Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 29

November 12, 2014

FROM GRITS TO GRANADA

Seaside

I spent a weekend in Seaside, the emblematic small beach town that launched a thousand traditional neighborhood developments. Seaside is now more than thirty years old and looks it—in a good way. It is not merely a question of mature landscaping and weathered materials, but also of the indefinable small adjustments that take place when a place grows into itself. Unexpected things have happened, of course, not least a real estate bonanza. At Seaside, modest wood-frame houses on small lots regularly go for well over a million dollars. A beachside house designed by the late Aldo Rossi—nothing spectacular—is on the market for $11 million. And the town center is a runaway commercial success; it was crowded with people on a Sunday in November, which is not the high season in this part of Florida.

Alys Beach

The architectural influence of Seaside is visible up and down Route 30A, the coastal highway, in houses, roadside eateries, even strip malls. There are also second generation Seaside-type resort developments such as WaterColor, Rosemary Beach and Alys Beach. They make an interesting comparison. WaterColor is a commercialized, scaled-up, mainstream version of Seaside. Both WaterColor and Seaside are riffs on a homegrown Southern vernacular: shady porches, shuttered windows, tin roofs. Think Thornton Wilder, Norman Rockwell, and Frank Capra. Rosemary Beach and Alys Beach, on the other hand, are spicier mixtures. Rosemary Beach is part Caribbean and—weirdly—part Bavarian, with rustic woodwork and steep roofs. Alys Beach is a combination Mediterranean village, Moorish coastal town, with a dash of Casablanca. Stucco walls, patterned tiles, wooden screens, hidden courtyards with trickling fountains. What started in Seaside as an earnest search for roots has turned into a fusion of exotic images that have little to do with a “sense of place,” or, at least with a sense of this actual place. That is unexpected, too.

October 30, 2014

CITY OF TOWERS

There was a Q and A after my Landmark West! lecture on New York’s Upper West Side. One person wanted to know what I thought about the exceptionally tall residential towers that are radically changing Midtown’s skyline. One57, Christian de Portzamparc’s skinny 75-story condominium, under construction on West 57th Street is an example. I’ve written about this new trend. The current phenomenon is a function of globalization and real estate, and has little to do with architecture. But, then, that was always the case with Manhattan. As late as the 1940s, the high-rise real estate development projects of numerous entrepreneurs produced a memorable skyline: animated, varied, and quite beautiful. But that skyline was a happy accident; there was no master plan, no rules, no grand design. This time around, I’m less sure of the outcome.

There was a Q and A after my Landmark West! lecture on New York’s Upper West Side. One person wanted to know what I thought about the exceptionally tall residential towers that are radically changing Midtown’s skyline. One57, Christian de Portzamparc’s skinny 75-story condominium, under construction on West 57th Street is an example. I’ve written about this new trend. The current phenomenon is a function of globalization and real estate, and has little to do with architecture. But, then, that was always the case with Manhattan. As late as the 1940s, the high-rise real estate development projects of numerous entrepreneurs produced a memorable skyline: animated, varied, and quite beautiful. But that skyline was a happy accident; there was no master plan, no rules, no grand design. This time around, I’m less sure of the outcome.

October 19, 2014

SPIRE. NOT.

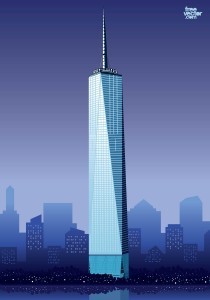

There are many problems with 1, World Center, its brutal and uninspiring silhouette, the rather bland curtain wall (that of 7, World Trade Center, by the same architects (SOM), is much better), its weak-kneed mast. But what scuttles it as a skyscraper is the chamfered geometry of its form. It leads the eye up and down at the same time. Towers should soar; in this one, the upward thrust of one facade is cancelled out by the downward thrust of the next. As a result it looks like an object, rather than a spire.

There are many problems with 1, World Center, its brutal and uninspiring silhouette, the rather bland curtain wall (that of 7, World Trade Center, by the same architects (SOM), is much better), its weak-kneed mast. But what scuttles it as a skyscraper is the chamfered geometry of its form. It leads the eye up and down at the same time. Towers should soar; in this one, the upward thrust of one facade is cancelled out by the downward thrust of the next. As a result it looks like an object, rather than a spire.

October 17, 2014

THE FARGO GIG

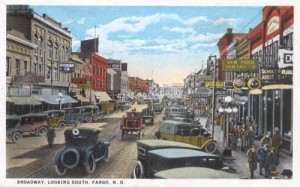

As this postcard shows, downtown Fargo, North Dakota in 1924 was a busy place. Broadway is not as crowded today, but it’s much more lively than when I was here last, more than 20 years ago. The North Dakota energy boom is taking place a two-and-a-half hour drive away, but in some ineffable way the prosperity has trickled down. I am told that real estate values are way up, and apartment builders can’t keep up with demand. The architecture school of North Dakota State University is celebrating its centennial and I am giving a keynote talk tonight at the Fargo Theater. In 1940, Duke Ellington’s orchestra played a gig in Fargo, and the resultant legendary recording is considered one of Duke’s best. I hope I can do even half as well.

As this postcard shows, downtown Fargo, North Dakota in 1924 was a busy place. Broadway is not as crowded today, but it’s much more lively than when I was here last, more than 20 years ago. The North Dakota energy boom is taking place a two-and-a-half hour drive away, but in some ineffable way the prosperity has trickled down. I am told that real estate values are way up, and apartment builders can’t keep up with demand. The architecture school of North Dakota State University is celebrating its centennial and I am giving a keynote talk tonight at the Fargo Theater. In 1940, Duke Ellington’s orchestra played a gig in Fargo, and the resultant legendary recording is considered one of Duke’s best. I hope I can do even half as well.

October 13, 2014

TWINKLE, TWINKLE LITTLE STAR

The on-going public debate about starchitects, in part prompted by my piece in the New York Times, was not elevated by James Russell’s judgement that the debate was “stupid.” Another common reaction was to affirm that the term itself is meaningless—if not actually a put-down. There have always been architectural stars, the critics argue, citing Palladio, or Bernini, or whoever. It is true that there have always been well-known architects, even celebrity architects, but the starchitect phenomenon is different. The term is not a put-down, but an accurate description of a certain (small) category of practitioners today. Moreover, today’s stardom is not analogous to architectural fame in the past. In his interesting new book, The Globalisation of Modern Architecture, the British architect Robert Adam quotes David Chipperfield: “It’s easier to know about architects than architecture. A banker won’t know about architecture but will know that ‘Zaha Hadid’ or ‘Rem Koolhaas’ is a brand.” Moreover, the brand has quantifiable monetary value since it can be measured in terms of increased fund-raising, greater attendance, higher office rents or condo selling prices, or patron satisfaction in the case of campus buildings. In that sense, the starchitect is equivalent to the Hollywood star, an actor whose name on a film proposal makes it bankable. The analogy with Hollywood is useful: not all the best actors are stars, and the stars are not necessarily the best actors. It is not a measure of quality but of name recognition among the moviegoing pubic. So, too, in architecture; starchitects are not necessarily the “best” architects. “To be a starchitect, whether voluntarily or otherwise,” Adam writes, “is to be a global brand, and star architects are chosen to give their brand value to projects.”

The on-going public debate about starchitects, in part prompted by my piece in the New York Times, was not elevated by James Russell’s judgement that the debate was “stupid.” Another common reaction was to affirm that the term itself is meaningless—if not actually a put-down. There have always been architectural stars, the critics argue, citing Palladio, or Bernini, or whoever. It is true that there have always been well-known architects, even celebrity architects, but the starchitect phenomenon is different. The term is not a put-down, but an accurate description of a certain (small) category of practitioners today. Moreover, today’s stardom is not analogous to architectural fame in the past. In his interesting new book, The Globalisation of Modern Architecture, the British architect Robert Adam quotes David Chipperfield: “It’s easier to know about architects than architecture. A banker won’t know about architecture but will know that ‘Zaha Hadid’ or ‘Rem Koolhaas’ is a brand.” Moreover, the brand has quantifiable monetary value since it can be measured in terms of increased fund-raising, greater attendance, higher office rents or condo selling prices, or patron satisfaction in the case of campus buildings. In that sense, the starchitect is equivalent to the Hollywood star, an actor whose name on a film proposal makes it bankable. The analogy with Hollywood is useful: not all the best actors are stars, and the stars are not necessarily the best actors. It is not a measure of quality but of name recognition among the moviegoing pubic. So, too, in architecture; starchitects are not necessarily the “best” architects. “To be a starchitect, whether voluntarily or otherwise,” Adam writes, “is to be a global brand, and star architects are chosen to give their brand value to projects.”

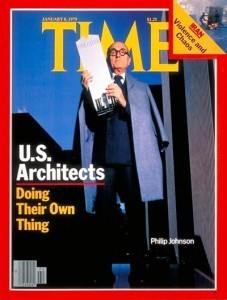

Who was the first brand-name architect? It would surely have been Jørn Utzon, had he not resigned before the Sydney Opera House opened in 1973. My own choice would be Philip Johnson, who graced the cover of TIME magazine (January 8, 1979) with a model of the AT&T building. Most businessmen didn’t know what Johnson stood for (if he stood for anything), but they recognized the name—enough to add value to Gerald Hines’s Johnson-designed real estate development projects. Johnson was a national star. It would not be until 1997 and the opening of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao that a starchitect became a global brand.

September 26, 2014

THE CLEAN-UP CREW

Milstein Hall, an addition to the College of Architecture, Art and Planning at Cornell designed by Rem Koolhaas, received an AIA Honor Award in 2013. The jury commented that “The dramatic insertion of the new program in relationship to the existing buildings and site creates exciting new conditions while posing a series of creative opportunities for future uses and artistic additions by the college.” I was in the building earlier this week to give a lecture, and I must admit that I was puzzled by the award. The boxy wing makes an awkward appendage to the old building. The Crown Hall-like studio seemed adequate if a little impersonal, although it raises the question—as Mies’s building does—of why a studio requires a column-free space, with the attendant structural complexity and cost. At $1,100 psf, Milstein is an expensive building, though the money does not appear to have been spent on details and materials, which are spartan. It was spent on a dramatic (the jury was right there) 48-foot cantilever that projects the building over the street—but to what end? Inside, there is a crit area in a cavelike space that, like most caves, has spectacular echoes. As for the auditorium, it was not a pleasant room in which to lecture. The seats are steeply raked, which is normally effective, but separated from the podium by a large flat area of seats, which acts as a sort of no-man’s land, since no student will sits there. Apparently the flat floor conceals a conference room (for the university board) that emerges from beneath at the push of a button. It’s hard to imagine that this was really the most convenient solution. Any more than designing an auditorium that is surrounded by glass walls. But then so much about this idiosyncratic building defies logic. “Typically, after Koolhaas finishes his design, a sort of clean-up crew comes in and sorts out the problems,” I was told. Maybe they should have gotten the award.

Milstein Hall, an addition to the College of Architecture, Art and Planning at Cornell designed by Rem Koolhaas, received an AIA Honor Award in 2013. The jury commented that “The dramatic insertion of the new program in relationship to the existing buildings and site creates exciting new conditions while posing a series of creative opportunities for future uses and artistic additions by the college.” I was in the building earlier this week to give a lecture, and I must admit that I was puzzled by the award. The boxy wing makes an awkward appendage to the old building. The Crown Hall-like studio seemed adequate if a little impersonal, although it raises the question—as Mies’s building does—of why a studio requires a column-free space, with the attendant structural complexity and cost. At $1,100 psf, Milstein is an expensive building, though the money does not appear to have been spent on details and materials, which are spartan. It was spent on a dramatic (the jury was right there) 48-foot cantilever that projects the building over the street—but to what end? Inside, there is a crit area in a cavelike space that, like most caves, has spectacular echoes. As for the auditorium, it was not a pleasant room in which to lecture. The seats are steeply raked, which is normally effective, but separated from the podium by a large flat area of seats, which acts as a sort of no-man’s land, since no student will sits there. Apparently the flat floor conceals a conference room (for the university board) that emerges from beneath at the push of a button. It’s hard to imagine that this was really the most convenient solution. Any more than designing an auditorium that is surrounded by glass walls. But then so much about this idiosyncratic building defies logic. “Typically, after Koolhaas finishes his design, a sort of clean-up crew comes in and sorts out the problems,” I was told. Maybe they should have gotten the award.

September 20, 2014

THE EVER-PRESENT PAST

McEvoy Ranch, Marc Appleton, architect.

I am speaking at an architectural conference in Charleston. The participants are architects who design custom houses, and many of the presentations highlght the difference between traditional and modern design, since so many custom houses fall into the first category. At one point, a member of the audience (somewhat impatiently) points out that if this were a meeting of fashion designers, or industrial designers, the distinction would not arise; the implication is that we would be discussing only “the latest thing.” Of course, I thought to myself, that’s because fashion and consumer products are so fleeting. There is no tradition of the laptop; when a new model come along, the old model is out of date, soon obsolete, finally discarded. The cars of our youth are long gone. What our grandparents were wearing a century ago is of no concern except to historians, it is what people are wearing today that interests us. But houses have a useful life that is measured in centuries. Old houses are a part of the present. This means that domestic traditions change slowly. The symbolic hearth goes back to the Middle Ages; Americans have built porches of one kind or another ever since Mount Vernon; the front door has been a potent symbol for a long time. Old houses are cherished, so little wonder that for many people, building one’s house means participating in—and adding to—a long tradition.

September 4, 2014

DIGGING DEEP

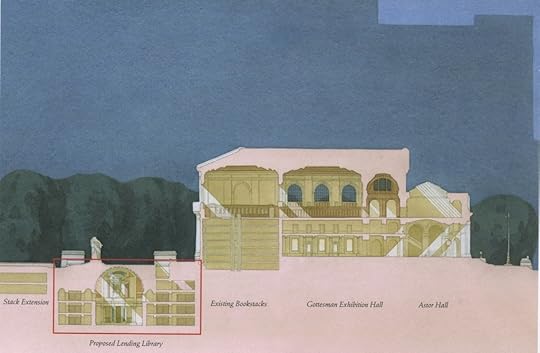

Peter Pennoyer and Sam Roche have recently unveiled a counterproposal for expanding the New York Public library that preserves the stacks intact and extends the library underneath the Terrace in Bryant Park. Many will be caught up short by the architectural style of the addition which is as unlike the Foster + Partners proposal as oil and water. Critics of the Foster design likened its slick but characterless atmosphere to that of a chain bookstore. Well, the Pennoyer/Roch design certainly doesn’t look like a store, unless it is the late-lamented Scribners Bookstore on Fifth Avenue. More important is that the scheme shows a alternative strategy to enlarging Carrère & Hastings’ masterpiece. Building beneath the Terrace, and adding a floor to the existing stacks beneath the park itself, creates a total area for the entire library of 873,000 SF, compared to only 593,000 SF in the Foster scheme. This exceeds the current total area of the Schwarzman Building, the Mid-Manhattan Library, the Science, Industry and Business Library, and the Bryant Park Stacks (808,000 SF). The cancellation of the Foster proposal opens the door to more such innovative thinking.

Peter Pennoyer and Sam Roche have recently unveiled a counterproposal for expanding the New York Public library that preserves the stacks intact and extends the library underneath the Terrace in Bryant Park. Many will be caught up short by the architectural style of the addition which is as unlike the Foster + Partners proposal as oil and water. Critics of the Foster design likened its slick but characterless atmosphere to that of a chain bookstore. Well, the Pennoyer/Roch design certainly doesn’t look like a store, unless it is the late-lamented Scribners Bookstore on Fifth Avenue. More important is that the scheme shows a alternative strategy to enlarging Carrère & Hastings’ masterpiece. Building beneath the Terrace, and adding a floor to the existing stacks beneath the park itself, creates a total area for the entire library of 873,000 SF, compared to only 593,000 SF in the Foster scheme. This exceeds the current total area of the Schwarzman Building, the Mid-Manhattan Library, the Science, Industry and Business Library, and the Bryant Park Stacks (808,000 SF). The cancellation of the Foster proposal opens the door to more such innovative thinking.

August 17, 2014

ALL THAT JAZZ

B35 Lounge Chair

Marcel Breuer, des., Thonet, manf., 1928-29

I’ve been researching Marcel Breuer in connection with a new book. The 18-year-old Breuer started as an art student in Vienna, then transferred to the new Bauhaus in Weimar. He chose the woodworking program, and proved to be so talented in furniture design that after he graduated Walter Gropius invited him back to be the master of the woodworking shop. In one short period, 1925-30, Breuer designed some of the seminal modernist chairs of the twentieth century: the Wassily, the Cesca, the B35 lounge chair. During the 1930s, he started working as an architect, collaborating with F.R.S. Yorke in UK and Gropius in the US, and finally working on his own. What is striking is that Breuer moved so effortlessly from designing chairs to designing buildings. This is explained in two ways. Breuer had completely absorbed Gropius’s teaching that design was a universal discipline, that is, if you could design a teacup you could design a city. So having no formal training in building design or construction whatsoever (the Bauhaus did not teach architecture until long after Breuer was there), did not discourage him from undertaking building commissions. The second reason is that modernist architects were inventing as they went along; they did not rely on history, traditional construction, or conventional building practice. Hence, the lack of training was not a liability. Just as a tubular steel lounge chair had no precedent, so too a glass and concrete building was breaking new ground. It was all new.

Of course, such an improvised art could not last. By the late 1950s, as modernism became an academically entrenched discipline—instead of an avocation—it began to show signs of flagging. You can’t really teach improvisation, any more than you can teach jazz. Neither modern jazz nor modern architecture survived.

August 6, 2014

THE IKE MEMORIAL, CONT’D.

A New York Times story described a recent report of the House Natural Resources Committee criticizing the commission that is in charge of building the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, D.C. But the Times didn’t mention, as the Washington Post did, that the Congressional committee has not actually voted on the report, which was released by the Republican majority. Moreover, according to Martin Pederson, editor of Metropolis, the report is the work of a single staffer. The Times headline was Memorial Plan Called a ‘Five-Star Folly’. “If you read the Times account, you would have been led to the incorrect conclusion that the House Committee had called the Gehry design a ‘five-star folly,”” writes Pederson. “No, a subcommittee staffer with a clear ideological agenda crafted that epithet.” The Times article has two interesting bits of information. According to the article “The report also criticizes the design selection process, asserting that the panel chose Mr. Gehry’s approach over the objections of the design jury, which had characterized his proposal as ‘mediocre.’” If true, this would be extremely unusual, and throws a poor light on the commission; it sounds like a canard to me. The Times also quoted a statement released by Frank Gehry that includes the revelation that “I personally have done all my design work pro bono.” Given all the opprobrium that has been heaped on Mr. Gehry, it is a touching admission.

A New York Times story described a recent report of the House Natural Resources Committee criticizing the commission that is in charge of building the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, D.C. But the Times didn’t mention, as the Washington Post did, that the Congressional committee has not actually voted on the report, which was released by the Republican majority. Moreover, according to Martin Pederson, editor of Metropolis, the report is the work of a single staffer. The Times headline was Memorial Plan Called a ‘Five-Star Folly’. “If you read the Times account, you would have been led to the incorrect conclusion that the House Committee had called the Gehry design a ‘five-star folly,”” writes Pederson. “No, a subcommittee staffer with a clear ideological agenda crafted that epithet.” The Times article has two interesting bits of information. According to the article “The report also criticizes the design selection process, asserting that the panel chose Mr. Gehry’s approach over the objections of the design jury, which had characterized his proposal as ‘mediocre.’” If true, this would be extremely unusual, and throws a poor light on the commission; it sounds like a canard to me. The Times also quoted a statement released by Frank Gehry that includes the revelation that “I personally have done all my design work pro bono.” Given all the opprobrium that has been heaped on Mr. Gehry, it is a touching admission.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers