Daniel Orr's Blog, page 90

July 31, 2020

July 31, 1941 – German forces capture Smolensk

On July 31, 1941, units of German Army Group Center led by two panzer groups entered the Russian city of Smolensk, located 400 km west of Moscow. The Germans met fierce Soviet resistance during the two-month battle, but with the city’s capture, German Army Group Center had advanced 500 km into Soviet territory within 18 days since the start of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941. At Smolensk, the Germans encircled and destroyed three Soviet armies (the 16th, 19th, and 20th), capturing 300,000 troops and 3,200 tanks. As well, the Soviets suffered 180,000 troops killed and 170,000 wounded. German infantry units again were delayed in closing the gap with their panzer spearheads, allowing large numbers of Soviet troops (from the 19th and 20th armies) to escape to the east.

German Army Group Center also suffered heavy losses in men and material in the drawn-out battle. Historians have conjectured that German Army Group Center’s two-month delay on its advance to Moscow was consequential to its eventual defeat at the Battle of Moscow in December 1941.

Operation Barbarossa

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Operation Barbarossa: Central Sector

On June 22, 1941, German Army Group Center (with 1.3 million troops, 2,600 tanks, and 7,800 artillery pieces), based in Poland, attacked into Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, where the uneven border arising from the 1939 partition of the country created salients whose weak flanks could be exploited by an invading force. German Army Group Center had the greatest concentration of tanks comprising two panzer groups, as Hitler anticipated that this sector’s campaign into Moscow would be strongly resisted by the Red Army. To exploit the Soviet salient at Bialystok, the two panzer groups crossed the frontier in a flanking maneuver, with the 2nd Panzer Group to the south and bypassing Brest, and 3rd Panzer Group to the north advancing for Vilnius, with both groups aiming for Minsk, 400 miles to the east. Meanwhile, German Army Group Center’s three field armies also advanced north and south of the Bialystok salient, forming another set of pincers.

On June 23, 1941, a Red Army counter-attack was stopped. The next day, another Soviet counter-offensive, led by an armored force of over 1,000 tanks, advanced for Grodno to break the looming encirclement, but met disaster caused as much by fierce German air attacks as by mechanical breakdowns of the tanks and shortage of fuel. Another Soviet attack with 200 tanks on June 25 also ended in failure.

On June 27, 1941, the German 2nd and 3rd Panzer Groups met up at Minsk, and the next day, German Army Group Center’s

second pincers closed shut east of Bialystok. The trapped Soviet forces at Bialystok,

Navahrudak, and Minsk continued to resist, while elimination of these pockets by the Wehrmacht was delayed by lack of adequate German motor transports to hasten the advance of infantry units. Full encirclement of

Soviet forces also was compromised as the German 2nd Panzer, which was led by

General Heinz Guderian (an advocate of armored blitzkrieg tactics), continued

advancing east in contravention of Hitler’s pause order, which left gaps in the cordon that allowed Soviet units to escape. In the end, in the Bialystok-Minsk battles, although the Germans captured 300,000 Soviet troops, as well as 3,000 tanks, and 1,500 artillery pieces, some 250,000 Red Army soldiers escaped.

An annoyed Hitler faulted the panzer commanders for achieving only a partial capture of the trapped Soviets; in turn, the German commanders blamed the slow advance of the supporting infantry units. But in the aftermath, the Soviet Western Front was destroyed, with two field armies obliterated and three others severely incapacitated.

German Army Group Center then continued east toward Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. The German advance was again spearheaded by panzers, with 2nd Panzer Group advancing in the south and 3rd Panzer Group in the north with the aim of meeting up and encircling Smolensk.

On Stalin’s orders, five Soviet armies from the strategic reserve were deployed in Smolensk,

reinforcing the Soviet 13th Army there in essentially reconstituting the Soviet Western Front. The Soviets formed a new defensive line around the city, and also took up positions along the old Stalin Line along the Dnieper and Dvina rivers.

On July 6, 1941, Soviet armored units, comprising 1,500 tanks, attacked toward Lepiel, but were repulsed and nearly wiped out by a German tank and anti-tank counter-attack. Then on July 11 and the following days, the Red Army launched more

counter-attacks, which all failed to stall the Germans. On July 13, German 2nd Panzer Group took Mogilev, trapping several Soviet armies. Two days later, the Germans entered Smolensk, leading to fierce house-to-house fighting in the city. German 3rd Panzer Group, advancing from the north, was stalled by swampy terrain that was exacerbated by the seasonal rains. But in late July 1941, it too

entered Smolensk, and the two panzer groups closed shut and trapped three Soviet armies

comprising 300,000 troops and 3,200 tanks.

As well, the Soviets suffered 180,000 troops killed and 170,000 wounded. German infantry units again were delayed in closing the gap with the panzer spearheads, which allowed large numbers of Soviet troops to escape to the east.

July 30, 2020

July 30, 1969 – U.S. President Richard Nixon makes a surprise visit to South Vietnam

On July 30, 1969, President Richard Nixon made an unscheduled visit to South Vietnam, spending five hours in the capital Saigon meeting with President Nguyen Van Thieu and also with U.S. military commanders. He also visited U.S. troops at Di Am, twelve miles north of Saigon. The trip was part of a broad itinerary, where he made stops in Guam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, India, Pakistan, Romania, and Britain.

A divided country: North and South Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

In South Vietnam, he stated that the war must allow the South Vietnamese to “choose their own way”, a reference to the ongoing “Vietnamization” process, where the U.S. military was gradually disengaging from the war, concurrent with building up the South Vietnamese military which would take over the fighting. “Vietnamization” had begun the previous year, near the end of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s tenure in office.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

In 1969, newly elected U.S. president, Richard Nixon, who took office in January of that year, continued with the previous government’s policy of American disengagement and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, while simultaneously expanding Vietnamization, with U.S. military advice and material support. He also was determined to achieve his election campaign promise of securing a peace settlement with North Vietnam under the Paris peace talks, ironically through the use of force, if North Vietnam refused to negotiate.

In February 1969, the Viet Cong again launched a large-scale Tet-like coordinated offensive across South Vietnam, attacking villages, towns, and cities, and American bases. Two weeks later, the Viet Cong launched another offensive. Because of these attacks, in March 1968, on President Nixon’s orders, U.S. planes, including B-52 bombers, attacked Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in

eastern Cambodia (along the Ho Chi Minh Trail). This bombing campaign, codenamed Operation Menu, lasted 14 months (until May 1970), and segued into Operation Freedom Deal (May 1970-August 1973), with the latter

targeting a wider insurgent-held territory in eastern Cambodia.

In the 1954 Geneva Accords, Cambodia had declared its neutrality in regional conflicts, a policy it maintained in the early years of the Vietnam War. However, by the early 1960s, Cambodia’s reigning monarch, Norodom Sihanouk, came under great pressure by the escalating war in Vietnam, and especially after 1963, when North Vietnamese forces occupied sections of eastern Cambodia as part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail system to South Vietnam. Then in the mid-1960s, Sihanouk signed security agreements with China and North Vietnam, where in exchange for receiving economic incentives, he acquiesced to the North Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia. He also allowed the use of the port of Sihanoukville (located in southern Cambodia) for shipments from communist countries for the Viet Cong/NLF through a newly opened land route across Cambodia. This new route, called the Sihanouk Trail (Figure 5) by the Western media, became a major alternative logistical system by North Vietnam during the period of intense American air operations over the Laotian side of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail and other key areas during the Vietnam War.

In July 1968, under strong local and regional pressures, Sihanouk re-opened diplomatic relations with the United States, and his government swung to being pro-West. However, in March 1970, he was overthrown in a coup, and a hard-line pro-U.S. government

under President Lon Nol abolished the monarchy and restructured the country as

the Khmer Republic. For Cambodia,

the spill-over of the Vietnam War into its territory would have disastrous consequences, as the fledging communist Khmer Rouge insurgents would soon obtain large North Vietnamese support that would plunge Cambodia into a full-scale civil war. For the United States (and South Vietnam), the pro-U.S. Lon Nol government served as a green light for American (and South Vietnamese) forces to conduct military operations in Cambodia.

The U.S. bombing operations on Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia forced North Vietnam to increase its military presence in other parts of Cambodia. The North Vietnamese Army seized control particularly of northeastern Cambodia, where its forces defeated and expelled the Cambodian Army. Then in response to the Cambodian government’s request for military assistance, starting in late April to early May 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces launched a major ground

offensive into eastern Cambodia. The main U.S. objective was to clear the region of the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong in order to allow the planned American disengagement from the Vietnam War to proceed smoothly and on schedule. The offensive also served as a gauge of the progress of Vietnamization, particularly the performance of the South Vietnamese Army in large-scale operations.

In the nearly three-month successful operation (known as the Cambodian Campaign) which lasted until July 1970, American and South Vietnamese forces, which at their peak numbered over 100,000 troops, uncovered several abandoned major Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases and dozens of underground storage bunkers containing huge quantities of materiel and supplies. In all, American and South Vietnamese troops

captured over 20,000 weapons, 6,000 tons of rice, 1,800 tons of ammunition, 29 tons of communications equipment, over 400 vehicles, and 55 tons of medical supplies. Some 10,000 Viet Cong/North Vietnamese were killed in the fighting, although the majority of their forces

(some 40,000) fled deeper into Cambodia. However, the campaign failed to achieve one

of its objectives: capturing the Viet Cong/NLF leadership COSVN (Central Office for South Vietnam). The Nixon administration also came under domestic political pressure: in December 1970, and U.S. Congress passed a law that prohibited U.S. ground forces from engaging in combat inside Cambodia and Laos.

Before the Cambodian Campaign began, President Nixon had announced in a nationwide broadcast that he had committed U.S. ground troops to the operation. Within days, large demonstrations of up to 100,000 to 150,000 protesters broke out in the United States, with the unrest again centered in universities and colleges. On May 4, 1970, at Kent State University, Ohio, National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of protesters, killing four people and wounding eight others. This incident sparked even wider, increasingly militant and violent protests across the country. Anti-war sentiment already was intense in the United States

following news reports in November 1969 of what became known as the My Lai Massacre, where U.S. troops on a search and destroy mission descended on My Lai and My Khe villages and killed between 347 and 504 civilians, including women and children.

American public outrage further was fueled when in June 1971, the New York Times began publishing the “Pentagon Papers” (officially titled: United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense), a highly classified study by the U.S. Department of Defense that was leaked to the press. The Pentagon Papers showed that successive past administrations, including those of Presidents Truman,

Eisenhower, and Kennedy, but especially of President Johnson, had many times misled the American people regarding U.S. involvement in Vietnam. President Nixon sought legal grounds to stop the document’s publication for national security reasons, but the U.S. Supreme Court subsequently decided in favor of the New York Times and publication

continued, and which was also later taken up by the Washington Post and other

newspapers.

July 29, 2020

July 29, 1921 – Adolf Hitler becomes leader of the Nazi Party

On July 29, 1921, Adolf Hitler became the leader of the far-right National Socialist German Workers’ Party, more commonly known in the West as the Nazi Party, which was the successor movement of the German Workers’ Party.

Hitler first participated in the German Workers’ Party in July 1919 not as a recruit but to infiltrate the newly formed organization. At that time, he was an intelligence agent of the German Army. However, he soon was won over by the movement’s ultra-nationalist, anti-Semitic, anti-capitalist, anti-Marxist ideas.

(Taken from Events Leading up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Hitler and the Nazis in Power

In October 1929, the severe economic crisis known as the Great Depression began in the United States, and then spread out and affected many countries around the world. Germany, whose economy was dependent on the United States for reparations payments and corporate investments, was badly hit, and millions of workers lost their jobs, many banks closed down, and industrial production and foreign trade dropped considerably.

The Weimar government weakened politically, as many Germans turned to radical ideologies, particularly Hitler’s ultra-right wing nationalist Nazi Party, as well as the German Communist Party. In the 1930 federal elections, the Nazi Party made spectacular gains and became a major political party with a platform of improving the economy, restoring political stability, and raising Germany’s

international standing by dealing with the “unjust” Versailles treaty. Then in two elections held in 1932, the Nazis became the dominant party in the Reichstag (German parliament), albeit without gaining a majority. Hitler long sought the post of German Chancellor, which was the head of government, but he was rebuffed by the elderly President Paul von Hindenburg , who distrusted Hitler. At this time, Hitler’s ambitions were not fully known, and following a political compromise by rival parties, in

January 1933, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor, with few

Nazis initially holding seats in the new Cabinet. The Chancellorship itself had little power, and the real authority was held by the President (the head of state).

On the night of February 27, 1933, fire broke out at the Reichstag, which led to the arrest and execution of a Dutch arsonist, a

communist, who was found inside the building. The next day, Hitler announced that the fire was the signal for German communists to launch a nationwide revolution. On February 28, 1933, the German parliament passed the “Reichstag Fire Decree” which repealed civil liberties, including the right of assembly and freedom of the press. Also rescinded was the writ of habeas corpus, allowing authorities to arrest any person without the need to press charges or a court order. In the next few weeks, the police and Nazi SA paramilitary carried out a suppression campaign against communists (and other political enemies) across Germany, executing communist leaders, jailing tens of thousands of their members, and effectively ending the German Communist Party. Then in March 1933, with the communists suppressed and other parties intimidated, Hitler forced the Reichstag to pass the Enabling Act, which allowed the government (i.e. Hitler) to enact laws, even those that violated the constitution, without the approval of parliament or the president. With nearly absolute power, the Nazis gained control of all aspects of the state. In July 1933, with the banning of political parties and coercion into closure of the others, the Nazi Party became the sole legal party, and Germany became de facto a one-party state.

At this time, Hitler grew increasingly alarmed at the military power of the SA, particularly distrusting the political ambitions of its leader, Ernst Rohm. On June 30-July

2, 1934, on Hitler’s orders, the loyalist Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel; English: Protection Squadron) and Gestapo (Secret Police) purged the SA, killing hundreds of its leaders including Rohm, and jailing thousands of its members,

violently bringing the SA organization (which had some three million members) to its knees. The purge benefited Hitler in two ways: First, he became the undisputed leader of the Nazi apparatus, and Second and equally important, his standing greatly increased with the upper

class, business and industrial elite, and German military; the latter, numbering only 100,000 troops because of the Versailles treaty restrictions, also felt threatened by the enormous size of the SA.

In early August 1934, with the death of President Hindenburg, Hitler gained absolute power, as his Cabinet passed a law that

abolished the presidency, and its powers were merged with those of the chancellor. Hitler thus became both German head of state and head of government, with the dual roles of Fuhrer (leader) and Chancellor. As head of

state, he also was Supreme Commander of the armed forces, making him absolute ruler and dictator of Germany.

In domestic matters, the Nazi government made great gains, improving the economy and industrial production, reducing unemployment,

embarking on ambitious infrastructure projects, and restoring political and social order. As a result, the Nazis became extremely popular, and party membership grew enormously. This success was brought about from sound policies as well as through threat and intimidation, e.g. labor unions and job

actions were suppressed.

Hitler also began to impose Nazi racial policies, which saw ethnic Germans as the “master race” comprising “super-humans” (Ubermensch), while certain races such as Slavs, Jews, and Roma (gypsies) were considered “sub-humans” (Untermenschen); also lumped with the latter were non-ethnic-based groups, i.e. communists, liberals, and other political enemies, homosexuals,

Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc.

Nazi lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism into Eastern Europe and Russia called for eliminating the Slavic and other populations there and replacing them with German farm settlers to help realize Hitler’s dream of a 1,000-year German Empire.

In Germany itself, starting in April 1933 until the passing of the Nuremberg Laws in

September 1935 and beyond, Nazi racial policy was directed against the local Jews, stripping them of civil rights, banning them from employment and education, revoking their citizenship, excluding them from political and social life, disallowing inter-marriages with Germans, and essentially declaring them

undesirables in Germany. As a result, tens of thousands of Jews left Germany. Hitler blamed the Jews (and communists) for

the civilian and workers’ unrest and revolution near the end of World War I, ostensibly that had led to Germany’s defeat, and for the many social and economic problems currently afflicting the nation. Following anti-Nazi boycotts in the United States, Britain, and other countries, Hitler retaliated with a call to boycott Jewish businesses in Germany, which degenerated into violent riots by SA mobs that attacked and killed, and jailed hundreds of Jews, looted and destroyed Jewish properties, and seized Jewish assets. The most notorious of these attacks occurred in November 1938 in “Kristallnacht” (Crystal Night), where in response to the assassination of a German diplomat by a Polish Jew in Paris, the Nazi SA and civilian mobs in Germany went on a violent rampage, killing hundreds of Jews,

jailing tens of thousands of others, and looting and destroying Jewish homes, schools, synagogues, hospitals, and other buildings. Some 1,000 synagogues were burned, and 7,000 businesses destroyed.

In foreign affairs, Hitler, like most Germans, denounced the Versailles treaty, and wanted it rescinded. In 1933, Hitler withdrew Germany

from the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva, and in October of that year, from the League of Nations, in both cases denouncing why Germany was not allowed to re-arm to the level of the other major powers.

In March 1935, Hitler announced that German military strength would be increased to 550,000 troops, military conscription would be introduced, and an air force built, which essentially meant repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles and the start of full-scale rearmament. In response, Britain, France, and Italy formed the Stresa Front meant to stop further German violations, but this alliance quickly broke down because the three parties disagreed on how to deal with Hitler.

Italy, after being denounced by the League of Nations and slapped with economic

sanctions after its invasion of Ethiopia,

switched sides to Germany. Mussolini and Hitler signed a series of agreements that soon led to a military alliance. Meanwhile, Britain

and France continued their indecisive foreign policies toward Germany. In March 1936, in a bold move, Hitler sent troops to the Rhineland, remilitarizing the region in another violation of the Versailles treaty, but met no hostile response from the other powers. Hitler justified this move as a defensive response to the recently concluded French-Soviet mutual assistance pact, which he accused the two

countries of encircling Germany, a statement that drew sympathy from some British politicians.

Nazi ideology called for unification of all Germanic peoples into a Greater German Reich. In this context, Hitler had long sought to annex Austria, whose indigenous population was German, into Germany. An annexation attempt in 1934 was foiled by Italian intervention, with Mussolini determined to go to war if Germany invaded Austria. But by 1938, German-Italian relations had warmed and were moving toward a military alliance. With Britain and France watching by, in March 1938, Hitler put political pressure on Austria, and with the threat of invasion, forced the Austrian government to resign, and cede power to the Austrian Nazi Party. Within days, the latter relinquished Austrian independence to Germany, and German troops occupied Austria. In a Nazi-controlled plebiscite held in April 1938, an improbable 99.7% of Austrians voted for “Anschluss” (political union) with Germany.

In late March 1938, while Germany was yet in the process of annexing Austria, another conflict, the “Sudetenland Crisis” occurred, where ethnic Germans, who formed the majority population in the Sudeten region of

Czechoslovakia, demanded autonomy and the right to join the Nazi Party. Hitler supported these demands, citing the Sudeten Germans’ right to self-determination. The Czechoslovak government refused, and in May 1938, mobilized for war. In response, Hitler secretly asked the German High Command to prepare for war, to be launched in October 1938. Britain and France, anxious to avoid war at all costs by not antagonizing Hitler (a policy called

appeasement), pressed Czechoslovakia

to yield, with the British even stating that the Sudeten Germans’ demand for autonomy was reasonable. In early September 1938, the Czechoslovak government agreed to the demands. Then when civilian unrest broke out in the Sudetenland which the Czechoslovakian police quelled, in mid-September 1938, a

furious Hitler demanded that the Sudetenland be ceded to Germany in order to stop the

supposed slaughter of Sudeten Germans.

Under great pressure from Britain and France, on September 21, 1938, the Czechoslovak government relented, and agreed to cede the Sudetenland. But the next day, Hitler made new demands, which Czechoslovakia rejected and again mobilized for war. In a frantic move to avert war, the Prime Ministers of Britain

and France, Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier, respectively, together with Mussolini, met with Hitler, and on September 29, 1938, the four men signed the Munich Pact, where the Sudetenland was formally ceded to Germany. Two days later, Czechoslovakia

accepted the fait accompli, knowing it would not be supported by Britain and France in a war with Germany. In succeeding months, Czechoslovakia disintegrated as a sovereign

state: the Slovak region separated, aligning with Germany as a puppet state; other regions were annexed by Hungary and Poland; and in March 1939, the rest of the Czech portion of the country was occupied by Germany.

Hitler then turned to Poland, and proposed to renew their ten-year non-aggression pact (signed in 1934) in exchange for revising their common border, specifically returning to Germany some territories that were ceded to Poland after World War I. The Polish government refused, causing Hitler to rescind the pact in April 1939. By then, Britain

and France had abandoned appeasement in favor of assertive diplomacy, and promised military support to Poland if Germany invaded. In the period May-August 1939, as war loomed, frantic efforts were made by Britain and France jointly, and by Germany, to win over to their side the last remaining undecided major European power, the Soviet Union. The Germans prevailed, and a non-aggression pact was signed with the Soviets on August 23, 1939, which prompted Hitler to

begin hostilities with Poland under the mistaken belief that Britain and France

would not react militarily.

July 28, 2020

July 28, 1915 – American forces land at Port-au-Prince, starting a 19-year occupation of Haiti

(Taken from United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915 – 1934 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

On July 28, 1915, Haitian President Vibrun Sam, an ally of the United States, was killed in a riot that broke out after he ordered the execution of his political enemies. Pandemonium broke out in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, where anti-American elements led by Rosalvo Bobo moved to take control of the government. Declaring the need to protect American citizens and American commercial interests in Haiti, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson acted swiftly, and U.S. Marines were landed in Port-au-Prince. After some fighting, the U.S. forces expelled the anti-American militia from the capital.

The island of Hispaniola consists of two separate nations: French and French-Creole speaking Haiti to the west and Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic to the east.

The American intervention began a 19-year occupation of Haiti, prompted by the U.S. government’s determination to bring about

stability in the Caribbean country and ensure that Haiti repaid the loan. Under U.S. pressure, a pro-American government, led by President Sudre Dartiguenave, was installed in August 1915, which held only limited authority. The

two countries signed a bilateral treaty, whereby Haiti practically became a U.S.

protectorate, as the Caribbean country’s political, judicial, military, and economic policies came under the authority of first, the U.S. occupation force, and later by the American High Commissioner’s Office, which was set up by the U.S. government. The United States took control of Haiti’s treasury, customs, banking, and other revenue-generating agencies, and persuaded the Haitian government to pass laws that made Haiti pay back its foreign loans, especially to those from American and French creditors.

History of Haiti

Haiti, a country that occupies one-third and the western section of Hispaniola Island in the Caribbean Sea, gained its independence in 1804 when black African plantation slaves rebelled and overthrew their French colonial masters, and then established their own government. Thereafter for the rest of the 1800s, Haiti experienced political instability and social unrest because of its weak governmental, security, and economic infrastructures, with successive governments being deposed as a result of coups, revolts, and civil wars.

Largely because of a massive foreign debt, particularly to France, Haiti constantly experienced economic difficulties. In the post-war agreement signed between Haiti

and France in 1824, France promised not to invade Haiti, and recognized Haiti’s independence. In return, Haiti promised to pay France a large indemnity, which became a heavy monetary load that crippled Haiti’s

economy.

By the early 1900s, German Haitians (ethnic Germans who had immigrated to Haiti) had established large businesses in Haiti,

gaining control of the local economy that once was dominated by the French. The Germans had succeeded because many of them had married with Haiti’s mulatto elite, allowing

them to join the ranks of local power and influence, as well as acquire the right to own Haitian land (which legally was forbidden to foreigners).

Background of U.S. Intervention in Haiti

Haiti’s political instability continued into the early twentieth century – seven governments changed hands violently between 1911 and 1915. The United States viewed the Haitian situation with great concern, as Haiti was located fairly close to the Panama Canal, on which the U.S. government had invested a large amount of money to complete and which provided not only a substantial economic benefit to the Americans but also served as a vital strategic and military asset.

U.S. foreign policy at this time was based on the Monroe Doctrine*, which was aimed

at deterring European involvement in the Western Hemisphere. In Haiti, the U.S. government looked with disfavor at the strong German and French diplomatic and economic

influences. But of particular concern for the United States in 1915 were the German Haitians, as World War I had broken out in Europe and Germany had taken the initiative early in the war. The United States believed

that Germany might intervene in Haiti’s

political instability in order to protect German commercial interests. The American concern was increased when German Haitians made such a request for intervention to the German government. For the United States, a German military presence in Haiti would threaten American interests in the Caribbean region, particularly with regard to the Panama Canal.

Historically, the U.S. response to Haiti’s

instability was to launch a direct military intervention: between 1876 and 1913, the American government sent troops to Haiti a total of 15 times during periods of unrest. In 1891, the United States had failed to persuade the Haitian government to allow the U.S.

military to construct a naval base in Haiti. Nevertheless, the U.S. Navy kept a permanent

watch of the waters off Haiti, which was part of American policy to maintain political and military control of the whole Central American and Caribbean regions.

In 1910, the United States loaned out a large amount of money to Haiti to help pay down the Caribbean country’s large foreign debt. The U.S. government, therefore, had its commitments, as well as its stakes, raised in Haiti. In 1914, Haiti rejected American attempts to impose more economic measures. Consequently, the United States withdrew $500 million of Haiti’s foreign reserves and transferred that amount to New York for safekeeping. The United States also gained control of Haiti’s National Bank.

July 27, 2020

July 27, 1953 – Korean War: An armistice is signed that ends fighting

On July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement, which ended fighting in the Korean War which had begun on June 25, 1950. South Korea, led by president Syngman Rhee, refused to sign but promised to observe the armistice agreement. President Rhee was determined to reunify Korea under his rule and wanted the UN Command to force an all-out war against China, even at the risk of provoking the Soviet Union into entering the conflict on the side of North Korea. As such, he strongly opposed the armistice negotiations and even demanded that UN troops withdraw from South Korea to allow only his forces to continue the war.

Meanwhile, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung had also desired Korean unification under his authority. But after armistice negotiations commenced, he was prevailed upon by his backers China and the Soviet Union to tone down his hard-line stance. He subsequently changed his motto of “drive the enemy into the sea” to “drive the enemy to the 38th parallel.”

North Korea and South Korea in East Asia.

North Korea and South Korea in East Asia.(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath of the Korean War

Meanwhile, armistice talks resumed, which culminated in an agreement on July 19, 1953. Eight days later, July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement, which ended the war. A ceasefire came into effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldiers killed, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; North Korean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which included Chairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying). Civilian casualties were 2 million for South Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Korean refugees who had moved to South Korea. Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forces conducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to be

supporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea, during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militias

executed some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupation

of South Korea, also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries”

(politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians who refused to join the North Korean Army.

Under the armistice agreement, the frontline at the time of the ceasefire became the armistice line, which extended from coast to coast some 40 miles north of the 38th parallel in the east, to 20 miles south of the

38th parallel in the west, or a net territorial loss of 1,500 square miles to North Korea. Three days after the agreement was signed, both sides withdrew to a distance of two kilometers from the ceasefire line, thus creating a four-kilometer demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the opposing forces.

The armistice agreement also stipulated the repatriation of POWs, a major point of contention during the talks, where both parties

compromised and agreed to the formation of an independent body, the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission (NNRC), to implement the exchange of prisoners. The NNRC, chaired by General K.S. Thimayya

from India, subsequently launched Operation Big Switch, where in August-December 1953, some 70,000 North Korean and 5,500 Chinese POWs, and 12,700 UN POWs (including 7,800 South Koreans, 3,600 Americans, and 900 British), were repatriated. Some 22,000

Chinese/North Korean POWs refused to be repatriated – the 14,000 Chinese prisoners who refused repatriation eventually moved to the Republic of China (Taiwan), where they were given civilian status. Much to the astonishment of U.S. and British authorities, 21 American and 1 British (together with 325 South Korean) POWs also refused to be

repatriated, and chose to move to China.

All POWs on both sides who refused to be repatriated were given 90 days to change their minds, as required under the armistice agreement.

The armistice line was conceived only as a separation of forces, and not as an international border between the two Korean states. The Korean Armistice Agreement called on the two rival Korean governments to negotiate a peaceful resolution to reunify the Korean Peninsula. In the international Geneva Conference held in April-July 1954, which aimed to achieve a political settlement to the recent war in Korea (as well as in Indochina, see First Indochina War, separate article), North Korea and South Korea, backed by their major power sponsors, each proposed a political settlement, but which was unacceptable to the other side. As a result, by the end of the Geneva Conference on June 15, 1953, no resolution was adopted, leaving the

Korean issue unresolved.

Since then, the Korean Peninsula has remained divided along the 1953 armistice line, with the 248-kilometer long DMZ, which was originally meant to be a military buffer zone, becoming the de facto border between North Korea and South Korea. No peace treaty was signed, with the armistice agreement being a ceasefire only. Thus, a state of war officially continues to exist between the two Koreas. Also as stipulated by the Korean Armistice Agreement, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) was established, comprising contingents from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland, tasked with ensuring that no new foreign military personnel and weapons are

brought into Korea.

Because of the constant state of high tension between the two Korean states, the DMZ has since remained heavily defended and is the most militarily fortified place on Earth.

Situated at the armistice line in Panmunjom is the Joint Security Area, a conference center where representatives from the two Koreas hold negotiations periodically. Since the end of the Korean War, there exists the constant threat of a new war, which is exacerbated

by the many incidents initiated by North Korea

against South Korea. Some of these incidents include: the hijacking by a North Korean agent of a South Korean commercial airliner in

December 1969; the North Korean abductions of South Korean civilians; the failed assassination attempt by North Korean commandos of South Korean President Park Chung-hee in January 1968; the sinking of a South Korean naval vessel, the ROKS Cheonon, in March 2010, which the South Korean government blamed was caused by a torpedo fired by a North Korean submarine (North Korea denied any involvement), and the discovery of a number of underground tunnels

along the DMZ which South Korea has said were built by North Korea to be used as an invasion route to the south.

Furthermore, in October 2006, North Korea announced that it had detonated its first nuclear bomb, and has since stated that it possesses nuclear weapons. With North Korea aggressively pursuing its nuclear weapons capability, as evidenced by a number of nuclear tests being carried out over the years, the peninsular crisis has threatened to expand to regional and even global dimensions.

Western observers also believe that North Korea has since been developing chemical and biological weapons.

July 26, 2020

July 26, 1953 – Fidel Castro leads an attack on the Moncada Barracks, sparking the Cuban Revolution

On July 26, 1953, Fidel Castro led over 160 armed followers, which included his brother Raul, in an attack on the army garrisons in Santiago de Cuba and Bayamo, both located at the southeast section of the island. The plan called for seizing weapons from the garrisons’ armories and then arming the local civilian population to incite a general uprising. The attack was foiled by the military, however, with the Castro brothers and many other rebels being captured, imprisoned, and subsequently charged for treason. Three months later, on October 16, the Castro brothers were handed down long prison terms, together with their followers who were given shorter prison sentences. The trials gained national attention, with Fidel Castro, who acted as his own defense attorney, gaining wide public recognition. While serving time in prison, Fidel renamed his organization the “26th of July Movement” or M-26-7 (Spanish: Movimiento 26 de Julio), in reference to the date of the failed attacks.

Fidel Castro was a student leader who previously had taken part in the aborted overthrow of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo and in the 1948 civil

disturbance (known as “Bogotazo”) in Bogota, Colombia before completing his law studies at

the University of Havana. He then run as an independent for Congress in the 1952 elections that were cancelled because of Batista’s coup. Castro was outraged and began making preparations to overthrow what he declared was the illegitimate Batista regime

that had seized power from a democratically elected government. Fidel organized an armed insurgent group, “The Movement”, whose aim was to overthrow President Batista. At its peak, “The Movement” would comprise 1,200

members in its civilian and military wings.

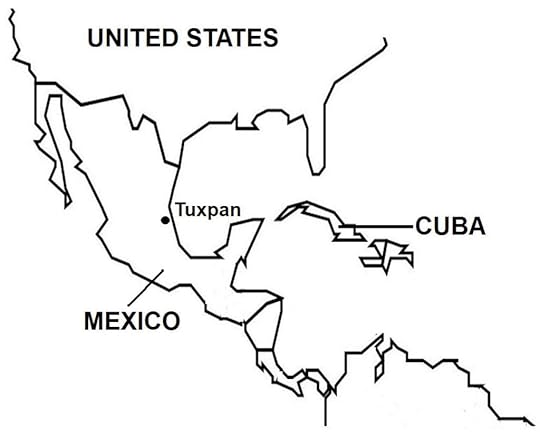

In November 1956, Fidel Castro and 81 other rebels set out from Tuxpan, Mexico aboard a decrepit yacht for their nearly 2,000 kilometer trip across the Caribbean Sea bound for south-eastern Cuba.

(Taken from Cuban Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Aftermath of the Cuban Revolution

In Havana, President Manuel Urrutia (who Castro had appointed as provisional president and Cuba’s new head of state), and especially Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and the M-26-7 fighters, took control of civilian and military institutions of the government. Similarly in Oriente Province, Fidel Castro established authority over the regional governmental and military functions. In the following days, other regional military units all across Cuba surrendered their jurisdictions to rebel forces that arrived. Then from Santiago de Cuba, Fidel Castro began a nearly week-long journey to Havana, stopping at every town and city to large crowds and giving speeches, interviews, and press conferences. On January 8, 1959, he arrived in Havana and declared himself the “Representative of the Rebel Armed Forces of the Presidency”, that is, he was effectively head of the Cuban Armed Forces under the government of President Urrutia and newly installed Prime Minister Jose Miro. Real power, however, remained with Castro.

In the next few months, the Castro regime consolidated power by executing or jailing hundreds of Batista supporters for “war crimes” and relegating to the sidelines the other rebel groups that had taken part in the

revolution. During the war, Fidel Castro had promised the return of democracy by instituting multi-party politics and holding free elections. Now however, he spurned these promises, declaring that the electoral process was socially regressive and benefited only the wealthy elite.

Castro denied being a communist, the most widely publicize declaration being during his personal visit to the United States in April 1959, or four months after he gained power.

Members of the Popular Socialist Party, or PSP (Cuban communists), however, soon began to dominate key government positions, and Cuba’s foreign policy moved toward establishing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries. (By 1961 when Castro had declared Cuba a communist state, his M-26-7 Movement had formed an alliance with the PSP, the 13th of March Movement – DR, and other leftist organizations; this coalition ultimately gave rise to the Cuban Communist

Party.)

President Urrutia, who was a political moderate and a non-communist, made known his concern about the socialist direction of the

government, which put him directly in Castro’s way. Consequently in July 1959, President Urrutia was forced to resign from office, as Prime Minister Miro had done earlier in

February. A Cuban communist took over as

the new president, subservient to the dictates of Fidel Castro. Castro had become the “Maximum Leader” (Spanish: Maximo Lider), or absolute dictator; he abolished Congress, ruled by decree, and suppressed all forms of opposition. Free speech was silenced, as were the print and broadcast media, which were placed under government control. In the villages, towns, and cities across Cuba, neighborhood watches called the “Committees for the Defense of the Revolution” were formed to monitor the activities of all residents within their jurisdictions and to weed out

dissidents, enemies, and “counter- revolutionaries”. In 1959, land reform was implemented in Cuba; private and corporate lands were seized, partitioned, and distributed to peasants and landless farmers.

On January 7, 1959, just a few days after the Cuban Revolution ended, the United States recognized the new Cuban government under President Urrutia. But as Castro later gained absolute power and his government gradually turned socialist, relations between the two countries deteriorated rapidly. By July 1959, just seven months later, U.S. president Dwight Eisenhower was planning Castro’s overthrow; subsequently in March 1960, he ordered the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to organize and train U.S.-based Cuban exiles for an invasion of Cuba.

In 1960, Castro entered into a trade agreement with the Soviet Union that included purchasing Russian oil. Then when U.S.

petroleum companies in Cuba refused to refine the imported Russian oil, a succession of measures and retaliatory counter-measures followed quickly. In July 1960, Cuba seized the American oil companies and nationalized them the next month. In October 1960, the United States imposed an economic embargo on Cuba and banned all imports (which constituted 90% of all Cuban exports) from Cuba. The restriction included sugar, which was Cuba’s biggest source of revenue. In January 1960, the United States ended all official diplomatic relations with Cuba, closed its embassy in Havana, and banned trade to and forbid American private and business transactions with the island country.

With Cuba shedding off democracy and taking on a clearly communist state policy,

thousands of Cubans from the upper and middle classes, including politicians, top government officials, businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and many other professionals fled the country for exile in other countries, particularly in the United States. However, many other anti-Castro Cubans chose to remain and subsequently organized into armed groups to start a counter-revolution in the Escambray Mountains; these rebel groups’ activities laid the groundwork for Cuba’s next internal conflict, the “War against the Bandits”.

July 25, 2020

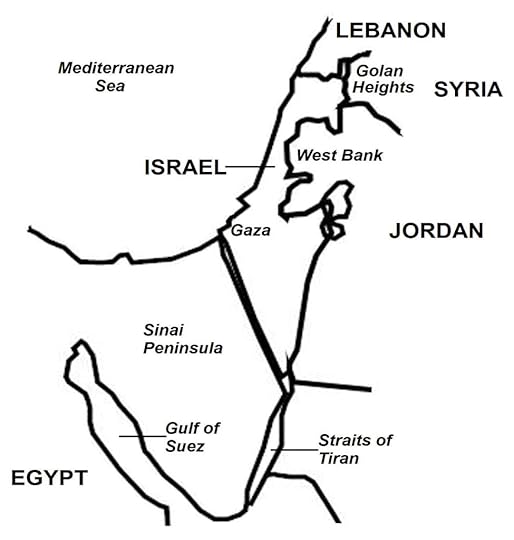

July 25, 1979 – Arab-Israeli Wars: Israel returns a part of the Sinai Peninsula

On July 25, 1979, Israel returned to Egypt a section of the Sinai Peninsula following the signing of a peace treaty between the two countries on March 26, 1979. In the treaty, Israel agreed to gradually withdraw its forces from the Sinai, which it subsequently completed in 1982. A peacekeeping force, the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) comprising contingents from many countries, entered the territory to ensure compliance with the treaty’s provisions. The treaty greatly advanced diplomatic relations between Egypt and Israel, which continues to this day.

Israel gained control of the Sinai during the Six-Day War in June 1967. Egypt attempted to recapture the Sinai during the Yom Kippur War in October 1973. Following a ceasefire following the second war, the two sides opened negotiations that led to the Sinai Interim Agreement in September 1975 where a buffer zone was established between the opposing forces. The two countries also agreed to eschew the use of force, and resolve their disagreements through peaceful means.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

With its decisive victory in the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights were integral territories of Egypt and Syria, respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, together with other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”, that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant that only armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently was not received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egypt carried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and government targets in the Sinai. In what is now known as the “War of Attrition”, Egypt was determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai. By way of

retaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel, and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly became involved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israel and Egypt to agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passed away. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President Anwar Sadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchly hostile to Israel, President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeli conflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations (UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign a

peace treaty with Israel and recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to negotiate. President Sadat, therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging the

Israelis from the Sinai. He decided that an Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israel to see the need for negotiations. Egypt began preparations for war. Large amounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, but

ineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number of ruses. The Egyptian Army constantly conducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoric eventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the true

strength of its armed forces. The government also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its war equipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated military hardware. Furthermore, when President Sadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egypt in July 1972, Israel

believed that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakened seriously. In fact, thousands of Soviet personnel remained in Egypt and Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syrian

counterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized for war.

Israel’s intelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the date of the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbers of Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egypt and Syria attacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiers and the entire Israeli Air Force. However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting a war and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carrying out a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War) to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur (which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, when most Israeli soldiers were on leave.

July 24, 2020

July 24, 1929 – Interwar Period: The Kellogg-Briand Pact goes into effect, renouncing war as an instrument of foreign policy

On July 24, 1929, the “General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy”, more commonly known as the Kellogg-Brian Pact, went into effect. Its secondary name derives from its authors, U.S. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. The instrument, first agreed to in August 1928 by the United States, France, and Germany, was joined within a year by 62 countries, including Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Soviet Union, and China. The instrument’s objective was for signatory states not to use war to resolve “disputes or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them”, and that states that fail to adhere would be “denied of the benefits furnished by the treaty”.

The Kellogg-Brian Pact failed in its objective: militarism grew in the 1930s, leading to the outbreak of World War II near the end of the decade.

(Taken from Events Leading up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Post-World War I Pacifism

Because World War I had caused considerable toll on lives and brought enormous political, economic, and social troubles, a genuine desire for lasting peace prevailed in post-war Europe, and it was hoped that the last war would be “the war that ended all wars”. By the mid-1920s, most European countries, especially in the West, had completed reconstruction and were on the road to prosperity, and pursued a policy of openness and collective security. This pacifism led to the formation in January 1920 of the League of Nations (LN), an international organization which had membership of most of the countries existing at that time, including most major Western Powers (excluding the United States). The League had the following aims: to maintain world peace through collective security, encourage general disarmament, and mediate and arbitrate disputes between member states. In the pacifism of the 1920s, the League resolved a number of conflicts (and had some failures as well), and by mid-decade, the major powers sought the League as a forum to engage in diplomacy, arbitration, and disarmament.

In September 1926, Germany ended its diplomatic near-isolation with its admittance to the League of Nations. This came about with the signing in December 1926 of the Locarno Treaties (in Locarno, Switzerland), which settled the common borders of Germany,

France, and Belgium. These countries pledged not to attack each other, with a guarantee made by Britain and Italy to come to the aid of a party that was attacked by the other. Future disputes were to be resolved through

arbitration. The Locarno Treaties also dealt with Germany’s eastern frontier with Poland and Czechoslovakia, and although their common borders were not fixed, the parties agreed that future disputes would be settled through arbitration. The Treaties were seen as a high point in international diplomacy, and ushered in a climate of peace in Western Europe for the rest of the 1920s. A popular optimism, called “the spirit of Locarno”,

gave hope that all future disputes could be settled through peaceful means.

In June 1930, the last French troops withdrew from the Rhineland, ending the Allied occupation five years earlier than the original fifteen-year schedule. And in March 1935, the League of Nations returned the Saar region to Germany following a referendum where over 90% of Saar residents voted to be

reintegrated with Germany.

In August 1938, at the urging of the United States and France, the Kellogg-Briand Pact (officially titled “General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy”) was signed, which

encouraged all countries to renounce war and implement a pacifist foreign policy. Within a year, 62 countries signed the Pact, including Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Soviet Union, and China. In February 1929, the Soviet Union, a signatory and keen advocate of the Pact, initiated a similar agreement, called

the Litvinov Protocol, with its Eastern European neighbors, which emphasized

the immediate implementation of the Kellogg-Briand Pact among themselves. Pacifism in the interwar period also manifested in the collective efforts by the major powers to limit their weapons. In February 1922, the five

naval powers: United States, Britain, France, Italy, and Japan signed the Washington Naval Treaty, which restricted construction of the larger classes of warships. In April 1930,

these countries signed the London Naval Treaty, which modified a number of clauses in the Washington treaty but also regulated naval construction. A further attempt at naval regulation was made in March 1936, which was signed only by the United States, Britain, and France, since by this time, the previous other signatories, Italy and Japan, were pursuing expansionist policies that required greater naval power.

An effort by the League of Nations and non-League member United States to achieve general disarmament in the international community led to the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva in 1932-1934, attended by sixty countries. The talks bogged down from a number of issues, the most dominant relating to the disagreement between Germany and France, with the Germans insisting on being allowed weapons equality with the great powers (or that they disarm to the level of the Treaty of Versailles, i.e. to Germany’s current military strength), and the French resisting increased German power for fear of a resurgent Germany and a repeat of World War I, which had caused heavy French

losses. Germany, now led by Adolf Hitler (starting in January 1933), pulled out of the World Disarmament Conference, and in October 1933, withdrew from the League

of Nations. The Geneva disarmament

conference thus ended in failure.

July 23, 2020

July 23, 1962 – Laotian Civil War: The major powers affirm the neutrality of Laos

On July 23, 1962, the major powers, United States, Soviet Union, China, United Kingdom, and France, signed the “International Agreement on the Neutrality of Laos” in Geneva. Apart from Laos itself, the other signatory countries were North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Burma, Canada, India, and Poland. The agreement arose from the “International Conference on the Settlement of the Laotian Question” (May 1961-July 1962) which sought a resolution to the ongoing Laotian Civil War. The signatory countries agreed to respect Laotian neutrality, abstain from interfering in Laos’ internal affairs, and refrain from drawing Laos into a military alliance or to establish military bases there.

Laos and Southeast Asia during the Indochina Wars.

Ultimately, the agreement was a failure as Laos became a battleground during the Indochina wars, which included its own civil war and the Vietnam War. The United States carried out a “secret war” and heavily bombed the Laotian countryside, while North Vietnam established a supply route called the Ho Chi Minh Trail to support the Pathet Lao and more important, the Viet Cong rebels in South Vietnam.

A former French colony, Laos had declared independence after World War II. But the returning French reoccupied the territory, as well as Vietnam and Cambodia. An insurgency broke out by the nationalist/communist North Vietnamese-backed, Pathet Lao. After the defeat of the French in the First Indochina War (1946-1954) and their withdrawal from the region, Laos regained its independence. In 1960, civil war broke out between the Royal

Lao Army, backed by the United States, and the Pathet Lao rebels, supported by communist North Vietnam.

(Excerpts taken from Laotian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background

In March 1889, France established a protectorate over the Kingdom of Luang Prabang. Then in October 1893, the French extended the boundaries of Luang Prabang after gaining more territory on the western side of the Mekong River. Also in 1893, following the Franco-Siamese War, France formally established Luang Prabang’s borders by annexing the regions of Vientiane, Xiangkhoang, and Luang Namtha. With the further addition of Phongsali and Houaphan, the French protectorate of Luang Prabang essentially delineated the borders of what is the present day country of Laos. The French protectorate of Laos formed part of French Indochina, which included Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina (these three regions forming modern-day Vietnam), and Cambodia.

In the early 1940s, France encouraged nationalism among the different Lao tribes to counteract Thailand’s irredentist territorial ambitions on Laos. This had the unintended consequence of generating anti-French, anti-colonial sentiment among Laotians, which led to the founding of the short-lived separatist organization, Lao Pen Lao (Lao for Laos).

In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe, and in December 1941, in the Asia Pacific. In June 1940, France fell to Germany, and the new French Vichy government became allied with the Axis Powers, including Japan. In August 1940, Japan and Vichy France signed the Matsuoka-Henry Pact, which granted Japanese forces access to French Indochina for Japan’s invasion of other parts of Southeast Asia. The treaty also allowed French colonial authorities to continue governing Indochina

But by 1944, World War II had turned decisively in favor of the Allied Powers. In September of that year, France was recaptured by the Allies, and a pro-Allied provisional government came to power. By early 1945, French commando infiltrations into Indochina and the subsequent formation of French-Lao

guerilla resistance groups forced the Japanese to dismantle French colonial authority in Indochina. As a result, the Japanese ruled Indochina directly. The Japanese then exerted pressure on King Sisavang Vong, the pro-French Lao monarch, who in April 1945, ended the French protectorate and declared Lao

an independent state. But just four months later, on August 14, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies, bringing an end to World War II.

In the immediate post-war period, Indochina was racked by anarchy and unrest. In Laos, rival political elements competed in a power struggle to fill the void left by the sudden Japanese capitulation. In Luang Prabang (the royal capital of Laos), Prince Phetsarath, the Prime Minister, tried to convince King Sisavang Vong to implement policies relevant to an independent Laos. King Sisavang Vong refused, as he was determined to permit the restoration of French rule. After being stripped of his positions of Prime Minister and viceroy, on August 27, 1945, Phetsarath took control of Vientiane (Laos’ administrative capital). There, on September 15, 1945, Phetsarath declared a unified Laos

comprising Luang Prabang and the four southern provinces of Khammouan, Savannakhet, Champasak, and Saravane (Figure 14).

On October 7, 1945, a Lao partisan force led by Prince Souphanouvong arrived at Savannakhet, where other nationalists had taken control of the town’s administration.

Their combined forces, with Souphanouvong as over-all commander, proceeded north to join Phetsarath in Vientiane. There, in October 1945, the Lao nationalists, now led by the three princes, the brothers Phetsarath and Souvanna Phouma, and their half-brother Souphanouvong, declared Laos’ independence under a revolutionary government called Lao Issara (“Free Laos”). (Souvanna Phouma and Souphanouvong would later play major roles in the coming Laotian Civil War.) On October 10, 1945, the Lao Issara sent a force to Luang Prabang, where it forced King Sisavang Vong into submission.

However, the Lao Issara failed to consolidate power. In the immediate post-World War II period, major political decisions were dictated by the victorious Allied Powers, which accepted France’s desire to restore colonial rule in Indochina. But in the meantime that France was yet assembling a force for that

purpose, the Allies also allowed the Chinese Nationalist forces to enter Laos to formally accept the Japanese surrender there.

As a result, Laos became partitioned into areas of control by different forces. The Lao Issara controlled the capital and the towns of Thakhek and Savannakhet. Chinese forces held the northern regions (Luang Prabang, Phongsali and Luang Namtha). The French-Lao forces controlled the south (Xiangkhoang, Khammouan, and Savannahkhet provinces, together with Pakxe and Saravane, where the pro-French political warlord Prince Boun Oum operated). And the Viet Minh (a Vietnamese anti-French revolutionary movement)

occupied Houaphan along the northeast border with Vietnam.

The Lao Issara, apart from its lack of foreign support, faced many other major problems: a dearth of money to run a government, a shortage of weapons, and political infighting. These problems undermined the Laos Issara’s capacity to survive. By October 1945, the French had reestablished its military presence in southern Indochina (Cochinchina and Cambodia). From Saigon, French troops advanced north

toward Laos. In January 1946, French-Lao forces seized full control of Laos’ southern regions and soon entered Savannakhet, meeting only light resistance. In March 1946, following lengthy French-Nationalist Chinese negotiations, China withdrew its forces from Laos (and Vietnam).

On March 21, 1946, at the decisive Battle of Thakhek, French-Lao forces attacked and defeated the Lao Issara. A few days later, the Lao Issara government abandoned the capital, Vientiane, which was taken over by the French. Arriving at Luang Prabang on March 23, 1946, the Lao Issara made appeasement with Sisavang Vong, restoring him to the throne. King Sisavang Vong only reluctantly accepted reconciliation, and on April 23, 1946, he announced a new constitution and declared Laos’ unity. French forces continued their

advance north, and entered Luang Prabang in May 1946. The French ended the remaining Lao Issara resistance, and presently regained control of all Laotian territory.

France reinstated King Sisivang Vong as monarch over Laos, and then reversed its plan to restore direct colonial rule. Instead, the French government prepared to hand over self-government to the Lao people. In December 1946, elections were held to the Lao National Assembly (the state legislature), which then convened to prepare a new constitution. In May 1947, the completed constitution, ratified by the king, declared Laos

an autonomous state within the French Union.

In July 1949, in the Franco-Lao General Convention, France granted the Lao government greater prerogatives in Laos’

foreign affairs. In February 1950, with France again confirming Laos’ self-determination status, the United States and Britain recognized Laos as a sovereign state. In December 1955, Laos joined the United Nations.

However, despite Laos’ apparent independence, France retained a virtual stranglehold over the country, controlling Laos’ finance, defense, and major foreign policy functions. French forces also were stationed in the country, which by the late 1940s, had become extremely vital to French regional interests, because of the ongoing conflict

in Vietnam (First Indochina War, separate article).

Meanwhile, the Lao Issara, following its defeat, fled to Thailand, where it set up a government-in-exile and a guerilla force. Lao Issara fighters then began launching cross-border attacks into Laos. But in November 1947, a military coup in Thailand brought to power a regime that restored relations with France, recognized Laos, and dismantled Lao Issara bases in Thailand. The Lao Issara then experienced infighting within its leadership, particularly between Phetsarath and Souphanouvong, on whether to seek assistance from the communist Viet Minh to continue the revolutionary struggle. Souphanouvong, a Marxist ideologue, subsequently was expelled from the Lao Issara. He then moved to Vietnam, where he previously had lived many years, and came into contact with Ho Chi Minh, the Vietnamese

communist revolutionary leader.

In October 1949, the remaining Lao revolutionaries disbanded the Lao Issara and dissolved their government-in-exile. Souvanna Phouma accepted a Lao government amnesty and returned to Laos, where he would play a major political role in the next 25 years. After the 1951 National Assembly elections, he became Prime Minister, holding this position until 1954. In subsequent years, he would return as Prime Minister in 1956-1958, 1960, and 1962-1975.

Phetsarath remained in Thailand, and ceased to play an important role in Laotian politics. In Vietnam, Souphanouvong met with other Lao anti-French radicals. These included communists, but also non-communists, such as former Lao officials and royals, and ethnic minorities, who saw the Lao royal government as no more than a French puppet. In August 1950, these anti-colonialists formed the Neo Lao Issara (Free Laos Front), purportedly a united front of Lao opposition groups comprising different political persuasions. A revolutionary government also was formed,

called the “Resistance Government of the Lao Homeland”, led by Souphanouvong as its president. The Western press soon began using its shortened name, “Pathet Lao” (Lao Homeland), to refer to this organization.

During its revolutionary struggle, the Pathet Lao would put great efforts to portray itself as an ideologically and politically pluralistic organization. In large part, it relied

on the prestige of Prince Souphanouvong.

In fact, however, the Pathet Lao was controlled behind the scenes by hard-line communists led by Kaysone Phomvihane and Nouhak Phoumsavan. To gain the widest popular support, the Pathet Lao kept hidden its Marxist background. It also did not overtly call for the end of the Lao monarchy, and did not reveal its desire to implement agrarian reform and collectivized farming. Land reform ran contrary to Laos’ socio-economic structure, as most farmers owned their own lands, and landless peasantry was almost non-existent in Laos.

The communist movement in Laos traces its origin to the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP), formed in 1930. The ICP consisted nearly exclusively of ethnic Vietnamese, and had as its main goals the overthrow of French rule in Indochina and the establishment of socialist governments in an independent Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. In February 1951, the ICP reorganized into three separate but allied communist parties, one each for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. The Lao communist group, in March 1955, secretly formed the Lao People’s Party (LPP), which later in February 1972, was renamed the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP), both of which were not known to the general public at that time.

As early as January 1949, with the military guidance and support provided by the Viet Minh, the fledging Lao communist movement

organized an armed militia to launch the revolutionary struggle in Laos. By the early 1950s, with the formation of the Pathet Lao and also with Viet Minh leading the way in the escalating First Indochina War, the Lao guerillas were transformed into an auxiliary force behind the Viet Minh.

July 22, 2020

July 22, 1942 – World War II: Nazi Germany begins deporting Polish Jews to the Treblinka extermination camp

On July 22, 1942, Nazi Germany began the mass deportation of Polish Jews in the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka extermination camp. In all, some 250,000 of the 400,000 total residents were moved in the summer of 1942, with “resettlement in the East” as the operation’s stated objective. After an uprising in April-May 1943, the ghetto was shut down and the remaining residents were moved to extermination camps. At Treblinka, some 300,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto were killed in the gas chambers or by firing squad; another 90,000 died from starvation or disease.

The Germans had set up ghettos in occupied Europe to segregate Jews, gypsies (Romani) and other “undesirables” for eventual

extermination. In total, some 3 million Polish Jews (50% of all Jews in the Holocaust, and 90% of all Jews in Poland) perished in the Holocaust.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Events Leading up to World War II in Europe

Hitler and the Nazis in Power

Adolf Hitler imposed Nazi racial policies, which saw ethnic Germans as the “master race” comprising “super-humans” (Ubermensch), while certain races such as Slavs, Jews, and Roma (gypsies) were considered “sub-humans” (Untermenschen); also lumped with the latter were non-ethnic-based groups, i.e. communists, liberals, and other political enemies, homosexuals, Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc. Nazi lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism into Eastern Europe and Russia called for eliminating the Slavic and other populations there and replacing them with German farm settlers to help realize Hitler’s dream of a 1,000-year German Empire.

In Germany itself, starting in April 1933 until the passing of the Nuremberg Laws in

September 1935 and beyond, Nazi racial policy was directed against the local Jews, stripping them of civil rights, banning them from employment and education, revoking their citizenship, excluding them from political and social life, disallowing inter-marriages with Germans, and essentially declaring them

undesirables in Germany.

By far, the most famous extermination program was the Holocaust, where six million Jews, or 60% of the nine million pre-war European Jewish population, were killed in the period 1941-1945. German anti-Jewish policies began in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, and violent repression of Jews increased at the

outbreak of war. Jews were rounded up and confined to guarded ghettos, and then sent by freight trains to concentration and labor camps. By mid-1942, under the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” decree, Jews were

transported to extermination camps, where they were killed in gas chambers. Some 90% of Holocaust victims were Jews. Other similar exterminations and repressions were carried out against ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Poles,

and other Slavs and Romani (gypsies), as well as communists and other political enemies, homosexuals, Freemasons, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. In Germany itself, a clandestine

program implemented by German public health authorities under Hitler’s orders, killed tens of thousands of mentally and physically disabled patients, purportedly under euthanasia (“mercy killing”) procedures, which actually involved sending patients to gas chambers, applying lethal doses of medication, and through starvation.

Some 12-15 million slave laborers, mostly civilians from captured territories in Eastern Europe, were rounded up to work in Germany,

particularly in munitions factories and agriculture, to ease German labor shortage caused by the millions of German men fighting in the various fronts and also because Nazi policy discouraged German women from working in industry. Some 5.7 million Soviet POWs also were used as slave labor. As well,

two million French Army prisoners were sent to labor camps in Germany, mainly to prevent the formation of organized resistance in France

and for them to serve as hostages to ensure continued compliance by the Vichy government. Some 600,000 French civilians also were conscripted or volunteered to work in German plants. Living and working conditions for the slave laborers were extremely dire, particularly for those from Eastern Europe. Some 60% (3.6 million of the 5.7 million) of Soviet POWs died in captivity from various causes: summary executions, physical abuse, diseases, starvation diets, extreme work, etc.