Daniel Orr's Blog, page 99

May 2, 2020

May 2, 1982 – Falklands War: The Argentine light cruiser ARA General Belgrano is sunk by a British submarine torpedo

The British Navy declared a 200-mile exclusion zone around the waters of the Falkland Islands, warning that all non-British ships that entered the zone would be attacked. The Argentine Navy decided to challenge the blockade, sending two flotillas of ships, one led by the aircraft carrier, the ARA Veinticinco de Mayo from the north of the Falklands, and the other led by the light cruiser, ARA General Belgrano from the south. The Argentine plan was for these two fleets to use a pincers movement to trap and destroy the British

fleet.

A British submarine spotted the southern arm of the pincers and on May 2, fired three torpedoes at the ARA General Belgrano. The Argentinean ship was hit and sunk, killing over 300 sailors. Fearing more submarine attacks, the Argentine Navy cancelled the operation and ordered its ships to return to port. Thereafter, Argentine ships did not venture out to sea.

In 1982,

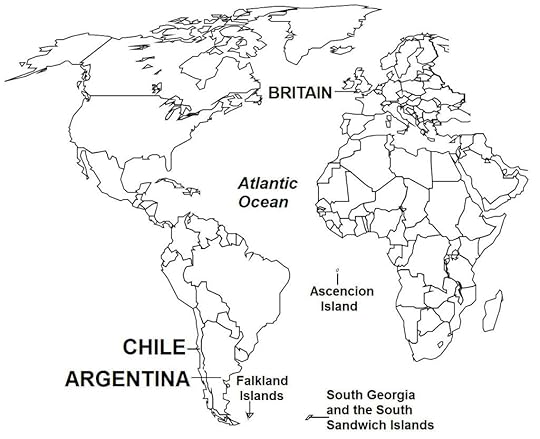

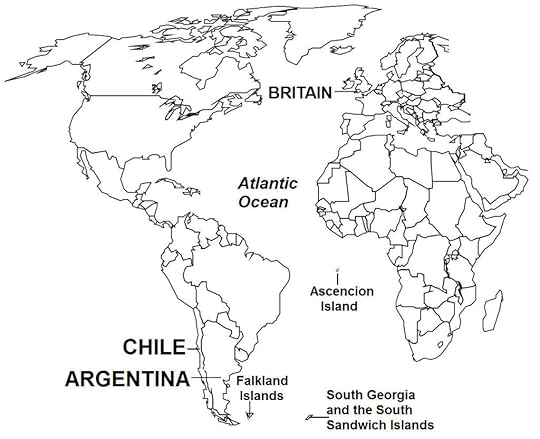

In 1982, Argentina and Britain went to war for possession of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

(Taken from Falklands War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background

In early 1982, Argentina’s ruling military junta, led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, was facing a crisis of

confidence. Government corruption, human rights violations, and an economic recession had turned initial public support for the country’s military regime into widespread opposition. The pro-U.S. junta had come to power through a coup in 1976, and had crushed a leftist insurgency in the “Dirty War” by

using conventional warfare, as well as “dirty” methods, including summary executions and forced disappearances. As reports of military atrocities became known, the international community

exerted pressure on General Galtieri to implement reforms.

In its desire to regain the Argentinean people’s moral support and to continue in power, the military government conceived of a plan to invade the Falkland Islands, a British territory located about 700 kilometers east of the Argentine mainland. Argentina

had a long-standing historical claim to the Falklands,

which generated nationalistic sentiment among Argentineans. The Argentine government was determined to exploit that sentiment. Furthermore,

after weighing its chances for success, the junta concluded that the British government would not likely take action to protect the Falklands, as the

islands were small, barren, and too distant, being located three-quarters down the globe from Britain.

The Argentineans’ reasoning was not without merit. Britain under current Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was experiencing an economic recession, and in 1981, had made military cutbacks that would have seen the withdrawal from the Falklands of the HMS Endurance, an ice patrol vessel and the British Navy’s only permanent ship in the southern Atlantic

Ocean. Furthermore, Britain had not resisted when in 1976, Argentinean forces occupied the uninhabited Southern Thule, a group of small islands that forms a part of the British-owned South Sandwich Archipelago, located 1,500 kilometers east of the Falkland Islands.

In the sixteenth century, the Falkland Islands first came to European attention when they were signed by Portuguese ships. For three and a half centuries thereafter, the islands became settled and controlled at various times by France, Spain, Britain, the United States, and Argentina. In 1833, Britain gained uninterrupted control of the islands, establishing a permanent presence there with settlers coming mainly from Wales and Scotland.

In 1816, Argentina gained its independence and, advancing its claim to being the successor state of the former Spanish Argentinean colony that had included “Islas Malvinas” (Argentina’s name for the Falkland Islands), the Argentinean government declared that the islands were part of Argentina’s territory. Argentina also challenged Britain’s account of the events of 1833, stating that the British Navy gained control of the islands by expelling the Argentinean civilian authority and residents already present in the Falklands. Over time, Argentineans perceived the British control of the Falklands as a misplaced vestige of the colonial past, producing successive generations of Argentineans instilled with anti-imperialist sentiments. For much of the twentieth century, however, Britain and Argentina

maintained a normal, even a healthy, relationship, although the Falklands issue remained a thorn on both sides.

After World War II, Britain pursued a policy of decolonization that saw it end colonial rule in its vast territories in Asia and Africa, and the emergence of many new countries in their places. With regards to the Falklands, under United Nations (UN) encouragement, Britain and Argentina met a number of times to decide the future of the islands. Nothing substantial emerged on the issue of sovereignty, but the two sides agreed on a number of commercial ventures, including establishing air and sea links between the islands and the Argentinean mainland, and for Argentinean power firms to supply energy to the islands. Subsequently, Falklanders (Falkland residents) made it known to Britain that they wished to remain under British rule. As a result, Britain reversed its policy of decolonization in the Falklands and promised to respect the wishes of the Falklanders.

May 1, 2020

May 1, 1995 – Croatian War of Independence: Croatian forces launch a lightning attack on Serb-held Western Slavonia

On May 1, 1995, the Croatian Army launched a lightning attack on Serb-held Western Slavonia. By the next day, the whole region had fallen to the Croatians, forcing the Serb forces and nearly all the civilian population there to flee to Bosnia-Herzegovina. Then on August 4, the Croatians, supported by Bosnian Army units, attacked northern Dalmatia and Lika. By the fourth day of the attack, Serbian forces had been routed and the Croatian Serb government of Krajina was in total collapse. Some 200,000 ethnic Serb civilians fled the fighting and ended up as refugees.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

(Taken from Croatian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

By the late 1980s, Yugoslavia was faced with a major political crisis, as separatist aspirations among its ethnic populations threatened to undermine the country’s integrity (see “Yugoslavia”, separate article). Nationalism particularly was strong in Croatia and Slovenia, the two westernmost and wealthiest Yugoslav republics. In January 1990, delegates from Slovenia and Croatia walked out from an assembly

of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country’s communist party, over disagreements with their Serbian counterparts regarding proposed reforms to the party and the central government. Then in the first multi-party elections in Croatia held in April and May 1990, Franjo Tudjman became president after running a campaign that promised greater autonomy for Croatia and a reduced political union with Yugoslavia.

Ethnic Croatians, who comprised 78% of Croatia’s population, overwhelmingly supported Tudjman, because they were concerned that Yugoslavia’s

national government gradually had fallen under the control of Serbia, Yugoslavia’s largest and most

powerful republic, and led by hard-line President Slobodan Milosevic. In May 1990, a new Croatian Parliament was formed and subsequently prepared a new constitution. The constitution was subsequently passed in December 1990. Then in a referendum held in May 1991 with Croatian Serbs refusing to participate, Croatians voted overwhelmingly in support of independence. On June 25, 1991, Croatia,

together with Slovenia, declared independence.

Croatian Serbs (ethnic Serbs who are native to Croatia) numbered nearly 600,000, or 12% of Croatia’s total population, and formed the second largest ethnic group in the republic. As Croatia

increasingly drifted toward political separation from Yugoslavia, the Croatian Serbs became alarmed at the thought that the new Croatian government would carry out persecutions, even a genocidal pogrom against Serbs, just as the pro-Nazi ultra-nationalist Croatian Ustashe government had done to the Serbs, Jews, and Gypsies during World War II. As a result, Croatian Serbs began to militarize, with the formation of militias as well as the arrival of armed groups from Serbia.

Croatian Serbs formed a population majority in south-west Croatia (northern Dalmatian and Lika). There, in February 1990, they formed the Serb Democratic Party, which aimed for the political and territorial integration of Serb-dominated lands in Croatia with Serbia and Yugoslavia. They declared that if Croatia wanted to secede from Yugoslavia, they, in turn, should be allowed to separate from Croatia. Serbs also interpreted the change in their

status in the new Croatian constitution as diminishing their civil rights. In turn, the Croatian government opposed the Croatian Serb secession and was determined to keep the republic’s territorial

integrity.

In July 1990, a Croatian Serb Assembly was formed that called for Serbian sovereignty and autonomy. In December, Croatian Serbs established the SAO Krajina (SAO is the acronym for Serbian Autonomous Oblast) as a separate government from Croatia in the regions of northern Dalmatia and Lika.

Croatian Serbs formed a majority population in two other regions in Croatia, which they also transformed into separate political administrations called SAO Western Slavonia, and SAO Eastern Slavonia (officially SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western

Syrmia). (Map 17 shows locations in Croatia where ethnic Serbs formed a majority population.) In a referendum held in August 1990 in SAO Krajina, Croatian Serbs voted overwhelmingly (99.7%) for

Serbian “sovereignty and autonomy”. Then after a second referendum held in March 1991 where Croatian Serbs voted unanimously (99.8%) to merge SAO Krajina with Serbia, the Krajina government

declared that “… SAO Krajina is a constitutive part of the unified state territory of the Republic of Serbia”.

April 30, 2020

April 30, 1975 – Vietnam War: Saigon falls to North Vietnamese forces

The end for South Vietnam came on April 30, 1975 when North Vietnamese forces, after launching an artillery barrage on the capital Saigon one day earlier, attacked and entered the city with virtually no opposition, as the South Vietnamese military high command had ordered its troops to lay down their weapons. The Mekong Delta south of Saigon soon also fell. By early May 1975, the war was over.

North Vietnam and South Vietnam in Southeast Asia.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

The Fall of Saigon

North Vietnamese leaders, who also were surprised by their quick successes, now decided to advance their timeline for conquering South Vietnam by 1976 to capturing Saigon by May 1, 1975. The offensive on Saigon, called the Ho Chi Minh Campaign and involving some 150,000 troops and supplied with armored and artillery units, began on April 9, 1975 with a three-pronged attack on Xuan Loc, a city located 40 miles northeast of the national capital and called the “gateway to Saigon”. Resistance by the 18,000-man South Vietnamese garrison (which was outnumbered 6:1) was fierce, but after two weeks of desperate fighting by the defenders, North Vietnamese forces had broken through, with the road to Saigon now lying open.

In the midst of the battle for Xuan Loc, on April 10, 1975, U.S. President Gerald Ford again appealed to U.S. Congress for emergency assistance to South Vietnam, which was denied. South Vietnamese morale plunged even further when on April 17, 1975 neighboring Cambodia fell to the communist Khmer Rouge forces. On April 21, 1975, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu resigned (and went into exile abroad) and was replaced by a government to try and negotiate a settlement with North Vietnam. But the latter, by now in an overwhelmingly superior position, rejected the offer.

By April 27, 1975, some 130,000 North Vietnamese troops had encircled Saigon, with some intense fighting breaking out at the outskirts and bridges at the city’s approaches. The South Vietnamese military set up five defensive lines north, west, and east of Saigon, manned by 60,000 troops and augmented by other units that had retreated from the north. However, by this time, the South Vietnamese forces were verging on collapse, with morale and discipline breaking down, desertions widespread, and ammunition and supplies running low. In Saigon, desperation and anarchy reigned, with the government’s imposition of martial law failing to quell the panic-stricken population.

The end came on April 30, 1975 when North Vietnamese forces, after launching an artillery barrage on the city one day earlier, attacked Saigon and entered the city with virtually no opposition,

as the South Vietnamese military high command had ordered its troops to lay down their weapons. The Mekong Delta south of Saigon soon also fell. By early May 1975, the war was over.

In the lead-up to Saigon’s fall, thousands of South Vietnamese made a desperate attempt to leave the

country. As early as March 1975, the U.S. government had begun to evacuate its citizens and other foreign nationals, as well as some South Vietnamese civilians. In April 1975, the U.S. launched Operation New Life, where some 110,000 South Vietnamese were evacuated, the great majority consisting of South Vietnamese military officers, Catholics, bureaucrats, businessmen, locals employed in U.S. military and civilian facilities, and other Vietnamese who had cooperated or associated

with the United States and thus were considered to be potential targets for North Vietnamese reprisals. Also in the final days of the war, the U.S. military conducted Operation Frequent Wind, where the remaining U.S. nationals and American troops (U.S.

Marines) were evacuated by helicopters from the Defense Attaché Compound and U.S. Embassy in Saigon onto U.S. ships waiting offshore. The chaotic

evacuation, which succeeded in moving over 7,000 Americans and South Vietnamese, was captured in film, with dramatic camera footage showing thousands of frantic South Vietnamese civilians crowding the gates of the U.S. Embassy, and helicopters being thrown overboard the packed decks of U.S. carriers to make room for more evacuees to arrive.

Some 58,000 U.S. soldiers died in the Vietnam War, with 300,000 others wounded. South Vietnamese casualties include: 300,000 soldiers and 400,000 civilians killed, with over 1 million wounded. North Vietnamese and Viet Cong human losses are variously estimated at between 450,000 and over 1 million soldiers killed and 600,000 wounded; 65,000 North Vietnamese civilians also lost their lives.

Aftermath of the Vietnam War

The war had a profound, long-lasting effect on the United States. Americans were bitterly divided by it, and others became disillusioned with the government. War cost, which totaled some $150 billion ($1 trillion in 2015 value), placed a severe strain on the U.S. economy, leading to budget deficits, a weak dollar, higher inflation, and by the 1970s,

an economic recession. Also toward the end of the war, American soldiers in Vietnam suffered from low morale and discipline, compounded by racial and social tensions resulting from the civil rights movement in the United States during the late 1960s and also because of widespread recreational drug use

among the troops. During 1969-1972 particularly and during the period of American de-escalation and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, U.S. soldiers became increasingly unwilling to go to battle, which resulted in the phenomenon known as “fragging”, where soldiers, often using a fragmentation grenade, killed their officers whom they thought were overly zealous and eager for combat action.

Furthermore, some U.S. soldiers returning from Vietnam were met with hostility, mainly because the war had become extremely unpopular in the United States, and as a result of news coverage of massacres and atrocities committed by American units on Vietnamese civilians. A period of healing and reconciliation eventually occurred, and in 1982,

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was built, a national monument in Washington, D.C. that lists the names of servicemen who were killed or missing in the war.

Following the war, in Vietnam and Indochina, turmoil and conflict continued to be widespread. After South Vietnam’s collapse, the Viet Cong/NLF’s PRG was installed as the caretaker government. But as Hanoi de facto held full political and military control, on July 2, 1976, North Vietnam annexed South Vietnam, and the unified state was called the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Some 1-2 million South Vietnamese, largely consisting of former government officials, military officers, businessmen, religious leaders, and other “counter-revolutionaries”, were sent to re-education camps, which were labor camps, where inmates did various kinds of work ranging from dangerous land mine field clearing, to less perilous construction and

agricultural labor, and lived under dire conditions of starvation diets and a high incidence of deaths and diseases.

In the years after the war, the Indochina refugee crisis developed, where some three million people, consisting mostly of those targeted by government repression, left their homelands in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, for permanent settlement in other countries. In Vietnam, some 1-2 million departing refugees used small, decrepit boats to embark on perilous journeys to other Southeast Asian nations. Some 200,000-400,000 of these “boat people” perished at sea, while survivors who eventually reached Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and other destinations were sometimes met there with hostility. But with United Nations support, refugee camps were established in these Southeast Asian countries to house and process the refugees. Ultimately, some 2,500,000 refugees were resettled, mostly in North America and Europe.

The communist revolutions triumphed in Indochina: in April 1975 in Vietnam and Cambodia, and in December 1975 in Laos. Because the United

States used massive air firepower in the conflicts, North Vietnam, eastern Laos, and eastern Cambodia were heavily bombed. U.S. planes dropped nearly 8 million tons of bombs (twice the amount the United States dropped in World War II), and Indochina became the most heavily bombed area in history. Some 30% of the 270 million so-called cluster bombs dropped did not explode, and since the end of the war, they continue to pose a grave danger to the local population, particularly in the countryside. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) has killed some 50,000 people in Laos alone, and hundreds more in Indochina are killed or maimed each year.

The aerial spraying operations of the U.S. military, carried out using several types of herbicides but most commonly with Agent Orange (which contained the highly toxic chemical, dioxin), have had a direct impact on Vietnam. Some 400,000 were directly

killed or maimed, and in the following years, a segment of the population that were exposed to the chemicals suffer from a variety of health problems,

including cancers, birth defects, genetic and mental diseases, etc.

Some 20 million gallons of herbicides were sprayed on 20,000 km2 of forests, or 20% of Vietnam’s total forested area, which destroyed trees, hastened erosion, and upset the ecological balance, food chain, and other environmental parameters.

Following the Vietnam War, Indochina continued to experience severe turmoil. In December 1978, after a period of border battles and cross-border

raids, Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia (then known as Kampuchea) and within two weeks, overwhelmed the country and overthrew the communist Pol Pot regime. Then in February 1979, in reprisal for Vietnam’s invasion of its Kampuchean ally, China launched a large-scale offensive into the northern regions of Vietnam, but

after one month of bitter fighting, the Chinese forces withdrew. Regional instability would persist into the

1990s.

April 29, 2020

April 29, 1991 – Western Sahara War: Resolution 690 establishes the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara

Spain’s failure in 1975 to hold the referendum in Spanish Sahara and ceding the territory’s administration to Morocco and Mauritania gave rise to the Western Sahara War. By the 1980s, the regional and international communities still hoped to hold a referendum that would be used as a basis to determine Western Sahara’s political future, either for full independence or political integration with Morocco.

On August 30, 1988, the Moroccan government and Polisario Front leadership agreed in principle to settle their differences using the “peace proposals” offered by the UN in cooperation with the Organization of African Unity (OAU). The peace proposals outlined the terms for a ceasefire, a new census to update the 1974 Spanish population count, and a referendum. The UNSC then passed on September 20, 1988 Resolution 621 establishing the position of a UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Western Sahara, and on June 27, 1990, Resolution 658 that approved the “Peace Proposals” and called on the two sides to cooperate fully to achieve a resolution.

Then on April 29, 1991, the UNSC passed Resolution 690 establishing the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara

(MINURSO; Spanish: Misión de las Naciones

Unidas para la Organización de un Referéndum en el Sáhara Occidental;), which consisted of three components: a civilian arm to conduct a new census and carry out a referendum; a security unit to perform police functions; and a military force to enforce the ceasefire. MINURSO representatives began to arrive in the territory by September of that year. On September 6, 1991, Morocco and the

Polisario Front signed a ceasefire. An estimated total of 14,000 to 20,000 persons were killed in the war.

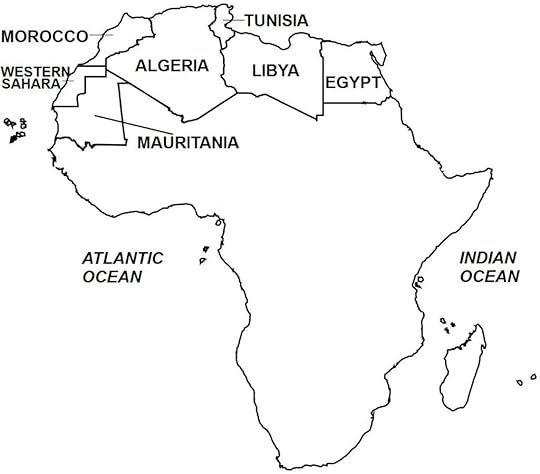

Map showing location of Western Sahara.

(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

On December 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292 declaring the UN’s interest in evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawis in the Spanish

territory. For this purpose, the UN formed the UN Decolonization Committee, which in May – June 1975, carried out a fact-finding mission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15,

1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the general population in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara, however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under the leadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy such

support. In Algeria, the UN Committee found strong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self-determination.

Algeria previously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an Arab League summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria was openly defending the Polisario Front’s struggle for independence, a support that later would include military and economic aid and would have a crucial effect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of King Mohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claim and asked Spain to postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish government granted the Moroccan request. In June 1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UN Decolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision, which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers to Spanish Sahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the

Mauritanian entity”;

3. There existed “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance between the Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara. They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating to

the land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and the territory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJ concluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorial

sovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Morocco or the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such a nature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular, … the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvement radicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of the court’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respective claims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish any tie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing the post-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri and Polisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers,

Algeria to negotiate the transfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economic

concessions to Spain, particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did not prosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greater pressures exerted by the other competing parties.

Shortly after the ICJ decision was released, King Hassan II announced that Morocco would hold the “Green March”, set for November 6, 1975, and called on Moroccans to march to and occupy Spanish Sahara. On that date, the Green March (the color

green symbolizing Islam) was carried out, with some 350,000 Moroccan civilians, protected by 20,000 soldiers, crossed the border from Tarfaya in southern

Morocco and occupied some border regions in northern Spanish Sahara. Under instructions from the Spanish central government in Madrid, Spanish troops did not resist the incursion. On November 9, the marchers returned to Morocco, on orders of King Hassan II who declared the action a success.

On October 31, 1975, six days before the Green March began, units of the Moroccan Army entered Farsia, Haousa and Jdiriya in northeast Saharan territory to deter Algerian intervention. Spain had protested the Moroccan action to the UN in a futile attempt to have the international body stop the march; instead, the United Nations Security Council

(UNSC) passed Resolution 380 that deplored the march and called on Morocco to withdraw from the territory.

The timing of the escalating crisis could not have come at a worse time for Spain. In late October 1975, General Francisco Franco, Spain’s dictator, was terminally ill and soon passed away on November 20, 1975. In the period before and after his death, Spain

underwent great political uncertainty, as the sudden void left by General Franco, who had ruled for 40 years, threatened to ignite a political power struggle. The tenuous government, now led by King Juan Carlos as head of state, was unwilling to face a potentially ruinous war. World-wide colonialism was

at its twilight– just one year earlier, Portugal, one of the last colonial powers, had agreed to end its long colonial wars against African nationalist movements, eventually leading to the independences in 1975 of its African possessions of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea (since 1973), Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

By late October 1975, Spanish officials had begun to hold clandestine meetings in Madrid with representatives from Morocco and Mauritania. As a precaution for war, in early November 1975, Spain

carried out a forced evacuation of Spanish nationals from the territory. On November 12, further negotiations were held in the Spanish capital, culminating two days later (November 14) in the

signing of the Madrid Accords, where Spain ceded the administration (but not sovereignty) of the territory, with Morocco acquiring the regions of El-Aaiún,

Boujdour, and Smara, or the northern two-thirds of the region; while Mauritania the Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros) region, or the southern third; in exchange for Spain acquiring 35% of profits from the territory’s phosphate mining industry as well as off-shore fishing rights. Joint administration by the three parties through an interim government (led by the territory’s Spanish Governor-General) was undertaken in the transitional period for full transfer to the new Moroccan and Mauritanian authorities. (The Madrid Accords was not, and also since has not, been recognized by the UN, which officially continued to regard Spain as the “de jure”, if not “de facto”, administrative authority over the territory;

furthermore, the UN deems the conflict region as occupied territory by Morocco and, until 1979, also by Mauritania.)

On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from the territory, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would

include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

April 28, 2020

April 28, 1941 – Anglo-Iraqi War of 1941: British authorities announce that more troops would be landed in Basra, which is rejected by the Iraqi government

On April 28, 1941, when the British announced that more British soldiers would be landed in Basra,

Iraqi Prime Minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani rejected the request, as he earlier had demanded that the first batch of British troops must leave the country before more troops could land. The British government, however, again invoked the 1930 treaty and carried out the landing at Basra the following day, which was not resisted by the Iraqis.

(Taken from Anglo-Iraqi War of 1941 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

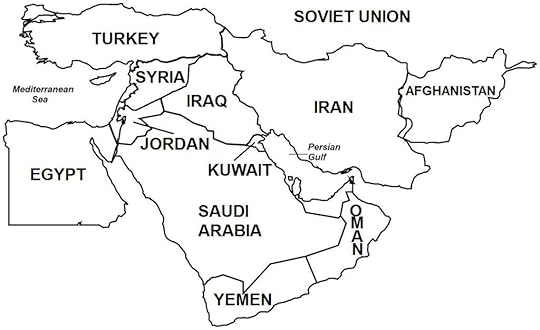

Iraq in the Middle East.

Background

During World War I, British forces seized control of Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq, Figure 33) from the Ottoman Empire. After the war, the British government tried to set up a protectorate over Mesopotamia using a League of Nations mandate (called the British Mandate for Mesopotamia), but

faced strong opposition from the local people, who in 1920 launched protest actions that degenerated into riots that killed thousands of civilians and hundreds of British soldiers. As a result, the British acquiesced and held a referendum in Mesopotamia, where the overwhelming majority (96%) of the local population voted against the UN mandate and allowed the establishment of a ruling monarchy. Thus, in August 1921, the British government granted the semi-independence of Mesopotamia as the “Kingdom of Iraq” in the territories that consisted of the former Ottoman vilayets (provinces) of (Kurdish-dominated) Mosul, and (Islamic Sunni- and Shiite Arab-dominated) Baghdad, and Basrah, and ruled by King Faisal I, whom the British had brought in from Arabia and who was not native to Mesopotamia.

The British retained full control of Iraq, however, which they formalized in October 1922 by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty that allowed the Iraqi government to exercise control only over domestic affairs, while the British dictated Iraq’s foreign and military policies. In October 1932, Britain granted the Kingdom of Iraq nominal “full independence”, which was subject to another Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, signed in June 1930, that contained the following two major provisions: the British military was allowed to maintain two airbases in Iraq; and the British military was allowed unlimited,

unrestricted access inside Iraq, including the use of roads, railways, waterways, ports, and airports in Iraq to carry out troop movements.

British interests in Iraq were centered on Iraq’s

large petroleum industry, which was owned and operated by a British firm. In the late nineteenth century, Mesopotamia was thought to contain large oil deposits, attracting the interests of British and other European investors who courted favor with the Ottoman Empire, at that time the colonial ruler of Mesopotamia. The outbreak of World War I, however, scuttled these plans, and by the end of the war, only the British, having gained possession of Mesopotamia, resumed the search for oil. In 1927, oil in large commercial quantities was indeed discovered, and the British developed Iraq’s petroleum industry, soon leading to Britain’s commercial, political, and military domination of Iraq.

However, the British occupation was opposed by many Iraqis, particularly those belonging to the Arab nationalist movement, who wanted the foreigners to leave and viewed the British as not unlike the Ottomans before them who had subjugated the local population, and exploited Mesopotamia’s natural resources. The concept of Arab nationalism advocated political unification of all Arabs across the regions of northern Africa, the Middle East, and Western Asia. In Iraq, the Arab nationalists grew in

power and influence, occupying leading government and military positions; however, they were still unable to challenge British military authority.

In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe. Britain was totally consumed in the conflict and in the early years, appeared headed for defeat to Germany and the Axis Powers. For the Iraqi nationalists, Britain’s preoccupation offered the perfect opportunity to take action. At the start of the war, the Iraqi government broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, but did not declare war. Since the 1930s, high-ranking Iraqi military officers belonging to the Iraqi Arab nationalist movement, called the “Circle of Seven”, were nurturing friendly relations with Nazi Germany, which was then rising in power. And by the outbreak of World War II, Iraq’s political climate was under extreme pressure and ready to break out into open warfare, with the ruling monarchy and other political elements remaining pro-British, and Arab nationalists, backed by the military, being pro-German (i.e. anti-British).

On April 1, 1941, former Prime Minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani, supported by high-ranking Iraqi military officers, overthrew the government of Regent Prince Abdul Illah and Prime Minister Taha al-Hashimi. Prince Abdul Illah was regent of King Faisal II, who was a minor at six years old at that time. Gaylani took over power as Prime Minister and formed a government that was determined to limit or end British domination of the country. The new government retained the monarchy, however, but named a new regent for King Faisal II. Through secret talks with Axis representatives, particularly Fritz Grobba (the German Ambassador in Iraq), on April 10, 1941 Prime Minister Gaylani received guarantees of military assistance from Germany, as well as from Italy (which had entered the war on the Axis side in June 1940).

The Iraqi coup had taken Britain by surprise, as the British, since 1937, had withdrawn most of their forces from Iraq, leaving only a small military contingent (composed mostly of native troops) to guard two air force bases (at Habbaniya and Shaibah). The British did not openly recognize Gaylani’s government, but also did not end diplomatic relations with it. The British soon learned of Gaylani’s secret military arrangement with Germany, and thus rushed to send troops and weapons to Iraq, which were to be assembled from available units in Asia

that were not yet engaged in the rapidly expanding world war. On April 12, 1941, the first units from British India departed aboard naval transports for southern Iraq.

On April 16, the British notified the Iraqi government that they were invoking the 1930 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty and would be landing troops in Iraq. Prime Minister Gaylani, who days earlier had said that he would respect the treaty, replied by saying that he did not object but that the British troops, once landed, must proceed immediately to their destination, which the British said was Palestine. The British, however, did not intend the troops to move beyond Iraq but be used to take down the Gaylani regime.

On April 18, 1941, the first British troops arrived, being landed in Shaibah air base. The next day, the first of the main British forces from India landed in Basra, located in southern Iraq. In the following weeks, the landed British Indian forces strengthened their presence in and around Basra.

However, the British air base in Habbaniya, located in central Iraq, was surrounded by and vulnerable to attack by hostile forces. The British there had some 2,000 mostly native troops, commanded by British officers, and about 80 planes, which suffered from varying levels of obsolescence and combat capability. Thus, in the following days, more troops and modern planes were sent to Habbaniya by air, while the existing planes there

were retrofitted for greater combat strength.

Britain also assembled two relief forces from Palestine (which it governed at that time through another League of Nations Mandate): first, a

contingent from the Arab League (which was the regular armed forces of the Transjordan, a semi-independent emirate); and second, a combat unit called Habbaniya force (“Habforce”), which was to depart from Palestine. These two forces, however, would not participate in the coming defense of Habbaniya base, as war had broken out before their arrival.

On April 28, 1941, when the British announced that more British soldiers would be landed in Basra,

Prime Minister Gaylani rejected the request, as he earlier had demanded that the first batch of British troops must leave the country before more troops

could land. The British government, however, again invoked the 1930 treaty and carried out the landing at Basra the following day, which was not resisted by the Iraqis.

April 27, 2020

April 27, 1941 – World War II; German troops enter Athens, meeting no resistance

German XVII Mountain Corps, comprising the eastern prong of the Axis offensive, reached Volos

on April 21, 1941. Three days later, a German advance using battle tanks through the Thermopylae Pass was stopped by British rear guard artillery and armored units. On April 25, a German flanking maneuver around the pass forced the British to withdraw to avoid encirclement. A final, hastily formed defensive line at Thebes, located 60 miles from Athens, also became threatened by a German flanking maneuver, forcing the British rear guard there to retreat toward the Peloponnesus, Greece’s southernmost region. On April 27, 1941, advance units of the German Twelfth Army entered Athens without meeting any resistance.

At this time, the British High Command had been carrying out troop evacuations at various points, including at Volos and Piraeus. The Germans, determined to capture the whole W Force, did away with its infantry units because of their lack of mobility, and tasked the ground pursuit to their armored, motorized infantry, and mountain units. To cut off W Force’s retreat to the Peloponnesus, on April 26, 1941, German paratroopers were air-dropped into the Isthmus of Corinth to seize

the bridge connecting the Greek mainland to the Peloponnesus. The bridge was taken, but a stray projectile from a British anti-aircraft gun struck the explosives on the bridge that the British had placed earlier but had failed to set it off. The resulting explosion destroyed the bridge, but German engineering crews quickly built a temporary replacement span. The German paratroopers had also arrived late, as W Force had already crossed into the Peloponnesus and had moved south to Kalamata and other southern ports for evacuation to Crete and Egypt.

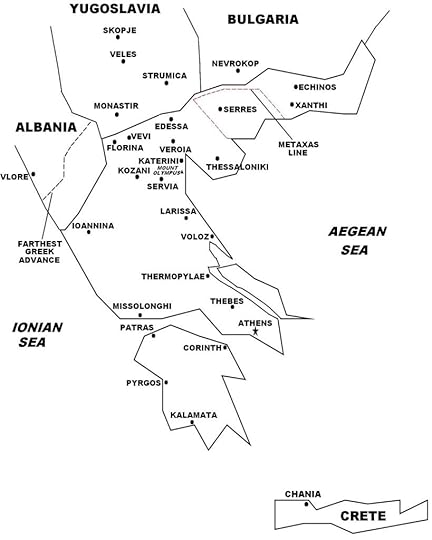

Axis invasion of Greece.

(Taken from Invasion of Greece – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In early March 1941, as German forces massed at the Bulgarian-Greek border, Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas was convinced that an invasion was imminent. Metaxas then requested military assistance from the British government. Britain

sent a force consisting of British, Australian, and New Zealander units from Egypt, a total of 60,000 troops that arrived in Greece in March 1941 under Operation Lustre. This contingent was commonly called W Force (named after its commander, British

General Henry Maitland Wilson).

Disagreement immediately arose between General Wilson and the Greek top commander General Alexander Papagos, regarding the deployment of their combined forces to confront the German invasion. By March 1941, some 70% (or 14 divisions) of the Greek Army was still locked in combat with Italian forces in southern Albania (Greco-Italian War, separate article), leaving an insufficient six Greek divisions and the W Force to defend the rest of Greece’s northern frontier. Greek and British commanders concluded that their combined forces were inadequate to stop the Germans coming from the northeast; for example, 12 Allied divisions alone were needed to adequately

defend the Greek-Bulgarian border. Furthermore, more units were needed to guard the Greek-Yugoslav border, although at this time, Yugoslavia had announced its neutrality in the emerging crisis. Also because Yugoslavia might remain a non-belligerent, and Greek-Yugoslav relations were friendly since both were pro-British to varying degrees, Greece kept its border with Yugoslavia only lightly defended. Nearly the whole Greek Army was deployed at both ends of the country’s northern frontier, in the west at the Albanian front, and in the east at the Metaxas Line, the vaunted 125-mile series of fortifications facing the Bulgarian border. As in much of Greece, the northern frontier was dominated by rugged mountain ranges, with the Rhodope Mountains in the east and the Pindus Mountains in the west, with few passes whose steep, narrow roads allowed only the

movement of pack animals. Consequently, Greek military planning incorporated these excellent natural barriers in the defense of the northern frontier.

However, Greece was vulnerable along two areas, both in the Yugoslav-Greek border, at the Vardar River Valley and the so-called Monastir Gap, where a major invasion could potentially be launched into Greece.

On March 25, 1941, Yugoslavia became allied with Germany and Italy by signing the Tripartite Pact, which clearly was an ominous development for Greece. But two days later, a coup in Belgrade toppled the pro-Axis Yugoslav government, and a military regime took over that had pro-British leanings. In Germany, a livid Hitler ordered hasty

preparations for an invasion of Yugoslavia (called Operation 25), which was to be launched together with the attack on Greece. Ironically, the two-day alliance of Yugoslavia with the Axis gave Greece full security along the Greek-Yugoslav border, since in the corresponding secret German-Yugoslav protocol, Germany promised to respect Yugoslavia’s sovereignty, and German troops would not enter

Yugoslavian territory. But with the March 27 Belgrade coup, Hitler decided that Germany was not anymore bound by the secret protocol and indeed, that the main German attack on Greece would be made through Yugoslavia, particularly through the Vardar River Valley and Monastir Gap.

Meanwhile, Yugoslavia was unaware of German preparations for Operation 25, and continued to espouse its neutrality, and announced its desire to maintain friendly relations with Germany. The Yugoslav military also did not fully mobilize its forces so as not to provoke Hitler. And on April 3, 1941 (just three days before Germany invaded), in a meeting of British, Greek, and Yugoslav military

leaders, the Yugoslav High Command vowed to resist a German invasion, and also agreed with its Greek counterparts to launch a joint offensive against the

Italians in Albania. The success of the latter action would free up considerable numbers of Greek troops (14 divisions) to confront the German invasion in northeastern Greece. Even then, the Yugoslav government did not believe that a German attack was imminent, and that it still had many months to

prepare, and was also confident in its military strength, as its army boasted one million troops, 200 tanks, and 600 planes. As it turned out during the war (previous article), Yugoslavia’s theoretical military capability was severely overpowered by the Germans in terms of firepower, technology, and tactics.

In the lead-up to the German invasion of Greece, British planners proposed to their Greek counterparts of setting up a shorter line of defense equivalent to their limited manpower and resources. As such a plan would require the Greek Army in Albania to relinquish its hard-won territories to the Italians, General

Papagos refused, stating that such a move would be devastating to Greek civilian and military morale. The British also saw that although the Metaxas Line in the northeast was sound against a frontal attack from Bulgaria, it could be outflanked through southern Yugoslavia, and that in any case, the strength of the combined British-Greek forces was insufficient to successfully hold the Metaxas Line. Only four Greek

divisions were assigned to defend the Line. In the Greek northeast, the idea of relinquishing the Metaxas Line was even more unacceptable to the Greeks, as Salonika, Greece’s second largest city, and the whole region of Western Thrace and Eastern

Macedonia, would be exposed to attack.

In the end, the British acquiesced to Greek sentiments, and established their own defensive line, called the Vermion Position, a forty-mile series of fortifications stretching along the slopes of the Olympus and Pieria Mountains to the Vermion Mountain range in the Yugoslav-Greek border. Manned by W Force as well as two Greek divisions, the Vermion Position was strategically situated in central Macedonia, and was aimed at sealing the northern frontier between the two main Greek formations in Albania and the Metaxas Line.

Invasion

On April 6, 1941, Germany launched Operation Marita, the invasion of Greece, with the German 12th Army in Bulgaria launching offensives into southern Yugoslavia, whose capture would achieve the strategic objective of cutting off the rest of Yugoslavia in the north with Greece in the south. In the northern sector, units of the German XL Panzer Corps advanced along two points: the 9th Panzer Division for Kumanovo and the 73rd Infantry Division for Stip.

Both met strong Yugoslav resistance, but they reached their objectives that same day. On April 7, the German 9th Panzer Division reached Skopje, and then Prilep the next day. On April 9, the Germans took Monastir. These thrusts cut the rail and road lines between Belgrade, Yugoslavia’s capital, and Salonika. More important, the Germans were now poised to invade Greece through the Monastir Gap.

Also on August 6, 1941, the Germans in western Bulgaria attacked from further south, with the

German 2nd Panzer Division entering southern Yugoslavia and advancing to Strumica, which it captured that same day. After breaking off a Yugoslav counter-attack, on April 7, the Germans turned south for the border and, passing through the mountainous frontier, crossed into Greece and then overwhelmed the Greek 19th Motorized Infantry Division south of Lake Doiran. Now unopposed, the Germans continued south and entered Salonika on April 9, 1941.

The German XVIII Mountain Corps crossed into Greece directly through the Metaxas Line. Here, strong Greek resistance, difficult terrain, and alpine weather conditions slowed the advance. But the Germans broke through at various points: the 6th Mountain Division through a 7,000-foot mountain that the Greeks had deemed impassable; the 5th Mountain Division at Neon Petritsi, and the 72nd Infantry Division from Nevrokop to Serres. Assaults on Greek fortifications along the Metaxas Line resulted in heavy casualties to the German 125th Infantry Regiment. The deeply entrenched Greek

fortifications were finally subdued only after intense German air and artillery bombardment. Greek forces then surrendered to the Germans, who disarmed and released the Greek soldiers. East of the Metaxas Line, the German XXX Infantry Corps invaded Western Thrace, seizing Greece’s easternmost region by April 9. By then, all regions east of the Vardar River, including Salonika, Eastern Macedonia, and Western Thrace, were in German hands.

April 26, 2020

April 26, 1937 – Spanish Civil War: German planes bomb Guernica

In March 1937, the Nationalist invasion of Biscay began, which was supported by the German Condor Legion carrying out bombing raids on Durango and Guernica. The attack on Guernica on April 26, 1937, which destroyed three-quarters of the town, shocked the international community and generated widespread condemnation against Germany. With Bilbao’s fall on June 19, Biscay Province came under

Nationalist control.

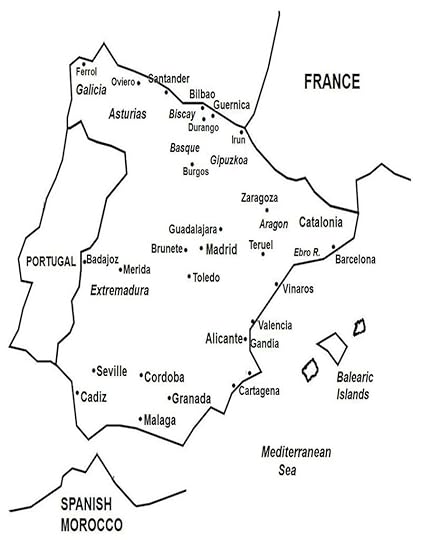

Key areas in the Spanish Civil War.

(Taken from Spanish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background

In January 1930, General Miguel Primo de Rivera, Spain’s military dictator, was forced to step down from office. His ambitious infrastructure programs and socio-economic reforms had failed, and the ongoing Great Depression was devastating Spain’s economy. Spain’s unpopular monarch, King Alfonso XIII, formed two governments in succession, but both collapsed after failing to calm the growing unrest among the Spanish people. Consequently, new elections were called.

In the past, Spain’s politics had been monopolized by the political elite belonging to the Conservative and Liberal parties. In Spain of the early twentieth century, however, the emergence of many factors, including industrialization, labor unions, radical ideologies, public discontent, anti-monarchical and anti-cleric sentiments, and separatist movements, were all converging to radically transform Spain’s

political climate.

In the municipal elections of April 1931, an

anti-monarchical political coalition of leftist republicans and socialists came to power and formed a republican government (called the Spanish Second

Republic**). The military regime ended and King Alfonso XIII was forced to step down and leave for exile abroad. Thus, the Spanish monarchy ended.

The now ruling political left blamed the Church and the monarchy for Spain’s many ills, including the socio-economic inequalities, loss of the empire’s vast

territories, and backwardness compared to other more industrialized European countries.

Then in general elections held in June 1931, leftist republicans and socialists again won a majority, this time for parliament, and thereafter convened the Cortes Generales (Spanish legislature). The new government, wanting to secularize the state, passed a new constitution in December 1931, which removed the Catholic Church’s pre-eminence over the country’s social and educational institutions. The new constitution promoted civil liberties and guaranteed free speech and the right to assembly, as well as universal suffrage, where women, for the first time, were allowed to vote.

The constitution also nationalized industries and began an agrarian reform program. The right to

regional self-determination was upheld; as a result, the regions of Basque and Catalonia, both hotbeds

of separatism, gained political autonomy. The libertarian atmosphere generated by the new regime encouraged violent anti-clericalism: starting in May 1931, many churches, monasteries, convents, and other religious buildings in Madrid and across Spain

were burned down, destroyed, or vandalized.

Spain’s traditional political elite, which constituted and defended the interests of the upper classes and the Catholic Church, looked on with great alarm, as the changes threatened to destroy long venerated Spanish institutions. In the countryside,

tensions rose between peasants and landowners, destabilizing the quasi-feudalistic agrarian system of the latifundia, i.e. the vast agricultural plantations owned by the small upper class. In August 1932, army officers, led by General Jose Sanjurjo, carried out an unsuccessful uprising because of his opposition to the government’s reforms in the military establishment.

Concerned by the rising instability, the government slowed down the peace of reforms, which then drew the indignation of labor unions and

peasant sector. The economic devastation caused by the ongoing Great Depression also eroded popular support for the regime. In general elections held in

November 1933, centrist and right-wing political parties emerged victorious. A center-right government was formed, which reversed or stalled the previous regime’s reforms. Then in October 1934 when the right-wing party CEDA (or Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas) put pressure on

the center-led coalition government that saw the appointment of CEDA into Cabinet positions, the Unión General de Trabajadores, a powerful workers’ union associated with the socialist party, launched a nationwide general strike. The strikes failed in most areas.

However, the strikes were successful (initially) in Catalonia, and more spectacularly carried out in Asturias. In the latter, in the event known as the

Asturias miners’ strike of 1934, thousands of miners took over many towns and villages, including Oviero, the provincial capital, where the Catholic cathedral and government buildings were burned down, and local officials and clergy were executed. Units of the

Spanish Army were called in, led by two commanders one of whom was General Francisco Franco. After two weeks of fighting, the revolt was crushed and thousands of workers were executed or imprisoned.

Consequently, military officers who were thought to be supportive of the government (i.e. right-wing) were promoted, including General Franco, who became commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Politically and socially, the country had become polarized into two opposite, mutually hostile forces: the left and the right. The left targeted rightist sectors: the church with executions and arson, employers with militant actions, and agricultural landowners with seizure of farmlands. In turn, the political right killed and jailed union leaders and left-leaning intellectuals and academics.

At this time, thousands of youths from right-wing and monarchist organizations joined the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista or simply Falange, a fascist party influenced by founding movements in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Many leftists also began to embrace more radical and violent ideas, including armed revolution.

In general elections held in February 1936, the Popular Front, a coalition of leftist republicans, socialists, and communists, emerged victorious, only edging out the combined right-wing and centrist votes but gaining a clear majority in parliament. The leftist victory came about in large part because of the electoral participation of the anarchists who, represented by the anarchist labor union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo or CNT, were infuriated by the right-wing government’s anti-anarchist policies. With the leftist electoral victory, a wave of lawlessness took place, as leftist elements forced the release of jailed political prisoners (without judicial proceedings) and peasants seized farmlands.

A leftist government was formed, which demoted or re-assigned military officers who were deemed to be right-wing; among these officers was General Franco, who was dismissed as commander-in-chief and transferred to the distant Canary Islands. Also affected by the restructuring was General Emilio Mola, who was transferred to the northern province of Navarre, a monarchist stronghold, from where he began to conspire with other officers in a plot to overthrow the government. The motivation for the plot was the perceived need to save the country from

self-destruction and/or communism. By early July, many military commands in Spain were ready to carry out the coup; General Franco wavered for some time before also opting in.

In the plan, Spain’s forces in Spanish Morocco would launch a revolt on July 17, to be followed by

the Spanish Army in the mainland the next day. Then on July 18, Spanish Moroccan Army would arrive in mainland Spain and together with the peninsular forces, would overthrow the government.

In Madrid on July 12, 1936, an Assault Guard police officer, who also belonged to the Socialist Party, was shot and killed by Falangists. The next day, Assault Guards arrested and killed Jose Calvo Sotelo, a monarchist politician and the leading right-wing

parliamentarian. Retaliatory killings followed these two incidents. Sotelo’s murder served as the tipping point for the military officers to launch the coup.

War

On July 17, 1936, Spain’s forces in Spanish Morocco declared in a radio broadcast a state of war against the central government in Madrid, an act of rebellion that opened the Spanish Civil War. These overseas forces, called the “Army of Africa”, were the Spanish Army’s strongest fighting units and consisted of the Spanish Legion and Moroccan regiments. The Army of Africa would contribute significantly to the outcome of the land operations in the coming war.

Earlier, local authorities in Spanish Morocco had learned of the plot. As a result, the rebels were

forced to move forward the uprising from the previously planned schedule of 5 AM on July 18. Shortly after the rebellion was broadcast, the Army of Africa gained control of Spanish Morocco, in the process also killing dozens of persons, including pro-government army officers and civilian leaders.

By this time, General Franco, who previously had commanded the Army of Africa and from whom he drew great respect, arrived from the Canary Islands (which also had risen up in rebellion) and took over-all command in Spanish Morocco. As agreed, the next

day, July 18, many military commands in mainland Spain also declared war; thus, a large-scale army rebellion was underway.

Many other military commands, however, did not revolt or were put down while doing so. The uprisings succeeded in the southwest and in a large swathe from the coastal northwest to northern central Spain, Spanish Morocco, the Canary Islands, and most of the Balearic Islands – in total, about one-third of thecountry.

April 25, 2020

April 25, 1974 – Carnation Revolution: A military coup in Portugal overthrows the authoritarian-conservative regime; a military junta is formed that begins the process of decolonization

On April 25, 1974, the Portuguese government of Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano was ousted in a military coup. A military junta formed a new government which made a sudden and dramatic shift in the course of the colonial wars. By July 1974, Portugal had begun the process of ending the colonial wars and granting independence to its African colonies.

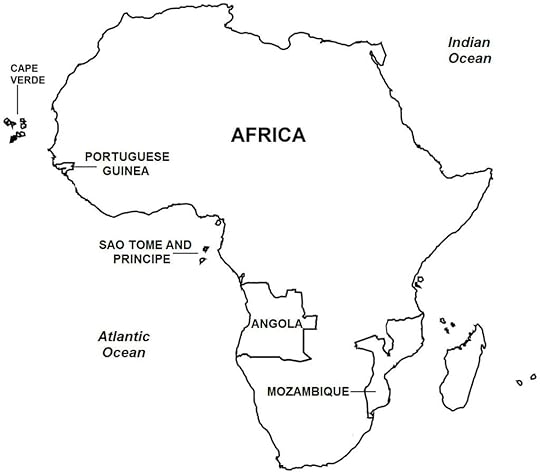

Portugal’s African possessions consisted of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese-Guinea, Cape Verde, and Sao Tome & Principe.

(Taken from Portuguese Colonial Wars – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

During the colonial era, Portugal’s territorial possessions in Africa consisted of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe. When World War II ended in 1945, a surge of nationalism swept across the various African colonies as independence groups emerged and demanded the end of European colonial rule. As these demands soon intensified into greater agitation and violence, most of the European colonizers relented, and by the 1960s, most of the African colonies had become independent countries.

Bucking the trend, Portugal was determined to hold onto its colonial possessions and went so far as to declare them “overseas provinces”, thereby formally incorporating them into the national territories of the motherland. Nearly all the black

African liberation movements in these Portuguese “provinces” turned their attention from trying to gain independence through negotiated settlement to

launching insurgencies, thereby starting revolutionary wars. These wars took place through the early 1960s

to the first half of the 1970s, and were known collectively as the Portuguese Colonial War, and pitted the Portuguese Armed Forces against the African guerilla militias in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea. At the war’s peak, some 150,000 Portuguese soldiers were deployed in Africa.

By the 1970s, these colonial wars had become extremely unpopular in Portugal, because of the mounting deaths in Portuguese soldiers, the irresolvable nature of the wars through military force, and the fact that the Portuguese government was using up to 40% of the national budget to the wars and thus impinging on the social and economic development of Portuguese society. Furthermore, the wars had isolated Portugal diplomatically, with the United Nations constantly putting pressure on the Portuguese government to decolonize, and most of the international community imposing a weapons embargo and other restrictions on Portugal. In April 1974, dissatisfied officers of the military carried out a coup that deposed the authoritarian regime of Prime

Minister Marcelo Caetano; the coup, known as the Carnation Revolution, produced a sudden and dramatic shift in the course of the colonial wars.

April 24, 2020

April 24, 1926 – Interwar period: Signing of the Treaty of Berlin, where Weimar Germany and the Soviet Union pledge neutrality in the event of attack on the other by a third party

Important to Germany’s secret rearmament was the Weimar government’s opening ties with the Soviet Union. Relations began in April 1922 with the

signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, which established diplomatic ties, and furthered in April 1926 with the Treaty of Berlin, where both sides agreed to remain neutral if the other was attacked by another country. In the aftermath of World War I, the Germans and Soviets saw the need to help each other, as they were outcasts in the international community: the Allies blamed Germany for starting the war, and also turned their backs on the Soviet Union for its communist ideology.

(Taken from Events Leading up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Aftermath of World War I

On November 18, 1918, fighting in World War I ended, with representatives from Germany and the Allied Powers signing an armistice. The war caused enormous political, economic, and social upheavals, and massive infrastructure destruction in many parts of Europe. Some 17 million people were killed and

another 20 million were wounded. Four great empires ceased to exist: the Russian Empire, German Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Ottoman Empire, and many new countries in Europe and the Middle East were formed from their former colonial holdings.

The victorious Allies signed separate peace treaties with the defeated Central Powers, including each with Austria, Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. But the most important was the Treaty of

Versailles, signed in June 1919, with their most powerful enemy, Germany. The terms of the Versailles treaty were dictated primarily by France,

and were meant to force Germany to make substantial payment for the extensive destruction caused by the war, and more important, to reduce German military power to a purely defensive role.

Among the treaty’s many provisions were German war reparations to the Allies; the confiscation of German colonial holdings in Africa and the Asia-Pacific; the stripping of Germany of 25,000 square miles (or 13%) of its homeland territory, which were ceded to France, Belgium, Italy, and newly formed countries Poland and Czechoslovakia; dissolution of the German general staff; demobilization of most of the German Army, leaving only 100,000 troops; marked reduction in the size of the German Navy; and prohibition on Germany of the possession, manufacture, purchase, and trade of aircraft, tanks, armored cars, heavy artillery, anti-tank weapons, submarines, and chemical weapons.

The Rhineland, located on Germany’s western border with France and Belgium, was occupied by the Allies, who were to make a phased withdrawal in 15 years, subject to German compliance with the Versailles treaty. Germany’s Saar region was placed under a League of Nations mandate also for 15 years,

with Saar coal production turned over to France as part of the reparations payment. The most controversial of the Versailles treaty’s provisions was the so-called “War Guilt” clause, where Germany (and its partners) was forced to admit to having caused the war, i.e. “to accept responsibility…and her allies for causing all the loss and damage” during the war. The Treaty of Versailles, especially the War Guilt clause, generated considerable outrage among Germans, and would contribute to the rise of the Nazi Party and be used by Hitler to justify German rearmament in the mid-1930s.

Weimar Republic

Near the end of World War I, Germany was beset by severe internal tumult, as industrial workers, including those involved in war production, launched strike actions that were fomented by communist political and labor groups that long opposed Germany’s involvement in the war. Then in late October-early November 1918 when German defeat in the war became imminent, German Navy sailors at the ports of Wilhelmshaven and Kiel mutinied, and refused to obey their commanders who had ordered them to prepare for one final decisive battle with the British Navy. Within a few days, the unrest had spread to many cities across Germany, sparking a full-blown

communist-led revolt (the German Revolution) that peaked in January 1919, when democracy-leaning forces quelled the uprising. But in the chaos following German defeat in World War I, the monarchy under Kaiser (King) Wilhelm II ended, and was replaced by a social democratic state, the Weimar Republic (named after the city of Weimar, where the new state’s constitution was drafted).

The Weimar Republic, which governed Germany from 1919-1933, was permanently beset by fierce political opposition and also experienced two failed coup d’états. A full spectrum of opposition political parties, from the moderate to radical right-wing, ultra-nationalist, and monarchist parties, to the moderate to extreme left-wing, socialist, and communist parties, wanted to put and end to the

Weimar Republic, either through elections or by paramilitary violence , and to be replaced by a political system suited to their respective ideologies. One radical political movement that emerged at this time was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which came to be known in the West as the Nazi Party, and its members called Nazis, and led by

Adolf Hitler. The Nazis participated in the electoral process, but wanted to end the Weimar democratic system. Hitler denounced the Versailles treaty, advocated totalitarianism, held racial views that extolled Germans as the “master race” and disparaged

other races, such as Slavs and Jews, as “sub-humans”. The Nazis also were vehemently anti-communist

and advocated lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism in Eastern Europe and Russia.

A common theme among right-wing, ultra-nationalist, and ex-military circles was the idea that in World War I, Germany was not defeated on the battlefield. Rather, German defeat was caused by traitors, notably the workers who went on strike at a critical stage of the war and thus deprived soldiers at the front lines of their much-needed supplies. As well, communists and socialists were to blame, since they fomented civilian unrest that led to the revolution; Jews, since they dominated the communist leadership; and the Weimar Republic since it signed the Versailles treaty. This concept, called the “stab in the back” theory, postulated that in 1918, Germany was on the brink of victory , but lost after being stabbed in the back by the “November criminals”, i.e. the communists, Jews, etc. After coming to power, the Nazis would appropriate the “stab in the back” theory to fit their political agenda in order to denounce the Versailles treaty, suppress opposition, and establish a dictatorship.

Germany, financially ravaged by the war, was hard pressed to meet its reparations obligations. The government printed enormous amounts of money to cover the deficit and also pay off its war debts, but this led to hyperinflation and astronomical prices of basic goods, sparking food riots and worsening the economy. Then when Germany defaulted on reparations in December 1922, French and Belgian forces occupied the Ruhr region, Germany’s industrial heartland, to force payment. At the urging of the Weimar government, Ruhr authorities and residents launched passive resistance; shop owners refused to sell goods to the foreign troops, and coal miners and railway employees did not work. Both Germany and France suffered financial losses as a result. Following United States intervention, in August 1924, the two sides agreed on the Dawes Plan , where German reparations payments were restructured, and the U.S.

and British government extended loans to help with Germany’s economic recovery. French troops then withdrew From the Ruhr region. Subsequently in August 1929, with the adoption of the Young Plan , Germany’s reparations obligations were reduced and payment was extended to a period of 58 years. As a result of these and other measures, including stronger fiscal control, introduction of a new currency, and easing bureaucratic hurdles, Germany’s economy recovered and expanded during the second half of the 1920s. Reparations were made, foreign investments entered the domestic market, and civil unrest declined.

The Versailles treaty was a heavy blow to the German national morale, and was seen as a humiliation to the Weimar state, which had been forced by the Allies to agree to it under threat of continuing the war. From the start, the Weimar government was determined to implement re-armament in violation of the Versailles treaty. Throughout its existence from 1919-1933, the Weimar Republic carried out small, clandestine, and subtle means to build its military forces, and was only restrained by the presence of Allied inspectors that regularly visited Germany to ensure compliance with the Versailles treaty. These methods included secretly reconstituting the German general staff, equipping and training the police for combat duties, and tolerating the presence of paramilitaries with an eye to later integrate them as reserve units in the regular army.

Also important to Germany’s secret rearmament was the Weimar government’s opening ties with the Soviet Union. Relations began in April 1922 with the

signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, which established diplomatic ties, and furthered in April 1926 with the Treaty of Berlin, where both sides agreed to remain neutral if the other was attacked by another country. In the aftermath of World War I, the Germans and Soviets saw the need to help each other, as they were outcasts in the international community: the Allies blamed Germany for starting the war, and also turned their backs on the Soviet Union for its communist ideology.

Military cooperation was an important component to German-Soviet relations. At the invitation of the Soviet government, Weimar Germany built several military facilities in the Soviet Union; e.g. an aircraft factory near Moscow, an artillery facility near Rostov, a flying school near Lipetsk, a chemical weapons plant in Samara, a naval base in Murmansk, etc. In this way, Germany achieved some rearmament away from Allied detection, while the Soviet Union, yet in the process of industrialization from an agricultural economy, gained access to German technology and military theory.

April 23, 2020

On April 23, 1982 – Falklands War: British forces recapture South Georgia Island

On April 19, 1982, the British task force reached the waters off the Falkland Islands. The first combat action took place in South Georgia Island, where a force of British Marines was landed, supported by British ships that shelled Argentinean coastal

positions. On April 23, 1982, the British recaptured the island.

On May 1, 1982, the British began their re-conquest of the Falklands, with their air force conducting bombing and strafing attacks on Port Stanley Airport. Argentinean planes flew to meet the British attacks. Some limited, inconclusive air battles

followed, where the two sides generally avoided flying inside their enemy’s best operating altitude.

In 1982, Argentina and Britain went to war for possession of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

(Taken from Falklands War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background

In early 1982, Argentina’s ruling military junta, led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, was facing a crisis of

confidence. Government corruption, human rights violations, and an economic recession had turned initial public support for the country’s military regime into widespread opposition. The pro-U.S. junta had come to power through a coup in 1976, and had crushed a leftist insurgency in the “Dirty War” by

using conventional warfare, as well as “dirty” methods, including summary executions and forced disappearances. As reports of military atrocities became known, the international community

exerted pressure on General Galtieri to implement reforms.

In its desire to regain the Argentinean people’s moral support and to continue in power, the military government conceived of a plan to invade the Falkland Islands, a British territory located about 700 kilometers east of the Argentine mainland. Argentina

had a long-standing historical claim to the Falklands,

which generated nationalistic sentiment among Argentineans. The Argentine government was determined to exploit that sentiment. Furthermore,

after weighing its chances for success, the junta concluded that the British government would not likely take action to protect the Falklands, as the

islands were small, barren, and too distant, being located three-quarters down the globe from Britain.

The Argentineans’ reasoning was not without merit. Britain under current Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was experiencing an economic recession, and in 1981, had made military cutbacks that would have seen the withdrawal from the Falklands of the HMS Endurance, an ice patrol vessel and the British Navy’s only permanent ship in the southern Atlantic

Ocean. Furthermore, Britain had not resisted when in 1976, Argentinean forces occupied the uninhabited Southern Thule, a group of small islands that forms a part of the British-owned South Sandwich Archipelago, located 1,500 kilometers east of the Falkland Islands.

In the sixteenth century, the Falkland Islands first came to European attention when they were signed by Portuguese ships. For three and a half

centuries thereafter, the islands became settled and controlled at various times by France, Spain, Britain,

the United States, and Argentina. In 1833, Britain

gained uninterrupted control of the islands, establishing a permanent presence there with settlers coming mainly from Wales and Scotland.

In 1816, Argentina gained its independence and, advancing its claim to being the successor state of the former Spanish Argentinean colony that had included “Islas Malvinas” (Argentina’s name for the Falkland Islands), the Argentinean government declared that the islands were part of Argentina’s territory. Argentina also challenged Britain’s account of the events of 1833, stating that the British Navy gained control of the islands by expelling the Argentinean civilian authority and residents already present in the Falklands. Over time, Argentineans perceived the British control of the Falklands as a misplaced vestige of the colonial past, producing successive generations of Argentineans instilled with anti-imperialist sentiments. For much of the twentieth century, however, Britain and Argentina

maintained a normal, even a healthy, relationship, although the Falklands issue remained a thorn on both sides.