Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 44

July 22, 2012

City Limits

There are different arguments to be made about raising the height limit on buildings in the District of Columbia, but both Representative Darrell Issa and New York Times reporter Rebecca Berg are mistaken when they describe the original decision to set height limits as “arbitrary.” Before the Building Heights Act of 1899 was passed, Congress sent a commission to Europe to study height limits in cities such as London (80 feet), and Paris, Berlin, and Vienna (64 feet), and to also look at American cities, most of which had height limits (New York and Philadelphia were two exceptions). The commission settled on a height limit that followed a well-established urban design precedent, that is, the height of buildings should be related to the width of the street on which they stand. In Washington’s case, buildings on streets could be 90 feet high, while those on the broader avenues could be 110 feet. Hardly arbitrary.

July 15, 2012

Zigzag

Eyebrow Museum, NYC. Diller Scofidio + Renfro

I’ve always wondered where the continuous zigzag form came from (it has no name). Rem Koolhaas used something like it on the Educatorium, where a line suggested—improbably—that the roof and the floor were actually the same surface, just bent. Since then the ZZ Shape has proliferated, mostly on fashionable façades. Diller Scofidio + Renfro used it on the ICA in Boston, and in their proposed Eyebeam Museum in New York.

I came across the Ur-ZZ the other day. In 1923, Walter Gropius designed a pair of newspaper stands as part of his office redo in the WeimarBauhaus. Made of mahogany veneer on plywood, the stand is surprisingly formal for an avowed functionalist. The broad unencumbered surfaces sort of make sense for its use. But in a building it strikes me as an affectation that has no structural logic. But then, much recent architecture seems more like furniture than buildings.

July 9, 2012

Taken by Modernity

In 1971 I entered a competition for an addition to the British Houses of Parliament. My design blended Aalto with Le Corbusier—my two heroes. In hindsight, the large complicated project was far beyond my pay grade, but I was ambitious. Still, whatever in the world made me decide to do all the area calculations for the complicated building on an abacus? Cheap pocket calculators did not become popular until the mid 1970s, but still! I didn’t win the competition, but I still have the abacus. I remember the pleasant clickety-click of the wooden beads. I’ve never had such a fond memory of a pocket calculator.

Parliament House Competition, 1971.

I thought of my abacus when I read my friend Andres Duany’s recollections of student life at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris (in 1970-71). His essay is in Windsor Forum on Design Education. The writing is a witty, sardonic, perceptive (vintage Duany) take on architectural education. He describes the atelier, where shared drafting tables were regularly dismantled and assembled as needed.

“Needless to say there were no attached parallel rulers, only T-squares. Remember the thrill of walking around the streets carrying that incredibly charismatic instrument! And the pleasure of the visceral click as the T-square was snapped into orthogonal alignment before every line was drawn. And twirling and slapping down triangle and scale. And the ritual of systematic dismantling and cleaning the Rapidograph ink pens before final drawings, like soldiers checking their equipment before the assault. How much more satisfying than the effeminate typing on a keyboard, the sleazy sliding of the mouse followed by the infantile, gurgling and cooing of the computer! Forgive the nostalgia, but I am gripped by what has been taken from us by modernity!”

Amen.

July 4, 2012

Potemkin Village

This is the definitely the year of the Chinese architect. Wang Shu wins the Pritzker Prize, the dissident Ai Weiwei’s takes part in the design with Herzog & de Meuron of this year’s Serpentine Pavilion (which Paul Goldberger tweeted is “thoughtful, pleasant, hardly anyone’s greatest moment”), and now the British magazine, Architectural Review, presents its 2012 House Award to John Lin, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong and a principal in the firm Rural Urban Framework. The house is surrounded by a perforated brick screen. Behind the screen, four courtyards accommodate family activities, animals, and a biogas digester. The magazine press release calls it “a modern prototype of this traditional locus of rural life.” Well, it’s certainly uncompromisingly modern, but I worry that it looks so neat and designy. Trying to imagine it with muddy pigs.

June 30, 2012

Raising the Bar

1700 NY Avenue, SmithGroup, architects.

An old student of mine who recently opened his own office in Washington, D.C. asked me why I thought the new homegrown architecture of that city was, to put it kindly, uninspired. After serving eight years on the Commission of Fine Arts I’ve seen a lot of projects. Apart from a few buildings by outsiders (Richard Rogers, Bing Thom, David Adjaye) most of the work has been pedestrian, architecturally unambitious, and lacking any real critical thought, that is, intellectually mushy. Without constructive and challenging criticism—which can only come from colleagues, not from critics or clients—practitioners easily get lazy. While there is an enviable amount of construction in DC—federal, municipal, and private—there really isn’t much of an architecture scene, I mean the sort of things that made the Bay Area exciting in the 1950s and 1960s, Philadelphia in the 1970s and 1980s, or LA today. What is needed to make a city a creative hot-bed? The availability of work, of course; a major local figure (a Wurster, a Kahn, a Gehry) helps to attract young architects, train them, and raises the local bar; and a thriving local school of architecture (Berkeley, Penn, SciArc) will reinvigorate office staffs, give part-time employment to fledgling architects, but especially will encourage critical dialogue. But these are conditions, not causes, and the actual chemistry that produces a creative architecture scene is somewhat mysterious. New York and Boston have one, neither San Francisco nor Philadelphia do anymore. Chicago may get one (again), and I would keep my eye on Vancouver, British Columbia, maybe Montreal. Washington, not so much.

June 25, 2012

Two Cultures

During my nineteen years at Penn I have served as a faculty member in two departments, architecture in the School of Design, and real estate in the Wharton School. I discovered many small differences: the real estate faculty is more social, with a Christmas party and an end of year barbecue; architects are less punctual and more long-winded than economists; the business school has better box lunches at faculty meetings. But what struck me most was the differences in academic cultures.

Medical schools do medical research, business schools advance the theoretical state of the art, but architecture schools don’t produce architecture—except on paper, and that work is done almost entirely by students. The design studios are the heart of the program, and the exhibition of student work is a highlight of the academic year. Like most programs, Penn’s department also produces an annual catalog of student work, but one cannot imagine an annual real estate publication devoted to student course assignments. In the real estate department, although all the faculty teach large lecture courses and teaching is what “pays the rent” for the department, the emphasis is on faculty research. Many faculty do all their teaching in one semester, in order to have the second free for their own work.

It is not that the real estate department doesn’t pay attention to teaching, quite the opposite. Attendance is more firmly enforced, assignments are more demanding, and grading is stricter than in architecture, at least in my experience. US News and World Report, which is basically a student consumer guide to university programs, regularly rates Wharton as one of the best B-schools in the country. How do they teach? Real estate faculty teach the same courses, year-in and year-out, refining and updating but not drastically altering the content. The content of architecture design studios, on the other hand, changes from year to year. Who teaches? The real estate department makes minimum use of adjunct teachers, considering them unreliable amateurs. By contrast, in architecture programs there is a long tradition, dating back to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, of practitioners teaching on a part-time basis. In the Penn architecture department, for example, scores of adjuncts and lecturers far outnumber the dozen or so standing faculty.

Architecture curricula are in a constant state of flux, influenced by changing fashions, and torn between the profession’s demands for new skills, and emerging scholarly theories. It would be easy to say that the real estate curriculum is more focused. But the narrow aim of B-schools is to expose students to course content—theories and methods. The goal of a design school is to teach creativity, which is an elusive goal. Especially as talent, rather than merely hard-work, is the key variable—and talent is always in short supply.

June 15, 2012

Pecking Order

Every year a ranking of schools of architecture comes out, most recently compiled by Design Intelligence. A couple of years ago, I decided to do an unscientific ranking of my own, not based on what architecture deans think, or who employers are hiring, or the current enrollment statistics, but on the long-term product, that is, which schools produce the largest number of really outstanding architects. I compiled a list of the “best” living architects by starting with Priztker Prize winners, AIA Gold Medal recipients, Driehaus Prize winners, and then adding as many names of first-rank prominent practitioners (not academics) as I could think of. I ended up with 55 names. The results? A smattering of regional schools has one or two names, an outstanding alumni such as Steven Holl (Washington), Peter Bohlin (Carnegie Melon), or Michael Graves (Cincinnati). The top four ranks are occupied by (predictably) mostly the Ivy League. Cornell, Princeton, MIT and IIT have 5 percent of the list each; Penn, Columbia and Berkeley have 7 percent each; and mighty Harvard has 10 percent. The surprising result is that fully 40 percent of the names on my list are Yale grads. That is, as scientists say, statistically significant.

June 7, 2012

Anything Goes

I’m starting to sympathize with Guy de Maupassant, who hated the Eiffel Tower so much that he is said to have regularly had dinner in its restaurant to avoid looking at it. I’m not talking about the Eiffel Tower, of course, but the Orbit Tower, erected on the occasion of the London Olympics. Anish Kapoor and Cecil Balmond’s design surely represents the nadir of twenty-first century architecture, structurally feckless (at least to my eye), needlessly complicated, and downright ugly. It puts me in mind of the tower that appeared for the 1976 Montreal Olympics. Its ostensible function was to support the retractable stadium roof, but its actual purpose was to satisfy Mayor Jean Drapeau’s desire for a vertical icon. The tower was unsuccessful, both technically (the roof never worked), and iconically. Mayor Boris Johnson says that the Orbit Tower is “definitely an artwork.” Well, it’s definitely a something.

May 29, 2012

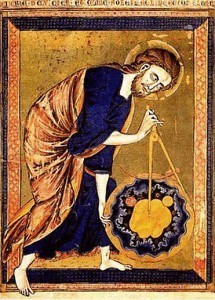

Precedent and Theory

Architecture, like common law, is based on precedents rather than theories. Great buildings are always, to some extent mysteries, and they must be experienced first-hand if their greatness is to be understood. That is why architects have always travelled in order to examine, measure, sketch, and photograph, in an attempt to plumb the mystery. So it would come as a surprise to most people to discover that almost all schools of architecture teach something called architectural theory. Or, at least, their curricula include courses that bear that name. Since the 1990s, these courses have by and large replaced the comprehensive study of history, which for so long formed the scholarly backbone of architectural education. Since theoretical treatises in architecture are few and far between, and the connection between them and practice is tenuous at best, courses in so-called history-theory tend to rely heavily on philosophy and cultural studies. This has little to do with the pragmatic and messy field of the building arts, as young graduates soon discover. Those who want to be architects will find that the pencil and the sketchbook are more potent tools when it comes to unraveling the secrets of the great buildings of the past.

Ronchamp, 1964

May 19, 2012

Culture Gulch

The opening of the new Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia has caused some locals to tout the creation of a “museum mile” along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, with the Philadelphia Museum of Art at one end, the Franklin Institute at the other, and the Barnes and the Rodin Museum in-between. Ever since the City Beautiful movement proposed creating grand civic centers, the idea of clustering urban functions has gained traction. But it only makes sense in selective cases. Grouping theaters, which tend to be open at night, supports pre- and post theater restaurants (as in Broadway and the West End); grouping stores allows shoppers to do errands conveniently. Certain commercial activities—garment-making, finance, commercial art galleries, antique shops—gain by proximity. But there is no reason to group religious buildings, for example, or sports venues. Or museums. Nobody spends two hours in a museum and says, “Let’s go next door for another two hours.” Large buildings such as museums and concert halls may be located on important avenues, but that is done for urban design not functional reasons. The only seeming advantage to grouping museums is for the tourist, who doesn’t know the city. But judging from those paramount tourist destinations, London, Paris, and Rome, even tourists enjoy exploring.

Benjamin Franklin Parkway, 1928

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers