Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 24

November 27, 2016

ON THE COUCH

Writing a history of seating raises the problem of nomenclature. Take the couch, for example. The Greeks and the Romans dined on couches, which were really more like beds, which may be why the word derives from the French coucher, to lie down, although to complicate matters the French don’t call a couch a couche, but rather a canapé. (You can use that word in English, if you want to be fancy.) Midwesterners used to call couches davenports, after the Massachusetts company that manufactured them. When I was growing up in Canada, we called a couch a chesterfield, a Britishism which has since gone out of fashion. The term is said to have derived from the fourth Earl of Chesterfield, who commissioned a heavily tufted leather couch in the eighteenth century. Couch or sofa? Sofa is a Turkish word, so is ottoman, although the latter is now commonly used to refer to a footstool. Couch seems to have prevailed; we say “casting couch” and “couch potato,” and psychiatrists have couches, not sofas. Sofas seem to be more domestic, which may be why a couch that converts into a bed is called a sleeper sofa or a sofa bed. Go figure.

Writing a history of seating raises the problem of nomenclature. Take the couch, for example. The Greeks and the Romans dined on couches, which were really more like beds, which may be why the word derives from the French coucher, to lie down, although to complicate matters the French don’t call a couch a couche, but rather a canapé. (You can use that word in English, if you want to be fancy.) Midwesterners used to call couches davenports, after the Massachusetts company that manufactured them. When I was growing up in Canada, we called a couch a chesterfield, a Britishism which has since gone out of fashion. The term is said to have derived from the fourth Earl of Chesterfield, who commissioned a heavily tufted leather couch in the eighteenth century. Couch or sofa? Sofa is a Turkish word, so is ottoman, although the latter is now commonly used to refer to a footstool. Couch seems to have prevailed; we say “casting couch” and “couch potato,” and psychiatrists have couches, not sofas. Sofas seem to be more domestic, which may be why a couch that converts into a bed is called a sleeper sofa or a sofa bed. Go figure.

October 16, 2016

SHRINK WRAPPED

These days, urban buildings are playing just one penny-whistle tune: glass, glass, glass. It’s as if there were a material shortage and we had run out of everything else. I don’t miss exposed concrete, but what about limestone and brick, terra cotta and granite? But no, architecture has been reduced to one material—even spandrels and soffits are glass. What explains this phenomenon? Well, of course it’s cheap. The engineer figures out the structure, and the architect wraps it in a glass skin. And the helpful glass manufacturers work out the details for you. It’s also easier to design. No more worrying about junctions between materials, no more textures or finishes, no more colors, no more studying shadowing effects. Just wrap it up and it’s ready to go. Nor do you have to worry about energy—all-glass buildings are as green as you want. Houston, Boston, London, Dubai—it doesn’t matter. It used to be that cities had distinctive architectural characters, derived from different materials, different climates, different tastes. No more. It’s just all glass, all the time.

These days, urban buildings are playing just one penny-whistle tune: glass, glass, glass. It’s as if there were a material shortage and we had run out of everything else. I don’t miss exposed concrete, but what about limestone and brick, terra cotta and granite? But no, architecture has been reduced to one material—even spandrels and soffits are glass. What explains this phenomenon? Well, of course it’s cheap. The engineer figures out the structure, and the architect wraps it in a glass skin. And the helpful glass manufacturers work out the details for you. It’s also easier to design. No more worrying about junctions between materials, no more textures or finishes, no more colors, no more studying shadowing effects. Just wrap it up and it’s ready to go. Nor do you have to worry about energy—all-glass buildings are as green as you want. Houston, Boston, London, Dubai—it doesn’t matter. It used to be that cities had distinctive architectural characters, derived from different materials, different climates, different tastes. No more. It’s just all glass, all the time.

October 8, 2016

MY FAVORITE CHAIR

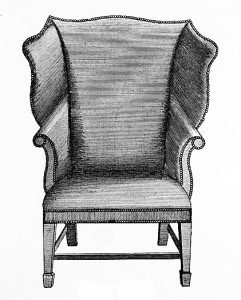

In connection with the publication of Now I Sit Me Down I’ve been touring around giving talks and readings. A common question from the audience is “What is your favorite chair?” I think that the implied question is often “What is your favorite chair design?” but I prefer to answer it literally. I believe that what makes a chair a “favorite” is not the way it looks, or the notoriety of its designer, but rather what it is used for. For me, and I suspect for many people, a favorite chair is the one you sit in to relax at the end of the day. In my case it’s my reading chair. When writing is done, it’s where I read for pleasure, or sometimes re-read what I’ve written that day. Sitting in my chair I gain a different perspective from when I’m working at my desk. What is my reading chair? It’s a wing chair. Not an antique, but manufactured maybe thirty years ago by Hickory Chair, based on an eighteenth-century model from Tidewater Virginia. It’s not much different than the chair that George Hepplewhite included in his Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (above). That was published in 1788. It’s hard to improve on a good thing.

In connection with the publication of Now I Sit Me Down I’ve been touring around giving talks and readings. A common question from the audience is “What is your favorite chair?” I think that the implied question is often “What is your favorite chair design?” but I prefer to answer it literally. I believe that what makes a chair a “favorite” is not the way it looks, or the notoriety of its designer, but rather what it is used for. For me, and I suspect for many people, a favorite chair is the one you sit in to relax at the end of the day. In my case it’s my reading chair. When writing is done, it’s where I read for pleasure, or sometimes re-read what I’ve written that day. Sitting in my chair I gain a different perspective from when I’m working at my desk. What is my reading chair? It’s a wing chair. Not an antique, but manufactured maybe thirty years ago by Hickory Chair, based on an eighteenth-century model from Tidewater Virginia. It’s not much different than the chair that George Hepplewhite included in his Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (above). That was published in 1788. It’s hard to improve on a good thing.

August 31, 2016

ALL THAT GLITTERS ISN’T BRONZE

I went to see the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C. The building isn’t open to the public yet so I could only see the exterior. Yet because of its location on the National Mall this is one building whose exterior appearance is key. It’s the last structure on the north side of the Mall, down the hill from the Washington Monument. From a distance, the museum has a nice scale and an evocative form. The corona shape has always seemed symbolically right to me, recalling both traditional Yoruba tribal art and a Brancusi sculpture. The boxy glass penthouse introduces a mundane element that doesn’t really enhance the corona, but it disappears as you get closer. Close-up, the corona shape turns out to be insubstantial—a metal shroud—which is a bit of a letdown. Moreover, the patterned screen that is meant to recall Charleston and New Orleans ironwork, instead looks like the world’s largest ventilating grille. Its flimsiness is emphasized by the contrast with the handsome stone-clad canopy over the entrance, and the irregular cut-outs that form viewing windows. The skin was originally to be bronze, but when this proved expensive—and extremely heavy—aluminum with a bronze coating was substituted. Unfortunately, it sparkles in the sun, and its brass-like finish lacks the gravitas of dark, moody bronze. Indeed, the effect is cheerfully commercial, not what we expect in a national museum. Does bronze-coated aluminum become dull with time like the real thing? I certainly hope so.

I went to see the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C. The building isn’t open to the public yet so I could only see the exterior. Yet because of its location on the National Mall this is one building whose exterior appearance is key. It’s the last structure on the north side of the Mall, down the hill from the Washington Monument. From a distance, the museum has a nice scale and an evocative form. The corona shape has always seemed symbolically right to me, recalling both traditional Yoruba tribal art and a Brancusi sculpture. The boxy glass penthouse introduces a mundane element that doesn’t really enhance the corona, but it disappears as you get closer. Close-up, the corona shape turns out to be insubstantial—a metal shroud—which is a bit of a letdown. Moreover, the patterned screen that is meant to recall Charleston and New Orleans ironwork, instead looks like the world’s largest ventilating grille. Its flimsiness is emphasized by the contrast with the handsome stone-clad canopy over the entrance, and the irregular cut-outs that form viewing windows. The skin was originally to be bronze, but when this proved expensive—and extremely heavy—aluminum with a bronze coating was substituted. Unfortunately, it sparkles in the sun, and its brass-like finish lacks the gravitas of dark, moody bronze. Indeed, the effect is cheerfully commercial, not what we expect in a national museum. Does bronze-coated aluminum become dull with time like the real thing? I certainly hope so.

August 10, 2016

BOOKIA

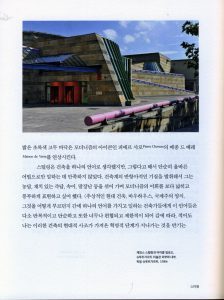

One reviewer of How Architecture Works suggested that readers should have a iPad handy when they read my book so that they could refer to images of the buildings that are mentioned in the text. The book has photos, but they are black and white, and not large, the usual format for a trade book. Now the publisher Mimesis has solved that problem. The Korean edition of the book is illustrated with beautiful color photographs, many taking a full page, and in some cases (Salk Institute, Centre Pompidou, Bilbao Guggenheim) a two-page spread. Mimesis is the art-book arm of Open Books, a leading Seoul publisher. The book is printed in Korea on matte paper and resembles a high-end museum catalog. It sells for ₩28,000, about $25. I want to rush out and buy a Kia Soul.

One reviewer of How Architecture Works suggested that readers should have a iPad handy when they read my book so that they could refer to images of the buildings that are mentioned in the text. The book has photos, but they are black and white, and not large, the usual format for a trade book. Now the publisher Mimesis has solved that problem. The Korean edition of the book is illustrated with beautiful color photographs, many taking a full page, and in some cases (Salk Institute, Centre Pompidou, Bilbao Guggenheim) a two-page spread. Mimesis is the art-book arm of Open Books, a leading Seoul publisher. The book is printed in Korea on matte paper and resembles a high-end museum catalog. It sells for ₩28,000, about $25. I want to rush out and buy a Kia Soul.

July 30, 2016

SUNDAY ARCHITECTURE

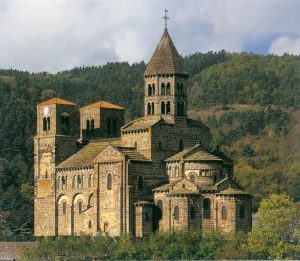

I recently watched an interesting lecture on YouTube delivered by Dietmar Eberle at the 2013 World Architecture Festival in Singapore. Eberle is the principal of the Austrian architectural firm Baumschlager Eberle. During his talk he referred metaphorically to Weekday Architecture and Sunday Architecture. The former are the places where we spend most of our lives, the places where we live, work, and shop. The latter, by contrast, are the special buildings that we use on weekends: museums, concert halls, casinos, and of course places of worship. In the past, “Architecture” was synonymous with Sunday Architecture, churches, civic monuments, royal palaces. Weekday Architecture was left to vernacular builders. By the early twentieth century, architects had made inroads into Weekday Architecture, and they were designing housing, factories, and department stores. The early modernists went so far as to try and abolish Sunday Architecture, with the result that it was often hard to distinguish a city hall from a warehouse. Today, it feels like we have moved in the opposite direction: we have abolished Weekdays—as if every day could be Sunday. Sunday Architecture is what the public expects, what the media covers, and what the schools teach.

I recently watched an interesting lecture on YouTube delivered by Dietmar Eberle at the 2013 World Architecture Festival in Singapore. Eberle is the principal of the Austrian architectural firm Baumschlager Eberle. During his talk he referred metaphorically to Weekday Architecture and Sunday Architecture. The former are the places where we spend most of our lives, the places where we live, work, and shop. The latter, by contrast, are the special buildings that we use on weekends: museums, concert halls, casinos, and of course places of worship. In the past, “Architecture” was synonymous with Sunday Architecture, churches, civic monuments, royal palaces. Weekday Architecture was left to vernacular builders. By the early twentieth century, architects had made inroads into Weekday Architecture, and they were designing housing, factories, and department stores. The early modernists went so far as to try and abolish Sunday Architecture, with the result that it was often hard to distinguish a city hall from a warehouse. Today, it feels like we have moved in the opposite direction: we have abolished Weekdays—as if every day could be Sunday. Sunday Architecture is what the public expects, what the media covers, and what the schools teach.

July 2, 2016

NO-DRAMA OBAMA

Skirkanich Hall

There has been much excitement in the Twittersphere concerning the appointment of Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects to design the Obama presidential library. A no-drama president has picked no-drama architects is the gist of it. No drama? Putting an 8-story blank wall on 53rd Street, as they did in the American Folk Art Museum is nothing if not dramatic. So is designing a skylight in the form of a glass box, then theatrically cantilevering it out at each end, as they did in the new Barnes Foundation. A less well known building, Skirkanich Hall at the University of Pennsylvania presents a half-blank brick wall to the street, and in case you miss it, the shiny glazed brick is green, unlike every other brick building on that campus. Skirkanich stands out in other ways; to further call attention to itself it breaks the building line of the street, like a pushy person in a queue. The neighboring Moore School Building (on the right in the photo), which was altered by Paul Cret in 1926, is much more urbanistically circumspect—and much lower key architecturally, after all, its just a workaday engineering teaching building, not a monument. But TWBTA tends to make a fuss when they build, whether it’s a facade or a simple bench. “Look at me, I’ve been designed” seems to be the message. Implicitly this privileges the person doing the designing. But this is exactly not what a presidential library needs; its subject should take center stage.

June 8, 2016

TRUMPED UP

Campus buildings, if they were Classical in style, used to display their names in Roman lettering incised into the entablature; Collegiate Gothic buildings made do with medieval script. In either case the lettering was discreetly integrated with the architecture. No more. A growing trend in university buildings, especially high-rise buildings, is to display the name at billboard scale (thank you Robert Venturi). This started with medical buildings, but I have noticed other campus buildings sprouting overblown signs (the LeBow College of Business at Drexel is illustrated here). What drives this disturbing practice which gives university buildings the appearance of motels or casinos? In some cases I suspect it is a demand of the donor, in others it is probably an enterprising dean who is to blame. Universities increasingly advertise on the media, so why not tout your name on a building for all the world to see? Why not a flashing neon sign on the ivory tower?

Campus buildings, if they were Classical in style, used to display their names in Roman lettering incised into the entablature; Collegiate Gothic buildings made do with medieval script. In either case the lettering was discreetly integrated with the architecture. No more. A growing trend in university buildings, especially high-rise buildings, is to display the name at billboard scale (thank you Robert Venturi). This started with medical buildings, but I have noticed other campus buildings sprouting overblown signs (the LeBow College of Business at Drexel is illustrated here). What drives this disturbing practice which gives university buildings the appearance of motels or casinos? In some cases I suspect it is a demand of the donor, in others it is probably an enterprising dean who is to blame. Universities increasingly advertise on the media, so why not tout your name on a building for all the world to see? Why not a flashing neon sign on the ivory tower?

May 14, 2016

PACESETTERS

White House (Romaldo Giurgola, arch) 1963

In April 1970 the Historical Society of Chestnut Hill, an old garden suburb of Philadelphia, organized a public panel to discuss the future of their community. The venue had to be changed to accommodate the 800 people who showed up. I suspect that the audience, which included many students, was drawn less by the subject than by the panelists: Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, and Romaldo Giurgola. The local newspaper referred to them as “three of America’s foremost architects” and “today’s pacesetters.” Kahn was already a national figure; Venturi had built little and was probably best known for Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, published in 1966, although the house that he had recently designed for his mother had caused ripples in the architectural world; Giurgola was head of Columbia’s department of architecture and his architectural career was taking off, he had just designed the American embassy in Bogotá. All three had built houses in Chestnut Hill: Kahn the Margaret Esherick house, a little gem; Venturi the Vanna Venturi House, his mother’s house; and Giurgola the Dorothy White House. By curious coincidence all three houses were for single women.

Almost fifty years later the reputations of the “pacesetters” have taken different courses. That of Kahn, who died only four years after the Chestnut Hill panel, has, if anything, grown; his place in history is secure. Venturi’s reputation is harder to assess. Few later projects lived up to the promise of his mother’s house (my favorite is the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in London), and the demise of postmodernism didn’t help, despite the architect’s vain attempt to disassociate himself from that movement. Giurgola received the AIA Gold Medal in 1982, but a well-intentioned effort to expand Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum savaged his reputation and he ended up moving to Australia, where he had won a competition to design the national capital. Like Harry Seidler before him, he seems destined to be remembered—if he is remembered at all—as a purely regional star.

Kahn, Venturi and Giurgola are sometime lumped together as belonging to the “Philadelphia School.” That is hyperbole—they were very different sorts of architects. It is said that at the dinner after the Chestnut Hill panel, they hardly spoke to each other. Still, it would have been interesting to be a fly on the wall.

May 1, 2016

PHENOMENA

Sheraton Huzhou, Jean Nouvel, arch.

I came across the following passage recently.

There have always been dazzling personalities that flashed out of the surrounding gloom like the writing on the wall at the great king’s feast; but they are not manifestations of healthy art. They are phenomena. The sanest, most wholesome art is that which is the heritage of all the people, the natural language through which they express their joy of life, their achievement of just living; and this is civilization,—not commercial enterprises, not industrial activity, not the amassing of fabulous wealth, not increase of population or of empire. These may accompany civilization, but they do not prove it.

This was written by Ralph Adams Cram, the introduction to his Church Building, published in 1899. I read this at the same time as numerous fulsome encomia appeared in the media on the occasion of the death of Zaha Hadid, certainly a “dazzling personality.” She was also, in Cram’s sense, a phenomenon. Like so many leading architects today, her work was personal, eccentric, and idiosyncratic, the very opposite of a natural language, a popular heritage. Not an architecture grounded in a particular place, like Gaudí’s equally eccentric buildings, but global in nature, built in faraway lands for faraway people often of fabulous wealth. Accompanying civilization, but not proving it.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers