Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 46

March 27, 2012

Gimme Shelter

A recent report (read it here) on the shelter situation in Haiti by Ian Davis of Lund University points out a troubling aspect of post-disaster reconstruction. Following the earthquake of 2010, more than 100,000 temporary shelters have been erected. These lightweight timber structures, called T-Shelters, are intended to be a transitional solution between tents, which are the usual emergency post-disaster shelter, and permanent houses. The problem, as Davis points out, is that the average cost of a T-Shelter ($13.80/square foot) is not much less than the average cost of a permanent house ($16.60/square foot). He suggests that the $500 million spent on T-shelters could have been better spent building permanent homes, especially as experience shows that "temporary" shelters tend to last a long time, becoming what he calls a "dismal legacy." This is a problem as T-Shelters often occupy sites that are suited to permanent construction. Since the conventional building technology inHaiti is not timber (there are few trees) but reinforced concrete frames with cement block infill, the materials of the T-shelters are not easily transformed into permanent housing. Moreover, the imported technology is poorly suited to create the sort of skill-training that might generate future employment. Good intentions, not so good results.

Maggie Stephenson/ONU-HABITAT

March 22, 2012

The Death of Criticism

In 1997, my friend Martin Pawley wrote a column for The Architect's Journal titled "The Strange Death of Architectural Criticism." The leading architectural critic of his generation, Martin died in 2008, but I wonder what he would have to say about the latest demise of his craft? The New York Times has a "chief architecture critic" who hardly ever writes about architecture. Paul Goldberger, our leading critic, has not appeared in the New Yorker since May 2011, and that was a piece about New York taxis. I always check to see what Sarah Williams Goldhagen, the interesting critic of The New Republic, has to say, and she hasn't posted anything since November 2011. The Huffington Post has a crowded architecture page, although it is hard to find a clear critical voice among all the snippets of information. Slate decided it could do without an architecture critic—me—last December. I don't know whether it's the recession and dearth of new buildings, or whether after the boom years, when architecture became faddish, the fad has simply faded. Popularity has its costs.

March 19, 2012

Books and Books

When I was at Loyola High School in Montreal, my favorite room was the library. It wasn't just the sight and smell of all those old books, but the opportunity to make discoveries wandering through the stacks. There was a whole shelf of G. A. Henty, and another of Edgar Rice Burroughs, that I worked my way through during an entire semester. This reading was definitely not a class assignment, and I don't think anyone recommended the authors to me. I was probably attracted by the books themselves, solid Edwardian creations with colorfully illustrated cloth covers—no cheap paper jackets in those days. Years later, when I started writing, I reenacted those schoolboy adventures when I prowled university library stacks, researching books on subjects such as leisure, domestic comfort, and small tools. Card catalogues were useful, of course, but a more pleasurable research technique was to find the title I was looking for in the stacks, and then simply browse to the right and left of it, seeing what I could find. This doesn't make much sense in a digital age, and I rarely prowl the stacks anymore. That is a shame, for while the Internet is a very good tool for finding information, it is much less effective at discovering information.

March 17, 2012

Stern 1; Nouvel et al. 0

Great article by Vivian Toy in last week's on the economic value of celebrity architects in New York. It turns out that many of the striking—and strikingly expensive to build—condominiums completed in the last 5 years have failed to deliver on the economic front. Units in buildings such as Jean Nouvel's 100 11th Avenue, Enrique Norten's One York, and Richard Meier's173 Perry Street inBrooklyn, have either been slow to sell, or have sold at greatly discounted prices. During the housing boom, developers convinced themselves that having a name architect attached to their projects was worth the extra cost and added real value. Now, Toy argues, that assumption seems in question. Homes are not like designer jeans. An industry executive is quoted as saying that well-heeled buyers "aren't looking to be sold a lifestyle, they're looking to have their lifestyle understood and respected." Perhaps that is why a notable exception cited in the article is 15 Central Park West, designed by Robert A. M. Stern, which has continued to set sales records. Not so much a question of tradition vs. modernity, but of understanding a market and delivering value. It reminds me of something an old schoolmate told me after he had been in practice some years: "I've learnt that not every building I design has to please me."

100 11th Avenue

March 11, 2012

Tiny Palladian House

Last summer I visited Charleston and saw an interesting house designed by George Holt and Andrew Gould. It's basically a tiny version of Palladio's Villas Saraceno, or at least its central portion, with the characteristic triple arch. No room for a loggia here, just a single room, barely 12 feet deep, but with a wonderfully tall ceiling that maintains the original villa's regal scale. A small house with a big attitude. The ingenious plan has a two bedrooms (each with a bathroom) above, but with two separate staircases, which allows one of the rooms to be rented out. The thick walls look solid because they are solid: load-bearing cement block filled with concrete and reinforced. Nice wood details. The owner, Reid Burgess, has a website with great photos of the construction in progress.

Andrew Gould, Reid Burgess, and WR.

March 10, 2012

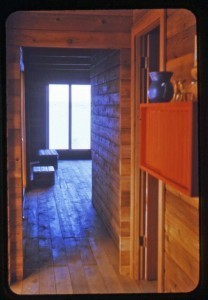

Up at the cottage

Jay Teitel, a writer and editor at Cottage Life magazine in Toronto, recently emailed me a question: he was writing an article titled "The Cottage of the Future," and he wondered if I had any thoughts about what summer cottages would look like in the year 2050. The custom of having a country retreat goes back to at least the ancient Romans—Pliny's villa—but the summer cottage is not simply a house in the country, nor it it a beach house or a ski chalet. The quintessential cottage is a cabin in the forest, perhaps in the mountains, preferably by a lake. A primitive hut. This tradition, which probably dates from the nineteenth century, is most common in Scandinavia, Canada, and parts of the United States, places with wild forest, mountains, and lakes–and cold winters. It is about getting back to nature, canoeing, fishing, chopping wood, cooking outdoors, kerosene lanterns, morning swims. In other words, "roughing it." A summer cottage, at least in my imagination, has no electricity or running water, it smells of wood smoke and cedar planks, it has a porch. What will summer cottages look like in 2050? Forty-four years ago, I built a cottage for my parents inVermont, overlooking Lake Champlain. The current owners have barely moved the furniture, and they still eat at the table and benches I cobbled together out of scrap wood. In another 40 years I expect it all to be still there, pretty much unchanged.

Cottage in Vermont., c.1968

March 7, 2012

The Sixties

My friend Hugh Hartwell, an accomplished pianist, sent me a link recently to a video of Count Basie's big band. The hour-long film of a live concert was shot in 1962 (in Sweden), pretty much the same band I heard in Birdland in 1959 when I was sixteen, although Joe Williams is absent here. What is most striking about the film, apart from the wonderful music, is the serious demeanors of the musicians. Basie clearly ran a tight ship and no one is fooling around—except maybe Sonny Payne, a bit. These are pros doing a job, which just happens to be playing great jazz. The sixties are associated with student unrest, the Vietnam War, and really ugly cars, but it was also a time when a big band like Basie's could make music that, fifty years later, still sounds thrilling.

March 4, 2012

Creative Destruction

Park Circle, a neighborhood in North Charleston, SC, was originally laid out according to British garden city principles in the early 1900s. Since then, the adjacent naval shipyard has closed, and the grand vision has not quite come to fruition. But Park Circle is only ten miles from downtown Charleston, and it caught local developer Vince Graham's eye. He had completed the successful planned community of I'On in nearby Mt.Pleasant, and this seemed like another opportunity to apply the principles of density, walkability and mixed-use. The development, which he called Mixson, after one of the original city's founders, began with a neighborhood of three-story houses tightly grouped around courtyards. The result, conceived by local designers George Holt and Andrew Gould, was like a chunk carved out of the 13th Arondissement and teleported to North Charleston. Real estate is a highly risky business, however—developers are at the mercy of politicians, bankers, and local homeowners. Here, the portents were all favorable, until the national economy intervened, and the housing slump put a stop to Mixson. The little piece of Paris remains unfinished, a cluster of houses surrounded by open space. No doubt, it will one day be complete, but in the meantime, like the original garden city of which it is a part, it remains an old American urban story—the dream that wasn't.

Mixson, SC

February 29, 2012

Housing Redux

Every small rebound in the number of new houses built is followed by a flurry of articles about how the housing industry is poised to make a comeback. But if my developer friend Joe Duckworth is right, the U.S. housing market is not experiencing a correction but a major restructuring. With college graduates heavily in debt—and high school graduates without well-paying jobs—the first-time buyer market is stalled, and existing homeowners, who might have "moved up," are stalled, too. The future, according to Joe, is likely to include many more renters than in the last several decades, and so-called starter homes are likely to become permanent homes, as they were in the 1950s when a Levittown house was likely to last a family's lifetime. Twenty-two years ago, Avi Friedman and I designed the Grow Home, a 14-foot wide row house only 896 square feet in area. Over the next decade they were built in large numbers in the Montreal suburbs with a price tag of around C$60,000 ($95,000 in present day U.S. dollars). We intended the Grow Home as a lower rung for young families beginning their climb up the housing ladder. Today, that ladder appears considerably less tall, and what was designed as an "affordable home" looks like it may be the new normal.

Grow Homes, Montreal, 1992.

February 27, 2012

Corridors

Jon Gertner writes an interesting article in the February 25 New York Times on the history of Bell Labs. It is illustrated by a 1966 photograph of researchers standing outside their offices in a lab building in Murray Hill, N.J. An endless, featureless, rather wide corridor with a strip of fluorescent lighting straight down the center of an acoustic tile ceiling. A model of dreary, unimaginative, bureaucratic design, right? Wrong. As Gertner writes, the building was specially designed by Mervin Kelly (who later became Bell Labs' chairman of the board) in 1941, the long corridor, which everyone in the organization had to walk along, was intended to create chance encounters. These were apparently effective in fostering creativity, as Kelly intended, and in those early years Bell Labs scientists were responsible for seminal inventions such as the transistor, the silicon solar cell, and the laser. There is an important lesson here for architects, who have often sought to find elaborate formal expression in the design of scientific work-place–one thinks of Kahn's Richards Medical Building at Penn, and Gehry's Stata Center at MIT–not always to great effect. Yet sometimes the most effective solution is the simplest. One of the best accounts of how architecture fails–and succeeds—remains Stewart Brand's How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built (1995).

Eliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers