Daniel Orr's Blog, page 123

September 7, 2019

September 7, 1940 – World War II: German planes launch concentrated bombings of British city centers

On September 7, 1940, in what the British called the “Blitz”, the German Luftwaffe began a series of concentrated attacks of British urban centers,

launching 600 bombers and 400 fighters that came in successive bombing waves on the center of London.

Large-scale Luftwaffe bombing attacks continued for the next several weeks, hitting residential, industrial, and military targets and public works facilities in many major centers across Britain, including Bristol, Cardiff, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Southampton, Swansea, Birmingham, Belfast, Coventry, Glasgow, Manchester, and Sheffield. Some 40,000 civilians were killed, and 50,000 wounded, while one million

houses were destroyed or damaged.

On September 15, 1940, in what is known as the “Battle of Britain Day”, a combined 1,700 planes (1,100 Luftwaffe and 600 RAF) fought a day-long air battle in the skies over London, in what Goering hoped would be the ultimate destruction of the RAF. By then, the constant German pressure during Alderagriff (since August 24) had greatly strained RAF strength of No. 11 Group (which was tasked to defend southeast England, including London), but

the sudden shift in Luftwaffe concentration toward the cities allowed the RAF a respite. Also at this time, a crisis within the RAF was reaching the breaking

point, as Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, commander of RAF No. 12 Group (for southwest England), criticized Air Chief Marshal Dowding’s conduct of the air campaign, particularly the use of small RAF units to meet the massive German fleets. Leigh-Mallory, like many senior RAF commanders, favored large formations (per the “Big Wing” strategy) to meet the Luftwaffe in pitched air battles. As a

result, Downing was dismissed as commander of RAF Fighter Command.

Despite No. 11 Group’s losses, the RAF over-all was nowhere near collapse, for in fact, British aircraft production, as were the other war-related industries, was growing. Furthermore, the air battles, fought in British territory, gave the RAF considerable advantages: downed RAF pilots who had parachuted to safety were quickly sent up to fight again in another plane, while RAF planes were near their fuel, supply, and communication lines. The Luftwaffe fought against tremendous odds: downed pilots and air crews on land faced certain capture, or worse, lynching by angry mobs, and those on the sea, death by drowning or exposure to the elements; and Luftwaffe planes operated far from fuel and logistical lines, e.g. the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter plane, which functioned as a bomber escort, had only ten minutes of flying time left upon arriving in Britain, and after which it had to turn back for Germany, leaving the bombers undefended from RAF interceptors.

On September 17, 1940, with mounting Luftwaffe losses and the RAF clearly not verging on collapse, Hitler acknowledged before the German

High Command that the German air effort in Britain would probably not succeed, and gave instructions that preparations for Operation Sea Lion be scaled

back. Nevertheless, Hitler stated that the air attacks on Britain must continue, as ending the campaign would be an admission of defeat, and that they were to be used as a cover for the fact that the German military had begun preparing (since August 1940) for its most ambitious operation of all, the conquest of the Soviet Union.

By October 1940, the “weather window” for the invasion of Britain had closed, as German planning had taken into account that the onset of bad weather over the English Channel would greatly impede a cross-channel naval operation. On October 13, Hitler pushed back Operation Sea Lion to the spring of 1941. The air offensive continued, although by November 1940, the Luftwaffe shifted to nighttime attacks, as daylight operations were taking a heavy toll on men and aircraft. Official British historiography points to October 31, 1940 as the date that the Battle of Britain ended, although German air attacks would continue for many more months, sometimes with great intensity particularly in October-December 1940 and even well into early May 1941. But by spring of 1941, Hitler’s attention had invariably turned to other theaters of the war,

first to the Balkans with the invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece both in April 1941, and then to his greatest ambition of all, the conquest of the Soviet

Union (Operation Barbarossa), set for June 1941. In the process, the bulk of the Luftwaffe was moved to the east, greatly easing the pressure off Britain.

(Taken from Battle of Britain – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Aftermath In the

Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe sustained some 2,600 airmen killed, wounded, or captured, and 1,700 planes destroyed or damaged (comprising 40% of the

entire fleet). While German aircraft production continued, this considerable loss of men and aircraft meant fewer Luftwaffe resources for Operation Barbarossa. At the end of hostilities in May 1941, Hitler continued to believe that Britain was effectively knocked out of the European war and posed no serious threat on the continent. However, leaving Britain unconquered turned out to be one of Hitler’s great strategic mistakes. With German military resources soon directed at the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, Britain recovered and grew militarily. Then with the United States entering the war on the British side in December 1941, and in alliance with the other Allied partners, the British as part of the Allied force would return to the continent in June 1944.

Contemporary thinking at the time attributed British success against the Luftwaffe to the RAF fighter pilots in their Hawker Hurricanes and

Supermarine Spitfires, a depiction embodied in Churchill’s words, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few”. Only in the post-World War II period was it

revealed the critical role played by the ultra-secret Dowding system, which was known only to very few top-level officials in government and the military. The counter-argument is that while RAF No. 11 Group had been mauled during Operation Alderangriff, suffering heavy losses in men and planes, and many destroyed airfields and supporting infrastructures,

the other RAF Groups (10, 12, and 13) remained powerful, and production of aircraft continued.

September 5, 2019

September 6, 1965 – Indian-Pakistani War of 1965: Indian forces attack Pakistan Punjab, opening a new front

On September 6, 1965, Indian forces opened a new front by attacking Pakistan Punjab in the Indian-Pakistani War of 1965. The attack was launched to ease pressure on the lightly defended Indian-controlled Kashmir which was under threat from a powerful Pakistan armoured, air, and infantry offensive that had begun on September 1. Its flank threatened by the Indian counterattack, the Pakistani Army stopped its advance in Kashmir to divert forces to the new front.

Armed clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces at Rann of Kutch in April 1965 were a precursor to a full-scale war in Kashmir five months later.

Armed clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces at Rann of Kutch in April 1965 were a precursor to a full-scale war in Kashmir five months later.(Taken from Indian-Pakistani War of 1965 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background As a result of the Indian-Pakistani War of 1947 (previous article), the former Princely State of Kashmir was divided militarily under zones of occupation by the Indian Army and the Pakistani Army. Consequently, the governments of India and Pakistan established local administrations in their respective zones of control, these areas ultimately becoming de facto territories of their respective countries. However, Pakistan was determined to drive away the Indians from Kashmir and annex the whole region. As Pakistan and Kashmir had predominantly Muslim populations, the Pakistani government believed that Kashmiris detested being under Indian rule and would welcome and support an invasion by Pakistan. Furthermore, Pakistan’s government received reports that civilian protests in Kashmir indicated that Kashmiris were ready to revolt against the Indian regional government.

The Pakistani Army believed itself superior to its Indian counterpart. In early 1965, armed clashes broke out in disputed territory in the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat State, India (Map 3). Subsequently in 1968, Pakistan was awarded 350 square miles of the territory by the International Court of Justice. In 1965, India was still smarting from a defeat to China in the 1962 Sino-Indian War; as a result, Pakistan

believed that the Indian Army’s morale was low.

Furthermore, Pakistan had upgraded its Armed Forces with purchases of modern weapons from the United States, while India was yet in the midst of modernizing its military forces.

In the summer of 1965, Pakistan made preparations for invading Indian-held Kashmir. To assist the operation, Pakistani commandos would penetrate Kashmir’s major urban areas, carry out sabotage operations against military installations and public infrastructures, and distribute firearms to civilians in order to incite a revolt. Pakistani military planners believed that Pakistan would have greater bargaining power with the presence of a civilian uprising, in case the war went to international arbitration.

War On August 5, 1965 and

the days that followed, some 30,000 Pakistani soldiers posing as civilians crossed the ceasefire line (the de facto border resulting from the 1947 Indian-Pakistani War) and entered Indian-held Kashmir. The Pakistani infiltrators carried out some sabotage activities but failed to incite a general civilian uprising. The Indian Army, tipped off by informers, crushed the operation, killing many

Pakistani infiltrators and forcing others to flee back to Pakistan.

Then on August 15, the Indian forces crossed the western ceasefire line and entered Pakistani-held Kashmir. The offensive made considerable progress

until it was slowed at Tithwail and Pooch, upon the arrival of Pakistani Army reinforcements. By month’s end, the battle lines had settled (Map 4).

The Indian Army cut off all escape routes for the remaining Pakistani commandos in Kashmir. In order to take the pressure off the trapped commandos, the Pakistani Army carried out an offensive aimed at Jammu. On September 1, in what became the first of

many large tank and air battles of the war, Pakistan

opened a combined armored and air attack on the town of Akhnoor. The capture of Akhnoor would cut India’s communications and supply lines between Kashmir and the rest of the country. Furthermore, Jammu, which was India’s logistical base in Kashmir,

would come under direct threat. The surprise and strength of the offensive caught the Indian Army off-guard, allowing the Pakistanis to win territory.

However, the Pakistani Army stopped before reaching its objectives and made a command change to the operation. The delay allowed the Indian Army to regroup and mount a strong defense. When the Pakistani forces restarted their offensive, they were stopped decisively near Akhnoor.

September 4, 2019

September 5, 1957 – Cuban Revolution: Dictator Fulgencio Batista quells the Cienfuegos Mutiny

On September 5, 1957, Cuban President Fulgencio Batista violently quelled a revolt by junior Navy officers at Cienfuegos, a city located at the south central coast of the island. The revolt came after President Batista appointed certain officers to high-ranking Navy positions The leader of the mutiny also supported Fidel Castro’s ongoing rebellion to overthrow the national government (Cuban Revolution). President Batista used the army and air force to crush the Cienfuegos Mutiny, inflicting some 300 fatalities across the city and forcing some of the mutineers to flee to the Escambray Mountains, where they reorganized as another branch of the M-26-7, Fidel Castro’s insurgent organization.

( Cuban Revolution – Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

By early 1958, Castro’s insurgency was destabilizing Oriente Province, especially in the rural areas which had come under the control or influence of the rebels. Furthermore, four other anti-Batista armed groups operated in the province, spreading thin the operational capability of the Cuban Army. Other insurgencies also had emerged in Camaguey and Pinar del Rio Provinces, as well as in the Escambray Mountains.

In February1958, Fidel Castro sent a contingent led by his brother Raul to the Sierra Cristal Mountains, located in northeastern Oriente Province, where the M-26-7 subsequently opened a second front. On April 1, 1958, Fidel Castro declared total war against President Batista, which was a largely propaganda move that was ignored by the other

rebel groups, but underscored the supremacy of the M-26-7 in the Cuban revolution.

Background of the Cuban Revolution

In March 1952, General Fulgencio Batista seized power in Cuba through a coup d’état. He then canceled the elections scheduled for June 1952, where he was running for the presidency but trailed in the polls and faced likely defeat. Having gained power, General Batista established a dictatorship, suppressed the opposition, and suspended the

constitution and many civil liberties. Then in the November 1954 general elections that were boycotted by the political opposition, General Batista won the presidency and thus became Cuba’s official

head of state.

President Batista favored a close working relationship with Cuba’s wealthy elite, particularly with American businesses, which had an established, dominating presence in Cuba. Since the early twentieth century, the United States had maintained political, economic, and military control over Cuba; e.g.during the first few decades of the 1900s, U.S. forces often intervened directly in Cuba by quelling unrest and violence, and restoring political order.

American corporations held a monopoly on the Cuban economy, dominating the production and commercial trade of the island’s main export, sugar, as well as other agricultural products, the mining and petroleum industries, and public utilities. The United States naturally entered into political, economic, and military alliances with and backed the Cuban government; in the context of the Cold War, successive Cuban governments after World War II were anti-communist and staunchly pro-American.

President Batista expanded the businesses of the American mafia in Cuba, where these criminal organizations built and operated racetracks, casinos, nightclubs, and hotels in Havana with relaxed tax laws provided by the Cuban government. President Batista amassed a large personal fortune from these transactions, and Havana was transformed into and became internationally known for its red-light

district, where gambling, prostitution, and illegal drugs were rampant. President Batista’s regime was characterized by widespread corruption, as public officials and the police benefitted from bribes from the American crime syndicates as well as from outright embezzlement of government funds.

Cuba did achieve consistently high economic growth under President Batista, but much of the wealth was concentrated in the upper class, and a great divide existed between the small, wealthy elite and the masses of the urban poor and landless

peasants. (Cuban society also contained a relatively dynamic middle class that included doctors, lawyers, and many other working professionals.)

President Batista was extremely unpopular among the general population, because he had gained power through force and made unequal economic policies. As a result, Havana (Cuba’s

capital) seethed with discontent, with street demonstrations, protests, and riots occurring frequently. In response, President Batista deployed security forces to suppress dissenting elements,

particularly those that advocated Marxist ideology. The government’s secret police regularly

carried out extrajudicial executions and forced disappearances, as well as arbitrary arrests, detentions, and tortures. Some 20,000 persons were killed or disappeared during the Batista regime.

In 1953, a young lawyer and former student leader named Fidel Castro emerged to lead what ultimately would be the most serious challenge

to President Batista. Castro previously had taken part in the aborted overthrow of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo and in the 1948 civil

disturbance (known as “Bogotazo”) in Bogota, Colombia before completing his law studies at

the University of Havana. Castro had run as an independent for Congress in the 1952 elections that were cancelled because of Batista’s coup. Castro was infuriated and began making preparations to overthrow what he declared was the illegitimate Batista regime that had seized power from a democratically elected government. Fidel organized an armed insurgent group, “The Movement”, whose aim was to overthrow President Batista. At its peak, “The Movement” would comprise 1,200 members in its civilian and military wings.

September 4, 1919 – Turkish War of Independence: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk leads an assembly of Turkish nationalists at the Sivas Congress

On September 4, 1919, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and the Turkish National Movement met at Sivas in central-eastern Turkey to formulate policy for the preservation of unity, independence, and territorial integrity of the Turkish state. The week-long assembly (September 4-11, 1919) came in the heels of the preparatory Erzurum Congress. At this time, World War I had just ended and the defeated Ottoman Empire was supine and essentially defunct, and partitioned under military occupation by the Allied Powers: French, British, Italians, and Greeks.

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres(Taken from Turkish War of Independence in Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

As a result of this circular, Turkish nationalists met

twice: at the Erzerum Congress (July-August 1991) by regional leaders of the eastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September 1919) of nationalist

leaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from these meetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth the guidelines for the Turkish state, including what constituted the “homeland of the Turkish nation”, and that the “country should be independent and free, all restrictions on political, judicial, and financial developments will be removed”. The “Representative Committee” was the precursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3, 1920 as the Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara (in central Anatolia), founded and led by

Kemal.

Sykes-Picot Agreement

Sykes-Picot AgreementBackground of the Turkish War of Independence

On October 30, 1918, the Ottoman Empire ended its involvement in World War I by signing the Armistice of Mudros. During the war, the Ottoman government had fought as one of the Central Powers (in alliance with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria), but in 1917 and 1918, it suffered many devastating defeats. Then with the failure of the Germans’ 1918

“Spring Offensive” in Western Europe, the Anatolian heartland of the Ottoman Empire became vulnerable to an invasion, forcing Ottoman capitulation.

The victorious Allied Powers in Europe (Britain, France, and Italy) took steps to carry out their many secret pre-war and war-time agreements regarding the disposition of the Ottoman Empire. Another Allied power, Russia, also was a party to some of

these agreements, but it had been forced out of the war in 1914 and consequently was not involved in the post-war negotiations.

As a first measure and provided by the terms of surrender, the French and British naval fleets seized control of the Turkish Straits (Dardanelles and Bosporus) on November 12-13, 1913, and landed troops in Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire’s capital.

During World War I, British forces gained possession of much of the Ottoman Empire’s colonies in the Middle East, collectively called “Greater Syria”, a vast territory covering Mesopotamia (Iraq), the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Palestine. When the war ended, most of the Arabian Peninsula gained independence under British sponsorship, including the Kingdom of Yemen and later the Kingdom of Nejd and Hejaz, the precursor of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The most significant war-time treaty to be implemented in the Middle East was the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, where Britain and France

drew up a plan to partition between them most of the remaining Ottoman possessions, i.e. Syria and Lebanon to France, and Mesopotamia and Palestine to Britain*. As a result, following war’s end, Britain and France took control of their respective previously agreed territories in the Middle East. These annexations subsequently were legitimized as mandates by the newly formed League of Nations: i.e. the 1923 French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, and the 1923 British Mandate for Palestine. British control of Mesopotamia was formalized by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1922, which also established the Kingdom of Iraq.

The Allies also had drawn up a partition plan for Anatolia, the Turkish heartland of the Ottoman Empire. In this plan, Constantinople and the Turkish Straits were designated as a neutral zone under joint Allied administrations, with separate British, French, and Italian zones of occupations. Southwest Anatolia was allocated to Italy, the southeast (centered on Cilicia) to France, and a section of the northeast to Armenia. Greece, a late-comer in World War I on the Allied side, was promised the historic Hellenic region around Smyrna, as well as Eastern Thrace.

With these proposed changes, a much smaller Ottoman state would consist of central Anatolia up to the Black Sea, but no coastal outlet in the Mediterranean Sea. The Allies subsequently incorporated these stipulations in the 1920 Treaty of Sevres (Map 8), an agreement aimed at legitimizing their annexations/occupations of Ottoman territories.

The Allies wanted a breakup of the Ottomans’ centralized state, to be replaced by a decentralized federal form of government. In Constantinople,

the national government led by the Sultan and Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) were resigned to these political and territorial changes. However, Turkish nationalists, representing a political and ideological movement that became powerful in the early twentieth century, opposed the Allied impositions on Anatolia, perceiving them to be a deliberate dismembering of the Turkish traditional

homeland. As a result of the Allied occupation, many small Turkish nationalist armed resistance groups began to organize all across Anatolia.

Rise of the Turkish Independence Movement

Under the armistice agreement, the Ottoman government was required to disarm and demobilize its armed forces. On April 30, 1919, Mustafa Kemal, a general in the Ottoman Army, was appointed as the

Inspector-General of the Ottoman Ninth Army in Anatolia, with the task of demobilizing the remaining forces in the interior. Kemal was a nationalist who opposed the Allied occupation, and upon arriving in Samsun on May 19, 1919, he and other like-minded colleagues set up what became the Turkish Nationalist Movement.

Contact was made with other nationalist politicians and military officers, and alliances were formed with other nationalist organizations in Anatolia. Military units that were not yet demobilized, as well as the various armed bands and militias, were instructed to resist the occupation

forces. These various nationalist groups ultimately would merge to form the nationalists’ “National Army” in the coming war. Weapons and ammunitions were stockpiled, and those previously surrendered were secretly taken back and turned over to the nationalists.

On June 21, 1919, Kemal issued the Amasya Circular, which declared among other things, that the unity and independence of the Turkish

state were in danger, that the Ottoman government was incapable of defending the country, and that a national effort was needed to secure the state’s

integrity. As a result of this circular, Turkish nationalists met twice: at the Erzerum Congress (July-August 1991) by regional leaders of the eastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September

1919) of nationalist leaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from these

meetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth the guidelines for the Turkish state, including what constituted the “homeland of the Turkish nation”, and that the “country should be independent and free, all restrictions on political, judicial, and financial developments will be removed”. The “Representative Committee” was the precursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3, 1920 as the Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara

(in central Anatolia), founded and led by Kemal.

Kemal and his Representative Committee “government” challenged the continued legitimacy of the national government, declaring that Constantinople was ruled by the Allied Powers from whom the Sultan had to be liberated. However,

the Sultan condemned Kemal and the nationalists, since both the latter effectively had established a second government that was a rival to that in Constantinople.

In July 1919, Kemal received an order from the nationalauthorities to return to Constantinople. Fearing for his safety, he remained in Ankara; consequently, heceased all official duties with the Ottoman Army. The Ottoman government then laid down treasoncharges against Kemal and other nationalist leaders; tried in absentia, he was declared guilty on May 11, 1920 and sentenced to death.

Initially, British authorities played down the threat posedby the Turkish nationalists. Then when

the Ottoman parliament in Constantinople

declared its support for the nationalists’ National Pact and the integrity ofthe Turkish state, the British violently closed down the legislature, an action

that inflicted many civilian casualties. The next month, the Sultan affirmed the dissolution of the Ottoman parliament.

Many parliamentarians were arrested, but many others escaped capture and fled to Ankara to join the nationalists. On April 23, 1920, a new parliament called the Grand National Assembly convened in Ankara, which elected Kemal as its first president.

British authorities soon realized that the nationalist movement threatened the Allied plans on the Ottoman Empire. From civilian volunteers and units of the Sultan’s Caliphate Army, the British organized a militia, which was tasked to defeat the nationalist forces in Anatolia. Clashes soon broke out, with the most intense taking place in June 1920 in and around Izmit, where Ottoman and British forces defeated the nationalists. Defections were widespread among the Sultan’s forces, however, forcing the British to disband the militia.

The British then considered using their own troops, but backed down knowing that the British public would oppose Britain being involved in another

war, especially one coming right after World War I. The British soon found another ally to fight the war against the nationalists – Greece. On June 10, 1920, the Allies presented the Treaty of Sevres to the Sultan. The treaty was signed by the Ottoman government but was not ratified, since war already had broken out.

In the coming war, Kemal crucially gained the support of the newly established Soviet Union, particularly in the Caucasus where for centuries, the Russians and Ottomans had fought for domination. This Soviet-Turkish alliance resulted from both sides’ condemnation of the Allied intervention in their local affairs, i.e. the British and French enforcing the Treaty of Sevres on the Ottoman Empire, and the Allies’ open support for anti-Bolshevik forces in the Russian Civil War.

War Turkish nationalists fought in three fronts: in the east against Armenia, in the south against France and the French Armenian Legion, and in the west against Greece, which was backed by Britain.

September 3, 2019

September 3, 1939 – World War II: Britain and France blockade the German coastline, starting the Battle of the Atlantic

(Excerpts from Battle of the Atlantic (Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe))

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland; two days later, September 3, Britain and France declared war on Germany, starting World War II. On September 4, 1939, Britain imposed a naval blockade of German ports. Under the newly established British Contraband Control Service and French Blockade Ministry, the British Royal Navy and French Navy (Marine nationale) under over-all British command, imposed a blockade enforcement system where all ships passing European trade routes were required to stop for inspection at designated British ports (later expanded to include other British colonial ports along merchant routes in the Mediterranean Sea and Indian

Ocean). The ships’ cargoes were examined,

and items found in a broad list of designated contraband materials, which included ammunitions, explosives, and the like, but also even foodstuffs,

animal feed, and clothing, were subject to seizure. The Allies intended these measures to force Germany, which was deficient in natural resources and heavily dependent on importation of food and raw materials for its people, civilian industries, and war capability, to enter into peace negotiations, thus bringing the war to an end.

Instead, Germany imposed its own naval blockade of Britain which, as an island nation,

was also heavily dependent on importation of commodities in order to survive, as well as to continue the war. Germany’s aim was to starve Britain into submission. The German Navy’s attempt to stop the flow of materials to Britain

particularly from North America through the Atlantic Ocean, and the British efforts to foil the Germans constitute what is known as the Battle of the Atlantic.

By the time of the outbreak of World War II, the ambitious expansion program of the Kriegsmarine (the German Navy) under Plan Z aimed at achieving naval equality with the British Navy (the world’s largest fleet), was far from complete, and the small German fleet (by comparison) simply could not

engage in open battle either the British or French fleets, the latter two having much larger navies.

Instead, early in the war, the Kriegsmarine initiated a strategy of commerce raiding, where German surface ships (battleships, cruisers, destroyers, etc.) and submarines, which were called U-boats (from the German: Unterseeboot; “undersea boat”), were sent to the Atlantic Ocean to attack Allied and neutral-nation merchant vessels bound for Britain. The Germans also used a number of armed merchant vessels, which were disguised as neutral or Allied ships but manned by German Navy personnel, for commerce raiding. As well, later in the war, long-range Luftwaffe planes, particularly the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, were used for reconnaissance and attack missions.

The German heavy cruisers Deutschland and Admiral Graf

Spee, already in the Atlantic Ocean at the

outbreak of war, sank several Allied merchant ships. The Allies organized several hunting groups to locate these German ships, so straining their resources as the British and French allocated three battle cruisers, three aircraft carriers, fifteen cruisers, and many auxiliary ships to scour the Atlantic. But in December 1939, the Graf Spee was caught and trapped near the River Plate (Rio de la Plata), off the South American coast, and scuttled by its crew near Montevideo, Uruguay.

Despite this success, the early hunting-group strategy proved counter-productive, as the Allies then possessed inadequate technological resources to locate U-boats, whose strength lay in avoiding

detection by submerging underwater and remaining there until the danger passed. The U-boat’s other main asset was stealth, and the first naval casualty of the war, the British ocean liner, SS Athenia, was attacked and sunk by a

U-boat (which it mistook for a British warship) on September 3, 1939, with 128 lives lost. Also in September 1939 and just a few days apart, two British aircraft carriers, the HMS Ark Royal and HMS Courageous, were both attacked by a U-boat, with the former narrowly being hit by torpedoes, while the latter was hit and sunk. Then in October 1939, another U-boat

penetrated undetected near Scapa Flow, the

main British naval base, attacking and sinking the battleship, the HMS Royal Oak.

At the start of the war, the British military was

hard-pressed on how to deal with the U-boat threat. During the interwar period, prevailing naval thought and budgetary resources, both Allied and German alike, focused on surface ships, and the belief that battleships would play the dominant role in naval warfare in a future war. German U-boats had proved highly effective in World War I, causing heavy losses on merchant shipping that nearly forced Britain out of the war, before the British introduced the convoy system that turned fortunes around.

However, the British Navy’s implementing the ASDIC system (acronym for “Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee”; otherwise

known as SONAR), which could detect the presence of submerged submarines, appeared to have solved the U-boat threat. Naval tests showed that once detected by ASDIC, the submarine could then

be destroyed by two destroyers launching depth charges overboard continuously in a long diamond pattern around the trapped vessel. The British concept was that the U-boats could operate only in coastal waters to threaten harbor shipping, as they had done in World War I, and these tests were conducted under daylight and calm weather conditions. But by the outbreak of World War II, German submarine technology had rapidly advanced, and were continuing so, that U-boats were able to reach farther out into the Atlantic Ocean, eventually ranging as far as the American eastern seacoast, and also were able to submerge to greater depths beyond the capacity of depth charges. These factors would weigh heavily in the early stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

September 1, 2019

September 2, 1939 – World War II: Germany annexes Danzig

On September 2, 1939 one day after launching its invasion of Poland, Germany abolished the Free City of Danzig and annexed the territory into the Third Reich. The Free City of Danzig (present-day Gdansk, Poland) had been established in November 1920 by the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. The Free City comprised territory detached from pre-World War I Germany, including the Baltic port of Danzig and surrounding areas that included some 200 towns and villages. The Free City of Danzig was established to be neither German nor Polish territory, but a semi-autonomous entity administered by the League of Nations to allow newly independent Poland access to the Baltic Sea (the so-called “Polish Corridor”). As such, Poland was given rights to communication, railways, and port facilities in the Free City. Ethnic Germans comprised 98% of the Free City’s population.

(Taken from German Invasion of Poland – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background At the end of World War I, the Allies reconstituted Poland as a sovereign nation, incorporating into the new state portions of the eastern German territories of Pomerania and Silesia, which contained majority Polish populations. In the 1920s, the German Weimar Republic sought to restore to Germany all its lost territories, but was restrained by certain stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, which had been imposed on Germany after World War I. Polish Pomerania was known worldwide as the “Polish Corridor”, as it allowed Poland access to international waters through the Baltic Sea. The German city of Danzig in East Prussia, as well as nearby areas, also was detached from Germany, and renamed the “Free City of Danzig”, administered by the League of Nations, but whose port, customs, and public infrastructures were controlled by Poland.

In 1933, Hitler came to power and implemented Germany’s massive rearmament program, and later began to pursue his irredentist ambitions in earnest. Previously in January 1934, Nazi Germany and Poland had signed a ten-year non-aggression pact, where the German government recognized the territorial integrity of the Polish state, which included the German regions that had been ceded to Poland. But by the late 1930s, the now militarily powerful Germany was actively pushing to redefine the German-Polish border.

In October 1938, Germany proposed to Poland renewing their non-aggression treaty, but subject to two conditions: that Danzig be restored to Germany and that Germany be allowed to build road and railway lines through the Polish Corridor to connect Germany proper and East Prussia. Poland refused, and in April 1939, Hitler abolished the non-aggression pact. To Poland, Hitler was using the same aggressive tactics that he had used against Czechoslovakia, and that if it yielded to the German demands on Danzig and the Polish Corridor, ultimately the rest of Poland would be swallowed up by Germany.

Meanwhile, Britain and France, which had pursued appeasement toward Hitler, had become wary after the German occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia, which had a non-ethnic German majority population, which was in contrast to

what Hitler had said that he only wanted returned those German-populated territories. Britain and France were now determined to resist Germany

diplomatically and resolve the crisis through firm negotiations. On March 31, 1939, Britain

and France announced that they would “guarantee Polish independence” in case of foreign aggression. Since 1921, as per the Franco-Polish Military Alliance, France had pledged military assistance to Poland if that latter was attacked.

In fact, Hitler’s intentions on Poland was not only the return of lost German territories, but the elimination of the Polish state and annexation of Poland as part of Lebensraum (“living space”), German expansion into Eastern Europe and Russia. Lebensraum called for the eradication of the native populations in these conquered areas. For Poland

specifically, on August 22, 1939 in the lead-up to the German invasion, Hitler had said that “the object of the war is … to kill without pity or mercy all men, women, and children of Polish descent or language. Only in this way can we obtain the living space we need.” In April 1939, Hitler instructed the German military High Command to begin preparations for an

invasion of Poland, to be launched later in the summer. By May 1939, the German military had drawn up the invasion plan.

In May 1939, Britain and France held high-level

talks with the Soviet Union regarding forming a tripartite military alliance against Germany, especially

in light of the possible German invasion of Poland. These talks stalled, because Poland refused to allow Soviet forces into its territory in case Germany attacked. Unbeknown to Britain and France, the Soviet Union and Germany were also conducting (secret) separate talks regarding bilateral political,

military, and economic concerns, which on August 23, 1939, led to the signing of a non-aggression treaty. This treaty, which was broadcast to the world and widely known as the Molotov Ribbentrop Pact (named after Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop), brought a radical shift to the European power balance, as Germany was now free to invade Poland without fear of Soviet reprisal. The pact also included a secret protocol where Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania were divided into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

One day earlier, August 22, with the non- aggression treaty virtually assured, Hitler set the invasion date of Poland for August 26, 1939. On August 25, Hitler told the British ambassador that Britain must agree to the German demands on Poland, as the non-aggression pact freed Germany from facing a two-front war with major powers. But on that same day, Britain and Poland signed a mutual defense pact, which contained a secret clause where the British promised military assistance if Poland was attacked by Germany. This agreement, as well as British overtures that Britain and Poland were willing to restart the stalled talks with Germany, forced Hitler to abort the invasion set for the next day.

The Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) stood down, except for some units that did not receive the new stop order and crossed into Poland, skirmishing with the Poles. These German units soon withdrew back across the border, but the Polish High Command, informed through intelligence reports of massive German build-up at the border, was unaware that the border skirmishes were part of an aborted German invasion.

German negotiations with Britain and France

continued, but they failed to make progress. Poland had refused to negotiate on the basis of ceding territory, and its determination was strengthened by the military guarantees of the Western Powers, particularly in that if the Germans invaded, the British and French would attack from the west, and Germany

would be confronted with a two-front war.

On August 29, 1939, Germany sent Poland a set of proposals for negotiations, which included two points: that Danzig be returned to Germany and that a plebiscite be held in the Polish Corridor to determine whether the territory should remain with Poland or be returned to Germany. In the latter, Poles who were born or had settled in the Corridor since 1919 could not vote, while Germans born there but not living there could vote. Germany demanded that negotiations were subject to a Polish official with signing powers arriving by the following day, August 30.

Britain deemed that the German proposal was an ultimatum to Poland, and tried but failed to convince the Polish government to negotiate. On August 30, the German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop presented the British ambassador with a 16-point proposal for negotiations, but refused the latter’s request that a copy be sent to the Polish government, as no Polish

representative had arrived by the set date. The next day, August 31, the Polish Ambassador Jozef Lipski conferred with Ribbentrop, but as Lipski had no signing powers, the talks did not proceed. Later that day, Hitler announced that the German-Polish talks had ended because of Poland’s refusal to negotiate. He then ordered the German High Command to proceed with the invasion of Poland for the next day, September 1, 1939.

September 1, 1961 – Eritrean War of Independence: Eritrean nationalists attack Ethiopian police posts

On September 1, 1961, insurgents of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) stormed a number of police posts in western Eritrea, marking the start of the Eritrean War of Independence, a protracted conflict that would last three decades. The insurgents subsequently carried out more attacks against security forces. In the period that followed, the ELF gained local support in its areas of operations in the rural Muslim-populated rural northern and western regions of Eritrea and increased its numbers with the inflow of many new recruits. The rebels also increased their frequency of attacks against police targets, primarily to capture much-needed weapons. By June 1962, the ELF had some 500 fighters, which included some police defectors who took along their weapons and ammunitions. At this time, Muslims formed the vast majority of the ELF, which also advocated a pro-Muslim, pro-Arab ideological and religious struggle against the predominantly Christian Ethiopia. Also for this reason, the ELF gained some military and financial support from a number of Muslim countries, including Syria, Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan.

On May 24, 1991, Eritrea

gained its independence from Ethiopia

following a 30-year armed revolution. Ethiopia

had annexed Eritrea

as a province in November 1962, inciting Eritrean nationalists to launch a

rebellion. Following the war, as Eritrea was still legally bound as part of

Ethiopia, in early July 1991, at a conference held in Addis Ababa, an interim

Ethiopian government was formed, which stated that Eritreans had the right to

determine their own political future, i.e. to remain with or secede from Ethiopia.

Then in a UN-monitored referendum held in April 23 and 25,

1993, Eritreans voted overwhelmingly (99.8%) for independence; two days later

(April 27), Eritrea

declared its independence. In May 1993, the new country was admitted as a

member of the UN.

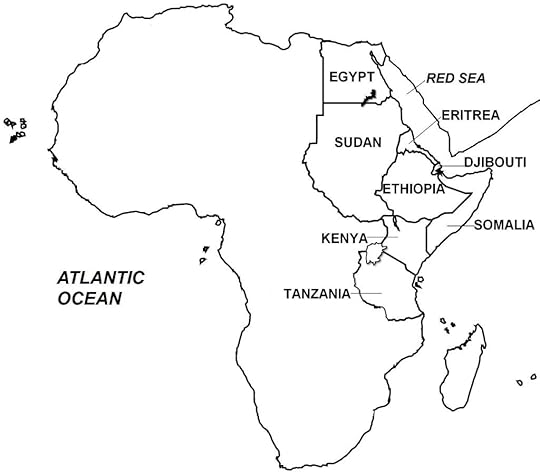

Eritrea, Ethiopia and nearby countries

Eritrea, Ethiopia and nearby countries(Taken from Eritrean War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In

September 1948, a special body called the Inquiry Commission, which was set up

by the Allied Powers (Britain,

France, Soviet Union, and United States),

failed to establish a future course for Eritrea and referred the matter to

the United Nations (UN). The main obstacle to granting Eritrea its independence was that for much of

its history, Eritrea

was not a single political sovereign entity but had been a part of and

subordinate to a greater colonial power, and as such, was deemed incapable of

surviving on its own as a fully independent state. Furthermore, various

countries put forth competing claims to Eritrea. Italy

wanted Eritrea returned, to

be governed for a pre-set period until the territory’s independence, an

arrangement that was similar to that of Italian Somaliland.

The Arab countries of the Middle East pressed for self-determination of Eritrea’s large Muslim population, and as such,

called for Eritrea

to be granted its independence. Britain,

as the current administrative power, wanted to partition Eritrea, with the Christian-population regions

to be incorporated into Ethiopia

and the Muslim regions to be assimilated into Sudan. Emperor Haile Selassie, the

Ethiopian monarch, also claimed ownership of Eritrea, citing historical and cultural

ties, as well as the need for Ethiopia to have access to the sea through the

Red Sea (Ethiopia had been landlocked after Italy established Eritrea).

Ultimately, the United States

influenced the future course for Eritrea. The U.S. government saw Eritrea

in the regional balance of power in Cold War politics: an independent but weak Eritrea could potentially fall to communist

(Soviet) domination, which would destabilize the vital oil-rich Middle East. Unbeknown to the general public at the time,

a U.S. diplomatic cable from

Ethiopia to the U.S. State

Department in August 1949 stated that British officials in Eritrea believed that as much as

75% of the local population desired independence.

In February 1950, a UN commission sent to Eritrea to

determine the local people’s political aspirations submitted its findings to

the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In December 1950, the UNGA, which

was strongly influenced by U.S.

wishes, released Resolution 390A (V) that called for establishing a loose federation

between Ethiopia and Eritrea to be facilitated by Britain and to be realized no later

than September 15, 1952. The UN plan, which subsequently was implemented,

allowed Eritrea

broad autonomy in controlling its internal affairs, including local administrative,

police, and fiscal and taxation functions. The Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation

would affirm the sovereignty of the Ethiopian monarch whose government would

exert jurisdiction over Eritrea’s

foreign affairs, including military defense, national finance, and transportation.

In March 1952, under British initiative, Eritrea elected

a 68-seat Representative Assembly, a legislature composed equally of Christians

and Muslim members, which subsequently adopted a constitution proposed by the

UN. Just days before the September 1952 deadline for federation, the Ethiopian

government ratified the Eritrean constitution and upheld Eritrea’s Representative Assembly

as the renamed Eritrean Assembly. On September 15, 1952, the Ethiopian-Eritrean

Federation was established, and Britain

turned over administration to the new authorities, and withdrew from Eritrea.

However, Emperor Haile Selassie was determined to bring Eritrea under Ethiopia’s full authority. Eritrea’s

head of government (called Chief Executive who was elected by the Eritrean

Assembly) was forced to resign, and successors to the post were appointed by

the Ethiopian emperor. Ethiopians were appointed to many high-level Eritrean

government posts. Many Eritrean political parties were banned and press censorship

was imposed. Amharic, Ethiopia’s

official language, was imposed, while Arabic and Tigrayan, Eritrea’s main languages, were

replaced with Amharic as the medium for education. Many local businesses were

moved to Ethiopia, while

local tax revenues were sent to Ethiopia.

By the early 1960s, Eritrea’s

autonomy status virtually had ceased to exist. In November 1962, the Eritrean

Assembly, under strong pressure from Emperor Haile Selassie, dissolved the

Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation and voted to incorporate Eritrea as Ethiopia’s

14th province.

Eritreans were outraged by these developments. Civilian

dissent in the form of rallies and demonstrations broke out, and was dealt with

harshly by Ethiopia,

causing scores of deaths and injuries among protesters in confrontations with

security forces. Opposition leaders, particularly those calling for

independence, were suppressed, forcing many to flee into exile abroad; scores

of their supporters also were jailed. In April 1958, the first organized

resistance to Ethiopian rule emerged with the formation of the clandestine

Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM), consisting originally of Eritrean exiles in

Sudan.

At its peak in Eritrea, the ELM had some 40,000 members who organized in cells

of 7 people and carried out a campaign of destabilization, including engaging

in some militant actions such as assassinating government officials, aimed at

forcing the Ethiopian government to reverse some of its centralizing policies

that were undercutting Eritrea’s autonomous status under the federated

arrangement with Ethiopia. By 1962, the government’s anti-dissident campaigns

had weakened the ELM, although the militant group continued to exist, albeit

with limited success. Also by 1962, another Eritrean nationalist organization,

the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), had emerged, having been organized in July

1960 by Eritrean exiles in Cairo, Egypt which in contrast to the ELM, had as

its objective the use of armed force to achieve Eritrean’s independence.

In its early years, the ELF leadership, called the “Supreme

Council”, operated out of Cairo

to more effectively spread its political goals to the international community

and to lobby and secure military support from foreign donors.

August 31, 2019

August 31, 1939 – World War II: German saboteurs seize the Gleiwitz radio station and air anti-German propaganda, giving Germany a pretext to invade Poland

In the lead-up to the war, German operatives launched a series of sabotage operations in German territory in the guise that these were

committed by Poles, in order to give Germany

a pretext to invade Poland. These actions, implemented under Operation Himmler, targeted railway stations, customs houses, communication lines, etc. As part of Operation Himmler, on the night of August 31, 1939, German saboteurs wearing Polish uniforms seized the Gleiwitz radio station in Silesia, Germany, and aired a short anti-German message in Polish. This and other supposed Polish provocations were used by Hitler to launch what he called a “defensive war” against Poland, stating that “the series of border violations, which are unbearable to a great power, prove that the Poles no longer are willing to respect the German frontier.”

German invasion of Poland

German invasion of Poland(Taken from German Invasion of Poland – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background At the end of World War I, the Allies reconstituted Poland as a sovereign nation, incorporating into the new state portions of the eastern German territories of Pomerania and Silesia, which contained majority Polish populations. In the 1920s, the German Weimar Republic sought to restore to Germany all its lost territories, but was restrained by certain stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, which had been imposed on Germany after World War I. Polish Pomerania was known worldwide as the “Polish Corridor”, as it allowed Poland access to international waters through the Baltic Sea. The German city of Danzig in East Prussia, as well as nearby areas, also was detached from Germany, and renamed the “Free City of Danzig”, administered by the League of Nations, but whose port, customs, and public infrastructures were controlled by Poland.

In 1933, Hitler came to power and implemented Germany’s massive rearmament program, and later began to pursue his irredentist ambitions in earnest. Previously in January 1934, Nazi Germany and Poland had signed a ten-year non-aggression pact, where the German government recognized the territorial integrity of the Polish state, which included the German regions that had been ceded to Poland. But by the late 1930s, the now militarily powerful Germany was actively pushing to redefine the German-Polish border.

In October 1938, Germany proposed to Poland renewing their non-aggression treaty, but subject to two conditions: that Danzig be restored to Germany and that Germany be allowed to build road and railway lines through the Polish Corridor to connect Germany proper and East Prussia. Poland refused, and in April 1939, Hitler abolished the non aggression pact. To Poland, Hitler was using the same aggressive tactics that he had used against Czechoslovakia, and that if it yielded to the German demands on Danzig and the Polish Corridor, ultimately the rest of Poland would be swallowed up by Germany.

Meanwhile, Britain and France, which had pursued appeasement toward Hitler, had become wary after the German occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia, which had a non-ethnic German majority population, which was in contrast to what Hitler had said that he only wanted returned those German-populated territories. Britain and France were now determined to resist Germany diplomatically and resolve the crisis through firm negotiations. On March 31, 1939, Britain and France

announced that they would “guarantee Polish independence” in case of foreign aggression. Since 1921, as per the Franco-Polish Military Alliance, France had pledged military assistance to Poland if that latter was attacked.

In fact, Hitler’s intentions on Poland was not only the return of lost German territories, but the elimination of the Polish state and annexation of Poland as part of Lebensraum (“living space”), German expansion into Eastern Europe and Russia. Lebensraum called for the eradication of the native populations in these conquered areas. For Poland

specifically, on August 22, 1939 in the lead-up to the German invasion, Hitler had said that “the object of the war is … to kill without pity or mercy all men, women, and children of Polish descent or language. Only in this way can we obtain the living space we need.” In April 1939, Hitler instructed the German military High Command to begin preparations for an

invasion of Poland, to be launched later in the summer. By May 1939, the German military had drawn up the invasion plan.

In May 1939, Britain and France held high-level

talks with the Soviet Union regarding forming a tripartite military alliance against Germany, especially

in light of the possible German invasion of Poland. These talks stalled, because Poland refused to allow Soviet forces into its territory in case Germany attacked. Unbeknown to Britain and France,

the Soviet Union and Germany were also conducting (secret) separate talks regarding bilateral political,

military, and economic concerns, which on August 23, 1939, led to the signing of a non-aggression treaty. This treaty, which was broadcast to the world and widely known as the Molotov Ribbentrop Pact (named after Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop), brought a radical shift to the European power balance, as Germany was now free to invade Poland without fear of Soviet reprisal. The pact also included a secret protocol where Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania were divided into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

One day earlier, August 22, with the non aggression treaty virtually assured, Hitler set the invasion date of Poland for August 26, 1939. On August 25, Hitler told the British ambassador that Britain must agree to the German demands on Poland, as the non-aggression pact freed Germany from facing a two-front war with major powers. But on that same day, Britain and Poland signed a mutual defense pact, which contained a secret clause where the British promised military assistance if Poland was attacked by Germany. This agreement, as well as British overtures that Britain and Poland were willing to restart the stalled talks with Germany, forced Hitler to abort the invasion set for the next day.

The Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) stood down, except for some units that did not receive the new stop order and crossed into Poland, skirmishing with the Poles. These German units soon withdrew back across the border, but the Polish High Command, informed through intelligence reports of massive German build-up at the border, was unaware that the border skirmishes were part of an aborted German invasion.

German negotiations with Britain and France

continued, but they failed to make progress.

Poland had refused to negotiate on the basis of ceding territory, and its determination was

strengthened by the military guarantees of the Western Powers, particularly in that if the Germans invaded, the British and French would attack from the west, and Germany would be confronted with a two-front war.

On August 29, 1939, Germany sent Poland a set of proposals for negotiations, which included two points: that Danzig be returned to Germany and that a plebiscite be held in the Polish Corridor to determine whether the territory should remain with Poland or be returned to Germany. In the latter, Poles who were born or had settled in the Corridor since 1919 could not vote, while Germans born there but not living there could vote. Germany demanded that negotiations were subject to a Polish official with signing powers arriving by the following day, August 30.

Britain deemed that the German proposal was an ultimatum to Poland, and tried but failed to convince the Polish government to negotiate. On August 30, the German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop presented the British ambassador with a 16-point proposal for negotiations, but refused the latter’s request that a copy be sent to the Polish government, as no Polish

representative had arrived by the set date. The next day, August 31, the Polish Ambassador Jozef Lipski conferred with Ribbentrop, but as Lipski had no signing powers, the talks did not proceed. Later that day, Hitler announced that the German-Polish talks had ended because of Poland’s refusal to negotiate. He then ordered the German High Command to proceed with the invasion of Poland for the next day, September 1, 1939.

August 30, 2019

August 30, 1998 – Second Congo War: The Congo Army and its Angolan and Zimbabwean allies recapture Matadi from Rwandan forces

On August 30, 1998, forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), together with their Angolan and Zimbabwean allies, recaptured the town of Matadi from Rwandan forces and the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD) militia during the ongoing Second Congo War.

(Taken from Second Congo War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

By this time, Angolan forces also had come to the aid of Democratic Republic of the Cong (DRC) President Kabila’s beleaguered regime, entering through the Angolan province of Cabinda. The Angolans took control of the Congo’s western region, including liberating the towns of Matadi and Kitona, and moved eastward to meet up with the Zimbabwean Army in Kinshasa. More Zimbabwean forces began pouring in via Zambia into southern Congo, with the aim of securing Mbuji-Mayi, a diamond-rich mining town in Kasai-Oriental Province. With military forces from Namibia deploying in the western Congo and those from Chad entering through the north, both in support of the Congolese government, and Burundi, backing the invaders, the conflict threatened to expand into a full-blown multinational war (in fact, the war has been called “Africa’s World War”).

With Kinshasa secure by early September, the Angola-Zimbabwe-Congo coalition made plans to

launch an offensive into rebel-held territories further east. Rwanda and Uganda had recruited extensively – some 100,000 new soldiers were brought to the

frontlines, greatly overmatching in numbers the combined Angolan-Zimbabwean forces (the latter, however, consisted mainly of elite combat units). Both sides of the conflict also increased the

strength of their battle tanks, armored vehicles, artillery, and warplanes.

In the following months, a number of indecisive battles took place, as each side tried to expand its control in northern Katanga Province and in central Congo. In northern Congo, the Ugandan Army organized the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, a proxy militia, to serve as its advance force in its offensive into northeast Congo.

Background of the Second Congo War

The First Congo War (previous article) ended when Laurent-Désiré Kabila took over power in Zaire. He formed a new government and named himself

the country’s president. He renamed the country the “Democratic Republic of the Congo”. President Kabila faced enormous problems: the country’s infrastructure was in ruins partly because of the war but mainly because of neglect by the previous regime; the economy was devastated; and most of the people lived in poverty.

And these were the least of President Kabila’s

problems. He was most concerned about his tenuous hold on power. He had merged his rebel forces with the Rwandan Army, which produced tensions between the two former enemies. Furthermore, some military officers remained loyal to ex-President Mobutu Sese Seko, the deposed tyrant.

To consolidate power, President Kabila set up an

authoritarian regime, centralized power, and appointed relatives and friends to top government positions. His administration was accused of nepotism, abuse of power, and corruption, and

President Kabila’s critics drew similarities between his government and the former regime – implying that nothing had changed.

More crucial image-wise for President Kabila was the ubiquitous presence in the Congo of foreign troops, particularly those from Rwanda and Uganda;

these countries had helped him win the First Congo War. The Congolese people perceived the foreign

armies as holding real power in the country, with President Kabila merely acting as a figurehead. For this reason, on July 14, 1998, President Kabila sacked his Armed Forces chief of staff, a Rwandan, an act that began a chain of events that led to the Second Congo War.

On July 27, President Kabila ordered the Rwandan and Ugandan Armies to leave the country. A week later, he terminated the appointments of all Tutsi public officials. The Congolese people regarded the Tutsis as foreigners, despite the fact that Banyamulenge Tutsis were long established in

the Congo’s eastern provinces.

As a result of President Kabila’s edict, Uganda pulled out its forces from the Congo. The Rwandan government also ordered its forces to withdraw, not out of the Congo, but to the remote, weakly defended Kivu Provinces in eastern Congo. Rwanda believed that its security concerns – the main reason for its involvement in the First Congo War – had not

been fully met. In particular, the Rwandan government noted that the Hutu militias had reorganized and once again were carrying out raids into Rwanda. Furthermore, the Banyamulenge Tutsis, who had formed an alliance with Rwanda during the First Congo War, requested the Rwandans to remain in the Kivu Provinces. The Banyamulenge’s citizenship had been revoked by a new law, and the Congolese government ordered them to leave the country.

Rwanda and Uganda organized the Banyamulenge into a proxy militia called the “Rally for Congolese Democracy”, or RCD, whose aim was to overthrow President Kabila. As in the First Congo War, Rwanda and Uganda used a proxy force to fight

their wars, as direct intervention by their armies was a violation of international law.

August 29, 2019

August 29, 1943 – World War II: The Danish Navy scuttles its ships; in response, Germany dissolves the Danish government and imposes martial law

In the early morning of August 29, 1943, the Danish Navy scuttled many of its ships at the Copenhagen harbor to prevent them from falling into German possession. Just a few hours earlier, German forces had entered the city to take over Denmark and disarm the Danish military. Of the 52 vessels of the Danish Navy (2 were in Greenland), 32 were scuttled, 4 escaped to Sweden, and 14 were captured by the Germans. Danish military casualties were 23-26 killed and 40-50 wounded; 4,600 Danish personnel were interred. Germany had invaded Denmark in April 1940 but had allowed the Danish Navy to continue its maritime responsibilities which otherwise would have been taken up the German Navy, using much-needed manpower and resources that could be used elsewhere.

Also on August 29, the Germans dissolved the Danish government and imposed martial law throughout the country. The Danish cabinet tendered

its resignation, which was not accepted by King Christian, and so continued to function until the end of the war.

The events were the culmination of the “August crisis”, where during the summer of 1943, the Danish population launched increasingly hostile civil unrest against the German occupation forces. Worker strikes, street demonstrations, and acts of sabotage as well as passive resistance were prevalent across the country. On August 28, Germany declared Denmark as “enemy territory” following the inability of German and Danish authorities to control the unrest.

On August 28, German authorities imposed censorship on public assemblies and strikes and curfew and introduced special military courts that imposed the death penalty for acts of sabotage. At the same time, an ultimatum was issued to the Danish government, which refused, leading to the German decision to declare Denmark “enemy territory” and to take over the administration of the country.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

After the German invasion of Denmark On April 10, 1940, German forces peacefully occupied Bornholm, Denmark’s easternmost island located in the Baltic Sea. Two Danish-linked territories were seized by the British: the Faroe Islands on April 12, and Iceland, a self-governing state with the Danish king as its head of state, on May 10. Greenland, a Danish colony, took a different path in World War II. Henrik Kauffmann, the Danish ambassador to the United States, signed a

treaty with the U.S. government that allowed American military bases to be constructed in the island to protect it from German invasion. At

this time, the United States was still neutral and a non-belligerent in World War II. The Danish government in Copenhagen, now controlled by the Germans as a protectorate, rejected the treaty.

In the immediate aftermath of the invasion, Denmark was allowed to maintain much of its internal political and administrative duties, King Christian X remained as the nation’s head of state, and the legislature, police, and judiciary continued to function as before. The Danish people generally were displeased by the German occupation, but also accepted the reality of the situation, especially after France’s defeat only two months later, in June 1940.

By 1943, German-Danish relations had deteriorated, and Denmark’s “politics of cooperation” ended, and the Danish people became hostile toward

the occupation forces. Then when a spate of strikes, civil unrest, and sabotages broke out, and an armed resistance movement began to emerge, German authorities dissolved the Danish government, declared martial law, and enforced anti-dissident measures, including press censorship, banning strikes and mass assemblies, and imposing the death penalty

for saboteurs, as well as ordering the round up of all Jews for deportation.