Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 32

January 22, 2014

GOOD FOOTBALL, SLOW TRAINS

Rose Bowl Parade

I am not a football fan, but I inevitably watch the end of games on many a Sunday evening, waiting for CBS to broadcast 60 Minutes. It is a brutal, plodding game, the players marching the ball up and down the field, a yard at a time, with the occasional flurry of a long pass or a field goal. A game of armored might, the players resembling Roman centurions, with little of the finesse and speed of basketball or hockey. Nevertheless, I’m always impressed by the power and energy of the football business—the players and coaches, the referees, the commentators. I am also impressed that everything stops for football—including 60 Minutes. So many resources are devoted to this spectacle: college athletic programs, publicly-built stadiums, nationally-broadcast games, the urban spectacle of the Bowl parades. And, except for the rare players’ strike, it all runs smoothly. I think of this whenever I take Amtrak; slow, often late, rarely on time. American know-how was once globally admired. No more. In fields like transportation we are no longer the leaders, in some field—education, health—we spend more than anyone and get less. The big exceptions are entertainment and professional sports. Go Eagles.

January 15, 2014

B-SCHOOL SHUFFLE

Yale School of Management (photo by Chuck Choi)

A new building for Yale’s School of Management designed by Norman Foster was formally opened on January 9. New B-school facilities are sprouting like ragweed, not only in the United States but globally. The reason is not hard to find. Their alumni are among the richest on the planet, and demand for MBAs and business degrees has skyrocketed. The best schools want to improve their facilities; the newcomers want to jump on the bandwagon, and a fancy new building helps to attract students. Virtually all of these buildings are the work of prominent architects such as Norman Foster (Imperial College, London), David Chipperfield (HEC, Paris), and David Adjaye (Skolkovo, Moscow). The go-to firm in the U.S. is Robert A. M. Stern Architects, which has designed no less than a dozen B-schools, including at Harvard, the University of Virginia, and Rice. Most RAMSA business schools are traditional in style, although several (Drexel, Penn State, Ithica College) are best described as transitional—modern but not too modern. Berkeley (Moore Ruble Yudell) and Temple (Michael Graves) built PoMo buildings, although few B-schools have followed their lead. Most have opted for traditional, transitional (KPF at Wharton and Michigan), or mainstream modern (Rafael Viñoly at the University of Chicago and the University of South Carolina). KPF is edgier at Florida International and Arizona State, Enrique Norten is cooly minimalist at Rutgers. And Frank Gehry is Frank Gehry at Case Western Reserve. Not to be outdone, Columbia’s B-school announced that Diller, Scofisio & Renfro, darling of the critics, will design their new home. For a while, RAMSA set the pace with its traditional designs, but Foster at Yale may signal a new design trend among B-schools. The classrooms are contained in drum-like volumes that surround an enclosed courtyard, creating the impression of an elegant high-tech watering hole. A fitting lair for the wolf pups of Wall Street.

January 10, 2014

DEMO OR NOT DEMO

Portland Building (Michael Graves, arch.) 1982

From the ball and chain desk.

The recent demolition of Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Hospital, and the announced demolition of Williams & Tsien’s Folk Art Museum, raises the vision—or specter, depending on your point of view—of future demolitions of not-so-old buildings. What happened to the preservation of the past? I have always believed that the undoubted popularity of the historic preservation movement depends less on some abstract notion of heritage conservation and more on the actual architecture being preserved: in the past, that has meant the well-built, well-designed, and much cherished buildings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Now that mid-century modern buildings are coming under the wrecker’s ball, the question becomes more complex. Many of these buildings are not well-built, are cavalierly planned, and are definitely not cherished by the public—some are actively disliked. They are also designed differently. Traditionally, buildings were meant to be durable, not merely physically but aesthetically. That implied a degree of conservatism when it came to design, eschewing the latest fashion, and leaning on past precedents. When architects cut the cord to the past, and focus only on the here-and-now, architecture becomes more exciting and more fashionable, but it also becomes shorter-lived. Rough concrete, googly shapes, oval windows, and built jokes age as badly as hula hoops and pet rocks. No wonder that preservationists have a hard time garnering public support for Brutalist architecture. And postmodernism is next. The Portland City Council is considering whether to demolish the Portland Building, a postmodern landmark by Michael Graves that requires the infusion of $95 million in repairs and improvements. (No one is suggesting destroying Ray Kaskey’s wonderful statue, though.) And one can imagine what will happen in a few years when deconstructivist buildings, many of which are exceedingly poorly built as well as distinctly oddly designed, are put on the block. Spend money fixing them up, or write them off as a bad architectural moment? Expect opposition, outrage—and more demolitions.

January 2, 2014

BE IT EVER SO HUMBLE

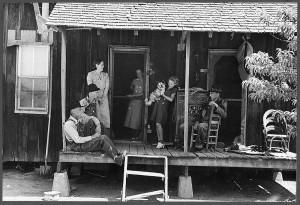

Sharecroppers on porch, Missouri, 1938 (Russell Lee)

The Atlantic’s website “Cities” argues that some urbanist buzzwords should be retired, including placemaking, gentrification, and smart growth. A good proposal, even if the Atlantic is itself responsible for the proliferation of many the self-same buzzwords—the website is subtitled “Place Matters.” Buzzwords are everywhere. Trouble in the Iraq war—what we need is a surge. No sooner did Obamacare falter than we learned that there were navigators, who would fix the problem. The right buzzword comes first; reality will follow. Buzzwords seem to emerge from two considerations: marketing and media. If you have an untested idea or hypothesis, such as smart growth or creative class, providing a label, preferably a catchy label, gives the idea an air of legitimacy. After all, if it has a name, it must be real. In our Twitter culture, a colorful name also saves time in lengthy explanations. This appeals to the media, since a new name can stand in for actual news. Would Occupy Wall Street, or the Tea Party, have gotten as much coverage without a colorful name? Which brings me back to the Atlantic list. Placemaking is a term often used by architects and urban designers, and it implies that a sense of place (obviously a good thing) can replace a sense of placelessness (a bad thing), if only the design suggestions of the self-styled placemakers are followed. But is a sense of place really a function of design? It may be for the tourist or the stranger, who experiences places briefly. Nothing is as disappointing to the tourist as visiting a place that looks like other places, and most of the American built environment is superficially similar. But as the late J. B. Jackson long ago pointed out, that environment is full of meaning, for those who use it. A strip mall may not look like much as you drive by, but for someone that attends the Judo school, or goes regularly to the beauty salon, it is a real place. Conversely, most attempts to instill a sense of place through physical design end up looking like themed restaurants with ersatz “mementos” on the walls. (The most blatant of these is the “Cheers” airport pub chain.) I shop in a banal Pathmark, but I recognize some of the staff, I know where things are, it is familiar. The supermarket has a small place in my life, among the stirring places (the concourse of 30th Street station), the lyrical places (the Wissahickon), and the cherished places (our house). The old folk adage puts it well: Be it ever so humble, there is no place like home.

December 29, 2013

DESIGN DREAMS

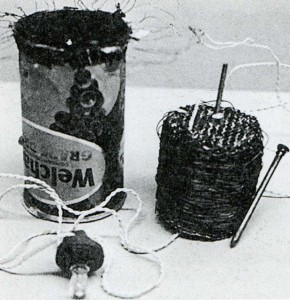

Tin-can radio designed by Victor Papanek

“I really do believe that the world can be saved through design, and everything needs to actually be ‘architected,’ ” Kanye West recently told Harvard students in a widely-repeated quote. Architects especially loved it, but Lucas Verweij, a Berlin-based writer, argues in Dezeen that claims such as West’s are excessive. Verweij writes that the expectations placed on design—“design can solve the smog problem in Beijing, the landmine problems in Afghanistan and huge social problems in poor parts of Western cities”—are overblown and cannot be met. “We are in a design bubble,” he writes, “it’s a matter of time before it will burst.” I’m not sure about the bubble—it seems more like a passing fashion to me—but the current idea that every problem is fodder for the design profession is certainly misguided. Can a designer really be master of all trades? The proposition that design can be effective at all scales dates back to Walter Gropius, who claimed that the designer could assume broad responsibilities, from a teacup to a city was how he put it. (Grope’s teacups are OK, his urbanism, not so much.) But design is primarily about the how; the what is determined by a host of circumstantial conditions—social, economic, and cultural—over which the designer exercises no authority. More than 40 years ago, Victor Papanek, a Viennese-born industrial designer, wrote Design for the Real World, in which he made the case for design-as-problem-solving as opposed to design-as-styling. It was compelling stuff—I remember a Third World transistor radio housed in a can, run by candle-power. But were such radios ever produced? The forces of globalism ensured that it was the cell phone, not the the tin-can radio, that revolutionised the world, including the Third World. And the revolutionary aspects of the cell phone are the work of engineers, not industrial designers. The much-vaunted “design” of Apple products, for example, is chiefly (obsessively) minimalist packaging. Pace Papanek.

December 26, 2013

MARKETING AND INVENTION

Placing the cornerstone of the Ecol house, Ste. Anne-de-Bellevue, June, 1972. From left to right, Salama Saad, Witold Rybczynski, Arthur Acheson, Samir Ayad, and Wajid Ali.

I watched a PBS Newshour segment last night on Singularity University. Well-named, this really is a singular organization of the sort that only California can spawn—where is Evelyn Waugh when we need him? Singularity is an unaccredited university, that is, it doesn’t give degrees and it has no student body, although it does have faculty, some of whom appeared on the program, interviewed by Paul Solman. It’s obviously liberating to be a professor without the irksome burden of students, for they were all remarkably happy, relaxed, upbeat types. In fact, they reminded me more of cheerful marketers than academics, and what they were selling was an optimistic vision of the future. It was unclear if the visionary technologies described by these self-styled creative thinkers actually existed. But “pushing the frontiers of human progress through innovation and emerging technologies” was apparently good enough for the Newshour. In an earlier life, I used to be a university researcher, looking for ways to make building materials out of recycled industrial waste. We rarely elicited the interest of the media—it was the 1970s, when news still meant hard news—in any case, we were more interested in doing the work than talking about it. Obviously, we had things backward. We didn’t realize that the trick is to promote now, and invent later.

December 21, 2013

FUNNY NAMES

Blue House, London (FAT)

London architecture office FAT has announced that it will shut down its studio next summer, after “exploring the potential of the projects as much as possible,” reported Dezeen. (Architectural firms like FAT don’t have offices, they have studios.) One less funny-name, I thought to myself. The big boys and girls—Foster, Gehry, Safdie, Stern, Hadid—simply use the name of the principal, as architects have always done. Piano adds “Building Workshop,” which is a harmless enough affectation. Presumably, their buildings speak for themselves. Indulging oneself in a catchy, or at least memorable, moniker, is partly an attempt to stand out from the crowd, and partly a branding tactic: We are not simply a business, we are hip, artistic, creative. Hence names such as Morphosis, Asymptote, and Snøhetta, or the more outrageous BIG, MAD, and FAT. Interestingly, I can’t think of a classicist firm that has adopted either faceless initials, or a funny name. Greenberg, Porphyrios, Simpson, and Appleton, follow the old convention. But perhaps that is a part of their brand: We aren’t chic or fashionable, we just deliver buildings, the old-fashioned way.

WHAT’S IN A NAME II?

Blue House, London (FAT)

London architecture office FAT has announced that it will shut down its studio next summer, after “exploring the potential of the projects as much as possible,” reported Dezeen. (Architectural firms like FAT don’t have offices, they have studios.) One less funny-name, I thought to myself. The big boys and girls—Foster, Gehry, Safdie, Stern, Hadid—simply use the name of the principal, as architects have always done. Piano adds “Building Workshop,” which is a harmless enough affectation. Presumably, their buildings speak for themselves. Indulging oneself in a catchy, or at least memorable, moniker, is partly an attempt to stand out from the crowd, and partly a branding tactic: We are not simply a business, we are hip, artistic, creative. Hence names such as Morphosis, Asymptote, and Snøhetta, or the more outrageous BIG, MAD, and FAT. Interestingly, I can’t think of a classicist firm that has adopted either faceless initials, or a funny name. Greenberg, Porphyrios, Simpson, and Appleton, follow the old convention. But perhaps that is a part of their brand: We aren’t chic or fashionable, we just deliver buildings, the old-fashioned way.

December 10, 2013

THE CHARLOTTESVILLE TAPES

The Charlottesville Tapes is well worth a second read. In 1983, Jaquelin T. Robertson, then architecture dean at the University of Virginia, brought together two dozen architects to a private two-day confab (pointedly, no critics or historians were invited, only practitioners). It was a heavyweight group, a mixture of American, European, and Japanese architects, among them nine future Pritzker Prize winners, and four future Driehaus laureates. Each participant presented one project; discussion followed. The book is an edited version of the conversations. Reading the lively exchanges, one can only reflect on how much has changed since. Several of the participants (Philip Johnson, Paul Rudolph, Charles Gwathmey, O. M. Ungers, Carlo Aymonino) are deceased. Some reputations have risen (Toyo Ito, Tadao Ando), some have not (Kevin Roche, Cesar Pelli). Some of the tyros, like Rem Koolhaas and Robert A. M. Stern, have become household names. Stern presented a Jeffersonian dining hall at UVA—few would have guessed its traditional style would herald a comeback of classicism. Thirty years ago, postmodernism was in full bloom with Michael Graves the man of the hour. Not all the participants at the conference were as well-known: Frank Gehry was still building houses, and Léon Krier wasn’t building anything at all. Much of the discussion centered on urban design. On this point, Robertson was not sanguine: “I have real doubts that the kind of media-hyped, consumer-oriented pluralism that we have today will in fact produce an elegant or an equitable urban environment,” he wrote. Perhaps that was too bleak. The new urbanist movement had yet to appear, and Battery Park City, Celebration, and Poundbury were in the cards. So were iconic buildings such as the Bilbao Guggenheim and the Seattle Public Library, which would influence city development. But Robertson was right: as city building in China and the Gulf would conclusively show, good urbanism remains contemporary architecture’s Achilles heel.

The Charlottesville Tapes is well worth a second read. In 1983, Jaquelin T. Robertson, then architecture dean at the University of Virginia, brought together two dozen architects to a private two-day confab (pointedly, no critics or historians were invited, only practitioners). It was a heavyweight group, a mixture of American, European, and Japanese architects, among them nine future Pritzker Prize winners, and four future Driehaus laureates. Each participant presented one project; discussion followed. The book is an edited version of the conversations. Reading the lively exchanges, one can only reflect on how much has changed since. Several of the participants (Philip Johnson, Paul Rudolph, Charles Gwathmey, O. M. Ungers, Carlo Aymonino) are deceased. Some reputations have risen (Toyo Ito, Tadao Ando), some have not (Kevin Roche, Cesar Pelli). Some of the tyros, like Rem Koolhaas and Robert A. M. Stern, have become household names. Stern presented a Jeffersonian dining hall at UVA—few would have guessed its traditional style would herald a comeback of classicism. Thirty years ago, postmodernism was in full bloom with Michael Graves the man of the hour. Not all the participants at the conference were as well-known: Frank Gehry was still building houses, and Léon Krier wasn’t building anything at all. Much of the discussion centered on urban design. On this point, Robertson was not sanguine: “I have real doubts that the kind of media-hyped, consumer-oriented pluralism that we have today will in fact produce an elegant or an equitable urban environment,” he wrote. Perhaps that was too bleak. The new urbanist movement had yet to appear, and Battery Park City, Celebration, and Poundbury were in the cards. So were iconic buildings such as the Bilbao Guggenheim and the Seattle Public Library, which would influence city development. But Robertson was right: as city building in China and the Gulf would conclusively show, good urbanism remains contemporary architecture’s Achilles heel.

December 4, 2013

FANNING THE EMBERS

“Tradition does not mean guarding the ashes, but fanning the embers,” observed Benjamin Franklin; similar quotations are attributed to Thomas More and Gustav Mahler. Guarding the ashes puts old fogies in their place, and fanning the embers nicely catches the sense of an active involvement with the past. One looks in vain for such involvement in much of today’s architecture. Too many architects have embraced novelty as the sine qua non of new work, perhaps under the mis-impression that they are designing products rather than buildings. But while the life of an iPhone is too short for the novelty to ever wear off, a few years at most, the life of buildings is not measured in years but in centuries. A building that merely offers the new-new thing, quickly become old-fashioned, or worse, out of fashion. Buildings that fan the embers of the past, by contrast, incorporate rich layers of meaning. During a recent visit to Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum, the interior with its vaulted ceilings reminded me both of older art galleries and of ancient architecture. Because Kahn ignored the fashions of his day, his building continues to look fresh; because he observed the old conventions—symmetry, axes, a structural grid, top-light—his building suggests several time dimensions: today, 1972 when it was built, and a long, long time ago.

“Tradition does not mean guarding the ashes, but fanning the embers,” observed Benjamin Franklin; similar quotations are attributed to Thomas More and Gustav Mahler. Guarding the ashes puts old fogies in their place, and fanning the embers nicely catches the sense of an active involvement with the past. One looks in vain for such involvement in much of today’s architecture. Too many architects have embraced novelty as the sine qua non of new work, perhaps under the mis-impression that they are designing products rather than buildings. But while the life of an iPhone is too short for the novelty to ever wear off, a few years at most, the life of buildings is not measured in years but in centuries. A building that merely offers the new-new thing, quickly become old-fashioned, or worse, out of fashion. Buildings that fan the embers of the past, by contrast, incorporate rich layers of meaning. During a recent visit to Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum, the interior with its vaulted ceilings reminded me both of older art galleries and of ancient architecture. Because Kahn ignored the fashions of his day, his building continues to look fresh; because he observed the old conventions—symmetry, axes, a structural grid, top-light—his building suggests several time dimensions: today, 1972 when it was built, and a long, long time ago.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers