Daniel Orr's Blog, page 13

August 29, 2024

August 29, 1943 – World War II: The Danish Navy scuttles its ships; in response, Germany dissolves the Danish government and imposes martial law

In the early morning of August 29, 1943, the Danish Navy scuttled many of its ships at the Copenhagen harbor to prevent them from falling into German possession. Just a few hours earlier, German forces had entered the city to take over Denmark and disarm the Danish military. Of the 52 vessels of the Danish Navy (2 were in Greenland), 32 were scuttled, 4 escaped to Sweden, and 14 were captured by the Germans. Danish military casualties were 23-26 killed and 40-50 wounded; 4,600 Danish personnel were interred. Germany had invaded Denmark in April 1940 but had allowed the Danish Navy to continue its maritime responsibilities which otherwise would have been taken up the German Navy, using much-needed manpower and resources that could be used elsewhere.

Also on August 29, the Germans dissolved the Danishgovernment and imposed martial law throughout the country. The Danish cabinet tenderedits resignation, which was not accepted by King Christian, and so continued tofunction until the end of the war.

The events were the culmination of the “August crisis”, where during the summer of 1943, the Danish population launched increasingly hostile civil unrest against the German occupation forces. Worker strikes, street demonstrations, and acts of sabotage as well as passive resistance were prevalent across the country. On August 28, Germany declared Denmark as “enemy territory” following the inability of German and Danish authorities to control the unrest.

On August 28, German authorities imposed censorship on public assemblies and strikes and curfew and introduced special military courts that imposed the death penalty for acts of sabotage. At the same time, an ultimatum was issued to the Danish government, which refused, leading to the German decision to declare Denmark “enemy territory” and to take over the administration of the country.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

After the Germaninvasion of Denmark OnApril 10, 1940, German forces peacefully occupied Bornholm,Denmark’s easternmost islandlocated in the Baltic Sea. Two Danish-linked territories were seized bythe British: the Faroe Islands on April 12, and Iceland, a self-governing statewith the Danish king as its head of state, on May 10. Greenland, aDanish colony, took a different path in World War II. Henrik Kauffmann, the Danish ambassador tothe United States, signed atreaty with the U.S.government that allowed American military bases to be constructed in the islandto protect it from German invasion. Atthis time, the United Stateswas still neutral and a non-belligerent in World War II. The Danish government in Copenhagen, now controlled by the Germans asa protectorate, rejected the treaty.

In the immediate aftermath of the invasion, Denmark wasallowed to maintain much of its internal political and administrative duties,King Christian X remained as the nation’s head of state, and the legislature,police, and judiciary continued to function as before. The Danish people generally were displeasedby the German occupation, but also accepted the reality of the situation,especially after France’sdefeat only two months later, in June 1940.

By 1943, German-Danish relations had deteriorated, and Denmark’s“politics of cooperation” ended, and the Danish people became hostile towardthe occupation forces. Then when a spateof strikes, civil unrest, and sabotages broke out, and an armed resistancemovement began to emerge, German authorities dissolved the Danish government,declared martial law, and enforced anti-dissident measures, including presscensorship, banning strikes and mass assemblies, and imposing the death penaltyfor saboteurs, as well as ordering the round up of all Jews for deportation.

August 28, 2024

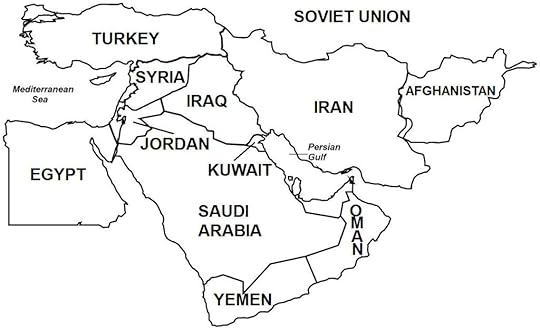

August 28, 1990 – Gulf War: Iraq annexes Kuwait

On August 4, 1990, Saddam appointed a 9-member militaryjunta composed of Kuwaiti Army officers headed by Colonel Alaa Hussein Ali, tolead the “Provisional Government of Free Kuwait”. Then on August 7, Kuwaitwas declared a republic (“Republic of Kuwait”). The next day, however, the Iraqi governmentannounced the political and territorial merger of Iraqand Kuwait. Three weeks later, on August 28, Iraqdeclared a Kuwait Governorate, Iraq’s 19th province, under Governor Ali Hassanal-Majid, Saddam’s first cousin (and also better known as heading the al-Anfalcampaign (1986-1989), where Iraqi forces violently quelled an uprising by IraqiKurds during the Iran-Iraq War).

A few hours into the Iraqi invasion, the Kuwaiti government had appealed to the international community for assistance. In a number of resolutions, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) condemned the invasion, demanded that Saddam withdraw his forces, and imposed economic sanctions on Iraq. The Arab League, the regional body in which Iraq was a member, also condemned Iraq’s aggression. On the invitation of Saudi King Fahd who felt that his country would be invaded next, the United States sent troops to Saudi Arabia. The international community, and particularly the U.S. government, entered into negotiations with Iraq regarding the withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait. These talks subsequently broke down, leading to the Gulf War, where U.S.-led coalition forces attacked Kuwait to drive out the Iraqi Army.

(Taken from Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background On June 19, 1961, Kuwait gained its independence from Britain. In 1963, Iraq, which by this time had become a republic and was presently governed by a military government under General Abd al-Karim Qasim, pursued its claim of ownership to Kuwait based on historical grounds, and threatened to invade. Swift intervention by Britain and Arab countries, which sent military units to defend Kuwait, forced Iraq to back down. Then in 1963, Iraq appeared to acquiesce, declaring that it recognized Kuwait. But tensions remained throughout the 1960s and 1970s, which sometimes broke out into border clashes that included a more significant incident where Iraqi forces attacked and seized control of the Al-Samitah border outpost in Kuwait. Subsequent mediation efforts by Saudi Arabia succeeded in persuading Iraq to withdraw from occupied Kuwaiti territory.

Meanwhile, Iraq also had a long-standing border dispute with Iran, its eastern neighbor, which broke out in September 1980 into total war (the Iran-Iraq War, separate article) following the success of the Iranian Revolution that transformed Iran into a fundamentalist Islamic state. Iran’s new Islamic government then called for the overthrow of “un-Islamic” Arab monarchies, alarming Gulf state monarchical governments including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates, which gave large financial assistance in the form of loans to Iraq. By this time, Iraq was ruled by Saddam Hussein. Iraq-Kuwait relations improved dramatically, and Kuwait’s $14 billion loan to Iraq allowed the Iraqi Army to reverse its losses against Iran and take the initiative.

By the war’s end in August 1988, Iraq was in deep financial crisis,with its oil industry severely affected by the widespread destruction of oilinfrastructures. Before the war, Iraq was awashin cash, holding some $35 billion in foreign reserves, but by 1988, was miredin $80 billion in foreign debt to various Western and Arab countries. Then in negotiations with its Arab creditors,the Iraqi government declared that its loans must be written off on the groundsthat Iraq singlehandedlystopped Iran’s hegemonicambitions and thus prevented the overthrow of the various Arab governments inthe Middle East. Tariq Aziz, Iraq’s Foreign Minister, remarked thus, “How canthese amounts be regarded as Iraqi debts to its Arab brothers when Iraq madesacrifices that are many times more than those debts in terms of Iraqiresources during the grinding war and offered rivers of blood of its youth indefense of the (Arab) nation’s soil, dignity, honor, and wealth?”

Furthermore, Kuwaitexceeded its oil production quota imposed by the Organization of PetroleumExporting Countries (OPEC), causing a glut in the international market anddriving down oil prices. The Iraqigovernment complained that the low world prices meant lesser revenues, andtherefore lower capacity for Iraqto repay its loans and restore its war-damaged oil infrastructures that wereneeded to rebuild the country.

Another source of dispute was the Rumalia oil field, locatedbetween Kuwait and Iraq and inside both countries’ territories, inwhich Iraq accused Kuwait of using an oil extraction techniqueknown as slant drilling in order to pump out oil inside Iraq. The Iraqi government demanded payment for the“stolen” oil. Kuwait vehemently denied theaccusation.

With economic troubles mounting, Saddam began to believethat a conspiracy stirred up by neighboring countries was aimed at undermininghis country. Consequently, the Iraqileader turned his appeals for financial reprieve into open threats, at onepoint remarking (in reference to Iraq’s request for more loans),“Let the Gulf regimes know, that if they will not give this money to me, I willknow how to get it.”

On July 16, 1990, on Saddam’s orders, units of theRepublican Guard, Iraq’selite force, deployed along the border with Kuwait. By the following day, the arrival of moreunits increased Iraqi strength to 10,000 troops and 300 tanks. And by July 25, Iraq had massed some 30,000 troops(in four divisions) and over 800 tanks along two fronts on the border.

United Statesintelligence detected this military movement, which later was disseminated bythe U.S.media. On July 25, 1990 April Glaspie,the U.S. Ambassador to Iraq,in a meeting with Saddam, indicated that the U.S. government was aware of theIraqi military’s deployment and that this was a cause for concern. However, Ambassador Glaspie also said the United States has “no opinion on Arab-Arabconflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait”,a remark that has since generated controversy among political analysts, onepoint being that the United Stateswould not intervene militarily if war broke out between fellow Arab Iraq and Kuwait.

During the closing week of July 1990, with mediation effortsby Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, Kuwaiti and Iraqi representatives heldtalks in Riyadh and Jeddah,Saudi Arabia, which alsofailed to reach a settlement despite Kuwaitagreeing to pay $9 billion of the Iraqi government’s demand of $10 billion for Iraq’spurported revenue losses in the Rumalia oil field.

August 27, 2024

August 27, 1928 – Interwar period: Fifteen countries sign the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which renounces war as an instrument of foreign policy

On August 27, 1928, fifteen countries signed the agreement known as the “General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy”, more commonly known as the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Its secondary name stems from its authors, U.S. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand. The instrument, first agreed to in August 1928 by the United States, France, and Germany, was joined within a year by 62 countries, including Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Soviet Union, and China. The instrument’s objective was for signatory states not to use war to resolve “disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them”, and states that fail to adhere would be “denied of the benefits furnished by the treaty”. The pact went into effect on July 24, 1929.

The Kellogg-Brian Pact failed in its objective: militarism grew in the 1930s, leading to the outbreak of World War II toward the close of the decade.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Post-World War I Pacifism Because World War I had caused considerable toll on lives and brought enormous political, economic, and social troubles, a genuine desire for lasting peace prevailed in post-war Europe, and it was hoped that the last war would be “the war that ended all wars”. By the mid-1920s, most European countries, especially in the West, had completed reconstruction and were on the road to prosperity, and pursued a policy of openness and collective security. This pacifism led to the formation in January 1920 of the League of Nations (LN), an international organization which had membership of most of the countries existing at that time, including most major Western Powers (excluding the United States). The League had the following aims: to maintain world peace through collective security, encourage general disarmament, and mediate and arbitrate disputes between member states. In the pacifism of the 1920s, the League resolved a number of conflicts (and had some failures as well), and by mid-decade, the major powers sought the League as a forum to engage in diplomacy, arbitration, and disarmament.

In September 1926, Germanyended its diplomatic near-isolation with its admittance to the League of Nations. This came about with the signing in December 1926 of the LocarnoTreaties (in Locarno, Switzerland),which settled the common borders of Germany,France, and Belgium. These countries pledged not to attack eachother, with a guarantee made by Britainand Italyto come to the aid of a party that was attacked by the other. Future disputes were to be resolved througharbitration. The Locarno Treaties alsodealt with Germany’s easternfrontier with Poland and Czechoslovakia,and although their common borders were not fixed, the parties agreed thatfuture disputes would be settled through arbitration. The Treaties were seen as a high point in international diplomacy, and ushered in a climate of peacein Western Europe for the rest of the1920s. A popular optimism, called “thespirit of Locarno”,gave hope that all future disputes could be settled through peaceful means.

In June 1930, the last French troops withdrew from the Rhineland, ending the Allied occupation five yearsearlier than the original fifteen-year schedule. And in March 1935, the League of Nationsreturned the Saar region to Germanyfollowing a referendum where over 90% of Saar residents voted to bereintegrated with Germany.

In August 1938, at the urging of the United States and France, the Kellogg-BriandPact (officially titled “General Treatyfor Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy”) was signed, whichencouraged all countries to renounce war and implement a pacifist foreign policy. Within a year, 62 countries signed the Pact,including Britain, Germany, Italy,Japan, the Soviet Union, andChina. In February 1929, the Soviet Union, asignatory and keen advocate of the Pact, initiated a similar agreement, calledthe Litvinov Protocol, with its Eastern European neighbors, which emphasizedthe immediate implementation of the Kellogg-Briand Pact among themselves. Pacifism in the interwar period alsomanifested in the collective efforts by the major powers to limit theirweapons. In February 1922, the fivenaval powers: United States,Britain, France, Italy,and Japansigned the Washington Naval Treaty, which restricted construction of the largerclasses of warships. In April 1930,these countries signed the London Naval Treaty, which modified a number ofclauses in the Washingtontreaty but also regulated naval construction. A further attempt at naval regulation was made in March 1936, which wassigned only by the United States, Britain, and France, since by this time, theprevious other signatories, Italy and Japan, were pursuing expansionistpolicies that required greater naval power.

An effort by the League of Nations and non-League member United States to achieve general disarmament inthe international community led to the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva in 1932-1934,attended by sixty countries. The talksbogged down from a number of issues, the most dominant relating to thedisagreement between Germany and France, with the Germans insisting on beingallowed weapons equality with the great powers (or that they disarm to thelevel of the Treaty of Versailles, i.e. to Germany’s current militarystrength), and the French resisting increased German power for fear of aresurgent Germany and a repeat of World War I, which had caused heavy Frenchlosses. Germany,now led by Adolf Hitler (starting in January 1933), pulled out of the WorldDisarmament Conference, and in October 1933, withdrew from the League of Nations. The Genevadisarmament conference thus ended in failure.

August 26, 2024

August 26, 1922 – Turkish War of Independence: The Turkish Army launches the “Great Offensive” to expel Greek forces from Western Anatolia

On August 26, 1922, the Turkish Army launched its long awaitedcounter-attack against the Greek forces. Holding a 3:1 numerical andconsiderable material advantage, the Turkish forces easily overpowered andexpelled the Greek Army from Anatolia. OnSeptember 9, the Turkish Army reached the Aegean cost with the recapture of Smyrna (present-day Izmir).On September 18, Erdek and Biga were taken, which ended the fighting. By then,Greek forces had ceased to be an effective fighting unit, and demoralization anddissension had forced a hasty, disorganized retreat. In the aftermath, theGreeks withdrew from western Anatolia.

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres.

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres.The Greco-Turkish War formed one part of the Turkish War ofIndependence.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Rise of the Turkish Independence MovementUnder the armistice agreement, the Ottoman government was required to disarmand demobilize its armed forces. OnApril 30, 1919, Mustafa Kemal, a general in the Ottoman Army, was appointed asthe Inspector-General of the Ottoman Ninth Army in Anatolia,with the task of demobilizing the remaining forces in the interior. Kemal was a nationalist who opposed theAllied occupation, and upon arriving in Samsunon May 19, 1919, he and other like-minded colleagues set up what became theTurkish Nationalist Movement.

Contact was made with other nationalist politicians andmilitary officers, and alliances were formed with other nationalistorganizations in Anatolia. Military units that were not yet demobilized,as well as the various armed bands and militias, were instructed to resist theoccupation forces. These variousnationalist groups ultimately would merge to form the nationalists’ “NationalArmy” in the coming war. Weapons andammunitions were stockpiled, and those previously surrendered were secretlytaken back and turned over to the nationalists.

On June 21, 1919, Kemal issued the Amasya Circular, whichdeclared among other things, that the unity and independence of the Turkishstate were in danger, that the Ottoman government was incapable of defendingthe country, and that a national effort was needed to secure the state’sintegrity. As a result of this circular,Turkish nationalists met twice: at the Erzerum Congress (July-August 1991) byregional leaders of the eastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September1919) of nationalist leaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from thesemeetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth the guidelines for the Turkishstate, including what constituted the “homeland of the Turkish nation”, andthat the “country should be independent and free, all restrictions onpolitical, judicial, and financial developments will be removed”. The “Representative Committee” was theprecursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3, 1920 asthe Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara(in central Anatolia), founded and led byKemal.

Kemal and his Representative Committee “government”challenged the continued legitimacy of the national government, declaring that Constantinople was ruled by the Allied Powers from whomthe Sultan had to be liberated. However,the Sultan condemned Kemal and the nationalists, since both the latter effectivelyhad established a second government that was a rival to that in Constantinople.

In July 1919, Kemal received an order from the nationalauthorities to return to Constantinople. Fearing for his safety, he remained in Ankara; consequently, heceased all official duties with the Ottoman Army. The Ottoman government then laid down treasoncharges against Kemal and other nationalist leaders; tried in absentia, he wasdeclared guilty on May 11, 1920 and sentenced to death.

Initially, British authorities played down the threat posedby the Turkish nationalists. Then whenthe Ottoman parliament in Constantinopledeclared its support for the nationalists’ National Pact and the integrity ofthe Turkish state, the British violently closed down the legislature, an actionthat inflicted many civilian casualties. The next month, the Sultan affirmed the dissolution of the Ottomanparliament.

Many parliamentarians were arrested, but many others escapedcapture and fled to Ankarato join the nationalists. On April 23,1920, a new parliament called the Grand National Assembly convened in Ankara, which electedKemal as its first president.

British authorities soon realized that the nationalistmovement threatened the Allied plans on the Ottoman Empire. From civilian volunteers and units of theSultan’s Caliphate Army, the British organized a militia, which was tasked todefeat the nationalist forces in Anatolia. Clashes soon broke out, with the most intensetaking place in June 1920 in and around Izmit, where Ottoman and British forcesdefeated the nationalists. Defectionswere widespread among the Sultan’s forces, however, forcing the British todisband the militia.

The British then considered using their own troops, butbacked down knowing that the British public would oppose Britain being involved in anotherwar, especially one coming right after World War I. The British soon found another ally to fightthe war against the nationalists – Greece. On June 10, 1920, the Allies presented theTreaty of Sevres to the Sultan. Thetreaty was signed by the Ottoman government but was not ratified, since waralready had broken out.

In the coming war, Kemal crucially gained the support of thenewly established Soviet Union, particularly in the Caucasuswhere for centuries, the Russians and Ottomans had fought for domination. This Soviet-Turkish alliance resulted fromboth sides’ condemnation of the Allied intervention in their local affairs,i.e. the British and French enforcing the Treaty of Sevres on the Ottoman Empire, and the Allies’ open support foranti-Bolshevik forces in the Russian Civil War.

August 25, 2024

August 25, 1991 – Croatian War of Independence: The start of the 87-day Battle of Vukovar

On August 25, 1991, some 36,000 troops of the Yugoslav Army, aided by Serb paramilitaries, launched an attack against the lightly-armed 1,800 Croatian National Guard fighters in Vukovar in eastern Croatia. Supported by air, armored, and artillery units, the Yugoslav-Serb forces broke through on November 18, 1991 after an 87-day siege and offensive. Vukovar was subjected to intense shell and rocket bombardment and was completely destroyed. For the Yugoslav Army, the battle was won at great cost, with 1,100 killed and 2,500 wounded, and the loss of 110 tanks and armoured vehicles and 3 planes. Croatian casualties were 900 killed and 800 wounded. Some 1,100 civilians also perished.

In the aftermath, several hundred Croatian soldiers andcivilians were executed, and 20,000 residents comprising the non-Serbpopulation were expelled from the town. Vukovar was thereafter annexed into theself-declared Republic of Serbian Krajina.

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia(Taken from Croatian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background By the late 1980s, Yugoslavia was faced with a major political crisis, as separatist aspirations among its ethnic populations threatened to undermine the country’s integrity (see “Yugoslavia”, separate article). Nationalism particularly was strong in Croatia and Slovenia, the two westernmost and wealthiest Yugoslav republics. In January 1990, delegates from Slovenia and Croatia walked out from an assembly of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country’s communist party, over disagreements with their Serbian counterparts regarding proposed reforms to the party and the central government. Then in the first multi-party elections in Croatia held in April and May 1990, Franjo Tudjman became president after running a campaign that promised greater autonomy for Croatia and a reduced political union with Yugoslavia.

Ethnic Croatians, who comprised 78% of Croatia’s population, overwhelmingly supportedTudjman, because they were concerned that Yugoslavia’snational government gradually had fallen under the control of Serbia, Yugoslavia’s largest and mostpowerful republic, and led by hard-line President Slobodan Milosevic. In May 1990, a new Croatian Parliament wasformed and subsequently prepared a new constitution. The constitution was subsequently passed inDecember 1990. Then in a referendum heldin May 1991 with Croatian Serbs refusing to participate, Croatians votedoverwhelmingly in support of independence. On June 25, 1991, Croatia,together with Slovenia,declared independence.

Croatian Serbs (ethnic Serbs who are native to Croatia) numbered nearly 600,000, or 12% of Croatia’stotal population, and formed the second largest ethnic group in therepublic. As Croatiaincreasingly drifted toward political separation from Yugoslavia, the Croatian Serbsbecame alarmed at the thought that the new Croatian government would carry outpersecutions, even a genocidal pogrom against Serbs, just as the pro-Naziultra-nationalist Croatian Ustashe government had done to the Serbs, Jews, andGypsies during World War II. As aresult, Croatian Serbs began to militarize, with the formation of militias aswell as the arrival of armed groups from Serbia.

Croatian Serbs formed a population majority in south-west Croatia(northern Dalmatian and Lika). There, inFebruary 1990, they formed the Serb Democratic Party, which aimed for thepolitical and territorial integration of Serb-dominated lands in Croatia with Serbiaand Yugoslavia. They declared that if Croatia wanted to secede from Yugoslavia, they, in turn, should be allowed toseparate from Croatia. Serbs also interpreted the change in theirstatus in the new Croatian constitution as diminishing their civil rights. In turn, the Croatian government opposed theCroatian Serb secession and was determined to keep the republic’s territorialintegrity.

In July 1990, a Croatian Serb Assembly was formed thatcalled for Serbian sovereignty and autonomy. In December, Croatian Serbs established the SAO Krajina (SAO is theacronym for Serbian Autonomous Oblast) as a separate government from Croatia in the regions of northern Dalmatia and Lika. Croatian Serbs formed a majority population in two other regions in Croatia, which they also transformed intoseparate political administrations called SAO Western Slavonia, and SAO EasternSlavonia (officially SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western Syrmia). (Map 17 showslocations in Croatiawhere ethnic Serbs formed a majority population.) In a referendum held inAugust 1990 in SAO Krajina, Croatian Serbs voted overwhelmingly (99.7%) forSerbian “sovereignty and autonomy”. Thenafter a second referendum held in March 1991 where Croatian Serbs votedunanimously (99.8%) to merge SAO Krajina with Serbia, the Krajina governmentdeclared that “… SAO Krajina is a constitutive part of the unified stateterritory of the Republic of Serbia”.

August 23, 2024

August 23, 1939 – Germany and the Soviet Union sign a non-aggression pact; World War II begins just over a week later

On August 23, 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the “Treaty of Non-aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics”, where both sides agreed not attack the other or be alliance to or assist the enemy of either side. The treaty became known in the West as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, so named for the foreign ministers Vyacheslav Molotov of the Soviet Union and Joachim von Ribbentrop of Germany.

The treaty included a secret protocol that delineated each side’s spheres of influence in the regions between them: Poland, Romania, the Baltic states Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and Finland. The non-aggression treaty was made public, but the secret protocol became known only at the end of World War II from the German copy of the document found in Nazi archives. The treaty ended when Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

The treaty allowed Germanyfree rein to attack Polandon September 1, 1939, launching what would unexpectedly become the global WorldWar II.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background to the German Invasion of Poland Britain and France, which had pursued appeasement toward Hitler, had become wary after the German occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia, which had a non-ethnic German majority population, which was in contrast to what Hitler had said that he only wanted returned those German-populated territories. Britain and France were now determined to resist Germany diplomatically and resolve the crisis through firm negotiations. On March 31, 1939, Britain and France announced that they would “guarantee Polish independence” in case of foreign aggression. Since 1921, as per the Franco-Polish Military Alliance, France had pledged military assistance to Poland if that latter was attacked.

In fact, Hitler’s intentions on Poland was not only thereturn of lost German territories, but the elimination of the Polish state andannexation of Poland as part of Lebensraum (“living space”), German expansioninto Eastern Europe and Russia. Lebensraum called for the eradication of the native populations in theseconquered areas. For Poland specifically, on August 22,1939 in the lead-up to the German invasion, Hitler had said that “the object ofthe war is … to kill without pity or mercy all men, women, and children ofPolish descent or language. Only in thisway can we obtain the living space we need.” In April 1939, Hitler instructed the German military High Command tobegin preparations for an invasion of Poland, to be launched later in thesummer. By May 1939, the German militaryhad drawn up the invasion plan.

In May 1939, Britainand France held high-leveltalks with the Soviet Union regarding forming a tripartite military allianceagainst Germany, especiallyin light of the possible German invasion of Poland. These talks stalled, because Poland refused to allow Soviet forces into itsterritory in case Germanyattacked. Unbeknown to Britain and France,the Soviet Union and Germanywere also conducting (secret) separate talks regarding bilateral political,military, and economic concerns, which on August 23, 1939, led to the signingof a non-aggression treaty. This treaty,which was broadcast to the world and widely known as the Molotov RibbentropPact (named after Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German ForeignMinister Joachim von Ribbentrop), brought a radical shift to the European powerbalance, as Germany was now free to invade Poland without fear of Sovietreprisal. The pact also included asecret protocol where Poland,Finland, Estonia, Latvia,Lithuania, and Romaniawere divided into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

One day earlier, August 22, with the non-aggression treatyvirtually assured, Hitler set the invasion date of Poland for August 26, 1939. On August 25, Hitler told the Britishambassador that Britain mustagree to the German demands on Poland,as the non-aggression pact freed Germany from facing a two-front warwith major powers. But on that same day,Britain and Poland signed a mutual defense pact, whichcontained a secret clause where the British promised military assistance if Poland was attacked by Germany. This agreement, as well as British overturesthat Britain and Poland were willing to restart the stalled talkswith Germany,forced Hitler to abort the invasion set for the next day.

August 22, 2024

August 22, 1910 – Japan annexes Korea

On August 22, 1910, Japanannexed Koreawith the signing of the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty. The annexation was theculmination of Japan’s gradualdomination over Korea overthe years following a bilateral treaty in 1905 where Koreabecame a protectorate of Japan,and another treaty in 1907 where Koreaceded administration of its internal affairs to Japan.

The 1910 annexation became effective on August 29, which included the first article: “His Majesty the Emperor of Korea makes the complete and permanent cession to His Majesty the Emperor of Japan of all rights of sovereignty over the whole of Korea”. The Korean crown later denounced the treaty, saying it had been signed under duress.

The annexation came following Japan’s victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War for control of Korea and southern Manchuria.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century -Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War Despite its defeat, Russia continued to be regarded as a major European power. Russia’s greatest loss was its prestige, as it had been humiliated by a tiny Asian nation, and one that had only recently modernized. The Russian monarchy was weakened politically by the war and from the internal unrest in 1905, but survived twelve more years in power. In March 1917, following another revolution amid the Russian defeats in ongoing World War I, Tsar Nicholas II was forced to abdicate the throne, and the Russian monarchy came to an end.

In Japan,the immediate effect of the war was outrage and frustration by the Japanesepeople, who believed that their nation had been deprived of greater benefitsfrom the war, particularly war reparation and more territory. Protest demonstrations broke out in thecities, which sometimes degenerated into violence and riots. People were angry at their own government foragreeing to the treaty, and also at U.S. President Roosevelt, whom they accusedof siding with the Russians during the negotiations.

However, for Japan,the long-term effects of the war were much more favorable, as it became thesupreme power in East Asia, and its status asan equal of the major European powers was strengthened. In August 1910, Japanabrogated Korea’s nominalindependence (long recognized by the major powers) and annexed Korea,generating no response from the European powers. Japan then continued to expandmilitarily.

Japan’svictory in the Russo-Japanese War also dashed the then prevailing notion thatCaucasians were military superior to Asians. Japan’s feat alsogave hope to the colonized peoples of Southeast Asia(e.g. Vietnamese, Indonesians, Filipinos, etc) who were aspiring forindependence from their European and American colonial masters.

August 21, 2024

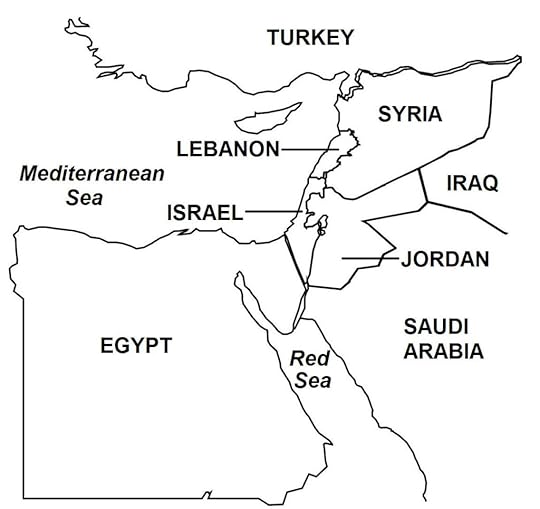

August 21, 1982 – 1982 Lebanon War: A peacekeeping force arrives in Beirut to enforce a ceasefire and oversee the withdrawal of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO)

(Taken from 1982 Lebanon War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

On August 18, 1982, after a seven-week siege of the Lebanese capital Beirut, Israel, Lebanon, and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) agreed to a ceasefire, which was made about through mediation efforts of U.S. Special Envoy Philip Habib. The ceasefire contained the following stipulations: an end to the war, departure of all foreign forces from Lebanon, and establishment of a Multinational Forces (MNF) to enforce the ceasefire. On August 21, 1982, the MNF, which ultimately consisted of contingents of the armed forces of the United States, France, Italy, and Britain, arrived in Beirut. With security protection provided by the MNF, over 6,000 PLO fighters left Beirut and transferred to Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Sudan, Yemen, Greece, and Tunisia. The operation was carried out over 15 days starting on August 27, with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat leaving on August 30 aboard a merchant ship bound for Tunisia.

The Israeli government put pressure on new Lebanesepresident, Bachir Gemayel, to enter into a peace treaty with Israel. President Gemayel refused, as the LebaneseCivil War was still ongoing and the continued presence of the Syrian Armythreatened the local political and security climates. On September 14, President Gemayel wasassassinated. The next day, Israeliforces occupied Muslim-dominated West Beirut,and blocked off escape routes from the area. A Christian militia associated with the assassinated president enteredthe Sabra and Shatila refugee camps (supposedly to arrest PLO fighters whostill remained in the city) and carried out widespread violence against theresidents. Various estimates put thenumber of casualties for the attacks at between 800 and 3,500 personskilled. In December 1982, the UnitedNations General Assembly, voting 123 – 0 (with 22 abstentions and 12non-voting), condemned the attacks, calling them “genocide”.

The massacre was denounced also in Israel. A fact-finding investigation by the Israeligovernment (called the Kahan Commission) determined that Israel’s DefenseMinister, the armed forces chief of staff, and Director of MilitaryIntelligence, were negligent in their duties to prevent the killings. Because of foreign and local pressures,Israeli forces withdrew from Beirut, and theMNF, which had left Lebanonon September 11, 1982 after the PLO withdrawal, returned to Beirut for peace-keeping duties. Ultimately, however, the MNF would leave Lebanon permanently in March 1984 following bombattacks on the U.S. Embassy and on the American and French MNF barracks, all inBeirut.

Israeli Occupation ofSouth Lebanon By the summer of 1983, Israelcontinued to occupy central Lebanon. In January 1985, Israelwithdrew most of its troops from Lebanon,leaving a small force in South Lebanon to protect, together with Israel’sChristian ally, the South Lebanon Army (SLA), a narrow strip of land that theIsraelis called the “security zone”. TheIsraelis and SLA installed check points and outposts in strategic areas alongthe security zone to cut off guerilla infiltration routes from South Lebanoninto northern Israel.

In 1985, a Palestinian armed group called Hezbollah wasformed in South Lebanon in opposition to the occupation and with the intent ofdriving away the Israelis from Lebanon. Hezbollah grew rapidly and filled the armedvoid left by the PLO by attacking Israeli forces and their allies in SouthLebanon as well carrying out cross-border attacks in northern Israel.

In July 1993, a Hezbollah rocket attack in Israel and the killing of five Israeli soldiersprompted Israel to launch amajor offensive in South Lebanon (calledOperation Accountability). In a scorched-earthcampaign, the Israelis destroyed thousands of homes, turning some 300,000Lebanese civilians into refugees. Thenagain in April 1996, in response to Hezbollah artillery attacks in northern Israel, Israeli forces launched air strikes andartillery bombardment (Operation Grapes of Wrath) on Hezbollah targets in South Lebanon.

After 15 years, Lebanon’s civil war ended with theLebanese government’s implementation of the Taif Agreement. Local public opinion mounted in Israel against the continued occupation of South Lebanon. InMay 2000, Israel withdrewits forces from South Lebanon in compliancewith United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 425. As a result, Hezbollah gained full control ofSouth Lebanon and continued to launch attacks on Israel.

After the civil war, Lebanon began the task ofrebuilding its devastated economic and social infrastructures. Local and international pressures mountedagainst the continued military and political control of Syria on Lebanon’s internal affairs. Then in April 2005, in compliance with UNSCResolution 1559, Syriawithdrew its forces from Lebanon.

August 20, 2024

August 20, 1988 – Iran and Iraq agree to a ceasefire after eight years of fighting

On July 20, 1988, the UN Security Council issued Resolution 598 that called for a ceasefire and, among other stipulations, ordered that Iran and Iraq withdraw their forces to international borders (i.e. their pre-war borders). Both sides agreed to the ceasefire, which came into effect on August 20, 1988, marking the end of the war. Two weeks later, the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG), a UN multi-national peacekeeping force, arrived to enforce the ceasefire agreement.

Casualty estimates in the Iran-Iraq war vary widely amongdifferent sources, but a total of one million to perhaps twice that number mayhave perished in the conflict. Some300,000 civilians were killed, with Iraqi Kurds suffering the most, accountingfor 60% of that number. Some laterhistorians of the war have offered lower total casualty figures.

(Taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Aftermath At the close of the war, Iraq intensified its military operations in Iraqi Kurdistan, and in a swift and ruthless campaign that involved some 200,000 Iraqi troops, inflicted tens of thousands of deaths among Iraqi Kurds, depopulated and destroyed villages, and by September 1988, had put an end to the Kurdish rebellion.

Both Iraqand Iran declared victory inthe war, and each had some merit to its respective claim: Iraq had gained the upper hand by the latterstages, while Iran,despite having much fewer weapons, had fought remarkably well and held theinitiative for much of the war. However,the war essentially ended in a stalemate, as no political or territorial gainshad been achieved by either side. Moreover, both countries failed to achieve their primary objectives inthe war, with Iraq unable toannex oil-rich Khuzestan and Iranfailing to overthrow Saddam and turning Iraq into an Islamic state.

Politically, the two countries were strengthened by thewar. Saddam had officially becomepresident in 1979, just one year before the start of the war (although he hadbeen the behind-the-scenes strongman and de facto head of the regime for manyyears), but the war allowed him to consolidate power and rule as a dictatorwith overwhelming popular support. In Iran,the war likewise united Iranians to religious-nationalist fervor, allowing theIslamic government to eliminate the (secular) opposition and consolidatepower. Ayatollah Khomeini passed away inJune 1989 and was succeeded by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who together withincoming President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, somewhat toned down Iran’shard-line Islamic stance and adopted a more nationalist policy.

Both sides’ economies were devastated (a combined $1.2trillion was lost), as a large portion of their oil-producing infrastructures,the mainstay of their economies, had been destroyed and would take many yearsto rehabilitate and return to pre-war capacities. However, Iraq suffered much greater financialvulnerability as it had become saddled with a large foreign loan (some $130billion) to Arab and western countries in order to fund its army (by makinglarge weapons purchases) which, by the end of the war, was the world’s fourthlargest, boasting some 1.2 million soldiers, 4,500 tanks, 500 planes, and 4,000artillery pieces.

Post-war tensions remained high, and both countries rebuilttheir war arsenals with substantial weapons purchases, particularly from theSoviet Union and China. Peace negotiations in Geneva, Switzerlandto achieve a permanent settlement failed mainly because of the two sides’ rivalclaims to the Shatt al-Arab.

In August 1990, Iraqinvaded and annexed Kuwait(Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait, separate article), drawing internationalcondemnation. As relations becamestrained with western powers, particularly the United States and Britain,Saddam toned down his hard-line stance against Iran and accepted the Islamicstate’s position on their territorial dispute. Subsequently, Iranand Iraq signed a peaceagreement that had the following important provisions: restoration ofdiplomatic relations, the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was their border,withdrawal of Iraqi troops from remaining territory in Iran, and exchange of prisoners ofwar. Many of these provisions werecarried out, and UNIIMOG ended its mission and departed in February 1991. The final exchange of war prisoners tookplace in March 2003.

August 19, 2024

August 19, 1945 – First Indochina War: Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh take control of Hanoi

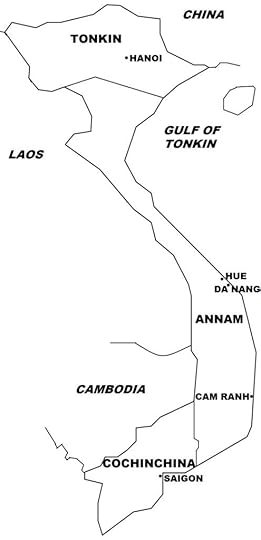

On August 19, 1945, Ho Chi Minh, leader of the Viet Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam) took control of Hanoi in northern Vietnam. There, he announced the formation of a provisional government under a democratic republic comprising the whole of Vietnam. On September 2, 1945, he declared Vietnam’s independence.

This declaration of independence was culmination of the August Revolution, a nationalist struggle that began on August 14, 1945 aimed at preventing the return of French colonial rule in Vietnam. Within two weeks, the Viet Minh had taken control of most cities across the northern, central, and southern regions of Vietnam.

Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina.

Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina.(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background In May1941, after a thirty-year absence from Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh returned andorganized in northern Vietnam the “League for the Independence of Vietnam”,more commonly known as Viet Minh (Vietnamese: Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng Minh Hội),an ICP-led merger of Vietnamese nationalist movements, aimed at ending bothFrench and Japanese rule. Ho became theleader of the Vietnamese independence struggle, a position he would holdpermanently until his death in 1969.

During World War II, the Viet Minh and Allied Powers formeda tactical alliance in their shared effort to defeat a common enemy. In particular, Ho’s fledging small band offighters liaisoned with the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), furnishingthe Americans with intelligence information on the Japanese, while the U.S.military provided the Vietnamese fighters with training, some weapons, andother military support.

By early 1945, World War II invariably had turned in favorof the Allies, with Germanyverging on defeat and Japanbecoming increasingly threatened by the Allied island-hopping Pacificcampaign. In March 1945, the Japanesemilitary overthrew the French administration in Indochina, because of fears ofan Allied invasion of the region following the U.S.recapture of the Philippines(October 1944–April 1945), and also because the Japanese began to distrustFrench loyalty following the end of Vichy France (November 1942) and the subsequent Alliedliberation of France(early 1945). In place of the Frenchadministration, on March 11, 1945, Japanese authorities installed a Vietnamesegovernment led by former emperor Bao Dai, and then proclaimed the“independence” of Vietnam,an act that was largely dismissed as spurious by the Vietnamese people.

On August 14, 1945, Japan announced its acceptance ofthe terms of the Potsdam Declaration, marking the end of the Asia-Pacifictheatre of World War II (the European theater of World War II had endedearlier, on May 8, 1945). The suddenJapanese capitulation left a power vacuum that was quickly filled by the VietMinh, which in the preceding months, had secretly organized so-called “People’sRevolutionary Committees” throughout much of the colony. These “People’s Revolutionary Committees” nowseized power and organized local administrations in many towns and cities, moreparticularly in the northern and central regions, including the capital Hanoi. This seizure of power, historically calledthe August Revolution, led to the abdication of ex-emperor Bao Dao and thecollapse of his Japanese-sponsored government.

The August Revolution succeeded largely because the VietMinh had gained much popular support following a severe famine that hitnorthern Vietnam in the summer of 1944 to 1945 (which caused some 400,000 to 2million deaths). During the famine, theViet Minh raided several Japanese and private grain warehouses. On September 2, 1945 (the same day Japansurrendered to the Allies), Ho proclaimed the country’s independence as theDemocratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), taking the position of President of aprovisional government.

At this point, Ho sought U.S.diplomatic support for Vietnam’sindependence, and incorporated part of the 1776 U.S. Declaration ofIndependence in his own proclamation of Vietnamese independence. Ho also wrote several letters to U.S.President Harry Truman (which were unanswered), and met with U.S. StateDepartment and OSS officials in Hanoi. However, during the war-time PotsdamConference (July 17 – August 2, 1945), the Allied Powers (including the SovietUnion) decided to allow France to restore colonial rule in Indochina, but thatin the meantime that France was yet preparing to return, Vietnam was to be partitionedinto two zones north and south of the 16th parallel, with Chinese Nationalistforces tasked to occupy the northern zone, and British forces (with some Frenchunits) tasked to enter the southern zone.

By mid-September 1945, Chinese and British forces hadoccupied their respective zones. Theythen completed their assigned tasks of accepting the surrender of, as well asdisarming and repatriating the Japanese forces within their zones. In Saigon,British forces disbanded the Vietnamese revolutionary government that had takenover the administration of the city. This Vietnamese government in Saigon, called the “Provisional ExecutiveCommittee”, was a coalition of many organizations, including the religious groupsCao Dai and Hoa Hao, the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen, the communists,and nationalist organizations. InCochinchina and parts of Annam,unlike in Tonkin, the Viet Minh had onlyestablished partial authority because of the presence of these many rivalideological movements. But believingthat nationalism was more important than ideology to achieve Vietnam’sindependence, the Viet Minh was willing to work with other groups to form aunited front to oppose the return of French rule.

As a result of the British military actions in the southernzone, on September 17, 1945, the DRV in Hanoilaunched a general strike in Saigon. British authorities responded to the strikesby declaring martial law. The Britishalso released and armed some 1,400 French former prisoners of war; the latter thenlaunched attacks on the Viet Minh, and seized key government infrastructures inthe south. On September 24, 1945,elements of the Binh Xuyen crime syndicate attacked and killed some 150 Frenchnationals, which provoked retaliatory actions by the French that led toincreased fighting. British and Frenchforces soon dispersed the Viet Minh from Saigon. The latter responded by sabotaging ports,power plants, communication systems, and other government facilities.

By the third week of September 1945, much of southern Vietnamwas controlled by the French, and the British ceded administration of theregion to them. In late October 1945,another British-led operation broke the remaining Viet Minh resistance in thesouth, and the Vietnamese revolutionaries retreated to the countryside wherethey engaged in guerilla warfare. Alsoin October, some 35,000 French troops arrived in Saigon. In March 1946, British forces departed from Indochina, ending their involvement in the region.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, some 200,000 Chineseoccupation forces, led by the warlord General Lu Han, allowed Ho Chi Minh andthe Viet Minh to continue exercising power in the north, on the condition thatHo include non-communists in the Viet Minh government. To downplay his communist ties, in November1945, Ho dissolved the ICP and called for Vietnamese nationalist unity. In late 1945, a provisional coalitiongovernment was formed in the northern zone, comprising the Viet Minh and other nationalistorganizations. In January 1946,elections to the National Assembly were held in northern and central Vietnam,where the coalition parties agreed to a pre-set division of electoral seats.