Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 40

January 27, 2013

Nicknames

I was in Montreal recently and read in the local paper about the first Canadiens hockey game of the season, which was opened by Jean Beliveau (now 82). In his playing days, Beliveau was known as “Le Gros Bill,” after a popular 1949 French Canadian movie of the same name. Many top hockey players had nicknames: Maurice “Rocket” Richard, Bernard “Boom Boom” Geoffrion, Emile “Butch” Bouchard. The great Jacques Plante was “Jake the Snake.” Nicknames used to be popular. Actors had them, especially the old Western stars—George “Gabby” Hayes, Allan “Rocky” Lane, Alfred “Lash” LaRue, Edmund “Hoot” Gibson, Charles “Buck” Jones, and Woodward “Tex” Ritter, one of the many singing cowboys. Mainstream Hollywood stars used their full first names—Robert, John, James. Today shortened first names are common: Al Pacino, Johnnie Depp, Matt Damon, Tom Hanks. Are nicknames out of fashion? It would seem so. We haven’t had a president with a nickname since Ike, although we’ve had folksy Jimmy and Bill, and we almost had almost President Al. The last holdout for using nicknames is the Mafia: Andrew “Mush” Russo, Guiseppe “Pooch” Destefano, Joseph “Junior Lollipops” Carna. Some traditions never die.

January 18, 2013

Playing Games

University of Queensland architecture students, c.1960.

Architectural education differs from other creative fields: art students paint, ceramics students throw pots, film students film, but architecture students can’t build, they can only design. Nevertheless, ever since the Ecole des Beaux-Arts instituted the atelier system, the design studio has dominated architectural teaching. Never mind that this simulation of practice is actually very limited: there is no client, sometimes not even a site, programs are simplified, cost is rarely discussed, and construction is accorded a back seat. Moreover, design juries are generally composed exclusively of architects, rarely are engineers, developers, or lay people included. Little wonder that architects become accustomed to treating design as if it could be isolated from the outside world.

January 15, 2013

Nutt’s Folly

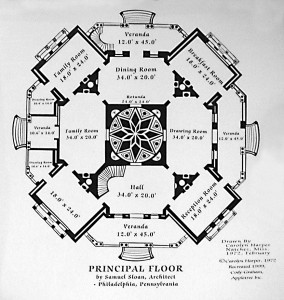

An architect friend reminded me of an extraordinary octagonal house in Natchez, Mississippi. Longwood was built just before the Civil War for Dr. Haller Nutt, a cotton planter, by the Philadelphia architect, Samuel Sloan. Construction was interrupted by the war (the Philadelphia craftsmen simply went home), and after Nutt’s death in 1864 construction stopped altogether. Although the brick shell was completed, only the lowest level was ever finished inside. Sloan’s plan is remarkable, since by the judicious placement of four verandas he manages to create two ranges of rooms. The central space is top lit by the onion-domed cupola, making this a distant cousin of Palladio’s Villa Rotonda, although the architecture is not classical but Byzantine-Moorish—or something.

January 5, 2013

Schooldays

An article in today’s New York Times on classroom chairs reminded me of my schooldays. As far as I remember, we had wooden desks with a built in bench seats, attached to the floor. The desk-top, usually carved with a chronicle of interesting graffiti, was sometimes hinged with a storage space beneath that we never used. We didn’t used the hole in the top, which was made to hold an ink-well, either. The desks were sturdy and not particularly comfortable—they weren’t intended to be. The Times piece is full of fluff about how different classroom chairs might improve learning, although the author allows that New York City’s Model 114 stacking chair has its defenders. “But is some quarters, the chair and others like it are seen as stubborn holdovers from before the age of ergonomics, when American schools’ main job was to turn out upright citizens, and rote learning was the student’s lot.” Since most people agree that American education has declined precipitously since the Age of Rote Learning, I wonder if a “stubborn holdover” is really so bad.

January 3, 2013

Roundhouses

I recently heard from owner-builder Marvin McConoughey of Corvalis, Oregon, who with his wife built their own house in the 1980s. I was impressed by their ambition (the house is about 2,500 sf), and by their dedication (it took six years). My wife and I spent three years building our own house—which I thought was seriously pushing the limits of both our sanity and our conjugal well-being.

Oh, and the McConoughey house is circular in plan! What is it about round houses that fascinates people? Inigo Jones designed several octagonal houses (although as far as we know he did not build any) and Jefferson built a famous octagonal house at Poplar Forest. McKim Mead & White designed a shingled round house in Jamestown, R.I. One version of Bucky Fuller’s Dymaxion House was hexagonal, another was circular, as were the D-I-Y yurts and dome houses of the 1960s. Today, circular houses are making a small comeback.

The power of the circle is apparent in a perfectly round space, as architects since Palladio have known. The best round buildings—the Pantheon, the British Museum Reading Room, the Guggenheim Museum—contain such spaces. The challenge of designing a circular house is that once the circle is subdivided into rooms it loses its special quality, and one ends up with awkward spaces that are either pie-shaped or segments of a circle. Wright understood that, which is why he never tried to squeeze a house into a circle, although he used circular shapes (see the Sol Friedman house, two intersecting circles, one subdivided, the other open).

Friedman House, Pleasantville, NY (1948)

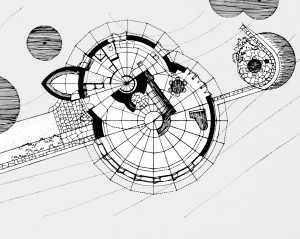

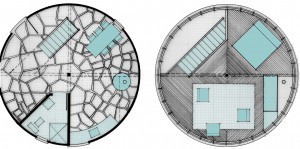

In 1967, I, too, had a go. Fresh out of school I designed a circular (20-foot diameter) summer cottage for my parents in Vermont. The solution was prompted by a nearby silo; I planned to use similar curved concrete silo blocks to build the walls. In fact, the two-storey house resembled a silo—or a lighthouse. The lower floor contained the dining area, kitchen, and bathroom, and the upper floor was one big room, with 360-degree views. I never quite figured out the roof—flat or peaked? By then I had realized that since my mother had had polio as a child, a house with a stair was a big mistake. Reluctantly I gave up on the silo and designed a house on one level. It had the shape of a sensible shoebox, and served my parents well for many years.

Ground Floor ……………………..First Floor

December 29, 2012

Castle is Home

Fonthill Castle, in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, is rarely included among the great country houses of the Gilded Age. This extraordinary house is not designed by an architect, it does not follow one of the accepted styles of the period, and it is just, well, too weird. I can’t think of an American country house that looks like a fortified manor house, not even San Simeon—the closest is Sir Edwin Lutyens’s Castle Drogo in Devon. Fonthill was designed and built between 1908 and 1912 by Henry Chapman Mercer. Like many country-house builders, he used reinforced concrete (cheap and fireproof), but unlike them he used it not only for the walls, but for everything: floors, beams, columns, arches, domes, vaults, roofing, window mullions, even built-in furniture—bookshelves, storage cabinets, and window seats are all concrete. He exploited the plasticity of the material and the result is a curious combination of Antonio Gaudí and the Addams Family. Like his contemporary Gaudí, Mercer (1856-1930) combined concrete with ceramics, made in his own Moravian Pottery and Tile Works (the factory, which resembles a medieval abbey, stands behind the castle). Mercer tiles, inspired by William Morris, were nationally distributed and enliven such buildings as Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Fenway Court and the state capitol in Harrisburg. An Arts and Crafts sensibility permeates Fonthill. The walls, floors and ceilings of the 44 rooms are adorned with tiles and mosaics, and contains his collection of pottery, books, prints, and curios. Well worth a visit; call ahead to confirm times.

Henry Mercer with Rollo

Mercer tile

December 26, 2012

LEED Lies

7 World Trade Center

Why are so many LEED-certified buildings all-glass? It seemed to defy logic. After all, no matter how much you can reduce artificial lighting by using daylight, the insulation value of glass is negligible compared to solid insulated walls, and anyway there are many overcast days and dark winter afternoons. It is even more puzzling when an all-glass building is shaded. First you wrap it in glass, and then you wrap the glass in something else. I always suspected that this was more about announcing “I am a green building” than about actually conserving energy. And now it’s official. A recent NYT article reported on the results of a New York City study of the actual energy performance of large office towers. (The full report is here.) In the rating system used, 75 is considered the minimum score for a building to be considered “high efficiency.” The all-glass 7 World Trade Center (LEED gold) scored 74, and the Condé Nast Building, highly touted as the city’s first green building when it opened in 1999 received an unspectacular 73. Close but no cigar. Solid buildings with windows, even old ones, do much better: the venerable Empire State scored 80, and Chrysler scored 84. As for the old glass towers, it’s downright embarrassing. The recently renovated Lever House reached only 20, and Seagram scored a miserable 3.

December 23, 2012

Seasons Greetings

Creche, December 1964 (WR, architect)

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to All!

Boiling Water

Every morning I boil water for making tea or coffee (I alternate). What starts my day is the most perfect kettle I have ever used. It is the work of Sori Yanagi (1915-2011), a Japanese product designer probably best remembered for his molded plywood Butterfly Stool. Yanagi studied architecture, but the kettle is decidedly not architectural—no purist Platonic forms, no postmodern irony, no gimmicky whistles. It is just a kettle: handle, spout, lid. Yet this perfectly balanced and shaped everyday object provides a feeling of well-being every time I use it—or even glance at it. In some ways, the deceptively simple kettle, half a million of which are sold annually in Japan, is a distillation of Yanagi’s design philosophy: he was 79 when he designed it.

December 21, 2012

Like Father, Like Son

In an idle moment, I made a list of celebrated architectural dynasties. There are many examples in the past, when knowledge was passed down informally from father to son:

Bartolomeo Sanmicheli and his brother Giovanni and his son Micheli

Andrea Palladio and his son Silla

François Mansart and his grandnephew Jules Hardouin-Mansart

Jacques V. Gabriel and his son Ange-Jacques

William Adam and his sons Robert and John

James Wyatt and his sons Benjamin Dean and Philip

Sir George Gilbert Scott and his son George Gilbert Jr. and his son Sir Giles Gilbert

Samuel Pepys Cockerell and his son Charles Robert and his son Frederick Pepys

Sir Charles Barry and his son Sir John

Benjamin Henry Latrobe and his son Henry

Richard Upjohn and his son Richard M. and his son Hobart

The practice has continued in modern times:

Frank Lloyd Wright and his sons John Lloyd and Lloyd

Eliel Saarinen and his son Eero

Albert Speer and his son Albert

Richard Neutra and his son Dion

Carlo Scarpa and his son Tobia

Emery Roth and his sons Julian and Richard

Edward Durrel Stone and his son Hicks

I.M. Pei and his sons Chien Chung and Li Chung

Cesar Pelli and his son Rafael

Quinlan Terry and his son Francis

Glenn Murcutt and his son Nick

Hugh Newell Jacobsen and his son Simon

It’s a surprisingly long list. Or, maybe, not surprising—growing up with an architect father must create a heightened sense of one’s surroundings. In some cases the father’s reputation dominates, in others the son’s. Robert Adam outshone his father, Henry Latrobe didn’t. In several cases—the Barrys, the Saarinens, the Scarpas—both generations achieved renown. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who designed the classic (and classical) British red telephone box, had a not-so-famous architect-father, and a very famous architect-grandfather. In quite a few of the modern cases, given current longevity, father and son work together (Pei, Pelli, Terry, Jacobsen). The name recognition helps, too, of course.

Didi and I. M. Pei, photo: Sacha Waldman

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers