point to the representation of conflicting emotions and to the use of Tinto, both of which it shares with several other Timornachus epigrarns. Μηδείης τύπος οὗτος· ἴδ', ὡς τὸ μὲν εἰς χόλον αἴρειὄμμα, τὸ δ' εἰς παίδων ἕλκυσε συμπαθίην. This is the sketch of Medea. Observe how she raises one eye to anger, and softens the other towards sympathy for her children. (API 143)Like Medea's glance, the poem moves along two conflicting trajectories: one a movement of meaning-attribution away from the painting, the other towards it and towards presence. Away from it, it imaginatively imputes emotions to the painted scene: "observe," Antipater says, "how she raises one eye to anger and softens the other towards sympathy for her children." None of this can be properly said to be in the image. The agency implied by Antipater's use of finite verbs is foreign to it. Nor can one paint anger or sympathy; these emotions "appear" only after a mental transfiguration, in this case by recalling the moment toward the end of Euripides' Medea when the heroine's vengeful intentions are inter-rupted by the trusting gaze of her children. It is not uncommon in the ancient world for eyes to be seen as the locus of character in artistic representations. This does not mean, however, that eyes are the locus of character; it means, rather, that they furnish one site where ancient interpretive regimes allowed character to be read. But reading character, for ancient regimes, often meant constructing or contemplating a broader narrative context. In Aristotle, for example, ἦθος is inextricably linked to action and thus implicitly dependent on narration. As Stephen Halliwell puts it, "the basis of character in Aristotle is constituted by developed dispositions to act virtuously or otherwise. These dispositions are both acquired and realized in action; they cannot come into existence or continue to exist for long independently of practical activity" SOURCE: Gurd 2007

Valladares 2020

The Tender Interior, Summary - https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/...

Αυτό το κεφάλαιο συνεχίζει την μελέτη του θέματος της προφορικής διαδόσεως διερευνώντας δύο τοιχογραφίες της Μήδειας από την Πομπηία – μια από τον Οίκο του Ιάσονα και η άλλη από τον Οίκο των Διοσκούρων – που την δείχνουν να στοχάζεται την δολοφονία των παιδιών της. Με βάση το προηγούμενο κεφάλαιο, το επιχείρημα στρέφεται τώρα στην κυριολεκτική και μεταφορική εξημέρωση αυτού του απόλυτου τερατουργήματος. Αναλύοντας αυτούς τους πίνακες σε συνδυασμό με την 12η επιστολή από τις Ηρωίδες του Οβιδίου (επιστολή της Μήδειας προς τον Ιάσονα), βλέπουμε πώς αυτές οι εικόνες της Μήδειας σε ένα οικιακό σκηνικό προσκαλούν τους θεατές να (ξανα) δημιουργήσουν τον εσωτερικό αγώνα της ηρωίδας – μια διαδικασία που θα την έκανε να καταστεί συμπαθής στα μάτια των αρχαίων θεατών συντονισμένα με την μορφή ενός εγκαταλειμμένου ελεγειακού εραστού. Ενώ οι εραστές που συζητήθηκαν στα προηγούμενα κεφάλαια δείχνουν κυρίως την τρυφερότητα μέσω της συντροφικότητας, η Μήδεια στην απομόνωσή της γίνεται συμπονετική λόγω της εμφανούς απουσίας του Ιάσονος, που την οδηγεί στην φρικτή πράξη της. Αυτή η απουσία, φυσικά, είναι επίσης η απαραίτητη έπαρση των επιστολικών ελεγειακών μυθοπλασιών του Οβιδίου. Μακριά από την αγέρωχη, εκδικητική θεά της ευριπίδειας τραγωδίας, η Μήδεια στην ποίηση και την ζωγραφική της Ρώμης του πρώτου αιώνα εμφανίζει τρυφερά χαρακτηριστικά που συντονίζονται με τις πρώιμες αυτοκρατορικές έννοιες του γάμου και της οικογενειακής ζωής.

This chapter continues the theme of dissemination by investigating two Pompeian wall paintings of Medea – one from the House of Jason and the other from the House of the Dioscuri – that show her contemplating the murder of her children. Building on the previous chapter, the argument now turns to the literal and figurative domestication of this ultimate monstrosity. By analyzing these paintings in conjunction with Ovid’s Heroides 12 (Medea’s epistle to Jason), we see how these images of Medea in a domestic setting invite viewers to (re)create the heroine’s own inner struggle – a process that would have rendered her sympathetic in the eyes of ancient spectators attuned to the figure of an abandoned elegiac lover. Whereas the lovers discussed in the previous chapters primarily evince tenderness through togetherness, Medea in her isolation becomes sympathetic through Jason’s conspicuous absence, which drives her to her horrific deed. That absence, of course, is also the necessary conceit of Ovid’s epistolary elegiac fictions. Far from the haughty, vengeful goddess of Euripidean tragedy, Medea in the poetry and painting of first-century Rome displays tender characteristics that resonate with early Imperial notions of marriage and domesticity.

Η Agnes Rouveret υποστηρίζει ότι η αναπαράσταση χαρακτήρων στην ζωγραφική συνδέθηκε ιστορικά με απεικονίσεις πολλαπλών ανθρώπινων μορφών του πέμπτου αιώνα σε μια οιονεί αφηγηματική αλληλεπίδραση. Αν ναι, τότε το Ελληνιστικό ύφος της παραλείψεως του αφηγηματικού πλαισίου και της απαιτήσεως από τον θεατή να φανταστεί τα υπόλοιπα συνδέεται εσωτερικά (αιτιωδώς), και όχι απλώς τυχαία, με την συχνά παρατηρούμενη αύξηση της εκφραστικότητας στην ζωγραφική και την γλυπτική από τον τέταρτο αιώνα και αργότερα. Η ευφάνταστη συμπλήρωση ενός πίνακα από τον οποίο έχει αφαιρεθεί το αφηγηματικό πλαίσιο σημαίνει να φαντάζεσαι το ἦθος του αναπαριστώμενου χαρακτήρα με την μία. Με βάση αυτές τις παρατηρήσεις, γίνεται δυνατή μια λεπτομερής ανασύνθεση της εξαιρετικά περίπλοκης πράξεως του «οράν» που αφηγείται το επίγραμμα του Αντίπατρου. Ο θεατής αναπολεί την σκηνή της τραγωδίας του Ευριπίδου όπου η Μήδεια συζητά δυνατά την επίλυσή της, και αυτό το απόσπασμα του/της επιτρέπει την πρόσβαση σε δύο πιθανά αφηγηματικά αποτελέσματα: αυτό που γνωρίζει ότι θα πραγματοποιηθεί στο τέλος της τραγωδίας και το αντίθετο ενδεχόμενο που εκφράζεται στους στίχους 1040-1046 της Μήδειας, ότι δηλαδή η τελευταία θα λυπόταν τα παιδιά της και θα τα έπαιρνε τελικά μαζί της από την Κόρινθο. Φανταζόμενος δύο αφηγηματικά τελικά σημεία (καταλήξεις ή ενδεχόμενα), ο θεατής διαβάζει στην συνέχεια δύο αντικρουόμενες ηθικές διαθέσεις στον πίνακα. Το όραμα που «βλέπει» την διχασμένη ψυχή της Μήδειας στις γραμμές και τα χρώματα της ζωγραφικής του Τιμομάχου περιγράφεται επομένως καλύτερα ως μια μορφή αφηγηματικής μνήμης που επικαλύπτει μια ανακαλούμενη ιστορία πάνω στο ορατό, ενώ το ποίημα που εκφέρει αυτό το όραμα επιτυγχάνει μια παράσταση πολιτισμικής ικανότητας δίνοντας έμφαση στην γνώση της ελληνικής λογοτεχνίας και στην κομψή λεκτική έκφραση. Με τον τρόπο αυτό, ο Αντίπατρος αμφισβητεί την αμεσότητα του οπτικούμέσου και επιβεβαιώνει την δύναμη της γλώσσας που αποδίδει νόημα. Αλλά οι τρεις πρώτες λέξεις εξισορροπούν αυτήν την κίνηση μακριά από το ζωγραφισμένο αντικείμενο με μια αντίστροφη κίνηση προς αυτό: Μηδείης τύπος οὗτος. Η πράξη της δείξεως —αυτός είναι ο 'τύπος' της Μήδειας, αυτός ο πίνακας εδώ και κανένας άλλος— ορίζει έναν συγκεκριμένο χώρο για την απόδοση του ποιήματος, γειώνοντάς το σε χρόνο και τόπο και επιμένοντας στην υλική παρουσία του αντικειμένου. (Ο Gumbrecht υποστηρίζει ότι η φαινομενικά απλή πράξη της καταδείξεως των αντικειμένων αισθητικής τους επιτρέπει να 'συντονίζονται' με τρόπους που οι ισχυρότερες ερμηνευτικές πράξεις δεν επιτυγχάνουν). Ωστόσο, το ποίημα δεν δίδει απλώς έμφαση στην παρουσία του έργου τέχνης δείχνοντας. Επιπλέον, η επιλογή των κατάλληλων λέξεων από τον Αντίπατρο είναι και ακριβής.. Από τις διάφορες λέξεις που είναι διαθέσιμες για να περιγράψει έναν πίνακα (για παράδειγμα 'εἰκών' ή 'ἄγαλμα') ο Αντίπατρος επέλεξε μια λέξη που θα μπορούσε επίσης να χρησιμοποιηθεί για να περιγράψει τόσον το αρχικό περίγραμμα ενός πίνακα όσον και ένα ημιτελές σχέδιο. Αν και ο 'τύπος' είναι μια συνηθισμένη λέξη για ζωγραφισμένες εικόνες, και εμφανίζεται συχνά σε εκφραστικά επιγράμματα, χρησιμοποιείται επίσης συνήθως για να περιγράψει ένα κείμενο ή μια εικόνα που είναι μόνο «δεσμευμένη ή κρυμμένη ή ανολοκλήρωτη» (για να χρησιμοποιήσω μια σύγχρονη μεταφορά) και εξακολουθεί να περιμένει την περαιτέρω επεξεργασία ώστε να καταστεί ακριβής (΄ἀκρί̄βεια') που θα έρθει με την αναθεώρηση (βλέπε παραπάνω σημ. 13 και 14). Αυτό απετέλεσε μια επιτυχή απόκρυψη, αφού η Μήδεια ήταν στην πραγματικότητα ημιτελής, και υπογραμμίζει το κατ' εξοχήν στοιχείο που υποτίθεται ότι η επίκληση του ψυχολογικού βάθους του επιγράμματος υπερβαίνει περισσότερο· αυτό το θραύσμα της ουσίας που είναι το ίδιο το αντικείμενο. Στην φράση «αυτό είναι το σκίτσο της Μήδειας» ο Αντίπατρος αφηγείται μια στιγμή όπου ο θεατής, όπως η Μήδεια ενώπιον των απογόνων της, διακόπτεται, αποσπάται απότομα, από μια βαριά υλική παρουσία...

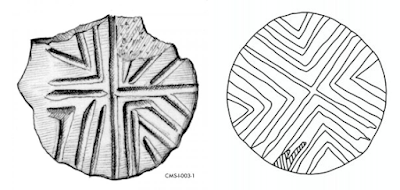

ICON, Crowley, J. L. 2024(σελ. 69-70): Προσπάθειες για την καλλιτεχνική απόδοση συναισθήματος από ανθρώπους και ζώα παρατηρούνται επίσης στη Μινωική Υψηλή Τέχνη. Η προσπάθεια καταγραφής φωνής είναι από τις πιο ενδιαφέρουσες, ιδιαίτερα με ζώα. Υπάρχουν πολλά θηλαστικά όπου το ανοιχτό στόμα μπορεί κάλλιστα να εκπέμπει φυσήματα, μουγκρητά, βρυχηθμούς ή άλλους ήχους κατάλληλους για την κατάσταση του ζώου. Το νεαρό τραυματισμένο ζώο στο 3,59 σηκώνει το κεφάλι του και ανοίγει το στόμα του για να φωνάξει από τον πόνο, καθώς κάνει ο πληγωμένος ταύρος στο 3.33. Αυτή είναι μια κανονική λεπτομέρεια για την απόδοση της θλίψεως - ταλαιπωρίας ζώων, που μερικές φορές αποτελεί μέρος της απεικόνισης του θηράματος σε σκηνές επίθεσης με ζώα όπως στα 3.40, 3.42, 2.28 και 2.58. Το ανοιχτό στόμα μπορεί να εκπέμπει πιο απαλό ήχο καθώς το μητρικό ζώο φιμώνει απαλά τα μικρά της σε 3,26, 1,91 και 2,27.Τότε ποιος θα μπορούσε να ξεχάσει το κλάμα του αρσενικού αγριμιού που ζευγαρώνει στο 2,26! Η σχέση με τον άνθρωπο μπορεί επίσης να κάνει το ζώο να χρησιμοποιήσει τη φωνή του, κάπως απαλά προς τον άνδρα στο 3,60, αλλά σε μεγάλη αγωνία καθώς οι βοσκοί παίρνουν τα μικρά τους σε 3,62. Το συναίσθημα, με ή χωρίς φωνή, ενσωματώνεται στη δημιουργία του ζώου που θηλάζει και φροντίζει τα νεαρά εικονίδια που στοχεύουν ρητά σε δεσμούς καλλιέργειας όπως στα 3.61, 3.26, 3.27, 1.91 και 2.27. Με τους ανθρώπους η ΑΠΕΙΚΟΝΙΣΗ ΣΥΝΑΙΣΘΗΜΑΤΩΝ είναι πολύ πιο προσεκτική. Δύο ανθρώπινα ανδρικά κεφάλια, 3,58 και 3,70, έχουν ανοιχτά στόματα που μπορεί να υποδηλώνουν ομιλία ή τραγούδι. Τα άλλα κεφάλια έχουν κλειστά στόματα και κανένα δεν παρουσιάζει συναισθηματικές καταστάσεις. Δεν εμφανίζονται γυναικεία κεφάλια. Με τις ανθρώπινες μορφές πλήρους μεγέθους τα κεφάλια είναι απαραίτητα πολύ μικρά και παρόλο που ορισμένα χαρακτηριστικά έχουν σχήμα, το μικροσκοπικό τους μέγεθος εμποδίζει το αποκαλυπτικό τους συναίσθημα. Έτσι, μας μένει η στάση των μορφών. Ήδη στη συζήτηση για τους πεσόντες πολεμιστές και κυνηγούς έχουμε σχολιάσει την αγωνία των χτυπημένων σωμάτων τους όπως στο 2,31 έως 2,34 και 2,36, αλλά για πιο χαρούμενα συναισθήματα οι στάσεις σώματος είναι σύνθετες και επίσημες, βρίσκουν κυρίως έκφραση σε χειρονομίες. Μια σειρά από 15 χειρονομίες κωδικοποιούν τις ανθρώπινες αλληλεπιδράσεις και το συναίσθημα που σχετίζεται με την καθεμία. Οι χειρονομίες ονομάζονται περιγραφικά για το μέρος του σώματος που αγγίζεται ή τη θέση των χεριών ή των χεριών ή για το τι κρατιέται στα χέρια, όπως στο μέτωπο, τον ώμο, την καρδιά, το στήθος, τους γοφούς, τον χαιρετισμό, το άγγιγμα, το νεύμα, το κατάδειξη, τα χέρια ψηλά, χέρια ψηλά, πιασμένοι χέρι χέρι, δύναμη, κραδαίνοντας και .. 20. Μια πλήρης συζήτηση αυτών των χειρονομιών ακολουθεί στο Κεφάλαιο 9, αλλά θα πρέπει να σημειώσουμε εδώ τις χειρονομίες που δείχνουν ιδιαίτερα συναισθήματα από την πλευρά του χειρονομούμενου: χαιρετισμός, μέτωπο, ώμος, καρδιά και κράτημα από τα χέρια. Στο 3,63 η γυναίκα υποδέχεται τη μορφή των Θεοφανείων με μια χειρονομία χαιρετισμού, αν και δεν είναι σαφές αν οι άνδρες και οι γυναίκες χαιρετούν ή αποχαιρετούν ο ένας τον άλλον στο 2,60. Η χειρονομία του μετώπου δίνεται από τη γυναίκα στο 2,63 και τον άνδρα στο 2,72 παρουσία των μορφών των Θεοφανείων που εμφανίζονται μπροστά τους.Αυτή η χειρονομία είναι μια αναγνώριση της μεγαλοπρέπειας αυτών των μορφών των Θεοφανείων, και έτσι έχει ονομαστεί συχνά χειρονομία προσευχής. Η χειρονομία του ώμου φαίνεται να σημαίνει συμμετοχή ή ακρόαση, όπως με τη γυναίκα στο 3,66 όπου αυτή παρακολουθεί τους άλλους στην ομάδα. Αυτή είναι επίσης η χειρονομία όταν η γυναίκα περιμένει/ακούει μπροστά σε ένα ιερό όπως στο 9.69. Η χειρονομία της καρδιάς υποδηλώνει μια σχέση μεταξύ του άνδρα και της γυναίκας όπως στο 3.66.Μια ακόμη πιο ισχυρή σύνδεση υποδηλώνεται από την χειρονομία κρατήματος των χεριών που κάνουν η γυναίκα και ο άνδρας στο 3,45 και 3,56. Στις σύνθετες σκηνές σε χρυσά σφραγιστικά δαχτυλίδια, η χρήση συνδυασμού και κατ' όψιν στάσεων και οι χειρονομίες χρησιμοποιούνται μαζί για να ζωντανεύουν τις μορφές και τις επικοινωνίες μεταξύ τους. Εξετάστε τις ομάδες στα 3,55, 3,56, 3,63, 3,66 και 3,73 όπου οι χειρονομίες συνδέουν τα άτομα και η συζήτηση μπορεί σχεδόν να ακουστεί. Ίσως δεν προκαλεί έκπληξη το γεγονός ότι σε μια παραδοσιακή κοινωνία η επίδειξη συναισθήματος περιορίζεται σε αποδεκτές χειρονομίες.

BERGAMOΛαμβάνοντας υπόψη την ανθρώπινη εκφραστική ανάγκη να αναπαραστήσει το πάθος «από την ανήμπορη μελαγχολία ως τον δολοφονικό κανιβαλισμό», ο Aby Warburg όρισε την ερμηνευτική διάταξη του Pathosformeln ως «χειρονομίες στον υπερθετικό βαθμό» που εμφανίζονται σταθερές στα τεχνουργήματα μέσω εικονιστικών τύπων από την αρχαιότητα, και ως αποτυπώματα («engrams») που μπορούν να «επανενεργοποιηθούν» από καλλιτέχνες σε διάφορες περιόδους. Βρίσκουμε μια συστηματική εξέταση αυτών των εικονογραφικών τύπων στο τελευταίο, ημιτελές έργο του Warburg, το Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (1929). Ο Άτλας είναι, στην πραγματικότητα, μια συλλογή εκφράσεων του ανθρώπινου δυναμισμού, που περικλείεται μέσα σε έναλαβύρινθο εικόνων που εξαπλώνεται από την αρχαιότητα μέχρι τη σύγχρονη εποχή. Αυτή η εργασία στοχεύει να προσφέρει μια ανάγνωση των διαφορετικών μορφών εικονογραφίας του πόνου που μπορούν να βρεθούν στον Άτλαντα: από τις «αρχαίες προκατασκευασμένες εκφράσεις» του πόνου στούς πίνακες 5 και 6, στην «επανεμφάνιση του διονυσιακού πάθους της καταστροφής» στούς πίνακες 41 και 41α - ιδίως μέσω της εικόνας του Λαοκόοντος. Τέλος, στον πίνακα 42 ακολουθούμε την «ενεργειακή και σημασιολογική αντιστροφή του πάθους του πόνου»: η φρενήρης απόγνωση της Μαρίας Μαγδαληνής ως «Μαινάδας κάτω από τον Σταυρό», και το θέμα της μελαγχολίας και του διαλογισμού, που από το «Θέατρο του θανάτου» συνεχίζει προς την μορφή της διανοητικής ιδιοφυΐας, του «γιου του Κρόνου», στούς πίνακες 53, 56 και 58.ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑhttps://www.ashmolean.org/amarna-revo... AMARNA 'REVOLUTION' GALLERY, Ashmolean

https://brill.com/view/journals/ow/2/... Stylistic traces of Amarna Art in Reliefs of the Tomb of Petosiris (Tuna Al Gebel Necropolis),Kuvatova, B. 2021. “Stylistic Traces of Amarna Art in Reliefs of the Tomb of Petosiris (Tuna al Gebel Necropolis),” Old World: Journal of Ancient Africa and Eurasia 2021, pp. 1-27. <https://brill.com/view/journals/ow/2/... .. scenes of tender physical contact between children and adults are probably the most intriguing .. GESTURES OF AFFECTION!

https://www.academia.edu/33343030/Dav.... A., 2017. "A Throne for Two: Image of the Divine Couple During Akhenaten’s Reign," JAEI 14, pp. 1-10.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3822115J..., W. R. 1996. "Amenhotep III and Amarna: Some New Considerations," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 82, pp. 65-82.

https://escholarship.org/content/qt1t..., A. 2020. "Emotions," in UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, ed. A. Austin and W. Wendrich, Los Angeles.

https://books.google.gr/books?id=B0zS..., G. P. A. 2011. "Malraux’s Buddha Heads," in A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, ed. R. M. Brown, D. S. Hutton, pp. 629-654.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4171434R..., B. 1965. "A Cycle of Gandhāra," Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 63 (333), pp. 114-129.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4543317h..., S. A. 2007. "Meaning and Material Presence: Four Epigrams on Timomachus's Unfinished Medea,", Transactions of the American Philological Association 137 (2), pp. 305-331.

https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2021/2021.0..., H. 2020. Painting, Poetry, and the Invention of Tenderness in the Early Roman Empire, Cambridge Univ. Press.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/..., H. 2020. "The Tender Interior," in Painting, Poetry, and the Invention of Tenderness in the Early Roman Empire, pp. 140-185.

https://monoskop.org/images/f/f1/Winc..., J. J. 1972. Writings on Art, ed. D. Irwin, Bristol.

https://books.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/pr..., J. L. 2024. ICON. Art and Meaning in Aegean Seal Images, Propylaeum.

https://www.academia.edu/41252255/Ico..., M., G. Bordignon. 2019. "Iconographies and Pathosformeln of Pain in Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas: A Pathway through Plates 5, 6, 41, 41a, 42, 53, 56 and 58," IKON 12 (Journal of Iconographic Studies), pp. 219-232.

https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/archive/bil... Institute Archive, Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, Bilderatlas Mnemosyne | Final version

ΕΠΑΝΕΜΦΑΝΙΣΗ ΤΟΥ ΔΙΟΝΥΣΙΑΚΟΥ ΠΑΘΟΥΣ ΤΗΣ ΚΑΤΑΣΤΡΟΦΗΣ

May 23, 2024

JULIA DOMNA CHOSE TO BE REPRESENTED AS A HELLENISTIC QUEEN

p. 7Dio reported that Julia Domna received senatorial delegations, answered imperial correspondence in Greek and Latin, and singlehandedly ran the civic half of the empire in Antioch while Caracalla frittered away precious resources in a pointless campaign against the Parthians.20 {Cass. Dio 79.4. Other scholars have seen this passage as a sort of encomium for the empress (e.g., Taylor 1945), but I suspect that Dio meant to indict Caracalla’s shirking of his civil duties by leaving them to a woman.} ...................p. 21/251Geta’s death at the end of 211 precipitated a new ideological crisis for the imperial administration and called for Caracalla’s administration to produce a new set of messages that would promote the new sole reign. Caracalla’s program of propaganda was radically different than his father’s, and as such Julia Domna played a small role. In fact, the power which Julia held in this period—perhaps the greatest power she or any imperial woman had held thus far—was semiofficial: she met with important men, reviewed correspondence in Greek and Latin, and forwarded only the most pressing issues to Caracalla, who campaigned while she stayed in Antioch.89 ..................... p. 87While Caracalla was campaigning (or gallivanting, as Dio would characterize it) in the East, Julia Domna was left in Antioch to assume the duties of the civil half of the empire. She conscientiously answered the emperor’s correspondence in Latin and Greek and met with senatorial and provincial delegations.

SUMMARY How the maternal image of the empress Julia Domna helped the Roman empire rule. Ancient authors emphasize dramatic moments in the life of Julia Domna, wife of Roman emperor Septimius Severus (193–211). They accuse her of ambition unforgivable in a woman, of instigating civil war to place her sons on the throne, and of resorting to incest to maintain her hold on power. In imperial propaganda, however, Julia Domna was honored with unprecedented titles that celebrated her maternity, whether it was in the role of mother to her two sons (both future emperors) or as the metaphorical mother to the empire. Imperial propaganda even equated her to the great mother goddess, Cybele, endowing her with a public prominence well beyond that of earlier imperial women. Her visage could be found gracing everything from state-commissioned art to privately owned ivory dolls. In Maternal Megalomania, Julie Langford unmasks the maternal titles and honors of Julia Domna as a campaign on the part of the administration to garner support for Severus and his sons. Langford looks to numismatic, literary, and archaeological evidence to reconstruct the propaganda surrounding the empress. She explores how her image was tailored toward different populations, including the military, the Senate, and the people of Rome, and how these populations responded to propaganda about the empress. She employs Julia Domna as a case study to explore the creation of ideology between the emperor and its subjects.

Julia Domna (The Harvard Art Museum 1956.19)

Julia Domna (The Harvard Art Museum 1956.19)p. 81/82Perhaps the most interesting and certainly the most unique piece of evidence concerning the reception of Julia Domna by the populations of Rome comes in the form of an articulated ivory doll found in the tomb of the Vestal Virgin Cossinia (see figure 16). The “ancient Barbie,” as she was dubbed in the Italian press, has the hairstyle and features that look much like Julia Domna’s, particularly from the period of Severus’s reign.123 The clothing on the doll, if there was any, has long since decayed, but gold jewelry seems to say something of both the owner and the model for the doll. The owner was likely from a wealthy family and, being a Vestal Virgin, she certainly knew the most powerful and prestigious people in the empire, though this may not have been true when she first acquired the doll. The depiction of the empress is certainly not the maternal figure that the imperial administration so vigorously promoted in Rome. As other commentators have noted, it does not invite or teach its owner to cuddle or nurture it. Instead, the bracelets and sophisticated coiffure bespeak an elegant lifestyle in which beauty and poise are the most valued qualities.124 The doll offers little evidence that she has or will bear, suckle, or nurture children, as we see on the bronze coinage of Julia Domna that was distributed in Rome (see figure 3). This doll — if it was meant to be a representation of Julia Domna —bears no trace of the empress to whom the administration ascribed universal motherhood. Instead, it allows us to see Julia Domna through contemporary female eyes. The girl (and eventually woman) who owned this doll was a Vestal Virgin, someone who rubbed shoulders with powerful men and women. She might well be the elusive woman whose response to imperial portraiture Wood once wondered about.125

Figure 16. Ivory articulated doll found in the Tomb of the Vestal Virgin Cossinia. Photograph courtesy of the VRoma Project (www.vroma.org) with permission from the Ministero per i Beni e la Attività Culturali–Sporintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici

Figure 16. Ivory articulated doll found in the Tomb of the Vestal Virgin Cossinia. Photograph courtesy of the VRoma Project (www.vroma.org) with permission from the Ministero per i Beni e la Attività Culturali–Sporintendenza Speciale per i Beni ArcheologiciΤα Νευρόσπαστα και οι θεατρικές παραστάσεις ήταν της "μόδας" μεταξύ των Ελλήνων όπως τουλάχιστον αναφέρεται από τους Έλληνες και Ρωμαίους συγγραφείς. Για πολλούς το θέατρο νευροσπάστων ήταν το σύμβολο της ανθρώπινης μοίρας. Επιφανείς κλασικοί συγγραφείς, φιλόσοφοι, θεολόγοι και επιστήμονες, όπως ο Πλάτων, ο Μάρκος Αυρήλιος, ο Κλήμης ο Αλεξανδρεύς, ο Ευσέβιος, ο Επίκτητος, ο Φίλων και άλλοι κάνουν συχνές περιγραφές για τις μαριονέτες και τον τρόπο που κινούνταν χρησιμοποιώντας τη λέξη ΄"νευρόσπαστον" συνώνυμη της λατινικής λέξης marionette.

Ο Πλάτων στο βιβλίο του «Οι Νόμοι» κάνει αναφορά στις μαριονέτες λέγοντας: «Ας υποθέσουμε ότι ο καθένας από εμάς είναι ένα "νευρόσπαστο" (κινούμενη φιγούρα) που βρίσκεται στα χέρια των Θεών για τη δική τους διασκέδαση ή επειδή είχαν ένα σοβαρό σκοπό για μας για τον οποίο δε γνωρίζουμε τίποτα. Οι παρορμήσεις που μας κινούν μοιάζουν με κλωστές που τις τραβούν οι θεοί από διάφορες κατευθύνσεις …»

Ο Αριστοτέλης στο σύγγραμμα «Τα Πολιτικά» αναφέρεται στα αγάλματα του Δαίδαλου που είχαν τη μοναδική ιδιότητα στην αγαλματοποιία να έχουν την ικανότητα να κινούνται από μόνα τους.

Ο Οράτιος, ο σατυρικός Πέρσιος Φλάκος, και ο Ρωμαίος αυτοκράτορας Μάρκος Αυρήλιος αμφιβάλουν για την ελεύθερη βούληση του ανθρώπου συγκρίνοντας τον με νευρόσπαστο.

Οι Ελληνικές μαριονέτες κατασκευάζονταν από τερακότα (ψημένο χώμα - πηλός), κερί, ελεφαντόδοντο ή ξύλο. Οι εξαιρετικές κατασκευές ήταν από ασήμι. https://www.marionette.gr/history.php --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Σε ένα πρόσφατο έργο αφιερωμένο σε μια εξαιρετική ομάδα διακοσμημένων νευρόσπαστων από τερακότα από τη συλλογή Sambon (Μιλάνο), που χρονολογείται από την ελληνιστική και την ρωμαϊκή περίοδο, σημείωσα ότι ακόμη και για τη λειτουργία και το νόημα των μαριονετών δεν είναι δυνατόν να αγνοηθεί εντελώς η σύνδεση, τουλάχιστον αρχική, με θρησκευτικές τελετές και αποτροπαϊκά αποτελέσματα. Είναι οι ίδιες οι πηγές (Ηρόδοτος, 2.48 in primis) που υποδηλώνουν ότι τα νευρόσπαστα, δηλαδή μορφές με κινητά μέλη που μπορούν να γίνουν αντικείμενα χειρισμού με χορδές, πριν γίνουν ο πλούτος των κουκλοπαικτών και η χαρά των παιδιών, ήταν υποκατάστατα ή αγάλματα των θεοτήτων στις ιερές τελετές [13]. Η διφορούμενη αξία ορισμένων ακροβατικών και ισορροπιστικών κινήσεων, που παλινδρομεί μεταξύ της απλής έννοιας του παιχνιδιού / σχόλης και μιας βαθύτερης (αλλά μερικές φορές δυσνόητης) τελετουργικής και αποτροπαϊκής φύσεως, είναι επιπλέον το ίδιο που η πρόσφατη βιβλιογραφία έχει επαναστέλλεται μεταξύ μιας απλής έννοιας του ludus και μιας βαθύτερης (αλλά μερικές φορές δυσνόητης) τελετουργικής αξίας και αποτροπαϊκό, είναι επιπλέον το ίδιο που η πρόσφατη βιβλιογραφία έχει επίσης αναγνωρίσει για τις κούκλες από τερακότα με κινητά άκρα [14].-

TO ΒΛΕΜΜΑ ΚΑΤΑΜΑΤΑ, H JULIA DOMNA, ΟΙ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΕΣ - ΑΙΓΥΠΤΙΑΚΕΣ ΝΕΚΡΙΚΕΣ ΠΡΟΣΩΠΟΓΡΑΦΙΕΣ & ΟΙ ΧΡΙΣΤΑΝΙΚΕΣ ΕΙΚΟΝΕΣ ..

ΑΠΟ ΤΙΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΝΕΚΡΙΚΕΣ ΠΡΟΣΩΠΟΓΡΑΦΙΕΣ ΤΗΣ ΑΡΣΙΝΟΪΤΙΔΟΣ ΣΤΙΣ ΧΡΙΣΤΙΑΝΙΚΕΣ ΕΙΚΟΝΕΣ .. ΣΕΠΤΙΜΙΟΣ ΣΕΒΗΡΟΣ & ΟΙΚΟΓΕΝΕΙΑ

ΑΠΟ ΤΙΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΤΙΚΕΣ ΝΕΚΡΙΚΕΣ ΠΡΟΣΩΠΟΓΡΑΦΙΕΣ ΤΗΣ ΑΡΣΙΝΟΪΤΙΔΟΣ ΣΤΙΣ ΧΡΙΣΤΙΑΝΙΚΕΣ ΕΙΚΟΝΕΣ .. ΣΕΠΤΙΜΙΟΣ ΣΕΒΗΡΟΣ & ΟΙΚΟΓΕΝΕΙΑΑυτός είναι ο μόνος διατηρημένος αρχαίος πίνακας της αυτοκρατορικής οικογένειας του Ρωμαίου Αυτοκράτορα Σεπτίμιου Σεβήρου. Εδώ, μπορούμε να δούμε την σύζυγό του Ιουλία Δόμνα (Julia Domna) και τους γιους του, Caracalla και Geta, με τα βασιλικά διάσημα. Μετά την δολοφονία του Γέτα για λογαριασμό του Καρακάλλα, η μνήμη του εξαλείφθηκε και το πρόσωπο του πρίγκιπα ξύστηκε (damnatio memoriae). Τέμπερα σε ξύλο. Αποκτήθηκε από την Αίγυπτο το 1932 μ.Χ. Ρωμαϊκή Αίγυπτος, 200 μ.Χ. Εκτίθεται στο Μουσείο Altes στο Βερολίνο, Γερμανία.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Mathews, T. F. 2021. "The Origin of Icons

-----------------------------------------------------------------

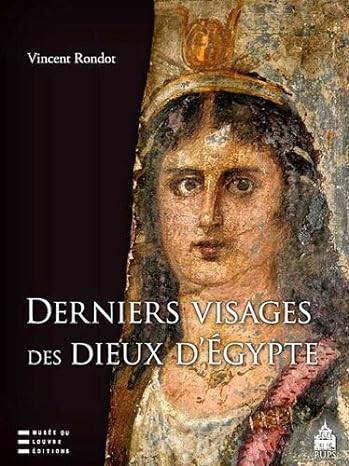

RONDOT 2013:

Κατά τη διάρκεια ενός αιώνα, επίσημες ή μυστικές ανασκαφές στην αιγυπτιακή επαρχία Φαγιούμ έχουν αποκαλύψει σημαντικό αριθμό ξύλινων πινάκων εντός πλαισίου οι οποίοι είναι ζωγραφισμένοι με θεότητες. Σήμερα διαθέτουμε ένα σώμα περίπου πενήντα από αυτούς τους πίνακες, πλήρεις ή αποσπασματικούς. Είναι σύγχρονοι με τις αποκαλούμενες προσωπογραφίες σε μούμιες «Fayoum» και απ' όσο μπορούμε να κρίνουμε, ζωγραφίστηκαν τον 2ο αι. μ.Χ. Αυτοί οι πίνακες είναι πολύτιμοι για την ιστορία της τέχνης γιατί προσφέρουν μιαν εξαιρετική μαρτυρία για την ζωγραφική επί τρίποδος [ΣτΣ: οκρίβας ή καβαλέτο], όπως αυτή ασκούνταν στον ελληνο - ρωμαϊκό κόσμο, και την σημασία της οποίας αντιλαμβανόμαστε χάρη στις κλασικές λογοτεχνικές πηγές (ιδιαίτερα του Πλίνιου του Πρεσβυτέρου) αφιερωμένες στα αριστουργήματα των μεγάλων δασκάλων που έφυγαν από την ζωή. Από τη σκοπιά της αιγυπτιακής αρχαιολογίας, μας αποκαλύπτουν τις βαθιές αλλαγές στην μορφή λατρειών και των τελετουργιών των ναών, αφού αυτές οι ζωγραφιές λειτουργούν με τον τρόπο των εικόνων. Δείχνουν επίσης -και ίσως πάνω απ' όλα- πώς μια θρησκεία τόσον αρχαία όσο η αιγυπτιακή θρησκεία, και με κώδικες αναπαραστάσεως τόσον περιοριστικούς όσο ο φαραωνικός κανόνας, μπόρεσε τελικά να δεχτεί ότι ο Ελληνισμός έφτασε να αλλάξει ριζικά την τριχιλιετή. εικονογραφία των θεών του, μεταμορφώνοντας τον Σόμπεκ σε προφίλ και με το κεφάλι ενός σαυριανού σε γενειοφόρο χαρακτήρα που κρατά τον κροκόδειλο του στα γόνατά του, όπως ο Δίας τον κεραυνό του. Για πρώτη φορά, αυτό το σώμα παρουσιάζεται εδώ με αιτιολογημένο τρόπο, σε έγχρωμη φωτογράφιση (Henri Choimet), καθώς και εικονογραφική περιγραφή και ανάλυση. Έτσι σχηματίζονται πολλά πάνθεον, αυτό της αρχαίας Αιγύπτου τώρα δίπλα σε αυτό των θεών του ελληνορωμαϊκού κόσμου ή ακόμα και αυτό των θεοτήτων που λατρεύονται από ένα έθνος (οι Άραβες των ελληνικών κειμένων;) εγκατεστημένο στην επικράτειά του.

C. Breil, L. Huestegge & A. Böckler. 2022. "From eye to arrow: Attention capture by direct gaze requires more than just the eyes," Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics (2022) 84, pp. 64–75.

----------------------------------- ---------------------------------

Tomoko Isomura, Katsumi Watanabe. 2020. "Direct gaze enhances interoceptive accuracy," Cognition 195, https://www.sciencedirect.com/.../pii...)

Abstract: Direct-gaze signals are known to modulate human cognition, including self-awareness. In the present study, we specifically focused on ‘bodily’ self-awareness and examined whether direct gaze would modulate one’s interoceptive accuracy (IAcc)—the ability to accurately monitor internal bodily sensations. While viewing a photograph of a frontal face with a direct gaze, an averted face or a mere white cross as a baseline, participants were required to count their heartbeats without taking their pulse. The results showed higher IAcc in the direct-gaze condition than in the averted-face or baseline condition. This was particularly the case in participants with low IAcc at baseline, indicating that direct gaze enhanced the participants’ IAcc. Importantly, their heart rate was not different while viewing the direct gaze and averted face, suggesting that sensitivity to interoceptive signals, rather than physiological arousal, is heightened by direct gaze. These findings demonstrate the role of social signals in our bodily interoceptive processing and support the notion of the social nature of self-awareness.

Keywords: Interoception; Heartbeat; Gaze; Self-awareness

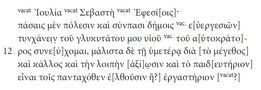

ΕΠΙΣΤΟΛΗ ΙΟΥΛΙΑΣ ΣΕΒΑΣΤΗΣ ΠΡΟΣ ΕΦΕΣΙΟΥΣ (Souris 2009)

Μπορεί να είναι εικόνα κείμενο που λέει

"*** Ιουλία **Σεβαστή *** Εφεσί[οις]

πάσαις μέν πόλεσιν καί σύνπασι δήμοις *** ε[ύεργεσιών] τυνχάνειν τού γλυκυτάτου μου vioũ vac. τού α[ύτοκράτο]- ρος συνε[ύχομαι, μάλιστα δέ τη ύμετέρα διά [τό μέγεθος] καί κάλλος καί τήν λοιπήν [αξίζωσιν καί τό παδ[ευτήριον]είναι τοϊς πανταχόθεν έ[λθούσιν 기?] έργαστήριον [****?]"

Bertolazzi, p. 3

The dominant philosophical thought in Domna’s salon was Neopythagoreanism, a Hellenistic school that, among other things, theorized the cosmic origin of imperial power 17 .Bertolazzi, p. 237-238, nn. 874, 875

874 Dio mentions Domna’s philosophical salon twice, once during the narration of Severus’ reign (76 [75].15.6), and, later on, in reference to Caracalla’s reign (78 [77].18.3). It seems, therefore, that Domna’s relationship with sophists and philosophers was a well-known fact among her contemporaries. On the topic cf. Levick 2007, 107-123 with further references. It is also interesting to note that, as far as we know, all the philosophers and literati having something to do with Domna’s circle were from the Greek part of the Empire, a circumstance that would make this salon purely Hellenistic (as stressed by Buraselis 1991, 34). Contrary to what is argued by Levick 2007, 163, there is no reason to think that this circle was restricted to people from Greece and Asia Minor only. According to the Suda (s.v. Φρόντων [Adler p. 763]), the Emesene sophist Fronto {Marcus Cornelius Fronto .. taught as a child by the Greek paedagogus Aridelus, Later, he continued his education at Rome[7] with the philosopher Athenodotus and the orator Dionysius} was in Rome at the time of Severus, and he is described as the rival teacher of Philostratus. These facts have led Buraselis 1991, 35 to think that Fronto followed Domna from Emesa to Rome. Curiously enough, he bequeathed his property to his nephew Cassius Longinus, the famous rhetorician who was teacher and chief counselor of Zenobia, the queen of Palmyra.

875 Vita Apoll. 1.3: καὶ προσήκων τις τῷ Δάµιδι τὰς δέλτους τῶν ὑποµνηµάτων τούτων οὔπω

γιγνωσκοµένας ἐς γνῶσιν ἤγαγεν Ἰουλίᾳ τῇ βασιλίδι. Μετέχοντι δέ µοι τοῦ περὶ αὐτὴν κύκλου,

καὶ γὰρ τοὺς ῥητορικοὺς πάντας λόγους ἐπῄνει καὶ ἠσπάζετο, µεταγράψαι τε προσέταξε τὰς

διατριβὰς ταύτας καὶ τῆς ἀπαγγελίας αὐτῶν ἐπιµεληθῆναι (‘The notebooks containing the memoirs of Damis [scil. a disciple of Apollonius] were unknown until a member of his family brought them to the attention of the empress Julia. Since I was a member of her circle - for she admired and encouraged all rhetorical discourse - she set me to trancribe these works of Damis and to take care over their style [transl. by Christopher P. Jones]’). Some scholars have rejected the historical accuracy of this information, arguing that Philostratus’ references to Damis’ writings are fictional expedients to confer authority upon his work (on the topic cf. the synopses of the debate in Kemezis 2014a, 63-68; Sfameni Gasparro 2007, 283-184). Kemezis 2014a has also questioned the existence of a relationship between Domna and Philostratus. In my view, the existence of this connection seems difficult to confute. Philostratus mentions Domna’s circle of sophists in VS 2.30 too, and there is no reason to believe that he lied to his contemporaries regarding his affinity with this circle (similar considerations are expressed by Sfameni Gasparro 2007, 283). Furthermore, he sent a letter concerning Plato’s critique of rhetoric to the Augusta (Ep. 73). The autenticity of this document has also been debated, but Robert Penella, the editor and commentator of Apollonius’ letters, has reaffirmed its genuineness (cf. Penella 1979). ...................... Bertolazzi, p. 275Curiously enough, both Semiramis and Nictoris, the oriental queens that, according to Dio, Domna wanted to emulate, put an end to their lives while facing conspirators1011. Thus, besides the desire to rule alone, the way in which these queens left the world may have suggested to Dio the comparison between them and Domna. In the eyes of the historian, to all intents and purposes, Domna decided to die as an oriental queen1012. Correspondences with the suicides of Hellenistic queens can provide further food for thought. As noted above, Cleopatra committed suicide in order to avoid being dishonored and taken to Rome as a captive. More than two centuries before, in 287 BCE, the noble and influential Phila, daughter of Antipater and wife of Demetrius Poliorcetes, committed suicide after her husband had been driven out of Macedonia and had lost his throne1013. Both stories display a common trait, the desire to die rather than to face the consequences of the loss of power and prestige connected with royal rank. In short, Domna’s tragic end seems to show consistency with her middleeastern cultural background. ----------------------------------------------------------------https://prism.ucalgary.ca/.../7f6e988... --

1 ημ.

Απάντηση

Bertolazzi, p. 277

Finally, her decision to let herself die rather than to retire to a private station seems to be quite an unusual one, and makes Domna more similar to an Hellenistic queen, like Phila, rather than to a Roman imperial woman, like Domitia Longina.

......

Bertolazzi, p. 330

Considering the fact that her life was not in immediate danger, her decision to let herself die is quite surprising, and seems to follow Hellenistic customs rather than Roman habits.

...........................

Bertolazzi, p. 331

Domna’s refusal to abandon her royal retinue and to retire to private life provides not only an idea of the great prestige that she had attained during the reigns of Severus and Caracalla, but also a key element in better understanding her complex character. This is her strong Hellenistic cultural background, which makes her a unique imperial woman in Roman history. In fact, she did not limit herself to playing the traditional role of an Augusta, i.e. that of an austere Roman matron, wife of the emperor and, possibly, mother of his children. Rather the contrary, she appears to have been determined to affirm the importance of her oriental lineage since the first stages of her marriage with Severus. L. Septimius Bassianus, the name given to their firstborn son in 188, included the cognomen of Domna’s father, Julius Bassianus. This was the great priest of the Sun-god Elagabal, a member of the Emesene nobility that, during the first century CE, had ruled over the small (but importantly regarded) kingdom of Emesa and formed relationship with other middle eastern dynasties. During the second century, the kingdom lost its independence, but the Emesene elite still maintained prestige and ambitions. ......................................

Bertolazzi, p. 335

It is important to note that she is the first imperial woman who had a group of philosophers gathered around her, and that only Greek individuals are documented members of this group, which could, consequently, be considered a Hellenistic circle.

.......................

Bertolazzi, p. 340

Rather, Domna’s cultural tastes probably had a deep impact on Caracalla’s personality and policies. Besides showing particular attention towards divine matters on his coins, this emperor displayed a great interest for Hellenism. He paid honors to one of Domna’s favorite philosophers, Apollonius of Tyana, and dedicated a shrine to him; he put great effort into imitating Alexander the Great and, finally, tried to marry the daughter of the Parthian king Artabanus V. Ancient historians branded these initiatives as the extravagances of a tyrannical and mentally unstable ruler. They become, nonetheless, understandable when one considers Domna’s cultural background and philosophical preferences. By honoring Apollonius, Caracalla demonstrated sharing his mother’s Neopythagorean view concerning kingship.

......................

Bertolazzi, pp. 340-341

Her final decision to die rather than to retire to private life finds no comparison among Roman imperial women, and seems to recall the suicides of several Hellenistic queens who did not want to be dishonored by losing their royal status.

................................................................

Bertolazzi 2017, p. 341

She represents something more. She seems, in sum, to have been a Hellenistic queen who, in a shrewd and original manner, played the role of Roman Augusta with great success. Bertolazzi, R. (2017). Julia Domna: Public Image and Private Influence of a Syrian Queen (Doctoral thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada). Retrieved from

https://prism.ucalgary.ca. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26693

https://www.worldhistory.org/Amastris...

While Phila, the wife of Demetrius I of Macedon (c. 336 - c. 282 BCE), was the first woman to receive the title basilissa (c. 305/4 BCE), these were the first coins ever to be issued in the name of a queen or any living woman and should thus be interpreted as a bold statement of female authority. It would be remarkable, to say the least, if the Persian Amastris reigned independently – that is, as female sovereign, rather than a king's wife. She was royal by birth, Dionysius had claimed kingship shortly before his death, and Lysimachus had likewise laid claim to kingship. It appears, then, that Lysimachus had arranged for Amastris to rule as queen along the Paphlagonian coast.

............

The First basilissa: Phila, Daughter of Antipater and Wife of Demetrius Poliorcetes

Η ΣΥΝΑΝΤΗΣΗ ΜΕ ΤΟΝ ΑΠΟΛΛΩΝΑ ΤΥΑΝΕΑ & ΤΟΝ ΒΟΥΔΙΣΜΟ

Kushan ring with Septimus Severus and Julia Domna. Gold finger ring from Ancient India. Kushan period, early 3rd century AD. Solid gold ring, of typical Roman shape, fabricated rather than cast. The intaglio bezel was made separately and carefully fitted into the ring (the join visible only in a slightly damaged area on the edge of the bezel). The bezel is decorated with vis-à-vis portraits of Septimius Severus (laureate head left) and Julia Domna (draped bust right with elaborate coiffure), beneath which is a Gupta Brahmi inscription in a characteristic square-serif style: Damputrasya Dhanguptasya ([Seal of] Dhangupta son of Dama). This image has been mirrored in order to render the inscription legible.

Χρυσό Δαχτυλίδι από την Ινδία: Κοσσανικό (Kushan) με τον Σεπτίμιο Σεβήρο & την Ιουλία Δόμνα (αρχές 3ου αιώνα μ.Χ.) Δαχτυλίδι από μασίφ χρυσό, τυπικού ρωμαϊκού σχήματος, κατασκευασμένο και όχι χυτό. Το έμβλημα κατασκευάστηκε ξεχωριστά και τοποθετήθηκε προσεκτικά στο δαχτυλίδι (η ένωση είναι ορατή μόνο σε μια ελαφρώς κατεστραμμένη περιοχή στην άκρη της στεφάνης). Το πλαίσιο είναι διακοσμημένο με πορτραίτα του Σεβήρου (κεφαλή αριστερά) και της Ιουλίας Δόμνας (προτομή ντυμένη δεξιά με περίτεχνη κόμμωση), κάτω από την οποία υπάρχει μια επιγραφή σε Gupta Brahmi σε χαρακτηριστικό τετράγωνο serif ύφος: Damputrasya Dhanguptasya ([Σφραγίδα του] Dhangupta υιου της Dama). Αυτή η εικόνα έχει καθρεφτιστεί για να καταστεί ευανάγνωστη η επιγραφή. Kushan ring with Septimus Severus and Julia Domna.jpgΗ ΣΥΝΑΝΤΗΣΗ ΜΕ ΤΟΝ ΑΠΟΛΛΩΝΑ ΤΥΑΝΕΑ & ΤΟΝ ΒΟΥΔΙΣΜΟ

The decorative epithet “Damputrasya Danaguptasta” in Prakrit Brahmi inscribed on a gold ring depicts Julia Domna (160 – 217 CE) facing Septimus Severus (193 – 211 CE), the first Roman Emperor from Africa (fig.14).[16]

The facing profile busts common in funerary dedications adopts the style of Roman coinage. The ornamental square serif characteristic of the Gupta script has the flourish of an accomplished scribe in the royal court.

The spectacular jugate ring introduces the Gupta dynastic name as Danagupta, meaning protector or governor of wealth and prosperity. The dedication of the revered relic is by the son of Domna (Damputrasya); commemorative relics as such accrue merit to the devout. In this context, the name appellation Dana and Dana – deva from an earlier inscription from North India describes Bhuti as wealth, prosperity, ornament, andadornment. Since Julia Domna’s two sons had died dreadfully, the self-proclaimed “Son of Domna” could be her grand-nephew, Elagabalus or Heliogabalus (Ηλιογάβαλος) of Emesa (Έμεσα ήτοι σύγχρονη Homs, τέως Σελευκιδική πόλη) , the Roman emperor from 218 to 222. The votive ring was indeed deposited in a stupa reliquary by 222 CE before the decline of Rome started. The intermediaries were assuredly the wealthy Nabataean merchant princes vigorously contributing to the Mahayana mortuary cult. Significantly, the royal mausoleum of Augustus Caesar (63 BCE – 14 CE), erected in 28 BCE by the emperor on the Campus Martius in Rome, is prototypical of the stupa monuments in South Asia.[17]

Elagabalus, her great-nephew, deified Julia Domna; her statue shows her as a priestess inthe Imperial cult with covered head wrapped in voluminous himation draped like a saree (fig.15).The Jamalpur Yakshi holding a sprig near her pudendum restates the suggestive sprig of fruit in Domna’s hand. The lotus and Amrit Kalash pedestal identify the Yakhsi as Sri Devi; the goddess of fertility and nourishment in the afterlife offers her breast in the manner of Isis-Venus(fig.16).[18]

How we comprehend the past in the present depends on our knowledge and understanding of the context they were created. Domna, known as Philosopher Queen, was powerful and influential. Her crossing point with the Buddhist culture occurred when she chose to give up life by starvation. Her mysterious Nirvana, similar to the “Starving Buddha,” described by historians as her inability to deal with disappointments in life, does not give credit to her philosophical acumen or her extensive appeal as a goddess worshipped across the empireunder various local titles.[19]

By birth, Julia Domna of the Emesene dynasty was the eldest daughter of Julius Bassianus, the High Priest of Syrian sun god Elagabalus integrated into the Roman pantheon as Sol (Surya, ΗΛΙΟΣ). The togate Buddha enlightened by the halo resembles Sol Invictus or Invincible Sun in the Roman imperial cult. Chakravartin, the world ruler in the image of the Sun, advocates monotheistic devotion to the God-King worshiped as Vishnu and his Avatars, including the Buddha, in the following Gupta period. Julia Domna admired Apollonius of Tyana (ΑΠΟΛΛΩΝΙΟΣ ΤΥΑΝΕΥΣ, c.15 – 96CE), the wandering philosopher and magician in India mistaken for Christ and now understood as the teachings of Buddha contemporary to Pythagoras.[20]

“The Life of Apollonius,” commissioned by Domna, was written by Flavius Philostratus (ΦΙΛΟΣΤΡΑΤΟΣ Ο ΑΘΗΝΑΙΟΣ εκ ΛΗΜΝΟΥ), a sophist philosopher in her Inner Circle.[21]

Philostratus combined Pythagorean Neo-Platonism, mystic relation between man and divinities. Domna agreed with his political philosophy, personal ethics, and views on the worship of statues representing deities and the immortal soul in the image of the sun god.

SOURCE: "Buddhist and Gupta Imagery in Conjunction with Rituals and Linguistic Anthropology", Arputharani Sengupta

https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/...

A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology (William Smith, Ed.), s.v. Domna, Ju'lia: By her commands Philostratus undertook to write the life of Apollonius, of Tyana, and she was wont to pass whole days surrounded by troops of grammarians, rhetoricians, and sophists.

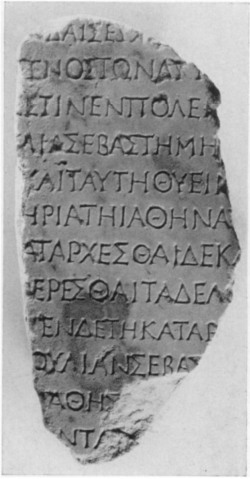

DECREE ASSIGNING DIVINE HONORS TO JULIA DOMNAhttps://www.ascsa.edu.gr/uploads/medi...

DECREE ASSIGNING DIVINE HONORS TO JULIA DOMNAhttps://www.ascsa.edu.gr/uploads/medi...

Στο Βρετανικό Μουσείο φυλάσσεται θραύσμα λευκού μαρμάρου φέρον επιγραφή στην Ελληνική αναφερόμενη στον θάνατο - αυτοκτονία της Ιουλίας Δόμνας λόγω ασιτίας .. (BM reg. nr. 1874,0205.14: A fragment of white marble, broken on all sides with the remains of three lines of Greek inscription. The inscription is a dedication to Julia Domna, wife of the emperor Septimius Severus and erected in her lifetime)

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Julia Domna's use of Athena is apparent in a fragmentary replica of the socalled 'Athena Medici' statue type in Thessaloniki (Figs. 1-2).3 These fragments are well known in studies of the Medici statue type and have additional interest for technical reasons, since they stem from an acrolithic statue.4 The photographs clearly show how the head has the cheeks prepared for the fastening of additional hair. Further, the face has the characteristic features, like the distinctive mouth, of Julia Domna.

Η παραβολή της Ιουλίας Δόμνας με την Αθηνά είναι εμφανής σε ένα αποσπασματικό αντίγραφο του αποκαλούμενου αγάλματος «Athena Medici» από την Θεσσαλονίκη (Εικ. 1-2) . Αυτά τα θραύσματα είναι καλώς γνωστά στις μελέτες αυτού του τύπου αγάλματος (του Medici) και παρουσιάζουν επιπλέον ενδιαφέρον για τεχνικούς λόγους, αφού προέρχονται από ακρολιθικό άγαλμα.4 Οι φωτογραφίες δείχνουν καθαρά πώς η κεφαλή έχει τα μάγουλα προετοιμασμένα για το στερέωση πρόσθετων μαλλιών. Περαιτέρω, το πρόσωπο έχει τα χαρακτηριστικά της Ιουλίας Δόμνας, ιδιαίτερα το στόμα της ... ΠΗΓΗ: Lundgreen 2004

Αναφορικά με την 'ταύτιση' ή παραβολή της Ιουλίας Δόμας με την Αθηνά σημειώνεται ότι η σχετική πρακτική έχει τις ρίζες της στην Ελληνιστική εποχή .. Γιά παράδειγμα αυτό υποδηλώνεται ήδη στην ελληνιστική περίοδο, ένα δε πρώιμο παράδειγμα παρέχεται από τον Καλλίμαχο όπου αυτός αφομοιώνει - ταυτίζει την Βερενίκη ΙΙ (πρίν τον γάμο της) με την Αθηνά ..

Reconstruction by G. Despinis of the acrolithicAthena Medici/Julia Domna statue, Thessaloniki Museum,inv. no. 877 (after Despinis, G. 1975. Aκρόλιθα. Αthens, fig. 3).

Reconstruction by G. Despinis of the acrolithicAthena Medici/Julia Domna statue, Thessaloniki Museum,inv. no. 877 (after Despinis, G. 1975. Aκρόλιθα. Αthens, fig. 3).Έργα που χρησιμοποιούνται για πορτρέτα, κυρίως γυναικών της αυτοκρατορικής οικογένειας, αποτελούν μια ακόμη κατηγορία «αντιγράφων» θεϊκών εικόνων της Κλασικής περιόδου. Αυτό συμβαίνει με ένα ακρολιθικό άγαλμα σε μέγεθος μεγαλύτερο του κανονικούμε του β' αιώνα μ.Χ. στη Θεσσαλονίκη (Εικ. 20.8). Μόνο το κεφάλι του, το οποίο επανακόπηκε αντιγράφον κεφαλή της Ιουλίας Δόμνας, συζύγου του Σεπτίμιου Σεβήρου (193–211), το δεξί πόδι και το δεξί χέρι σώζονται.37 Το έργο αρχικά απεικόνιζε τον τύπο της Αθηνάς των Μεδίκων, όρθια μορφή που φορά ελαφρύ χιτώνα με άφθονες πτυχές σημειωμένες κυρίως στο δεξί πόδι, που προεξέχει κάτω από τον βαρύ αττικό πέπλο.

Ο τύπος έχει συνδεθεί με πρωτότυπο του Φειδία ή ένός από τους μαθητές του και χρονολογείται γύρω στο 430 π.Χ. Έχει προταθεί ότι αντικατοπτρίζει το χάλκινο άγαλμα της Αθηνάς Προμάχου του Φειδία στην Αθηναϊκή Ακρόπολη.38 Μετά την Αθηνά Παρθένο, η Αθηνά Μεδίκων είναι ο τύπος που προτιμάται περισσότερο για αναπαραστάσεις της θεάς στην Αυτοκρατορική περίοδο στην Ελλάδα, από την οποία προέρχονται εννέα εκδοχές ποικίλου μεγέθους και ποιότητας χειροτεχνίας.

Τα έργα αυτά χρονολογούνται κυρίως στον δεύτερο αιώνα μ.Χ., την εποχή του Αδριανού και των Αντωνίνων, και τα περισσότερα από αυτά προέρχονται από την Αθήνα.39 Η μελέτη της προέλευσης και χρήσης εκδοχών αυτού του τύπου –όπου είναι δυνατόν– έδειξε ότι ενώ μεγάλα έργα που βρίσκονταν σε βίλες και δημόσια κτίρια προέρχονταν από την Ιταλία, αφιερωτικά αγαλματίδια και ανάγλυφα προέρχονταν από την Ελλάδα και ιδιαίτερα από την Αθήνα, πράγμα που σημαίνει ότι το αρχέτυπο υπήρχε ακόμα τον δεύτερο αιώνα μ.Χ. και διατήρησε τον λατρευτικό του χαρακτήρα.40

Το άγαλμα της Θεσσαλονίκης είναι το μοναδικό δείγμα του τύπου με το δεξί χέρι που σώζεται, επιβεβαιώνοντας ότι η θεά κρατούσε ένα δόρυ στο χέρι, καθώς και το μοναδικό που χρησιμοποιήθηκε για πορτρέτο, παρόλο που το άγαλμα ήταν κατασκευασμένο εκ νέου.41

.. ............

Στυλιανός Ε. Κατάκης, 20 Αντίγραφα Ελληνικού Αγαλματίου από την Ελλάδα στη Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορική Περίοδο

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

p. 630-631

Works used for portraits, mainly of women of the Imperial family, constitute one more class of ‘copies’ of divine images of the Classical period. This is the case with a larger-than-life second-century A.D. acrolithic statue in Thessaloniki (Fig. 20.8). Only its head, which was recut into a portrait of Julia Domna, wife of Septimius Severus (A.D. 193–211), right leg, and right hand survive.37 The work originally portrayed the Athena Medici type, a standing figure wearing a light chiton with an abundance of folds marked mainly on the right leg, which projects beneath the heavy Attic peplos.

The type has been associated with Pheidias or one of his pupils and dated to around 430 B.C.; it has been suggested that it reflects Pheidias’ bronze statue of Athena Promachos on the Athenian Acropolis.38 After the Athena Parthenos, the Athena Medici is the type most favoured for representations of the goddess in the Imperial period in Greece, from which come nine versions of varying size and quality of craftsmanship.

These works are dated mainly to the second century A.D., the age of Hadrian and the Antonines, and most of them come from Athens.39 The study of the origin and use of versions of this type – wherever possible – has shown that while large works located in villas and public buildings came from Italy, dedicatory statuettes and reliefs came from Greece and especially from Athens, which means that the archetype was still in existence in the second century A.D. and retained its cultic character.40

The Thessaloniki statue is the only example of the type with the right hand preserved, confirming that the goddess held a spear in that hand, as well as the only one which was employed for a portrait, even though the statue was recut.41

..............

Katakis 2019.

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑhttps://www.marionette.gr/history.phpΗ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ ΤΗΣ ΜΑΡΙΟΝΕΤΑΣ, Θέατρο Μαριονέττας 'Γκότση'https://l.facebook.com/l.php?u=https%..., J. 2013. Maternal Megalomania. Julia Domna and the Imperial Politics of Motherhod, Baltimore.

https://academic.oup.com/edited-volum..., T. F. "The Origin of Icons," in The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks), ed. E. C. Schwartz, pp. (ed.)

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf..., C., L. Huestegge, A. Böckler. 2022. "From eye to arrow: Attention capture by direct gaze requiresmore than just the eyes," Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics 84, pp. 64–75.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science... Isomura & Katsumi Watanabe. 2020. "Direct gaze enhances interoceptive accuracy," Cognition 195 (2020) 104113, pp. 1-5.

https://publications.dainst.org/journ..., G. 2009. "A παιδεύσεως ἐργαστήριον for «Hellenes» in Ephesos. Iulia Domna’s letter to the city," Chiron 39, pp. 359–362.

https://prism.ucalgary.ca/server/api/..., R. 2017. Julia Domna: Public Image and Private Influence of a Syrian Queen (diss. Univ. of Calgary, Canada).

Rondot, V. 2013. Derniers visages des dieux d'Egypte: Iconographies, panthéons et cultes dans le Fayoum hellénisé des IIe-IIIe siècles de notre ère, Sorbonne Univ. Press.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/45134362

Oliver, J. H. 1940. "Julia Domna as Athena Polias," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 51, Supplementary Volume I, pp. 521-530.

https://www.academia.edu/22145767/Use..., B. 2004. "Use and Abuse of Athena in Roman Imperial Portraiture: The Case of Julia Domna," Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens 4, pp. 69-91.

Arputharani Sengupta. 2021. "Buddhist and Gupta Imagery in Conjunction with Rituals and Linguistic Anthropology", <https://www.academia.edu/52108107/Bud... (23 May 2024).

https://www.academia.edu/70186175/20_..., S. E. 2019. "Copies of Greek Statuary from Greece in the Roman Imperial Period," in Handbook of Greek Sculpture, pp. 620-654.https://sitestatic.shopster.gr/6150c0..., Γ. Ι. 1975. "Ακρόλιθα αγάλματα των ρωμαϊκών χρόνων," Κλασική παράδοση και νεωτερικά στοιχεια στην πλαστική της ρωμαϊκής Ελλάδας, σελ. 19-34.

https://www.amth.gr/exhibitions/exhib... AΚΡOΛΙΘΟΥ AΓAΛΜAΤΟΣ ΑΘΗΝAΣ ΤYΠΟΥ MEDICI

May 4, 2024

LYCOPHRON'S ALEXANDRA

Η υποτίμηση των Ελλήνων και η φιλοτρωική διάθεση που διαπερνά την Αλεξάνδρα με αποκορύφωση το εγκώμιο προς τη Ρώμη/νέα Τροία (Αλεξ. 1226-82. 1446-50) υποδεικνύουν ότι το ποίημα έχει συντεθεί προς ευχαρίστηση των Ρωμαίων. Το κομμάτι Αλεξ. 1226-82 αφορά στην κυριαρχία των Ρωμαίων επί της ιταλικής χερσονήσου, όπως αυτή σφραγίστηκε με την ήττα του Πύρρου (275 π.Χ.) κι ολοκληρώθηκε με την υποταγή των πόλεων της Μ. Ελλάδας (272/270 π.Χ.). Προτού η Ρώμη αρχίσει την περαιτέρω επέκταση προς ανατολάς και δυσμάς, έπρεπε πρώτα να εδραιώσει την κυριαρχία της στην ιταλική χερσόνησο, πράγμα που αποτελούσε μεγάλο κατόρθωμα. Η φράση γης και θαλάσσης σκήπτρα και μοναρχίαν λαβόντες (Αλεξ. 1229-30) υπαινίσσεται ότι η Ρώμη εξουσιάζει μόνη κι ανενόχλητη τη γη της Ιταλίας (από την Πίσα, το Ariminum μέχρι τον πορθμό της Μεσσήνης) και τις γύρω θάλασσες (Αδριατική, Ιόνιο, Τυρρηνικό). Δημιουργός της Αλεξάνδρας είναι ο ποιητής και γραμματικός Λυκόφρων από τη Χαλκίδα, για τον οποίο μαρτυρούνται συγγενικοί δεσμοί με το κατωιταλιωτικό Ρήγιο. Μέσα από βιογραφικά στοιχεία του ποιητή αλλά και μέσα από αναγωγές σε ιστορικά γεγονότα και κοινωνικές καταστάσεις των πόλεων της Μ. Ελλάδας από την εποχή του αποικισμού μέχρι τον 3ο αι. π.Χ., φωτίζονται διάφορα σημεία του ποιήματος όπως είναι η εμφατική αναφορά στη Σκύλλα, η απέχθεια σ' οτιδήποτε λοκρικό, η προβολή των Μεσσηνίων ηρώων (Αφαρητίδες) και ο ψόγος των Σπαρτιατών ως πανούργων. (Από την παρουσίαση στο οπισθόφυλλο του βιβλίου)

The disparagement of the Greeks and the pro-Trojan attitude that pervade the Alexandra, culminating in the encomium to Rome/new Troy (Alex. 1226-82, 1446-50), suggest that the poem was composed for the gratification of the Romans. The segment Alex, 1226-82 alludes to the dominion of the Romans over the Italian peninsula, as this was sealed by the defeat of Pyrrhus (275 BC) and completed with the subordination of the cities of Magna Graecia (272/270 BC). Before Rome could begin further expansion to the East and West, it had first to consolidate its domination of the Italian peninsula, which, once accomplished, was a brilliant achievement. The words γης και θαλάσσης σκήπτρα και μοναρχίαν λαβόντες (Alex. 1229-30) declare that Rome, alone and unopposed, rules the land of Italy (from Pisa. Ariminum, to the Straits of Messina) and the surrounding seas (Adriatic, Ionian, Tyrrhenian). The creator of the Alexandra is the poet and grammarian Lycophron of Chalcis about whom there is evidence that he maintained kinship bonds with Rhegium in Southern Italy. Numerous of the poet's objectives lying behind the writing of the Alexandra are illuminated through details known about his life as well as via the observations I have made concerning historical events and social conditions of the cities of Magna Graecia from the era of colonization until the 3rd cent. BC: among these are the emphatic reference to Scylla, aversion to anything Locrian, the championing of the Messenian heroes (the Apharetidae) and the criticism of the Spartans' guile. (From the publisher)ΠεριεχόμεναΗ σκιαγράφηση των ηρώωνΤο κοινό του ποιητή - Σκοπός σύνθεσης της ΑλεξάνδραςΟι προφητείες για τη δόξα της ΡώμηςΑλεξ. 1226-31Αλεξ. 1446-50Η ταυτότητα του ποιητήAn outline of the heroesThe poet's audience - The intent behind the composition of the AlexandraThe prophecies concerning the glory of RomeAlex. 1226-31Alex. 1446-50The identity of the poetΒιβλιογραφία / BibliographyΓενικό ΕυρετήριοGeneral IndexΒ' Σκέμπης

Recent years have witnessed a boom in scholarship on Lycophron, with magisterial editions, translations and book-length studies. In the light of this ever-growing enthusiasm, a 760-page-long volume devoted to the eclats d'obscurite of this controversial poem is a reason to be thankful. In the Introduction the Editors re-assess the current state of Lycophronic studies, sketching out the cultural and literary contexts of the Alexandra, and pin down all those factors that conduce to what they (and others) wish to term 'obscurity'. They aim to advance the debate over the [..] author's identity, to examine closely the poem's veil of obscurity, and to appreciate its richness from a literary perspective.

Section 1 contains case studies which explore cross-generic dialogues. Starting with Homer, the geographical construction of the Iliadic Catalogue of Ships reflecting the provenance of the gathered contingents exerts a formative influence on the catalogic middle section of the Alexandra which recounts the abortive nostoi of the heroes (Sens). To reverse the order of this arrangement is to lay focus on the places where the nostic trips are terminated and to epitomise the tense relation between epic and the Alexandra's tragic edge. Yet the reworking of passages stemming from epic and tragedy may also entail a shifting perspective that triggers a parodic stance towards established traditions (Kolde). In a similar vein, prologue and epilogue of the messenger speech are to be inscribed in tragic contexts. Apart from showing that outset and closure anchor in Prometheus Bound and Aeschylus' Agamemnon by means of internal twists and allusions, Looijenga argues for the prologue's meta-level that advertises the allurements of the main narrative. Beyond traditional approaches to intertextuality, Lycophron occasionally reconfigures the tradition. His rendering of Pindaric visualisations of heroes such as Ajax and Pelops conjures up an anti-hero image that displays a personal tinge in the way myths are treated (Gigante Lanzara). As for historiography, West's lucid treatment of Lycophron and Herodotus argues that, alongside individual episodes, the narrative techniques of digression, flashback and prophecy have a Herodotean basis.

Section 2 tackles issues of enunciative circumstances, discursive strategies, authorial attitudes and semantics that make up the poem's literary system. In an enthralling chapter, Cusset analyses the 'reflexive mirroring' that issues from the absorption of Cassandra's prophetic voice into the messenger speech and amounts to a well-honed 'putting into enunciation'. It is precisely this reflexive quality that provides new insights for a proper reading of the poem inasmuch as it resonates with the production of poetry. Taking her cues from the plasticity of the word within the context of orality, Kossaifl argues, in a rather hazy manner, for the poem's 'enunciative polyphony'. Lambin's musings on the function 'author', a category made fertile for Greek poetry by Calame in Identites d'auteur dans I'Antiquite et la tradition europeenne (2004), pp. 11-39, are a highlight of the collection. Lycophron enriches what falls within the Foucauldian category in so far as he cares to establish a relation with his readers that allows for a more profound access to his text than the limited one the Hellenistic posture of the erudite poet is willing to grant. The question of authorship is viewed in relation to scholarly practices: the re-semanticisation of hapax legomena through etymology employs exegetical principles familiar to Lycophron of Chalcis from his editorial work and thereby suggests him as author of the poem (Negri).