Daniel Orr's Blog, page 102

April 1, 2020

April 2, 1948 – Civil War in Palestine: Jewish forces advance toward Jerusalem to lift the siege on the city

On April 2, 1948, Jewish forces advanced toward Jerusalem in order to lift the siege on the city and allow the entry of supply vehicles. The Jews cleared the roads of Arab fighters and took control of the Arab villages nearby. The operation was only partially successful, however, as Jewish delivery convoys continued to be ambushed along the roads. Furthermore, Jewish authorities were condemned by the international community after a Jewish attack on the Arab village of Deir Yassin resulted in the deaths of over one hundred Arab civilians.

United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. The original plan released by the UN proposed to allocate 56% of Palestine to Jews, while 43% would be allotted to Palestinian Arabs. Jerusalem, at 1% of the territory, would be administered by the UN.

(Taken from 1947 – 1948 Civil War in Palestine – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background

Through a League of Nations mandate, Britain administered Palestine from 1920 to 1948. For nearly all that time, the British rule was plagued by violence between the rival Arabs and Jewish populations that resided in Palestine. The Palestinian Arabs resented the British for allowing the Jews to settle in what the Arabs believed was their ancestral

land. The Palestinian Jews also were hostile to the British for limiting and sometimes even preventing other Jews from entering Palestine. The Jews believed that Palestine had been promised to them as the site of their future nation. Arabs and Jews clashed against each other; they also attacked the British authorities. Bombings, massacres, assassinations, and other violent civilian incidents occurred frequently in Palestine.

By the end of World War II in 1945, nationalist aspirations had risen among the Palestinian Arabs and Palestinian Jews. Initially, Britain proposed an independent Palestine consisting of federated states of Arabs and Jews, but later deemed the plan unworkable because of the uninterrupted violence. The British, therefore, referred the issue of

Palestine to the United Nations (UN). The British also announced their intention to give up their mandate over Palestine, end all administrative functions there, and withdraw their troops by May 15, 1948. The last British troops actually left on June 30, 1948.

The UN offered a proposal for the partition for Palestine (Map 8) which the UN General Assembly subsequently approved on November 29, 1947. The Palestinian Jews accepted the plan, whereas the Palestinian Arabs rejected it. The Palestinian Arabs took issue with what they felt was the unfair division of Palestine in relation to the Arab-Jewish population ratio. The Jews made up 32% of Palestine’s population but would acquire 56% of the land. The Arabs, who comprised 68% of the population, would gain 43% of Palestine. The lands proposed for the Jews, however, had a mixed population composed of 46% Arabs and 54% Jews. The areas of Palestine allocated to the Arabs consisted of 99% Arabs and 1% Jews. No population transfer was proposed. Jerusalem and its surrounding areas, with their mixed population of 100,000 Jews and an equal number of Arabs, were to be administered by the UN.

War

Shortly after the UN approved the partition plan, hostilities broke out in Palestine. Armed bands of Jews and Arabs attacked rival villages and settlements, threw explosives into crowded streets, and ambushed or used land mines against vehicles plying the roads. Attacks and punitive attacks occurred; single gunfire shots led to widespread armed clashes.

By the end of May 1948, over 2,000 Palestinian civilians (Arabs and Jews) had been killed and thousands more had been wounded. The British still held legal authority over Palestine, but did little to stop the violence, as they were in the process of withdrawing their forces and disengaging from further involvement in the region’s internal affairs. The British did interfere in a few instances and suffered casualties as well.

A large Jewish paramilitary, as well as a number of smaller Jewish militias, already existed and operated clandestinely during the period of the British mandate. As the violence escalated, Jewish leaders integrated these armed groups into a single Jewish

Army.

Fighting on the side of the Palestinian Arabs were two rival armed groups: a smaller militia composed of Palestinian Arab fighters, and a larger paramilitary organized by the neighboring Arab countries. Egypt,

Syria, and Jordan did not want to send their armies to Palestine at this time since this would be an act of war against powerful Britain.

During the course of the war, the Jews experienced major logistical problems with the distant Jewish settlements that were separated from the main Jewish strongholds along the coast. These Jewish exclaves included Jerusalem, where one-sixth of all Palestinian Jews lived, as well as the many small villages and settlements in the north (Galilee) and in the south (Negev).

Jewish leaders sent militia units to these areas to augment existing local defense forces that consisted solely of local civilians. These isolated settlements were instructed to hold their ground at all costs. Supplying these Jewish exclaves was particularly dangerous, as delivery convoys were ambushed and had to traverse many Arab settlements along the

way. Food rationing, therefore, was imposed in many distant Jewish settlements, a policy that persisted until the war’s end.

The Jews gained a clear advantage in the fighting after they had organized a unified army. Their military leaders imposed mandatory conscription of men and single women, first only for the younger adult age groups, and later, for all men under age 40 and single women up to age 35. By April 1948, the Jewish Army had numbered 21,000 soldiers, up significantly from the few thousands at the start of the war.

The Jews also increased their weapons stockpiles from generous contributions made by wealthy donors in Europe and the United States. As the UN had imposed an arms embargo on Palestine, the Jews smuggled in their weapons, which were purchased mainly from dealers in Czechoslovakia. These weapons began to arrive in Palestine early in the

fighting, greatly enhancing the Jews’ war effort. The Jews also procured some weapons from clandestine small-arms manufacturers in Palestine; however, the output from local manufacturers was insufficient to fill the demands of the Jews’ growing army as well as the widening conflict.

Starting in April 1948, the Jewish Army launched a number of offensives aimed at securing Jewish territories as well as protecting Jewish civilians in Arab-held areas. These Jewish operations were carried out in anticipation of the Arab armies intervening in Palestine once the British Mandate ended on May 15, 1948.

On April 2, 1948, Jewish forces advanced toward Jerusalem in order to lift the siege on the city and allow the entry of supply vehicles. The Jews cleared the roads of Arab fighters and took control of the Arab villages nearby. The operation was only partially successful, however, as Jewish delivery convoys continued to be ambushed along the roads. Furthermore, Jewish authorities were condemned by the international community after a Jewish attack on the Arab village of Deir Yassin resulted in the deaths of over one hundred Arab civilians.

On April 8, Jewish forces succeeded in lifting the siege on Mishmar Haemek, a Jewish kibbutz in the Jezreel Valley. The Jews then launched a counter-attack that captured nearby Arab settlements. Further offensives allowed the Jews to seize control of northeastern Palestine. Also falling to Jewish forces were Tiberias in mid-April, Haifa and Jaffa later in the month, and Beisan and Safed in May. In southern Palestine, the Jews captured key areas in the Negev. The Jewish offensives greatly reduced the Palestinian Arabs’ capacity to continue the war.

In the wake of the Jewish victories, hundreds of thousands of Arab civilians fled from their homes, leaving scores of empty villages that were looted and destroyed by Jewish forces. Earlier in 1948, tens of thousands of middle-class and upper-class Arabs

had left Palestine for safety in neighboring Arab countries. Jewish authorities formally annexed captured Arab lands, merging them with Jewish territories already under their control.

On May 14, 1948, one day before the end of the British Mandate in Palestine, the Jews declared independence as the State of Israel. The following day, British rule in Palestine ended. Within a few hours, the armies of the Arab countries, specifically those from Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, invaded the new country of Israel, triggering the second phase of the conflict – the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (next article).

March 31, 2020

April 1, 1958 – Ifni War: The Treay of Angra de Cintra is signed, where Spain cedes Cape Juby and Tarfaya Strip to Morocco

Toward the end of the Ifni War, Mohammed V, the Moroccan king, who officially had remained neutral during the fighting, now appeared to take the side of the Europeans. The governments of Spain and Morocco opened negotiations to resolve the conflict. On April 1, 1958, the two sides signed the Treaty of Angra de Cintra, where Spain ceded Cape Juby and Tarfaya Strip to Morocco. The war officially ended on June 30, 1958 when the danger to the Spanish-held city of Sidi Ifni passed. Much of the Ifni region was in enemy possession, which subsequently was annexed by Morocco.

Spain maintained only an uncertain hold on Sidi Ifni, primarily because of foreign pressures. In December 1960, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 1514 that called for the end of colonial rule and granting of independences to colonized peoples around the world. By the end of the 1960s, many colonial powers had relinquished their territorial possessions, leading to the emergence of many new independent states. Faced with diplomatic pressures, on June 30, 1969, Spain ceded Sidi Ifni to Morocco. Within a few years, the focus of Spain’s decolonization of North Africa shifted to Spanish Sahara; Spain’s subsequent relinquishing of this region in November 1975 soon led to another war (this time not involving Spain, the Western Sahara War, next article).

Spanish possessions in northwest Africa with adjacent countries.

(Taken from Ifni War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

In 1956, Morocco gained full independence after France and Spain ended their 44-year protectorate and returned political and territorial control to Mohammed V, the Moroccan Sultan. A period of rising tensions and violence had preceded Morocco’s independence which nearly broke out into open hostilities. While France fully ended its protectorate, Spain only did so with its northern zone, retaining control of the southern zone (consisting of Cape Juby

and the interior area called the Tarfaya Strip). At Morocco’s independence, apart from Morocco’s southern zone, Spain held a number of other territories in North Africa that the Spanish government viewed as integral parts of Spain (i.e. they were not colonies or protectorates); these included Ceuta and Melilla which Spain had controlled since the 1500s; Plazas de soberanía (English: Places of sovereignty), a motley of tiny islands and small areas bordering the Moroccan

Mediterranean coastline; and Spanish Sahara, a vast territory half the size of mainland Spain that the Spanish government had gained in 1884 as a result of

the Berlin Conference during the period known as the “Scramble for Africa”, where European powers wrangled for their “share” of Africa.

Spain declared having historical ties, by way of the Spanish Empire, to the Ifni region (traced incorrectly to Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña, a 15th century Spanish settlement which was actually located further south of Ifni), Villa Cisneros, founded in 1502 and located in Spanish Sahara, and the Plazas de soberanía. In 1946, Spain merged the regions of Ifni, Cape Juby and Tarfaya Strip (southern zone of the Spanish protectorate), and Spanish Sahara into a single administrative unit called Spanish West Africa (Figure 13).

The Ifni region, which had at its capital the coastal city of Sidi Ifni, would become the focal point as well as lend its name to the coming war. After its defeat in the Spanish-Moroccan War in April 1860, Morocco ceded Ifni to Spain as a result of the Treaty of Tangiers.

Shortly after Morocco gained its independence, an ultra-nationalist movement, the Istiqlal Party led by Allal Al Fassi, advocated “Greater Morocco”, a political ideology that desired to integrate all territories that had historical ties to the Moroccan Sultanate with the modern Moroccan state. As envisioned, Greater Morocco would consist of, apart from present-day Morocco itself, western Algeria, Mauritania, and northwest Mali – and all Spanish possessions in North Africa.

Officially, the Moroccan government did not subscribe to or espouse “Greater Morocco”, but did not suppress and even tacitly supported irredentist advocates of this ideology. As a result, the Moroccan Army did not actively participate in the coming war; instead, the Moroccan Army of Liberation (MAL), which was an assortment of several Moroccan militias that had organized and risen up against the French protectorate, carried out the war against the Spanish (and French).

Shortly after Morocco gained its independence, civil unrest broke out in Ifni, which included anti-Spanish protest demonstrations and violence targeting police and security forces. Infiltrators

belonging to MAL later began supporting these activities. The unrest prompted the central government in mainland Spain, led by General Francisco Franco, to send Spanish troops, including units of the Spanish Legion, to Spanish West Africa, whose security units until then consisted mostly of personnel recruited from the local population.

Meanwhile, MAL militias, comprising some 4,000–5,000 Moukhahidine (“freedom fighters”) and led by Ben Hamou, a Moroccan former mercenary officer of the French Foreign Legion, had deployed near southern Moroccan and Spanish Sahara, and soon were joined by Sahrawi Berber and Arab fighters; at their peak, some 30,000 revolutionaries would take part in the conflict.

War

Fighting took place along two sectors: in the Ifni region in and around Sidi Ifni, and in Spanish Sahara. In the Ifni region, on October 21, 1957, some 1,500 MAL fighters (out of the 2,000 total deployed in this area), seized the villages of Goulimine and Bou Izarguen, just outside Sidi Ifni. Then on November 23, the revolutionaries cut

the communication lines, isolating Sidi Ifni from Spanish Sahara, and then launched their attack on the capital. The Spanish defenders in Sidi Ifni who held

several outposts outside the city were subjected to strong attacks and became isolated. At Tiluin, the sixty-man Spanish garrison came under siege, necessitating a dispatch of relief forces, one involving a parachute drop of 75 commandos carried out under intense fire. Together with a Spanish overland force that set out from Sidi Ifni, the Tiluin defenders and other civilians were rescued and transported to the capital.

March 30, 2020

March 31, 1968 – Vietnam War: U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson announces in a television address that he will not seek re-election as president

On March 31, 1968, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered the speech, “Steps to Limit the War in Vietnam”, in a television address to the nation. At the end of his speech, he announced, “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.” The address came shortly after the end of the Tet Offensive by North Vietnam and the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War.

The Tet Offensive fatally damaged President Johnson’s political career. Opposition within the

president’s own Democratic Party came at a crucial time, as the presidential election was scheduled later that year, in November 1968. Following a lackluster performance in the New Hampshire primary, President Johnson, in a nationwide broadcast, announced that he would not seek re-election as president. In the same broadcast, he suspended U.S.

bombing of North Vietnam in all areas north of the 19th parallel as an incentive to North Vietnam to start peace talks. The North Vietnamese government responded positively, and in May 1968, peace talks opened in Paris. Because the talks made little progress, on November 1, 1968, on President Johnson’s orders, aerial bombing of all North Vietnam was stopped (ending the 3½-year-long bombing campaign of Operation Rolling Thunder).

North Vietnam and South Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

In May and August 1968, the Viet Cong launched smaller “Mini-Tet” attacks as part of its ongoing “General Offensive, General Uprising” campaign. South Vietnamese and American forces, now being more vigilant, parried these attacks. Also in the immediate aftermath of the first Tet Offensive, the Viet Cong/NLF initially gained control of the rural areas which South Vietnamese forces had evacuated to defend the cities and towns. But in the post-Tet period, American and South Vietnamese large-scale search and destroy operations regained control of the countryside.

Ultimately, the Tet Offensive was a military disaster for the Viet Cong/NLF, as its military units were expelled from South Vietnam and forced into hiding in the Cambodian border regions. As a result, the Viet Cong experienced desertions, low morale, and difficulty to recruit new fighters. The Viet Cong soon ceased to be a native southern insurgency, as its ranks increasingly became filled by North Vietnamese cadres. In the end, the Viet Cong came under full control of North Vietnam.

For the United States, the Tet Offensive was a decisive military victory, but one that soon turned into a moral defeat for the American people, and a political disaster for President Johnson. During the early years of the war, President Johnson had issued only carefully measured amounts of information to the American public regarding the true military situation in Vietnam. He continued to declare that U.S. war strategy in Vietnam remained the same, despite the fact that American military involvement in the war was deepening and more and more troops were being sent to Vietnam. Soon, the American mass media detected a “credibility gap” between the U.S. government official pronouncements and the reports coming from Vietnam. In 1966, the first signs of American public opposition became evident, which by 1967, grew into a more vocal and radical protest movement.

Key areas during the Vietnam War.

