Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 21

April 16, 2018

A BRIDGE TOO FAR

Reading about Venice’s new Ponte della Constituzione I was reminded—again—of the dangers of architectural experimentation. The bridge, designed by Santiago Calatrava, is full of novelty: irregular steps, illuminated glass treads, and a beautiful but very flat arch. All these innovations have created problems. The irregularly-dimensioned steps cause people to trip, steps make the bridge inaccessible to wheelchairs (a strange-looking mechanical pod has been added), and the flat arch has created structural stresses on the foundations. As for the glass treads—they become slippery when wet, and the glass gets chipped by tourists wheeling their luggage, requiring expensive replacement. To make matters worse, the bridge cost three or four times more than estimated—a Calatrava trademark. No wonder the city of Venice is suing the architect. But the greater wonder is that clients still commission “ground-breaking” and “unprecedented” designs. Surely they would have learned their lesson by now? Beware of architects bearing shiny new gifts, whether in terms of untested materials, new technologies, or unusual solutions. There is a reason that architecture is—or at least traditionally was—the most conservative of the arts. Buildings last a long time—hundreds of years—and old buildings are the best evidence of what passes the test of time. Palladio was a revolutionary architect in terms of his revival of ancient Roman motifs, but he stuck to tried and true Veneto building solutions: brick construction, timber roof framing, clay-tiled roofs. That’s why his buildings, several of which grace Venice, have lasted so long. Traditional building is not about nostalgia or sentimentality as its critics would have it, but rather about imitating what works.

Reading about Venice’s new Ponte della Constituzione I was reminded—again—of the dangers of architectural experimentation. The bridge, designed by Santiago Calatrava, is full of novelty: irregular steps, illuminated glass treads, and a beautiful but very flat arch. All these innovations have created problems. The irregularly-dimensioned steps cause people to trip, steps make the bridge inaccessible to wheelchairs (a strange-looking mechanical pod has been added), and the flat arch has created structural stresses on the foundations. As for the glass treads—they become slippery when wet, and the glass gets chipped by tourists wheeling their luggage, requiring expensive replacement. To make matters worse, the bridge cost three or four times more than estimated—a Calatrava trademark. No wonder the city of Venice is suing the architect. But the greater wonder is that clients still commission “ground-breaking” and “unprecedented” designs. Surely they would have learned their lesson by now? Beware of architects bearing shiny new gifts, whether in terms of untested materials, new technologies, or unusual solutions. There is a reason that architecture is—or at least traditionally was—the most conservative of the arts. Buildings last a long time—hundreds of years—and old buildings are the best evidence of what passes the test of time. Palladio was a revolutionary architect in terms of his revival of ancient Roman motifs, but he stuck to tried and true Veneto building solutions: brick construction, timber roof framing, clay-tiled roofs. That’s why his buildings, several of which grace Venice, have lasted so long. Traditional building is not about nostalgia or sentimentality as its critics would have it, but rather about imitating what works.

April 6, 2018

STREETSCAPE

Passing the entrance to 10 Rittenhouse Square on 18th Street in Philadelphia today I was caught up short. Robert A. M. Stern Architects, who designed the 33-story apartment tower, have done something cunning. The entrance to the tower is distinctly low key, a simple break in a low stone wall, flanked by two piers topped by stone balls. Beyond the break, a short path leads to a glass marquee over the front door. It was the wall that interested me. 10 Rittenhouse Square’s immediate neighbor is the Fell-Van Rensselaer mansion, designed in 1898 by the great Boston firm, Peabody & Stearns. The Indiana limestone exterior is rather grand. The new limestone wall, which significantly overlaps the two properties, gives the impression that it was originally a part of the mansion. Thus the entrance to number 10 becomes integrated with its older neighbor, despite the fact that the apartment tower itself is brick, not limestone, and does not exhibit similar architectural features. A very nice detail.

Passing the entrance to 10 Rittenhouse Square on 18th Street in Philadelphia today I was caught up short. Robert A. M. Stern Architects, who designed the 33-story apartment tower, have done something cunning. The entrance to the tower is distinctly low key, a simple break in a low stone wall, flanked by two piers topped by stone balls. Beyond the break, a short path leads to a glass marquee over the front door. It was the wall that interested me. 10 Rittenhouse Square’s immediate neighbor is the Fell-Van Rensselaer mansion, designed in 1898 by the great Boston firm, Peabody & Stearns. The Indiana limestone exterior is rather grand. The new limestone wall, which significantly overlaps the two properties, gives the impression that it was originally a part of the mansion. Thus the entrance to number 10 becomes integrated with its older neighbor, despite the fact that the apartment tower itself is brick, not limestone, and does not exhibit similar architectural features. A very nice detail.

April 1, 2018

INTUITION

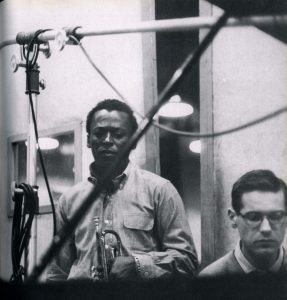

Bill Evans and Miles Davis, late 1950s.

“Intuition has to lead knowledge, but it can’t be out there on its own,” said Bill Evans. “If its on its own, you’re going to flounder sooner or later.” He was speaking to Marian McPartland during a 1979 appearance on her NPR show, Piano Jazz. Evans was talking about the need to respect the basic structures of music, but it struck me that what he said applies equally to architecture. Especially today. Intuition seems to drive design; having set aside knowledge, that is, history, architects are winging it. And, yes, there is much floundering.

February 21, 2018

WE WILL NEVER FORGET

June 5 Memorial, Philadelphia

Petula Dvorzak of the Washington Post called me recently and asked me what I thought of a memorial to the victims of school shootings. I’m not keen on the current fashion for memorializing victims, which has became an almost knee-jerk response to any calamity these days. In my own city, Philadelphia, only a few blocks from where I live, a memorial is under construction. The 125-foot by 25-foot memorial park will commemorate the six people who were killed on June 5, 2013, when a slipshod demolition resulted in a building collapsing on top of a Salvation Army thrift store. A tragedy for those concerned, no doubt, but does it really warrant a memorial? I am sympathetic to the temporary memorials that relatives and friends of victims place after shootings and traffic accidents. These fulfill an important immediate function, especially for those mourning, and their temporariness is part of their character. But formal memorials are forever. We remember soldiers’ sacrifice in war memorials, or those who give their lives in the line of duty. I’m not sure that the innocent victims of muggings—or school shootings—are in the same category. Surely a simple plaque would be more appropriarte?

February 10, 2018

BARBARIANS AT THE GATE

The New Yorker waxes emotional—and rather sappy—about the Philadelphia Eagles parade. The article doesn’t describe the suburban Golden Horde that descended on the center of the city. Hardly two to three million as was cheerfully forecast, but still a very large crowd. Or, rather, a mob. Somehow being part of a large group releases inhibitions. We won, we can do what we like! Throw our bottles and beer cans where we like, dump our used pizza boxes where we like, piss where we like. Late in the afternoon I saw the crowd returning to catch trains at Thirtieth Street Station. Some were carrying street signs and Stop signs, booty to decorate a basement rec room. The next day the city was almost back to normal—the clean-up will take a bit longer.

The New Yorker waxes emotional—and rather sappy—about the Philadelphia Eagles parade. The article doesn’t describe the suburban Golden Horde that descended on the center of the city. Hardly two to three million as was cheerfully forecast, but still a very large crowd. Or, rather, a mob. Somehow being part of a large group releases inhibitions. We won, we can do what we like! Throw our bottles and beer cans where we like, dump our used pizza boxes where we like, piss where we like. Late in the afternoon I saw the crowd returning to catch trains at Thirtieth Street Station. Some were carrying street signs and Stop signs, booty to decorate a basement rec room. The next day the city was almost back to normal—the clean-up will take a bit longer.

January 20, 2018

OFF THE TRACK

“I cannot think of anything more ludicrous than the idea that modernism somehow got off the track and was a monstrous mistake that should simply be canceled out,” wrote Ada Louis Huxtable in The Unreal America. “Revolutions in life and technology can never be reversed.” The last statement is demonstrably untrue—just ask the Russians, the East Europeans, the Cambodians, and the Chinese. Turning back the modernist clock admittedly will be difficult, but the idea that modernism was a monstrous mistake seems to me anything but risible. The suggestion that an industrial age required a different sort of architecture was hardly unreasonable. As Ralph Adams Cram wrote in 1936, it would have been as foolish to look to history for models for new building types such as garages, cinemas, and skyscrapers, as it would be to design “a Greek railroad train, a Byzantine motor car, a Gothic battleship or a Renaissance airplane.” But Cram insisted that it was equally irrational to radically re-imagine buildings such as homes, college dorms, or places of worship, whose function was unaffected by industrialization. His argument fell on deaf ears. Revolutions require simple slogans and wholesale change, and so we got houses that resembled machines, and college quadrangles that resembled factories. The requirement that modern buildings do away with moldings, decoration, and ornament—the whole apparatus of what for centuries had constituted architecture—was most definitely a mistake. And it was monstrous, for it left architecture mute, without a vocabulary. The “language” of modernism resembled Esperanto, and, as Esperanto would have done had it ever been adopted, an invented language cuts its users off from the past. Modern writers in English use the language of Shakespeare, Austen, and Trollope to express their ideas, which inestimably enriches their work. Modern architects make-do with a cobbled-together shorthand that has limited range of expression except, at best, to demonstrate how a thing was made. The saddest aspect of the modernist revolution is that it was unnecessary. As architects such as Raymond Hood, Paul Cret, and Bertram Goodhue showed in the 1920s, it was perfectly possible to design buildings that were modern and “of their time” without throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

“I cannot think of anything more ludicrous than the idea that modernism somehow got off the track and was a monstrous mistake that should simply be canceled out,” wrote Ada Louis Huxtable in The Unreal America. “Revolutions in life and technology can never be reversed.” The last statement is demonstrably untrue—just ask the Russians, the East Europeans, the Cambodians, and the Chinese. Turning back the modernist clock admittedly will be difficult, but the idea that modernism was a monstrous mistake seems to me anything but risible. The suggestion that an industrial age required a different sort of architecture was hardly unreasonable. As Ralph Adams Cram wrote in 1936, it would have been as foolish to look to history for models for new building types such as garages, cinemas, and skyscrapers, as it would be to design “a Greek railroad train, a Byzantine motor car, a Gothic battleship or a Renaissance airplane.” But Cram insisted that it was equally irrational to radically re-imagine buildings such as homes, college dorms, or places of worship, whose function was unaffected by industrialization. His argument fell on deaf ears. Revolutions require simple slogans and wholesale change, and so we got houses that resembled machines, and college quadrangles that resembled factories. The requirement that modern buildings do away with moldings, decoration, and ornament—the whole apparatus of what for centuries had constituted architecture—was most definitely a mistake. And it was monstrous, for it left architecture mute, without a vocabulary. The “language” of modernism resembled Esperanto, and, as Esperanto would have done had it ever been adopted, an invented language cuts its users off from the past. Modern writers in English use the language of Shakespeare, Austen, and Trollope to express their ideas, which inestimably enriches their work. Modern architects make-do with a cobbled-together shorthand that has limited range of expression except, at best, to demonstrate how a thing was made. The saddest aspect of the modernist revolution is that it was unnecessary. As architects such as Raymond Hood, Paul Cret, and Bertram Goodhue showed in the 1920s, it was perfectly possible to design buildings that were modern and “of their time” without throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

January 14, 2018

NOT GOOD ENOUGH

Ever since 1969, the American Institute of architects has bestowed a Twenty-Five Year Award that recognizes a “design of enduring significance.” The only exception was in 1970, when no building was found to merit such recognition. And now in 2018 the same. According to the AIA, “Unfortunately, this year the jury did not find a submission that it felt achieved twenty-five years of exceptional aesthetic and cultural relevance while also representing the timelessness and positive impact the profession aspires to achieve.” Really? No building in the 1983-93 window is good enough? Well, perhaps not Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s AT&T Building (1984), or the Beverly Hills Civic Center (1990) by Charles Moore, but Michael Graves’s Humana Building (1985) in Louisville merits an award, surely more so than Pietro Belluschi’s Equitable Savings & Loan Building in Portland (which won in 1982), or I. M. Pei and Partner’s Hancock Tower in Boston (which won in 2011). And what about Hammond, Beeby & Babka’s Harold Washington Library Center (1991) in Chicago, or Venturi Scott Brown’s Sainsbury Wing (1991) in London, considered by many, including the author, to be that firm’s finest work? In 1971, the award was given to Baldwin Hills Village in LA, a planned community whose design team included Clarence Stein of Radburn fame. In the same vein, surely Seaside, which was realized largely during the 1983-93 time frame and kick-started the New Urbanism movement, deserves recognition? But Seaside’s architecture is traditional in design, so is the Chicago Library, while the Sainsbury Wing is —despite Venturi’s protests—postmodern. Whatever the AIA jury thought of these two approaches to design it was petty and narrow-minded to eliminate them out of hand as seems to have been the case. That’s just not good enough.

Ever since 1969, the American Institute of architects has bestowed a Twenty-Five Year Award that recognizes a “design of enduring significance.” The only exception was in 1970, when no building was found to merit such recognition. And now in 2018 the same. According to the AIA, “Unfortunately, this year the jury did not find a submission that it felt achieved twenty-five years of exceptional aesthetic and cultural relevance while also representing the timelessness and positive impact the profession aspires to achieve.” Really? No building in the 1983-93 window is good enough? Well, perhaps not Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s AT&T Building (1984), or the Beverly Hills Civic Center (1990) by Charles Moore, but Michael Graves’s Humana Building (1985) in Louisville merits an award, surely more so than Pietro Belluschi’s Equitable Savings & Loan Building in Portland (which won in 1982), or I. M. Pei and Partner’s Hancock Tower in Boston (which won in 2011). And what about Hammond, Beeby & Babka’s Harold Washington Library Center (1991) in Chicago, or Venturi Scott Brown’s Sainsbury Wing (1991) in London, considered by many, including the author, to be that firm’s finest work? In 1971, the award was given to Baldwin Hills Village in LA, a planned community whose design team included Clarence Stein of Radburn fame. In the same vein, surely Seaside, which was realized largely during the 1983-93 time frame and kick-started the New Urbanism movement, deserves recognition? But Seaside’s architecture is traditional in design, so is the Chicago Library, while the Sainsbury Wing is —despite Venturi’s protests—postmodern. Whatever the AIA jury thought of these two approaches to design it was petty and narrow-minded to eliminate them out of hand as seems to have been the case. That’s just not good enough.

January 10, 2018

BRITISH CLASSICISM

Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace (John Simson, arch.)

Reading a recent monograph on the work of John Simpson, I am struck again by the difference between British and American classicism. For one thing, the former is rooted in a much shorter tradition. Moreover, it is a tradition that is, in a sense, academic. Or, at least bookish. In the first instance it derived from (British) pattern books, which were the main source of information for the early colonial builders. Nineteenth-century American classicism, on the other hand, was chiefly the product of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where many American architects of that period were trained. Although there were many talented self-taught architects such as Stanford White, Ralph Adams Cram, Bertram Goodhue, and Horace Trumbauer, the leading figures—Richard Morris Hunt, Charles McKim, John Russell Pope, and Thomas Hastings—were EBA alumni, and brought a correct and sometimes rather dry approach to classicism. This is in contrast to nineteenth-century British classicism, which was not based in the academy but in practice. The influence of architects such as John Nash, John Soane, and C. R. Cockerell is evident in Simpson’s designs which are more self-assuredly original than those of many of his American contemporaries which can be often more concerned with correctness than with invention. It is also, interestingly, often more urban, as in this photo (below) of a new residential development along Old Church Street in London’s Chelsea.

January 5, 2018

PARKWAY OR BOULEVARD?

Last year was the centenary of the design of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia. Designed by the Parisian landscape architect, Jacques Gréber in 1917, the avenue slashed diagonally across William Penn’s grid, connecting Logan Circle to Fairmount, a hill which would be the site of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gréber was a notable figure. He worked with Horace Trumbauer (the architect of the future museum) on several mansions, including the Versailles-like Whitemarsh Hall, and collaborated with Paul Cret on the Rodin Museum. (Trumbauer and Cret first proposed the idea of a parkway.) Gréber, who was the chief planner of the 1937 Paris International Exposition, was also responsible for laying out scenic drives in Ottawa.

Last year was the centenary of the design of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia. Designed by the Parisian landscape architect, Jacques Gréber in 1917, the avenue slashed diagonally across William Penn’s grid, connecting Logan Circle to Fairmount, a hill which would be the site of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gréber was a notable figure. He worked with Horace Trumbauer (the architect of the future museum) on several mansions, including the Versailles-like Whitemarsh Hall, and collaborated with Paul Cret on the Rodin Museum. (Trumbauer and Cret first proposed the idea of a parkway.) Gréber, who was the chief planner of the 1937 Paris International Exposition, was also responsible for laying out scenic drives in Ottawa.

The Benjamin Franklin Parkway (originally the Fairmount Parkway) is said to have been based on the Avenue des Champs-Elysées, but that is misleading. This is a parkway on the Olmstedian model. The highlight of Gréber’s Ottawa plan is a drive along the Ottawa River, not so different from Philadelphia’s Kelly Drive (named after Jack Kelly, a gold medal Olympic rower and the brother of the famous actress) that wends its way beside the Schuylkill River through Fairmount Park. That the Parkway is to be read as an introduction to this scenic drive is emphasized by the gatelike Civil War Soldiers’ Monument at its entrance.

The Benjamin Franklin Parkway (originally the Fairmount Parkway) is said to have been based on the Avenue des Champs-Elysées, but that is misleading. This is a parkway on the Olmstedian model. The highlight of Gréber’s Ottawa plan is a drive along the Ottawa River, not so different from Philadelphia’s Kelly Drive (named after Jack Kelly, a gold medal Olympic rower and the brother of the famous actress) that wends its way beside the Schuylkill River through Fairmount Park. That the Parkway is to be read as an introduction to this scenic drive is emphasized by the gatelike Civil War Soldiers’ Monument at its entrance.

Landscaped drives and parkways were a feature of an age when car ownership was on the rise, and people drove for recreation. Little did Gréber imagine that his parkway would become a commuter speedway, however. Another use that Gréber did not intend, but which has become a Philadelphia institution, is the Parkway as the setting for great public events—musical concerts, the beginning and end of the Philadelphia Marathon, a Papal mass, the NFL draft. On such occasions the traffic lanes are closed and the parkway becomes a pedestrian place. There have been recent proposals to permanently “boulevardize” the Parkway, but these plans have inevitably faltered. It would be better to concentrate on reinforcing the adjacent neighborhoods and let the Parkway be what it was intended to be—a place to experience from behind the wheel.

December 1, 2017

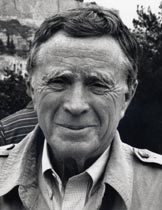

VINCENT SCULLY, 1920-2017

I never attended any of Vincent Scully’s legendary Yale architecture classes but I did hear him speak several times in Montreal, part of the Alcan lecture series that Peter Rose organized in the 1970s. So I could understand when people spoke of his influence. Scully introduced a Celtic passion to the sometimes dry subject of architectural history and his lectures were bravura performances that brought old buildings—and their builders—to life. He was an activist historian in the mold of Siegfried Giedion, and he influenced the contemporary scene, being an early advocate of the work of Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi. I wonder if his obituaries will recall that he made a major volte-face late in life, becoming a critic of mid-century modernism’s negative impact on the city (especially his city, New Haven) and a proponent of New Urbanism. Humanism was at the core of his architectural beliefs.

I never attended any of Vincent Scully’s legendary Yale architecture classes but I did hear him speak several times in Montreal, part of the Alcan lecture series that Peter Rose organized in the 1970s. So I could understand when people spoke of his influence. Scully introduced a Celtic passion to the sometimes dry subject of architectural history and his lectures were bravura performances that brought old buildings—and their builders—to life. He was an activist historian in the mold of Siegfried Giedion, and he influenced the contemporary scene, being an early advocate of the work of Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi. I wonder if his obituaries will recall that he made a major volte-face late in life, becoming a critic of mid-century modernism’s negative impact on the city (especially his city, New Haven) and a proponent of New Urbanism. Humanism was at the core of his architectural beliefs.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers