Daniel Orr's Blog, page 101

April 12, 2020

April 12, 1975 – Cambodian Civil War: U.S. diplomatic personnel flee Phnom Penh

On April 12, 1975, the U.S. government, deciding Cambodia was lost, evacuated its embassy personnel in Phnom Penh. Under Operation Eagle Pull, U.S. helicopters pulled out 82 American diplomatic staff and their families, 159 high-ranking Cambodian

civilian and military officials, and 35 nationals from other countries. Many other high-ranking Cambodian officials declined U.S. offers to leave, despite their names being on the Khmer Rouge’s death list – they were promptly executed after the city’s fall.

Cambodia and other present-day countries of Southeast Asia.

(Taken from Cambodian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath

On April 15, 1975, the remaining Cambodian Army positions west of the city fell. The following day, a government appeal for peace talks to Sihanouk (who was in Beijing) was rejected by Sihanouk. In any case, Sihanouk knew that he was powerless to stop the Khmer Rouge, which held the real power.

On April 17, 1975, the new Cambodian military-led government tried to fly out of the city to move the seat of government in the northwest region, but this attempt failed and the leaders were arrested by the Khmer Rouge. Also on April 17, 1975, Khmer

Rouge forces entered the capital, meeting no resistance as they spread out and took control of the city, with the Cambodian military ordering its troops to lay down their weapons. The war was over.

The Khmer Rouge was determined to impose a radical form of communism to Cambodia, and turn the country’s capitalist society into a classless state of

peasants. Within a few hours after seizing Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge forced all residents – some 2.5 million – to leave their homes, and walk long distances to newly established agrarian communes in the countryside. There, they were to begin their new lives as peasant laborers. Similar forced evacuations and marches took place in all towns and cities across the country. Within a short time, the country’s entire population of eight million people became peasant workers. Nobody was spared, even hospitals were emptied and the sick and elderly were forced to move to the countryside. In the process, tens of thousands perished from exhaustion, hunger, diseases, summary executions, and exposure to the elements.

From 1975 to 1978, the Khmer Rouge, which was known to the people simply by the cryptic (and highly feared) name “Angkar” (‘the organization’) and whose highest leaders were not known to the general population, ruled Cambodia as an anonymous but all-powerful, one party communist state called Democratic Kampuchea.

The Khmer Rouge regarded all forms of Western influences as capitalist, and thus were abolished.

Schools, banks, hospitals, and nearly all industries were closed down, and all economic activity was placed under strict state control. The Khmer Rouge implemented policies to eradicate Cambodian traditional life – religion, though not officially banned,

was suppressed, and thousands of Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians were killed. Families and social life were regulated under communal administration, with marital relations controlled, sexes separated, and children placed under state care.

Living conditions under the Khmer Rouge were extremely harsh. Food, medicine, and other basic

necessities were lacking or absent. Government policies targeted the former city dwellers (the so-called “New People”), and glorified the peasant villagers (the “Old People”). Government repression against perced enemies of the state led to the catastrophe known as the Cambodian Genocide (next

article), where the Khmer Rouge caused the deaths of 1½ – 2 million people (25% of the Cambodian population) as a result of executions, starvation, disease, exposure to the elements, and other causes.

April 11, 2020

April 11, 1951 – Korean War: U.S. President Truman relieves General MacArthur of his command in Korea

On April 11, 1951, in a nationwide broadcast, President Harry Truman relieved General Douglas MacArthur of his command in Korea, stating that a crucial objective of U.S. government policy in the Korean conflict was to avoid an escalation of hostilities which potentially could trigger World War III, and that “a number of events have made it evident that General MacArthur did not agree with that policy.” General MacArthur had openly advocated an escalation of the war, including directly attacking China, involving forces from Nationalist China (Taiwan), and using nuclear weapons.

General Ridgway, Eighth U.S. Army commander, was named to succeed as Supreme UN and U.S. Commander in Korea. Unlike his predecessor who desired nothing short of total victory, General Ridgway favored a limited war and accepted a

divided Korea, and thus worked closely with the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Truman administration.

North Korea and South Korea in East Asia.

(Excerpts taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background

During World War II, the Allied Powers met many times to decide the disposition of Japanese territorial holdings after the Allies had achieved victory. With regards to Korea, at the Cairo Conference held in November 1943, the United States, Britain, and Nationalist China agreed that “in due course, Korea shall become free and independent”. Then at the Yalta Conference of February 1945, the Soviet Union

promised to enter the war in the Asia-Pacific in two or three months after the European theater of World War II ended.

Then with the Soviet Army invading northern Korea on August 9, 1945, the United States became concerned that the Soviet Union might well occupy the whole Korean Peninsula. The U.S. government, acting on a hastily prepared U.S. military plan to divide Korea at the 38th parallel, presented the proposal to the Soviet government, which the latter accepted.

The Soviet Army continued moving south and stopped at the 38th parallel on August 16, 1945. U.S. forces soon arrived in southern Korea and advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8, 1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S. and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in their respective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commands established military rule in their occupation zones.

As both the U.S. and Soviet governments wanted to reunify Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December 1945, the Allied Powers agreed to form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China) five-year trusteeship over Korea. During the five-year period, a U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission would work out the process of forming a Korean government. But after a series of meetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve

anything. In September 1947, the U.S. government referred the Korean question to the United Nations (UN). The reasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission’s failure to agree to a mutually acceptable Korean government are three-fold and

to some extent all interrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed U.S.-Soviet trusteeship; the struggle for power among the various ideology-based political factions; and most important, the emerging Cold War confrontation between the United States

and the Soviet Union.

Historically, Korea for many centuries had been a politically and ethnically integrated state, although its independence often was interrupted by the invasions by its powerful neighbors, China and Japan. Because of this protracted independence, in the immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, and viewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run their own affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’s political climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, from right-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashed with each other for political power. As a result of Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were the unrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and a communist-allied anti-Japanese

partisan militia led by Kim Il-sung. Both men would play major roles in the Korean War. At the same time, tens of thousands of Koreans took part in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese

Civil War, joining and fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces, or for Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japanese resistance movement, which operated mainly out of Manchuria, was divided along ideological lines. Some groups advocated

Western-style capitalist democracy, while others espoused Soviet communism. However, all were strongly anti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria, China, and Korea.

On their arrival in the southern Korean zone in September 1948, U.S. forces imposed direct rule through the United States Army Military Government

In Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members of the Korean Communist Party in Seoul (the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeated

Japanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Korean peninsula. Then two days before U.S. forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee”

proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under the auspices of a U.S. military agent, Syngman Rhee, the former president of the “Provisional Government of the Republic

of Korea” arrived in Seoul. The USAMGIK refused to recognize the communist Korean People’s Republic,

as well as the pro-West “Provisional Government”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form a political coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S. sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. However, this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wing and right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S. authorities’ breaking up the communists’ “people’s committees” violence broke out in the southern zone during the last months of 1946. Called the Autumn Uprising, the unrest was carried out by left-aligned workers, farmers, and students, leading to many deaths through killings, violent confrontations, strikes, etc. Although in many cases, the violence resulted from non-political motives (such as targeting Japanese collaborators or settling old scores), American authorities believed that the unrest was part of a communist plot. They therefore declared martial law in the southern zone. Following the U.S. military’s crackdown on leftist activities, the communist militants went into hiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would play a role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, Soviet commanders initially worked to form a local administration under a coalition of nationalists,

Marxists, and even Christian politicians. But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who also was a Soviet Red Army officer, quickly became favored by Soviet authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’s Committee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by Kim Il-sung who soon consolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christian leaders), and nationalized industries, and launched centrally planned economic and reconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model emphasizing heavy

industry.

By 1947, the Cold War had begun: the Soviet Union tightened its hold on the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United States announced a new foreign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed at stopping the spread of communism. The United States also implemented the Marshall Plan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which was condemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed at

dividing Europe. As a result, Europe became divided into the capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting these developments, in Korea by mid-1945, the United States became resigned to the likelihood that the temporary military partition of the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel would become a permanent division along ideological grounds. In September 1947, with U.S. Congress rejecting a proposed aid package to Korea, the U.S. government turned over the Korean issue to the UN. In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’s sovereignty and called for elections throughout the Korean peninsula, which was to be overseen by a newly formed body, the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Soviet government rejected the UNGA resolution, stating that the UN had no jurisdiction over the Korean issue, and prevented

UNTCOK representatives from entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were held only in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experienced widespread violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, a

legislative body. Two months later (in July 1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitution which established a presidential form of government. Syngman Rhee, whose party won the most number of legislative seats, was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southerners proclaimed the birth of the Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as South Korea), ostensibly with the state’s sovereignty covering the whole Korean Peninsula.

A consequence of the South Korean elections was the displacement of the political moderates, because of their opposition to both the elections and the division of Korea. By contrast, the hard-line anti-communist Syngman Rhee was willing to allow the (temporary) partition of the peninsula. Subsequently, the United States moved to support the Rhee regime, turning its back on the political moderates whom USAMGIK had backed initially.

Meanwhile in the Soviet-controlled northern zone, on August 25, 1948, parliamentary elections were held to the Supreme National Assembly. Two weeks later (on September 9, 1948), the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as North Korea) was proclaimed, with Kim Il-Sung as (its first) Prime Minister. As with South Korea, North Korea declared its sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula

The formation of two opposing rival states in Korea, each determined to be the sole authority, now set the stage for the coming war. In December 1948, acting on a report by UNTCOK, the UN declared that the Republic of Korea (South Korea) was the legitimate Korean polity, a decision that was rejected by both the Soviet Union and North Korea. Also in December 1948, the Soviet Union withdrew its forces from North Korea. In June 1949, the United States

withdrew its forces from South Korea. However, Soviet and American military advisors remained, in the North and South, respectively.

In March 1949, on a visit to Moscow, Kim Il-sung asked Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, for military assistance for a North Korean planned invasion of South Korea. Kim Il-sung explained that an invasion would be successful, since most South Koreans opposed the Rhee regime, and that the communist insurgency in the south had sufficiently weakened the South Korean military. Stalin did not give his consent, as the Soviet government currently was pressed by other Cold War events in Europe.

However, by early 1950, the Cold War situation had been altered dramatically. In September 1949,

the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, ending the United States’ monopoly on nuclear

weapons. In October 1949, Chinese communists, led by Mao Zedong, defeated the West-aligned Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek in the Chinese Civil War, and proclaimed the People’s

Republic of China, a socialist state. Then in 1950, Vietnamese communists (called Viet Minh) turned the First Indochina War from an anti-colonial war against France into a Cold War conflict involving the Soviet Union, China, and the United States. In February 1950, the Soviet Union and China signed the Sino-Soviet Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance Treaty, where the Soviet government would provide military and financial aid to China.

Furthermore, the Soviet government, long wanting to gauge American strategic designs in Asia, was encouraged by two recent developments: First, the U.S. government did not intervene in the Chinese Civil War; and second, in January 1949, the United States announced that South Korea was not part of

the U.S. “defensive perimeter” in Asia, and U.S. Congress rejected an aid package to South Korea. To Stalin, the United States was resigned to the whole northeast Asian mainland falling to communism.

In April 1950, the Soviet Union approved North Korea’s plan to invade South Korea, but subject to two crucial conditions: Soviet forces would not be involved in the fighting, and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA, i.e. the Chinese armed forces) must agree to intervene in the war if necessary. In May 1950, in a meeting between Kim Il-sung and Mao Zedong, the Chinese leader expressed concern that the United States might intervene if the North Koreans attacked South Korea. In the end, Mao agreed to send Chinese forces if North Korea was invaded. North Korea then hastened its invasion plan.

The North Korean armed forces (officially: the Korean People’s Army), having been organized into its present form concurrent with the rise of Kim Il-sung, had grown in strength with large Soviet support. And in 1949-1950, with Kim Il-sung emphasizing a massive military buildup, by the eve of the invasion, North Korean forces boasted some 150,000–200,000 soldiers, 280 tanks, 200 artillery pieces, and 200 planes.

By contrast, the South Korean military (officially: Republic of Korea Armed Forces), which consisted

largely of police units, was unprepared for war. The United States, not wanting a Korean war, held back from delivering weapons to South Korea, particularly since President Rhee had declared his intention to invade North Korea in order to reunify the peninsula. By the time of the North Korean invasion, South Korean weapons, which the United States had limited to defensive strength, proved grossly inadequate. South Korea had 100,000 soldiers (of whom only 65,000 were combat troops); it also had no tanks and possessed only small-caliber artillery pieces and an assortment of liaison and trainer aircraft.

North Korea had envisioned its invasion as a concentration of forces along the Ongjin Peninsula. North Korean forces would make a swift assault on Seoul to surround and destroy the South Korean forces there. Rhee’s government then would collapse, leading to the fall of South Korea. Then on June 21, 1950, four days before the scheduled invasion, Kim Il-sung believed that South Korea had become aware of the invasion plan and had fortified its defenses. He revised his plan for an offensive all across the 38th parallel. In the months preceding the war, numerous border skirmishes had begun breaking out between the two sides.

April 10, 2020

April 10, 1979 – Uganda-Tanzania War: Tanzanian forces capture Kampala

On April 10, 1979, the Tanzanian Army entered and occupied Kampala, Uganda’s capital, practically ending the Uganda-Tanzania War except for some small-scale fighting that would continue for the next few months. Ugandan leader, General Idi Amin, earlier had fled into exile, first to Libya, and then Saudi Arabia, where he was welcomed as a guest by his friend, King Faisal I. General Amin would live in Saudi Arabia until his death in 2003.

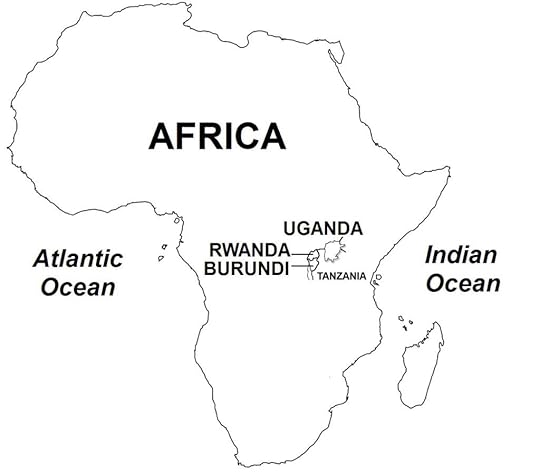

Uganda, Tanzania, and nearby countries.

(Taken from Uganda-Tanzania War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Military officers who had been bypassed or demoted from their positions became disgruntled. Many of these officers, including thousands of soldiers, crossed the border to Tanzania and met up with ex-President Obote and other exiled Ugandan leaders. Together, they formed an armed rebel group

whose aim was to overthrow General Amin. The rebels were well received by the Tanzanian government, which provided them with military and financial support.

In 1972, the rebels launched an attack in southern Uganda and came to within the town of Masaka where they tried to incite the local population to revolt against the Ugandan government. No revolt took place, however. General Amin sent his forces to Masaka, and in the fighting that followed, the rebels were thrown back across the border.

Ugandan planes pursued the rebels in northern Tanzania, but attacked the Tanzanian towns of Bukoba and Mwanza, causing some destruction. The Tanzanian government filed a diplomatic protest and increased its forces in northern Tanzania. Tensions rose between the two countries. Through mediation efforts of Somalia, however, war was averted and the two countries agreed to deescalate the tension, and withdrew their forces a distance of ten kilometers from their common border.

The insurgency provoked General Amin into intensifying his suppressive policies, especially against the ethnic groups of his political enemies. All social classes from these rival ethnicities were targeted, from businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and the clergy, to workers, peasants, and villagers. Even members of General Amin’s Cabinet and top military officers were not spared. General Amin’s secret police, called the State Research Bureau, carried out numerous summary executions and forced disappearances, as well as tortures and arbitrary

arrests. During General Amin’s eight-year reign in power, an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Ugandans were killed.

General Amin also expelled the ethnic South Asian community from Uganda. These South Asian Ugandans were the descendants of contract workers from the Indian subcontinent who had been brought to Uganda during the British colonial period. South Asians comprised only 1% of the total population but were predominantly merchants, traders, landowners, and industrialists who held a disproportionately large share of Uganda’s economy; other South Asians were wealthy professionals, held clerical jobs, or were tradesmen.

After the expulsion, the South Asians’ businesses and properties were seized by the government and distributed to the general population in line with General Amin’s program of promoting the social and

economic advancement of black Ugandans. However, many of the assets ended up being owned by General Amin’s military and political associates, most of whom had no knowledge of running a business. Soon, most of these operations failed and closed down.

As a result, Uganda’s economy deteriorated. Poverty and unemployment soared, and basic commodities became non-existent or in very low

supply. Coffee beans, the country’s main export product, were required by law to be sold to the government. But as the government failed to pay or

underpaid the farmers, the smuggling of coffee beans to nearby Kenya (where prices were much higher) became widespread and carried out by farmers and traders at the risk of a government-issued shoot-to-kill order against violators. Eventually, however, coffee bean smuggling operations came under the control of the army commanders themselves.

Initially, the Western media was fascinated by General Amin’s idiosyncratic behavior and outrageous statements, making the Ugandan leader extremely popular in foreign news reports. But as his brutal regime and human rights record became known, Britain and the United States, both Uganda’s traditional allies, distanced themselves and ended diplomatic relations with General Amin’s government. Uganda then turned to the Soviet Union, which soon became the Ugandan government’s main supplier of weapons. Uganda

also strengthened military ties with Libya and diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia.

By 1978, Uganda had become isolated diplomatically from much of the international

community. Despite outward appearances, the government was experiencing growing dissent from within. A year earlier, General Amin was nearly

ousted in a coup carried out by high-ranking government officials, underscoring the growing political opposition to his rule.

Then in November 1978, Uganda’s Vice-President, Mustafa Adrisi, was wounded in a car accident, which might have been an assassination

attempt on his life. Adrisi’s military supporters, which included some elite units, broke out in mutiny.

April 9, 2020

April 9, 1948 – Colombian politician Jorge Eliécer Gaitán is assassinated, inciting riots in Bogota and the extremely violent civil war called “La Violencia” in the countryside

On April 9, 1948, Colombian politician Jorge Eliécer Gaitán was killed in Bogota, the country’s capital, by a lone gunman in apparently non-politically motivated but confusing circumstances. Gaitán’s

assassination led to the event known as “El Bogotazo”, where the capital was thrown into chaos, as angry mobs descended on the streets and wreaked havoc all across the city. Scores of buildings, business establishments, and homes were destroyed and looted, and fires broke out and engulfed large areas. Rioters broke into police stations and seized firearms. Appeals for calm by Conservative and Liberal leaders failed to stop the violence. As a result, the army was called in that violently dispersed the mobs and succeeded in restoring order the following day. Some 3,000 to 5,000 people were killed in the chaos.

El Bogotazo led to greater violence in the countryside, producing an extremely violent civil war known as “La Violencia” that was carried out between armed groups aligned with the rival political parties.

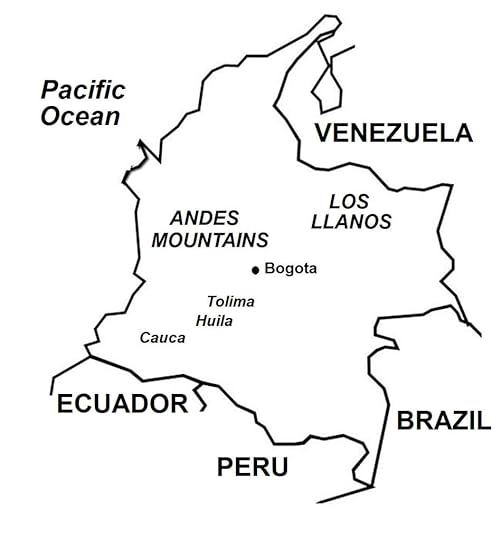

Colombia and nearby countries in South America.

(Taken from La Violencia – Wars of the 20th Century – 26 Wars in the Americas and the Caribbean)

Background

In national elections held in May 1946, Mariano Ospina of the Conservative Party became Colombia’s

president. Ospina garnered only 41% of the votes, however, while his two rival candidates of the Liberal Party gained a combined majority, but had split the Liberal votes. Furthermore, President Ospina was faced with a Liberal-controlled parliament. He therefore acquiesced to share political power, appointing a number of Liberal politicians to form a coalition government.

Conservative Party members also took over government positions at the provincial, municipal, and village levels, but encountered some resistance from defeated Liberal incumbents who, however, eventually ceded power. Post-election transitions of

government were precarious affairs in Colombia, which almost always led to some form of violence.

Colombia was a practicing democracy, but its two political parties advocated significantly different approaches on how the government should function. Conservatives, consisting of the wealthy elite, promoted a strong centralized government, greater union between church and state, and retention of the ruling oligarchy’s control of the political and economic systems. Liberals also mostly consisted of the upper class, but advocated a decentralized government, lesser union between church and state, and greater socio-economic concessions to the

general population.

The two parties had their adherents among the lower classes in the largely rural population that existed at that time. Each side’s rural followers remained unwaveringly faithful to their respective parties, were born as members of that party, vowed

lifetime devotion to that party, and passed on party membership to their offspring. The followers of both sides often lived in the same towns and villages, but were segregated by party affiliation and did not fully integrate and associate with their political rivals.

The two parties had in the past ruled long, unbroken periods under successive governments: first, as a federated state under the Liberals for 24 years (1861-1885); and then as a republic, first by the Conservatives for 44 years (1886-1930), and Liberals for 16 years (1930-1946). These long tenures allowed the ruling party to become entrenched in power, which exacerbated the transition when its rival prevailed electorally and tried to take office.

Tensions persisted, which often broke out in civil wars, the most devastating being the Thousand Days’ War (previous article).

Such was the confrontational past when President Ospina came to office. His coalition government failed to quell the rural unrest, as Liberal peasants began to organize into armed militias to confront police units, now controlled by Conservatives, as well as Conservative armed groups, which also had been formed. Two events further compromised President Ospina’s hold on his shaky coalition government. First, the Liberals won parliamentary elections in 1947, and second, popular support surged for Liberal politician Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, who emerged as his party’s candidate for the upcoming 1950 presidential elections. Gaitán was

extremely popular with the masses, and his promises to implement pro-poor social and economic reforms drew massive crowds to his rallies.

However, on April 9, 1948, Gaitán was killed in Bogota, the country’s capital, by a lone gunman in apparently non-politically motivated but confusing

circumstances. Gaitán’s assassination led to the event known as “El Bogotazo”, where the capital was thrown into chaos, as angry mobs descended on the streets and wreaked havoc all across the city. Scores of buildings, business establishments, and homes were destroyed and looted, and fires broke out and

engulfed large areas. Rioters broke into police stations and seized firearms. Appeals for calm by Conservative and Liberal leaders failed to stop the

violence. As a result, the army was called in that violently dispersed the mobs and succeeded in restoring order the following day. Some 3,000 to 5,000 people were killed in the chaos.

At the time of the violence, Bogota was hosting the Pan-American Conference attended by representatives from all countries of the Western Hemisphere, a forum that eventually established the Organization of American States (OAS). The United

States representative to the forum, Secretary of State

George Marshall, was appalled at the violence and expressed his belief that local communists had initiated the unrest, a supposition that was bolstered

since communist elements in Bogota, carrying out broadcasts over an opposition-aligned radio station, were calling on the people to take up arms in rebellion. Taken in the context of the Cold War, which had began a year earlier, the United States was concerned about and was determined to prevent a

Soviet-influenced presence in the Western Hemisphere. As events progressed in Colombia, however, the United States changed its position about El Bogotazo, later declaring that the outbreak of violence was not communist-led or -inspired.

War

El Bogotazo led to greater violence in the countryside, producing an extremely violent civil war known as “La Violencia” that was carried out between armed groups aligned with the rival political parties.

The aftermath of the 1946 elections already had produced tensions and some rural violence, particularly after Conservative peasants, with the support of the police, tried to seize farmlands belonging to Liberal farmers. El Bogotazo, however, raised partisan hostility to an uncontrolled level of hatred, as both sides now sought the total destruction of the other.

Armed bands arrived in rival villages, settlements, and isolated houses and used machetes, blades, and farm implements to carry out mass killings. In all cases, men were targeted for slaughter, although sometimes women and children were killed as well. Prior warnings in the form of rumors or threats often reached the victims before the crimes were carried out.

April 8, 2020

April 8, 1960 – The Netherlands and West Germany sign a Treaty of Settlement where German territory annexed after World War II would be returned in exchange for monetary compensation

On April 8, 1960, The Netherlands and West Germany signed an agreement whereby German lands annexed by the Netherlands after World War II

would be returned to Germany in exchange for the latter paying the former 280 million German marks as compensation for the returned lands.

In October 1945 after World War II had ended, the Netherlands asked Germany for 25 billion guilders in reparation, but retracted this as the Allies had previously agreed that no monetary reparations would be paid. The Dutch government then turned to considering a number of options for territorial compensation, the most aggressive version being annexing a sizable area of German lands, including the cities of Cologne, Aachen, Münster and Osnabrück. In the face of Allied rejection of the plan, the Netherlands agreed to just 69 km2 of German territory as war reparation.

In March 1957, the two sides started negotiations for the return of the lands. An agreement was reached on April 8, 1960. In August 1963, the lands were returned, except for one small hill (about 3 km2) called Duivelsberg/Wylerberg near Wyler village.

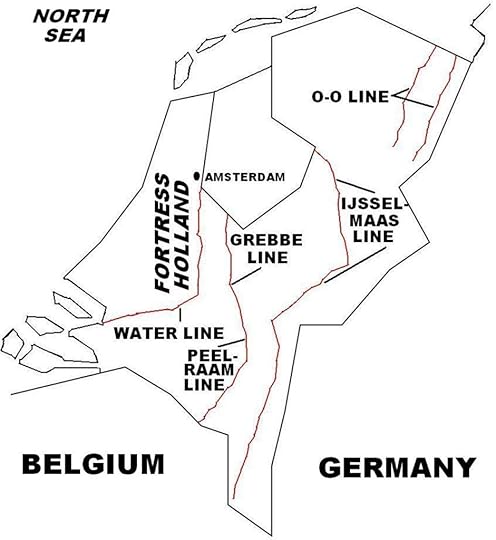

The Netherlands’ defensive positions.

(Taken from Battle of the Netherlands – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Background

In February 1940, the German High Command completed the final version of Fall Gelb (English: “Case Yellow”), the invasion of France and Low Countries (previous article), which included the capture of the Netherlands. At various times in the development of Fall Gelb, the Netherlands or only part of it was considered, since the Germans planned that their main thrust would be through Belgium on the way to their final objective, France. However, the Germans (as did the Allies) saw the western part of the Netherlands as the northern end of a battle line if war would break out, and which therefore had to be defended against a potential flanking maneuver by the enemy. For Germany, especially Luftwaffe head Hermann Goering, the air bases in the Netherlands

could be used to launch bombing raids on Britain,

much the same way that the British, if they captured the Netherlands, could use these bases to attack Germany.

In World War I, the Dutch policy of neutrality had been respected by the belligerents, and the Netherlands was not invaded. As a result, with increasing tensions in Europe during the 1930s and even after war broke out in September 1939, the

Dutch continued to hope that their country would be spared the horror and destruction that their neighboring countries had suffered in the Great War. Furthering this hope was that at the start of World War II, the Dutch government immediately announced its neutrality, and the Netherlands was an important trading partner of Germany, and enjoyed warm relations with Britain and France.

The Netherlands was not militarily prepared for war, and only began to upgrade its World War I-era war capability in 1936, belatedly after nearby countries Germany, France, and even Belgium

were already spending large amounts of money on their respective armed forces. With war looming by the late 1930s, the Netherlands had great difficulty purchasing weapons, as deliveries from Germany were deliberately stalled by the Nazi government, and the Allies, particularly France, refused to sell weapons without the Netherlands first joining the Allies. Also, a large portion of the Dutch military budget was directed toward constructing three modern warships for the Netherlands’ commercially important Asian colony, the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia).

The Netherlands had insufficient forces and resources to defend the whole country, and so the Dutch military high command devised a plan where, in the event of a German invasion, Dutch forces would fall back to “Fortress Holland” Dutch: Vesting Holland; Figure 9), the western region which was protected by several major rivers: the IJssel on the west, and the Maas, Waal, and Lek on the south. The western region also contained the country’s major cities, including the capital Amsterdam, the seat of government at The Hague, as well as Rotterdam, and Utrecht. Historically, Fortress Holland was defended

by a system called the Holland Water Line, where the waters from these rivers were used to flood the surrounding plains, which slowed or stopped an enemy advance. The Line was later shifted further east and reinforced with forts, and renamed the New Holland Water Line. But by World War I, the whole system was deemed obsolete and powerless against newly developed weapons, such as tanks and planes.

In 1939, the Dutch military established a new defense line east of Fortress Holland called the Grebbe Line (Figure 9), which it designated as its main defensive line where the decisive battle was to take place. In the event the Line was breached, the Dutch Army could still withdraw to the New Holland Water Line to make a last stand. Linked south of the Grebbe Line was the Peel-Raam Line, which was not strongly defended and was decided by the Dutch high command not to be held against a German attack. Further to the east, the Dutch established the IJssel-Maas Line, anchored on the IJssel and Maas rivers, which was manned with frontier units which would sound the alarm of a German crossing across the border. All these defensive lines were reinforced with pillboxes and casemates, which were deemed inadequate even by the Dutch high command.

Despite its neutrality, the Netherlands became increasingly alarmed by a belligerent Germany, particularly with the German conquest of neutral Denmark and Norway. The Dutch government secretly met with military officials of France, Britain, and Belgium to work out a common strategy. Talks

between the Dutch and Belgians faltered, as the two sides had formulated their own defensive strategic lines, and were insistent that the other side extend

their positions to their own lines. In the end, France agreed to fill the gap between the Belgian and Dutch lines by occupying Breda (near the Dutch-Belgian border) and linking its forces with Fortress Holland to the north. As both the Netherlands and Belgium forbid the French Army from entering their territories without first the Germans violating their neutrality, the French High Command assigned their highly mobile motorized and armored units to quickly advance to southeast Holland once the Germans attacked.

France and Britain long wanted the Low Countries to join the Allies, but their repeated prodding was turned down. The Allies feared the possibility that the Netherlands, which was not in the main route of the German invasion through Belgium,

would not strongly resist or would even allow the Germans uncontested passage through Dutch territory on their way to the west. The Allied concern was merited, as the Germans had secretly asked the Dutch government to allow free passage through some Dutch territory, but which the latter refused.

Hitler was fully aware of Dutch unpreparedness for war, and predicted that the Netherlands would fall in 3-5 days. Thus, for the attack on the Netherlands,

the Germans assembled its weakest force, the 18th Army, among all the forces involved in Fall Gelb. German 18th Army consisted of seven weak infantry units. The German High Command realized that 18th Army by itself might be inadequate, and so to add speed and greater firepower to the attack, it added some elite Waffen-SS units, the 9th Panzer Division (which had 140 tanks), and most important, airborne assault units (paratroopers and airborne infantry), which were assigned to seize key sites inside Fortress Holland, and capture Dutch Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government at The Hague in order to force Dutch surrender within one day.

April 6, 2020

April 7, 1954 – First Indochina War: United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower presents his “Domino Theory” in a news conference

On February 10, 1954, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower refused direct American involvement in the First Indochina War between France and the North Vietnamese nationalist revolutionaries known as Viet Minh. He stated, “I cannot conceive of a greater tragedy for America than to get heavily involved now in an all-out war in any of those regions”. At the same time, however, he authorized the release of $385 million in military aid to France for the prosecution of the war.

The U.S. government would continue to have close involvement in the war and other events in Asia. In a news conference on April 7, 1954, President Eisenhower warned that if one country fell to communism, surrounding countries would likewise fall in a domino effect, a concept that came to be known as the Domino Theory.

Shortly after the start of the decisive Battle of Dien Bien Phu (March–May 1954) began, upon the request of France for military assistance, the United

States considered a number of options to relieve the trapped French forces. These included launching a massive aerial attack at the Viet Minh using 60 B-29

bombers and 150 fighter planes from the U.S. Seventh Fleet in the Philippines; becoming directly involved in the war by sending American troops; or even intervening with nuclear weapons. However, the United States announced that its becoming involved in the war was contingent on the support

of its other allies, particularly Britain. But as this was not forthcoming, U.S. President Eisenhower decided not to intervene.

Vietnam was effectively partitioned into separate states, North Vietnam and South Vietnam, by events following the First Indochina War.

(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath

By the time of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, France knew that it could not win the war, and turned its attention on trying to work toward a political settlement and an honorable withdrawal from Indochina. By February 1954, opinion polls at home

showed that only 8% of the French population supported the war. However, the Dien Bien Phu debacle dashed French hopes of negotiating under favorable withdrawal terms. On May 8, 1954, one

day after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, representatives from the major powers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochina states: Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and State of Vietnam, met at Geneva (the Geneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina. The Conference also was envisioned to resolve the crisis in the Korean Peninsula in the aftermath of the Korean War (separate article), where deliberations ended on

June 15, 1954 without any settlements made.

On the Indochina issue, on July 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by the parties. The ceasefire was agreed to by France and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17th parallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional military

demarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The French and their allies in the northern zone departed and moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh in the southern zone departed and moved to the northern zone (although some southern Viet Minh remained in the south on instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 days where Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on either side of the line. About one million northerners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upper

classes consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communist politicians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone, this mass exodus was prompted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and State of Vietnam in a massive propaganda campaign, as well as the peoples’ fears of repression under a communist regime.

In August 1954, planes of the French Air Force and hundreds of ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy (the latter under Operation Passage to Freedom) carried out the movement of Vietnamese civilians from north to south. Some 100,000 southerners, mostly Viet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, moved to the northern

zone. A peacekeeping force, called the International Control Commission and comprising contingents from India, Canada, and Poland, was tasked with enforcing the ceasefire agreement. Separate ceasefire agreements also were signed for Laos and Cambodia.

Another agreement, titled the “Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring Peace in Indo-China, July 21, 1954”, called for Vietnamese general elections to be held in July 1956, and the reunification of Vietnam. France DRV, the Soviet Union, China, and Britain signed this

Declaration. Both the State of Vietnam and the United States did not sign, the former outright rejecting the Declaration, and the latter taking a hands-off stance, but promising not to oppose or jeopardize the Declaration.

By the time of the Geneva Conference, the Viet Minh controlled a majority of Vietnam’s territory and appeared ready to deal a final defeat on the demoralized French forces. The Viet Minh’s agreeing to apparently less favorable terms (relative to its commanding battlefield position) was brought about by the following factors: First, despite Dien Bien

Phu, French forces in Indochina were far from being defeated, and still held an overwhelming numerical and firepower advantage over the Viet Minh; Second, the Soviet Union and China cautioned the Viet Minh that a continuation of the war might prompt an escalation of American military involvement in support of the French; and Third, French Prime Minister Pierre Mendes-France had vowed to achieve a ceasefire within thirty days or resign. The Soviet Union and China, fearing the collapse of the Mendes-France regime and its replacement by a right-wing government that would continue the war, pressed Ho to tone down Viet Minh insistence of a unified Vietnam under the DRV, and agree to a compromise.

The planned July 1956 reunification election failed to materialize because the parties could not agree on how it was to be implemented. The Viet Minh proposed forming “local commissions” to administer the elections, while the United States, seconded by the State of Vietnam, wanted the elections to be held under United Nations (UN)

oversight. The U.S. government’s greatest fear was

a communist victory at the polls; U.S. President Eisenhower believed that “possibly 80%” of all Vietnamese would vote for Ho if elections were held. The State of Vietnam also opposed holding the

reunification elections, stating that as it had not signed the Geneva Accords, it was not bound to participate in the reunification elections; it also

declared that under the repressive conditions in the north under communist DRV, free elections could not be held there. As a result, reunification elections were not held, and Vietnam remained divided.

In the aftermath, both the DRV in the north (later commonly known as North Vietnam) and the State of Vietnam in the south (later as the Republic of Vietnam, more commonly known as South Vietnam) became de facto separate countries, both Cold War client states, with North Vietnam backed by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, and South Vietnam supported by the United States and other Western democracies.

In April 1956, France pulled out its last troops from Vietnam; some two years earlier (June 1954), it had granted full independence to the State of Vietnam. The year 1955 saw the political consolidation and firming of Cold War alliances for both North Vietnam and South Vietnam. In the north, Ho Chi Minh’s regime launched repressive land reform and rent reduction programs, where many tens of thousands of landowners and property managers were executed, or imprisoned in labor camps. With the Soviet Union and China sending more weapons and advisors, North Vietnam firmly fell within the communist sphere of influence.

In South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, whom Bao Dai appointed as Prime Minister in June 1954, also eliminated all political dissent starting in 1955, particularly the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen in Saigon, and the religious sects Hoa Hao and Cao Dai in the Mekong Delta, all of which maintained powerful armed groups. In April-May 1955, sections of central Saigon were destroyed in street battles between government forces and the Binh Xuyen

militia.

Then in October 1955, in a referendum held to determine the State of Vietnam’s political future, voters overwhelmingly supported establishing a republic as campaigned by Diem, and rejected the restoration of the monarchy as desired by Bao Dai. Widespread irregularities marred the referendum, with an implausible 98% of voters favoring Diem’s proposal. On October 23, 1955, Diem proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam (later commonly known as South Vietnam), with himself as its first president. Its predecessor, the State of Vietnam was dissolved, and Bao Dao fell from power.

In early 1956, Diem launched military offensives on the Viet Minh and its supporters in the South Vietnamese countryside, leading to thousands being executed or imprisoned. Early on, militarily weak South Vietnam was promised armed and financial support by the United States, which hoped to prop up the regime of Prime Minister (later President) Diem, a devout Catholic and staunch anti-communist, as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia.

In January 1955, the first shipments of American weapons arrived, followed shortly by U.S. military advisors, who were tasked to provide training to the South Vietnamese Army. The U.S. government also endeavored to shore up the public image of the somewhat unknown Diem as a viable alternative

to the immensely popular Ho Chi Minh. However, the Diem regime was tainted by corruption and nepotism, and Diem himself ruled with autocratic powers, and implemented policies that favored the wealthy landowning class and Catholics at the expense of the lower peasant classes and Buddhists (the latter comprised 70% of the population).

By 1957, because of southern discontent with Diem’s policies, a communist-influenced civilian uprising had grown in South Vietnam, with many acts of terrorism, including bombings and assassinations, taking place. Then in 1959, North Vietnam, frustrated at the failure of the reunification elections from taking place, and in response to the growing insurgency in the south, announced that it was

resuming the armed struggle (now against South Vietnam and the United States) in order to liberate the south and reunify Vietnam. The stage was set for the cataclysmic Second Indochina War, more popularly known as the Vietnam War.

April 5, 2020

April 6, 1994 – The start of the Rwandan Genocide, where 800,000 to one million people are killed

On April 6, 1994, Rwanda’s President Juvenal Habyarimina and Burundi’s head of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira, were killed by undetermined assassins when their plane was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade as it was about to land in Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government took over power in Rwanda. Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the new government unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murder Tutsis and moderate Hutus on sight. Over the next several weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”, large numbers of civilians were murdered in Kigali and throughout the country. No place was safe; in some instances, even Catholic churches were the scenes of the massacres of thousands of Tutsis where they had taken refuge.

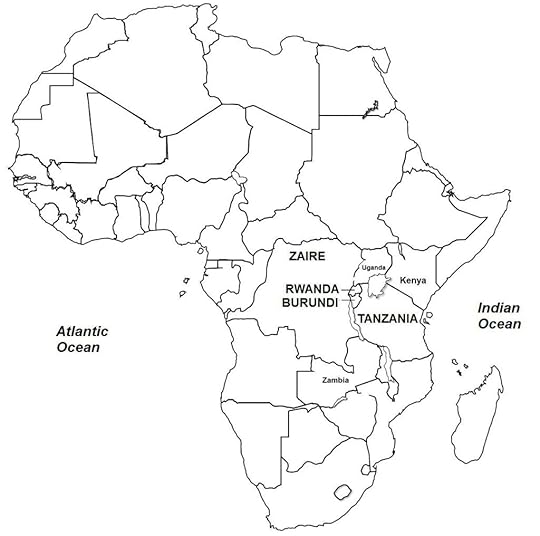

Africa showing location of Rwanda and other East African countries.

(Excerpts taken from Rwandan Civil War and Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2

Rwandan Civil War. In April 1994, the Rwandan Genocide was in full swing, with Hutus targeting Tutsis. From their bases in northern Rwanda, Tutsi rebels launched separate offensives aimed at Kibungo in the southeast, Ruhengeri in the north, and Kigali, Rwanda’s capital.

Background

Rwanda, a small country in Africa, experienced a long period of ethnic unrest before and after it gained its

independence in the 1960s. Then in the 1990s, this unrest culminated in two events known as the Rwandan Civil War and the Rwandan Genocide, both of which caused great loss in human lives and massive destruction of the country.

The conflict revolved around the hostility between Rwanda’s two main ethnic groups, the majority Hutus, who comprised 85% of the population, and the Tutsis, who made up 14% of the population. The origin of this hostility goes back many centuries to when a Tutsi monarchy was established in the Hutu-populated land of what is present-day Rwanda. Over time, the Tutsi monarch gained domination over the Hutus. The Tutsi monarch also acquired ownership over most of the land, which he divided into vast estates that were overseen by a hierarchy of Tutsi overlords, and worked by Hutu laborers in a feudal-type system. For the most part, however, Tutsis and Hutus lived in harmony. In the course of time, some Hutus became

wealthy, while many ordinary, non-aristocratic Tutsis remained poor.

Rwandan Genocide

On April 6, 1994, President Habyarimina and Burundi’s head of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira, were killed by undetermined assassins when their plane was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade as it was about to land in Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government took over power in Rwanda.

Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the new government unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murder Tutsis and

moderate Hutus on sight. Over the next several weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”, large numbers of civilians were murdered in Kigali and throughout the country. No place was

safe; in some instances, even Catholic churches were the scenes of the massacres of thousands of Tutsis where they had taken refuge.

The attackers used clubs, spears, firearms, and grenades, but their main weapon was the machete, with which they had trained extensively and which they used to hack away at their victims. At the urging of local officials, Hutu civilians joined in the killing frenzy, and turned against their Tutsi neighbors,

acquaintances, and even relatives. In many cases, the threat of being killed for appearing sympathetic to Tutsis forced many otherwise disinterested Hutus to participate.

The Rwandan Army provided the Interahamwe with a list of Tutsis to be killed, and raised road blocks to prevent any escape. The death toll in the Rwandan Genocide ranges from between 800,000 to one million; some 10% of the fatalities were moderate

Hutus. The genocide lasted for about 100 days, from between April 6 to July 15, producing a killing rate of 10,000 persons a day. The speed by which it was

carried out makes the Rwandan Genocide the fastest in history. (By comparison, the Holocaust in Europe during World War II, although producing a much

higher death toll, was carried out over a number of years.)

During the course of the genocide, the UN force in Rwanda was ordered not to intervene by the UN Secretary General. In any case, the UN force was seriously undermanned and only lightly armed to stop the widespread violence.

The UN peacekeepers, however, managed to protect the civilians inside their zone of authority.

Shortly after the violence began, foreign diplomats and their staff from the various embassies in Kigali

fled the country. Other civilian expatriates were evacuated as well. The international community, including the Western powers, chose not to intervene

in the genocide or misread the upsurge in violence as just another combat phase in the civil war.

April 4, 2020

April 5, 1982 – Falklands War: A British fleet sets out to recapture the Falklands Islands

On April 5, 1982, a fleet of 93 ships, led by two aircraft carriers, set out from Britain for the South Atlantic Ocean. On April 9 and May 12, two requisitioned commercial vessels also set sail, carrying the 15,000 British troops that would

comprise the ground forces for the land invasion. The British plan was to gain air and naval superiority before carrying out a land attack on the islands.

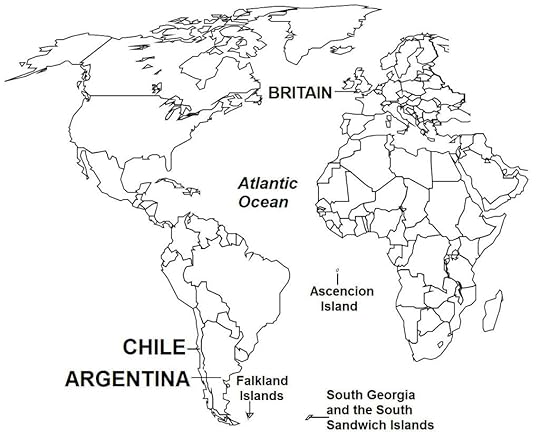

In 1982, Argentina and Britain went to war for possession of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

(Taken from Falklands War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background

In early 1982, Argentina’s ruling military junta, led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, was facing a crisis of confidence. Government corruption, human rights violations, and an economic recession had turned initial public support for the country’s military regime into widespread opposition. The pro-U.S. junta had come to power through a coup in 1976, and had crushed a leftist insurgency in the “Dirty War” by using conventional warfare, as well as “dirty” methods, including summary executions and forced disappearances. As reports of military atrocities became known, the international community exerted pressure on General Galtieri to implement reforms.

In its desire to regain the Argentinean people’s moral support and to continue in power, the military government conceived of a plan to invade the Falkland Islands, a British territory located about 700 kilometers east of the Argentine mainland. Argentina

had a long-standing historical claim to the Falklands,

which generated nationalistic sentiment among Argentineans. The Argentine government was determined to exploit that sentiment. Furthermore,

after weighing its chances for success, the junta concluded that the British government would not likely take action to protect the Falklands, as the

islands were small, barren, and too distant, being located three-quarters down the globe from Britain.

The Argentineans’ reasoning was not without merit. Britain under current Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was experiencing an economic recession, and in 1981, had made military cutbacks that would have seen the withdrawal from the Falklands of the HMS Endurance, an ice patrol vessel and the British Navy’s only permanent ship in the southern Atlantic

Ocean. Furthermore, Britain had not resisted when in 1976, Argentinean forces occupied the uninhabited Southern Thule, a group of small islands that forms a part of the British-owned South Sandwich Archipelago, located 1,500 kilometers east of the Falkland Islands.

In the sixteenth century, the Falkland Islands first came to European attention when they were signed by Portuguese ships. For three and a half centuries thereafter, the islands became settled and controlled at various times by France, Spain, Britain, the United States, and Argentina. In 1833, Britain gained uninterrupted control of the islands, establishing a permanent presence there with settlers coming mainly from Wales and Scotland.

In 1816, Argentina gained its independence and, advancing its claim to being the successor state of the former Spanish Argentinean colony that had included “Islas Malvinas” (Argentina’s name for the Falkland Islands), the Argentinean government declared that the islands were part of Argentina’s territory. Argentina also challenged Britain’s account of the events of 1833, stating that the British Navy gained control of the islands by expelling the Argentinean civilian authority and residents already present in the Falklands. Over time, Argentineans perceived the British control of the Falklands as a misplaced vestige of the colonial past, producing successive generations of Argentineans instilled with anti-imperialist sentiments. For much of the twentieth century, however, Britain and Argentina

maintained a normal, even a healthy, relationship, although the Falklands issue remained a thorn on both sides.

After World War II, Britain pursued a policy of decolonization that saw it end colonial rule in its vast territories in Asia and Africa, and the emergence of many new countries in their places. With regards to the Falklands, under United Nations (UN) encouragement, Britain and Argentina met a number of times to decide the future of the islands. Nothing substantial emerged on the issue of sovereignty, but the two sides agreed on a number of commercial ventures, including establishing air and sea links between the islands and the Argentinean mainland, and for Argentinean power firms to supply energy to the islands. Subsequently, Falklanders (Falkland residents) made it known to Britain that they wished to remain under British rule. As a result, Britain reversed its policy of decolonization in the Falklands and promised to respect the wishes of the Falklanders.

April 3, 2020

April 4, 1945 – World War II: Soviet forces expel the last German units from Hungary

In September 1944, the Soviet Red Army and its allies crossed into Hungary and by December 1944, had encircled the capital, Budapest, starting a siege of the city. In February 1945, Budapest was taken. The last German troops were expelled from Hungary in early April 1945; Soviet operations ended on April 4, 1945, although a number of small German-Hungarian units continued to resist until the end of the war. In post-war Hungary, April 4 was celebrated as Liberation Day until 1989.

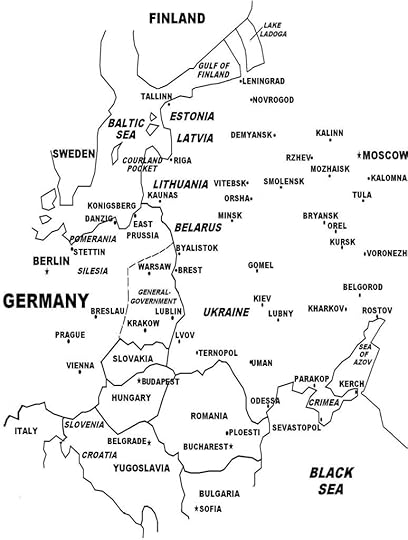

The series of massive Soviet Counter-Offensives recaptured lost Soviet territory and then swept through Eastern and Central Europe into Germany.

(Taken from Soviet Counter-Attack and Defeat of Germany – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

The Balkans and

Eastern and Central Europe

With its advance into western Ukraine in April 1944, the Red Army, specifically the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts, including the 1st and 4th Ukrainian Fronts, was poised to advance into Eastern Europe and the Balkans to knock out Germany’s Axis allies from the war. In May 1944, a Red Army offensive into Romania was stopped by a German-Romanian combined force, but a subsequent operation in August broke through, and the Soviets captured Targu Frumus and Iasi (Jassy) on August 21 and Chisinau on August 24. The Axis defeat was thorough: German 6th Army, which had been reconstituted after its destruction in Stalingrad, was

again encircled and destroyed, German 8th Army, severely mauled, withdrew to Hungary, and the Romanian Army, severely lacking modern weapons, suffered heavy casualties. On August 23, Michael I,

King of Romania, deposed the pro-Nazi government of Prime Minister Ion Antonescu and announced his acceptance of the armistice offered by Britain, the

United States, and the Soviet Union. Romania then switched sides to the Allies and declared war on Germany. The Romanian government thereafter joined the war against Germany, and allowed Soviet forces to pass through its territory to continue into Bulgaria in the south.

The rapid collapse of Axis forces in Romania led to political turmoil in Bulgaria. On August 26, 1944, the Bulgarian government declared its neutrality in the war. Bulgarians were ethnic Slavs like the Russians, and Bulgaria did not send troops to attack the Soviet Union and in fact continued to maintain diplomatic ties with Moscow during the war. However, its government was pro-German and the country was an Axis partner. On September 2, a new Bulgarian government was formed comprising the

political opposition, which did not stop the Soviet Union from declaring war on Bulgaria three days later. On September 8, Soviet forces entered Bulgaria, meeting no resistance as the Bulgarian government stood down its army. The next day, Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, was captured, and the Soviets lent their support behind the new Bulgarian government comprising communist-led resistance fighters of the Fatherland Front. Bulgaria then declared war on Germany, sending its forces in support of the Red Army’s continued advance to the west.

The Red Army now set its sights on Serbia, the

main administrative region of pre-World War II Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia itself had been dismembered by the occupying Axis powers. For Germany, the loss

of Serbia would cut off its forces’ main escape route from Greece. As a result, the German High Command

allocated more troops to Serbia and also ordered the evacuation of German forces from other Balkan regions.

Occupied Europe’s most effective resistance struggle was located in Yugoslavia. By 1944, the communist Yugoslav Partisan movement, led by Josip Broz Tito, controlled the mountain regions of Bosnia, Montenegro, and western Serbia. In late September 1944, the Soviet 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts, thrusting from Bulgaria and Romania, together with

the Bulgarian Army attacking from western Bulgaria,

launched their offensive into Serbia. The attack was aided by Yugoslav partisans that launched coordinated offensives against the Axis as well as conducting sabotage actions on German communications and logistical lines – the combined forces captured Serbia, most importantly the capital Belgrade, which fell on October 20, 1944. German

forces in the Balkans escaped via the more difficult routes through Bosnia and Croatia in October 1944. For the remainder of the war, Yugoslav partisans liberated the rest of Yugoslavia; the culmination of their long offensive was their defeat of the pro-Nazi

Ustase-led fascist government in Croatia in April-May 1945, and then their advance to neighboring Slovenia.

The succession of Red Army victories in Eastern Europe brought great alarm to the pro-Nazi government in Hungary, which was Germany’s

last European Axis partner. Then when in late September 1944, the Soviets crossed the borders from Romania and Serbia into Hungary, Miklos Horthy, the Hungarian regent and head of state, announced in mid-October that his government had signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. Hitler promptly forced Horthy, under threat, to revoke the armistice, and German troops quickly occupied the country.

The Soviet campaign in Hungary, which lasted six months, proved extremely brutal and difficult both for the Red Army and German-Hungarian forces, with fierce fighting taking place in western Hungary as the

numerical weight of the Soviets forced back the Axis. In October 1944, a major tank battle was fought at Debrecen, where the panzers of German Army Group Fretter-Pico (named after General Maximilian Fretter-Pico) beat back three Soviet tank corps of 2nd Ukrainian Front. But in late October, a powerful

Soviet offensive thrust all the way to the outskirts of Budapest, the Hungarian capital, by November 7, 1944.

Two Soviet pincer arms then advanced west in a flanking maneuver, encircling the city on December 23, 1944, and starting a 50-day siege. Fierce urban warfare then broke out at Pest, the flat eastern section of the city, and then later across the Danube River at Buda, the western hilly section, where German-Hungarian forces soon retreated. In January 1945, three attempts by German armored units to relieve the trapped garrison failed, and on February 13, 1945, Budapest fell to the Red Army. The Soviets then continued their advance across Hungary. In early March 1945, Hitler launched Operation Spring Awakening, aimed at protecting the Lake Balaton oil fields in southwestern Hungary, which was one of Germany’s last remaining sources of crude oil. Through intelligence gathering, the Soviets became aware of the plan, and foiled the offensive, and then counter-attacked, forcing the remaining German forces in Hungary to withdraw across the Austrian border.

The Germans then hastened to construct defense lines in Austria, which officially was an integral part

of Germany since the Anschluss of 1938. In early

April 1945, Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed the border from Hungary into Austria, meeting only light opposition in its advance toward Vienna. Only undermanned German forces defended the Austrian capital, which fell on April 13, 1945. Although some fierce fighting occurred, Vienna was spared the

widespread destruction suffered by Budapest

through the efforts of the anti-Nazi Austrian resistance movement, which assisted the Red Army’s entry into the city. A provisional government for Austria was set up comprising a coalition of conservatives, democrats, socialists, and communists, which gained the approval of Stalin, who earlier had planned to install a pro-Soviet government regime from exiled Austrian communists. The Red Army continued advancing across other parts of Austria,

with the Germans still holding large sections of regions in the west and south. By early May 1945, French, British, and American troops had crossed into Austria from the west, which together with the Soviets, would lead to the four-power Allied occupation (as in post-war Germany) of Austria after the war.

April 2, 2020

April 3, 1948 – The United States enacts the Marshall Plan, allocating $5 billion in aid for the reconstruction of Europe after World War II

On April 3, 1948, the United States implemented a massive assistance program, the European Recovery Plan, more commonly known as the Marshall Plan (named after U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall), where the U.S. government poured in $5 billion ($51 billion in 2017 value) in 1948 in financial aid toward European member-states of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC). In the

Marshall Plan, which lasted until the end of 1951, the United States donated $13 billion ($134 billion in 2017 value) to 18 countries, with the largest amounts given to Britain (26%), France (18%), and West Germany (11%). Other beneficiaries were Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and Trieste. After the Marshall Plan ended in 1952, another program, the Mutual Security Plan, poured in $7 billion ($63 billion in 2017 value) annual recovery assistance to Europe until 1961. By the early 1950s, Western Europe’s productivity had surpassed pre-war levels, and the region would go on to enjoy prosperity in the next two decades.

(Taken from The End of World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Post-war reconstruction and start of the Cold War

By 1947, Europe’s economic recovery was moving forward only slowly, despite the massive infusion

of American funds. Farm production was only 83% of pre-war levels, industrial output only 88%, and exports just 59%. High levels of unemployment and

food shortages caused labor strikes and social unrest. Before the war, Europe’s economy had been linked to German industries through the exchange of raw

materials and manufactured goods. In 1947, the United States decided that Germany’s participation in Europe’s economy was necessary, and the Western Allied plan to de-industrialize Germany was ended. In July 1947, the U.S. government scrapped JCS 1067, and replaced it with JCS Directive 1779, which stated that “an orderly and prosperous Europe requires the economic contribution of a stable and productive Germany”. Restrictions on German industry production were eased, and steel output was raised from 25% to 50% of pre-war capacity.

In April 1948, the United States implemented a massive assistance program, the European Recovery Plan, more commonly known as the Marshall Plan (named after U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall), where the U.S. government poured in $5 billion ($51 billion in 2017 value) in 1948 in financial aid toward European member-states of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC). In the

Marshall Plan, which lasted until the end of 1951, the United States donated $13 billion ($134 billion in 2017 value) to 18 countries, with the largest amounts given to Britain (26%), France (18%), and West Germany (11%). Other beneficiaries were Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and Trieste. After the Marshall Plan ended in 1952, another program, the Mutual Security Plan, poured in $7 billion ($63 billion in 2017 value) annual recovery assistance to Europe until 1961. By the early 1950s, Western Europe’s productivity had surpassed pre-war levels, and the region would go on to enjoy prosperity in the next two decades.

Also significant was the economic integration of Western Europe, which was promoted by the Marshall Plan and spurred on further by the formation of the International Authority of the

Ruhr (IAR) in April 1949, where the Allied Powers set limits to the German coal and steel industries. By 1952, with West Germany firmly aligned with the Western democracies, the IAR was abolished and replaced by the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which integrated the economies of France,

West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. In 1957, the ECSC was succeeded by the European Economic Community (EEC), which later led to the European Union (EU) in 1993.

The Marshall Plan had been offered to the Soviet

Union, but which Stalin rejected. The Soviet leader also strong-armed Eastern and Central European

countries under Soviet occupation not to participate, including Poland and Czechoslovakia, which had shown interest. Stalin was determined to achieve a political stranglehold on the emerging communist governments of Hungary, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Albania. Participation of these countries in the Marshall Plan would have allowed American involvement in their economies, which Stalin opposed.

Relations between the Soviet Union and the Western Powers, the United States and Britain, deteriorated during the Yalta Conference (February 1945) when victory in the war became clear, because of disagreement regarding the post-war future of Poland in particular, and Eastern and Central Europe in general. In April 1945, new U.S. President Truman announced that his government would take a firmer stance against the Soviet Union more than his predecessor, President Roosevelt. Following the end of the war, the United States, Britain, and France were wary of the continued Red Army occupation of Eastern and Central Europe, and feared that the Soviets would use them as a staging ground for the conquest of the rest of Europe and the spread of communism. In war-time Allied conferences, Stalin had demanded a sphere of political influence in Eastern and Central Europe to serve as a buffer against another potential invasion from the West. In turn, Stalin saw the presence of U.S. forces in Europe as a plot by the United States to gain control of and impose American political, economic, and social ideologies on the continent. In February 1946, Stalin announced that war was inevitable between the opposing ideologies of capitalism and communism.

George Kennan, an envoy in the U.S. diplomatic office in Moscow, then sent to the U.S. State Department the so-called “Long Telegram”, which

warned that the Soviets were unwilling to have “permanent peaceful coexistence” with the West, was bent on expansionism, and was prepared for a “deadly struggle for total destruction of rival powers”. The telegram proposed that the United States

should confront the Soviet threat by implementing firm political and economic foreign policies. Kennan’s proposed hard-line stance against the Soviet Union was eventually adopted by the Truman government.

In September 1946, in response to the “Long Telegram”, the Soviets accused the United States

of “striving for world supremacy”.

In March 1946, civil war broke out in Greece between the local communist and monarchist forces.

Also that month, Churchill delivered his “Iron Curtain” speech, where he stated that an “iron curtain” had descended across Eastern Europe, and warned of further Soviet expansionism into Europe. In reply, Stalin accused Churchill of “war mongering”.

American foreign policy in the post-war era finally took shape in March 1947 with the Truman Doctrine, which arose from a speech by President Truman before the U.S. Congress, where he stated that his

administration would “support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures”. President Truman gave reference to supporting friendly forces in the on-going Greek Civil War after the British had announced the end of their involvement in the conflict. Truman also requested U.S. Congress support for Greece’s neighbor, Turkey, which was being pressured by Stalin to grant Soviet base and transit rights through the Turkish Straits. Russian troops also continued to occupy northern Iran despite the Soviet government’s war-time promise to leave when the war ended. To the Truman administration, a communist victory in Greece, and the absorption of Turkey and Iran into the Soviet

sphere of influence would lead to Soviet expansion into the oil-rich Middle East.

The Truman Doctrine of “containing” Soviet expansionism is generally cited as the trigger for the Cold War, the ideological rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union in particular, and the forces of democracy and communism in general. By the late 1940s, with the apparent threat of imminent war looming, the Western European democracies: Britain, France, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg,

Portugal, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland, and the United States and Canada, formed a military alliance called the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

in April 1949. Then in May 1955, with the entry of West Germany into NATO and the formation of the West German Armed Forces, the alarmed Soviet Union established a rival military alliance called the Warsaw Pact (officially: Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation, and Mutual Assistance) with its socialist satellite states: East Germany, Poland, Hungary,

Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania. The stage thus was set for the ideological and military division of Europe that lasted throughout the Cold War.