Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 42

October 30, 2012

The Odd Couple

Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958) is the subject of a new book. We don’t associate Bel Geddes with iconic designs, as we do his contemporaries such as Walter Dorwin Teague (the Kodak Brownie), Raymond Loewy (the International Harvester tractor), Henry Dreyfuss (the classic Bell telephone handset), or Eliot Noyes (the IBM Selectric typewriter). Rather, Bel Geddes is best remembered for his visionary sci-fi designs, and for popularizing the streamlined style. He has been criticized for indiscriminately streamlining radios and refrigerators as well as buses and cars, although this does not seem any different than architects giving décor or chairs the Bauhaus—or the Baroque—treatment. Bel Geddes was famously responsible for the Futurama exhibit in the General Motors pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Less known is that one of the people who worked for him on the design of the building was a young Eero Saarinen. As Jeffrey L. Meikle points out in his interesting essay in the book, Bel Geddes’s extravagant brand of “commercial modernism” (as opposed to functional modernism) was an important influence on Saarinen’s later work. Another influence: Bel Geddes pioneered the public image of the high-profile designer that would become a later fixture in the architectural world. Saarinen learnt from that, too.

GM Pavilion, 1939 NY World's Fair

Mr. Streamlining

Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958) is the subject of a new book. We don’t think of Bel Geddes as the designer of an iconic product as are his contemporaries Walter Dorwin Teague (the Kodak Brownie), Raymond Loewy (the International Harvester tractor), Henry Dreyfuss (the classicBell telephone handset), or Eliot Noyes (the IBM Selectric typewriter). What Bel Geddes is best remembered for is bringing the streamlining style to a variety of consumer products. He has been criticized for indiscriminately streamlining radios as well as cars, although this does not seem any different than architects giving décor or chairs the Baroque—or the Bauhaus—look. Bel Geddes was famously responsible for the Futurama exhibit in the General Motors pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. One of the people who worked on that project was a young Eero Saarinen, and as Jeffrey L. Meikle points out in an interesting essay in the book, Bel Geddes’s extravagant brand of “commercial modernism” (as opposed to functional modernism), was an important influence on Saarinen’s later work. Indeed, it is a marked–if dubious–credit to Bel Geddes that he pioneered the public image of the high-profile designer that would become a later fixture in the architectural world. Enter the starchitect.

FC-400 Emerson Patriot Radio (1940-41)

October 18, 2012

Hand and Eye

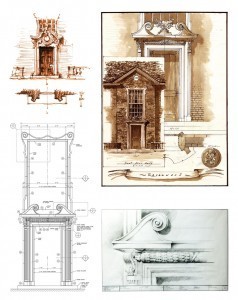

During a recent lecture, architect Richard Wilson Cameron talked about how he designed Ravenwood, an estate in Chester County, Pennsylvania belonging to the celebrated film director, M. Night Shyamalan. What turned into a five-year project involved transforming a rather nondescript Federal Revival house of the 1930s into a lovely Lutyenesque complex of buildings. The high quality of the craftsmanship, both inside and out, is impressive, but equally impressive is Cameron’s working method. According to the website of his firm, Atelier & Co., “We work closely with clients and draw every concept of our projects by hand—from initial sketches and renderings to fully developed design drawings. While we employ digital techniques in our work they are always secondary to our hand drawings.” During his talk, Cameron showed the development of the main entrance to Ravenwood: preliminary sketch, analytique, detail, and construction drawing. The finished product, with a raven sculpted by Foster Reeve, shows the happy result of this traditional working method. The free hand, guided by the eye, has served architects for more than two millennia. The shapes thus produced, whether they are traditional—as here—or modernist, have a distinctly humanist appeal that the machine cannot match.

October 12, 2012

Firms and Firms

I was recently asked by the chairman of a real estate company that manages a 4.5 million-square-foot portfolio of retail, office, and industrial properties, if I could recommend a firm to design of a new office complex. He wanted a cut above the run-of-the-mill. Running names through my head, I found that almost all of the architects that my Ivy League colleagues and their students admire, the academic A-list so to speak, lack the experience andthe staff to tackle a large commercial project. Their reputations are based on institutional rather than commercial projects, campus buildings, museums, and libraries, not on office buildings and shopping malls. While some condo developers did hire boutique firms to produce unusual designs during the last real estate boom, I’m not sure that’s what was required here. “I want my architect to have already made all his mistakes,” a developer friend once told me.

300 New Jersey Avenue, Washington, D.C.

Another alternative is the very large national firms that have branch offices all over the country, and the manpower to tackle any sort of project. Office size is not necessarily a deterrent to quality. A hundred years ago, the best large firms such as McKim, Mead & White, Warren & Wetmore, and Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, capably designed all sorts of buildings—residences, libraries, railroad stations, offices, apartments, and hotels. However, the current large firms resemble architectural widget factories, and can be counted on to produce work that is predictable, glib, and formulaic, without architectural character or conviction. It is unclear to me what is driving this situation. Do the developers demand banal design, or is that what their architects deliver? A spate of well-designed commercial buildings such as 300 New Jersey Avenue, a Washington,D.C. office complex (Rogers Stirk Harbour), the New York Times Building (Renzo Piano Building Workshop), and Tower 4 at the World Trade Center (Maki & Associates)—all designed by foreigners, by the way—suggest that it may be the latter.

October 9, 2012

Ask the People

Speaking recently at a British conference on urbanism, Daniel Libeskind called for a greater degree of public participation in the design process. “The people have to be empowered to be involved in shaping the program, not just the program but also the actual space,” he said. Let the voice of the people be heard! I was reminded of this tired nostrum as I was watching Seven Days in May. In a taped commentary, director John Frankenheimer several times emphasized that this excellent movie, shot in 1963, could not be made today (he died in 2004). Imagine, a political thriller without a shooting, a fight, or even a car chase! One of the differences in 1963 was the absence of preview screenings. Frankenheimer speculated that had the film been subjected to a test viewing, as almost all movies are today, someone would have complained about the long scenes and extended dialogue, or the complicate plot and the lack of action, and changes would have been ordered.

Fredric March (holding telephone), Edmond O'Brien and Martin Balsam in "Seven Days in May."

The architectural equivalents of the pre-release preview are the community boards, design review panels, and neighborhood oversight committees that “screen” new projects before they are built. It is virtually impossible to realize an urban building today without considerable input from the public. Sounds democratic, but the problem is that the The Public is often those who shout loudest and complain the most, well-meaning pressure groups, single-issue lobbies, and disgruntled individuals. It is hard to believe that more of this process, which tends to produce improvised compromises and mealy-mouthed consensus, would really raise the quality of the built environment.

October 3, 2012

The New-New Thing

The front page of today’s New York Times Arts section features two articles that sum up the state of architecture today. The newspaper’s music critic Anthony Tommasini reviews an inaugural performance in new concert hall in Sonoma State University, and Robin Pogrebin reports on Frank Gehry’s appointment to design an arts campus in Miami. The architect of the hall at Sonoma State is William Rawn, whose Seiji Ozawa Hall in Tanglewood has been acoustically rated as the fourth-best concert hall in the nation. Tommasini calls Weill Hall “a beautiful space” and the sound of the hall “rich, clear and true” (although the Times architecture critic chose not to weigh in on the design of the hall). In other words, the critique of Weill Hall is based on the building’s actual performance as a music venue. By contrast, the Miami story is about a building that has not yet been built, not even designed. Gehry is a remarkable architect, but does his mere selection by a client really qualify as news? The answer is yes, for in architecture today, the new-new thing rules. It’s true that architects have always been more interested in design than in reality, that’s why prizes are regularly awards to buildings before they are built, which is rather like rating a restaurant on the basis of its menu, without tasting the dishes. Similarly, unbuilt projects are critiqued in the media on the basis of a model or a sketch, while completed buildings are assessed after a “press day,” before they are actually put into use. But the time to evaluate a building is after years of use, when the rough edges have been worn smooth, and it is possible to judge the durability—aesthetically as well as physically—of the design. But, of course, that would not be news.

Weill Hall

September 30, 2012

Foxes and Hedgehogs

The philosopher Isaiah Berlin wrote a famous essay based on a saying attributed to the ancient Greek poet, Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” Berlin was referring to writers and thinkers—he characterized Plato, Nietzsche, and Proust as hedgehogs, Shakespeare, Goethe, and Pushkin as foxes. I was visiting Seattle this week, and two buildings almost side by side, the Seattle Public Library and the City Hall, reminded me that the metaphor holds true for architects as well. Rem Koolhaas and Joshua Prince-Ramus, the architects of the library, are definite hedgehogs; they have one big idea that they flog for all its worth. Glass, glass, glass. No details, no facades, no relation to the surroundings—the crystalline shape is awkwardly parachuted into steeply sloping site. Peter Bohlin, on the other hand, is a (sly) fox. Instead of a Big Idea, the building addresses its function, its site, its views, its materials, and its construction in many small—and not so small—ways. We have become so used to signature buildings that it is almost surprise to encounter a public building, especially a city hall, that is not trying to be an icon. Unlike the library, this building is neither puzzling nor confusing. Here are the offices, here’s the council chamber, here’s the entrance, here’s a place to sit and have lunch, and here’s how the whole thing is put together. The library is a prickly presence in the city; the city hall flits lightly through its urban surroundings.

September 22, 2012

Ask the Pigs

“If we want to understand the physical environment we should not ask architects about it,” writes Jonathan Meade in his new book, Museum Without Walls, (excerpted here). “After all, if we want to understand charcuterie we don’t seek the opinion of pigs.” Meades’s point is that the environment is much too valuable—and much too complex—to be entrusted to a single profession. Designing buildings is a perfectly respectable occupation, but architects want more, they want to create places. But places are created by their occupants over time, not by designers on paper, and most architectural attempts at place-making, such as megastructures, public housing projects, and planned communities, have run aground. I’m not sure when architects’ ambition expanded to encompass “the environment,” as opposed to buildings. Team Ten, which promoted an environmental view of building, met in Otterlo in 1959, which was the same year that the school of architecture at Berkeley was renamed the College of Environmental Design. Christopher Alexander’s Notes on the Synthesis of Form appeared in 1964. Moshe Safdie built Habitat in 1967. Habitat is a fine project, but only because the city of Montreal is next door—a city of Habitats would be unsupportable. Decades later, when Safdie master planned the new city of Modi’in inIsrael, he did not design the whole thing but made sure that many architects, developers, and builders were involved. The result is less perfect but more real.

Habitat, Montreal.

September 18, 2012

By the Numbers

World's first dual LEED Platinum building

I recently heard a talk by David Gottfried, the founder of the U.S. Green Building Council, which pioneered the LEED system for rating the greenness of buildings. Gottfried is no longer associated with USGBC and was promoting his latest project, a book titled Greening My Life which, as near as I could figure, was a rating system to score your personal happiness. There is something about numerical rating systems that appeals to Americans. We have GREs, SATs, LSATs, GMATs, Best College Rankings, teacher evaluations, Best Place to Live, opinion surveys, and political polls. This abiding belief in the power of numbers may have to do with living in a large heterogeneous country whose population no longer shares a common set of values. Or, perhaps it is an outgrowth of democracy itself, which is, after all, based on counting heads. No doubt, a fascination with numerical rating accounts for the widespread adoption of LEED. There are Silver, Gold and Platinum buildings, just like credit cards. Most people assume that a Platinum building performs better than a Silver building. Maybe it does, but LEED doesn’t actually score performance, as some other rating systems do, it scores design. You get so many points for having a bike rack, whether or not there are any bicycles in it. The puzzle is that so many LEED buildings are entirely glass, which seems counterintuitive. But that’s design by the numbers.

September 16, 2012

The Master Builders

I attended a meeting of the Design Futures Council ambitiously billed as a “Leadership Summit on Sustainability.” Present were engineers and representatives of the building materials industry (whose parent organizations were the chief sponsors of the event), but most of the participants were architects. The last group voiced a recurring theme. “It is important to think not only about buildings but about neighborhoods, and not only neighborhoods but cities, or preferably regions. Better still, the entire planet.” During the meeting, one architect voiced the opinion that architects could design anything. Oh, really? Architects are trained to design buildings. A few architects, like Eames and Saarinen, have designed great furniture, although that is the exception rather than the rule. And most architects are ill-equipped to function as city and regional planners, just look at the urban renewal fiascos of the 1960s. Designing buildings is a perfectly honorable profession, and if the buildings are functional and beautiful, the profession will be respected and listened to, as it was in the early 1900s. Sadly, that is not the case today. Although a few architects are almost household names, they are in the celebrity category, and their fame is as brittle and fleeting as that of Hollywood stars. As for the largest firms, which employ upward of a thousand people and have offices around the world, they are bigger but not better. None exerts the artistic and political clout of a Daniel Burnham or a Charles McKim. “Leadership” remains an elusive chimera.

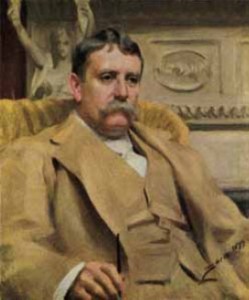

Daniel H. Burnham painted by Anders Zorn

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers