Daniel Orr's Blog, page 97

May 22, 2020

May 22, 1967 – Six-Day War: Egypt closes the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping

On May 22, 1967, Egypt announced that the Straits of Tiran would be closed to “all ships flying Israeli flags or carrying strategic materials”, to take effect on May 23. Some 90% of Israeli oil passed through the Straits of Tiran. Oil tankers that were due to pass through the straits were delayed. Israel had previously warned that the closure of the waterway would be an act of war.

The waterway’s closure greatly increased tensions between the Arab states and Israel. Just one week earlier, May 15, 1967, Egypt had ordered the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) to leave the Sinai Peninsula; the UNEF had been tasked to preserve the peace in the territory since the end of the Suez Crisis (October-November 1956).

Background

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War produced tensions between Israel and surrounding Arab countries. Then in 1956, Egypt seized control of the Suez Canal, which triggered the Suez Crisis, a conflict where Britain and France sent their forces to Egypt to take back control of the Suez Canal. Israel joined the Anglo-French operation by invading and capturing the Sinai Peninsula. The United Nations, or UN, subsequently forced Israel to withdraw its forces from the Sinai Peninsula.

In the 1960s, tension rose again in the Middle East, initially between Syria and Israel. Palestinian militants belonging to the Palestinian Liberation Organization, or PLO, Fatah, and other nationalist

guerilla movements, carried out armed raids and sabotage operations in Israel from bases in Syria,

Jordan, and southern Lebanon. In the first three months of 1967, some 270 armed incidents occurred between Israel and its Arab neighbors. Israeli planes struck at suspected Palestinian bases inside Syria. Israel and Syria also were locked in a dispute regarding the water resources in the Jordan River, ultimately leading Israel to launch air strikes against Syrian water facilities in August 1965.

Border clashes also broke out intermittently. Israeli planes attacked Syrian military bases and vital public infrastructures, and shot down a number of Syrian planes in air battles. In April 1967, Israeli and

Syrian forces clashed in a major battle that included infantry, armored, artillery, and air force units.

Persistent PLO infiltrations from Syria prompted Israel, in May 1967, to issue a warning to Syria of Israeli retaliation. Then, the Soviet Union released an intelligence report (later discovered to be erroneous) to the Arabs that indicated an Israeli troop buildup along the Syrian border. As a result, Syria also massed its forces along the border with Israel.

Egypt was bound to a defense agreement with Syria and Jordan. On May 18, the Egyptian government expelled the UN peacekeepers in the Sinai, and sent army units to the Egypt-Israel border, thereby militarizing the Sinai Peninsula. A few days later, Egypt prevented Israel commercial vessels from entering the Straits of Tiran. Israel viewed the blockade as a provocation for war.

On May 28, Israel prepared for war with a call up of reservists. Three days later, foreign embassies in Israel instructed their citizens to leave in anticipation for war. On June 1, Israel finalized its war plans. Then in a meeting held on June 4, Israel’s civilian and military leaders set the date for war for the following day, June 5.

Israel fought the Six-Day War in three sectors: against Egypt in the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula, against Jordan in the West Bank, and against Syria

in the Golan Heights.

War

On the morning of June 5, Israeli planes attacked Egyptian airbases in the Sinai Desert and in Egypt proper. Hundreds of Egyptian planes, nearly half of Egypt’s Air Force, were destroyed on the ground. Israeli air strikes continued the whole day, knocking out the Egyptian Air Force, which was the strongest among the Arab countries. In one coup, Israel gained air domination, which decided the outcome of the war. The Six-Day War was on.

May 21, 2020

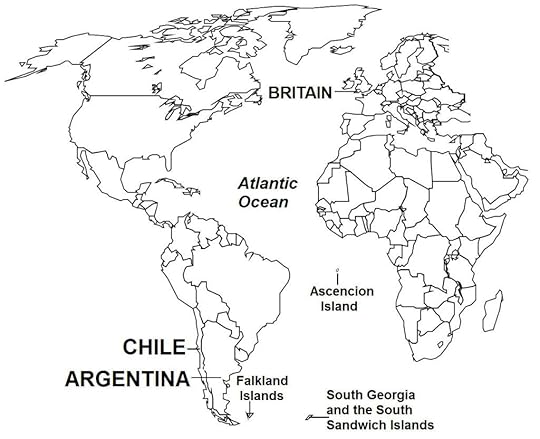

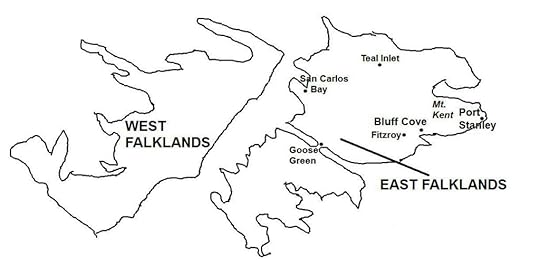

May 21, 1982 – Falklands War: British Marines land in San Carlos

By the third week of May 1982, the ships carrying the British ground forces had arrived at the waters off the Falklands. British authorities decided to launch the ground war despite not having achieved total control of the sky because the rough seas and deteriorating weather conditions indicated that winter in the South Atlantic was fast approaching. San Carlos Bay, a lightly defended area located about centrally north of the East Falklands, was chosen as the landing point. The British were unwilling to launch a direct attack on the capital Port Stanley, believing this would cause heavy British casualties.

Falkland Islands

Falkland IslandsOn May 21, 1982, some 4,000 British Marines landed at San Carlos Bay. After easily overpowering the small Argentine garrison, the British soldiers secured the landing zone, where British transport ships soon arrived to unload weapons and supplies. The Argentineans carried out many air attacks, sinking the British frigates HMS Ardent and HMS Antelope on May 21 and May 24, respectively, and the destroyer HMS Coventry on May 25. Also badly damaged were the British frigates HMS Argonaut and HMS Brilliant. Many other ships also could have been hit or suffered heavy damage were it not that Argentinean pilots often released their rockets too low, which exploded with little effect or did not detonate on time.

The British incurred heavy losses at San Carlos Bay, but succeeded in completing the landings.

However, the loss of a freighter carrying the transport helicopters for the troops meant that the British ground forces at San Carlos Bay could not be airlifted to Port Stanley as planned, but would have to walk the 80 kilometers of open terrain in bad weather to the capital. The main force of 3,000 troops was tasked to advance to Port Stanley.

Background

Argentina invaded Falklands on April 2, 1982 when 100 Argentinean commandos were landed at Port Stanley, the capital, ahead of the main force of 2,000 soldiers who later were landed amphibiously. After some skirmishes, the island’s British garrison of 60 soldiers surrendered, and the Falklands came under Argentine control.

Argentina then set up a military command to administer the islands. British authorities and military personnel were expelled, and Falklanders were given the option to leave with compensation. (More details on the war here.)

May 20, 2020

May 20, 1941 – World War II: German paratroopers invade Crete

On May 20, 1941, German paratroopers landed on Crete, Greece’s

largest island on the south. In early June 1941, the Axis conquest of all Greek

territories was completed by the German capture of Crete

after a two-week offensive. The Battle

of Crete involved German paratroopers and glider units seizing strategic points

in the northern coast preparatory to the arrival of other ground forces. The initial German landings brought near

disaster, as the paratroopers suffered heavy casualties and the Luftwaffe lost

a significant number of planes. But with

the capture of Maleme airfield following an Allied communications error, the

Germans established a toehold in Crete for

more troops to arrive. On June 1, 1941,

the Germans seized the whole island; some 18,000 Allied soldiers who had failed

to be evacuated were captured.

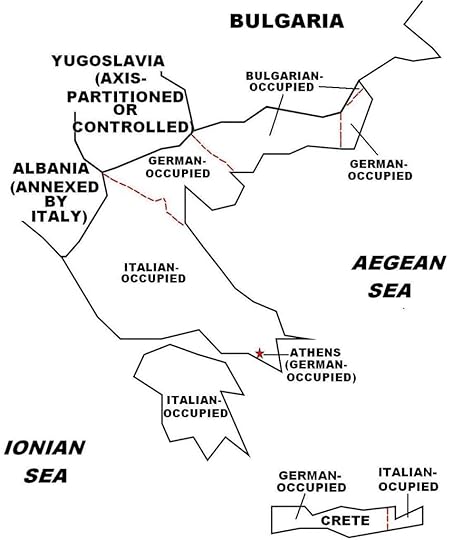

Axis occupation of Greece during World War II

Axis occupation of Greece during World War IIIn the aftermath of the Axis campaign, Greece was divided into Axis occupation zones,

with Germany taking the most

strategically important regions, including Athens,

and the Italians occupying much of the rest of Greece. Bulgaria,

which did not participate in the invasion, was allowed to occupy Western Thrace

and Eastern Macedonia. In Athens, the

Germans set up a collaborationist government under the renamed “Hellenic State”, which held no real power but

served merely as a conduit for German impositions.

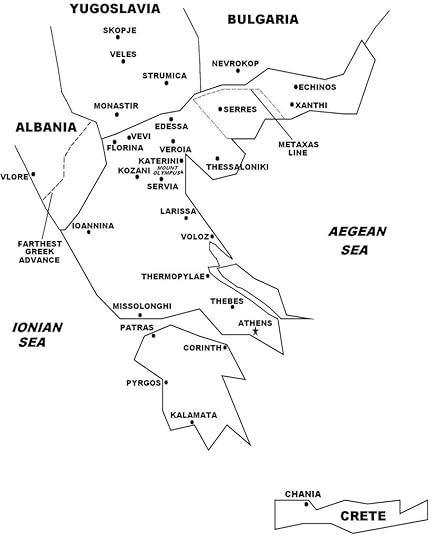

Background On April 6, 1941, Germany launched Operation Marita, the invasion of Greece, with the German 12th Army in Bulgaria launching offensives into southern Yugoslavia, whose capture would achieve the strategic objective of cutting off the rest of Yugoslavia in the north with Greece in the south. By the second week, the Germans had captured nearly the whole Greek mainland. Over the course of five nights starting on April 24, 1941, the British Royal Navy and other Allied ships evacuated 55,000 British and Dominion troops to Crete and Egypt. The British also left behind most of their weapons and military equipment, including trucks, tanks, and planes. For more information on this war, click here.

Battle of Greece

Battle of Greece

May 19, 2020

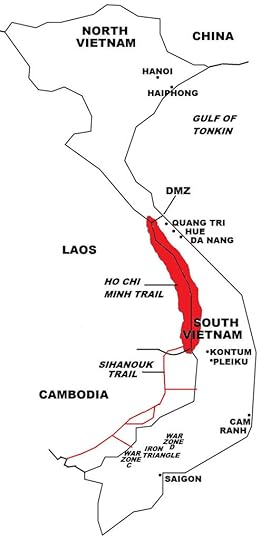

May 19, 1959 – Vietnam War: North Vietnam forms Group 559, tasked to establish a supply line to South Vietnam; as a result, the Ho Chi Minh Trail is built

In January 1959, North Vietnam agreed to provide military support to the Viet Cong. In May of that year, it formed the 559th Transportation Group of the North Vietnamese Army, which was tasked to establish a supply route to South Vietnam. This supply route, which initially passed directly through the DMZ, was intercepted by South Vietnamese forces. North Vietnam then moved its supply route to eastern Laos and Cambodia, where manpower and war materials were transported to the Viet Cong in South Vietnam. The supply route that developed, which became known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, was located close to the shared borders of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, and initially consisted of foot tracks in sparsely inhabited rugged mountains that were covered in the dense canopy of tropical rainforests. One year earlier (May 1958), North Vietnamese forces had crossed over into and occupied sections of eastern Laos, including the strategically placed Tchepone in Savannakhet Province, in support of the Pathet Lao, a Laotian communist movement that was fighting a revolutionary war in Laos against the West-aligned Royal Lao Government.

Ho Chi Minh Trail and other sites during the Vietnam War

Within a few months after Group 559’s formation, weapons and supplies from North Vietnam

were being transported in large quantities through the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the insurgents in South Vietnam. As well, the first batches of Viet Minh

southerners who had moved to North Vietnam following the Geneva Accords and were now officers and soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army, were trekking down the Ho Chi Minh Trail toward South Vietnam, where they would serve as the leaders and advisers of, or otherwise joined the ranks of, the Viet Cong.

Background

In July 1954, the First Indochina War ended with the Geneva Accords, which partitioned the French colony of Vietnam into two military zones at the 17th parallel, the northern and southern zones. The northern zone was assigned to and occupied by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV). The DRV was led by the Viet Minh (Vietnamese: Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng Minh Hội, or “League for the Independence of Vietnam”), a nationalist communist-led organization headed by the revolutionary Ho Chi Minh, who had fought to end French colonial rule in Vietnam. The southern zone was assigned to the French-established State of Vietnam.

The Geneva Accords stipulated that Vietnam’s

partition at the 17th parallel was only a temporary expedient to separate the warring sides. The 17th parallel was designated as a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles wide (3 miles on both sides of the line), and was not a political/territorial boundary, and the

reunification of the two halves of Vietnam was to be undertaken after nationwide elections could be held in July 1956. However, the reunification elections did not take place, and the DRV in the northern zone and the State of Vietnam in the southern zone became de facto separate states, with the former becoming more

widely known as North Vietnam, and the latter known as South Vietnam.

In Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam, Ho and his DRV government consolidated power and established a Marxist state. All lands and industries were nationalized, agrarian reform was implemented, and dissent suppressed. As in the First Indochina War, North Vietnam received military and economic

support from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Soviet Union. In South Vietnam, which officially was a democracy based along Western lines, Prime Minister Ngo Dinh Diem only gradually consolidated power. In April 1955, Diem launched military campaigns to suppress the militant religious

groups, Cao Dai and Hoa Hao, and the organized crime syndicate, Binh Xuyen. These operations were successful, but only after some intense fighting in the capital, Saigon, that left hundreds of people dead and thousands of others homeless. Then in October 1955, to determine South Vietnam’s political future, a referendum (which the government manipulated using fraud) showed that the South Vietnamese overwhelmingly favored setting up a republic, and rejected the return of the monarchy. Following the referendum, Diem declared the formation of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) and named himself as its (first) President. Thereafter, President Diem reached the peak of his political power, although his government became mired in corruption, nepotism, and stagnation. Diem soon also repressed all forms of political dissent.

Also in 1955, President Diem launched a suppression campaign against the re-emerging communist movement in South Vietnam, and in August 1956, instituted the death penalty for persons being involved in communism. In the aftermath of the Geneva Accords, some 100,000 Viet Minh southerners migrated to North Vietnam, although about 10,000 Viet Minh southerners, with the encouragement of the North Vietnamese leadership, remained in South Vietnam. These stay-behind Viet Minh communists carried out political activism using front organizations, such as religious, farmers, students, workers, and women groups, in order to conceal their political objectives, and also to appeal to a wider segment of the population.

In March 1956, the fledging South Vietnamese insurgency asked for military support from North Vietnam, which was turned down by the Ho

government, because China and the Soviet Union were reluctant to becoming involved in another potentially costly war so soon after the recent Korean War (which just ended nearly three years earlier, in July 1953). But in December 1956, when reunification of Vietnam became unlikely and North Vietnam and South Vietnam were forming separate states, North Vietnam agreed to provide only limited support to the insurgents.

In 1957, the South Vietnamese insurgents, whom the Saigon government called Viet Cong (Vietnamese communists; a contraction from the Vietnamese: Việt Nam Cộng-sản), unleashed a wave of violence in South Vietnam, with many incidents of assassinations, murders, bombings, and other terrorist acts taking place. By 1958, the Viet Cong had established a command structure, with militias organized into a regular army-type organization. For more information on this war, click here.

May 18, 2020

May 18, 1955 – First Indochina War: The end of Operation Passage to Freedom, where the U.S. Navy evacuates 310,000 Vietnamese civilians and soldiers, and non-Vietnamese personnel of the French Army from communist North Vietnam to South Vietnam

On May 18, 1955, the U.S. Navy completed Operation Passage to Freedom, evacuating some 300,000 Vietnamese civilians, soldiers, and non-Vietnamese personnel of the French Army from communist North Vietnam to South Vietnam. This action was part of the larger operation led by the French Air Force and hundreds of ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy as well as other Western countries that moved some one million Vietnamese northerners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upper classes consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communist politicians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone. This number included more than 200,000 French citizens and soldiers in the French army. The campaign to evacuate particularly targeted Vietnamese Catholics – some 60% of the north’s 1 million Catholics did so, and accounted for 85% of the evacuees to the south.

This mass movement was a result of a stipulation in the Geneva Accords (May 8, 1954) where representatives from the major powers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochina states: Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, Democratic Republic of

Vietnam (DRV) in the north, and State of Vietnam in the south, met at Geneva (the Geneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina (as well as

Korea). The Conference was held following the decisive French defeat at Dien Bien Phu (March-May

1954) in the First Indochina War (December 1946 – July 1954).

Present-day Southeast Asia

On the Indochina issue, on July 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by the parties. The ceasefire was agreed to by France and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17th parallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional military

demarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The partition was intended to be temporary, pending elections in 1956 to reunify the country under a national government.

The French and their allies in the northern zone departed and moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh in the southern zone departed and moved to the northern zone (although some southern Viet Minh remained in the south on instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 days where Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on either side of the line.

The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and State of Vietnam in a massive propaganda campaign to encourage the northerners to move south, including spreading rumors that Red China would invade the north, that the northern government would confiscate people’s possessions, and distributing pamphlets with slogans such as “Christ has gone south” and “the Virgin Mary has departed from the North”, alleging anti-Catholic persecution under Ho Chi Minh.

While one million moved from north to south, some 100,000 southerners, mostly Viet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, moved to the northern zone.

May 17, 2020

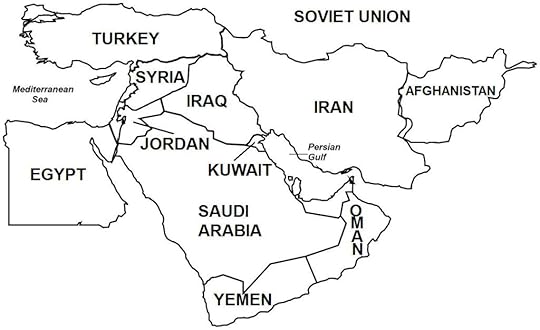

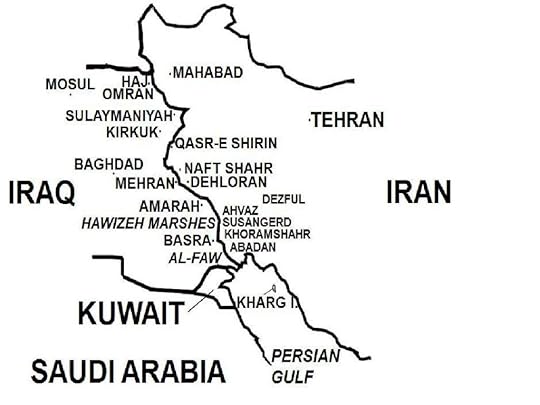

May 17, 1987 – Iran-Iraq War: The U.S. frigate, USS Stark, is struck by two missiles from an Iraqi jet fighter

On May 17, 1987, the USS Stark was hit by two missiles fired by an Iraqi jet aircraft, killing 37 personnel and injuring 21 others. The American ship was part of the Middle East Task Force assigned to patrol off the Saudi Arabian coast during the on-going Iran-Iraq War (September 1980-August 1988). Emergency contingencies saved the ship from sinking, arriving at Bahrain the next day for temporary repairs before returning to the United States.

During the Iran-Iraq War, the United States backed the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein. Prior to the war, U.S.-Iraqi relations had been distant, but greatly improved during the conflict. The United

States provided Iraq with several billion dollars’

worth of economic aid, the sale of dual-use technology, non-U.S. origin weaponry, military intelligence, and special operations training.

On the other hand, the U.S. had cut diplomatic relations with Iran in April 1980 following the storming by Iranian students of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran (November 1979) and what would subsequently be a hostage crisis lasting 444 days. Relations had been on the decline following the ouster of Mohammad Reza Shah Pavlavi and Iran setting up an anti-American, hard-line theocracy under Ayatollah Khomeini.

U.S. President Jimmy Carter had agreed to let the Shah into the United States, prompting the Iranians to suspect that the U.S. government and the Shah were conspiring to undermine the Iranian Revolution. This suspicion has often been used by the Iranian revolutionaries to justify their claims that the former monarch was an American puppet, and this led to the storming of the American embassy by radical students allied with the Khomeini faction.

For a period following the USS Stark incident, relations between Iraq and the United States were strained. Nevertheless, by mid-1987, both sides had overcome this issue. Although lingering suspicions about the United States remained, Iraq welcomed greater, even if indirect, American diplomatic and military pressure to try to end the war with Iran. For the most part, the Iraqi government believed the United States supported its position that the war was being prolonged only because of Iranian intransigence.

(The Iran-Iraq War was in part brought about by Iran’s transition to a hard-line theocratic regime. Relations between the two countries deteriorated as Iran’s Islamist fundamentalism contrasted sharply with Iraq’s secular, socialist, Arab nationalist agenda. This breakdown in relations was only the latest in a long history of Arab-Persian hostility that resulted from a complex combination of ethnic, sectarian, political, and territorial factors. Click here for more information on the war.)

May 16, 2020

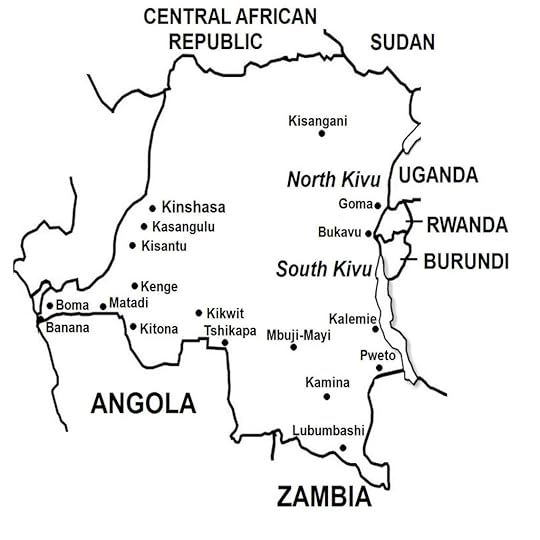

May 16, 1997 – First Congo War: President Mobutu flees Zaire

On May 16, 1997, President Mobutu Sese Seko fled Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) in the wake of the First Congo War (October 1996 – May 1997). The war was triggered when in November 1996, Mobutu ordered that Zairian ethnic Tutsis (called Banyamulenge) must leave the country or face death. The Tutsis broke out in rebellion and were soon supported by Rwanda and Uganda (and later Burundi). This alliance was quickly joined by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the insurgent leader who had for three decades been conducting a low-level rebellion against the Zairian government. Mobutu’s regime was notorious for massive corruption, nepotism, and utter disregard for the socio-economic conditions of the country, and Mobutu himself had amassed a huge personal wealth amounting to billions of dollars stolen from the public coffers.

Kabila joined his forces with the Banyamulenge militia; together, they united with other anti-Mobutu rebel groups in the Kivu, with the collective aim of overthrowing the Zairian dictator. Kabila soon became the leader of this rebel coalition. In December 1996, with the support of Rwanda and Uganda, Kabila’s rebel coalition wrested control of the border areas of the Kivu. There, Kabila formed a quasi-government that was allied to Rwanda and Uganda.

When the fighting ended, some areas of Zaire’s eastern provinces had virtually seceded, as the Zairian government was incapable of mounting a strong military campaign into such a remote region. In fact, because of the decrepit condition of the Zairian Armed Forces, President Mobutu held only nominal control over the country.

More critically, President Mobutu had become the enemy of Rwanda and Angola, as he provided support for

the rebel groups fighting the governments in those countries. Other African countries that also opposed

Mobutu were Eritrea, Ethiopia, Zambia,

and Zimbabwe.

In December 1996, Angola

entered the war on the side of the rebels after signing a secret agreement with

Rwanda and Uganda. The Angolan government then sent thousands of

ethnic Congolese soldiers called “Katangese Gendarmes” to the Kivu

Provinces. These Congolese soldiers were

the descendants of the original Katangese Gendarmes who had fled to Angola in the early 1960s after the failed

secession of the Katanga Province from the Congo.

Backed by units of the Rwandan and Ugandan Armed Forces, Kabila’s

coalition force advanced steadily across central Zaire

for the capital, Kinshasa. Kabila met only light resistance, as the

Zairian Army collapsed, with desertions and defections widespread in its

ranks. Crowds of people in the towns and

villages welcomed Kabila and the foreign armies as liberators.

Many attempts were made by foreign mediators (United Nations, United

States, and South Africa)

to broker a peace settlement, the last occurring on May 16, 1977 when Kabila’s

forces had reached the vicinity of Kinshasa. The Zairian government collapsed, with

President Mobutu fleeing the country.

Kabila entered Kinshasa

and formed a new government, and named himself president. The First Congo War was over; the second

phase of the conflict broke out just 15 months later.

(Click here more information on the First Congo War.)

May 15, 2020

May 15, 1904 – Russo-Japanese War: Two Japanese battleships, Hatsuse and Yashima, sink after hitting mines laid by the Russian minelayer Amur

On May 15, 1904 on the waters off Port Arthur (now Lushunkou, China), the Japanese battleship Hatsuse struck two mines and sank with the loss of 496 crew. Another Japanese ship Yashima also sank after hitting two mines. The incident was part of the ongoing Russo-Japanese War (February 1904-September 1905) for control of southern

Manchuria and Korea.

The Russo-Japanese War was fought for control of Korea and southern Manchuria

Since the outbreak of the war, the Japanese ships had been laying siege on the strong Russian outpost of Port Arthur. The Russian fleet in Port Arthur twice attempted to break out (April and August 1904) but was forced back by the strong Japanese naval presence. On the other hand, the Japanese ships were wary of entering Port Arthur because of the powerful Russian shore batteries. Ultimately, the Japanese captured Port Arthur in January 1905, ending a nine-month siege. Port Arthur’s fall demoralized the Russian Army in Manchuria, and shocked the Russian population.

At the start of the war, the Japanese took control of the Korean Peninsula, meeting no Russian opposition. The Japanese then also advanced into southern Manchuria up to Mukden. Subsequently, Japan was beset with many political and economic problems at home. In Manchuria, the Japanese Army was experiencing serious logistical problems and so decided to abandon plans to advance further north.

The most significant naval engagement of the war was the Battle of Tsushima (May 27-28, 1905), where the Japanese Navy scored a stunning one-sided victory. The Russian Second Pacific Fleet was destroyed, with 10,000 Russian sailors killed or captured, 21 ships sunk, including 7 battleships, and of the 38 Russian ships that started the voyage, only 3 managed to reach Vladivostok. Japanese losses were 700 dead or wounded, and only 3 torpedo boats sunk.

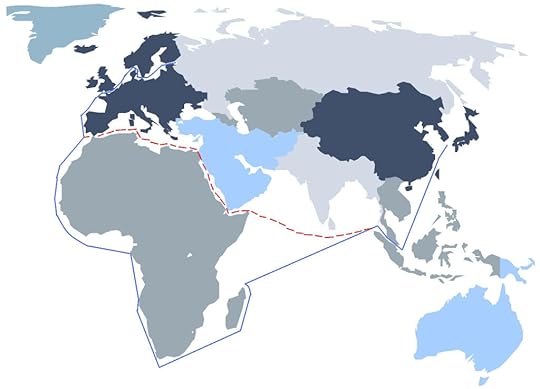

Route of the Russian Second Pacific Fleet

The Battle of Tsushima sent reverberations around the World – an Asian nation dealing a crushing defeat on a European power. In Russia,

Tsar Nicholas II abandoned his hard-line position against Japan. On June 8, 1905, one week after the Tsushima battle, Russia agreed to negotiate an end to the war. By this time also, Russia was experiencing massive unrest (the Russian Revolution of 1905) as a result of strikes, demonstrations, peasant protests, and soldiers’ mutinies.

Meanwhile, Japan was faced with a deteriorating economy and mounting foreign debt, and also

desired to end the war. The Japanese Army was experiencing logistical problems in Manchuria, and the economic problems at home could seriously undermine Japan’s ability to wage a protracted war. As early as mid-1904, Japan had sought third-party mediation to end the war. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt agreed to act as mediator, and peace talks opened in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in June 1905.

On September 5, 1905, Russia and Japan signed the Treaty of Portsmouth, ending the war. By the terms of the treaty, Japan gained control of Korea; Russia withdrew its forces from Manchuria but retained the Chinese Eastern Railway; and the Russian lease on the Liaodong Peninsula, including Port Arthur, was transferred to Japan. Sakhalin

Island was partitioned at the 50th parallel, with Japan gaining the southern portion and Russia retaining the northern side.

For Japan, the long-term effects of the war were much more favorable, as it became the supreme power in East Asia, and its status as an equal of the major European powers was strengthened. In August 1910, Japan abrogated Korea’s nominal independence (long recognized by the major powers) and annexed Korea, generating no response from the European powers. Japan then continued to expand militarily.

Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War also dashed the then prevailing notion that Caucasians were military superior to Asians. Japan’s feat also gave hope to the colonized peoples of Southeast Asia (e.g. Vietnamese, Indonesians, Filipinos, etc) who were aspiring for independence from their European and American colonial masters. (For more information on the war, click here

May 14, 2020

May 14, 1980 – Salvadoran Civil War: Salvadoran government forces perpetrate the Sumpul River Massacre

On May 14, 1980, units of the Salvadoran Armed Forces and pro-government militias killed some 300-600 civilians believed to be supporters or sympathizers of the outlawed Marxist insurgent group, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). The FMLN had as its objectives the overthrow of the government through armed revolution and formation of a communist regime. The site of the massacre was the Sumpul River that separates El Salvador with neighboring Honduras. The civilians were fleeing from the advancing Salvadoran army by crossing the Sumpul into Honduras but were deterred by the presence of Honduran troops on the other side of the river. In the immediate aftermath, both the Salvadoran and Honduran governments denied that the incident took place.

The massacre was one of many such incidents (e.g. the El Mozote Massacre (800-1,200 dead) in December 1981; El Calabozo Massacre (over 200 dead) in August 1982) that took place during the Salvadoran Civil War (1980-1992), a Cold War conflict between the pro-West Salvadoran government and the local Marxist rebel group, the FMLN. The war was resolved following the end of the Cold War when in January 1992 the government and the FMLN signed a peace treaty. With regards to the Sumpul River Massacre, in April 1993, the United Nations published its “Report of the UN Truth Commission on El Salvador”, finding that there was “substantial evidence” that Salvadoran forces “massacred no less than 300 unarmed civilians” and that “the massacre was made possible by the cooperation of the Honduran armed forces.” It noted that “Salvadorian military authorities were guilty of a cover-up of the incident”, and described the massacre as “a serious violation of international humanitarian law and international human rights law”.

The peace agreement also established a fact-finding body, the United Nations Commission on the Truth for El Salvador (“Truth Commission”), to investigate “serious acts of violence…and whose impact on society urgently demands that the public should know” and make recommendations. Some 30,000 written and oral complaints of human rights violations were received and processed by the Truth Commission, which released its report on March 15, 1993. The report implicated the Salvadoran military

and state security forces in 95% of all the human rights cases filed, while the FMLN was named in 5% of these cases.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), the human rights branch of the Organization of American States (OAS), in its ruling

in October 2012 regarding the El Mozote Massacre, has stated that El Salvador’s amnesty law must not violate international laws; as such, the IACHR has asked the Salvadoran government to investigate the El Mozote Massacre. Earlier in December 2011, President Mauricio Funes (of the FMLN Party) issued, in behalf of the government, a public apology to El Mozote residents in a town ceremony.

The war had enormous repercussions on the population. Some 75,000 civilians (mostly peasants) were killed; 20,000 rebels and 7,000 government soldiers also lost their lives. About one million of the country’s total population of six million people lost their homes and became internally displaced. Tens of thousands fled to nearby countries, such as Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Mexico. About one million entered as refugees in western democratic countries in Europe and North America, with most eventually settling in the United States.

(The “Farabundo Marti” in FMLN was the name of a Salvadoran Marxist-Leninist revolutionary who in 1932 led a failed peasant uprising in El Salvador’s western provinces. Government forces captured and executed Marti and then carried out a campaign of extermination against the Pipil indigenous population, whom they believed were communist supporters of the uprising that was aimed at overthrowing the government. Some 30,000 Pipil civilians were killed in the military repression.)

May 13, 2020

May 13, 1940 – World War II: Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands flees to Britain after the German invasion

On May 13, 1940, with Dutch military resistance faltering from the German onslaught, Queen Wilhelmina and her court, together with the Dutch government, were evacuated by a British Royal Navy ship to Britain, where they established a Dutch government-in-exile that functioned for the rest of the war.

At various times in the development of Fall Gelb (the planned German invasion of Western Europe), the Netherlands or only part of it was considered, since the Germans planned that their main thrust would be through Belgium on the way to their final objective, France. However, the Germans (as did the Allies) saw the western part of the Netherlands as the northern end of a battle line if war would break out, and which therefore had to be defended against a potential flanking maneuver by the enemy. For Germany, especially Luftwaffe head Hermann Goering, the air bases in the Netherlands could be used to launch bombing raids on Britain, much the same way that the British, if they captured the Netherlands, could use these bases to attack Germany.

In World War I, the Dutch policy of neutrality had been respected by the belligerents, and the Netherlands was not invaded. As a result, with increasing tensions in Europe during the 1930s and even after war broke out in September 1939, the

Dutch continued to hope that their country would be spared the horror and destruction that their neighboring countries had suffered in the Great War.

Battle of the Netherlands

The Netherlands was not militarily prepared for war, and only began to upgrade its World War I-era war capability in 1936, belatedly after nearby countries Germany, France, and even Belgium

were already spending large amounts of money on their respective armed forces. With war looming by the late 1930s, the Netherlands had great difficulty purchasing weapons, as deliveries from Germany were deliberately stalled by the Nazi government, and the Allies, particularly France, refused to sell weapons

without the Netherlands first joining the Allies.

Hitler was fully aware of Dutch unpreparedness for war, and predicted that the Netherlands would fall in 3-5 days. Thus, for the attack on the Netherlands,

the Germans assembled its weakest force, the 18th Army, among all the forces involved in Fall Gelb. An important component were the airborne assault units (paratroopers and airborne infantry) which were assigned to seize key sites inside Fortress Holland, and capture Dutch Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government at The Hague in order to force Dutch surrender within one day.

On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands, which formed part of Fall Gelb, the simultaneous coordinated German offensives into France and the two other Low Countries, Belgium

and Luxembourg. The Germans crossed the border into the Netherlands along two points: German 18th Army at Gennep and German 6th Army at Maastricht. German 6th Army, which was the more powerful, was not assigned to the conquest of the Netherlands, but instead proceeded from Maastricht across the border into Belgium, its real target.

The airborne operations, which highlighted the German aim to quickly force Dutch surrender, was launched also on May 10, with paratrooper and glider infantry units penetrating Fortress Holland by seizing the bridges at Moerdijk, Dordrecht, and Rotterdam, and the Waalhaven airfield near Rotterdam and the three airfields (Ypenburg, Ockenburg and Valkenburg) near The Hague. The Dutch offered stiff resistance

at The Hague that broke off the German attack. Dutch forces then recaptured the three airfields and inflicted heavy losses on the Germans, including over 2,500 killed, wounded, or captured, and 175 air

transports destroyed or damaged.

On May 14, the commander of German forces at the Rotterdam front demanded that the Dutch defenders in the city lay down their weapons and surrender themselves and the city, or face an all-out German infantry, armored, and air assault. Negotiations followed, and as a second German ultimatum was being delivered following the Dutch returning the first ultimatum because of a technicality, German bombers appeared on the sky

above Rotterdam.

By this time in Berlin, Hitler chafed by what he saw was the slow progress to bring about Dutch

surrender, and as a result, the Luftwaffe sent 90 heavy bombers to bombard the Rotterdam. In the

bombing, called the “Rotterdam Blitz”, a large section of the city was destroyed, causing 900 persons killed, 85,000 homeless, and the loss of 25,000 houses, 3,000 buildings, and dozens of churches and schools. Immediately thereafter, the Dutch forces at Rotterdam surrendered, and the Germans entered the city. The Rotterdam bombing had a devastating effect on Dutch morale: when the Wehrmacht threatened the cities of Utrecht and Amsterdam with a similar fate, the Dutch high command gave up the struggle, and on May 15, 1940, the Netherlands surrendered.

Fighting continued until May 19, when the Germans expelled French forces still fighting in Zeeland Province in the extreme southwest. The German 18th Army thereafter joined the invasion of Belgium, providing the northern flank of the German advance there.