Daniel Orr's Blog, page 100

April 22, 2020

April 22, 1951 – Korean War: Chinese and North Korean forces launch their biggest campaign of the war

On April 22, 1951, Chinese and North Korean forces launched the “Spring Offensive”, their biggest campaign of the Korean War. Thrown into combat were some 700,000 troops comprising three Chinese field armies and two North Korean corps, which attacked first along the western sector of the 38th parallel aimed at recapturing Seoul. Aside from sending two new field armies, the Chinese also brought in six artillery divisions, four anti-aircraft divisions, one multiple-rocket launcher division, and four tank regiments, marking the first time in the war that they deployed such units. At this time, UN forces totaled some 400,000 troops. Two major clashes took place at the UN’s outer lines, at the Imjin River and at Kapyong. There, UN forces, spread thinly and lacking strong defenses, were forced to retreat to prepared lines, but not before fighting delaying tactics which held back the attackers for three days. By April 25, the Chinese/North Korean offensive had ground to halt at the “No-Name Line” north of Seoul.

North Korea and South Korea in East Asia.

North Korea and South Korea in East Asia.(Excerpts taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background During

World War II, the Allied Powers met many times to decide the disposition of

Japanese territorial holdings after the Allies had achieved victory. With regards to Korea,

at the Cairo Conference held in November 1943, the United

States, Britain,

and Nationalist China agreed that “in due course, Korea shall become free and

independent”. Then at the Yalta

Conference of February 1945, the Soviet Union

promised to enter the war in the Asia-Pacific in two or three months after the

European theater of World War II ended.

Then with the Soviet Army invading northern Korea on August 9, 1945, the United States became concerned that the Soviet

Union might well occupy the whole Korean

Peninsula. The U.S.

government, acting on a hastily prepared U.S.

military plan to divide Korea

at the 38th parallel, presented the proposal to the Soviet government, which

the latter accepted.

The Soviet Army continued moving south and stopped at the

38th parallel on August 16, 1945. U.S. forces soon arrived in southern Korea

and advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8, 1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S.

and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in their

respective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commands

established military rule in their occupation zones.

As both the U.S. and Soviet governments wanted to reunify

Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December 1945, the Allied Powers agreed to

form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China)

five-year trusteeship over Korea. During

the five-year period, a U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission would work out the process

of forming a Korean government. But

after a series of meetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve

anything. In September 1947, the U.S.

government referred the Korean question to the United Nations (UN). The reasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission’s

failure to agree to a mutually acceptable Korean government are three-fold and

to some extent all interrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed

U.S.-Soviet trusteeship; the struggle for power among the various

ideology-based political factions; and most important, the emerging Cold War

confrontation between the United States

and the Soviet Union.

Historically, Korea

for many centuries had been a politically and ethnically integrated state,

although its independence often was interrupted by the invasions by its

powerful neighbors, China

and Japan. Because of this protracted independence, in

the immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, and

viewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run their

own affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’s

political climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, from

right-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashed

with each other for political power. As

a result of Japan’s

annexation of Korea

in 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were the

unrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea”

led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and a communist-allied anti-Japanese

partisan militia led by Kim Il-sung.

Both men would play major roles in the Korean War. At the same time, tens of thousands of

Koreans took part in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese

Civil War, joining and fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist

forces, or for Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japanese resistance movement, which operated

mainly out of Manchuria, was divided along

ideological lines. Some groups advocated

Western-style capitalist democracy, while others espoused Soviet

communism. However, all were strongly

anti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria,

China, and Korea.

On their arrival in the southern Korean zone in September

1948, U.S.

forces imposed direct rule through the United States Army Military Government

In Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members of

the Korean Communist Party in Seoul

(the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeated

Japanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Korean

peninsula. Then two days before U.S.

forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee”

proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under the auspices of a U.S. military agent, Syngman Rhee, the former

president of the “Provisional Government of the Republic

of Korea” arrived in Seoul.

The USAMGIK refused to recognize the communist Korean People’s Republic,

as well as the pro-West “Provisional Government”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form a

political coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S.

sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South Korean

Interim Legislative Assembly. However,

this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wing

and right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S. authorities’ breaking up the

communists’ “people’s committees” violence broke out in the southern zone

during the last months of 1946. Called

the Autumn Uprising, the unrest was carried out by left-aligned workers,

farmers, and students, leading to many deaths through killings, violent

confrontations, strikes, etc. Although

in many cases, the violence resulted from non-political motives (such as

targeting Japanese collaborators or settling old scores), American authorities

believed that the unrest was part of a communist plot. They therefore declared martial law in the

southern zone. Following the U.S.

military’s crackdown on leftist activities, the communist militants went into

hiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would play

a role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, Soviet commanders initially

worked to form a local administration under a coalition of nationalists,

Marxists, and even Christian politicians.

But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who also

was a Soviet Red Army officer, quickly became favored by Soviet authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’s

Committee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by Kim

Il-sung who soon consolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christian

leaders), and nationalized industries, and launched centrally planned economic

and reconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model emphasizing heavy

industry.

By 1947, the Cold War had begun: the Soviet Union tightened

its hold on the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United States

announced a new foreign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed at stopping the

spread of communism. The United States also implemented the Marshall

Plan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which was

condemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed at

dividing Europe. As a result, Europe

became divided into the capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting these developments, in Korea

by mid-1945, the United

States became resigned to the likelihood

that the temporary military partition of the Korean peninsula at the 38th

parallel would become a permanent division along ideological grounds. In September 1947, with U.S. Congress

rejecting a proposed aid package to Korea,

the U.S.

government turned over the Korean issue to the UN. In November 1947, the United Nations General

Assembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’s

sovereignty and called for elections throughout the Korean peninsula, which was

to be overseen by a newly formed body, the United Nations Temporary Commission

on Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Soviet government rejected the UNGA resolution,

stating that the UN had no jurisdiction over the Korean issue, and prevented

UNTCOK representatives from entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were held

only in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experienced

widespread violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, a

legislative body. Two months later (in

July 1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitution

which established a presidential form of government. Syngman Rhee, whose party won the most number

of legislative seats, was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southerners

proclaimed the birth of the Republic

of Korea (soon more commonly known as South Korea), ostensibly with the state’s

sovereignty covering the whole Korean

Peninsula.

A consequence of the South Korean elections was the

displacement of the political moderates, because of their opposition to both

the elections and the division of Korea. By contrast, the hard-line anti-communist

Syngman Rhee was willing to allow the (temporary) partition of the

peninsula. Subsequently, the United States

moved to support the Rhee regime, turning its back on the political moderates

whom USAMGIK had backed initially.

Meanwhile in the Soviet-controlled northern zone, on August

25, 1948, parliamentary elections were held to the Supreme National

Assembly. Two weeks later (on September

9, 1948), the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known

as North Korea) was proclaimed, with Kim Il-Sung as (its first) Prime

Minister. As with South Korea, North Korea declared its

sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula

The formation of two opposing rival states in Korea,

each determined to be the sole authority, now set the stage for the coming

war. In December 1948, acting on a

report by UNTCOK, the UN declared that the Republic

of Korea (South

Korea) was the legitimate Korean polity, a decision that

was rejected by both the Soviet Union and North Korea. Also in December 1948, the Soviet Union

withdrew its forces from North

Korea.

In June 1949, the United States

withdrew its forces from South

Korea.

However, Soviet and American military advisors remained, in the North

and South, respectively.

In March 1949, on a visit to Moscow,

Kim Il-sung asked Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, for military assistance for

a North Korean planned invasion of South Korea. Kim Il-sung explained that an invasion would

be successful, since most South Koreans opposed the Rhee regime, and that the

communist insurgency in the south had sufficiently weakened the South Korean

military. Stalin did not give his

consent, as the Soviet government currently was pressed by other Cold War

events in Europe.

However, by early 1950, the Cold War situation had been

altered dramatically. In September 1949,

the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, ending the United States’ monopoly on nuclear

weapons. In October 1949, Chinese

communists, led by Mao Zedong, defeated the West-aligned Nationalist government

of Chiang Kai-shek in the Chinese Civil War, and proclaimed the People’s

Republic of China, a socialist state.

Then in 1950, Vietnamese communists (called Viet Minh) turned the First Indochina

War from an anti-colonial war against France

into a Cold War conflict involving the Soviet Union, China,

and the United States. In February 1950, the Soviet Union and China signed the Sino-Soviet Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance Treaty, where the Soviet

government would provide military and financial aid to China.

Furthermore, the Soviet government, long wanting to gauge

American strategic designs in Asia, was encouraged by two recent developments:

First, the U.S. government did not intervene in the Chinese Civil War; and second,

in January 1949, the United States announced that South Korea was not part of

the U.S. “defensive perimeter” in Asia, and U.S. Congress rejected an aid

package to South Korea. To Stalin, the United States

was resigned to the whole northeast Asian mainland falling to communism.

In April 1950, the Soviet Union approved North Korea’s plan

to invade South Korea, but subject to two crucial conditions: Soviet forces

would not be involved in the fighting, and China’s People’s Liberation Army

(PLA, i.e. the Chinese armed forces) must agree to intervene in the war if

necessary. In May 1950, in a meeting

between Kim Il-sung and Mao Zedong, the Chinese leader expressed concern that

the United States might

intervene if the North Koreans attacked South Korea. In the end, Mao agreed to send Chinese forces

if North Korea

was invaded. North Korea then hastened its

invasion plan.

The North Korean armed forces (officially: the Korean

People’s Army), having been organized into its present form concurrent with the

rise of Kim Il-sung, had grown in strength with large Soviet support. And in 1949-1950, with Kim Il-sung

emphasizing a massive military buildup, by the eve of the invasion, North

Korean forces boasted some 150,000–200,000 soldiers, 280 tanks, 200 artillery

pieces, and 200 planes.

By contrast, the South Korean military (officially: Republic of Korea Armed Forces), which consisted

largely of police units, was unprepared for war. The United

States, not wanting a Korean war, held back from

delivering weapons to South Korea,

particularly since President Rhee had declared his intention to invade North Korea

in order to reunify the peninsula. By

the time of the North Korean invasion, South Korean weapons, which the United States

had limited to defensive strength, proved grossly inadequate. South Korea had 100,000 soldiers

(of whom only 65,000 were combat troops); it also had no tanks and possessed

only small-caliber artillery pieces and an assortment of liaison and trainer

aircraft.

North Korea

had envisioned its invasion as a concentration of forces along the Ongjin Peninsula. North Korean forces would make a swift

assault on Seoul

to surround and destroy the South Korean forces there. Rhee’s government then would collapse,

leading to the fall of South

Korea.

Then on June 21, 1950, four days before the scheduled invasion, Kim

Il-sung believed that South

Korea had become aware of the invasion plan

and had fortified its defenses. He

revised his plan for an offensive all across the 38th parallel. In the months preceding the war, numerous

border skirmishes had begun breaking out between the two sides.

April 21, 2020

April 21, 1975 – Vietnam War: South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu flees into exile abroad as North Vietnamese forces approach Saigon

North Vietnamese leaders, who also were surprised by their quick successes, now decided to advance their timeline for conquering South Vietnam by 1976 to capturing Saigon by May 1, 1975. The offensive on Saigon, called the Ho Chi Minh Campaign and involving some 150,000 troops and supplied with armored and artillery units, began on

April 9, 1975 with a three-pronged attack on Xuan Loc, a city located 40 miles northeast of the national capital and called the “gateway to Saigon”. Resistance by the 18,000-man South Vietnamese garrison (which was outnumbered 6:1) was fierce, but after two weeks of desperate fighting by the defenders, North Vietnamese forces broke through, leaving the road to Saigon open.

In the midst of the battle for Xuan Loc, on April 10, 1975, President Ford again appealed to U.S. Congress for emergency assistance to South Vietnam,

which was denied. South Vietnamese morale plunged even further when on April 17, 1975 neighboring Cambodia fell to the communist Khmer Rouge forces. On April 21, 1975, President Nguyen Van Thieu resigned (and went into exile abroad) and was replaced by a government to try and negotiate a settlement with North Vietnam. But the latter, by now in an overwhelmingly superior position, rejected the offer.

Vietnam War: North Vietnam and South Vietnam in Southeast Asia.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

By April 27, 1975, some 130,000 North Vietnamese troops had encircled Saigon, with some intense fighting breaking out at the outskirts and bridges at the city’s approaches. The South Vietnamese military set up five defensive lines north, west, and east of Saigon, manned by 60,000 troops and augmented by other units that had retreated from the north. However, by this time, the

South Vietnamese forces were verging on collapse, with morale and discipline breaking down, desertions widespread, and ammunition and supplies running

low. In Saigon, desperation and anarchy reigned, with the government’s imposition of martial law failing to quell the panic-stricken population.

The end came on April 30, 1975 when North Vietnamese forces, after launching an artillery barrage on the city one day earlier, attacked Saigon and entered the city with virtually no opposition,

as the South Vietnamese military high command had ordered its troops to lay down their weapons. The Mekong Delta south of Saigon soon also fell. By early May 1975, the war was over.

In the lead-up to Saigon’s fall, thousands of South Vietnamese made a desperate attempt to leave the

country. As early as March 1975, the U.S. government had begun to evacuate its citizens and other foreign nationals, as well as some South Vietnamese civilians. In April 1975, the U.S. launched Operation New Life, where some 110,000 South Vietnamese were evacuated, the great majority consisting of South Vietnamese military officers, Catholics, bureaucrats, businessmen, locals employed in U.S. military and civilian facilities, and other Vietnamese who had cooperated or associated

with the United States and thus were considered to be potential targets for North Vietnamese reprisals. Also in the final days of the war, the U.S. military conducted Operation Frequent Wind, where the remaining U.S. nationals and American troops (U.S.

Marines) were evacuated by helicopters from the Defense Attaché Compound and U.S. Embassy in Saigon onto U.S. ships waiting offshore. The chaotic evacuation, which succeeded in moving over 7,000 Americans and South Vietnamese, was captured in film, with dramatic camera footage showing thousands of frantic South Vietnamese civilians crowding the gates of the U.S. Embassy, and

helicopters being thrown overboard the packed decks of U.S. carriers to make room for more evacuees to arrive.

Some 58,000 U.S. soldiers died in the Vietnam War, with 300,000 others wounded. South Vietnamese casualties include: 300,000 soldiers and 400,000 civilians killed, with over 1 million wounded. North Vietnamese and Viet Cong human losses are variously estimated at between 450,000 and over 1 million soldiers killed and 600,000 wounded; 65,000 North Vietnamese civilians also lost their lives.

Aftermath of the Vietnam War

The war had a profound, long-lasting effect on the United States. Americans were bitterly divided by it, and others became disillusioned with the government. War cost, which totaled some $150 billion ($1 trillion in 2015 value), placed a severe strain on the U.S. economy, leading to budget deficits, a weak dollar, higher inflation, and by the 1970s,

an economic recession. Also toward the end of the war, American soldiers in Vietnam suffered from low morale and discipline, compounded by racial and social tensions resulting from the civil rights movement in the United States during the late 1960s and also because of widespread recreational drug use

among the troops. During 1969-1972 particularly and during the period of American de-escalation and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, U.S. soldiers became increasingly unwilling to go to battle, which resulted in the phenomenon known as “fragging”, where soldiers, often using a fragmentation grenade, killed their officers whom they thought were overly zealous and eager for combat action.

Furthermore, some U.S. soldiers returning from Vietnam were met with hostility, mainly because the war had become extremely unpopular in the United States, and as a result of news coverage of massacres and atrocities committed by American units on Vietnamese civilians. A period of healing and reconciliation eventually occurred, and in 1982,

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was built, a national monument in Washington, D.C. that lists the names of servicemen who were killed or missing in the war.

Following the war, in Vietnam and Indochina, turmoil and conflict continued to be widespread. After South Vietnam’s collapse, the Viet Cong/NLF’s PRG was installed as the caretaker government. But as Hanoi de facto held full political and military control, on July 2, 1976, North Vietnam annexed South Vietnam, and the unified state was called the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Some 1-2 million South Vietnamese, largely consisting of former government officials, military officers, businessmen, religious leaders, and other “counter-revolutionaries”, were sent to re-education camps, which were labor camps, where inmates did various kinds of work ranging from dangerous land mine field clearing, to less perilous construction and

agricultural labor, and lived under dire conditions of starvation diets and a high incidence of deaths and diseases.

In the years after the war, the Indochina refugee crisis developed, where some three million people, consisting mostly of those targeted by government repression, left their homelands in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, for permanent settlement in other countries. In Vietnam, some 1-2 million departing refugees used small, decrepit boats to embark on perilous journeys to other Southeast Asian nations. Some 200,000-400,000 of these “boat people” perished at sea, while survivors who eventually reached Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and other destinations were sometimes met there with hostility. But with United Nations support, refugee camps were established in these Southeast Asian countries to house and process the refugees. Ultimately, some 2,500,000 refugees were resettled, mostly in North America and Europe.

The communist revolutions triumphed in Indochina: in April 1975 in Vietnam and Cambodia, and in December 1975 in Laos. Because the United

States used massive air firepower in the conflicts, North Vietnam, eastern Laos, and eastern Cambodia were heavily bombed. U.S. planes dropped nearly 8 million tons of bombs (twice the amount the United States dropped in World War II), and Indochina became the most heavily bombed area in history. Some 30% of the 270 million so-called cluster bombs dropped did not explode, and since the end of the war, they continue to pose a grave danger to the local population, particularly in the countryside. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) has killed some 50,000 people in Laos alone, and hundreds more in Indochina are killed or maimed each year.

The aerial spraying operations of the U.S. military, carried out using several types of herbicides but most commonly with Agent Orange (which contained the highly toxic chemical, dioxin), have had a direct impact on Vietnam. Some 400,000 were directly

killed or maimed, and in the following years, a segment of the population that were exposed to the chemicals suffer from a variety of health problems, including cancers, birth defects, genetic and mental diseases, etc.

Some 20 million gallons of herbicides were sprayed on 20,000 km2 of forests, or 20% of Vietnam’s total forested area, which destroyed trees, hastened erosion, and upset the ecological balance, food chain, and other environmental parameters.

Following the Vietnam War, Indochina continued to experience severe turmoil. In December 1978, after a period of border battles and cross-border

raids, Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia (then known as Kampuchea) and within two weeks, overwhelmed the country and overthrew the communist Pol Pot regime. Then in February 1979, in reprisal for Vietnam’s invasion of its Kampuchean ally, China launched a large-scale offensive into the northern regions of Vietnam, but

after one month of bitter fighting, the Chinese forces withdrew. Regional instability would persist into the

1990s.

April 20, 2020

April 20, 1961 – Bay of Pigs Invasion: Cuban forces repel Brigade 2506 at the beaches

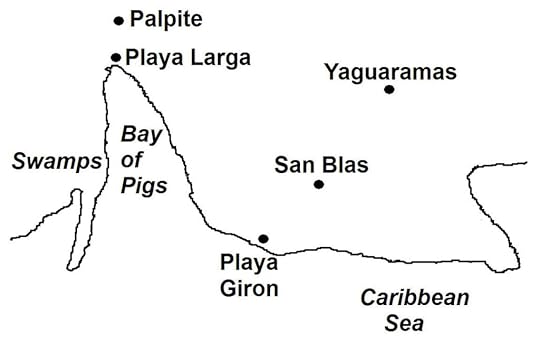

By mid-morning on April 17, 1961, Cuban leader Fidel Castro had mobilized his armed forces and regional militias, sending advance units comprising 20,000 soldiers and auxiliary fighters from the north and east toward the Bay of Pigs. In total, some 50,000 Cuban soldiers and militia fighters took part in the war. The sheer weight of the Cuban Army advance forced Brigade 2506 paratroopers to withdraw from Palpite, which then was recaptured by government forces. Other Castro units sealed off

the roads leading to Covadonga and Yaguaramas. By the end of the first day, Castro’s forces had contained the landings to the Bay of Pigs and nearby areas, with

little chance of a break out; Brigade 2506 was practically trapped on all sides, except from the sea.

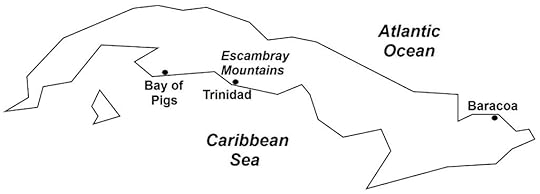

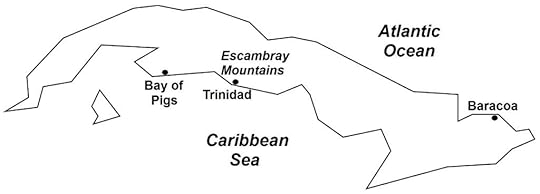

Key sites during the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

(Taken from Bay of Pigs Invasion – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Early on April 18, the invasion force at Playa Larga abandoned the beachhead and withdrew to Playa Giron where, together with other Brigade 2506 units, prepared a better defensive position. Playa Larga soon was retaken by Cuban government forces. From the northeast, Cuban Army infantry, supported by tanks, artillery, and air power, also began advancing in the direction of Playa Giron, forcing the Brigade 2506 paratroopers at San Blas to withdraw to the main landing zones at the beaches.

In Washington, D.C., the CIA, meeting with President Kennedy and top government and military officials, appealed for direct U.S. military intervention. President Kennedy rejected the request but offered a compromise: air cover for Brigade 2506. On the

morning of April 19, a small squadron of U.S. light bombers took off from Nicaragua for Cuba. However, a communications error relating to the time zone differences between Cuba and Nicaragua prevented American fighter escorts from meeting and protecting the bombers before entering Cuban air space. Proceeding anyway, two of the American bombers were shot down by Cuban planes; ultimately, the air mission failed to relieve the beleaguered invasion

forces on the Cuban beaches.

In the afternoon of April 19, the Brigade 2506 force in Playa Giron surrendered in the face of overwhelming ground and air attacks from the Cuban Armed Forces. Small bands of stragglers held off capture by hiding in the swamps, but finally gave up from hunger and exhaustion. Some 1,200 Brigade 2506 soldiers were taken prisoner and 118 were killed in the fighting; a few dozens managed to escape out to sea, and eventually were rescued by U.S. Navy ships.

Aftermath

In December 1962, or twenty months after the failed invasion, in an agreement between Cuba and the United States, Castro freed the Brigade 2506

prisoners and allowed them to return to the United

States in exchange for the United States delivering $53 million worth of food and medicines to Cuba. Some 60 wounded and ill prisoners had been

returned to the United States a few months earlier, while five were executed in Cuba for past crimes. By December 29, 1962, all surviving prisoners had returned to the United States.

The CIA’s underlying premises for the success of the operation were later revealed to be fraught with errors. American and British intelligence information

in Cuba showed that Castro enjoyed wide popularity and that no civilian uprising was likely to occur. The CIA was unsure about the invasion’s success, but believed that once the operation appeared headed for failure, President Kennedy would intervene militarily. Before the invasion, however, President

Kennedy had said many times that he would not send American forces, which was what happened. Even Trinidad, the CIA’s original invasion site which had been planned for many months, when presented to the U.S. Armed Forces Joint Chiefs of Staff, gave the amphibious landing only a limited chance of success.

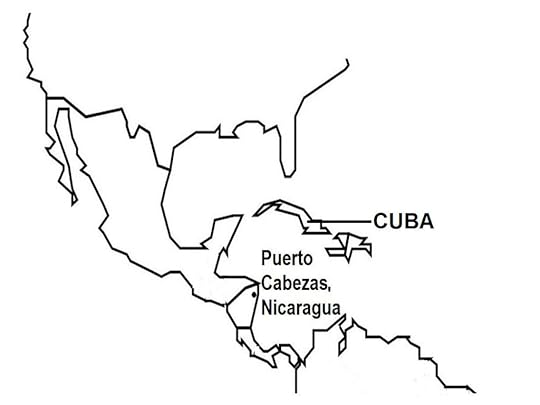

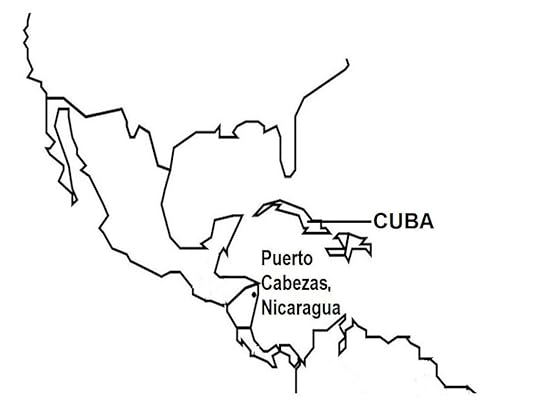

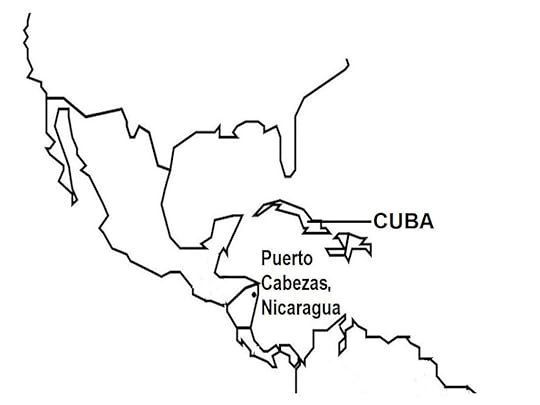

Cuban exiles who formed the invasion force called “Brigade 2506” set off from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, for the invasion of Cuba.

Background of the Bay of Pigs Invasion

The rise to power of Fidel Castro after his victory in ethe Cuban Revolution (previous article) caused great concern for the United States. Castro formed a government that adopted a socialist state policy and opened diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and other European communist countries. After the Cuban government seized and nationalized American companies in Cuba, the United States imposed a trade embargo on the Castro regime and subsequently ended all economic and diplomatic relations with the island country.

Then in July 1959, just seven months after the Cuban Revolution, U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower delegated the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with the task of overthrowing Castro, who had by then gained absolute power as dictator. The CIA devised a number of methods to try and kill the Cuban leader, including the use of guns-for-hire and assassins carrying poison-laced devices. Other schemes to destabilize Cuba also were carried out, including

sending infiltrators to conduct terror and sabotage operations in the island, arming and funding anti-Castro insurgent groups that operated especially in the Escambray Mountains, and by being directly involved in attacking and sinking Cuban and foreign merchant vessels in Cuban waters and by launching air attacks in Cuba. These CIA operations ultimately

failed to eliminate Castro or permanently destabilize his regime.

In March 1960, the CIA began to plan secretly for the invasion of Cuba, with the full support of the Eisenhower administration and the U.S. Armed Forces. About 1,400 anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Miami were recruited to form the main invasion force, which came to be known as “Brigade 2506” (Brigade 2506 actually consisted of five infantry brigades and

one paratrooper brigade). The majority of Brigade 2506 received training in conventional warfare in a U.S. base in Guatemala, while other members took specialized combat instructions in Puerto Rico and

various locations in the United States.

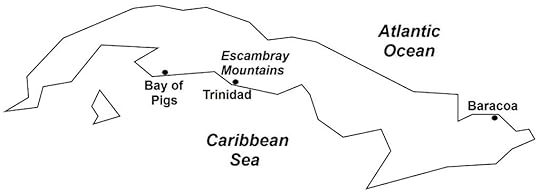

Cuba showing location of Trinidad, which was the first proposed site of the CIA-sponsored Brigade 2506 invasion, and the Bay of Pigs, where the landings took place.

The CIA wanted to maintain utmost secrecy in order to conceal the U.S. government’s involvement in the invasion. Through loose talk, however, the plan came to be widely known among the Miami Cubans, which eventually was picked up by the American media and then by the foreign press. On January 10, 1961, a front-page news item in the New York Times read “U.S. helps train anti-Castro Force At Secret Guatemalan Air-Ground Base”. Castro’s intelligence operatives in Latin America also learned of the plan; in October 1960, the Cuban foreign minister presented evidence of the existence of Brigade 2506 at a session of the United Nations General Assembly.

In January 1961, the CIA gave newly elected U.S.

president, John F. Kennedy, together with his Cabinet, details of the Cuban invasion plan. The State Department raised a number of objections, particularly with regards to the proposed landing site of Trinidad, which was a heavily populated town in south-central Cuba (Map 30). Trinidad had the benefits of being a defensible landing site and was located adjacent to the Escambray Mountains, where many anti-Castro guerilla groups operated. State officials were concerned, however, that Trinidad’s conspicuous location and large

population would make American involvement difficult to conceal.

As a result, the CIA rejected Trinidad, and proposed a new landing site: the Bay of Pigs (Spanish: Bahia de Cochinos), a remote, sparsely inhabited narrow inlet west of Trinidad. President Kennedy then gave his approval, and final preparations for the invasion were made. (The “Cochinos” in Bahia de Cochinos, although translated into English as “pigs” does not refer to swine but to a species of fish, the orange-lined triggerfish, found in the coral waters around the area).

The general premise of the invasion was that most Cubans were discontented with Castro and wanted to see his government deposed. The CIA believed that once Brigade 2506 began the invasion, Cubans would rise up against Castro, and the Cuban Army would defect to the side of the invaders. Other anti-government guerilla groups then would join Brigade 2506 and incite a civil war that ultimately would overthrow Castro. Thereafter, a provisional government, led by Cuban exiles in the United States,

ould arrive in Cuba and lead the transition to democracy.

April 19, 2020

April 19, 1990 – Nicaraguan Civil War: The Sandinista government and Contra rebels agree to a ceasefire

By 1987, the Contra rebels were demoralized and suffered desertions because of their failure to win territories, diminished U.S. funding, and corruption of their leaders. The Sandinista government also was weary from the decades of war; it also faced a restive population that longed for peace.

In an earlier meeting held in Guatemala in August 1987, the leaders of Central American countries had agreed to work together to bring about peace in the region and in their respective troubled countries (i.e. the leftist insurgencies in Guatemala and El Salvador, the military dictatorship in Panama, a right-wing insurgency in Nicaragua, and political unrest in Honduras). In March 1988, Contra rebels agreed to hold peace talks with the Nicaraguan government, despite fierce opposition by the Reagan administration. Subsequently, on April 19, 1990, the Sandinista government and Contra rebels signed a ceasefire agreement pending Nicaragua’s return to democracy and the holding of free elections.

Nicaragua in Central America.

(Taken from Nicaraguan Revolution and Counter-Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Revolution

In 1961, the revolutionary movement called the Sandinista National Liberation Front was formed in Nicaragua with two main objectives: to end the U.S.-backed Somoza regime, and establish a socialist government in the country. The movement and its members, who were called Sandinistas, took their name and ideals from Augusto Sandino, a Nicaraguan rebel fighter of the 1930s, who fought a guerilla war against the American forces that had invaded and occupied Nicaragua. Sandino also wanted to end the Nicaraguan wealthy elite’s stranglehold on society.

He advocated for social justice and economic equality for all Nicaraguans.

By the late 1970s, Nicaragua had been ruled for over forty years by the Somoza family in a dynastic-type succession that had begun in the 1930s. In 1936, Anastacio Somoza seized power in Nicaragua

and gained total control of all aspects of the government. Officially, he was the country’s president, but ruled as a dictator. Over time, President Somoza accumulated great wealth and owned the biggest landholdings in the country. His many personal and family businesses extended into the shipping and airlines industries, agricultural plantations and cattle ranches, sugar mills, and wine

manufacturing. President Somoza took bribes from foreign corporations that he had granted mining concessions in the country, and also benefited from local illicit operations such as unregistered gambling, organized prostitution, and illegal wine production.

President Somoza suppressed all forms of opposition with the use of the National Guard, Nicaragua’s police force, which had turned the country into a militarized state. President Somoza was staunchly anti-communist and received strong military and financial support from the United States, which was willing to take Nicaragua’s repressive government as an ally in the ongoing Cold War.

Nicaraguan Revolution (1961-1979). Communist rebels called Sandinistas fought to overthrow the autocratic regime of Anastacio Somoza. The Somoza dynasty ended when the rebels captured Managua, Nicaragua’s capital.

In 1956, President Somoza was assassinated and was succeeded by his son, Luis, who also ruled as a dictator until his own death by heart failure in 1967. In turn, Luis was succeeded by his younger brother, Anastacio Somoza, who had the same first name as their father. As Nicaragua’s new head of state, President Somoza outright established a harsh regime much like his father had in the 1930s. Consequently, the Sandinistas intensified their militant activities in

the rural areas, mainly in northern Nicaragua. Small bands of Sandinistas carried out guerilla operations, such as raiding isolated army outposts and destroying

government facilities.

By the early 1970s, the Sandinistas comprised only a small militia in contrast to Nicaragua’s U.S.-backed National Guard. The Sandinistas struck great fear on President Somoza, however, because of the

rebels’ symbolic association to Sandino. President Somoza wanted to destroy the Sandinistas with a passion that bordered on paranoia. He ordered his

forces to the countryside to hunt down and kill Sandinistas. These military operations greatly affected the rural population, however, who began to fear as well as hate the government.

The end of the Somoza regime began in 1972 when a powerful earthquake hit Managua, Nicaragua’s capital. The destruction resulting from the earthquake caused 5,000 human deaths and 20,000 wounded, and left half a million people

homeless (nearly half of Managua’s population). Managua was devastated almost completely, cutting off all government services. In the midst of the destruction, however, President Somoza diverted the

international relief money to his personal bank account, greatly reducing the government’s meager resources. Consequently, thousands of people were deprived of food, clothing, and shelter.

Business owners in Managua also were affected by the earthquake and railed at the government’s corruption and ineptitude to deal with the tragedy.

Consequently, many businesses closed, causing many workers to lose their jobs and worsen the country’s dire unemployment situation. Nicaragua’s political opposition, which formed a broad spectrum from the far left to the moderate right, became much more vocal in its criticism of the government. For the opposition, the Sandinistas’ overthrow of President Somoza did not seem as repugnant as before.

In December 1974, Sandinista rebels took hostage a number of high-ranking government officials, including some of President Somoza’s

relatives. After negotiations were held between the government and the rebels, President Somoza agreed to pay a large ransom for the hostages’ release. Furthermore, President Somoza was forced to free a number of jailed Sandinistas. The success of the hostage taking greatly raised the people’s perception of the Sandinistas and also shattered the purported invincibility of President Somoza.

President Somoza retaliated by imposing a state of siege across the country. He ordered the National Guard to conduct a campaign of terror in the countryside. Consequently, the military committed many atrocities against rural civilians. As Nicaragua’s human rights situation deteriorated, U.S. president Jimmy Carter exerted diplomatic pressure on the Somoza regime. With President Somoza continuing his repressive policies, however, the U.S. government suspended military assistance to Nicaragua in February 1978.

Later in the year, Sandinista fighters seized Nicaragua’s National Legislature and took hostage hundreds of lawmakers and high-ranking government officials. Once again, President Somoza was forced to negotiate and then yield to the rebels’ demands

that included paying a big ransom for the hostages’ release and freeing more political prisoners.

Nicaragua’s opposition parties united and tried to negotiate with the national government. By the end of 1978, however, President Somoza’s intransigence had led many in the political opposition to lose hope for a peaceful solution to the country’s political crisis.

In early 1979, the Sandinistas succeeded in reuniting rival factions after experiencing a power struggle that nearly broke the organization. The Sandinistas formed an alliance with and subsequently led a coalition of opposition parties that included communists, socialists, Liberals, Conservatives, and centrists.

The Sandinistas received weapons from Cuba, Venezuela, and Panama. Then in March 1977, from their bases in northern Nicaragua and in Costa Rica, the Sandinistas launched more potent attacks against National Guard units (Map 24). By early June 1979, the Sandinistas had captured the whole northern section of the country. On June 16, the strategic city of Leon fell to the rebels. On June 20, the United States broke off diplomatic relations with the Somoza regime following the brazen killing of an American news reporter by a Nicaraguan soldier. The assault on the American journalist was caught on live TV, generating outrage and condemnation from the American people.

By early July 1979, the Sandinistas had surrounded Managua; the rest of the country had already fallen into their hands. With his government on the brink of collapse, President Somoza fled from

the country on July 17. His assassination by Sandinista commandos in Paraguay the following year

completed the full turn-around of the Somoza-Sandino saga.

On July 19, 1979, Sandinista forces entered Managua where huge crowds welcomed them as

liberators. Following President Somoza’s overthrow, a civilian junta that had been set up earlier by the opposition coalition began to rule the country. The

junta represented a cross-section of the political opposition and was structured as a power-sharing government.

Non-Sandinista members of the junta soon resigned, however, as they felt powerless against the Sandinistas (who effectively controlled the junta) and feared that the government was moving toward adopting Cuban-style socialism.

By 1980, the Sandinistas had taken full control of the government. The country had been devastated by the war, as well as by the corruption and neglect by the previous dictatorial regimes. Using the limited

resources available, the Sandinista government launched many programs for the general population. The most successful of these programs were in public education, where the country’s high illiteracy rate was lowered significantly, and in agrarian reform, where large landholdings, including those of ex-President Somoza, were seized and distributed to the peasants and poor farmers. The Sandinista government also implemented programs in health care, the arts and culture, and in the labor sector.

U.S. president Carter was receptive to the Sandinista government. But President Ronald Reagan, who succeeded as U.S. head of state in January 1981, was alarmed that Nicaragua had allowed a communist toehold in the American continental mainland, and therefore posed a threat to the United States. President Reagan believed that the Sandinistas planned to spread communism across Central America. As evidence of this perception, President Reagan pointed out that the Sandinistas were arming the communist insurgents in El Salvador. Consequently, President Reagan prepared plans for a counter-revolution in Nicaragua that would overthrow the Sandinista government.

Counter-Revolution President

Reagan cut off financial assistance to Nicaragua in January 1981 (his first month as president) in order to undermine the Sandinista government. Then in the summer through autumn of 1981, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) formed an armed militia consisting of remnants of Nicaragua’s former National Guard who had fled to Honduras after President Somoza’s overthrow. The CIA subsequently also organized other anti-Sandinista militias based in Honduras and Costa Rica. These CIA-backed militias collectively were called “Contras” which was shortened from the Spanish word “contrarevolution”,

or counter-revolution. The Contras’ principal aim was to overthrow the Sandinista government.

The Contras were most active in the northern, central, and western regions of the country. Operating in western Nicaragua were small Contra militias composed of local indigenous peoples who opposed the government’s expropriation of their ancestral lands. Another Contra militia led by an

ex-Sandinista commander fought out of the Rio San Juan region.

The Contra War, as the conflict was known, did not threaten seriously the Sandinista regime, but it devastated much of the country, especially in the rural areas. The United States, supported by other Western countries, imposed an arms embargo on Nicaragua, forcing the Sandinista government to purchase weapons from the Soviet Union. Because of the Contra insurgency, the Nicaraguan government tried to force military conscription. The civilian population resisted fiercely, however, with riots and protests breaking out in some areas. The war devastated Nicaragua’s economy, particularly in regions affected by the fighting. Furthermore, the United States, which purchased 90% of Nicaragua’s exports, imposed a trade embargo against that Central American country.

The Contras committed many atrocities against civilians: summary executions, tortures, rapes, lootings, and arson occurred frequently during the war. When reports of these atrocities reached the United States, the U.S. Congress, in 1985, cut off

funding to the Contras. Other factors that influenced the U.S. Congress’ decision were: the American public generally was not sympathetic to the Contras; the CIA was implicated in the mining of Nicaraguan ports; President Reagan’s surreptitious conduct of the war; and the minor involvement of the Soviet Union in the war, despite contrary claims by the U.S. government.

The Reagan administration was determined to continue supporting the Contras despite the U.S. Congress legislation. The CIA and the National Security Council (NSC) devised a plan whereby American weapons were sold secretly to Iran (which was then embroiled in a bitter war with Iraq

called the “Iran-Iraq War”). The proceeds from the weapons’ sales were then used to fund the Contras. American authorities discovered the scheme, however, leading to an investigation by U.S. Congress. Consequently, government officials in the Reagan administration were implicated. Further damning U.S. involvement were allegations that the CIA trafficked illegal narcotics from Central America to the United States and then used the proceeds from the drugs’ sales to fund the Contras.

Meanwhile in Nicaragua, bitter fighting occurred in the Zelaya Provinces in December 1987 and near the Honduran border in March 1988. The war was going nowhere, however, with human casualties topping 40,000 and rising daily. The Contras were demoralized and suffered desertions because of their failure to win territories, diminished U.S. funding, and corruption of their leaders. The Sandinista government also was weary from the decades of war; it also faced a restive population that longed for peace.

In an earlier meeting held in Guatemala in August 1987, the leaders of Central American countries had agreed to work together to fbring about peace in the region and in their respective troubled countries (i.e. the leftist insurgencies in Guatemala and El Salvador, the military dictatorship in Panama, a right-wing insurgency in Nicaragua, and political unrest in Honduras). In March 1988, Contra rebels agreed to hold peace talks with the Nicaraguan government, despite fierce opposition by the Reagan administration. Subsequently, a ceasefire was agreed, pending Nicaragua’s return to democracy and the holding of free elections.

Then in general elections held in February 1990, the Sandinistas lost control of the government in a stunning defeat. A new government was formed consisting of a broad coalition of many opposition political parties. Consequently, the Contras voluntarily laid down their weapons and returned to the fold of the law. Nicaragua’s three decades of war

finally came to an end.

April 18, 2020

April 18, 1951 – Post-World War II reconstruction of Europe: Formation of the European Steel and Coal Community

Vital to post-World War II reconstruction was the economic integration of Western Europe, which was promoted by the Marshall Plan and spurred on further by the formation of the International Authority of the Ruhr (IAR) in April 1949, where the Allied Powers set limits to the German coal and steel industries. By 1952, with West Germany firmly aligned with the Western democracies, the IAR was abolished and replaced by the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which integrated the economies of France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The ECSC was established on April 18, 1951, with its original intent as a means to prevent further war between France and Germany. By establishing a common market for coal and steel, competition among member nations over these resources would be neutralized. In 1957, the ECSC was succeeded by the European Economic Community (EEC), which later led to the European Union (EU) in 1993.

(Taken from The End of World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Post-war reconstruction and start of the Cold War

Europe was devastated after the war, many millions of people lost their lives, and many millions others lost their homes and livelihoods. Industries were destroyed, and farm lands laid waste, leading to massive food shortages, famines, and more

fatalities. Whole national economies were bankrupt, expended largely toward supporting the war effort.

The United States, whose economy grew enormously during the war, poured into Europe

large amounts of financial and humanitarian support (U.S. $13 billion; U.S. $165 billion in 2017 value) toward the continent’s reconstruction. American assistance was directed mainly toward its war-time Western Allies and formerly occupied nations. U.S.

policy toward Germany in the immediate post-war period was one of hostility and indifference, implemented under JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff) Directive 1067, which stipulated “to take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany”. At this time, Germany was divided into four Allied zones of occupation, and stripped of its heavy industries and scientific and technical intellectual properties, including patents, trademarks, and copyrights.

The Allies also severely restricted access to Germany for international humanitarian agencies (e.g. International Red Cross) sending food, leading to low nutritional levels and hunger among Germans, which caused high mortality and malnutrition rates among children and the elderly. The Allies deliberately limited Germany’s procurement of food to the barest minimum, to a level just enough to prevent civil unrest or revolts, which could compromise the safety of occupation troops. By 1946, the Allies began to

gradually ease these restrictions, and many donor agencies opened in Germany to provide food and humanitarian programs.

By 1947, Europe’s economic recovery was moving forward only slowly, despite the massive infusion of American funds. Farm production was only 83% of pre-war levels, industrial output only 88%, and exports just 59%. High levels of unemployment and food shortages caused labor strikes and social unrest. Before the war, Europe’s

economy had been linked to German industries through the exchange of raw materials and manufactured goods. In 1947, the United States

decided that Germany’s participation in Europe’s economy was necessary, and the Western Allied plan to de-industrialize Germany was ended. In July 1947, the U.S. government scrapped JCS 1067, and replaced it with JCS Directive 1779, which stated that “an orderly and prosperous Europe requires the economic contribution of a stable and productive Germany”. Restrictions on German industry production were eased, and steel output was raised from 25% to 50% of pre-war capacity.

In April 1948, the United States implemented a massive assistance program, the European Recovery Plan, more commonly known as the Marshall Plan (named after U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall), where the U.S. government poured in $5 billion ($51 billion in 2017 value) in 1948 in financial aid toward European member-states of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC). In the

Marshall Plan, which lasted until the end of 1951, the United States donated $13 billion ($134 billion in 2017 value) to 18 countries, with the largest amounts given to Britain (26%), France (18%), and West Germany (11%). Other beneficiaries were Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal,

Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and Trieste. After the Marshall Plan ended in 1952, another program, the Mutual Security Plan, poured in $7 billion ($63 billion in 2017 value) annual recovery assistance to Europe

until 1961. By the early 1950s, Western Europe’s productivity had surpassed pre-war levels, and the region would go on to enjoy prosperity in the next two decades.

Also significant was the economic integration of Western Europe, which was promoted by the Marshall Plan and spurred on further by the formation of the International Authority of the

Ruhr (IAR) in April 1949, where the Allied Powers set limits to the German coal and steel industries. By 1952, with West Germany firmly aligned with the Western democracies, the IAR was abolished and replaced by the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which integrated the economies of France,

West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. In 1957, the ECSC was succeeded by the European Economic Community (EEC), which later led to the European Union (EU) in 1993.

The Marshall Plan had been offered to the Soviet

Union, but which Stalin rejected. The Soviet leader also strong-armed Eastern and Central European

countries under Soviet occupation not to participate, including Poland and Czechoslovakia, which had shown interest. Stalin was determined to achieve a political stranglehold on the emerging communist governments of Hungary, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Albania. Participation of these countries in the Marshall Plan would have allowed American involvement in their economies, which Stalin opposed.

Relations between the Soviet Union and the Western Powers, the United States and Britain, deteriorated during the Yalta Conference (February 1945) when victory in the war became clear, because of disagreement regarding the post-war future of Poland in particular, and Eastern and Central Europe in general. In April 1945, new U.S. President Truman announced that his government would take a firmer stance against the Soviet Union more than his

predecessor, President Roosevelt. Following the end of the war, the United States, Britain, and France were wary of the continued Red Army occupation of Eastern and Central Europe, and feared that the Soviets would use them as a staging ground for the conquest of the rest of Europe and the spread of communism. In war-time Allied conferences, Stalin had demanded a sphere of political influence in Eastern and Central Europe to serve as a buffer against another potential invasion from the West. In turn, Stalin saw the presence of U.S. forces in Europe as a plot by the United States to gain control of and impose American political, economic, and social ideologies on the continent. In February 1946, Stalin announced that war was inevitable between the opposing ideologies of capitalism and communism.

George Kennan, an envoy in the U.S. diplomatic office in Moscow, then sent to the U.S. State Department the so-called “Long Telegram”, which

warned that the Soviets were unwilling to have “permanent peaceful coexistence” with the West, was bent on expansionism, and was prepared for a “deadly struggle for total destruction of rival powers”. The telegram proposed that the United States should confront the Soviet threat by implementing firm political and economic foreign policies. Kennan’s proposed hard-line stance against the Soviet Union was eventually adopted by the Truman government.

In September 1946, in response to the “Long Telegram”, the Soviets accused the United States

of “striving for world supremacy”.

In March 1946, civil war broke out in Greece between the local communist and monarchist forces.

Also that month, Churchill delivered his “Iron Curtain” speech, where he stated that an “iron curtain” had descended across Eastern Europe, and warned of further Soviet expansionism into Europe. In reply, Stalin accused Churchill of “war mongering”.

American foreign policy in the post-war era finally took shape in March 1947 with the Truman Doctrine, which arose from a speech by President Truman before the U.S. Congress, where he stated that his

administration would “support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures”. President Truman gave reference to supporting friendly forces in the on-going Greek Civil War after the British had announced the end of their involvement in the conflict. Truman also requested U.S. Congress support for Greece’s neighbor, Turkey, which was being pressured by Stalin to grant Soviet base and transit rights through the Turkish Straits. Russian troops also continued to occupy northern Iran

despite the Soviet government’s war-time promise to leave when the war ended. To the Truman administration, a communist victory in Greece,

and the absorption of Turkey and Iran into the Soviet sphere of influence would lead to Soviet expansion into the oil-rich Middle East.

The Truman Doctrine of “containing” Soviet expansionism is generally cited as the trigger for the Cold War, the ideological rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union in particular, and the forces of democracy and communism in general. By the late 1940s, with the apparent threat of imminent war looming, the Western European democracies: Britain, France, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg,

Portugal, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland, and the United States and Canada, formed a military alliance called the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

in April 1949. Then in May 1955, with the entry of West Germany into NATO and the formation of the West German Armed Forces, the alarmed Soviet Union established a rival military alliance called

the Warsaw Pact (officially: Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation, and Mutual Assistance) with its socialist satellite states: East Germany, Poland, Hungary,

Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania.

The stage thus was set for the ideological and military division of Europe that lasted throughout the Cold War.

April 17, 2020

April 17, 1961 – Bay of Pigs Invasion: CIA-trained Cuban exiles land in Cuba to overthrow Fidel Castro

Cuban exiles who formed the invasion force called “Brigade 2506” set off from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, for the invasion of Cuba.

(Taken from Bay of Pigs Invasion – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Invasion

On April 13, 1961, Brigade 2506, consisting of 1,400 soldiers, set off from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua for Cuba aboard five chartered ships, and accompanied by two landing crafts and other auxiliary vessels. The invasion plan called for initially destroying the Cuban Air Force. Thus, in the early morning of April 15, U.S. bombers, painted with Cuban Air Force markings, took off from an airfield in Nicaragua and attacked the three major Cuban airbases located in Havana and Santiago de Cuba, destroying several aircraft on the ground as well as damaging the runways and other air facilities. Many ground targets were not hit, however, leaving the Cuban Air Force generally intact. Following the attacks, the Cuban police increased surveillance operations against suspected anti-Castro elements, which led to some 20,000 persons being arrested and imprisoned.

A U.S. bomber plane, also bearing the false Cuban Air Force markings, departed from Nicaragua and later landed in Miami, Florida, where its pilot, an anti-Castro Cuban exile, posed as an officer of the Cuban Air Force who was seeking to defect to the United States. However, the ruse was detected by news

reporters who examined the plane, with the U.S. media soon releasing the story to the public.

Cuba showing location of Trinidad, which was the first proposed site of the CIA-sponsored Brigade 2506 invasion, and the Bay of Pigs, where the landings took place.

To provide a feint for the invasion at the Bay of Pigs, on April 15 and 16, a diversionary landing was made near Baracoa, Oriente Province. The attempt was cancelled, however, because of the presence of Cuban military activity ashore. Just before midnight on April 16, the ships carrying Brigade 2506 reached the waters off the Bay of Pigs, but were slowed on their approach by coral reefs that had been misidentified as seaweeds by American air reconnaissance.

Three beaches were designated as landing sites: Playa Giron (the main invasion zone), Caleta Buena (located 13 kilometers away), and Playa Larga (located at the north end of the Bay of Pigs). At 1 a.m. on April 17, the landing crafts began transporting the troops to shore. The transport ship Houston had to slowly traverse the narrow Bay of Pigs inlet into

Playa Larga and then was delayed further by unloading glitches; the unloading process itself produced so much noise, violating strict orders to maintain full silence. Furthermore, the advance

landing team of commandos was detected by a Cuban militia patrol on shore, which led to a brief exchange of gunfire where the Cuban patrol was easily overpowered. The commandos secured the

beaches for the landings, but the firefight had alerted other militias, who sounded the general alarm at 3 a.m.

On the night of April 16, another mock amphibious landing was carried out at Bahia Honda, 65 kilometers west of Havana. The ruse drew the attention of the Cuban Armed Forces, which were now in a high state of war alert, away from other areas and especially from the Bay of Pigs, which was not considered a likely invasion point and therefore was only lightly defended. The unloading of the Houston at Playa Larga, planned for 90 minutes, was so disorganized that by daybreak, only half the number of its troops had been brought to shore.

At 6:30 a.m. Cuban planes began attacking the ships. A day earlier, April 16, President Kennedy

had cancelled the air strike that was planned for April 17; the second strike would have targeted the remaining Cuban Air Force planes that had escaped the April 15 attacks. Furthermore, President Kennedy reduced in half Brigade 2506’s air support from 16 bomber planes to 8. These changes prevented the invasion from gaining full control of the sky, and in fact allowed the Cuban Air Force to operate freely.

The American second air strike having been cancelled, the Bay of Pigs landings were carried out without air support. Furthermore, the transport

ships lacked effective anti-aircraft weapons, being equipped only with .50 caliber machineguns. The Houston soon was hit by the Cuban air attacks, forcing the captain to beach the ship in order to allow the remaining unloaded troops to reach shore, which they did using lifeboats or by swimming. Many of these soldiers lost their weapons and thereafter failed to contribute effectively to the war effort; furthermore, much of the equipment on board the ship could not be unloaded and was abandoned.

A few hours later, Rio Escondido, the main cargo ship, was hit and sunk, losing a vital supply of ammunition for the tanks and heavy weapons that had been landed, as well as fuel for the armored vehicles and aircraft, food supplies, and the main communications equipment. The remaining transport ships and landing vessels withdrew to the open sea because of the danger of more Cuban air attacks, as well as from the artillery batteries that the Cuban forces now brought close to shore. The transport

ships soon were given orders to leave and return to Nicaragua. Much of the weapons, food, and medical

supplies from the ships had not been unloaded, greatly jeopardizing the operation.

Brigade 2506 paratroopers were airdropped at two locations further inland from the beaches, at Palpite and San Blas, to serve as a blocking force and to secure the roads leading to the landing zones. Much of the paratroopers’ equipment landed into the surrounding swamps and was lost. Playa Giron came under the control of Brigade 2506, which also seized

the nearby runway for the invasion’s bomber planes. The bombers soon began launching air strikes

against Cuban military positions, but the loss of five of the eight planes during the day gave the Cuban Air Force a clear advantage in the air war.

By mid-morning on April 17, Castro had mobilized the Cuban Army and regional militias, sending an advance force of 20,000 soldiers and auxiliary fighters from the north and east toward the Bay

of Pigs. In total, some 50,000 Cuban soldiers and militia fighters took part in the war. The sheer weight of the Cuban Army advance forced Brigade 2506 paratroopers to withdraw from Palpite, which then was recaptured by government forces. Other Castro

units sealed off the roads leading to Covadonga and Yaguaramas. By the end of the first day, Castro’s forces had contained the landings to the Bay of Pigs

and nearby areas, with little chance of a break out; Brigade 2506 was practically trapped on all sides, except from the sea.

Background

The rise to power of Fidel Castro after his victory in ethe Cuban Revolution (previous article) caused great concern for the United States. Castro formed a government that adopted a socialist state policy and opened diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and other European communist countries. After the Cuban government seized and nationalized American companies in Cuba, the United States imposed a trade embargo on the Castro regime and subsequently ended all economic and diplomatic

relations with the island country.

Then in July 1959, just seven months after the Cuban Revolution, U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower delegated the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with the task of overthrowing Castro, who had by then gained absolute power as dictator. The CIA devised a number of methods to try and kill the Cuban leader, including the use of guns-for-hire and assassins carrying poison-laced devices. Other schemes to destabilize Cuba also were carried out, including

sending infiltrators to conduct terror and sabotage operations in the island, arming and funding anti-Castro insurgent groups that operated especially in the Escambray Mountains, and by being directly involved in attacking and sinking Cuban and foreign merchant vessels in Cuban waters and by launching air attacks in Cuba. These CIA operations ultimately

failed to eliminate Castro or permanently destabilize his regime.

In March 1960, the CIA began to plan secretly for the invasion of Cuba, with the full support of the Eisenhower administration and the U.S. Armed Forces. About 1,400 anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Miami were recruited to form the main invasion force, which came to be known as “Brigade 2506” (Brigade 2506 actually consisted of five infantry brigades and

one paratrooper brigade). The majority of Brigade 2506 received training in conventional warfare in a U.S. base in Guatemala, while other members took specialized combat instructions in Puerto Rico and

various locations in the United States.

The CIA wanted to maintain utmost secrecy in order to conceal the U.S. government’s involvement in the invasion. Through loose talk, however, the plan came to be widely known among the Miami Cubans, which eventually was picked up by the American media and then by the foreign press. On January 10, 1961, a front-page news item in the New York Times read “U.S. helps train anti-Castro Force At Secret Guatemalan Air-Ground Base”. Castro’s intelligence operatives in Latin America also learned of the plan; in October 1960, the Cuban foreign minister presented evidence of the existence of Brigade 2506 at a session of the United Nations General Assembly.

In January 1961, the CIA gave newly elected U.S. president, John F. Kennedy, together with his Cabinet, details of the Cuban invasion plan. The State Department raised a number of objections, particularly with regards to the proposed landing site of Trinidad, which was a heavily populated town in south-central Cuba (Map 30). Trinidad had the benefits of being a defensible landing site and was located adjacent to the Escambray Mountains, where many anti-Castro guerilla groups operated. State officials were concerned, however, that Trinidad’s conspicuous location and large population would make American involvement difficult to conceal.

As a result, the CIA rejected Trinidad, and proposed a new landing site: the Bay of Pigs (Spanish: Bahia de Cochinos), a remote, sparsely inhabited narrow inlet west of Trinidad. President Kennedy then gave his approval, and final preparations for the invasion were made. (The “Cochinos” in Bahia de Cochinos, although translated into English as “pigs” does not refer to swine but to a species of fish, the orange-lined triggerfish, found in the coral waters around the area).

The general premise of the invasion was that most Cubans were discontented with Castro and wanted to see his government deposed. The CIA believed that once Brigade 2506 began the invasion, Cubans would rise up against Castro, and the Cuban Army would defect to the side of the invaders. Other anti-government guerilla groups then would join Brigade 2506 and incite a civil war that ultimately would overthrow Castro. Thereafter, a provisional government, led by Cuban exiles in the United States,

would arrive in Cuba and lead the transition to democracy.

April 16, 2020

April 16, 1945 – World War II: The start of the Battle of Berlin, with one million Soviet troops attacking the heavily fortified Seelow Heights

On April 16, 1945, the Soviet Red Army launched its offensive, opening a preliminary massive artillery bombardment that landed on the mostly undefended banks of the Oder River. Soviet ground forces then advanced, with much of the heaviest fighting centered on the strongly fortified Seelow Heights, where Marshal Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, comprising 1 million troops and 20,000 tanks advanced head on to German 9th Army’s 100,000 troops and 1,200 tanks. By the fourth day, the Soviets had broken through, sustaining heavy losses of 30,000 killed and 800 tanks destroyed, against 12,000 German casualties.

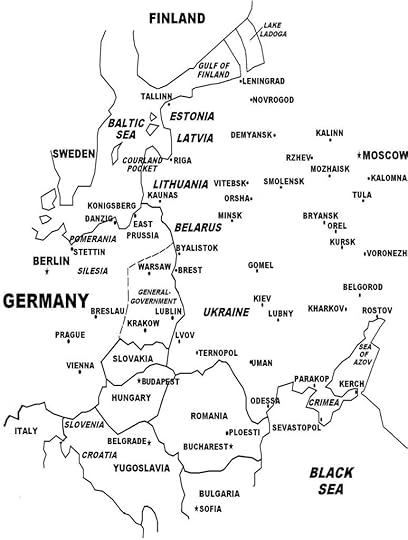

The series of massive Soviet Counter-Offensives recaptured lost Soviet territory and then swept through Eastern and Central Europe into Germany.

The series of massive Soviet Counter-Offensives recaptured lost Soviet territory and then swept through Eastern and Central Europe into Germany.(Taken from Soviet Counter-Attack and Defeat of Germany – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Berlin and Defeat of

Germany The Soviet offensive into Germany centered on Stalin’s two main

objectives: that the Red Army was to rapidly push far to the west as possible

to beat the Western Allies into capturing as much German territory as possible;

and that Berlin was to fall into Soviet hands, first, to deal with Hitler and

second, to gain possession of Germany’s nuclear research program. For the campaign, Stalin tasked three Soviet

Army Groups, together with the Red Army’s best commanders: 1st Belorussian

Front led by Marshal Georgy Zhukov; 2nd Belorussian Front led by Marshal

Konstantin Rokossovsky, to the north of Zhukov’s forces; and 1st Ukrainian

Front led by Marshal Ivan Konev, to the south of Zhukov’s forces. The combined forces were massive: 2.5 million

troops, including 200,000 Polish soldiers, 6,200 tanks, 42,000 artillery

pieces, and 7,500 planes.

For the defense of outer Berlin, the Wehrmacht mustered 800,000

troops, 1,500 armored vehicles, 9,300 artillery pieces, and 2,200 planes. The main defensive lines for the eastern

approaches to the city were located 56 miles (90 km) at Seelow Heights

and manned by German 9th Army. The

German military had taken advantage of the delayed Soviet offensive on Berlin to construct

these defenses. The Germans positioned

these lines 10 miles (17 km) west of the Oder River,

which would prove significant in the coming battle.

On April 16, 1945, the Red Army launched its offensive,

opening a preliminary massive artillery bombardment that landed on the mostly

undefended banks of the Oder

River. Soviet ground forces then advanced, with much

of the heaviest fighting centered on the strongly fortified Seelow Heights,

where Marshal Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, comprising 1 million troops and

20,000 tanks advanced head on to German 9th Army’s 100,000 troops and 1,200

tanks. By the fourth day, the Soviets

had broken through, sustaining heavy losses of 30,000 killed and 800 tanks

destroyed, against 12,000 German casualties.

To the south, Marshal Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front also broke

through, with lead elements advancing through open country to the west which

would eventually meet up with U.S. Army troops at the Elbe

River, and armored units advancing

rapidly toward Berlin. A race now developed between Marshals Zhukov

and Konev on who would capture Berlin

first.

Marshall Konev’s offensive trapped German 9th Army in a

large pocket west of Frankfurt. In a pincers movement, forces of Zhukov and

Konev advanced through the periphery of Berlin,

closing shut to the rear and encircling the city on April 24. Meanwhile, Marshall Rokossovsky’s 2nd

Ukrainian Front positioned north of Berlin, thrusting on April 20, broke

through German 3rd Panzer Army at Stettin, and advanced rapidly west, soon

meeting up with elements of the British Army at Stralsund in the Baltic coast.

On April 24, the battle for the inner city of Berlin began,

with some 1.5 million Soviet troops facing Berlin Defence Area units, a motley

of Wehrmacht units (45,000 troops), Berlin police, Hitler Youth, and the Nazi

Party’s Home Guard “Volkssturm” militia (40,000 armed civilians). Hitler, who directed the battle from his

underground bunker in Berlin, and who yet believed that the war was not lost,

ordered German 12th Army (deployed to confront the Western Allies) to head for

Berlin and link up with the trapped German 9th Army, and for the combined units

to encircle and destroy the two Soviet Army Groups in Berlin, which was an

utterly impossible task. German 12th

Army ran into a Soviet stonewall and was forced back, but battered elements of

German 9th Army (some 30,000 of the original 200,000 troops) maneuvered through

gaps in the Soviet cordon, and both formations retreated to the west and

surrendered to the Western Allies.

By late April 1945, for the Germans, the battle of Berlin and the wider war in Europe

and World War II were lost. On April 30,

Hitler took his own life in his underground bunker below the Reich Chancellery

in Berlin

just as Soviet troops were closing in.

On May 2, Berlin

fell as the city’s garrison surrendered to the Red Army.

Admiral Karl Doenitz, head of the German Navy, took over as

head of state and president of Germany, succeeding as such as mandated in

Hitler’s last will and testament. With

the Third Reich falling apart and the Wehrmacht defeated, Admiral Doenitz was

determined to end the war – as quickly as possible with the Western Allied

Powers, but to delay as much with the Soviet Union. The idea was to allow the many scattered

German units in the east and facing the Red Army to turn around and make a