Daniel Orr's Blog, page 2

December 21, 2024

December 21, 1949 – The Netherlands recognizes the sovereignty of Indonesia

On July 6, 1949, upon their release, Indonesian nationalistleaders Sukarno and Hatta restored the revolutionary government in Yogyakarta, and one week later, they ratified theRoem-van Roijen Agreement. In mid-August1949, a ceasefire came into effect. In aseries of meetings, called the Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference held atThe Hague, Netherlands in August-November 1949, the Netherlands, the IndonesianRepublic, and the Federal Consultative Assembly (Dutch: Bijeenkomst voorFederaal Overleg, which represented the six states and nine autonomousterritories created by the Dutch under USI) agreed that USI be grantedindependence under the Indonesian government, with Sukarno and Hatta as itsPresident and Vice-President, respectively. The Netherlandsand USI would form a loose association called the Netherlands-Indonesian Unionunder the Dutch monarchy. A stipulationwas that the Dutch military would leave USI, with security functions to beturned over to the Indonesian Armed Forces. Two other difficult issues were settled: 1. the responsibility forpaying off the Dutch East Indies debt totaling 4.3 billion guilders was to beborne by USI, and 2. that West New Guinea, which formed part of the Dutch EastIndies and claimed by the Indonesian Republic as belonging to USI by way ofstate succession, was agreed to remain with the Netherlands until futurenegotiations regarding its future could be held within one year after USI’sindependence. On December 27, 1949, the Netherlandsformally relinquished authority over USI, which also became a fully sovereign,independent state.

Aftermath of theIndonesian War of Independence Indonesia’sindependence war caused some 50,000-100,000 Indonesian deaths. The Dutch military lost over 5,000 soldierskilled. Some 1,200 British soldiers(mainly British Indians) also were killed in action. Several million people were displaced. Also in the 1950s, a diaspora of took place,with some 300,000 Dutch nationals leaving Indonesiafor the Netherlands.

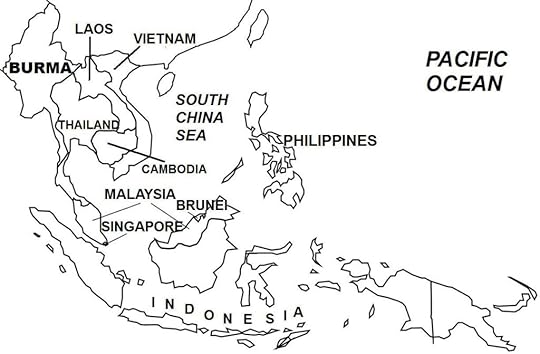

Indonesia in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia in Southeast Asia.(Taken from Indonesian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Sukarno’s proclamation of Indonesia’s independence de factoproduced a state of war with the Allied powers, which were determined to gaincontrol of the territory and reinstate the pre-war Dutch government. However, one month would pass before theAllied forces would arrive. Meanwhile,the Japanese East Indies command, awaiting the arrival of the Allies torepatriate Japanese forces back to Japan, was ordered by the Alliedhigh command to stand down and carry out policing duties to maintain law andorder in the islands. The Japanesestance toward the Indonesian Republic varied:disinterested Japanese commanders withdrew their units to avoid confrontationwith Indonesian forces, while those sympathetic to or supportive of therevolution provided weapons to Indonesians, or allowed areas to be occupied byIndonesians. However, other Japanesecommanders complied with the Allied orders and fought the Indonesianrevolutionaries, thus becoming involved in the independence war.

In the chaotic period immediately after Indonesia’sindependence and continuing for several months, widespread violence and anarchyprevailed (this period is known as “Bersiap”, an Indonesian word meaning “beprepared”), with armed bands called “Pemuda” (Indonesian meaning “youth”)carrying out murders, robberies, abductions, and other criminal acts against groupsassociated with the Dutch regime, i.e. local nobilities, civilian leaders,Christians such as Menadonese and Ambones, ethnic Chinese, Europeans, andIndo-Europeans. Other armed bands werecomposed of local communists or Islamists, who carried out attacks for the samereasons. Christian and nobility-alignedmilitias also were organized, which led to clashes between pro-Dutch andpro-Indonesian armed groups. Theseso-called “social revolutions” by anti-Dutch militias, which occurred mainly inJava and Sumatra, were motivated by variousreasons, including political, economic, religious, social, and ethniccauses. Subsequently when the Indonesiangovernment began to exert greater control, the number of violent incidents fell,and Bersiap soon came to an end. Thenumber of fatalities during the Bersiap period runs into the tens of thousands,including some 3,600 identified and 20,000 missing Indo-Europeans.

The first major clashes of the war occurred in late August1945, when Indonesian revolutionary forces clashed with Japanese Army units,when the latter tried to regain previously vacated areas. The Japanese would be involved in the earlystages of Indonesia’sindependence war, but were repatriated to Japan by the end of 1946.

In mid-September 1945, the first Allied forces consisting ofAustralian units arrived in the eastern regions of Indonesia (where revolutionaryactivity was minimal), peacefully taking over authority from the commander ofthe Japanese naval forces there. Alliedcontrol also was established in Sulawesi, withthe provincial revolutionary government offering no resistance. These areas were then returned to Dutchcolonial control.

In late September 1945, British forces also arrived in theislands, the following month taking control of key areas in Sumatra, including Medan, Padang, and Palembang, and inJava. The British also occupied Jakarta (then still known, until 1949, as Batavia),with Sukarno and his government moving the Republic’s capital to Yogyakarta in Central Java. InOctober 1945, Japanese forces also regained control of Bandungand Semarangfor the Allies, which they turned over to the British. In Semarang, the intense fighting claimed thelives of some 500 Japanese and 2,000 Indonesian soldiers.

December 20, 2024

December 20, 1989 – The U.S. invades Panama to depose dictator Manuel Noriega

In the early morning of December 20, 1989, the United States invaded Panama. Approval for the invasion was given on December17, 1989, which had two major military objectives: to defeat the Panamanianforces and to capture General Noriega. In a nationwide address following the start of the invasion, PresidentBush gave the following reasons for ordering the invasion: to protect U.S.citizens in Panama, to re-establish democracy and defend human rights inPanama, to combat drug trafficking, and to uphold the Torrijos-CarterTreaties. Some 300 U.S. planes carried out attacks on many targetsacross Panama,including airfields, army bases, and military-vital public infrastructures.

U.S.ground forces, numbering about 28,000 soldiers, advanced from their bases onthe Pacific side of the Canal Zone for Panama City,as well as from the Caribbean end of the Canal for Colon. Paratroopers also were airdropped at Tocumen, seizing Torrijosairport. Smaller-scale operations werecarried out in Panamanian military and civilian targets in the Canal Zone interior. In Panama City, U.S. air attacks concentrated onthe Panamanian Army’s headquarters, which was located in the densely populatedneighborhood of El Chorillo. As aresult, many civilians were killed and a large fire broke out, burning down thewhole neighborhood and leaving thousands of residents without homes.

The Panamanian forces were caught by surprise and failed tomount effective opposition, except for small pockets of resistance. The speed of the U.S. ground offensives also avertedprolonged urban combat and thus greater civilian casualties. By December 24, four days into the invasion,large-scale fighting had ended (although skirmishes continued to break out forseveral weeks more), and General Noriega had taken refuge inside the ApostolicNunciature (Vatican Embassy) in Panama City. U. S. forcessurrounded and blockaded the Embassy’s perimeter but did not enter thebuilding, since doing so to make an arrest was a violation of internationallaw. The Vaticaninitially was opposed to handing over General Noriega to the United States, as U.S. authorities requested, and insteadtried to convince the Panamanian leader to surrender voluntarily.

U.S.authorities exerted diplomatic and psychological pressures, which includedtanks rumbling noisily in the streets, helicopters hovering overhead, and24-hour loud playing of rock music outside the Embassy building. Strong persuasion exerted by Monsignor JoseSebastian Laboa, the Papal Nuncio (Vatican Ambassador) to Panama, prevailed upon General Noreiga tosurrender to the U.S.military on January 3, 1990. Noriega wasturned over to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) authorities, whotransported him to the United States to face trial.

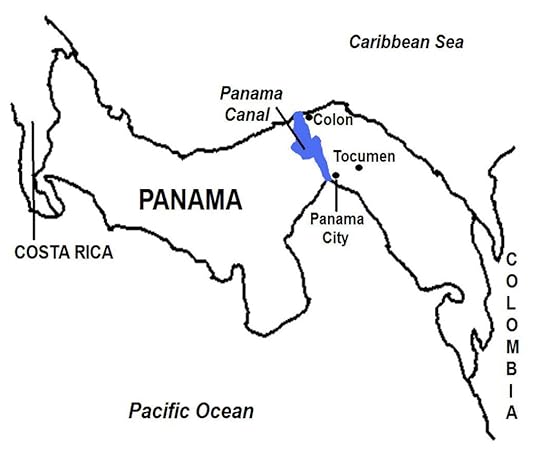

The Panama Canal.

The Panama Canal.(Taken from United States Invasion of Panama – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and the Caribbean)

Background Sinceits independence, Panamahad been ruled by a succession of civilian governments. In 1968, military officers overthrew thegovernment. General Torrijos, the coup’sleader, established a de facto military regime that ruled behind a façade of acivilian government that was subservient to the military. Then in December 1983, the Panamanian armedforces came under the control of General Manuel Noriega who increased themilitary’s stranglehold over the country. In general elections held in May 1984, General Noriega manipulated theresults of the presidential race to allow his chosen candidate to win.

In the early 1980s, Central Americabecame a major battleground of the Cold War. In search of support, the United States was willing to ignoreGeneral Noriega’s abuses of power and have the Panamanian strongman, a staunchanti-communist, as an ally. GeneralNoriega already had a long-standing relationship with the United States, havingbeen an asset and informant of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) since theearly 1960s, and had even mediated for the U.S. government with Cuban leaderFidel Castro for the release of American prisoners in Cuba.

General Noriega transformed Panamainto a center for smuggling cocaine and other narcotics from Colombia to the United States and othercountries. He masterminded and led theseoperations and later asserted that the CIA and other U.S. government agencies knew andeven supported these activities. Meanwhile in the United States, President Ronald Reagan was himself under pressure from an investigationby the U.S. Congress for possible involvement in the “Iran-Contra Affair”, acovert operation where the U.S. government sold weapons to Iran (for therelease of American hostages), and the proceeds were then used to fund pro-U.S.“contra” rebels in Nicaragua.

Soon, relations between General Noriega and the U.S. governmentdeteriorated. Then as more reports from Panamaindicated General Noriega’s involvement in the drug trade, President Regan putpressure on the Panamanian leader, even urging him to step down fromoffice. President Reagan also wasalarmed at the increasing military repression and political instability in Panama,generated by growing opposition to General Noriega’s rule and governmentcorruption. General Noriega particularlywas condemned by the local opposition following the murder of Hugo Spadafora, agovernment critic who had returned to Panama to present evidence of themilitary leader’s involvement in the drug trade and other crimes. In response to public opposition to his rule,the Panamanian strongman released his forces, resulting in violentconfrontations where many civilians were beaten up in street protests.

In February 1988, grand juries in Miamiand Floridafiled drug smuggling, money laundering, and racketeering lawsuits againstGeneral Noriega. Panamanian assets inthe United States werefrozen, which severely affected Panamathat already was reeling as a result of the United States suspension ofmilitary aid a year earlier. In March1988, a coup by security officers failed to overthrow General Noriega.President Reagan also began to explore more forceful ways to depose thePanamanian leader, but preferably to be carried out by Panamanians, andsupported or led by the Panamanian military.

In January 1989, George H.W. Bush succeeded as the new U.S.President. By then, the Cold War wasdrawing to a close – at the end of 1989, Eastern Bloc countries had shed offcommunism for democracy, while the Soviet Unionitself was on the verge of collapse. InCentral America, the ongoing Cold War conflicts also were winding down inresponse to the improving global security and political climates, and the United Statesfelt less the need to continue funding its allies in the region. For the United States, General Noriega’smany faults, which long had been set aside because of his strong anti-communistposition, now became too glaring to ignore.

Shortly after taking office, President Bush announced thatone of his government’s domestic priorities was to tackle the growing drugproblem with a so-called “war on drugs’, aimed at expanding a similar anti-drugcampaign that had been in force since the previous administration. A decade earlier, Bush had served as CIADirector (in 1976) and had dealings with Noriega, who was then Panama’sintelligence chief and whose services would become vital for the United Statesin the heightened Cold War situation in Central America from the late 1970sthrough most of the 1980s.

Now as U.S.head of state, President Bush sought to distance himself from General Noriega,and made a determined effort to remove the Panamanian leader from power. In May 1989, Panama held general elections. The U.S. government openly supportedthe main opposition party, hoping that a new government would remove GeneralNoriega as head of the newly created Panama Defense Forces (the Panamanianmilitary and police forces). As electionresults showed a clear defeat for the government’s hand-picked presidential candidate,General Noriega stopped the tabulations and voided the elections, declaringthat meddling by the United States (by supporting the opposition) hadundermined the election’s legitimacy. Panama’selectoral tribunal concurred, declaring that widespread fraud had taken place,tarnishing the results. However,international poll observers, which included former U.S. President Carter,concluded that the elections generally were free and fair, and that theopposition’s wide lead in the results genuinely reflected the electorate’schoice. Mass rallies and demonstrationsbroke out in Panama City;General Noriega responded by sending his paramilitary, called the DignityBattalion, that attacked and broke up the crowds. In the melee, leading opposition candidateswere beaten up, scenes of which were caught by the television news media andaired in the United States. Thereafter, the Organization of AmericanStates (OAS) condemned the violence and joined the United States in calling forGeneral Noriega to resign which, however, was rejected by the Panamanianleader.

In October 1989, with partial U.S. support, a group of Panamanianmilitary officers tried to overthrow General Noriega in a coup. Loyal government forces, however, succeededin rescuing the Panamanian leader, leading to the uprising’s collapse andexecution of the coup plotters. In theaftermath, President Bush was criticized for what was perceived as hishalf-hearted support for the coup.

Meanwhile, as tensions rose between the United States and Panama,the U.S. military sent moretroops and weapons to American bases in the Canal Zone. The United States was preparing for a full invasion of Panama, aimedat overthrowing General Noriega. Throughout the summer of 1989, U.S. forces carried out continuousmilitary exercises and maneuvers which Panamanians condemned as a deliberateattempt at provoking an incident to start a war. The increased U.S.military activity so provoked General Noriega that on December 15, 1989, whileaddressing the Panamanian National Assembly, he declared that a state of warexisted between Panama andthe United States. At the same gathering, the country’s civilianauthority was abolished when the legislators conferred on General Noriega thetitle of “líder máximo”, or maximum leader, i.e. absolute dictator.

As a result of General Noriega’s actions, President Bushbelieved that American citizens living in Panamaand the Panama Canal were in danger. In the following days, a number of incidentsbetween Panamanian and U.S.forces would precipitate the United States to start the invasion. In one of these incidents, a U.S. Marine waskilled when Panamanian security forces manning a roadblock fired on an Americanvehicle, while another U.S.officer and his wife were arrested, detained, and harassed by Panamaniansoldiers.

December 19, 2024

December 19, 1946 – First Indochina War: Start of the Battle of Hanoi

When French authorities demanded that the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) government relinquish control of Hanoi, on December 19, 1946, some 30,000 Viet Minh fighters attacked the French, and attempted to block access to the main French garrison in the city. French authorities, who were informed of the plan, foiled the Viet Minh. But the latter detonated explosives that shut down Hanoi’s power plant, cutting off electricity and plunging the city into darkness.

In the ensuing two-month long Battle of Hanoi, French andViet Minh forces engaged in intense house-to-house fighting, but Frenchmilitary superiority, especially the use of heavy artillery and air firepower,forced Viet Minh forces to evacuate the city and retreat to their traditionalstrongholds in the Viet Bac region in the far north. French forces then gained control of Hanoi. By late 1946, the Viet Minh still controlledthe areas around Haiphong, Hue, and Nam Dinh, but in March 1947, Frenchoperations cleared the roads to these major urban areas.

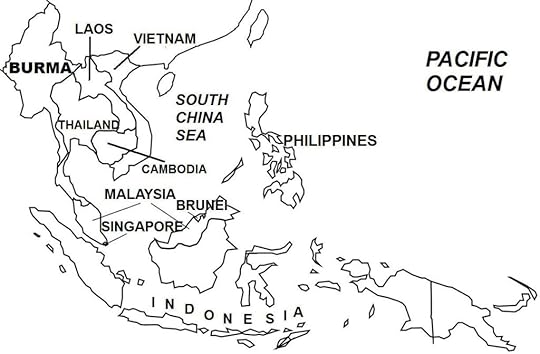

Present-day Southeast Asia.

Present-day Southeast Asia.(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Early in the war, the Viet Minh suffered from a serious lackof weapons, and thus resorted to guerilla warfare. But they took advantage of Vietnam’sthickly covered jungle mountains for refuge and concealment. Jungles and mountains comprised 40% of Vietnam’sterritory, an invaluable asset for the Viet Minh, but also a formidableobstacle which French forces were unable to overcome in the war. Throughout the war, while the Frenchcontrolled the major urban areas, Viet Minh forces operated in much of thehinterland regions, where they established their influence, and gained thesupport of the residents in remote villages and settlements.

The French military in Indochinawas organized as the French Far-East Expeditionary Corps (CEFEO; French: CorpsExpéditionnaire Français en Extrême-Orient). At its peak, CEFEO had a total strength of 200,000 troops, and consistedmostly of pro-French Vietnamese soldiers. Small contingents also were brought in from French territories in Africa, as well as from the French Foreign Legion. Early on, CEFEO suffered from inadequate orobsolete weapons, which nonetheless had more firepower than those used by theViet Minh.

In October 1947, French authorities launched Operation Leain Bac CanProvince (located near the Chineseborder) with three major aims: to stop the flow of weapons from China to theViet Minh, destroy the Viet Minh organization, and capture the Viet Minhleadership. Some 1,000 French commandoswere air-dropped in Viet Minh-held territory, while 15,000 ground troops weretasked to block Viet Minh escape routes. The offensive inflicted some 9,000 Viet Minh casualties, but the Frenchalso suffered 1,000 killed and 3,000 wounded; large quantities of Viet Minhstores and equipment also were seized. But Ho Chi Minh and his commanders, as well as the bulk of the VietMinh, slipped past the French cordon.

A second French offensive (Operation Ceinture) in November1947 near Thai Nguyen and Tuyen Quang failed to battle the Viet Minh, whichagain escaped. The Viet Minh implementedthe policy of carrying out guerilla attacks in scattered areas in order toover-extend French forces and defeat the French in a protected war ofattrition. The French soon experienceddwindling military resources and were unable to launch more large-scaleattacks, while the Viet Minh, by late 1947, had grown to some 250,000 fighters,and occupied areas that the French had abandoned.

By 1948, Francerealized that it could not anymore restore colonial rule in Indochina. French authorities therefore opened talkswith former Vietnamese emperor Bao Dai regarding establishing a pro-FrenchVietnamese state, which would accomplish the political objective of underminingthe Viet Minh and its DRV government. Negotiations were successful, with the French government and Bao Daisigning two agreements: the First Hai Long Bay Agreement (December 1947), whichstipulated Vietnam’s“independence within the French Union”, and the Second Hai Long Bay Agreement(June 1948), which provided for a clearer stipulation of Vietnam’sindependence. In both agreements, Francewould continue to administer Vietnam’sforeign policy decisions and external security functions. As a result of the two agreements, Bao Daiformed a new government in Saigon. However, within a short period, he abdicatedand left Vietnam for Europe in frustration at not being granted genuinepolitical power.

The French renegotiated with Bao Dai, which led to thesigning in March 1949 of the Elysee Agreement, which stipulated the formationof the State of Vietnam comprising Tonkin, Annam, andCochinchina. However, the agreement alsoallowed France to continueto control Vietnam’sforeign policy and external security functions. Bao Dai then returned to Vietnamand formed a new government. UnderFrench oversight, in July 1949, the “independent” Vietnamese state formed itsown armed forces (the Vietnamese National Army), which thereafter fought alongsideCEFEO.

During the first years of the war, the major world powerssaw the conflict merely as an internal (i.e. colonial) matter of the French, oran independence struggle of the Vietnamese people. In March 1947, U.S. President Trumandelivered a speech, which eventually came to be known as the Truman Doctrine,where he vowed to “contain” what he saw was the Soviet Union’s expansionistambitions in Greece and Turkey. This new American policy marked the start ofthe Cold War.

During World War II and in the immediate aftermath, the U.S. government appeared opposed to restoringFrench rule in Indochina, for a number for reasons: Ho Chi Minh had been a U.S. ally in the war; pre-war French colonialrule had been repressive; and the United States was averse tocolonialism. But with the restoration ofFrench rule, the United Stateskept a hands-off policy in Indochina.

Two events changed U.S.policy toward Indochina and Asia. First, in October 1949, Chinese communists,emerging victorious after a long civil war in China,established the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a communiststate. Second, in June 1950, North Korea, backed by the Soviet Union and thePRC, invaded U.S.-allied South Korea, triggering the Korean War. President Truman became convinced that notonly did the Soviet Union have expansionist ambitions in Europe, but thatSoviet leader Josef Stalin and Chinese leader Mao Zedong also were determinedto spread communism in Asia. The nextU.S. President, Dwight D. Eisenhower, would introduce the Domino Principle,which stated that if the communists prevailed in Korea and Vietnam, the rest ofthe countries of Southeast Asia would be next to fall to communism, akin to arow of dominoes falling one after the other.

As a result, the United Statesstrengthened its military presence in East Asia,reversing its post-World War II policy of withdrawing American forces from theregion. In February 1950, the U.S. government recognized the French-backed Stateof Vietnam,which was led by Bao Dai. In July 1950,the first shipments of U.S.war supplies arrived. Three months later(September 1950), after French and American military officials held talks inWashington, D.C., the United States established the Military Assistance andAdvisory Group (MAAG), tasked with serving as the liaison agency that wouldprovide weapons, as well as military advice and training. U.S. military support to the Frenchwould dramatically increase over the following years to a total of $3billion. By 1954, the United States would be supplying 80% of thetotal weapons used by French forces in Vietnam. A total of 1,400 tanks, 340 planes, 240,000small firearms, and 150 million bullets were sent.

December 18, 2024

December 18, 1972 – Vietnam War: Start of Operation Linebacker II, where U.S. warplanes undertake massive bombing attacks on North Vietnam

On December 14, 1972, the U.S.government issued a 72-hour ultimatum to North Vietnam to return tonegotiations. On the same day, U.S. planesair-dropped naval mines off the North Vietnamese waters, again sealing off thecoast to sea traffic. Then on PresidentNixon’s orders to use “maximum effort…maximum destruction”, on December 18-29,1972, U.S. B-52 bombers and other aircraft under Operation Linebacker II,launched massive bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam, including Hanoiand Haiphong, hitting airfields, air defense systems, naval bases, and othermilitary facilities, industrial complexes and supply depots, and transportfacilities. As many of the restrictionsfrom previous air campaigns were lifted, the round-the-clock bombing attacksdestroyed North Vietnam’swar-related logistical and support capabilities. Several B-52s were shot down in the firstdays of the operation, but changes to attack methods and the use of electronicand mechanical countermeasures greatly reduced air losses. By the end of the bombing campaign, fewtargets of military value remained in North Vietnam, enemy anti-aircraft guns had been silenced, and North Vietnamwas forced to return to negotiations. OnJanuary 15, 1973, President Nixon ended the bombing operations.

One week later, on January 23, negotiations resumed, leadingfour days later, on January 27, 1973, to the signing by representatives fromNorth Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its ProvisionalRevolutionary Government (PRG), and the United States of the Paris PeaceAccords (officially titled: “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace inVietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked the end of the war. The Accords stipulated a ceasefire; therelease and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of all American andother non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for South Vietnam: apolitical settlement between the government and the PRG to determine thecountry’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peaceful reunificationof North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Asin the 1954 Geneva Accords (which ended the First Indochina War), the DMZ didnot constitute a political/territorial border. Furthermore, the 200,000 North Vietnamese troops occupying territoriesin South Vietnamwere allowed to remain in place.

Southeast Asia during the 1960s.

Southeast Asia during the 1960s.(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

To assuage South Vietnam’sconcerns regarding the last two points, on March 15, 1973, President Nixonassured President Thieu of direct U.S.military air intervention in case North Vietnam violated theAccords. Furthermore, just before theAccords came into effect, the United Statesdelivered a large amount of military hardware and financial assistance to South Vietnam.

By March 29, 1973, nearly all American and other alliedtroops had departed, and only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisorsremained. A peacekeeping force, calledthe International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnamto monitor and enforce the Accords’ provisions. But as large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS becamepowerless and failed to achieve its objectives.

For the United States, the Paris Peace Accords meant theend of the war, a view that was not shared by the other belligerents, asfighting resumed, with the ICCS recording 18,000 ceasefire violations betweenJanuary-July 1973. President Nixon hadalso compelled President Thieu to agree to the Paris Peace Accords under threatthat the United States wouldend all military and financial aid to South Vietnam, and that the U.S.government would sign the Accords even without South Vietnam’s concurrence. Ostensibly, President Nixon could fulfill hispromise of continuing to provide military support to South Vietnam, as he had beenre-elected in a landslide victory in the recently concluded November 1972presidential election. However, U.S. Congress, which was now dominated byanti-war legislators, did not bode well for South Vietnam. In June 1973, U.S. Congress passedlegislation that prohibited U.S.combat activities in Vietnam,Laos, and Cambodia,without prior legislative approval. Alsothat year, U.S. Congress cut military assistance to South Vietnam by 50%. Despite the clear shift in U.S. policy, South Vietnam continued to believe the U.S. governmentwould keep its commitment to provide military assistance.

Then in October 1973, a four-fold increase in world oilprices led to a global recession following the Organization of PetroleumExporting Countries (OPEC) imposing an oil embargo in response to U.S. support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War. South Vietnam’seconomy was already reeling because of the U.S.troop withdrawal (a vibrant local goods and services economy had existed inSaigon because of the presence of large numbers of American soldiers) andreduced U.S.assistance. South Vietnam experienced soaringinflation, high unemployment, and a refugee problem, with hundreds of thousandsof people fleeing to the cities to escape the fighting in the countryside.

The economic downturn also destabilized the South Vietnameseforces, for although they possessed vast quantities of military hardware (forexample, having three times more artillery pieces and two times more tanks andarmor than North Vietnam), budget cuts, lack of spare parts, and fuel shortagesmeant that much of this equipment could not be used. Later, even the number of bullets allotted tosoldiers was rationed. Compoundingmatters were the endemic corruption, favoritism, ineptitude, and lethargy prevalentin the South Vietnamese government and military.

In the post-Accords period, South Vietnam was determined toregain control of lost territory, and in a number of offensives in 1973-1974,it succeeded in seizing some communist-held areas, but paid a high price inpersonnel and weaponry. At the sametime, North Vietnamwas intent on achieving a complete military victory. But since the North Vietnamese forces hadsuffered extensive losses in the previous years, the Hanoigovernment concentrated on first rebuilding its forces for a planned full-scaleoffensive of South Vietnam,planned for 1976.

In March 1974, North Vietnamlaunched a series of “strategic raids” from the captured territories that itheld in South Vietnam. By November 1974, North Vietnam’s control hadextended eastward from the north nearly to the south of the country. As well, North Vietnamese forces nowthreatened a number of coastal centers, including Da Nang,Quang Ngai, and Qui Nhon, as well as Saigon. Expanding its occupied areas in South Vietnam also allowed North Vietnam to shift its logistical system(the Ho Chi Minh Trail) from eastern Laosand Cambodia to inside South Vietnamitself. By October 1974, with major roadimprovements completed, the Trail system was a fully truckable highway fromnorth to south, and greater numbers of North Vietnamese units, weapons, andsupplies were being transported each month to South Vietnam.

North Vietnam’s“strategic raids” also were meant to gauge U.S. military response. None occurred, as at this time, the United Stateswas reeling from the Watergate Scandal, which led to President Nixon resigningfrom office on August 9, 1974. Vice-President Gerald Ford succeeded as President.

Encouraged by this success, in December 1974, NorthVietnamese forces in eastern Cambodiaattacked Phuoc LongProvince, taking its capital PhuocBinh in early January 1975 and sending pandemonium in South Vietnam, but again producing no militaryresponse from the United States. President Ford had asked U.S. Congress for military support for South Vietnam,but was refused.

December 17, 2024

December 17, 1918 – Latvian War of Independence: Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic is formed

Under the patronage of Soviet Russia, on December 17, 1918, the Latvian Socialist Soviet Republic led by Latvian communist Pēteris Stučka, was set up as a regime to rival the Latvian nationalist provisional government of Kārlis Ulmanis that had been formed one month earlier. Two Latvian governments now vied for legitimacy during the Latvian War of Independence.

Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania form the Baltic States.

Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania form the Baltic States.(Taken from Latvian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background By themid-19th century, as a result of the French Revolution (1789-1799), a wave ofnationalism swept across Europe, a phenomenon that touched into Latviaas well. The Latvian nationalistmovement was led by the “Young Latvians”, a nationalist movement of the 1850sto 1880s that promoted Latvian identity and consciousness (as opposed to theprevailing Germanic viewpoint that predominated society) expressed in Latvianart, culture, language, and writing. TheBaltic German nobility used its political and economic domination of society tosuppress this emerging Latvian nationalistic sentiment. The Russian government’s attempt at“Russification” (cultural and linguistic assimilation into the Russian state)was rejected by Latvians. The Latviannational identity also was accelerated by other factors: the abolition ofserfdom in Courland in 1817 and Livoniain 1819, the growth of industrialization and workers’ organizations, increasingprosperity among Latvians who had acquired lands, and the formation of Latvianpolitical movements.

The Russian Empire opposed these nationalist sentiments andenforced measures to suppress them. Thenin January 1905, the social and political unrest that gripped Russia (the Russian Revolution of 1905) producedmajor reverberations in Latvia,starting in January 1905, when mass protests in Riga were met with Russian soldiers openingfire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding scores of people. Local subversive elements took advantage ofthe revolutionary atmosphere to carry out a reign of terror in the countryside,particularly targeting the Baltic German nobility, torching houses and lootingproperties, and inciting peasants to rise up against the ethnic Germanlandowners. In November 1905, Russianauthorities declared martial law and brought in security forces that violentlyquelled the uprising, executing over 1,000 dissidents and sending thousands ofothers into exile in Siberia.

Then in July 1914, World War I broke out in Europe, with Russia allied with other major powers Britain and Franceas the Triple Entente, against Germany,Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire that comprised the major CentralPowers. In 1915, the armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary made military gainsin the northern sector of the Eastern Front; by May of that year, German unitshad seized sections of Latvian Courland and Livonian Governorates. A tenacious defense put up by the newlyformed Latvian Riflemen of the Imperial Russian Army held off the Germanadvance into Rigafor two years, but the capital finally fell in September 1917.

The Bolsheviks, on coming to power in the OctoberRevolution, issued the “Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia” (onNovember 15, 1917), which granted all non-Russian peoples of the former RussianEmpire the right to secede from Russia and establish their own separate states.Eventually, the Bolsheviks would renege on this edict and suppress secessionfrom the Russian state (now known as Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic,or RSFSR). The Bolshevik revolution alsohad succeeded partly on the communists promising a war-weary citizenry that Russia wouldwithdraw from World War I; thereafter, the Russian government declared itspacifist intentions to the Central Powers. A ceasefire agreement was signed on December 15, 1917 and peace talksbegan a few days later in Brest-Litovsk (present-day Brest,in Belarus).

However, the Central Powers imposed territorial demands thatthe Russian government deemed excessive. On February 17, 1918, the Central Powers repudiated the ceasefireagreement, and the following day, Germanyand Austria-Hungaryrestarted hostilities, launching a massive offensive with one million troops in53 divisions along three fronts that swept through western Russia and captured Ukraine Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia,and Estonia. German forces also entered Finland,assisting the non-socialist paramilitary group known as the “White Guards” indefeating the socialist militia known as “Red Guards” in the Finnish CivilWar. Eleven days into the offensive, thenorthern front of the German advance was some 85 miles from the Russian capitalof Petrograd.

On February 23, 1918, or five days into the offensive, peacetalks were restarted at Brest-Litovsk, with the Central Powers demanding evengreater territorial and military concessions on Russia than in the December1917 negotiations. After heated debatesamong members of the Council of People’s Commissars (the highest Russiangovernmental body) who were undecided whether to continue or end the war, atthe urging of its Chairman, Vladimir Lenin, the Russian government acquiescedto the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. On March3, 1918, Russian and Central Powers representatives signed the treaty, whosemajor stipulations included the following: peace was restored between Russiaand the Central Powers; Russia relinquished possession of Finland (which wasengaged in a civil war), Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic territories ofEstonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – Germany and Austria-Hungary were to determinethe future of these territories; and Russia also agreed on some territorialconcessions to the Ottoman Empire.

German forces occupied Estonia,Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus,Ukraine, and Poland,establishing semi-autonomous governments in these territories that weresubordinate to the authority of the German monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II. The German occupation of the region allowedthe realization of the Germanic vision of “Mitteleuropa”, an expansionistambition aimed at unifying all Germanic and non-Germanic peoples of Central Europe into a greatly enlarged and powerfulGerman Empire. In support ofMitteleuropa, in the Baltic region, the Baltic German nobility proposed to setup the United Baltic Duchy, a semi-autonomous political entity consisting ofpresent-day Latvia and Estonia thatwould be voluntarily integrated into the German Empire. The proposal was not implemented, but Germanmilitary authorities set up local civil governments under the authority of theBaltic German nobility or ethnic Germans.

Although the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 ended Russia’sparticipation in World War I, the war was still ongoing in other fronts – mostnotably on the Western Front, where for four years, German forces were boggeddown in inconclusive warfare against the British, French and other AlliedArmies. After transferring substantialnumbers of now freed troops from the Russian front to the Western Front, inMarch 1918, Germany launchedthe Spring Offensive, a major attack into Franceand Belgiumin an effort to bring the war to an end. After four months of fighting, by July 1918, despite achieving someterritorial gains, the German offensive had ground to a halt.

The Allied Powers then counterattacked with newly developedbattle tactics and weapons and gradually pushed back the now spent anddemoralized German Army all across the line into German territory. The entry of the United States into the war on the Allied side was decisive, asincreasing numbers of arriving American troops with the backing of the U.S.weapons-producing industrial power contrasted sharply with the greatly depletedwar resources of both the Entente and Central Powers. The imminent collapse of the German Army wasgreatly exacerbated by the outbreak of political and social unrest at the homefront (the German Revolution of 1918-1919), leading to the sudden end of theGerman monarchy with the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II on November 9, 1918and the establishment of an interim government (under moderate socialistFriedrich Ebert), which quickly signed an armistice with the Allied Powers onNovember 11, 1918 that ended the combat phase of World War I.

As the armistice agreement required that Germany demobilizethe bulk of its armed forces as well as withdraw the same to the confines ofthe German borders within 30 days, the German government ordered its forces toabandon the occupied territories that had been won in the Eastern Front. After Germany’scapitulation, Russiarepudiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and made plans to seize back theEuropean territories it previously had lost to the Central Powers. An even far more reaching objective was forthe Bolshevik government to spread the communist revolution to Europe, first bylinking up with German communists who were at the forefront of the unrest thatcurrently was gripping Germany. Russian military planners intended the offensiveto merely follow in the heels of the German withdrawal from Eastern Europe (i.e. to not directly engage the Germans in combat) andthen seize as much territory before the various local ethnic nationalist groupsin these territories could establish a civilian government.

Germany’sdefeat in World War I and the subsequent withdrawal of German forces from theBaltic region produced a political void that local nationalist leaders rapidlyfilled. In Latvia, on November 17, 1918,independence-seeking political leaders established a “People’s Council”(Latvian: Tautas padome), an interim legislative assembly, which in turn formeda provisional government under Prime Minister Kārlis Ulmanis. The next day, November 18, the Latviangovernment declared independence as the Republic of Latvia.

Starting on November 28, 1918, in the action known as theSoviet westward offensive of 1918-1919, Soviet forces consisting of hundreds ofthousands of troops advanced in a multi-pronged offensive with the objective ofrecapturing the Baltic region, Belarus,Poland, and Ukraine.

The northern front of the Soviet offensive was directed at Latvia and Estonia. In Latvia, the Red Army, as Soviet forceswere called and which included the Red Latvian Riflemen (formerly the LatvianRiflemen of the Imperial Russian Army who had shifted their allegiance toBolshevik Russia), made rapid progress and easily gained control of most ofLatvian territory, including Valka, Valmiera, Rēzekne, Daugavpils, and thecapital Riga, which was taken in April 1919. The newly formed Latvian Army and pro-Latvia German militias retreatedin disarray. Under the sponsorship ofSoviet Russia, on December 17, 1918, the Latvian Socialist Soviet Republicled by Latvian communist Pēteris Stučka, was set up as a regime to rival theUlmanis Latvian nationalist provisional government that had been formed onemonth earlier.

December 16, 2024

December 16, 1944 – World War II: Start of the Battle of the Bulge, where German forces attack through the Ardennes

On December 16, 1944, the Wehrmacht launched its Ardennes counter-offensive, codenamed “Operation Watch on the Rhine” (German: Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein), which involved 400,000 troops, 12,000 tanks, and 4,200 artillery pieces that had been brought up in utmost secrecy and had escaped Allied intelligence detection. Spearheaded by panzer units, the Germans advanced rapidly to a distance of some 50 miles (80 km) to come within 10 miles (16 km) of the Meuse River. The attack took the defending U.S. 1st Army completely by surprise. Overcast weather also greatly aided the German advance, as Allied planes, which controlled the skies over the battlefield, were unable to launch counter-attacks in the heavy cloud cover. The German penetration produced a salient, which the Allies called a “bulge” in their lines, leading to the Ardennes fighting being popularly called by Allied historians as the “Battle of the Bulge”.

The Allies quickly rallied and reorganized, and stopped theGerman advance in the north at Elsenborn Ridge and in the south at Bastogne. German attempts to flank Bastogne also were stopped by increasingnumbers of Allied forces being brought into the battle. The German crossing of the Meuse River,which was the key to the advance to Antwerp,also failed, as the British held onto the bridges at Dinant, Givet, and Namur. Aside from fierce Allied resistance, theGermans began encountering supply problems, and many of their tanks ground to ahalt because of fuel shortages. Then onDecember 23, 1944, improved weather conditions allowed the Allies to launch airattacks on German units and supply columns. By December 24, the German offensive had effectively stalled. Massing Allied armor bottled up the Germantanks, threatening the latter with encirclement.

On January 1, 1945, the Germans launched a new offensive,Operation North Wind, this time directed at the Alsace-Lorraine region to thesouth, and surprised U.S. 6th Army Group which had been stretched thin insupport of the Ardennes battle to the north. The German attack, aimed at recapturing Strasbourg, initially achieved some success,inflicting heavy casualties on the American defenders, but soon sputtered fromsupply shortages, particularly fuel for the tanks.

On January 3, 1945, the Allies launched a counter-attackafter a two-day delay, with U.S.1st and 3rd Armies executing a pincers movement aimed at eliminating thesalient and trapping the Germans inside the pocket. The delay allowed most German units toescape, and on January 7, Hitler finally acquiesced to his commanders andordered a general withdrawal. Fightingcontinued until January 25, with the Germans conducting a fighting retreat, inthe process also being forced to abandon most of their tanks after running outof fuel, and the Allies retaking lost territory and eliminating the salient. In February 1945, the Allies captured the Hurtgen Forest, finally breaching the SiegfriedLine there. For Hitler, the Ardennescounter-offensive was a strategic and costly failure, as Germany lostmost of its manpower reserves and armored resources in the West in an ambitiousgamble. At the outset, the German HighCommand gave little chance for the Ardennesoffensive to succeed. Its failure alsoseverely weakened German strength on the Western Front against the Alliedoffensive later that year.

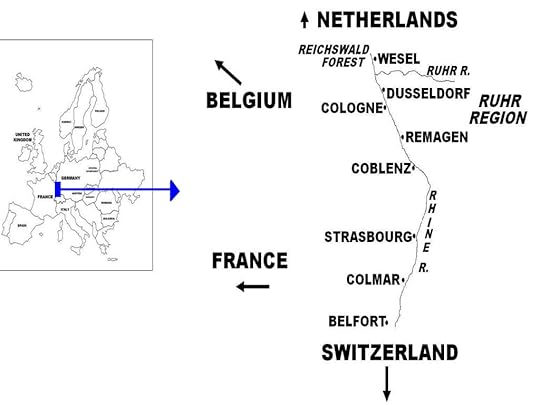

Battle for the Rhine River

Battle for the Rhine River(Taken from Defeat of Germany in the West: 1944-1945 – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In February 1945, the Western Allies regained theinitiative, and attacked on a broad front toward the Rhine River(Figure 42). This new offensive wasgreatly alarming to Hitler in particular and Germanyin general, as the Rhine served as thephysical and symbolic gateway to the German heartland. To the north, British 21st Army Groupattacked through the Reichswald Forest and reached the Rhine’s west bank, whileto the south, U.S. 9th Army, which had been attached to 21st Army Group duringthe Ardennes battle, advanced for Dusseldorf and Cologne. On February 8, the retreating Germansdestroyed the Ruhr dams, flooding the river valley below and stalling theAllied crossing of the Ruhr by two weeks. On February 23, with flood waters receding, U.S. 9th Army crossed the Ruhr, and on March 2,it reached its objective on the Rhine’s westbank.

Further to the south, U.S.3rd Army reached the Rhine at Coblenz, U.S. 7th Army at Strastbourg, and the FrenchArmy at Colmar. By early March 1945, the Allies had brokenthrough to the Rhine’s west bank at manypoints. Hitler refused the pleas byGerman field commanders to allow their troops to retreat to the east bank, andordered that they should hold their ground and fight to the death. Instead, some 400,000 German troops gave upand surrendered. By then, the totalnumber of captured Wehrmacht prisoners in the Western Front had grown to 1.3million soldiers since the start of the Normandyinvasion.

General Eisenhower and the Allied High Command believed thatattempting to cross the Rhine on a broad frontwould lead to heavy losses in personnel, and so they planned to concentrateAllied resources to force a crossing on the north in the British sector. Here also lay the shortest route to Berlin, whose capturewas definitely the greatest prize of the war. Beating out the Soviets to Berlinwas greatly desired by Prime Minister Churchill and the British High Command,which at this point, the British and American planners believed could beachieved. With Allied focus on theBritish sector in the north, U.S.12th and 6th Army Groups to the south were tasked with making secondary attacksin their sectors, tying down German troops there and thus aiding the Britishoffensive.

December 14, 2024

December 14, 1960 – The UN passes Resolution 1514 (XV) titled “Declaration of the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”

On December 14, 1960, the United Nations General Assembly(UNGA) passed Resolution 1514 (XV) titled “Declaration of the Granting ofIndependence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”, which establisheddecolonization as a fundamental principle of the UN. Five days later, on December 19, the UNreleased UNGA Resolution 1573 that recognized the right of self-determinationof the Algerian people.

On January 8, 1961, in a referendum held in France and Algeria,75% of the voters agreed that Algeriamust be allowed self-determination. TheFrench government then began to hold secret peace negotiations with theFLN. In April 1961, four retired FrenchArmy officers (Generals Salan, Challe, André Zeller, and Edmond Jouhaud, andassisted by radical elements of the pied-noir community) led the French commandin Algiers in a military uprising that deposed the civilian government of thecity and set up a four-man “Directorate”. The rebellion, variously known as the 1961 Algiers Putsch (French:Putsch d’Alger) or Generals’ Putsch (French: Putsch des Généraux), was a coupto be carried out in two phases: taking over authority in Algeria with thedefeat of the FLN and establishment of a civilian government; and overthrowingde Gaulle in Paris by rebelling paratroopers based near the French capital.

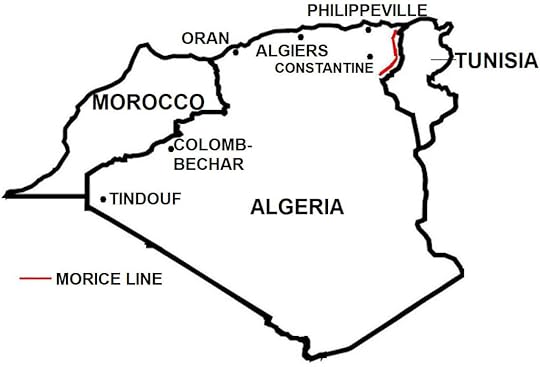

Algerian War of Independence.

Algerian War of Independence.(Taken from Algerian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

De Gaulle invoked the constitution’s provision that gave himemergency powers, declared a state of emergency in Algeria, and in a nationwidebroadcast on April 23, appealed to the French Army and civilian population toremain loyal to his government. TheFrench Air Force flew the empty air transports from Algeriato southern France toprevent them from being used by rebel forces to invade France, while the French commands in Oran and Constantineheeded de Gaulle’s appeal and did not join the rebellion. Devoid of external support, the Algiersuprising collapsed, with Generals Challe and Zeller being arrested and laterimprisoned by military authorities, together with hundreds of other mutineeringofficers, while Generals Salan and Jouhaud went into hiding to continue thestruggle with the pieds-noirs against Algerian independence.

On April 28, 1961, in the midst of the uprising, Frenchmilitary authorities test-fired France’s first atomic bomb in the SaharaDesert, moving forward the date of the detonation ostensibly to prevent thenuclear weapon from falling into the hands of the rebel troops. The attempted coup dealt a serious blow toFrench Algeria, as de Gaulle increased efforts to end the war with the Algeriannationalists.

In May 1961, the French government and the GPRA (the FLN’sgovernment-in-exile) held peace talks at Évian, France, whichproved contentious and difficult. But onMarch 18, 1962, the two sides signed an agreement called the Évian Accords,which included a ceasefire (that came into effect the following day) and arelease of war prisoners; the agreement’s major stipulations were: Frenchrecognition of a sovereign Algeria; independent Algeria’s guaranteeing theprotection of the pied-noir community; and Algeria allowing French militarybases to continue in its territory, as well as establishing privilegedAlgerian-French economic and trade relations, particularly in the developmentof Algeria’s nascent oil industry.

In a referendum held in France on April 8, 1962, over 90% ofthe French people approved of the Évian Accords; the same referendum held inAlgeria on July 1, 1962 resulted in nearly six million voting in favor of theagreement while only 16,000 opposed it (by this time, most of the one millionpieds-noirs had or were in the process of leaving Algeria or simply recognizedthe futility of their lost cause, thus the extraordinarily low number of “no”votes).

However, pied-noir hardliners and pro-French Algeriamilitary officers still were determined to derail the political process,forming one year earlier (in January 1961) the “Organization of the SecretArmy” (OAS; French: Organisation de l’armée secrète) led by General Salan, in a(futile) attempt to stop the 1961 referendum to determine Algerianself-determination. Organizedspecifically as a terror militia, the OAS had begun to carry out violentmilitant acts in 1961, which dramatically escalated in the four months betweenthe signing of the Évian Accords and the referendum on Algerianindependence. The group hoped that itsterror campaign would provoke the FLN to retaliate, which would jeopardize theceasefire between the government and the FLN, and possibly lead to a resumptionof the war. At their peak in March 1962,OAS operatives set off 120 bombs a day in Algiers,targeting French military and police, FLN, and Muslim civilians – thus, the warhad an ironic twist, as France and the FLN now were on the same side of theconflict against the pieds-noirs.

The French Army and OAS even directly engaged each other –in the Battle of Bab el-Oued, where French security forces succeeded in seizingthe OAS stronghold of Bab el-Oued, a neighborhood in Algiers, with combined casualties totaling 54dead and 140 injured. The OAS alsotargeted prominent Algerian Muslims with assassinations but its main target wasde Gaulle, who escaped many attempts on his life. The most dramatic of the assassinationattacks on de Gaulle took place in a Parissuburb where a group of gunmen led by Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, a Frenchmilitary officer, opened fire on the presidential car with bullets from theassailants’ semi-automatic rifles barely missing the president. Bastien-Thiry, who was not an OAS member, wasarrested, put on trial, and later executed by firing squad.

In the end, the OAS plan to provoke the FLN into launchingretaliation did not succeed, as the Algerian revolutionaries adhered to theceasefire. On June 17, 1962, the OAS theFLN agreed to a ceasefire. Theeight-year war was over. Some 350,000 toas high as one million people died in the war; about two million AlgerianMuslims were displaced from their homes, being forced by the French Army torelocate to guarded camps.

December 13, 2024

December 13, 1942 – World War II: Second day of Operation Winter Storm, the German attempt to relieve the trapped forces at Stalingrad

In early December 1942, General Erich von Manstein,commander of the newly formed German Army Group Don, which was tasked withsecuring the gap between German Army Groups A and B, was ready to launch arelief operation to Stalingrad. Began on December 12 under Operation WinterStorm, German Army Group Don succeeded in punching a hold in the Soviet ringand advanced rapidly, pushing aside surprised Red Army units, and came towithin 30 miles of Stalingrad on December 19. Through an officer that was sent to Stalingrad,General Manstein asked General Paulus to make a break out towards Army GroupDon; he also sent communication to Hitler to allow the trapped forces to breakout. Hitler and General Paulus bothrefused. General Paulus cited the lackof trucks and fuel and the poor state of his troops to attempt a break out, andthat his continued hold on Stalingrad would tie down large numbers of Sovietforces which would allow German Army Group A to retreat from the Caucasus.

On December 23, 1942, Manstein canceled the relief operationand withdrew his forces behind German lines, forced to do so by the threat ofbeing encircled by Soviet forces that meanwhile had launched Operation LittleSaturn. Operation Little Saturn was amodification of the more ambitious Operation Saturn, which aimed to trap GermanArmy Group A in the Caucasus, but was rapidly readjusted to counter GeneralManstein’s surprise offensive to Stalingrad. But Operation Little Saturn, the Sovietencirclement of Stalingrad, and the trapped Axis forces so unnerved Hitler thaton his orders, German Army Group A hastily withdrew from the Caucasusin late December 1942. German 17th Armywould continue to hold onto the Taman Peninsula in the Black Sea coast, and planned to usethis as a jump-off point for a possible future second attempt to invade the Caucasus.

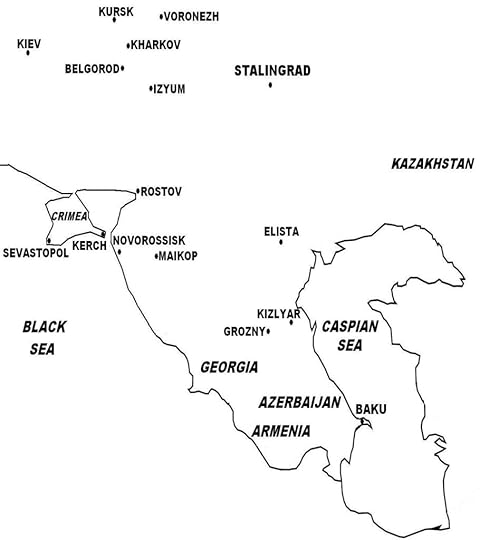

Case Blue.

Case Blue.(Taken from Battle of Stalingrad – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Meanwhile to the north, German Army Group B, tasked withcapturing Stalingrad and securing the Volga, began its advance to the Don River on July 23, 1942. The German advance was stalled by fierceresistance, as the delays of the previous weeks had allowed the Soviets tofortify their defenses. By then, theGerman intent was clear to Stalin and the Soviet High Command, which thenreorganized Red Army forces in the Stalingradsector and rushed reinforcements to the defense of the Don. Not only was German Army Group B delayed bythe Soviets that had began to launch counter-attacks in the Axis’ northernflank (which were held by Italian and Hungarian armies), but also byover-extended supply lines and poor road conditions.

On August 10, 1942, German 6th Army had moved to the westbank of the Don, although strong Soviet resistance persisted in the north. On August 22, German forces establishedbridgeheads across the Don, which was crossed the next day, with panzers andmobile spearheads advancing across the remaining 36 miles of flat plains to Stalingrad. OnAugust 23, German 14th Panzer Division reached the VolgaRiver north of Stalingradand fought off Soviet counter-attacks, while the Luftwaffe began a bombingblitz of the city that would continue through to the height of the battle, whenmost of the buildings would be destroyed and the city turned to rubble.

On August 29, 1942, two Soviet armies (the 62nd and 64th)barely escaped being encircled by the German 4th Panzer Army and armored unitsof German 6th Army, both escaping to Stalingrad and ensuring that the battlefor the city would be long, bloody, and difficult.

On September 12, 1942, German forces entered Stalingrad, starting what would be a four-month longbattle. From mid-September to earlyNovember, the Germans, confident of victory, launched three major attacks tooverwhelm all resistance, which gradually pushed back the Soviets east towardthe banks of the Volga.

By contrast, the Soviets suffered from low morale, but werecompelled to fight, since they had no option to retreat beyond the Volga because of Stalin’s “Not one step back!”order. Stalin also (initially) refusedto allow civilians to be evacuated, stating that “soldiers fight better for analive city than for a dead one”. Hewould later allow civilian evacuation after being advised by his top generals.

Soviet artillery from across the Volgaand cross-river attempts to bring in Red Army reinforcements were suppressed bythe Luftwaffe, which controlled the sky over the battlefield. Even then, Soviet troops and suppliescontinued to reach Stalingrad, enough to keepup resistance. The ruins of the cityturned into a great defensive asset, as Soviet troops cleverly used the rubbleand battered buildings as concealed strong points, traps, and killingzones. To negate the Germans’ airsuperiority, Red Army units were ordered to keep the fighting lines close tothe Germans, to deter the Luftwaffe from attacking and inadvertently causingfriendly fire casualties to its own forces.

The battle for Stalingradturned into one of history’s fiercest, harshest, and bloodiest struggles forsurvival, the intense close-quarter combat being fought building-to-buildingand floor-to-floor, and in cellars and basements, and even in the sewers. Surprise encounters in such close distancessometimes turned into hand-to-hand combat using knives and bayonets.

By mid-November 1942, the Germans controlled 90% of thecity, and had pushed back the Soviets to a small pocket with four shallowbridgeheads some 200 yards from the Volga. By then, most of German 6th Army was lockedin combat in the city, while its outer flanks had become dangerouslyvulnerable, as they were protected only by the weak armies of its Axispartners, the Romanians, Italians, and Hungarians. Two weeks earlier, Hitler, believingStalingrad’s capture was assured, redeployed a large part of the Luftwaffe tothe fighting in North Africa.

Unbeknown to the Germans, in the previous months, the SovietHigh Command had been sending large numbers of Red Army formations to the northand southeast of Stalingrad. While only intending to use these units insporadic counter-attacks in support of Stalingrad, by November 1942, Stalin andhis top generals had reorganized these forces for a major counter-offensivecodenamed Operation Uranus involving an enormous force of 1.1 million troops,1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,300 planes, aimed at cutting offand encircling German 6th Army and units of 7th Panzer Army in Stalingrad. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler ignored the warning of his general staff, as by now he wasfirmly set on taking Stalingrad at all costs.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet High Command launchedOperation Uranus, a double envelopment maneuver, with the Soviet SouthwesternFront attacking the Axis northern flank held by the Romanian 3rd Army. The next day, the Soviet Stalingrad Frontthrust from the south of the Axis flank, with the brunt of the attack fallingon Romanian 4th Army. The two Romanian Armies, lacking sufficient anti-tankweapons and supported only with 100 obsolete tanks, were overwhelmed by sheernumbers, and on November 22, the two arms of the Soviet pincers linked up atKalach. German 6th Army, elements of 4thPanzer Army, and remnants of the Romanian armies, comprising some250,000-300,000 troops, were trapped in a giant pocket in Stalingrad.

The German High Command asked Hitler to allow the trappedforces to make a break out, which was refused. Also on many occasions, General Friedrich Paulus, commander of German6th Army, made similar appeals to Hitler, but was turned down. Instead, on November 24, 1942, Hitler advisedGeneral Paulus to hold his position at Stalingraduntil reinforcements could be sent or a new German offensive could break theencirclement. In the meantime, thetrapped forces would be supplied from the air. Hitler had been assured by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering that the 700tons/day required at Stalingrad could bedelivered with German transport planes. However, the Luftwaffe was unable to deliver the needed amount, despitethe addition of more transports for the operation, and the trapped forces in Stalingrad soon experienced dwindling supplies of food,medical supplies, and ammunition. Withthe onset of winter and the temperature dropping to –30°C (–22°F), anincreasing number of Axis troops, yet without adequate winter clothing,suffered from frostbite. At this timealso, the Soviet air force had began to achieve technological and combat paritywith the Luftwaffe, challenging it for control of the skies and shooting downincreasing numbers of German planes.

Meanwhile, the Red Army strengthened the cordon aroundStalingrad, and launched a series of attacks that slowly pushed the trappedforces to an ever-shrinking perimeter in an area just west of Stalingrad.

In early December 1942, General Erich von Manstein,commander of the newly formed German Army Group Don, which was tasked withsecuring the gap between German Army Groups A and B, was ready to launch arelief operation to Stalingrad. Began on December 12 under Operation WinterStorm, German Army Group Don succeeded in punching a hold in the Soviet ringand advanced rapidly, pushing aside surprised Red Army units, and came towithin 30 miles of Stalingrad on December 19. Through an officer that was sent to Stalingrad,General Manstein asked General Paulus to make a break out towards Army GroupDon; he also sent communication to Hitler to allow the trapped forces to break out. Hitler and General Paulus both refused. General Paulus cited the lack of trucks andfuel and the poor state of his troops to attempt a break out, and that hiscontinued hold on Stalingrad would tie down large numbers of Soviet forceswhich would allow German Army Group A to retreat from the Caucasus.

On December 23, 1942, Manstein canceled the relief operationand withdrew his forces behind German lines, forced to do so by the threat ofbeing encircled by Soviet forces that meanwhile had launched Operation LittleSaturn. Operation Little Saturn was amodification of the more ambitious Operation Saturn, which aimed to trap GermanArmy Group A in the Caucasus, but was rapidly readjusted to counter GeneralManstein’s surprise offensive to Stalingrad. But Operation Little Saturn, the Sovietencirclement of Stalingrad, and the trapped Axis forces so unnerved Hitler thaton his orders, German Army Group A hastily withdrew from the Caucasusin late December 1942. German 17th Armywould continue to hold onto the Taman Peninsula in the Black Sea coast, and planned to usethis as a jump-off point for a possible future second attempt to invade the Caucasus.

Meanwhile in Stalingrad, byearly January 1943, the situation for the trapped German forces grew desperate. On January 10, the Red Army launched a majorattack to finally eliminate the Stalingradpocket after its demand to surrender was rejected by General Paulus. On January 25, the Soviets captured the lastGerman airfield at Stalingrad, and despite theLuftwaffe now resorting to air-dropping supplies, the trapped forces ran low onfood and ammunition.

With the battle for Stalingradlost, on January 31, 1943, Hitler promoted General Paulus to the rank of FieldMarshal, hinting that the latter should take his own life rather than becaptured. Instead, on February 2,General Paulus surrendered to the Red Army, along with his trapped forces,which by now numbered only 110,000 troops. Casualties on both sides in the battle of Stalingrad, one of thebloodiest in history, are staggering, with the Axis losing 850,000 troops, 500tanks, 6,000 artillery pieces, and 900 planes; and the Soviets losing 1.1million troops, 4,300 tanks, 15,000 artillery pieces, and 2,800 planes. The German debacle at Stalingrad and withdrawalfrom the Caucasus effectively ended Case Blue,and like Operation Barbarossa in the previous year, resulted in another Germanfailure.

December 12, 2024

On December 12, 1915 – China’s President Yuan Shikai announces his plan to restore the monarchy with himself as “Emperor of the Chinese Empire”

In late 1915, Yuan Shikai, President of the Republic ofChina, made plans to return the country to a monarchy. He reasoned that the 1911 Revolution that hadtoppled the Qing dynasty, and the ensuing republican government, were divisive,transitory phases, and that only a monarchy could restore order and unity tothe nation. In November 1915, a “RepresentativeAssembly” was formed to study the matter, which subsequently issued manypetitions to Yuan to become emperor. After pretending to refuse these petitions, on December 12, 1915, Yuanaccepted, and named himself “Emperor of the Chinese Empire”. Yuan’s reign, as well as the country’s returnto a monarchy as the “Empire of China”, was set to commence officially onJanuary 1, 1916, when Yuan would perform the accession rites.

(Taken from China (1911-1928): Xinhai Revolution, Fragmentation, and Struggle for Reunification – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Yuan Shikai in Power Fromthe outset, tensions existed between the pro-Sun groups, led by the Tongmenhui,and President Yuan and his supporters. To counter Yuan’s power base which was in the north, on February 14,1912, the provisional Senate voted to make Nanjing the capital of the republic. However, two weeks later, mutinous BeiyangArmy units rioted in Beijing. Yuan, who most likely masterminded thedisturbance, announced that he would remain in Beijing to guard against future unrest. The provisional Senate thus reconvened, andin another vote taken in April 1912, named Beijing as the capital of the republic.

President Yuan soon gained full control of government, andappeared intent on extending his powers. To counter Yuan and also prepare for the upcoming parliamentaryelections, in August 1912, Sun’s supporters formed the Kuomintang (KMT,English: Chinese Nationalist Party), merging the Tongmenhui and five smallerorganizations. In National Assemblyelections held in December 1912-January 1913, the KMT won a decisive victory,taking the most number of seats in both legislative houses over its rivals,including the pro-Yuan Republican Party.

Song Jiaoren, a leading KMT politician who had campaignedstrongly against Yuan and had vowed to reduce Yuan’s powers throughlegislation, appeared headed to become Prime Minister, and thus would form anew Cabinet. But in March 1913, he wasassassinated, perhaps under Yuan’s orders. When the newly elected National Assembly convened, the KMT-dominatedlegislature moved to enact measures to curb Yuan’s powers, and prepared toformulate a permanent constitution and hold national elections for thepresidency. Yuan now moved to destroythe political opposition, while his opponents in the south grew more militant –as a result, Chinabegan to fracture politically.

In July 1913, many southern provinces rose up in rebellion(sometimes called Sun Yat-sen’s “Second Revolution”), this time againstYuan. The Beiyang government (as thegovernment in Beijingwas called during the period 1912-1927) was militarily prepared, as Yuan hadrecently received a foreign loan which he used to build up his BeiyangArmy. In September 1913, Yuan’s forcescrushed the rebellion, and captured the insurgent strongholds in Nanchang and Nanjing,and forced Sun and other KMT leaders to flee into exile abroad.

In October 1913, the now intimidated National Assemblyelected Yuan as president of the republic for a five-year term. Yuan proceeded to break up all politicalopposition, first removing, coercing, or bribing KMT provincial officials. Then in November 1913, he dissolved the KMTand expelled KMT legislators from the National Assembly. As these expulsions caused the legislature tofail to reach a quorum to reconvene, in January 1914, Yuan dissolved theNational Assembly altogether. In itsplace, Yuan formed a quasi-legislative body of 66 of his supporters, who drewup and passed a “constitutional compact”, a new charter which replaced the 1912provisional constitution, and which gave Yuan unlimited powers in political,military, foreign affairs, and financial policy decisions. In December 1914, Yuan’s presidential tenurewas extended to ten years, with no terms limits –Yuan now ruled as a dictator.

Then in late 1915, Yuan made plans to return the country toa monarchy. He reasoned that the 1911Revolution that had toppled the Qing dynasty, and the ensuing republicangovernment, were divisive, transitory phases, and that only a monarchy couldrestore order and unity to the nation. In November 1915, a “Representative Assembly” was formed to study thematter, which subsequently issued many petitions to Yuan to becomeemperor. After pretending to refusethese petitions, on December 12, 1915, Yuan accepted, and named himself“Emperor of the Chinese Empire”. Yuan’sreign, as well as the country’s return to a monarchy as the “Empire of China”,was set to commence officially on January 1, 1916, when Yuan would perform theaccession rites.

Widespread protests broke out across much of China. Having experienced great repression under theQing dynasty, the Chinese people vehemently opposed the return to amonarchy. On December 25, 1915, themilitary governor of Yunnan Province declared hisprovince’s secession from the Beiyang government, and prepared for war. In rapid order, other provinces also seceded,including Guizhou, Guangxi,Guangdong, Shandong,Hunan, Shanxi,Jiangxi, and Jiangsu. The decisive showdown between Yuan’s army and forces of the rebellingprovinces took place in Sichuan Province, where rebel forces (under Yunnan Province’sNational Protection Army) dealt Yuan’s army a decisive defeat. During the fighting, Beiyang generals, whoalso opposed Yuan’s imperial ambitions, did not exert great effort to defeatthe rebel forces. In fact, Beiyang Armycommanders had already stopped supporting Yuan. Furthermore, while the foreign powers recognized the Beiyang regime asthe official government over China,Yuan’s planned monarchy received virtually no international support. Isolated and forced to postpone his accessionrites, Yuan finally abandoned his imperial designs on March 22, 1916. His political foes then also pressed him tostep down as president of the republic. Yuan died three months later, in June 1916, with his crumblinggovernment already unable to hold onto much of the country.

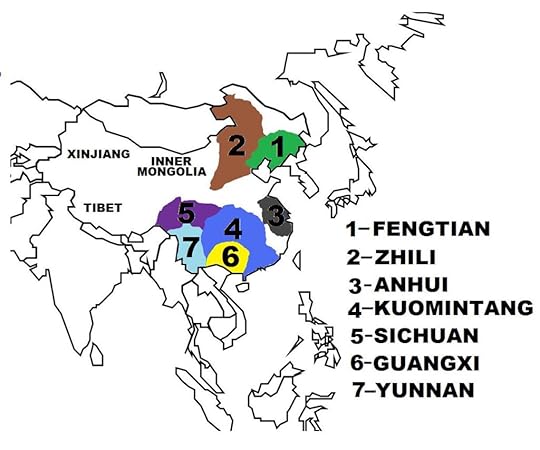

Major warlord cliques during China’s period of fragmentation.

Major warlord cliques during China’s period of fragmentation.Fragmentation,Warlordism, and Struggle for Reunification After Yuan’s death, Chinafragmented politically, and entered into a long period of warlordism. Provinces and regions fell under the controlof a military strongman, called a warlord, who ruled virtually independent of,or were only nominally subservient to the Beiyang government. China’scentral government in Beijingpractically ceased to exist.

The origin of warlordism can be traced to the Qing’s militaryreforms, which focused on strengthening provincial armies (rather than onbuilding up a single centralized national army), and the period of Yuan’sconsolidation of power. Yuan had giventhe local civilian governments the power over the military, thereby producingcivilian-military administrators.

Hundreds of warlords appeared across China. They had varying strengths and control overlocal, provincial, or regional jurisdictions. Individual warlords, even the most powerful, did not have enough power todefeat all the other warlords, and achieve their ultimate goal of reunifying China. Consequently, warlords often banded togetherto form regional cliques. Dozens of suchcliques formed and ruled vast regions.

Even then, all the warlords acknowledged that whoever ofthem controlled Beijinghad the greatest authority. This was sofor a number of reasons: the Beiyang government continued to be recognized bythe foreign powers as the legitimate authority in China, it could apply for foreignloans, and it collected customs duties.

The Beiyang Army itself also fragmented into three competingwarlord cliques: Anhuiclique, Zhili clique, and Fengtian clique. These three cliques became the most powerful of the warlord groups, andsubsequently vied with each other for control of Beijing, either through politicalmaneuverings or outright warfare. Thisperiod of internecine strife in Chinais known as the Warlord Era, spanning the years 1916-1928.

December 11, 2024

December 11, 1981 – Salvadoran Civil War: Government forces perpetrate the El Mozote Massacre

A Salvadoran military unit, the Atlacatl Battalion, whosecommanders were trained in the U.S. Army-run School of the Americas, wasparticularly feared by the rural population during the Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992). In December 1981, in a major ground sweep inrebel-held areas in Morazan Province, the AtlacatlBattalion became involved in the so-called El Mozote Massacre, which took placein December 11, 1981, where some 700 to 900 residents were killed. These soldiers are also believed to havecarried out the El Calabozo Massacre, which took place on August 21-22, 1982,where, on the bank of the Amatitán River, located in SanVicente Province, some 200 fleeing civilians were shot and killed. The killings were prompted by the perceptionthat these civilians were members of or actively supported the insurgency.

Map showing location of El Salvador in Central America.

Map showing location of El Salvador in Central America.(Taken from Salvadoran Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and the Caribbean)

Background Duringthe 1970s, El Salvadorexperienced great social unrest as a result of a number of factors: an unstablepolitical climate, economic problems, an entrenched system of economic andsocial inequalities, and a growing population competing for an increasinglylimited amount of resources. Thelong-repressed lower social classes, which form the vast majority of thepopulation, had become radicalized, and advocated both militant and violentmethods of expression. In turn, thegovernment imposed harsh measures against threats to its authority.

At the heart of the conflict was the country’s economicallypolarized social classes, the unequal distribution of wealth, resources, andpower between the small Spanish-descended elite and the vast majority ofAmerindian and mestizo (mixed American-European descendants) populations. Sincethe colonial era when the Spanish Crown gave out vast tracts of lands topersonal favorites through royal patents, just 2% of the population (theso-called “Fourteen Families”) owned 60% of all arable land, which subsequentlywas converted to latifundia, i.e. vast plantations that produced coffee beans,and later, sugarcane and cotton, for the lucrative export market. Some 60% of the rural population did not ownland, and of those who did, 95% of them owned farmlands too small to subsiston.

Apart from controlling the economy, the biggest landownersheld a monopoly on the governmental, political and military infrastructures ofthe country. Government policies favoredthe oligarchy and thus widened the economic gap, limiting available resourcesand opportunities to the lower classes, and relegating the vast majority tobecome (exploited) plantation farm hands in the primarily agricultural economythat existed for much of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In 1932, peasants in the western provinces, supported by thenascent Salvadoran Communist Party, rose up in rebellion because of economichardships caused by the ongoing Great Depression. Government forces put down the rebellion andthen carried out a campaign of extermination against the Pipil indigenouspopulation, whom they believed were communists who had supported the uprisingthat was aimed at overthrowing the government. Some 30,000 Pipil civilians were killed in the military repression.