Daniel Orr's Blog, page 11

September 18, 2024

September 18, 1931 – The Mukden Incident takes place, giving Japan a pretext to invade Manchuria

On the night of September 18, 1931, Kwantung Army LieutenantSuemori Kawamoto set off a small explosive on a small section of the SouthManchuria Railway line near Mukden. The explosion caused only minor damage to therail track and a Mukden-bound train passed through it later withoutencountering any difficulty. KwantungArmy conspirators, led by officers Itagaki and Ishiwara, initiated this action,which historically is called the Mukden Incident, in order to accuse theChinese of armed provocation and thereby justify a Japanese military reactionthat would lead to a full-scale conquest of Manchuria.

Japan controlled the South Manchuria Railway from Ryojun (formerly Port Arthur) to Mukden and further north by the time of its invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

Japan controlled the South Manchuria Railway from Ryojun (formerly Port Arthur) to Mukden and further north by the time of its invasion of Manchuria in 1931.Immediately following the Mukden Incident, on ColonelItakagi’s orders, Japanese forces attacked the Chinese Army garrison at Mukden. The7,000-man garrison Chinese force did not resist the 500 Japanese attackers, butfled their garrison and Mukden. Col. Itakagi also mobilized Japanese forcesall across the 1,100-km long South Manchuria Railway and as per thepre-arranged plan, moved to seize towns and cities throughout Manchuria.

In Ryojun (Port Arthur), Kwantung Army commander General Honjo wasinfuriated that junior officers had initiated military action without hisapproval. But after being counseled byCol. Ishiwara and the other conspirators, General Honjo was won over, andimmediately requested more troops to be brought in from Korea. A few hours after the start of hostilities,on September 19, 1931, General Honjo transferred the Kwantung Army headquartersto Mukden, which by now was under fullJapanese control.

Within a few days, Japanese forces seized much of Liaoningand Kirin (Jilin) provinces, including virtually all regions, towns, and citiessuch as Anshan, Haicheng, Kaiyuan, Tieling, Fushun, Changchun, Yingkou, Antung,Changtu, Liaoyang, Kirin, Chiaoho, Huangkutun, and Hsin-min. In Tokyo, thecentral government was stunned by this latest act of gekokujō (militaryinsubordination, which was widespread among junior officers), but gave itsconsent and sent more Japanese troops to Manchuriato support the Kwantung Army’s spectacular successes.

Thereafter, Japanese military authorities successfullyco-opted many Chinese military commanders (including Generals Xi Qia, ChangChing-hui, and Chang Hai-peng), warlords, and officials to form local andprovincial administrations in the various jurisdictions, replacing the deposedpro-KMT governments. By October 1931,many such pro-Japanese local governments had been established in Kirin (Jilin) and Liaoningprovinces. The Japanese conquest ofsouthern Manchuria was completed in early January 1932 with the capture ofChinchow (Jinzhou) and Shanhaiguan, with Chineseforces offering no resistance and withdrawing south of the Great Wall into Hebei Province.

Earlier in October 1931, pro-Japanese General Xu Jinglongled an army north to take HeilongjiangProvince, but met strong resistance atthe Nen River crossing near Jiangqiao. But with the support of Japanese troops thatprotected work crews repairing the bridge, the attack soon broke through and byNovember 18, 1931, Tsitsihar (Qiqihar), theprovincial capital, was taken, with loyalist General Ma Zhanshan and his troopsescaping to the east of Heilongjiang Province. Following the conquest of southern Manchuria, Japanese authorities tried to win over throughnegotiations Ma Zhanshan and the other defiant northern KMT commander, GeneralTing Chao, but failed. Japanese forcesthen launched an offensive to take Harbin, thelast KMT stronghold in Manchuria, which fellin early February 1932. In this battle,the Japanese came to the assistance of their collaborationist Chinese allieswhose attack earlier had been thrown back by loyalist Chinese forces.

To provide legitimacy to its conquest and occupation ofManchuria, on February 18, 1932, Japanestablished Manchukuo (“State of Manchuria”), purportedly an independent state, with itscapital at Hsinking (Changchun). Puyi, the last and former emperor of China under the Qing dynasty, was named Manchukuo’s “head ofstate”. In March 1934, he was named“Emperor” when Manchukuowas declared a constitutional monarchy.

Manchukuo was viewed bymuch of the international community as a puppet state of Japan, andreceived little foreign recognition. Infact, Manchukuo’s government was controlled byJapanese military authorities, with Puyi being no more than a figurehead andthe national Cabinet providing the front for Japanese interests in Manchuria.

Beset by internal turmoil, Chang Kai-shek’s Nationalistgovernment in Nanjingwas unable to military oppose the Japanese invasion, for a number ofreasons. First, in the period afterreunifying China in 1928,Chiang struggled to maintain control of the country, as large parts of China remainedde facto autonomous and were dominated by powerful warlords who pledged onlynominal allegiance to the central government. Second, even Chiang’s own government was racked by power struggles, andpolitical rivals tried to set up alternative regimes in other parts of thecountry. Third, Chiang also faced agrowing communist insurgency (under the Communist Party of China), which in theyears ahead, would become a major threat to his authority. To confront these domestic problems and alsodeeming that China was yet military incapable of facing Japan in war, Chiang adoptedthe policy of “First internal pacification, then external resistance”, that is,first, defeat the communists, warlords, and political rivals, and then confrontJapan.

Chinasought international diplomatic support. On September 19, 1931, one day after the start of hostilities, itappealed to the League of Nations to exert pressure on Japan. On September 22, the League called on the twosides to resolve their disputes peacefully. But with Japancontinuing armed action, on October 24, 1931, the League passed a resolutiondemanding that Japanese forces withdraw from Manchuriaby November 16, which was rejected by the Japanese government.

The League then formed the investigative Lytton Commission(named after the British administrator Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl ofLytton), which arrived in Chinain January 1932, to determine the causes of the conflict. In October 1932, the Lytton Commissionreleased a report, whose findings included the following: that Japan was the aggressor and its claim of acting inself-defense was untrue; and that China’s anti-Japanese policies andrhetoric, and refusal to compromise, aggravated the crisis. No mention was made of the side responsiblefor causing the Mukden Incident. TheCommission also refused to recognize Manchukuo,stating that it did not come from a “genuine and spontaneous independencemovement”. In February 1933, the Leagueof Nations approved the Lytton Commission’s report; the following month, Japanrevoked its membership in the League and left.

(Taken from Japanese Invasion of Manchuria – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

September 17, 2024

September 17, 1980 –Nicaraguan Revolution: Nicaragua’s ex-President Anastasio Somoza Debayle is assassinated in Paraguay

On September 17, 1980, Nicaragua’s former president, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, was assassinated in Paraguay. Somoza had been overthrown by Sandinista rebels in a revolution 14 months earlier, fleeing into exile on July 17, 1979 first to the United States and then settling in Paraguay after the U.S. government denied his entry. The Sandinistas, so-named from the socialist organization, Sandinista National Liberation Front (Spanish: Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional), took over power in Nicaragua after waging a lengthy struggle since 1961 (called the Nicaraguan Revolution) .

Central America

Central AmericaThe Sandinistas took over the government, allowing acivilian junta that had been set up earlier by the opposition coalition to rulethe country. The junta represented across-section of the political opposition and was structured as a power-sharinggovernment.

Non-Sandinista members of the junta soon resigned, as they felt powerless against the Sandinistas (who effectively controlled the junta) and feared that the government was moving toward adopting Cuban-style socialism.

(Excerpts taken from Nicaraguan Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

By 1980, the Sandinistas had taken full control of the government. The country had been devastated by the war, as well as by the corruption and neglect by the previous dictatorial regimes. Using the limited resources available, the Sandinista government launched many programs for the general population. The most successful of these programs were in public education, where the country’s high illiteracy rate was lowered significantly, and in agrarian reform, where large landholdings, including those of ex-President Somoza, were seized and distributed to the peasants and poor farmers. The Sandinista government also implemented programs in health care, the arts and culture, and in the labor sector.

U.S. President Jimmy Carter was receptive to the Sandinistagovernment. But President Ronald Reagan,who succeeded as U.S. headof state in January 1981, was alarmed that Nicaraguahad allowed a communist toehold in the American continental mainland, andtherefore posed a threat to the United States. President Reagan believed that the Sandinistas planned to spreadcommunism across Central America. As evidence of this perception, PresidentReagan pointed out that the Sandinistas were arming the communist insurgents inEl Salvador. Consequently, President Reagan prepared plansfor a counter-revolution in Nicaraguathat would overthrow the Sandinista government. The NicaraguanCounter-Revolution would last until 1990.

Background In 1961, the revolutionary movement called the Sandinista National Liberation Front was formed in Nicaragua with two main objectives: to end the U.S.-backed Somoza regime, and establish a socialist government in the country. The movement and its members, who were called Sandinistas, took their name and ideals from Augusto Sandino, a Nicaraguan rebel fighter of the 1930s, who fought a guerilla war against the American forces that had invaded and occupied Nicaragua. Sandino also wanted to end the Nicaraguan wealthy elite’s stranglehold on society. He advocated for social justice and economic equality for all Nicaraguans.

By the late 1970s, Nicaragua had been ruled for overforty years by the Somoza family in a dynastic-type succession that had begunin the 1930s. In 1936, Anastacio Somozaseized power in Nicaraguaand gained total control of all aspects of the government. Officially, he was the country’s president,but ruled as a dictator. Over time,President Somoza accumulated great wealth and owned the biggest landholdings inthe country. His many personal andfamily businesses extended into the shipping and airlines industries,agricultural plantations and cattle ranches, sugar mills, and winemanufacturing. President Somoza tookbribes from foreign corporations that he had granted mining concessions in thecountry, and also benefited from local illicit operations such as unregisteredgambling, organized prostitution, and illegal wine production.

President Somoza suppressed all forms of opposition with theuse of the National Guard, Nicaragua’spolice force, which had turned the country into a militarized state. President Somoza was staunchly anti-communistand received strong military and financial support from the United States, which was willing to take Nicaragua’srepressive government as an ally in the ongoing Cold War.

In 1956, President Somoza was assassinated and was succeededby his son, Luis, who also ruled as a dictator until his own death by heartfailure in 1967. In turn, Luis wassucceeded by his younger brother, Anastacio Somoza, who had the same first nameas their father. As Nicaragua’s new head of state,President Somoza outright established a harsh regime much like his father hadin the 1930s. Consequently, theSandinistas intensified their militant activities in the rural areas, mainly innorthern Nicaragua. Small bands of Sandinistas carried outguerilla operations, such as raiding isolated army outposts and destroyinggovernment facilities.

By the early 1970s, the Sandinistas comprised only a smallmilitia in contrast to Nicaragua’sU.S.-backed National Guard. TheSandinistas struck great fear on President Somoza, however, because of therebels’ symbolic association to Sandino. President Somoza wanted to destroy the Sandinistas with a passion thatbordered on paranoia. He ordered hisforces to the countryside to hunt down and kill Sandinistas. These military operations greatly affectedthe rural population, however, who began to fear as well as hate thegovernment.

The end of the Somoza regime began in 1972 when a powerfulearthquake hit Managua, Nicaragua’s capital. The destruction resulting from the earthquakecaused 5,000 human deaths and 20,000 wounded, and left half a million peoplehomeless (nearly half of Managua’spopulation). Managua was devastated almost completely,cutting off all government services. Inthe midst of the destruction, however, President Somoza diverted theinternational relief money to his personal bank account, greatly reducing thegovernment’s meager resources. Consequently, thousands of people were deprived of food, clothing, andshelter.

September 16, 2024

September 16, 1982 – 1982 Lebanon War: The Sabra and Shatila Massacre takes place

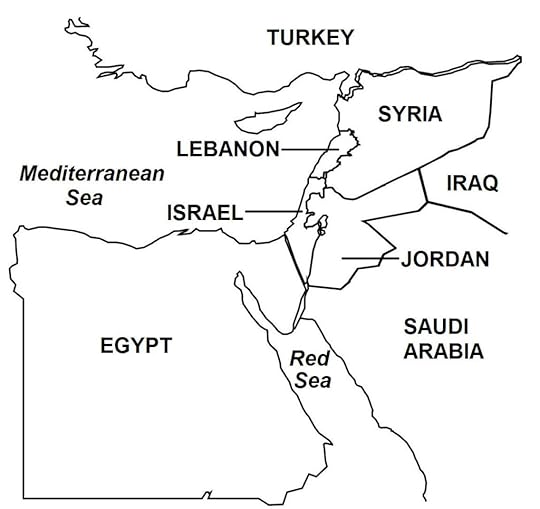

On September 16, 1982, Phalange militias carried out the Sabra and Shatila massacre, where between 500 and 3,500 mostly Palestinian and Muslim civilians were killed in the Sabra neighbourhood and nearby Shatila refugee camp in Beirut. The Phalange was a militia associated with the Kataeb Party, a mainly Christian Lebanese right-wing party. The massacre occurred during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) and the Israel military intervention in Lebanon (also known as the 1982 Lebanon War; 1982-1985).

The incident took place after the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) had been withdrawn from Lebanon under UN supervision. Israeli forces believed that other PLO fighters were hiding in Sabra and Shatila, and instructed their Phalange allies to clear these areas, leading to the mass killings. The massacre also occurred one day after the assassination of newly elected Lebanese president Bachir Gemayel of the Kataeb Party, which Israel and Phalange believed had been perpetrated by the PLO.

Israel’s intervention in Lebanon, the 1982 Lebanon War, was aimed at destroying the PLO camps in southern Lebanon. The Lebanese Civil War was a complex multi-faceted, multi-sectarian conflict that involved Lebanon’s government forces, many religious and ideological groups, complicated by the direct military interventions of Israel and Syria as well as being a proxy battleground of the Cold War.

(Taken from 1982 Lebanon War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1978 failed to achieve peace in the region of northern Israel and South Lebanon. After the war, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) returned to South Lebanon, where it re-established authority and resumed its attacks on Israel. In turn, Israel launched air strikes against the PLO. The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), which had arrived in South Lebanon after the war to enforce the ceasefire, was unable to stop the upsurge of violence. The Lebanese government itself had lost authority in South Lebanon, as it was embroiled in a bitter civil war, where the state had become powerless against the many rival sectarian militias that had carved up the country into separate zones of control. Syria also had sent its armed forces to Lebanon (at the request of the Lebanese government), occupied sections of the country, and exerted great influence in the country’s security and political climate.

By 1982, cross-border and retaliatory attacks by the PLO andIsraelhad increased considerably. ArielSharon, Israel’s defense minister, developed a plan to invade Lebanon with the following objectives: expel thePLO from South Lebanon, force out the Syrian Army from Lebanon, and install a pro-Israeligovernment consisting of Lebanese Maronite Christians. The Israeli government rejected the plan,however, reasoning that such a large-scale operation could potentially costheavy casualties on the Israeli Army.

On June 3, 1982, Shlomo Argov,Israel’s ambassador to the United Kingdom,was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt carried out by the Abu NidalOrganization, a Palestinian militant movement that was a rival of the PLO. Israelthen launched massive air and artillery attacks in South Lebanon. The PLO, declaringthat it had nothing to do with the assassination attempt on the Israelidiplomat, retaliated with rocket attacks in northern Israeli villages near theborder. On June 4, 1982, the Israeligovernment authorized its armed forces to invade South Lebanon.

War On June 4, 1982, Israeli forces crossed the Blue Line,the de facto Israel-Lebanon “border”. Israel’s initially stated objective was to pushthe PLO twenty-five kilometers north of the Blue Line, a distance that wouldplace northern Israelout of reach of Palestinian artillery fire. Israeli forces hoped to complete the operationwithin 24 hours. As the war progressed,however, Israelwould expand its military, as well as political, objectives.

The Israeli offensive was carried out along three fronts:from the Mediterranean coast to deny the PLO an escape route to the sea; fromcentral Lebanon in thedirection of the Beirut-Damascus Road; and along the Syria-Lebanon border to cutoff supply lines from Syria. The Israelis also carried out amphibiouslandings of armored and infantry units north of Sidon to seal off a northward escape routefor the PLO. Artillery from Israeliships shelled South Lebanon’s coastal roads todisrupt PLO logistical lines.

September 15, 2024

September 15, 1950 – Korean War: U.S. forces land on Inchon

As early as July 1950, General Douglas MacArthur hadconceived of a plan to launch a UN amphibious assault at Inchonharbor, located 27 kilometers southwest of Seoul on the central west coast. The success of such an operation would havethe strategic effect of destabilizing the North Korean supply lines to thesouth, and threaten the North Korean forces fighting in the PusanPerimeter. The U.S. Joint Chiefs ofStaff (JCS) initially were skeptical about the operation because of the risksinvolved, but soon gave its approval when General MacArthur expressedunwavering optimism in the feasibility of his plan. U.S.forces then prepared to launch an amphibious landing on Inchon.

Key areas during the Korean War

Key areas during the Korean WarOn September 15, 1950, preceded by days of heavy air attacksand naval artillery bombardment, some 75,000 U.S. and South Korean troops (ofthe newly reconstituted U.S. X Corps) in 260 naval vessels were amphibiouslylanded north and south of Inchon, taking the city where they met only lightresistance from the small North Korean garrison.

The unexpected UN landing at Inchon dealt a psychological blow to NorthKorean forces at the Pusan Perimeter. Already weakened by shortages of food and ammunitions, and risingcasualties, by the third week of September 1950, North Korean resistance collapsed,with whole military units breaking down, and tens of thousands of troopsfleeing north or to the mountains, or surrendering en masse. For the North Korean Army, its defeat at thePusan Perimeter was catastrophic: some 65,000 (over 60%) of its 98,000 troopswere lost; it had lost nearly all its tanks and artillery pieces; and mostcrucially, it ceased to be a force capable of stopping the UN forces which nowbegan to steamroll northward.

By September 23, 1950, UN forces, comprising largely of theEighth U.S. Army, had broken out of the Pusan Perimeter, and advanced northsome 100 miles, on September 27 linking up with X Corps units from the Inchonlandings at Osan. However, the UNforces’ aim of linking their units rather than actively pursuing the enemy allowedsome 30,000 retreating North Korean soldiers from the Pusan Perimeter to escapeand eventually cross the 38th parallel into North Korea, where they soon werereorganized into new fighting units. Other North Korean units that took to the mountains in the south alsoformed small militias that engaged in guerilla warfare.

UN forces at Inchonsoon recaptured Kimpo airfield. There, U.S. planes began to conduct air strikes onNorth Korean positions in and around Seoul. UN ground forces then launched a three-prongedattack on the capital. They met heavyNorth Korean resistance at the perimeter but soon captured the heightsoverlooking the city. On September 25,1950, UN forces entered Seoul,and soon declared the city liberated. Even then, house-to-house fighting continued until September 27, whenthe city was brought under full UN control. On September 29, 1950, UN forces formally turned over the capital toPresident Syngman Rhee, who reestablished his government there. And by the end of September 1950, withremnants of the decimated North Korean Army retreating in disarray across the38th parallel, South Korean and UN units gained control of all pre-war SouthKorean territory.

On October 1, 1950, the South Korean Army crossed the 38thparallel into North Korea along the eastern and central regions; UN forces,however, waited for orders. Four daysearlier, on September 27, 1950, President Truman sent a top-secret directive toGeneral MacArthur advising him that UN forces could cross the 38th parallelonly if the Soviet Union or China had not sent or did not intend to send forcesto North Korea.

Earlier, the Chinese government had stated that UN forcescrossing the 38th parallel would place China’s national security at risk,and thus it would be forced to intervene in the war. Chairman Mao Zedong also stated that if U.S. forces invaded North Korea, Chinamust be ready for war with the United States.

At this stage of the Cold War, the United States believed that its biggest threatcame from the Soviet Union, and that the Korean War may very well be a Sovietplot to spark an armed conflict between the United States and China. This would force the U.S. military to divert troops and resources toAsia, and leave Western Europe open to aSoviet invasion. But after muchdeliberation, the Truman administration concluded that China was “bluffing” and would not reallyintervene in Korea,and that its threats merely were intended to undermine the UN. Furthermore, General MacArthur also later(after UN forces had crossed the 38th parallel) expressed full confidence inthe UN (i.e. U.S.)forces’ military superiority – that Chinese forces would face the “greatestslaughter” if they entered the war.

On October 7, 1950, the UNGA adopted Resolution 376 (V)which declared support for the restoration of stability in the Korean Peninsula,a tacit approval for the UN forces to take action in North Korea. Two days later, October 9, UN forces, led bythe Eighth U.S. Army, crossed the 38th parallel in the west, with General MacArthursome days earlier demanding the unconditional surrender of the North KoreanArmy. UN forces met only lightresistance during their advance north. On October 15, 1950, Namchonjam fell, followed two days later by Hwangju.

As early as July 1950, General MacArthur had conceived of aplan to launch a UN amphibious assault at Inchonharbor, located 27 kilometers southwest of Seoul on the central west coast. The success of such an operation would havethe strategic effect of destabilizing the North Korean supply lines to thesouth, and threaten the North Korean forces fighting in the PusanPerimeter. The U.S. Joint Chiefs ofStaff (JCS) initially were skeptical about the operation because of the risksinvolved, but soon gave its approval when General MacArthur expressedunwavering optimism in the feasibility of his plan. U.S.forces then prepared to launch an amphibious landing on Inchon.

On September 15, 1950, preceded by days of heavy air attacksand naval artillery bombardment, some 75,000 U.S. and South Korean troops (ofthe newly reconstituted U.S. X Corps) in 260 naval vessels were amphibiouslylanded north and south of Inchon, taking the city where they met only lightresistance from the small North Korean garrison.

The unexpected UN landing at Inchon dealt a psychological blow to NorthKorean forces at the Pusan Perimeter. Already weakened by shortages of food and ammunitions, and risingcasualties, by the third week of September 1950, North Korean resistance collapsed,with whole military units breaking down, and tens of thousands of troopsfleeing north or to the mountains, or surrendering en masse. For the North Korean Army, its defeat at thePusan Perimeter was catastrophic: some 65,000 (over 60%) of its 98,000 troopswere lost; it had lost nearly all its tanks and artillery pieces; and mostcrucially, it ceased to be a force capable of stopping the UN forces which nowbegan to steamroll northward.

By September 23, 1950, UN forces, comprising largely of theEighth U.S. Army, had broken out of the Pusan Perimeter, and advanced northsome 100 miles, on September 27 linking up with X Corps units from the Inchonlandings at Osan. However, the UNforces’ aim of linking their units rather than actively pursuing the enemyallowed some 30,000 retreating North Korean soldiers from the Pusan Perimeterto escape and eventually cross the 38th parallel into North Korea, where theysoon were reorganized into new fighting units. Other North Korean units that took to the mountains in the south alsoformed small militias that engaged in guerilla warfare.

UN forces at Inchonsoon recaptured Kimpo airfield. There, U.S. planes began to conduct air strikes onNorth Korean positions in and around Seoul. UN ground forces then launched athree-pronged attack on the capital. They met heavy North Korean resistance at the perimeter but sooncaptured the heights overlooking the city. On September 25, 1950, UN forces entered Seoul, and soon declared the cityliberated. Even then, house-to-housefighting continued until September 27, when the city was brought under full UNcontrol. On September 29, 1950, UNforces formally turned over the capital to President Syngman Rhee, whoreestablished his government there. Andby the end of September 1950, with remnants of the decimated North Korean Armyretreating in disarray across the 38th parallel, South Korean and UN unitsgained control of all pre-war South Korean territory.

On October 1, 1950, the South Korean Army crossed the 38thparallel into North Korea along the eastern and central regions; UN forces,however, waited for orders. Four daysearlier, on September 27, 1950, President Truman sent a top-secret directive toGeneral MacArthur advising him that UN forces could cross the 38th parallelonly if the Soviet Union or China had not sent or did not intend to send forcesto North Korea.

Earlier, the Chinese government had stated that UN forcescrossing the 38th parallel would place China’s national security at risk,and thus it would be forced to intervene in the war. Chairman Mao Zedong also stated that if U.S. forces invaded North Korea, Chinamust be ready for war with the United States.

At this stage of the Cold War, the United States believed that its biggest threatcame from the Soviet Union, and that the Korean War may very well be a Sovietplot to spark an armed conflict between the United States and China. This would force the U.S. military to divert troops and resources toAsia, and leave Western Europe open to aSoviet invasion. But after muchdeliberation, the Truman administration concluded that China was “bluffing” and would not reallyintervene in Korea,and that its threats merely were intended to undermine the UN. Furthermore, General MacArthur also later(after UN forces had crossed the 38th parallel) expressed full confidence inthe UN (i.e. U.S.)forces’ military superiority – that Chinese forces would face the “greatestslaughter” if they entered the war.

On October 7, 1950, the UNGA adopted Resolution 376 (V)which declared support for the restoration of stability in the Korean Peninsula,a tacit approval for the UN forces to take action in North Korea. Two days later, October 9, UN forces, led bythe Eighth U.S. Army, crossed the 38th parallel in the west, with GeneralMacArthur some days earlier demanding the unconditional surrender of the NorthKorean Army. UN forces met only lightresistance during their advance north. On October 15, 1950, Namchonjam fell, followed two days later byHwangju.

September 14, 2024

September 14, 1960 – Mobutu Sese Seko launches a coup during the Congo Crisis

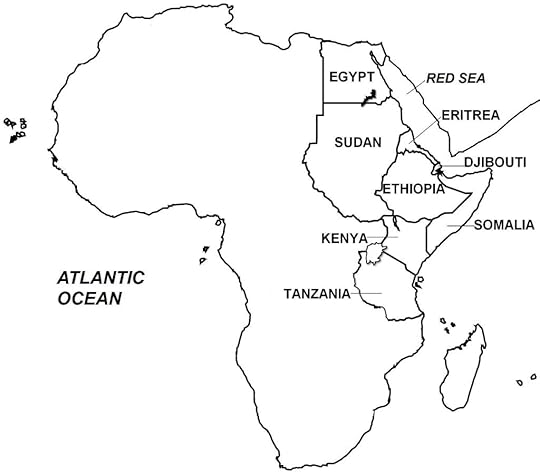

On September 14, 1960, Mobutu Sese Seko, head of the Congo military, seized power in the Republic of the Congo (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) in the midst of the Congo Crisis. The crisis consisted of a series of civil wars that began shortly after the country gained its independence from Belgium on June 30, 1960. Mobutu launched the coup following the political deadlock between Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and President Joseph Kasa-Vubu after Lumumba had sought Soviet support to quell a Belgian-supported uprising in Katanga and South Kasai.

After the coup, Mobutu remained as head of the Congo military until November 1965, when he seized power in another coup following another political impasse. He would hold power over a totalitarian government for the next 32 years.

In his long reign, he grossly mismanaged the country, which he renamed Zaire. Government corruption was widespread, the country’s infrastructure was neglected, and poverty and unemployment were rampant. And while Zaire’s economy stagnated under a huge foreign debt, President Mobutu amassed a personal fortune of several billions of dollars.

In 1997, he was deposed in the First Congo War.

(First Congo War – Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Africa showing location of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and other African countries. At the time of the First Congo War, DRC was known as Zaire.

Africa showing location of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and other African countries. At the time of the First Congo War, DRC was known as Zaire.Background In themid-1990s, ethnic tensions rose in Zaire’s eastern regions. Zairian indigenous tribes long despised theTutsis, another ethnic tribe, whom they regarded as foreigners, i.e. theybelieved that Tutsis were not native to the Congo. The Congolese Tutsis were called Banyamulengeand had migrated to the Congoduring the pre-colonial and Belgian colonial periods. Over time, the Banyamulenge established somedegree of political and economic standing in the Congo’s eastern regions. Nevertheless, Zairian indigenous groups occasionallyattacked Banyamulenge villages, as well as those of other non-Congolese Tutsiswho had migrated more recently to the Congo.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the Congo’s eastern region was greatly destabilizedwhen large numbers of refugees migrated there to escape the ethnic violence in Rwanda and Burundi. The greatest influx occurred during theRwandan Civil War, where some 1.5 million Hutu refugees entered the Congo’sKivu Provinces (Map 17). The Huturefugees established giant settlement camps which soon came under the controlof the deposed Hutu regime in Rwanda,the same government that had carried out the genocide against RwandanTutsis. Under cover of the camps, Hutuleaders organized a militia composed of former army soldiers and civilianparamilitaries. This Hutu militiacarried out attacks against Rwandan Tutsis in the camps, as well as against theBanyamulenge, i.e. Congolese Tutsis. TheHutu leaders wanted to regain power in Rwandaand therefore ordered their militia to conduct cross-border raids from theZairian camps into Rwanda.

To counter the Hutu threat, the Rwandan government forged amilitary alliance with the Banyamulenge, and organized a militia composed ofCongolese Tutsis. The Rwandangovernment-Banyamulenge alliance solidified in 1995 when the Zairian governmentpassed a law that rescinded the Congolese citizenship of the Banyamulenge, andordered all non-Congolese citizens to leave the country.

War In October1996, the provincial government of South Kivu in Zaire ordered all Bayamulenge toleave the province. In response, theBanyamulenge rose up in rebellion. Zairian forces stepped in, only to be confronted by the Banyamulengemilitia as well as Rwandan Army units that began an artillery bombardment of South Kivu from across the border.

A low-intensity rebellion against the Congolese governmenthad already existed for three decades in Zaire. Led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the Congorebels opposed Zairian president Mobutu Sese Seko’s despotic, repressiveregime. President Mobutu had seizedpower through a military coup in 1965 and had in his long reign, grosslymismanaged the country. Governmentcorruption was widespread, the country’s infrastructure was crumbling, andpoverty and unemployment were rampant. And while Zaire’seconomy stagnated under a huge foreign debt, President Mobutu amassed apersonal fortune of several billions of dollars.

Kabila joined his forces with the Banyamulenge militia;together, they united with other anti-Mobutu rebel groups in the Kivu, with thecollective aim of overthrowing the Zairian dictator. Kabila soon became the leader of this rebelcoalition. In December 1996, with thesupport of Rwanda and Uganda,Kabila’s rebel forces won control of the border areas of the Kivu. There, Kabila formed a quasi-government thatwas allied to Rwanda and Uganda.

The Rwandan Army entered the conquered areas in the Kivu anddismantled the Hutu refugee camps in order to stop the Hutu militia fromcarrying out raids into Rwanda. With their camps destroyed, one batch of Huturefugees, comprising several hundreds of thousands of civilians, was forced tohead back to Rwanda.

Another batch, also composed of several hundreds ofthousands of Hutus, fled westward and deeper into Zaire, where many perished fromdiseases, starvation, and nature’s elements, as well as from attacks by theRwandan Army.

When the fighting ended, some areas of Zaire’s eastern provinces virtuallyhad seceded, as the Zairian government was incapable of mounting a strongmilitary campaign into such a remote region. In fact, because of the decrepit condition of the Zairian Armed Forces,President Mobutu held only nominal control over the country.

The Zairian soldiers were poorly paid and regularly stoleand sold military supplies. Poordiscipline and demoralization afflicted the ranks, while corruption was rampantamong top military officers. Zaire’smilitary equipment often was non-operational because of funding shortages. More critically, President Mobutu had become theenemy of Rwanda and Angola,as he provided support for the rebel groups fighting the governments in thosecountries. Other African countries thatalso opposed Mobutu were Eritrea,Ethiopia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

In December 1996, Angolaentered the war on the side of the rebels after signing a secret agreement withRwanda and Uganda. The Angolan government then sent thousands ofethnic Congolese soldiers called “Katangese Gendarmes” to the KivuProvinces. These Congolese soldiers werethe descendants of the original Katangese Gendarmes who had fled to Angola in the early 1960s after the failedsecession of the Katanga Province from the Congo.

The presence of the Katangese Gendarmes greatly strengthenedthe rebellion: from Goma and Bukavu (Map 17), the Gendarmes advanced west andsouth to capture Katanga andcentral Zaire. On March 15, 1977, Kisanganifell to the rebels, opening the road to Kinshasa, Zaire’scapital. Kalemie and Kamina in Katanga Provincewere captured, followed by Lubumbashiin April. Later that month, the AngolanArmy invaded Zairefrom the south, quickly taking Tshikapa, Kikwit, and Kenge.

Kabila also joined the fighting. Backed by units of the Rwandan and UgandanArmed Forces, his rebel coalition force advanced steadily across central Zaire for Kinshasa. Kabila met only light resistance, as theZairian Army collapsed, with desertions and defections widespread in its ranks. Crowds of people in the towns and villageswelcomed Kabila and the foreign armies as liberators.

Many attempts were made by foreign mediators (United Nations, United States, and South Africa)to broker a peace settlement, the last occurring on May 16, 1977 when Kabila’sforces had reached the vicinity of Kinshasa. The Zairian government collapsed, withPresident Mobutu fleeing the country. Kabila entered Kinshasaand formed a new government, and named himself president. The First Congo War was over; the secondphase of the conflict broke out just 15 months later (next article).

September 13, 2024

September 13, 1948 – Indian forces invade Hyderabad to force annexation

On September 13, 1948, the Indian Army invaded the state of Hyderabad. Four days later, the Nizam (monarch) of Hyderabad surrendered. In November 1948, he signed the Instrument of Accession to India, and the independent state of Hyderabad ceased to exist.

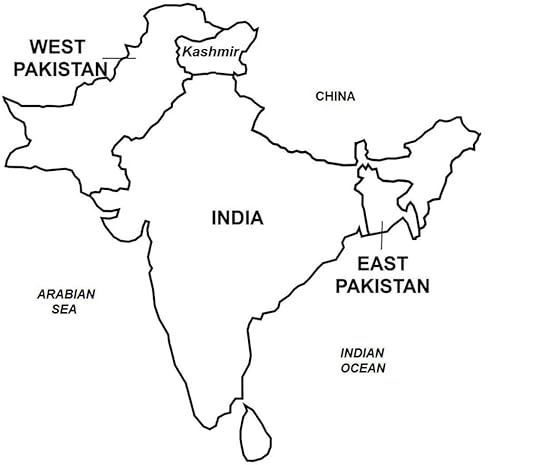

Britainapproved the Indian Independence Act in July 1947, partitioning British Indiainto two new independent dominions: Indiaand Pakistan.On August 14, 1947, Pakistandeclared independence, and the next day, India also declared itsindependence.

At the time of partition into India and Pakistan, there also existed in the Indian subcontinent semi-autonomous polities called “princely states”, numbering 565 and covering 40% of the territory, and comprising 23% of the population. Before the British withdrew, they offered the princely states two options: to be incorporated politically and geographically into either India or Pakistan, or to revert to their pre-colonial status as independent political entities. A great majority of the Princely States took the option suggested by the British and joined either one of the two new countries, but most with India with whom they shared a common border as well as religious ties.

Hyderabad, which shared allits borders with India butnone with Pakistan,was led by a Muslim monarch (the Nizam) who ruled over a largely Hindu population.Hyderabad was also the wealthiest and most militarilypowerful of the princely states and the Nizam owned 40% of all Hyderabad lands. Notwanting to accede to Hindu-majority India,the Nizam declared Hyderabad’sindependence in August 1947. However, Indiawas determined to integrate Hyderabadwith itself, averse to the presence of a hostile neighbour. Negotiationsbetween the two sides were held from November 1947 to June 1948, which failedto reach an agreement.

Ultimately, the Indian government was prompted to takemilitary action because of what it perceived were violations of the Hyderabad state: carrying out relations with Pakistan,interfering with Indian traffic at its borders, and most seriously, building upparamilitary force numbering 200,000 irregulars (“razakars”) apart from the stateforce of 22,000 troops.

In the immediate aftermath of the Indian invasion, widespread communal violence broke out with Hindus attacking Muslims. Executions, murders, rapes, and lootings were widespread. Some 30,000-40,000 were killed, with one estimate putting the figure at 200,000 or higher.

(Partition of India; taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

In the Indian subcontinent (Map 12), which was Britain’sprized possession since the 1800s, a strong nationalist sentiment had existedfor many decades and had led to the emergence of many political organizationsthat demanded varying levels of autonomy and self-rule. Other Indian nationalist movements alsocalled for the British to leave immediately. Nationalist aspirations were concentrated in areas with direct Britishrule, as there also existed across the Indian subcontinent hundreds ofsemi-autonomous regions which the British called “Princely States”, whoserulers held local authority with treaties or alliances made with the Britishgovernment. The Princely States,however, had relinquished their foreign policy initiatives to the British inexchange for British military protection against foreign attacks. Thus, the British de facto ruled over thePrincely States.

Lord Mountbatten also settled the fates of the PrincelyStates, which accounted for about one-third of the area of the Indiansubcontinent. In a plenary meeting withthe heads of the Princely States in July 1947, the Governor-General offeredthem two options: to be incorporated politically and geographically into eitherIndia or Pakistan, or to revert to theirpre-colonial status as independent political entities. Lord Mountbatten, however, cautioned thePrincely States against taking the second option, saying that they risked beingoverwhelmed by their two new giant neighbors, Indiaand Pakistan.

A great majority of the Princely States took the optionsuggested by Lord Mountbatten and joined either one of the two new countries,but most with India with whom they shared a common border as well as religiousties. Two PrincelyStates, Manipur and Tripura, opted forindependence in 1947, but agreed to be incorporated into India two years later. Hyderabad,with a Muslim ruler and a majority Hindu population, and geographically locatedinside India,declared independence. In 1948, India invaded Hyderabadand subsequently annexed the former Princely State. Junagadh also had a Muslim ruler and apredominantly Hindu constituency, and chose to be assimilated into Pakistanbut without whom it shared a border. Anuprising soon broke out among Hindus, whereupon the Indian Army invadedJunagadh, forcing the Muslim ruler to flee into exile. In a plebiscite that later was held inJunagadh, the overwhelming majority of voters chose to be incorporated into India. Soon thereafter, India annexed Junagadh.

At partition, the Princely State of Kashmir becameindependent but found itself geographically straddled between India and Pakistan. Kashmir’sHindu monarch, who ruled over a predominantly Muslim constituency, chose toremain politically neutral. Both India and particularly Pakistan, however, wanted to annex Kashmir, and thus exerted pressure on the Kashmirimonarch. In October 1947, a revolt brokeout in Kashmir, triggering the Indian-Pakistani War of 1947, which was thefirst of three major wars fought between Indiaand Pakistan over Kashmir and the start of a long-standing dispute thatcontinues to this day.

September 12, 2024

September 12, 1974 – Ethiopian Civil War: Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia is ousted in a military coup

On September 12, 1974, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown in a military coup by the Derg, ending both his reign of 58 years and the 800 year-old Ethiopian Empire. The Derg consisted of Ethiopian reformist junior officers under the name “Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army”, some 110 to 120 enlisted men and officers (none above the rank of major) from the 40 military and security units across the country. This group became known simply as Derg (an Ethiopian word meaning “Committee” or “Council”) had as its (initial) aims to serve as a conduit for various military and police units in order to maintain peace and order, and also to uphold the military’s integrity by resolving grievances, disciplining errant officers, and curbing corruption in the armed forces.

Ethiopia and adjacent countries in Africa

Ethiopia and adjacent countries in AfricaFollowing the coup, the Derg seized control of government butdid not abolish the monarchy outright, and announced that Crown Prince AsfaWossen, Haile Selassie’s son who was currently abroad for medical treatment,was to succeed to the throne as the new “king” on his return to thecountry. However, Prince Wossen rejectedthe offer and remained abroad. The Dergthen withdrew its offer and in March 1975, abolished the monarchy altogether,thus ending the 800 year-old Ethiopian Empire. (On August 27, 1975, or nearly one year after his arrest, Haile Selassiepassed away under mysterious circumstances, with Derg stating thatcomplications from a medical procedure had caused his death, while criticsalleging that the ex-monarch was murdered.)

The political instability and power struggles that followedthe Derg’s coming to power, the escalation of pre-existing separatist andMarxist insurgencies (as well as the formation of new rebel movements), and theintervention of foreign players, notably Somalia as well as Cold War rivals,the Soviet Union and United States, all contributed to the multi-party,multi-faceted conflict known as the Ethiopian Civil War.

(Taken from Ethiopian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background By early 1974 but unbeknownst at that time, the 44-year reign of Ethiopia’s aging emperor, Haile Selassie, was verging on collapse under the burgeoning weight of various internal hostile elements. Haile Selassie had ascended to the throne in April 1930, bearing the official title, “His Imperial Majesty the King of Kings of Ethiopia, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God”, to reign over the Ethiopian Empire that had been in existence for 800 years. Except for a brief period of occupation by the Italian Army from 1936 to 1941, Ethiopia had escaped falling under the control of European powers that had carved up the African continent into colonial territories during the 19th century. (The latter event, known as the Scramble for Africa, saw only two African states, Ethiopia and Liberia, that did not come under European domination.)

Under Haile Selassie’s rule, Ethiopia became a founding memberstate of the United Nations in 1945 and the Organization of African Unity in1963. The Ethiopian emperor had placedgreat emphasis on his personal, as well as Ethiopia’s,role in post-World War II international affairs, and as such, had played amajor role in peacemaking and contributed to mediation efforts in variousAfrican conflicts (e.g. the Congo,Biafra, Algeria,and Morocco). By the 1970s (at which time, he was at theadvanced age of 80), Haile Selassie was widely regarded in the internationalcommunity and respected as an elder statesman and a great African fatherfigure.

At the same time, however, Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia wasmired in numerous internal problems, foremost of which was great social unrestgenerated by the deeply entrenched conservative monarchy, aristocraticnobility, and wealthy landowning and business classes that opposed reformswhich were being called for by the various emerging militant sectors ofsociety. In some regions, somelandowners owned large tracts of agricultural land, relegating most of therural population to tenant farmers and farm laborers in a semi-feudal,patronage system. Haile Selassie madesome attempts to implement land reform and other measures of agrarian equality,but these were opposed by the wealthy landowners. Social tensions also existed among Ethiopia’s manyethnic groups, which were further compounded because of the monarch’s de factoabsolute rule and sometimes inequitable policies that favored his own Amharicethnic class to the detriment of other regional ethnic groups.

Ethnic tensions sometimes led to armed rebellion, such asthose that occurred in northern Wollo in 1930, Tigray in 1941, and Gojjam in1968. Haile Selassie placed muchemphasis on promoting education, but his government made only modest gains totransform the elitist educational structure into a universal public schoolsystem, e.g. by the early 1970s, some 90% of Ethiopians were stillilliterate. Ironically, however, Ethiopia’s educational system became thebreeding ground for radical ideas, as university students, particularly thosestudying in Europe, became exposed toMarxism-Leninism. In the 1960s and1970s, many ethnicity-motivated, separatist, or socialist movements emerged in Ethiopia. Among the more important Marxist groups werethe All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement and Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party,while major regional movements included the Western Somali Liberation Front(WSLF) and Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), both founded in 1960, and the OromoLiberation Front, organized in 1973.

For Haile Selassie’s regime, the most serious among theregional groups was the ELP-led Eritrean insurgency. Eritreahistorically had a long political development separate from Ethiopia, but the latter regarded Eritrea as anintegral part of the Ethiopian Empire. In September 1952, the United Nations federated Eritrea (then under temporary Britishadministration) with Ethiopia(the union known as the Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation), which granted Eritrea broadadministrative, legislative, judiciary, and fiscal autonomy but under the ruleof the Ethiopian monarch. However,Eritreans desired full sovereignty and in September 1961, the ELF launched aneventually lengthy 30-year armed struggle for independence.

By the 1960s, Ethiopia’sfeudalistic system, government corruption, and failure to implement land reformand other social programs were inciting student and activist groups to launchprotest demonstrations and mass assemblies in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’scapital. Ultimately, however, it was theEthiopian military that would set in motion the events that would overturn Ethiopia’spolitical system. In December 1960,reformist elements of the military, led by the commander of the Imperial Guard(the emperor’s personal security unit), launched a coup d’état to overthrowHaile Selassie, who was away on a state visit to Brazil. Most of the Ethiopian Armed Forces, however,remained loyal to the government, and the coup failed. In the aftermath, Haile Selassie strove tobring the military establishment under greater control, promoting more ethnicAmharic to the officer corps and plotting discord by playing military factionsagainst each other.

However, discontent remained pervasive within the military,particularly among the rank-and-file soldiers, who chafed at the low pay andpoor working conditions. In January1974, in what became the first of a series of decisive events, soldiersstationed at Negele, Sidamo Province, mutinied in protest of low wages andother poor conditions; in the following days, military units in other locationsmutinied as well. In February 1974, as aresult of rising inflation and unemployment and deteriorating economicconditions resulting from the global oil crisis of the previous year (1973),teachers, workers, and students launched protest demonstrations and marches in Addis Ababa demandingprice rollbacks, higher labor wages, and land reform in the countryside. These protests degenerated into bloodyriots. In the aftermath, on February 28,1974, long-time Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold resigned and was replaced byEndalkachew Makonnen, whose government raised the wages of military personneland set price controls to curb inflation. Even so, the government, which was controlled by nobles, aristocrats,and wealthy landowners, refused or were unaware of the need to implement majorreforms in the face of growing public opposition.

In March 1974, a group of military officers led by ColonelAlem Zewde Tessema formed the multi-unit “Armed Forces Coordinating Committee”(AFCC) consisting of representatives from different sectors of the Ethiopianmilitary, tasked with enforcing cohesion among the various forces and assistingthe government in maintaining authority in the face of growing unrest. In June 1974, reformist junior officers ofthe AFCC, desiring greater reforms and dissatisfied with what they saw was theAFCC’s close association with the government, broke away and formed their owngroup.

This latter group, which took the name “CoordinatingCommittee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army, soon grew to about110 to 120 enlisted men and officers (none above the rank of major) from the 40military and security units across the country, and elected Majors MengistuHaile Mariam and Atnafu Abate as itschairman and vice-chairman, respectively. This group, which became known simply as Derg (an Ethiopian word meaning“Committee” or “Council”), had as its (initial) aims to serve as a conduit forvarious military and police units in order to maintain peace and order, andalso to uphold the military’s integrity by resolving grievances, discipliningerrant officers, and curbing corruption in the armed forces.

Derg operated anonymously (e.g. its members were notpublicly known initially), but worked behind such populist slogans as “EthiopiaFirst”, “Land to the Peasants”, and “Democracy and Equality to all” to gainbroad support among the military and general population. By July 1974, the Derg’s power was felt notonly within the military but in the government itself, and Haile Selassie wasforced to implement a number of political measures, including the release ofpolitical prisoners, the return of political exiles to the country, passage ofa new constitution, and more critically, to allow Derg to work closely with thegovernment. Under Derg pressure, thegovernment of Prime Minister Makonnen collapsed; succeeding as Prime Ministerwas Mikael Imru, an aristocrat who held leftist ideas.

Haile Selassie’s concessions to the Derg included measuresto investigate government corruption and mismanagement. In the period that followed, Derg arrestedand imprisoned many high-ranking imperial, administrative, and military officials,including former Prime Ministers Habte-Wold and Makonnen, Cabinet members,military generals, and regional governors. In August 1974, a proposed constitution that called for establishing aconstitutional monarchy was set aside. Now operating virtually with impunity, the Derg took aim at the imperialcourt, dissolving the imperial governing councils and royal treasury, andseizing royal landholdings and commercial assets. By this time, Haile Selassie’s governmentvirtually had ceased to exist; de facto power was held by the military, or moreprecisely, by Derg.

The culmination of events occurred when Haile Selassie wasaccused of deliberately denying the existence of a widespread famine thatcurrently was ravaging Ethiopia’sWollo province, which already had killed some 40,000 to 80,000 to as many as200,000 people. Conflicting reportsindicated that Haile Selassie was not aware of the famine, was fully aware ofit, or that government administrators withheld knowledge of its existence fromthe emperor. By August 1974, largeprotest demonstrations in Addis Ababawere demanding the emperor’s arrest. Finally on September 12, 1974, the Derg overthrew Haile Selassie in abloodless coup, leading away the frail, 82-year old ex-monarch to imprisonment.

The Derg gained control of Ethiopia but did not abolish themonarchy outright, and announced that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, HaileSelassie’s son who was currently abroad for medical treatment, was to succeedto the throne as the new “king” on his return to the country. However, Prince Wossen rejected the offer andremained abroad. The Derg then withdrewits offer and in March 1975, abolished the monarchy altogether, thus ending the800 year-old Ethiopian Empire. (OnAugust 27, 1975, or nearly one year after his arrest, Haile Selassie passedaway under mysterious circumstances, with Derg stating that complications froma medical procedure had caused his death, while critics alleging that theex-monarch was murdered.)

September 11, 2024

September 11, 1969 – Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai hold an impromptu meeting at Beijing Airport

On September 11, 1969, Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin andChinese Premier Zhou Enlai held an urgent impromptu meeting at Beijing Airport to try and resolve the politicaland border crisis between their two countries. After 3½ hours, the two premiersreached a consensus: that their countries would resolve their differencesthrough peaceful means, that border talks that were broken in 1964 would berestarted, that diplomatic ties between the two states would be restored, andthat trade and transportation exchanges between their countries would bereopened.

The meeting was held to defuse tensions between the twocountries. Chinese authorities were concerned about the growing threat of warwith the Soviet Union. Despite appearing defiant, and warning Russia that it too had nuclear weapons, China was unprepared to go to war, and itsmilitary was far weaker than that of the Soviet Union. Exacerbating China’s position was its ongoingCultural Revolution, which was causing serious internal unrest.

In August-September 1969, believing that a Soviet nuclearattack would target China’smajor populated centers, the Chinese government prepared to empty the citiesand relocate the population and vital industries to remote locations. Large-scale underground civilian and militaryshelters were built in Beijingand other areas of the country. At Mao’surging, national and party leaders moved away from Beijingto different areas across China,to avoid the government being wiped out by a single Soviet nuclear attack onthe capital. By this time, even theWestern press believed that war was imminent between the two communist giants.

(Taken from Sino-Soviet Border Conflict – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

Background In November 1917, Russian communists seized power in Petrograd, and after emerging victorious in the Russian Civil War (October 1917-October 1922), they established the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (usually shortened to USSR or Soviet Union). Nearly 27 years later, in October 1949 in China, Mao Zedong founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC) when his Red Army all but defeated Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang) forces in the Chinese Civil War. In December 1949, Chiang and the Kuomintang fled from the Chinese mainland and moved to Taiwan, where he established his new seat of government.

Thereafter, the Soviet Unionand Red China established close fraternal ties. In February 1950, the two countries signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty ofFriendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance, athirty-year military alliance which included a Soviet low-cost loan of $300million to assist in the reconstruction of war-ravaged China. In December 1950, the Soviet governmentreturned to Chinasovereignty of the region of Lushun, including Port Arthur, located inthe Chinese northeast. And with Chinamilitarily intervening in the Korean War (previous article) in October 1950,the Soviet Union sent large amounts of weapons to China, and provided air coverduring the Chinese counter-offensive starting in late 1950. The period 1950-1958 saw close political,diplomatic, and economic relations between the two communist powers,particularly in relation to their common ideological struggle against theirCold War enemies, the United States and capitalist West.

In March 1953, Joseph Stalin, who had ruled the Soviet Unionfor over three decades, died suddenly, and was succeeded by NikitaKhrushchev. Khrushchev brought about aradical shift in Russia’sdomestic affairs, implementing a series of reforms collectively known asde-Stalinization. The most repressiveaspects of Stalinist policies were reversed: suppression and censorship werereduced; some economic and social reforms were introduced; political prisonerswere released; the Gulag camp conditions were improved; and Stalinistlandmarks, places, and monuments were renamed to erase memories of the Stalinera.

In foreign affairs, Khrushchev implemented “peacefulcoexistence” with the West, which was a dramatic reversal of Stalin’s policy ofconfrontation against capitalist/democratic countries. The Soviet Union increased trade with theWest, participated in international sports events, and allowed greater culturaland educational exchanges, and Western cinema and arts to enter the Soviet Union.

However, in China,Mao was alarmed by these changes in the Soviet Union. He had drawn inspiration for China’spolitical and economic development on the Stalinist model, and perceivedKhrushchev’s “peaceful coexistence” policies with the West as deviating fromMarxism-Leninism. As a result,Chinese-Soviet relations became strained, leading to a decade-long period (late1950s through the 1960s) of hostility known as the Sino-Soviet split. This split was aggravated by other regionaland global events which occurred during this period.

In 1958, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward, a large-scaleseries of programs in agriculture and heavy industries aimed at accelerating China’spath to communism. Mao’s plan was tovault China into a globaleconomic power that would surpass the Soviet Union and even the industrializedWestern powers, including Britainand the United States. However, the program ended in utterfailure. Together with a massivedrought, the policies of the Great Leap Forward caused widespread famine that ledto mass starvation. Some 36 millionpeople died from hunger, and another 40 million babies failed to be form, or atotal of 76 million deaths due to the “Great Chinese Famine”.

The Great Leap Forward also further strained Sino-Sovietrelations, as Khrushchev perceived Mao’s ambitious programs as a directchallenge to the Soviet Union’s leadership inthe socialist world. The Sovietgovernment then pulled out its military, technical and economic advisers from China. Then when Khrushchev visited the United States in September 1959, China saw this as further evidence that the Soviet Union had strayed from Marxism-Leninism, and hadbecome “soft” in its relations with the West.

In March 1959, when the Dalai Lama (Tibet’s spiritual leader) fled from Tibet into Indiafollowing a failed Tibetan revolt against Chinese rule, the Soviet governmentgave moral support to Tibet,angering Mao. Indiaitself also had a long-standing border dispute with China. When border clashes between India and Chinabroke out in 1959 which ultimately led to a limited war in 1962 (Sino-IndianWar, separate article), the Soviet Union remained neutral in the conflict andeven tacitly sided with India, which again provoked Mao.

Chinaalso wanted to invade Taiwanto fulfill its long-sought goal of reunifying China. However, China’sinvasion plan received only tepid support from the Soviet Union. In 1958, after China provoked the Second Taiwan Strait Crisisby shelling Quemoy and Matsu islands, the Soviet Foreign Ministry cautioned China against escalating the conflict, becausethe United States had sent anaval force to defend Taiwan.

September 10, 2024

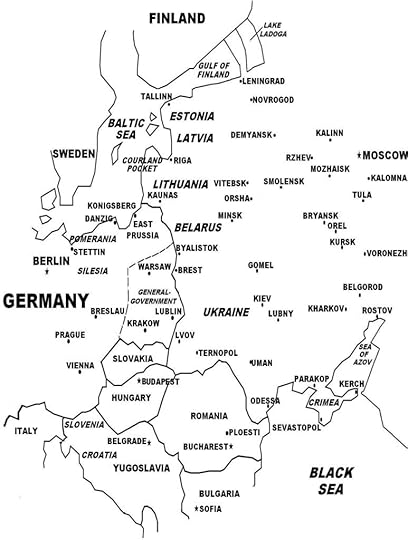

September 10, 1943 – World War II: German troops occupy Italy

On September 10, 1943 and continuing for several days, German forces seized control of Italy after the Italian government announced that it had signed the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allied Powers. The Germans disarmed the Italian troops and took over the Italian zones of occupation in the Balkans and southern France. In most cases, Italian units were unable to resist in the midst of chaos during the disarming process. A few units managed to resist as in the Greek island of Cephalonia, where the Italians surrendered after running out of ammunition, and in the Italian capital Rome, where a hastily mounted haphazard defense was easily overcome. In Sardinia, Corsica, Calabria, and few other areas, the Italians successfully resisted until the arrival of the Allies. Other Italian units joined the local resistance movement.

The Italian Campaign

The Italian Campaign(Taken from Italian Campaign – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

The invasion of Sicily alsoforced Germany to withdrawsome units in Russia,particularly from the ongoing Battle of Kursk (where the German offensive wasalready faltering), to confront the new threat. Thereafter, the Germans lost the initiative in the Eastern Front andwould permanently be on the defensive, a situation they also would face in theAllied campaign in Italy.

General Badoglio declared his continued alliance with Germany,but secretly opened peace talks with the Allies. Negotiations lasted two months, and onSeptember 8, the Italian government announced an agreement with the Allies,called the Armistice of Cassibile, where Italy surrendered to theAllies. Fearing German reprisal, KingVictor Emmanuel II, General Badoglio, and other leaders fled from Rome and set up headquarters in Allied-controlled southernItaly. There, on October 13, 1943, the Badogliogovernment declared war on Germany.

The Germans, which had increased their military presence inItaly since Mussolini’s ouster a few months earlier, and had gainedintelligence information that the new government was seeking a separate peacewith the Allies, now sprung into action and disarmed Italian forces in Italy,France, and the Balkan regions, and seized important military and publicinfrastructures across Italy. Italianmilitary units were unaware of the armistice, and thus were caught off-guardand generally failed to offer resistance to the German take-over. Then on September 12, 1943, Mussolini wasrescued from captivity by German commandos in a daring raid, and two weekslater, was installed by Hitler as head of the newly formed fascist state, the Italian SocialRepublic, covering Axis-controllednorthern and central Italy. Two rival governments now laid claim to Italy,and the former Italian Armed Forces became divided, fighting while aligned withone or the other side.

Meanwhile, in September 1943, the Allies were ready toinvade mainland Italy aftertheir capture of Sicilyone month earlier. On September 3, 1943,the same day that the armistice was signed, British 8th Army units in Sicily crossed the Gulfof Messina and landed at Reggio di Calabria, at the southwestern tip, or “toe” of Italy(Figure 36). The landing was unopposed,as the Germans had already retreated north while the Italian coastal batterieswere overwhelmed by Allied naval gunfire. Then on September 9, 1943, one day after the armistice was announced,the British made another amphibious landing at Tarantoin southeast Italy,which also was unopposed. The Alliesaimed the two landings to divert the Germans from the main landing at Salerno,some 200 miles further north off the western coast, which also was carried outon September 9, 1943 by the newly formed U.S. 5th Army (comprising one Americanand two British divisions). The Alliesalso anticipated that the Taranto-Salerno landings would exploit the confusionamong the Germans by the sudden announcement of the armistice.

However, by the time of the armistice, the Germans werefirmly established in Italy. And although many German units were divertedto disarm the Italian Army, a substantial force remained to guard against theexpected Allied invasion. Furthermore,General Albert Kesselring, commander of German forces in southern Italy, correctly surmised that the main Alliedlanding would not be made in southernmost Italy,but rather in the vicinity of Salerno, Naples, or even Rome,where he concentrated German forces from their withdrawal from the south.

September 9, 2024

September 9, 1944 – World War II: Pro-Soviet Fatherland Front seizes power in Bulgaria

On September 9, 1944, the Fatherland Front (FF) overthrew the pro-German government in Bulgaria during World War II. The FF, a coalition of various resistance groups that opposed the collaborationist regime, formed a new pro-Soviet government, signed a ceasefire with the Soviet Union, and declared war on Germany and the other Axis countries.

Soviet Counterattack in World War II

Soviet Counterattack in World War IIThe coup occurred at the time that the Soviet Red Army was rapidly approaching. The rapid collapse of Axis forces in Romania brought chaos to the pro-German government in Bulgaria. On August 26, 1944, the Bulgarian government declared its neutrality in the war. Bulgarians were ethnic Slavs like the Russians, and Bulgaria did not send troops to attack the Soviet Union and continued to maintain diplomatic ties with Moscow. However, its government was pro-German and the country was an Axis partner. On September 2, a new Bulgarian government was formed comprising the political opposition, which did not stop the Soviet Union from declaring war on Bulgaria three days later. On September 8, Soviet forces entered Bulgaria, meeting no resistance as the Bulgarian government stood down its army. The next day, Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, was captured, and the Soviets lent their support behind the new Bulgarian government comprising communist-led resistance fighters of the Fatherland Front. Bulgaria then declared war on Germany, sending its forces in support of the Red Army’s continued advance to the west.

(Taken from The Soviet Counter-offensive – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Aftermath The RedArmy now set its sights on Serbia,the main administrative region of pre-World War II Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia itself had beendismembered by the occupying Axis powers. For Germany, the lossof Serbia would cut off itsforces’ main escape route from Greece. As a result, the German High Commandallocated more troops to Serbiaand also ordered the evacuation of German forces from other Balkan regions.

Occupied Europe’s most effective resistance struggle waslocated in Yugoslavia. By 1944, the communist Yugoslav Partisanmovement, led by Josip Broz Tito, controlled the mountain regions of Bosnia, Montenegro,and western Serbia. In late September 1944, the Soviet 2nd and3rd Ukrainian Fronts, thrusting from Bulgariaand Romania, together withthe Bulgarian Army attacking from western Bulgaria,launched their offensive into Serbia. The attack was aided by Yugoslav partisansthat launched coordinated offensives against the Axis as well as conductingsabotage actions on German communications and logistical lines – the combinedforces captured Serbia, mostimportantly the capital Belgrade,which fell on October 20, 1944. Germanforces in the Balkans escaped via the more difficult routes through Bosnia and Croatia in October 1944. For the remainder of the war, Yugoslavpartisans liberated the rest of Yugoslavia;the culmination of their long offensive was their defeat of the pro-NaziUstase-led fascist government in Croatiain April-May 1945, and then their advance to neighboring Slovenia.

The succession of Red Army victories in Eastern Europe broughtgreat alarm to the pro-Nazi government in Hungary,which was Germany’slast European Axis partner. Then when inlate September 1944, the Soviets crossed the borders from Romania and Serbiainto Hungary, Miklos Horthy,the Hungarian regent and head of state, announced in mid-October that hisgovernment had signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. Hitler promptly forced Horthy, under threat,to revoke the armistice, and German troops quickly occupied the country.

The Soviet campaign in Hungary,which lasted six months, proved extremely brutal and difficult both for the RedArmy and German-Hungarian forces, with fierce fighting taking place in western Hungaryas the numerical weight of the Soviets forced back the Axis. In October 1944, a major tank battle wasfought at Debrecen,where the panzers of German Army Group Fretter-Pico (named after GeneralMaximilian Fretter-Pico) beat back three Soviet tank corps of 2nd UkrainianFront. But in late October, a powerfulSoviet offensive thrust all the way to the outskirts of Budapest, the Hungarian capital, by November7, 1944.

Two Soviet pincer arms then advanced west in a flankingmaneuver, encircling the city on December 23, 1944, and starting a 50-daysiege. Fierce urban warfare then brokeout at Pest, the flat eastern section of the city, and then later across the Danube Riverat Buda, the western hilly section, where German-Hungarian forces soonretreated. In January 1945, threeattempts by German armored units to relieve the trapped garrison failed, and onFebruary 13, 1945, Budapestfell to the Red Army. The Soviets thencontinued their advance across Hungary. In early March 1945, Hitler launchedOperation Spring Awakening, aimed at protecting the Lake Balaton oil fields insouthwestern Hungary, whichwas one of Germany’slast remaining sources of crude oil. Through intelligence gathering, the Soviets became aware of the plan,and foiled the offensive, and then counter-attacked, forcing the remainingGerman forces in Hungaryto withdraw across the Austrian border.

The Germans then hastened to construct defense lines in Austria, which officially was an integral partof Germanysince the Anschluss of 1938. In earlyApril 1945, Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed the border from Hungary into Austria,meeting only light opposition in its advance toward Vienna. Only undermanned German forces defended the Austrian capital, which fellon April 13, 1945. Although some fiercefighting occurred, Vienna was spared thewidespread destruction suffered by Budapestthrough the efforts of the anti-Nazi Austrian resistance movement, whichassisted the Red Army’s entry into the city. A provisional government for Austria was set up comprising acoalition of conservatives, democrats, socialists, and communists, which gainedthe approval of Stalin, who earlier had planned to install a pro-Sovietgovernment regime from exiled Austrian communists. The Red Army continued advancing across otherparts of Austria,with the Germans still holding large sections of regions in the west and south.By early May 1945, French, British, and American troops had crossed into Austria from the west, which together with theSoviets, would lead to the four-power Allied occupation (as in post-war Germany) of Austria after the war.