Daniel Orr's Blog, page 96

June 1, 2020

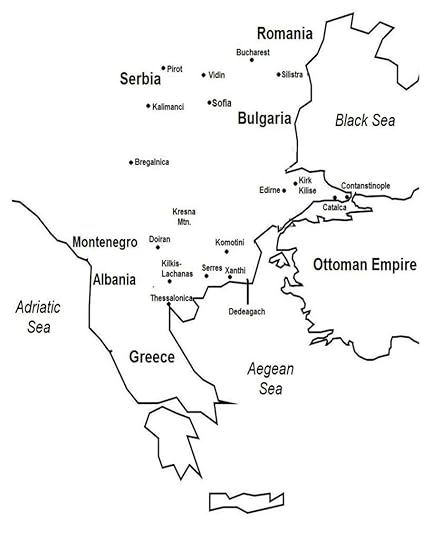

June 1, 1913 – Second Balkan War: Greece and Serbia sign a Treaty of Alliance against Bulgaria

On June 1, 1913, Serbia and Greece secretly signed a mutual defense treaty aimed at countering a potential attack by Bulgaria. The treaty came in the wake of the First Balkan War, where Bulgaria took issue with what it perceived was its small share in the partition of territories conquered from the Ottoman Empire during the war.

Background

The First Balkan War allowed the Balkan League (Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, and Montenegro) to gain control of nearly the whole region of the Ottoman region of Rumelia. In the 1913 Treaty of London, the major European powers recognized the independence of Albania, forcing Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro to withdraw their forces from their respective conquered territories in Albania. Before the war, Serbia and Bulgaria had entered into a secret agreement to partition Rumelia between them, in

particular the Macedonian region. No similar partition agreement was made with Greece, as the Greek Army was not highly regarded and thought to be incapable of gaining much territory.

During the war, however, Bulgaria had concentrated much of its military resources in Eastern Thrace aiming to capture Constantinople, and left a much smaller force to invade Macedonia. As a result, Bulgaria’s allies, Serbia and Greece, both of whom faced much less opposition in their sectors, gained considerable territory during the war. Serbian forces advanced into southern Macedonia past the so-called “disputed zone” north of the Kriva Palanka-Ohrid Line, which was part of the Serbian-Bulgarian pre-war partition agreement. The Greek Army also performed (surprisingly) well and seized a large section of southern Macedonia and portions of Western Thrace.

The Bulgarians applied pressure on Serbia to withdraw its forces to the north and beyond Monastir in compliance with their pre-war arrangement. Serbia

refused, as it already had been forced to relinquish northern Albania, while Bulgaria had ceded much less in Eastern Thrace, in the areas of the Enos-Midia Line. Serbia insisted that new negotiations be started

on partitioning Macedonia, a proposal that was rejected by Bulgaria. (In their pre-war agreement, Serbia was allowed to expand freely into Albania, while Bulgaria could take southern Macedonia.)

Bulgaria also put pressure on Greece to withdraw from Western Thrace and southern Macedonia, in particular from Thessalonica. The Greeks offered a compromise agreement, which the Bulgarians rejected.

Greek-Serbian Alliance of 1913

As Bulgaria continued its war posturing and increased its forces in the disputed areas, on June 1, 1913, Serbia and Greece secretly signed a mutual defense treaty aimed at countering a potential Bulgarian attack. The agreement also fixed a common border between Serbia and Greece. Consequently, small-scale fighting began to break out between Serbians and Bulgarians, whose forces were situated next to each other following the recently concluded First Balkan War. A small Montenegrin contingent also joined ranks with Serbian forces.

Meanwhile, Russia was alarmed at the impending break up of the Serbian-Bulgarian alliance, as this threatened Russia’s power ambitions in the Balkan region. Tsar Nicholas II, the Russian monarch, offered to mediate, even sending a personal letter to both the Serbian and Bulgarian kings. Bulgaria was unyielding, however, forcing the Russian government to cancel the Russo-Bulgarian Treaty of 1902.

Second Balkan War

On June 29, 1913, less than a month after the First Balkan War ended, Bulgaria, without declaring war, launched simultaneous attacks against Serbian and Greek forces in Macedonia. The Second Balkan War had begun.

May 31, 2020

May 31, 1916 – World War I: British and German fleets clash at the Battle of Jutland

On May 31, 1916, the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet clashed at the Battle of Jutland, located off Denmark’s North Sea coast. Both sides failed to achieve a decisive victory.

During World War I, Britain imposed a naval blockade of the German coast. The German Navy, being much smaller than the British Royal Navy, could not engage the latter in full-scale combat. Instead, at Jutland, the German plan was to lure, trap, and destroy a portion of the British fleet.

The Battle of Jutland involved some 250 ships and 100,000 men, and was the only major naval surface encounter during World War I. Both sides claimed victory. The British lost more ships and men, and the British press criticized its navy for failing to achieve a decisive outcome. However, the battle was a strategic British victory, since the Royal Navy had forced the German surface fleet to retire to Germany, where it would remain as a “fleet in being”, unwilling to leave port to do battle but persisting as a latent threat. Britain continued to control the North Sea and Germany was denied access to the Atlantic and British shipping lanes. In 1917, the German Navy turned to its U-boats to launch unrestricted submarine warfare aimed at destroying Allied and neutral shipping.

May 30, 2020

May 30, 1913 – First Balkan War: Albania gains its independence

On May 30, 1913, Albania gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire with the signing of the Treaty of London that ended the First Balkan War (October 1912-May 1913). Albania’s sovereignty was reaffirmed in August 1913 in the Treaty of Bucharest that delineated the boundaries of the new state, but which left 30-40% of ethnic Albanians outside its borders.

The First Balkan War was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Balkan League, a military alliance involving Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Greece, for control of Rumelia, a broad swathe of Ottoman territory in the Balkans. The Treaty of London, signed on May 30, 1913, officially ended the war. The European powers (Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Russia) applied strong diplomatic pressure and forced the warring sides to accept the terms of the agreement. The treaty’s most important provision compelled the Ottoman Empire to cede to the Balkan League all European territory west of the Enos-Midia Line.

The Ottoman government acquiesced and withdrew its forces from the Balkans, thus ending nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule. After further deliberations and under the strong insistence of Austria-Hungary and Italy, on July 29, 1913, the European powers agreed to recognize the independence of Albania, where local Albanian nationalists had previously (on November 28, 1912) declared the province’s secession from the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro withdrew their forces from occupied areas in Albania, again after being strong-armed diplomatically by the European powers.

The partitioning of other Balkan territories was left to the discretion of the Balkan League. Nevertheless, the unexpected birth of the Albanian state disrupted the Serbian-Bulgarian pre-war secret partition agreement of the Balkan region. In particular, Bulgaria was disappointed at its less than expected territorial gains in the war, more so in relation to Greece whose forces had performed exceedingly (and surprisingly) well, and had

gained a larger share of the conquered territories in southern Macedonia that otherwise would have been won by Bulgaria. For this reason, Bulgaria put pressure on Serbia and Greece to turn over some of the conquered territories, which the latter two refused.

The stage thus was set for the resumption of hostilities, the Second Balkan War.

May 29, 2020

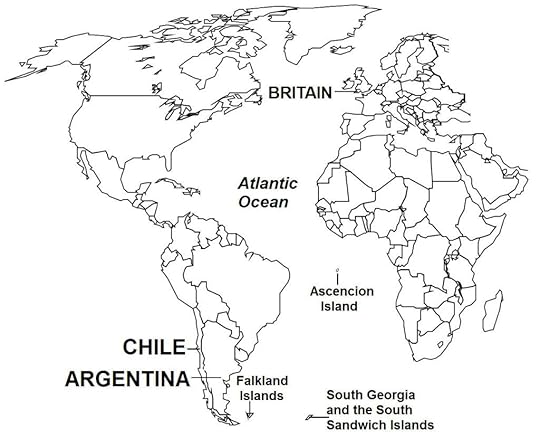

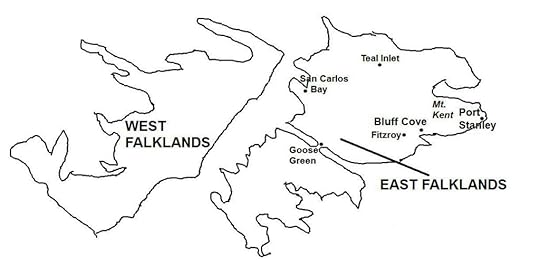

May 29, 1982 –Falklands War: British forces recapture Goose Green

Background

On May 21, 1982, some 4,000 British Marines landed at San Carlos Bay. After easily overpowering the small Argentine garrison, the British soldiers secured the landing zone, where British transport ships soon arrived to unload weapons and supplies. The Argentineans carried out many air attacks, sinking the British frigates HMS Ardent and HMS Antelope on May 21 and May 24, respectively, and the destroyer HMS Coventry on May 25. Also badly damaged were the British frigates HMS Argonaut and HMS Brilliant. Many other ships also could have been hit or suffered heavy damage were it not that Argentinean pilots often released their rockets too low, which exploded with little effect or did not detonate on time.

The British incurred heavy losses at San Carlos Bay, but succeeded in completing the landings.

However, the loss of a freighter carrying the transport helicopters for the troops meant that the British ground forces at San Carlos Bay could not be airlifted to Port Stanley as planned, but would have to walk the 80 kilometers of open terrain in bad weather to the capital. The main force of 3,000 troops was tasked to advance to Port Stanley.

To protect the flank of this advance, some 600 soldiers were sent to capture Goose Green, a village located southwest of San Carlos Bay. British reconnaissance flights indicated that Goose Green was defended only by a small Argentinean force. The British also noted the presence of artillery batteries and other heavy weapons. Unbeknown to the British, Goose Green’s garrison contained 1,200 soldiers, which outnumbered the British force by a ratio of 2:1. The Argentineans also were positioned on a

ridge facing the direction of the British advance.

Battle

The battle for Goose Green began on the night of May 27, 1982 with the British soldiers being pinned down by heavy fire. The following morning, the British successfully outflanked the ridge and advanced toward Goose Green. British planes struck at Argentinean positions, which began to break down. The British ground force then demanded the Argentineans to surrender. Believing he was facing a

large force, the Argentinean commander surrendered, and Goose Greece came under British control. Goose Green became a great morale boost to British forces in the Falklands as well as to the British general public in the homeland.

With their flank secure, the main British force at San Carlos Bay set out for Teal Inlet, located 40 kilometers northwest from Port Stanley. Excerpts taken from The Falklands War.

May 28, 2020

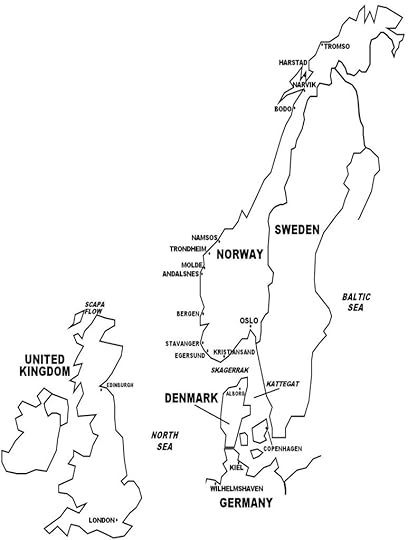

May 28, 1940 – World War II: Allied forces recapture Narvik in northern Norway

On May 28, 1940, Allied forces (Norwegian, French, Polish and British) captured Narvik in northern Norway, with the Germans fleeing toward the Swedish border. The German commander considered crossing into Sweden, where his forces would be interned by the Swedish Army.

Battle of Norway

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

By then however, Narvik and Norway as a whole had become inconsequential to the Allies because of the dire events now taking place in France. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded France, and two days later, German forces made a stunning advance through the Ardennes that led to the rapid collapse of Allied resistance and the forced evacuation in Dunkirk of the British Expeditionary Force, as well as some French units, to Britain in late May 1940. By the time the Allies captured Narvik, France was fighting for its own survival, and Britain was gearing up for the defense of the homeland.

On May 24, the Allied High Command decided to evacuate its forces from northern Norway, and the order for its implementation was sent to the Allied command in Norway, with instructions to carry out the attack on Narvik as a cover for the Allied withdrawal. On June 7-8, 1940 under Operation Alphabet, British, French, and Polish forces were evacuated from Norway for Britain, together with King Haakon VII, the royal family, and Norwegian Cabinet.

Background

The Allied objective in Narvik was to stop the Germans from capturing the whole of Norway.

The Allies had also made landings in central Norway, but these were turned back. By the time of the Narvik landings, the Germans had captured the whole of southern Norway, including the capital Oslo, as well as other key sites including Bergen, Kristiansand,

and Egersund in the south and Trondheim in central Norway. With the Allied withdrawal from Narvik, the whole of Norway came under German control.

May 27, 2020

May 27, 1905 – Russo-Japanese War: The start of the Battle of Tsushima

On May 27, 1905, the Japanese Navy engaged the Russian Second Pacific fleet in the two-day Battle of Tsushima (May 27-28, 1905). In the aftermath, the Russian fleet was annihilated, with 10,000 Russian sailors killed or captured, 21 ships sunk, including 7 battleships, and of the 38 Russian ships that started the voyage, only 3 managed to reach Vladivostok. Japanese losses were 700 dead or wounded, and only 3 torpedo boats sunk.

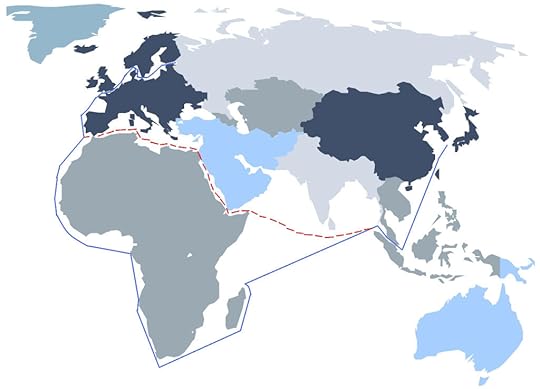

Route taken by the Russian fleet from the Baltic Sea to the Far East

Background

By March 1905, Japanese forces had gained control of the entire southern Manchuria, including Port Arthur, the strong Russian outpost. But they had

failed to annihilate the Russian Army (which remained relatively potent despite the high losses). Because of serious logistical problems, the Japanese Army decided to abandon plans to advance further north.

Despite the series of battlefield defeats, Tsar Nicholas II continued to believe that the Russian Army would prevail eventually in a protracted war. The now completed Trans-Siberian Railway could transfer more troops and weapons to the Far East. But these hopes would be dashed in the Battle of Tsushima.

In October 1904, while the Japanese Third Army was yet besieging Port Arthur, Tsar Nicholas II ordered the Russian Baltic Fleet, which was led by eight battleships, to head for Port Arthur and break the Japanese naval blockade, and reinforce the Russian Pacific Fleet. The Russian Baltic Fleet, soon renamed the Second Pacific Fleet, then embarked on a seven-month (October 1904-May 1905) 33,000-kilometer voyage half-way around the world by way of the Cape of Good Hope, and around the southern tip of Africa. The Russian fleet was forced to take this

much longer route after being denied passage across the Suez Canal by Britain following the Dogger

Bank incident. In this incident, which occurred in the North Sea in October 1904, the Russian fleet fired on British trawlers, mistaking them for Japanese torpedo boats. The incident sparked a furious British government protest that nearly led to war between Britain and Russia.

In January 1905, while yet in transit, the Russian fleet received information that Port Arthur had fallen. As a result, it was instructed to head for Vladivostok instead. By May 1905, the Russian fleet had entered

the waters south of the Sea of Japan, and while traversing the Tsushima Strait, located between Japan and Korea, the fleet was spotted by a Japanese ship, which then alerted the Japanese Navy. In the previous months, the Japanese had followed the progress of the Russian fleet’s voyage, and thus

prepared to do battle with it in a decisive showdown.

The Battle of Tsushima sent reverberations around the World – an Asian nation dealing a crushing defeat on a European power. In Russia, Tsar Nicholas II abandoned his hard-line position against Japan. On June 8, 1905, one week after the Tsushima battle, Russia agreed to negotiate an end to the war. (Excepts taken from the Russo-Japanese War).

May 26, 2020

May 26, 1900 – Thousand Days’ War: Colombia’s Conservative forces defeat Liberal militias at the Second Battle of Palonegro

The rivalry between Colombia’s Conservative and Liberal political parties lies at the heart of the Thousand Days’ War, which took place from 1899 to 1902. Colombia was a democracy and elections were held to decide between Conservatives, who advocated a strong centralized government and greater union between church and state; and Liberals, who favored a decentralized national government and separation of church and state. Colombia’s politics were bitter and violent, however, and coups, assassinations, and even civil wars, often broke out. Ethnicity and social class also factored in the discord, as Conservatives were led by the Spanish-descended

elite and wealthy landowners, while Liberals consisted of Spanish-Amerindian mestizos and were backed by middle-class merchants, traders, and smaller landowners. Peasants, who formed the vast majority of Colombian society, supported either one of the two parties.

Thousand Days’ War

In 1866, the ruling Conservative government passed a new constitution that advocated a centralized government and greater union between

church and state. The constitution had been a joint effort by Conservatives and Liberals. Later, however, some Liberals asserted that some of the charter’s provisions were unfair and needed to be amended. As a result, two Liberal uprisings broke out in 1893 and 1895, both of which were quelled.

In 1899, Colombia again was on the verge of a conflict, caused by economic and political factors. World coffee prices had plummeted, hitting hard local coffee growers who were ready to break out in revolt. The Liberals also were set to take up arms after being defeated in the previous year’s elections to the Conservatives whom they accused of cheating.

Fighting broke out in Santander Province, where the Liberals had assembled their militia to face the much larger Conservative forces. At the First Battle

of Palonegro, fought in November 1899, Conservative forces prevailed. However, they were turned back by the Liberals at Peralonso the following month, setting the stage for a decisive battle. In May 1900, Conservative forces inflicted a crushing defeat on the Liberals in the Second Battle of Palonegro. Left with insufficient forces to continue fighting conventional battles, the Liberals retreated to the

hinterlands and formed small groups to begin a guerilla war.

Toward the end of 1902, representatives from the two sides met in a series of dialogues, which led to the signing of a peace treaty that ended the war. Some 100,000 people were killed in the war. (Extracts for this write-up were taken from here. )

Panama’s Secession

At the time of the war, Panama was a “departamento” (province) of Colombia. Rebel activity was prevalent in Panama, with the insurgents even attempting to

seize the Panama Railway, a U.S. facility. As a result, the United States sent troops to protect the installation. In November 1903, or a year after the war had ended, Panama seceded from Colombia, forming its own independent state. The secession had been preceded by an uprising that was openly supported by the United States. Colombia, still reeling from the Thousand Days’ War, was unable to prevent the secession.

May 25, 2020

May 25, 1938 – Spanish Civil War: Italian planes bomb Alicante, killing over 300 civilians

On May 25, 1938, the Spanish city of Alicante was bombed by Italian planes (belonging to the Aviazione Legionaria) during the Spanish Civil War. Over 300 people were killed, while another 1,000 were injured.

Key areas during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) pitted government forces called “Republicans” against rebel forces called “Nationalists.” The Republicans were supported by unions, communists, anarchists, workers, and peasants, while the Nationalists were backed by the bourgeoisie, landlords, and the upper class. In the wider European context just before the outbreak of World War II, the Republicans were supported by the Soviet Union and European democracies, while the Nationalists were backed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

Alicante was a Republican stronghold and was bombed many times during the war. General Francisco Franco, leader of the Nationalists, envisioned that the Alicante bombing on May 25, 1938 would eliminate the Republicans’ maritime commerce and destroy morale.

The aerial attack on Alicante coincided with similar indiscriminate bombings on Valencia, Barcelona, Granollers and other Republican-held towns and cities, which were carried out by the Aviazione Legionaria and the German Legion Condor.

Background of the Spanish Civil War (Excerpts taken from here.)

In January 1930, General Miguel Primo de Rivera, Spain’s military dictator, was forced to step down from office. His ambitious infrastructure programs and socio-economic reforms had failed, and the ongoing Great Depression was devastating Spain’s economy. Spain’s unpopular monarch, King Alfonso XIII, formed two governments in succession, but both collapsed after failing to calm the growing unrest among the Spanish people. Consequently, new elections were called.

In the past, Spain’s politics had been monopolized by the political elite belonging to the Conservative and Liberal parties. In Spain of the early twentieth century, however, the emergence of many factors,

including industrialization, labor unions, radical ideologies, public discontent, anti-monarchical and anti-cleric sentiments, and separatist movements, were all converging to radically transform Spain’s political climate.

In the municipal elections of April 1931, an

anti-monarchical political coalition of leftist republicans and socialists came to power and formed a republican government (called the Spanish Second

Republic**).

The military regime ended and King Alfonso XIII was forced to step down and leave for exile abroad. Thus, the Spanish monarchy ended.

The now ruling political left blamed the Church and the monarchy for Spain’s many ills, including the socio-economic inequalities, loss of the empire’s vast

territories, and backwardness compared to other more industrialized European countries.

Then in general elections held in June 1931,

leftist republicans and socialists again won a majority, this time for parliament, and thereafter convened the Cortes Generales (Spanish legislature). The new government, wanting to secularize the state, passed a new constitution in December 1931, which removed the Catholic Church’s pre-eminence over the country’s social and educational institutions. The new constitution promoted civil liberties and guaranteed free speech and the right to assembly, as well as universal suffrage, where women, for the first time, were allowed to vote.

The constitution also nationalized industries and began an agrarian reform program. The right to regional self-determination was upheld; as a result, the regions of Basque and Catalonia, both hotbeds of separatism, gained political autonomy. The libertarian atmosphere generated by the new regime encouraged violent anti-clericalism: starting in May 1931, many churches, monasteries, convents, and other religious buildings in Madrid and across Spain

were burned down, destroyed, or vandalized.

Spain’s traditional political elite, which constituted and defended the interests of the upper classes and the Catholic Church, looked on with great alarm, as the changes threatened to destroy long

venerated Spanish institutions. In the countryside, tensions rose between peasants and landowners, destabilizing the quasi-feudalistic agrarian system of the latifundia, i.e. the vast agricultural plantations owned by the small upper class. In August 1932, army officers, led by General Jose Sanjurjo, carried out an unsuccessful uprising because of his opposition to the government’s reforms in the military establishment.

Concerned by the rising instability, the government slowed down the pace of reforms, which then drew the indignation of labor unions and peasant sector. The economic devastation caused by the ongoing Great Depression also eroded popular support for the regime. In general elections held in November 1933, centrist and right-wing political parties emerged victorious. A center-right government was formed, which reversed or stalled the previous regime’s reforms. Then in October 1934 when the right-wing party CEDA (or Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas) put pressure on the center-led coalition government that saw the appointment of CEDA into Cabinet positions, the Unión General de Trabajadores, a powerful workers’ union associated with the socialist party, launched a nationwide general strike. The strikes failed in most areas.

However, the strikes were successful (initially) in Catalonia, and more spectacularly carried out in Asturias. In the latter, in the event known as the

Asturias miners’ strike of 1934, thousands of miners took over many towns and villages, including Oviero, the provincial capital, where the Catholic cathedral and government buildings were burned down, and local officials and clergy were executed. Units of the Spanish Army were called in, led by two commanders one of whom was General Francisco Franco. After two weeks of fighting, the revolt was crushed and thousands of workers were executed or imprisoned.

Consequently, military officers who were thought to be supportive of the government (i.e. right-wing) were promoted, including General Franco, who became commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Politically and socially, the country had become polarized into two opposite, mutually hostile forces: the left and the right. The left targeted rightist sectors: the church with executions and arson, employers with militant actions, and agricultural landowners with seizure of farmlands. In turn, the political right killed and jailed union leaders and left-leaning intellectuals and academics.

At this time, thousands of youths from right-wing and monarchist organizations joined the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista or simply Falange, a fascist party influenced by founding movements in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Many leftists also began to embrace more radical and violent ideas, including armed revolution.

In general elections held in February 1936, the Popular Front, a coalition of leftist republicans, socialists, and communists, emerged victorious, only edging out the combined right-wing and centrist votes but gaining a clear majority in parliament. The leftist victory came about in large part because of the electoral participation of the anarchists who, represented by the anarchist labor union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo or CNT, were infuriated by the right-wing government’s anti-anarchist policies. With the leftist electoral victory, a wave of lawlessness took place, as leftist elements forced the release of jailed political prisoners (without judicial proceedings) and peasants seized farmlands.

A leftist government was formed, which demoted

or re-assigned military officers who were deemed to be right-wing; among these officers was General Franco, who was dismissed as commander-in-chief and transferred to the distant Canary Islands. Also affected by the restructuring was General Emilio Mola, who was transferred to the northern province

of Navarre, a monarchist stronghold, from where he began to conspire with other officers in a plot to overthrow the government. The motivation for the plot was the perceived need to save the country from

self-destruction and/or communism. By early July, many military commands in Spain were ready to carry out the coup; General Franco wavered for some time before also opting in.

In the plan, Spain’s forces in Spanish Morocco would launch a revolt on July 17, to be followed by the Spanish Army in the mainland the next day. Then on July 18, Spanish Moroccan Army would arrive in mainland Spain and together with the peninsular forces, would overthrow the government.

In Madrid on July 12, 1936, an Assault Guard police officer, who also belonged to the Socialist Party, was shot and killed by Falangists. The next day, Assault Guards arrested and killed Jose Calvo Sotelo, a monarchist politician and the leading right-wing

parliamentarian. Retaliatory killings followed these two incidents. Sotelo’s murder served as the tipping point for the military officers to launch the

coup.

** The First Spanish Republic existed between February 1873 to December 1874 after the Spanish monarch, King Amadeo I, abdicated; the republic ended with the proclamation of King Alfonso XII.

May 24, 2020

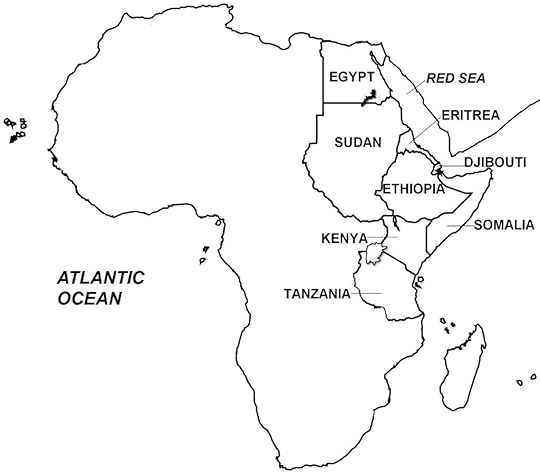

May 24, 1991 – Eritrean War of Independence: Eritrea gains its independence from Ethiopia

On May 24, 1991, Eritrea gained its independence from Ethiopia following a 30-year armed revolution. Ethiopia had annexed Eritrea

as a province in November 1962, inciting Eritrean nationalists to launch a rebellion.

Following the war, as Eritrea was still legally bound as part of Ethiopia, in early July 1991, at a conference held in Addis Ababa, an interim Ethiopian government was formed, which stated that Eritreans had the right to determine their own political future, i.e. to remain with or secede from Ethiopia.

Then in a UN-monitored referendum held in April 23 and 25, 1993, Eritreans voted overwhelmingly (99.8%) for independence; two days later (April 27), Eritrea declared its independence. In May 1993, the new country was admitted as a member of the UN.

(Excerpts taken from Eritrean War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

In September 1948, a special body called the Inquiry Commission, which was set up by the Allied Powers (Britain, France, Soviet Union, and United States), failed to establish a future course for Eritrea and referred the matter to the United Nations (UN). The main obstacle to granting Eritrea its independence was that for much of its history, Eritrea was not a single political sovereign entity but had been a part of and subordinate to a greater colonial power, and as such, was deemed incapable of surviving on its own as a fully independent state. Furthermore, various countries put forth competing claims to Eritrea. Italy wanted Eritrea returned, to be governed for a pre-set period until the territory’s independence, an arrangement that was similar to that of Italian Somaliland. The Arab countries of the Middle East pressed for self-determination of Eritrea’s large Muslim population, and as such, called for Eritrea to be granted its independence. Britain, as the current administrative power, wanted to partition Eritrea, with the Christian-population regions to be incorporated into Ethiopia and the Muslim regions to be assimilated into Sudan. Emperor Haile Selassie, the Ethiopian monarch, also claimed ownership of Eritrea, citing historical and cultural ties, as well as the need for Ethiopia to have access to the sea through the Red Sea (Ethiopia had been landlocked after Italy established Eritrea).

Ultimately, the United States influenced the future course for Eritrea. The U.S. government saw Eritrea in the regional balance of power in Cold War politics: an independent but weak Eritrea could potentially fall to communist (Soviet) domination, which would destabilize the vital oil-rich Middle East.

Unbeknown to the general public at the time, a U.S. diplomatic cable from Ethiopia to the U.S. State Department in August 1949 stated that British officials in Eritrea believed that as much as 75% of the local population desired independence.

In February 1950, a UN commission sent to Eritrea to determine the local people’s political aspirations submitted its findings to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In December 1950, the UNGA, which was strongly influenced by U.S. wishes, released Resolution 390A (V) that

called for establishing a loose federation between Ethiopia and Eritrea to be facilitated by Britain and to be realized no later than September 15, 1952. The UN plan, which subsequently was implemented, allowed Eritrea broad autonomy in controlling its internal affairs, including local administrative, police, and fiscal and taxation functions. The Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation would affirm the sovereignty of the Ethiopian monarch whose government would exert jurisdiction over Eritrea’s foreign affairs, including military defense, national finance, and

transportation.

In March 1952, under British initiative, Eritrea elected a 68-seat Representative Assembly, a legislature composed equally of Christians and Muslim members, which subsequently adopted a constitution proposed by the UN. Just days before the September 1952 deadline for federation, the Ethiopian government ratified the Eritrean constitution and upheld Eritrea’s Representative Assembly as the renamed Eritrean Assembly. On September 15, 1952, the Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation was established, and Britain turned over administration to the new authorities, and withdrew from Eritrea.

However, Emperor Haile Selassie was determined to bring Eritrea under Ethiopia’s full authority. Eritrea’s head of government (called Chief Executive who was elected by the Eritrean Assembly) was forced to resign, and successors to the post were appointed by the Ethiopian emperor. Ethiopians were appointed to many high-level Eritrean government posts. Many Eritrean political parties were banned and press censorship was imposed. Amharic, Ethiopia’s official language, was imposed, while Arabic and Tigrayan, Eritrea’s main languages, were replaced with Amharic as the medium for education. Many local businesses were moved to Ethiopia, while local tax revenues were sent to Ethiopia. By the early 1960s, Eritrea’s autonomy status virtually had ceased to exist. In November 1962, the Eritrean Assembly, under strong pressure from Emperor Haile Selassie, dissolved the Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation and voted to incorporate Eritrea as Ethiopia’s 14th province.

Eritreans were outraged by these developments. Civilian dissent in the form of rallies and demonstrations broke out, and was dealt with harshly by Ethiopia, causing scores of deaths and injuries among protesters in confrontations with security forces. Opposition leaders, particularly those calling for independence, were suppressed, forcing many to

flee into exile abroad; scores of their supporters also were jailed. In April 1958, the first organized resistance to Ethiopian rule emerged with the formation of the clandestine Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM), consisting originally of Eritrean exiles in Sudan. At its peak in Eritrea, the ELM had some 40,000 members who organized in cells of 7 people and carried out a campaign of destabilization, including engaging in some militant actions such as

assassinating government officials, aimed at forcing the Ethiopian government to reverse some of its centralizing policies that were undercutting Eritrea’s

autonomous status under the federated arrangement with Ethiopia. By 1962, the government’s anti-dissident campaigns had weakened the ELM, although the militant group continued to exist,

albeit with limited success. Also by 1962, another Eritrean nationalist organization, the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), had emerged, having been organized in July 1960 by Eritrean exiles in Cairo, Egypt which in contrast to the ELM, had as its objective the use of armed force to achieve Eritrean’s independence. In its early years, the ELF leadership, called the “Supreme Council”, operated out of Cairo

to more effectively spread its political goals to the international community and to lobby and secure military support from foreign donors.

May 23, 2020

May 23, 1945 – World War II: Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, commits suicide

On May 23, 1945, Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer (Reich Leader) of the Schutzstaffel (SS; Protection Squadron), while in Allied custody, committed suicide by biting into a cyanide pill in his mouth.

Himmler was a main architect of the Holocaust, and set up and controlled the Nazi concentration camps. He was both Chief of German Police and Minister of the Interior, overseeing all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo (Secret State Police). As facilitator and overseer of the concentration camps, Himmler directed the killing of some six million Jews, between 200,000 and 500,000 Romani people, and other victims; the total number of civilians killed by the Nazi regime is estimated at 11 – 14 million people.

By April 1945, realizing the war was lost, Himmler tried to open peace talks with the Western Allies without Hitler’s knowledge shortly before the end of the war. Upon learning of this, Hitler dismissed him from all his posts and ordered his arrest. Himmler attempted to go into hiding, but was detained and arrested by British forces once his identity became known. While in British custody, he committed suicide on May 23, 1945.

By the time of his death, World War II was officially over. Admiral Karl Doenitz, head of the German Navy and Hitler’s successor, had surrendered Germany in instruments signed on May 7 and May 8, 1945. The scattered German units across Europe surrendered before and after the official surrender dates.

Apart from Hitler (who committed suicide on April 30, 1945) as well as Himmler, other high-ranking Nazi officials who took their own lives were Joseph Goebbels (Minister of Propaganda) and his wife after poisoning their six children with cyanide, on May 1, 1945; Martin Bormann, Secretary to the Fuhrer and chief of the Nazi Party Head Office, determined to have already died perhaps by suicide, on May 2, 1945; and Hermann Goering, Vice-Chancellor and head of the Luftwaffe, on the night before his execution, on October 15, 1946.

Hermann Hess, former Deputy Fuhrer, also committed suicide by hanging while serving life sentence in Spandau Prison in August 1987. He was 93 years old, and speculation arose that he was murdered, pointing to his advanced age, that he could not have been physically capable of hanging himself.