Daniel Orr's Blog, page 8

October 18, 2024

October 18, 1973 – Yom Kippur War: Israeli forces cross the Suez Canal

An Israeli armored division in the Sinai advanced to theSuez Canal in order to establish a crossing and to protect the Israeli forcesin Egyptfrom being cut off. Egyptian tank unitsmet the Israeli advance. In an intensetwo-day encounter that saw nighttime tank battles at very close range and costhundreds of soldier deaths and 180 tanks destroyed, Israeli forces succeeded ingaining a toehold on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. On October 18, 1973, the Israelis laid down aroller bridge to the other side; soon, infantry and armored units were crossinginto Egypt.

The objectives of the Israeli offensives into Egypt were forone armored division to move north and capture the city of Ismailia to cut offEgypt’s Second Army across the Suez Canal, and for another armored division,flanked by an auxiliary third armored unit, to head south and take the city ofSuez to isolate the Egypt’s Third Army across the channel.

The Israeli crossings caught the Egyptians off-guard. Consequently, the Israelis made rapid advance,beating back the Egyptian forces in several battles and penetrating 20 milesinto Egyptalong a 25-mile axis. In their drivetoward Ismailia,the Israelis overran the Egyptian lines of defense in a series of armoredbattles. By October 21, they were withinsight of the city. Egyptian resistancesoon intensified, and an Israeli attempt to encircle the city was foiled. The Israeli offensive finally was stopped tenkilometers off Ismailia. The Israelis had failed to cut off theEgyptian Second Army whose supply and communication lines to Ismailia remained secure.

Meanwhile, the Israeli advance to the city of Suez saw many tactical,disorganized battles where the Egyptian forces were thrown back. On October 22, the UN imposed a ceasefire,which was not respected as fighting continued, with the Egyptians and Israelisaccusing each other of continuing hostilities. The Israelis advanced further south, widening their areas of control andcutting off the Egyptian Third Army in the Sinai. The Israelis gained control of sections of Suez City;on October 25, an armored unit captured Adabiya, the Israelis’ farthestsouthward advance.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background of the YomKippur War With its decisive victory in the Six-Day War (previous article)in June 1967, Israel gainedcontrol of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt,the Golan Heights from Syria,and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights wereintegral territories of Egyptand Syria,respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, togetherwith other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”,that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant thatonly armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula andGolan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently wasnot received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egypt carriedout numerous small attacks against Israeli military and government targets inthe Sinai. In what is now known as the “Warof Attrition”, Egypt wasdetermined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israel towithdraw from the Sinai. By way ofretaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria,Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel,and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly becameinvolved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israeland Egyptto agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’shard-line president, passed away. Succeeding as Egypt’shead of state was Vice-President Anwar Sadat, who began a dramatic shift inforeign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchlyhostile to Israel,President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeliconflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations(UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign apeace treaty with Israeland recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meirrefused to negotiate. President Sadat,therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging theIsraelis from the Sinai. He decided thatan Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israel to seethe need for negotiations. Egypt beganpreparations for war. Large amounts ofmodern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, butineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carriedout a number of ruses. The Egyptian Armyconstantly conducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by theIsraelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoriceventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egyptunderreported the true strength of its armed forces. The government also announced maintenance andspare parts problems with its war equipment and the lack of trained personnelto operate sophisticated military hardware. Furthermore, when President Sadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egypt in July 1972, Israel believed that the EgyptianArmy’s military capability was weakened seriously. In fact, thousands of Soviet personnelremained in Egyptand Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syriancounterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized forwar.

Israel’sintelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the dateof the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbersof Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egyptand Syriaattacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiersand the entire Israeli Air Force. However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting awar and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carryingout a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War)to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur(which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, whenmost Israeli soldiers were on leave.

October 17, 2024

October 17, 1912 – First Balkan War: Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece declare war on the Ottoman Empire

On October 8, 1912, Montenegro,which had territorial ambitions on the sanjak (district) of Novi Prazar,declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The rest of the Balkan League then issued ajoint ultimatum on the Ottoman government, which contained a demand that theOttomans withdraw their troops from the frontier regions. When the Ottomans rejected the ultimatum, Serbia, Bulgaria,and Greecedeclared war on October 17, 1912.

In the war, the Ottomans fought from a disadvantageousposition. Their forces in Rumelia wereoutnumbered by 3:1, they had to defend a long, hostile border on three sidesfrom their Balkan enemies who could strike at any point along the border, andsuccess in sending reinforcements to Rumelia relied on the Ottoman Navyachieving superiority in the Aegean Seaagainst the Greek fleet.

(Taken from First Balkan War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background of theFirst Balkan War At the start of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empirewas a spent force, a shadow of its former power of the fifteenth and sixteenthcenturies that had struck fear in Europe. The empire did continue to hold vastterritories, but only tolerated by competing interests among the Europeanpowers who wanted to maintain a balance of power in Europe. In particular, Britainand Francesupported and sometimes intervened on the side of the Ottomans in order torestrain expansionist ambitions of the emerging giant, the Russian Empire.

In Europe, the Ottomans hadlost large areas of the Balkans, and all of its possessions in central andcentral eastern Europe. By 1910, Serbia, Bulgaria,Montenegro, and Greecehad gained their independence. As aresult, the Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainlandwas Rumelia (Map 4), a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace,to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast. And even Rumelia itself was coveted by thenew Balkan states, as it contained large ethnic populations of Serbians,Belgians, and Greeks, each wanting to merge with their mother countries.

The Russian Empire, seeking to bring the Balkans into itssphere of influence, formed a military alliance with fellow Slavic Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. In March 1912, a Russian initiative led to aSerbian-Bulgarian alliance called the Balkan League. In May 1912, Greece joined the alliance when theBulgarian and Greek governments signed a similar agreement. Later that year, Montenegrojoined as well, signing separate treaties with Bulgariaand Serbia.

The Balkan League was envisioned as an all-Slavic alliance,but Bulgaria saw the need tobring in Greece, inparticular the modern Greek Navy, which could exert control in the Aegean Seaand neutralize Ottoman power in the Mediterranean Sea,once fighting began. The Balkan Leaguebelieved that it could achieve an easy victory over the Ottoman Empire, for the following reasons. First, the Ottomans currently were locked in a war with the ItalianEmpire in Tripolitania (part of present-day Libya), and were losing; andsecond, because of this war, the Ottoman political leadership was internallydivided and had suffered a number of coups.

Most of the major European powers, and especially Austria-Hungary, objected to the Balkan Leagueand regarded it as an initiative of the Russian Empire to allow the RussianNavy to have access to the Mediterranean Sea through the Adriatic Coast. Landlocked Serbiaalso had ambitions on Bosnia and Herzegovinain order to gain a maritime outlet through the AdriaticCoast, but was frustrated when Austria-Hungary, which had occupiedOttoman-owned Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1878, formally annexed theregion in 1908.

The Ottomans soon discovered the invasion plan and preparedfor war as well. By August 1912,increasing tensions in Rumelia indicated an imminent outbreak of hostilities.

October 16, 2024

October 16, 1949 – Greek Civil War: The Greek Communist Party announces a “temporary ceasefire”

By early 1949, the Greek Armed Forces held an overwhelming manpower and material advantage over the communist rebels of the DSE (Democratic Army of Greece; Greek transliteration: Dimokratikos Stratos Elladas) in the Greek Civil War. As well, American weapons continued to arrive in Greece. By then, the rebels were hard pressed to gain new recruits, more so since their civilian base of support had been resettled into towns, while other communist sympathizers had been executed, jailed or had fled into exile abroad.

In January 1949, in what became the first of a series ofbattles that ended the war, the Greek Army inflicted a decisive defeat on therebels in the Peloponnese region, and gained full control of southern Greece. Then in June, another powerful offensiveinvolving 70,000 troops cleared central Greece of insurgents, who wereforced to retreat north. In August 1949,the Greek Army launched its final offensive in northern Greece, capturing the last rebel strongholds on Mounts Grammosand Vitsi and forcing the DSE to retreat to Albaniaand Bulgaria. Small scattered rebel units in Greece soon also succeeded in escaping from Greece. Most of the KKE (Greek Communist Party; Greektransliteration: Kommounistikó KómmaElládas) and DSE exiles eventually settled in Eastern Bloc countries andthe Soviet Union. On October 16, 1949, the KKE announced a“temporary ceasefire” which, unknown at the time, led to a permanent end of thewar.

Some 158,000 persons died in the war, while one millionpeople were displaced from their homes. In the following years, Greecerebuilt its devastated economy, which was achieved partly by American financialassistance under the European Recovery Program (more commonly known as theMarshall Plan).

As a result of the civil war, Greece experienced a long period ofpolitical instability caused by fractious politics between the political leftand right, which culminated in a military coup in April 1967 that established aright-wing military junta. Greece remained under the sphere of the Westerndemocracies, joined NATO in 1952, and kept close military and economic tieswith the United States. In July 1974, the junta collapsed and Greece beganits transition to democracy by establishing an interim civilian government andholding free elections. Also in 1974,the monarchy was abolished in a national referendum and the country thenestablished a parliamentary republic.

(Taken from Greek Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background of theGreek Civil War The Greek Civil War has its origin in World War II, inApril 1941 when the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy,and Bulgaria invaded andoverrun Greeceand defeated and expelled the Greek and British forces. Greece’sKing George II and the Greek government fled to exile in Britain-controlled Egypt, where they set up a government-in-exilein Cairo. In Greece,the Axis partitioned the country into zones of occupation and set up acollaborationist government in Athens.

Organized resistance to the occupation began in July 1941when officers and members of the Greek Communist Party, or KKE (Greektransliteration: Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas), many of whom had been jailed byGreece’s right-wing military government before the war but had escapedfollowing the Axis invasion, secretly met and formed a unified “popular front”to fight the occupation forces and collaborationist government. This idea bore fruit when in September 1941,the KKE and three other leftist organizations formed the National LiberationFront, or EAM (Greek transliteration: Ethniko Apeleftherotiko Metopo), whoseaims were to liberate Greece,and to advance “the Greek people’s sovereign right to determine its form ofgovernment”.

In February 1942, EAM formed an armed wing, the GreekPeople’s Liberation Army, or ELAS (Greek transliteration: Ellinikós LaïkósApeleftherotikós Stratós), which carried out guerilla and sabotage operationsagainst the Axis forces and collaborationist government. Success in the battlefield allowed EAM-ELASto gain control of the Greek countryside and mountain areas, drawing activesupport from the rural population (communist and non-communists), and allowingthe resistance to grow to 50,000 fighters and 500,000 non-combat auxiliaries. Perhaps as much as three-quarters of Greekterritory came under EAM-ELAS control, although the major urban areas,including Athens,continued to be held by the Axis.

Other resistance movements (all advocating non-communistideologies) also operated during the occupation, with the two major of thesebeing the National Republican Greek League, or EDES (Greek transliteration:Ethnikos Dimokratikos Ellinikos Syndesmos, abbreviated) and the National andSocial Liberation, or EKKA (Greek transliteration: Ethniki kai KoinonikiApeleftherosis). These groups had muchsmaller militias and were less military capable of confronting the enemy thanwas EAM-ELAS. Britain provided technical andmaterial support to all Greek resistance groups, including EAM-ELAS, whosecommunist ideology were at odds with the British.

The Greek resistance groups were hostile to each other, andskirmishes broke out among them as did they against the Axisforces/collaborationist militias. TheBritish and EAM-ELAS also were wary of each other with regards to post-war Greece and thecountry’s political future. This mutualdistrust initially was set aside because of the need to fight a common enemy,but gradually increased toward war’s end when the Axis defeat became certain.

The British were concerned that EAM-ELAS, with its overtlypro-Soviet inclination, would prevail in the war and transform post-war Greece into a Marxist state aligned with the Soviet Union. Forthe British, a communist country in the Mediterranean Sea, especially one thatpotentially would allow a Soviet maritime presence through a naval agreement orthe use of ports would threaten the Suez Canal, Britain’s vital link to Indiaand other British colonies in Asia. Britain was determined that King George II shouldreturn to Greece,which would guarantee the formation of a conservative government friendly toBritish interests.

Because of its multi-party, multi-ideology origins, EAM-ELASofficially promoted a democratic policy. However, since it was dominated by the KKE (comprising the largestconstituent organization), EAM-ELAS was formed and functioned along communistlines. EAM-ELAS also was firmly opposedto the return of Greece’sgovernment-in-exile, because of fears of a return to the pre-war right-wing(i.e. repressive) regime, as well as to the return of the king, who hadsupported that regime.

In March 1944, EAM established a quasi-government called thePolitical Committee of National Liberation, or PEEA (Greek transliteration:Politiki Epitropi Ethikis Apeleftherosis), commonly known as the “MountainGovernment”. The PEEA held legislativeelections where women, for the first time in Greece, were allowed to vote. The rebel government called for continuingthe resistance against the occupation, “destruction of fascism”, and theindependence and sovereignty of Greece.

In April 1944, a mutiny broke out in Egypt among soldiers of the exiled Greek ArmedForces, who declared that the government-in-exile was irrelevant and needed tobe replaced by a new, progressive government that genuinely represented thechanges taking place in Greece. British authorities quelled the mutiny, andjailed the soldiers.

The mutiny, however, led to the end of thegovernment-in-exile. In May 1944, underBritish sponsorship, representatives from the various Greek political partiesand resistance groups met and held talks in Beirut, Lebanon. These talks, called the Lebanon Conference,led to the formation of a coalition government (called the government ofnational unity) led by Prime Minister Georgios Papandreou. Of the 24 posts in the new government, 6 wereallocated to EAM. The conference alsoagreed that King George’s return to Greece would be postponed andsubject to a referendum that would decide the fate of the monarchy.

By the fall of 1944, the Soviet Army had broken through in Eastern Europe. Toavoid being cut off, in October of that year, the Germans (who, by this time,were the remaining occupation forces in Greece) retreated north. With the Germans out of Greece, the British soon arrived in Athens, followed by PrimeMinister Papandreou’s government which began to take over the administrativeduties left behind by the fallen collaborationist regime.

One month earlier, the various armed resistance groups hadagreed to subordinate their militias under the command of the British Army. EAM-ELAS controlled much of Greece but wanted to preserve Allied unity andtherefore did not pre-empt the British by occupying and taking over Athens, although it wascapable of doing so.

Unbeknown to EAM-ELAS, however, the fate of post-war Greece already had been decided secretly by Britain and the Soviet Union. In a number ofmeetings with British officials, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had indicated thatthe Soviet Union was not interested in Greece. In October 1944, in what became known as thePercentages Agreement, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Stalindelineated their respective countries’ post-war spheres of influence in theBalkans and parts of Eastern Europe: Yugoslavia and Hungary would be splitevenly between them; Romania and Bulgaria would have Soviet majority control;and Greece would fall under British majority control.

October 15, 2024

October 15, 1979 – A military coup takes place in El Salvador, sparking a twelve-year civil war

El Salvador in Central America

El Salvador in Central AmericaOn October 15, 1979, a group of army officers, alarmed thatthe increasing violence was creating conditions favorable to a communisttake-over similar to that which occurred in Nicaragua, carried out a coup thatdeposed General Romero. A five-membercivilian and military junta, called the Revolutionary Junta Government (JRG;Spanish: Junta Revolucionaria de Gobierno)was formed to rule the country until such that time that elections could beheld. In March 1980, after somerestructuring, Duartejoined the junta and eventually took over its leadership to become thecountry’s de facto head of state. Thejunta was openly supported by the United States,which viewed Duarte’s centrist politics as thebest chance to preserve democracy in El Salvador.

However, neither the coup nor the junta altered the powerstructures, and the military continued to wield full (albeit covert) authorityover state matters. The juntaimplemented agrarian reform and nationalized some key industries, but theseprograms were strongly opposed by the oligarchy. Militias and “death squads” that the juntaordered the military to disband simply were replaced with other armed groups. The years 1980 and 1981 saw a great increasein the military’s suppression of dissent.

(Taken from Salvadoran Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars and Conflicts in the Americas and the Caribbean)

The Civil War IntensifiesOn March 24, 1980, Monsignor Oscar Romero, the Archbishop of San Salvador, was killedwhile delivering religious services. Archbishop Romero, like many other Salvadoran clergymen, advocatedLiberation Theology, a radical variation of Catholicism which taught that theChurch had a moral obligation to fight social and economic injustices and workfor a fair and equitable society. Twomonths before his assassination, Archbishop Romero had written an open letterto U.S. President Jimmy Carter, requesting the latter to stop providingmilitary support to the Salvadoran military. Archbishop Romero’s death also took place one day after he had called onSalvadoran soldiers to disobey their commanders and not attack civilians.

One week after Archbishop Romero’s assassination, on March30, 1980, during the Archbishop’s funeral services which were attended by some250,000 people and held at the public square near the San Salvador Cathedral,gunmen hidden in the buildings nearby opened fire on the crowd. Pandemonium broke out and in the stampedethat followed, scores of people were crushed and killed. Investigations conducted by independentorganizations following the two incidents pointed to government forces as theparty most likely to have carried out the archbishop’s murder and the attack oncivilians during the funeral services.

Archbishop Romero’s assassination greatly raisedrevolutionary fervor, and generally is cited as the event that started thecivil war, or greatly accelerated it. Many activists abandoned non-violent, political means for change andjoined the various revolutionary armed movements in the countryside.

In May 1980, the four major insurgent groups (SalvadoranCommunist Party, FPL, ERP, RN) merged to form the Unified RevolutionaryDirectorate (Spanish: DirecciónRevolucionaria Unificada), which in turn, six months later in October 1980,in Havana, Cuba under the auspices of Fidel Castro, reorganized as theFarabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN; Spanish: Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional). Another leftist organization, theRevolutionary Party of Central American Workers (PRTC; Spanish: Partido Revolucionario de los TrabajadoresCentroamericanos), joined the FMLN in December 1980.

The FMLN, together with its political wing, the DemocraticRevolutionary Front (FDR; Spanish: FrenteDemocrático Revolucionario), had as its main objectives the overthrow ofthe government through armed revolution, formation of a communist regime, andthe overhaul of the country’s social and economic infrastructures. Because of its (initially) small combatcapability, the FMLN envisaged a strategy that combined carrying out aprotracted guerilla war and economic sabotage, and derived support from itsmain base among the rural population, which could furnish new recruits, food,logistical support, and information. Combat operations were limited to ambushing army patrols, raiding remoteoutposts, and skirmishing with small army units. The insurgents also destroyed publicinfrastructures (roads, bridges, public utilities, etc.) and private properties(plantation farms, grain mills, warehouses, etc.).

The FMLN established relations with Cuba and Nicaragua,and working ties with the Soviet Union,Eastern Bloc, and other communist countries. In 1981, it received a diplomatic boost when Franceand Mexicorecognized it as a “legitimate political force”. However, the United States and most westerndemocratic countries viewed the FMLN in the Cold War context, as that of a Marxist(and terrorist) organization that was striving to overthrow a democraticgovernment in order to set up a communist regime.

In January 1981, the FMLN launched coordinated attacks inmany parts of the country, which failed in their objective (as the “finaloffensive”) to incite a popular uprising to topple the government. The rebels did, however, seize some regionsin the north, including large areas of Chalatenango and Morazan, as well asCuscatlán, Cabañas, and the mountain areas north of San Salvador centered in Guazapa. The offensive also came in the wake of therecent electoral victory of U.S. President Ronald Reagan, who had campaigned ona rigidly anti-communist platform.

President Reagan’s predecessor, President Carter, generallyhad been reluctant to provide full military support to El Salvadorbecause of the Salvadoran army’s poor human rights record. The U.S.government had even stopped U.S.aid in December 1980 following the rape and murder of three U.S. Catholic nunsand one female church lay worker by soldiers of the Salvadoran NationalGuard. President Carter did, however,resume U.S.assistance following the increasing threat of the FMLN insurgency.

Consequently, with the Reagan administration, the United States infused large sums of economic andmilitary assistance to El Salvador; the major part of the $7 billiontotal amount provided during the war took place during President Reagan’s termof office (1981-1989). Aside fromweapons, the United Statesalso sent military advisors to train the Salvadoran Armed Forces incounter-insurgency techniques that the U.S. Army had developed in the VietnamWar.

The Salvadoran Army found it difficult to tell apart themainly inconspicuous insurgents from the conspicuous rural population, and soonregarded the two groups as one and the same, i.e. the enemy, particularly inareas where the insurgency was strong. Acampaign known as “draining the sea” was carried out, i.e., the insurgency’ssupport base (the “sea”) would be targeted and eliminated, instead ofattempting to locate the rebels.

October 14, 2024

October 14, 1920 – Finnish Civil War: Finland and Soviet Russia sign the Treaty of Tartu

On October 14, 1920, Finlandand Soviet Russia signed the Treaty of Tartu (in Tartu, Estonia)at the end of the Finnish Civil War. The treaty established a commonFinnish-Russian border with some exchanges of territory: Petsamo in the north wasreturned to Finland, whileRepola and Porajarvi in Karelia went to SovietRussia.

White Finland and Red Finland during the Finnish Civil War

White Finland and Red Finland during the Finnish Civil War(Taken from Finnish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Aftermath of theFinnish Civil War In May 1918, the victorious conservative governmentreturned its capital to Helsinki. Because of the German Army’s contribution tothe military success and under the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk,Finland came under Germany’s sphere of influence, much like the other Russianterritories ceded to Germany, i.e. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus,Ukraine, and Russian Poland. Finnish-German relations drew even closer with the signing of bilateralmilitary and economic agreements. InOctober 1918, German hegemony was furthered when the Finnish Parliament,dominated by monarchists, named a German Prince, Friedrich Karl, as King ofFinland.

However, the Western Front of World War I was still beingfought. After a failed German offensivein March 1918, the Allies counterattacked, pushing back the German Army allacross the front. By November 1918, theGerman Empire verged on total collapse, both from defeat on the battlefield andby political and social unrest caused by the outbreak of the GermanRevolution. On November 9, 1918, theGerman monarchy ended when Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated the throne; an interimgovernment (which soon turned Germanyinto a republic) signed the Compiègne Armistice on November 11, 1918, endingWorld War I.

In the aftermath, Germanywas forced to relinquish its authority over Eastern Europe, including Finland. In mid-December 1916, with the departure ofthe German Army from Finland,the Finnish parliament’s plan to install a monarchy with a German prince fellapart. Finland held local elections inDecember 1918, and parliamentary elections in March 1919, paving the way forthe establishment of a republic, which officially came into existence with theratification of the Finnish constitution in July 1919. Also in July, Finland’s first president, KaarloJuho Ståhlberg, was elected into office.

Earlier in May 1919, the United States and Britainrecognized Finland’sindependence; other countries, including Denmark,Norway, Sweden, Switzerland,and Greece already hadrecognized Finland’ssovereignty a few months earlier. OnOctober 14, 1920, Finlandand Soviet Russia formally ended hostilities in the Treaty of Tartu (in Tartu, Estonia)that also established a common Finnish-Russian border.

The civil war left a lasting, bitter legacy in Finland. The widespread violence perpetrated by bothsides of the war aggravated the already socially divided Finland, asnearly every Finn was affected directly or indirectly. This polarization led to non-compromise andencouraged radicalization of elements of the right and left, into fascists andcommunists, respectively, in the following years. Ultimately, however, political moderationprevailed, allowing Finlandto emerge united politically, socially, and economically. Furthermore, in the 1930s, the countryexperienced high economic growth, with traditional industries growing and newones emerging. Agricultural reforms alsotransformed the countryside – by the 1930s, some 90% of previously landlessfarmers owned their farmlands. Also inthe 1930s, the growing threats from Germanyand the Soviet Union further bound Finnstoward nationalist unity.

October 13, 2024

October 13, 1943 – World War II: Italy declares war on Germany

In July 1943, Benito Mussolini was fired as Prime Minister and imprisoned after the Allies invaded Sicily. A new Italian government was formed, which opened secret peace talks with the Allies. This led the Armistice of Cassibile, where Italy surrendered to the Allies. Fearing German reprisal, King Victor Emmanuel II and the new government fled to Allied-controlled southern Italy, where they set up their headquarters. On October 13, 1943, Italy declared war on Germany. But as a consequence of the armistice, German forces took over power in much of Italy.

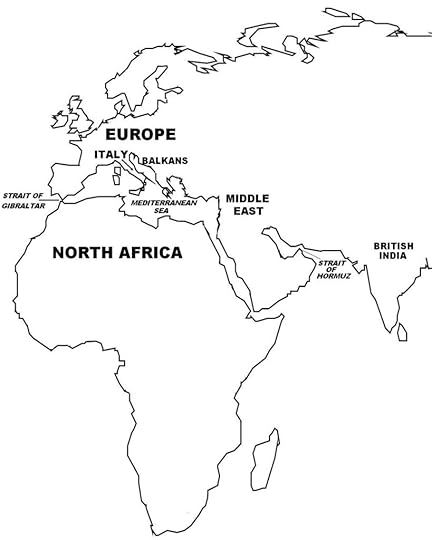

Mussolini planned to establish an Italian Empire that would control southern Europe, northern Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Middle East.

Mussolini planned to establish an Italian Empire that would control southern Europe, northern Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Middle East.(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Mussolini and HisQuest for an Italian Empire In the midst of political and social unrest inOctober 1922, Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party came to power in Italy, with Mussolini being appointed as PrimeMinister by Italy’sKing Victor Emmanuel III. Mussolini, whowas popularly called “Il Duce” (“The Leader”), launched major infrastructureand social programs that made him extremely popular among his people. By 1925-1927, the Fascist Party was the onlylegal political party, the Italian legislature had been abolished, andMussolini wielded nearly absolute power, with his government a virtualdictatorship.

By the late 1920s through the 1930s, Mussolini pursued anovertly expansionist foreign policy. Hestressed the need for Italian domination of the Mediterranean region andterritorial acquisitions, including direct control of the Balkan states of Yugoslavia, Greece,Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania,and a sphere of influence in Austriaand Hungary, and colonies inNorth Africa. Mussolini envisioned a modern Italian Empire in the likeness of theancient Roman Empire. He explained that his empire would stretch fromthe “Strait of Gibraltar

[western tip of the Mediterranean Sea]

to the Strait of Hormuz [in modern-day Iran and the Arabian Peninsula]”. Although notopenly stated, to achieve this goal, Italywould need to overcome British and French naval domination of the Mediterranean Sea.

Furthermore, in the aftermath of World War I, a strongsentiment regarding the so-called “mutilated victory” pervaded among manyItalians about what they believed was their country’s unacceptably smallterritorial gains in the war, a sentiment that was exploited by the Fascistgovernment. Mussolini saw his empire asfulfilling the Italian aspiration for “spazio vitale” (“vital space”), wherethe acquired territories would be settled by Italian colonists to ease theoverpopulation in the homeland. Mussolini’s government actively promoted programs that encouraged largefamily sizes and higher birth rates.

Mussolini also spoke disparagingly about Italy’sgeographical location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about how it was“imprisoned” by islands and territories controlled by other foreign powers(i.e. France and Britain), and that his new empire would include territoriesthat would allow Italy direct access to the Atlantic Ocean in the west and theIndian Ocean in the east.

In October 1935, the Italian Army invaded independent Ethiopia,conquering the African nation by May 1936 in a brutal campaign that includedthe Italians using poison gas on civilians and soldiers alike. Italythen annexed Ethiopia intothe newly formed Italian East Africa, which included Eritreaand Italian Somaliland. Italyalso controlled Libya in North Africa as a colony.

The aftermath of Italy’sconquest of Ethiopia saw arapprochement in Italian-Nazi German relations arising from Hitler’s support ofItaly’s invasion of Ethiopia. In turn, Mussolini dropped his opposition to Germany’s annexation of Austria. Throughout the 1920s-1930s, the majorEuropean powers Britain, France, Italy, the Soviet Union and Germany, engagedin a power struggle and formed various alliances and counter-alliances amongthemselves, with each power hoping to gain some advantage in what was seen asan inevitable war. In this powerstruggle, Italystraddled the middle and believed that in a future conflict, its weight wouldtip the scales for victory in its chosen side.

In the end, it was Italy’sties with Germanythat prospered; both countries also shared a common political ideology. In the Spanish Civil War (July 1936-April1939), Italy and Germany supported the rebel Nationalist forcesof General Francisco Franco, who emerged victorious and took over power in Spain. In October 1936, Italyand Germanyformed an alliance called the Rome-Berlin Axis. Then in 1937, Italyjoined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had been signed by Germany and Japan in November 1936. In April 1939, Italymoved one step closer to forming an empire by invading Albania,seizing control of the Balkan nation within a few days. In May 1939, Mussolini and Hitler formed amilitary alliance, the Pact of Steel. Two months earlier (March 1939), Germanycompleted the dissolution and partial annexation of Czechoslovakia. The alliance between Germany and Italy,together with Japan,reached its height in September 1940, with the signing of the Tripartite Pact,and these countries came to be known as the Axis Powers.

On September 1, 1939 World War II broke out when Germany attacked Poland,which immediately embroiled the major Western powers, France and Britain,and by September 16 the Soviet Union as well (as a result of a non-aggressionpact with Germany, but notas an enemy of France and Britain). Italydid not enter the war as yet, since despite Mussolini’s frequent blustering ofhaving military strength capable of taking on the other great powers, Italy in factwas unprepared for a major European war.

Italy wasstill mainly an agricultural society, and industrial production forwar-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for vital itemssuch as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind the otherwestern powers. In military capability,Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostly obsolete by thestart of World War II, although the large Italian Navy was ably powerful andpossessed several modern battleships. Cognizant of these deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts tobuilding up Italian military strength, and by 1939, some 40% of the nationalbudget was allocated to the armed forces. Even so, Italian military planners had projected that its forces wouldnot be fully prepared for war until 1943, and therefore the sudden start ofWorld War II came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

In April-June 1940, Germanyachieved a succession of overwhelming conquests of Denmark,Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium,Luxembourg, and France. As Franceverged on defeat and with Britainisolated and facing possible invasion, Mussolini decided that the war wasover. In an unabashed display ofopportunism, on June 10, 1940, he declared war on Franceand Britain, bringing Italy into World War II on the side of Germany, andstating, “I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peaceconference as a man who has fought”.

October 12, 2024

October 12, 1971 – Iran holds extravagant celebrations for the founding of the 2,500-year old Persian Empire

From October 12–16, 1971, Iran led by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi held elaborate celebrations for the founding of the Persian Empire, the festivities being officially called “The 2,500th Year of Foundation of Imperial State of Iran”. The event aimed to present the country’s ancient civilization and history, and highlight the advances made in the modern age. The celebrations, along with other government actions, were considered anti-Islamic by the clergy and many Iranians, and would lead to the anti-royalist backlash in the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

(Taken from Iranian Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Meanwhile in Iran,the Shah continued to carry out secular programs that alienated most of thepopulation. In October 1971, tocommemorate 25 centuries since the founding of the Persian Empire, the Shahorganized a lavish program of activities in Persepolis, capital of the First PersianEmpire. Then in March 1976, the Shahannounced that Iranhenceforth would adopt the “imperial” calendar (based on the reign of Persianking Cyrus the Great) to replace the Islamic calendar. These acts, considered anti-Islamic by theclergy and many Iranians, would form part of the anti-royalist backlash in thecoming revolution.

Another paradox in a deeply conservative Muslim country wasthe government’s hosting the Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of Arts from 1967 to1977, which was meant to showcase the various forms of music, dance, drama,poetry, and film from western and eastern countries, including traditionalPersian and Iranian Shiite cultures. Thefestival’s extravagance and especially some of the avant-garde westernperformances (which were already controversial by European standards) wereoutright sacrilegious in a country where Islam was the state religion. It would be in 1977, one year before thestart of the revolution, that Ayatollah Khomeini spoke out against the artsfestival, even decrying the clerics in Tehran for not speaking out against theperformances.

Also by 1977, Iran’s decade-long period of strongeconomic growth had ended, and the country faced financial problems because ofan oil glut in the world market. Iran’soil revenues dropped sharply, forcing a cut in oil production and a rise inunemployment. Inflation and commoditiesshortages were met by the government imposing austerity measures, which in turnwere resisted by the general population.

Background of theIranian Revolution Under the Shah, Irandeveloped close political, military, and economic ties with the United States, was firmly West-aligned andanti-communist, and received military and economic aid, as well as purchasedvast amounts of weapons and military hardware from the United States. The Shah built a powerful military, at itspeak the fifth largest in the world, not only as a deterrent against the SovietUnion but just as important, as a counter against the Arab countries(particularly Iraq), Iran’s traditional rival for supremacy in the Persian Gulfregion. Local opposition and dissentwere stifled by SAVAK (Organization of Intelligence and National Security;Persian: Sāzemān-e Ettelā’āt va Amniyat-e Keshvar), Iran’s CIA-trained intelligence andsecurity agency that was ruthlessly effective and transformed the country intoa police state.

Iran, theworld’s fourth largest oil producer, achieved phenomenal economic growth in the1960s and 1970s and more particularly after the 1973 oil crisis when world oilprices jumped four-fold, generating huge profits for Iran that allowed its government toembark on massive infrastructure construction projects as well as socialprograms such as health care and education. And in a country where society was both strongly traditionalist andreligious (99% of the population is Muslim), the Shah led a government that wasboth secular and western-oriented, and implemented programs and policies thatsought to develop the country based on western technology and some aspects ofwestern culture. Iran’s push to westernize andsecularize would be major factors in the coming revolution. The initial signs of what ultimately became afull-blown uprising took place sometime in 1977.

At the core of the Shiite form of Islam in Iran is the ulama (Islamicscholars) led by ayatollahs (the top clerics) in a religious hierarchy thatincludes other orders of preachers, prayer leaders, and cleric authorities thatadministered the 9,000 mosques around the country. Traditionally, the ulama was apolitical anddid not interfere with state policies, but occasionally offered counsel or itsopinions on government matters and policies.

In January 1963, the Shah launched sweeping major social andeconomic reforms aimed at shedding off the country’s feudal, traditionalistculture and to modernize society. Theseambitious reforms, known as the “White Revolution”, included programs thatadvanced health care and education, and the labor and business sectors. The centerpiece of these reforms, however,was agrarian reform, where the government broke up the vast agriculturelandholdings owned by the landed few and distributed the divided parcels tolandless peasants who formed the great majority of the rural population. While land reform achieved some measure ofsuccess with about 50% of peasants acquiring land, the program failed to winover the rural population as the Shah intended; instead, the deeply religiouspeasants remained loyal to the clergy. Agrarian reform also antagonized the clergy, as most clerics belonged towealthy landowning families who now were deprived of their lands.

Much of the clergy did not openly oppose these reforms,except for some clerics in Qomled by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who in January 22, 1963 denounced the Shahfor implementing the White Revolution; this would mark the start of a longantagonism that would culminate in the clash between secularism and religionfifteen years later. The clerics alsoopposed other aspects of the White Revolution, including extending votingrights to women and allowing non-Muslims to hold government office, as well asbecause the reforms would reduce the cleric’s influence in education and familylaw. The Shah responded to AyatollahKhomeini’s attacks by rebuking the religious establishment as beingold-fashioned and inward-looking, which drew outrage from even moderateclerics. Then on June 3, 1963, AyatollahKhomeini launched personal attacks on the Shah, calling the latter “a wretched,miserable man” and likening the monarch to the “tyrant” Yazid I (an Islamiccaliph of the 7th century). The governmentresponded two days later, on June 5, 1963, by arresting and jailing the cleric.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s arrest sparked strong protests thatdegenerated into riots in Tehran, Qom, Shiraz,and other cities. By the third day, theviolence had been quelled, but not before a disputed number of protesters werekilled, i.e. government cites 32 fatalities, the opposition gives 15,000, andother sources indicate hundreds.

Ayatollah Khomeini was released a few months later. Then on October 26, 1964, he again denouncedthe government, this time for the Iranian parliament’s recent approval of theso-called “Capitulation” Bill, which stipulated that U.S.military and civilian personnel in Iran, if charged with committingcriminal offenses, could not be prosecuted in Iranian courts. To Ayatollah Khomeini, the law was evidencethat the Shah and the Iranian government were subservient to the United States. The ayatollah again was arrested andimprisoned; government and military leaders deliberated on his fate, whichincluded execution (but rejected out of concerns that it might incite moreunrest), and finally decided to exile the cleric. In November 1964, Ayatollah Khomeini wasforced to leave the country; he eventually settled in Najaf, Iraq,where he lived for the next 14 years.

While in exile, the cleric refined his absolutist version ofthe Islamic concept of the “Wilayat al Faqih” (Guardianship of theJurisprudent), which stipulates that an Islamic country’s highest spiritual andpolitical authority must rest with the best-qualified member (jurisprudent) ofthe Shiite clergy, who imposes Sharia (Islamic) Law and ensures that statepolicies and decrees conform with this law. The cleric formerly had accepted the Shah and the monarchy in theoriginal concept of Wilayat al Faqih; later, however, he viewed all forms ofroyalty incompatible with Islamic rule. In fact, the ayatollah would later reject all other (European) forms ofgovernment, specifically citing democracy and communism, and famously declaredthat an Islamic government is “neither east nor west”.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s political vision of clerical rule wasdisseminated in religious circles and mosques throughout Iran from audio recordings thatwere smuggled into the country by his followers and which was tolerated orlargely ignored by Iranian government authorities. In the later years of his exile, however, thecleric had become somewhat forgotten in Iran, particularly among theyounger age groups.

October 11, 2024

October 11, 1954 – First Indochina War: French forces withdraw from North Vietnam

From October 8–11, 1954, France withdrew its forces from North Vietnam below the 17th Parallel to the south, as set out in the Geneva Accords that had been signed on July 21, 1954. A stipulation in the Accords established a “provisional military demarcation line” at the 17th Parallel with a 3-mile wide demilitarized zone (DMZ) on each side of the demarcation line to separate the opposing French Union forces and the North Vietnamese communists, the Viet Minh. The Accords imposed a ceasefire, to be monitored by the International Control Commission (ICC) comprising contingents from Canada, Poland, and China.

(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Present-day Southeast Asia

Present-day Southeast AsiaAftermath By the time of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, France knew that it could not win the war, and turned its attention on trying to work toward a political settlement and an honorable withdrawal from Indochina. By February 1954, opinion polls at home showed that only 8% of the French population supported the war. However, the Dien Bien Phu debacle dashed French hopes of negotiating under favorable withdrawal terms. On May 8, 1954, one day after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, representatives from the major powers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochina states: Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and State of Vietnam, met at Geneva (the Geneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina. The Conference also was envisioned to resolve the crisis in the Korean Peninsula in the aftermath of the Korean War (separate article), where deliberations ended on June 15, 1954 without any settlements made.

On the Indochina issue, onJuly 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by theparties. The ceasefire was agreed to byFrance and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17thparallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southernzone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional militarydemarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The French and their allies in thenorthern zone departed and moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh inthe southern zone departed and moved to the northern zone (although somesouthern Viet Minh remained in the south on instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarized zone(DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 dayswhere Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on eitherside of the line. About one millionnortherners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upperclasses consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communistpoliticians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone, thismass exodus was prompted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) andState of Vietnam in a massive propaganda campaign, as well as the peoples’fears of repression under a communist regime.

In August 1954, planes of the French Air Force and hundredsof ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy (the latter under Operation Passageto Freedom) carried out the movement of Vietnamese civilians from north tosouth. Some 100,000 southerners, mostlyViet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, moved to the northernzone. A peacekeeping force, called theInternational Control Commission and comprising contingents from India, Canada,and Poland,was tasked with enforcing the ceasefire agreement. Separate ceasefire agreements also weresigned for Laos and Cambodia.

Another agreement, titled the “Final Declaration of theGeneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring Peace in Indo-China, July 21,1954”, called for Vietnamese general elections to be held in July 1956, and thereunification of Vietnam. France DRV, the Soviet Union, China, and Britain signed thisDeclaration. Both the State of Vietnamand the United Statesdid not sign, the former outright rejecting the Declaration, and the lattertaking a hands-off stance, but promising not to oppose or jeopardize theDeclaration.

By the time of the Geneva Conference, the Viet Minhcontrolled a majority of Vietnam’sterritory and appeared ready to deal a final defeat on the demoralized Frenchforces. The Viet Minh’s agreeing toapparently less favorable terms (relative to its commanding battlefieldposition) was brought about by the following factors: First, despite Dien BienPhu, French forces in Indochina were far from being defeated, and still held anoverwhelming numerical and firepower advantage over the Viet Minh; Second, theSoviet Union and China cautioned the Viet Minh that a continuation of the warmight prompt an escalation of American military involvement in support of theFrench; and Third, French Prime Minister Pierre Mendes-France had vowed toachieve a ceasefire within thirty days or resign. The Soviet Union and China, fearing the collapse of the Mendes-Franceregime and its replacement by a right-wing government that would continue thewar, pressed Ho to tone down Viet Minh insistence of a unified Vietnamunder the DRV, and agree to a compromise.

The planned July 1956 reunification election failed tomaterialize because the parties could not agree on how it was to beimplemented. The Viet Minh proposedforming “local commissions” to administer the elections, while the United States,seconded by the State of Vietnam, wanted the elections to be held under UnitedNations (UN) oversight. The U.S.government’s greatest fear was a communist victory at the polls; U.S. PresidentEisenhower believed that “possibly 80%” of all Vietnamese would vote for Ho ifelections were held. The State ofVietnam also opposed holding the reunification elections, stating that as ithad not signed the Geneva Accords, it was not bound to participate in thereunification elections; it also declared that under the repressive conditionsin the north under communist DRV, free elections could not be held there. As a result, reunification elections were notheld, and Vietnamremained divided.

In the aftermath, both the DRV in the north (later commonlyknown as North Vietnam) and the State of Vietnam in the south (later as theRepublic of Vietnam, more commonly known as South Vietnam) became de factoseparate countries, both Cold War client states, with North Vietnam backed bythe Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, and South Vietnamsupported by the United States and other Western democracies.

In April 1956, Francepulled out its last troops from Vietnam;some two years earlier (June 1954), it had granted full independence to theState of Vietnam. The year 1955 saw thepolitical consolidation and firming of Cold War alliances for both North Vietnam and South Vietnam. In the north, Ho Chi Minh’s regime launchedrepressive land reform and rent reduction programs, where many tens ofthousands of landowners and property managers were executed, or imprisoned inlabor camps. With the Soviet Union and China sending more weapons and advisors, North Vietnamfirmly fell within the communist sphere of influence.

In South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, whom Bao Dai appointed asPrime Minister in June 1954, also eliminated all political dissent starting in1955, particularly the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen in Saigon, and thereligious sects Hoa Hao and Cao Dai in the Mekong Delta, all of whichmaintained powerful armed groups. InApril-May 1955, sections of central Saigonwere destroyed in street battles between government forces and the Binh Xuyenmilitia.

Then in October 1955, in a referendum held to determine theState of Vietnam’s political future, voters overwhelmingly supportedestablishing a republic as campaigned by Diem, and rejected the restoration ofthe monarchy as desired by Bao Dai. Widespread irregularities marred the referendum, with an implausible 98%of voters favoring Diem’s proposal. OnOctober 23, 1955, Diem proclaimed the Republicof Vietnam (later commonly known as South Vietnam),with himself as its first president. Itspredecessor, the State of Vietnam was dissolved, and Bao Dao fell from power.

In early 1956, Diem launched military offensives on the VietMinh and its supporters in the South Vietnamese countryside, leading tothousands being executed or imprisoned. Early on, militarily weak South Vietnamwas promised armed and financial support by the United States, which hoped to prop up the regime of PrimeMinister (later President) Diem, a devout Catholic and staunch anti-communist,as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia.

In January 1955, the first shipments of American weaponsarrived, followed shortly by U.S.military advisors, who were tasked to provide training to the South VietnameseArmy. The U.S. government also endeavored toshore up the public image of the somewhat unknown Diem as a viable alternativeto the immensely popular Ho Chi Minh. However, the Diem regime was tainted by corruption and nepotism, andDiem himself ruled with autocratic powers, and implemented policies thatfavored the wealthy landowning class and Catholics at the expense of the lowerpeasant classes and Buddhists (the latter comprised 70% of the population).

By 1957, because of southern discontent with Diem’spolicies, a communist-influenced civilian uprising had grown in South Vietnam,with many acts of terrorism, including bombings and assassinations, takingplace. Then in 1959, North Vietnam,frustrated at the failure of the reunification elections from taking place, andin response to the growing insurgency in the south, announced that it wasresuming the armed struggle (now against South Vietnam and the United States)in order to liberate the south and reunify Vietnam. The stage was set for the cataclysmic SecondIndochina War, more popularly known as the Vietnam War (next article).

October 10, 2024

October 10, 1945 – Chinese Civil War: The Nationalists and Communists sign the Double Tenth Agreement

On October 10, 1945, the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) and Communists (Chinese Communist Party) signed the Double Tenth Agreement (officially: “Summary of Conversations Between the Representatives of the Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China”) following 43 days of negotiations. The agreement was an attempt by both sides to prevent a resumption of full-scale fighting in the Chinese Civil War following the surrender of Japan in World War II on September 2, 1945. In the agreement, the communists recognized the Nationalists as the legitimate government, while the Nationalists acknowledged the Communists as the legitimate opposition party. The agreement brought together Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and Communist leader Mao Zedong, the latter accompanied by U.S. Ambassador to China Patrick Hurley, who also accompanied Mao to Chungking, where the negotiations took place.

The agreement was a failure as fighting between the two sides soon resumed.

(Taken from Chinese Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

China’s two major river systems, Yellow River and Yangtze River, served as strategic battle lines between communist and nationalist forces during the latter stages of the Chinese Civil War.

China’s two major river systems, Yellow River and Yangtze River, served as strategic battle lines between communist and nationalist forces during the latter stages of the Chinese Civil War.When the Japanese forces withdrew from China following their defeat inWorld War II, the civil war had shifted invariably in favor of theCommunists. The Red Army now constituted1.2 million soldiers and 2 million armed auxiliaries, with many more millionsof civilian volunteers ready to provide logistical support. Mao controlled one quarter of China’sterritories and one third of the population, all in areas that largely hadescaped the destruction of World War II.

By contrast, the Nationalist government had been weakenedseriously by World War II. The Nationalists’territories were devastated and were facing huge economic problems. Thousands of people were left homeless anddestitute.

Nearing the end of World War II, the Soviet Union launched amajor offensive against the Japanese forces in Manchuria, the industrialheartland where Japanmanufactured its weapons and military equipment. The Soviets subsequently withdrew from China but not before allowing the ChineseCommunists to occupy large sections of Manchuria(up to 97% of the total area) before the Nationalist Army arrived to take theremaining three Manchurian cities, which were geographically separated fromeach other.

After the Soviets and the Japanese had withdrawn from Chinaafter World War II, armed clashes began to break out between the Nationalistand Communist forces. It seemed only amatter of time before full-scale war would follow. In January 1946, the United States mediated a peaceagreement between the two sides. However, the Nationalists and Communists continued their arms build-upand war posturing, which eventually led to the breakdown of the truce in June1946 and the start of the final and decisive phase of the civil war.

In July 1946, Chiang launched a large-scale offensive with1.6 million soldiers, with the aim of destroying Mao’s forces in northern China. Because of their superior weapons, theNationalists advanced steadily. The RedArmy also pulled back as part of its strategy of luring on the Nationalists andthen letting them overextend their forward lines. In March 1947, the Nationalists capturedYan’an, the former Communists’ headquarters, which really was inconsequentialas Mao had moved the bulk of his forces further north.

By September 1948, the Red Army had become much bigger andstronger than the Nationalist forces. Maofinalized plans for a general counter-offensive that ultimately brought the warto an end. From their bases inManchuria, one million Red Army soldiers swept down over Nationalist-held Shenyang, Changchun, and Jinzhou, encircling thesecities and then capturing them. ByNovember 1948, the whole of Manchuria had comeunder the Communists’ control. Fivehundred thousand Nationalist soldiers had been killed, wounded, or captured.

The Red Army continued its offensive to the south and took Beijing and Tianjinfollowing heavy fighting. Afterincurring losses totaling some 200,000 soldiers, the remaining 260,000Nationalist defenders in Beijingsurrendered to the Communists. By lateJanuary 1949, the Communists held all of northern China.

A few weeks before the Beijingcampaign, another Red Army offensive consisting of 800,000 soldiers and 600,000auxiliaries descended on Xuzhou. By mid-January 1949, the Communists hadgained control of the Provinces of Shandong, Jiangsu,Anhui, and Henan– and all the territories north of the Yangtze River. More than five million peasants volunteeredas laborers for the Red Army, reflecting the Communists’ massive support in therural areas. Furthermore, many leadingNationalist Army officers had begun to defect to the Communists. The defectors handed the Red Army vitalmilitary information, seriously compromising the Nationalists’ war effort.

After the Nationalist Army’s crushing defeats in northernand central China,the war essentially was over. Chiang’sremaining forces were hard pressed to mount further effective resistanceagainst the Red Army’s offensives. Starting with their injudicious offensive in 1946, the Nationalists hadlost 1.5 million soldiers, including their best military units. Vast amounts of Nationalist stockpiles ofweapons and military hardware had fallen to the Red Army.

With ever-growing numbers of troops and weapons, Communistforces made their final advance south virtually unopposed toward the remainingNationalist territories in southern and southwestern China. At this time, the United States ended its militarysupport to the Nationalist government. Chiang moved China’snational art treasures and vast quantities of gold and foreign-currencyreserves from the National Treasury to the island of Taiwan,causing great uproar among high-ranking officials in his government.

After unsuccessful attempts to negotiate the surrender ofthe Nationalist government, the Red Army crossed the Yangtze River and capturedNanjing, the former capital of the Nationalists,who meanwhile had moved their headquarters to Guangdong Province.

A disagreement arose among Nationalist leaders whether todefend all remaining territories still under their control or to pull back to asmaller but more defensible area. ByOctober 1949, the Red Army had broken through Guangdong,but not before the Nationalists moved their capital to Chongqing.

On October 1, 1949, Mao declared the establishment of thePeople’s Republic of China. On December 10, 1949, as Red Army forces wereencircling Chengdu, the last Nationaliststronghold, Chiang departed on a plane for Taiwan. Joining him in Taiwan were about two millionChinese mainlanders, mostly Kuomintang officials, Nationalist Army officers andsoldiers, prominent members of society, the academe, and the religiousorders. On March 1, 1950, Chiang resumedhis position as China’spresident and declared Taiwanas the temporary capital of the Republic of China.

In the months that followed, fighting continued to flare upbetween the military forces of the two Chinese governments, mainly forpossession of the islands along the waters separating their countries. Since no truce or peace agreement was made byand between the two governments that do not recognize the legitimacy of theother, to this day, the two countries are technically still at war.

October 9, 2024

October 9, 1970 – Cambodian Civil War: The Khmer Republic is proclaimed

On October 9, 1970, the Khmer Republic was proclaimed in Cambodia with General Lon Nol appointed as the country’s head of state. Earlier in March 1970, Lon Nol had led a coup by the National Assembly that voted to oust the reigning head of state, Prince Norodom Sihanouk. The formation of the republic also ended the Kingdom of Cambodia. Lon Nol’s right-wing government was backed by the United States, and sided with South Vietnam against North Vietnam in the ongoing Vietnam War. Lon Nol also reversed Sihanouk’s tolerant policy of allowing North Vietnam to occupy large sections of Cambodian territory in its war against South Vietnam. As such, he demanded that North Vietnamese troops leave the country, and greatly increased the size of his armed forces with large financial support from the United States.

The emergence of the Khmer Republic greatly alarmed North Vietnam, leading to increased North Vietnamese and Viet Cong (South Vietnamese rebels of the National Liberation Front) activity in Cambodian-occupied areas, as well as bolstering support for the Cambodian communist guerrilla group, the Khmer Rouge.

(Taken from Cambodian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background Between 1970 and 1975, the U.S.-backed government in Cambodia fought a civil war against the Khmer Rouge, a Cambodian insurgent movement that wanted to establish a communist regime in the country. The Khmer Rouge’s victory in the war marked the rise into power of its leader, Pol Pot, who would engineer one of the bloodiest genocides in history. The civil war formed a part of the complex geopolitical theaters of tumultuous Indo-China during the first half of the 1970s, more particularly in reference to the Vietnam War which greatly affected the security climates of adjacent countries, including Cambodia (Map 1).

In 1970, serious economic problems in Cambodia prompted the military to overthrowPrince Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia’sruling monarch, whose faulty policies led to widespread discontent among thepeople. Prince Sihanouk, althoughextremely popular and revered as a semi-deity by Cambodians, applied acalculating but dangerous foreign policy of playing up the superpowers in orderto get the best deal for Cambodia,and still maintain neutrality.

Years earlier, Prince Sihanouk willingly had receivedmilitary and financial assistance from the United States. But in 1965, after deciding that communismultimately would prevail in Indo-China, he opened diplomatic relations with China and North Vietnam. Furthermore, he accepted military andeconomic support from North Vietnam. In return, he allowed the North Vietnamese Army to use sections ofeastern Cambodia in its waragainst South Vietnam.