Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 26

October 29, 2015

ENTERTAIN ME

I was complaining to my friend Anthony Alofsin the other day about the current tendency to review buildings as if they were movies, that is, as if they could be digested at one sitting rather than over an extended period of time. “Reviewing the latest as the greatest fits into the mode of consumer entertainment,” he responded in an email. “Like, which Netflix special do I see next? Unfortunately, it is the current moment that sells and is in demand, not the long view.” He is exactly right. The infatuation with the “current moment” explains why as-yet unbuilt projects receive so much attention. The next new thing is the all-consuming topic. Actual construction appears to be almost an extraneous step—an afterthought. My local AIA chapter awards a silver medal to an “unbuilt project of the most exemplary design quality.” Apparently design quality can be recognized absent performance. As long as it looks like fun.

I was complaining to my friend Anthony Alofsin the other day about the current tendency to review buildings as if they were movies, that is, as if they could be digested at one sitting rather than over an extended period of time. “Reviewing the latest as the greatest fits into the mode of consumer entertainment,” he responded in an email. “Like, which Netflix special do I see next? Unfortunately, it is the current moment that sells and is in demand, not the long view.” He is exactly right. The infatuation with the “current moment” explains why as-yet unbuilt projects receive so much attention. The next new thing is the all-consuming topic. Actual construction appears to be almost an extraneous step—an afterthought. My local AIA chapter awards a silver medal to an “unbuilt project of the most exemplary design quality.” Apparently design quality can be recognized absent performance. As long as it looks like fun.

October 26, 2015

CONTEMPORIZE

I heard a word the other day that brought me up short: contemporize. It was uttered by an architect who was describing a university building of the late 1960s that was being renovated. He was not referring to the updating of mechanical and environmental systems—that happens all the time in older buildings—he was describing changes to the architecture itself. The undistinguished Sixties building is mainly brick and concrete. In this case, contemporizing—an ugly invented word—seemed to consist of adding as much glass as possible. Glass is the materiel du jour; it is transparent, open, inviting, progressive, not like fusty old brick or dull grey concrete. Perhaps in fifty years glass, too, will be replaced—by recycled plastic or reconstituted wood, whatever is the fashion of the future. But for the moment glass sends the message “We are up contemporary.” The B-side of the message is “We are just like everybody else.”

I heard a word the other day that brought me up short: contemporize. It was uttered by an architect who was describing a university building of the late 1960s that was being renovated. He was not referring to the updating of mechanical and environmental systems—that happens all the time in older buildings—he was describing changes to the architecture itself. The undistinguished Sixties building is mainly brick and concrete. In this case, contemporizing—an ugly invented word—seemed to consist of adding as much glass as possible. Glass is the materiel du jour; it is transparent, open, inviting, progressive, not like fusty old brick or dull grey concrete. Perhaps in fifty years glass, too, will be replaced—by recycled plastic or reconstituted wood, whatever is the fashion of the future. But for the moment glass sends the message “We are up contemporary.” The B-side of the message is “We are just like everybody else.”

October 24, 2015

NOAH’S ARK

I came across a new term the other day: NOAH. It stands for “naturally occurring affordable housing” and it was coined by Howard Husock and Alex Armlovich of the Manhattan Institute. Their paper is focused on New York City, specifically Mayor Di Blasio’s plan to build 80,000 new “permanently affordable” rental units over ten years. The researchers found that there are almost 50,000 NOAHs already in existence, that is, “apartments that overlap in price with the mayor’s affordability targets but that are currently available and require no additional government investment.” These apartments are in less expensive parts of the city, as one would expect. Husock and Armlovich’s general thesis is interesting. Advocates of affordable housing usually take it for granted that any solution requires building new housing. New publicly-financed housing is more expensive than existing market housing, in part because it involves public agencies, architects, social workers, etc., in part because affordable housing standards usually exceed what the market provides, and in part simply because new housing costs more than existing housing (by the same logic, lower-income people tend to drive used cars not this year’s model). Just how much more expensive was demonstrated by the Sugar Hill Development (illustrated) which was praised by New York magazine as “the kind of high-design, low-cost housing that the city needs.” Built by a non-profit in Harlem, and designed (in hip, forbidding black by David Adjaye), the project reached a cost of $550,000 per unit, well above the city average. High-design, maybe, but definitely not low-cost.

I came across a new term the other day: NOAH. It stands for “naturally occurring affordable housing” and it was coined by Howard Husock and Alex Armlovich of the Manhattan Institute. Their paper is focused on New York City, specifically Mayor Di Blasio’s plan to build 80,000 new “permanently affordable” rental units over ten years. The researchers found that there are almost 50,000 NOAHs already in existence, that is, “apartments that overlap in price with the mayor’s affordability targets but that are currently available and require no additional government investment.” These apartments are in less expensive parts of the city, as one would expect. Husock and Armlovich’s general thesis is interesting. Advocates of affordable housing usually take it for granted that any solution requires building new housing. New publicly-financed housing is more expensive than existing market housing, in part because it involves public agencies, architects, social workers, etc., in part because affordable housing standards usually exceed what the market provides, and in part simply because new housing costs more than existing housing (by the same logic, lower-income people tend to drive used cars not this year’s model). Just how much more expensive was demonstrated by the Sugar Hill Development (illustrated) which was praised by New York magazine as “the kind of high-design, low-cost housing that the city needs.” Built by a non-profit in Harlem, and designed (in hip, forbidding black by David Adjaye), the project reached a cost of $550,000 per unit, well above the city average. High-design, maybe, but definitely not low-cost.

September 15, 2015

WHAT’S TO LOVE?

Like most people I am dismayed at the demolition of Paul Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center. But I am more dismayed by the thought that we have not learned the lesson that this Sixties building has to teach. Rudolph often stepped over the line between expression and functionality, and any designer who does so should not be surprised that his/her artifact does not gain the affection of its users. I still have my old wooden swivel office chair, but my Wassily Chair is long gone. There is another lesson that the Orange County building should teach us. Exposed concrete, in this case mostly patterned concrete blocks, is not a good finish material. It weathers badly on the exterior, and it is unpleasant on the interior. In the 1960s, exposed concrete was all the rage—so was cigarette smoking, gas-guzzling cars, asbestos cement, and lead-based paint. We now see that the last four were mistakes. So was concrete. It is a fine structural material, and OK in parking garages and stadiums (especially in the hands of a master like Nervii), but not a fit replacement for brick, stone, or wood as cladding or interior finish. There are already signs that, in a nostalgic rush to preserve exposed concrete buildings of the Sixties, we are trying to convince ourselves that concrete really is an acceptable finish material. That it’s just a matter of taste. It isn’t—it was a mistake that shouldn’t be repeated. Which raises a perplexing question: How does one preserve a mistake?

Like most people I am dismayed at the demolition of Paul Rudolph’s Orange County Government Center. But I am more dismayed by the thought that we have not learned the lesson that this Sixties building has to teach. Rudolph often stepped over the line between expression and functionality, and any designer who does so should not be surprised that his/her artifact does not gain the affection of its users. I still have my old wooden swivel office chair, but my Wassily Chair is long gone. There is another lesson that the Orange County building should teach us. Exposed concrete, in this case mostly patterned concrete blocks, is not a good finish material. It weathers badly on the exterior, and it is unpleasant on the interior. In the 1960s, exposed concrete was all the rage—so was cigarette smoking, gas-guzzling cars, asbestos cement, and lead-based paint. We now see that the last four were mistakes. So was concrete. It is a fine structural material, and OK in parking garages and stadiums (especially in the hands of a master like Nervii), but not a fit replacement for brick, stone, or wood as cladding or interior finish. There are already signs that, in a nostalgic rush to preserve exposed concrete buildings of the Sixties, we are trying to convince ourselves that concrete really is an acceptable finish material. That it’s just a matter of taste. It isn’t—it was a mistake that shouldn’t be repeated. Which raises a perplexing question: How does one preserve a mistake?

September 2, 2015

VISUAL POLLUTION

Alfi Chair, by Jasper Morrison for Emeco

I came across an online lecture at a design conference by the British product designer Jasper Morrison recently, and I was struck by one of his statements. “As designers, we are responsible for our environment, and filling it with amazing shapes and forms and surprising expressions of our genius, doesn’t make a very good atmosphere. In fact, to me it’s becoming a kind of visual pollution.” Morrison was talking about housewares, appliances and chairs, but he could have been describing buildings. The pressure on architects to produce new and exciting forms that will attract the attention of the media has had a distorting and negative effect on the field—visual pollution, indeed.

August 2, 2015

THE MASTER BUILDER

Watched Jonathan Demme’s film version of Ibsen’s A Master Builder the other evening. What struck me was Wallace Shawn in the title role, a combination of charm and egoism that, in my experience, is typical of most successful architects. Charm is required to convince clients, review panels, and community boards of the merits of one’s case; egoism is required to convince oneself of the merits of an as-yet unbuilt, perhaps untried, idea. I have never been convinced by the cinematic portrayal of architects—Gary Cooper in The Fountainhead, Paul Newman in Towering Inferno, Richard Gere in Intersection. (Gere, at least, did have the Armani suits.) Burly Albert Finney in Two for the Road, was charming and ego-centered by turns, but he was too physical—one could imagine him playing rugby. But architects, at least in my experience of students in college, are rarely athletes and never of team sports. Tennis and squash, maybe, but not baseball or football. Short, self-contained, charismatic, Shawn’s Halvard Solness was perfect.

Watched Jonathan Demme’s film version of Ibsen’s A Master Builder the other evening. What struck me was Wallace Shawn in the title role, a combination of charm and egoism that, in my experience, is typical of most successful architects. Charm is required to convince clients, review panels, and community boards of the merits of one’s case; egoism is required to convince oneself of the merits of an as-yet unbuilt, perhaps untried, idea. I have never been convinced by the cinematic portrayal of architects—Gary Cooper in The Fountainhead, Paul Newman in Towering Inferno, Richard Gere in Intersection. (Gere, at least, did have the Armani suits.) Burly Albert Finney in Two for the Road, was charming and ego-centered by turns, but he was too physical—one could imagine him playing rugby. But architects, at least in my experience of students in college, are rarely athletes and never of team sports. Tennis and squash, maybe, but not baseball or football. Short, self-contained, charismatic, Shawn’s Halvard Solness was perfect.

July 22, 2015

SHORT LIFE

Scarborough College, Toronto. Built 1966.

49 years old

I read an amazing (for me) fact recently. A participant in a Getty Center colloquium on building preservation casually observed that the life cycle of conventionally built (masonry and wood) buildings is about 120 years (before major repairs), whereas for modernist buildings it is only half that time—sixty years. Consider Yale’s masterpieces of the 1960s: Louis Kahn’s art gallery, Paul Rudolph’s A & A, Eero Saarinen’s colleges. They have all recently undergone major renovation, at a cost far exceeding the original construction cost. In the words of Yale dean, Robert A. M. Stern, “They cost pennies to build and millions to renovate.”

Sixty years! You might say that architects today are delivering half the product that they used to. For a long time, a building’s durability was taken for granted. It might be clad in marble, brick, or stucco, but with adequate maintenance (cleaning, re-pointing, painting and plastering), it could be expected to last. This was because construction consisted of heavy masonry walls, whether you were building a villa, a palazzo, or a basilica. This changed when reinforced concrete came into common use. The new material seemed almost magical, allowing dramatic cantilevers, shell-thin vaults, skinny columns. It took several decades to discover that steel and concrete were precarious partners, and that porous, fragile concrete was a poor substitute for stone and brick as external cladding. By then a generation of Brutalist buildings had come into being. Structural steel is durable, but the lightweight glass curtain wall has its own problems: gaskets, sealants, glass coatings. A sixty-year life? probably.

Modern architecture looks so, well modern. Efficient, engineered, precise, machine-made. Who knew? “Oh, by the way. This isn’t your grandfather’s building. Don’t expect it to be around for centuries. In fact, expect to shell out much more in sixty years to keep it going than you paid to build it. Or just knock it down. After all, it wasn’t meant to last.”

July 12, 2015

TOO MANY COOKS

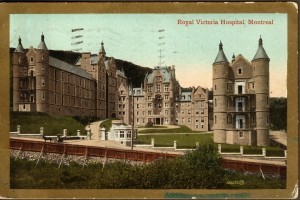

The current copy of my alumni magazine, McGill News, contains an article on the university’s new health center, a 2.5 million square-foot behemoth that consolidates no less than four existing health facilities. It’s hard to characterize this building, other than to say that it is big. The article does not identify the architect. Perhaps because this particular broth had so many cooks. The health center was built by a public-private partnership, that is, the building was designed, built, and financed by a private consortium, a process increasingly popular for public as well as private buildings. Originally, Moshe Safdie was commissioned to prepare the master plan, but he withdrew when it became apparent that the consortium, not the planner, would be calling the shots. In the event, the building appears to have been designed by at least four architectural firms. The predictable result, which a local journalist characterized as “Legoland,” exhibits no discernible architectural conviction. I recently wrote an article about Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium, a building whose design was guided by the patients’ wellbeing. The new Montreal hospital appears to have been the result of a combination of compromise, expediency, and the bottom line. All the sadder since one of the buildings it replaces, the Royal Victoria Hospital, was a building of real architectural merit, designed by Henry Saxon Snell, a Victorian Scot who is said to have modeled his turreted limestone design on the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh. It was built in 1893 and served for 122 years. One cook, one fine broth.

The current copy of my alumni magazine, McGill News, contains an article on the university’s new health center, a 2.5 million square-foot behemoth that consolidates no less than four existing health facilities. It’s hard to characterize this building, other than to say that it is big. The article does not identify the architect. Perhaps because this particular broth had so many cooks. The health center was built by a public-private partnership, that is, the building was designed, built, and financed by a private consortium, a process increasingly popular for public as well as private buildings. Originally, Moshe Safdie was commissioned to prepare the master plan, but he withdrew when it became apparent that the consortium, not the planner, would be calling the shots. In the event, the building appears to have been designed by at least four architectural firms. The predictable result, which a local journalist characterized as “Legoland,” exhibits no discernible architectural conviction. I recently wrote an article about Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium, a building whose design was guided by the patients’ wellbeing. The new Montreal hospital appears to have been the result of a combination of compromise, expediency, and the bottom line. All the sadder since one of the buildings it replaces, the Royal Victoria Hospital, was a building of real architectural merit, designed by Henry Saxon Snell, a Victorian Scot who is said to have modeled his turreted limestone design on the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh. It was built in 1893 and served for 122 years. One cook, one fine broth.

July 9, 2015

FOLLIES

Broadway Tower

Glass House

The architectural folly has a long history. James Wyatt designed Broadway Tower in the Cotswalds in 1794. While it was more or less habitable—William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones rented it as a studio for a time—it was not primarily intended to be a functional shelter. It was an architectural whimsy—and understood as such. It struck me the other day that we take our follies much too seriously. Philip Johnson’s Glass House, for example, is a stereotypical folly: impractical, unusable in extreme weather (it lacks proper ventilation and insect screens), not really a house at all. Yet it is a beautiful pavilion. However, like the Farnsworth House, it is mistakenly taken to be a work of architecture. More than that, it is often represented as exemplary—the expression of the essence of design. That, surely, is a mistake our forebears would never have made. When Wyatt built a country house, like Castle Coole in Ireland, he followed well-established Palladian conventions. There is a time to play and a time to be serious.

July 8, 2015

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers