Daniel Orr's Blog, page 10

September 28, 2024

September 28, 1939 – World War II: Germany and the Soviet Union partition Poland

On September 28, 1939, as their joint invasion of Poland was winding down, Germany and the Soviet Union, acting on Stalin’s proposal, agreed to make changes totheir respective spheres of influence as set forth in the Molotov-Ribbentroppact. In the revised treaty, Germany relinquished to the Soviet Union itsclaim to a sphere of influence on Lithuaniain exchange for the Soviet Union relinquishing to Germanyits sphere of influence to sections of central Poland,including Warsaw and Lublin. On October 8, 1939, Germanyannexed western Poland,including Danzig, the Polish Corridor, and Silesia,and established the German-run General Governorate in the rest of the German-assignedterritory in Poland.

The Soviet Union also annexed its share of Polishterritories, partitioning them among its subordinate states Belarus, Ukraineand Lithuania,and implementing Sovietization policies in ethnic Polish-majority regions.

In German-controlled Poland, which was extended to includeall of Poland after German forces captured the Soviet section of Poland in theearly stages of Operation Barbarossa (the German invasion of the Soviet Union)in June 1941, Nazi Germany implemented policies aimed at achieving Lebensraum,where ethnic Germans would settle in the former Polish territories which thenwould be completely Germanized politically, economically, socially, andculturally. As Lebensraum entailed displacingthe native populations, Generalplan Ost (General Plan East) was initiated in aseries of programs of depopulating, resettling, or otherwise eliminating thePolish population from lands that were destined to become fully German. Central to Nazi doctrine was the concept ofGerman racial superiority, and that German ethnic purity was to be maintainedand not tainted by the blood of races which the Nazis classified as inferior(Untermensch, or sub-human), which included Poles and other Slavic peoples,Jews, and Roma (gypsies), among others.

The colonization and full Germanization of Polishterritories were to be accomplished in stages over many years. But of more urgency to the Germans was thefate of Polish Jews, whose eradication was determined in January 1942 throughthe euphemistically called “Final Solution”. In the aftermath of the Polish campaign, German authorities segregatedthe three million Polish Jews, who were then forced into the hundreds of Jewishghettos quickly set up across Poland. In the ensuing period, Polish and other Jewsacross Europe were transported by train tospecially constructed labor, concentration, and extermination camps where themass executions ultimately were carried out. Aside from Jews, Slavs, and Roma, Nazi extermination policies alsotargeted the physically and mentally disabled, homosexuals, politicalopponents, communists, prisoners of war, resistance fighters, and other groups.

In Poland, as a result of the German occupation, some six million Poles perished, or 20% of the total population. Of this number, three million were Jews, of whom 90% were killed. (Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

September 27, 2024

September 27, 1940 – World War II: Germany, Italy, and Japan sign the Tripartite Pact

On September 27, 1940, Germany, Italy, and Japan signed the Tripartite Pact, a mutual assistance treaty where the signatories pledged to come to the aid “if one of the Contracting Powers is attacked by a Power at present not involved in the European War or in the Japanese-Chinese conflict.” At this time, Europe was already embroiled in World War II while in Asia, the Second-Japanese War was being fought. The Pact was directed at the United States, which was then the only neutral major power, to deter its being involved in the conflicts on the Allied side. The Pact also acknowledged the pre-eminence of Germany and Italy in Europe, and Japan in “Greater East Asia”. It was to be effective for ten years, with a provision for its renewal.

The Tripartite Pact was later joined by other countries: Hungary on November 20, 1940, Romania on November 23, 1940, Slovakia on November 24, 1940, Bulgaria on March 1, 1941, and Yugoslavia on March 25, 1941. The Axis invaded and then partitioned Yugoslavia; subsequently, the newly formed Independent State of Croatia joined the Pact on June 15, 1941.

The Soviet Union also entered into negotiations with Germanyto join the Tripartite Pact, even offering the latter substantial economicconcessions. However, Hitler was determined that the Soviet Union would not be allowed to join, as preparations were alreadyunderway for Operation Barbarossa.

In June 1941, after the start of the German-led invasion of the Soviet Union, Germany asked Finland, which had also participated in the attack, to join the Tripartite Pact. However, the Finnish government rebuffed the offer, as its military objectives differed from the Germans. Finland also wanted to maintain diplomatic relations with the United States and the Western Allies.

Japan attackedThailand on December 8, 1941as a means to gain passage to invasion British Malaya and Burma. After a ceasefire wassigned, Japan invited Thailandto join the Tripartite Pact, but the latter only agreed on military cooperationwith the Japanese.

(Taken from Italy before World War II – Wars of the 20th Century- World War II in Europe)

In World War I, Italy had joined the Allies under a secret agreement (the 1915 Treaty of London) in that it would be rewarded with the coastal regions of Austria-Hungary after victory was achieved. But after the war, in the peace treaties with Austria-Hungary and Germany, the victorious Allies reneged on this treaty, and Italy was awarded much less territory than promised. Indignation swept across Italy, and the feeling of the so-called “mutilated victory” relating to Italy’s heavy losses in the war (1.2 million casualties and steep financial cost) led to the rise in popularity of ultra-nationalist, right-wing, and irredentist ideas. Italian anger over the war paved the way for the coming to power of the Fascist Party, whose leader Benito Mussolini became Prime Minister in October 1922. The Fascist government implemented major infrastructure and social programs that made Mussolini extremely popular. In a few years, Mussolini ruled with near absolute powers in a virtual dictatorship, with the legislature abolished, political dissent suppressed, and his party the sole legal political party. Mussolini also made gains in foreign affairs: in the Treaty of Lausanne (July 1923) that ended World War II between the Allies and Ottoman Empire, Italy gained Libya and the Dodecanese Islands. In August 1923, Italian forces occupied Greece’s Corfu Island, but later withdrew after League of Nations mediation and the Greek government’s promise to pay reparations.

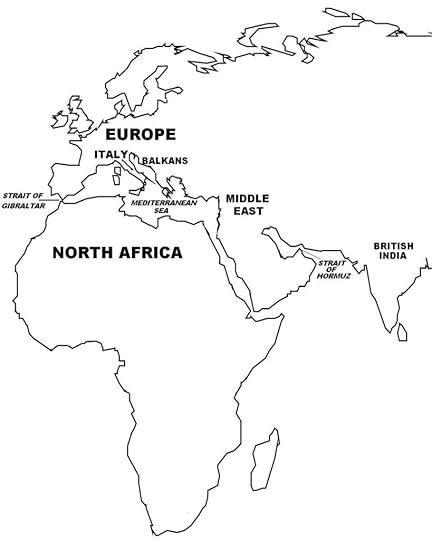

In the late 1920s onward, Mussolini advocated grandioseexpansionism to establish a modern-day Italian Empire, which would includeplans to annex Balkan territories that had formed part of the ancient RomanEmpire, gaining a sphere of influence in parts of Central and Eastern Europe,achieving mastery over the Mediterranean Sea, and gaining control of North Africaand the Middle East which would include territories stretching from theAtlantic Ocean in the west to the Indian Ocean in the east.

With the Nazis coming to power in Germanyin 1933, Hitler and Mussolini, with similar political ideologies, initially didnot get along well, and in July 1934, they came into conflict over Austria. There, Austrian Nazis attempted a coupd’état, assassinating Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss and demanding unificationwith Germany. Mussolini, who saw Austriaas falling inside his sphere of influence, sent troops, tanks, and planes tothe Austrian-Italian border, poised to enter Austriaif Germanyinvaded. Hitler, at this time stillunprepared for war, backed down from his plan to annex Austria. Then in April 1935, Italy banded togetherwith Britain and France to form the Stresa Front (signed in Stresa, Italy),aimed as a united stand against Germany’s violations of the Versailles andLocarno treaties; one month earlier (March 1935), Hitler had announced his planto build an air force, raise German infantry strength to 550,000 troops, andintroduce military conscription, all violations of the Versailles treaty.

However, the Stresa Front quickly ended in fiasco, as thethree parties were far apart in their plans to deal with Hitler. Mussolini pressed for aggressive action; theBritish, swayed by anti-war public sentiments at home, preferred to negotiatewith Hitler; and France,fearful of a resurgent Germany,simply wanted an alliance with the others. Then in June 1935, just two months after the Stresa Front was formed,Britain and Germany signed a naval treaty (the Anglo-German Naval Agreement),which allowed Germany to build a navy 35% (by tonnage) the size of the Britishnavy. Italy(as well as France) wasoutraged, as Britain wasopenly allowing Hitler to ignore the Versaillesprovision that restricted German naval size. Mussolini, whose quest for colonial expansion was only restrained by thereactions from both the British and French, saw the naval agreement as Britishbetrayal to the Stresa Front. ToMussolini, it was a green light for him to launch his long desired conquest of Ethiopia (then also known as Abyssinia). In October 1935, Italyinvaded Ethiopia,overrunning the country by May 1936 and incorporating it into newly formed Italian East Africa. In November 1935, the League of Nations, acting on a motion by Britain that was reluctantly supported by France, imposed economic sanctions on Italy, which angered Mussolini, worsening Italy’s relations with its Stresa Frontpartners, especially Britain. At the same time, since Hitler gave hissupport to Italy’s invasionof Ethiopia, Mussolini wasdrawn to the side of Germany. In December 1937, Mussolini ended Italy’s membership in the League of Nations, citing the sanctions, despite the League’s alreadylifting the sanctions in July 1936.

In January 1936, Mussolini informed the German governmentthat he would not oppose Germanyextending its sphere of influence in Austria (Germany annexed Austria inMarch 1938). And in February 1936,Mussolini assured Hitler that Italywould not invoke the Versailles and Locarno treaties if Germanyremilitarized the Rhineland. In March 1936, Hitler did just that,eliciting no hostile response from Britainor France. Then in the Spanish Civil War, which startedin July 1936, Italy and Germanyprovided weapons and troops to the right-wing Nationalist forces that rebelledagainst the Soviet Union-backed leftist Republican government. In April 1939, the Nationalists emergedvictorious, and their leader General Francisco Franco formed a fascistdictatorship in Spain.

In October 1936, Italyand Germany signed apolitical agreement, and Mussolini announced that “all other European countrieswould from then on rotate on the Rome-Berlin Axis”, with the term “Axis” laterdenoting this alliance, which included Japan as well as other minorpowers. In May 1939, German-Italianrelations solidified into a formal military alliance, the “Pact of Steel”. In November 1937, Italyjoined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which Germanyand Japan signed one yearearlier (November 1936), ostensibly only directed against the CommunistInternational (Comintern), but really targeting communist ideology and byextension, the Soviet Union. In September 1940, the Axis Powers wereformed, with Germany, Italy, and Japan signing the Tripartite Pact.

In April 1939, Italyinvaded Albania (separatearticle), gaining full control within a few days, and the country was joinedpolitically with Italyas a separate kingdom in personal union with the Italian crown. Six months later (September 1939), World WarII broke out in Europe, which took Italy completely by surprise.

Despite its status as a major military power, Italywas unprepared for war. It had apredominantly agricultural economy, and industrial production forwar-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for war-importantitems such as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind those ofother western powers. In militarycapability, Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostlyobsolete, although the Italian Navy was large, ably powerful, and possessedseveral modern battleships. Cognizant ofItalian military deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts to build up armedstrength, and by 1939, some 40% of the national budget was allocated tonational defense. Even so, Italianmilitary planners had projected that full re-armament and building up of theirforces would be completed only in 1943; thus, the unexpected start of World WarII in September 1939 came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

September 26, 2024

September 26, 1950 – Korean War: UN forces recapture Seoul

United Nations (UN) forces at Inchon soon recaptured Kimpo airfield. There, U.S.planes began to conduct air strikes on North Korean positions in and around Seoul. UN ground forces then launched athree-pronged attack on the capital. They met heavy North Korean resistance at the perimeter but sooncaptured the heights overlooking the city. On September 25, 1950, UN forces entered Seoul, and soon declared the city liberated. Even then, house-to-house fighting continueduntil September 27, when the city was brought under full UN control. On September 29, 1950, UN forces formallyturned over the capital to President Syngman Rhee, who reestablished hisgovernment there. And by the end ofSeptember 1950, with remnants of the decimated North Korean Army retreating indisarray across the 38th parallel, South Korean and UN units gained control ofall pre-war South Korean territory.

Some key areas during the Korean War

Some key areas during the Korean WarOn October 1, 1950, the South Korean Army crossed the 38thparallel into North Korea along the eastern and central regions; UN forces,however, waited for orders. Four daysearlier, on September 27, 1950, President Truman sent a top-secret directive toGeneral MacArthur advising him that UN forces could cross the 38th parallelonly if the Soviet Union or China had not sent or did not intend to send forcesto North Korea.

Earlier, the Chinese government had stated that UN forcescrossing the 38th parallel would place China’s national security at risk,and thus it would be forced to intervene in the war. Chairman Mao Zedong also stated that if U.S. forces invaded North Korea, Chinamust be ready for war with the United States.

At this stage of the Cold War, the United States believed that its biggest threatcame from the Soviet Union, and that the Korean War may very well be a Sovietplot to spark an armed conflict between the United States and China. This would force the U.S. military to divert troops and resources toAsia, and leave Western Europe open to aSoviet invasion. But after muchdeliberation, the Truman administration concluded that China was “bluffing” and would not reallyintervene in Korea,and that its threats merely were intended to undermine the UN. Furthermore, General MacArthur also later(after UN forces had crossed the 38th parallel) expressed full confidence inthe UN (i.e. U.S.)forces’ military superiority – that Chinese forces would face the “greatestslaughter” if they entered the war.

On October 7, 1950, the UNGA adopted Resolution 376 (V)which declared support for the restoration of stability in the Korean Peninsula,a tacit approval for the UN forces to take action in North Korea. Two days later, October 9, UN forces, led bythe Eighth U.S. Army, crossed the 38th parallel in the west, with GeneralMacArthur some days earlier demanding the unconditional surrender of the NorthKorean Army. UN forces met only lightresistance during their advance north. On October 15, 1950, Namchonjam fell, followed two days later byHwangju.

In North Korea’s eastern coast, the U.S. X Corps madeunopposed amphibious landings at Wonsan on October 25, 1950 (with South Koreanforces having taken this port town days earlier) and at Iwon, further north, onOctober 29. On October 24, 1950, underthe “Thanksgiving Offensive” issued by General MacArthur who wanted the warended before the start of winter, UN forces made a rapid advance to the Yalu River,which serves as the China-North Korea border.

In late October 1950, UN forces clashed with the ChineseArmy, and a new phase of the war began. Earlier, in June 1950 in Beijing,Chairman Mao had declared his intention to intervene in the Korean conflict,which received strong reluctance from Chinese military leaders. But with the support of Premier Zhou Enlai,and General Peng Dehuai, (military commander of China’s northwest region, whowould be appointed to lead the Chinese forces in the Korean War), the plan forthe Chinese Army (officially called the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA) tobecome involved in Korea was approved.

On October 8, 1950, the day that UN forces crossed the 38thparallel into North Korea,Chinese forces in Manchuria (the North East Frontier Force, or NEFF) wereordered to deploy at the Yalu River in preparation to enter North Koreafrom the north. On October 19, 1950, theday Pyongyang fell, on Chairman Mao’s order, theNEFF crossed into North Korea. Chinese authorities called this force the “People’s Volunteer Army”, the“volunteer” designation conferring on it a non-official status in order that China would notbe directly involved in a war with the US/UN.

The Chinese deployment from Manchuria to Korea wascarried out under strict secrecy, and Chinese troops travelled only at nightand remained camouflaged during the day. So successful were the Chinese in using secrecy and concealment that U.S. surveillance planes, even with their fullcontrol of the skies, were unable to detect the massive Chinese buildup at the Yalu River. Chinese forces soon entered North Korea.

On October 25, 1950, using surprise and overwhelmingnumerical force, the Chinese struck at the UN forces (led by the Eighth U.S.Army), which was moving up the western region toward the Yalu River. The Chinese particularly targeted the UNright flank along the Taebaek Mountains, whichconsisted of South Korean forces. In theensuing four-day encounter at Onjong (Battle of Onjong), the Chinese severelycrippled the South Korean forces and punched a hole in the UN lines. Thousands of Chinese soldiers then poured throughthe gap and advanced behind UN lines. OnNovember 1, 1950 at Unsan, the Chinese attacked along three points at the UNline at its center, inflicting heavy casualties on the American and SouthKorean forces. At this point, the U.S. high command ordered the Eighth U.S. Armyto retreat south of the Chongchon River.

On November 6, 1950, the Chinese forces also broke contactand withdrew north to the mountains. Unknown to UN forces, the Chinese had over-extended their supply lines,which would be a problem that Chinese forces would face constantly during thewar. Furthermore, in this early stage oftheir involvement in the war, the Chinese relied on weapons supplied by the Soviet Union. Later on, the Chinese would also manufacture their own armaments, andreduce their reliance on foreign imports.

The fighting in the north also saw the first air battlesbetween American and Soviet jet planes, leading to many intense dogfightsduring the war. Early on, the newlyreleased, powerful Soviet MiG-15 easily outclassed the U.S.first-generation jet planes, the P-80 Shooting Star and the F9F Panther, andposed a serious threat to the U.S. B-29 bombers. But with the arrival of the U.S. F-86 Sabre,parity was achieved in the sky in terms of jet fighter aircraft capability onboth sides. Ultimately, U.S. planeswould continue to hold nearly full control of the sky for the duration of thewar.

The sudden Chinese withdrawal during the Battle of Onjongperplexed the U.S.military high command. Weeks earlier,General MacArthur stated his belief that Chinahad some 100,000-125,000 troops north of the YaluRiver, and that if half of this numberwas sent to Korea,his forces easily could meet this threat. In the ensuing lull (November 6–24, 1950), U.S. surveillance planes detectedno significant Chinese military buildup, and sightings of enemy troop strengthon the ground seemed to confirm General MacArthur’s estimates. Convinced that China was not intending tofully intervene in Korea, General Macarthur launched the “Home-by-Christmas”Offensive, a cautious two-sector advance toward the Yalu River: UN forces inthe western sector led by the Eighth U.S. Army as the main attacking force, andin the eastern sector led by the U.S. X Corps to support the attack and alsocut off enemy supply and communication lines.

September 25, 2024

September 25, 1964 – The start of Mozambique’s War of Independence against Portugal

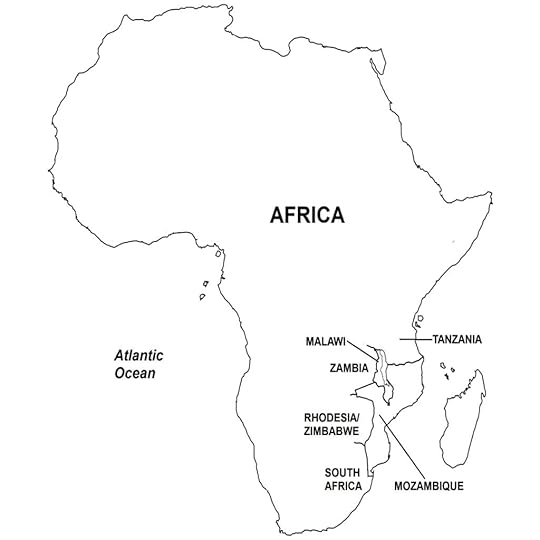

In September 1964, the nationalist organization FRELIMOlaunched small guerilla attacks from bases in Tanzaniainto Cabo DelgadoProvince, located in northern Mozambique. FRELIMO, or the Mozambique Liberation Front (Portuguese:Frente de Libertação de Moçambique)was formed in June 1962 from the merger of three ethnic-based independencemovements.

Initially, because of limited combat strength, FRELIMOplanned to undertake a prolonged guerilla war instead of launching one powerfulattack on Lourenço Marques, Mozambique’scapital, in the hope of quickly ousting the colonial government, as proposed byother rebel leaders. Initially, FRELIMOwas handicapped by a shortage of recruits, weapons, and combat capability, andas a result, rebel operations did not seriously disrupt the government’s capacityto operate normally.

(Taken from Mozambican War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background During the 17th and 18th centuries, Mozambique, then known officially as the State of East Africa, served little more than as a transit stop for Portuguese and other European ships bound for Asia, as Portugal was focused on supporting its lucrative trade with India and China, and more important, developing Brazil, its prized possession in the New World.

In 1822, however, Brazilgained its independence, and with other European powers actively seeking theirshare of Africa during the last quarter of the 1800s, Portugal nowlooked to hold onto and protect its African colonies. Through an Anglo-Portuguese treaty signed in1891, Mozambique’s borderswere delineated, and by the early twentieth century, Portugal had established fulladministrative control over its East African colony.

Some thirty years earlier, in 1878, in order to developMozambique’s largely untapped northern frontier region, the Portuguesegovernment leased out large tracts of territories to chartered corporations(mostly British), which greatly expanded the colony’s mining and agriculturalindustries, as well as build these industries’ associated infrastructures, suchas roads, bridges, railways, and communication lines. Black Africans were used as manpower, andutilized under a repressive forced labor system – slavery had officially beenoutlawed in 1842, although clandestine slave trading continued until the earlytwentieth century. When the charteredcorporations’ leases expired in 1932, the Portuguese government did not renewthe contracts, and thenceforth began direct rule of Mozambiquefrom Lisbon, Portugal’s national capital.

After World War II ended in 1945, nationalist aspirationssprung up and spread rapidly across Africa. By the 1960s, most of the continent’scolonies had become independent countries. Portugal,however, was determined to maintain its empire. In 1951, Portugalceased to regard its African (and Asian) possessions as “colonies”, butintegrated them into the motherland as “overseas provinces”. Tens of thousands of Portuguese citizensmigrated to Mozambique, aswell as to Angolaand Portuguese Guinea under the prodding of the national government to lead thedevelopment of the new “provinces”.

Because of the immigration, racial tensions, which alreadywere prevalent, escalated in Portugal’sAfrican territories. Portugal tookgreat pride in its official policy of racial inclusiveness, and upheld in itsconstitution the “democratic, social, and multi-racial” features of Portuguesesociety. However, the PortugueseOverseas Charter also recognized distinct socio-ethnic classes: citizens –European Portuguese who had full political rights; “assimilados” – blackAfricans who had assimilated the Portuguese way of life, could read and write,and were eligible to run for local and provincial elected office; and natives –the great majority of black Africans who retained their traditional ways oflife.

The Portuguese monopolized the political and economicsystems of the colony, while the general population had limited access toeducation and upward social and economic mobility. By the early 1960s, less than 1% of blackAfricans had attained “assimilado” status. The colonial government repressed political dissent, forcing manyMozambican nationalists into exile abroad, and used PIDE (Policia Internacionale de Defesa do Estado), Portugal’ssecurity service, to turn Mozambiqueinto a police state.

In June 1962, exiled Mozambican nationalists met in Dar esSalaam, Tanganyika, and merged three ethnic-based independence movements intoone nationalist organization, FRELIMO or Mozambique Liberation Front(Portuguese: Frente de Libertação de Moçambique). Led by Eduardo Mondlane, FRELIMO initiallysought to gain Mozambique’sindependence by negotiating with the Portuguese government. FRELIMO regarded the Portuguese as foreignerswho were exploiting Mozambique’shuman and natural resources, and were unconcerned with the development andwell-being of the indigenous black population.

By 1964, Portugal’sintransigence and the Mozambican colonial government’s repressive acts,including the so-called Mueda Massacre, where security forces opened fire on acrowd of demonstrators, had radicalized FRELIMO into believing that Mozambique’sindependence could only be gained through armed struggle. Further motivating FRELIMO into starting arevolution was that Mozambique’sneighbors recently had achieved their independences, i.e. Tanzania in 1961, and Malawiand Zambia in 1964, andthese countries’ black-ruled governments would be expected to support Mozambique’sstruggle for independence as well.

September 24, 2024

September 24, 1973 – Guinea-Bissau declares independence from Portugal

On September 24, 1973, Guinea-Bissau declared its independence in the town of Madina do Boe during its ongoing revolution against Portugal (Guinea-Bissau War of Independence) that had begun in January 1963. The infant state was immediately recognized by many African and communist countries.

Guinea’s independence struggle was led by the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde or PAIGC (Portuguese: Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde), established in 1956 with the aim of ending Portuguese colonial rule and gaining independence for Guinea and Cape Verde. Initially, the PAIGC wanted to achieve its aims through dialogue and a negotiated settlement. By the late 1950s, however, the Guinean nationalists had become more militant.

The Guinea-Bissau War of Independence forms part of thePortuguese Colonial War.

(Taken from Portuguese Colonial Wars – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

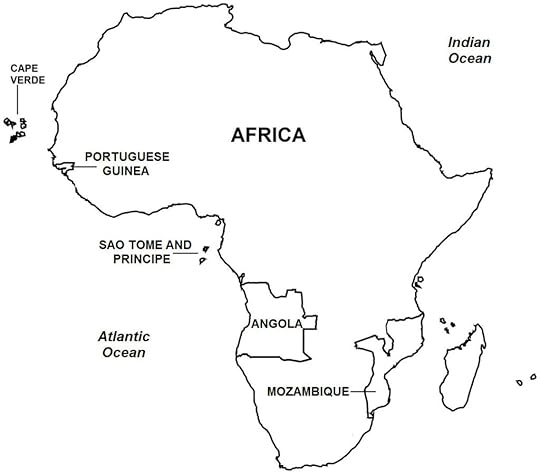

Portugal’s African colonial possessions consisted of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese-Guinea, Cape Verde, and Sao Tome & Principe.

Portugal’s African colonial possessions consisted of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese-Guinea, Cape Verde, and Sao Tome & Principe.During the colonial era, Portugal’s territorial possessions in Africa consisted of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe (Map 24). When World War II ended in 1945, a surge of nationalism swept across the various African colonies as independence groups emerged and demanded the end of European colonial rule. As these demands soon intensified into greater agitation and violence, most of the European colonizers relented, and by the 1960s, most of the African colonies had become independent countries.

Bucking the trend, Portugal was determined to holdonto its colonial possessions and went so far as to declare them “overseasprovinces”, thereby formally incorporating them into the national territoriesof the motherland. Nearly all the blackAfrican liberation movements in these Portuguese “provinces” turned theirattention from trying to gain independence through negotiated settlement tolaunching insurgencies, thereby starting revolutionary wars. These wars took place through the early 1960sto the first half of the 1970s, and were known collectively as the PortugueseColonial War, and pitted the Portuguese Armed Forces against the Africanguerilla militias in Angola,Mozambique,and Portuguese Guinea. At the war’speak, some 150,000 Portuguese soldiers were deployed in Africa.

By the 1970s, these colonial wars had become extremelyunpopular in Portugal,because of the mounting deaths in Portuguese soldiers, the irresolvable natureof the wars through military force, and the fact that the Portuguese governmentwas using up to 40% of the national budget to the wars and thus impinging onthe social and economic development of Portuguese society. Furthermore, the wars had isolated Portugal diplomatically, with the United Nationsconstantly putting pressure on the Portuguese government to decolonize, andmost of the international community imposing a weapons embargo and otherrestrictions on Portugal. In April 1974, dissatisfied officers of themilitary carried out a coup that deposed the authoritarian regime of PrimeMinister Marcelo Caetano. The coup,known as the Carnation Revolution, produced a sudden and dramatic shift in thecourse of the colonial wars.

September 23, 2024

September 23, 1943 – World War II: Mussolini establishes the Italian Social Republic

On September 23, 1943, Benito Mussolini founded the Italian Social Republic (Italian: Repubblica Sociale Italiana, RSI), a fascist state centered on the small town of Salo in northern Italy (hence its more commonly known name, “Republic of Salo”). RSI claimed sovereignty over most Italy, but de facto exercised authority only in the northern region, since by this time, the Allies had captured territory in southern Italy and were fighting their way north, and the defending German forces controlled the non-liberated regions. RSI had an armed force of about 150,000 troops but was totally dependent on Germany. It had been set up just after Mussolini was freed by German commandos on September 12, 1943. Mussolini had been sacked as Prime Minister and imprisoned in July 1943 after the Allies captured Sicily. The new Italian government opened secret peace talks with the Allies, leading to the Armistice of Cassibile, where Italy surrendered to the Allies. Fearing German reprisal, King Victor Emmanuel II and the new government fled to Allied-controlled southern Italy, where they set up their headquarters. In October 13, 1943, Italy declared war on Germany. But as a consequence of the armistice, German forces took over power in Italy.

The RSI existed until May 1, 1945 when German forces in Italy surrendered. Mussolini and other RSI leaders were captured by Italian partisans four days earlier, on April 27, and executed the following day.

(Taken from Mussolini and his Quest for an Italian Empire – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In the midst of political and social unrest in October 1922, Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party came to power in Italy, with Mussolini being appointed as Prime Minister by Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III. Mussolini, who was popularly called “Il Duce” (“The Leader”), launched major infrastructure and social programs that made him extremely popular among his people. By 1925-1927, the Fascist Party was the only legal political party, the Italian legislature had been abolished, and Mussolini wielded nearly absolute power, with his government a virtual dictatorship.

By the late 1920s through the 1930s, Mussolini pursued anovertly expansionist foreign policy. Hestressed the need for Italian domination of the Mediterranean region andterritorial acquisitions, including direct control of the Balkan states of Yugoslavia, Greece,Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania,and a sphere of influence in Austriaand Hungary, and colonies inNorth Africa. Mussolini envisioned a modern Italian Empire in the likeness of theancient Roman Empire. He explained that his empire would stretchfrom the “Strait of Gibraltar [western tip of the Mediterranean Sea] tothe Strait of Hormuz [in modern-day Iranand the Arabian Peninsula]”. Although not openly stated, to achieve thisgoal, Italy would need toovercome British and French naval domination of the Mediterranean Sea.

Furthermore, in the aftermath of World War I, a strongsentiment regarding the so-called “mutilated victory” pervaded among manyItalians about what they believed was their country’s unacceptably smallterritorial gains in the war, a sentiment that was exploited by the Fascistgovernment. Mussolini saw his empire asfulfilling the Italian aspiration for “spazio vitale” (“vital space”), wherethe acquired territories would be settled by Italian colonists to ease theoverpopulation in the homeland. Mussolini’s government actively promoted programs that encouraged largefamily sizes and higher birth rates.

Mussolini also spoke disparagingly about Italy’sgeographical location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about how it was“imprisoned” by islands and territories controlled by other foreign powers(i.e. France and Britain), and that his new empire would include territoriesthat would allow Italy direct access to the Atlantic Ocean in the west and theIndian Ocean in the east.

In October 1935, the Italian Army invaded independent Ethiopia,conquering the African nation by May 1936 in a brutal campaign that includedthe Italians using poison gas on civilians and soldiers alike. Italythen annexed Ethiopia intothe newly formed Italian East Africa, which included Eritreaand Italian Somaliland. Italyalso controlled Libya in North Africa as a colony.

The aftermath of Italy’sconquest of Ethiopia saw arapprochement in Italian-Nazi German relations arising from Hitler’s support ofItaly’s invasion of Ethiopia. In turn, Mussolini dropped his opposition to Germany’s annexation of Austria. Throughout the 1920s-1930s, the majorEuropean powers Britain, France, Italy, the Soviet Union and Germany, engagedin a power struggle and formed various alliances and counter-alliances amongthemselves, with each power hoping to gain some advantage in what was seen asan inevitable war. In this powerstruggle, Italystraddled the middle and believed that in a future conflict, its weight wouldtip the scales for victory in its chosen side.

In the end, it was Italy’sties with Germanythat prospered; both countries also shared a common political ideology. In the Spanish Civil War (July 1936-April1939), Italy and Germany supported the rebel Nationalist forcesof General Francisco Franco, who emerged victorious and took over power in Spain. In October 1936, Italyand Germanyformed an alliance called the Rome-Berlin Axis. Then in 1937, Italyjoined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had been signed by Germany and Japan in November 1936. In April 1939, Italymoved one step closer to forming an empire by invading Albania, seizing control of theBalkan nation within a few days. In May1939, Mussolini and Hitler formed a military alliance, the Pact of Steel. Two months earlier (March 1939), Germany completed the dissolution and partial annexationof Czechoslovakia. The alliance between Germany and Italy,together with Japan,reached its height in September 1940, with the signing of the Tripartite Pact,and these countries came to be known as the Axis Powers.

On September 1, 1939 World War II broke out when Germany attacked Poland,which immediately embroiled the major Western powers, France and Britain,and by September 16 the Soviet Union as well (as a result of a non-aggressionpact with Germany, but notas an enemy of France and Britain). Italydid not enter the war as yet, since despite Mussolini’s frequent blustering ofhaving military strength capable of taking on the other great powers, Italyin fact was unprepared for a major European war.

Italy wasstill mainly an agricultural society, and industrial production forwar-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for vital itemssuch as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind the otherwestern powers. In military capability,Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostly obsolete by thestart of World War II, although the large Italian Navy was ably powerful andpossessed several modern battleships. Cognizant of these deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts tobuilding up Italian military strength, and by 1939, some 40% of the nationalbudget was allocated to the armed forces. Even so, Italian military planners had projected that its forces wouldnot be fully prepared for war until 1943, and therefore the sudden start ofWorld War II came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

In April-June 1940, Germanyachieved a succession of overwhelming conquests of Denmark,Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium,Luxembourg, and France. As Franceverged on defeat and with Britainisolated and facing possible invasion, Mussolini decided that the war wasover. In an unabashed display ofopportunism, on June 10, 1940, he declared war on Franceand Britain, bringing Italy into World War II on the side of Germany,and stating, “I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peaceconference as a man who has fought”.

September 22, 2024

September 22, 1980 – Iraq launches invasion of Iran

An escalation of hostilities, including artillery exchanges and air attacks, took place in the period preceding the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War. On September 22, 1980, Iraq opened a full-scale offensive into Iran with its air force launching strikes on ten key Iranian airbases, a move aimed at duplicating Israel’s devastating and decisive air attacks at the start of the Six-Day War in 1967. However, the Iraqi air attacks failed to destroy the Iranian air force on the ground as intended, as Iranian planes were protected by reinforced hangars. In response, Iranian planes took to the air and carried out retaliatory attacks on Iraq’s vital military and public infrastructures.

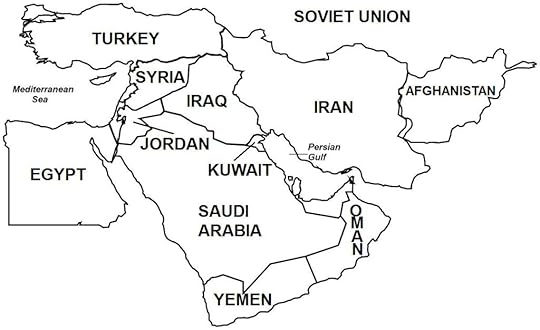

Iran, Iraq, and adjacent countries.

Iran, Iraq, and adjacent countries.Throughout the war, the two sides launched many air attackson the other’s economic infrastructures, in particular oil refineries anddepots, as well as oil transport facilities and systems, in an attempt todestroy the other side’s economic capacity. Both Iran and Iraq weretotally dependent on their oil industries, which constituted their main sourceof revenues. The oil infrastructureswere nearly totally destroyed by the end of the war, leading to the nearcollapse of both countries’ economies. Iraq was much more vulnerable, because of itslimited outlet to the sea via the Persian Gulf,which served as its only maritime oil export route.

(Taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In January 1979, anti-royalist elements (Islamists, nationalists, liberals, communists, etc.) in Iran forced the reigning Shah (king) Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to leave for exile abroad, and this event, known as the Iranian Revolution, effectively ended Iran’s monarchy. The following month, February 1979, Ayatollah (Shiite Muslim religious leader) Ruhollah Khomeini, the inspirational and spiritual leader of the revolution, returned from exile in France and set up a provisional government led by Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan. After a brief period of armed resistance put up by royalist supporters, the revolution prevailed and Ayatollah Khomeini consolidated political power.

Then in a national referendum held in March 1979, Iraniansoverwhelmingly voted to abolish the monarchy (ending 2,500 years of monarchicalrule) and allow the formation of an Islamic government. Then in November 1979, the Iranian people, inanother referendum, adopted a new constitution that turned the country into anIslamic republic and raised Ayatollah Khomeini to the position of Iran’s SupremeLeader, i.e. head of state and the government’s highest ranking political,military, and religious authority. PrimeMinister Bazargan, whose liberal democratic and moderate government had heldonly little power, resigned in November 1979. By February 1980, Iranhad fully transitioned to a theocracy under Ayatollah Khomeini, with executivefunctions run by a subordinate civilian government led by President AbolhassanBanisadr.

The political unrest in Iranhad been watched closely by Iraq,Iran’sneighbor to the west, and particularly by Saddam Hussein, the Iraqidictator. In the period following theIranian Revolution, relations between the two countries appeared normal, with Iraq even offering an invitation to new IranianPrime Minister Bazargan to visit Iraq. But with Iran’stransition to a hard-line theocratic regime, relations between the twocountries deteriorated, as Iran’sIslamist fundamentalism contrasted sharply with Iraq’s secular, socialist, Arabnationalist agenda.

This breakdown in relations was only the latest in a long historyof Arab-Persian hostility that resulted from a complex combination of ethnic,sectarian, political, and territorial factors. During the period when the Ottoman Empire ruled over the Middle East(16th – 19th centuries, to early 20th century), the Ottoman Empire and PersianEmpire fought for possession of sections of Mesopotamia, (present-day Iraq),including the Shatt el-Arab, the 200-kilometer long river that separatespresent-day southern Iraq and western Iran. In 1847, the Ottomans and Persians agreed to make the Shatt al-Arabtheir common border; the Persian Empire also was given control of Khoramshahrand Abadan,areas on its western shore of the river that had large Arab populations.

Then in 1937, the now independent monarchies of Iraq and Iransigned an agreement that stipulated that their common border on the Shattal-Arab was located at the low water mark on the eastern (i.e. Iranian) sideall across the river’s length, except in the cities of Khoramshahr and Abadan,where the border was located at the river’s mid-point. In 1958, the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown ina military coup. Iraq then formed a republic and the newgovernment made territorial claims to the western section of the Iranian borderprovince of Khuzestan, which had a large populationof ethnic Arabs.

In Iraq,Arabs comprise some 70% of the population, while in Iran,Persians make up perhaps 65% of the population (an estimate since Iran’spopulation censuses do not indicate ethnicity). Iran’s demographicsalso include many non-Persian ethnicities: Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchs, andothers, while Iraq’ssignificant minority group comprises the Kurds, who make up 20% of thepopulation. In both countries, ethnicminorities have pushed for greater political autonomy, generating unrest and apotential weakness in each government of one country that has been exploited bythe other country.

The source of sectarian tension in Iran-Iraq relationsstemmed from the Sunni-Shiite dichotomy. Both countries had Islam as their primary religion, with Muslimsconstituting upwards of 95% of their total populations. In Iran, Shiites made up 90% of all Muslims(Sunnis at 9%) and held political power, while in Iraq, Shiites also held amajority (66% of all Muslims), but the minority Sunnis (33%) led by Saddam andhis Baath Party held absolute power.

In the 1960s, Iran, which was still ruled by amonarchy, embarked on a large military buildup, expanding the size and strengthof its armed forces. Then in 1969, Iran ended its recognition of the 1937 borderagreement with Iraq,declaring that the two countries’ border at the Shatt al-Arab was at theriver’s mid-point. The presence of thenow powerful Iranian Navy on the Shatt al-Arab deterred Iraq fromtaking action, and tensions rose.

Also by the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurdswere holding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the FirstIraqi-Kurdish War, separate article); negotiations collapsed and fighting brokeout in April 1974, with the Iraqi Kurds being supported militarily byIran. In turn, Iraq incited Iran’s ethnic minorities to revolt,particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, Iranian Kurds, and Baluchs. Direct fighting between Iranian and Iraqiforces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iranians prevailing. Hostilities ended when the two countriessigned the Algiers Accord in March 1975, where Iraqyielded to Iran’s demandthat the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; in exchange, Iran ended itssupport to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq wasdispleased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional militarypower, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues)during the second half of the 1970s. Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and evenenjoyed a period of rapprochement. As aresult of Iran’s assistancein helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelledAyatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iraniancleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.

September 21, 2024

September 21, 1953 – Korean War: A North Korean pilot defects to South Korea in his MiG fighter plane

On September 21, 1953, Senior Lieutenant No Kum-sok of the North Korean Air Force defected in his MiG-15 jet fighter into South Korea. No’s defection came about two months after the end of hostilities in the Korean War.

His flight of 17 minutes was not detected by the Korean Air Force nor was it spotted by U.S. air defenses, as the nearest American radar had been temporarily shut down for routine maintenance. Upon his arrival, he surrendered to U.S. authorities. He was later granted asylum in the United States and received a reward of U.S. $ 100,000 ($ 940,000 in 2018) for being the first pilot to defect with an operational aircraft.

His defection brought about reprisals in North Korea, where authorities there demoted the North Korean Air Force’s top commander and executed five of No’s comrades. His father had already passed away while his mother had earlier defected to South Korea. The fate of his other relatives in North Korea is not known.

(Excerpts taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Meanwhile, armistice talks resumed, which culminated in anagreement on July 19, 1953. Eight dayslater, July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, andthe Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement,which ended the war. A ceasefire cameinto effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed. The Korean War was over.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldierskilled, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; NorthKorean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which includedChairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying). Civilian casualties were 2 million for South Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Koreanrefugees who had moved to South Korea. Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forcesconducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to besupporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea,during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militiasexecuted some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupationof South Korea,also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries”(politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians whorefused to join the North Korean Army.

Under the armistice agreement, the frontline at the time ofthe ceasefire became the armistice line, which extended from coast to coastsome 40 miles north of the 38th parallel in the east, to 20 miles south of the38th parallel in the west, or a net territorial loss of 1,500 square miles toNorth Korea. Three days after theagreement was signed, both sides withdrew to a distance of two kilometers fromthe ceasefire line, thus creating a four-kilometer demilitarized zone (DMZ)between the opposing forces.

The armistice agreement also stipulated the repatriation ofPOWs, a major point of contention during the talks, where both partiescompromised and agreed to the formation of an independent body, the NeutralNations Repatriation Commission (NNRC), to implement the exchange ofprisoners. The NNRC, chaired by GeneralK.S. Thimayya from India, subsequently launched Operation Big Switch, where inAugust-December 1953, some 70,000 North Korean and 5,500 Chinese POWs, and12,700 UN POWs (including 7,800 South Koreans, 3,600 Americans, and 900British), were repatriated. Some 22,000Chinese/North Korean POWs refused to be repatriated – the 14,000 Chineseprisoners who refused repatriation eventually moved to the Republic of China (Taiwan),where they were given civilian status. Much to the astonishment of U.S. and British authorities, 21 Americanand 1 British (together with 325 South Korean) POWs also refused to berepatriated, and chose to move to China. All POWs on both sides who refused to be repatriated were given 90 daysto change their minds, as required under the armistice agreement.

The armistice line was conceived only as a separation offorces, and not as an international border between the two Korean states. The Korean Armistice Agreement called on thetwo rival Korean governments to negotiate a peaceful resolution to reunify the Korean Peninsula. In the international Geneva Conference heldin April-July 1954, which aimed to achieve a political settlement to the recentwar in Korea (as well as in Indochina, see First Indochina War, separatearticle), North Korea and South Korea, backed by their major power sponsors,each proposed a political settlement, but which was unacceptable to the otherside. As a result, by the end of theGeneva Conference on June 15, 1953, no resolution was adopted, leaving theKorean issue unresolved.

Since then, the KoreanPeninsula has remained divided alongthe 1953 armistice line, with the 248-kilometer long DMZ, which was originallymeant to be a military buffer zone, becoming the de facto border between North Korea and South Korea. No peace treaty was signed, with thearmistice agreement being a ceasefire only. Thus, a state of war officially continues to exist between the two Koreas. Also as stipulated by the Korean ArmisticeAgreement, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) was established,comprising contingents from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland,tasked with ensuring that no new foreign military personnel and weapons arebrought into Korea.

Because of the constant state of high tension between thetwo Korean states, the DMZ has since remained heavily defended and is the mostmilitarily fortified place on Earth. Situated at the armistice line in Panmunjom is the Joint Security Area,a conference center where representatives from the two Koreas hold negotiationsperiodically. Since the end of theKorean War, there exists the constant threat of a new war, which is exacerbatedby the many incidents initiated by North Koreaagainst South Korea. Some of these incidents include: thehijacking by a North Korean agent of a South Korean commercial airliner inDecember 1969; the North Korean abductions of South Korean civilians; thefailed assassination attempt by North Korean commandos of South KoreanPresident Park Chung-hee in January 1968; the sinking of a South Korean navalvessel, the ROKS Cheonon, in March 2010, which the South Korean governmentblamed was caused by a torpedo fired by a North Korean submarine (North Koreadenied any involvement), and the discovery of a number of underground tunnelsalong the DMZ which South Korea has said were built by North Korea to be usedas an invasion route to the south.

Furthermore, in October 2006, North Korea announced that it haddetonated its first nuclear bomb, and has since stated that it possessesnuclear weapons. With North Korea aggressively pursuingits nuclear weapons capability, as evidenced by a number of nuclear tests beingcarried out over the years, the peninsular crisis has threatened to expand toregional and even global dimensions. Western observers also believe that North Korea has since beendeveloping chemical and biological weapons.

September 20, 2024

September 20, 1942 – World War II: German SS kills 3,000 Jews in Letychiv

On September 20, 1942, German SS units murdered 3,000 Jewsin Letychiv town in western Ukraine.

The Germans captured Letychiv in July 1941 and segregated the Jewish population in a ghetto and a separate slave labor camp. The prisoners were sent to work on a road building project. Upon completion of the project, the SS was called in. Three separate mass shootings took place: in September 1942, where 3,000 Jews were killed (comprising about half of the ghetto), in November 1942, where 4,000 were killed (the rest of the ghetto’s population), and in November 1943, where 200 Jews from the labor camp were killed (this time, by the local police). Further mass executions of the remaining workers in the labor camp were carried out in the following months.

(Taken from Genocide and Slave Labor – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Because of the failure of Operation Barbarossa and succeeding campaigns, Germany was unable to implement the planned mass-scale transfer of targeted populations to the Russian interior. Elimination of the undesired populations began almost immediately following the outbreak of war, with the conquest of Poland. The killing of hundreds of thousands of civilians occurred in hundreds of incidents of massacres and mass shootings in towns and villages, reprisals against attacks on German troops, scorched earth operations, civilians trapped in the cross-fire, concentration camps, etc.

By far, the most famous extermination program was the Holocaust,where six million Jews, or 60% of the nine million pre-war European Jewishpopulation, were killed in the period 1941-1945. German anti-Jewish policies began in theNuremberg Laws of 1935, and violent repression of Jews increased at theoutbreak of war. Jews were rounded upand confined to guarded ghettos, and then sent by freight trains toconcentration and labor camps. Bymid-1942, under the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” decree, Jews weretransported to extermination camps, where they were killed in gaschambers. Some 90% of Holocaust victimswere Jews. Other similar exterminationsand repressions were carried out against ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, andother Slavs and Romani (gypsies), as well as communists and other politicalenemies, homosexuals, Freemasons, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. In Germany itself, a clandestineprogram implemented by German public health authorities under Hitler’s orders,killed tens of thousands of mentally and physically disabled patients,purportedly under euthanasia (“mercy killing”) procedures, which actuallyinvolved sending patients to gas chambers, applying lethal doses of medication,and through starvation.

Some 12-15 million slave laborers, mostly civilians fromcaptured territories in Eastern Europe, were rounded up to work in Germany,particularly in munitions factories and agriculture, to ease German laborshortage caused by the millions of German men fighting in the various frontsand also because Nazi policy discouraged German women from working inindustry. Some 5.7 million Soviet POWsalso were used as slave labor. As well,two million French Army prisoners were sent to labor camps in Germany, mainly to prevent the formation oforganized resistance in Franceand for them to serve as hostages to ensure continued compliance by the Vichy government. Some 600,000 French civilians also wereconscripted or volunteered to work in German plants. Living and working conditions for the slavelaborers were extremely dire, particularly for those from Eastern Europe. Some 60% (3.6million of the 5.7 million) of Soviet POWs died in captivity from variouscauses: summary executions, physical abuse, diseases, starvation diets, extremework, etc.

September 19, 2024

September 19, 1944 – World War II: Finland and the Soviet Union sign an armistice

On September 19, 1944, Finland and the Soviet Union signed the Moscow Armistice, ending hostilities between them. The armistice contained the same provisions as the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty that had ended the Winter War, with some additions. Finland was compelled to cede parts of Karelia and Salla, as well as some islands in the Gulf of Finland, as in the 1940 treaty. In the Moscow Armistice, Finland was also required to grant a 50-year lease right for the Soviets to construct a naval base at Porkkala (the area was returned to Finland in 1956). Other Soviet-imposed stipulations were that Finland pay war reparations to the Soviet Union in the form of commodities for six years, legalize the Finnish Communist Party, ban parties and organizations that were deemed fascist, and arraign Finnish officials “responsible for the war” (the so-called “War-responsibility trials in Finland”; Finnish: Sotasyyllisyysoikeudenkäynti). Finland also had to expel German forces from its territory, leading to the Lapland War (September 1944 – April 1945).

Finland and nearby states.

Finland and nearby states.(Taken from The Soviet Counter-offensive – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In June 1941, Finland had joined Germany in attacking the Soviet Union (albeit not as a member of the Axis) with the aim of regaining lost territory in the Winter War (separate article), and perhaps a secondary motive to gain a little more territory in support of “Greater Finland”. With these objectives, the Finnish Army made no attempt to attack Leningrad from the north, and rejected the urging by the Germans who were positioned west and south of the city.

For Stalin, however, Finlandwas a German ally, and shared Hitler’s plan to destroy the Soviet Union. By spring 1944, theFinnish Army at Karelia was isolated and in a precarious situation after theRed Army drove back the Germans from Leningradinto the Estonian border. The SovietHigh Command then made preparations to knock Finland out of the war, which wouldalso improve the strategic position of the Red Army as it continued its driveto the west.

In June 1944, the Soviet Leningrad and Karelian Fronts, witha combined 550,000 troops, 10,500 artillery pieces, 800 tanks, and 1,600planes, attacked the Finnish Army (which was outnumbered 2:1 in personnel, 5:1in artillery, 8:1 in tanks, and 6:1 in planes) in the Karelian Isthmus andeastern Karelia. The Soviets brokethrough the Finns’ first two defense lines, taking eastern Karelia and Viipuri(Vyborg), andby July 1944, had pushed back the Finns 60 miles (100 km) to the third line(VKT Line). There, the Red Army advancewas stopped, with the Finns greatly benefiting from the recently deliveredGerman anti-tank weapons that halted the Soviet armored spearheads.

In late August 1944, Finland feared that its forcescould not withstand another major Soviet offensive, and sued for peace. The Soviets accepted, and on September 4, aceasefire came into effect. Two weekslater, an armistice was signed, where the Soviets imposed harsh conditionswhich the Finnish government reluctantly accepted, including that Finlandpay war reparation, cede territory, lease territory for a Soviet naval base,and force the Germans from Finnish territory. Regarding the last stipulation, the Finns did turn against the Germans,who were still occupying northern Finland.