Daniel Orr's Blog, page 98

May 12, 2020

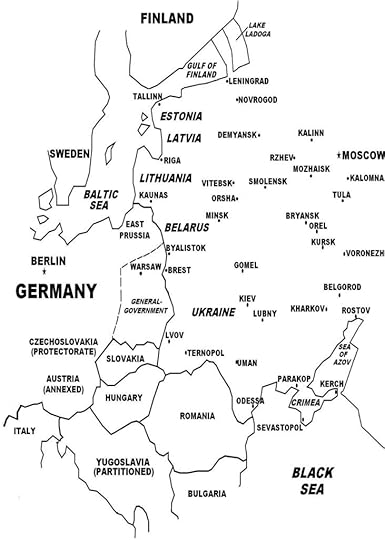

May 12, 1942 – World War II: German forces repulse a Soviet offensive at the Second Battle of Kharkov

Following the failure of Operation Barbarossa (Germany’s planned lightning conquest of the Soviet Union in 1941), Stalin was so encouraged by the Soviet counter-attack that saved Moscow that he ordered more operations be conducted. He intended these thrusts to form part of a general counter-offensive at specific points from north to south of the frontline.

Operation Barbarossa

These operations were unsuccessful and disastrous to the Red Army: at Demyansk (February-April 1942) and Kholm (January-May 1942), trapped

German forces, supplied by air for several weeks, repulsed Soviet attempts to eliminate the pockets; a Soviet counter-offensive (January-April 1942) to lift

the siege of Leningrad led instead to the attackers being encircled and destroyed; a Red Army operation aimed at recapturing Kharkov (in northeastern Ukraine; Second Battle of Kharkov, May 1942) instead led to six Soviet armies being trapped and 300,000 casualties, including the destruction of 1,200 tanks, 2,000 artillery pieces, and 500 aircraft, for the German loss of 20,000 troops and 50 planes; and the failure of the Red Army to recapture the Crimea (December 1941-May 1942).

May 11, 2020

May 11, 1944 – World War II: The Allies make a fourth major attempt to break through the Gustav Line

On May 11, 1944, the Allies launched Operation Diadem to

break through the Axis defences on the Gustav Line. The Gustav Line was the

major defence of three that was collectively called the Winter Line. The Winter

Line itself was one in a series of defences based on German strategy that

relied on the natural features centered on the Apennine

Mountains that forms a “spine” along

much of the length of Italy.

German strategy for the defense of Italy relied on the natural defensive features, particularly the Apennine Mountains which forms a “spine” along much of the length of Italy, as well as the numerous rivers; to the north, by the time of the Allied attack on the alpine region in northern Italy, German defenses verged on complete collapse.

German strategy for the defense of Italy relied on the natural defensive features, particularly the Apennine Mountains which forms a “spine” along much of the length of Italy, as well as the numerous rivers; to the north, by the time of the Allied attack on the alpine region in northern Italy, German defenses verged on complete collapse.Successive Allied attacks since January 1944 had failed to

breach the Gustav Line. But on May 19, 1944, a concentrated Allied offensive

combining U.S.

5th and British 8th Armies finally breached the Gustav Line, forcing German

10th Army to fall back.

Just days later, May 23, U.S. forces that had had also been

bottled up for months at Anzio broke out from the beaches and advanced

northwest toward Rome instead of attacking northeast to cut off German 10th

Army, as planned. As a result, the

Allies failed to encircle German 10th Army at the Gustav Line. German 10th Army escaped and, together with

German 14th Army from Anzio, soon established

new positions in northern Italy. The Allied planning had also placed Rome inside the American sector, and not the British;

instead, the latter were tasked to bypass Rome

and pursue the retreating Germans.

On May 23, 1944, the Allies broke through the last of the three Winter Line positions, the Senger Line (renamed from the Adolf Hitler Line). Meanwhile, elements of U.S. VI Corps advancing on Rome were stalled by strong German resistance at the Caesar C Line, but exploited a gap and broke through on June 2, 1944. American units entered Rome unopposed on June 4, 1944, which had been vacated by the Germans on orders by Hitler, who balked at another Stalingrad-type attrition battle in the Italian capital. Rome, which had been declared an “open city” and thus undefended, also had been subject to constant Allied air bombardment. The glory attached to capturing Rome, which had predominated throughout the Allied campaign, was upstaged just two days later, June 6, 1944, when the Allies launched the much more strategically important Operation Overlord, beginning with the amphibious landings on Normandy aimed at the re-conquest of France and occupied Western Europe, and ultimately the defeat of Germany.

May 10, 2020

May 10, 1941 – World War II: Rudolf Hess parachutes into Scotland to try and negotiate a peace treaty between Britain and Germany

One of the most bizarre events of World War II occurred on May 10, 1941 when Rudolf Hess, Deputy Fuhrer of German leader Adolf Hitler, parachuted into Scotland following a solo flight from Germany. His mission: to negotiate a peace treaty between Britain and Germany.

Hess was a long-time member of the Nazi Party and a staunch Hitler associate, participating in the Beer Hall Putsch, a failed Nazi attempt to overthrown the government of Bavaria, and assisting Hitler in the writing of Mein Kampf, the future Fuhrer’s autobiographical book that outlined Hitler’s political plans for Germany. He signed into law the 1935 Nuremberg Laws that stripped German Jews of their rights as well as the instruments for lebensraum, the German plan for expansion in the east. In 1939, Hess was third in line to succeed Hitler next to Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goring.

During his flight, he was able to evade the heavily defended skies over Britain, but ran short of fuel to his destination and was forced to parachute. He was captured and detained by British authorities and on interrogation, stated that he had come to meet with the Duke of Hamilton (mistakenly believing the latter to be an opponent of the British government) to discuss a possible peace treaty between Britain and Germany. Under this arrangement, Britain would allow Germany a free rein in continental Europe, while Germany would allow Britain to keep its overseas possessions. It must be noted that at that time, the Battle of Britain (the failed German plan to bomb Britain into submission preparatory to a cross-channel invasion), had wound down and Hitler was now fully focused in the east, having just invaded Yugoslavia and Greece (April 1941) and planning the massive invasion of the Soviet Union, slated for June 1941.

When word about Hess’s flight reached Germany, Hitler was furious, stripped Hess of his positions, and ordered that Hess be shot on sight if he returned and portrayed as a madman who flew to Scotland on his own. The German press subsequently depicted Hess as “deluded” and “deranged”. In the aftermath, some speculation arose that Hess had indeed been officially sent to broker a treaty, but failing that, Hitler could disavow involvement in the plan. The British government rejected such speculation. Even so, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin continued to believe that the British had concocted the whole incident.

Hess was held in custody for the remainder of the war and then was returned to Germany in 1946 to stand trial in the Nuremberg Trials. He was found guilty of crimes against peace and conspiracy to commit crimes, and was handed down a life sentence. He served his sentence in the notorious Spandau Prison until his death by hanging suicide in August 1987, at age 93. (Speculation arose that he was murdered, pointing to his advanced age, that he could not have been physically able of hanging himself.)

May 9, 2020

May 9, 1946 – World War II: King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy abdicates

A major casualty of World War II was the Italian monarchy. When World War II broke out in September 1939, Italy remained neutral. But by May 1940 with France verging on defeat by the German onslaught, Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini impressed on King Victor Emmanuel III that by siding with Germany and entering the war, Italy would become the dominant power in the Mediterranean. The king agreed, and Italy’s fate was sealed – for the worse.

Mussolini and the king had ignored their military commanders’ counsel that Italy was unprepared for war. As a result, the Italian army experienced a series of disastrous defeats. As Italian defeat loomed and with his popularity waning, King Victor Emmanuel III fired Mussolini as Prime Minister in July 1943. At the same time, the king sent out feelers to the British and Americans. In September 1943, Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, and declared war on Germany the following month.

But the king feared that his reputation had suffered considerably because of his previous support of Fascism. Thus in April 1944, Victor Emmanuel ceded most of his powers to his son, Crown Prince Umberto. His intent now was to save the monarchy itself. To further his cause, in May 1946, he abdicated in favor of Umberto II. The move failed as on June 2, 1946, in a nation-wide referendum, Italians voted to adopt a republican system. Monarchical rule ended, and the Kingdom of Italy was no more.

May 8, 2020

May 8, 1945 – World War II: Germany surrenders to the Allies

By early 1944, the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union began discussing the proposed surrender document in light of the imminent defeat of Germany. In July 1944, a final text of “unconditional surrender” was finalized.

By May 1945, Germany verged on total defeat with Adolf Hitler dead by his own hand, and the German Army defenseless against the fast-approaching Soviets from the east and Western Allies from the west. German Admiral Karl Donitz, who had succeeded as Head of State as stipulated in Hitler’s last will and testament, made plans to bring the war to an end by surrendering his Army to the Western Allies but not to the Soviets. But his armies were scattered in several large and small pockets from France and the Low Countries to Greece and the Baltic region, as well as in Germany including nearby Poland, the former Czechoslovakia, and Austria.

German commanders in the west, on their own volition or with prompting from Donitz, surrendered to the Western Allies: those in Italy and Western Austria on April 29, 1945, effective May 2, 1945; those in northwest Germany, Netherlands, and Denmark on May 4, 1945, and those in Bavaria and southern Germany on May 5, 1945. As a result, fighting in the west quickly ended. On the other hand, German units facing the Soviets continued to engage in battle, hoping to make a fighting retreat to the west to surrender to the Western Allies.

U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, over-all commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, detected Donitz’s plan, and not wanting the Soviets to suspect that the Western Allies intended to make a separate peace with the Germans, ordered that henceforth no partial surrenders will be made and that the German high command must agree on a complete surrender to the Allies, including the Soviets. Donitz complied and the signing of a surrender instrument was made in Reims, France, on May 7, 1945.

The Soviets took issue with some stipulations in the surrender instrument, as well as the location of the signing itself. They insisted that the formal complete and unconditional surrender must take place in Berlin, the German capital and that the text must place greater emphasis on the Soviet contribution to the war effort. As a result, a second surrender instrument was signed on May 8, 1945.

(Technically, the surrender document was signed at just after midnight on May 9 but was backdated to May 8 as the German surrender had already been broadcast.)

May 7, 2020

May 7, 1915 – Japan sends the “Thirteen Demands” ultimatum to China

In 1915, China

was experiencing severe political, economic, and social problems. Two thousand years

of imperial rule had ended in February 1912, which was followed by a power

struggle between the northern and southern factions. Yuan Shikai, military commander of the

northern faction, soon gained ascendancy, becoming president of the new

republic. Yuan quickly made moves to consolidate power: establishing Beijing as the nation’s

capital and purging political opposition and dissent.

On May 7, 1915, Japan sent the “Thirteen Demands” ultimatum to Yuan with a two-day deadline for response. Yuan, faced with internal political tensions, was forced to cede to the Japanese demands. Japan had gained a large sphere of interest in China and Manchuria with its victories in the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War. Hoping to gain greater control in China, in January 1915, the Japanese government sent the “21 Demands” to China, which would extend Japanese control in Manchuria and the Chinese economy.

Following China’s

rejection of the “21 Demands” and facing pressure from the United States and Britain

(two other countries vying for influence in China),

Japan revised its position

and issued the less harsh “13 Demands”, which China accepted on May 25, 1915.

In the aftermath, the United and States expressed strong disapproval to Japan’s actions. In China, anti-Japanese sentiment grew considerably, together with an upsurge in nationalism.

May 6, 2020

May 6, 1945 – World War II: The Soviet Red Army launches the Prague Offensive

By early May 1945, Nazi Germany was in total collapse. Adolf Hitler had killed himself, Berlin had fallen, and the Allies were closing in from the east and west. The remaining German forces from the Eastern Front were making a desperate rush to reach the west, to surrender to the Western Allies instead of their pursuers, the dreaded Soviet Red Army.

In Bohemia and Moravia, some 1 million German troops became bogged down in their withdrawal when on May 5, the Czech resistance in the capital Prague (as well as other key areas) broke out in an uprising. The German units were the Army Group

Centre and Army Group Ostmark, which were the last intact German military formations. The following day, the Red Army, with 1.7 troops, launched its Prague Offensive, in the process joining the battle on the side of the Czechs.

Fighting continued until May 11 when some 860,000 German troops capitulated. The Prague Offensive was one of the few instances where fighting in the European theater continued after the official German surrender on May 7 and 8.

Prague’s capture by the Soviet Army had far-reaching consequences in the immediate post-war period. The U.S. Third Army had entered Czechoslovakian territory on May 4, and both the Soviets and Western Allies desired the capture of prized Prague, for geopolitical reasons in the post-war period. However, on the request of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, U.S. forces stopped at Plzen, 50 miles to the west of Prague.

In the aftermath of World War II, in 1948, the democratic government in Czechoslovakia was overthrown by a communist coup d’état. A socialist regime was formed that thereafter aligned with the Soviet Union.

May 5, 2020

May 5, 1945 – World War II: Allied forces liberate Denmark

The British Army led by Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery liberated Copenhagen and much of Denmark from German occupation. By this time in the wider conflict of World War II, Nazi Germany was verging on total defeat with its armed forces totally spent; it would surrender unconditionally two days later, May 7.

Denmark, Germany’s neighbor to the north, was not initially considered within Adolf Hitler’s plans of conquest. However, in late 1939, with the British Navy increasing pressure along Norway’s western coastline to stop Swedish iron-ore shipments to Germany, Hitler ordered his military staff to draft plans for an invasion and occupation of Norway. Apart from protecting the vital sea lanes for the iron-ore shipments, the Germany Navy saw the strategic importance of Norway: bases could be established there to launch air reconnaissance missions on the North Atlantic Ocean, and German warships, particularly U-boats, could attack merchant vessels headed for Britain.

Denmark was included in the Norway operation only as an afterthought: German planners recognized that the Danish north airbase at Aalborg was vital for German control of the skies over the Skagerrak Straight between Denmark and Norway. Control of Denmark would also allow Germany to extend its air and naval power to the north, as well as protect the air defenses of the German homeland. Although some German officials preferred to use diplomatic pressure on Denmark to force it to agree to the German terms, in the end, Hitler decided on an invasion. On March 1, 1940, Hitler approved Operation Weserubung, the invasions of Denmark and Norway. On April 1, he set the invasion date for April 9.

Denmark was practically defenseless to fend off the German invasion: it had a small population and territory, its flat terrain was conducive to German mobile warfare, and the absence of mountains precluded any attempt to carry out a prolonged guerilla struggle. Denmark did consist of an archipelago of hundreds of islands, which included Funen, Lolland, and notably Zealand, where Copenhagen, the nation’s capital was located, but these islands’ geographical nearness to Germany allowed for easy access by German land, sea, and air forces.

The Danish military consisted only of two infantry divisions, a total of 10,000-14,000 troops many of whom were new draftees, had no tanks, and possessed only a small navy and air force that had obsolete naval vessels and aircraft, respectively. The Danish government received intelligence information of an imminent invasion, but so as not to provoke Germany, it rejected the recommendation of its military to mobilize the Danish Army (which was placed on high alert), and the Danish Navy was ordered not to resist German naval actions.

In the immediate aftermath of the invasion, Denmark was allowed to maintain much of its internal political and administrative duties, King Christian X remained as the nation’s head of state, and the legislature, police, and judiciary continued to function as before. The Danish people generally were displeased by the German occupation, but also accepted the reality of the situation, especially after France’s defeat only two months later, in June 1940.

By 1943, German-Danish relations had deteriorated, and Denmark’s “politics of cooperation” ended, and the Danish people became hostile toward

the occupation forces. Then when a spate of strikes, civil unrest, and sabotages broke out, and an armed resistance movement began to emerge, German authorities dissolved the Danish government, declared martial law, and enforced anti-dissident measures, including press censorship, banning strikes and mass assemblies, and imposing the death penalty

for saboteurs, as well as ordering the round up of all Jews for deportation.

May 4, 2020

On May 4, 1970 – Vietnam War: National Guardsmen open fire on protesters at Kent State University, Ohio

Before the Cambodian Campaign (April– July 1970) began, President Richard Nixon had announced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S.

ground troops to the operation. Within days, large demonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in the United States, with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio, National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four people and wounding eight others. This incident sparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across the country. Anti-war sentiment already was intense in the United States

following news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My Lai Massacre, where U.S. troops on a search and destroy mission descended on My Lai and My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including women and children.

Vietnam War: North Vietnam and South Vietnam in Southeast Asia.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Toward the endgame

American public outrage further was fueled when in June 1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officially titled: United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense), a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked to the press. The Pentagon Papers showed that successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times misled the American people regarding U.S. involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stop the document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. Supreme Court subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publication continued, and which was also later taken up by the Washington Post and other newspapers.

As in Cambodia, the U.S. high command had

long desired to launch an offensive into Laos to cut off the logistical portion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system located there. But restrained by Laos’ official neutrality, the U.S. military instead carried out secret bombing campaigns in eastern Laos and intelligence gathering operations (the latter conducted by the top-secret Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, MACV-SOG that involved units from Special Forces, Navy SEALS, U.S. Marines, U.S. Air Force, and CIA) there.

The success of the Cambodian Campaign encouraged President Nixon to authorize a similar ground operation into Laos. But as U.S. Congress had prohibited American ground troops from entering Laos, South Vietnamese forces would launch the offensive into Laos with the objective of destroying the Ho Chi Minh Trail, with U.S. forces only playing a supporting role (and remaining within the confines of South Vietnam). The operation also would gauge the combat capability of the South Vietnamese Army in the ongoing Vietnamization program.

In February-March 1971, about 17,000 troops of the South Vietnamese Army, (some of whom were transported by U.S. helicopters in the largest air assault operation of the war), and supported by U.S. air and artillery firepower, launched Operation Lam Son 719 into southeastern Laos. At their furthest extent, the South Vietnamese seized and briefly held Tchepone village, a strategic logistical hub of the Ho Chi Minh Trail located 25 miles west of the South Vietnamese border. The main South Vietnamese column was stopped by heavy enemy resistance and poor road conditions at A Luoi, some 15 miles from the border. North Vietnamese forces, initially distracted by U.S. diversionary attacks elsewhere, soon assembled 50,000 troops against the South Vietnamese, and counterattacked. North Vietnamese artillery particularly was devastating, knocking out several South Vietnamese firebases, while intense anti-aircraft fire disrupted U.S. air transport operations. By early March 1971, the attack was called off, and with the North Vietnamese intensifying their artillery bombardment, the South Vietnamese withdrawal turned into a chaotic retreat and a desperate struggle for survival. The operation was a debacle, with the South Vietnamese losing up to 8,000 soldiers killed, 60% of their tanks, 50% of their armored carriers, and dozens of artillery pieces;

North Vietnamese casualties were 2,000 killed.

American planes were sent to destroy abandoned South Vietnamese armor, transports, and equipment to prevent their capture by the enemy. U.S. air losses were substantial: 84 planes destroyed and 430 damaged and 168 helicopters destroyed and 618

damaged.

Buoyed by this success, in March 1972, North Vietnam launched the Nguyen Hue Offensive (called the Easter Offensive in the West), its first full-scale offensive into South Vietnam, using 300,000 troops and 300 tanks and armored vehicles. By this time, South Vietnamese forces carried practically all of the fighting, as fewer than 10,000 U.S. troops remained in South Vietnam, and who were soon scheduled to leave. North Vietnamese forces advanced along three fronts. In the northern front, the North Vietnamese attacked through the DMZ, and captured the northern provinces, and threatened Hue and Da Nang. In late June 1972, a South Vietnamese

counterattack, supported by U.S. air firepower, including B-52 bombers, recaptured most of the occupied territory, including Quang Tri, near the northern border. In the Central Highlands front, the North Vietnamese objective to advance right through to coastal Qui Nhon and split South Vietnam in two, failed to break through to Kontum and was pushed back. In the southern front, North Vietnamese forces that advanced from the Cambodian border took Tay Ninh and Loc Ninh, but were repulsed at An Loc because of strong South Vietnamese resistance and

massive U.S. air firepower.

To further break up the North Vietnamese offensive, in April 1972, U.S. planes including B-52 bombers under Operation Freedom Train, launched bombing attacks mostly between the 17th and 19th parallels in North Vietnam, targeting military installations, air defense systems, power plants and industrial sites, supply depots, fuel storage facilities, and roads, bridges, and railroad tracks. In May 1972, the bombing attack was stepped up with Operation Linebacker, where American planes now attacked targets across North Vietnam. A few days earlier, U.S. planes air-dropped thousands of naval mines off the North Vietnamese coast, sealing off North Vietnam from sea traffic.

At the end of the Easter Offensive in October 1972, North Vietnamese losses included up to 130,000 soldiers killed, missing, or wounded

and 700 tanks destroyed. However, North Vietnamese forces succeeded in capturing and holding about 50% of the territories of South Vietnam’s northern provinces of Quang Tri, Thua Thien, Quang Nam, and Quang Tin, as well as the western edges of II Corps and III Corps. But the immense destruction caused by U.S. bombing in North Vietnam forced the latter to agree to make concessions at the Paris peace talks.

At the height of North Vietnam’s Easter Offensive, the Cold War took a dramatic turn when in February 1972, President Nixon visited China and met with Chairman Mao Zedong. Then in May 1972, President Nixon also visited the Soviet Union and met with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders. A period of superpower détente followed. China and the Soviet Union, desiring to maintain their newly established friendly relations with the United States, aside from issuing diplomatic protests, were not overly provoked by the massive

U.S. bombing of North Vietnam. Even then, the two communist powers stood by their North Vietnamese ally and continued to send large amounts of military

support.

Since it began in May 1968, the peace talks in Paris had made little progress. Negotiations were held at the main conference hall. However, since

February 1970, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese negotiator Le Duc Tho had been holding secret talks separate from the main negotiations. These secret talks achieved a breakthrough on October 17, 1972 (ten days after the U.S. bombings had forced North Vietnam to return to negotiations), when Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand” and that a mutually agreed draft of a peace agreement was to be signed on October 31, 1972.

However, South Vietnamese President Thieu, when presented with the peace proposal, refused to agree to it, and instead demanded 129 changes to the draft agreement, including that the DMZ be recognized as the international border of a fully sovereign, independent South Vietnam, and that North Vietnam withdraw its forces from occupied

territories in South Vietnam. On November 1972, Kissinger presented Tho with a revised draft incorporating South Vietnam’s demands as well as

changes proposed by President Nixon. This time, the North Vietnamese government was infuriated and believed it had been deceived by Kissinger. On October 26, 1972, North Vietnam broadcast details of the document. In December 1972, talks resumed which went nowhere, and soon broke down on December 14, 1972.

Also on December 14, 1972, the U.S.

government issued a 72-hour ultimatum to North Vietnam to return to negotiations. On the same day, U.S. planes air-dropped naval mines off the North Vietnamese waters, again sealing off the coast to sea traffic. Then on President Nixon’s orders to use “maximum effort…maximum destruction”, on December 18-29, 1972, U.S. B-52 bombers and other aircraft under Operation Linebacker II, launched massive bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam, including Hanoi and Haiphong, hitting airfields, air defense systems, naval bases, and other

military facilities, industrial complexes and supply depots, and transport facilities. As many of the restrictions from previous air campaigns were lifted, the round-the-clock bombing attacks destroyed North Vietnam’s war-related logistical and support capabilities. Several B-52s were shot down in the first days of the operation, but changes to attack methods and the use of electronic and mechanical countermeasures greatly reduced air losses. By the end of the bombing campaign, few targets of military value remained in North Vietnam, enemy anti-aircraft guns had been silenced, and North Vietnam was forced to return to negotiations. On January 15, 1973, President Nixon ended the bombing operations.

One week later, on January 23, negotiations resumed, leading four days later, on January 27, 1973, to the signing by representatives from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG), and the United States of the Paris Peace Accords (officially titled: “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked the end of the war. The Accords stipulated a ceasefire; the release and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of all American and other non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for South Vietnam: a political settlement between the government and the PRG to determine the country’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peaceful reunification of North Vietnam and South Vietnam. As in the 1954 Geneva Accords (which ended the First Indochina War), the DMZ did not constitute a political/territorial border. Furthermore, the 200,000 North Vietnamese troops occupying territories

in South Vietnam were allowed to remain in place.

To assuage South Vietnam’s concerns regarding the last two points, on March 15, 1973, President Nixon assured President Thieu of direct U.S. military air intervention in case North Vietnam violated the

Accords. Furthermore, just before the Accords came into effect, the United States delivered a large amount of military hardware and financial assistance to South Vietnam.

By March 29, 1973, nearly all American and other allied troops had departed, and only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisors remained. A peacekeeping force, called the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnam to monitor and enforce the Accords’ provisions. But as large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS became powerless and failed to achieve its objectives.

For the United States, the Paris Peace Accords meant the end of the war, a view that was not shared by the other belligerents, as fighting resumed, with the ICCS recording 18,000 ceasefire violations between January-July 1973. President Nixon had

also compelled President Thieu to agree to the Paris Peace Accords under threat that the United States would end all military and financial aid to South

Vietnam, and that the U.S. government would sign the Accords even without South Vietnam’s concurrence. Ostensibly, President Nixon could fulfill his promise of continuing to provide military support to South Vietnam, as he had been re-elected in a landslide victory in the recently concluded November 1972 presidential election. However, U.S. Congress, which was now dominated by anti-war legislators, did not bode well for South Vietnam. In June 1973, U.S. Congress passed legislation that prohibited U.S.

combat activities in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia,

without prior legislative approval. Also that year, U.S. Congress cut military assistance to South Vietnam by 50%. Despite the clear shift in U.S. policy, South

Vietnam continued to believe the U.S. government

would keep its commitment to provide military assistance.

May 3, 2020

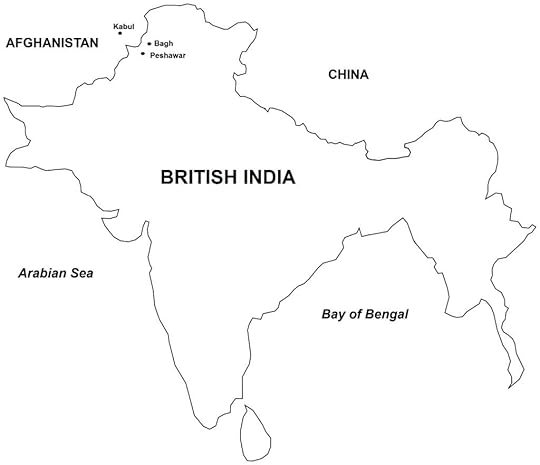

May 3, 1919 – The start of the Anglo-Afghan War of 1919

Upon his ascent to the throne on February 28, 1919, Emir Amanullah I declared Afghanistan’s

independence, doing away with his father’s policy of trying to gain the country’s sovereignty through diplomatic means. The declaration of independence was immensely popular among Afghans, as nationalist sentiments ran high. Emir Amanullah therefore was able to consolidate his hold on power, even as some sectors opposed his leadership. Emir Amanullah

provoked the British by inciting an uprising of the tribal people in Peshawar, British India. Using the uprising as a diversion, he sent his forces across the Afghan-British Indian border to capture the town of Bagh.

Anglo-Afghan War of 1919. The British Empire’s prized possession during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was the Indian subcontinent. Afghanistan served as a neutral zone between the region’s two major powers, the Russian Empire and the British Empire.

(Taken from Anglo-Afghan War of 1919 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

During the early years of the twentieth century, Tsarist Russia and the British Empire in India were the regional powers in Central Asia. The devastating effects of World War I on these two regional powers had a profound effect on the Anglo-Afghan War of

1919. In Russia, the Tsarist government had collapsed and a bitter civil war was raging. Consequently, Russia’s control of its Central Asian domains was weakened. The British Empire, which included the Indian subcontinent (Map 7), was drained financially and militarily, despite emerging victorious in World War I.

With the two regional powers weakened by war, the semi-independent Emirate of Afghanistan moved to assert its right of sovereignty. More important, Emir Habibullah, the Afghan ruler, wanted to annul the Treaty of Gandamak, where Afghanistan had ceded its foreign policy decisions to the British Empire. Adding strength to Emir Habibullah’s diplomatic position was that he had allowed Afghanistan to stay neutral during World War I, despite the strong anti-British sentiments among his people. Emir Habibullah had also spurned Germany and the Ottoman Empire, enemies of the British, who had encouraged him to defy British domination in the region and even launch an attack on British India, at a time when Britain was most vulnerable.

For these reasons, Emir Habibullah asked the British to allow him to present his case for Afghanistan’s independence at the Paris Peace Conference, where the victorious Allied countries had gathered to discuss the end of World War I. Habibullah was assassinated, however, before his case was decided. His son, Amanullah, succeeded to the Afghan throne, despite a rival claim by a family relative.

Upon his ascent to the throne on February 28, 1919, Emir Amanullah I declared Afghanistan’s

independence, doing away with his father’s policy of trying to gain the country’s sovereignty through diplomatic means. The declaration of independence was immensely popular among Afghans, as nationalist sentiments ran high. Emir Amanullah therefore was able to consolidate his hold on power, even as some sectors opposed his leadership. Emir Amanullah provoked the British by inciting an uprising of the tribal people in Peshawar, British India. Using the uprising as a diversion, he sent his forces across the Afghan-British Indian border to capture the town of Bagh.

The British Army quickly quelled the Peshawar uprising and threw back the Afghan forces across the border. The Afghans clearly were unprepared for war – although having sufficient numbers of soldiers as well as being assisted by tribal militias, they possessed obsolete weapons, which even then were in short supply.

By contrast, the British were a modern fighting machine because of the technological advances they had made in World War I. The British suffered from a shortage of soldiers, since much of their forces had yet to return to India from their deployment to other British territories during World War I. The British air attacks on Kabul devastated Afghan morale, forcing Emir Amanullah to sue for peace.

Afghanistan and the British Empire entered into peace negotiations to end the war. In the peace treaty that emerged from these negotiations, the British granted conciliatory terms to the Afghans, including returning Afghanistan’s right of foreign policy. The British, therefore, essentially recognized Afghanistan as a sovereign state. By this time, Afghanistan already had been nominally independent, as it had established diplomatic relations with the newly formed Soviet Union and its independence was gaining recognition by the international community.

Afghanistan and the British Empire retained the Durand Line as their common border. After the

war, Afghanistan continued to serve as a buffer zone between the Russians and the British, because of the

end of the previous non-aggression treaties between Tsarist Russia and the British Empire following the emergence of the Soviet Union after the Russian Civil War.