Daniel Orr's Blog, page 93

July 1, 2020

July 1, 1942 – World War II: The start of the First Battle of El Alamein

On July 1, 1942, the First Battle of El Alamein began pitting the Axis (comprising German and Italian forces) against the Allies (comprising units from Britain, British India, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand). The nearly month-long battle (July 1-27, 1942) ended inconclusively, but was a strategic setback for the Axis forces as their planned further advance into Egypt (Alexandria, Cairo, and the Suez Canal) was stopped.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century (Volume 6) – World War II in Europe)

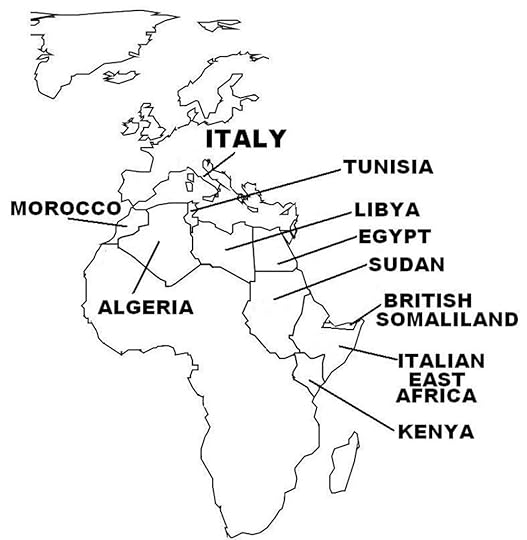

The Axis in the African Theatre of World War II

In East Africa, the Italian Army achieved success initially, launching offensives from Italian territories of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland and driving away the British from British Somaliland, and seizing some border regions in British-controlled Sudan and Kenya. At this stage of World War II, Britain’s overseas possessions were extremely vulnerable, as British efforts were diverted to the homeland to confront the ongoing German air offensives (Battle of Britain, separate article). But with the Luftwaffe scaling down operations in Britain as 1941 progressed, the British soon counter-attacked in East Africa, throwing back the Italians and regaining lost territory, and then capturing Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland, and forcing the surrender of the remaining Italian forces in East Africa.

In North Africa, which was a major battleground in World War II, the Italian Army also achieved some success initially, launching from Libya and advancing 62 miles (100 km) into British-administered Egypt in September 1940, while taking advantage of the desperate situation of the British in the ongoing Battle of Britain. In December 1940, the British counter-attacked and threw back the much

larger Italian forces into Libya, taking some 130,000 Italian prisoners and advancing 500 miles (800 km) to El Agheila. Now poised to expel the Italian Army from North Africa altogether, the British were forced to halt their

offensive to transfer some of their troops to Greece, to help contain a new Italian offensive there.

The pause allowed Hitler to come to the aid of his beleaguered ally Mussolini, in February 1941, sending the first units of the

German Afrika Korps led by General Erwin Rommel, to fight alongside the Italian forces, which also were bolstered by reinforcements arriving from Europe. A see-saw battle ensued for over a year, with one side pushing the other hundreds of miles through the desert, and then the other side launching a counter-offensive that threw back the other and penetrating deep into enemy territory.

Then in October-November 1942, the British 8th Army decisively defeated the German-Italian force at the Second Battle of El

Alamein, forcing the Axis to retreat 1,600 miles (2,600 km) to the Libya-Tunisia border.

Also in November 1942, an American-British force landed at Morocco and Algeria,

which were administered by Vichy France. After a short period of fighting, the

Americans and British succeeded in persuading French forces there to switch sides to the Allies. American-British-French forces from the west and the British 8th Army from the east then attacked and encircled the German-Italian forces in Tunisia, and in May 1943, expelled the Axis from North Africa. As a result, Italy lost all its African territories.

June 30, 2020

June 30, 1936 – Interwar period: Ethiopia appeals to the League of Nations against the Italian invasion

On June 30, 1936, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie addressed the League of Nations appealing for aid against the Italian invasion of his country. The League of Nations condemned the Italian invasion, but imposed only partial and ineffective economic sanctions on Italy.

In October 1935, the Italian Army invaded independent Ethiopia, conquering the African nation by May 1936 in a brutal campaign that included the Italians using poison gas on both soldiers and civilians. In the aftermath, Italy annexed Ethiopia into the newly formed Italian East Africa, which included Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. Italy also controlled Libya in North Africa as a colony.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 6 – World War II in Europe)

Mussolini and His Quest for an Italian Empire

In the midst of political and social unrest in October 1922, Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party came to power in Italy, with Mussolini being appointed as Prime Minister by Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III. Mussolini, who was popularly called “Il Duce” (“The Leader”), launched major infrastructure and social programs that made him extremely popular among his people. By 1925-1927, the Fascist Party was the only legal political party, the Italian legislature had been abolished, and Mussolini wielded nearly absolute power, with his government a virtual dictatorship.

By the late 1920s through the 1930s, Mussolini pursued an overtly expansionist foreign policy. He stressed the need for Italian domination of the Mediterranean region and

territorial acquisitions, including direct control of the Balkan states of Yugoslavia, Greece,

Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania, and a sphere of influence in Austria and Hungary, and colonies in North Africa. Mussolini envisioned a modern Italian Empire in the likeness of the

ancient Roman Empire. He explained that his empire would stretch from the “Strait of Gibraltar [western tip of the Mediterranean Sea] to the Strait of Hormuz [in modern-day Iran and the Arabian Peninsula] (Figure 20)”. Although not openly stated, to achieve this

goal, Italy would need to overcome British and French naval domination of the Mediterranean

Sea.

Furthermore, in the aftermath of World War I, a strong sentiment regarding the so-called “mutilated victory” pervaded among many Italians about what they believed was their country’s unacceptably small territorial gains in the war, a sentiment that was exploited by the Fascist government. Mussolini saw his empire as fulfilling the Italian aspiration for “spazio vitale” (“vital space”), where the acquired territories would be settled by Italian colonists to ease the overpopulation in the homeland. Mussolini’s government actively promoted programs that encouraged large family sizes and higher birth rates.

Mussolini also spoke disparagingly about Italy’s geographical location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about how it was

“imprisoned” by islands and territories controlled by other foreign powers (i.e. France and Britain), and that his new empire would include territories that would allow Italy direct access to the Atlantic Ocean in the west and the Indian Ocean in the east.

In October 1935, the Italian Army invaded independent Ethiopia, conquering the African nation by May 1936 in a brutal campaign that included the Italians using poison gas on civilians and soldiers alike. Italy then annexed Ethiopia into the newly formed Italian East Africa, which included Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. Italy also controlled Libya in North Africa as a colony.

The aftermath of Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia saw a rapprochement in Italian-Nazi German relations arising from Hitler’s support of Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. In turn, Mussolini dropped his opposition to Germany’s annexation of Austria. Throughout the 1920s-1930s, the major European powers Britain, France, Italy, the Soviet Union and Germany, engaged in a power struggle and formed various alliances and counter-alliances among

themselves, with each power hoping to gain some advantage in what was seen as an inevitable war. In this power struggle, Italy

straddled the middle and believed that in a future conflict, its weight would tip the scales for victory in its chosen side.

In the end, it was Italy’s ties with Germany

that prospered; both countries also shared a common political ideology. In the Spanish Civil War (July 1936-April 1939), Italy and Germany supported the rebel Nationalist forces of General Francisco Franco, who emerged victorious and took over power in Spain. In October 1936, Italy and Germany formed an alliance called the Rome-Berlin Axis. Then in 1937, Italy joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had been signed by Germany and Japan in November 1936. In April 1939, Italy

moved one step closer to forming an empire by invading Albania, seizing control of the Balkan nation within a few days. In May 1939, Mussolini and Hitler formed a military alliance, the Pact of Steel. Two months earlier (March 1939), Germany completed the dissolution and partial annexation of Czechoslovakia. The alliance between Germany and Italy, together with Japan, reached its height in September 1940, with the signing of the Tripartite Pact,

and these countries came to be known as the Axis Powers.

On September 1, 1939 World War II broke out when Germany attacked Poland, which immediately embroiled the major Western powers, France and Britain, and by September 16 the Soviet Union as well (as a result of a non-aggression pact with Germany, but not as an enemy of France and Britain). Italy did not enter the war as yet, since despite Mussolini’s frequent blustering of having military strength capable of taking on the other great powers, Italy in fact was unprepared for a major European war.

Italy was still mainly an agricultural society, and industrial production for war-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for vital items such as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind the other western powers. In military capability, Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostly obsolete by the start of World War II, although the large Italian Navy was ably powerful and

possessed several modern battleships. Cognizant of these deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts to building up Italian military strength, and by 1939, some 40% of the national budget was allocated to the armed forces. Even so, Italian military planners had projected that its forces would not be fully prepared for war until 1943, and therefore the sudden start of World War II came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

In April-June 1940, Germany achieved a succession of overwhelming conquests of Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium,

Luxembourg, and France. As France verged on defeat and with Britain isolated and facing possible invasion, Mussolini decided that the war was over. In an unabashed display of

opportunism, on June 10, 1940, he declared war on France and Britain, bringing Italy into World War II on the side of Germany, and

stating, “I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought”.

June 29, 2020

June 29, 1950 – Korean War: The U.S. Navy blockades the Korean coast

On June 29, 1950, United States President Harry S. Truman ordered a naval blockade of the Korean coastline following the start of the Korean War. At the same time, he authorized the deployment of U.S. troops to assist the beleaguered South Korean-American forces defending South Korea. The U.S. Air Force was also instructed to launch bombing raids on military targets in North Korea.

North Korea launched its invasion of South Korea four days earlier, June 25, and rapidly gained territory, pushing back the small South Korean-American defenders. The United Nations Security Council, upon the request of the United States, passed a resolution urging UN member states to come to the aid of South Korea.

Some key battle sites during the Korean War

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath of the Korean War

An armistice was signed on July 19, 1953. Eight days later, July 27, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement, which ended the war. A ceasefire came into effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed. The Korean War was over.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldiers killed, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; North Korean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which included Chairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying). Civilian casualties were 2 million for South Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Korean refugees who had moved to South Korea. Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forces conducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to be

supporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea, during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militias

executed some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupation

of South Korea, also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries”

(politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians who refused to join the North Korean Army.

Under the armistice agreement, the frontline at the time of the ceasefire became the armistice line, which extended from coast to coast some 40 miles north of the 38th parallel in the east, to 20 miles south of the

38th parallel in the west, or a net territorial loss of 1,500 square miles to North Korea. Three days after the agreement was signed, both sides withdrew to a distance of two kilometers from the ceasefire line, thus creating a four-kilometer demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the opposing forces.

The armistice agreement also stipulated the repatriation of POWs, a major point of contention during the talks, where both parties

compromised and agreed to the formation of an independent body, the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission (NNRC), to implement the exchange of prisoners. The NNRC, chaired by General K.S. Thimayya from India, subsequently launched Operation Big Switch, where in August-December 1953, some 70,000 North Korean and 5,500 Chinese POWs, and 12,700 UN POWs (including 7,800 South Koreans, 3,600 Americans, and 900

British), were repatriated. Some 22,000

Chinese/North Korean POWs refused to be repatriated – the 14,000 Chinese prisoners who refused repatriation eventually moved to the Republic of China (Taiwan), where they were given civilian status. Much to the astonishment of U.S. and British authorities, 21 American and 1 British (together with 325 South Korean) POWs also refused to be

repatriated, and chose to move to China.

All POWs on both sides who refused to be repatriated were given 90 days to change their minds, as required under the armistice agreement.

The armistice line was conceived only as a separation of forces, and not as an international border between the two Korean states. The Korean Armistice Agreement called on the two rival Korean governments to negotiate a peaceful resolution to reunify the Korean Peninsula. In the international Geneva Conference held in April-July 1954, which aimed to achieve a political settlement to the recent war in Korea (as well as in Indochina, see First Indochina War, separate article), North Korea and South Korea, backed by their major power sponsors, each proposed a political settlement, but which was unacceptable to the other side. As a result, by the end of the Geneva Conference on June 15, 1953, no resolution was adopted, leaving the Korean issue unresolved.

Since then, the Korean Peninsula has remained divided along the 1953 armistice line, with the 248-kilometer long DMZ, which was originally meant to be a military buffer zone, becoming the de facto border between North Korea and South Korea. No peace treaty was signed, with the armistice agreement being a ceasefire only. Thus, a state of war officially continues to exist between the two Koreas. Also as stipulated by the Korean Armistice Agreement, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) was established, comprising contingents from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland, tasked with ensuring that no new foreign military personnel and weapons are

brought into Korea.

Because of the constant state of high tension between the two Korean states, the DMZ has since remained heavily defended and is the most militarily fortified place on Earth.

Situated at the armistice line in Panmunjom is the Joint Security Area, a conference center where representatives from the two Koreas hold negotiations periodically. Since the end of the Korean War, there exists the constant threat of a new war, which is exacerbated

by the many incidents initiated by North Korea

against South Korea. Some of these incidents include: the hijacking by a North Korean agent of a South Korean commercial airliner in

December 1969; the North Korean abductions of South Korean civilians; the failed assassination attempt by North Korean commandos of South Korean President Park Chung-hee in January 1968; the sinking of a South Korean naval vessel, the ROKS Cheonon, in March 2010, which the South Korean government blamed was caused by a torpedo fired by a North Korean submarine (North Korea denied any involvement), and the discovery of a number of underground tunnels

along the DMZ which South Korea has said were built by North Korea to be used as an invasion route to the south.

Furthermore, in October 2006, North Korea announced that it had detonated its first nuclear bomb, and has since stated that it possesses nuclear weapons. With North Korea aggressively pursuing its nuclear weapons capability, as evidenced by a number of nuclear tests being carried out over the years, the peninsular crisis has threatened to expand to regional and even global dimensions.

Western observers also believe that North Korea has since been developing chemical and biological weapons.

North Korea and South Korea

Since the end of the war, the two Koreas

have pursued totally divergent paths. North Korea, a Marxist state, implemented a centrally planned policy, nationalized industries, lands, and properties, and collectivized agriculture. During the Japanese occupation of the Korean Peninsula, industrialization (and thus also wealth and power) was concentrated in the

north. Following the Korean War, North Korea focused on heavy industrialization, particularly power-generating, mineral, and chemical industries, which was helped greatly by large technical and financial assistance from the Soviet Union, China, and other Eastern Bloc countries. It was also determined to achieve juche (self-reliance). Simultaneously, North Korea funneled a large share of its national budget to building a large Army. To fund both its large industrial and military programs, the government borrowed heavily from foreign sources. But after the 1973 global oil crisis, the price of minerals fell in the world market, negatively affecting North Korea which was unable to pay its large foreign debt. By the mid-1980s, it failed to meet most of its debt repayment obligations, and defaulted.

By the late 1980s, socialism was waning across eastern and central Europe, with Eastern Bloc countries shedding off Marxism-Leninism and centrally planned economies, and adopting Western-style democracy and a free market system. In December 1991, the Soviet

Union disintegrated. North Korea, suddenly without Soviet financial support, went into an economic freefall. Also in the 1990s, widespread famine in North Korea caused by various factors, including failed government policies, massive flooding in 1995-1996, a drought in 1997, and the loss of Soviet support, led to mass starvation. The number of deaths from the famine is estimated at between 500,000 and 2 million people, even up to 3 million. The international community responded to the calamity, and North Korea received food and other humanitarian aid from the UN, China, South Korea, the United States, and other countries. At present, North Korea, when measured in terms of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), ranks among the poorest and least developed countries in the world.

By contrast, South Korea, which pursued Western-style democracy and a free market economy, initially suffered from severe political, social, and economic difficulties in the years following the Korean War. The country, which traditionally had an impoverished agricultural economy, was nearly exclusively dependent on U.S. financial aid (up to 90%). In October 1953, South Korea and the United States signed a Mutual Defense Treaty.

In May 1961, General Park Chung-hee came to power in South Korea through a military coup. Soon becoming president, Park began the dramatic economic transformation of South Korea. Within a few decades, the country had become a regional and global economic powerhouse, its rapid growth being called the “Miracle on the Han River” (referring to the Han River, which flows through Seoul).

Because of the prevailing unstable security climate, President Park imposed authoritarian rule and a one-party state system. His regime

suppressed political opposition, censored the press, and committed grave human rights violations. But at the same time, his government initiated large-scale modernization and export-centered industrialization. Succeeding national administrations (after President Park was assassinated in 1979) have continued the country’s economic growth. By the 1990s, South Korea had become one of Asia’s business and commercial centers, boasting a highly developed economy. South Korea has since become the world’s 12th large economy, with a GDP that is nearly forty times greater than that of North Korea.

June 28, 2020

June 28, 1942 – World War II: Germany launches “Case Blue”, an offensive into southern Russia aimed at seizing the Baku oil fields in the Caucasus

On June 28, 1942, German forces and their Axis allies launched their strategic summer offensive into southern Russia aimed at seizing control of the petroleum-rich region of the Caucasus. Operation Barbarossa of the previous year had considerably used up Germany’s oil reserves, and in late 1941, Romania, which supplied 75% of German oil needs, had warned that its oil fields might not be sufficient to continue supplying Germany’s ever-increasing requirements.

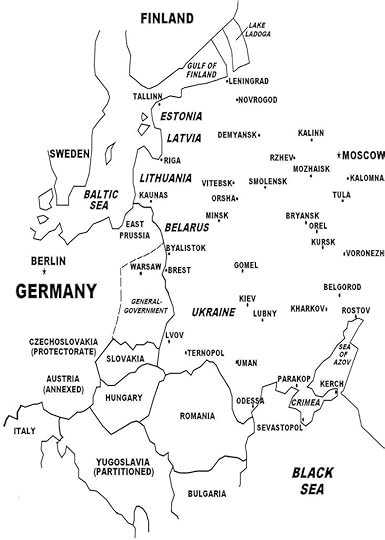

Key battle sites during Operation Barbarossa

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 6 – World War II in Europe)

Preparations

In February 1942, Hitler ordered his military high command to begin preparing for a new offensive with a less ambitious objective (than Operation Barbarossa), the capture of the Caucasus. These preparations gave rise to “Case Blue” (German: Fall Blau), the operational codename for Fuhrer Directive no. 41, issued on April 5, 1941, where Hitler laid out the plan for the German Army’s 1942 summer offensive in Russia, as follows: Army Group South would advance to the Caucasus, this operation being Case Blue’s main objective; Army Group North would capture Leningrad; and Army Group Center would take a defensive posture and hold its present position. The Directive also acknowledged that because of limited resources, only one objective would be pursued at a time; thus, the attack on the Caucasus will be launched first.

By this time, Hitler wanted to acquire the petroleum-rich region of the Caucasus, since Operation Barbarossa of the previous year had

considerably used up Germany’s oil reserves, and in late 1941, Romania, which supplied 75% of German oil needs, had warned that its oil fields might not be sufficient to continue supplying Germany’s ever-increasing requirements. The German capture of the Caucasian oil fields, particularly Baku (in Azerbaijan), which provided 80% of the Soviet

Union’s oil needs, would be devastating to Soviet industry and military. Furthermore, southern Russia had vast agricultural areas for food production, and large sources of coal, peat, and various minerals for Germany’s

military and industrial needs.

For Case Blue, German Army Group South had three field and two panzer armies, supported by contingents from its Axis partners: one field army each from Hungary and Italy, and two armies from Romania. The combined forces had 1.3 million troops (1

million German, 300,000 other Axis), 1,900 tanks, and 1,600 planes, which would launch from three points: North: German 4th Panzer Army, supported by two field armies (one German and one Hungarian) would advance from Kursk to Voronezh, and then to the Volga River and cover Case Blue’s northern flank; Center: German 6th Army, led by its mobile spearheads, would launch from Kharkov toward the Volga River near Stalingrad; and South: German 1st Panzer Army, flanked by two field armies (one German and one Hungarian) would advance toward and cross the Donets and lower Don River.

Case Blue

The Offensive

On June 28, 1942, the Wehrmacht and its allies launched Case Blue, opening a massive artillery barrage on Soviet positions all across the southern front. In the northern zone of the offensive, German 4th Panzer Army thrust from Kursk and met only light opposition from retreating units of the Soviet Bryansk Front, and reached Voronezh on July 5. German Army Group South’s Luftwaffe Air Fleet 4, which was greatly strengthened for Case Blue, proved instrumental in the rapid Axis advance all across the front. At Voronezh, German 4th Panzer Army unexpectedly became engaged in a fierce battle against determined Red Army resistance, and was able to disengage only two weeks later with the arrival of its support infantry armies that expelled Soviet forces from the town by July 24. German 4th Panzer

Army turned south to support the advance of the central sector.

June 27, 2020

June 27, 1941 – World War II: German forces capture Bialystok

On June 27, 1941, German Army Group

Center captured Bialystok from Soviet forces during the early stages of the invasion of the Soviet Union under the general offensive codenamed Operation Barbarossa. Bialystok, a Polish city, had come under Soviet control as a result of the 1939 Treaty of Non-aggression between Germany and the USSR, commonly known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The German attack was part of the broader offensive for Army Group Center to advance to the Belarusian capital of Minsk.

The Wehrmacht placed the A-A Line, which extended from Arkhangelsk in the Arctic in the north to Astrakhan in the Caspian Sea in the south, as the furthest advance of Operation Barbarossa.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 6 – World War II in Europe)

Operation Barbarossa

By mid-June 1941, the Axis forces for Operation Barbarossa were set in place, a total of some three million German (comprising 75% of the Wehrmacht) and 700,000 other Axis troops, supported with 3,300 tanks, 7,200 artillery pieces, 2,800 planes, 600,000 motor transports, and 700,000 horses, which comprised the greatest invasion force in history. This force was divided into three main bodies and their respective objectives: Army Group North, which was to advance from East Prussia toward the Baltic States and into northern Russia for its final objective, Leningrad, where it would link up with its ally, the Finnish Army; Army Group Center (constituting the main attack with the most air and armored units) would launch from Poland toward Belorussia and central Russia for its objective, Moscow; and Army Group South, which would thrust from two points, southern Poland and Romania toward the Ukraine and southern Russia and then into the Caucasus. A secondary German offensive would be made in northern Scandinavia by Army Norway for the far-north Soviet Murmansk region.

Central Sector

Also on June 22, 1941, German Army Group Center (with 1.3 million troops, 2,600 tanks, and 7,800 artillery pieces) based in Poland attacked into Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, where the uneven border arising from the 1939 partition of the country created salients whose weak flanks could be exploited by an invading force. German Army Group Center

had the greatest concentration of tanks comprising two panzer groups, as Hitler

anticipated that this sector’s campaign into Moscow would be strongly resisted by the Red

Army. To exploit the Soviet salient at Bialystok, the two panzer groups crossed the frontier in a flanking maneuver, with the 2nd Panzer Group to the south and bypassing Brest, and 3rd Panzer Group to the north advancing for Vilnius, with both groups aiming for Minsk, 400 miles to the east. Meanwhile, German Army Group Center’s three field armies also advanced north and south of the Bialystok salient, forming another set of pincers.

On June 23, 1941, a Red Army counter-attack was stopped. The next day, another Soviet counter-offensive, led by an armored force of over 1,000 tanks, advanced for Grodno to break the looming encirclement, but met disaster caused as much by fierce German air attacks as by mechanical breakdowns of the tanks and shortage of fuel. Another Soviet attack with 200 tanks on June 25 also ended in failure.

On June 27, 1941, the German 2nd and 3rd Panzer Groups met up at Minsk, and the next day, German Army Group Center’s

second pincers closed shut east of Bialystok. The trapped Soviet forces at Bialystok,

Navahrudak, and Minsk continued to resist, while elimination of these pockets by the Wehrmacht was delayed by lack of adequate German motor transports to hasten the advance of infantry units. Full encirclement of

Soviet forces also was compromised as the German 2nd Panzer, which was led by General Heinz Guderian (an advocate of armored blitzkrieg tactics), continued advancing east in contravention of Hitler’s pause order, which left gaps in the cordon that allowed Soviet units to escape. In the end, in the Bialystok-Minsk battles, although the Germans captured 300,000 Soviet troops, as well as 3,000 tanks, and 1,500 artillery pieces, some 250,000 Red Army soldiers escaped.

An annoyed Hitler faulted the panzer commanders for achieving only a partial capture of the trapped Soviets; in turn, the German commanders blamed the slow advance of the supporting infantry units. But in the aftermath, the Soviet Western Front was destroyed, with two field armies obliterated and three others severely incapacitated.

German Army Group Center then continued east toward Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. The German advance was again spearheaded by panzers, with 2nd Panzer Group advancing in the south and 3rd Panzer Group in the north with the aim of meeting up and encircling Smolensk.

On Stalin’s orders, five Soviet armies from the strategic reserve were deployed in Smolensk,

reinforcing the Soviet 13th Army there in essentially reconstituting the Soviet Western Front. The Soviets formed a new defensive line around the city, and also took up positions along the old Stalin Line along the Dnieper and Dvina rivers.

On July 6, 1941, Soviet armored units, comprising 1,500 tanks, attacked toward Lepiel, but were repulsed and nearly wiped out by a German tank and anti-tank counter-attack. Then on July 11 and the following days, the Red Army launched more counter-attacks, which all failed to stall the Germans. On July 13, German 2nd Panzer Group took Mogilev, trapping several Soviet armies. Two days later, the Germans entered Smolensk,

leading to fierce house-to-house fighting in the city. German 3rd Panzer Group, advancing from the north, was stalled by swampy terrain that was exacerbated by the seasonal rains. But in late July 1941, it too entered Smolensk,

and the two panzer groups closed shut and trapped three Soviet armies comprising 300,000 troops and 3,200 tanks. As well, the Soviets suffered 180,000 troops killed and 170,000 wounded. German infantry units again were delayed in closing the gap with the panzer spearheads, which allowed large

numbers of Soviet troops to escape to the east.

June 26, 2020

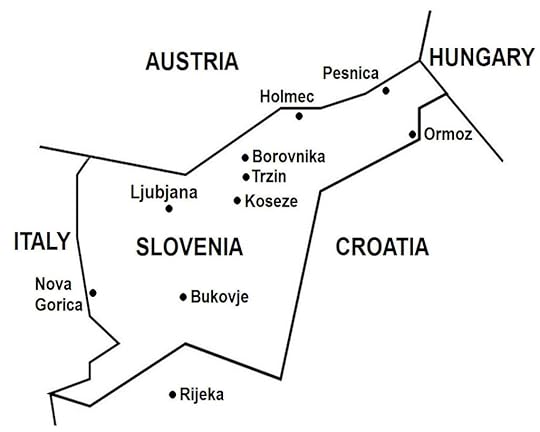

June 26, 1991 – Ten-Day War: The Yugoslavian Army enters Slovenia

Slovenian War of Independence (Ten-Day War)

On June 26, 1991, a Yugoslavian Army unit based in Rijeka, Croatia entered Slovenia to secure the Slovenian border with Italy. The soldiers were stopped at the Slovenian-Croatian border by Slovenian local residents who massed on the roads with barricades. The next day, the Yugoslav Army mobilized its units in Slovenia and Croatia in order to capture Ljubljana airport and Slovenia’s border crossings. Fighting between Yugoslav forces and Slovenian fighters broke out in Brnik, Trzin, Pesnica, Ormoz, and Koseze. While the Yugoslavs succeeded in taking Ljubljana airport and most border crossings, they found themselves vulnerable to attack and lacking logistical support. In particular, Yugoslav tank units guarding the border crossings had no supporting infantry troops.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina

(Excerpts taken from Slovenian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

The Slovenian War of Independence was the first in a series of wars during the period of the breakup of Yugoslavia, when Yugoslav constituent republics seceded and became independent countries.

Geographically, Slovenia was the most westerly located republic of Yugoslavia, and had through the centuries, assimilated many Western European influences from neighboring Italy and Austria into its Slavic

culture. And unlike the other Yugoslav

republics, Slovenia was nearly ethnically homogeneous, with Slovenes comprising 90% of the population.

As communist ideology tottered in the Soviet Union and Central and Eastern Europe during the second half of the 1980s, Yugoslavia’s apparent Slavic unity began to fragment as nationalistic and democratic ideas

seeped into its many ethnic groups. Economic factors also played into the independence aspirations in Slovenia and Croatia, the two most prosperous Yugoslav republics that contributed a fairly large share to the national

economy and also subsidized the less affluent regions of the country. In the late 1980s, the constituent assemblies of the Yugoslav republics called on the national government to decentralize and allow greater regional autonomy.

In September 1989, Slovenia’s regional government took the radical step of abolishing communism and adopting democracy as its official ideology. Then in January 1990, delegates of Slovenia and Croatia walked out of an assembly of Yugoslav communists over a disagreement with Serbian representatives regarding the future direction of the national

government. From this moment on, Yugoslav unity was shattered and the end of Yugoslavia became imminent. A pro-independence coalition government was established in Slovenia following democratic, multi-party elections in March 1990. Then in a general referendum held nine months later, 88% of Slovenes voted for independence. On June 25, 1991, Slovenia (together with Croatia) declared independence.

Because of the high probability that the Yugoslav Army would oppose the secession, the Slovenian government prepared contingency plans many months before declaring independence. For instance, Slovenia

formed a small regular army from its police and local defense units. Weapons and ammunitions stockpiles in Slovenia were seized; these were augmented with arms purchases from foreign sources.

Nevertheless, at the start of the war, Slovenia’s war arsenal consisted mainly of infantry weapons, bolstered somewhat with a small number of portable anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns. Slovenia had no artillery pieces,

battle tanks, or warplanes. And because the Yugoslav Army, the fourth largest in Europe,

would be overwhelming in battle, the Slovenians worked out in great detail a

strategy for guerilla action.

When Slovenia declared independence on June 25, this was one day earlier than its previous announced date of June 26. This was done to mislead the Yugoslav Army, which was prepared to attack on June 26.

Immediately after declaring independence, Slovenian forces took control of the airport near Ljubljana, Slovenia’s capital, and the border crossings with Austria, Hungary, Italy,

and Croatia. No opposition was encountered in these operations because the personnel manning these stations were Slovenes, who in

fact, promptly joined the ranks of the Slovenian Army.

Meanwhile, in Belgrade (in Serbia), the Yugoslav Armed Forces high command ordered limited military action in Slovenia in the belief

that small-scale intervention would encounter little or no resistance. And since the Yugoslav Army did not commit significant forces in Slovenia, the resulting Slovenian War of Independence was brief (lasting only ten days, therefore its more common name, “The Ten-Day War”), and consisted of skirmishes and small-scale battles.

June 25, 2020

June 25, 1950 – Korean War: North Korea invades South Korea

Some key sites during the Korean War

On June 25, 1950, North Korea launched a full-scale invasion of South Korea. The invading force, which consisted of 90,000 troops and supported by armored and artillery units, crossed the 38th parallel from east to west of the line. South Korean border fortifications south of the line were easily overcome. The defending forces, lacking heavy artillery and powerful anti-tank weapons, surrendered or defected en masse, or fled south. On June 28, 1950, Seoul fell, with President Syngman Rhee and his government having vacated the capital in advance of the North Korean offensive. To forestall the enemy advance, the South Korean military destroyed the main bridge south of Seoul across the Han River, causing the deaths of hundreds of civilians who were crossing the bridge at the time. Thousands of South Korean troops also were unable to leave the city and were captured by the North Koreans. By the third day of the invasion, South Korea was verging on complete collapse.

(Excerpts taken Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background

During World War II, the Allied Powers met many times to decide the disposition of Japanese territorial holdings after the Allies had achieved victory. With regards to Korea, at the Cairo Conference held in November 1943, the United States, Britain, and Nationalist China agreed that “in due course, Korea shall become free and independent”. Then at the Yalta Conference of February 1945, the Soviet Union promised to enter the war in the Asia-Pacific in two or three months after the European theater of World War II ended.

With the Soviet Army invading northern Korea on August 9, 1945, the United States became concerned that the Soviet Union might well occupy the whole Korean Peninsula. The U.S. government, acting on a hastily prepared U.S. military plan to divide Korea at the 38th parallel, presented the proposal to the Soviet government, which the latter accepted.

The Soviet Army continued moving south and stopped at the 38th parallel on August 16, 1945. U.S. forces soon arrived in southern Korea and advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8, 1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S. and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in their respective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commands established military rule in their occupation zones.

As both the U.S. and Soviet governments wanted to reunify Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December 1945, the Allied Powers agreed to form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China)

five-year trusteeship over Korea. During the five-year period, a U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission would work out the process

of forming a Korean government. But after a series of meetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve anything. In September 1947, the U.S. government referred the Korean question to the United Nations (UN). The reasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint

Commission’s failure to agree to a mutually acceptable Korean government are three-fold and to some extent all interrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed U.S.-Soviet trusteeship; the struggle for power among the various ideology-based political factions; and most important, the emerging

Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Historically, Korea for many centuries had been a politically and ethnically integrated state, although its independence often was interrupted by the invasions by its

powerful neighbors, China and Japan. Because of this protracted independence, in the immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, and viewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run their own affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’s political climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, from right-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashed with each other for political power. As a result of Japan’s

annexation of Korea in 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were the

unrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and a communist-allied anti-Japanese partisan militia led by Kim Il-sung.

Both men would play major roles in the Korean War. At the same time, tens of thousands of

Koreans took part in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese Civil War, joining and fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces, or for Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japanese resistance movement, which operated mainly out of Manchuria, was divided along ideological lines. Some groups advocated Western-style capitalist democracy, while others espoused Soviet communism. However, all were strongly anti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria, China, and Korea.

On their arrival in the southern Korean zone in September 1948, U.S. forces imposed direct rule through the United States Army Military Government In Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members of the Korean Communist Party in Seoul (the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeated Japanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Korean

peninsula. Then two days before U.S. forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee” proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under the auspices of a U.S. military agent, Syngman Rhee, the former

president of the “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” arrived in Seoul. The USAMGIK refused to recognize the communist Korean People’s Republic, as well as the pro-West “Provisional Government”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form a political coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S. sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. However, this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wing and right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S. authorities’ breaking up the communists’ “people’s committees” violence broke out in the southern zone during the last months of 1946. Called the Autumn Uprising, the unrest was carried out by left-aligned workers, farmers,

and students, leading to many deaths through killings, violent confrontations, strikes, etc. Although in many cases, the violence resulted from non-political motives (such as targeting Japanese collaborators or settling old scores), American authorities believed that the unrest was part of a communist plot. They therefore declared martial law in the southern zone. Following the U.S. military’s crackdown on

leftist activities, the communist militants went into hiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would play a role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, Soviet commanders initially worked to form a local administration under a coalition of nationalists,

Marxists, and even Christian politicians. But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who also was a Soviet Red Army officer, quickly became favored by Soviet

authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’s Committee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by Kim Il-sung who soon consolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christian leaders), and nationalized industries, and launched centrally

planned economic and reconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model

emphasizing heavy industry.

By 1947, the Cold War had begun: the Soviet Union tightened its hold on the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United States announced a new foreign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed at stopping the

spread of communism. The United States also implemented the Marshall Plan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which was condemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed at

dividing Europe. As a result, Europe became divided into the capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting these developments, in Korea

by mid-1945, the United States became resigned to the likelihood that the temporary military partition of the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel would become a permanent division along ideological grounds. In September 1947, with U.S. Congress rejecting a proposed aid package to Korea, the U.S.

government turned over the Korean issue to the UN. In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’s sovereignty and called for elections throughout the Korean peninsula, which was

to be overseen by a newly formed body, the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Soviet government rejected the UNGA resolution, stating that the UN had no jurisdiction over the Korean issue, and prevented UNTCOK representatives from entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were held

only in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experienced widespread

violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, a legislative body. Two months later (in July 1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitution which established a

presidential form of government. Syngman

Rhee, whose party won the most number of legislative seats, was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southerners proclaimed the birth of the Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as South Korea), ostensibly with the state’s sovereignty covering the whole Korean

Peninsula.

A consequence of the South Korean elections was the displacement of the political moderates, because of their opposition to both

the elections and the division of Korea. By contrast, the hard-line anti-communist Syngman Rhee was willing to allow the (temporary) partition of the peninsula. Subsequently, the United States moved to support the Rhee regime, turning its back on the political moderates whom USAMGIK had backed initially.

Meanwhile in the Soviet-controlled northern zone, on August 25, 1948, parliamentary elections were held to the Supreme National Assembly. Two weeks later (on September 9, 1948), the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as North Korea) was proclaimed, with Kim Il-Sung as (its first) Prime

Minister. As with South Korea, North Korea declared its sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula

The formation of two opposing rival states in Korea, each determined to be the sole authority, now set the stage for the coming

war. In December 1948, acting on a report by UNTCOK, the UN declared that the Republic

of Korea (South Korea) was the legitimate Korean polity, a decision that was rejected by both the Soviet Union and North Korea. Also in December 1948, the Soviet Union

withdrew its forces from North Korea. In June 1949, the United States withdrew its forces from South Korea. However, Soviet and American military advisors remained, in the North and South, respectively.

In March 1949, on a visit to Moscow,

Kim Il-sung asked Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, for military assistance for a North Korean planned invasion of South Korea. Kim Il-sung explained that an invasion would be successful, since most South Koreans opposed the Rhee regime, and that the communist insurgency in the south had sufficiently weakened the South Korean military. Stalin did not give his consent, as the Soviet government currently was pressed by other Cold War events in Europe.

However, by early 1950, the Cold War situation had been altered dramatically. In September 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, ending the United States’ monopoly on nuclear weapons. In October 1949, Chinese communists, led by Mao Zedong, defeated the West-aligned Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek in the Chinese Civil War, and proclaimed the People’s Republic of China, a socialist state. Then in 1950, Vietnamese communists (called Viet Minh) turned the First Indochina War from an anti-colonial war against France into a Cold War conflict involving the Soviet Union, China,

and the United States. In February 1950, the Soviet Union and China signed the Sino-Soviet Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance Treaty, where the Soviet government would provide military and financial aid to China.

Furthermore, the Soviet government, long wanting to gauge American strategic designs in Asia, was encouraged by two recent developments: First, the U.S. government did not intervene in the Chinese Civil War; and

second, in January 1949, the United States announced that South Korea was not part of the U.S. “defensive perimeter” in Asia, and U.S. Congress rejected an aid package to South Korea. To Stalin, the United States was resigned to the whole northeast Asian mainland falling to communism.

In April 1950, the Soviet Union approved North Korea’s plan to invade South Korea, but subject to two crucial conditions: Soviet forces

would not be involved in the fighting, and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA, i.e. the Chinese armed forces) must agree to intervene in the war if necessary. In May 1950, in a meeting between Kim Il-sung and Mao Zedong, the Chinese leader expressed concern that the United States might intervene if the North Koreans attacked South Korea. In the end, Mao agreed to send Chinese forces if North Korea was invaded. North Korea then hastened its invasion plan.

The North Korean armed forces (officially: the Korean People’s Army), having been organized into its present form concurrent with the rise of Kim Il-sung, had grown in strength with large Soviet support. And in 1949-1950, with Kim Il-sung emphasizing

a massive military buildup, by the eve of the invasion, North Korean forces boasted some 150,000–200,000 soldiers, 280 tanks, 200 artillery pieces, and 200 planes.

By contrast, the South Korean military (officially: Republic of Korea Armed Forces), which consisted largely of police units, was unprepared for war. The United States, not wanting a Korean war, held back from delivering weapons to South Korea,

particularly since President Rhee had declared his intention to invade North Korea in order to reunify the peninsula. By the time of the North Korean invasion, South Korean weapons, which the United States had limited to defensive strength, proved grossly inadequate. South Korea had 100,000 soldiers

(of whom only 65,000 were combat troops); it also had no tanks and possessed only small-caliber artillery pieces and an assortment of liaison and trainer aircraft.

North Korea had envisioned its invasion as a concentration of forces along the Ongjin Peninsula. North Korean forces would make a swift assault on Seoul to surround and destroy the South Korean forces there. Rhee’s government then would collapse, leading to the fall of South Korea. Then on June 21, 1950, four days before the scheduled invasion, Kim Il-sung believed that South Korea had become aware of the invasion plan and had fortified its defenses. He revised his plan for an offensive all across the 38th parallel. In the months preceding the war, numerous border skirmishes had begun breaking out between

the two sides.

June 24, 2020

June 24, 1954 – First Indochina War: French troops are ambushed by the Viet Minh at Mang Yang Pass

On June 24, 1954, a French force called Mobile Group 100 (aka G.M. 100) comprising 3,500 troops with heavy equipment and vehicles, was ambushed by the Viet Minh at Vietnam’s Mang Yang region, suffering 500 killed, 600 wounded, and 800 captured. G.M. 100 had just abandoned its remote base in the Central Highlands in the wake of the

disastrous Battle of Dien Bien Phu and was traveling from An Khe for Pleiku when the ambush took place. The five-day battle (June 24-29, 1954) was the last in the First Indochina War. On July 20, 1954, the Geneva Agreement was signed that imposed a general ceasefire, and on August 1, an armistice was signed that partitioned Vietnam at the 17th Parallel.

Aftermath of the First Indochina War

By the time of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, France knew that it could not win the war, and turned its attention on trying to work toward a political settlement and an honorable withdrawal from Indochina. By February 1954, opinion polls at home showed that only 8% of the French population supported the war. However, the Dien Bien Phu debacle dashed French hopes of negotiating under favorable withdrawal terms. On May 8, 1954, one day after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, representatives from the major powers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochina states: Cambodia,

Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and State of Vietnam, met at Geneva (the Geneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina. The Conference also was envisioned to resolve the crisis in the Korean Peninsula in the aftermath of the Korean War (separate article), where deliberations ended on June 15, 1954 without any settlements made.

On the Indochina issue, on July 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by the parties. The ceasefire was agreed to by France and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17th parallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional military

demarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The French and their allies in the northern zone departed and moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh in

the southern zone departed and moved to the northern zone (although some southern Viet Minh remained in the south on instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 days where Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on either side of the line. About one million

northerners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upper classes consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communist politicians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone, this mass exodus was prompted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and State of Vietnam in a massive propaganda campaign, as well as the peoples’ fears of repression under a communist regime.

In August 1954, planes of the French Air Force and hundreds of ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy (the latter under Operation Passage to Freedom) carried out the movement of Vietnamese civilians from north to south. Some 100,000 southerners, mostly

Viet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, moved to the northern zone. A peacekeeping force, called the International Control Commission and comprising contingents from India, Canada, and Poland,

was tasked with enforcing the ceasefire agreement. Separate ceasefire agreements also were signed for Laos and Cambodia.

Another agreement, titled the “Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring Peace in Indo-China, July 21, 1954”, called for Vietnamese general elections to be held in July 1956, and the

reunification of Vietnam. France DRV, the Soviet Union, China, and Britain signed this

Declaration. Both the State of Vietnam and the United States did not sign, the former outright rejecting the Declaration, and the latter taking a hands-off stance, but promising not to oppose or jeopardize the Declaration.

By the time of the Geneva Conference, the Viet Minh controlled a majority of Vietnam’s

territory and appeared ready to deal a final defeat on the demoralized French forces. The Viet Minh’s agreeing to apparently less favorable terms (relative to its commanding battlefield position) was brought about by the following factors: First, despite Dien Bien Phu, French forces in Indochina were far from being defeated, and still held an overwhelming numerical and firepower advantage over the Viet Minh; Second, the Soviet Union and China cautioned the Viet Minh that a continuation of the war might prompt an escalation of American military involvement in support of the French; and Third, French Prime Minister Pierre Mendes-France had vowed to achieve a ceasefire within thirty days or resign. The Soviet Union and China, fearing the collapse of the Mendes-France regime and its replacement by a right-wing government that would continue the war, pressed Ho to tone down Viet Minh insistence of a unified Vietnam

under the DRV, and agree to a compromise.

The planned July 1956 reunification election failed to materialize because the parties could not agree on how it was to be

implemented. The Viet Minh proposed

forming “local commissions” to administer the elections, while the United States, seconded by the State of Vietnam, wanted the elections to be held under United Nations (UN) oversight. The U.S. government’s greatest fear was a communist victory at the polls; U.S. President Eisenhower believed that “possibly 80%” of all Vietnamese would vote for Ho if

elections were held. The State of Vietnam

also opposed holding the reunification elections, stating that as it had not signed the Geneva Accords, it was not bound to participate in the reunification elections; it also declared that under the repressive conditions in the north under communist DRV, free elections could not be held there. As a result, reunification elections were not held, and Vietnam remained divided.

In the aftermath, both the DRV in the north (later commonly known as North Vietnam) and the State of Vietnam in the south (later as the Republic of Vietnam, more commonly known as South Vietnam) became de facto separate countries, both Cold War client states, with North Vietnam backed by

the Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, and South Vietnam supported by the United States and other Western democracies.

In April 1956, France pulled out its last troops from Vietnam; some two years earlier (June 1954), it had granted full independence to the State of Vietnam. The year 1955 saw the political consolidation and firming of Cold War alliances for both North Vietnam and South Vietnam. In the north, Ho Chi Minh’s regime launched repressive land reform and rent reduction programs, where many tens of

thousands of landowners and property managers were executed, or imprisoned in

labor camps. With the Soviet Union and China sending more weapons and advisors, North Vietnam firmly fell within the communist sphere of influence.

In South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, whom Bao Dai appointed as Prime Minister in June 1954, also eliminated all political dissent starting in 1955, particularly the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen in Saigon, and the

religious sects Hoa Hao and Cao Dai in the Mekong Delta, all of which maintained powerful armed groups. In April-May 1955, sections of central Saigon were destroyed in street battles between government forces and the Binh Xuyen militia.

Then in October 1955, in a referendum held to determine the State of Vietnam’s political future, voters overwhelmingly supported establishing a republic as campaigned by Diem, and rejected the restoration of the monarchy as desired by Bao Dai. Widespread irregularities marred the referendum, with an implausible 98% of voters favoring Diem’s proposal. On October 23, 1955, Diem proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam (later commonly known as South Vietnam), with himself as its first president. Its

predecessor, the State of Vietnam was dissolved, and Bao Dao fell from power.

In early 1956, Diem launched military offensives on the Viet Minh and its supporters in the South Vietnamese countryside, leading to thousands being executed or imprisoned.

Early on, militarily weak South Vietnam was promised armed and financial support by the United States, which hoped to prop up the regime of Prime Minister (later President) Diem, a devout Catholic and staunch anti-communist, as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia.

In January 1955, the first shipments of American weapons arrived, followed shortly by U.S. military advisors, who were tasked to provide training to the South Vietnamese

Army. The U.S. government also endeavored to shore up the public image of the somewhat unknown Diem as a viable alternative to the immensely popular Ho Chi Minh. However, the Diem regime was tainted by corruption and nepotism, and Diem himself ruled with autocratic powers, and implemented policies that favored the wealthy landowning class and Catholics at the expense of the lower peasant classes and Buddhists (the latter comprised 70% of the population).

By 1957, because of southern discontent with Diem’s policies, a communist-influenced civilian uprising had grown in South Vietnam, with many acts of terrorism, including bombings and assassinations, taking place. Then in 1959, North Vietnam, frustrated at the failure of the reunification elections from taking place, and in response to the growing insurgency in the south, announced that it was resuming the armed struggle (now against South Vietnam and the United States) in order to liberate the south and reunify Vietnam. The stage was set for the cataclysmic Second Indochina War, more popularly known as the Vietnam War. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5: Twenty Wars in Asia.)

June 23, 2020

June 23, 1919 – Estonian War of Independence: Estonian forces recapture Cēsis from the Baltische Landeswehr and German Freikorps

On June 23, 1919, The Estonian Third Division, aided by Latvian forces, wrested control of Cēsis from the retreating Baltische Landeswehr and German forces. The Estonians and Latvians then continued in pursuit in the direction of the Latvian capital Riga.

The Estonian War of Independence (November 1918-February 1920) broke out at the end of World War I when the newly declared Estonian state came into armed conflict with the Soviet Red Army that invaded to re-establish Russian control over the territory. With the support of Latvia (which was also concurrently engaged in its own independence war, as well as Britain and other Western nations), the fledging Estonian Army also battled against the Baltische Landeswehr (militias of the Baltic German nobility) and the Freikorps (German Army volunteers/mercenaries).

Background

The two revolutions in Russia in 1917 as well as ongoing events in World War I catalyzed ethnic minorities across the Russia Empire, resulting in the various regional nationalist movements pushing forward their objective of seceding from Russia and forming new independent nation-states. In the western and northern regions of the empire, the subject territories of Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland moved toward independence.

Key battle sites during the Estonian War of Independence.

Key battle sites during the Estonian War of Independence.On March 30, 1917, one month after the first (February 1917) revolution, Russia’s

Provisional Government granted political autonomy to Estonia after merging the Governorate (province) of Estonia and the ethnic Estonian northern portion of the Governorate of Livonia into the political and

administrative entity known as the “Autonomous Governorate of Estonia”. An interim body, the Estonian Provincial

Assembly (Estonian: Maapäev), was elected with the task of administering the new governorate. Furthermore, the Bolsheviks, on coming to power through the October Revolution, issued the “Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia” (on November 15, 1917), which granted all non-Russian peoples of the former Russian Empire the right to secede from Russia and establish their own separate states. Eventually, the Bolsheviks would renege on this edict and suppress secession from the Russian state (now known as Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, or RSFSR).

The Provisional Assembly of the Estonian Governorate, determined to implement a democratic form of government, declared itself as the supreme authority in Estonia, which effectively was an act of secession. However, on November 5, 1917, local Estonian Bolsheviks led by Jaan Anvelt seized power in a coup in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, forcing the Estonian nationalists to disperse and operate

clandestinely. Meanwhile in Soviet Russia, the Bolsheviks, whose revolution had succeeded partly on their promises to a war-weary citizenry and military to disengage from World War I, declared its pacifist intentions to the Central Powers. A ceasefire agreement was signed on December 15, 1917 and peace talks

began a few days later in Brest-Litovsk (present-day Brest, in Belarus).

The Provisional Assembly of the Estonian Governorate, determined to implement a democratic form of government, declared itself as the supreme authority in Estonia, which effectively was an act of secession. However, on November 5, 1917, local Estonian Bolsheviks led by Jaan Anvelt seized power in a coup in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, forcing the Estonian nationalists to disperse and operate

clandestinely. Meanwhile in Soviet Russia, the Bolsheviks, whose revolution had succeeded partly on their promises to a war-weary citizenry and military to disengage from World War I, declared its pacifist intentions to the Central Powers. A ceasefire agreement was signed on December 15, 1917 and peace talks

began a few days later in Brest-Litovsk (present-day Brest, in Belarus).

However, the Central Powers imposed territorial demands that the Russian government deemed excessive. On February 17, 1918, the Central Powers repudiated the ceasefire agreement, and the following day, Germany and Austria-Hungary restarted hostilities against Russia, launching a massive offensive with one million troops in 53 divisions along three fronts that swept through western Russia and captured Ukraine Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. German forces also entered Finland, aiding the non-socialist

paramilitary group known as the “White Guards” in defeating the socialist militia known as “Red Guards” in the Finnish Civil War. Eleven days into the offensive, the northern

front of the German advance was some 85 miles from the Russian capital of Petrograd (on March 12, 1918, the Russian government transferred its capital to Moscow).

On February 23, 1918, or five days into the offensive, peace talks were restarted at Brest-Litovsk, with the Central Powers demanding from Russia even greater territorial and military concessions than in the December

1917 negotiations. After heated debates

among members of the Council of People’s Commissars (the highest Russian

governmental body) who were undecided whether to continue or end the war, at

the urging of its Chairman, Vladimir Lenin, the Russian government acquiesced to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. On March 3, 1918, Russian and Central Powers representatives signed the treaty, whose major stipulations included the following: peace was restored between Russia

and the Central Powers; Russia relinquished possession of Finland (which was engaged in a civil war), Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic territories of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – Germany and Austria-Hungary were to determine the future of these territories; and Russia also agreed on some territorial

concessions to the Ottoman Empire.

In the midst of the German offensive, on February 24, 1918, Russian forces withdrew from Estonia and the local Estonian Bolshevik government collapsed. That same day, the Estonian Provincial Assembly emerged from hiding and reconvened; through its newly formed executive body, the Salvation Committee, it declared Estonia’s independence in Tallinn and then formed a provisional government. However, the next day, February 24, German forces entered Tallinn, bringing Estonia under German military occupation, and forcing Estonia’s provisional government to

return underground. Estonia’s one day-old status was an independent state thus ended.

German forces occupied Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland,

establishing semi-autonomous governments in these territories that were subordinate to the authority of the German monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II. The German occupation allowed the realization of the Germanic vision of “Mitteleuropa”, an expansionist ambition that sought unification of Germanic and non-Germanic peoples of Central Europe into a greatly enlarged and powerful German Empire. In support of Mitteleuropa, in the Baltic region, the Baltic German nobility proposed to set up the United Baltic Duchy,

a semi-autonomous political entity consisting of (present-day) Estonia and Latvia that would be voluntarily integrated into the German Empire. The proposal was not implemented, but German military authorities set up local

civil governments under the authority of the Baltic German nobility or ethnic Germans.

Although the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 ended Russia’s participation in World War I, the war was still ongoing in other fronts – most notably on the Western Front, where for four years, German forces were bogged down in inconclusive warfare against the British, French and other Allied Armies. After transferring substantial numbers of now freed troops from the Russian front to the Western Front, in March 1918, Germany launched the Spring Offensive, a major offensive into France and Belgium in an effort to bring the war to an end. After four months of fighting, by July 1918, despite achieving some territorial gains, the German offensive had ground to a halt.

The Allied Powers then counterattacked with newly developed battle tactics and weapons and gradually pushed back the now spent and demoralized German Army all across the line into German territory. The entry of the United States into the war on the Allied side was decisive, as increasing numbers of arriving American troops with the backing of the U.S. weapons-producing industrial power contrasted sharply with the greatly depleted

war resources of both the Entente and Central Powers. The imminent collapse of the German Army was greatly exacerbated by the outbreak of political and social unrest at the home front (the German Revolution of 1918-1919), leading to the sudden end of the German monarchy with the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II on November 9, 1918 and the establishment of an interim government (under moderate socialist Friedrich Ebert), which quickly signed an armistice with the Allied Powers on November 11, 1918 that ended the combat phase of World War I.

As the armistice agreement required that Germany demobilize the bulk of its armed forces as well as withdraw the same to the confines of the German borders within 30 days, the German government ordered its forces to abandon the occupied territories that had been won in the Eastern Front. Consequently, in Estonia, German authorities turned over governmental powers to the Estonian provisional government; the latter

restarted organizing a national armed forces (which had begun in April 1917 but was aborted by the German invasion), now urgently needed because of the buildup of Soviet forces at the Estonian border.

After Germany’s capitulation in November 1918, Russia repudiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and made plans to seize the European

territories it previously had lost to the Central Powers. An even far more reaching objective was for the Bolshevik government to spread the communist revolution to Europe, first by

linking up with German communists who were at the forefront of the unrest that currently was gripping Germany. Russian military planners intended the offensive to merely follow in the heels of the German withdrawal from Eastern Europe (i.e. to not directly engage the Germans in combat) and then seize as much territory before the various ethnic

nationalist groups in these territories could establish and consolidate a civilian government.

Starting on November 28, 1918, in the action known as the Soviet westward offensive of 1918-1919, Soviet forces consisting of hundreds of thousands of troops advanced in a multi-pronged offensive toward the Baltic region, Belarus, Poland, and Ukraine (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4).

June 22, 2020

June 22, 1941 – World War II: Germany invades the Soviet Union

Shortly after 3 AM on June 22, 1941, Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union, with thousands of artillery pieces opening a massive, coordinated bombardment of Soviet positions all along the 1,800-mile frontier. German special operations teams, positioned along the border, seized key road and water crossings, and assisted by local anti-Soviet militants, set about disrupting and severing Red Army communication lines. At first light, hundreds of Luftwaffe bombers and fighters took to the sky, and attacked strategic targets, including airfields, armories, and military, communications, and supply centers. These air attacks were massively successful, and the Soviet air force lost 1,400 planes on the first day and 3,100 by the third day, against only 78 German planes downed. These German air successes came as a result of Luftwaffe air reconnaissance missions conducted over Soviet territory in the previous months. Stalin had ordered Soviet anti-aircraft crews not to fire on the German reconnaissance planes, so as not to provoke Hitler. Thus in one stroke, the Luftwaffe achieved complete air supremacy over the battlefield.

The German High Command placed the A-A Line, which extends from Arkhangelsk in the Arctic in the north to Astrakhan in the Caspian Sea in the south, as the furthest advance of Operation Barbarossa.

German land forces and their Axis partners, comprising the bulk of the invasion, crossed the borders from East Prussia in the north to the Carpathian Mountains in the south into the Soviet Union, with Army Group North aiming for its final objective, Leningrad,

Army Group Center for Moscow, and Army Group South for the Ukraine and Caucasus, with all three army groups taking the Soviet

border and forward defenses by surprise.

The Luftwaffe seizing control of the skies, the destruction of Soviet communications and forward military infrastructures, and Stalin’s order not to retaliate to German provocations (which produced chaos at the Soviet frontlines; the order would not be revoked until several hours after the German attack) allowed German and Axis forces to make rapid progress.

Precursor

Operation Barbarossa was delayed because Hitler intervened in the Balkans in support of

his beleaguered ally, Italian leader Benito Mussolini. In December 1940, the invasion plan was finalized as Operation Barbarossa, set for May 15, 1941. By spring 1941, Operation Barbarossa’s planned launch date of May 15, 1941 increasingly appeared difficult to achieve: an unusually rainy winter flooded rivers and had turned Russian roads into impassable quagmires; troop transport vehicles from France, as well as oil supplies, were delayed; and the Luftwaffe forward airfields in Poland were not yet completed. Then in April 1940, Hitler was forced to launch the invasions of Greece and Yugoslavia following his ally Benito Mussolini’s disastrous campaign against the Greek Army.

The plan overcame opposition from the

German High Command which doubted its economic benefits to Germany, that albeit the agricultural and mineral resources of Ukraine and petroleum wealth of the Caucasus, the Soviet Union as a whole would be an economic drain on Germany. The German High Command also wanted the capture of Moscow as the invasion’s foremost aim, which Hitler rejected, pointing out that although French leader Napoleon Bonaparte had captured Moscow in 1812, French forces were still driven back from Russia. What therefore prevailed were Hitler’s stated priorities for the operation, “Leningrad first, the Donbass [eastern Ukraine] second, Moscow third” – that is, Moscow was of “no great importance”, but that the Soviet Red Army must be destroyed in the regions west of Moscow, specifically to the west of the Dvina and Dnieper rivers. Hitler’s main aim in Russia was to achieve lebensraum and acquire that country’s vast territories

and enormous agricultural, mineral, and industrial resources that would finally end Germany’s chronic shortage of raw materials for its ever growing population, industry, and military.

Aftermath