Daniel Orr's Blog, page 12

September 8, 2024

September 8, 1945 – The U.S. Army enters the southern half of Korea up to the 38th parallel after Soviet forces occupy the northern half

On August 16, 1945, Soviet forces from Manchuria continuedsouth into the Korean Peninsula and stopped atthe 38th parallel. U.S.forces soon arrived in southern Koreaand advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8, 1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S.and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in theirrespective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commandsestablished military rule in their occupation zones.

East Asia

East Asia(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

As both the U.S. and Soviet governments wanted to reunify Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December 1945, the Allied Powers agreed to form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China) five-year trusteeship over Korea. During the five-year period, a U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission would work out the process of forming a Korean government. But after a series of meetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve anything. In September 1947, the U.S. government referred the Korean question to the United Nations (UN). The reasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission’s failure to agree to a mutually acceptable Korean government are three-fold and to some extent all interrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed U.S.-Soviet trusteeship; the struggle for power among the various ideology-based political factions; and most important, the emerging Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Historically, Koreafor many centuries had been a politically and ethnically integrated state,although its independence often was interrupted by the invasions by itspowerful neighbors, Chinaand Japan. Because of this protracted independence, inthe immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, andviewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run theirown affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’spolitical climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, fromright-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashedwith each other for political power. Asa result of Japan’sannexation of Koreain 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were theunrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea”led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and a communist-allied anti-Japanesepartisan militia led by Kim Il-sung. Both men would play major roles in the Korean War. At the same time, tens of thousands of Koreanstook part in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese CivilWar, joining and fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces, orfor Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japanese resistance movement, which operatedmainly out of Manchuria, was divided alongideological lines. Some groups advocatedWestern-style capitalist democracy, while others espoused Sovietcommunism. However, all were stronglyanti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria,China, and Korea.

On their arrival in the southern Korean zone in September1948, U.S.forces imposed direct rule through the United States Army Military GovernmentIn Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members ofthe Korean Communist Party in Seoul(the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeatedJapanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Koreanpeninsula. Then two days before U.S.forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee”proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under the auspices of a U.S. military agent, Syngman Rhee, the formerpresident of the “Provisional Government of the Republicof Korea” arrived in Seoul. The USAMGIK refused to recognize the communist Korean People’s Republic,as well as the pro-West “Provisional Government”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form apolitical coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S.sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South KoreanInterim Legislative Assembly. However,this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wingand right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S. authorities’ breaking up thecommunists’ “people’s committees” violence broke out in the southern zoneduring the last months of 1946. Calledthe Autumn Uprising, the unrest was carried out by left-aligned workers,farmers, and students, leading to many deaths through killings, violentconfrontations, strikes, etc. Althoughin many cases, the violence resulted from non-political motives (such astargeting Japanese collaborators or settling old scores), American authoritiesbelieved that the unrest was part of a communist plot. They therefore declared martial law in thesouthern zone. Following the U.S.military’s crackdown on leftist activities, the communist militants went intohiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would playa role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, Soviet commanders initiallyworked to form a local administration under a coalition of nationalists,Marxists, and even Christian politicians. But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who alsowas a Soviet Red Army officer, quickly became favored by Soviet authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’sCommittee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by KimIl-sung who soon consolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christianleaders), and nationalized industries, and launched centrally planned economicand reconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model emphasizing heavyindustry.

By 1947, the Cold War had begun: the Soviet Union tightenedits hold on the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United Statesannounced a new foreign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed at stopping thespread of communism. The United States also implemented the MarshallPlan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which wascondemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed at dividingEurope. As a result, Europe became divided intothe capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting these developments, in Koreaby mid-1945, the United States became resigned to the likelihoodthat the temporary military partition of the Korean peninsula at the 38thparallel would become a permanent division along ideological grounds. In September 1947, with U.S. Congressrejecting a proposed aid package to Korea,the U.S.government turned over the Korean issue to the UN. In November 1947, the United Nations GeneralAssembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’ssovereignty and called for elections throughout the Korean peninsula, which wasto be overseen by a newly formed body, the United Nations Temporary Commissionon Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Soviet government rejected the UNGA resolution,stating that the UN had no jurisdiction over the Korean issue, and preventedUNTCOK representatives from entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were heldonly in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experiencedwidespread violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, alegislative body. Two months later (inJuly 1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitutionwhich established a presidential form of government. Syngman Rhee, whose party won the most numberof legislative seats, was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southernersproclaimed the birth of the Republicof Korea (soon more commonly known as South Korea), ostensibly with the state’ssovereignty covering the whole Korean Peninsula.

September 7, 2024

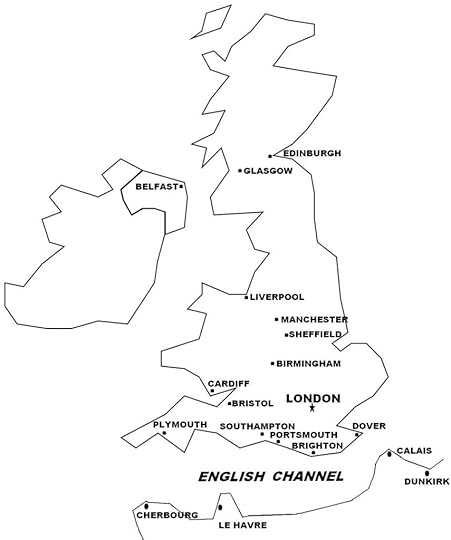

September 7, 1940 – World War II: German planes launch concentrated bombings of British urban centers

On September 7, 1940, in what the British called the “Blitz”,the German Luftwaffe began a series of concentrated attacks of British urban centers,launching 600 bombers and 400 fighters that came in successive bombing waves onthe center of London.Large-scale Luftwaffe bombing attacks continued for the next several weeks,hitting residential, industrial, and military targets and public worksfacilities in many major centers across Britain,including Bristol, Cardiff,Portsmouth, Plymouth,Southampton, Swansea, Birmingham,Belfast, Coventry,Glasgow, Manchester,and Sheffield. Some 40,000 civilians were killed, and 50,000 wounded, while one millionhouses were destroyed or damaged.

On September 15, 1940, in what is known as the “Battle ofBritain Day”, a combined 1,700 planes (1,100 Luftwaffe and 600 RAF) fought aday-long air battle in the skies over London, in what Goering hoped would bethe ultimate destruction of the RAF. Bythen, the constant German pressure during Alderagriff (since August 24) hadgreatly strained RAF strength of No. 11 Group (which was tasked to defendsoutheast England, includingLondon), butthe sudden shift in Luftwaffe concentration toward the cities allowed the RAF arespite. Also at this time, a crisis within the RAF was reaching the breakingpoint, as Air Vice-Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, commander of RAF No. 12Group (for southwest England),criticized Air Chief Marshal Dowding’s conduct of the air campaign,particularly the use of small RAF units to meet the massive German fleets. Leigh-Mallory, like many senior RAFcommanders, favored large formations (per the “Big Wing” strategy) to meet theLuftwaffe in pitched air battles. As aresult, Downing was dismissed as commander of RAF Fighter Command.

Despite No. 11 Group’s losses, the RAF over-all was nowherenear collapse, for in fact, British aircraft production, as were the otherwar-related industries, was growing. Furthermore, the air battles, fought in British territory, gave the RAFconsiderable advantages: downed RAF pilots who had parachuted to safety werequickly sent up to fight again in another plane, while RAF planes were neartheir fuel, supply, and communication lines. The Luftwaffe fought against tremendous odds: downed pilots and air crewson land faced certain capture, or worse, lynching by angry mobs, and those onthe sea, death by drowning or exposure to the elements; and Luftwaffe planesoperated far from fuel and logistical lines, e.g. the Messerschmitt Bf 109fighter plane, which functioned as a bomber escort, had only ten minutes offlying time left upon arriving in Britain, and after which it had to turn backfor Germany, leaving the bombers undefended from RAF interceptors.

On September 17, 1940, with mounting Luftwaffe losses andthe RAF clearly not verging on collapse, Hitler acknowledged before the GermanHigh Command that the German air effort in Britain would probably not succeed,and gave instructions that preparations for Operation Sea Lion be scaledback. Nevertheless, Hitler stated thatthe air attacks on Britain must continue, as ending the campaign would be anadmission of defeat, and that they were to be used as a cover for the fact thatthe German military had begun preparing (since August 1940) for its mostambitious operation of all, the conquest of the Soviet Union.

By October 1940, the “weather window” for the invasion of Britain had closed, as German planning had takeninto account that the onset of bad weather over the English Channel would greatly impede a cross-channel naval operation. On October 13, Hitler pushed back OperationSea Lion to the spring of 1941. The airoffensive continued, although by November 1940, the Luftwaffe shifted tonighttime attacks, as daylight operations were taking a heavy toll on men andaircraft. Official Britishhistoriography points to October 31, 1940 as the date that the Battle ofBritain ended, although German air attacks would continue for many more months,sometimes with great intensity particularly in October-December 1940 and evenwell into early May 1941. But by springof 1941, Hitler’s attention had invariably turned to other theaters of the war,first to the Balkans with the invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece both in April1941, and then to his greatest ambition of all, the conquest of the SovietUnion (Operation Barbarossa), set for June 1941. In the process, the bulk of the Luftwaffe wasmoved to the east, greatly easing the pressure off Britain.

(Taken from Battle of Britain – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Aftermath In theBattle of Britain, the Luftwaffe sustained some 2,600 airmen killed, wounded,or captured, and 1,700 planes destroyed or damaged (comprising 40% of theentire fleet). While German aircraftproduction continued, this considerable loss of men and aircraft meant fewerLuftwaffe resources for Operation Barbarossa. At the end of hostilities in May 1941, Hitler continued to believe that Britainwas effectively knocked out of the European war and posed no serious threat onthe continent. However, leaving Britainunconquered turned out to be one of Hitler’s great strategic mistakes. With German military resources soon directedat the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, Britainrecovered and grew militarily. Then withthe United Statesentering the war on the British side in December 1941, and in alliance with theother Allied partners, the British as part of the Allied force would return tothe continent in June 1944.

Contemporary thinking at the time attributed British successagainst the Luftwaffe to the RAF fighter pilots in their Hawker Hurricanes andSupermarine Spitfires, a depiction embodied in Churchill’s words, “Never in thefield of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few”. Only in the post-World War II period was itrevealed the critical role played by the ultra-secret Dowding system, which wasknown only to very few top-level officials in government and the military. The counter-argument is that while RAF No. 11Group had been mauled during Operation Alderangriff, suffering heavy losses inmen and planes, and many destroyed airfields and supporting infrastructures,the other RAF Groups (10, 12, and 13) remained powerful, and production ofaircraft continued.

September 6, 2024

September 6, 1965 – Indian-Pakistani War of 1965: Indian forces attack Pakistan Punjab

On September 6, 1965, Indian forces opened a new front by attacking Pakistan Punjab in the Indian-Pakistani War of 1965. The attack was launched to ease pressure on the lightly defended Indian-controlled Kashmir which was under threat from a powerful Pakistan armoured, air, and infantry offensive that had begun on September 1. Its flank threatened by the Indian counterattack, the Pakistani Army stopped its advance in Kashmir to divert forces to the new front.

Armed clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces at Rann of Kutch in April 1965 were a precursor to a full-scale war in Kashmir five months later.

Armed clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces at Rann of Kutch in April 1965 were a precursor to a full-scale war in Kashmir five months later.(Taken from Indian-Pakistani War of 1965 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background As a result of the Indian-Pakistani War of 1947 (previous article), the former Princely State of Kashmir was divided militarily under zones of occupation by the Indian Army and the Pakistani Army. Consequently, the governments of India and Pakistan established local administrations in their respective zones of control, these areas ultimately becoming de facto territories of their respective countries. However, Pakistan was determined to drive away the Indians from Kashmir and annex the whole region. As Pakistan and Kashmir had predominantly Muslim populations, the Pakistani government believed that Kashmiris detested being under Indian rule and would welcome and support an invasion by Pakistan. Furthermore, Pakistan’s government received reports that civilian protests in Kashmir indicated that Kashmiris were ready to revolt against the Indian regional government.

The Pakistani Army believed itselfsuperior to its Indian counterpart. Inearly 1965, armed clashes broke out in disputed territory in the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat State, India(Map 3). Subsequently in 1968, Pakistanwas awarded 350 square miles of the territory by the International Court ofJustice. In 1965, India was still smarting from a defeat to China in the 1962 Sino-Indian War; as a result, Pakistanbelieved that the Indian Army’s morale was low. Furthermore, Pakistanhad upgraded its Armed Forces with purchases of modern weapons from the United States, while India was yet in the midst ofmodernizing its military forces.

In the summer of 1965, Pakistan made preparations for invadingIndian-held Kashmir. To assist the operation, Pakistani commandoswould penetrate Kashmir’s major urban areas,carry out sabotage operations against military installations and publicinfrastructures, and distribute firearms to civilians in order to incite arevolt. Pakistani military plannersbelieved that Pakistanwould have greater bargaining power with the presence of a civilian uprising,in case the war went to international arbitration.

War On August 5, 1965 andthe days that followed, some 30,000 Pakistani soldiers posing as civilianscrossed the ceasefire line (the de factoborder resulting from the 1947 Indian-Pakistani War) and entered Indian-held Kashmir. ThePakistani infiltrators carried out some sabotage activities but failed toincite a general civilian uprising. TheIndian Army, tipped off by informers, crushed the operation, killing manyPakistani infiltrators and forcing others to flee back to Pakistan.

Then on August 15, the Indian forcescrossed the western ceasefire line and entered Pakistani-held Kashmir. The offensive made considerable progressuntil it was slowed at Tithwail and Pooch, upon the arrival of Pakistani Armyreinforcements. By month’s end, thebattle lines had settled (Map 4).

The Indian Army cut off all escaperoutes for the remaining Pakistani commandos in Kashmir. In order to take the pressure off the trappedcommandos, the Pakistani Army carried out an offensive aimed at Jammu. On September 1, in what became the first ofmany large tank and air battles of the war, Pakistanopened a combined armored and air attack on the town of Akhnoor. The capture of Akhnoor would cut India’scommunications and supply lines between Kashmirand the rest of the country. Furthermore, Jammu, which was India’s logistical base in Kashmir,would come under direct threat. Thesurprise and strength of the offensive caught the Indian Army off-guard,allowing the Pakistanis to win territory. However, the Pakistani Army stopped before reaching its objectives andmade a command change to the operation. The delay allowed the Indian Army to regroup and mount a strongdefense. When the Pakistani forcesrestarted their offensive, they were stopped decisively near Akhnoor.

September 5, 2024

September 5, 1957 – Cuban Revolution: Dictator Fulgencio Batista quells the Cienfuegos Mutiny

On September 5, 1957, Cuban President Fulgencio Batista violently quelled a revolt by junior Navy officers at Cienfuegos, a city located at the south central coast of the island. The revolt came after President Batista appointed certain officers to high-ranking Navy positions The leader of the mutiny also supported Fidel Castro’s ongoing rebellion to overthrow the national government (Cuban Revolution). President Batista used the army and air force to crush the Cienfuegos Mutiny, inflicting some 300 fatalities across the city and forcing some of the mutineers to flee to the Escambray Mountains, where they reorganized as another branch of the M-26-7, Fidel Castro’s insurgent organization.

( Cuban Revolution – Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

By early 1958, Castro’s insurgency was destabilizing Oriente Province, especially in the rural areaswhich had come under the control or influence of the rebels. Furthermore, four other anti-Batista armedgroups operated in the province, spreading thin the operational capability ofthe Cuban Army. Other insurgencies alsohad emerged in Camaguey and Pinar del RioProvinces, as well as in the Escambray Mountains.

In February1958, Fidel Castro sent a contingent led by hisbrother Raul to the Sierra Cristal Mountains,located in northeastern Oriente Province, where theM-26-7 subsequently opened a second front. On April 1, 1958, Fidel Castro declared total war against PresidentBatista, which was a largely propaganda move that was ignored by the otherrebel groups, but underscored the supremacy of the M-26-7 in the Cubanrevolution.

Background of theCuban Revolution In March 1952, General Fulgencio Batista seized power in Cubathrough a coup d’état. He then canceledthe elections scheduled for June 1952, where he was running for the presidencybut trailed in the polls and faced likely defeat. Having gained power, General Batistaestablished a dictatorship, suppressed the opposition, and suspended theconstitution and many civil liberties. Then in the November 1954 general elections that were boycotted by thepolitical opposition, General Batista won the presidency and thus became Cuba’s officialhead of state.

President Batista favored a close working relationship with Cuba’s wealthy elite, particularly with Americanbusinesses, which had an established, dominating presence in Cuba. Since the early twentieth century, the UnitedStates had maintained political, economic, and military control over Cuba; e.g.during the first few decades of the 1900s, U.S. forces often interveneddirectly in Cuba by quelling unrest and violence, and restoring politicalorder.

American corporations held a monopoly on the Cuban economy,dominating the production and commercial trade of the island’s main export,sugar, as well as other agricultural products, the mining and petroleumindustries, and public utilities. The United Statesnaturally entered into political, economic, and military alliances with andbacked the Cuban government; in the context of the Cold War, successive Cubangovernments after World War II were anti-communist and staunchly pro-American.

President Batista expanded the businesses of the Americanmafia in Cuba, where thesecriminal organizations built and operated racetracks, casinos, nightclubs, andhotels in Havanawith relaxed tax laws provided by the Cuban government. President Batista amassed a large personalfortune from these transactions, and Havanawas transformed into and became internationally known for its red-lightdistrict, where gambling, prostitution, and illegal drugs were rampant. President Batista’s regime was characterizedby widespread corruption, as public officials and the police benefitted frombribes from the American crime syndicates as well as from outright embezzlementof government funds.

Cubadid achieve consistently high economic growth under President Batista, but muchof the wealth was concentrated in the upper class, and a great divide existedbetween the small, wealthy elite and the masses of the urban poor and landlesspeasants. (Cuban society also containeda relatively dynamic middle class that included doctors, lawyers, and manyother working professionals.)

President Batista was extremely unpopular among the generalpopulation, because he had gained power through force and made unequal economicpolicies. As a result, Havana(Cuba’scapital) seethed with discontent, with street demonstrations, protests, andriots occurring frequently. In response,President Batista deployed security forces to suppress dissenting elements,particularly those that advocated Marxist ideology. The government’s secret police regularlycarried out extrajudicial executions and forced disappearances, as well asarbitrary arrests, detentions, and tortures. Some 20,000 persons were killed or disappeared during the Batistaregime.

In 1953, a young lawyer and former student leader namedFidel Castro emerged to lead what ultimately would be the most serious challengeto President Batista. Castro previouslyhad taken part in the aborted overthrow of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo and in the 1948 civildisturbance (known as “Bogotazo”) in Bogota, Colombia before completing his law studies atthe University of Havana. Castro had run as an independent for Congressin the 1952 elections that were cancelled because of Batista’s coup. Castro was infuriated and began makingpreparations to overthrow what he declared was the illegitimate Batista regimethat had seized power from a democratically elected government. Fidel organized an armed insurgent group,“The Movement”, whose aim was to overthrow President Batista. At its peak, “The Movement” would comprise1,200 members in its civilian and military wings.

September 4, 2024

September 4, 1919 – Turkish War of Independence: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk leads an assembly of Turkish nationalists at the Sivas Congress

On September 4, 1919, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and the Turkish National Movement met at Sivas in central-eastern Turkey to formulate policy for the preservation of unity, independence, and territorial integrity of the Turkish state. The week-long assembly (September 4-11, 1919) came in the heels of the preparatory Erzurum Congress. At this time, World War I had just ended and the defeated Ottoman Empire was supine and essentially defunct, and partitioned under military occupation by the Allied Powers: French, British, Italians, and Greeks.

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres(Taken from Turkish War of Independence in Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

As a result of this circular, Turkish nationalists mettwice: at the Erzerum Congress (July-August 1991) by regional leaders of theeastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September 1919) of nationalistleaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from thesemeetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth the guidelines for the Turkishstate, including what constituted the “homeland of the Turkish nation”, andthat the “country should be independent and free, all restrictions onpolitical, judicial, and financial developments will be removed”. The “Representative Committee” was theprecursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3, 1920 asthe Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara(in central Anatolia), founded and led byKemal.

Sykes-Picot Agreement

Sykes-Picot AgreementBackground of theTurkish War of Independence On October 30,1918, the Ottoman Empire ended its involvementin World War I by signing the Armistice of Mudros. During the war, the Ottoman government hadfought as one of the Central Powers (in alliance with Germany, Austria-Hungary,and Bulgaria),but in 1917 and 1918, it suffered many devastating defeats. Then with the failure of the Germans’ 1918“Spring Offensive” in Western Europe, the Anatolian heartland of the Ottoman Empire became vulnerable to an invasion, forcingOttoman capitulation.

The victorious Allied Powers in Europe (Britain, France,and Italy) took steps tocarry out their many secret pre-war and war-time agreements regarding thedisposition of the Ottoman Empire. Another Allied power, Russia, also was a party to some ofthese agreements, but it had been forced out of the war in 1914 andconsequently was not involved in the post-war negotiations.

As a first measure and provided by the terms of surrender,the French and British naval fleets seized control of the Turkish Straits(Dardanelles and Bosporus) on November 12-13, 1913, and landed troops inConstantinople, the Ottoman Empire’s capital.

During World War I, British forces gained possession of muchof the Ottoman Empire’s colonies in the Middle East, collectively called“Greater Syria”, a vast territory covering Mesopotamia (Iraq), the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Palestine. When the war ended, most of the ArabianPeninsula gained independence under British sponsorship, including the Kingdom of Yemenand later the Kingdom of Nejd and Hejaz, the precursor of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The most significant war-time treaty to be implemented inthe Middle East was the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, where Britain and Francedrew up a plan to partition between them most of the remaining Ottomanpossessions, i.e. Syria and Lebanon to France, and Mesopotamia and Palestine toBritain*. As a result, following war’send, Britain and France took control of their respectivepreviously agreed territories in the Middle East. These annexations subsequently werelegitimized as mandates by the newly formed League of Nations: i.e. the 1923French Mandate for Syria andthe Lebanon, and the 1923British Mandate for Palestine. British control of Mesopotamia was formalizedby the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1922, which also established the Kingdom of Iraq.

The Allies also had drawn up a partition plan for Anatolia,the Turkish heartland of the Ottoman Empire. In this plan, Constantinople and the Turkish Straits were designated as a neutralzone under joint Allied administrations, with separate British, French, andItalian zones of occupations. SouthwestAnatolia was allocated to Italy,the southeast (centered on Cilicia) to France,and a section of the northeast to Armenia. Greece,a late-comer in World War I on the Allied side, was promised the historicHellenic region around Smyrna, as well as Eastern Thrace.

With these proposed changes, a much smaller Ottoman statewould consist of central Anatolia up to the Black Sea, but no coastal outlet inthe Mediterranean Sea. The Allies subsequently incorporated thesestipulations in the 1920 Treaty of Sevres (Map 8), an agreement aimed atlegitimizing their annexations/occupations of Ottoman territories.

The Allies wanted a breakup of the Ottomans’ centralizedstate, to be replaced by a decentralized federal form of government. In Constantinople,the national government led by the Sultan and Grand Vizier (Prime Minister)were resigned to these political and territorial changes. However, Turkish nationalists, representing apolitical and ideological movement that became powerful in the early twentiethcentury, opposed the Allied impositions on Anatolia,perceiving them to be a deliberate dismembering of the Turkish traditionalhomeland. As a result of the Alliedoccupation, many small Turkish nationalist armed resistance groups began toorganize all across Anatolia.

Rise of the Turkish Independence Movement Under thearmistice agreement, the Ottoman government was required to disarm anddemobilize its armed forces. On April30, 1919, Mustafa Kemal, a general in the Ottoman Army, was appointed as theInspector-General of the Ottoman Ninth Army in Anatolia,with the task of demobilizing the remaining forces in the interior. Kemal was a nationalist who opposed theAllied occupation, and upon arriving in Samsunon May 19, 1919, he and other like-minded colleagues set up what became theTurkish Nationalist Movement.

Contact was made with other nationalist politicians andmilitary officers, and alliances were formed with other nationalistorganizations in Anatolia. Military units that were not yet demobilized,as well as the various armed bands and militias, were instructed to resist the occupationforces. These various nationalist groupsultimately would merge to form the nationalists’ “National Army” in the comingwar. Weapons and ammunitions werestockpiled, and those previously surrendered were secretly taken back andturned over to the nationalists.

On June 21, 1919, Kemal issued the Amasya Circular, whichdeclared among other things, that the unity and independence of the Turkishstate were in danger, that the Ottoman government was incapable of defendingthe country, and that a national effort was needed to secure the state’sintegrity. As a result of this circular,Turkish nationalists met twice: at the Erzerum Congress (July-August 1991) byregional leaders of the eastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September1919) of nationalist leaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from thesemeetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth the guidelines for the Turkishstate, including what constituted the “homeland of the Turkish nation”, andthat the “country should be independent and free, all restrictions onpolitical, judicial, and financial developments will be removed”. The “Representative Committee” was theprecursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3, 1920 asthe Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara(in central Anatolia), founded and led byKemal.

Kemal and his Representative Committee “government”challenged the continued legitimacy of the national government, declaring that Constantinople was ruled by the Allied Powers from whomthe Sultan had to be liberated. However,the Sultan condemned Kemal and the nationalists, since both the lattereffectively had established a second government that was a rival to that in Constantinople.

In July 1919, Kemal received an order from the nationalauthorities to return to Constantinople. Fearing for his safety, he remained in Ankara; consequently, heceased all official duties with the Ottoman Army. The Ottoman government then laid down treasoncharges against Kemal and other nationalist leaders; tried in absentia, he wasdeclared guilty on May 11, 1920 and sentenced to death.

Initially, British authorities played down the threat posedby the Turkish nationalists. Then whenthe Ottoman parliament in Constantinopledeclared its support for the nationalists’ National Pact and the integrity ofthe Turkish state, the British violently closed down the legislature, an actionthat inflicted many civilian casualties. The next month, the Sultan affirmed the dissolution of the Ottomanparliament.

Many parliamentarians were arrested, but many others escapedcapture and fled to Ankarato join the nationalists. On April 23,1920, a new parliament called the Grand National Assembly convened in Ankara, which electedKemal as its first president.

British authorities soon realized that the nationalistmovement threatened the Allied plans on the Ottoman Empire. From civilian volunteers and units of theSultan’s Caliphate Army, the British organized a militia, which was tasked todefeat the nationalist forces in Anatolia. Clashes soon broke out, with the most intensetaking place in June 1920 in and around Izmit, where Ottoman and British forcesdefeated the nationalists. Defectionswere widespread among the Sultan’s forces, however, forcing the British todisband the militia.

The British then considered using their own troops, butbacked down knowing that the British public would oppose Britain being involved in anotherwar, especially one coming right after World War I. The British soon found another ally to fightthe war against the nationalists – Greece. On June 10, 1920, the Allies presented theTreaty of Sevres to the Sultan. Thetreaty was signed by the Ottoman government but was not ratified, since waralready had broken out.

In the coming war, Kemal crucially gained the support of thenewly established Soviet Union, particularly in the Caucasuswhere for centuries, the Russians and Ottomans had fought for domination. This Soviet-Turkish alliance resulted fromboth sides’ condemnation of the Allied intervention in their local affairs,i.e. the British and French enforcing the Treaty of Sevres on the Ottoman Empire, and the Allies’ open support foranti-Bolshevik forces in the Russian Civil War.

War Turkish nationalists fought in three fronts: in the eastagainst Armenia, in thesouth against France and the French Armenian Legion, and in the west against Greece, which was backed by Britain.

September 3, 2024

September 3, 1939 – World War II: Britain and France blockade Germany’s coastline, starting the Battle of the Atlantic

(Excerpts from Battle of the Atlantic (Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe))

On September 1, 1939, Germanyinvaded Poland; two dayslater, September 3, Britainand France declared war on Germany,starting World War II. On September 4,1939, Britainimposed a naval blockade of German ports. Under the newly established British Contraband Control Service andFrench Blockade Ministry, the British Royal Navy and French Navy (Marinenationale) under over-all British command, imposed a blockade enforcementsystem where all ships passing European trade routes were required to stop forinspection at designated British ports (later expanded to include other Britishcolonial ports along merchant routes in the Mediterranean Sea and IndianOcean). The ships’ cargoes were examined,and items found in a broad list of designated contraband materials, whichincluded ammunitions, explosives, and the like, but also even foodstuffs,animal feed, and clothing, were subject to seizure. The Allies intended these measures to force Germany,which was deficient in natural resources and heavily dependent on importationof food and raw materials for its people, civilian industries, and warcapability, to enter into peace negotiations, thus bringing the war to an end.

Instead, Germanyimposed its own naval blockade of Britain which, as an island nation,was also heavily dependent on importation of commodities in order to survive,as well as to continue the war. Germany’s aim was to starve Britain intosubmission. The German Navy’s attempt tostop the flow of materials to Britainparticularly from North America through the Atlantic Ocean, and the Britishefforts to foil the Germans constitute what is known as the Battleof the Atlantic.

By the time of the outbreak of World War II, the ambitiousexpansion program of the Kriegsmarine (the German Navy) under Plan Z aimed atachieving naval equality with the British Navy (the world’s largest fleet), wasfar from complete, and the small German fleet (by comparison) simply could notengage in open battle either the British or French fleets, the latter twohaving much larger navies.

Instead, early in the war, the Kriegsmarine initiated astrategy of commerce raiding, where German surface ships (battleships,cruisers, destroyers, etc.) and submarines, which were called U-boats (from theGerman: Unterseeboot; “underseaboat”), were sent to the Atlantic Ocean to attack Allied and neutral-nationmerchant vessels bound for Britain. TheGermans also used a number of armed merchant vessels, which were disguised asneutral or Allied ships but manned by German Navy personnel, for commerceraiding. As well, later in the war,long-range Luftwaffe planes, particularly the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, wereused for reconnaissance and attack missions.

The German heavy cruisers Deutschland and Admiral GrafSpee, already in the Atlantic Ocean at theoutbreak of war, sank several Allied merchant ships. The Allies organized several hunting groupsto locate these German ships, so straining their resources as the British andFrench allocated three battle cruisers, three aircraft carriers, fifteencruisers, and many auxiliary ships to scour the Atlantic. But in December 1939, the Graf Spee was caught and trapped nearthe River Plate (Rio de la Plata), off the South American coast, and scuttledby its crew near Montevideo, Uruguay.

Despite this success, the early hunting-group strategyproved counter-productive, as the Allies then possessed inadequatetechnological resources to locate U-boats, whose strength lay in avoidingdetection by submerging underwater and remaining there until the dangerpassed. The U-boat’s other main assetwas stealth, and the first naval casualty of the war, the British ocean liner, SS Athenia, was attacked and sunk by aU-boat (which it mistook for a British warship) on September 3, 1939, with 128lives lost. Also in September 1939 andjust a few days apart, two British aircraft carriers, the HMS Ark Royal and HMSCourageous, were both attacked by a U-boat, with the former narrowly beinghit by torpedoes, while the latter was hit and sunk. Then in October 1939, another U-boatpenetrated undetected near Scapa Flow, themain British naval base, attacking and sinking the battleship, the HMS Royal Oak.

At the start of the war, the British military washard-pressed on how to deal with the U-boat threat. During the interwar period, prevailing navalthought and budgetary resources, both Allied and German alike, focused onsurface ships, and the belief that battleships would play the dominant role innaval warfare in a future war. GermanU-boats had proved highly effective in World War I, causing heavy losses onmerchant shipping that nearly forced Britain out of the war, before theBritish introduced the convoy system that turned fortunes around.

However, the British Navy’s implementing the ASDIC system(acronym for “Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee”; otherwiseknown as SONAR), which could detect the presence of submerged submarines,appeared to have solved the U-boat threat. Naval tests showed that once detected by ASDIC, the submarine could thenbe destroyed by two destroyers launching depth charges overboard continuouslyin a long diamond pattern around the trapped vessel. The British concept was that the U-boatscould operate only in coastal waters to threaten harbor shipping, as they haddone in World War I, and these tests were conducted under daylight and calmweather conditions. But by the outbreakof World War II, German submarine technology had rapidly advanced, and werecontinuing so, that U-boats were able to reach farther out into the AtlanticOcean, eventually ranging as far as the American eastern seacoast, and alsowere able to submerge to greater depths beyond the capacity of depthcharges. These factors would weigh heavilyin the early stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

September 2, 2024

September 2, 1939 – World War II: Germany annexes Danzig

On September 2, 1939 one day after launching its invasion of Poland, Germany abolished the Free City of Danzig and annexed the territory into the Third Reich. The Free City of Danzig (present-day Gdansk, Poland) had been established in November 1920 by the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. The Free City comprised territory detached from pre-World War I Germany, including the Baltic port of Danzig and surrounding areas that included some 200 towns and villages. The Free City of Danzig was established to be neither German nor Polish territory, but a semi-autonomous entity administered by the League of Nations to allow newly independent Poland access to the Baltic Sea (the so-called “Polish Corridor”). As such, Poland was given rights to communication, railways, and port facilities in the Free City. Ethnic Germans comprised 98% of the Free City’s population.

(Taken from German Invasion of Poland – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background At the end of World War I, the Allies reconstituted Poland as a sovereign nation, incorporating into the new state portions of the eastern German territories of Pomerania and Silesia, which contained majority Polish populations. In the 1920s, the German Weimar Republic sought to restore to Germany all its lost territories, but was restrained by certain stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, which had been imposed on Germany after World War I. Polish Pomerania was known worldwide as the “Polish Corridor”, as it allowed Poland access to international waters through the Baltic Sea. The German city of Danzig in East Prussia, as well as nearby areas, also was detached from Germany, and renamed the “Free City of Danzig”, administered by the League of Nations, but whose port, customs, and public infrastructures were controlled by Poland.

In 1933, Hitler came to power and implemented Germany’smassive rearmament program, and later began to pursue his irredentist ambitionsin earnest. Previously in January 1934,Nazi Germany and Poland hadsigned a ten-year non-aggression pact, where the German government recognizedthe territorial integrity of the Polish state, which included the Germanregions that had been ceded to Poland. But by the late 1930s, the now militarilypowerful Germanywas actively pushing to redefine the German-Polish border.

In October 1938, Germanyproposed to Poland renewingtheir non-aggression treaty, but subject to two conditions: that Danzig berestored to Germany and thatGermany be allowed to buildroad and railway lines through the Polish Corridor to connect Germany proper and East Prussia. Poland refused, and in April 1939,Hitler abolished the non-aggression pact. To Poland, Hitler wasusing the same aggressive tactics that he had used against Czechoslovakia, and that if it yielded to theGerman demands on Danzig and the Polish Corridor, ultimately the rest of Poland would be swallowed up by Germany.

Meanwhile, Britainand France, which hadpursued appeasement toward Hitler, had become wary after the German occupationof the rest of Czechoslovakia,which had a non-ethnic German majority population, which was in contrast towhat Hitler had said that he only wanted returned those German-populatedterritories. Britainand France were nowdetermined to resist Germanydiplomatically and resolve the crisis through firm negotiations. On March 31, 1939, Britainand Franceannounced that they would “guarantee Polish independence” in case of foreignaggression. Since 1921, as per the Franco-PolishMilitary Alliance, France had pledged military assistance to Poland if thatlatter was attacked.

In fact, Hitler’s intentions on Poland was not only thereturn of lost German territories, but the elimination of the Polish state andannexation of Poland as part of Lebensraum (“living space”), German expansioninto Eastern Europe and Russia. Lebensraum called for the eradication of the native populations in theseconquered areas. For Polandspecifically, on August 22, 1939 in the lead-up to the German invasion, Hitlerhad said that “the object of the war is … to kill without pity or mercy allmen, women, and children of Polish descent or language. Only in this way can we obtain the livingspace we need.” In April 1939, Hitlerinstructed the German military High Command to begin preparations for aninvasion of Poland,to be launched later in the summer. ByMay 1939, the German military had drawn up the invasion plan.

In May 1939, Britainand France held high-leveltalks with the Soviet Union regarding forming a tripartite military allianceagainst Germany, especiallyin light of the possible German invasion of Poland. These talks stalled, because Poland refused to allow Soviet forces into itsterritory in case Germanyattacked. Unbeknown to Britain and France,the Soviet Union and Germanywere also conducting (secret) separate talks regarding bilateral political,military, and economic concerns, which on August 23, 1939, led to the signingof a non-aggression treaty. This treaty,which was broadcast to the world and widely known as the Molotov RibbentropPact (named after Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German ForeignMinister Joachim von Ribbentrop), brought a radical shift to the European powerbalance, as Germany was now free to invade Poland without fear of Sovietreprisal. The pact also included asecret protocol where Poland,Finland, Estonia, Latvia,Lithuania, and Romania weredivided into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

One day earlier, August 22, with the non-aggression treatyvirtually assured, Hitler set the invasion date of Poland for August 26, 1939. On August 25, Hitler told the Britishambassador that Britain mustagree to the German demands on Poland,as the non-aggression pact freed Germany from facing a two-front warwith major powers. But on that same day,Britain and Poland signed a mutual defense pact, whichcontained a secret clause where the British promised military assistance if Poland was attacked by Germany. This agreement, as well as British overturesthat Britain and Poland were willing to restart the stalled talkswith Germany,forced Hitler to abort the invasion set for the next day.

The Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) stood down, except forsome units that did not receive the new stop order and crossed into Poland,skirmishing with the Poles. These Germanunits soon withdrew back across the border, but the Polish High Command,informed through intelligence reports of massive German build-up at the border,was unaware that the border skirmishes were part of an aborted German invasion.

German negotiations with Britainand Francecontinued, but they failed to make progress. Poland had refused tonegotiate on the basis of ceding territory, and its determination wasstrengthened by the military guarantees of the Western Powers, particularly inthat if the Germans invaded, the British and French would attack from the west,and Germanywould be confronted with a two-front war.

On August 29, 1939, Germanysent Poland a set ofproposals for negotiations, which included two points: that Danzig be returnedto Germany and that aplebiscite be held in the Polish Corridor to determine whether the territoryshould remain with Poland orbe returned to Germany. In the latter, Poles who were born or hadsettled in the Corridor since 1919 could not vote, while Germans born there butnot living there could vote. Germanydemanded that negotiations were subject to a Polish official with signingpowers arriving by the following day, August 30.

Britaindeemed that the German proposal was an ultimatum to Poland, and tried but failed toconvince the Polish government to negotiate. On August 30, the German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop presented theBritish ambassador with a 16-point proposal for negotiations, but refused thelatter’s request that a copy be sent to the Polish government, as no Polishrepresentative had arrived by the set date. The next day, August 31, the Polish Ambassador Jozef Lipski conferredwith Ribbentrop, but as Lipski had no signing powers, the talks did notproceed. Later that day, Hitlerannounced that the German-Polish talks had ended because of Poland’srefusal to negotiate. He then orderedthe German High Command to proceed with the invasion of Poland for thenext day, September 1, 1939.

September 1, 2024

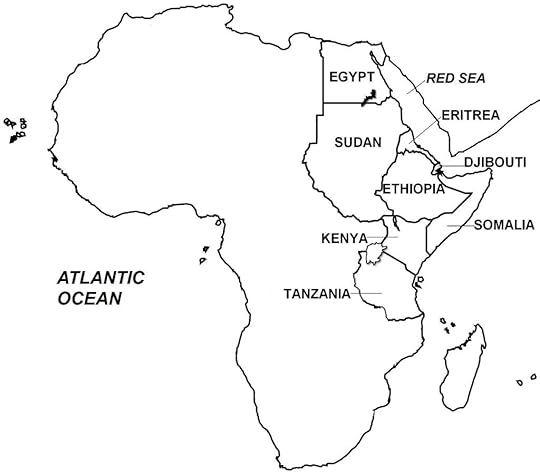

September 1, 1961 – Eritrean War of Independence: Eritrean nationalists attack Ethiopian police posts

On September 1, 1961, insurgents of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) stormed a number of police posts in western Eritrea, marking the start of the Eritrean War of Independence, a protracted conflict that would last three decades. The insurgents subsequently carried out more attacks against security forces. In the period that followed, the ELF gained local support in its areas of operations in the rural Muslim-populated rural northern and western regions of Eritrea and increased its numbers with the inflow of many new recruits. The rebels also increased their frequency of attacks against police targets, primarily to capture much-needed weapons. By June 1962, the ELF had some 500 fighters, which included some police defectors who took along their weapons and ammunitions. At this time, Muslims formed the vast majority of the ELF, which also advocated a pro-Muslim, pro-Arab ideological and religious struggle against the predominantly Christian Ethiopia. Also for this reason, the ELF gained some military and financial support from a number of Muslim countries, including Syria, Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan.

On May 24, 1991, Eritreagained its independence from Ethiopiafollowing a 30-year armed revolution. Ethiopiahad annexed Eritreaas a province in November 1962, inciting Eritrean nationalists to launch arebellion. Following the war, as Eritrea was still legally bound as part ofEthiopia, in early July 1991, at a conference held in Addis Ababa, an interimEthiopian government was formed, which stated that Eritreans had the right todetermine their own political future, i.e. to remain with or secede from Ethiopia.

Then in a UN-monitored referendum held in April 23 and 25,1993, Eritreans voted overwhelmingly (99.8%) for independence; two days later(April 27), Eritreadeclared its independence. In May 1993, the new country was admitted as amember of the UN.

Eritrea, Ethiopia and nearby countries

Eritrea, Ethiopia and nearby countries(Taken from Eritrean War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background InSeptember 1948, a special body called the Inquiry Commission, which was set upby the Allied Powers (Britain,France, Soviet Union, and United States),failed to establish a future course for Eritrea and referred the matter tothe United Nations (UN). The main obstacle to granting Eritrea its independence was that for much ofits history, Eritreawas not a single political sovereign entity but had been a part of andsubordinate to a greater colonial power, and as such, was deemed incapable ofsurviving on its own as a fully independent state. Furthermore, variouscountries put forth competing claims to Eritrea. Italywanted Eritrea returned, tobe governed for a pre-set period until the territory’s independence, anarrangement that was similar to that of Italian Somaliland.The Arab countries of the Middle East pressed for self-determination of Eritrea’s large Muslim population, and as such,called for Eritreato be granted its independence. Britain,as the current administrative power, wanted to partition Eritrea, with the Christian-population regionsto be incorporated into Ethiopiaand the Muslim regions to be assimilated into Sudan. Emperor Haile Selassie, theEthiopian monarch, also claimed ownership of Eritrea, citing historical and culturalties, as well as the need for Ethiopia to have access to the sea through theRed Sea (Ethiopia had been landlocked after Italy established Eritrea).

Ultimately, the United Statesinfluenced the future course for Eritrea. The U.S. government saw Eritreain the regional balance of power in Cold War politics: an independent but weak Eritrea could potentially fall to communist(Soviet) domination, which would destabilize the vital oil-rich Middle East. Unbeknown to the general public at the time,a U.S. diplomatic cable fromEthiopia to the U.S. StateDepartment in August 1949 stated that British officials in Eritrea believed that as much as75% of the local population desired independence.

In February 1950, a UN commission sent to Eritrea todetermine the local people’s political aspirations submitted its findings tothe United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In December 1950, the UNGA, whichwas strongly influenced by U.S.wishes, released Resolution 390A (V) that called for establishing a loose federationbetween Ethiopia and Eritrea to be facilitated by Britain and to be realized no laterthan September 15, 1952. The UN plan, which subsequently was implemented,allowed Eritreabroad autonomy in controlling its internal affairs, including local administrative,police, and fiscal and taxation functions. The Ethiopian-Eritrean Federationwould affirm the sovereignty of the Ethiopian monarch whose government wouldexert jurisdiction over Eritrea’sforeign affairs, including military defense, national finance, and transportation.

In March 1952, under British initiative, Eritrea electeda 68-seat Representative Assembly, a legislature composed equally of Christiansand Muslim members, which subsequently adopted a constitution proposed by theUN. Just days before the September 1952 deadline for federation, the Ethiopiangovernment ratified the Eritrean constitution and upheld Eritrea’s Representative Assemblyas the renamed Eritrean Assembly. On September 15, 1952, the Ethiopian-EritreanFederation was established, and Britainturned over administration to the new authorities, and withdrew from Eritrea.

However, Emperor Haile Selassie was determined to bring Eritrea under Ethiopia’s full authority. Eritrea’shead of government (called Chief Executive who was elected by the EritreanAssembly) was forced to resign, and successors to the post were appointed bythe Ethiopian emperor. Ethiopians were appointed to many high-level Eritreangovernment posts. Many Eritrean political parties were banned and press censorshipwas imposed. Amharic, Ethiopia’sofficial language, was imposed, while Arabic and Tigrayan, Eritrea’s main languages, werereplaced with Amharic as the medium for education. Many local businesses weremoved to Ethiopia, whilelocal tax revenues were sent to Ethiopia.By the early 1960s, Eritrea’sautonomy status virtually had ceased to exist. In November 1962, the EritreanAssembly, under strong pressure from Emperor Haile Selassie, dissolved theEthiopian-Eritrean Federation and voted to incorporate Eritrea as Ethiopia’s14th province.

Eritreans were outraged by these developments. Civiliandissent in the form of rallies and demonstrations broke out, and was dealt withharshly by Ethiopia,causing scores of deaths and injuries among protesters in confrontations withsecurity forces. Opposition leaders, particularly those calling forindependence, were suppressed, forcing many to flee into exile abroad; scoresof their supporters also were jailed. In April 1958, the first organizedresistance to Ethiopian rule emerged with the formation of the clandestineEritrean Liberation Movement (ELM), consisting originally of Eritrean exiles inSudan.At its peak in Eritrea, the ELM had some 40,000 members who organized in cellsof 7 people and carried out a campaign of destabilization, including engagingin some militant actions such as assassinating government officials, aimed atforcing the Ethiopian government to reverse some of its centralizing policiesthat were undercutting Eritrea’s autonomous status under the federatedarrangement with Ethiopia. By 1962, the government’s anti-dissident campaignshad weakened the ELM, although the militant group continued to exist, albeitwith limited success. Also by 1962, another Eritrean nationalist organization,the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), had emerged, having been organized in July1960 by Eritrean exiles in Cairo, Egypt which in contrast to the ELM, had asits objective the use of armed force to achieve Eritrean’s independence.

In its early years, the ELF leadership, called the “SupremeCouncil”, operated out of Cairoto more effectively spread its political goals to the international communityand to lobby and secure military support from foreign donors.

August 31, 2024

August 31, 1939 – World War II: German saboteurs seize the Gleiwitz radio station and air anti-German propaganda, giving Germany a pretext to invade Poland

In the lead-up to the war, German operatives launched aseries of sabotage operations in German territory in the guise that these werecommitted by Poles, in order to give Germanya pretext to invade Poland. These actions, implemented under OperationHimmler, targeted railway stations, customs houses, communication lines, etc. As part of Operation Himmler, on the night ofAugust 31, 1939, German saboteurs wearing Polish uniforms seized the Gleiwitzradio station in Silesia, Germany, andaired a short anti-German message in Polish. This and other supposed Polish provocations were used by Hitler tolaunch what he called a “defensive war” against Poland, stating that “the series ofborder violations, which are unbearable to a great power, prove that the Polesno longer are willing to respect the German frontier.”

German invasion of Poland

German invasion of Poland(Taken from German Invasion of Poland – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background At the end of World War I, the Allies reconstituted Poland as a sovereign nation, incorporating into the new state portions of the eastern German territories of Pomerania and Silesia, which contained majority Polish populations. In the 1920s, the German Weimar Republic sought to restore to Germany all its lost territories, but was restrained by certain stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, which had been imposed on Germany after World War I. Polish Pomerania was known worldwide as the “Polish Corridor”, as it allowed Poland access to international waters through the Baltic Sea. The German city of Danzig in East Prussia, as well as nearby areas, also was detached from Germany, and renamed the “Free City of Danzig”, administered by the League of Nations, but whose port, customs, and public infrastructures were controlled by Poland.

In 1933, Hitler came to power and implemented Germany’smassive rearmament program, and later began to pursue his irredentist ambitionsin earnest. Previously in January 1934,Nazi Germany and Poland hadsigned a ten-year non-aggression pact, where the German government recognizedthe territorial integrity of the Polish state, which included the Germanregions that had been ceded to Poland. But by the late 1930s, the now militarilypowerful Germanywas actively pushing to redefine the German-Polish border.

In October 1938, Germanyproposed to Poland renewingtheir non-aggression treaty, but subject to two conditions: that Danzig berestored to Germany and thatGermany be allowed to buildroad and railway lines through the Polish Corridor to connect Germany proper and East Prussia. Poland refused, and in April 1939,Hitler abolished the non-aggression pact. To Poland, Hitler wasusing the same aggressive tactics that he had used against Czechoslovakia, and that if it yielded to theGerman demands on Danzig and the Polish Corridor, ultimately the rest of Poland would be swallowed up by Germany.

Meanwhile, Britainand France, which hadpursued appeasement toward Hitler, had become wary after the German occupationof the rest of Czechoslovakia,which had a non-ethnic German majority population, which was in contrast towhat Hitler had said that he only wanted returned those German-populatedterritories. Britainand France were nowdetermined to resist Germanydiplomatically and resolve the crisis through firm negotiations. On March 31, 1939, Britainand Franceannounced that they would “guarantee Polish independence” in case of foreignaggression. Since 1921, as per theFranco-Polish Military Alliance, France had pledged military assistance to Poland if thatlatter was attacked.

In fact, Hitler’s intentions on Poland was not only thereturn of lost German territories, but the elimination of the Polish state andannexation of Poland as part of Lebensraum (“living space”), German expansioninto Eastern Europe and Russia. Lebensraum called for the eradication of the native populations in theseconquered areas. For Polandspecifically, on August 22, 1939 in the lead-up to the German invasion, Hitlerhad said that “the object of the war is … to kill without pity or mercy allmen, women, and children of Polish descent or language. Only in this way can we obtain the livingspace we need.” In April 1939, Hitlerinstructed the German military High Command to begin preparations for aninvasion of Poland,to be launched later in the summer. ByMay 1939, the German military had drawn up the invasion plan.

In May 1939, Britainand France held high-leveltalks with the Soviet Union regarding forming a tripartite military allianceagainst Germany, especiallyin light of the possible German invasion of Poland. These talks stalled, because Poland refused to allow Soviet forces into itsterritory in case Germanyattacked. Unbeknown to Britain and France,the Soviet Union and Germanywere also conducting (secret) separate talks regarding bilateral political,military, and economic concerns, which on August 23, 1939, led to the signingof a non-aggression treaty. This treaty,which was broadcast to the world and widely known as the Molotov RibbentropPact (named after Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German ForeignMinister Joachim von Ribbentrop), brought a radical shift to the European powerbalance, as Germany was now free to invade Poland without fear of Sovietreprisal. The pact also included asecret protocol where Poland,Finland, Estonia, Latvia,Lithuania, and Romania weredivided into German and Soviet spheres of influence.

One day earlier, August 22, with the non-aggression treatyvirtually assured, Hitler set the invasion date of Poland for August 26, 1939. On August 25, Hitler told the Britishambassador that Britain mustagree to the German demands on Poland,as the non-aggression pact freed Germany from facing a two-front warwith major powers. But on that same day,Britain and Poland signed a mutual defense pact, whichcontained a secret clause where the British promised military assistance if Poland was attacked by Germany. This agreement, as well as British overturesthat Britain and Poland were willing to restart the stalled talkswith Germany,forced Hitler to abort the invasion set for the next day.

The Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces) stood down, except forsome units that did not receive the new stop order and crossed into Poland,skirmishing with the Poles. These Germanunits soon withdrew back across the border, but the Polish High Command,informed through intelligence reports of massive German build-up at the border,was unaware that the border skirmishes were part of an aborted German invasion.

German negotiations with Britainand Francecontinued, but they failed to make progress. Poland had refused tonegotiate on the basis of ceding territory, and its determination wasstrengthened by the military guarantees of the Western Powers, particularly inthat if the Germans invaded, the British and French would attack from the west,and Germanywould be confronted with a two-front war.

On August 29, 1939, Germanysent Poland a set ofproposals for negotiations, which included two points: that Danzig be returnedto Germany and that aplebiscite be held in the Polish Corridor to determine whether the territoryshould remain with Poland orbe returned to Germany. In the latter, Poles who were born or hadsettled in the Corridor since 1919 could not vote, while Germans born there butnot living there could vote. Germanydemanded that negotiations were subject to a Polish official with signingpowers arriving by the following day, August 30.

Britaindeemed that the German proposal was an ultimatum to Poland, and tried but failed toconvince the Polish government to negotiate. On August 30, the German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop presented theBritish ambassador with a 16-point proposal for negotiations, but refused thelatter’s request that a copy be sent to the Polish government, as no Polishrepresentative had arrived by the set date. The next day, August 31, the Polish Ambassador Jozef Lipski conferredwith Ribbentrop, but as Lipski had no signing powers, the talks did notproceed. Later that day, Hitlerannounced that the German-Polish talks had ended because of Poland’srefusal to negotiate. He then orderedthe German High Command to proceed with the invasion of Poland for thenext day, September 1, 1939.

August 30, 2024

August 30, 1998 – Second Congo War: The Congolese Army and its Angolan and Zimbabwean allies recapture Matadi from Rwandan forces

On August 30, 1998, forces of the Democratic Republic ofCongo (DRC), together with their Angolan and Zimbabwean allies, recaptured thetown of Matadifrom Rwandan forces and the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD) militia duringthe ongoing Second Congo War.

(Taken from Second Congo War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

By this time, Angolan forces also had come to the aid of Democratic Republic of the Cong (DRC) President Kabila’s beleaguered regime, entering through the Angolan province of Cabinda. The Angolans took control of the Congo’s western region, including liberating the towns of Matadi and Kitona, and moved eastward to meet up with the Zimbabwean Army in Kinshasa. More Zimbabwean forces began pouring in via Zambia into southern Congo, with the aim of securing Mbuji-Mayi, a diamond-rich mining town in Kasai-Oriental Province. With military forces from Namibia deploying in the western Congo and those from Chad entering through the north, both in support of the Congolese government, and Burundi, backing the invaders, the conflict threatened to expand into a full-blown multinational war (in fact, the war has been called “Africa’s World War”).

With Kinshasasecure by early September, the Angola-Zimbabwe-Congo coalition made plans tolaunch an offensive into rebel-held territories further east. Rwandaand Ugandahad recruited extensively – some 100,000 new soldiers were brought to thefrontlines, greatly overmatching in numbers the combined Angolan-Zimbabweanforces (the latter, however, consisted mainly of elite combat units). Both sides of the conflict also increased thestrength of their battle tanks, armored vehicles, artillery, and warplanes.

In the following months, a number of indecisive battles tookplace, as each side tried to expand its control in northern Katanga Provinceand in central Congo. In northern Congo,the Ugandan Army organized the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, a proxy militia, to serve as its advanceforce in its offensive into northeast Congo.

Background of theSecond Congo War TheFirst Congo War (previous article) ended when Laurent-Désiré Kabila took overpower in Zaire. He formed a new government and named himselfthe country’s president. He renamed thecountry the “Democratic Republic of the Congo”. President Kabila faced enormous problems: thecountry’s infrastructure was in ruins partly because of the war but mainlybecause of neglect by the previous regime; the economy was devastated; and mostof the people lived in poverty.

And these were the least of President Kabila’sproblems. He was most concerned abouthis tenuous hold on power. He had mergedhis rebel forces with the Rwandan Army, which produced tensions between the twoformer enemies. Furthermore, somemilitary officers remained loyal to ex-President Mobutu Sese Seko, the deposedtyrant.

To consolidate power, President Kabila set up anauthoritarian regime, centralized power, and appointed relatives and friends totop government positions. Hisadministration was accused of nepotism, abuse of power, and corruption, andPresident Kabila’s critics drew similarities between his government and theformer regime – implying that nothing had changed.

More crucial image-wise for President Kabila was theubiquitous presence in the Congoof foreign troops, particularly those from Rwandaand Uganda;these countries had helped him win the First Congo War. The Congolese people perceived the foreignarmies as holding real power in the country, with President Kabila merelyacting as a figurehead. For this reason,on July 14, 1998, President Kabila sacked his Armed Forces chief of staff, aRwandan, an act that began a chain of events that led to the Second Congo War.

On July 27, President Kabila ordered the Rwandan and UgandanArmies to leave the country. A weeklater, he terminated the appointments of all Tutsi public officials. The Congolese people regarded the Tutsis asforeigners, despite the fact that Banyamulenge Tutsis were long established inthe Congo’seastern provinces.

As a result of President Kabila’s edict, Uganda pulled out its forces from the Congo. The Rwandan government also ordered itsforces to withdraw, not out of the Congo,but to the remote, weakly defended Kivu Provinces in eastern Congo. Rwanda believed that its securityconcerns – the main reason for its involvement in the First Congo War – had notbeen fully met. In particular, theRwandan government noted that the Hutu militias had reorganized and once againwere carrying out raids into Rwanda. Furthermore, the Banyamulenge Tutsis, who hadformed an alliance with Rwandaduring the First Congo War, requested the Rwandans to remain in the KivuProvinces. The Banyamulenge’scitizenship had been revoked by a new law, and the Congolese government orderedthem to leave the country.

Rwandaand Ugandaorganized the Banyamulenge into a proxy militia called the “Rally for CongoleseDemocracy”, or RCD, whose aim was to overthrow President Kabila. As in the First Congo War, Rwanda and Uganda used a proxy force to fighttheir wars, as direct intervention by their armies was a violation ofinternational law.