Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 41

December 17, 2012

The DD Virus

Comcast Center

Last week, after lunch at a bistro on Rittenhouse Square, I dropped in at the Comcast Center to look at the huge video screen—a digital mural—in the lobby. I had written about the screen two years ago, finding it captivating, and since the content regularly changes, I thought it would be fun to see it again. I watched for a while and found my attention wandering. The material seemed less creative, less witty and sophisticated, more predictable. Apart from an interminable clip of close-ups of baseball players in action, the segments seemed shorter, too. Then it dawned on me. The Comcast wall had succumbed to the DD virus. It had been Dumbed Down.

DD is a pernicious modern malady that, sooner or later, seems to affect everything. The New York Times has certainly caught the bug; Arts & Leisure now means less art and more leisure. The PBS News Hour, once challenging with Robert McNeil, Jim Lehrer, and the redoubtable Charlayne Hunter-Gault, has become flabby and predictable. Masterpiece Theater, home to “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy,” and “Brideshead Revisited” now broadcasts bromides like “Downton Abbey.” As for architecture, can one really imagine that a Louis Kahn—or a Robert Venturi—would be able to break through today?

December 14, 2012

Modernism the Good

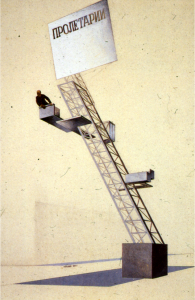

I’ve been reading David Watkin’s Morality and Architecture and I’m struck by the parallel that he draws between modernism and totalitarianism. Now, the conventional story, told and re-told by advocates of the International Style, was that modernist architecture was a moral force, not only opposed to (bad) nineteenth-century Beaux Arts architecture, but also to Nazism and Fascism. This claim was lent credence by the fact that so many leading modernists—Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Eric Mendelsohn, Marcel Breuer—had fled Nazi Germany. That Le Corbusier happily offered his services to the rightist Vichy regime in France, that Philip Johnson was sympathetic to the National Socialists, and that Mussolini’s Italy sponsored some excellent modernist architecture, did not tarnish the story. Modernism was on the right side: progressive, transparent, clean, unsullied by history. Watkin writes that, quite the opposite, collectivist modernism had a deep totalitarian streak. “The individual is losing significance,” Mies wrote in 1924, “his destiny is no longer what interests us.” Le Corbusier, that other great figure of modernism, likewise saw an impersonal future where houses would be machines for living in. “The denial of the role of the individual as a creative or significant force, and the belief that his role is that of a mere voice through which the great unconscious consensus of the age can be expressed, are ideas familiar in nineteenth- and twentieth century political philosophy,” Watkin writes. Of course, the early modernists were architects not philosophers, and like so many architects they were primarily interested in getting their own way, so much of the deterministic appeal to the zeitgeist was little more than ex post facto rationalization. But isn’t that always the way with architectural theory?

December 10, 2012

Cinematic Spaces

Roman Polanski and Lindisfarne Castle

Last week I re-watched Roman Polanski’s 1966 film Cul-de-Sac. Lionel Stander and Donald Pleasance are first-rate, but they share star billing with Lindisfarne Castle, which is the location of this one-setting film. Lindisfarne is a sixteenth-century castle that was restored and converted into a country retreat by Sir Edwin Lutyens, whose austere architecture contributes greatly to the tense atmosphere of the film. It reminded me how few movie director’s have exploited outstanding architecture. Joseph Losey set his version of Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1979) in and around Vicenza, and made full use of Palladio’s Villa Rotonda. Jean Luc Godard set Contempt (1963) almost entirely in Curzio Malaparte’s remarkable seaside villa in Capri. Country houses obviously play a big role in British costume dramas: Vanbrugh’s Castle Howard in the original Brideshead Revisted TV series, and Charles Barry’s Highclere Castle in Downton Abbey. But mostly, architecture is merely a walk-on. Hal Ashby gave Richard Morris Hunt’s Biltmore House a cameo role in Being There (1979), although he moved it from Asheville to the outskirts of Washington, D.C. Michelangelo Antonioni, who was trained as an architect, often used modern architecture to convey urban angst, never more than in Zabriskie Point (1970), in which he “blew up” a house designed by Paulo Soleri (in his Wrightian phase). And Stanley Kubrick staged the infamous home invasion scene in A Clockwork Orange (1971) in a coolly modern house designed by Richard Rogers and Norman Foster. Polanski made excellent use of architecture again in The Ghost Writer (2010). The beach house was entirely make-believe—an amalgam of an actual house on Germany’s North Sea coast with shooting sets—but it conveys the slightly spooky atmosphere of elegant, high-end minimalism to a tee.

December 9, 2012

Kahn’t Do It

A photograph by New York Times photographer Bruce Buck accompanies an article on the wonderful renovation of the Yale University Art Gallery. The gallery was built in three stages: a tall 1866 Ruskinian Gothic first phase by Peter Bonnett Wight (right); a 1928 Florentine Gothic horizontal portion by Egerton Swartwout; and a 1953 addition by Louis Kahn. What Buck’s photo clearly shows is the insensitivity of Kahn’s addition. It is not a question of style—Swartwout did not follow Wight’s lead either—but of massing. The Swartwout wing was rudely truncated by a brick party wall, and was obviously intended to be completed at some future date. Not only does Kahn not complete the work of his fellow architect, he insensitively pulls back to reveal the utilitarian party wall, leaving Swartwout with his metaphorical pants down. In addition, the cavity along Chapel Street does nothing to balance the composition, and only accentuates the difference between Kahn and Swartwout’s buildings—as it was presumably intended to do.

December 7, 2012

Speaking Ill

One should not speak ill of the dead, it is said. Yet in a week fill with encomiums for Dave Brubeck (1920-2012) and Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) it is hard to hold back. When I started listening to jazz, in the late 1950s, the Dave Brubeck Quartet was already famous—or at least as famous as jazz musicians got at that time. I loved Paul Desmond, and Joe Morello could do no wrong (I was a drummer), but I never warmed to Brubeck himself. Me and my friends much preferred Ahmad Jamal, Monk, and Bill Evans.

Nor was I ever an admirer of Oscar Niemeyer. His curvy, rather simplistic one-note architecture never appealed to me. Nor did his authoritarian ideas about city planning. Robert Hughes called the city of Brasilia“a Carioca parody of La Ville Radieuse.” And so it is, a dystopian parody, “an expensive and ugly testimony to the fact that, when men think in terms of abstract space rather than real place, of single rather than multiple meanings, and of political aspirations instead of human needs, they tend to produce miles of jerry-built nowhere.”

November 30, 2012

Simply Ike

The final review of Frank Gehry’s design for the Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, D.C., has been postponed yet again and the project seems more and more likely to be shelved. In a recent letter to Sen. Daniel Inouye, John S. D. Eisenhower, the President’s son, raises an issue that has nothing to do with the quality of Gehry’s design (which I have supported), nor with the over-wrought classical-modernist debate. Why couldn’t the memorial simply be “a green open space with a statue in the middle” he asks? Good question. Ever since the FDR Memorial spread over more than seven acres, memorial sponsors have felt the need to appropriate large sites, and then fill them up with water basins, fountains, figures, walls, and reams of quotations. The lackluster Korean War Memorial occupies over two acres, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial uses three acres, Martin Luther King Jr.’s overblown memorial sits on four acres, and the memorial to World War II consumes no less than seven. John Eisenhower’s suggestion of turning the four acres of the proposed Eisenhower memorial into a green square with a single statue of the President would reverse this trend. The challenge would be to find a modern sculptor who is up to the task of creating not merely a depiction of the president-general, but a work that captures his somewhat elusive mixture of modesty, shrewdness, and grit. The moving statue of Eleanor Roosevelt by Penelope Jencks in Riverside Park is one model. The memorial to Winston Churchill in Parliament Square in Westminster is another. Ivor Roberts-Jones’s bronze is twelve-feet tall and stands on a plain granite block inscribed with one word—CHURCHILL. The Eisenhower memorial could say simply IKE.

November 29, 2012

Image and Reality

Michelangelo Sabatino, who is researching the Canadian architect Arthur Erickson (1924-2009), recently sent me photographs that he had taken while visiting an early work by the architect. The 1959 Filberg house is in Comox, on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, and is particularly important since it launched Erickson on a stellar career that made him into Canada’s first internationally famous architect.

Sabatino’s photo (left) shows a rather, well, glitzy interior. Compare this view with what a professional architectural photographer does with the same interior (right). The angle is more interesting, the reflections are deeper, the forms balance each other; the room is still opulent, but no longer glitzy. In a forthcoming book, How Architecture Works, I compare architectural photography to portrait photography, whose purpose is to flatter the subject, to set it off to the greatest advantage, and to eliminate anything that detracts from this purpose. How often have we visited a building that we have previously seen exclusively in photographs, only to be disappointed, or at least surprised. Incidentally, the Filberg house may be an an example of Fifties taste, but that does not seem to have hurt its appeal, since it is listed for sale for six million dollars.

November 26, 2012

Game-Changer?

There are signs that after five years the housing industry is showing signs of recovery. The sixty-four-thousand-dollar question is what form the recovery will take. It all depends on who you listen to. Those who believe that economic recovery will be spear-headed by consumer spending, see us going back to business as usual, that is, expanding the homeownership rate, and building as many large houses as the market will allow. New Urbanists, on the other hand, see the recession as a wake-up call and foresee a return to denser communities. Others see the increase in rental housing as a harbinger of a new Age of Tenants. Advocates of small houses see, well, more small houses. The problem is that most of this is wishful thinking; the truth is that we don’t know whether the housing recession was a correction or a game-changer. My own guess is that Americans’ appetite for large single-family houses on their own lots will not diminish. At the same time, the willingness to take risks will be curtailed, and I would expect that ex-urban housing, far from city centers will be less attractive, in lieu of infill housing in established communities. A lot will depend on how quickly the economy recovers. If high unemployment and low wages drag on for another five years, that will mean that many young families will have been tenants for a full decade—that’s long enough to break the homeownership habit, especially if you can’t afford it anyway. But that’s only a guess.

Levittown, NY, 1948

November 17, 2012

On the Potomac

Last week I had the opportunity to sail on San Francisco Bay on the Potomac. The USS Potomac, built as the Coast Guard cutter Electra in 1934, two years later was commissioned as Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidential yacht. Roosevelt used it to sail up and own the Potomac until his death in 1945, when the ship was decommissioned. After being decommissioned, the Potomac had a checkered history. She was used as a ferry boat in the Caribbean, was briefly owned by Elvis Presley, was later used for drug smuggling and seized by the Customs Service, and finally ingloriously sank while at anchor at Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay. She is now owned by the Port of Oakland. The restored interior is much as FDR and his many guests, who included George VI and the future Queen Elizabeth, would have known it. The wheelchair-bound President had a rope-powered elevator installed that allowed him to pull himself up to the upper deck, and emerge through a door in the fake second funnel. What is touching is the unpretentiousness of it all; wicker chairs, a modest bunk in FDR’s cabin, and a broad settee in the stern where he could sprawl at presidential ease.

November 8, 2012

Real and Unreal

The French sculptor, Auguste Rodin, spent the last 24 years of his life living in La Villa de Brillants, his rather grand estate in Meudon, outside Paris. Rodin collected antiquities, and one of his largest possessions was a freestanding section of façade of a seventeenth-century chateau that he had disassembled and moved from nearby Issy-les-Moulineux to his garden. In the 1920s, when Paul Cret was designing a museum in downtown Philadelphia to house Jules E. Mastbaum’s collection of Rodin sculptures, he incorporated a replica of the chateau façade into his design. (Mastbaum, the developer of a chain of movie houses, knew Rodin and had visited Meudon.) The freestanding section of façade forms an entryway into the Rodin Museum grounds, and after crossing the garden, designed by Jacques Gréber, one arrives at the museum itself and a portico dominated by the splendid Gates of Hell. When I visited the recently renovated museum, it struck me that Cret and Mastbaum’s masterly strategy of using a replica to evoke the spirit of Rodin might have informed the design of the new Barnes Foundation, which stands next door. The memory of the old Barnes in suburban Merion, a building that also happened to be designed by Cret, might have been allowed to affect the design of the new Barnes, not only on the interior (as the law required) but also on the exterior. Instead, we have a fussily clad masonry box surmounted by an ungainly glass construction. But more on the New Barnes later.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers