Daniel Orr's Blog, page 92

July 11, 2020

July 11, 1940 – World War II: Philippe Petain becomes head of the French government

On July 11, 1940, with the imminent defeat of France to Germany in World War II, Marshall Philippe Petain was appointed head of the French government. The 84-year old Petain was a revered World War I hero who had led the Allies to victory at the Battle of Verdun, for which he became known as “The Lion of Verdun”.

Upon his appointment, Petain presided over the renamed “French State”, which collaborated with the Axis Powers during World War II. After the war, he was tried and convicted for treason . He was sentenced to death, which was commuted to life imprisonment because of his advanced age. He holds the distinction of being France’s oldest head of state.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Aftermath of the Battle of France Despite Germany’s overwhelming military position at the end of hostilities, the armistice negotiations were conducted with consideration of other realities: for Hitler, that the French government and army could very well move to French colonies in North Africa from where they could continue the war; and for the French government, that it wanted to remain in France but only if the Germans did not impose “dishonorable or excessive” terms. Terms that were deemed unacceptable included the following: that all of France would be occupied, that France should surrender its navy, or that France should relinquish its (vast) colonial territories.

Not only did Hitler not impose these terms, in fact, he

desired that France remain a sovereign state for diplomatic and practical

reasons: in the first case, France had ostensibly switched sides in the war,

isolating Britain; and in the second case, France, with its large navy, would

maintain its global colonial empire, which Germany could not because it did not

have enough ships.

Thus, in the armistice agreement, France

was allowed to remain a fully sovereign state, with its mainland territory and

colonial possessions intact, with some exceptions: Alsace-Lorraine became part

of the Greater German Reich, although not formally annexed into Germany; and Nord and Pas-de-Calais were

attached to Belgium in the

“German Military Administration of Belgium and Northern

France”. France also retained its navy, but

which was demobilized and disarmed, as were the other branches of the French

armed forces.

Because of the continuing hostilities with Britain, as part of the armistice agreement, the

German Army occupied the northern and western sections of France (some 55% of the French

mainland), where it imposed military rule.

The occupation was intended to be temporary until such time that Germany had defeated or had come to terms with Britain,

which both the French and German governments believed was imminent. The Italian military also occupied a small

area in the French Alps. In the rest of

France (comprising 45% of the French mainland), which was not occupied and thus

called zone libre (“free zone”), on July 10, 1940, the French government formed

a new polity called the “French State” (French: État français), which dissolved

the French Third Republic, and was led by Petain as Chief of State.

The “French State” had its capital at Vichy,

some 220 miles south of Paris, and was commonly

known as “Vichy France”. Officially, Vichy

France retained sovereignty

over all France,

but in reality, it exercised little authority in the occupied zones. Vichy France did have full administrative

power in zone libre, and in the ongoing war, it maintained a policy of

neutrality (e.g. it did not join the Axis), and was internationally recognized,

and maintained diplomatic relations with the United States, Canada, the Soviet

Union, even Britain, and many neutral countries.

The Vichy government imposed

authoritarian rule, with Petain holding broad powers, which was a full

turn-around and rejection of the liberalism and democratic ideals of the French Third

Republic. Using Révolution nationale (“National Revolution”)

as its official ideology, the Petain regime turned inward-looking (la France seule, or “France alone”), was deeply

conservative and traditionalist, and rejected liberal and modernist ideas. Traditional culture and religion were

promoted as the means for the regeneration of France. The separation of Church and State was

abolished, with Catholics playing a major role in affairs, the French Third

Republic was reviled as morally decadent and causing France’s military defeat,

and anti-Semitism and xenophobia predominated, with Jews and other

“undesirables”, including immigrants, gypsies, and homosexuals being

persecuted. Communists and left-wingers,

and other radicals were included in this category following the German invasion

of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Xenophobia was particularly directed against Britain, with Petain and other leaders

expressing strong antipathy with the British, calling them France’s “hereditary” and lasting

enemy.

The Vichy regime was

challenged by General Charles de Gaulle, who in June 1940 in Britain, formed a

government-in-exile called Free France, and an army, the Free French

Forces. De Gaulle criticized Vichy France

as illegitimate, that it had usurped power from the French Third

Republic, and that it was

a puppet state of Nazi Germany. In a BBC

broadcast on June 18, 1940 (the so-called “Appeal of 18 June”; French: Appel du

18 juin), he called on the French people to reject the Vichy regime and resist the German occupiers.

Initially, de Gaulle received little support in France

and among expatriate French, who regarded the Petain regime as being the

constitutionally legitimate authority for France.

Despite the armistice agreement’s stipulation that

deactivated the French naval forces, the British government feared that the French

fleet would be seized by the Germans who then would use it to invade Britain. Thus, on July 3, 1940, British ships attacked

the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir (in Algeria),

sinking or damaging several French ships, while the French squadron at Alexandria (in Egypt) allowed itself to be

interned by the British fleet.

By October 1940, the Petain regime had began to actively

collaborate in implementing the Nazi government’s Anti-Semitism laws. Using information of the poll registers on

the Jewish population that earlier had been collected by the French police,

French authorities and the Gestapo (German secret police), working together or

separately, conducted raids where thousands of Jews (as well as other

“undesirables”) were rounded up and confined in internment camps for eventual

transport to concentration and extermination camps in Eastern Europe; many

concentration camps also were set up in France.

Of the 330,000 Jews in France,

some 77,000 perished in the Holocaust, a death rate of 25%.

As the armistice agreement also required France to pay the cost of the

German occupation, the French became dependent on and subservient to German

impositions. French farm production and

resources were seized by the Germans, resulting in the deterioration of the French

economy and causing severe hardships to the French people, who suffered food

and fuel shortages or rationing, curfew, and restricted civil liberties.

The Battle of France resulted in some 1.5 million French

soldiers becoming German prisoners of war.

To prevent Vichy France from re-mobilizing these troops, German

authorities kept these French soldiers in labor camps in Germany and France,

although some 500,000 were later released at various times, and the remaining

one million freed by the Allies at the end of World War II.

By 1941, a French resistance movement comprising many small

groups had emerged, with its memberships increased by the influx of communists

following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, and forced work

evaders following the implementation of Service du Travail Obligatoire

(“Obligatory Work Service”) in February 1943. The French resistance soon also made contact

with de Gaulle’s government-in-exile, the British Special Operations Executive

(SOE) and the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which sent supplies and

agents. The resistance conducted

sabotage operations against military-vital targets, provided the Allies with

intelligence information, and sheltered and helped escape downed Allied airmen,

Jews, and other elements targeted by German and Vichy authorities.

In November 1942, following the Allied invasion of western

North Africa, the German military also occupied the territory of Vichy France

in order to safeguard the southern flank.

The Italian occupation zone also was expanded. While France

ostensibly continued its sovereignty over its territories, in reality, German

military authority came into force throughout France,

and the Vichy

government exercised little power. The

German occupation of Vichy France also ended the latter’s diplomatic

relations with the United States,

Canada,

and other Allies, and also with many neutral states.

July 10, 2020

July 10, 1951 – Korean War: The start of armistice negotiations

On July 10, 1951, representatives from the warring sides, China and North Korea on the one hand, and the United States, South Korea, and the United Nations on the other, opened armistice talks at Kaesong to end the Korean War. Kaesong (now part of North Korea) was located near the northern edge of the battle lines. Negotiations proved lengthy and contentious and proceeded slowly, with long intervals between meetings. Talks were later moved to Panmunjom, a nearby village, where an armistice would be signed in July 1953.

Key areas during the Korean War

Key areas during the Korean War(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Continuing hostilities before and during the armistice talks U.S. and South Korean forces settled down to a defensive posture, fortifying existing positions. Meanwhile at the United Nations, American and Soviet delegates met to try and end the war. Then on June 23, 1951, the Soviet representative to the UN proposed an armistice between China and North Korea on the one hand, and the United States, South Korea, and the UN, on the other hand, a proposal that was received favorably by the U.S. and Chinese governments. On July 10, 1951, delegates from the warring parties opened armistice talks at Kaesong. Within a few months, negotiations were moved six miles east to Panmunjom, which became the permanent site of negotiations. Subsequently, for the Korean War, the active phase of full-scale warfare came to an end.

Kim Il-sung and Syngman Rhee, leaders of North Korea and

South Korea, respectively, strongly opposed the peace negotiations and wanted

to continue the war, as both were determined to reunify the Korean Peninsula

by force under their rule. But without

the support of the major powers, the two Korean governments were forced to back

down. The negotiations proved long and

arduous, and ultimately lasted two years (July 1951-July 1953) punctuated by a

number of stoppages in the talks. During

this period, the fighting produced no major territorial changes, leading to a

stalemate in the battlefield.

One major cause of the delay in the settlement was that the

war had produced an uneven line across the 38th parallel, with the central and

eastern sections being north of the parallel and the western section being

south of the parallel, and with a net territorial loss to North Korea. Chinese and North Korean delegates argued

that the 38th parallel must be the armistice line, which American and South

Korean representatives opposed, stating that the current frontlines must be the

armistice line, as these are much more defensible compared to the topography

along the 38th parallel. By late 1951,

with no agreement reached and fighting continuing, the communist side dropped

its demand of opposing forces returning to the 38th parallel, and the two

warring sides came to an agreement that the frontlines during the time of the

signing of a truce would serve as the armistice line.

A second major point of contention was the issue of the

prisoners of war (POWs). UN forces held

some 150,000 Chinese and North Korean POWs, of which a sizable number refused

to be repatriated back to the their homelands, which provoked China and North

Korean to accuse UN forces of using underhanded methods to prevent

repatriation. In particular, the Chinese

government claimed that anti-communist Chinese POWs were allowed to torture

communist Chinese POWs to force the latter to refuse being repatriated. In one notable event in mid-June 1953 (one

month before the armistice agreement was signed), the South Korean government

released some 27,000 anti-communist North Korean POWs, stating that the

prisoners had escaped from prison.

On the UN side, American and South Korean POWs were much

more subject to physical abuse than other UN prisoners, especially by their

North Korean captors. American POWs

suffered from tortures, starvation, and forced labor, if not being outright

executed. UN prisoners in Chinese POW

camps rarely were executed, but suffered mass starvation, particularly in the

1950-1951 winter, where nearly half of all U.S. POWs died from hunger. Responding to accusations by the Truman

administration that American POWs were being ill-treated, the Chinese government

stated that because its logistical system suffered severe inadequacies, food

shortages were widespread at the frontlines, and in fact thousands of its own

troops also perished from starvation (as well as from the sub-zero harsh winter

conditions).

Furthermore, 80,000 South Korean soldiers remained missing,

whom the UN command and South Korean government believed had been captured by

North Korean forces, and were then coerced into joining the North Korean Army

or were being used as forced laborers. North Korea

rejected these accusations, saying that it had only 10,000 South Korean POWs,

that its other POWs already had been released or were killed by the UN air

attacks, and that it did not use forced recruitment into its armed forces. As a result, the fates of the missing South

Korean POWS remained undetermined after the war.

The armistice talks ended the period of large-scale

offensives. Then during the ensuing

two-year period of stalemate, only small- to medium-scale limited-scope battles

took place. Most of these battles were

initiated by UN forces, and were aimed at gaining territory that would give the

UN forces better strategic and defensive positions.

In September-October 1951, after negotiations temporarily

broke down, American and South Korean forces launched a limited operation in

the central sector, advancing seven miles north of the Kansas Line. In the western sector, UN forces also

succeeded in establishing new positions north of the Wyoming Line.

U.S.

planes continued its domination of the skies, attacking enemy road and rail

networks, supply centers, and ammunition depots. In 1952, U.S.

air strikes in North Korea

increased. The vital hydroelectric

facility at Suiho was attacked in July, and Pyongyang was subject to a large raid in August. The attack on the North Korean capital, which

involved 1,400 air sorties, was the largest single-day air operation of the

war.

In May 1952, General Mark Clark became the new commander of

UN forces, replacing General Ridgway. In

June 1952, after a series of fierce clashes, U.S.

forces dislodged the enemy from the heights in Chorwon County,

and established 11 patrol bases in a number of hills, including the highest and

most strategically important hill called “Old Baldy”. Many intense battles took place during the

second half of 1952, as Chinese and North Korean forces attacked UN frontline

outposts in response to U.S.

air raids in North Korea. By this time, UN forces had adopted a

defensive posture, and fortified their positions with trenches, bunkers,

minefields, barbwire, and other obstacles all across the UN main line of

resistance from east to west of the peninsula.

In spring 1953, Chinese forces again put pressure on UN

lines. But by now with fortified

positions on both sides, the mounting casualties, the absence of large-scale

offensives, and the stalemated battlefield situation, the deadlock appeared to

last indefinitely. In April 1953, peace

talks resumed. Six months earlier, on

November 29, 1952, President-elect Dwight Eisenhower, who had just won the U.S. presidential elections three weeks earlier

and had promised to end the war, visited Korea to determine how the

negotiations could be accelerated. He

also threatened to use nuclear weapons in response to a build-up of Chinese

forces in the western sector of the line.

Furthermore, with the death of Soviet hard-line leader Joseph Stalin in

March 1953, the new Soviet government was more conciliatory with the West, and

put pressure on China to

reach a peace settlement in Korea.

On April 20-26, 1953, under Operation Little Switch, both

sides exchanged sick and wounded POWs.

In May-June 1953, as peace talks continued, Chinese forces launched

limited attacks on UN positions, which were repulsed with heavy Chinese losses

by American air, armored, and artillery firepower.

On June 18, 1953, the armistice negotiations produced a

mutually acceptable agreement. However,

the agreement was rejected by South Korean President Rhee, and shelved. Taking advantage of the new stalemate, on

July 6, 1953, the Chinese renewed their offensive, first attacking a UN outpost

known as Pork Chop Hill, which forced the defending American troops of the U.S.

7th Division to retreat after four days of fighting, with heavy losses to both

sides.

Then on July13, 1953, in the last major battle of the war, a

massive Chinese force of 250,000 troops, supported with heavy artillery (over

1,300 artillery pieces), struck at UN positions on a 22-kilometer front,

pushing the mainly defending South Korean forces 50 kilometers south and gaining

190 km2 of territory. However, the

victory was pyrrhic, as the Chinese casualties numbered some 60,000 troops,

compared to South Korean losses of 14,000 troops.

Meanwhile, armistice talks resumed, which culminated in an

agreement on July 19, 1953. Eight days

later, July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and

the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement,

which ended the war. A ceasefire came

into effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed. The Korean War was over.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldiers

killed, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; North

Korean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which included

Chairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying).

Civilian casualties were 2 million for South

Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Korean

refugees who had moved to South

Korea.

Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forces

conducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to be

supporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea,

during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militias

executed some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupation

of South Korea,

also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries”

(politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians who

refused to join the North Korean Army.

July 9, 2020

July 9, 1900 – Boxer Rebellion: 45 Christians are killed in the Taiyuan Massacre

On July 9, 1900, forty-five Christians, which included men, women, and children, were killed in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province in northern China during the Boxer Rebellion. It was long held that the killings were ordered by Shanxi Province governor Yuxian, who had imposed anti-foreign, anti-Christian policies in the province. More recent research indicates that the massacre resulted from mob violence rather than a direct order from the provincial government. Subsequently, some 2,000 Chinese Christians were killed in Shanxi Province. Also during this time across northern China, Christian missionaries and Chinese parishioners were being targeted for violence by the Boxers as well as by government troops.

Foreign spheres of influence in China in the early 1900s

Foreign spheres of influence in China in the early 1900s(Excerpts taken from Boxer Rebellion – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

The Boxers In the late 19th century, a secret society called the “Righteous and Harmonious Fists” (Yihequan) was formed in the drought-ravaged hinterland regions of Shandong and Zhili provinces. The sect formed in the villages, had no central leadership, operated in groups of tens to several hundreds of mostly young peasants, and held the belief that China’s problems were a direct consequence of the presence of foreigners, who had brought into the country their alien culture and religion (i.e. Christianity).

Sect members practiced martial arts and gymnastics, and performed mass religious rituals, where they invoked Taoist and Buddhist spirits to take possession of their bodies. They also believed that these rituals would confer on them invincibility to weapons strikes, including bullets. As the sect was anti-foreign and anti-Christian, it soon gained the attention of foreign Christian missionaries, who called the group and its followers “Boxers” in reference to the group’s name and because its members practiced martial arts.

The Qing government, long wary of secret societies which

historically had seditious motives, made efforts to suppress the Boxers. In

October 1899, government troops and Boxers clashed in the Battle of Senluo

Temple in northwest Shandong

Province. In this battle, Boxers proclaimed the slogan

“Support the Qing, destroy the foreign” which drew the interest of some

high-ranking conservative Qing officials who saw that the Boxers were a

potential ally against the foreigners.

Also by this time, the Boxers had renamed their organization as the “Righteous and Harmonious Militia

(Yihetuan)”, using the word “militia” to de-emphasize their origin as a secret

society and give the movement a form of legitimacy. Even then, the Qing government continued to

view the Boxers with suspicion. In

December 1899, the Qing court recalled the Shandong provincial governor, who had shown

pro-Boxer sympathy, and replaced him with a military general who launched an

anti-Boxer campaign in the province.

The Boxers’ grassroots organizational structure made its

suppression difficult. The movement rapidly

spread beyond Shandong

and Zhili provinces. By April-May 1900,

Boxers were operating in large areas of northern China,

including Shanxi and Manchuria,

and across the North China Plains. The

Boxers killed Chinese Christians, burned churches, and looted and destroyed

Christian houses and properties. As a

result of these attacks, and those perpetrated during the Boxer Rebellion, more

than 30,000 Chinese Christians, 130 Protestant missionaries, and 50 Catholic priests

and nuns were killed.

The Boxer movement’s decentralized organization was its main

strength, as individual units could mobilize and disband at will, and could be

transferred quickly to other areas. But

its lack of a unified structure and central leadership were also its weakest

points, as Boxer units were restricted by a lack of coordination and over-all

command. Boxers also suffered from a

lack of military training and adequate weapons, and thus fought at a great

disadvantage and easily broke apart when the fighting became intense.

By May 1900, thousands of Boxers were occupying areas around

Beijing,

including the vital Beijing-Tianjin railway line. They attacked villages, killed local

officials, and destroyed government infrastructures. The violence alarmed the foreign diplomatic

community in Beijing. The foreign diplomats, their staff, and

families in Beijing

had their offices and residences located at the Legation Quarter, located south

of the city. The Legation Quarter

consisted of diplomatic missions from eleven countries: Britain, France,

Russia, United States, Germany,

Austria-Hungary, Japan, Italy,

Belgium, Netherlands, and Spain.

In May 1900, the foreign diplomats asked the Qing government

that foreign troops be allowed to be posted at the Legation Quarter, which was

denied. Instead, the Chinese government

sent Chinese policemen to guard the legations.

But the foreign envoys persisted in their request, and on May 30, 1900,

the Chinese Foreign Ministry (Zongli Yamen) allowed a small number of foreign

troops to be sent to Beijing.

The next day (May 31), some 450 foreign sailors and Marines

were landed from ships from eight countries and sent by train from Taku to Beijing. But as the situation in Beijing

continued to deteriorate, the foreign diplomats felt that more foreign troops

were needed in Beijing. On June 6, 1900, and again on June 8, they

sent requests to the Zongli Yamen, with both being turned down. A separate request by the German Minister,

Clemens von Ketteler, to allow German troops to take control of the Beijing railway station

also was turned down. On June 10, 1900,

the Chinese government barred the foreign legations from using the telegraph

line that linked to Tianjin. In one of the last transmissions from the

Legation Quarter, British Minister Claude MacDonald asked British Vice-Admiral

Edward Seymour in Tianjin to send more troops,

with the message, “Situation extremely grave; unless arrangements are made for

immediate advance to Beijing,

it will be too late.” And with the

subsequent severing of the telegraph line between Beijing

and Kiachta (in Russia) on

June 17, 1900, for nearly two months thereafter, the Legation Quarter in Beijing would be cut off

from the outside world.

On June 11, 1900, the Japanese diplomat, Sugiyama Akira, was

killed by Chinese troops in a Beijing

street. Then on June 12 or 13, two

Boxers entered the Legation Quarter and were confronted by Ketteler, the German

Minister, who drove one away and captured the other; the latter soon was killed

under unclear circumstances. Later that

day, thousands of Boxers stormed into Beijing and went on a rampage, killing

Chinese Christians, burning churches, destroying houses, and looting

properties. In the next few days,

skirmishes broke out between foreign legation troops, and Boxers with the

support of anti-foreigner government units.

On June 15, 1900, British and German soldiers dispersed Boxers who

attacked a church, and rescued the trapped Christians inside; two days later

(June 17), an armed clash broke out between German–British–Austro-Hungarian

units and Boxer–anti-foreigner government troops.

The Belgian legation was evacuated, as were those of Austria-Hungary, the Netherlands,

and Italy,

when they came under Boxer attack. By

this time, the Christian missions scattered across Beijing were evacuated, with their clergy and

thousands of Chinese Christians taking shelter at the Legation Quarter. Soon, the Legation Quarter was fortified,

with soldiers and civilians building barricades, trenches, bunkers, and

shelters in preparation for a Boxer attack.

Ultimately, in the Legation Quarter were some 400 soldiers, 470

civilians (including 149 women and 79 children), and 2,800 Chinese Christians,

all of whom would be besieged in the fighting that followed. At the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) located some

three miles from the Legation Quarter, some 40 French and Italian soldiers, 30

foreign Catholic clergy, and 3,200 Chinese Christians also took refuge, turning

the area into a defensive fortification which also would come under siege

during the conflict.

Meanwhile in Taku, in response to British Minister

MacDonald’s plea for more troops to be sent to the Beijing foreign legations,

on June 10, Vice-Admiral Seymour scrambled a 2,200-strong multinational force

of Navy and Marine units from Britain, Germany, Russia, France, the United

States, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary, which departed by train from Tianjin

to Beijing. On the first day, Seymour’s force traveled to within 40 miles of Beijing without meeting opposition, despite the presence

of Chinese Imperial forces (which had received no orders to resist Seymour’s passage) along

the way. Seymour’s force reached Langfang, where the

rail tracks had been destroyed by Boxers.

Seymour’s

troops dispersed the Boxers guarding the area, and work crews started repair

work on the rail tracks. Seymour sent out a

scouting team further on, which returned saying that more sections of the

railroad at An Ting had also been destroyed.

Seymour then sent a train back to Tianjin to get more

supplies, but the train soon returned, its crew saying that the rail track at

Yangcun was now destroyed. Having to

fight off a number of Boxer attacks, his provisions running low, realizing the

futility of continuing to Beijing, and now

feeling trapped on both sides, Seymour called off the expedition and turned the

trains back, intending to return to Tianjin.

Elsewhere at this point, the Boxer crisis deteriorated even

further. On June 15, 1900, at the Yellow

Sea where Alliance ships were on high alert, and

were awaiting further developments, allied naval commanders became alarmed when

Qing forces began fortifying the Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho River,

as well as setting mines on the river and torpedo tubes at the forts. For Alliance

commanders, these actions threatened to cut off allied communication and supply

lines to Tianjin, threatening the foreign

enclave at Tianjin and Legation Quarter at Beijing, as well as Seymour’s

force. The foreign alliance had had no

communication with the Seymour

force for several days. Alliance commanders then

issued an ultimatum demanding that the Taku Forts be surrendered to them, which

the Qing naval command rejected. Early

on June 17, 1900, fighting broke out at the Taku Forts, with Alliance

forces (except the U.S.

command, which chose not to participate) launching a naval and ground assault

that seized control of the forts.

July 8, 2020

July 8, 1960 – Cold War: U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers is charged for espionage by the Soviet Union

On May 1, 1960, a United States U-2 spy plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers was shot over Soviet airspace by a Russian surface-to-air missile. Power’s mission, directed by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), as to take surveillance photographs on an overflight over central Russia from a base in Pakistan to another base in Norway.

Powers survived by parachuting to the ground where he was arrested by Soviet authorities. The U.S. government of President Dwight D. Eisenhower initially stated that the plane was on a NASA research mission but later admitted that the U-2 was conducting surveillance of Russian territory after the Soviet government produced the captured pilot and evidence of the plane’s wreckage, and more important, the intact surveillance equipment and photographs of Soviet military installations taken during the flight.

Subsequently, Powers was convicted of espionage and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. He did not serve the full sentence but was released in February 1962 on a prisoner exchange “spy swap” agreement between the American and Soviet governments.

Following the 1960 incident, the United States made changes to policy, procedures, and protocols regarding surveillance and reconnaissance missions. Subsequently, the U-2 was used in overflight missions in Cuba when in August 1962, the first evidence of the presence of Soviet nuclear-capable surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites were detected on the island, sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis.

NATO’s deployment of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s decision to install nuclear weapons in Cuba.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background of the Cuban Missile Crisis

After the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961 (previous article), the United States government under President John F. Kennedy focused on clandestine methods to oust or kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro and/or overthrow Cuba’s communist government. In November 1961, a U.S. covert operation code-named Mongoose was prepared, which aimed at destabilizing Cuba’s political and economic infrastructures through various means, including espionage, sabotage, embargos, and psychological warfare. Starting in March 1962, anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Florida, supported by American operatives, penetrated Cuba undetected and carried out attacks against farmlands and agricultural facilities, oil depots and refineries, and public infrastructures, as well as Cuban ships and foreign vessels operating inside Cuban maritime waters. These actions, together with the United States Armed Forces’ carrying out military exercises in U.S.-friendly Caribbean countries, made Castro believe that the United States was preparing another invasion of Cuba.

From the time he seized power in Cuba

in 1959, Castro had increased the size and strength of his armed forces with weapons provided by the Soviet Union. In Moscow, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev also believed that an American invasion was imminent, and increased Russian advisers, troops, and weapons to Cuba. Castro’s revolution had provided communism with a toehold in the Western Hemisphere and Premier Khrushchev was determined not to lose this invaluable asset. At the same time, the Soviet leader began to face a security crisis of his own when the United States under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) installed 300 Jupiter nuclear missiles in Italy in 1961 and 150 missiles in Turkey (Map 33) in April 1962.

In the nuclear arms race between the two superpowers, the United States held a decisive edge over the Soviet Union, both in terms of the number of nuclear missiles (27,000 to 3,600) and in the reliability of the systems required to deliver these weapons. The American advantage was even more pronounced in long-range missiles, called ICBMs (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles), where the Soviets possessed perhaps no more than a dozen missiles with a poor delivery system in contrast to the United States that had about 170, which when launched from the U.S. mainland could accurately hit specific targets in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet nuclear weapons technology had been focused on the more likely war in Europe and therefore consisted of shorter range missiles, the MRBMs (medium-range ballistic missiles) and IRBMs (intermediate-range ballistic missiles), both of which if installed in Cuba, which was located only 100 miles from southeastern United States, could target portions of the contiguous 48 U.S. States. In one stroke, such a deployment would serve Castro as a powerful deterrent

against an American invasion; for the Soviets, they would have invoked their prerogative to install nuclear weapons in a friendly country, just as the Americans had done in Europe. More important, the presence of Soviet

nuclear weapons in the Western Hemisphere would radically alter the global nuclear weapons paradigm by posing as a direct threat to the United States.

In April 1962, Premier Khrushchev conceived of such a plan, and felt that the United States would respond to it with no more than a diplomatic protest, and certainly would not take military action. Furthermore, Premier Khrushchev believed that President Kennedy was weak and indecisive, primarily because of the American president’s half-hearted decisions during the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961, and President Kennedy’s weak response to the East German-Soviet building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

A Soviet delegation sent to Cuba met with Fidel Castro, who gave his consent to Khrushchev’s proposal. Subsequently in July 1962, Cuba and the Soviet Union signed an agreement pertinent to the nuclear arms deployment. The planning and implementation of the project was done in utmost secrecy, with only a few of the top Soviet and Cuban officials being informed. In Cuba, Soviet technical and military teams secretly identified the locations for the nuclear missile sites.

In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane detected a Soviet nuclear missile site under construction in San Cristobal, Pinar del Rio. After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the continued presence of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, a U.S. military facility located at the eastern end of Cuba, greatly infuriated Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

In August 1962, U.S. reconnaissance flights over Cuba detected the presence of powerful Soviet aircraft: 39 MiG-21 fighter aircraft and 22 nuclear weapons-capable Ilyushin Il-28 light bombers. More disturbing was the discovery of the S-75 Dvina surface-to-air missile batteries, which were known to be contingent to the deployment of nuclear missiles. By late August, the U.S. government and Congress had raised the possibility that the Soviets were

introducing nuclear missiles in Cuba.

By mid-September, the nuclear missiles had reached Cuba by Soviet vessels that also carried regular cargoes of conventional weapons. About 40,000 Soviet soldiers

posing as tourists also arrived to form part of Cuba’s defense for the missiles and against a U.S. invasion. By October 1962, the Soviet Armed Forces in Cuba possessed 1,300 artillery pieces, 700 regular anti-aircraft guns, 350 tanks, and 150 planes.

The process of transporting the missiles overland from Cuban ports to their designated launching sites required using very large trucks, which consequently were spotted by the local residents because the oversized

transports, with their loads of canvas-draped long cylindrical objects, had great difficulty maneuvering through Cuban roads. Reports of these sightings soon reached the Cuban exiles in Miami, and through them, the U.S. government.

July 7, 2020

July 7, 1937 – Second Sino-Japanese War: The Marco Polo Bridge Incident takes place

On July 7, 1937, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident became the spark for the outbreak of hostilities between Japan and China in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Marco Polo Bridge (the Western name for the Lugou Bridge) is located southwest of the Chinese capital Beijing. On the evening of July 7, 1937, Japanese military units were conducting military exercises near the bridge when some exchange of gunfire broke out between them and Chinese forces positioned at the other side of the bridge. Soon after, the Japanese command learned that one of its soldiers was missing (but who later returned). Japanese authorities demanded to search Wanping for the missing soldier, which the Chinese refused . By early July 8 with increasing tensions, the two sides began massing infantry and armoured units into the surrounding area of the bridge. Soon, skirmishes and artillery bombardment broke out. Attempts by both sides to negotiate an end to the fighting led to a ceasefire, but which ultimately failed to defuse tensions. Full-scale fighting soon commenced in the capital and elsewhere, starting the Second Sino-Japanese War on July 8, 1937.