Initially, President Johnson’s increased involvement in Vietnam enjoyed overwhelming political support, as evidenced by the near unanimous passage of the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as well as the high popular support. Opinion polls at the time showed that 80% of Americans supported the

war. But by 1967, surveys were showing growing opposition to the war. To counter falling public support, and media reports that the war had reached a stalemate, in the fall of 1967, the Johnson administration embarked on a high-profile propaganda campaign stating that the war was being won. Government officials, including Vice-President Hubert Humphrey and the American ambassador to South Vietnam, issued glowing statements in support of the war. High-ranking military officers also released data showing that the enemy was suffering from high numbers of its soldiers killed, weapons lost, and bases and camps captured. General Westmoreland also announced that the U.S. military

had “reached an important point when the end begins to come into view”, implying that American victory was imminent.

However, President Johnson’s attempts to win back public support through propaganda backfired, as the Tet Offensive showed that not only was the Viet Cong far from being defeated, it had the strength to launch a full-scale offensive across South Vietnam. As a result, support for the anti-war movement in the United States increased dramatically. Hundreds of

thousands of people participated in protest marches and rallies. These demonstrations sometimes deteriorated into violent confrontations with security forces. Anti-war sentiment particularly was strong among college students, and universities and colleges became centers of unrest. Active involvement came from many sectors, including women’s movements, social rights groups, African-Americans, and even

Vietnam War veterans.

Tet also fatally damaged President Johnson’s political career. Opposition within the president’s own Democratic Party came at a crucial time, as the presidential election was scheduled later that year, in November 1968. Following a lackluster performance in the New Hampshire primary, President Johnson, in a nationwide broadcast, announced that he would not seek re-election as president. In the same broadcast, he suspended U.S. bombing of North Vietnam in all areas north of the 19th parallel as an incentive to North Vietnam to start peace talks. The North Vietnamese government responded positively, and in May 1968, peace talks opened in Paris. Because the talks made little progress, on November 1, 1968, on President Johnson’s orders, aerial bombing of all North Vietnam was stopped (ending the 3½-year-long bombing campaign of Operation

Rolling Thunder).

Also in 1968, because of domestic pressures, the Johnson administration implemented a major shift in American involvement in the war: henceforth, the U.S. military would gradually disengage from the Vietnam War, and after a period of being built up, the South Vietnamese military would take over the fighting (the process known as the “Vietnamization” of the war). The South Vietnamese military buildup was meant to balance out the phased reduction of U.S. ground forces. U.S. forces in Vietnam, which peaked in 1968 at 530,000 troops, would see a steady reduction in succeeding years: 1969 – 475,000; 1970 – 335,000; 1971-156,000; 1972 – 24,000; and 1973 – 50. More than these numbers

alone, the pull-out of American troops would have a decisive impact on the outcome of the war.

In June 1968, General Creighton Abrams, who succeeded as over-all commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam (MACV), gradually shifted U.S. combat strategy away from search and destroy missions to “clear and hold” (i.e. to clear the insurgents from an area, which would then be held) operations, and

implemented a moderately successful “hearts and minds” campaign (under a newly formed agency, the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support, CORDS) to gain the sympathy of the civilian population for the South Vietnamese government.

In 1969, newly elected U.S. president, Richard Nixon, who took office in January of that year, continued with the previous government’s policy of American disengagement and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, while simultaneously expanding Vietnamization, with U.S. military advice and material support. He also was determined to

achieve his election campaign promise of securing a peace settlement with North Vietnam under the Paris

peace talks, ironically through the use of force, if North Vietnam refused to negotiate.

In February 1969, the Viet Cong again launched a large-scale Tet-like coordinated offensive across South Vietnam, attacking villages, towns, and cities, and American bases. Two weeks later, the Viet Cong launched another offensive. Because of these attacks, in March 1968, on President Nixon’s orders, U.S. planes, including B-52 bombers, attacked Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia

(along the Ho Chi Minh Trail). This bombing campaign, codenamed Operation Menu, lasted 14 months (until May 1970), and segued into Operation Freedom Deal (May 1970-August 1973), with the latter targeting a wider insurgent-held territory in eastern Cambodia.

March 29, 2020

March 30, 1945 –World War II: Soviet forces liberate Austria

The Germans hastened to construct defense lines in Austria, which officially was an integral part of Germany since the Anschluss of 1938. In late March to early April 1945, Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed the border from Hungary into Austria, meeting only light opposition in its advance toward Vienna. Only undermanned German forces defended the Austrian capital, which fell on April 13, 1945. Although some fierce fighting occurred, Vienna was spared the widespread destruction suffered by Budapest through the efforts of the anti-Nazi Austrian resistance movement, which assisted the Red Army’s entry into the city. A provisional government for Austria was set up comprising a

coalition of conservatives, democrats, socialists, and communists, which gained the approval of Stalin, who earlier had planned to install a pro-Soviet government regime from exiled Austrian communists. The Red Army continued advancing across other parts of Austria, with the Germans still holding large sections of regions in the west and south. By early May 1945, French, British, and American troops had crossed into Austria from the west, which together with the Soviets, would lead to the four-power Allied occupation (as in post-war Germany) of Austria after the war.

The series of massive Soviet Counter-Offensives recaptured lost Soviet territory and then swept through Eastern and Central Europe into Germany.

(Taken from Soviet Counter-attack and Defeat of Germany – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

The Balkans and

Eastern and Central Europe

With its advance into western Ukraine in April 1944,

the Red Army, specifically the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts, including the 1st and 4th Ukrainian Fronts, was poised to advance into Eastern Europe and the

Balkans to knock out Germany’s Axis allies from the war. In May 1944, a Red Army offensive into Romania was stopped by a German-Romanian combined force, but a subsequent operation in August broke through, and the Soviets captured Targu Frumus and Iasi (Jassy) on August 21 and Chisinau on August 24. The Axis defeat was thorough: German 6th Army, which had been reconstituted after its destruction in Stalingrad, was

again encircled and destroyed, German 8th Army, severely mauled, withdrew to Hungary, and the Romanian Army, severely lacking modern weapons, suffered heavy casualties. On August 23, Michael I,

King of Romania, deposed the pro-Nazi government of Prime Minister Ion Antonescu and announced his acceptance of the armistice offered by Britain, the

United States, and the Soviet Union. Romania then switched sides to the Allies and declared war on Germany. The Romanian government thereafter joined the war against Germany, and allowed Soviet forces to pass through its territory to continue into Bulgaria in the south.

The rapid collapse of Axis forces in Romania led to political turmoil in Bulgaria. On August 26, 1944, the Bulgarian government declared its neutrality in the war. Bulgarians were ethnic Slavs like the Russians, and Bulgaria did not send troops to attack the Soviet Union and in fact continued to maintain diplomatic ties with Moscow during the war. However, its government was pro-German and the country was an Axis partner. On September 2, a new Bulgarian government was formed comprising the

political opposition, which did not stop the Soviet Union from declaring war on Bulgaria three days later. On September 8, Soviet forces entered Bulgaria, meeting no resistance as the Bulgarian government stood down its army. The next day, Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, was captured, and the Soviets lent their support behind the new Bulgarian government comprising communist-led resistance fighters of the Fatherland Front. Bulgaria then declared war on Germany, sending its forces in support of the Red Army’s continued advance to the west.

The Red Army now set its sights on Serbia, the

main administrative region of pre-World War II Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia itself had been dismembered by the occupying Axis powers. For Germany, the loss

of Serbia would cut off its forces’ main escape route from Greece. As a result, the German High Command

allocated more troops to Serbia and also ordered the evacuation of German forces from other Balkan regions.

Occupied Europe’s most effective resistance struggle was located in Yugoslavia. By 1944, the communist Yugoslav Partisan movement, led by Josip Broz Tito, controlled the mountain regions of Bosnia, Montenegro, and western Serbia. In late September 1944, the Soviet 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts, thrusting from Bulgaria and Romania, together with

the Bulgarian Army attacking from western Bulgaria,

launched their offensive into Serbia. The attack was aided by Yugoslav partisans that launched coordinated offensives against the Axis as well as conducting sabotage actions on German communications and logistical lines – the combined

forces captured Serbia, most importantly the capital Belgrade, which fell on October 20, 1944. German

forces in the Balkans escaped via the more difficult routes through Bosnia and Croatia in October 1944. For the remainder of the war, Yugoslav partisans liberated the rest of Yugoslavia; the culmination of their long offensive was their defeat of the pro-Nazi

Ustase-led fascist government in Croatia in April-May 1945, and then their advance to neighboring Slovenia.

The succession of Red Army victories in Eastern Europe brought great alarm to the pro-Nazi government in Hungary, which was Germany’s last European Axis partner. Then when in late September 1944, the Soviets crossed the borders from Romania and Serbia into Hungary, Miklos Horthy, the Hungarian regent and head of state, announced in mid-October that his government had signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. Hitler promptly forced Horthy, under threat, to revoke the armistice, and German troops quickly occupied the country.

The Soviet campaign in Hungary, which lasted six months, proved extremely brutal and difficult both for the Red Army and German-Hungarian forces, with fierce fighting taking place in western Hungary as the

numerical weight of the Soviets forced back the Axis. In October 1944, a major tank battle was fought at Debrecen, where the panzers of German Army Group Fretter-Pico (named after General Maximilian Fretter-Pico) beat back three Soviet tank corps of 2nd Ukrainian Front. But in late October, a powerful

Soviet offensive thrust all the way to the outskirts of Budapest, the Hungarian capital, by November 7, 1944.

Two Soviet pincer arms then advanced west in a flanking maneuver, encircling the city on December 23, 1944, and starting a 50-day siege. Fierce urban warfare then broke out at Pest, the flat eastern section of the city, and then later across the Danube River at Buda, the western hilly section, where German-Hungarian forces soon retreated. In January 1945, three attempts by German armored units to relieve the trapped garrison failed, and on February 13, 1945, Budapest fell to the Red Army. The Soviets then continued their advance across Hungary. In early March 1945, Hitler launched Operation Spring Awakening, aimed at protecting the Lake Balaton oil fields in southwestern Hungary, which was one of Germany’s last remaining sources of crude oil. Through intelligence gathering, the Soviets became aware of the plan, and foiled the offensive, and then counter-attacked, forcing the remaining German forces in Hungary to withdraw across the Austrian border.

The Germans then hastened to construct defense lines in Austria, which officially was an integral part

of Germany since the Anschluss of 1938. In early

April 1945, Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed the border from Hungary into Austria, meeting only light opposition in its advance toward Vienna. Only undermanned German forces defended the Austrian capital, which fell on April 13, 1945. Although some fierce fighting occurred, Vienna was spared the widespread destruction suffered by Budapest

through the efforts of the anti-Nazi Austrian resistance movement, which assisted the Red Army’s entry into the city. A provisional government for Austria was set up comprising a coalition of conservatives, democrats, socialists, and communists, which gained the approval of Stalin, who earlier had planned to install a pro-Soviet government regime from exiled Austrian communists. The Red Army continued advancing across other parts of Austria,

with the Germans still holding large sections of regions in the west and south. By early May 1945, French, British, and American troops had crossed into Austria from the west, which together with the

Soviets, would lead to the four-power Allied occupation (as in post-war Germany) of Austria after the war.

German-occupied Poland

Operation Bagration’s conquest of Belarus in the summer of 1944 brought the Red Army to the Vistula River and to within striking distance of Warsaw. On August 1, 1944, the main Polish resistance organization, called the Home Army, in response to Soviet encouragement to start armed action, launched an uprising against the German occupation forces in Warsaw. What ensued was a 63-day battle, which was the center of the much larger series of armed actions in other Polish cities under Operation Tempest, where the Germans crushed the uprising by October 1944 in fierce house-to-house fighting in the Polish capital. Material support for the Polish fighters was in the form of a few supply drops by British and American planes, while Stalin stood down the Red Army that was positioned in the nearby Vistula

bridgeheads. The city of Warsaw, already heavily

damaged from the previous years’ fighting, was systematically razed to the ground by the Germans in reprisal and in house-clearing operations. By the end of the war, the Polish capital was 85% destroyed and became one of the most heavily devastated cities of World War II.

In early January 1945, the Red Army in the Vistula was ready to launch the conquest of German-occupied Poland. Two Soviet Army Groups (the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts) were assembled, the combined strength comprising 2.2

million troops, 7,000 tanks, 13,800 artillery pieces, 14,000 mortars, 4,900 anti-tank guns, and 2,200 Katyusha multiple-rocket launchers, and 8,500 planes, to confront German Army Group A, which was greatly outnumbered with 450,000 troops, 4,100 artillery pieces, and 1,100 tanks. German intelligence had detected the Soviet buildup, but Hitler dismissed this as “the greatest imposture since Genghis Khan”. Hitler also rejected the requests by his generals to reinforce Poland by abandoning the Courland Pocket. In the lead-up to the fighting, some German military units withdrew from indefensible areas. This German withdrawal triggered mass flight among civilians, and millions of ethnic Germans fled west to reach safety in central and western Germany. German officials also closed down the concentration camps in Poland,

and forced the prisoners there into death marches to Germany in the winter cold where thousands perished.

On January 12, 1945, the Red Army finally launched its gigantic operation, called the Vistula-Oder Offensive, which was nothing short of a juggernaut. Large areas fell quickly, including Warsaw on January 19 and Lodz on January 21. In many areas, German units were encircled and destroyed, as Hitler forbade any retreat and ordered that the Wehrmacht must fight to the death in these “fortresses”. Nevertheless, German forces at Krakow

withdrew just in time to avoid being surrounded and destroyed. Within two weeks, the Soviets had advanced 200 miles to the Oder River at the German border, placing them to within only 43 miles from Berlin. The Soviet 1st Belorussian Front, comprising

the northern thrust, also reached the Vistula Delta, cutting of East Prussia and the defending German

Army Group Center there, from Germany proper.

The Soviet 2nd Belorussian Front, whose diversion during the East Prussian campaign delayed 1st Belorussian Front’s advance to Berlin, now continued to Pomerania, taking Danzig on March 28, 1945 and reaching Stettin on April 26.

Meanwhile to the south, Soviet 1st Ukrainian Front thrust across Silesia in two campaigns in February and March 1945, clearing the region of German forces, thereby securing the southern flank of 1st Belorussian Front. A broad front was formed stretching from Pomerania to Silesia along the Oder and Neisse rivers in preparation for the offensive on Berlin.

March 28, 2020

March 29, 1973 – Vietnam War: The last U.S. combat troops leave South Vietnam; only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisors remain

By March 29, 1973, nearly all American and other allied troops had departed, and only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisors remained. A peacekeeping force, called the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnam to monitor and enforce the Accords’ provisions. But as large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS became powerless and failed to achieve its objectives.

North Vietnam and South Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

In February-March 1971, about 17,000 troops of the South Vietnamese Army, (some of whom were transported by U.S. helicopters in the largest air assault operation of the war), and supported by U.S. air and artillery firepower, launched Operation Lam Son 719 into southeastern Laos. At their furthest extent, the South Vietnamese seized and briefly held Tchepone village, a strategic logistical hub of the Ho Chi Minh Trail located 25 miles west of the South Vietnamese border. The main South Vietnamese column was stopped by heavy enemy resistance and poor road conditions at A Luoi, some 15 miles from the border. North Vietnamese forces, initially distracted by U.S. diversionary attacks elsewhere, soon assembled 50,000 troops against the South

Vietnamese, and counterattacked. North Vietnamese artillery particularly was devastating, knocking out several South Vietnamese firebases, while intense anti-aircraft fire disrupted U.S. air transport operations. By early March 1971, the attack was called off, and with the North Vietnamese intensifying their artillery bombardment, the South Vietnamese withdrawal turned into a chaotic retreat and a desperate struggle for survival. The operation was a debacle, with the South Vietnamese losing up to 8,000 soldiers killed, 60% of their tanks, 50% of their armored carriers, and dozens of artillery pieces; North Vietnamese casualties were 2,000 killed. American planes were sent to destroy abandoned South Vietnamese armor, transports, and equipment to prevent their capture by the enemy. U.S. air losses

were substantial: 84 planes destroyed and 430 damaged and 168 helicopters destroyed and 618 damaged.

Buoyed by this success, in March 1972, North Vietnam launched the Nguyen Hue Offensive (called the Easter Offensive in the West), its first full-scale offensive into South Vietnam, using 300,000 troops and 300 tanks and armored vehicles. By this time, South Vietnamese forces carried practically all of the fighting, as fewer than 10,000 U.S. troops remained in South Vietnam, and who were soon scheduled to leave. North Vietnamese forces advanced along three fronts. In the northern front, the North Vietnamese attacked through the DMZ, and captured the northern provinces, and threatened Hue and Da Nang. In late June 1972, a South Vietnamese

counterattack, supported by U.S. air firepower, including B-52 bombers, recaptured most of the occupied territory, including Quang Tri, near the northern border. In the Central Highlands front, the North Vietnamese objective to advance right through to coastal Qui Nhon and split South Vietnam in two, failed to break through to Kontum and was pushed back. In the southern front, North Vietnamese

forces that advanced from the Cambodian border took Tay Ninh and Loc Ninh, but were repulsed at An Loc because of strong South Vietnamese resistance and massive U.S. air firepower.

To further break up the North Vietnamese offensive, in April 1972, U.S. planes including B-52 bombers under Operation Freedom Train, launched bombing attacks mostly between the 17th and 19th parallels in North Vietnam, targeting military installations, air defense systems, power plants

and industrial sites, supply depots, fuel storage facilities, and roads, bridges, and railroad tracks. In May 1972, the bombing attack was stepped up with Operation Linebacker, where American planes now attacked targets across North Vietnam. A few days earlier, U.S. planes air-dropped thousands of naval mines off the North Vietnamese coast, sealing off North Vietnam from sea traffic.

At the end of the Easter Offensive in October 1972, North Vietnamese losses included up to 130,000 soldiers killed, missing, or wounded and 700 tanks destroyed. However, North Vietnamese forces succeeded in capturing and holding about 50% of the territories of South Vietnam’s northern provinces of Quang Tri, Thua Thien, Quang Nam, and Quang Tin, as well as the western edges of II Corps and III Corps. But the immense destruction caused by U.S. bombing in North Vietnam forced the latter to agree to make concessions at the Paris peace talks.

At the height of North Vietnam’s Easter Offensive, the Cold War took a dramatic turn when in February 1972, President Nixon visited China and met with Chairman Mao Zedong. Then in May 1972, President Nixon also visited the Soviet Union and met with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders. A period of superpower détente followed. China and the Soviet Union, desiring to maintain their newly established friendly relations with the United States, aside from issuing diplomatic protests, were not overly provoked by the massive

U.S. bombing of North Vietnam. Even then, the two communist powers stood by their North Vietnamese ally and continued to send large amounts of military

support.

Since it began in May 1968, the peace talks in Paris had made little progress. Negotiations were held at the main conference hall. However, since

February 1970, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho had been holding secret talks separate from

the main negotiations. These secret talks achieved a breakthrough on October 17, 1972 (ten days after the U.S. bombings had forced North Vietnam to return to negotiations), when Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand” and that a mutually agreed draft of a peace agreement was to be signed on October 31, 1972.

However, South Vietnamese President Thieu, when presented with the peace proposal, refused to agree to it, and instead demanded 129 changes to the draft agreement, including that the DMZ be recognized as the international border of a fully sovereign, independent South Vietnam, and that North Vietnam withdraw its forces from occupied

territories in South Vietnam. On November 1972, Kissinger presented Tho with a revised draft incorporating South Vietnam’s demands as well as

changes proposed by President Nixon. This time, the North Vietnamese government was infuriated and believed it had been deceived by Kissinger. On

October 26, 1972, North Vietnam broadcast details of the document. In December 1972, talks resumed which went nowhere, and soon broke down on December 14, 1972.

Also on December 14, 1972, the U.S. government issued a 72-hour ultimatum to North Vietnam to return to negotiations. On the same day, U.S. planes

air-dropped naval mines off the North Vietnamese waters, again sealing off the coast to sea traffic. Then on President Nixon’s orders to use “maximum effort…maximum destruction”, on December 18-29, 1972, U.S. B-52 bombers and other aircraft under Operation Linebacker II, launched massive bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam, including Hanoi

and Haiphong, hitting airfields, air defense systems, naval bases, and other military facilities, industrial complexes and supply depots, and transport facilities. As many of the restrictions from previous air campaigns were lifted, the round-the-clock bombing attacks destroyed North Vietnam’s war-related logistical and support capabilities. Several B-52s were shot down in the first days of the operation, but changes to attack methods and the use of electronic and mechanical countermeasures greatly reduced air losses. By the end of the bombing campaign, few targets of military value remained in North Vietnam, enemy anti-aircraft guns had been silenced, and North Vietnam was forced to return to negotiations. On January 15, 1973, President Nixon ended the bombing operations.

One week later, on January 23, negotiations resumed, leading four days later, on January 27, 1973, to the signing by representatives from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG), and the United States of the Paris Peace Accords (officially titled: “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked the end of the war. The Accords stipulated a ceasefire; the release and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of all American and other non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for South Vietnam: a political settlement between the government and the PRG to determine the country’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peaceful reunification of North Vietnam and South Vietnam. As in the 1954 Geneva Accords (which ended the First Indochina War), the DMZ did not constitute a political/territorial border. Furthermore, the 200,000 North Vietnamese troops occupying territories in South Vietnam were allowed to remain in place.

To assuage South Vietnam’s concerns regarding the last two points, on March 15, 1973, President Nixon assured President Thieu of direct U.S. military air intervention in case North Vietnam violated the

Accords. Furthermore, just before the Accords came into effect, the United States delivered a large amount of military hardware and financial assistance to South Vietnam.

By March 29, 1973, nearly all American and other allied troops had departed, and only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisors remained. A peacekeeping force, called the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnam to monitor and enforce the Accords’ provisions. But as large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS became powerless and failed to achieve its objectives.

For the United States, the Paris Peace Accords meant the end of the war, a view that was not shared by the other belligerents, as fighting resumed, with the ICCS recording 18,000 ceasefire violations between January-July 1973. President Nixon had

also compelled President Thieu to agree to the Paris Peace Accords under threat that the United States would end all military and financial aid to South

Vietnam, and that the U.S. government would sign the Accords even without South Vietnam’s concurrence. Ostensibly, President Nixon could fulfill his promise of continuing to provide military support to South Vietnam, as he had been re-elected in a landslide victory in the recently concluded November 1972 presidential election. However, U.S. Congress, which was now dominated by anti-war legislators, did not bode well for South Vietnam. In June 1973, U.S. Congress passed legislation that prohibited U.S. combat activities in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, without prior legislative approval. Also that year, U.S. Congress cut military assistance to South Vietnam by 50%. Despite the clear shift in U.S. policy, South Vietnam continued to believe the U.S. government

would keep its commitment to provide military assistance.

Then in October 1973, a four-fold increase in world oil prices led to a global recession following the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposing an oil embargo in response to U.S. support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War. South Vietnam’s economy was already reeling because of the U.S. troop withdrawal (a vibrant local goods and services economy had existed in Saigon because of the presence of large numbers of American soldiers) and reduced U.S. assistance. South Vietnam experienced soaring inflation, high unemployment, and a refugee problem, with hundreds of thousands

of people fleeing to the cities to escape the fighting in the countryside.

The economic downturn also destabilized the South Vietnamese forces, for although they possessed vast quantities of military hardware (for

example, having three times more artillery pieces and two times more tanks and armor than North Vietnam), budget cuts, lack of spare parts, and fuel shortages meant that much of this equipment could not be used. Later, even the number of bullets allotted to soldiers was rationed. Compounding

matters were the endemic corruption, favoritism, ineptitude, and lethargy prevalent in the South Vietnamese government and military.

In the post-Accords period, South Vietnam was determined to regain control of lost territory, and in a number of offensives in 1973-1974, it succeeded in seizing some communist-held areas, but paid a high price in personnel and weaponry. At the same

time, North Vietnam was intent on achieving a complete military victory. But since the North Vietnamese forces had suffered extensive losses in the previous years, the Hanoi government concentrated on first rebuilding its forces for a planned full-scale offensive of South Vietnam,

planned for 1976.

In March 1974, North Vietnam launched a series of “strategic raids” from the captured territories that it held in South Vietnam. By November 1974, North Vietnam’s control had extended eastward from the north nearly to the south of the country. As well, North Vietnamese forces now threatened a number of coastal centers, including Da Nang, Quang Ngai, and Qui Nhon, as well as Saigon. Expanding its occupied areas in South Vietnam also allowed North Vietnam to shift its logistical system (the Ho Chi Minh Trail) from eastern Laos and Cambodia to inside South Vietnam itself. By October 1974, with major road improvements completed, the Trail system was a fully truckable highway from north to south, and greater numbers of North Vietnamese units, weapons, and supplies were being transported each month to South Vietnam.

March 27, 2020

March 28, 1951 – First Indochina War: French forces defeat the Viet Minh at the Battle of Mao Khe

In December 1950, French and allied forces came under the command of General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, a highly respected veteran officer of World War II, whose arrival greatly raised troop morale. To defend Hanoi, Haiphong, and the Red River Delta, he constructed an extensive network of fortifications (called the De Lattre Line, Figure 3) that covered 3,200 kilometers from the northern coast to the Chinese border and consisted of about 1,200 concrete fortifications, each armed with and supported by artillery, armored, and air units.

In 1951, the Viet Minh, believing that the French military was verging on defeat, launched several offensives on the De Lattre Line. The first attack occurred in January 1951 at Vinh Yen, where 20,000 Viet Minh troops advanced using human-wave

assaults. After initially gaining ground, the attack was repulsed after four days of fighting by heavy French

artillery bombardments and air strikes. Then in March 1951, Viet Minh forces attacked lightly defended Mao Khe town in preparation to advancing toward Haiphong. The Viet Minh succeeded in entering the town, where it engaged the small French garrison there in some intense street fighting. But the French soon counter-attacked, and repulsed the Viet Minh after four days of fighting. In May-June 1951, in fighting at Ninh Binh, Nam Dinh, Phu Ly, and Phat Diem, collectively known as the Battle of the Day River, French superior firepower beat back the numerically superior Viet Minh, the latter suffering 9,000 soldiers killed or wounded, and 1,000 captured.

The De Lattre Line, however, was not secure in all places, as Viet Minh infiltration teams entered through gaps between fortifications. Some 30,000 Viet Minh cadres, including communist agitators, soon established Viet Minh influence in 5,000 of the 7,000 villages in the Red River Delta area. In November 1951, General de Lattre went on the offensive, air-dropping commandos in Hoa Binh town, deep inside Viet Minh territory. The town was taken, but large numbers of Viet Minh forces laid siege to the French commandos, cutting off the approaches to Hoa Binh through the Black River and along Route Coloniale 6. In late February 1952, French forces were forced to evacuate the town.

Present-day Vietnam in Southeast Asia.

(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath

By the time of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, France knew that it could not win the war, and turned its attention on trying to work toward a political settlement and an honorable withdrawal from Indochina. By February 1954, opinion polls at home showed that only 8% of the French population supported the war. However, the Dien Bien Phu debacle dashed French hopes of negotiating under favorable withdrawal terms. On May 8, 1954, one day after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, representatives from the major powers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochina states: Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and State of Vietnam, met at Geneva (the Geneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina. The Conference also was envisioned to resolve the crisis in the Korean Peninsula in the aftermath of the Korean War (separate article), where deliberations ended on June 15, 1954 without any settlements made.

On the Indochina issue, on July 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by the parties. The ceasefire was agreed to by France and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17th parallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional military

demarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The French and their allies in the northern zone departed and moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh in the southern zone departed and moved to the northern zone (although some southern Viet Minh remained in the south on

instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 days where Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on either side of the line. About one million northerners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upper

classes consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communist politicians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone, this mass exodus was prompted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and State of Vietnam in a massive propaganda campaign, as well as the peoples’ fears of repression under a communist regime.

In August 1954, planes of the French Air Force and hundreds of ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy (the latter under Operation Passage to Freedom) carried out the movement of Vietnamese civilians from north to south. Some 100,000 southerners, mostly Viet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, moved to the northern

zone. A peacekeeping force, called the International Control Commission and comprising contingents from India, Canada, and Poland, was tasked with enforcing the ceasefire agreement. Separate ceasefire agreements also were signed for Laos and Cambodia.

Another agreement, titled the “Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring Peace in Indo-China, July 21, 1954”, called for Vietnamese general elections to be held in July 1956, and the reunification of Vietnam. France DRV, the Soviet Union, China, and Britain signed this

Declaration. Both the State of Vietnam and the United States did not sign, the former outright rejecting the Declaration, and the latter taking a hands-off stance, but promising not to oppose or jeopardize the Declaration.

By the time of the Geneva Conference, the Viet Minh controlled a majority of Vietnam’s territory and appeared ready to deal a final defeat on the demoralized French forces. The Viet Minh’s agreeing to apparently less favorable terms (relative to its commanding battlefield position) was brought about by the following factors: First, despite Dien Bien

Phu, French forces in Indochina were far from being defeated, and still held an overwhelming numerical and firepower advantage over the Viet Minh; Second, the Soviet Union and China cautioned the Viet Minh that a continuation of the war might prompt an escalation of American military involvement in support of the French; and Third, French Prime Minister Pierre Mendes-France had vowed to achieve

a ceasefire within thirty days or resign. The Soviet Union and China, fearing the collapse of the Mendes-France regime and its replacement by a right-wing government that would continue the war, pressed Ho to tone down Viet Minh insistence of a unified Vietnam under the DRV, and agree to a compromise.

The planned July 1956 reunification election failed to materialize because the parties could not agree on how it was to be implemented. The Viet Minh proposed forming “local commissions” to administer the elections, while the United States,

seconded by the State of Vietnam, wanted the elections to be held under United Nations (UN) oversight. The U.S. government’s greatest fear was a communist victory at the polls; U.S. President Eisenhower believed that “possibly 80%” of all Vietnamese would vote for Ho if elections were held. The State of Vietnam also opposed holding the reunification elections, stating that as it had not signed the Geneva Accords, it was not bound to participate in the reunification elections; it also declared that under the repressive conditions in the north under communist DRV, free elections could not be held there. As a result, reunification elections were not held, and Vietnam remained divided.

In the aftermath, both the DRV in the north (later commonly known as North Vietnam) and the State of Vietnam in the south (later as the Republic of Vietnam, more commonly known as South Vietnam) became de facto separate countries, both Cold War client states, with North Vietnam backed by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, and South Vietnam supported by the United States and other Western democracies.

In April 1956, France pulled out its last troops from Vietnam; some two years earlier (June 1954), it had granted full independence to the State of Vietnam. The year 1955 saw the political consolidation and firming of Cold War alliances for both North Vietnam and South Vietnam. In the north, Ho Chi Minh’s regime launched repressive land reform and rent reduction programs, where many tens of thousands of landowners and property managers were executed, or imprisoned in labor camps. With the Soviet Union and China sending more weapons and advisors, North Vietnam firmly fell within the communist sphere of influence.

In South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, whom Bao Dai appointed as Prime Minister in June 1954, also eliminated all political dissent starting in 1955, particularly the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen in Saigon, and the religious sects Hoa Hao and Cao Dai in the Mekong Delta, all of which maintained powerful armed groups. In April-May 1955, sections of central Saigon were destroyed in street battles between government forces and the Binh Xuyen

militia.

Then in October 1955, in a referendum held to determine the State of Vietnam’s political future, voters overwhelmingly supported establishing a republic as campaigned by Diem, and rejected the restoration of the monarchy as desired by Bao Dai.

Widespread irregularities marred the referendum, with an implausible 98% of voters favoring Diem’s proposal. On October 23, 1955, Diem proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam (later commonly known as South Vietnam), with himself as its first president. Its

predecessor, the State of Vietnam was dissolved, and Bao Dao fell from power.

In early 1956, Diem launched military offensives on the Viet Minh and its supporters in the South Vietnamese countryside, leading to thousands being executed or imprisoned. Early on, militarily weak South Vietnam was promised armed and financial support by the United States, which hoped to prop up the regime of Prime Minister (later President) Diem, a devout Catholic and staunch anti-communist, as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia.

In January 1955, the first shipments of American weapons arrived, followed shortly by U.S. military advisors, who were tasked to provide training to the South Vietnamese Army. The U.S. government also endeavored to shore up the public image of the somewhat unknown Diem as a viable alternative

to the immensely popular Ho Chi Minh. However, the Diem regime was tainted by corruption and nepotism, and Diem himself ruled with autocratic powers, and implemented policies that favored the wealthy landowning class and Catholics at the expense of the lower peasant classes and Buddhists (the latter comprised 70% of the population).

By 1957, because of southern discontent with Diem’s policies, a communist-influenced civilian uprising had grown in South Vietnam, with many acts of terrorism, including bombings and assassinations, taking place. Then in 1959, North Vietnam,

frustrated at the failure of the reunification elections from taking place, and in response to the growing insurgency in the south, announced that it was

resuming the armed struggle (now against South Vietnam and the United States) in order to liberate the south and reunify Vietnam. The stage was set for the cataclysmic Second Indochina War, more popularly known as the Vietnam War. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5: Twenty Wars in Asia.)

March 26, 2020

March 27, 1941 – World War II: Pro-Allied Yugoslav Air Force officers depose pro-German Prince Paul, prompting Hitler to invade Yugoslavia

Adolf Hitler exerted great effort to try and persuade the officially neutral but Allied-leaning government of Yugoslav Prime Minister Dragisha Cvetkovic to join the Axis. In a series of high-level meetings between the two countries which even included Hitler’s participation, the Germans offered sizable rewards to Yugoslavia for joining the Axis, including Greek territory that would include Salonica which would give Yugoslavia access to the Aegean Sea. Talks went nowhere until Hitler met with Prince Paul on March 4, 1941, which led two weeks later to the Yugoslav government agreeing to join the Axis. On March 25, 1941, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact, motivated by a secret clause in the agreement that contained three stipulations: the Axis promised to respect Yugoslavian sovereignty and territorial integrity, the Yugoslavian military would not be required to assist the Axis, and Yugoslavia would not be required to allow Axis forces to pass through its territory. But two days later, March 27, pro-Allied Yugoslav Army Force officers deposed the Yugoslav government and installed itself in a military regime, arrested Prince Paul, and named the 17-year old minor crown prince as King Peter II. The new military government assured Germany that Yugoslavia wanted to maintain friendly ties between the two countries, albeit that it would not ratify the Tripartite Pact. Anti-German mass demonstrations broke out in Belgrade and other Serbian cities.

As a result of the coup, a furious and humiliated Hitler believed that Yugoslavia had taken a stand favoring the Allies, despite the new Yugoslav government’s conciliatory position toward Germany. On March 27, 1941, just hours after the coup, Hitler convened the German military high command and stated his intention to “destroy Yugoslavia as a military power and sovereign state”. He ordered the formulation of an invasion plan for Yugoslavia, which was to be carried out together with the attack on Greece. Despite the time constraint (the attack on

Greece was set to be launched in ten days, April 6, 1941), the German military finalized a lightning attack for Yugoslavia, code-named Operation 25, to be under taken in coordination with the operation on Greece.

Hitler invited Bulgaria to participate in the attack on Yugoslavia, but the Bulgarian government declined, citing the need to defend its borders. As well, Hungary demurred, as it had just recently signed a non-aggression pact with Yugoslavia, but it agreed to allow the German invasion forces to mass in its southwestern border with Yugoslavia. Romania was not asked to join the invasion.

Mussolini, after conferring with Hitler, agreed to

participate, and the Italian forces were to undertake the following: temporarily cease operations at the Albanian front; protect the flank of the German forces invading from Austria to Slovenia; seize Yugoslav territories along the Adriatic coast; and link up with German forces for the invasion of Greece.

On April 3, 1941, Yugoslavia sent emissaries to Moscow to try and arrange a mutual defense treaty with the Soviet Union. Instead, on April 5, the Soviet government agreed only to a treaty of friendship and non-aggression with Yugoslavia, which did not promise Soviet protection in case of foreign aggression. As a result, Hitler was free to invade Yugoslavia without fear of Soviet intervention. On

April 6, 1941, Germany and Italy launched the invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece, discussed separately in the next two chapters.

The Balkan region and nearby Italy, Austria (annexed by Germany), and Hungary.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

The Balkan Campaign

In August 1940, Hitler gave secret instructions to his military high command to prepare a plan for the invasion of the Soviet Union, to be launched in the spring of 1941. In October 1940-January 1941, the Germans launched fierce air attacks on Britain, which

failed to force the latter to capitulate as Hitler had hoped. Hitler then suspended his planned invasion of

Britain and instead focused on other ways to bring it to its knees. He turned to the Mediterranean Sea, whose control by Germany and Italy would have the effect of cutting off Britain from its colonies in Africa and Asia via the Suez Canal. In this plan, German forces would capture Gibraltar through Spain, thus sealing off the western end of the Mediterranean Sea, while the Italian Army in Libya would capture British-controlled Egypt as well as the Suez Canal, sealing off the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea. German forces would join in the final stages of the Italian offensive.

As the German military formulated the invasion plan of the Soviet Union and the means to knock Britain out of the war, Hitler was determined that no complications arose that would interfere with these

objectives. Foremost, Hitler had no appetite for turmoil to break out in southeastern Europe, especially the highly volatile Balkan region, the “powder keg” that had sparked World War I. Politically and strategically, Hitler wanted stability in the Balkans to keep away the Soviet Union, with whom Germany had a tenuous non-aggression pact.

Conflict in the Balkans would most likely prompt intervention by Russia, which traditionally held a strong influence there.

Hitler had long stated that he had no territorial ambitions on the Balkans. Instead, Germany’s main interest there was purely economic, as the Balkan countries were Germany’s biggest partners, supplying the latter with food and mineral resources. But of the greatest importance to Hitler were the Ploiesti oil fields in Romania, which provided the German military and industry with vital petroleum products.

Germany and Italy mediated two territorial disputes involving Romania and its neighbors: on August 21, 1940, Romania was persuaded to cede Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria, and on August 30, 1940, it also relinquished one-third of Transylvania to Hungary. A few weeks earlier, in late June-early July

1940, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had used strong-arm tactics to force Romania to cede its northeastern regions of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, Hitler strove to convince Mussolini to stall the latter’s territorial ambitions in the Balkans.

Mussolini had long viewed that in the German-Italian partition of Europe, southeastern Europe and the Balkans fell inside the Italian sphere of control.

Italian forces had invaded Albania in April 1939 (separate article), and after the fall of France in June 1940, Mussolini exerted pressure on Greece and Yugoslavia, and threatened them with invasion. At that time, Hitler was able to convince Mussolini to suspend temporarily his Balkan ambitions and instead focus Italian efforts on defeating the British in North Africa.

But on October 7, 1940, at the request of Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu, German forces entered Romania to guard against a Soviet invasion; for Hitler, it was to protect the vital Ploiesti oil fields. Mussolini was outraged by this German action, as he believed that Romania fell inside his zone of control. Also for Mussolini, Hitler’s move into Romania was only the latest in a long list of stunts that had been made without previously consulting him, and one that had to be reciprocated, or as Mussolini put it, “to repay him [Hitler] with his own coin”. Hitler had invaded Poland, Denmark, Norway, France, and the Low Countries without informing Mussolini beforehand.

On October 28, 1940, Mussolini, without notifying Hitler, launched the invasion of Greece

(previous article), despite insufficient military preparation and against the counsel of his top generals. The operation was a disaster, as the motivated Greek Army threw back the Italians to Albania, and then launched its own offensive. Within three months, the Greeks occupied a quarter of Albanian territory. Greece had declared its neutrality at the start of World War II. But because of the Italian invasion, the Greek government turned to Britain for assistance. In early November 1940,

British forces had arrived, and occupied two strategically important Greek islands, Crete and Limnos.

The unexpected Italian attack on Greece and likelihood of British intervention in the Balkans shocked Hitler, seeing that his efforts to try and

maintain peace in the region had failed. His prized Ploesti oil fields and the whole southeastern Europe were now vulnerable. On November 4, 1940, Hitler decided to become involved in Greece in order to bail out his beleaguered ally Mussolini and to forestall the

British. On November 12, 1940, the German High Command issued Directive No. 18, which laid out the German plan to contain the British in the Mediterranean: German forces would invade northern Greece and Gibraltar in January 1941, and then assist the Italians in attacking Egypt in the fall of 1941. However, Spain’s pro-Axis dictator General Francisco Franco refused to allow German troops into Spain, forcing Germany to suspend its invasion of Gibraltar. On December 13, 1940, the German military issued Directive No. 20, which finalized the invasion of Greece under codename Operation Marita. In the final plan, German forces in Bulgaria would open a second front in northeastern Greece and capture the whole Greek northern coast, link up with the Italians in the northwest, and if necessary, push south toward Athens and seize the rest of Greece. Operation Marita was scheduled for March 1941; however, delays would cause the invasion to be launched one month later.

For the invasion of Greece, Hitler considered it necessary to bring into the Axis fold the governments of Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia, notwithstanding their stated neutrality at the start of the World War II. With their cooperation, German forces would cross their territories through Central and Eastern Europe, as well as control their military-important infrastructures, such as airfields and communications systems. Hungary, which had benefited territorially in the German seizure of Czechoslovakia and Axis arbitration of Transylvania, was drawn naturally to Germany. On November 20, 1940, the Hungarian government joined the Tripartite Pact . Three days later, Romania also joined the Pact, as Romanian leader Antonescu was motivated to do so by fear of a Soviet invasion. In succeeding months, large numbers of German forces and weapons, passing through Hungary, would assemble in Romania, mainly for the planned invasion of the Soviet Union (whose operational plan would be finalized in December 1940 under the top-secret Operation Barbarossa).

Bulgaria balked at joining the Pact and thus be openly associated with the Axis, and also was concerned that participating in the invasion of Greece would leave its eastern border vulnerable to an attack by Turkey, which was allied with Greece. The Bulgarians also were aware of a Soviet plan to capture Varna, Bulgaria’s Black sea port, which the Soviets would use to seize control of the Turkish Straits, which was a source of a long-standing dispute between the Soviet Union and Turkey.

However, Hitler exerted strong diplomatic pressure on Bulgaria and also promised to protect Bulgarian territorial integrity. Bulgaria acquiesced and agreed to allow German troops to enter Bulgarian territory. On February 28, 1941, German engineering

crews bridged the Danube River at the Romanian-Bulgarian border, and the first German units crossed into Bulgaria and continued to that country’s eastern border. The next day, March 1st, Bulgaria joined the Tripartite Pact, officially joining the Axis. On March 2, 1941, German forces involved in Operation Marita entered Bulgaria and proceeded south to the Bulgarian-Greek border.

To assure Turkey of German intentions, Hitler wrote to the Turkish government to explain that the German presence in Bulgaria was directed at Greece. To further allay the Turks, German troops were positioned far from the Turkish border. The Turkish government accepted the German clarification, and agreed to stand down its forces during the German attack on Greece.

Meanwhile, Greece was aware of German plans, and in the previous months, held talks with Britain and Yugoslavia to formulate a common strategy against the anticipated German attack. The dilemma for Greece was that by March 1941, the greater part of its military forces were still tied down against the Italians in southern Albania, leaving insufficient units to defend the rest of the country’s northern border. At the request of the Greek government, Britain and its dominions, Australia and New Zealand, sent 58,000 troops to Greece; this force arrived in March 1941 and deployed in Greece’s north central border.

March 25, 2020

March 26, 1939 – Spanish Civil War: Nationalist forces begin their offensive into central Spain

On March 26, 1939, Nationalist forces advanced into central Spain, meeting no resistance as the junta had ordered Republican soldiers to raise white flags and retreat from the frontlines. On March 28, the Nationalists entered Madrid, where large crowds welcomed them as liberators. The Nationalists then continued across eastern Spain to the Mediterranean coast.

(Taken from Spanish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

In December 1938, one month after the fighting in the Ebro ended, General Francisco Franco, leader of the Nationalist forces, was ready to advance into Catalonia, with Barcelona, the Republican government’s capital, as the ultimate objective. The Nationalists assembled a force of 300,000 soldiers, 300 tanks, 1,400 artillery pieces, and 500 planes. Meeting this were also about 300,000 Republican soldiers, but who were only poorly equipped with firearms, and supported by 40 tanks, 250 artillery pieces, and 100 planes. Across Catalonia, the Republicans’ morale among soldiers and civilians was at its lowest, and the great majority wanted an end to the war.

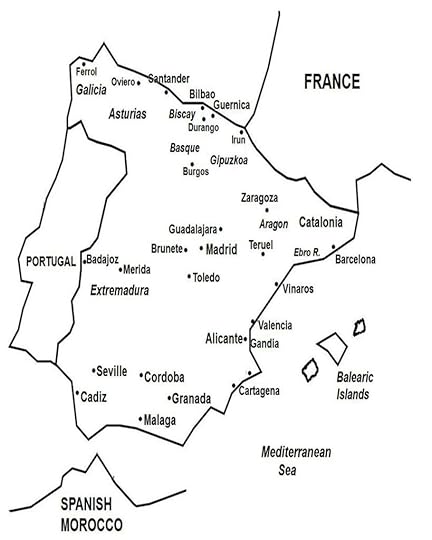

Key areas during the Spanish Civil War.

On January 23, 1939, the Nationalists attacked Catalonia from the west and south. After initially meeting strong resistance, the offensive broke through and advanced all across the countryside. To take the pressure from Catalonia, in early January 1939, the Republicans opened a front in Extremadura, attacking northeast of Cordoba and gaining some territory. Then, the Nationalists counter-attacked with supporting air firepower, and threw back the Republicans.

By the third week of January 1939, the Nationalists had reached the outskirts west and south of Barcelona. The Republican government, led by President Manuel Azaña and Prime Minister Negrin, evacuated from the capital and fled north to the Spanish-French border. Some 500,000 Republican soldiers and civilians joined the retreat, pursued by the Nationalist Army. Prime Minister Negrin

appealed to General Franco for peace talks, but was rejected, as the Nationalist leader wanted only unconditional surrender. On January 26, Barcelona fell to the Nationalists.

In early February 1939, the retreating Republican Army and civilians entered into France (the French government had reopened the border). The refugees were gathered by French authorities and then interned in camps. After the war, some 200,000 refugees returned to Spain, while 300,000 eventually immigrated to other countries in Europe and the Americas. On February 9, 1939, Nationalist forces

reached the Spanish-French border, which they closed down. By this time, Catalonia was fully under the Nationalists’ control. Three weeks later, France and Britain recognized General Franco’s government.

Prime Minister Negrin managed to fly back to Republican Spain to take over control of the remaining territories still held by the Republicans. By then, however, although the Republicans still held about 30% of Spain, the war essentially was over. Negrin established his headquarters at Alicante,