Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 33

December 1, 2013

STAMPS

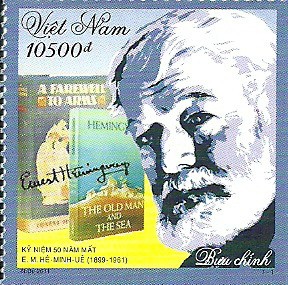

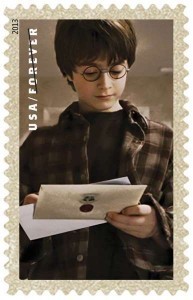

On November 19 the U.S. Post Office issued a series of 20 stamps honoring . . . Harry Potter. There has been a bit of a kerfuffle, since the commission that normally reviews the subjects of new stamps was by-passed in the process, and also because of the non-American subject. I have no objection to honoring a foreigner, after all, Vietnam has recently issued a 10,500 dong (roughly 50 cents) stamp honoring Ernest Hemingway, so why not commemorate a British subject. But instead of celebrating the author J. K. Rowling, the U.S. stamps honor her fictional characters—including Hedwig the Owl—moreover, the images are not illustrations that suggest reading or books, but stills from the Warner Bros. movie. The commercial nature of this misguided venture is underlined by the place where the stamps are being issued: Orlando, home of a Harry Potter theme park. Apparently, the cash-strapped Post Office has been keeping an eye on its counterpart in New Zealand, which last year issued a set of six stamps commemorating characters from the movie version of The Hobbit. The Vietnamese Hemingway stamp looks downright classy by comparison.

On November 19 the U.S. Post Office issued a series of 20 stamps honoring . . . Harry Potter. There has been a bit of a kerfuffle, since the commission that normally reviews the subjects of new stamps was by-passed in the process, and also because of the non-American subject. I have no objection to honoring a foreigner, after all, Vietnam has recently issued a 10,500 dong (roughly 50 cents) stamp honoring Ernest Hemingway, so why not commemorate a British subject. But instead of celebrating the author J. K. Rowling, the U.S. stamps honor her fictional characters—including Hedwig the Owl—moreover, the images are not illustrations that suggest reading or books, but stills from the Warner Bros. movie. The commercial nature of this misguided venture is underlined by the place where the stamps are being issued: Orlando, home of a Harry Potter theme park. Apparently, the cash-strapped Post Office has been keeping an eye on its counterpart in New Zealand, which last year issued a set of six stamps commemorating characters from the movie version of The Hobbit. The Vietnamese Hemingway stamp looks downright classy by comparison.

November 21, 2013

FALLINGWATER

Random thoughts after a recent visit. Isn’t it strange that a millionaire’s plaything, a weekend house that cost a whopping $150,000 in 1937 ($2.4 million today), in which the servants outnumbered the occupants, and in which meals were served by a butler, should nevertheless have become the most popularly admired modern house in America. There are a number if explanations. I recently visited a huge (40,000 square feet) house designed by Paul Rudolph; it felt like being in a hotel lobby. Philip Johnson’s Glass House is much smaller, but most people couldn’t imagine living in it. Richard Meier’s Rachofsky House in Dallas is a beautiful purist composition, but it resembles a museum—which is its present function. Not so Fallingwater. The enclosed space is not large (about 3,000 square feet), and although the living room is sprawling, the bedrooms are very small. And compared to a modern McMansion, it’s all downright Spartan; no marble bathrooms, no walk-in closets, no vast kitchen, no media room. The materials are unprepossessing, and the details are either simple or absent—there is none of that obsessive precision that makes modern houses feel like luxury cars. The luxury at Fallingwater is all in the cantilevered terraces, which feel like open-air tree houses. Like most visitors, I went down the path to experience the View. It is all one could ask for. But it is a mark of this curiously demure folly, that the iconic view is not seen as one approaches, or from any of the vantage points around the house, where the design is experienced in bits and pieces. It is as if Wright were saying, “Oh, by the way, you should see it from down there.”

Random thoughts after a recent visit. Isn’t it strange that a millionaire’s plaything, a weekend house that cost a whopping $150,000 in 1937 ($2.4 million today), in which the servants outnumbered the occupants, and in which meals were served by a butler, should nevertheless have become the most popularly admired modern house in America. There are a number if explanations. I recently visited a huge (40,000 square feet) house designed by Paul Rudolph; it felt like being in a hotel lobby. Philip Johnson’s Glass House is much smaller, but most people couldn’t imagine living in it. Richard Meier’s Rachofsky House in Dallas is a beautiful purist composition, but it resembles a museum—which is its present function. Not so Fallingwater. The enclosed space is not large (about 3,000 square feet), and although the living room is sprawling, the bedrooms are very small. And compared to a modern McMansion, it’s all downright Spartan; no marble bathrooms, no walk-in closets, no vast kitchen, no media room. The materials are unprepossessing, and the details are either simple or absent—there is none of that obsessive precision that makes modern houses feel like luxury cars. The luxury at Fallingwater is all in the cantilevered terraces, which feel like open-air tree houses. Like most visitors, I went down the path to experience the View. It is all one could ask for. But it is a mark of this curiously demure folly, that the iconic view is not seen as one approaches, or from any of the vantage points around the house, where the design is experienced in bits and pieces. It is as if Wright were saying, “Oh, by the way, you should see it from down there.”

November 8, 2013

GLASSY EYED

I like glass as much as the next guy, but enough is enough. Just as the sixties architects went crazy about exposed concrete, architects today can’t get enough of glass. It’s used in the name of transparency, reflectivity, technology, ecology. If you’re a minimalist you like glass because it’s not there; if you’re a techie, you can accessorize it with all sorts of neat details; if you’re a not-very-good architect, glass will absolve you of having to design the facade. And who thinks up those glass details? Glass walls overlapping glass walls; facades that cantilever into this air; glass butting glass. Structural glass has its place, but it’s become a cliché. Gehry did a witty riff on fritted glass in the IAC Building on Manhattans Lower West Side, but most glass buildings are one-liners. Nor are glass buildings benign, as we have learnt in Dallas and London. I wonder how this glass architecture will fare in the future? Exposed concrete did not do so well, as so many unloved Brutalist buildings demonstrate. I’m not sure that glass buildings are equally disliked, but neither are they cherished. It’s hard to cosy up to transparency.

I like glass as much as the next guy, but enough is enough. Just as the sixties architects went crazy about exposed concrete, architects today can’t get enough of glass. It’s used in the name of transparency, reflectivity, technology, ecology. If you’re a minimalist you like glass because it’s not there; if you’re a techie, you can accessorize it with all sorts of neat details; if you’re a not-very-good architect, glass will absolve you of having to design the facade. And who thinks up those glass details? Glass walls overlapping glass walls; facades that cantilever into this air; glass butting glass. Structural glass has its place, but it’s become a cliché. Gehry did a witty riff on fritted glass in the IAC Building on Manhattans Lower West Side, but most glass buildings are one-liners. Nor are glass buildings benign, as we have learnt in Dallas and London. I wonder how this glass architecture will fare in the future? Exposed concrete did not do so well, as so many unloved Brutalist buildings demonstrate. I’m not sure that glass buildings are equally disliked, but neither are they cherished. It’s hard to cosy up to transparency.

November 7, 2013

CAR BARN

1934 Ford Brewster Town Car

A group of us had dinner in a Chicago garage last night surrounded by Richard H. Driehaus’s car collection. The collection of about 50 cars, I would guess, includes classics such as a 1948 Tucker Torpedo, one of only 51 built, and a 1954 Kaiser Darrin, a 2-seater with weird pocket doors and a fiberglas body. There were a number of concept and customized cars. A 1941 Lincoln Continental V-12 rebuilt by Raymond Loewy, includes a removable plexiglas top and porthole windows. One of my favorites was a 1934 Ford Brewster Town Car, which resembled a high-tech insect. There was much talk among us about these old cars as works or art, and artistry was much in evidence in the sculptural shapes. But what struck me as setting these cars apart from today’s somewhat insipid models, is character. The last car I owned that had real character was Citroen 2CV. I have owned many safer, more comfortable, more dependable—and God-knows faster—cars since. But none that had more personality.

