Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 39

March 4, 2013

Urban Topos

Vancouver, BC

There are many ways to measure cities: population, unemployment, crime rates, pollution, literacy rates, and so on. Aesthetics is harder to quantify, and so it is easier to ignore, yet beauty is also an important urban variable. Beauty in the manmade environment takes the form of streets, squares, and buildings, so it is tempting for cities to seek improvements in the urban equivalent of facelifts and makeovers: new boulevards, parks, civic monuments. But there is a type of urban beauty that is harder to improve: the natural setting. Cities on islands (New York, Stockholm) have a sort of self-contained magic. Cities with hills (Montreal, Rome) feel as if they are tied to something elemental. Rivers used to be an indispensible attribute for a thriving city, but today they are purely an amenity. A city with an attractive river (Paris, London, Prague)—not too large and not too small—gains not only river walks. Crossing a bridge in a city feels like a temporary natural reprieve. That’s why lovers meet on bridges. The presence of water is always nice, even when its manmade (Venice, St. Petersburg) but not all water is created equal; there is nothing like the view of a beautiful bay (San Francisco, Rio de Janeiro) to spice up the urban scene. Views of majestic mountains (Seattle, Vancouver) are almost as good—plus they mean nearby skiing and hiking. There are inland cities on flat sites without charming rivers or mountain views (Houston, Beijing, New Delhi) that have overcome the lack of a beautiful setting. But the cities with beautiful natural settings will always have a leg up.

March 1, 2013

Leaky Jim

In a history of postmodernism (history written on the fly since the book was published in 1984) Heinrich Klotz wrote: “James Stirling has received only one commission in his own country since he made his change to postmodernism, yet what stands in the way of postmodernism in Great Britain is not so much a lack of commissions as a continuing faith in modernism.” As evidence, Klotz cited the successes of Norman Foster, Ove Arup, and Richard Rogers. The persistence of modernism in Britain in the eighties was undoubted, but Stirling’s lack of commissions was due to something else. The trio of red-brick university buildings that launched his career—the University of Leicester Engineering Building, the History Faculty and Library at Cambridge, and the residential Florey Building at Queen’s College, Oxford, were aesthetic successes but rather spectacular technical failures. The glass roofs leaked, both in the engineering building and the library (!), and the heavily glazed spaces were impossibly cold in the winter. In an AD profile of the Florey Building, an ex-resident reminisced about his student days: “The Florey Building was an unmitigated disaster to live in. The arrangement of rooms meant that privacy was only achievable by drawing down blinds, and the aluminum strips connecting windows to walls conducted sound so that one could easily hear conversations in the next room.” Indeed, Florey had so many problems that the university brought a law suit against Stirling’s firm. According to AD, “As a result, Stirling’s office was unable to find work in England for at least a decade after the Florey building, instead finding promise of work in places like Germany, Japan, and the Unites States.”

Florey Building

February 26, 2013

An Age of Anxiety

Every evening I watch the evening news. News may not be exactly the right word. The reports are a combination of speculation about what is about to happen—a presidential speech, a new pope, the Oscars—and spokespeople touting one point of view or another on the issue of the day. Which today is sequestration, or rather “what Washington refers to a sequestration,” as the media insists on calling it, despite the fact that by now it is a term surely familiar to all. But perhaps the most common “news” story is the revelation of a new topic of concern: a previously ignored disease, an unnoticed social condition, an overlooked environmental effect, a looming problem. Journalistic careers are made by discovering the next new trouble: on-line privacy, bullying, school soccer injuries, whatever. Since the evening news insists on being upbeat, however dire the issue, it can always be fixed, we are told by the earnest experts. Just once, it would be refreshing to hear that a problem was insoluble. “Sorry, nothing can be done about it. It’s just human nature. We’ll have to learn to live with it.”

February 17, 2013

Secret History

If I were compiling a secret history of architecture—those unpedigreed works of genius that stand outside the mainstream—I would include Gaudí, of course, but also many lesser figures: Henry Chapman Mercer, the builder of several amazing concrete structures in Doylestown, Pennsylvania; Paul Chalfin, the creative force behind that ebullient Baroque pile, Vizcaya, in Miami; and Simon Rodia, creator of Watts Towers in LA. I would also have to add my friend, George Holt in Charleston, whose Byzantine concoctions have no contemporary analog. There would also be a number of women in this company: Theodate Pope whose Avon Old Farms School anticipate Hobbits; Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, who designed the wonderful stone structures that grace the rim of the Grand Canyon; and Sarah Losh, the subject of a new biography by Jenny Unglow. Losh (1786-1853) built little—a country church, a schoolhouse and a sexton’s cottage—but what she did build is exceptional, and exceptionally original. The small church of St. Mary’s in the village of Wreay in the Cumbrian hills, where she lived, anticipates the Romanesque revival, but also includes personal decoration that has no historical antecedents: column capitals in the form of lotus buds; gargoyles in the form of winged turtles; a baptismal font carved (by Losh herself) with floral patterns; and a profusion of pinecones. Quite wonderful

St. Mary’s, Wreay

Baptismal Font

February 11, 2013

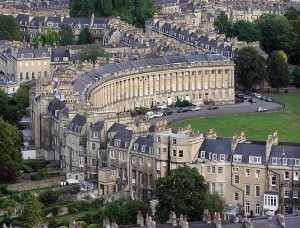

Bath Houses

Ever since I first saw it years ago, I’ve admired the Royal Crescent in Bath. Designed and built by John Wood the Younger in the eighteenth century, it is an early example of real estate development informed by smart architectural design. What is remarkable about this housing terrace is that behind the great Palladian façade, which consists of a giant order of Ionic columns atop a rusticated base, are thirty individual houses. It worked like this. Wood and his partner bought the greenfield (literally, it was an undeveloped field) site from the Garrard family, and subdivided it into 30 lots. The largest houses were to be at each end, and in the center. They sold the lots house by house, starting at one end and working their way to the other. When a lot was sold, Wood was responsible for the construction of the front façade, while the homeowner’s architect designed the house behind it according to his client’s instructions. From Wood’s perspective, it was pay as you go, as he minimized his financial exposure. The first lot was sold in 1767; it took 3 years to reach the midpoint of the crescent. Sales must have slowed down, since the project was not completed until 1775. Royal Crescent was the third Bath real estate development by Wood father and son; the first, started by John Wood the Elder, also an architect/developer, is Queen Square, the second is the Circus. Even then, developers recognized the value of a prestigious name.

February 10, 2013

Mike’s Place

Bloomberg Place is a commercial development under construction in central London. The two wedged-shaped office buildings, linked by sky bridges, are designed by Foster + Partners, which is also responsible for the lumpy building next door. What is interesting about Bloomberg Place is its height: ten stories, since this part of the city has a fifty-meter height limit. Washingtonians, currently engaged in a debate over raising the long-time height limit in that city should take note.

February 6, 2013

Plus ca change

The British architect for this amazingly insensitive addition is called Bureau de Change. Need one say more?

February 5, 2013

The Fourth Man

A recent documentary film on the Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953), Incessant Visions, is a reminder of how history has treated the great architect: not well. He is best rememberd today for the idiosyncratic Einstein Tower in Potsdam, and for a series of expressionistic sketches that he drew while a soldier on the Russian front during the First World War. Yet he was by far the most productive—and the most technologically inventive—of the early modern pioneers (he was born the same year as Le Corbusier), building department stores, factories, and a cinema. If his early work is not better known, it is because much of it was destroyed during the Second World War (and in postwar reconstruction), and surviving buildings in East German, Poland, and the Soviet Union were long rendered inaccessible by the Iron Curtain. Moreover, since his architecture didn’t fit the narrow confines of the International Style, historian/propagandists such as Sigfried Giedion, wrote him out of the history of the modem movement. Yet he belongs in the first ranks of the heroic age of the modern movement, alongside Mies, Corbu, and Gropius. The German phase of Mendelsohn’s career was cut short in 1933 when he fled the Nazis’ persecution of Jews. He subsequently settled in Britain (where he built two striking buildings with Serge Chermayeff), moved on to Palestine, where he built a house for Chaim Weitzmann and hospitals in Haifa and Jerusalem, and spent the last ten years of his life in San Francisco, teaching at Berkeley, and building. Always building.

Petersdorff Department Store, Wroclaw, 1928

February 4, 2013

Architect Laureate

The United States has had a poet laureate since 1937. Why don’t we have an architect laureate? An architect laureate could be responsible for advising on important national monuments and memorials, or on makeovers of the Oval Office. The U.S. poet laureate is appointed by Congress, so an architect laureate might have advised congress to be a little more restrained in the $621 million Capitol Visitor Center, or perhaps referee the Eisenhower Memorial imbroglio. But I doubt Congress would look favorably on such a position. After all, building buildings costs money, poets are cheaper (currently $35,000 a year).

January 31, 2013

Norten’s Taste

Museo Amparo, Puebla

I attended a public lecture by my friend Enrique Norten last night. He described recent work: a museum in Puebla, a business school for Rutgers, and a city hall in Acapulco—all three competition winners, and all three under construction. All are impressive buildings in different ways. The museum is an addition shoe-horned into a historic complex of buildings, the university building is a self-conscious icon for a re-planned campus, and the capitol is an imaginative exercise in energy conservation. But what struck me is what he did not talk about, but which seemed to me an important aspect of his work: his Taste. Norten’s architecture falls into the category of lightweight construction, and brings to mind Renzo Piano, although it appears less studied and less obsessively detailed. And Piano’s friendly designs can be so unthreatening as to be almost ingratiating, while Norten is never cuddly, and can be downright standoffish in a stylish contemporary way. The architectural equivalent of his five o’clock shadow. His approach to design is to solve problems, a quality he shares with Norman Foster. But while the latter’s work has become increasingly polished, Norten’s taste remains that of an ascetic. A Mexican Zumthor, one might say, a diligent craftsman, though without the Swiss architect’s preciousness, and working on a larger canvas.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers