Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 43

September 11, 2012

Portlandia

Dateline: Portland, Oregon. This city is an odd mixture of urbanity and provincialism. A walkable downtown with light rail but with more backpacks than attaché cases—that’s not so odd, but people carrying sleeping bags on the street is. Everybody waits for the traffic lights to change—that appeals to the orderly Canadian part of my soul. Cities are about obeying rules in order to live together. Portlandisn’t exactly Manhattan, but I like it. Perhaps this is the new “urban-light living” that a recent article in the Atlantic talked about.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth century buildings are derivative—this could be Buffalo or Rochester—and equally sophisticated. The current crop of office buildings is no less derivative but done with considerably less conviction. A little of this, a little of that. Graves’s Portlandia Building is getting a bit frayed (although Ray Kaskey’s statue looks as good as the first time I saw it, years ago), and so is the Equitable Building, designed by Graves’s nemesis, Pietro Belluschi (the first real modernist office building in the US). But compared to the current generation of hacks, Belluschi and Graves were at least trying to make a coherent statement. I look for Filson’s, but it’s moved to a new location; L.L. Bean has just moved away, period. John Helmer Haberdasher is still there. I must have bought my first hat from this shop 30 years ago. I buy an Italian linen cap, for old times sake.

September 10, 2012

State Caps

American state capitol buildings are traditionally a smaller version of the U.S. Capitol, complete with central dome; you can find them in Montpelier, Harrisburg, Little Rock, and Salt Lake City. The state capitol in Lincoln, Nebraska is different. There is a small gold dome, but it’s on top of a fifteen-storey office tower. The architect was Bertrand Grosvenor Goodhue. He won a 1920 national competition against formidable competition; second and third places were was taken by John Russell Pope and McKim, Mead & White, who both designed classical schemes with the familiar domes. The fourth-place finisher was Paul Cret who dispensed with the dome and proposed a low, building in a simplified classical style, the centerpiece crowned by sculpted buffaloes. Goodhue’s design was even more radical: a free interpretation of classicism that dispensed with columns and entablatures and blended classicism with a Gothic sensibility (Goodhue had designed many Gothic Revival buildings with his then-partner Ralph Adams Cram). The Nebraska building is not a stylistic pastiche, however, more like a modern riff on old themes. The modernity is underscored by the artistic elements in the building, many on prairie themes (including “The Sower” that stands atop the dome), the work of sculptor Lee Lawrie. This was a moment in American architecture when art and architecture happily complemented each other (see Rockefeller Center, where Lawrie also worked, for another example). It was also a moment when architects such as Goodhue and Cret were pushing the boundaries of traditional styles to discover a modern, American version. This remains another one of those “roads not taken,” as European modernism swept the scene, and such stylistic exploration—and artist-architect collaborations—became a thing of the past.

September 3, 2012

Getyourshittogether

And now for something completely different.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has turned its sights on a new global problem: sanitation. The foundation has committed $3 million to support research that has as its goal to “reinvent the toilet as a stand-alone unit without piped-in water, a sewer connection, or outside electricity—all for less than 5 cents a day.” “Reinvent the toilet” outré, but it isn’t. Children playing around a sparkling water pump are more photogenic than a well-functioning toilet, but inadequately treated human waste is the source of most water-transmitted diseases. And since running water supply is in short supply in third world countries, never mind adequate sewage treatment, the conventional flush toilet is not an option—a waterless toilet makes sense.

I don’t know what the Gates project will come up with, but I would be surprised if composting wasn’t a part of the solution. A typical adult excretes about half a pound of feces daily and between one and two quarts of urine, and since composting requires dry conditions, getting rid of the liquid is a problem. Most composting toilets use some combination of heat and induced ventilation.

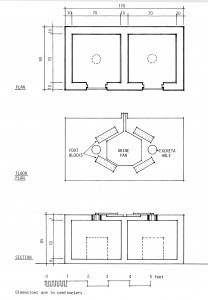

An ingenious composting toilet, the Gopuri, designed by Appasheb Patwardan in India in the 1940s, takes advantage of a special characteristic of human excreta: feces transmit pathogens, but urine is sterile. The Gopuri separates solid and liquid waste, which occurs naturally in a squatting position. A handful of ashes is sprinkled over the waste after each use. The toilet consists of two vaults. When one is full, it is sealed up, and the adjoining vault is emptied and put into use. The contents decompose anaerobically; the holding period is typically 3-6 months. The urine is disposed of immediately; the compost is used in agriculture. Thousands of Gopuri toilets were installed in the state of Maharashtra. A version of the Gopuri is reported to have been used with success in North Vietnam in the 1960s. There have been demonstration projects in a number of countries.

Stop the Five Gallon Flush, the classic 1973 guide from McGill University’s Minimum Cost Housing Group, featured in the Whole Earth Catalog, describes 80 alternative sanitation systems, including the Gopuri, and is available free online.

August 28, 2012

Style Wars

In the Traditional Architecture chat room, there has recently been a call for a “war” between traditionalists and modernists. While this sounds rousing, I believe it widely misses the mark.

For one thing, it creates a straw man called The Modernist. As if you could really lump Thom Mayne, Renzo Piano, Peter Bohlin and Moshe Safdie together. Modernism is as internally riven as the Republican party. The Koolhaas-Hadid-Libeskind fringe receives media attention, but many of the big serious jobs go to the Piano-Foster-Rogers faction. The Centre Pompidou was seen as the swan song of so-called high-tech design, in fact it was the beginning of a style that has come to dominate a variety of building types: airports, museums, office towers. There is also a reaction within modernism to the excesses of Koolhaas and company in the form of much more “traditional” and dare I say intelligent wing that includes Peter Bohlin, Bill Rawn, and Jack Diamond. They often pick up the pieces after their glamorous colleagues. For example, Diamond is completing a ballet-opera house, the Mariinsky II, after two failed competition entries, the first by Eric Owen Moss, the second by Dominique Perrault failed to produce a satisfactory result.

I do not include Frank Gehry. He is sui generis, more a Gaudi figure than a Le Corbusier let alone a Mies. He should be valued, but not imitated. Incidentally, I have seen the model of the proposed Facebook headquarters, and it’s hardly Gehryesque, nor iconic (and actually much more appealing than Foster’s donut for Apple).

Some years ago, I think in 2002, I participated in an Institute for Classical Architecture symposium. I remember Robert A. M. Stern chastising the audience. It’s not enough to design expensive houses, he said, if classicism is to survive it has to expand into public buildings. Well, in the intervening decade, Stern, David Schwarz, Allan Greenberg, and Tom Beeby have done exactly that. There have been traditional public libraries, concert halls, and courthouses, as well as campus buildings, apartment buildings, and soon, a presidential library. I say “traditional” rather than classical for all these designers are eclectics. That is a strong card to play with clients, as John Russell Pope, Charles A. Platt, Paul Cret, Bertram Goodhue, and Ralph Adams Cram all understood.

It is clients, not competing architects, who are the key to a style’s survival. It is true that at the margins, politicking and intrigue play a role, but ultimately, it is clients not architects who decide what to build. Or not to build. That is why Frank Furness’s career foundered, as did Paul Rudolph’s, and why Louis Kahn’s rather ascetic architecture found few takers. If people like it, they will ask for it (that’s why Venetian Gothic lasted well into the Renaissance—the Venetians simply liked it). As for that old bugaboo—“educating the public”—it didn’t work for the modernists and it is unlikely to work for the classicists.

The modern American public has grown to expect a range of choices in food, dress, entertainment, culture, and so on. So why should architecture be exempt? I don’t see a world where classicism replaces modernism, even less where modernism conveniently disappears. “You cannot not know history” said Philip Johnson. He was reminding modernists that the past matters. But the immediate modernist past matters too. There are still lessons to be learned from Aalto, Mies, and Kahn, and an architect—any architect—would be foolish to ignore them. What I do see is an uneasy (at least for architects) coexistence. This is not a call for complacency, but neither is it a reason for pie-in-the-sky appeals to battle.

Sorry to be long-winded. I am finishing a book on this subject so it’s uppermost in my mind.

August 23, 2012

Kahn Without Kahn

The FDR Memorial on Roosevelt Island is nearing completion. I am of two minds about this undertaking, which is based on the design that Louis Kahn was working on when he died in March 1974. It was, literally, his last project. There are so precious few Kahn works, that who could object to one more? But as David De Long, who co-curated the major 1991 exhibition on Kahn observes, “Posthumous realizations are always very, very risky.” They are particularly risky in the case of Kahn, who was famous for making last-minute changes, often after construction had started—to the consternation of his office staff, not to mention clients. So although the current project is based on construction drawings that had been prepared by Kahn’s office, these should not necessarily be considered as definitive. Even great artists have second thoughts. When Henry Bacon and Daniel Chester French were working on the Lincoln Memorial, and the building was largely completed, they had a plaster replica of the projected statue erected inside the building to study its scale, and decided it was too small and needed to be enlarged. The bronze head of the President recently installed in the FDR Memorial looks to me as if it were trapped in a vice. Who is to say that Kahn would not have refined the memorial design, in small ways and large, had he been alive to do so? We will never know.

August 20, 2012

The Royal Business

My friend Marc Appleton recently recommended a book by Royal Barry Wills. Wills (1895-1962), a Massachusetts native, was an architect (though his MIT degree was in engineering) who in the 1930s popularized the Cape Cod cottage and was a well-known residential designer. In 1938, LIFE magazine invited several architects to design modern and traditional houses; actual families would then chose one to build. Wills prevailed over no less than Frank Lloyd Wright. Wills’s book is the long out-of-print This Business of Architecture, originally published in 1941. It contains chapters titled “Stalking and Capturing of Clients” and “Design Within the Owner’s Budget.” The book is illustrated with Wills’s delightful drawings, and the tone is sensible, down-to-earth, and slightly sardonic. More than seventy years old, the book still rewards close reading and I would recommend it to any budding practitioner. Incidentally, Wills practiced what he preached; his firm, established in 1925, is still in business.

Cape Cod Cottage, design and photo by Royal Barry Wills

August 16, 2012

The Rude Building

From the Plus Ca Change Desk.

Have people read A. Trystan Edwards? He was suggested to me by Marc Appleton. Edwards (1884-1973) was a Welsh architect and town planner who studied at Liverpool, and articled under Sir Reginald Bloomfield. In 1924 he published an extraordinary book, Good and Bad Manners in Architecture that discusses many of the issues currently raised by the current New Urbanism movement. You can get an idea of the book from the frontis page: “This book asks the novel question, How do buildings behave towards one another? It contrasts the selfish building, the presumptuous building and the rude building with the POLITE and SOCIABLE building; and it invites the public to act as arbiter upon their conflicting claims.” The “rude building” is very good. There should be an annual prize for the Rude Building of the Year. Edwards also wrote Architectural Style, which is likewise worth reading. Both are out of print, so either a good library or AbeBooks.

Skirkanich Hall, University of Pennsylvania (Williams & Tsien, architects)

August 5, 2012

The Taxi Index

There are so many indices for measuring urban success: creative jobs, crime rates, pollution, walkability, education levels, happiness quotients. I would another. Returning to Philadelphia from a trip last week I took a taxi. I sat in a beat-up car, squashed into the back seat by a crudely made security barrier plastered with scratched up decals, no air-conditioning, and to add insult to injury, the reckless driver didn’t even know the city. I had just come from LA where all the taxis I took were new Prius’s, picked me up on time, and the drivers seemed to know there way around. New York taxis are pretty good, especially the minivans, and they have useful video screens. The city will soon be getting a new Nissan taxi. OK, it’s not as good as the late lamented Checker, but it’s something. Of course the gold standard for taxis is the London black cab, well-designed, diesel-powered, roomy (it can carry 6-7 people), and driven by knowledgeable navigators. And London is a pretty successful city, too.

Proposed Nissan NYC taxi

July 28, 2012

Round and Round

Villa, Nablus. Photo: Yuri Virovets.

Palladio’s Villa Rotonda has provided inspiration for architects over the ages, starting with Vincenzo Scamozzi, Palladio’s student who completed the Villa Rotonda after his master’s death. Scamozzi built La Rocca, a hilltop villa in nearby Lonigo. Inigo Jones designed several bi-axial houses, but never found a client. In the eighteenth century, there were at least four British Rotondas, the most celebrated being Lord Burlington’s Chiswick House. There are a number of more recent examples; I have seen a house inspired by Rotonda on the outskirts of Pittsburgh, designed by Alvin Holm, and there is a small version, the Henbury Rotonda, by Julian Bicknell, in Cheshire, England. Although neither is more faithful to the original than the replica built in Nablus, on the West Bank. The house is said to belong to a Palestinian arms dealer, a weird parallel to the “Palladian palace” on a Caribbean island belonging to Onslow Roper, a fictional arms dealer in John Le Carre’s The Night Manager.

July 26, 2012

Crying Wolf

I visited a house by a famous architect (he’s a friend, so let’s just call him The Architect). The house was beautiful, thoughtfully designed and exquisitely executed. Very low key, suiting its rural site. Minimalist, in a luxurious sort of way. And big. The occupants were a retired couple, with grown-up children long since moved away, but their home was the size of a small primary school. The main corridor was a hundred and fifty feet long, and the house didn’t end here, there were still garages and outbuildings.

There have been wonderful houses in the past, even the recent past, but most of the ones I see today feel over-done. Too much money thrown at too simple a problem. I can still get weak-kneed over the Maison de Verre, Fallingwater, or a Palladio villa, but most modern houses feel like a Wolf cooking stove; impressive, perfectly detailed, obviously expensive, but it’s still just a stove.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers