Daniel Orr's Blog, page 94

June 21, 2020

June 21, 1940 – World War II: Italian forces launch a major offensive against France along the Alps

On June 21, 1940, Italian forces launched a general offensive into France across the Alpine region, successfully gaining some territory but failing to break the French resistance. The attack came just before France and Germany were about to sign an armistice following the German blitzkrieg into France.

Italy had entered World War II on Germany’s side on June 10, 1940 by declaring war on France and Britain. Italian leader Benito Mussolini rejected the counsel of his top commanders that Italy was unprepared for war, opportunistically stating that “I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought”. Italy’s contribution to the campaign would be inconsequential, as the 450,000 invading Italian troops (outnumbering the 190,000 French defenders by over 2:1) were unable to break through the Alpine Line in the rough, high-altitude terrain and prevailing winter-like snowy weather at the 300-mile long French-Italian border.

But with the French defeat against the Germans and subsequent armistice, Italian forces occupied territory on the French-Italian border, which was expanded in November 1942 to the southeast region of Vichy France as well as Corsica.

Italy and Germany In the period before World War II, Italy’s ties with Germany prospered. Both shared a common political ideology. In the Spanish Civil War (July 1936-April 1939), Italy and Germany supported the Nationalist rebel forces of General Francisco Franco, who emerged victorious and took over power in Spain. In October 1936, Italy and Germany formed an alliance called the Rome-Berlin Axis. In 1937, Italy joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had been signed by Germany and Japan in November 1936. In May 1939, Mussolini and Hitler formed a military alliance, the Pact of Steel. The alliance between Germany and Italy, together with Japan, reached its apex in September 1940, with the signing of the Tripartite Pact, and these countries came to be known as the Axis Powers.

However, on September 1, 1939 World War II broke out when Germany attacked Poland. Italy

did not enter the war as yet, since despite Mussolini’s frequent blustering of

having military strength capable of taking on the other great powers, Italy

in fact was unprepared for a major European war.

June 20, 2020

June 20, 1963 – Cuban Missile Crisis: The United States and Soviet Union agree to establish a “hotline” or direct communication

On June 20, 1963, the United States and Soviet Union signed an agreement that established a direct teletype link, or “hotline”, between Washington and Moscow, in order to speed up the transmission of communications between the leaders of both countries. This came about following the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, where the two superpowers were locked in a 13-day standoff over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. U.S. President John F. Kennedy perceived the weapons in Cuba as a threat to U.S. national security and announced that he was prepared to use force to neutralize them. World sentiment at that time was that the two superpowers were on the brink of a nuclear war. The impasse was resolved when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev offered to remove the missiles in exchange for the U.S. promising not to invade Cuba. In the aftermath, the United States also secretly removed its missiles from Turkey.

NATO’s deployment of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s decision to install nuclear weapons in Cuba.

NATO’s deployment of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s decision to install nuclear weapons in Cuba.Aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis The near-confrontation had profound consequences on the main protagonists. President Kennedy’s popularity soared in the United States and in other democratic countries, where he was seen as strong, firm, and determined to go to war for the free world. The perception of Kennedy being an irresolute leader following his lackluster actions during the Bay of Pigs Invasion and Berlin Crisis was erased instantly. Fidel Castro retained and even tightened his domination over Cuba, as the United States, in the future, generally refrained from carrying out a determined effort to bring about his overthrow. For Khrushchev, he ostensibly had lost the gamble, since his agreement with the Americans did not carry a public disclosure of the removal of the U.S. missiles in Turkey. What was apparent was that he merely had gained a promise from President Kennedy not to invade Cuba for the much more politically and strategically important Soviet missiles in Cuba. Considerable humiliation was brought upon Soviet authorities, which contributed greatly to Premier Khrushchev’s ouster from power two years later.

In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane detected a Soviet nuclear missile site under construction in San Cristobal, Pinar del Rio. After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the continued presence of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, a U.S. military facility located at the eastern end of Cuba, greatly infuriated Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane detected a Soviet nuclear missile site under construction in San Cristobal, Pinar del Rio. After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the continued presence of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, a U.S. military facility located at the eastern end of Cuba, greatly infuriated Cuban leader Fidel Castro.In the immediate aftermath, the United States restarted destabilization operations against Castro’s government. However, President Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963 and the growing U.S. involvement in Indochina, another Cold War battlefield, and particularly in Vietnam, finally led President Lyndon Johnson, who succeeded President Kennedy as American head of state, to end all destabilizing actions in Cuba. Also as a result of the crisis, on June 20, 1963, the two superpowers signed an agreement that established a direct teletype link, or “hotline”, between Washington and Moscow, in order to speed up the transmission of communications between the leaders of both countries.

The crisis was resolved by the United States and the Soviet Union, without the participation of Cuba. As a result, Castro felt betrayed by Khrushchev, particularly since he felt that the negotiations had taken only the American and Soviet interests in mind, and disregarded Cuban security concerns. The Cuban leader also felt that a mere U.S. promise not to invade Cuba was insufficient, and subsequently issued his “Five Points” manifesto, one point being that the United States military must withdraw from the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base (located at the eastern end of Cuba) and return the land to the Cuban people. Castro had been made aware of the negotiations between the two superpowers through Alexandr Alexeyev, the Soviet Ambassador to Cuba, and was infuriated at the final agreement.

The agreement pertained to the Soviet strategic MRBMs and IRBMs; as a result, the Soviets were not under obligation to remove the battlefield tactical nuclear missiles, which in fact they had intended to turn over to the Cuban Armed Forces. However, Castro’s unpredictability and temperament convinced the Soviets that nuclear weapons, with their destructive power, could not be entrusted to the Cuban leader. On October 22, these weapons were returned to the Soviet Union. Subsequent Soviet policies of appeasements, however, did restore normal relations between the two communist allies, even strengthening them in the years that followed. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 2.)

June 19, 2020

June 19, 1965 – Vietnam War: A new military-led government is formed in South Vietnam

On June 19, 1965, Air Marshall Nguyen Cao Ky became Prime Minister of South Vietnam as head of a military junta, while General Nguyen Van Thieu became the figurehead chief of state. This arose after two years of severe political instability where South Vietnam experienced a series of leadership changes following a military-backed coup and assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem in November 1963. Diem had served as Prime Minister in 1954-1955 and then as President from 1955 until his death in 1963. Following the coup, a junta was set up to lead the country, but which was racked by power struggles that led to a series of short-lived military governments.

With the formation of Ky-Thieu junta in June 1965, South Vietnam’s political climate stabilized somewhat.

In relation to the Vietnam War

In May 1965, in a major effort to overthrow South Vietnam, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces launched attacks in three major areas: just south of the DMZ, in the Central Highlands, and in areas around Saigon. U.S. and South Vietnamese forces repulsed these attacks, with massive U.S. air firepower being particularly effective, and in mid-1965, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces retreated, and the danger to the Saigon government passed. By that time also, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson agreed to the U.S. military’s request and sent more troops to Vietnam, raising the total to 184,000 by the end of 1965. More crucially, he authorized U.S. forces to not merely defend U.S. facilities, but to undertake offensive combat missions, in line with American military doctrine to take the war to the enemy.

Meanwhile in June 1965, South Vietnam’s political climate eased considerably with the appointment of Nguyen Cao Ky as Prime Minister and Nguyen Van Thieu as (figurehead) Chief of State. The new South Vietnamese regime imposed censorship and restrictions on civil liberties because of the unstable security situation, as well as to curb widespread local civilian unrest. In 1966, Prime Minister Ky quelled a Buddhist uprising and brought some stability to the South Vietnamese military. Ky and Thieu were political rivals, and after Thieu was elected president in the 1967 presidential election, a power struggle developed between the two leaders, with President Thieu ultimately emerging victorious. By the late 1960s, Thieu had consolidated power and thereafter ruled with near autocratic powers. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5- Twenty Wars in Asia.)

June 18, 2020

June 18, 1900 – Boxer Rebellion: Empress Dowager Cixi of China orders her people to resist foreigners

Foreign spheres of influence in China in the early 1900s

The Boxer Rebellion

In the late 19th century, a secret society called the ““Righteous and Harmonious Fists” (Yihequan) was formed in the drought-ravaged hinterland regions of Shandong and Zhili provinces. The sect formed in

the villages, had no central leadership, operated in groups of tens to several hundreds of mostly young peasants, and held the belief that China’s problems

were a direct consequence of the presence of foreigners, who had brought into the country their alien culture and religion (i.e. Christianity).

Sect members practiced martial arts and gymnastics, and performed mass religious rituals, where they invoked Taoist and Buddhist spirits to take possession of their bodies. They also believed that these rituals would confer on them invincibility

to weapons strikes, including bullets. As the sect was anti-foreign and anti-Christian, it soon gained the

attention of foreign Christian missionaries, who called the group and its followers “Boxers” in reference to the group’s name and because it practiced martial arts.

The Qing government, long wary of secret societies which historically had seditious motives, made efforts to suppress the Boxers. Because of government repression, the Boxers renamed their organization the “Righteous and Harmonious Militia (Yihetuan)”, using the word “militia” to de-emphasize their origin as a secret society and give the movement a form of legitimacy. Even then, the Qing government continued to view the Boxers with suspicion.

By May 1900, thousands of Boxers were occupying areas around Beijing, including the vital Beijing-Tianjin railway line. They attacked villages, killed local officials, and destroyed government infrastructures. The violence alarmed the foreign diplomatic community in Beijing. The foreign diplomats, their staff, and families in Beijing had their offices and residences located at the Legation Quarter, located south of the city. The Legation Quarter consisted of diplomatic missions from eleven countries: Britain, France, Russia, United States, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Japan, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Spain.

In May 1900, the foreign diplomats asked the Qing government that foreign troops be allowed to be posted at the Legation Quarter, which was denied. Instead, the Chinese government sent Chinese policemen to guard the legations. But the foreign envoys persisted in their request, and on May 30, 1900, the Chinese Foreign Ministry (Zongli Yamen) allowed a small number of foreign troops to be sent to Beijing.

The next day (May 31), some 450 foreign sailors and Marines were landed from ships from eight countries and sent by train from Taku to Beijing. But as the situation in Beijing continued to deteriorate, the foreign diplomats felt that more foreign troops

were needed in Beijing. On June 6, 1900, and again on June 8, they sent requests to the Zongli Yamen, with both being turned down. A separate request by the German Minister, Clemens von Ketteler, to allow German troops to take control of the Beijing railway station also was turned down. On June 10, 1900,

the Chinese government barred the foreign legations from using the telegraph line that linked to Tianjin. In one of the last transmissions from the Legation Quarter, British Minister Claude MacDonald asked British Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour in Tianjin to send more troops, with the message, “Situation extremely grave; unless arrangements are made for

immediate advance to Beijing, it will be too late.” And with the subsequent severing of the telegraph line between Beijing and Kiachta (in Russia) on June 17, 1900, for nearly two months thereafter, the Legation Quarter in Beijing would be cut off from the outside world.

On June 11, 1900, the Japanese diplomat, Sugiyama Akira, was killed by Chinese troops in a Beijing street. Then on June 12 or 13, two Boxers entered the Legation Quarter and were confronted by Ketteler, the German Minister, who drove one away and captured the other; the latter soon was killed

under unclear circumstances. Later that day, thousands of Boxers stormed into Beijing and went on a rampage, killing Chinese Christians, burning churches, destroying houses, and looting properties. In the next few days, skirmishes broke out between foreign legation troops, and Boxers with the support of anti-foreigner government units. On June 15, 1900, British and German soldiers dispersed Boxers who attacked a church, and rescued the trapped Christians inside; two days later (June 17), an armed clash broke out between German–British–Austro-Hungarian units and Boxer–anti-foreigner government troops.

The Belgian legation was evacuated, as were those of Austria-Hungary, the Netherlands, and Italy,

when they came under Boxer attack. By this time, the Christian missions scattered across Beijing were evacuated, with their clergy and thousands of Chinese Christians taking shelter at the Legation Quarter. Soon, the Legation Quarter was fortified,

with soldiers and civilians building barricades, trenches, bunkers, and shelters in preparation for a Boxer attack. Ultimately, in the Legation Quarter were some 400 soldiers, 470 civilians (including 149 women and 79 children), and 2,800 Chinese Christians, all of whom would be besieged in the fighting that followed. At the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) located some three miles from the Legation Quarter, some 40 French and Italian soldiers, 30 foreign Catholic clergy, and 3,200 Chinese Christians also took refuge, turning the area into a defensive fortification which also would come under siege during the conflict.

Meanwhile in Taku, in response to British Minister MacDonald’s plea for more troops to be sent to the Beijing foreign legations, on June 10, Vice-Admiral Seymour scrambled a 2,200-strong multinational force of Navy and Marine units from Britain, Germany, Russia, France, the United States,

Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary, which departed by train from Tianjin to Beijing. On the first day, Seymour’s force traveled to within 40 miles of Beijing without meeting opposition, despite the presence

of Chinese Imperial forces (which had received no orders to resist Seymour’s passage) along the way. Seymour’s force reached Langfang, where the rail tracks had been destroyed by Boxers. Seymour’s

troops dispersed the Boxers guarding the area, and work crews started repair work on the rail tracks. Seymour sent out a scouting team further on, which returned saying that more sections of the railroad at An Ting had also been destroyed. Seymour then sent a train back to Tianjin to get more supplies, but the train soon returned, its crew saying that the rail track at Yangcun was now destroyed. Having to fight off a number of Boxer attacks, his provisions running low, realizing the futility of continuing to Beijing, and now

feeling trapped on both sides, Seymour called off the expedition and turned the trains back, intending to return to Tianjin.

Elsewhere at this point, the Boxer crisis deteriorated even further. On June 15, 1900, at the Yellow Sea where Alliance ships were on high alert, and were awaiting further developments, allied naval commanders became alarmed when Qing forces began fortifying the Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho River, as well as setting mines on the river and torpedo tubes at the forts. For Alliance commanders, these actions threatened to cut off allied communication and supply lines to Tianjin, threatening the foreign enclave at Tianjin and Legation Quarter at Beijing, as well as Seymour’s

force. The foreign alliance had had no communication with the Seymour force for several days. Alliance commanders then issued an ultimatum demanding that the Taku Forts be surrendered to them, which the Qing naval command rejected. Early

on June 17, 1900, fighting broke out at the Taku Forts, with Alliance forces (except the U.S.

command, which chose not to participate) launching a naval and ground assault that seized control of the forts.

War

For the Chinese government, the Allied attack on the Taku Forts constituted an act of war. The Qing then turned its position invariably on the side of the Boxers. Up to this point, the Qing court was unsure about its position regarding the Boxers, and Empress Dowager Cixi vacillated between the two opposing factions in her court: the ultra-conservatives who were pro-Boxer, and the reformists who were pro-foreigner. The dilemma faced by the Qing government was that despite the Boxers’ professed loyalty to the monarchy, they still could pose a threat to the monarchy, as all secret societies in the past had. But if indeed the Boxers were loyal, the Qing court could use their hatred of foreigners to rid China

of foreign influences. After the allied action on the Taku Forts, Empress Dowager Cixi took a firm stand in support of the Boxers, and ordered her armies to resist the foreigners.

On June 18, 1900, one day after the attack on the Taku Forts, German soldiers at Langfang were attacked by the anti-foreign Chinese Rear Army, more commonly known as “Gansu Braves”, which was composed of Chinese Muslims. This attack by Chinese regular troops further convinced Seymour to call off his advance to Beijing (Seymour had launched his expedition on the belief that he would face only Boxers). Then finding that more sections of the

rail tracks had been destroyed at Yangcun, Seymour’s

force abandoned the trains there and proceeded to move by foot toward Tianjin. At the Peiho River,

they seized a number of Chinese river junks, which they used to carry their wounded men, supplies, and heavy weapons. In the next several days, Seymour and his men faced numerous Boxer attacks, and also soon became low on food and ammunitions. On June 23, they fortuitously came upon the weakly defended Xigu fort located six miles from Tianjin, which they seized and then took refuge in. Subsequently, they were rescued on June 25, 1900 by an Alliance relief

force sent from Tianjin.

Meanwhile in Beijing, the situation facing the foreigners and Chinese Christians in the Legation

Quarter worsened. On June 19, 1900, the Qing government ordered the foreigners to leave Beijing within 24 hours under the protection of Chinese troops. Most of the foreign envoys were ready to comply, but they requested an audience with the Zongli Yamen for 9 AM the next day (June 20).

When the proposed appointment passed with no reply from the Chinese, the German Minister Ketteler, who had opposed the Chinese ultimatum to leave Beijing, decided to go to the Zongli Yamen to confront the Chinese officials. Ketteler ignored the warnings of the other foreign envoys not to do so. On his way there, Ketteler was shot and killed by a Chinese officer. The other foreign envoys then convened and decided to defy the Qing ultimatum and remain at the Legation Quarter. They now distrusted the Qing government, and believed that their lives would be in danger if they left the Legation Quarter.

The next day, June 21, 1900, the Qing court issued a series of decrees which the foreign powers saw as a declaration of war against them. In particular, the foreign powers were rankled by certain hostile statements in the Qing decrees, including the

lines, “We should fight this war in a big way… In province adjacent to Peking and Shandong, hundreds of thousands of Boxers have gathered on [their] free will, even…boys would take up weapons to safeguard the homeland. …it is not difficult to put out the foreigners’ fierce fire, to showcase the might of our nation. The royal court will generously reward those who fight bravely on the front line, [and] will also reward those who donate money in preparation of the war. The royal court will immediately execute traitors who escape from the battlefield or anyone who collaborates with the enemy”

As a result, a state of war existed, as Qing and Boxer forces laid siege to the Legation Quarter. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia.)

June 17, 2020

June 17, 1900 – Boxer Rebellion: The Taku Forts in Tianjin, China fall to Western Allied and Japanese forces

Foreign spheres of influence in China in the early 1900s

On June 15, 1900, at the Yellow Sea where the Alliance (the Western Powers and Japan) warships were on high alert, and were awaiting further developments, allied naval commanders became alarmed when Qing forces began fortifying the Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho River, as well as setting mines on the river and torpedo tubes at the forts. For Alliance commanders, these actions threatened to cut off allied communication and supply lines to Tianjin, threatening the foreign enclave at Tianjin and Legation Quarter at Beijing, as well as Seymour’s force. The foreign alliance had had no communication with Seymour’s force for several days. Alliance commanders then issued an ultimatum demanding that the Taku Forts be surrendered to them, which the Qing naval command rejected. Early on June 17, 1900, fighting broke out at the Taku Forts, with Alliance forces (except the U.S. command, which chose not to participate) launching a naval and ground assault that seized control of the forts.

Background of the Boxer Rebellion

By May 1900, thousands of Boxers (members of the secret society called “Righteous and Harmonious Fists”) were occupying areas around Beijing, including the vital Beijing-Tianjin railway line. They attacked villages, killed local officials, and destroyed government infrastructures. The violence alarmed the foreign diplomatic community in Beijing. The foreign diplomats, their staff, and families in Beijing had their offices and residences located at the Legation Quarter, located south of the city. The Legation Quarter consisted of diplomatic missions from eleven countries: Britain, France, Russia, United States, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Japan, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Spain.

In May 1900, the foreign diplomats asked the Qing government that foreign troops be allowed to be posted at the Legation Quarter, which was denied. Instead, the Chinese government sent Chinese policemen to guard the legations. But the foreign envoys persisted in their request, and on May 30, 1900, the Chinese Foreign Ministry (Zongli Yamen) allowed a small number of foreign troops to be sent to Beijing.

On May 31, 1900, some 450 Alliance sailors and Marines were landed from ships from eight countries and sent by train from Taku to Beijing. But as the situation in Beijing continued to deteriorate, the foreign diplomats felt that more Alliance troops were needed in Beijing. On June 6, 1900, and again on June 8, they sent requests to the Zongli Yamen, with both being turned down. A separate request by the German Minister, Clemens von Ketteler, to allow German troops to take control of the Beijing railway station also was turned down. On June 10, 1900, the Chinese government barred the foreign legations from using the telegraph line that linked to Tianjin. In one of the last transmissions from the Legation Quarter, British Minister Claude MacDonald asked British Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour in Tianjin to send more troops, with the message, “Situation extremely grave; unless arrangements are made for immediate advance to Beijing, it will be too late.” And with the subsequent severing of the telegraph line between Beijing and Kiachta (in Russia) on June 17, 1900, for nearly two months thereafter, the Legation Quarter in Beijing would be cut off from the outside world.

On June 11, 1900, the Japanese diplomat, Sugiyama Akira, was killed by Chinese troops in a Beijing street. Then on June 12 or 13, two Boxers entered the Legation Quarter and were confronted by Ketteler, the German Minister, who drove one away and captured the other; the latter soon was killed

under unclear circumstances. Later that day, thousands of Boxers stormed into Beijing and went on a rampage, killing Chinese Christians, burning churches, destroying houses, and looting properties. In the next few days, skirmishes broke out between foreign legation troops, and Boxers with the support of anti-foreigner government units. On June 15, 1900, British and German soldiers dispersed Boxers who attacked a church, and rescued the trapped Christians inside; two days later (June 17), an armed clash broke out between German–British–Austro-Hungarian units and Boxer–anti-foreigner government troops.

The Belgian legation was evacuated, as were those of Austria-Hungary, the Netherlands, and Italy,

when they came under Boxer attack. By this time, the Christian missions scattered across Beijing were evacuated, with their clergy and thousands of Chinese Christians taking shelter at the Legation Quarter. Soon, the Legation Quarter was fortified,

with soldiers and civilians building barricades, trenches, bunkers, and shelters in preparation for a Boxer attack. Ultimately, in the Legation Quarter were some 400 soldiers, 470 civilians (including 149 women and 79 children), and 2,800 Chinese Christians, all of whom would be besieged in the fighting that followed. At the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) located some three miles from the Legation Quarter, some 40 French and Italian soldiers, 30 foreign Catholic clergy, and 3,200 Chinese Christians also took refuge, turning the area into a defensive fortification which also would come under siege during the conflict.

Meanwhile in Taku, in response to British Minister MacDonald’s plea for more troops to be sent to the Beijing foreign legations, on June 10, Vice-Admiral Seymour scrambled a 2,200-strong multinational force of Navy and Marine units from Britain, Germany, Russia, France, the United States, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary, which departed by train from Tianjin to Beijing. On the first day, Seymour’s force traveled to within 40 miles of Beijing without meeting opposition, despite the presence

of Chinese Imperial forces (which had received no orders to resist Seymour’s passage) along the way. Seymour’s force reached Langfang, where the rail tracks had been destroyed by Boxers. Seymour’s troops dispersed the Boxers guarding the area, and work crews started repair work on the rail tracks. Seymour sent out a scouting team further on, which returned saying that more sections of the railroad at An Ting had also been destroyed. Seymour then sent a train back to Tianjin to get more supplies, but the train soon returned, its crew saying that the rail track at Yangcun was now destroyed. Having to fight off a number of Boxer attacks, his provisions running low, realizing the futility of continuing to Beijing, and now

feeling trapped on both sides, Seymour called off the expedition and turned the trains back, intending to return to Tianjin.

Aftermath

For the Chinese government, the Allied attack on the Taku Forts constituted an act of war. The Qing then turned its position invariably on the side of the Boxers. Up to this point, the Qing court was unsure about its position regarding the Boxers, and Empress Dowager Cixi vacillated between the two opposing factions in her court: the ultra-conservatives who were pro-Boxer, and the reformists who were pro-foreigner. The dilemma faced by the Qing government was that despite the Boxers’ professed loyalty to the monarchy, they still could pose a threat to the monarchy, as all secret societies in the past had. But if indeed the Boxers were loyal, the Qing court could use their hatred of foreigners to rid China of foreign influences. After the allied action on the Taku Forts, Empress Dowager Cixi took a firm stand in support of the Boxers, and ordered her armies to resist the foreigners. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia.)

June 16, 2020

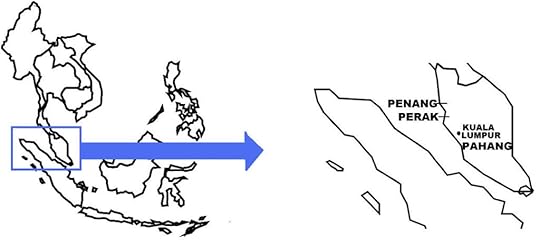

June 16, 1948 – Malayan Emergency: Three British plantation managers are killed by armed bands of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM)

On June 12, 1948, three European plantation managers were killed by armed militias of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM). British authorities declared a state of emergency throughout Malaya (now part of modern-day Malaysia), which essentially was a declaration of war against the CPM. What ensued was a twelve-year conflict (1948-1960) that became known as the Malayan Emergency, the British calling it an “emergency” so that business establishments that suffered material losses as a result of the fighting could make insurance claims, which the same would be refused by insurance companies if Malaya were placed under a state of war.

Background

On December 7, 1941, with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, World War II broke out in the Asia-Pacific. Simultaneously, Japan launched an invasion of Southeast Asia. In Malaya, the British government and the CPM formed a tactical alliance, with the British military training over 150 CPM fighters who subsequently formed the core of the anti-Japanese resistance movement. In Europe, Britain itself was

fighting for its own survival and consequently was unable to adequately defend Malaya and Singapore,

which fell to the Japanese in January-February 1942. Some 130,000 British and other allied troops were taken prisoner.

However, several British soldiers in Malaya who escaped capture retreated to the jungles (some 80% of Malaya was covered in dense mountainous rainforests) where they reorganized as an anti-Japanese resistance group that carried out guerilla operations against the Japanese occupation. Similarly, the CPM, led by its British Army-trained fighters, fled to the jungles, and formed a militia, the Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), which conducted guerilla warfare, attacking Japanese patrols and outposts and sabotaging militarily important infrastructures.

The MPAJA became a large, potent fighting force that spread all across the Malayan Peninsula. It achieved success primarily because it drew great support from the ethnic Chinese population, which was being subjected by the Japanese to severe cruelty. During the war, tens of Chinese were killed by the Japanese, their properties and businesses seized, and hundreds of thousands of others forced to flee from their homes. By contrast, Malayans and

ethnic Indians were spared abuse, and Malays in particular were co-opted by the Japanese authorities into carrying out civilian, police and security functions. The Japanese also stoked the nationalist aspirations of Malays, promising them some form of Malayan self-rule.

The pro-British guerilla groups and the MPAJA were tactical allies, but they generally operated separately of each other. By late 1943, a firmer alliance was established between them when the British military, using commandos who infiltrated Malaya and established contact with the MPAJA, promised to provide weapons to the Malayan communist guerillas in exchange for the MPAJA coming under British military authority. The promised weapons were delivered in 1945 as Japanese rule in Malaya was waning, and the MPAJA hid underground some of these arms shipments for future use.

On August 14, 1945, the Asia-Pacific theatre of World War II ended when Japan announced its decision to surrender. A formal ceremony of surrender was made three weeks later, on September 2, 1945. In Malaya, the Japanese Army surrendered to the returning British forces on September 4 (in Penang) and September 13 (in Kuala Lumpur), 1945. On September 12, the British installed a military government, the British Military Administration (BMA), to replace the pre-war civilian colonial government that had administered Malaya. British

authorities were hard-pressed to restore normalcy in the immediate post-war period: the Malayan economy was devastated, the tin and rubber industries were inoperational, and poverty and unemployment were rampant. Agricultural infrastructures were export-oriented and not directed toward growing food for the local population, leading to widespread food shortages. Furthermore, banditry, criminality, and a general lawlessness ruled the countryside.

The British recognized the MPAJA’s war-time efforts, leading to joint celebratory parades and the British granting official status to the Malayan communists’ guerilla units. MPAJA fighters were paid a salary and given supplies and provisions. In the post-war period, the MPAJA exacted vengeance on war-time collaborators in the towns and villages. Also in response to the anarchic conditions, hard-line communist elements wanted to overthrow the

colonial government, but the MCP leadership decided to cooperate with the British, and acquiesced to an order by the British military to disband MPAJA

guerilla units. However, some MPAJA units refused to disband, and although many weapons were turned in, many more were hidden in homes or buried in the ground.

By 1947, the British were making progress in Malaya’s post-war reconstruction: infrastructures were being restored or rebuilt, and the peninsula’s vital tin and rubber industries were rehabilitated. At this time, the CPM operated openly, tacitly tolerated by the British because of their war-time alliance. In March 1947, the CPM came under the leadership of Chin Peng, a hard-line communist who increased

anti-British militant actions. Operating through the labor movement (which it controlled), the CPM organized strikes and labor actions aimed at disrupting the Malayan economy, and destabilizing

British rule by fomenting local unrest. In this way, it was hoped that a general uprising would follow, leading to the end of British rule and its replacement with a CMP-led communist government. Under CPM instigation, hundreds of strikes were launched, and labor leaders and workers who refused to participate were killed.

War

On June 12, 1948, three European plantation managers were killed by armed bands, forcing

British authorities to declare a state of emergency throughout Malaya, which essentially was a declaration of war on the CPM. The British called the conflict, which lasted 12 years (1948-1960), an “emergency” so that business establishments that suffered material losses as a result of the fighting, could make insurance claims, which the same would be refused by insurance companies if Malaya were placed under a state of war.

The state of emergency, which was applied first to Perak State (where the murders of the three plantation managers occurred) and then throughout Malaya in July 1948, gave the police authorization to arrest and hold anyone, without the need for the judicial process. In this way, hundreds of CPM cadres were arrested and jailed, and the party itself was outlawed in July 1948. The murders of the three plantation managers are disputed: British authorities blamed the CPM, while Chin Peng denied CPM involvement, arguing that the CPM itself was caught by surprise by the events and was unprepared for war, and that he himself barely avoided arrest in the intensive government crackdown that followed the killings. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia.)

June 15, 2020

June 15, 1940 – World War II: The start of Operation Aerial, where the Allies evacuate France following the fall of Paris

On June 15, 1940, with France stating its intent to seek a ceasefire with Germany, the British High Command activated Operation Aerial, a second Allied evacuation, this time through western France. Conducted until June 25, the British Royal Navy used the ports of Cherbourg, Saint-Malo, Brest, Saint-Nazaire, La Pallice, Le Verdon, Bordeaux, and Bayonne to evacuate some 190,000 Allied troops. The greatest Allied loss during this evacuation occurred on June 17 when the British ship, RMS Lacastria, was sunk by German planes, killing some 5,000 Allied troops and becoming Britain’s worst maritime disaster.

By then, the Battle of France was winding down. On June 13, 1940 in a Supreme War Council meeting in Tours, the French and British governments acknowledged that the war was lost. As both parties had agreed months earlier that neither side could seek a separate peace with Germany without the other side’s consent, French Prime Minister Reynaud now asked Prime Minister Churchill to allow France

to be released from this commitment. Churchill refused, and instead proposed a political union between the two countries (Anglo-French Union) and the French government and military transferring France’s seat of power to its colonies in North Africa where they would continue the war. Both proposals were rejected by the French government, and on June 15, Reynaud resigned as Prime Minister, and was succeeded by World War I hero, Marshall Philippe Petain, who immediately made a radio broadcast indicating his intention to seek an armistice with Germany.

On June 21, 1940, French and German representatives met at the Forest of Compeigne,

some 40 miles north of Paris and the location purposely chosen by Hitler, for negotiations, and inside the railway carriage where the 1918 Armistice of World War I had taken place. Hitler led the German delegation but later abruptly departed, and left the negotiations to his generals as a sign of contempt to the French delegates .

The French viewed the German demands for an armistice as unacceptably excessive; but as the Germans were firm and threatened to restart hostilities, the French relented, and the armistice was signed on June 22. The next day, negotiations between the French and Italians were held in Rome, leading to a separate armistice on June 24. On June 25, 1940, both armistices came into effect, officially ending hostilities.

Total casualties in the campaign in France and the Low Countries were: Germans – 155,000 (27,000 killed, 110,000 wounded, 18,000 wounded); French – 2.1 million (90,000 killed, 200,000 wounded, and 1.8

million captured), British – 68,000 (10,000 killed), Belgian – 23,000, Dutch – 10,000, and Polish – 6,000.

Aftermath

Despite Germany’s overwhelming military position at the end of hostilities, the armistice negotiations were conducted with consideration of other realities: for Hitler, that the French government and army could very well move to French colonies in North Africa from where they could continue the war; and for the

French government, that it wanted to remain in France but only if the Germans did not impose “dishonorable or excessive” terms. Terms that were deemed unacceptable included the following: that all of France would be occupied, that France should surrender its navy, or that France should relinquish its (vast) colonial territories.

Not only did Hitler not impose these terms, in fact, he desired that France remain a sovereign state for diplomatic and practical reasons: in the first case, France had ostensibly switched sides in the war,

isolating Britain; and in the second case, France, with its large navy, would maintain its global colonial empire, which Germany could not because it did not

have enough ships.

Thus, in the armistice agreement, France was allowed to remain a fully sovereign state, with its mainland territory and colonial possessions intact, with some exceptions: Alsace-Lorraine became part

of the Greater German Reich, although not formally annexed into Germany; and Nord and Pas-de-Calais were attached to Belgium in the “German Military Administration of Belgium and Northern France”. France also retained its navy, but which was demobilized and disarmed, as were the other branches of the French armed forces.

Because of the continuing hostilities with Britain, as part of the armistice agreement, the German Army occupied the northern and western sections of France (some 55% of the French mainland), where it imposed military rule. The occupation was intended to be temporary until such time that Germany had defeated or had come to terms with Britain, which both the French and German governments believed was imminent. The Italian military also occupied a small area in the French Alps. In the rest of France (comprising 45% of the French mainland), which was not occupied and thus called zone libre (“free zone”), on July 10, 1940, the French government formed a new polity called the “French State” (French: État français), which dissolved the French Third Republic, and was led by Petain as Chief of State. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century Volume 6 – World War II in Europe.)

June 14, 2020

June 14, 1940 – World War II: The Soviet Union delivers an ultimatum to Lithuania

On June 14, 1940, the Soviet government delivered an ultimatum to Lithuania to allow the entry of Soviet troops into Lithuanian territory and for Lithuania to form a new pro-Soviet government. Nine months earlier in October 1939, the two countries had signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty which allowed the stationing of 20,000 Soviet troops in a number of bases inside Lithuania.

With Soviet forces already present in the country, on June 15, the Lithuanian government acquiesced to the ultimatum and ended its country’s independence. The Soviets then took control of the country, installed a puppet regime, and held mock elections to the legislature. The new puppet legislature proclaimed the establishment of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic and petitioned Moscow to be admitted into the Soviet Union. In August 1940, the Soviet government accepted the petition and incorporated Lithuania into the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union also signed similar mutual assistance agreements with the two other Baltic states, Estonia (September 28, 1939) and Latvia (October 5, 1939) which allowed Soviet forces to occupy strategic locations in these countries. Also in June 1940, Soviet forces occupied Estonia and Latvia; after socialist governments came to power in Soviet-controlled elections held in July 1940, Estonia and Latvia were likewise incorporated into the Soviet Union in August 1940.

June 13, 2020

June 13, 1971 – Vietnam War: The New York Times begins publication of the Pentagon Papers

On June 13, 1971, the New York Times published the first part of the top-secret document more commonly known as the Pentagon Papers.

The official title of the so-called Pentagon Papers was “Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force”, which was a top secret study conducted by the U.S. Department of Defense in 1967-1969. The final report, contained in 47 volumes of over 7,000 pages of narratives and documents, detailed U.S. political and military involvement in Vietnam since the end of World War II up until the presidencies of Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon.

The Pentagon Papers revealed that successive U.S. administrations of Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson had misled the American public regarding the extent of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In 1971, portions of the report were leaked to the New York Times, which then began publishing those portions. The U.S. government, now under President Richard Nixon, tried to restrict further publication, but was turned down by the U.S. Supreme Court. Subsequently, aside from the New York Times, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and other newspapers published portions of the report. The revelation of the Pentagon Papers came at a time when public opposition and outrage to the Vietnam War was reaching the tipping point.

In Relation to the Vietnam War

President Nixon had announced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S. ground troops to a planned military operation in Cambodia. Within days, large demonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in American cities, with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio, National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four people and wounding eight others. This incident sparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across the country. Anti-war sentiment already was intense in the United States following news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My Lai Massacre, where U.S. troops on a search and destroy mission descended on My Lai and My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including women and children.

American public outrage further was fueled when in June 1971, the New York Times began

publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officially titled: United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense), a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked to the press. The Pentagon Papers showed that successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times misled the American people regarding U.S. involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stop the document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. Supreme Court subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publication continued, and which was also later taken up by

the Washington Post and other newspapers.

June 12, 2020

June 12, 1999 – Kosovo War: UN peacekeepers enter Kosovo

On June 12, 1999, a NATO-led United Nations peacekeeping force (called KFor for Kosovo Force) entered war-torn Kosovo. KFor was tasked by the UN Security Council to maintain the peace as a result of the Kosovo War. By this time, Kosovo was facing a serious humanitarian crisis, with nearly one million civilians displaced by the fighting.

The Kosovo War (February 1998-June 1999) was fought between the Yugoslav Army and Albanian Serb militias against the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), a Kosovo Albanian rebel group. Subsequently, the KLA would gain air support from NATO and ground support from the Albanian Army.

At the outbreak of the war, Kosovo was an autonomous region of Serbia. It had two main ethnic groups: the majority Albanians (comprising 77% of the population) who desired greater autonomy from Serbia, and Kosovo Serbs (15% of the population) who wanted more political integration with Serbia.

War

In April 1996, the KLA, an extremist Albanian militia that sought to gain Kosovo’s independence by force, launched attacks against Serbian police units across Kosovo. By March 1998, as the KLA had grown in strength and were intensifying its armed operations, the Yugoslav Army entered Kosovo. Fighting occurred from March to September 1998, concentrated mostly in central-south Kosovo. The Yugoslav Army was far superior in strength, forcing the KLA to resort to guerilla warfare, such as ambushing army and security patrols, and raiding isolated military outposts. Through a tactical war of attrition, the KLA gained control of Decani, Malisevo, Orahovac, Drenica Valley, and northwest Pristina.

In September 1998, the Yugoslav Army and Kosovo Serb forces launched offensive operations in northern and central Kosovo, driving away the KLA from many areas. These offensives also turned 200,000 civilians into refugees, prompting the United Nations to call for a ceasefire and an end to the conflict.

With the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) threatening to intervene, Yugoslavia agreed to a ceasefire in October 1998. A multi-national observer team then arrived in Kosovo to monitor the

ceasefire. Fighting broke out in December 1998, however, which escalated in intensity early the next year, forcing the multi-national observer team to leave Kosovo in March 1999.

NATO became increasingly involved in the war – especially after the discovery of the bodies of 45 executed Kosovo Albanian farmers – and decided that direct military intervention was needed to end the war. In March 1999, NATO presented to Yugoslavia a proposal to station 30,000 NATO soldiers in Kosovo to monitor and maintain peace. Furthermore, the NATO force was to have free, unrestricted passage across Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav government vehemently rejected the UN proposal, calling it a violation of Yugoslavia’s territorial

sovereignty. In turn, Yugoslavia offered its own peace proposal, which was also rejected by NATO. The diplomatic impasse prompted NATO to begin military action against Yugoslavia.

On March 23, 1999, using over one thousand planes, NATO began launching massive air strikes against military installations and facilities in Yugoslavia. Later, NATO targeted Yugoslav Army units as well. NATO planes also attacked public

infrastructures such as roads, railways, bridges, telecommunications systems, power stations, schools, and hospitals. Many unintended targets were hit as well, such as a convoy of Kosovo

Albanian refugees, a Kosovo prison, a Serbian television facility, and the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade. The NATO air attacks against non-military

targets drew widespread international condemnation.

In retaliation for the air strikes, the Yugoslav Army and Kosovo Serb forces expelled Kosovo Albanians from their homes. Within a few weeks, some 750,000 Kosovo Albanians had been forced to flee to neighboring Albania, Macedonia, and Montenegro.

On June 3, the government of Yugoslavia,

persuaded by Russia, yielded to strong international pressure and agreed to accept NATO’s peace

proposal. Thereafter, Yugoslav forces withdrew from Kosovo. NATO then ended its air strikes against Yugoslavia and sent a peacekeeping force, under a UN mandate, to enter Kosovo. Russia, which was Yugoslavia’s staunchest supporter during the war, also deployed its own peacekeepers in Kosovo to serve as a foil against the NATO troops. NATO and Russian peacekeepers coordinated their actions, however, to secure peace in Kosovo while avoiding unwanted confrontations between them.

About 13,000 persons died in the Kosovo War. Over one million civilians fled the fighting and became refuges, although most eventually returned to their homes after the war. Perhaps as many as 200,000 ethnic Serbs fled Kosovo in the years after the war. Yugoslavian and Kosovo Serbian political and military leaders, including KLA members, have been charged with war crimes.

In February 2008, Kosovo Albanians declared Kosovo an independent country. Serbia rejected Kosovo’s independence and has since maintained its claim to Kosovo as being an integral part of Serbian territory. While the United States, United Kingdom, and other countries recognize Kosovo’s independence, many others do not. Russia, in particular, insists that any proposed solution must be acceptable to both Serbia and Kosovo. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 1.)