October 27, 2013

LOOKING AT PICTURES

The other day, I was asked to talk to a class of architecture students who had been given a museum as a studio project. Although architects refer to museums as “public buildings,” they are public in a peculiar way, I told them. I illustrated this by comparing a museum to a theater. In a theater, being part of the audience is an integral part of the experience: the more people the better. In fact, a half-empty theater diminishes one’s enjoyment of the play. Being in a museum is different: the more people you have to share it with, the worse the experience. Being in a museum first thing in the morning, before the crowds appear, is marvelous; lining up in a jostling crowd to have your twenty seconds in front of the Mona Lisa is a caricature of museum-going. For at its heart, the museum experience is intensely private, just you and the painting. At the same time, the museum is a public institution, and the challenge for the architect is to manage the transition, from the time you enter to that quiet moment, standing in front of the work of art. The Guggenheim in New York is a poor museum because the transition is too abrupt: you have a split second between gazing at the spiraling ramps and the void, and turning to look at the art. The early-twentieth-century museum handled it much better. The transition occurred as you climbed the grand staircase; at the bottom you were in the crowded lobby; by the time you reached the top you had left that behind you, literally, and were ready to enter the galleries. Kahn, at the Center for British Art at Yale, understood. You enter a tall empty space with only glimpses of the galleries, then you climb the stair inside a confined concrete cylinder, then, finally, you are in the quiet rooms with the paintings.

The other day, I was asked to talk to a class of architecture students who had been given a museum as a studio project. Although architects refer to museums as “public buildings,” they are public in a peculiar way, I told them. I illustrated this by comparing a museum to a theater. In a theater, being part of the audience is an integral part of the experience: the more people the better. In fact, a half-empty theater diminishes one’s enjoyment of the play. Being in a museum is different: the more people you have to share it with, the worse the experience. Being in a museum first thing in the morning, before the crowds appear, is marvelous; lining up in a jostling crowd to have your twenty seconds in front of the Mona Lisa is a caricature of museum-going. For at its heart, the museum experience is intensely private, just you and the painting. At the same time, the museum is a public institution, and the challenge for the architect is to manage the transition, from the time you enter to that quiet moment, standing in front of the work of art. The Guggenheim in New York is a poor museum because the transition is too abrupt: you have a split second between gazing at the spiraling ramps and the void, and turning to look at the art. The early-twentieth-century museum handled it much better. The transition occurred as you climbed the grand staircase; at the bottom you were in the crowded lobby; by the time you reached the top you had left that behind you, literally, and were ready to enter the galleries. Kahn, at the Center for British Art at Yale, understood. You enter a tall empty space with only glimpses of the galleries, then you climb the stair inside a confined concrete cylinder, then, finally, you are in the quiet rooms with the paintings.

October 20, 2013

MONTRÉAL

I haven’t lived in Montreal for twenty years, but it’s the city where I passed my twenties, thirties, and forties, so it is a place full of memories. But like all North American cities, it is in constant flux; the city of today is not the one I left in 1993. The view of Mount Royal outside my hotel window is comfortingly familiar, but the downtown is undeniably different. It appears oddly both more prosperous and more provincial than I remember. The Ritz Carleton, the first Ritz hotel in North America and the grande dame of Sherbrooke Street, is now two-thirds condominiums, and Daniel Bouloud has opened his thirteenth–or is it his fourteenth?–restaurant on the ground floor. In fact condominiums are springing up everywhere in the city. Are there so many Quebecers that suddenly want to live downtown? Unlikely. Montreal is succumbing to the phenomenon of the globe-trotting homeowner, who owns pieds-à-terre in London, New York, and Paris. If terrorism, or global warming, or civil unrest threatens where you live, what better place to park some of your wealth than placid Canada. Toronto and Vancouver are still the first choices based on urban amenities in Toronto and climate and natural setting in Vancouver, but Montreal is a cheaper, though colder, alternative. Of course, there is simmering Quebecois separatism whose latest manifestation has been dubbed “pastagate”–an Italian restaurant received a government warning for using “pasta” and “calamari” on its menu, instead of their French equivalents. And students occasionally demonstrate in the streets in proper Gallic fashion. But if you are a Russian oligarch these are small irritations. That, at least, was my impression as we walked down Sherbrooke last evening, glancing up at all those darkened apartment windows.

I haven’t lived in Montreal for twenty years, but it’s the city where I passed my twenties, thirties, and forties, so it is a place full of memories. But like all North American cities, it is in constant flux; the city of today is not the one I left in 1993. The view of Mount Royal outside my hotel window is comfortingly familiar, but the downtown is undeniably different. It appears oddly both more prosperous and more provincial than I remember. The Ritz Carleton, the first Ritz hotel in North America and the grande dame of Sherbrooke Street, is now two-thirds condominiums, and Daniel Bouloud has opened his thirteenth–or is it his fourteenth?–restaurant on the ground floor. In fact condominiums are springing up everywhere in the city. Are there so many Quebecers that suddenly want to live downtown? Unlikely. Montreal is succumbing to the phenomenon of the globe-trotting homeowner, who owns pieds-à-terre in London, New York, and Paris. If terrorism, or global warming, or civil unrest threatens where you live, what better place to park some of your wealth than placid Canada. Toronto and Vancouver are still the first choices based on urban amenities in Toronto and climate and natural setting in Vancouver, but Montreal is a cheaper, though colder, alternative. Of course, there is simmering Quebecois separatism whose latest manifestation has been dubbed “pastagate”–an Italian restaurant received a government warning for using “pasta” and “calamari” on its menu, instead of their French equivalents. And students occasionally demonstrate in the streets in proper Gallic fashion. But if you are a Russian oligarch these are small irritations. That, at least, was my impression as we walked down Sherbrooke last evening, glancing up at all those darkened apartment windows.

October 15, 2013

STYLE CONT’D.

U.S. Army Supply Base, Brooklyn (Cass Gilbert, 1918-19)

In his snarky review of How Architecture Works in the Wall Street Journal, Joseph Rykwert (who was a colleague of mine at Penn, something the review doesn’t reveal) quotes the Count de Buffon, Le style c’est l’homme mȇme, to support his view that the choice of a style is a “warrant of personal integrity.” I’m not sure that’s true in personal affairs, after all we dress differently for a morning jog than for the office, but it’s definitely not true in building design. Rykwert admires Mies for building the Farnsworth House in the same steel-and-glass style as his office buildings, but at IIT Mies adopted the same style for the chapel and the boiler house, which is less admirable, in my estimation. When Christopher Wren, in most things a confirmed classicist, was commissioned to build Tom Tower at Christ Church in Oxford, he said it “ought to be Gothick to agree with the Founders worke,” and designed a wonderfully original interpretation of that medieval style. That same year he also designed a Gothic church. The idea that a style should have universal application was a strongly held belief of International Style architects, and is one of the failings of modernism. This was not a mistake made by their more traditional contemporaries. When Cass Gilbert was commissioned to build the U.S. Army Supply Base in Brooklyn in 1918, he designed a severe (exposed concrete) structure devoid of his usual Beaux-Arts ornament, relying instead on simplicity and good proportions. But, as the U.S. Supreme Court shows, what was right for a warehouse was not necessarily right for a courthouse.

October 11, 2013

STYLES AND THE MAN

Bethesda Naval Hospital, Paul Cret, 1939-42

Gary Brewer, a partner at Robert A. M. Stern Architects, lectured at the Philadelphia Center for Architecture. The talk was illustrated with the firm’s work, which appears to include every conceivable building type, with the possible exception of industrial buildings. These buildings represent a variety of building styles, Traditional, Modern, and Transitional. The last category is interesting, for though rarely alluded to it probably represents the majority of what is built today. Most if not all architects consider themselves either modernists or traditionalists, and develop elaborate justifications for their positions. Not Stern. As Brewer pointed out, for RAMSA, a building’s appearance should not be the result of an architect’s whim, but of its setting. The client has a say, too. Brewer showed a house in California, built for a man who wanted to be reminded of his old home on Long Island, and a town hall whose owners wanted to establish a sense of place where there was none. Hence the advantage of having many stylistic arrows in one’s quiver. There is nothing particularly original in RAMSA’s approach. Most good American architects in the first half of the twentieth century–John Russell Pope, Paul Cret, Bertrand Goodhue–regularly worked in different styles. When Cret designed a power house in Washington, D.C., it did not resemble the Federal Reserve or Bethesda Naval Hospital. It was a matter of decorum. As the confirmed medievalist Ralph Adams Cram pointed out, a Gothic department store or movie theater would make about as little sense as “a Greek railroad train, a Byzantine motor car, a Gothic battleship or a Renaissance airplane.” That was the gravest limitations of the International Style, not its inherent quality, but the fact that it was applied universally.

October 8, 2013

HOUSING THEORY

Last night I took part in a panel organized by Fordham University. The topic was “A Home in the City,” and the discussion was about future housing strategies for New York. The talk ranged over modular housing, micro apartments, affordable housing, single-room occupancy, and zoning regulations. Of course, everyone knows that housing in New York is very expensive–although not equally expensive for everyone. More than 400,000 New Yorkers live in public housing, and almost half of the two-thirds of New Yorkers who are tenants live in rent-controlled apartments. Furthermore, as Mary Anne Gilmartin, the CEO of Forest City Ratner, observed, under current regulations new housing developments are required to provide 20 percent affordable units, that is, the expensive market housing subsidizes the lower-income tenants. “Affordable” in this case is a relative term: $85,900 annual income for a family of four. After the panel, I spoke to Rosemary Wakeman, chair of urban studies at Fordham. She made the point that the unspoken sentiment that lay beneath the surface of the symposium was the feeling of helplessness that middle-class New Yorkers currently had, surrounded by ever more new condo towers for the world’s super-rich. You walk down the street and see the darkened getaways of Russian plutocrats, she said. That reminded me of Lenin’s Theory of Housing. There is no such thing as a housing problem, he said. You simply divide the housing stock by the number of people that require to be housed and that is the amount of housing each citizen gets. Which is precisely what European Communist regimes during the Cold War did. Every citizen had the right to a certain number of square meters of housing, if your dwelling happened to be larger, you had to accept another occupant or two; if you were lucky–or knew whom to bribe–they would be relatives or friends. The Lenin Theory would solve New York’s housing problem overnight, although it would hardly make the Russian plutocrats happy. Been there, done that.

Last night I took part in a panel organized by Fordham University. The topic was “A Home in the City,” and the discussion was about future housing strategies for New York. The talk ranged over modular housing, micro apartments, affordable housing, single-room occupancy, and zoning regulations. Of course, everyone knows that housing in New York is very expensive–although not equally expensive for everyone. More than 400,000 New Yorkers live in public housing, and almost half of the two-thirds of New Yorkers who are tenants live in rent-controlled apartments. Furthermore, as Mary Anne Gilmartin, the CEO of Forest City Ratner, observed, under current regulations new housing developments are required to provide 20 percent affordable units, that is, the expensive market housing subsidizes the lower-income tenants. “Affordable” in this case is a relative term: $85,900 annual income for a family of four. After the panel, I spoke to Rosemary Wakeman, chair of urban studies at Fordham. She made the point that the unspoken sentiment that lay beneath the surface of the symposium was the feeling of helplessness that middle-class New Yorkers currently had, surrounded by ever more new condo towers for the world’s super-rich. You walk down the street and see the darkened getaways of Russian plutocrats, she said. That reminded me of Lenin’s Theory of Housing. There is no such thing as a housing problem, he said. You simply divide the housing stock by the number of people that require to be housed and that is the amount of housing each citizen gets. Which is precisely what European Communist regimes during the Cold War did. Every citizen had the right to a certain number of square meters of housing, if your dwelling happened to be larger, you had to accept another occupant or two; if you were lucky–or knew whom to bribe–they would be relatives or friends. The Lenin Theory would solve New York’s housing problem overnight, although it would hardly make the Russian plutocrats happy. Been there, done that.

October 6, 2013

DESIGNING THE FUTURE

Futuro House

The words visionary and futuristic are generally used as high praise in architectural criticism. But I’m not so sure. Most architectural visions, whether it’s Mendelsohn, Marinetti, or Sant’Elia have not proved accurate–how could they? Too many unpredictable things change, technologically, politically, culturally. “Cities of the future” generally look quaint, decades on. The most interesting visions are the ones that accept odd blends of past and future, like the dystopian metropolis in Blade Runner, or the techno/medieval Village in the TV series The Prisoner (whose setting was actually Sir Clough Williams-Ellis’s Portmeirion). But “visionary” architecture tends to offer a consistent aesthetic, all Erector set, or all curves, or all something. Looks great on the cover of the architecture rag, but what about in 50 years? The Futuro House, for example, designed by the Finnish architect Matti Suuronen, is a fiberglass flying saucer, and the astronautical theme is carried through in the porthole windows, the curvy interior furnishing, and the door/steps that swing down like a plane’s access panel. It must have seemed like the future in the 1960s. The one pictured here, mated with a more earthbound structure, is in Pensacola Beach, Florida. It’s hard to know whether to laugh or cry.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers