Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 37

June 13, 2013

Sant Francesc

I took this photo in the spring of 1967, in the village of San Francisco on the Balearic island of Formentera where I was living at the time. The wall in the background is the church of Sant Francesc Xavier, an eighteenth century building, fortified against attacks by the Barbary pirates who periodically descended on the island. The mesh above the court must be there to keep the soccer ball in bounds. I assume that the taller figure is that of the local priest, or brother, acting as a referee, as he is the only one wearing street shoes. I took this with a Leica M3, I think. Like many architecture students (I had just graduated) I was a devotee of sports cars (which I couldn’t afford–my first car was a VW bug, though later I graduated to a Mini Cooper) and cameras (which I could). So what do I like about the photo? Volumes in sun and shade–the Corbusian trology–boys and play, the moment frozen forever; it is the world of a 24 year-old architect on the edge of life.

June 7, 2013

FOLLOW THE MONEY

Whenever I hear of complaints about the makeup of the architectural profession, whether it concerns race or gender, I think of a comment by my old teacher, Norbert Schoenauer. He observed that a disproportionate number of the architects working in the housing field in Canada were either Jews or immigrants. He cited Irving Grossman, Jack Diamond, Peter Dickinson, Oscar Newman, Sandy van Ginkel, Andre and Eva Vescei, and himself. Schoenauer surmised that since housing commissions were less lucrative, they were neglected by established architects, and hence became an opening for “outsiders.” Incidentally, the same was true in the US, think of Emery Roth, Clarence Stein, Bertrand Goldberg, Percival Goodman, and Morris Lapidus. Or Albert Kahn (an immigrant as well as a Jew), who built his practice on designing factories, another neglected field;

Social connections have always been a big part of a successful architectural career. In the early part of the twentieth century, WASP clients tended to hire WASP architects–Burnham, McKim, Hastings, Cram, Platt, Pope, Delano, Atterbury. This started to change when European immigrants (some of whom were also Jews), came to the fore: Schindler, Neutra, Mies, Gropius, Breuer, Belluschi, Sert. When Louis I. Kahn began his career, he joined forces with Oscar Stonorov, another immigrant, and designed mainly housing, but by the 1960s, he began to get institutional commissions, and became the leading architect in the US. For the first time, many of the the most prominent names in American architecture were no longer WASPs: not only Kahn, but also Gordon Bunshaft, Max Abramovitz, Minoru Yamasaki, I. M. Pei, Frank Gehry, Richard Meier, Robert A. M. Stern, Cesar Pelli. This shift was less due to open-mindedness, although that is a part of the story, as to a change in the nature of the architectural clientele. Yes, talent is important, but you also have to follow the money.

June 2, 2013

SAD ENDS

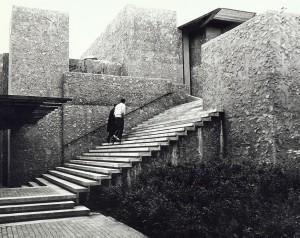

Trent University

Ron Thom (1923-1986) is not a name any longer familiar to many, but in the 1960s he was one of Canada’s leading architects, second only to his fellow Vancouverite, Arthur Erickson. Like Erickson, Thom started small, designing prize-wining houses in a woodsy, modernist style that became associated with the West Coast. Like Erickson, he had difficulty translating his exquisite personal designs into the world of large, corporate commissions, and the arc of both architect’s careers contains more tragedy than triumph. Nevertheless, Thom produced at least two masterpieces of collegiate architecture, Massey College (1963) in Toronto and Trent University (1963-79). Both are unusual in being inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, at a time when most people consigned the master’s work to the dusty shelf of history. They are doubly unusual in looking back to the young Wright of Midway Gardens and the Imperial Hotel. Perhaps it was Thom’s lack of formal training (he went to art school and studied painting) that enabled him to find something fresh in these 50-year-old buildings. Sadly, his later work did not fulfill the promise of these masterworks. Like Louis Sullivan, Thom died young (Thom was 63, Sulivan 68) of alcoholism.

Sullivan and Thom’s sad ends are exceptions in the world of architects. According to Vasari, Raphael, who died at only 37, succumbed to excessive love-making, which is a bitter-sweet end. Usually, when architects die before their time they do so thanks to disease (Richardson, Mendelsohn, Kahn, Saarinen, Stirling). Violent ends are rare: the great Gaudí was killed by a streetcar, Stanford White was murdered by a jealous husband. Most architects have lived long lives, productive until the end (I wrote about this in Slate). I was once told of a Viennese architect who comitted suicide when a prominent government building he built was discovered to have no stairs. But surely that is an apocryphal story. Wikipedia lists only nineteen “architects who committed suicide,” although the only widely recognizable name is that of the great Borromini, who suffered from depression.

May 21, 2013

GOD’S HOUSE

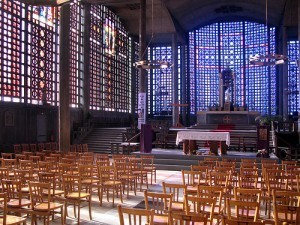

Notre-Dame du Raincy, Auguste Perret, arch.

In an article in the current issue of Design Intelligence, the architect and Notre Dame professor, Duncan G. Stroik writes that the design of contemporary megachurches, which he characterizes as “non-architecture,” leaves much to be desired. It’s hard to argue with that (see my Slate slide show on megachurches here). But then Stroik goes on to equate megachurches with modernism, whence he elides into the classicist’s standard litany of the failings of modernist architecture. “Gone was the need for human scale and proportions, natural materials, historical elements, and the classical understanding of civic order,” he writes. I am not sure what he means by “natural materials,” but presumably concrete does not qualify, yet Auguste Perret’s all-concrete Notre-Dame du Raincy, an early classic, is a modern reinterpretation of the Gothic. I don’t know that Gaudi had a classical understanding of civic order, but Sagrada Familia shines with his deep religiosity. So does Fay Jones’s Thorncrown Chapel, which incorporates natural materials and human scale.

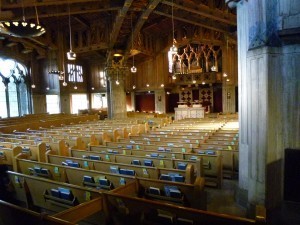

First Church of Christ Scientist, Bernard Maybeck, arch.

Stroik similarly exaggerates when he writes that Wright, Le Corbusier, Aalto and Mies “did very few churches.” It is true that Mies designed only the rather forlorn chapel at IIT, but Le Corbusier built three churches, and Wright built no less than six places of worship: Unity Temple, Unitarian Meeting House, a Greek Orthodox church, Congregation Church, Beth Sholom Synagogue, and a chapel at Florida Southern University. As for Aalto, he designed six churches as well as two funerary chapels (one unbuilt). I have not seen his transcendent church at Imatra, but I have seen Wright’s Beth Sholom, and it is a numinous space. So is the dark cave of Ronchamp. I recently re-visited Bernard Maybeck’s First Church of Christ Scientist in Berkeley. While this exceptional design is hardly a paragon of modernism, neither is it bound by tradition. But it is a moving and much loved place of worship.

May 16, 2013

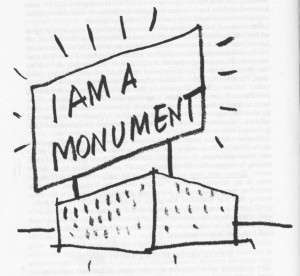

I AM A MEMORIAL

The book launch of Civic Art, a history of the first hundred years of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, was the occasion for the Charles Atherton Memorial Lecture at the National Building Museum, delivered this year by Thomas Luebke, the current secretary of the commission. In the course of his talk, Luebke made an interesting observation: commemorative memorials in Washington, D.C. have become increasingly influenced by other media, specifically photography. When the Lincoln Memorial was completed in 1922, Daniel Chester French’s statue of the president was the sculptor’s interpretation of his subject (the head was based on a cast that French had taken while Lincoln was still alive), and in due course the seated figure became a national icon. When the Marine Corps Memorial was unveiled in 1954, it consisted of a giant statue based on the AP correspondent Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. Instead of creating an original work, the “sculptor,” one Felix de Weldon, simply appropriated an already famous image. The photo, not the memorial, was the real icon. More recent commemorative works, such as the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, have been similarly based on photographs. Likewise the current version of the proposed memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Why does this matter? Memorials that simply mimic another medium lose much of their power; they are more like billboards than sacred markers. Robert Venturi once proposed that a civic building should be designed as a simple box with a blinking sign on top saying I AM A MONUMENT. One is never quite sure how seriously to take Venturi’s offbeat pronouncements, but the current crop of photographic-inspired memorials suggests just how thin the joke really is.

The book launch of Civic Art, a history of the first hundred years of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, was the occasion for the Charles Atherton Memorial Lecture at the National Building Museum, delivered this year by Thomas Luebke, the current secretary of the commission. In the course of his talk, Luebke made an interesting observation: commemorative memorials in Washington, D.C. have become increasingly influenced by other media, specifically photography. When the Lincoln Memorial was completed in 1922, Daniel Chester French’s statue of the president was the sculptor’s interpretation of his subject (the head was based on a cast that French had taken while Lincoln was still alive), and in due course the seated figure became a national icon. When the Marine Corps Memorial was unveiled in 1954, it consisted of a giant statue based on the AP correspondent Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. Instead of creating an original work, the “sculptor,” one Felix de Weldon, simply appropriated an already famous image. The photo, not the memorial, was the real icon. More recent commemorative works, such as the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, have been similarly based on photographs. Likewise the current version of the proposed memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Why does this matter? Memorials that simply mimic another medium lose much of their power; they are more like billboards than sacred markers. Robert Venturi once proposed that a civic building should be designed as a simple box with a blinking sign on top saying I AM A MONUMENT. One is never quite sure how seriously to take Venturi’s offbeat pronouncements, but the current crop of photographic-inspired memorials suggests just how thin the joke really is.

May 13, 2013

GREATEST HITS

860 Lakeshore Drive (1948-51)

Anyone watching “Ten Buildings that Changed America” last night on PBS was challenged to make their own additions or deletions to the list. I must admit that I was surprised to find Jefferson’s Virginia Capitol rather than his University of Virginia, leading the Top Ten, for it was the university that set the model for the bucolic college campus, which is one of America’s great architectural achievements. But the show convinced me that the Capitol, which established Classicism as the de facto government style, deserves to be included. No one would argue with Trinity Church, the Wainwright, or the Robie House. Albert Kahn’s factories for Henry Ford are an outlier, but every Greatest Hits needs a surprise. Seeing the factories is a reminder of how much more advanced in functionalist design America was compared to Europe (the Bauhauslers greatly admired Kahn’s work), although the Prussian-born Kahn wisely restricted his no-frills style to factories. I’m not sure I would have included Saarinen’s Dulles airport, which jumbo jets rendered obsolete within a decade, and whose goofy mobile lounges had few takers. Dulles never had the national influence of, say, Boston’s South Station (Shepley, Ruttan & Coolidge, 1898). And does the Seagram Building really qualify as a building than changed America? Beloved by architects—though not so much by the public—the Seagram was too expensive to be widely influential. And by the time it was built—1958—the gridded steel-and-glass curtain wall was already in widespread use, thanks to Mies’s pioneering 860 Lake Shore Drive apartments. But then the producers could not have included a lively interview with Phyllis Lambert, which would have been a loss.

May 8, 2013

Stiltsville

Beachtown is a New Urbanism second-home village in Galveston. Construction began in 2005, after a protracted planning and permitting period. The projected size is about 2,000 houses. Progress has been slow, but then Galveston is hardly a hot development area. Although only fifty miles from Houston, the city never really recovered from a devastating 1900 hurricane. The hurricane, and the Houston Ship Canal, ensured that Houston prospered while Galveston languished. So building a Texas version of Seaside, even when it is planned by Duany & Plater-Zyberk, is a real estate challenge (I saw only a single house under construction). Equally challenging is the requirement that since Beachtown is immediately adjacent to the beach, all habitable space must be raised above the base flood elevation (BFE). Since Hurricane Ike (2008) had a 15-20 foot storm surge, the BFE is high, and the houses are raised about twelve feet above grade on closely spaced timber piles. The

Beachtown is a New Urbanism second-home village in Galveston. Construction began in 2005, after a protracted planning and permitting period. The projected size is about 2,000 houses. Progress has been slow, but then Galveston is hardly a hot development area. Although only fifty miles from Houston, the city never really recovered from a devastating 1900 hurricane. The hurricane, and the Houston Ship Canal, ensured that Houston prospered while Galveston languished. So building a Texas version of Seaside, even when it is planned by Duany & Plater-Zyberk, is a real estate challenge (I saw only a single house under construction). Equally challenging is the requirement that since Beachtown is immediately adjacent to the beach, all habitable space must be raised above the base flood elevation (BFE). Since Hurricane Ike (2008) had a 15-20 foot storm surge, the BFE is high, and the houses are raised about twelve feet above grade on closely spaced timber piles. The  effect is unusual. While the project has all the features one would expect in a DPZ design—interesting plan, sidewalks, thoughtful planting, pathways—the scale is distinctly different. Instead of cottages, the houses resemble Victorian mansions, in part because this is Texas after all and they are very large, and in part because they are in some cases four-stories tall, thanks to the BFE. As you walk down the street you don’t see friendly porches, only driveways and parking bays. Next to Beachtown is a rather incongruous 14-story condominium tower. Or perhaps it’s not so incongruous. If one insists on living next to the water in such a dangerous location—a dubious proposition—one would want to be in a concrete structure high, high above the flood surge.

effect is unusual. While the project has all the features one would expect in a DPZ design—interesting plan, sidewalks, thoughtful planting, pathways—the scale is distinctly different. Instead of cottages, the houses resemble Victorian mansions, in part because this is Texas after all and they are very large, and in part because they are in some cases four-stories tall, thanks to the BFE. As you walk down the street you don’t see friendly porches, only driveways and parking bays. Next to Beachtown is a rather incongruous 14-story condominium tower. Or perhaps it’s not so incongruous. If one insists on living next to the water in such a dangerous location—a dubious proposition—one would want to be in a concrete structure high, high above the flood surge.

May 4, 2013

In the Shade

The vast majority of certified green office buildings today seem to be all-glass. That’s counterintuitive, since glass lets in the sun’s heat. Surely it’s time to revisit one of Le Corbusier’s modernist trademarks, the brise-soleil, or sunshade. Corb’s sunshades tended to be made out of concrete, which is actually the wrong material, since it absorbs the sun’s heat, stores it, then dissipates it long after the sun goes down. But the basic idea is sound: prevent the rays of the sun from entering and heating up the interior of the building. I was reminded of Corb during a recent visit to Houston. There are several downtown office buildings of the sixties and seventies here whose design actually acknowledges the god-awful summers. Pictured here is 1001 Preston Street, designed in 1978 by Kenneth Bentsen, a local practitioner. The ten-story precast concrete frame has a deep facade, à la SOM, and is fitted with metal louvers that act as sun shades. Of course, the newest crop of towers is all-glass. No doubt they have a LEED rating.

The vast majority of certified green office buildings today seem to be all-glass. That’s counterintuitive, since glass lets in the sun’s heat. Surely it’s time to revisit one of Le Corbusier’s modernist trademarks, the brise-soleil, or sunshade. Corb’s sunshades tended to be made out of concrete, which is actually the wrong material, since it absorbs the sun’s heat, stores it, then dissipates it long after the sun goes down. But the basic idea is sound: prevent the rays of the sun from entering and heating up the interior of the building. I was reminded of Corb during a recent visit to Houston. There are several downtown office buildings of the sixties and seventies here whose design actually acknowledges the god-awful summers. Pictured here is 1001 Preston Street, designed in 1978 by Kenneth Bentsen, a local practitioner. The ten-story precast concrete frame has a deep facade, à la SOM, and is fitted with metal louvers that act as sun shades. Of course, the newest crop of towers is all-glass. No doubt they have a LEED rating.

April 27, 2013

Prez Library

Since I was on the design committee that advised Laura Bush on the George W. Bush presidential library, I am not in a position to offer an objective review of the architecture of the building. You will have to make up your own mind. I suspect many people will do this without actually visiting the building, but when you read the reviews keep several things in mind. Presidential libraries should have an intimate quality since they are, in one measure, personal shrines. The most successful example in this regard is the FDR Library in Hyde Park, NY, a small Dutch colonial building designed by the president himself. But today’s presidential libraries have grown very large (226,000 square feet in Dallas), and the challenge for the architect is how to design a building so that it doesn’t overwhelm the visitor. The LBJ Library in Austin, doesn’t do this; LBJ may have been a larger-than-life figure, but Bunshaft’s ponderous design is merely monumental. Scale is all. A presidential “library” actually consists of a museum, a scholarly study center, archives (largely digital, but in the Bush archive, still including 70 million pieces of paper), and here also a think tank/institute, akin to the Hoover Institution at Stanford. So, this unusual building type is also a planning challenge, since these parts function independently: some are public, some are private, some belong to the federal government, some don’t. Since the Bush Center incorporates a public museum and institutional components, as well as the presidential quarters (in this case not lived in, but used for entertaining eminent visitors), the architecture must demonstrate different levels of formality and intimacy. Finally, presidential libraries are there for the long haul. No building is timeless, but the design of a presidential library should not become immediately dated, which favors a conservative approach. While some reviewers have sought to find parallels between Robert A. M. Stern’s design and Mussolini’s Fascist architecture, surely the real model is pre-World War II US government architecture, like Paul Cret’s Federal Reserve Board Building, which was the delicate moment when Classicists adopted a modernist sensibility. New Classicism, Cret called it.

Since I was on the design committee that advised Laura Bush on the George W. Bush presidential library, I am not in a position to offer an objective review of the architecture of the building. You will have to make up your own mind. I suspect many people will do this without actually visiting the building, but when you read the reviews keep several things in mind. Presidential libraries should have an intimate quality since they are, in one measure, personal shrines. The most successful example in this regard is the FDR Library in Hyde Park, NY, a small Dutch colonial building designed by the president himself. But today’s presidential libraries have grown very large (226,000 square feet in Dallas), and the challenge for the architect is how to design a building so that it doesn’t overwhelm the visitor. The LBJ Library in Austin, doesn’t do this; LBJ may have been a larger-than-life figure, but Bunshaft’s ponderous design is merely monumental. Scale is all. A presidential “library” actually consists of a museum, a scholarly study center, archives (largely digital, but in the Bush archive, still including 70 million pieces of paper), and here also a think tank/institute, akin to the Hoover Institution at Stanford. So, this unusual building type is also a planning challenge, since these parts function independently: some are public, some are private, some belong to the federal government, some don’t. Since the Bush Center incorporates a public museum and institutional components, as well as the presidential quarters (in this case not lived in, but used for entertaining eminent visitors), the architecture must demonstrate different levels of formality and intimacy. Finally, presidential libraries are there for the long haul. No building is timeless, but the design of a presidential library should not become immediately dated, which favors a conservative approach. While some reviewers have sought to find parallels between Robert A. M. Stern’s design and Mussolini’s Fascist architecture, surely the real model is pre-World War II US government architecture, like Paul Cret’s Federal Reserve Board Building, which was the delicate moment when Classicists adopted a modernist sensibility. New Classicism, Cret called it.

April 23, 2013

Lest We Forget

Norwegian Resistance Museum, photo by Jim Eliason

We remember the past in different ways. World War II produced memoirs (Frank, Wiesel, Tregaskis), histories (Churchill, Shirer, Keegan), novels (Mailer, Jones, Heller), and innumerable films and television documentaries. So did the Vietnam War (Dispatches, A Rumor of War, A Bright Shining Lie, The Best and the Brightest, as well as The Deerhunter, Apocalypse Now, and Platoon). Of course, there are also built memorials, which form the focus of wreath-layings and commemorative ceremonies, but our memory resides in many places. So I find the present custom of making so-called visitor centers an integral part of memorials odd, not to say redundant. A museum was to be a part of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., but was wisely removed. Less wisely, Congress has approved an underground “education center” next to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, although that project happily appears stalled. The other night, “Sixty Minutes” showed the 9/11 museum under construction at the World Trade Center site. You would have thought that the vast outdoor memorial would have been sufficient commemoration, but we are also to have a vast underground space devoted to the events of that unhappy day. I once visited the Resistance museum in Oslo, the subject of which was the Norwegian resistance to the Nazi occupation during World War II. It is estimated that 40,000 men and women took an active part in the resistance movement. The museum displays included Sten guns, short-wave radios, and miniature tableaux of wartime scenes, with tiny armored cars being sabotaged, and agents parachuting among cotton-batten clouds. It was informative, charming, and low-key in a laid back Scandinavian sort of way. If we must have a 9/11 museum, I wish it were that modest.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers