Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 35

August 22, 2013

MAKE A STATEMENT

Craig Ellwood, South Bay Bank, Manhattan Beach, CA (1956)

I came across a term new to me in an architectural magazine today. The writer was speculating about whether Jeff Bezos would have an influence on the design of the new headquarters of the Washington Post. “One question is whether the newspaper’s new owner wants a statement building,” he wrote. A statement building! It struck me as a sad commentary on the present state of architecture that what at one time would have been called simply good design had now been elevated to the status of a “statement.” And a statement of what? The architectural equivalent of a designer label: I am a Gehry, I am a Hadid, I am a Foster? A ratification of the status of the client: I am rich, I am special, I am not run-of-the-mill? Or a corporate message: we value design, we are green, we are on the cutting edge? It is times like this that I miss the certainties of mid-century modernism, when it was sufficient for a building–whether it was a corporate office, a house, or a bank–to merely exhibit structural and functional logic, clean but not labored details, and a modest range of materials. If there was a statement here it was simply “I am modern.”

August 16, 2013

THE CREATIVE ACT

I recently watched Intersection, a 1994 flick with Richard Gere and Sharon Stone cast as a husband-wife architect team. We know that Gere is a creative soul–he has long, unruly hair–and that he is financially successful and glamorous–he wears Armani and drives a classic Mercedes 280SL. Stone, oddly cast as an ice queen, runs the business. So far, so good. The setting is Vancouver. The director, Mark Rydell, enlists Arthur Erickson’s Museum of Anthropology (actually almost two decades old, but looking great) as a stand-in for Gere/Stone’s latest architectural triumph. But except for a scene where Gere throws a temper tantrum on a building site, there is nothing in this film to suggest how an architect actually creates. On reflection, I can’t think of a movie that does so successfully; not Two for the Road (although Albert Finney is appropriately self-absorbed), not Towering Inferno nor Sleepless in Seattle, and definitely not Death Wish. Admittedly, it’s difficult to portray cinematically how the various demands of a project come together in the mind of a designer–but Gere staring intently at a maquette doesn’t quite cut it. My gold standard for portraying creativity is the deathbed scene in Amadeus, in which director Miloš Forman manages to capture the mystery of musical composition. Not that what he portrays is necessarily the way that composers compose, but watching Hulce/Mozart and Abraham/Salieri we get an insight into what it might be like to hear music in your head. As for Intersection, it bombed at the box-office, and I’m afraid hasn’t improved with time.

I recently watched Intersection, a 1994 flick with Richard Gere and Sharon Stone cast as a husband-wife architect team. We know that Gere is a creative soul–he has long, unruly hair–and that he is financially successful and glamorous–he wears Armani and drives a classic Mercedes 280SL. Stone, oddly cast as an ice queen, runs the business. So far, so good. The setting is Vancouver. The director, Mark Rydell, enlists Arthur Erickson’s Museum of Anthropology (actually almost two decades old, but looking great) as a stand-in for Gere/Stone’s latest architectural triumph. But except for a scene where Gere throws a temper tantrum on a building site, there is nothing in this film to suggest how an architect actually creates. On reflection, I can’t think of a movie that does so successfully; not Two for the Road (although Albert Finney is appropriately self-absorbed), not Towering Inferno nor Sleepless in Seattle, and definitely not Death Wish. Admittedly, it’s difficult to portray cinematically how the various demands of a project come together in the mind of a designer–but Gere staring intently at a maquette doesn’t quite cut it. My gold standard for portraying creativity is the deathbed scene in Amadeus, in which director Miloš Forman manages to capture the mystery of musical composition. Not that what he portrays is necessarily the way that composers compose, but watching Hulce/Mozart and Abraham/Salieri we get an insight into what it might be like to hear music in your head. As for Intersection, it bombed at the box-office, and I’m afraid hasn’t improved with time.

August 12, 2013

CORPORATE HOMES

Microsoft campus, Seattle

In the midst of the astonishing sale of the Washington Post to Jeff Bezos, a related announcement has received less attention: the newspaper will be getting a new home. Developers have been invited to make proposals, and while the final choice has not yet been made (and given the sale of the paper, who knows?), some of the alternatives have been made public. The architects include the usual megafirm suspects, and the designs are equally predictable–buildings for anybody, anyplace. What a difference when the Chicago Tribune held a well-publicized architectural competition in the 1920s for its home, and Eliel Saarinen, Walter Gropius, and Bruno Taut were among the entrants. That was a time when corporations sought to present themselves to the public through adventurous architecture–think Woolworth, Singer, Chrysler, RCA. Sometimes this strategy backfired (PanAm, CBS, AT&T), but when it succeeded it produced masterworks such as Wright’s Johnson Wax, Mies’s Seagram, SOM’s Lever House, and Saarinen’s General Motors Technical Center and the John Deere headquarters. Pepsi Cola, Bell Labs, IBM, and Union Carbide built exceptional buildings, too. In fact, a list of leading mid-century corporate patrons reads like the Fortune 500. One would be hard put to compile a comparable list today. None of our largest new corporations–Google, Microsoft, Intel, Dell, Amazon–would be on it. Exceptions: Facebook has hired Frank Gehry to design an addition to its campus, and Apple is building a high-tech donut designed by Norman Foster. But most of today’s technology companies appear content to occupy the safe architectural middle ground. Is it that buildings really don’t matter to them? Or are they sending the message: we’re not elitists, we’re one of the crowd, we’re just like you. Mr. Bezos, the new boss, could change that.

August 7, 2013

OFF LIMITS

Andrés Duany takes issue in Architectural Record with Michael Sorkin’s review of Landscape Urbanism and Its Discontents. But the problem with a compilation of 20 essays by many different authors is that it rarely presents a coherent argument, so almost anything you say about such a book is (sort of) true. Although this is a sanctioned new urbanist collection, the contributors present a variety of–sometimes contradictory–views. Some admire the High Line, some don’t; some are still fighting a rear-guard action against the modern movement, some aren’t; some see landscape urbanism as the enemy, some don’t. Doug Kelbaugh and Dan Solomon take the sensible position that there is room enough for everyone; Jim Kunstler, spirited as usual, calls landscape urbanism a “lame defense of the bankrupt old mandarin ideology,” which is almost as good as Leon Krier’s blurb: “old modernist wine presented in new greenwashed bottles.” Michael Dennis makes a more telling criticism. “I have not seen, or heard of, any urbanism from so-called Landscape Urbanists . . . I have seen some (occasionally) good urban landscape designs, but mostly they are on the edge of urban contexts–waterfronts, etc.” Duany, who is co-editor of this collection, also makes a valid point that Sorkin does not address. All those swales, water gardens, and native plantings, that are a staple of landscape urbanism–and “green” landscapes in general–are invariably off limits to the public, which is forbidden to walk on them. This is in sharp contrast to the Olmstedian tradition, where absolutely no part of a park is inaccessible. That is the great weakness of landscape urbanism; so much of it seems designed to be photographed rather than used.

Andrés Duany takes issue in Architectural Record with Michael Sorkin’s review of Landscape Urbanism and Its Discontents. But the problem with a compilation of 20 essays by many different authors is that it rarely presents a coherent argument, so almost anything you say about such a book is (sort of) true. Although this is a sanctioned new urbanist collection, the contributors present a variety of–sometimes contradictory–views. Some admire the High Line, some don’t; some are still fighting a rear-guard action against the modern movement, some aren’t; some see landscape urbanism as the enemy, some don’t. Doug Kelbaugh and Dan Solomon take the sensible position that there is room enough for everyone; Jim Kunstler, spirited as usual, calls landscape urbanism a “lame defense of the bankrupt old mandarin ideology,” which is almost as good as Leon Krier’s blurb: “old modernist wine presented in new greenwashed bottles.” Michael Dennis makes a more telling criticism. “I have not seen, or heard of, any urbanism from so-called Landscape Urbanists . . . I have seen some (occasionally) good urban landscape designs, but mostly they are on the edge of urban contexts–waterfronts, etc.” Duany, who is co-editor of this collection, also makes a valid point that Sorkin does not address. All those swales, water gardens, and native plantings, that are a staple of landscape urbanism–and “green” landscapes in general–are invariably off limits to the public, which is forbidden to walk on them. This is in sharp contrast to the Olmstedian tradition, where absolutely no part of a park is inaccessible. That is the great weakness of landscape urbanism; so much of it seems designed to be photographed rather than used.

August 5, 2013

STU

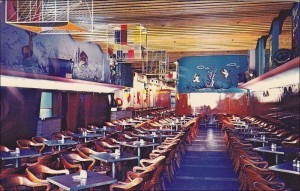

St. Regis Tavern, Montreal, 1960s.

Some architecture students had Louis Kahn, or Paul Rudolph, or Jose Luis Sert; I had Stuart A. Wilson. He taught the third-year design studio of McGill’s six-year course. His class was famous–or infamous–as a sort of boot camp. A grueling boot camp: students regularly repeated that year; some dropped out altogether, following his advice that they would be better off in another field. Wilson gave all sorts of design assignments: book jackets, posters, graphics, as well as hands-on exercises conducted in the carpentry shop, his private domain. The semester-long design problem required each student to build a large scale framing model of their project at 1/2 inch to a foot–every stud and joist in place–and to prepare a complete set of construction drawings. Wilson insisted that architecture was grounded in construction–”Art, fart” was a favorite saying. He was a relentless design critic, sardonically probing, gruffly puncturing youthful pretense, all the while dribbling cigarette ash onto the hapless victim’s drawing. At the same time he was the most accessible of teachers, always available for long conversations, ready with book recommendations–he seemed to have read everything. These talks often took place late at night, for he seemed to live in his office, which had a sleeping loft. He was rumored to have had several wives, the accumulated alimony obligations accounting for his unusual living arrangement, at least according to student lore which doubtless embroidered the facts.

The custom today is to engage callow adjunct instructors to teach beginning studios. Wilson was 50 when I encountered him. He had started teaching when he was 36, and had years of practical experience under his belt. In the 1960s, he designed the interior of the St. Regis Tavern on St. Catherine Street, a cavernous space with an undulating Aaltoesque ceiling and hanging Bauhaus mobiles–he called them Doodle Boxes. It was an unexpected setting for a roomful of blue-collar men (taverns at that time were male preserves), noisily drinking Labatt and eating pig’s knuckles. Wilson also conducted sketching school, a two-week summer camp that was required to be taken–twice–by all students. He was an accomplished watercolorist and had exhibited in galleries, although we didn’t know that at the time.

In 1963, my classmate Ralph Bergman and I started a school magazine. The second issue included articles by Paolo Soleri, Christopher Alexander, and Philip Thiel. I asked Wilson if he would write something on programming. The result was “A Sordid Discussion, or Loose Talk on Programming,” a make-believe bull-session on the subject set, of course, in a tavern. “In a corner, seated beside a few beers and torn crinkly packages of barbecued potato chips, a small tense group of architecture types, boys and men, rocked and rolled in their chairs and poked out arms and chins.” The older man, a gruff professor, challenges the motley group of students–Owl, Mop-head, Cool, Turbulent, Passionate, Prim, and Scornful. Just another typical class. Wilson (1912-91) retired officially in 1981, but taught for another decade, a total of 43 years.

August 2, 2013

THE FINAL CUT

Renzo Piano and model of the Menil Collection. Peter Rice is at left, partner Shunji Ishida on immediate right.

The death of architect Natalie De Blois, who worked on some of SOM’s best projects in the firm’s heyday–Pepsi Cola, Lever House, Union Carbide–has again raised the question of gender and architecture. We are reminded of many unheralded collaborating female architects–Marion Mahoney with Frank Lloyd Wright, Lilly Reich with Mies van der Rohe, Charlotte Perriand with Le Corbusier, Aino with Alvar Aalto–as if there were a plot to suppress giving proper credit to these women. Yet, the architectural profession, while it is a team endeavor, has always asserted the creative role of the individual practitioner. Architects themselves have fostered this useful illusion. Le Corbusier relied heavily on his engineering collaborator, Vladimir Bodiansky, as did Frank Lloyd Wright on Mendel Glickman, another Russian engineer (who worked on both Johnson Wax and Fallingwater). The wonderful light in Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum and Yale Center for British Art owes a mighty debt to lighting consultant Richard Kelly, and it is surely no coincidence that Kahn’s three masterworks, Kimbell, Richards, and Salk, all involved engineer August Kommendant. Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano get the credit for the Pompidou Center, but the structural details that define that building are the work of Arup’s Peter Rice, who also collaborated on the Menil Collection. Junior associates have always contributed to their employers’ fame, and when this contribution feels unrewarded, they often break away to strike out on their own, as Michael Hopkins and Ken Shuttleworth did from Norman Foster, Bing Thom from Arthur Erickson, and Adrian Smith from SOM. This has always been the pattern among architects. Although art historians are mistaken in approaching architecture as if it were a personal, individual endeavor, I don’t think that crediting the individual is altogether wrong. The master architect is somewhat like a film director, who marshals a large team, and relies on many collaborators; the cameraman, the editor, the sound man, who all make crucial contributions. Yet, in the end, someone must make the final cut. That is why it is correct to refer to the oeuvre of a great director, just as it is right to see the hand (and eye) of an individual architect in his creations, no matter how many others are involved.

July 30, 2013

THE AMERICAN SYSTEM

Ward Just

The protagonist of Ward Just’s latest novel, Rodin’s Debutante, makes a pronouncement that drew me up short, it is such a pithy and accurate description of the American polity.

“I think at a very early age I understood the American system, the country so various, so large and unruly, poised to fly apart at any moment. The system was founded on compromise and reconciliation, an infinity of checks and balances but always the willingness to look the other way until the world forced closed focus.”

July 28, 2013

CITIES AND BAD DRIVERS

An interesting recent article in Slate asked the question, “Which U.S. City has the Worst Drivers?” The authors studied the 200 largest cities in the country, and using a complicated matrix of measures (which is explained in a useful spreadsheet) they compiled the list of shame. Miami was the worst by a wide margin, followed by Philadelphia, Hialeah, Tampa, and Baltimore. I see two possible patterns here. Obviously, three of the five cities are in Florida so either: a) the heat makes people drive badly (unlikely); the larger number of elderly drivers makes for a dangerous environment (possible); or Latinos are reckless drivers (Hialeah and Miami are overwhelmingly Latino, but then so are many cities in Texas and California, which were generally rated as much safer). As for Baltimore and Philadelphia, both have high poverty rates (Philadelphia has the highest percentage living in poverty of any major U.S. city). Are poorer people less law-abiding drivers, or is it simply that a poorer city has less ability to enforce traffic laws? My guess is the latter. For example, Philadelphia is a city where cars regularly park on downtown sidewalks. Speed limits are rarely enforced. Laws are flouted as a matter of course, and nobody, but nobody, actually stops at STOP signs. I remember that one year in my district, the police started ticketing cars that were parked “on the wrong side of the street,” i.e. facing traffic. There was an immediate outcry–it was unfair, we’ve always done it this way, it’s our neighborhood we can do what we want, etc. The police stopped issuing tickets.

An interesting recent article in Slate asked the question, “Which U.S. City has the Worst Drivers?” The authors studied the 200 largest cities in the country, and using a complicated matrix of measures (which is explained in a useful spreadsheet) they compiled the list of shame. Miami was the worst by a wide margin, followed by Philadelphia, Hialeah, Tampa, and Baltimore. I see two possible patterns here. Obviously, three of the five cities are in Florida so either: a) the heat makes people drive badly (unlikely); the larger number of elderly drivers makes for a dangerous environment (possible); or Latinos are reckless drivers (Hialeah and Miami are overwhelmingly Latino, but then so are many cities in Texas and California, which were generally rated as much safer). As for Baltimore and Philadelphia, both have high poverty rates (Philadelphia has the highest percentage living in poverty of any major U.S. city). Are poorer people less law-abiding drivers, or is it simply that a poorer city has less ability to enforce traffic laws? My guess is the latter. For example, Philadelphia is a city where cars regularly park on downtown sidewalks. Speed limits are rarely enforced. Laws are flouted as a matter of course, and nobody, but nobody, actually stops at STOP signs. I remember that one year in my district, the police started ticketing cars that were parked “on the wrong side of the street,” i.e. facing traffic. There was an immediate outcry–it was unfair, we’ve always done it this way, it’s our neighborhood we can do what we want, etc. The police stopped issuing tickets.

July 27, 2013

TWINKLE, TWINKLE LITTLE STAR

Guy Horton wrote an article recently in ArchDaily on starchitects. He included a number of comments by various architecture critics and observers (including your truly). I was struck that many of my colleagues called for “retiring” the term–whatever that means–as if it were primarily about semantics. It’s not, it’s primarily about money. Just as certain Hollywood actors can make a film script into a bankable movie, certain architects can add monetary value to a project (with donors, buyers, the general public). That is why the acting star and the designing star get paid more. And that is also why both invest heavily in press agents, publicists, and public relations. What certifies a starchitect is as hard to pin down as what makes an actor a star. Probably a combination of native ability, public acclaim, and desire (one rarely becomes a star by accident). Perhaps key is connecting with the zeitgeist. In a consumer culture that depends so heavily on name recognition and celebrity, it was probably inevitable that the architectural profession would eventually be affected–or is it infected? In any case, the impact has been significant. In The Favored Circle, the Australian architect/sociologist Garry Stevens posits the emergence of two distinct categories of architects. “Those at the summit of the field who design structures of power and taste for people of power and taste,” he writes, “have little in common with those who toil at CAD workstations detailing supermarkets.”

Guy Horton wrote an article recently in ArchDaily on starchitects. He included a number of comments by various architecture critics and observers (including your truly). I was struck that many of my colleagues called for “retiring” the term–whatever that means–as if it were primarily about semantics. It’s not, it’s primarily about money. Just as certain Hollywood actors can make a film script into a bankable movie, certain architects can add monetary value to a project (with donors, buyers, the general public). That is why the acting star and the designing star get paid more. And that is also why both invest heavily in press agents, publicists, and public relations. What certifies a starchitect is as hard to pin down as what makes an actor a star. Probably a combination of native ability, public acclaim, and desire (one rarely becomes a star by accident). Perhaps key is connecting with the zeitgeist. In a consumer culture that depends so heavily on name recognition and celebrity, it was probably inevitable that the architectural profession would eventually be affected–or is it infected? In any case, the impact has been significant. In The Favored Circle, the Australian architect/sociologist Garry Stevens posits the emergence of two distinct categories of architects. “Those at the summit of the field who design structures of power and taste for people of power and taste,” he writes, “have little in common with those who toil at CAD workstations detailing supermarkets.”

July 24, 2013

LACMA FOLLIES

Somebody asked Renzo Piano what is was like to design an addition–the Broad Contemporary Art Museum–to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “As I already told you, it’s very frustrating to play a good piece by a string quartet in the middle of three badly played rock concerts,” he responded. As I wrote in Slate: “Piano was referring to the existing museum buildings, whose architecture is pretty bad, as if a shopping mall had been converted into a cultural facility. But after sitting in the outdoor cafe, watching groups of excited children running across the roofed plaza and teenagers wandering in off the street, it struck me that this vulgar (in the literal sense of the word) Southern Californian solution to an art museum succeeded in one important way. In part because of its lack of pretension, this is an art museum in which people appear decidedly at home.” I wasn’t much impressed by Piano’s string quartet, but the rock concert struck me as a pretty interesting place. Now LACMA has announced a $650 million plan to demolish the three old buildings (a pavilion by Bruce Goff will be preserved) and replace them with a brand new museum designed by Peter Zumthor. Most critics admire Zumthor’s work, and the project has generally been greeted with accolades. I’ve never warmed to his pious brand of minimalism, but this project strikes me as misconceived not because of what will be built, but because of what will be lost. The old LACMA is a refreshingly quirky setting for art; neither palatial, like the nineteenth-century museums, nor primly aesthetic, like most new museums. It would be nice if LA stopped continuously trying to re-invent itself.

Somebody asked Renzo Piano what is was like to design an addition–the Broad Contemporary Art Museum–to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “As I already told you, it’s very frustrating to play a good piece by a string quartet in the middle of three badly played rock concerts,” he responded. As I wrote in Slate: “Piano was referring to the existing museum buildings, whose architecture is pretty bad, as if a shopping mall had been converted into a cultural facility. But after sitting in the outdoor cafe, watching groups of excited children running across the roofed plaza and teenagers wandering in off the street, it struck me that this vulgar (in the literal sense of the word) Southern Californian solution to an art museum succeeded in one important way. In part because of its lack of pretension, this is an art museum in which people appear decidedly at home.” I wasn’t much impressed by Piano’s string quartet, but the rock concert struck me as a pretty interesting place. Now LACMA has announced a $650 million plan to demolish the three old buildings (a pavilion by Bruce Goff will be preserved) and replace them with a brand new museum designed by Peter Zumthor. Most critics admire Zumthor’s work, and the project has generally been greeted with accolades. I’ve never warmed to his pious brand of minimalism, but this project strikes me as misconceived not because of what will be built, but because of what will be lost. The old LACMA is a refreshingly quirky setting for art; neither palatial, like the nineteenth-century museums, nor primly aesthetic, like most new museums. It would be nice if LA stopped continuously trying to re-invent itself.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers