Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 45

May 18, 2012

Channeling Keisler

My friend Hugh Hartwell sent me a link to a CNN Money story on the late Dick Clark’s house in Malibu. The organic grotto-like home, designed by architect Phillip Jon Brown, is inevitably described by the media as a Fred Flintstone-style house. It really is a version of an idea pioneered by the Austrian architect Frederick Keisler (1890-1965). Keisler was born in what is now Ukraine, studied in Vienna, knew Loos, and was a member of the De Stijl group. In 1926, he moved to New York City, where he lived the rest of his life, working as a window decorator, writing manifestoes, designing visionary projects, teaching at Columbia, and leading the existence of an avant-garde gadfly. His only built work, as far as I know, is the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem, a rather beautiful urn-shaped building housing the Dead Seas Scrolls. What I recall is studying his Endless House, whose maquette was exhibited at MoMA in 1958-59. Blob architecture, before the fact. A couple of years later, I built my own version, out of chicken wire and plaster of Paris, as a student assignment. Keisler never realized the Endless House, except in model form. Maybe he should have moved to Malibu.

May 12, 2012

Our John Soane

Matt McClain for the Washington Post

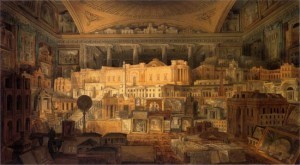

This weekend’s Washington Post magazine has a cover story on Frank Gehry and his design for the Eisenhower memorial. Philip Kennicott has done a fine job explaining the ins and outs on this only-in-Washington teapot tempest, but what struck me was the wonderful photo by Matt McClain of Gehry in a storage room of his LA studio, surrounded by architectural models. It captures not only the architect’s working method, and the intensity of exploration that the scores of models represent, but also the sense of this remarkable artist in his own world. It reminds me of Joseph Michael Gandy’s 1818 painting of a room piled full with models of all the buildings designed by John Soane, a small figure barely visible in the foreground.

May 3, 2012

NAMOC

Olympic Park, Beijing

An architectural competition for the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) is currently underway. The site of the vast (128,000 m2) museum is Beijing, not far from Herzog & de Meuron’s Olympic stadium. This promises to be one of the largest and most ambitious museums since the Getty Center and the Bilbao Guggenheim. Judging from some websites, unsuccessful entrants in the first stage included Koolhaas’s Office for Metropolitan Architecture and Ben van Berkel’s UNStudio. Not clear who else competed, but one supposes the usual suspects. Four firms have reached the final stage: Gehry Partners, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Zaha Hadid Architects, and Safdie Architects. Three Pritzker Prize winners, and an outlier. Although Safdie has had an amazing year with the US Peace Institute, Crystal Bridges in Arkansas, the Sikh Cultural Center in Punjab, and the Marina Bay Sands complex in Singapore. The winner is expected to be announced shortly.

April 27, 2012

WAMO

An international competition for the Washington Monument Grounds has attracted more than 500 participants, and the announcement of the six finalists from as far afield as Korea and the Netherlands has garnered attention in the architectural media. The competition is puzzling, because the sponsor is not the National Park Service, which is responsible for the grounds, but a private group with lead sponsorship from George Washington University, Albert H. Small (a real estate developer), and the Virginia Center for Architecture of the Virginia Society AIA. The competition maintains that the grounds are “unfinished,” despite that the Washington Monument (WAMO) grounds have just been handsomely done over by OLIN, a leading firm of landscape architects. Are we to imagine that all this will be ripped up? Apparently so. There appears not to have been a budget for the competition, which is just as well as it is unclear that there is anyone who would actually be prepared to pay for such unnecessary work. As jury member Benjamin Forgey, the late (and longtime) architecture critic of the Washington Post expressed in a sort of dissenting view, “[The site] does not need vast underground facilities and reshapings of the kind proposed in many of these final schemes, even those that are elegantly designed.” This is billed as an “ideas competition” meant to provoke and stimulate discussion. But discussion about what? And to what end? That is less clear.

April 20, 2012

Catatonic Styles

Ever notice how when people want to be derogatory in referring to a building that uses a traditional style they will use the word “neo,” as in neo-Gothic or neo-Georgian, as if it were not quite the real thing. Instead of simply saying Gothic Revival, or Georgian Revival. For the history of architecture, starting with the Renaissance, is a history of revivals. Gothic, for example, has been revived continuously, starting even during the Renaissance, and has come back to life regularly as clockwork in virtually every period, right up until the present day. When I mentioned this to Edwin Schlossberg, he thought for a second and replied, “What about the catatonic styles?” Of course, he’s right. Some styles seem impervious to revival. Art Nouveau came back in psychedelic posters, but not really in buildings. Modern styles come back, look at Meier and Le Corbusier’s White Period, or the Case Studies houses today. Sam Jacobs is even leading a small Postmodern Revival. But it’s still hard to imagine a Brutalist Revival (sorry Docomomo). It’s a catatonic style.

Federal Office Building, Columbia, SC. 1979, Marcel Breuer, arch.

April 15, 2012

Extreme Makeover

Saint Nicholas Eastern Orthodox Church is located in Springdale, Arkansas. Its architect, Marlon Blackwell, told me the story. The congregation had bought a piece of land for their new church that included a three-truck metal garage. Having a very limited budget, the congregation asked him to convert the garage into a church. The unlikely result is an extremely modest building that successfully confronts a neighboring interstate highway, accommodates the liturgical requirements of the Orthodox rite, and manages to create a strong architectural presence in the process. The exterior has shades of Tadao Ando’s Church of Light and Robert Venturi’s Fire Station Number Four, as well as a vaguely Corbusian canopy. What I liked most was the interior. The bare white walls, bathed by morning light coming through an east-facing transom turn out to be a perfect setting for the richly colored icons and traditional wall paintings of the sanctuary. An Orthodox church needs a dome, and in this one it is made from a recycled satellite dish inserted in the ceiling and adorned with an iconic image. Doing more with less.

April 10, 2012

Rough on Rudolph

Photo: Daniel Case

The New York Times article about the Paul Rudolph county government center in Goshen, N.Y. that is threatened with demolition, has fueled a keen (and since this is 2012, a rather rude) debate. Many conservationists' attitude to old buildings is that they should be treated like art, that is, carefully preserved. The problem is that buildings, unlike paintings, are fixed in place. Art that falls out of favor doesn't have to be destroyed, it can simply be taken out of the front room and put in the back, or in a museum's open storage, or ultimately in a suburban warehouse. It is available to be pulled out, if the need arises, that is if tastes change. One thinks of French pompier art of the late 19th century. It was popular—everything starts by being popular with whoever paid for it—then fell out of favor, then was resurrected (see the Musée d'Orsay). Musical compositions can be played, or not played, or rediscovered and played anew. But a building is a part of one's world, like it or not. It must be lived in and with. One argument is to err on the side of conservation, assuming that at some future time someone will see something that eludes us. Certainly was the case with Frank Furness, and with Rudolph today. But maintenance and change are an essential part of a building's life. A building that is unloved will have a hard time of it; it will not be taken care of, and it will be insensitively altered. Maybe Rudolph's building shouldn't be demolished, but should it be conserved?

April 8, 2012

The Art Police

The controversy over the future Eisenhower Memorial has involved many actors: congressmen and congressional subcommittees, the Eisenhower family, the National Civic Arts Society, the National Capital Planning Commission, and assorted political pundits. A small but influential body central to the process has received less public attention. The U. S. Commission of Fine Arts was the brainchild of Chicago architect Daniel H. Burnham, who with Charles F. McKim, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Frederick Law Olmsted was the author of the so-called McMillan Plan, which redesigned the monumental core of Washington, D.C. Burnham saw the need for an official body to oversee the implementation of the artistic aspects of the plan, and in 1910, Congress created the Commission of Fine Arts, with seven commissioners, chosen from qualified design professionals, to be appointed by the President for a period of four years. Although the Commission reviews the design of all federal buildings in the District, as well as the design of coins and military medals, its chief responsibility is "to advise about the location of statues, fountains, and monuments in the public squares, streets, and parks of the District of Columbia . . . and upon the selection of artists for the execution of the same." In other words, a sort of art police.

[Full disclosure: I am completing my second term as a member of the CFA.]

April 1, 2012

Great Clients

Following a recent lecture at the School of Visual Arts in New York, a D/Crit student asked me an interesting question. I had been speaking about the important role that a client can play in the architectural process, specifically how Robert Sainsbury had influenced a young Norman Foster—not least by commissioning him—in the design of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich. But what about public clients, the student asked, could the public also be a great client? It is a good question. The history of architecture contains many examples of influential individual clients—Fr. Marie-Alain Couturier at both Ronchamp and La Tourette, Phyllis Lambert at the Seagram Building, Esa-Pekka Solonen at Disney Hall. But what about institutions? Can a bureaucratic committee interact creatively with an architect in something as intimate and personal as the design of a building? The answer, I guess is "not easily." The willingness to take a leap of faith, resist compromise, say no at the right time as well as yes, rethink a problem at the eleventh hour, and take a risk, requires an individual will. The case of Louis Kahn is instructive. His Richards Medical Building at the University of Pennsylvania is a needlessly complicated design that is compromised by being a functional failure. Yet only a few years later Kahn designed an outstanding laboratory building that has stood the test of time, both architecturally and functionally. Of course in La Jolla, Kahn worked not with a faceless university committee but with a great client—Jonas Salk.

Louis Kahn and Jonas Salk

March 29, 2012

Real and Unreal

My colleague Enrique Norten sent me a copy of TEN Arquitectos: The Limits of Form, which is hefty catalog of a retrospective exhibition of his firm's work on display (March 3 – June 4) at the Museo Amparo inPuebla, Mexico. Actually, judging from the illustrations in the book, there are no limits to the forms that have been explored by TEN Arquitectos; the catalog is a dizzying array of commercial and institutional projects, rectangular, angled, round, square, torqued, canted, and slightly askew. As architects tend to do, Norten has included unbuilt as well as built work. This follows a well-established tradition, in which unbuilt projects and built work are accorded equal importance. Indeed, the architectural profession regularly awards prizes for buildings before they are actually built (which is sort of like giving an Oscar to a shooting script). Paging through the Norten book can be unnerving, since digital representation has achieved such a high level of refinement that it is often impossible to tell the achieved from the imagined. The Guggenheim Museum in Guadalajara, for example, looks convincingly real, dappled shadows, puffy clouds, reflections on the glass, although the building is unbuilt. Equally convincing is an aerial view of Mercedes House, a condominium complex in New York, until I realize that this is merely a photomontage, a digital model inserted into a real photograph of the Upper West Side. Another victim of the recession I think, but I turn the page . . . and there is a construction photo of the real thing. At least I think it's real. It's hard to tell anymore.

Mercedes House, NYC

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers