Daniel Orr's Blog, page 3

December 10, 2024

December 10, 1963 – Zanzibar gains independence; a violent revolution begins one month later

On January 12, 1964, Zanzibar,a country of small islands located just east of the African mainland experiencedan armed revolution that overthrew the ruling parliamentary monarchy andestablished a socialist government. Therevolution took place just over a month after December 10, 1963, when Britain ended its protectorate and granted Zanzibar fullindependence under Zanzibari Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah. Sultan Abdullah’s family had ruledpre-British Zanzibarthrough a long line of dynastic succession dating back to 1698.

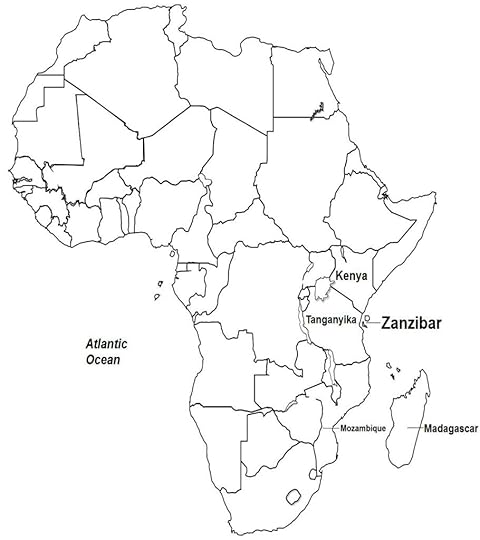

Location of Zanzibar shown.

Location of Zanzibar shown.(Taken from Zanzibar Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background InJuly 1963, legislative elections in Zanzibarhad given the Arab Zanzibari political coalition, led by the ZanzibarNationalist Party (ZNP), a majority in parliament. The main opposition party, the blackAfrican-dominated Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP) had won fewer seats in theelections, despite garnering 54% of the popular vote. The ASP had accused the government ofcarrying out electoral fraud to ensure the ZNP’s victory. As a result, violence broke out that caused anumber of civilian deaths.

Zanzibari society was religiously homogenous, with 99% ofthe population belonging to the Islamic faith. The country had three major ethnic groups: black Africans and mixedAfrican-Persians (called Shirazi), both groups numbering 230,000 persons andcomprising 76% of the population; ethnic Arabs at 50,000 or 17% of thepopulation, and ethnic Indians at 20,000 or 6% of the population.

Traditionally, Zanzibarwas stratified into three economic groups: ethnic Arabs, who owned vast tractsof agricultural lands; ethnic Indians, who dominated the business sector astraders and merchants; and the indigenous Africans, who comprised the greatmajority of the laborers and farm workers. However, many exceptions had developed over time, e.g. the majority ofnew Arab immigrants to Zanzibarwere poor, and some black Zanzibaris became wealthy landowners.

A few weeks after Zanzibargained its independence, rumors arose that the outlawed communist Umma Partywas planning to overthrow the government and was secretly bringing in weaponsto the island. The Zanzibari sultanasked Britain for militaryassistance, but the British government, which had already withdrawn Britishtroops from Zanzibar,denied the request. Zanzibar’s defense thus was left to theisland’s small police force.

Revolution Earlyin the morning of January 12, 1964, in Zanzibar’smain island of Unguja(also more commonly called Zanzibar, Map 20),hundreds of fanatical fighters belonging to the Afro-Shirazi Youth led by JohnOkello, attacked police stations and seized armories outside Zanzibar’scapital of Stone Town. Now possessing firearms, the rebels proceeded to Stone Town,where they overwhelmed more police units and took control of governmentbuildings, public utilities, and the city’s radio station. Within a few hours, the rebellion had gainedthe support of the vast majority of the general population. Scores of local civilians took up arms and joinedthe rebels in defeating the remaining government forces. Just nine hours after the uprising began, therebels had gained full control of the capital. Zanzibar’sgovernment collapsed, and the sultan and his Cabinet fled into exile abroad.

Okello called on the ASP’s leader, Abeid Karume, to form anew government. The ASP and the UmmaParty formed a ruling revolutionary council that was led by Karume, who alsobecame Zanzibar’sfirst president. Karume’s governmentrenamed the country the “People’s Republic of Zanzibarand Pemba”, and abolished the ZanzibarSultanate and banned the deposed Sultan Abdullah from returning. Free politics ceased as the state-run ASPbecame the sole legal party that was allowed to operate.

A complete overhaul of Zanzibari society took place with thegovernment’s implementation of sweeping social and economic reforms. Lands owned by ethnic Arabs were seized aswere businesses owned by ethnic Indians. The seized assets were handed out to black Zanzibaris. Virtually overnight, Arab and Indiandomination of Zanzibari society vanished completely.

After the rebels had seized Stone Town’sradio station at the height of the revolution, Okello went on the air andbroadcast inflammatory speeches urging the civilian population to carry outviolence. Okello claimed to hold themilitary rank of a “Field Marshall” and greatly exaggerated his feats in therevolution as they were transpiring.

As a consequence of Okello’s broadcasts, in the days thatfollowed, the Zanzibari countryside became scenes of violence as armed bandsdescended on Arab and Indian settlements and killed whole families, destroyedhouses, and seized lands and properties. Dramatic scenes of this event were captured in the documentary AfricaAddio, produced by an Italian film crew that was coincidentally working in Zanzibar at thattime. Filmed from an aircraft in flight,the documentary shows scenes of many dead people on the ground, piled up deadbodies at the back of dump trucks traveling down the road, long lines of peoplebeing led away by armed guards, and people attempting to flee the island aboardpacked dinghies. The human death tollfrom the violence has not been determined exactly, and is given by varioussources as from a few thousands to several thousands.

December 9, 2024

December 9, 1987 – Start of the First Intifada in the Gaza Strip and West Bank

On December 6, 1987, an Israeli citizen was murdered in Gaza. Two days later, four Palestinian residents ofthe Jabaliya refugee camp in Gazawere killed in a road accident by a truck belonging to the Israeli Army. Many residents of the Jabaliya camp took tothe streets in protest, believing that the four Palestinians were killeddeliberately in reprisal for the Gazamurder. Israeli security forces moved into disperse the crowd, but in the process, opened fire and killed aprotester. Demonstrations then broke outin other refugee camps in Gaza and the West Bank, triggering a full-blown uprising.

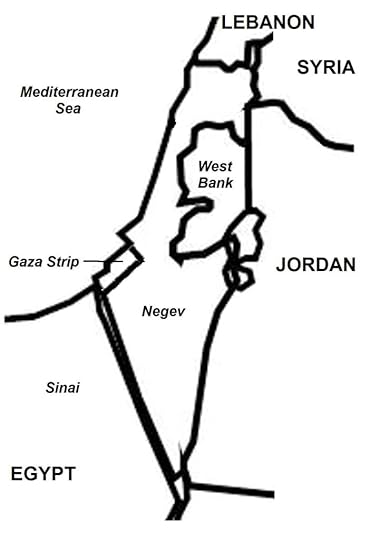

Map showing location of Gaza and West Bank.

Map showing location of Gaza and West Bank.The 1987 Palestinian uprising is more commonly known as theFirst Intifada, where the word “intifada” is Arabic that means “to shake off”,and has come to denote an uprising or rebellion. The 1987 Intifada initially took the form ofspontaneous, disorganized street rallies and demonstrations consisting of tensof thousands of Palestinians who incited anarchy and clashed with Israelisecurity forces. Youths and minors oftenformed the front lines, leading Israeli authorities to accuse the Palestiniansof using the children as “human shields”. The protesters lobbied stones and Molotov cocktails (home-madeincendiary bombs) at the police, burned tires, and set up road blocks andbarricades. Militancy increased when theprotesters began using firearms and grenades as weapons. Other Palestinians supported the intifadathrough non-violent means, such as not paying taxes, boycotting Israeliproducts, and undertaking other forms of civil disobedience.

The depth and speed of the intifada surprised Israeliauthorities, who believed that the actions were being planned and carried outby the PLO. In fact, each local protestaction was organized by community leaders in response to and in support ofother uprisings that were already taking place, creating a snowballeffect. Eventually, however, theintifada came under the centralized command of the Unified National Leadershipof the Uprising (UNLU), an alliance of PLO factions in the occupiedterritories, which began to carry out more organized militant actions. Two other Palestinian armed groups, Hamas andIslamic Jihad, also rose to prominence during the intifada and emerged as thepolitical and military rivals to the PLO.

(Taken from Palestinian Uprising of 1987 – 1993 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background As aconsequence of the 1947-48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and the 1948Arab-Israeli War, some 700,000 Palestinian Arabs lost their homes and becamerefugees. Most of them eventuallysettled in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. The Palestinian Jews emerged victorious, inthe process establishing the state of Israel. Then with the Israeli Army’s victory in theSix-Day War in 1967 (separate article), the Israelis gained control of Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. Israel imposed militarized authority over the“occupied territories” (as the Gaza Strip, West Bank, and East Jerusalem were called collectively) as a means to deteropposition. Check points and road blockswere raised, searches and arrests conducted, and civilian movement curtailedand monitored. Perceived enemies wereeliminated, imprisoned, or deported. Furthermore, the Israeli government encouraged its citizens to migrateto the occupied territories, where Israeli housing settlements soon began toemerge.

The Palestinians greatly resented the presence of theIsraelis, whom they regarded as a foreign force occupying Palestinianland. Furthermore, as the Israeliauthority became established and greater numbers of Israeli settlements werebeing built, the Palestinians believed that their lands eventually would beintegrated into Israel. The Israeli occupation was also perceived asa serious blow to the Palestinian people’s aspirations for establishing aPalestinian state.

The Palestinian Liberation Organization, or PLO, a politicaland armed movement, was formed in 1964 and was headed by Chairman Yasser Arafatto lead the Palestinians’ struggle for independence. However, the PLO experienced many setbacks,not only in the hands of Israelbut also by the Arab countries to which the Palestinians had turned forsupport. In 1970, the PLO was expelledfrom Jordan and thereaftermoved to Lebanonwhere, in 1982, it also was forced to leave. Subsequently, the PLO moved its headquarters to Tunisia, whose distant locationprevented the Palestinian leadership from exercising direct control andinfluence over the affairs of Palestinians in the occupied territories. The PLO itself was wracked by internaldissent among some factions that opposed Arafat, who had cast aside hishard-line stance against Israeland adopted a more conciliatory approach.

Furthermore, later developments in the Middle East boded ill for the Palestinians. Egypt,the militarily strongest Arab country and a main supporter of the PLO, hadsigned a peace treaty with Israelin 1979 and ceased its claim to the Gaza Strip. Jordan had not onlyexpelled the PLO but had relinquished its claim to the West Bank and consequently stripped the Palestinian residents there ofJordanian citizenship. Syria, another major backer of the PLO, had afalling out with Arafat during the 1982 Lebanon War and began to support arival PLO faction that ultimately forced Arafat and his Fatah faction to leave Lebanona second time. For so long, the Arabcountries’ regional security concerns centered on the Palestinians’ strugglefor statehood. In the 1980s, however,much of the concentration was on the Iran-Iraq War, relegating the Palestinianissue to a lesser focus. Palestiniansbelieved that many Arab countries, because of the Arab military defeats to theIsraelis, generally had abandoned active support for the Palestinians’ nationalistaspirations.

The Palestinians’ frustrations were compounded by direeconomic circumstances in the West Bank and Gaza. Nearly half of all Palestinians were poor and lived in refugee camps incramped, squalid, and poorly serviced conditions. Unemployment was high and so was thePalestinians’ birth rate, leading to more people competing for limitedopportunities and resources.

Ever since the Israelis took over the occupied territories,tensions between Israelis and Palestinians persisted, which often erupted inviolence. Then during the second half of1987, these tensions rose dramatically, ultimately leading to a majorPalestinian uprising that was triggered by the following events.

December 8, 2024

December 8, 1936 – Anastacio Somoza is elected president of Nicaragua, starting a dictatorship and dynastic reign of over four decades

On December 8, 1936, Anastacio Somoza was elected president of Nicaragua, winning an implausible 99.83% of the votes. Somoza then ruled the country as a dictator or through figureheads under his control, and gained all aspects of government. Over time, he accumulated massive wealth and owned the biggest landholdings in the country. His many personal and family businesses extended into the shipping and airlines industries, agricultural plantations and cattle ranches, sugar mills, and wine manufacturing. President Somoza took bribes from foreign corporations which he had granted mining concessions in the country, and also benefited from local illicit operations such as unregistered gambling, organized prostitution, and illegal wine production.

Nicaragua in Central America.

Nicaragua in Central America.President Somoza suppressed all forms of opposition with theuse of the National Guard, Nicaragua’spolice force, which had turned the country into a militarized state. President Somoza was staunchly anti-communistand received strong military and financial support from the United States, which was willing to take Nicaragua’srepressive government as an ally in the ongoing Cold War.

Somoza’s rise to power began in 1933 as Director of the National Guard. He had ordered the assassination of left-wing nationalist Augusto Sandino who had waged a long guerrilla war against the Nicaraguan government, and United States Marines which had occupied the country since 1912. Thereafter, Somoza’s power and influence grew, leading to his deposing President Juan Batista Sacasa in June 1936 and installing a puppet head of state leading up to his own election as president in December 1936.

(Taken from United States Occupation of Nicaragua, 1912- 1933 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background Inmany instances, Nicaragua’s political troubles prompted American intervention,such as those that occurred in 1847, 1894, 1896, 1898, and 1899, when U.S. forceswere landed in that Central American country. These occupations were brief, with American troops withdrawing onceorder had been restored, although U.S. Navy ships kept a permanent watchthroughout the Central American coastline. The officially stated reasons given by the United States for intervening in Nicaraguawas to protect American lives and American commercial interests in Central America. In some cases, however, the Americans wanted to give a decided advantageto one side of Nicaragua’spolitical conflict.

In 1912, the United Statesagain intervened in Nicaragua,starting an occupation of the country that would last for over two decades andwould leave a deep impact on the local population. The origin of the 1912 American occupationtraces back to the early 1900s when Nicaragua,then led by the Liberals, offered the construction of the NicaraguaCanal to Germanyand Japan. The NicaraguaCanal was planned to be a shippingwaterway that connects the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean through the Caribbean Sea.

The Liberals wanted less American involvement in Nicaragua’sinternal affairs and therefore offered the waterway’s construction to othercountries. Furthermore, the United States had decided to forgo its originalplan to build the Nicaragua Canal in favor of completing the partly-finished Panama Canal (which had been abandoned by a Frenchconstruction firm).

For the United States,however, the idea of another foreign power in the Western Hemisphere wasanathema, as the U.S.government believed it had the exclusive rights to the region. The American policy of exclusivity in theWestern Hemisphere was known as the Monroe Doctrine, set forth in 1823 byformer U.S.president James Monroe. Furthermore, theUnited States believed that Nicaragua had ambitions in Central America and therefore viewed that country as a potential source ofa wider conflict. U.S.-Nicaraguanrelations deteriorated when two American saboteurs were executed by theNicaraguan government. Consequently, theUnited States broke offdiplomatic relations with Nicaragua.

In October 1909, Nicaraguan Conservatives, backed by someLiberals, carried out a rebellion against the government. The United States threw its supportbehind the rebels. Then when therebellion spread, the United Statessent warships to Nicaraguaand subsequently, in December 1909, landed troops in Corinto and Bluefields(Map 23). More American forces arrivedin May 1910.

In August 1910, Nicaragua’s ruling governmentcollapsed, replaced by a U.S.-friendly administration consisting ofConservatives and Liberals. The United States bought out Nicaragua’slarge foreign debt that had accumulated during the long period ofinstability. Consequently, Nicaragua owed the United States the amount of thatdebt, while the Americans’ stake was raised in that troubled country.

Then in 1912, Nicaragua’s ruling coalition brokedown, sparking a civil war between the government and another alliance ofLiberals and Conservatives. As therebels gained ground and began to threaten Managua,Nicaragua’s capital, the United Stateslanded troops in Corinto, Bluefields, and San Juan del Sur. At its peak, the U.S.troop deployment in Nicaraguatotaled over 2,300 soldiers. Within amonth of the deployment, in October 1912, the American troops, supported byNicaraguan government forces, had defeated the rebels.

The United Statestightened its control of Nicaraguain August 1914 when both countries signed an agreement whereby the Americansgained exclusive rights to construct the Nicaragua Canal,as well as to establish military bases to protect it. The U.S.-Nicaragua treaty mostly served as adeterrent against other foreign involvement in Nicaragua,since by this time, the Americans already were operating the Panama Canal nearby.

The U.S. Army’s presence in Nicaragua from 1912 to 1925 broughtpeace in that Central American country. At the Nicaraguan government’s request, the U.S. Army helped to organizeNicaragua’s armed forces and police forces (collectively called the NationalGuard) to eliminate the many private militias and other armed groups that localpoliticians were using to advance their personal interests. After the National Guard was formed, the United States withdrew its forces from Nicaragua. Nine months later, however, in-fighting amongConservatives led to the overthrow of the incumbent president, again promptingthe United States toredeploy its military forces in Nicaraguato stop the disturbance from spreading.

Peace and order was restored once more, and a new Conservativegovernment came to power. TheConservatives’ authority was challenged by the Liberals, however, who formedtheir own government. Fighting soonbroke out between the rival political parties, which rapidly escalated into acivil war. Once more, the United Statesintervened and restored peace after threatening to use military force againstthe Liberals. In the peace treaty thatfollowed, the Conservatives and Liberals agreed to two stipulations: that theConservative government would complete its term of office before new electionswere held; and that all remaining private militias and armed groups would bedisbanded and subsequently incorporated into the government forces to form anexpanded, non-partisan National Guard.

December 7, 2024

December 7, 1939 – World War II: Finnish forces ambush a Soviet Army battalion

Under the night darkness on December 7, 1939, Finnish skitroops ambushed a bivouacked Soviet battalion, killing all the soldiers. The next day, the Finns again swept down onand annihilated another camped Russian unit. More attacks continued in the next several days, and Soviet reconnaissanceplanes were unable to spot the Finnish units concealed in the snow-coveredforests. In these battles, Sovietcasualties totaled 4,000 killed and 5,000 wounded against some 2,000 Finnishsoldiers killed.

Finland and nearby countries.

Finland and nearby countries.In similar circumstances, in the Battle of the Mottis,Finnish ski units succeeded in cutting communication and supply lines amongindividual units of the Soviet 168th Division that were spread out along thenorthern shore of Lake Ladoga. The Finns attacked individual Russian pockets(called “mottis” by the Finns) in a mobile siege strategy. Faced with disaster by a severed supply line,in mid-January 1940, the Russians tried to break out by attacking in force,only to be cut down by heavy Finnish machinegun fire. Some 3,000 Russians were killed, while 8 ofthe 11 mottis were overwhelmed.

(Taken from Winter War – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background In1932, Finland also signed anon-aggression pact with the Soviet Union,which was extended to ten years in 1934. Even so, relations between Finlandand the Soviet Union remained detached, even guarded, not least because ofideological differences and the lingering suspicion generated by the FinnishCivil War where the Soviets had supported the Red Guards, and Germany theWhite Guards. Finlanddistrusted the Soviets, particularly since the latter harbored and supportedthe exiled Finnish communist movement, while the Soviet Union regarded the ruling right-wing conservative Finnishgovernment as fascist and reactionary.

While officially neutral, Finland appeared to be pro-German,because of German assistance during the Finnish Civil War, which raised Sovietsuspicions. Soviet mistrust wasfurthered by a number of events: in 1937, when a German naval flotilla arrivedin Helsinki, in 1938, when Finland held celebrations honoring German supportduring the civil war, and in 1939, when Franz Halder, the German Army chief ofstaff, arrived in Helsinki.

Soviet pressure on Finland for territorial concessionshad begun in April 1938, the secret negotiations continuing intermittentlyuntil the summer of 1939, with no agreement being reached because of strongFinnish opposition. In June 1939,following the visit of high-level German military officials to Finland, Stalinwas convinced that not only was a Soviet-German war imminent, but that Germanforces would use Finland as a springboard to attack the Soviet Union.

But the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact quelled Stalin’s concernsand seemingly gave assurance that the Germans would not interfere in Finland. Thus, the Soviets increased their pressure onthe Finnish government, in October 1939 releasing the following demands: thatthe Finnish-Soviet border along the Karelian Isthmus be moved west to a point20 miles east of Viipuri; that Finnish fortifications in the Karelian Isthmusbe dismantled; that Finland cede to the Soviet Union the islands in the Gulf ofFinland, the Kalastajansaarento (Rybachi) Peninsula in the Barents Sea, and theSalla area; and that Hanko be leased for 30 years to the Soviet Union, where aRussian military base would be built. Inreturn, the Soviets would cede to Finland Repola and Porajarvi from EasternKarelia, a territory whose size of 3,400 square kilometers was twice as largeas those demanded from Finland.

For Stalin, the Soviet-Finnish negotiations must address thesecurity guarantees for Leningrad,since the city was located just 20 miles from the Finnish border and withinfiring range of Finnish heavy artillery. Stalin wanted to adjust the border here further to the west into Finland, withthe ceded territory serving as a buffer zone between the two nations. However, the Finnish government saw theseterritorial demands as the first step to an eventual Soviet take-over of Finland. On October 6 and 10, the Finnish governmentissued a call-up of reserves and effectively conducted a general mobilization,fearing that the Soviet demands would be tantamount to Finland meeting the samefate as the Balkan States. Thenegotiations, though conducted openly, were characterized by great mutualdistrust: the Finns believing that the Soviet offer was merely a first step togobble up Finland, and theSoviets who believed that Finlandwould side with Germanyin a future war.

The Finns presented a counter-offer, agreeing to cedeterritory in the Karelian Isthmus that would double the distance of the Finnishborder to Leningrad. But by then, Stalin was in no mood for moretalks and was determined to use armed force, deciding that the Finns werenegotiating in bad faith.

December 6, 2024

December 6, 1987 – Palestinian Uprising of 1987 – 1993: An Israeli citizen is murdered in Gaza; two days later , two Palestinians are killed

On December 6, 1987, an Israeli citizen was murdered in Gaza. Two days later, four Palestinian residents ofthe Jabaliya refugee camp in Gazawere killed in a road accident by a truck belonging to the Israeli Army. Many residents of the Jabaliya camp took tothe streets in protest, believing that the four Palestinians were killeddeliberately in reprisal for the Gazamurder. Israeli security forces moved into disperse the crowd, but in the process, opened fire and killed aprotester. Demonstrations then broke outin other refugee camps in Gaza and the West Bank, triggering a full-blown uprising.

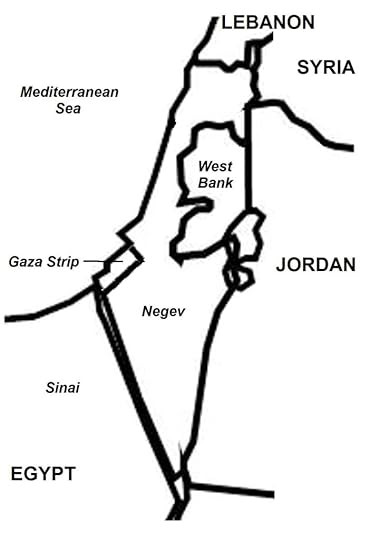

Map showing location of Gaza and the West Bank.

Map showing location of Gaza and the West Bank.The 1987 Palestinian uprising is more commonly known as theFirst Intifada, where the word “intifada” is Arabic that means “to shake off”,and has come to denote an uprising or rebellion. The 1987 Intifada initially took the form ofspontaneous, disorganized street rallies and demonstrations consisting of tensof thousands of Palestinians who incited anarchy and clashed with Israelisecurity forces. Youths and minors oftenformed the front lines, leading Israeli authorities to accuse the Palestiniansof using the children as “human shields”. The protesters lobbied stones and Molotov cocktails (home-madeincendiary bombs) at the police, burned tires, and set up road blocks andbarricades. Militancy increased when theprotesters began using firearms and grenades as weapons. Other Palestinians supported the intifadathrough non-violent means, such as not paying taxes, boycotting Israeliproducts, and undertaking other forms of civil disobedience.

The depth and speed of the intifada surprised Israeliauthorities, who believed that the actions were being planned and carried outby the PLO. In fact, each local protestaction was organized by community leaders in response to and in support ofother uprisings that were already taking place, creating a snowball effect. Eventually, however, the intifada came underthe centralized command of the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising(UNLU), an alliance of PLO factions in the occupied territories, which began tocarry out more organized militant actions. Two other Palestinian armed groups, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, also roseto prominence during the intifada and emerged as the political and militaryrivals to the PLO.

(Taken from Palestinian Uprising of 1987 – 1993 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background As aconsequence of the 1947-48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and the 1948Arab-Israeli War, some 700,000 Palestinian Arabs lost their homes and becamerefugees. Most of them eventuallysettled in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. The Palestinian Jews emerged victorious, inthe process establishing the state of Israel. Then with the Israeli Army’s victory in theSix-Day War in 1967 (separate article), the Israelis gained control of Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. Israel imposed militarized authority over the“occupied territories” (as the Gaza Strip, West Bank, and East Jerusalem were called collectively) as a means to deteropposition. Check points and road blockswere raised, searches and arrests conducted, and civilian movement curtailedand monitored. Perceived enemies wereeliminated, imprisoned, or deported. Furthermore, the Israeli government encouraged its citizens to migrateto the occupied territories, where Israeli housing settlements soon began toemerge.

The Palestinians greatly resented the presence of theIsraelis, whom they regarded as a foreign force occupying Palestinianland. Furthermore, as the Israeliauthority became established and greater numbers of Israeli settlements werebeing built, the Palestinians believed that their lands eventually would beintegrated into Israel. The Israeli occupation was also perceived asa serious blow to the Palestinian people’s aspirations for establishing aPalestinian state.

The Palestinian Liberation Organization, or PLO, a politicaland armed movement, was formed in 1964 and was headed by Chairman Yasser Arafatto lead the Palestinians’ struggle for independence. However, the PLO experienced many setbacks,not only in the hands of Israelbut also by the Arab countries to which the Palestinians had turned forsupport. In 1970, the PLO was expelledfrom Jordan and thereaftermoved to Lebanonwhere, in 1982, it also was forced to leave. Subsequently, the PLO moved its headquarters to Tunisia, whosedistant location prevented the Palestinian leadership from exercising directcontrol and influence over the affairs of Palestinians in the occupiedterritories. The PLO itself was wrackedby internal dissent among some factions that opposed Arafat, who had cast asidehis hard-line stance against Israeland adopted a more conciliatory approach.

Furthermore, later developments in the Middle East boded ill for the Palestinians. Egypt,the militarily strongest Arab country and a main supporter of the PLO, hadsigned a peace treaty with Israelin 1979 and ceased its claim to the Gaza Strip. Jordan had not onlyexpelled the PLO but had relinquished its claim to the West Bank and consequently stripped the Palestinian residents there ofJordanian citizenship. Syria, another major backer of the PLO, had afalling out with Arafat during the 1982 Lebanon War and began to support arival PLO faction that ultimately forced Arafat and his Fatah faction to leave Lebanon asecond time. For so long, the Arabcountries’ regional security concerns centered on the Palestinians’ strugglefor statehood. In the 1980s, however,much of the concentration was on the Iran-Iraq War, relegating the Palestinianissue to a lesser focus. Palestiniansbelieved that many Arab countries, because of the Arab military defeats to theIsraelis, generally had abandoned active support for the Palestinians’nationalist aspirations.

The Palestinians’ frustrations were compounded by direeconomic circumstances in the West Bank and Gaza. Nearly half of all Palestinians were poor and lived in refugee camps incramped, squalid, and poorly serviced conditions. Unemployment was high and so was thePalestinians’ birth rate, leading to more people competing for limitedopportunities and resources.

Ever since the Israelis took over the occupied territories,tensions between Israelis and Palestinians persisted, which often erupted inviolence. Then during the second half of1987, these tensions rose dramatically, ultimately leading to a majorPalestinian uprising that was triggered by the following events.

December 5, 2024

December 5, 1983 – Dirty War: Military rule ends in Argentina

On December 5, 1983, military junta rule by the National Reorganization Process (Spanish: Proceso de Reorganización Nacional) ended in Argentina. A succession of juntas had ruled with authoritarian powers since 1976 after the military seized power by ousting President Isabel Peron (wife of former President Juan Peron) in a coup.

(Taken from Dirty War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

The military’s stated reason for the Peron coup was toprevent the communist take-over of the country. Thereafter, a military junta came to power. Argentina’s legislature wasabolished, while the judicial courts were restructured to suit the newmilitarized system. The academic andintelligentsia were suppressed, as were labor and peoples’ assemblies. The military government instituted harshmeasures to stamp out communist and leftist elements. Also targeted by the military were oppositionpoliticians, journalists, writers, labor and student leaders, including theirsupporters and sympathizers.

Argentina and nearby countries. During the Dirty War, the Argentine military government used “dirty” methods in its anti-insurgency campaign to stamp out leftist and perceived communist elements in the country.

Argentina and nearby countries. During the Dirty War, the Argentine military government used “dirty” methods in its anti-insurgency campaign to stamp out leftist and perceived communist elements in the country.The military operated with impunity, arbitrarily subjectingtheir suspected enemies to arrests, interrogations, tortures, andexecutions. One infamous method of executionwas the “death flight”, where prisoners were drugged, stripped naked, and helddown with weights on their feet, and then boarded onto a plane and later thrownout into the Atlantic Ocean. Since death flights and other forms ofexecutions made certain that the bodies would not be found, the victims weresaid to have disappeared, striking great fear among the people. Another atrocity was allowing capturedpregnant women to give birth and then killing them, with their babies given tothe care of and adopted by military or right-leaning couples. The military and Triple A death squadscarried out these operations clandestinely during the Dirty War.

The military government’s anti-insurgency campaign was sofierce, sustained, and effective that by 1977, the leftist and communist groupshad practically ceased to exist. Hundreds of rebels, who had escaped to the nearby countries of Brazil, Uruguay,Paraguay, Bolivia, and Chile,were arrested and returned to Argentina. The United States provided technicalassistance to the integrated intelligence network of these countries within thescope of its larger struggle against communism in the Cold War.

The Argentinean government continued its draconian rule evenafter it had stamped out the insurgency. The Dirty War caused some 9,000 confirmed and up to 30,000 unconfirmedvictims from murders and forced disappearances. By 1982, however, the military’s anti-insurgency campaign, which hadfound wide popular support initially, was being criticized by the people becauseof high-level government corruption and a floundering national economy.

Seeking to revitalize its flagging image, the militarygovernment launched an invasion of the British-controlled Falkland Islands in an attempt to stir up nationalist sentiments and therebyregain the Argentinean people’s support. The Argentinean forces briefly gained control of the islands. A British naval task force soon arrived,however, and recaptured the Falkland Islands,driving away and inflicting heavy casualties on the Argentinean forces.

Consequently, Argentina’s military governmentcollapsed, ending the country’s militarized climate. Argentina then began to transitionto civilian rule under a democratic system. After the country held general elections in 1983, the new governmentthat came to power opened a commission to investigate the crimes committedduring the Dirty War. Subsequently, anumber of perpetrators were brought to trial and convicted. Some military units broke out in rebellion inprotest of the convictions, forcing the Argentinean government to pass new lawsthat reduced the military’s liability during the Dirty War. In 1989, a broad amnesty was given to allpersons who had been involved, indicted, and even convicted of crimes duringthe Dirty War.

In June 2005, however, the Argentinean Supreme Courtoverturned the amnesty laws, allowing for the re-opening of criminal lawsuitsfor Dirty War crimes. The fates of manypersons killed and disappeared, as well as the infants taken from theirmurdered mothers, remain unsolved and are subject to ongoing investigations.

December 4, 2024

December 4, 1920 – Russian forces capture the Armenian capital of Yerevan

Armenia was dealt a death blow when Soviet Russia, on the pretext of a border dispute, invaded from Azerbaijan. On December 4, 1920, Yerevan fell to the Russians, and those parts not yet under Turkish occupation came under their control. Armenian communists then formed a new government, bringing the country under indirect Soviet political authority. The Russian invasion of Armenia was part of the Moscow government’s strategy to bring the Caucasus under Soviet Russia, a plan that was achieved when Georgia also was invaded the following year.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Turkish nationalists fought in three fronts: in the eastagainst Armenia, in thesouth against France and the French Armenian Legion, and in the west against Greece, which was backed by Britain.

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres.

Partition of Anatolia as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres.Eastern Front Alsoknown as the Turkish-Armenian War, the eastern front carried over fromhostilities in the Caucasus Sector of World War I. Russian forces had gained control of theCaucasus and northeast Turkey,but withdrew from the region in 1917 following the outbreak of the RussianRevolution. Later that year, theOttomans and the Soviet government signed an armistice.

The Eastern front in the Turkish War of Independence.

The Eastern front in the Turkish War of Independence.After the Russians withdrew, the South Caucasusjurisdictions of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan formed the short-livedTranscaucasian Democratic Federative Republic in February 1918. Then after the federation’s dissolution inMay 1918, the three members declared separate independences. Armenia,which in the context of World War I supported the Allied Powers, went to waragainst the Ottoman Empire. The nascent Armenian state was dealt a numberof defeats from a powerful Ottoman offensive, but survived the war.

At the end of World War I, United States President Woodrow Wilson, in line with his “Fourteen Points”Manifesto regarding the peoples’ right of self-determination, proposed a new,much enlarged Armenian state, subject to certain conditions. This so-called “Wilsonian Armenia” subsequentlywas included in the Treaty of Sevres. While ethnic Armenians welcomed the proposal as genuinely reflectinghistorical and geographical Armenian territory, the Turkish “government” in Ankara opposed it on thesame grounds that the proposed change would encroach on the Turkish people’s traditionaland ancestral homeland.

War Following border skirmishes in June 1920, Armeniantroops seized Oltu, a coal-rich town in Georgia. Turkish forces associated with Kemal’sgovernment had a strong presence in eastern Turkey. By contrast, Armenia’s prospects for victorywas dependent on Allied support which, however, proved to be limited in supplyand weak-hearted, which ultimately decided the outcome in this sector of thewar.

Turkish forces began their offensive on September 13, easilyoverrunning the towns of Oltu and Peniak. On September 28, the border town of Sarikamiswas taken as well, forcing Armenian forces to retreat to Kars,a fortified city in western Armenia. On October 24, 1920, Turkish forces entered Armenia and attacked Kars, which was taken after one week offighting.

The Turks then rapidly advanced to Alexandropol, 280kilometers away, which also was captured, on November 6. Yerevan,the Armenian capital, now came under direct threat. On November 18, 1920, the Armenian governmentacquiesced to a Turkish ultimatum, and a ceasefire came into effect. On December 2, 1920, the Armenian and Ankara governments signed the Treaty of Alexandropol,whereby Armeniaceased its claim to “Wilsonian Armenia” as stipulated in the Treaty of Sevres. The Alexandropol treaty also forced Armenia to cede Karsand surrounding regions; in total, some 50% of Armenian territory was lost,i.e. Armeniaretained only one-half of its pre-war borders.

The Armenian state was dealt a death blow when the SovietUnion, on the pretext of a border dispute, invaded from Azerbaijan. On December 4, 1920, Yerevan fell to the Russians, and those partsnot yet under Turkish occupation came under Soviet control. Armenian communists then formed a newgovernment, bringing the country under indirect Soviet politicalauthority. The Soviet invasion of Armenia was part of the Moscowgovernment’s strategy to bring the Caucasus under the Soviet Union, a plan thatwas achieved when Georgiaalso was invaded by the Russians the following year.

In the aftermath, the Ankaragovernment and the Soviet Union made peace andfixed the Turkish-Soviet border under two treaties: the Treaty of Moscow (March16, 1921) and the Treaty of Kars (October 13, 1921); the treaties also endedthe war in the eastern sector.

December 3, 2024

December 3, 1971 – Pakistan launches pre-emptive air strikes against India, starting the Indian-Pakistani War of 1971 and merging it with the Bangladesh War of Independence

India’sinvolvement in East Pakistan was condemned in West Pakistan, where war sentiment was running high by November1971. On November 23, Pakistan declared a state of emergency anddeployed large numbers of troops to the East Pakistani and West Pakistaniborders with India. Then on December 3, 1971, Pakistani planeslaunched air strikes on air bases in India,particularly those in Jammu and Kashmir, Indian Punjab, and Haryana.

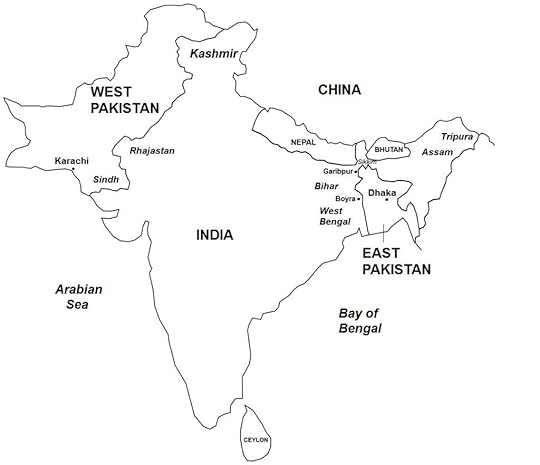

Bangladesh War of Independence and Indian-Pakistani War of 1971

Bangladesh War of Independence and Indian-Pakistani War of 1971 The next day, Indiadeclared war on Pakistan. India held a decisive militaryadvantage, which would allow its armed forces to win the war in only 13days. Indiahad a 4:1 and 10:1 advantage over West Pakistan and East Pakistan, respectively, in terms of numbers of aircraft, allowingthe Indians to gain mastery of the sky by the second day of the war.

India’sobjective in the war was to achieve a rapid victory in East Pakistan before theUN imposed a ceasefire, and to hold off a possible Pakistani offensive from West Pakistan. Inturn, Pakistan hoped to holdout in East Pakistan as long as possible, and to attack and make territorialgains in western India,which would allow the Pakistani government to negotiate in a superior positionif the war went to mediation.

(Taken from Bangladesh War of Independence and Indian-Pakistani War of 1971 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background TheBangladesh War of Independence began as a civilian uprising in East Pakistanthat escalated into a civil war between East Pakistan and West Pakistan. Indiaintervened in the civil war, sparking the Indian-Pakistani War of 1971. In the aftermath of the two wars, EastPakistan broke away from Pakistanand formed the new state of Bangladesh.

In 1947, the Indian subcontinent was partitioned (previousarticle) into two new countries (Map 13): the Hindu-majority India and thenearly exclusive Muslim Pakistan. Muchof India was formed from thesubcontinent’s central and eastern regions, while Pakistancomprised two geographically separate regions that became West Pakistan(located in the northwest) and East Pakistan(located in the southeast).

From its inception, Pakistanexperienced a great disparity between West Pakistan and East Pakistan. The nationalcapital was located in West Pakistan, fromwhere all major political and governmental decisions were made. Military and foreign policies emanated fromthere as well. West Pakistan also held a monopoly on the country’s financial,industrial, and social affairs. Much ofthe country’s wealth entered, remained in, and was apportioned to theWest. These factors resulted in WestPakistan being much wealthier than East Pakistan. And all this despite East Pakistan having ahigher population than West Pakistan.

In the 1960s, East Pakistancalled for social and economic reforms and greater regional autonomy, but wasignored by the national government. Thenin 1970, the Amawi League, East Pakistan’s main political party, won a stunninglandslide victory in the national elections, but was prevented from taking overthe government by the ruling civilian-military coalition regime, which fearedthat a new civilian government would reduce the military’s influence on thecountry’s political affairs.

Leaders from East Pakistan and West Pakistan tried to negotiate a solution to the political impasse,but failed to reach an agreement. Havingbeen prevented from forming a new government, Mujibur Rahman, East Pakistan’s leader, called on East Pakistanis to carry out acts ofcivil disobedience.

In Dhaka, the EastPakistani capital, thousands of residents undertook mass demonstrations thatparalyzed commercial, public, and civilian functions. On March 25, 1971, the Pakistani Armyarrested and jailed Mujibur, who then declared while in prison the secession ofEast Pakistan from Pakistanand the founding of the independent state of Bangladesh. Mujibur’s supporters aired the declaration ofindependence on broadcast radio throughout East Pakistan.

East Pakistanis then organized the Mukti Bahini, a guerillamilitia whose ranks were filled by ethnic Bengali soldiers who had defectedfrom the Pakistani Army. As armed clashesbegan to break out in Dhaka, the national government sent more troops to East Pakistan. Much of the fighting took place in April-May 1971, where governmentforces prevailed, forcing the rebels to flee to the Indian states of West Bengal and Tripura. The Pakistani Army then turned on the civilian population to weed outnationalists and rebel supporters. Thesoldiers targeted all sectors of society – the upper classes of the political,academic, and business elite, as well as the lower classes consisting of urbanand rural workers, farmers, and villagers. In the wave of violence and suppression that took place, tens ofthousands of East Pakistanis were killed, while some ten million civilians fledto the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Assam, Bihar,and Meghalaya.

As East Pakistani refugees flooded into India, theIndian government called on the United Nations (UN) to intervene, but receivedno satisfactory response. As nearly 50%of the refugees were Hindus, to the Indian government, this meant that thecauses of the unrest in East Pakistan werereligious as well as political. (Duringthe partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, a massive cross-bordermigration of Hindus and Muslims had taken place; by the 1970s, however, EastPakistan, still contained a significant 14% Hindu population.)

Since its independence, Indiahad fought two wars against Pakistanand faced the perennial threat of fighting against or being attackedsimultaneously from East Pakistan and West Pakistan. Indiatherefore saw that the crisis in East Pakistan yielded one benefit – if thethreat from East Pakistan was eliminated, India would not have to face thethreat of a war on two fronts. Thus,just two days into the uprising in East Pakistan,India began to secretlysupport the independence of Bangladesh. The Indian Army covertly trained, armed, andfunded the East Pakistani rebels, which within a few months, grew to a force of100,000 fighters.

December 2, 2024

December 2, 1956 – Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and his men arrive at Playa Las Coloradas in southeastern Cuba

On December 2, 1956, Fidel Castro and his men arrived insoutheastern Cuba,with their vessel hitting a sandbar close to the mangrove shoreline of PlayaLas Coloradas. The Cuban military,having recently increased its operations in the region because of the recentM-26-7 attacks, spotted the landing and fired on the Granma. Fidel Castro and his men made it to shore,but were forced to abandon most of their weapons and supplies still on boardthe vessel. While making their way tothe Sierra Maestra Mountains,they were ambushed on December 5 by a large army contingent. Eventually, less than 20 of the original 82rebels met up deep in the forested highlands; the survivors included thegroup’s leaders Fidel and Raul Castro, Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos, whilemost of the rebels had been killed or captured.

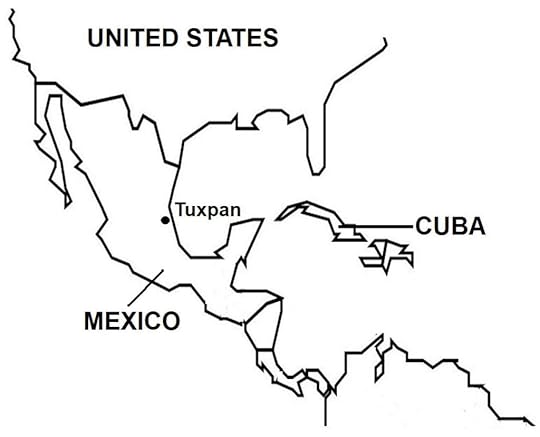

In November 1956, Fidel Castro and 81 other rebels set out from Tuxpan, Mexico aboard a decrepit yacht for their nearly 2,000 kilometer trip across the Caribbean Sea bound for south-eastern Cuba.

In November 1956, Fidel Castro and 81 other rebels set out from Tuxpan, Mexico aboard a decrepit yacht for their nearly 2,000 kilometer trip across the Caribbean Sea bound for south-eastern Cuba.Fidel Castro soon established his headquarters in the SierraMaestra, and in the following months, launched attacks against army patrols andisolated outposts, and on government and public infrastructures, therebygaining control of much of the mountainous region and later expanding therevolution’s “liberated zones”. Heincreased the size of his force by recruiting from nearby villages and fromurban volunteers who were drawn to his cause. The revolution was boosted greatly by the “escopeteros”, localsupporters who served many auxiliary roles: as armed irregulars to the M-26-7main force, as informants providing the positions and movements of army units,and as porters carrying supplies across the mountains.

(Taken from Cuban Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background InMarch 1952, General Fulgencio Batista seized power in Cuba through a coup d’état. He then canceled the elections scheduled forJune 1952, where he was running for the presidency but trailed in the polls andfaced likely defeat. Having gainedpower, General Batista established a dictatorship, suppressed the opposition,and suspended the constitution and many civil liberties. Then in the November 1954 general electionsthat were boycotted by the political opposition, General Batista won the presidencyand thus became Cuba’sofficial head of state.

President Batista favored a close working relationship with Cuba’s wealthy elite, particularly with Americanbusinesses, which had an established, dominating presence in Cuba. Since the early twentieth century, the UnitedStates had maintained political, economic, and military control over Cuba; e.g.during the first few decades of the 1900s, U.S. forces often interveneddirectly in Cuba by quelling unrest and violence, and restoring politicalorder.

American corporations held a monopoly on the Cuban economy,dominating the production and commercial trade of the island’s main export,sugar, as well as other agricultural products, the mining and petroleumindustries, and public utilities. The United Statesnaturally entered into political, economic, and military alliances with andbacked the Cuban government; in the context of the Cold War, successive Cubangovernments after World War II were anti-communist and staunchly pro-American.

President Batista expanded the businesses of the Americanmafia in Cuba, where thesecriminal organizations built and operated racetracks, casinos, nightclubs, andhotels in Havanawith relaxed tax laws provided by the Cuban government. President Batista amassed a large personalfortune from these transactions, and Havanawas transformed into and became internationally known for its red-lightdistrict, where gambling, prostitution, and illegal drugs were rampant. President Batista’s regime was characterizedby widespread corruption, as public officials and the police benefitted frombribes from the American crime syndicates as well as from outright embezzlementof government funds.

Cubadid achieve consistently high economic growth under President Batista, but muchof the wealth was concentrated in the upper class, and a great divide existedbetween the small, wealthy elite and the masses of the urban poor and landlesspeasants. (Cuban society also containeda relatively dynamic middle class that included doctors, lawyers, and manyother working professionals.)

President Batista was extremely unpopular among the generalpopulation, because he had gained power through force and made unequal economicpolicies. As a result, Havana(Cuba’scapital) seethed with discontent, with street demonstrations, protests, and riotsoccurring frequently. In response,President Batista deployed security forces to suppress dissenting elements,particularly those that advocated Marxist ideology. The government’s secret police regularlycarried out extrajudicial executions and forced disappearances, as well asarbitrary arrests, detentions, and tortures. Some 20,000 persons were killed or disappeared during the Batistaregime.

In 1953, a young lawyer and former student leader namedFidel Castro emerged to lead what ultimately would be the most seriouschallenge to President Batista. Castropreviously had taken part in the aborted overthrow of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujilloand in the 1948 civil disturbance (known as “Bogotazo”) in Bogota,Colombia before completinghis law studies at the University of Havana. Castro had run as an independent for Congressin the 1952 elections that were cancelled because of Batista’s coup. Castro was infuriated and began makingpreparations to overthrow what he declared was the illegitimate Batista regimethat had seized power from a democratically elected government. Fidel organized an armed insurgent group,“The Movement”, whose aim was to overthrow President Batista. At its peak, “The Movement” would comprise1,200 members in its civilian and military wings.

December 1, 2024

December 1, 1944 – Greek Civil War: The Greek government issues a directive requiring resistance groups to disarm and demobilize

By the fall of 1944, the Soviet Army had broken through in Eastern Europe. Toavoid being cut off, in October of that year, the Germans (who, by this time,were the remaining occupation forces in Greece) retreated north. With the Germans out of Greece, the British soon arrived in Athens, followed by PrimeMinister Papandreou’s government which began to take over the administrativeduties left behind by the fallen collaborationist regime.

One month earlier, the various armed resistance groups hadagreed to subordinate their militias under the command of the BritishArmy. An alliance of Greek communist andleftis resistance groups called EAM-ELAS controlled much of Greece but wantedto preserve Allied unity and therefore did not pre-empt the British byoccupying and taking over Athens, although it was capable of doing so.

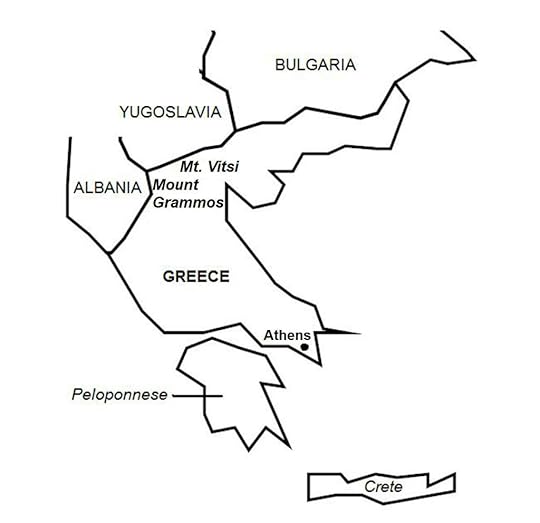

On December 1, 1944, the Athens government issued a directiverequiring all resistance groups and militias (with a few exceptions) to disarmand demobilize. EAM-ELAS refused, andthe six EAM representatives resigned their positions in the unity government. EAM called for a mass assembly, which wascarried out by some 200,000 EAM supporters in Athens on December 3. As the crowd traversed parts of the downtownarea, gunfire erupted. In the ensuingtumult, some 28 persons were killed and 148 were injured.

Large-scale fighting then broke out in Athens, which led toa six-week battle known in Greece as the “Dekemvriata” (English: DecemberEvents), between the Greek government, supported by British forces, andEAM-ELAS. Initially, EAM-ELAS held theinitiative as they controlled large sections of Athens. The arrival of many British reinforcements, however, turned the tide ofbattle and EAM-ELAS soon was driven out of the capital.

(Taken from Greek Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background TheGreek Civil War has its origin in World War II, in April 1941 when the AxisPowers of Germany, Italy,and Bulgaria invaded andoverrun Greeceand defeated and expelled the Greek and British forces. Greece’sKing George II and the Greek government fled to exile in Britain-controlled Egypt, where they set up a government-in-exilein Cairo. In Greece,the Axis partitioned the country into zones of occupation and set up acollaborationist government in Athens.

Organized resistance to the occupation began in July 1941when officers and members of the Greek Communist Party, or KKE (Greektransliteration: Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas), many of whom had been jailed byGreece’s right-wing military government before the war but had escapedfollowing the Axis invasion, secretly met and formed a unified “popular front”to fight the occupation forces and collaborationist government. This idea bore fruit when in September 1941,the KKE and three other leftist organizations formed the National LiberationFront, or EAM (Greek transliteration: Ethniko Apeleftherotiko Metopo), whoseaims were to liberate Greece,and to advance “the Greek people’s sovereign right to determine its form ofgovernment”.

In February 1942, EAM formed an armed wing, the GreekPeople’s Liberation Army, or ELAS (Greek transliteration: Ellinikós LaïkósApeleftherotikós Stratós), which carried out guerilla and sabotage operationsagainst the Axis forces and collaborationist government. Success in the battlefield allowed EAM-ELASto gain control of the Greek countryside and mountain areas, drawing activesupport from the rural population (communist and non-communists), and allowingthe resistance to grow to 50,000 fighters and 500,000 non-combatauxiliaries. Perhaps as much asthree-quarters of Greek territory came under EAM-ELAS control, although themajor urban areas, including Athens,continued to be held by the Axis.

Other resistance movements (all advocating non-communistideologies) also operated during the occupation, with the two major of thesebeing the National Republican Greek League, or EDES (Greek transliteration:Ethnikos Dimokratikos Ellinikos Syndesmos, abbreviated) and the National andSocial Liberation, or EKKA (Greek transliteration: Ethniki kai KoinonikiApeleftherosis). These groups had muchsmaller militias and were less military capable of confronting the enemy thanwas EAM-ELAS. Britain provided technical andmaterial support to all Greek resistance groups, including EAM-ELAS, whosecommunist ideology were at odds with the British.

The Greek resistance groups were hostile to each other, andskirmishes broke out among them as did they against the Axisforces/collaborationist militias. TheBritish and EAM-ELAS also were wary of each other with regards to post-war Greece and thecountry’s political future. This mutualdistrust initially was set aside because of the need to fight a common enemy,but gradually increased toward war’s end when the Axis defeat became certain.

The British were concerned that EAM-ELAS, with its overtlypro-Soviet inclination, would prevail in the war and transform post-war Greece into a Marxist state aligned with the Soviet Union. Forthe British, a communist country in the Mediterranean Sea, especially one thatpotentially would allow a Soviet maritime presence through a naval agreement orthe use of ports would threaten the Suez Canal, Britain’s vital link to Indiaand other British colonies in Asia. Britain was determined that King George IIshould return to Greece,which would guarantee the formation of a conservative government friendly toBritish interests.

Because of its multi-party, multi-ideology origins, EAM-ELASofficially promoted a democratic policy. However, since it was dominated by the KKE (comprising the largestconstituent organization), EAM-ELAS was formed and functioned along communistlines. EAM-ELAS also was firmly opposedto the return of Greece’sgovernment-in-exile, because of fears of a return to the pre-war right-wing(i.e. repressive) regime, as well as to the return of the king, who hadsupported that regime.

In March 1944, EAM established a quasi-government called thePolitical Committee of National Liberation, or PEEA (Greek transliteration:Politiki Epitropi Ethikis Apeleftherosis), commonly known as the “MountainGovernment”. The PEEA held legislativeelections where women, for the first time in Greece, were allowed to vote. The rebel government called for continuingthe resistance against the occupation, “destruction of fascism”, and theindependence and sovereignty of Greece.

In April 1944, a mutiny broke out in Egypt among soldiers of the exiled Greek ArmedForces, who declared that the government-in-exile was irrelevant and needed tobe replaced by a new, progressive government that genuinely represented thechanges taking place in Greece. British authorities quelled the mutiny, andjailed the soldiers.

The mutiny, however, led to the end of thegovernment-in-exile. In May 1944, underBritish sponsorship, representatives from the various Greek political partiesand resistance groups met and held talks in Beirut, Lebanon. These talks, called the Lebanon Conference,led to the formation of a coalition government (called the government ofnational unity) led by Prime Minister Georgios Papandreou. Of the 24 posts in the new government, 6 wereallocated to EAM. The conference alsoagreed that King George’s return to Greece would be postponed andsubject to a referendum that would decide the fate of the monarchy.