Daniel Orr's Blog, page 5

November 19, 2024

November 19, 1942 – World War II: Soviet forces trap German 6th Army at Stalingrad

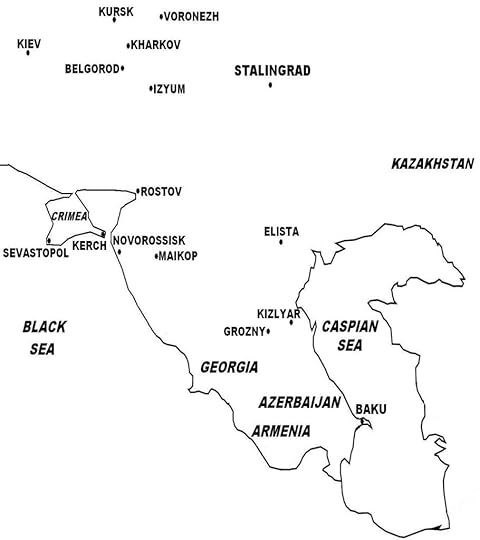

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet Red Army launched OperationUranus, which led to the encirclement of German 6th Army in Stalingrad. Unbeknown to the Germans, in the previous months,the Soviet High Command had been sending large numbers of Red Army formationsto the north and southeast of Stalingrad. While only intending to use these units insporadic counter-attacks in support of Stalingrad, by November 1942, Stalin andhis top generals had reorganized these forces for a major counter-offensivecodenamed Operation Uranus involving an enormous force of 1.1 million troops,1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,300 planes, aimed at cutting offand encircling German 6th Army and units of 7th Panzer Army in Stalingrad. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler ignored the warning of his general staff, as by now he wasfirmly set on taking Stalingrad at all costs.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet High Command launchedOperation Uranus, a double envelopment maneuver, with the Soviet SouthwesternFront attacking the Axis northern flank held by the Romanian 3rd Army. The next day, the Soviet Stalingrad Frontthrust from the south of the Axis flank, with the brunt of the attack fallingon Romanian 4th Army. The two Romanian Armies, lacking sufficient anti-tankweapons and supported only with 100 obsolete tanks, were overwhelmed by sheernumbers, and on November 22, the two arms of the Soviet pincers linked up atKalach. German 6th Army, elements of 4thPanzer Army, and remnants of the Romanian armies, comprising some250,000-300,000 troops, were trapped in a giant pocket in Stalingrad.

Case Blue (German: Fall Blau) was the operational codename for Fuhrer Directive no. 41, issued on April 5, 1941, where Hitler laid out the plan for the German Army’s 1942 summer offensive in Russia, as follows: Army Group South would advance to the Caucasus, this operation being Case Blue’s main objective; Army Group North would capture Leningrad; and Army Group Center would take a defensive posture and hold its present position.

Case Blue (German: Fall Blau) was the operational codename for Fuhrer Directive no. 41, issued on April 5, 1941, where Hitler laid out the plan for the German Army’s 1942 summer offensive in Russia, as follows: Army Group South would advance to the Caucasus, this operation being Case Blue’s main objective; Army Group North would capture Leningrad; and Army Group Center would take a defensive posture and hold its present position.

(Taken from Battle of Stalingrad – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Meanwhile to the north, German Army Group B, tasked withcapturing Stalingrad and securing the Volga, began its advance to the Don River on July 23, 1942. The German advance was stalled by fierceresistance, as the delays of the previous weeks had allowed the Soviets tofortify their defenses. By then, theGerman intent was clear to Stalin and the Soviet High Command, which thenreorganized Red Army forces in the Stalingradsector and rushed reinforcements to the defense of the Don. Not only was German Army Group B delayed bythe Soviets that had began to launch counter-attacks in the Axis’ northernflank (which were held by Italian and Hungarian armies), but also byover-extended supply lines and poor road conditions.

On August 10, 1942, German 6th Army had moved to the westbank of the Don, although strong Soviet resistance persisted in the north. On August 22, German forces establishedbridgeheads across the Don, which was crossed the next day, with panzers andmobile spearheads advancing across the remaining 36 miles of flat plains to Stalingrad. OnAugust 23, German 14th Panzer Division reached the VolgaRiver north of Stalingradand fought off Soviet counter-attacks, while the Luftwaffe began a bombingblitz of the city that would continue through to the height of the battle, whenmost of the buildings would be destroyed and the city turned to rubble.

On August 29, 1942, two Soviet armies (the 62nd and 64th)barely escaped being encircled by the German 4th Panzer Army and armored unitsof German 6th Army, both escaping to Stalingrad and ensuring that the battlefor the city would be long, bloody, and difficult.

On September 12, 1942, German forces entered Stalingrad, starting what would be a four-month longbattle. From mid-September to earlyNovember, the Germans, confident of victory, launched three major attacks tooverwhelm all resistance, which gradually pushed back the Soviets east towardthe banks of the Volga.

By contrast, the Soviets suffered from low morale, but werecompelled to fight, since they had no option to retreat beyond the Volga because of Stalin’s “Not one step back!”order. Stalin also (initially) refusedto allow civilians to be evacuated, stating that “soldiers fight better for analive city than for a dead one”. Hewould later allow civilian evacuation after being advised by his top generals.

Soviet artillery from across the Volgaand cross-river attempts to bring in Red Army reinforcements were suppressed bythe Luftwaffe, which controlled the sky over the battlefield. Even then, Soviet troops and suppliescontinued to reach Stalingrad, enough to keepup resistance. The ruins of the cityturned into a great defensive asset, as Soviet troops cleverly used the rubbleand battered buildings as concealed strong points, traps, and killingzones. To negate the Germans’ airsuperiority, Red Army units were ordered to keep the fighting lines close tothe Germans, to deter the Luftwaffe from attacking and inadvertently causingfriendly fire casualties to its own forces.

The battle for Stalingradturned into one of history’s fiercest, harshest, and bloodiest struggles forsurvival, the intense close-quarter combat being fought building-to-buildingand floor-to-floor, and in cellars and basements, and even in the sewers. Surprise encounters in such close distancessometimes turned into hand-to-hand combat using knives and bayonets.

By mid-November 1942, the Germans controlled 90% of thecity, and had pushed back the Soviets to a small pocket with four shallowbridgeheads some 200 yards from the Volga. By then, most of German 6th Army was lockedin combat in the city, while its outer flanks had become dangerouslyvulnerable, as they were protected only by the weak armies of its Axispartners, the Romanians, Italians, and Hungarians. Two weeks earlier, Hitler, believingStalingrad’s capture was assured, redeployed a large part of the Luftwaffe tothe fighting in North Africa.

Unbeknown to the Germans, in the previous months, the SovietHigh Command had been sending large numbers of Red Army formations to the northand southeast of Stalingrad. While only intending to use these units insporadic counter-attacks in support of Stalingrad, by November 1942, Stalin andhis top generals had reorganized these forces for a major counter-offensivecodenamed Operation Uranus involving an enormous force of 1.1 million troops,1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,300 planes, aimed at cutting offand encircling German 6th Army and units of 7th Panzer Army in Stalingrad. German intelligence had detected the Sovietbuildup, but Hitler ignored the warning of his general staff, as by now he wasfirmly set on taking Stalingrad at all costs.

On November 19, 1942, the Soviet High Command launchedOperation Uranus, a double envelopment maneuver, with the Soviet SouthwesternFront attacking the Axis northern flank held by the Romanian 3rd Army. The next day, the Soviet Stalingrad Frontthrust from the south of the Axis flank, with the brunt of the attack fallingon Romanian 4th Army. The two Romanian Armies, lacking sufficient anti-tankweapons and supported only with 100 obsolete tanks, were overwhelmed by sheernumbers, and on November 22, the two arms of the Soviet pincers linked up atKalach. German 6th Army, elements of 4thPanzer Army, and remnants of the Romanian armies, comprising some250,000-300,000 troops, were trapped in a giant pocket in Stalingrad.

The German High Command asked Hitler to allow the trappedforces to make a break out, which was refused. Also on many occasions, General Friedrich Paulus, commander of German6th Army, made similar appeals to Hitler, but was turned down. Instead, on November 24, 1942, Hitler advisedGeneral Paulus to hold his position at Stalingraduntil reinforcements could be sent or a new German offensive could break theencirclement. In the meantime, thetrapped forces would be supplied from the air. Hitler had been assured by Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering that the 700tons/day required at Stalingrad could bedelivered with German transport planes. However, the Luftwaffe was unable to deliver the needed amount, despitethe addition of more transports for the operation, and the trapped forces in Stalingrad soon experienced dwindling supplies of food,medical supplies, and ammunition. With theonset of winter and the temperature dropping to –30°C (–22°F), an increasingnumber of Axis troops, yet without adequate winter clothing, suffered fromfrostbite. At this time also, the Sovietair force had began to achieve technological and combat parity with theLuftwaffe, challenging it for control of the skies and shooting down increasingnumbers of German planes.

Meanwhile, the Red Army strengthened the cordon aroundStalingrad, and launched a series of attacks that slowly pushed the trappedforces to an ever-shrinking perimeter in an area just west of Stalingrad.

In early December 1942, General Erich von Manstein,commander of the newly formed German Army Group Don, which was tasked withsecuring the gap between German Army Groups A and B, was ready to launch arelief operation to Stalingrad. Began on December 12 under Operation WinterStorm, German Army Group Don succeeded in punching a hold in the Soviet ringand advanced rapidly, pushing aside surprised Red Army units, and came towithin 30 miles of Stalingrad on December 19. Through an officer that was sent to Stalingrad,General Manstein asked General Paulus to make a break out towards Army GroupDon; he also sent communication to Hitler to allow the trapped forces to breakout. Hitler and General Paulus bothrefused. General Paulus cited the lackof trucks and fuel and the poor state of his troops to attempt a break out, andthat his continued hold on Stalingrad would tie down large numbers of Soviet forceswhich would allow German Army Group A to retreat from the Caucasus.

On December 23, 1942, Manstein canceled the relief operationand withdrew his forces behind German lines, forced to do so by the threat ofbeing encircled by Soviet forces that meanwhile had launched Operation LittleSaturn. Operation Little Saturn was amodification of the more ambitious Operation Saturn, which aimed to trap GermanArmy Group A in the Caucasus, but was rapidly readjusted to counter GeneralManstein’s surprise offensive to Stalingrad. But Operation Little Saturn, the Sovietencirclement of Stalingrad, and the trapped Axis forces so unnerved Hitler thaton his orders, German Army Group A hastily withdrew from the Caucasusin late December 1942. German 17th Armywould continue to hold onto the Taman Peninsula in the Black Sea coast, and planned to usethis as a jump-off point for a possible future second attempt to invade the Caucasus.

Meanwhile in Stalingrad, byearly January 1943, the situation for the trapped German forces grewdesperate. On January 10, the Red Armylaunched a major attack to finally eliminate the Stalingradpocket after its demand to surrender was rejected by General Paulus. On January 25, the Soviets captured the lastGerman airfield at Stalingrad, and despite theLuftwaffe now resorting to air-dropping supplies, the trapped forces ran low onfood and ammunition.

With the battle for Stalingradlost, on January 31, 1943, Hitler promoted General Paulus to the rank of FieldMarshal, hinting that the latter should take his own life rather than becaptured. Instead, on February 2,General Paulus surrendered to the Red Army, along with his trapped forces,which by now numbered only 110,000 troops. Casualties on both sides in the battle of Stalingrad, one of thebloodiest in history, are staggering, with the Axis losing 850,000 troops, 500tanks, 6,000 artillery pieces, and 900 planes; and the Soviets losing 1.1million troops, 4,300 tanks, 15,000 artillery pieces, and 2,800 planes. The German debacle at Stalingrad andwithdrawal from the Caucasus effectively endedCase Blue, and like Operation Barbarossa in the previous year, resulted inanother German failure.

November 18, 2024

November 18, 1991 – Croatian War of Independence: Vukovar falls to Yugoslav forces

On August 25, 1991, some 36,000 troops of the Yugoslav Army,aided by Serb paramilitaries, launched an attack against the light-armed 1,800Croatian National Guard fighters in Vukovar in eastern Croatia.Supported by air, armor, and artillery units, the Yugoslav-Serb forces brokethrough on November 18, 1991 after an 87-day siege and battle. Vukovar wassubjected to intense shell and rocket bombardment and was completely destroyed.For the Yugoslav Army, the battle was won at great cost, incurring 1,100 killedand 2,500 wounded, including the loss of 110 tanks and armoured vehicles and 3planes. Croatian casualties were 900 killed and 800 wounded. Some 1,100civilians also perished.

In the aftermath, several hundred Croatian soldiers andcivilians were executed, and 20,000 residents comprising the non-Serbpopulation were expelled from the town. Vukovar was thereafter annexed into theself-declared Republic of Serbian Krajina.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.(Taken from Croatian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background By the late 1980s, Yugoslavia was faced with a major political crisis, as separatist aspirations among its ethnic populations threatened to undermine the country’s integrity (see “Yugoslavia”, separate article). Nationalism particularly was strong in Croatia and Slovenia, the two westernmost and wealthiest Yugoslav republics. In January 1990, delegates from Slovenia and Croatia walked out from an assembly of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country’s communist party, over disagreements with their Serbian counterparts regarding proposed reforms to the party and the central government. Then in the first multi-party elections in Croatia held in April and May 1990, Franjo Tudjman became president after running a campaign that promised greater autonomy for Croatia and a reduced political union with Yugoslavia.

Ethnic Croatians, who comprised 78% of Croatia’s population, overwhelmingly supportedTudjman, because they were concerned that Yugoslavia’snational government gradually had fallen under the control of Serbia, Yugoslavia’s largest and mostpowerful republic, and led by hard-line President Slobodan Milosevic. In May 1990, a new Croatian Parliament wasformed and subsequently prepared a new constitution. The constitution was subsequently passed inDecember 1990. Then in a referendum heldin May 1991 with Croatian Serbs refusing to participate, Croatians voted overwhelminglyin support of independence. On June 25,1991, Croatia, together withSlovenia,declared independence.

Croatian Serbs (ethnic Serbs who are native to Croatia) numbered nearly 600,000, or 12% of Croatia’stotal population, and formed the second largest ethnic group in therepublic. As Croatiaincreasingly drifted toward political separation from Yugoslavia, the Croatian Serbsbecame alarmed at the thought that the new Croatian government would carry outpersecutions, even a genocidal pogrom against Serbs, just as the pro-Naziultra-nationalist Croatian Ustashe government had done to the Serbs, Jews, andGypsies during World War II. As aresult, Croatian Serbs began to militarize, with the formation of militias aswell as the arrival of armed groups from Serbia.

Croatian Serbs formed a population majority in south-west Croatia(northern Dalmatian and Lika). There, inFebruary 1990, they formed the Serb Democratic Party, which aimed for thepolitical and territorial integration of Serb-dominated lands in Croatia with Serbiaand Yugoslavia. They declared that if Croatia wanted to secede from Yugoslavia, they, in turn, should be allowed toseparate from Croatia. Serbs also interpreted the change in theirstatus in the new Croatian constitution as diminishing their civil rights. In turn, the Croatian government opposed theCroatian Serb secession and was determined to keep the republic’s territorialintegrity.

In July 1990, a Croatian Serb Assembly was formed thatcalled for Serbian sovereignty and autonomy. In December, Croatian Serbs established the SAO Krajina (SAO is the acronymfor Serbian Autonomous Oblast) as a separate government from Croatia in the regions of northern Dalmatia and Lika. Croatian Serbs formed a majority population in two other regions in Croatia, which they also transformed intoseparate political administrations called SAO Western Slavonia, and SAO EasternSlavonia (officially SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western Syrmia). (Map 17 showslocations in Croatiawhere ethnic Serbs formed a majority population.) In a referendum held inAugust 1990 in SAO Krajina, Croatian Serbs voted overwhelmingly (99.7%) forSerbian “sovereignty and autonomy”. Thenafter a second referendum held in March 1991 where Croatian Serbs votedunanimously (99.8%) to merge SAO Krajina with Serbia, the Krajina governmentdeclared that “… SAO Krajina is a constitutive part of the unified stateterritory of the Republic of Serbia”.

November 17, 2024

November 17, 1970 – Vietnam War: 14 U.S. officers, including Lt. William Calley, are indicted by a court-martial for the My Lai Massacre

On November 17, 1970, U.S. Army Lt. William Calley went on court-martial trial for the My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War. He was one of 14 officers charged for the crime. In March 1971, Lt. Calley was the only officer found guilty of murdering 22 villagers and was handed down a life sentence. He was also the only one of 26 men (officers and men) who was convicted. In August 1971, his sentence was reduced to twenty years. In September 1974, he was paroled by the U.S. Army after having served three and one-half years under house arrest in a military base.

The My Lai Massacre occurred on March 16, 1968 when a U.S. Army Company descended on the hamlets of My Lai and My Khe (located in Son My Village in Quang Ngai Province) and killed some 350 to 500 civilians (men, women, children, and infants). The incident has been described as “the most shocking episode of the Vietnam War”.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Before the Cambodian Campaign began, President Nixon hadannounced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S. ground troops to theoperation. Within days, largedemonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in the United States,with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio,National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four peopleand wounding eight others. This incidentsparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across thecountry. Anti-war sentiment already wasintense in the United Statesfollowing news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My LaiMassacre, where U.S. troopson a search and destroy mission descended on My Laiand My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including womenand children.

American public outrage further was fueled when in June1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officiallytitled: United States– Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense),a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked tothe press. The Pentagon Papers showedthat successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower,and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times misled theAmerican people regarding U.S.involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stopthe document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. SupremeCourt subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publicationcontinued, and which was also later taken up by the Washington Post and othernewspapers.

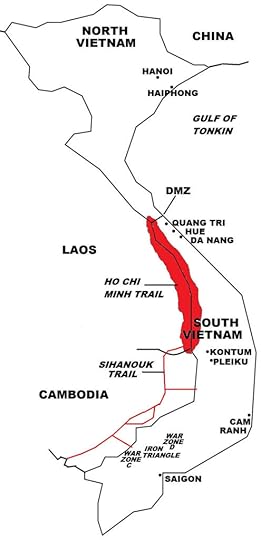

As in Cambodia,the U.S. high command hadlong desired to launch an offensive into Laos to cut off the logisticalportion of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system located there. But restrained by Laos’ official neutrality,the U.S. military instead carried out secret bombing campaigns in eastern Laosand intelligence gathering operations (the latter conducted by the top-secretMilitary Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, MACV-SOGthat involved units from Special Forces, Navy SEALS, U.S. Marines, U.S. AirForce, and CIA) there.

The success of the Cambodian Campaign encouraged PresidentNixon to authorize a similar ground operation into Laos. But as U.S. Congress had prohibited Americanground troops from entering Laos,South Vietnamese forces would launch the offensive into Laos with the objective of destroying the Ho ChiMinh Trail, with U.S. forcesonly playing a supporting role (and remaining within the confines of South Vietnam). The operation also would gauge the combatcapability of the South Vietnamese Army in the ongoing Vietnamization program.

In February-March 1971, about 17,000 troops of the South VietnameseArmy, (some of whom were transported by U.S.helicopters in the largest air assault operation of the war), and supported by U.S. air and artillery firepower, launchedOperation Lam Son 719 into southeastern Laos. At their furthest extent, the SouthVietnamese seized and briefly held Tchepone village, a strategic logistical hubof the Ho Chi Minh Trail located 25 miles west of the South Vietnameseborder. The main South Vietnamese columnwas stopped by heavy enemy resistance and poor road conditions at A Luoi, some15 miles from the border. NorthVietnamese forces, initially distracted by U.S. diversionary attackselsewhere, soon assembled 50,000 troops against the South Vietnamese, andcounterattacked. North Vietnameseartillery particularly was devastating, knocking out several South Vietnamesefirebases, while intense anti-aircraft fire disrupted U.S. air transport operations. By early March 1971, the attack was calledoff, and with the North Vietnamese intensifying their artillery bombardment,the South Vietnamese withdrawal turned into a chaotic retreat and a desperatestruggle for survival. The operation wasa debacle, with the South Vietnamese losing up to 8,000 soldiers killed, 60% oftheir tanks, 50% of their armored carriers, and dozens of artillery pieces;North Vietnamese casualties were 2,000 killed. American planes were sent to destroy abandoned South Vietnamese armor,transports, and equipment to prevent their capture by the enemy. U.S. air losses were substantial:84 planes destroyed and 430 damaged and 168 helicopters destroyed and 618damaged.

Buoyed by this success, in March 1972, North Vietnam launched the Nguyen Hue Offensive(called the Easter Offensive in the West), its first full-scale offensive into South Vietnam,using 300,000 troops and 300 tanks and armored vehicles. By this time, South Vietnamese forces carriedpractically all of the fighting, as fewer than 10,000 U.S. troops remained in South Vietnam, and who were soonscheduled to leave. North Vietnameseforces advanced along three fronts. Inthe northern front, the North Vietnamese attacked through the DMZ, and capturedthe northern provinces, and threatened Hue and Da Nang. In late June 1972, a South Vietnamesecounterattack, supported by U.S.air firepower, including B-52 bombers, recaptured most of the occupiedterritory, including Quang Tri, near the northern border. In the Central Highlands front, the NorthVietnamese objective to advance right through to coastal Qui Nhon and split South Vietnamin two, failed to break through to Kontum and was pushed back. In the southern front, North Vietnameseforces that advanced from the Cambodian border took Tay Ninh and Loc Ninh, butwere repulsed at An Loc because of strong South Vietnamese resistance andmassive U.S.air firepower.

To further break up the North Vietnamese offensive, in April1972, U.S. planes including B-52 bombers under Operation Freedom Train,launched bombing attacks mostly between the 17th and 19th parallels in NorthVietnam, targeting military installations, air defense systems, power plantsand industrial sites, supply depots, fuel storage facilities, and roads,bridges, and railroad tracks. In May1972, the bombing attack was stepped up with Operation Linebacker, whereAmerican planes now attacked targets across North Vietnam. A few days earlier, U.S. planes air-dropped thousands of naval minesoff the North Vietnamese coast, sealing off North Vietnam from sea traffic.

At the end of the Easter Offensive in October 1972, NorthVietnamese losses included up to 130,000 soldiers killed, missing, or woundedand 700 tanks destroyed. However, NorthVietnamese forces succeeded in capturing and holding about 50% of theterritories of South Vietnam’snorthern provinces of Quang Tri, Thua Thien,Quang Nam,and Quang Tin, as well as the western edges of II Corps and III Corps. But the immense destruction caused by U.S. bombing in North Vietnam forced the latter to agree to make concessions atthe Paris peacetalks.

At the height of North Vietnam’sEaster Offensive, the Cold War took a dramatic turn when in February 1972,President Nixon visited Chinaand met with Chairman Mao Zedong. Thenin May 1972, President Nixon also visited the Soviet Unionand met with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders. A period of superpower détente followed. Chinaand the Soviet Union, desiring to maintain their newly established friendlyrelations with the United States,aside from issuing diplomatic protests, were not overly provoked by the massiveU.S. bombing of North Vietnam. Even then, the two communist powers stood bytheir North Vietnamese ally and continued to send large amounts of militarysupport.

November 16, 2024

November 16, 1912 – First Balkan War: Start of the Battle of Bitola between Serbian and Ottoman forces

On November 16, 1912, Serbian forces pushed into Bitola, starting anintense three-day battle during the First Balkan War. The Ottomans were defeated, and forced toabandon the whole the province and retreat to the Berat region in centralAlbania, as well as to the fortress city of Ioannina, which was then undersiege by the Greek Army.

The Serbians then advanced toward Albania,taking most of the region north of Vlora and into the AdriaticCoast, thereby achieving Serbia’s ambition of gaining access to the Mediterranean Sea. Montenegrin forces also occupied a section ofnorthern Albania, andadvanced to the fortified city of Shkoder,where they began a siege on October 28, 1912 that would last for severalmonths.

(Taken from First Balkan War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

The Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainland was Rumelia, a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace, to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast.

The Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainland was Rumelia, a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace, to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast. Background At the start of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empire was a spent force, a shadow of its former power of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that had struck fear in Europe. The empire did continue to hold vast territories, but only tolerated by competing interests among the European powers who wanted to maintain a balance of power in Europe. In particular, Britain and France supported and sometimes intervened on the side of the Ottomans in order to restrain expansionist ambitions of the emerging giant, the Russian Empire.

In Europe, the Ottomans hadlost large areas of the Balkans, and all of its possessions in central andcentral eastern Europe. By 1910, Serbia, Bulgaria,Montenegro, and Greecehad gained their independence. As aresult, the Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainlandwas Rumelia (Map 4), a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace,to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast. And even Rumelia itself was coveted by thenew Balkan states, as it contained large ethnic populations of Serbians,Belgians, and Greeks, each wanting to merge with their mother countries.

The Russian Empire, seeking to bring the Balkans into itssphere of influence, formed a military alliance with fellow Slavic Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. In March 1912, a Russian initiative led to aSerbian-Bulgarian alliance called the Balkan League. In May 1912, Greece joined the alliance when theBulgarian and Greek governments signed a similar agreement. Later that year, Montenegrojoined as well, signing separate treaties with Bulgariaand Serbia.

The Balkan League was envisioned as an all-Slavic alliance,but Bulgaria saw the need tobring in Greece, inparticular the modern Greek Navy, which could exert control in the Aegean Seaand neutralize Ottoman power in the Mediterranean Sea,once fighting began. The Balkan Leaguebelieved that it could achieve an easy victory over the Ottoman Empire, for the following reasons. First, the Ottomans currently were locked in a war with the ItalianEmpire in Tripolitania (part of present-day Libya), and were losing; andsecond, because of this war, the Ottoman political leadership was internallydivided and had suffered a number of coups.

Most of the major European powers, and especially Austria-Hungary, objected to the Balkan Leagueand regarded it as an initiative of the Russian Empire to allow the RussianNavy to have access to the Mediterranean Sea through the Adriatic Coast. Landlocked Serbiaalso had ambitions on Bosnia and Herzegovinain order to gain a maritime outlet through the AdriaticCoast, but was frustrated when Austria-Hungary, which had occupiedOttoman-owned Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1878, formally annexed theregion in 1908.

The Ottomans soon discovered the invasion plan and preparedfor war as well. By August 1912,increasing tensions in Rumelia indicated an imminent outbreak of hostilities.

November 15, 2024

November 15, 1988 – PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat proclaims the independence of Palestine

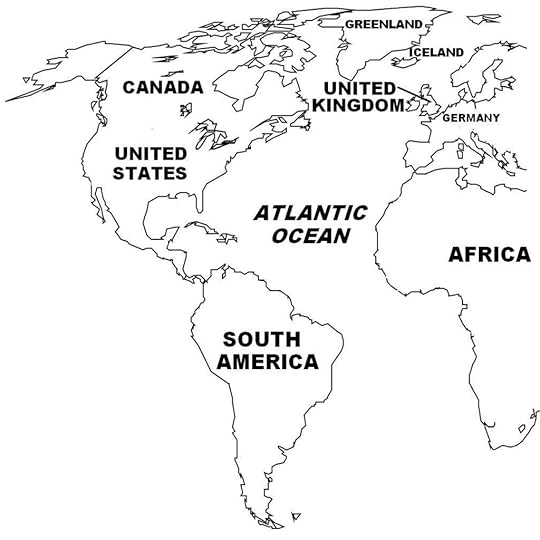

On November 15, 1988, Yasser Arafat, Chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), declared the establishment of the state of Palestine in front of an assembly of Palestinian leaders in ceremonies held in Algiers, Algeria. The assembly then proclaimed Arafat as “President of Palestine”, which was later confirmed in April 1989 by the PLO Central Council that acknowledged him as Palestine’s first president. The declaration of independence was made in the midst of the Palestinian Uprising of 1987-1993 against Israel.

In the Madrid Conference of October 1991, which was jointlysponsored by the United Statesand the Soviet Union, the community of nations urged Israeland the Palestinians, as well as Jordan,Syria, and Lebanon, to begin a negotiated settlement to theMiddle East conflict.

(Taken from Palestinian Uprising of 1987 – 1993 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background As aconsequence of the 1947-48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and the 1948Arab-Israeli War, some 700,000 Palestinian Arabs lost their homes and becamerefugees. Most of them eventuallysettled in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. The Palestinian Jews emerged victorious, inthe process establishing the state of Israel. Then with the Israeli Army’s victory in theSix-Day War in 1967 (separate article), the Israelis gained control of Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. Israel imposed militarized authority over the“occupied territories” (as the Gaza Strip, West Bank, and East Jerusalem were called collectively) as a means to deteropposition. Check points and road blockswere raised, searches and arrests conducted, and civilian movement curtailedand monitored. Perceived enemies wereeliminated, imprisoned, or deported. Furthermore, the Israeli government encouraged its citizens to migrateto the occupied territories, where Israeli housing settlements soon began toemerge.

The Palestinians greatly resented the presence of theIsraelis, whom they regarded as a foreign force occupying Palestinianland. Furthermore, as the Israeliauthority became established and greater numbers of Israeli settlements werebeing built, the Palestinians believed that their lands eventually would beintegrated into Israel. The Israeli occupation was also perceived asa serious blow to the Palestinian people’s aspirations for establishing aPalestinian state.

The Palestinian Liberation Organization, or PLO, a politicaland armed movement, was formed in 1964 and was headed by Chairman Yasser Arafatto lead the Palestinians’ struggle for independence. However, the PLO experienced many setbacks,not only in the hands of Israelbut also by the Arab countries to which the Palestinians had turned forsupport. In 1970, the PLO was expelledfrom Jordan and thereaftermoved to Lebanonwhere, in 1982, it also was forced to leave. Subsequently, the PLO moved its headquarters to Tunisia, whose distant locationprevented the Palestinian leadership from exercising direct control andinfluence over the affairs of Palestinians in the occupied territories. The PLO itself was wracked by internaldissent among some factions that opposed Arafat, who had cast aside hishard-line stance against Israeland adopted a more conciliatory approach.

Furthermore, later developments in the Middle East boded ill for the Palestinians. Egypt,the militarily strongest Arab country and a main supporter of the PLO, hadsigned a peace treaty with Israelin 1979 and ceased its claim to the Gaza Strip. Jordan had not onlyexpelled the PLO but had relinquished its claim to the West Bank and consequently stripped the Palestinian residents there ofJordanian citizenship. Syria, another major backer of the PLO, had afalling out with Arafat during the 1982 Lebanon War and began to support arival PLO faction that ultimately forced Arafat and his Fatah faction to leave Lebanona second time. For so long, the Arabcountries’ regional security concerns centered on the Palestinians’ strugglefor statehood. In the 1980s, however,much of the concentration was on the Iran-Iraq War, relegating the Palestinianissue to a lesser focus. Palestiniansbelieved that many Arab countries, because of the Arab military defeats to theIsraelis, generally had abandoned active support for the Palestinians’nationalist aspirations.

The Palestinians’ frustrations were compounded by direeconomic circumstances in the West Bank and Gaza. Nearly half of all Palestinians were poor and lived in refugee camps incramped, squalid, and poorly serviced conditions. Unemployment was high and so was thePalestinians’ birth rate, leading to more people competing for limited opportunitiesand resources.

Uprising Eversince the Israelis took over the occupied territories, tensions betweenIsraelis and Palestinians persisted, which often erupted in violence. Then during the second half of 1987, thesetensions rose dramatically, ultimately leading to a major Palestinian uprisingthat was triggered by the following events.

On December 6, 1987, an Israeli citizen was murdered in Gaza. Two days later, four Palestinian residents ofthe Jabaliya refugee camp in Gazawere killed in a road accident by a truck belonging to the Israeli Army. Many residents of the Jabaliya camp took tothe streets in protest, believing that the four Palestinians were killeddeliberately in reprisal for the Gazamurder. Israeli security forces moved into disperse the crowd, but in the process, opened fire and killed aprotester. Demonstrations then broke outin other refugee camps in Gaza and the West Bank, triggering a full-blown uprising.

The 1987 Palestinian uprising is more commonly known as theFirst Intifada, where the word “intifada” is Arabic that means “to shake off”,and has come to denote an uprising or rebellion. The 1987 Intifada initially took the form ofspontaneous, disorganized street rallies and demonstrations consisting of tensof thousands of Palestinians who incited anarchy and clashed with Israelisecurity forces. Youths and minors oftenformed the front lines, leading Israeli authorities to accuse the Palestiniansof using the children as “human shields”. The protesters lobbied stones and Molotov cocktails (home-madeincendiary bombs) at the police, burned tires, and set up road blocks andbarricades. Militancy increased when theprotesters began using firearms and grenades as weapons. Other Palestinians supported the intifadathrough non-violent means, such as not paying taxes, boycotting Israeliproducts, and undertaking other forms of civil disobedience.

The depth and speed of the intifada surprised Israeliauthorities, who believed that the actions were being planned and carried outby the PLO. In fact, each local protestaction was organized by community leaders in response to and in support ofother uprisings that were already taking place, creating a snowball effect. Eventually, however, the intifada came underthe centralized command of the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising(UNLU), an alliance of PLO factions in the occupied territories, which began tocarry out more organized militant actions. Two other Palestinian armed groups, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, also rose toprominence during the intifada and emerged as the political and military rivalsto the PLO.

Israeli authorities recorded 3,600 incidents involving theuse of Molotov cocktails, 100 cases with hand grenades, and 600 instances withfirearms and other explosives. Themilitarized nature of the intifada forced Israel to deploy military units toconfront the protesters. In the ensuingclashes, however, hundreds of Palestinian civilians were killed. As a result, the United Nations issued condemnationsagainst Israel,while Amnesty International and other human rights groups criticized theIsraeli government. Israeli authoritiesresponded to the Palestinians’ acts of civil disobedience by imposing heavyfines for non-payment of taxes, and confiscated the violators’ goods,merchandise, and properties. Thegovernment also closed schools, conducted mass arrests, and imposedcurfew. The school closures had thecontrary effect, however, as more youths joined the protest actions.

Israelsoon deployed specially trained anti-riot teams to confront theprotesters. Furthermore, Shin Bet (Israel’sinternal security service) secretly hired Palestinians to collect informationon the uprising, particularly the leaders of the intifada. As a result, a spate of violence took place,where Palestinians began targeting other Palestinians who were believed to bespying for Israel. Palestinians who associated with or workedfor Israelis also were targeted. Thecrackdown also became used as a way to level false accusations on, take revengeagainst, or settle a personal feud, against one’s enemies. As intra-violence among Palestinians began toreach alarming rates, the intifada’s leaders called for an end to the uprising,declaring that Palestinians had lost sight of their original goal, which was toforce the Israelis out of the occupied territories. In the end, the number of deaths caused byintra-violence among Palestinians exceeded the total attributable to theintifada itself.

On November 15, 1988, or eleven months after the start ofthe intifada, Chairman Arafat established the state of Palestinein ceremonies held in Algiers, Algeria. Then in the Madrid Conference of October1991, which was jointly sponsored by the United States and the Soviet Union, the community of nationsurged Israel and thePalestinians, as well as Jordan,Syria, and Lebanon, to begin a negotiated settlement to theMiddle East conflict.

November 14, 2024

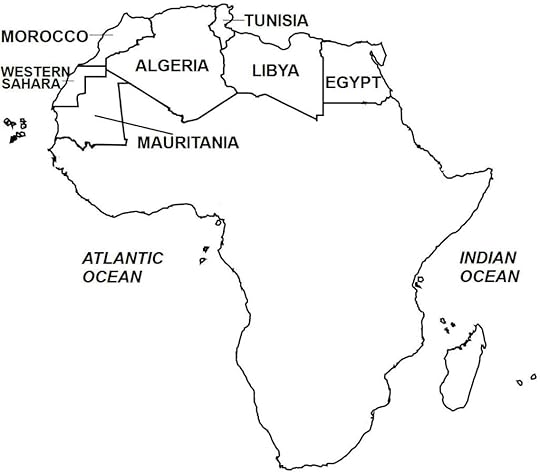

November 14, 1975 – Western Sahara War: Spain cedes administration of Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania

The disputed region of Western Sahara is bounded by Morocco to the north and Mauritania to the south.

The disputed region of Western Sahara is bounded by Morocco to the north and Mauritania to the south.By late October 1975, Spanish officials had begun to holdclandestine meetings in Madrid withrepresentatives from Moroccoand Mauritania with regardsto the region called Spanish Sahara, soon to be known as Western Sahara. As a precaution forwar, in early November 1975, Spaincarried out a forced evacuation of Spanish nationals from the territory. On November 12, further negotiations wereheld in the Spanish capital, culminating two days later (November 14) in thesigning of the Madrid Accords, where Spain ceded the administration (but notsovereignty) of the territory, with Morocco acquiring the regions of El-Aaiún,Boujdour, and Smara, or the northern two-thirds of the region; while Mauritaniathe Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros) region, or the southern third; in exchangefor Spain acquiring 35% of profits from the territory’s phosphate miningindustry as well as off-shore fishing rights. Joint administration by the three parties through an interim government(led by the territory’s Spanish Governor-General) was undertaken in thetransitional period for full transfer to the new Moroccan and Mauritanianauthorities. (The Madrid Accords was not, and also since has not, beenrecognized by the UN, which officially continued to regard Spain as the “dejure”, if not “de facto”, administrative authority over the territory;furthermore, the UN deems the conflict region as occupied territory by Moroccoand, until 1979, also by Mauritania.)

On February 26, 1976, Spainfully withdrew from the territory, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred toit as such by 1975). As per theagreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; alsoin 1979, Morocco wouldinclude the southern zone after Mauritaniawithdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla(as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tirisal-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976,the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory intotheir respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976)during Spain’s withdrawaland replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens ofthousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the PolisarioFront declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR),with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Centry – Volume 4)

Background Forthe Spanish government, Spanish Sahara had been a financial liability, themostly barren, uninhabitable desert apparently yielding no economic benefits,with its rich maritime fishing resources bringing some export revenues butnonetheless incapable of reversing the need for Spain to allocate some amountof money annually to run the colony’s administration. But in the late 1940s, commercial quantitiesof high-grade phosphate deposits were discovered in Bou Craa, and the prospectof finding petroleum oil sparked Spain’sinterest to hold onto the territory despite the growing wave ofanti-colonialism that had been sweeping across Africasince the end of World War II.

In December 1960, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA)passed Resolution 1514 titled “Declaration on the Granting of Independence toColonial Countries and Peoples”, a landmark act that established the UN’sprinciple of decolonization; an implementing agency called the SpecialCommittee on Decolonization, was formed to undertake the decolonizationprocess. Based on Resolution 1514, theUNGA created a list called the “In-Trust and Non-self-governing Territories”,which contained territories that were still under colonial rule. In 1963, Spanish Saharawas placed on that list.

In April 1956, Moroccogained full independence after Franceand Spainended their protectorates over the Moroccan state. The Istiqlal Party, an ultra-nationalistpolitical party, advocated “Greater Morocco”, which called for the integrationwith present-day Moroccoof lands and peoples historically governed by or subservient to the ancientMoroccan Sultanate. The concept of aGreater Morocco received broad support among the Moroccan population. The Moroccan government, led by King MohammedV, officially did not endorse this policy, but also did not discourage – andeven tacitly supported – its adherents from carrying out activities in supportthereof.

Thus, the government remained neutral when, in the Ifni War(previous article) of October 1957, Moroccan militias of the Moroccan Army ofLiberation (MAL) invaded Spanish possessions in Western Africa that Moroccannationalists believed were historically part of Morocco. In the aftermath, Spain ceded a portion of its WestAfrican possessions. Then in 1963, Morocco fought a border war with Algeria in a failed attempt to capture territoryin western Algeria that washistorically part of Moroccoand was included in the “Greater Morocco” concept.

By the first half of the 1970s, strong internationalpressure was bearing down on Spainto decolonize Spanish Sahara; the Spanishgovernment’s justification of the territory being a Spanish “overseas province”was rejected by the UN. King Mohammed Vled the call for decolonization, declaring that Spanish Sahara was historicallya part of Moroccoand thus must be returned to its owner. Mauritania also made a rival claim to theregion, citing ethnic and cultural ties between northern Mauritanian peoplesand Spanish Sahara’s Sahrawi tribes. Compounding Spain’s problems was the factthat since May 1973, Spanish Sahara itself was caught up in an uprising led bythe Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Río de Oro (orPolisario Front; Spanish: Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Ríode Oro), a local Sahrawi armed militia that was fighting a guerilla war to endSpanish rule and achieve independence for Spanish Sahara.

In 1974, Spainfinally acquiesced, announcing that it was ready to grant self-determinationfor the Sahrawi people corresponding to the UN resolutions. In December 1974, Spaincarried out a population census in Spanish Saharain order to prepare a voters list that would be used in a forthcomingreferendum to determine the political wishes of the Sahrawi population. In a final bid to keep its economic, if notpolitical, hold on the region, in November 1974, the Spanish government formedthe Sahrawi National Union Party (PUNS; Spanish: Partido de Unión Nacional Saharaui),a political party mostly composed of the leaders and elders of the variousSahrawi tribes. Spain hoped to establish a PUNS-led governmentin either an autonomous or independent Saharathat would retain a pro-Spanish foreign policy.

On December 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292declaring the UN’s interest in evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawisin the Spanish territory. For thispurpose, the UN formed the UN Decolonization Committee, which in May – June1975, carried out a fact-finding mission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco, Mauritania,and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15,1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the generalpopulation in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara,however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under theleadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy suchsupport. In Algeria, the UN Committee foundstrong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self-determination.

Algeriapreviously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an ArabLeague summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria was openly defending thePolisario Front’s struggle for independence, a support that later would includemilitary and economic aid and would have a crucial effect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of KingMohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claimand asked Spainto postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish governmentgranted the Moroccan request. In June1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to theInternational Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UNDecolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision,which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers to SpanishSahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the timeof Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the timeof Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and theMauritanian entity”;

3. Thereexisted “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance betweenthe Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara.They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating tothe land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and theterritory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJconcluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorialsovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Moroccoor the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such anature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, inparticular, … the principle of self-determination through the free and genuineexpression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvementradicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of thecourt’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respectiveclaims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish anytie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determinationthrough the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of theTerritory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing thepost-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri andPolisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers,Algeria to negotiate thetransfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economicconcessions to Spain,particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did notprosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greaterpressures exerted by the other competing parties.

November 13, 2024

November 13, 1941 – World War II: A German U-boat torpedoes the British carrier HMS Ark Royal

One of the main assets of the German U-boat (submarine; German: U-boot, shortened from Unterseeboot, literally “underseaboat”) was stealth, and the first naval casualty of the war, the British ocean liner, SS Athenia, was attacked and sunk by a U-boat (which it mistook for a British warship) on September 3, 1939, with 128 lives lost. Also in September 1939 and just a few days apart, two British aircraft carriers, the HMS Ark Royal and HMS Courageous, were both attacked by a U-boat, with the former narrowly being hit by torpedoes, while the latter was hit and sunk. Then in October 1939, another U-boat penetrated undetected near Scapa Flow, the main British naval base, attacking and sinking the battleship, the HMS Royal Oak. On November 13, 1941 off Gibraltar, a U-boat fired one torpedo on the HMS Ark Royal, which sank the next day.

(Taken from Battle of the Atlantic – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

At the start of the war, the British military washard-pressed on how to deal with the U-boat threat. During the interwar period, prevailing navalthought and budgetary resources, both Allied and German alike, focused onsurface ships, and the belief that battleships would play the dominant role innaval warfare in a future war. GermanU-boats had proved highly effective in World War I, causing heavy losses onmerchant shipping that nearly forced Britain out of the war, before theBritish introduced the convoy system that turned fortunes around.

However, the British Navy’s implementing the ASDIC system(acronym for “Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee”; otherwise knownas SONAR), which could detect the presence of submerged submarines, appeared tohave solved the U-boat threat. Navaltests showed that once detected by ASDIC, the submarine could then be destroyedby two destroyers launching depth charges overboard continuously in a longdiamond pattern around the trapped vessel. The British concept was that the U-boats could operate only in coastalwaters to threaten harbor shipping, as they had done in World War I, and thesetests were conducted under daylight and calm weather conditions. But by the outbreak of World War II, Germansubmarine technology had rapidly advanced, and were continuing so, that U-boatswere able to reach farther out into the Atlantic Ocean, eventually ranging asfar as the American eastern seacoast, and also were able to submerge to greaterdepths beyond the capacity of depth charges. These factors would weigh heavily in the early stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

In December 1939, hostilities were suspended by the harshAtlantic weather, and German surface ships and U-boats returned to their basesin Germany. In May 1940, the eight-month “Phoney War”period of combat inactivity in the West was broken by the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, which had beenpreceded one month earlier, April 1940, with the conquest of the Scandinaviancountries of Denmark and Norway. By late June 1940, these campaigns werecomplete, Italy had joinedthe war on Germany’s side,and Britain remained thesole defiant nation in Western Europe.

These triumphs in Scandinavia and Western Europe wereimportant for the Kriegsmarine: in the Norwegian campaign, the German Navy,which played a major role by transporting the troops and war supplies to thelanding points, lost a large part of its surface fleet, and for a time, wasrendered virtually incapacitated, while the conquest of France allowed theKriegsmarine to establish new bases in western France, at Brest, Lorient, LaRochelle, and Saint-Nazaire, which greatly reduced (by 450 miles) the distance tothe Atlantic, allowing the U-boats to range further west and spend more time atsea. The campaigns also eased thedifficult war-time economy of Germany,as more agricultural and industrial resources became available. Germany’sposition would later improve further with more conquests, as well as withforming Axis treaties, in Eastern Europe,rendering the British blockade (temporarily) ineffective.

But for Britain, these campaigns were disastrous: in Norway,the Dunkirk evacuation, and clashes in the English Channel and the North Sea,the Royal Navy lost 23 destroyers sunk, and dozens more damaged; there loomedthe possibility that the Germans might seize the French fleet and use it toinvade Britain; and more Royal Navy ships had to return for the defense of thehomeland, thus reducing security for the merchant convoys in the Atlantic. To preclude the possibility that the Frenchships would fall to the Germans, in July 1940, the British Navy attacked theFrench fleet at Mers-el-Kebir, French Algeria, while the French squadron at Alexandria, Egypt,was forced to be interned by the British fleet there. These naval actions infuriated the new,nominally sovereign Vichy government in France, which had declared its neutrality in thewar, and also because it had assured Britain that the French Navy wouldnot fall into German hands.

In July 1940, Hitler launched the Luftwaffe over the English Channel and British skies, starting the air warknown as the Battle of Britain. The airattacks peaked in August 1940, when the Luftwaffe turned its attention fromattacking British military and industrial infrastructures to bombing civiliantargets in Londonand other cities, which would continue with some intensity until early1941. By then, the threat of a Germancross-channel invasion (Operation Sea Lion) had diminished, and endedcompletely in May 1941 when Hitler was fully engaged in the forthcominginvasion of the Soviet Union, set for June1941.

Meanwhile, in the second half of 1940, hostilities in theAtlantic again escalated following the end of the campaigns in Scandinavia and Western Europe. Launching from their new bases in western France,in June 1940, U-boats in increasing numbers prowled the Atlantic,immediately coming upon and attacking and sinking many merchant ships. In a radical change from World War I U-boatsthat operated singly as lone ambushers of isolated ships, in September 1940,Admiral Karl Donitz, head of the U-boat arm of the Kriegsmarine, devised Rudeltaktik(“pack tactics”), where a squadron of U-boats would simultaneously attack aconvoy of ships. This strategy, sooncalled “wolf pack” by the British, consisted of several U-boats spaced out in asingle long line across the anticipated path of an incoming convoy. One U-boat, upon sighting the convoy, wouldmaintain contact with it, while the other U-boats were alerted by radio and bebrought forward. Together, the U-boatswould attack at night, generally with impunity against the lightly escortedconvoys, inflicting heavy losses in men and ships. Convoy protection was provided by corvettes,which were too slow to chase away a U-boat. ASDIC also proved unreliable in the turbulent conditions that thebattles generated and in inclement weather, and underwater detection wasfurther defeated by U-boats that stayed at the surface at night.

The German effort also was strengthened when in August 1940,the Italian Navy (Regia Marina) sent a fleet of submarines to operate in theAtlantic from a naval base in Bordeaux, France. Over-all, the Italian contribution was small,with only a few dozen submarines taking part, and accounted for 3% of the totalnumber of merchant ships sunk in the Battle ofthe Atlantic. From June to October 1940, in what German U-boat crews celebrated as“The Happy Time” (German: Die Glückliche Zeit), German U-boats sunk 274 Alliedships (totaling 1.5 million tons) for the loss of only 6 U-boats. This stunning success brought instant fame tomany U-boat commanders and their crews, who were welcomed as heroes on theirreturn to Germany.

In November 1940, Britainintroduced some counter-measures: convoys were diverted away from the regulartrade routes to further north near Iceland and shipping codes werechanged. More measures were adopted inearly 1941: the merchant convoys and British reconnaissance aircraft wereequipped with radar to detect surfaced U-boats; the British Western ApproachesCommand (tasked with safeguarding the Atlantic trade) was moved to Liverpool,allowing better strategic control; and the convoys were given naval escortprotection all along the length of the Atlantic. In the latter, the convoys at their assemblypoint in St. John’s, Newfoundland,Canada were escorted byRoyal Canadian Navy ships to a designated point off Iceland,where the British Royal Navy then would take over escort protection for therest of the way to Britain. Furthermore, the British Navy introduced anew convoy system: a few large convoys (rather than many smaller convoys) wereorganized, as British experience thus far showed that their less frequencymeant that they were exposed to less time to attack, and they required fewerescorts measured on a prorated basis against smaller convoys.

The end of the U-boat’s “Happy Time” in November 1940coincided with the German Navy’s surface ships rampaging through the Atlantic Ocean. Inearly November 1940, the German heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer came upon anAllied merchant convoy, sinking five ships and damaging many others. In January-March 1941, in a series ofactions, two German battleships, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, sunk orcaptured 22 merchant ships. And inFebruary 1941, the cruiser Admiral Hipper ambushed a 19-ship unescorted convoy,sinking 13 ships.

By then, British battleships were tasked to protect merchantships, and in a number of incidents, they warded off German surface raidersfrom attacking the convoys. This measurepaid off materially when two German ships, the new battleship Bismarckand the cruiser Prinz Eugen, were sighted off Icelandby a British naval squadron, and in the ensuing clash, the Bismarck was damaged, although it sank theBritish battle cruiser HMS Hood. Whileattempting to escape to France,the Bismarckwas intercepted and sunk. The increasingBritish Navy presence in the Atlantic and Hitler’s displeasure with the loss ofthe Bismarck compelled the Fuhrer to suspendsurface fleet operations in the Atlantic. The German Navy’s surface vessels finallyceased to have any impact in the Atlantic when in February 1942, in the“Channel Dash”, the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen boldly crossed theheavily protected English Channel from their base in western France to Norway. The transfer was prompted by reports of animminent British invasion of Norway,as well as the need for greater German naval presence in the Norwegian Arcticto stop the Allied convoys supplying the beleaguered Soviet Union.

In the second half of 1941, Admiral Donitz focused U-boatoperations along the “mid-Atlantic air gap”, which accounted for 70% of Alliedmerchant ship losses during this period. Improved Allied aircraft technology, which allowed greater air range,was yet unable to provide cover for the full distance of the vast Atlantic Ocean. Allied shipping losses in the Atlantic war was eased somewhat when manyU-boats were withdrawn to other sectors, first in June 1941 to the Arctic tohelp stop the flow of Allied supplies to the Soviet Union, and in October 1941,in the Mediterranean Sea to cut British supply lines in the North Africancampaign.

November 12, 2024

November 12, 1995 – The Croatian War of Independence: A peace treaty is signed

On November 12, 1995, representatives of the warring sides, Republic of Croatia and Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), signed the Erdut Agreement (officially titled: “Basic Agreement on the Region of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium”), a peace treaty that ended the Croatian War of Independence. Erdut is a village in present-day Croatia. Instructed to sign by the Yugoslav central government, RSK comprised Croatian Serbs in the regions of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia.

As stipulated in the agreement, Eastern Slavonia would be reintegrated with Croatia in exchange for the Croatian government promising political concessions to ethnic Serbs. A UN mission, called the United Nations Transitional Authority for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western Sirmium (UNTAES), arrived to implement the peace agreement. In January 1988, Croatia regained sovereignty over Eastern Slavonia, thereby restoring its pre-war territorial boundaries.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.Taken from Croatian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background By the late 1980s, Yugoslavia was faced with a major political crisis, as separatist aspirations among its ethnic populations threatened to undermine the country’s integrity (see “Yugoslavia”, separate article). Nationalism particularly was strong in Croatia and Slovenia, the two westernmost and wealthiest Yugoslav republics. In January 1990, delegates from Slovenia and Croatia walked out from an assembly of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the country’s communist party, over disagreements with their Serbian counterparts regarding proposed reforms to the party and the central government. Then in the first multi-party elections in Croatia held in April and May 1990, Franjo Tudjman became president after running a campaign that promised greater autonomy for Croatia and a reduced political union with Yugoslavia.

Ethnic Croatians, who comprised 78% of Croatia’s population, overwhelmingly supportedTudjman, because they were concerned that Yugoslavia’snational government gradually had fallen under the control of Serbia, Yugoslavia’s largest and mostpowerful republic, and led by hard-line President Slobodan Milosevic. In May 1990, a new Croatian Parliament wasformed and subsequently prepared a new constitution. The constitution was subsequently passed inDecember 1990. Then in a referendum heldin May 1991 with Croatian Serbs refusing to participate, Croatians votedoverwhelmingly in support of independence. On June 25, 1991, Croatia,together with Slovenia,declared independence.

Croatian Serbs (ethnic Serbs who are native to Croatia) numbered nearly 600,000, or 12% of Croatia’stotal population, and formed the second largest ethnic group in therepublic. As Croatiaincreasingly drifted toward political separation from Yugoslavia, the Croatian Serbsbecame alarmed at the thought that the new Croatian government would carry outpersecutions, even a genocidal pogrom against Serbs, just as the pro-Naziultra-nationalist Croatian Ustashe government had done to the Serbs, Jews, andGypsies during World War II. As aresult, Croatian Serbs began to militarize, with the formation of militias aswell as the arrival of armed groups from Serbia.

Croatian Serbs formed a population majority in south-west Croatia(northern Dalmatian and Lika). There, inFebruary 1990, they formed the Serb Democratic Party, which aimed for thepolitical and territorial integration of Serb-dominated lands in Croatia with Serbiaand Yugoslavia. They declared that if Croatia wanted to secede from Yugoslavia, they, in turn, should be allowed toseparate from Croatia. Serbs also interpreted the change in theirstatus in the new Croatian constitution as diminishing their civil rights. In turn, the Croatian government opposed theCroatian Serb secession and was determined to keep the republic’s territorialintegrity.

In July 1990, a Croatian Serb Assembly was formed thatcalled for Serbian sovereignty and autonomy. In December, Croatian Serbs established the SAO Krajina (SAO is theacronym for Serbian Autonomous Oblast) as a separate government from Croatia in the regions of northern Dalmatia and Lika. Croatian Serbs formed a majority population in two other regions in Croatia, which they also transformed intoseparate political administrations called SAO Western Slavonia, and SAO EasternSlavonia (officially SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja, and Western Syrmia). (Map 17 showslocations in Croatiawhere ethnic Serbs formed a majority population.) In a referendum held inAugust 1990 in SAO Krajina, Croatian Serbs voted overwhelmingly (99.7%) forSerbian “sovereignty and autonomy”. Thenafter a second referendum held in March 1991 where Croatian Serbs votedunanimously (99.8%) to merge SAO Krajina with Serbia, the Krajina governmentdeclared that “… SAO Krajina is a constitutive part of the unified stateterritory of the Republic of Serbia”.

November 11, 2024

November 11, 1968 – Vietnam War: The U.S. military launches Operation Commando Hunt

On November 11, 1968, the United States military initiated Operation Commando Hunt aimed at stopping the flow of men and supplies through the Ho Chi Minh Trail from North Vietnam to South Vietnam. Operation Commando Hunt lasted until March 1972 and consisted of bombing and strafing air attacks on enemy targets inside the thickly forested Ho Chi Minh Trail. Throughout the war, the U.S. military launched similar aerial operations (Steel Tiger, Tiger Hound) on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, all of which ultimately proved unsuccessful. From the outset, U.S. military planners viewed these campaigns as incapable of completely stopping infiltration, but were meant to inflict as much destruction to the logistical system and tie down as many North Vietnamese units in static roles. In this way, it was hoped that North Vietnam would be forced to abandon the route. To counter the U.S. air attacks, which intensified as the war progressed, North Vietnam massively fortified the Trail system, which eventually was bristling with 1,500 anti-aircraft guns. Supply convoys also traveled only at night to lessen the risk to U.S. air attacks.

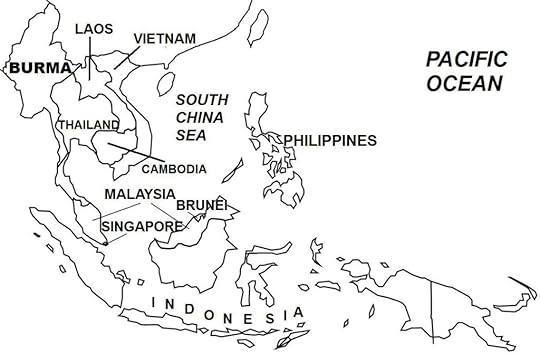

Southeast Asia in the 1960s

Southeast Asia in the 1960sBecause the United States used massive air firepower, North Vietnam, eastern Laos, and eastern Cambodia were heavily bombed. U.S. planes dropped nearly 8 million tons of bombs (twice the amount the United States dropped in World War II), and Indochina became the most heavily bombed area in history. Some 30% of the 270 million so-called cluster bombs dropped did not explode, and since the end of the war, they continue to pose a grave danger to the local population, particularly in the countryside. Unexploded ordnance (UXO) has killed some 50,000 people in Laos alone, and hundreds more in Indochina are killed or maimed each year.

Vietnam War showing Ho Chi Minh Trail

Vietnam War showing Ho Chi Minh Trail(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Ho Chi Minh Trail Throughoutthe war, the United Stateslaunched other aerial operations (Steel Tiger, Tiger Hound, and Commando Hunt)on the Ho Chi Minh Trail to try and stop the flow of men and materiel from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, but all of theseultimately proved unsuccessful.

Over the course of the war, the Ho Chi Minh Trail systemexpanded considerably into an elaborate network of small and wide roads, footand bike paths, and concealed river crossings across a vast and ever-increasingarea in the eastern regions of Laosand Cambodia. With 43,000 North Vietnamese and Laotianlaborers, dozens of bulldozers, road graders, and other road-building equipmentworking day and night, by December 1961, the Trail system allowed for trucktraffic, which became the main source of transporting men and supplies for therest of the war. Apart from constructioncrews, other units in the Ho Chi Mnh Trail were tasked with providing food,housing, and medical care, and other services to soldiers and transport crewsmoving along the system. To counter U.S.air attacks, which intensified as the war progressed, the Trail system wasmassively fortified with air defenses, eventually bristling with 1,500anti-aircraft guns. Supply convoys alsotraveled only at night to lessen the risk of U.S. air attacks.

But because of the U.S. air campaign, American basescame under greater threat of Viet Cong retaliatory attacks. Thus, in March1965, on President Johnson’s orders, 3,500 U.S. Marines arrived to protect Da Nang air base. These Marines were the first U.S. combat troops to be deployed in Vietnam. Then in April 1965, when the U.S. government’s offer of economic aid to North Vietnam in exchange for a peace agreementwas rejected by the Hanoi government, PresidentJohnson soon sent more U.S.ground forces, raising the total U.S.personnel strength in Vietnamto 60,000 troops. At this point, U.S.forces were authorized only to defend American military installations.

Then in May 1965, in a major effort to overthrow South Vietnam, Viet Cong and North Vietnameseforces launched attacks in three major areas: just south of the DMZ, in theCentral Highlands, and in areas around Saigon. U.S.and South Vietnamese forces repulsed these attacks, with massive U.S. air firepower being particularly effective,and in mid-1965, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces retreated, and thedanger to the Saigon government passed. By that time also, President Johnson agreedto the U.S. military’srequest and sent more troops to Vietnam,raising the total to 184,000 by the end of 1965. More crucially, he now authorized U.S. forces to not merely defend U.S.facilities, but to undertake offensive combat missions, in line with Americanmilitary doctrine to take the war to the enemy.

Meanwhile in June 1965, South Vietnam’s political climateeased considerably with the appointment of Nguyen Cao Ky as Prime Minister andNguyen Van Thieu as (figurehead) Chief of State. The new South Vietnamese regime imposedcensorship and restrictions on civil liberties because of the unstable securitysituation, as well as to curb widespread local civilian unrest. In 1966, Prime Minister Kyquelled a Buddhist uprising and brought some stability to the South Vietnamesemilitary. Ky and Thieu were politicalrivals, and after Thieu was elected president in the 1967 presidentialelection, a power struggle developed between the two leaders, with PresidentThieu ultimately emerging victorious. Bythe late 1960s, Thieu had consolidated power and thereafter ruled with nearautocratic powers.

During the Vietnam War, the United States, which soon wasjoined with combat forces from its anti-communist allies Australia, NewZealand, South Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines, began to take directcommand of the war in what was called the period of the “Americanization” ofthe war, relegating the South Vietnamese military to a supporting role. Nevertheless, President Johnson imposedrestrictions on the U.S. military – that it was to engage only in a limited war(as opposed to a total war) that was sufficiently aggressive enough to deterNorth Vietnam from attacking South Vietnam, but should not be too overpoweringto incite a drastic response from the major communist powers, China and theSoviet Union.

The United States was concerned that China might intervene directly for North Vietnam (as it had done for North Korea in the Korean War), or worse, thatthe Soviet Union might invade Western Europe. A consequence of U.S. policy in Vietnam tonot incite a wider war with China and the Soviet Union meant that U.S. forcescould not invade North Vietnam, and that U.S. bombing missions in North Vietnamwere to be screened so as not to kill or harm Chinese or Soviet militarypersonnel there or destroy Chinese and Soviet assets (e.g. ships docked atNorth Vietnamese ports). Thus, U.S. ground forces were limited to operating in South Vietnam,where subsequently nearly all of the land fighting took place. Even then, the U.S.high command was confident of success, and General William Westmoreland,commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam,predicted American victory over the Viet Cong/NLF by the end of 1967.

To achieve this goal, the U.S. military employed the “searchand destroy” strategy (which was developed by the British in the 1950s), whereU.S. intelligence would locate large Viet Cong/NLF concentrations, which wouldbe destroyed using massive American firepower involving air, artillery,infantry, and in some cases armored, units. U.S.military planners believed that the use of overwhelming force would inflictsuch heavy losses that the Viet Cong would be unable to replace its manpowerand material losses, ultimately leading to the defeat of the southerninsurgency.

November 10, 2024

November 10, 1945 – Indonesian War of Independence: British forces and Indonesian nationalist militias clash in the Battle of Surabaya

On November 10, 1945, British forces and Indonesian nationalist fighters fought the Battle of Surabaya during the Indonesian War of Independence. After World War II ended, the first Allied forces arrived in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) in mid-September 1945. When British forces arrived in Surabaya in East Java in late October, they found that the city was fortified by Indonesian nationalist fighters – in all, some 20,000 Indonesian revolutionary troops and 100,000 militia fighters had taken defensive positions. In a skirmish on October 30, 1945, British Brigadier A.W.S. Mallaby was killed, which served as a trigger for the British to initiate full-scale fighting on November 10. Within three days, British forces had largely taken the city, but fierce house-to-house fighting continued for three weeks, with some 30,000 British troops supported with tanks, aircraft, and artillery bombardment from warships finally forcing out the last guerrilla resistance.

The Southeast Asian country of Indonesia was known as the Dutch East Indies during the colonial period.

The Southeast Asian country of Indonesia was known as the Dutch East Indies during the colonial period.(Taken from Indonesian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

BackgroundSukarno’s proclamation of Indonesia’s independence de facto produced a state of war with the Allied powers, which were determined to gain control of the territory and reinstate the pre-war Dutch government. However, one month would pass before the Allied forces would arrive. Meanwhile, the Japanese East Indies command, awaiting the arrival of the Allies to repatriate Japanese forces back to Japan, was ordered by the Allied high command to stand down and carry out policing duties to maintain law and order in the islands. The Japanese stance toward the Indonesian Republic varied: disinterested Japanese commanders withdrew their units to avoid confrontation with Indonesian forces, while those sympathetic to or supportive of the revolution provided weapons to Indonesians, or allowed areas to be occupied by Indonesians. However, other Japanese commanders complied with the Allied orders and fought the Indonesian revolutionaries, thus becoming involved in the independence war.