Daniel Orr's Blog, page 127

July 28, 2019

July 28, 1915 – U.S. forces land at Port-au-Prince, starting a 19-year occupation of Haiti

(Taken from United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915 – 1934 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

On July 28, 1915, Haitian President Vibrun Sam, an ally of the United States, was killed in a riot that broke out after he ordered the execution of his political enemies. Pandemonium broke out in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, where anti-American elements led by Rosalvo Bobo moved to take control of the government. Declaring the need to protect American citizens and American commercial interests in Haiti, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson acted swiftly, and U.S. Marines were landed in Port-au-Prince. After some fighting, the U.S. forces expelled the anti-American militia from the capital.

The island of Hispaniola consists of two separate nations: French and French-Creole speaking Haiti to the west and Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic to the east.

The island of Hispaniola consists of two separate nations: French and French-Creole speaking Haiti to the west and Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic to the east.The American intervention began a 19-year occupation of Haiti, prompted by the U.S. government’s determination to bring about

stability in the Caribbean country and ensure that Haiti repaid the loan. Under U.S. pressure, a pro-American government, led by President Sudre Dartiguenave, was installed in August 1915, which held only limited authority. The two countries signed a bilateral treaty, whereby Haiti practically became a U.S. protectorate, as the Caribbean country’s political, judicial, military, and economic policies came under the authority of first, the U.S. occupation force, and later by the American High Commissioner’s Office, which was set up by the U.S. government. The United States took control of Haiti’s treasury, customs, banking, and other revenue-generating agencies, and persuaded the Haitian government to pass laws that made Haiti pay back its foreign loans,

especially to those from American and French creditors.

History of Haiti Haiti, a country that occupies one-third and the western section of Hispaniola Island in the Caribbean Sea, gained its independence in 1804 when black African plantation slaves rebelled and overthrew their French colonial masters, and then established their own government. Thereafter for the rest of the 1800s, Haiti experienced political instability and social unrest because of its weak governmental, security, and economic infrastructures, with successive governments being deposed as a result of coups, revolts, and civil wars.

Largely because of a massive foreign debt, particularly to France, Haiti constantly experienced

economic difficulties. In the post-war agreement signed between Haiti and France in 1824, France promised not to invade Haiti, and recognized Haiti’s independence. In return, Haiti promised to pay France a large indemnity, which became a heavy monetary load that crippled Haiti’s economy.

By the early 1900s, German Haitians (ethnic Germans who had immigrated to Haiti) had

established large businesses in Haiti, gaining control of the local economy that once was dominated by the

French. The Germans had succeeded because many of them had married with Haiti’s mulatto elite, allowing them to join the ranks of local power and influence, as well as acquire the right to own Haitian land (which legally was forbidden to foreigners).

Background of U.S. Intervention in Haiti Haiti’s political instability continued into the early twentieth century – seven governments changed hands violently between 1911 and 1915. The United States viewed the Haitian situation with great concern, as Haiti was located fairly close to the Panama Canal, on which the U.S. government had invested a large amount of money to complete and which provided not only a substantial economic benefit to the Americans but also served as a vital strategic and military asset.

U.S. foreign policy at this time was based on the Monroe Doctrine*, which was aimed at deterring European involvement in the Western Hemisphere. In Haiti, the U.S. government looked with disfavor at the strong German and French diplomatic and economic influences. But of particular concern for the United States in 1915 were the German Haitians, as World War I had broken out in Europe and Germany had taken the initiative early in the war.

The United States believed that Germany might intervene in Haiti’s political instability in order to protect German commercial interests. The American concern was increased when German Haitians made such a request for intervention to the German government. For the United States, a German military presence in Haiti would threaten American interests in the Caribbean region, particularly with

regard to the Panama Canal.

Historically, the U.S. response to Haiti’s instability was to launch a direct military intervention: between 1876 and 1913, the American government sent troops to Haiti a total of 15 times during periods of unrest. In 1891, the United States had failed to persuade the Haitian government to allow the U.S.

military to construct a naval base in Haiti. Nevertheless, the U.S. Navy kept a permanent watch of the waters off Haiti, which was part of American policy to maintain political and military control of

the whole Central American and Caribbean regions.

In 1910, the United States loaned out a large amount of money to Haiti to help pay down the Caribbean country’s large foreign debt. The U.S.

government, therefore, had its commitments, as well as its stakes, raised in Haiti. In 1914, Haiti rejected American attempts to impose more economic measures. Consequently, the United States withdrew $500 million of Haiti’s foreign reserves and transferred that amount to New York for safekeeping. The United States also gained control of Haiti’s National Bank.

July 27, 2019

July 27, 1953 – Korean War: An armistice is agreed, which ends fighting

On July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement, which ended fighting in the Korean War which had begun on June 25, 1950. South Korea, led by president Syngman Rhee, refused to sign but promised to observe the armistice agreement. President Rhee was determined to reunify Korea under his rule and wanted the UN Command to force an all-out war against China, even at the risk of provoking the Soviet Union into entering the conflict on the side of North Korea. As such, he strongly opposed the armistice negotiations and even demanded that UN troops withdraw from South Korea to allow only his forces to continue the war.

Meanwhile, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung had also desired Korean unification under his authority. But after armistice negotiations commenced, he was prevailed upon by his backers China and the Soviet Union to tone down his hard-line stance. He subsequently changed his motto of “drive the enemy into the sea” to “drive the enemy to the 38th parallel.”

North Korea and South Korea in East Asia.

North Korea and South Korea in East Asia.(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath of the Korean War Meanwhile, armistice talks resumed, which culminated in an agreement on July 19, 1953. Eight days later, July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement, which ended the war. A ceasefire came into effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldiers killed, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; North Korean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which included Chairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying).

Civilian casualties were 2 million for South Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Korean refugees who had moved to South Korea. Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forces conducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to be supporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea, during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militias executed some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupation of South Korea, also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries” (politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians who refused to join the North Korean Army.

Under the armistice agreement, the frontline at the time of the ceasefire became the armistice line, which extended from coast to coast some 40 miles north of the 38th parallel in the east, to 20 miles south of the 38th parallel in the west, or a net territorial loss of 1,500 square miles to North Korea. Three days after the agreement was signed, both sides withdrew to a distance of two kilometers from

the ceasefire line, thus creating a four-kilometer demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the opposing forces.

The armistice agreement also stipulated the repatriation of POWs, a major point of contention during the talks, where both parties compromised and agreed to the formation of an independent body, the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission (NNRC), to implement the exchange of prisoners. The NNRC, chaired by General K.S. Thimayya

from India, subsequently launched Operation Big Switch, where in August-December 1953, some 70,000 North Korean and 5,500 Chinese POWs, and

12,700 UN POWs (including 7,800 South Koreans, 3,600 Americans, and 900 British), were repatriated. Some 22,000 Chinese/North Korean POWs refused to be repatriated – the 14,000 Chinese prisoners who refused repatriation eventually moved to the Republic of China (Taiwan), where they were given civilian status.

Much to the astonishment of U.S. and British authorities, 21 American and 1 British (together with 325 South Korean) POWs also refused to be repatriated, and chose to move to China. All POWs on both sides who refused to be repatriated were given 90 days to change their minds, as required under the armistice agreement.

The armistice line was conceived only as a separation of forces, and not as an international border between the two Korean states. The Korean Armistice Agreement called on the two rival Korean governments to negotiate a peaceful resolution to reunify the Korean Peninsula. In the international Geneva Conference held in April-July 1954, which aimed to achieve a political settlement to the recent

war in Korea (as well as in Indochina, see First Indochina War, separate article), North Korea and South Korea, backed by their major power sponsors,

each proposed a political settlement, but which was unacceptable to the other side. As a result, by the end of the Geneva Conference on June 15, 1953, no resolution was adopted, leaving the

Korean issue unresolved.

Since then, the Korean Peninsula has remained divided along the 1953 armistice line, with the 248-kilometer long DMZ, which was originally meant to be a military buffer zone, becoming the de facto border between North Korea and South Korea. No peace treaty was signed, with the armistice agreement being a ceasefire only. Thus, a state of war officially continues to exist between the two Koreas. Also as stipulated by the Korean Armistice

Agreement, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) was established, comprising contingents from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland, tasked with ensuring that no new foreign military personnel and weapons are brought into Korea.

Because of the constant state of high tension between the two Korean states, the DMZ has since remained heavily defended and is the most militarily fortified place on Earth. Situated at the armistice line in Panmunjom is the Joint Security Area, a conference center where representatives from the two Koreas hold negotiations periodically. Since the end of the

Korean War, there exists the constant threat of a new war, which is exacerbated by the many incidents initiated by North Korea against South Korea. Some of these incidents include: the hijacking by a North Korean agent of a South Korean commercial airliner in

December 1969; the North Korean abductions of South Korean civilians; the failed assassination attempt by North Korean commandos of South Korean President Park Chung-hee in January 1968; the sinking of a South Korean naval vessel, the ROKS Cheonon, in March 2010, which the South Korean government blamed was caused by a torpedo fired by a North Korean submarine (North Korea

denied any involvement), and the discovery of a number of underground tunnels along the DMZ which South Korea has said were built by North Korea to be used as an invasion route to the south.

Furthermore, in October 2006, North Korea announced that it had detonated its first nuclear bomb, and has since stated that it possesses

nuclear weapons. With North Korea aggressively pursuing its nuclear weapons capability, as evidenced by a number of nuclear tests being carried out over the years, the peninsular crisis has threatened to expand to regional and even global dimensions.

Western observers also believe that North Korea has since been developing chemical and biological weapons.

July 26, 2019

July 26, 1953 – Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro leads an attack on the Moncada Barracks, sparking the revolution

On July 26, 1953, Fidel Castro led over 160 armed followers, which included his brother Raul, in an attack on the army garrisons in Santiago de Cuba and Bayamo, both located at the southeast section of the island. The plan called for seizing weapons from the garrisons’ armories and then arming the local civilian population to incite a general uprising. The attack was foiled by the military, however, with the Castro brothers and many other rebels being captured, imprisoned, and subsequently charged for treason. Three months later, on October 16, the Castro brothers were handed down long prison terms, together with their followers who were given shorter prison sentences. The trials gained national attention, with Fidel Castro, who acted as his own defense attorney, gaining wide public recognition. While serving time in prison, Fidel renamed his organization the “26th of July Movement” or M-26-7 (Spanish: Movimiento 26 de Julio), in reference to the date of the failed attacks.

Fidel Castro was a student leader who previously had taken part in the aborted overthrow of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo and in the 1948 civil disturbance (known as “Bogotazo”) in Bogota, Colombia before completing his law studies at the University of Havana. He then run as an independent for Congress in the 1952 elections that were cancelled because of Batista’s coup. Castro was outraged and began making preparations to overthrow what he declared was the illegitimate Batista regime that had seized power from a democratically elected government. Fidel organized an armed insurgent group, “The Movement”, whose aim was to overthrow President Batista. At its peak, “The Movement” would comprise 1,200 members in its civilian and military wings.

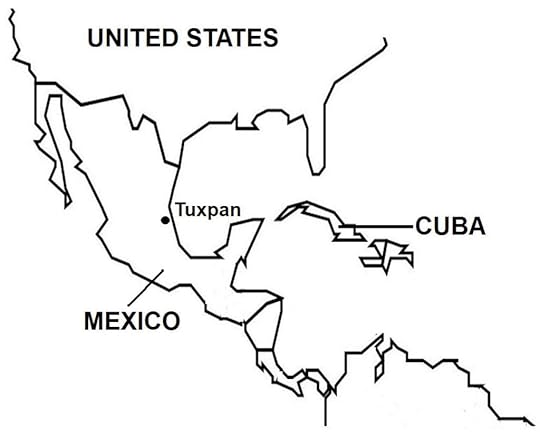

In November 1956, Fidel Castro and 81 other rebels set out from Tuxpan, Mexico aboard a decrepit yacht for their nearly 2,000 kilometer trip across the Caribbean Sea bound for south-eastern Cuba.

In November 1956, Fidel Castro and 81 other rebels set out from Tuxpan, Mexico aboard a decrepit yacht for their nearly 2,000 kilometer trip across the Caribbean Sea bound for south-eastern Cuba.(Taken from Cuban Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Aftermath of the Cuban Revolution In Havana, President Manuel Urrutia (who Castro had appointed as provisional president and Cuba’s new head of state), and especially Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and the M-26-7 fighters, took control of civilian and military institutions of the government. Similarly in Oriente Province, Fidel Castro established authority over the regional governmental and military functions. In the following days, other regional military units all across Cuba surrendered their jurisdictions to rebel forces that arrived. Then from Santiago de Cuba, Fidel Castro began a nearly week-long journey to Havana, stopping at every town and city to large crowds and giving speeches, interviews, and press conferences. On January 8, 1959, he arrived in Havana and declared himself the “Representative of the Rebel Armed Forces of the Presidency”, that is, he was effectively head of the Cuban Armed Forces under the government of President Urrutia and newly installed Prime Minister Jose Miro. Real power, however, remained with Castro.

In the next few months, the Castro regime consolidated power by executing or jailing hundreds of Batista supporters for “war crimes” and relegating to the sidelines the other rebel groups that had taken part in the revolution. During the war, Fidel Castro

had promised the return of democracy by instituting multi-party politics and holding free elections. Now however, he spurned these promises, declaring that the electoral process was socially regressive and benefited only the wealthy elite.

Castro denied being a communist, the most widely publicized declaration being during his personal visit to the United States in April 1959, or

four months after he gained power. Members of the Popular Socialist Party, or PSP (Cuban communists),

however, soon began to dominate key government positions, and Cuba’s foreign policy moved toward establishing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries. (By 1961

when Castro had declared Cuba a communist state, his M-26-7 Movement had formed an alliance with the PSP, the 13th of March Movement – DR, and other leftist organizations; this coalition ultimately gave rise to the Cuban Communist Party.)

President Urrutia, who was a political moderate and a non-communist, made known his concern about the socialist direction of the government, which put him directly in Castro’s way. Consequently in July 1959, President Urrutia was forced to resign from office, as Prime Minister Miro had done earlier in February. A Cuban communist took over as the new president, subservient to the dictates of Fidel Castro. Castro had become the “Maximum Leader”

(Spanish: Maximo Lider), or absolute dictator; he abolished Congress, ruled by decree, and suppressed all forms of opposition. Free speech was silenced, as were the print and broadcast media, which were placed under government control. In the villages, towns, and cities across Cuba, neighborhood watches called the “Committees for the Defense of the Revolution” were formed to monitor the activities of all residents within their jurisdictions and to weed out

dissidents, enemies, and “counter-revolutionaries”. In 1959, land reform was implemented in Cuba; private and corporate lands were seized, partitioned, and distributed to peasants and landless farmers.

On January 7, 1959, just a few days after the Cuban Revolution ended, the United States recognized the new Cuban government under President Urrutia. But as Castro later gained absolute power and his government gradually turned socialist, relations between the two countries deteriorated rapidly. By July 1959, just seven months later, U.S.

president Dwight Eisenhower was planning Castro’s overthrow; subsequently in March 1960, he ordered the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to organize and

train U.S.-based Cuban exiles for an invasion of Cuba.

In 1960, Castro entered into a trade agreement with the Soviet Union that included purchasing Russian oil. Then when U.S. petroleum companies in Cuba refused to refine the imported Russian oil, a succession of measures and retaliatory counter measures followed quickly. In July 1960, Cuba

seized the American oil companies and nationalized them the next month. In October 1960, the United States imposed an economic embargo on Cuba and banned all imports (which constituted 90% of all Cuban exports) from Cuba. The restriction included sugar, which was Cuba’s biggest source of revenue. In January 1960, the United States ended all official diplomatic relations with Cuba, closed its embassy in Havana, and banned trade to and forbid American private and business transactions with the island country.

With Cuba shedding off democracy and taking on a clearly communist state policy, thousands of Cubans from the upper and middle classes, including politicians, top government officials, businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and many other professionals fled the country for exile in other countries, particularly in

the United States. However, many other anti-Castro Cubans chose to remain and subsequently organized into armed groups to start a counter-revolution in the Escambray Mountains; these rebel groups’ activities laid the groundwork for Cuba’s next internal conflict, the “War against the Bandits”.

July 25, 2019

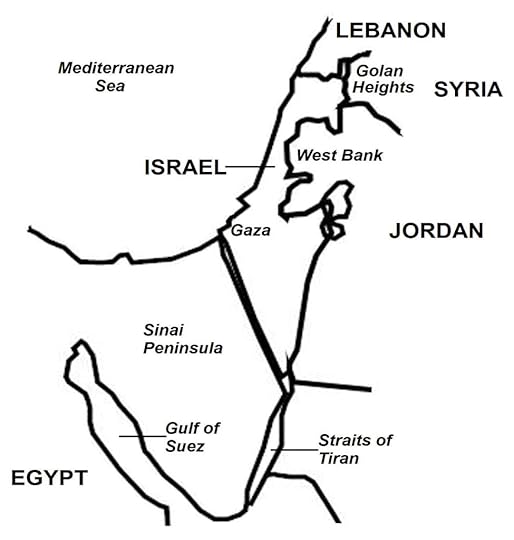

July 25, 1979 – Arab-Israeli Wars: Israel returns a section of the Sinai Peninsula

On July 25, 1979, Israel returned to Egypt a section of the Sinai Peninsula following the signing of a peace treaty between the two countries on March 26, 1979. In the treaty, Israel agreed to gradually withdraw its forces from the Sinai, which it subsequently completed in 1982. A peacekeeping force, the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) comprising contingents from many countries, entered the territory to ensure compliance with the treaty’s provisions. The treaty greatly advanced diplomatic relations between Egypt and Israel, which continues to this day.

Israel gained control of the Sinai during the Six-Day War in June 1967. Egypt attempted to recapture the Sinai during the Yom Kippur War in October 1973. Following a ceasefire following the second war, the two sides opened negotiations that led to the Sinai Interim Agreement in September 1975 where a buffer zone was established between the opposing forces. The two countries also agreed to eschew the use of force, and resolve their disagreements through peaceful means.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background With its decisive victory in the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights were integral territories of Egypt and Syria, respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, together with other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”, that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant that only armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently was not received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egypt carried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and government targets in the Sinai. In what is now known as the “War of Attrition”, Egypt was determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai. By way of retaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel, and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly became involved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israel and Egypt

to agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passed away. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President Anwar

Sadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchly hostile to Israel, President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeli conflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations (UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign a peace treaty with Israel and recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to negotiate. President Sadat, therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging the Israelis from the Sinai. He decided that an Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israel to see the need for negotiations. Egypt began preparations for war. Large amounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, but ineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number of ruses. The Egyptian Army constantly

conducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoric eventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the true strength of its armed forces. The government also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its war equipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated military

hardware. Furthermore, when President Sadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egypt in July 1972, Israel believed that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakened seriously. In fact, thousands of Soviet personnel remained in Egypt

and Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive.

Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syrian counterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized for war.

Israel’s intelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the date of the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbers of Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egypt and Syria attacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiers and the entire Israeli Air Force.

However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting a war and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carrying out a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War) to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur (which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, when most Israeli soldiers were on leave.