In the period before the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, heightened tensions already existed between the two countries following the Japanese Invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and further Japanese incursions into northern China.

East Asia.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5)

Prelude

The Japanese invaded Manchuria in September 1931, gaining control of the territory by February 1932. While the Manchurian conflict was yet winding down, another crisis erupted in Shanghai in January1932, when five Japanese Buddhist monks were attacked by a Chinese mob. Anti-Japanese riots and demonstrations led the Japanese Army to intervene, sparking full-scale fighting between Chinese and Japanese forces. In March 1932, the Japanese Army gained control of Shanghai, forcing the Chinese forces to withdraw.

With the League of Nations providing no more than a rebuke of Japan’s aggression,

Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek saw that his efforts to force international pressure to restrain Japan had failed. In January 1933, to secure Manchukuo, a combined Japanese-Manchukuo force invaded Jehol Province,

and by March, had pushed the Chinese Army south of the Great Wall into Hebei Province.

Unable to confront Japan militarily and also beset by many internal political troubles, Chiang was compelled to accept the loss of Manchuria and Jehol Province. In March 1933, Chinese and Japanese representatives met to negotiate a peace treaty. In May, the two sides signed the Tanggu Truce (in Tanggu, Tianjin), officially ending the war, which provided the following stipulation that was wholly favorable to Japan: a 100-km demilitarized zone was

established south of the Great Wall extending from Beijing to Tianjin, where Chinese forces were barred from entering, but where Japanese planes and ground units were allowed to patrol.

In the immediate aftermath of Japan’s

conquest of Manchuria, many anti-Japanese partisan groups, called “volunteer armies”, sprung up all across Manchuria. At its peak in 1932, this resistance movement had some 300,000 fighters who engaged in guerilla warfare attacking Japanese patrols and isolated outposts, and carrying out sabotage actions against Manchukuo infrastructures. Japanese-Manchukuo forces launched a series of “anti-bandit” pacification campaigns that gradually reduced rebel strength over the course of a decade. By the late 1930s, Manchukuo was deemed nearly pacified, with the remaining by now small guerilla bands

fleeing into Chinese-controlled territories or into Siberia.

The conquest of Manchuria formed only one part of Japan’s “North China Buffer State Strategy”, a broad program aimed at establishing Japanese sphere of influence all across northern China. In 1933, in China’s

Chahar Province (Figure 32) where a separatist

movement was forming among the ethnic Mongolians, Japanese military authorities

succeeded in winning over many Mongolian nationalists by promising them military and financial support for secession. Then in June 1935, when four Japanese soldiers who had entered Changpei district (in Chahar Province) were arrested and detained (but eventually

released) by the Chinese Army, Japan issued a strong diplomatic protest against China. Negotiations between the two sides followed,

leading to the signing of the Chin-Doihara Agreement on June 27, 1935, where China agreed to end its political, administrative, and military control over much of Chahar Province. In August 1935, Mongolian nationalists, led

by Prince Demchugdongrub, forged closer ties with Japan. In December, with Japanese support, Demchugdongrub’s forces captured northern Chahar, expelling the remaining

Chinese forces from the province.

In May 1936, the “Mongol Military Government” was formed in Chahar under Japanese sponsorship, with Demchugdongrub as its leader. The new government then signed a mutual assistance pact with Japan. Demchugdongrub soon launched two offensives (in August and November 1936) to take neighboring Suiyuan Province, but his forces were repelled by a pro-Kuomintang warlord ally of Chiang. However, another offensive in 1937 captured the province. With this victory, in September 1939, the Mengjiang United Autonomous Government was formed, still nominally under Chinese sovereignty but wholly under Japanese control, which consisted of the provinces of Chahar, Suiyuan, and northern Shanxi.

Elsewhere, by 1935, the Japanese Army wanted to bring Hebei Province under its control, as despite the Tanggu Truce, skirmishes continued to occur in the demilitarized zone located south of the Great Wall. Then in May 1935, when two pro-Japanese heads of a local news agency were assassinated, Japanese authorities presented the Hebei provincial government with a list of demands, accompanied with a show of military force as a warning, if the demands were not met. In June 1935, the He-Umezu Agreement was signed, where China ended its political, administrative, and military control of Hebei

Province. Hebei then came under the sphere of influence of Japan, which then set up a

pro-Japanese provincial government.

China’s long period of acquiescence and appeasement ended in December 1936 when

Chiang’s Nationalist government and Mao Zedong’s Communist Party of China forged a united front to fight the Japanese Army. Full-scale war between China and Japan began eight months later, in July 1937.

July 6, 2020

July 6, 1937 – Spanish Civil War: The start of the Battle of Brunete, where Republican forces attack the Nationalists to ease pressure on Madrid

On July 6, 1937, Republican forces launched an offensive on the Nationalists to relieve pressure on the besieged capital Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. The attack gained ground but soon sputtered. With the Nationalists launching a counter-offensive, the Republicans were forced to retreat after suffering heavy losses in men, particularly in the ranks of the International Brigades, as well as material. The International Brigades were a militia organized by the COMINTERN (Communist International) based in Paris, and consisted mostly of communist civilian volunteers from many countries including the Soviet Union, France, United States, Britain, France, Germany and Italy. In total, some 35,000 – 50,000 International Brigades volunteers fought in the Spanish Civil War.

The contribution of the Condor Legion, the German expeditionary air force, to the Nationalist victory, allowed Germany to gain substantial trade concessions from the Nationalists, with the latter agreeing to send raw materials to Germany.

Key areas during the Spanish Civil War

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Aftermath of the Spanish Civil War

Following the war, General Franco established a right-wing, anti-communist dictatorial government centered on the Falange Party. Socialists, communists, and anarchists, were outlawed, as were free-party politics. Political enemies were killed or jailed; perhaps as many as 200,000 lost their lives in prison or through executions. The political autonomies of Basque and Catalonia were voided. These regions’ culture, language, and identity were suppressed, and a single Spanish national identity was enforced.

After World War II ended, Spain became politically and economically isolated from most of the international community because of General Franco’s association with the defeated fascist regimes of Germany and Italy. But with increasing tensions in the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union, the U.S. government became drawn to Spain’s staunchly anti-communist stance and its strategic location at the western end of the Mediterranean Sea.

In September 1953, Spain and the United States entered into a defense agreement known as the Pact of Madrid, where the U.S. government infused large amounts of

military assistance to Spain’s defense. As a result, Spain’s diplomatic isolation ended, and the country was admitted to the United Nations in 1955.

Its economy devastated by the civil war, Spain experienced phenomenal economic growth during the period from 1959 to 1974

(known as the “Spanish Miracle”) when the government passed reforms that opened

up the financial and investment sectors.

Spain’s totalitarian regime ended with General Franco’s death in 1975; thereafter, the country transitioned to a democratic parliamentary monarchy which it is today.

July 5, 2020

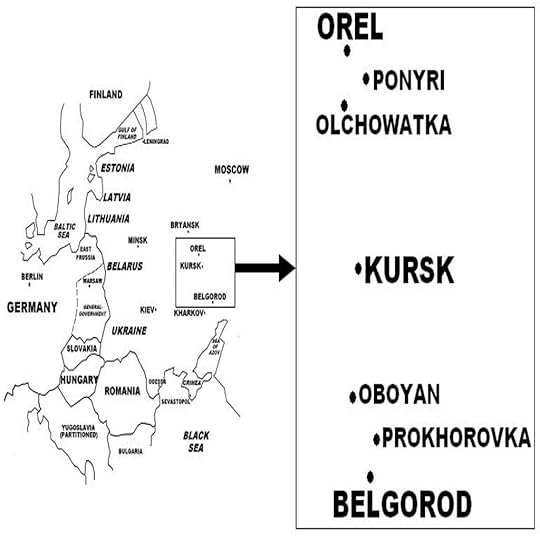

July 5, 1943 – World War II: German and Soviet forces clash at the Battle of Kursk

On July 5, 1943, the German Army launched Operation Citadel, attacking north and south to pinch off Soviet positions at the Kursk salient. The offensive made little headway in the face of extensive Soviet defensive lines consisting of minefields, fortifications, artillery fire zones, and anti-tank positions that stretched 300 km deep. Further, on July 12, Adolf Hitler ordered that the

offensive be discontinued to transfer German units to southern Italy, where the Western Allies had just opened a new front.

For some time, it was widely believed that the Battle of Kursk, particularly the German-Soviet armoured encounter at Prokhorovka, featured the largest combined number of tanks that was brought into battle. Studies using newly released Soviet archives confer this distinction to an earlier Soviet-German armoured encounter, the Battle of Brody (June 1941), at the start of Operation Barbarossa.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 6 – World War II in Europe)

Preparations

On March 10, 1943, as the battle of Kharkov was winding down, General Manstein, head of German Army Group South, set his sights on eliminating a large gap around Kursk that had formed between his forces and those of German Army Group Center. With Hitler issuing Order No. 5 (March 13) authorizing such an operation, General Manstein and General Gunther von Kluge, commander of German Army Group Center, made preparations to immediately attack the Kursk salient. But with strong Soviet concentrations on the northern side of the salient, as well as reinforcements being rushed to the south to stem General Manstein’s northern advance, the proposed joint offensive was suspended. By then also, German forces were exhausted, and the rasputitsa season had set in, preventing further large-scale armored movement.

The Kursk salient was a Soviet protrusion into German-occupied territory, measuring 160 miles long from north to south and 100 miles from east to west. Kursk and the surrounding region held no strategic value to either side, but to the Germans (and the Soviets), pinching off the salient would eliminate the danger to their flanks.

In April 1943, Hitler’s Order No. 6 formalized the attack on the Kursk salient under Operation Citadel, which consisted of a pincers movement aimed at trapping five Soviet armies, with the northern pincer of

German Army Group Center’s 9th Army thrusting from Orel, and the southern pincer of German Army Group South’s 7th Panzer Army and German Army Detachment Kempf advancing from around Belgorod. The offensive was set for May 3.

In late April 1943, Kluge expressed doubts to Hitler about the feasibility of Operation Citadel, as German air reconnaissance showed that the Soviets were constructing strong fortifications along the northern side of the salient. As well, General Manstein was concerned, as his idea of launching a surprise attack on the unfortified salient could not be achieved anymore. The May 3 launch was not met, and on May 4, Hitler met with Generals

Kluge and Manstein and other senior officers to discuss whether or not Operation Citadel should proceed, or that other options be explored. But as the meeting produced no consensus, Hitler remained committed to the operation, resetting its launch for June 12,

1943. With other issues consequently

coming up, Hitler postponed the launch date to June 20, then to July 3, and finally to July 5, 1943.

As Operation Citadel was successively pushed back, with the delays ultimately lasting over two months, it also grew in importance, as

Hitler saw Kursk as the battle that would

restore German superiority in the Eastern Front following the Stalingrad debacle, which continued to weigh heavily on him and the German High Command. Like his generals, Hitler was concerned with the massive Soviet buildup in the salient, but believed that his

forces would break through, as well as surprise the enemy, using the Wehrmacht’s latest armored weapons, the versatile Panther tank, the heavy Tiger battle tank, and the goliath Elefant (“Elephant”) tank destroyer. Regaining the military initiative with a victory at Kursk also might convince Hitler’s demoralized Axis partners, Italy, Romania, and Hungary, whose armies were battered at Stalingrad, to reconsider quitting the war.

Hitler’s concerns regarding Kursk were warranted, as the Soviets were indeed fully concentrating on the region. But unbeknown to Hitler and the German senior staff, Stalin and the Soviet High Command were aware of many details of Operation Citadel, with the

information being provided to Soviet intelligence by the Lucy spy ring, a network of anti-Nazi German officers working clandestinely in cooperation with the Swiss intelligence bureau. Stalin and a number of senior officers wanted to launch a pre-emptive attack to disrupt the German plans.

However, General Georgy Zhukov, deputy head of the Soviet High Command and who was instrumental in the Soviet successes in Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad and was therefore highly regarded by Stalin, convinced the latter to adopt a strategic defense against the German attack, and then to launch a counter-offensive after the Wehrmacht was weakened. Under General Zhukov’s direction, the Soviet Central Front and Voronezh Front, which defended the northern and southern

sides of the salient respectively, implemented a “defense-in-depth” strategy: using 300,000 civilian laborers, six defensive lines (three main forward and three secondary rear lines) were constructed on either side of Kursk, the total

depth reaching over 90 miles. These defensive lines, particularly the main forward lines, were fortified with minefields, wire entanglements, anti-tank obstacles, infantry trenches, dug-in

armored vehicles, and artillery and machinegun emplacements.

A German attack, even if it broke through all six lines while facing furious Soviet artillery fire in the minefields in between each line, would then encounter additional defensive lines by the reserve Soviet Steppe Front; by then, the Germans would have advanced through many defensive layers a distance of 190 miles under continuous Soviet air and armored counter-attacks and artillery fire.

The buildup to Kursk also saw the Soviets making extensive use of military deception, e.g. dummy airfields, camouflaged artillery positions, night movement of troops, false

radio communications, concealed troop concentrations and ammunition stores,

spreading rumors in German-held areas, etc.

These measures were so effective that the Germans grossly underestimated Soviet strength at Kursk: at the start of the battle, the Red Army had assembled 1.9 million troops,

5,100 tanks, and 25,000 artillery pieces and mortars, while the Germans fielded 780,000 troops, 2,900 tanks, and 10,000 artillery pieces and mortars. This great imbalance of forces, as well as large numbers of Red Army reserves and extensive Soviet defensive preparations,

would be decisive in the outcome of the battle.

Battle

To pre-empt the Germans, on the night of July 4, 1943, the Red Army launched a massive artillery bombardment along the northern and southern zones of the salient, but which caused only light damage or disrupt German forces assembling for the attack. Early on April 5, the Wehrmacht opened its own artillery barrage, and thereafter, German 9th Army in the north and German 4th Panzer Army and Army Detachment Kempf (the latter having the strength of a regular field army; so-named after its commander, General Werner Kempf) in the south, launched their ground offensives.

The German plan was for the northern and southern forces to conduct a pincers movement to trap and destroy Soviet forces in the Kursk salient. The Battle of Kursk was on.

July 4, 2020

July 4, 1994 – Rwandan Genocide: Rebels capture the capital Kigali

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2 Twenty Wars that shaped the Present World)

On July 4, 1994, Kigali fell to the Rwandan Patriotic Front as the Rwandan Army abandoned the city after running low on ammunitions. The Hutu government had vacated Kigali at the start of the siege, moving its headquarters to Gitarama in the east. With the rebels’ capture of Gitarama in mid-June, the government moved its capital to the north, first to Ruhengeri, and later, Gisenyi, both of which fell on July 13 and July 18, respectively.

Rwandan Civil War. In April 1994, the Rwandan Genocide was in full swing, with Hutus targeting Tutsis. From their bases in northern Rwanda, Tutsi rebels launched separate offensives aimed at Kibungo in the southeast, Ruhengeri in the north, and Kigali, Rwanda’s capital.

On many occasions, the UN called for a ceasefire, but each time, this was rejected by rebel leader Paul Kagame. Then prompting on France’s suggestion, the UN established a security zone in the southwest region of Rwanda in areas that had not yet fallen to the rebels. The UN purposed the security zone to be used as a sanctuary for civilians affected by the war. On July 23, 1994, France led a coalition force (comprising military units from a number of countries) that took control of the security zone. Hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees and soldiers entered the security zone to escape the ever-widening areas being captured by the rebels. The presence of the French forces deterred the rebels from entering the security zone in pursuit of the Rwandan Army.

The UN mandate on the security zone ended on August 21, forcing the French-led coalition to withdraw completely from Rwanda. The Hutus fled from the security zone, which was then occupied by the Tutsi rebels. Shortly thereafter, Kagame brought the whole country under his control. The Rwandan Civil War was over.

Background

Rwanda, a small country in Africa, experienced a long period of ethnic unrest before and after it gained its independence in the 1960s. Then in the 1990s, this unrest culminated in two events known as the Rwandan Civil War and

the Rwandan Genocide, both of which caused great loss in human lives and massive destruction of the country.

The conflict revolved around the hostility between Rwanda’s two main ethnic groups, the majority Hutus, who comprised 85% of the population, and the Tutsis, who made up 14% of the population. The origin of this hostility goes back many centuries to when a Tutsi monarchy was established in the Hutu-populated land of what is present-day Rwanda. Over time, the Tutsi monarch gained

domination over the Hutus. The Tutsi monarch also acquired ownership over most of the land, which he divided into vast estates that were overseen by a hierarchy of Tutsi overlords, and worked by Hutu laborers in a feudal-type system. For the most part, however, Tutsis and Hutus lived in harmony. In the course of time, some Hutus became wealthy, while many ordinary, non-aristocratic Tutsis remained poor.

Rwandan Genocide

On April 6, 1994, President Habyarimina and Burundi’s head of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira, were killed by undetermined assassins when

their plane was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade as it was about to land

in Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government took over power in Rwanda.

Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the new government unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murder Tutsis and moderate Hutus on sight. Over the next several weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”, large numbers of civilians were murdered in Kigali

and throughout the country. No place was safe; in some instances, even Catholic churches were the scenes of the massacres of thousands of Tutsis where they had taken refuge.

The attackers used clubs, spears, firearms, and grenades, but their main weapon was the machete, with which they had trained extensively and which they used to hack away at their victims. At the urging of local officials, Hutu civilians joined in the killing frenzy, and turned against their Tutsi neighbors, acquaintances, and even relatives. In many cases, the threat of being killed for appearing sympathetic to Tutsis forced many otherwise disinterested Hutus to participate.

The Rwandan Army provided the Interahamwe with a list of Tutsis to be killed, and raised road blocks to prevent any escape. The death toll in the Rwandan Genocide ranges from between 800,000 to one million; some 10% of the fatalities were moderate

Hutus. The genocide lasted for about 100

days, from between April 6 to July 15, producing a killing rate of 10,000 persons a day. The speed by which it was carried out makes the Rwandan Genocide the fastest in history. (By comparison, the Holocaust in Europe during World War II, although producing a much higher death toll, was carried out over a number of years.)

During the course of the genocide, the UN force in Rwanda was ordered not to intervene by the UN Secretary General. In any case, the UN force was seriously undermanned and only lightly armed to stop the widespread violence.

The UN peacekeepers, however, managed to protect the civilians inside their zone of authority. Shortly after the violence began, foreign diplomats and their staff from the various embassies in Kigali fled the country. Other civilian expatriates were evacuated as well. The international community, including the Western powers, chose not to intervene

in the genocide or misread the upsurge in violence as just another combat phase in the civil war.

July 3, 2020

July 3, 1940 – World War II: The British Navy attacks the French fleet in Mers El Kebir

On July 3, 1940, British ships attacked and destroyed the French fleet at Mers El Kebir, in French Algeria. Some 1,300 French sailors were killed and another 350 wounded; 1 battleship was sunk and another 2 damaged; 3 destroyers were damaged and another grounded. British losses were 2 sailors killed and 6 aircraft shot down.

The British attack came after France had signed armistices with Germany and Italy on June 22, 1940. The British feared that the new French state, called Vichy France, would hand over its fleet to Germany or that it would be seized by the German Navy. The British had opened negotiations with French authorities in North Africa to hand over the French fleet, or even continue the war against Germany. But these negotiations failed, prompting the British to launch the attack at Mers El Kebir; French ships docked in British ports were also attacked.

Another French fleet in Alexandria, in Egypt, was blockaded by the British Navy. After difficult negotiations, the French commander allowed his fleet to be disarmed and to remain in port until the end of the war.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 6 – World War II in Europe)

Aftermath of the German Invasion of France

Despite Germany’s overwhelming military position at the end of hostilities, the armistice negotiations were conducted with consideration of other realities: for Hitler, that the French government and army could very well move to French colonies in North Africa from where they could continue the war; and for the French government, that it wanted to remain in France but only if the Germans did not impose “dishonorable or excessive” terms. Terms that were deemed unacceptable included the following: that all of France would be occupied, that France should surrender its navy, or that France should relinquish its (vast) colonial territories.

Not only did Hitler not impose these terms, in fact, he desired that France remain a sovereign state for diplomatic and practical

reasons: in the first case, France had ostensibly switched sides in the war, isolating Britain; and in the second case, France, with its large navy, would maintain its global colonial empire, which Germany could not because it did not

have enough ships.

Thus, in the armistice agreement, France was allowed to remain a fully sovereign state, with its mainland territory and colonial possessions intact, with some exceptions: Alsace-Lorraine became part of the Greater German Reich, although not formally annexed into Germany; and Nord and Pas-de-Calais were attached to Belgium in the “German Military Administration of Belgium and Northern France”. France also retained its navy, but which was demobilized and disarmed, as were the other branches of the French armed forces.

Because of the continuing hostilities with Britain, as part of the armistice agreement, the

German Army occupied the northern and western sections of France (some 55% of the French mainland), where it imposed military rule. The occupation was intended to be temporary until such time that Germany had defeated or had come to terms with Britain, which both the French and German governments believed was imminent. The Italian military also occupied a small area in the French Alps. In the rest of France (comprising 45% of the French mainland), which was not occupied and thus called zone libre (“free zone”), on July 10, 1940, the French government formed a new polity called the

“French State” (French: État français), which dissolved the French Third Republic, and was led by Petain as Chief of State.

The “French State” had its capital at Vichy, some 220 miles south of Paris, and was commonly known as “Vichy France”. Officially, Vichy France retained sovereignty over all France, but in reality, it exercised little authority in the occupied zones. Vichy France did have full administrative power in zone libre, and in the ongoing war, it maintained a policy of neutrality (e.g. it did not join the Axis), and was internationally recognized, and maintained diplomatic relations with the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, even Britain, and many neutral countries.

The Vichy government imposed authoritarian rule, with Petain holding broad powers, which was a full turn-around and rejection of the liberalism and democratic ideals of the French Third Republic. Using Révolution nationale (“National Revolution”) as its official ideology, the Petain regime turned inward-looking (la France seule, or “France alone”), was deeply conservative and traditionalist, and rejected liberal and modernist ideas. Traditional culture and religion were promoted as the means for the regeneration of France. The separation of Church and State was abolished, with Catholics playing a major role in affairs, the French Third Republic was reviled as morally decadent and causing France’s military defeat,

and anti-Semitism and xenophobia predominated, with Jews and other “undesirables”, including immigrants, gypsies, and homosexuals being persecuted. Communists and left-wingers, and other radicals were included in this category following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Xenophobia was particularly directed against Britain, with Petain and other leaders expressing strong antipathy with the British, calling them France’s “hereditary” and lasting enemy.

The Vichy regime was challenged by General Charles de Gaulle, who in June 1940 in Britain, formed a government-in-exile called Free France, and an army, the Free French

Forces. De Gaulle criticized Vichy France as illegitimate, that it had usurped power from the French Third Republic, and that it was

a puppet state of Nazi Germany. In a BBC

broadcast on June 18, 1940 (the so-called “Appeal of 18 June”; French: Appel du 18 juin), he called on the French people to reject the Vichy regime and resist the German occupiers.

Initially, de Gaulle received little support in France and among expatriate French, who regarded the Petain regime as being the

constitutionally legitimate authority for France.

Despite the armistice agreement’s stipulation that deactivated the French naval forces, the British government feared that the

French fleet would be seized by the Germans who then would use it to invade Britain. Thus, on July 3, 1940, British ships attacked the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir (in Algeria),

sinking or damaging several French ships, while the French squadron at Alexandria (in Egypt) allowed itself to be interned by the British fleet.

By October 1940, the Petain regime had began to actively collaborate in implementing the Nazi government’s Anti-Semitism laws. Using information of the poll registers on the Jewish population that earlier had been collected by the French police, French authorities and the Gestapo (German secret police), working together or separately, conducted raids where thousands of Jews (as well as other “undesirables”) were rounded up and confined in internment camps for eventual

transport to concentration and extermination camps in Eastern Europe; many concentration camps also were set up in France. Of the 330,000 Jews in France, some 77,000 perished in the Holocaust, a death rate of 25%.

As the armistice agreement also required France to pay the cost of the German occupation, the French became dependent on and subservient to German impositions. French farm production and resources were seized by the Germans, resulting in the

deterioration of the French economy and causing severe hardships to the French people, who suffered food and fuel shortages or rationing, curfew, and restricted civil liberties.

The Battle of France resulted in some 1.5 million French soldiers becoming German prisoners of war. To prevent Vichy France from re-mobilizing these troops, German

authorities kept these French soldiers in labor camps in Germany and France, although some 500,000 were later released at various times, and the remaining one million freed by the Allies at the end of World War II.

By 1941, a French resistance movement comprising many small groups had emerged, with its memberships increased by the influx of communists following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, and forced work evaders following the implementation of Service du Travail Obligatoire (“Obligatory Work Service”) in February 1943. The French resistance soon also made contact with de Gaulle’s government-in-exile, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which sent supplies and agents. The resistance conducted sabotage operations against military-vital targets, provided the Allies with

intelligence information, and sheltered and helped escape downed Allied airmen, Jews, and other elements targeted by German and Vichy authorities.

In November 1942, following the Allied invasion of western North Africa, the German military also occupied the territory of Vichy France in order to safeguard the southern flank. The Italian occupation zone also was expanded. While France ostensibly continued its sovereignty over its territories, in reality, German military authority came into force throughout France, and the Vichy government exercised little power. The German occupation of Vichy France also ended the latter’s diplomatic relations with the United States,

Canada, and other Allies, and also with many neutral states.

July 2, 2020

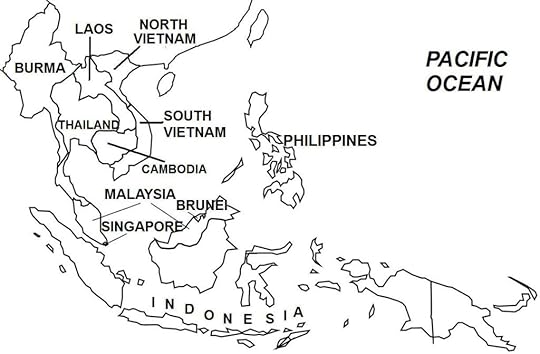

July 2, 1976 – Vietnam War: North and South are reunified at the end of the war

On July 2, 1976, the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) was dissolved, and its people and territory were reunified with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), with the merger giving rise to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam that exists today. The reunified Vietnam came following the fall of the South Vietnamese capital Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War in April 30, 1975.

At the end of the Vietnam War, the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) was tasked to govern South Vietnam preparatory to reunification. The PRG was a South Vietnamese subversive organization that formed in June 1969 consisting of a broad coalition of communist, non-communist, anti-imperialist, farmers, workers, and ethnic groups that opposed the current South Vietnamese government. After reunification, the PRG was dissolved.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath of the Vietnam War

The war had a profound, long-lasting effect on the United States. Americans were bitterly divided by it, and others became disillusioned with the government. War cost, which totaled some $150 billion ($1 trillion in 2015 value), placed a severe strain on the U.S. economy, leading to budget deficits, a weak dollar, higher inflation, and by the 1970s, an economic recession. Also toward the end of the war, American soldiers in Vietnam suffered from low morale and indiscipline, compounded by racial and social tensions resulting from the civil rights movement in the United States during the late 1960s and also because of widespread recreational drug use among the troops. During 1969-1972 particularly and during the period of American de-escalation and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, U.S. soldiers became increasingly unwilling to go to battle, which resulted in the phenomenon known as “fragging”, where soldiers, often using a fragmentation grenade, killed their officers whom they thought were overly zealous and eager for combat action.

Furthermore, some U.S. soldiers returning from Vietnam were met with hostility, mainly because the war had become extremely unpopular in the United States, and as a result of news coverage of massacres and atrocities committed by American units on Vietnamese civilians. A period of healing and reconciliation eventually occurred, and in 1982, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was built, a national monument in Washington, D.C. that lists the names of servicemen who were killed or missing in the war.

Following the war, in Vietnam and Indochina, turmoil and conflict continued to be widespread. After South Vietnam’s collapse, the Viet Cong/NLF’s PRG was installed as the caretaker government. But as Hanoi de facto held full political and military control, on July 2, 1976, North Vietnam annexed South Vietnam, and the unified state was called the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Some 1-2 million South Vietnamese, largely consisting of former government officials, military officers, businessmen, religious leaders, and other “counter-revolutionaries”, were sent to re-education camps, which were labor camps, where inmates did various kinds of work ranging from

dangerous land mine field clearing, to less perilous construction and agricultural labor, and lived under dire conditions of starvation diets and a high incidence of deaths and diseases.

In the years after the war, the Indochina refugee crisis developed, where some three million people, consisting mostly of those targeted by government repression, left their homelands in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos,

for permanent settlement in other countries.

In Vietnam, some 1-2 million departing refugees used small, decrepit boats to embark on perilous journeys to other Southeast Asian nations. Some 200,000-400,000 of these “boat people” perished at sea, while survivors who eventually reached Malaysia, Indonesia,

Philippines, Thailand, and other destinations were sometimes met there with hostility. But with United Nations support, refugee camps were established in these Southeast Asian countries to house and process the refugees. Ultimately, some 2,500,000 refugees were resettled, mostly in North America and Europe.

The communist revolutions triumphed in Indochina: in April 1975 in Vietnam and Cambodia, and in December 1975 in Laos. Because the United States used massive air firepower in the conflicts, North Vietnam, eastern Laos, and eastern Cambodia were heavily bombed. U.S. planes dropped nearly 8 million tons of bombs (twice the amount the United States dropped in World War II), and Indochina became the most heavily bombed area in history. Some 30% of the 270 million

so-called cluster bombs dropped did not explode, and since the end of the war, they continue to pose a grave danger to the local population, particularly in the countryside. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) has killed some 50,000 people in Laos alone, and hundreds more in Indochina are killed or maimed each year.

The aerial spraying operations of the U.S. military, carried out using several types of herbicides but most commonly with Agent Orange (which contained the highly toxic chemical, dioxin), have had a direct impact

on Vietnam. Some 400,000 were directly killed or maimed, and in the following years, a segment of the population that were exposed to the chemicals suffer from a variety of health problems, including cancers, birth defects, genetic and mental diseases, etc.

Some 20 million gallons of herbicides were sprayed on 20,000 km2 of forests, or 20% of Vietnam’s total forested area, which destroyed trees, hastened erosion, and upset the ecological balance, food chain, and other environmental parameters.

Following the Vietnam War, Indochina

continued to experience severe turmoil. In December 1978, after a period of border battles and cross-border raids, Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia