Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 31

April 6, 2014

HOBSON’S CHOICE

District of Columbia War Memorial

In the public debate over Frank Gehry’s design for the Eisenhower Memorial, there have been frequent calls to scrap the current design and hold a national design competition, open to all. Again at the recent National Capital Planning Commission meeting that “disapproved” Gehry’s proposal, the claim was made that national competitions are the way that Washington, D.C. memorial designs have always been chosen. Let’s look at the historical record.

Washington Monument: in 1836, public competition won by Robert Mills.

Grant Memorial: design competition won by Henry Merwin Shrady, sculptor, and Edward Pearce Casey, architect.

Lincoln Memorial: an invited two-man competition between John Russell Pope and Henry Bacon, who won.

Jefferson Memorial: no competition, Pope was appointed the architect.

FDR Memorial: in 1960, open architects competition won by William F. Pederson & Bradford S. Tilney but disapproved by Commission of Fine Arts and Roosevelt family; in 1966, an invited architectural competition of 55 leading architects won by Marcel Breuer but disapproved by CFA; in 1974, open architects competition, 90 entries, won by Lawrence Halprin.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial: open pubic competition (1,421 entries) won by Maya Lin.

Korean War Veterans Memorial: open public competition (540 entries) won by a group of students from Penn State.

World War II Memorial: open public competition (407 entries), won by Friedrich St. Florian.

Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial: open public competition (900+ entries) won by ROMA Design Group.

Eisenhower Memorial: 44 architects selected to compete using GSA’s Design Excellence Program, and Gehry chosen from among 4 finalists.

It’s a mixed bag. The Lincoln Memorial was the result of a design competition between two hand-picked architects; the Jefferson Memorial had no competition at all. The Washington Memorial did have a national competition, but the final design is really the work of Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey, who was responsible for its construction. And these are the best three memorials. Conversely, the designers of some of the least compelling memorials—FDR, Korean, WWII, MLK—were chosen through open national competitions. The open competition process was obviously influenced by the Vietnam Memorial, and the hope of uncovering an unknown young designer. Which turns out not to be difficult, maybe impossible, to duplicate. One of my favorite memorials on the Mall is the District of Columbia War Memorial which honors DC residents who fell in WWI. The architect, Frederick H. Brooke, was simply given the job.

April 4, 2014

AN ARCHITECT’S MEMORIAL

The other day, I walked by the memorial to Richard Morris Hunt that stands on Fifth Avenue, next to Central Park. Not many architects get to have a memorial. The only other one I have seen commemorates Andrea Palladio, a lifesize statue in a small square in Vicenza. Hunt’s is more elaborate: a bronze bust of the architect is set in an exedra that includes two female statues, one representing Architecture the other Art. The sculptor was Daniel Chester French; the architect, Bruce Price. The inscription reads: “To Richard Morris Hunt, October 31, 1828 – July 31, 1895, in recognition of his services to the cause of art in America, this memorial was erected 1898 by the art societies of New York.” The societies are listed: the Century Association, to which Hunt belonged; the Municipal Arts Society, which he founded; the Metropolitan Museum, which he had designed; the Artists Artisans of New York; the Architectural League, which he helped found; the National Sculpture Society; the National Academy of Design; the Society of American Artists; the American Institute of Architects, of which he was a founder and the third president; the American Watercolor Society; and the Society of Beaux Arts Architects—Hunt was the first American to attend the Ecole, and founded effectively the first school of architecture in the US. Hunt designed some of the grandest of the grand houses of the Gilded Age, in New York, Newport, and Asheville, NC. But his greatest achievement, for which his friends honored him with this memorial, was to raise the social standing of the architect from that of a glorified carpenter to a fine arts professional. Later practitioners such as Charles McKim and Ralph Adams Cram were better architects, but they all stood on Hunt’s shoulders.

The other day, I walked by the memorial to Richard Morris Hunt that stands on Fifth Avenue, next to Central Park. Not many architects get to have a memorial. The only other one I have seen commemorates Andrea Palladio, a lifesize statue in a small square in Vicenza. Hunt’s is more elaborate: a bronze bust of the architect is set in an exedra that includes two female statues, one representing Architecture the other Art. The sculptor was Daniel Chester French; the architect, Bruce Price. The inscription reads: “To Richard Morris Hunt, October 31, 1828 – July 31, 1895, in recognition of his services to the cause of art in America, this memorial was erected 1898 by the art societies of New York.” The societies are listed: the Century Association, to which Hunt belonged; the Municipal Arts Society, which he founded; the Metropolitan Museum, which he had designed; the Artists Artisans of New York; the Architectural League, which he helped found; the National Sculpture Society; the National Academy of Design; the Society of American Artists; the American Institute of Architects, of which he was a founder and the third president; the American Watercolor Society; and the Society of Beaux Arts Architects—Hunt was the first American to attend the Ecole, and founded effectively the first school of architecture in the US. Hunt designed some of the grandest of the grand houses of the Gilded Age, in New York, Newport, and Asheville, NC. But his greatest achievement, for which his friends honored him with this memorial, was to raise the social standing of the architect from that of a glorified carpenter to a fine arts professional. Later practitioners such as Charles McKim and Ralph Adams Cram were better architects, but they all stood on Hunt’s shoulders.

March 30, 2014

THE GASTRONOMIC ANALOGY

The WTTW documentary movie on Driehaus prizewinner Pier Carlo Bontempi, “A Taste for The Past,” begins with food, a lunch in the architects office in Parma. The analogy between architecture and cooking has always struck me as compelling: they both combine practicality with taste, they both transform physical materials, and in both the eater/user is at the center of the experience. Food needs to be cookable (buildable) and edible (comfortable). There is innovation in cooking—nouvelle cuisine, foams, fusion—yet all cuisines have a base that, for most people, remains the foundation of everyday eating. The parallels extend to education: the novice cook starts by learning how to slice onions (remember that scene in Julia and Julia?), not by actually cooking, and needs to master the omelette before moving on to haute cuisine. There are cooking fads, but ultimately all cooking is founded in tradition, whose rich variety is the very essence of food. Marcella Hazan does not invent, she guides is through the Italian tradition. The architectural parallels are self-evident. There are traditions to be learned, techniques to be mastered. Taste needs to be cultivated. Variety is key; there are many foods; there is no morality in food, pace vegans. Repetition and replication, not invention, are the essence of cooking. And also of architecture—or should be.

The WTTW documentary movie on Driehaus prizewinner Pier Carlo Bontempi, “A Taste for The Past,” begins with food, a lunch in the architects office in Parma. The analogy between architecture and cooking has always struck me as compelling: they both combine practicality with taste, they both transform physical materials, and in both the eater/user is at the center of the experience. Food needs to be cookable (buildable) and edible (comfortable). There is innovation in cooking—nouvelle cuisine, foams, fusion—yet all cuisines have a base that, for most people, remains the foundation of everyday eating. The parallels extend to education: the novice cook starts by learning how to slice onions (remember that scene in Julia and Julia?), not by actually cooking, and needs to master the omelette before moving on to haute cuisine. There are cooking fads, but ultimately all cooking is founded in tradition, whose rich variety is the very essence of food. Marcella Hazan does not invent, she guides is through the Italian tradition. The architectural parallels are self-evident. There are traditions to be learned, techniques to be mastered. Taste needs to be cultivated. Variety is key; there are many foods; there is no morality in food, pace vegans. Repetition and replication, not invention, are the essence of cooking. And also of architecture—or should be.

March 22, 2014

THE REAL THING

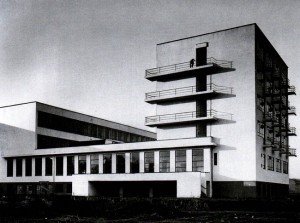

The Bauhaus in context

The Bauhaus idealized

I don’t always agree with Aaron Betsky, but his current Architect column about why he only writes about buildings that he has actually seen is spot on. In architecture, experience is all; photographs are a poor substitute, especially as photographers regularly crop out the surrounding context. Moreover, you should experience a building over an extended period of time, as users do, at different times of day, in different weather. And not only on press day—before the building is put to use—but several years later, when the rough edges have been worn smooth. Of course, if architectural journalists followed Betsky’s dictum, magazines would be a lot thinner than they already are.

And it gets worse. Critics regularly make pronouncements about buildings that can’t be visited because they don’t actually exist—they are unbuilt—perhaps unbuildable. The PA Awards, for example, are given to buildings before they are built, which makes about as much sense as awarding book prizes on the basis of a proposal or outline. I would guess that this habit begins in architecture schools, where students are assessed on the basis of drawings and models, and the illusion is established that these exercises represent real architecture. They don’t. As Robert Hughes once observed, “reproduction is to aesthetic awareness what telephone sex is to sex.” He was talking about paintings and sculptures, but his insight applies equally—perhaps more so—to buildings.

March 8, 2014

THE WRIGHT STUFF

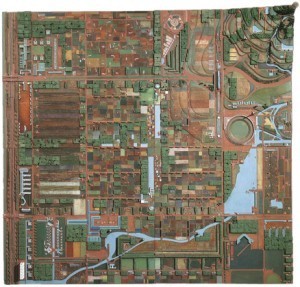

I saw the Frank Lloyd Wright exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art last night. The show is titled “Density and Dispersal” which, as far as I can make out, adds up to the fact that Wright designed Broadacre City, whose model was on display, and also designed tall buildings. That some of these buildings were to be in New York, Chicago, Dallas, and San Francisco, while others were in small towns, was not addressed. In fact, their context was ignored altogether, and characteristically, MoMA treated the buildings as art. But ignoring the intellectually slim conceit behind the exhibition, it was nice to see the drawings and models. The Broadacre model (which I had never seen), is a surprise because it is such an artful object, a sort of tapestry. It also remains a powerful tool to communicate Wright’s idea, which really has little to do with sprawl or suburbanization, except to the extent that it recognizes the automobile (but it also includes a monorail link). It was interesting to see so many students in attendance (it was Free Friday Night), being introduced–I suspect for the first time in many cases–to the old magician. I hope they took away a lesson. Wright and his collaborators produced striking drawings: axonometrics, cut-away perspective views, the breathtaking taaaall section of the Mile-High skyscraper (much more poetic than The Shard, by the way). And all using T-squares and colored pencils—not a computer or laser printer in sight.

I saw the Frank Lloyd Wright exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art last night. The show is titled “Density and Dispersal” which, as far as I can make out, adds up to the fact that Wright designed Broadacre City, whose model was on display, and also designed tall buildings. That some of these buildings were to be in New York, Chicago, Dallas, and San Francisco, while others were in small towns, was not addressed. In fact, their context was ignored altogether, and characteristically, MoMA treated the buildings as art. But ignoring the intellectually slim conceit behind the exhibition, it was nice to see the drawings and models. The Broadacre model (which I had never seen), is a surprise because it is such an artful object, a sort of tapestry. It also remains a powerful tool to communicate Wright’s idea, which really has little to do with sprawl or suburbanization, except to the extent that it recognizes the automobile (but it also includes a monorail link). It was interesting to see so many students in attendance (it was Free Friday Night), being introduced–I suspect for the first time in many cases–to the old magician. I hope they took away a lesson. Wright and his collaborators produced striking drawings: axonometrics, cut-away perspective views, the breathtaking taaaall section of the Mile-High skyscraper (much more poetic than The Shard, by the way). And all using T-squares and colored pencils—not a computer or laser printer in sight.

February 25, 2014

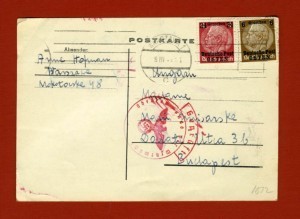

STAMPS

I collected stamps as a boy. Mostly I was imitating my father. He collected only Polish stamps, and his collection begins with the outbreak of the Second World War. The earliest stamp is postmarked “Warszawa 1940.” It is not Polish but German, and bears the stern countenance of Paul von Hindenburg. The stamp is overprinted Osten, meaning East, that is, occupied Poland. My father’s collection includes poignant stamps issued by the provisional Polish government in London, as well as military stamps of the Polish II Corps in Italy, where he served in the SOE. Most of the stamps date from the postwar period and are rather dull in appearance. They portray Polish heroes: Copernicus, Chopin, Madame Curie, and equally predictably, Karl Marx and Stalin, for Poland was then in thrall to Soviet Communism. The album is homemade, the pages, carefully ruled in pencil, have space for every stamp, and include the date of issue, denomination, image, color, and the Stanley Gibbons catalog number. My father was an engineer and he liked everything just so. The entries are in Polish except for the colors which—unaccountably—are in English: “dull purple,” “deep green.” Perhaps it is an early sign of an émigré’s cultural dichotomy. I suppose the collection, which peters out in 1954 shortly after the family emigrated from Britain to Canada, was a way of keeping in touch with the homeland from which he had been rudely separated by the war. Or maybe it was just a way of introducing some small order into a disordered life.

I collected stamps as a boy. Mostly I was imitating my father. He collected only Polish stamps, and his collection begins with the outbreak of the Second World War. The earliest stamp is postmarked “Warszawa 1940.” It is not Polish but German, and bears the stern countenance of Paul von Hindenburg. The stamp is overprinted Osten, meaning East, that is, occupied Poland. My father’s collection includes poignant stamps issued by the provisional Polish government in London, as well as military stamps of the Polish II Corps in Italy, where he served in the SOE. Most of the stamps date from the postwar period and are rather dull in appearance. They portray Polish heroes: Copernicus, Chopin, Madame Curie, and equally predictably, Karl Marx and Stalin, for Poland was then in thrall to Soviet Communism. The album is homemade, the pages, carefully ruled in pencil, have space for every stamp, and include the date of issue, denomination, image, color, and the Stanley Gibbons catalog number. My father was an engineer and he liked everything just so. The entries are in Polish except for the colors which—unaccountably—are in English: “dull purple,” “deep green.” Perhaps it is an early sign of an émigré’s cultural dichotomy. I suppose the collection, which peters out in 1954 shortly after the family emigrated from Britain to Canada, was a way of keeping in touch with the homeland from which he had been rudely separated by the war. Or maybe it was just a way of introducing some small order into a disordered life.

February 16, 2014

NOIR TOWER

In a New York Times op-ed on the failed political career of Michael Ignatieff, the intellectual who had a short-lived stint as leader of Canada’s Liberal party, David Brooks argues that academics are ill-suited to be politicians.“In academia, you are rewarded for candor, intellectual rigor and a willingness to follow an idea to its logical conclusion,” he writes. “In politics, all of these traits are ruinous.” Candor, intellectual rigor? This rosy view of the academic world is obviously that of an outsider, for academia is rife with obfuscation and intellectual fashions—and with politics. Teachers woo the electorate (the students), who annually vote (fill out teaching evaluations) on performance. Assistant professors wangle for promotion and tenure (tenure is like a safe political seat); old professors just rangle. There are endless committees since, like the House and the Senate, university departments are self-administering. The university administration (White House) tries to steer the faculty (Congress); the faculty stymies these efforts whenever possible. When I watch House of Cards, the plotting and back-stabbing remind me of faculty meetings and search committees, although in the ivory tower nobody actually dies. As Henry Kissinger, who was a Harvard professor for almost 20 years, observed: “University politics are vicious precisely because the stakes are so small.”

In a New York Times op-ed on the failed political career of Michael Ignatieff, the intellectual who had a short-lived stint as leader of Canada’s Liberal party, David Brooks argues that academics are ill-suited to be politicians.“In academia, you are rewarded for candor, intellectual rigor and a willingness to follow an idea to its logical conclusion,” he writes. “In politics, all of these traits are ruinous.” Candor, intellectual rigor? This rosy view of the academic world is obviously that of an outsider, for academia is rife with obfuscation and intellectual fashions—and with politics. Teachers woo the electorate (the students), who annually vote (fill out teaching evaluations) on performance. Assistant professors wangle for promotion and tenure (tenure is like a safe political seat); old professors just rangle. There are endless committees since, like the House and the Senate, university departments are self-administering. The university administration (White House) tries to steer the faculty (Congress); the faculty stymies these efforts whenever possible. When I watch House of Cards, the plotting and back-stabbing remind me of faculty meetings and search committees, although in the ivory tower nobody actually dies. As Henry Kissinger, who was a Harvard professor for almost 20 years, observed: “University politics are vicious precisely because the stakes are so small.”

February 11, 2014

MIESADVENTURE

Mecanoo & Martinez + Johnson

The Washington, DC Public Library System, which is planning a makeover of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library, has released what it calls “preliminary design concepts” by the three architecture firms competing for the job: Studios Architecture and the Freelon Group; Patkau Architects, Ayers Saint Gross, and Krueck + Sexton Architects; and Mecanoo and Martinez+Johnson. The MLK Library (1966) is a late work of Mies van der Rohe, completed after the master’s death in 1969, although designed while he was still active, simultaneously working on the unbuilt Mansion House Square project in London. Usually I don’t like to comment on unbuilt designs, but since the library is built, I will make an exception. The MLK Library is not a masterpiece, but it deserves better than the shabby treatment is receives from Studios and Mecanoo, who place fashionably skewed boxes above (and overlapping) the existing building in feeble attempts to bring excitement to the work of an architect who intentionally avoided excitement. “I don’t want to be interesting, I want to be good,” he once said. Only Patkau seems to have grasped that deference rather than contrast is the right design strategy. (Patkau adds a floor whose design is almost Miesian.) The library has announced that it “will work with community input to develop a redesign.” Commendable but also scary. It requires architectural sophistication to square the circle that is the particular design challenge of this project. Subtlety is not the usual product of public meetings, where the noisiest often prevail. Poor old Mies.

Studios Architecture and the Freelon Group

Patkau Architects, Ayers Saint Gross, and Krueck + Sexton Architects

January 30, 2014

EXAGGERATED INESSENTIALS

The Singh Center for Nanotechnology, designed by Weiss/Manfredi, has received glowing reviews in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Architect, and Architectural Record. But in the rush to praise, the critics have overlooked an important issue. The building is located on the edge of the Penn campus on Walnut Street, which at that point is more of a high-speed motor way than a city street, nevertheless, it is a street, something that the Singh Center barely acknowledges. The building breaks the street face with a wide opening. Not even a city square, it’s mostly grass. It’s true that the University of Pennsylvania occupies a leafy campus, but like most urban universities the green spaces are in secluded, inner environments, not facing the street. It’s hard to know what to make of a front lawn on Walnut Street. It strikes me as a suburban gesture, but then the Singh Center seems ill at ease in its urban surroundings and with its canted, sculptural forms would be more at home on a rural site. The forecourt has another unintended effect: it highlights the façade of the physics building across the street, a distinctly ungainly Brutalist relic of the 1960s. Its facade is visible under the most striking feature of the Singh Center: a 68-foot cantilevered portion of the building. Cantilevered boxes have become a modernist cliché—one thinks of Diller, Scofidio & Renfro’s ICA Building, Williams & Tsien’s Barnes Museum, and Integrated Architecture’s Lamar Corporate Headquarters. Unlike the windmilling terraces of Wright’s Fallingwater, these recent cantilevered boxes are designed merely to impress. “Look what I can do.” As an architect friend of mine commented about the Singh Center, “It seems to me to be an essay in exaggerated inessentials.”

The Singh Center for Nanotechnology, designed by Weiss/Manfredi, has received glowing reviews in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Architect, and Architectural Record. But in the rush to praise, the critics have overlooked an important issue. The building is located on the edge of the Penn campus on Walnut Street, which at that point is more of a high-speed motor way than a city street, nevertheless, it is a street, something that the Singh Center barely acknowledges. The building breaks the street face with a wide opening. Not even a city square, it’s mostly grass. It’s true that the University of Pennsylvania occupies a leafy campus, but like most urban universities the green spaces are in secluded, inner environments, not facing the street. It’s hard to know what to make of a front lawn on Walnut Street. It strikes me as a suburban gesture, but then the Singh Center seems ill at ease in its urban surroundings and with its canted, sculptural forms would be more at home on a rural site. The forecourt has another unintended effect: it highlights the façade of the physics building across the street, a distinctly ungainly Brutalist relic of the 1960s. Its facade is visible under the most striking feature of the Singh Center: a 68-foot cantilevered portion of the building. Cantilevered boxes have become a modernist cliché—one thinks of Diller, Scofidio & Renfro’s ICA Building, Williams & Tsien’s Barnes Museum, and Integrated Architecture’s Lamar Corporate Headquarters. Unlike the windmilling terraces of Wright’s Fallingwater, these recent cantilevered boxes are designed merely to impress. “Look what I can do.” As an architect friend of mine commented about the Singh Center, “It seems to me to be an essay in exaggerated inessentials.”

January 26, 2014

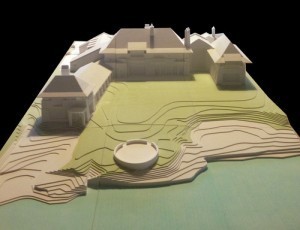

MODELMAKING

3D printer study model (Ike Kligerman Barkley)

Tom Kligerman, of Ike Kligerman Barkley, was showing me his new 3D printer the other day. His firm specializes in high-end houses, mostly though not exclusively traditional in design. Their printer, about the size of a Smart Car, is used to produce iterative study models that are extremely detailed, as if made by a Swiss watchmaker or a particularly obsessive ship-in-the-bottle hobbyist. 3D printers are all the rage in architecture schools. I can see why they’re popular with students. It’s sort of like having an in-house professional modelmaker—he can make even your half-baked efforts look good. But is it a good learning tool? I doubt it. 3D printers are capable of printing anything, buildable or unbuildable, functional or dysfunctional, sensible or nonsensical. It is not that acquiring modelmaking skills makes you a better architect, but the process of building models—like the act of sketching—does teach you about design. It takes several hours to print a complex shape, and I suspect that the demand on 3D printer time in schools will preclude them being used as iterative design tools. They will just make pretty models.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers