Daniel Orr's Blog, page 105

March 2, 2020

March 3, 1918 – World War I: The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk is signed, which ends fighting between Russia and the Central Powers

In Soviet Russia, the Bolsheviks, whose revolution had succeeded partly on their promises to a war-weary citizenry and military to disengage from World War I, declared its pacifist intentions to the Central

Powers. A ceasefire agreement was signed on December 15, 1917 and peace talks began a few days later in Brest-Litovsk (present-day Brest, in Belarus).

However, the Central Powers imposed territorial demands that the Russian government deemed excessive. On February 17, 1918, the Central Powers repudiated the ceasefire agreement, and the following day, Germany and Austria-Hungary

restarted hostilities against Russia, launching a massive offensive with one million troops in 53 divisions along three fronts that swept through western Russia and captured Ukraine Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. German forces also entered Finland, aiding the non-socialist paramilitary group known as the “White Guards” in defeating the socialist militia known as “Red Guards” in the Finnish Civil War. Eleven days into the offensive, the northern front of the German advance was some 85 miles from the Russian capital of Petrograd (on March 12, 1918, the Russian government transferred its capital to Moscow).

On February 23, 1918, or five days into the offensive, peace talks were restarted at Brest-Litovsk, with the Central Powers demanding from Russia even greater territorial and military concessions than in the December 1917 negotiations. After heated debates

among members of the Council of People’s Commissars (the highest Russian governmental body) who were undecided whether to continue or end the war, at the urging of its Chairman, Vladimir Lenin, the Russian government acquiesced to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. On March 3, 1918, Russian and Central Powers representatives signed the treaty, whose major stipulations included the following: peace was restored between Russia and the Central Powers comprising Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire; Russia relinquished possession of Finland (which was currently embroiled in a civil war), Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic territories of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – Germany and Austria-Hungary were to determine the future of these territories; and Russia also ceded to the Ottoman Empire the regions of Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi in the Caucasus.

Subsequently, German forces occupied Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland,

establishing semi-autonomous governments in these territories that were subordinate to the authority of the German monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II. The German occupation of the region allowed the realization of the Germanic vision of “Mitteleuropa”, an expansionist ambition aimed at unifying all Germanic and non-Germanic peoples of Central Europe into a greatly enlarged and powerful German Empire. In support of Mitteleuropa, in the Baltic region, the Baltic German nobility proposed to set up the United Baltic Duchy, a semi-autonomous political entity consisting of present-day Latvia and Estonia that would be voluntarily integrated into the German Empire. The proposal was not implemented, but German military authorities set up local civil governments under the authority of the Baltic German nobility or ethnic Germans.

Although the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 ended Russia’s participation in World War I, the war was still ongoing in other fronts – most notably on the Western Front, where for four years, German forces were bogged down in inconclusive warfare against the British, French and other Allied Armies. After transferring substantial numbers of now freed troops from the Russian front to the Western Front, in March 1918, Germany launched the Spring Offensive, a major attack into France and Belgium

in an effort to bring the war to an end. After four months of fighting, by July 1918, despite achieving some territorial gains, the German offensive had ground to a halt.

The Allied Powers then counterattacked with newly developed battle tactics and weapons and gradually pushed back the now spent and demoralized German Army all across the line into German territory. The entry of the United States into the war on the Allied side was decisive, as

increasing numbers of arriving American troops with the backing of the U.S. weapons-producing industrial power contrasted sharply with the greatly depleted

war resources of both the Entente and Central Powers. The imminent collapse of the German Army was greatly exacerbated by the outbreak of political and social unrest at the home front (the German Revolution of 1918-1919), leading to the sudden end of the German monarchy with the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II on November 9, 1918 and the establishment of an interim government (under moderate socialist Friedrich Ebert), which quickly signed an armistice with the Allied Powers on

November 11, 1918 that ended the combat phase of World War I.

As the armistice agreement required that Germany demobilize the bulk of its armed forces as well as withdraw the same to the confines of the German borders within 30 days, the German government ordered its forces to abandon the occupied territories that had been won in the Eastern Front. After Germany’s capitulation, Russia repudiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and made plans to seize back the European territories it previously had lost to the Central Powers. An even far more reaching objective was for the Bolshevik government to spread the communist revolution to Europe, first by linking up with German communists who were at the forefront of the unrest that

currently was gripping Germany. Russian military planners intended the offensive to merely follow in the heels of the German withdrawal from Eastern Europe (i.e. to not directly engage the Germans

in combat) and then seize as much territory before the various local ethnic nationalist groups in these territories could establish a civilian government.

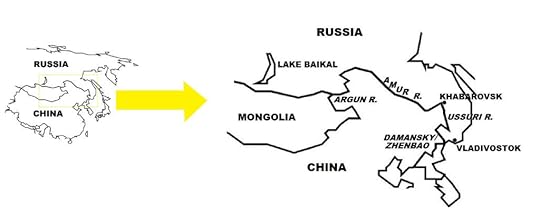

March 2, 1969 – Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Soviet and Chinese forces skirmish on Damansky/Zhenbao Island

On March 2, 1969, Soviet border troops were sent to Damansky/Zhenbao Island to expel 30 Chinese soldiers who had landed on the island. Unbeknown to the Soviets, a large Chinese force, (300 soldiers, according to the Soviets) which was hidden and waiting in ambush in the nearby forest, opened fire on the Soviets. Fighting then broke out, with other units from both sides joining the fray.

Chinese units used artillery and small arms fire from their side of the Ussuri River, while the Soviets sent reinforcements to Damansky/Zhenbao Island from their side of the river.

(Taken from Sino-Soviet Border Conflict – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

What became the trigger for the escalation of border clashes that nearly led to total war between China and the Soviet Union was the disputed but nondescript Damansky Island (Zhenbao Island to the Chinese), a small (0.74 square kilometers) 1½-mile long by ½-mile wide island located in the Ussuri River between the Soviet bank in the east and the Chinese bank in the west. By the terms of a treaty signed in the 19th century, Damansky/Zhenbao Island belonged to the Soviet Union. The island was uninhabited, and also experienced flooding from seasonal rains. Both the Chinese and Soviets regularly sent patrols to reconnoiter the island.

During border negotiations in 1964, the Soviet Union agreed to cede the island to China, but then retracted this offer when talks broke down. Thereafter, the island became a flashpoint for armed clashes. In March 1969, China accused the Soviet

Union of intruding into Damansky/Zhenbao Island sixteen times during a two-year period in January 1967-March 1969. In December 1968 and again in January 1969, Soviet border guards used non-lethal force to expel Chinese patrols from the island. More border incidents occurred in February 1969.

Then on March 2, 1969, Soviet border troops were sent to Damansky/Zhenbao Island to expel 30 Chinese soldiers who had landed on the island. Unbeknown to the Soviets, a large Chinese force, (300 soldiers, according to the Soviets) which was hidden and waiting in ambush in the nearby forest, opened fire on the Soviets. Fighting then broke out, with other units from both sides joining the fray.

Chinese units used artillery and small arms fire from their side of the Ussuri River, while the Soviets sent reinforcements to Damansky/Zhenbao Island from their side of the river.

A Chinese military report after the incident stated that the Soviets fired the first shots. More recent information indicates that the Chinese military planned the incident, and used elite army units with battle experience to ambush the Soviet patrol. In this way, China hoped to retaliate for the many Soviet

provocations, and also to signal that China would not be intimidated by the Soviet Union.

The two sides released different casualty figures for the Damansky/Zhenbao incident, although the Soviets may have suffered greater losses, at 59 dead and 94 wounded. Both the Chinese and Soviets claimed victory. The two sides also raised strong diplomatic protests against the other, accusing the other side of starting the incident. The Soviet Union accused China of being “reckless and provocative”, while China warned that if the Soviet Union continued to “provoke armed conflicts”, China would respond with “resolute counter-blows”.

Sensationalist news reports by the media from the two sides stirred up the general population in both countries. On March 3, 1969 in Beijing, large protests were held outside the Soviet Embassy, and Soviet diplomatic personnel were harassed. In the Soviet Union, demonstrations were held in Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. In Moscow,

angry crowds hurled stones, ink bottles, and paint at the Chinese Embassy.

On March 11, 1969 in Beijing, demonstrators besieged the Soviet Embassy in protest for the attack on the Chinese Embassy. Then when Soviet media

reported that captured Russian soldiers during the Damansky/Zhenbao incident had been tortured and executed, and their bodies mutilated, large demonstrations consisting of 100,000 people broke out in Moscow. Other mass assemblies also occurred in other Russian cities.

On March 15, 1969, a second (and larger) clash broke out in Damansky/Zhenbao Island, where both sides sent a force of regimental strength, or some 2,000-3,000 troops. The Chinese claimed that the Soviets fielded one motorized infantry battalion, one tank battalion, and four heavy-artillery battalions, or a total of over 50 tanks and armored vehicles, and scores of artillery pieces. The two sides again claimed victory in the 10-hour battle, and also accused the other side of firing the first shots. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

The Soviets lost a number of armored vehicles, and failed to expel the Chinese from the island. On

March 17, 1969, some 70 Soviet soldiers who were sent to retrieve a disabled T-62 tank were forced to retreat. The Chinese subsequently recovered the Soviet tank and transported it to Beijing where it was put on public display. Casualty figures for the March 15-17 battles are disputed. The Soviets place their own losses at 58 dead and 94 wounded. The Chinese place their losses at 29 dead, 62 wounded, and one missing. Foreign independent sources provide much higher combined total casualty figures, from 800 to 3,000 soldiers killed for both sides.

As in the first incident (March 2), more recent Chinese sources indicate that the Chinese Army had prepared for the second encounter (March 15). Chinese authorities had anticipated that the Soviets would return in force. The Chinese Army therefore sent a greater number of Chinese elite units, and fortified its side of the island with land mines. With these preparations, the Chinese succeeded in repelling the Soviets, who had attacked using armored units. After the encounter, the Soviets

began an extended artillery barrage of Chinese positions across the river, and hit targets as far as seven kilometers inside China.

The two incidents generated different reactions in the Chinese and Soviet governments. In China, Mao made efforts to prevent the crisis from escalating further. He ordered Chinese border troops not to retaliate to the Soviet artillery shelling of Chinese positions in Damansky/Zhenbao Island, and at the Chinese side of the Ussuri River. In Moscow, the Soviet government was thoroughly provoked by the two incidents, viewing them as a direct challenge from China.

However, Soviet authorities were divided as to the appropriate response. The Foreign Ministry called for caution, but the military wanted aggressive action. On May 24, 1969, because of continued border incidents by Russian troops, China filed a diplomatic protest, accusing the Soviet Union

of provoking war. On May 29, the Soviet government threatened to go to war with China, but also called for talks between the two sides.

As tensions increased, so did troop deployment to the disputed regions. Soon, 800,000 Chinese and 700,000 Soviet troops were deployed at the border. The Soviets continued to initiate border incidents, apparently to provoke a wider conflict. On August 13, 1969 in the Tieliketi Incident, 300 Soviet troops, supported by air and armored units, entered China’s

Tieliketi area, located in Xinjiang region, in the western border. There, they ambushed and killed 30 Chinese border guards.

By now, the Soviet Union was preparing for war, and increased its forces in Mongolia and carried out a large military exercise in the Far East. Soviet authorities notified Eastern Bloc countries that Russian planes could launch an air strike on China’s nuclear facility in Lop Nur, Xinjiang. In Washington, D.C., a Soviet diplomatic official, while dining with a U.S. State Department officer, broached the planned Soviet attack on China’s nuclear site, to gauge American reaction. The U.S. official reacted negatively, and subsequent U.S. warnings of intervening militarily if the Soviet Union attacked China, would have far-reaching repercussions in the ongoing Cold War.

Meanwhile in Beijing, Chinese authorities were concerned about the growing threat of war with the Soviet Union. Despite appearing defiant, and warning Russia that it too had nuclear weapons, China was unprepared to go to war, and its military was far weaker than that of the Soviet Union.

Exacerbating China’s position was its ongoing Cultural Revolution, which was causing serious

internal unrest.

February 29, 2020

March 1, 1941 – World War II: Bulgaria joins the Axis

On March 1, 1941, Bulgaria joined the Axis by signing the Tripartite Pact. Germany had long pressured Bulgaria into allying with the Axis, but the Bulgarian government balked at getting involved in the war. However, with the Italian offensive into Greece being turned back, Adolf Hitler decided to intervene, and demanded the passage of German forces into Bulgaria for the invasion of Greece (and later including Yugoslavia). Recognizing futility to stop a German attack into its territory, the Bulgarian government acquiesced, and joined the Tripartite Pact with assurances of being given Greek territory and continued diplomatic relations with its neighbors Turkey and the Soviet Union. At that time, Germany and the Soviet Union had a ten-year non-aggression pact.

(Taken from The Balkan Campaign – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In August 1940, Hitler gave secret instructions to his

military high command to prepare a plan for the invasion of the Soviet Union, to be launched in the spring of 1941. In October 1940-January 1941, the Germans

launched fierce air attacks on Britain,

which failed to force the latter to capitulate as Hitler had hoped. Hitler then suspended his planned invasion of

Britain

and instead focused on other ways to bring it to its knees. He turned to the Mediterranean Sea, whose

control by Germany and Italy would have the effect of cutting off Britain from its colonies in Africa and Asia via

the Suez Canal. In this plan, German forces would capture

Gibraltar through Spain,

thus sealing off the western end of the Mediterranean Sea, while the Italian

Army in Libya would capture

British-controlled Egypt as

well as the Suez Canal, sealing off the eastern end of the Mediterranean

Sea. German forces would

join in the final stages of the Italian offensive.

As the German military formulated the invasion plan of the

Soviet Union and the means to knock Britain out of the war, Hitler was

determined that no complications arose that would interfere with these

objectives. Foremost, Hitler had no

appetite for turmoil to break out in southeastern Europe,

especially the highly volatile Balkan region, the “powder keg” that had sparked

World War I. Politically and

strategically, Hitler wanted stability in the Balkans to keep away the Soviet

Union, with whom Germany

had a tenuous non-aggression pact.

Conflict in the Balkans would most likely prompt intervention by Russia, which

traditionally held a strong influence there.

Hitler had long stated that he had no territorial ambitions

on the Balkans. Instead, Germany’s main interest there was purely

economic, as the Balkan countries were Germany’s biggest partners,

supplying the latter with food and mineral resources. But of the greatest importance to Hitler were

the Ploiesti oil fields in Romania, which

provided the German military and industry with vital petroleum products.

Germany

and Italy mediated two

territorial disputes involving Romania

and its neighbors: on August 21, 1940, Romania

was persuaded to cede Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria,

and on August 30, 1940, it also relinquished one-third of Transylvania to Hungary. A few weeks earlier, in late June-early July

1940, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had used strong-arm tactics to force Romania to cede its northeastern regions of

Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, Hitler strove to convince Mussolini to stall the

latter’s territorial ambitions in the Balkans.

Mussolini had long viewed that in the German-Italian partition of

Europe, southeastern Europe and the Balkans

fell inside the Italian sphere of control.

Italian forces had invaded Albania

in April 1939 (separate article), and after the fall of France in June 1940, Mussolini exerted pressure

on Greece and Yugoslavia, and

threatened them with invasion. At that

time, Hitler was able to convince Mussolini to suspend temporarily his Balkan

ambitions and instead focus Italian efforts on defeating the British in North Africa.

But on October 7, 1940, at the request of Romanian dictator

Ion Antonescu, German forces entered Romania

to guard against a Soviet invasion; for Hitler, it was to protect the vital Ploiesti oil fields. Mussolini was outraged by this German action,

as he believed that Romania

fell inside his zone of control. Also

for Mussolini, Hitler’s move into Romania was only the latest in a

long list of stunts that had been made without previously consulting him, and

one that had to be reciprocated, or as Mussolini put it, “to repay him [Hitler]

with his own coin”. Hitler had invaded Poland, Denmark,

Norway, France, and the Low

Countries without informing Mussolini beforehand.

On October 28, 1940, Mussolini, without notifying Hitler,

launched the invasion of Greece

(previous article), despite insufficient military preparation and against the

counsel of his top generals. The

operation was a disaster, as the motivated Greek Army threw back the Italians

to Albania,

and then launched its own offensive.

Within three months, the Greeks occupied a quarter of Albanian

territory. Greece had declared its neutrality

at the start of World War II. But

because of the Italian invasion, the Greek government turned to Britain for

assistance. In early November 1940,

British forces had arrived, and occupied two strategically important Greek

islands, Crete and Limnos.

The unexpected Italian attack on Greece and likelihood of British

intervention in the Balkans shocked Hitler, seeing that his efforts to try and

maintain peace in the region had failed.

His prized Ploesti oil fields and the whole southeastern Europe were now vulnerable. On November 4, 1940, Hitler decided to become

involved in Greece

in order to bail out his beleaguered ally Mussolini and to forestall the British. On November 12, 1940, the German High Command

issued Directive No. 18, which laid out the German plan to contain the British

in the Mediterranean: German forces would invade northern Greece and Gibraltar in January 1941, and then

assist the Italians in attacking Egypt in the fall of 1941. However, Spain’s

pro-Axis dictator General Francisco Franco refused to allow German troops into Spain, forcing Germany

to suspend its invasion of Gibraltar. On December 13, 1940, the German military

issued Directive No. 20, which finalized the invasion of Greece under

codename Operation Marita. In the final

plan, German forces in Bulgaria would open a second front in northeastern

Greece and capture the whole Greek northern coast, link up with the Italians in

the northwest, and if necessary, push south toward Athens and seize the rest of

Greece. Operation Marita was scheduled

for March 1941; however, delays would cause the invasion to be launched one

month later.

For the invasion of Greece,

Hitler considered it necessary to bring into the Axis fold the governments of Hungary, Romania,

Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia,

notwithstanding their stated neutrality at the start of the World War II. With their cooperation, German forces would

cross their territories through Central and Eastern Europe,

as well as control their military-important infrastructures, such as airfields

and communications systems. Hungary, which had benefited territorially in

the German seizure of Czechoslovakia

and Axis arbitration of Transylvania, was drawn naturally to Germany. On November 20, 1940, the Hungarian

government joined the Tripartite Pact .

Three days later, Romania

also joined the Pact, as Romanian leader Antonescu was motivated to do so by

fear of a Soviet invasion. In succeeding

months, large numbers of German forces and weapons, passing through Hungary, would assemble in Romania, mainly for the planned invasion of the Soviet Union (whose operational plan would be finalized

in December 1940 under the top-secret Operation Barbarossa).

Bulgaria

balked at joining the Pact and thus be openly associated with the Axis, and

also was concerned that participating in the invasion of Greece would leave its eastern border vulnerable

to an attack by Turkey,

which was allied with Greece. The Bulgarians also were aware of a Soviet

plan to capture Varna, Bulgaria’s Black sea port, which the Soviets

would use to seize control of the Turkish Straits, which was a source of a

long-standing dispute between the Soviet Union and Turkey.

However, Hitler exerted strong diplomatic pressure on Bulgaria and

also promised to protect Bulgarian territorial integrity. Bulgaria acquiesced and agreed to

allow German troops to enter Bulgarian territory. On February 28, 1941, German engineering

crews bridged the Danube River at the Romanian-Bulgarian border, and the first

German units crossed into Bulgaria

and continued to that country’s eastern border.

The next day, March 1st, Bulgaria

joined the Tripartite Pact, officially joining the Axis. On March 2, 1941, German forces involved in

Operation Marita entered Bulgaria

and proceeded south to the Bulgarian-Greek border.

To assure Turkey of German intentions, Hitler wrote to the

Turkish government to explain that the German presence in Bulgaria was directed at Greece. To further allay the Turks, German troops

were positioned far from the Turkish border.

The Turkish government accepted the German clarification, and agreed to

stand down its forces during the German attack on Greece.

Meanwhile, Greece

was aware of German plans, and in the previous months, held talks with Britain and Yugoslavia to formulate a common

strategy against the anticipated German attack.

The dilemma for Greece was that by March 1941, the greater part of its

military forces were still tied down against the Italians in southern Albania,

leaving insufficient units to defend the rest of the country’s northern

border. At the request of the Greek

government, Britain and its

dominions, Australia and New Zealand, sent 58,000 troops to Greece; this force arrived in March 1941 and

deployed in Greece’s

north central border.

With regards to Yugoslavia, Hitler exerted great

effort to try and persuade the officially neutral but Allied-leaning government

of Yugoslav Prime Minister Dragisha Cvetkovic to join the Axis. In a series of high-level meetings between the

two countries which even included Hitler’s participation, the Germans offered

sizable rewards to Yugoslavia

for joining the Axis, including Greek territory that would include Salonica

which would give Yugoslavia

access to the Aegean Sea. Talks went nowhere until Hitler met with

Prince Paul on March 4, 1941, which led two weeks later to the Yugoslav

government agreeing to join the Axis. On

March 25, 1941, Yugoslavia

signed the Tripartite Pact, motivated by a secret clause in the agreement that

contained three stipulations: the Axis promised to respect Yugoslavian

sovereignty and territorial integrity, the Yugoslavian military would not be

required to assist the Axis, and Yugoslavia would not be required to

allow Axis forces to pass through its territory. But two days later, March 27, the pro-Allied

Serbian military high command deposed the Yugoslav government and installed

itself in a military regime, arrested Prince Paul, and named the 17-year old

minor crown prince as King Peter II. The

new military government assured Germany

that Yugoslavia

wanted to maintain friendly ties between the two countries, albeit that it

would not ratify the Tripartite Pact.

Anti-German mass demonstrations broke out in Belgrade and other Serbian cities.

As a result of the coup, a furious and humiliated Hitler

believed that Yugoslavia had

taken a stand favoring the Allies, despite the new Yugoslav government’s

conciliatory position toward Germany. On March 27, 1941, just hours after the coup,

Hitler convened the German military high command and stated his intention to

“destroy Yugoslavia

as a military power and sovereign state”.

He ordered the formulation of an invasion plan for Yugoslavia, which was to be carried out together

with the attack on Greece. Despite the time constraint (the attack on

Greece was set to be launched in ten days, April 6, 1941), the German military

finalized a lightning attack for Yugoslavia, code-named Operation 25, to be

under taken in coordination with the operation on Greece.

Hitler invited Bulgaria

to participate in the attack on Yugoslavia,

but the Bulgarian government declined, citing the need to defend its

borders. As well, Hungary demurred, as it had just recently signed

a non-aggression pact with Yugoslavia,

but it agreed to allow the German invasion forces to mass in its southwestern

border with Yugoslavia. Romania was not asked to join the

invasion.

Mussolini, after conferring with Hitler, agreed to

participate, and the Italian forces were to undertake the following:

temporarily cease operations at the Albanian front; protect the flank of the

German forces invading from Austria

to Slovenia; seize Yugoslav

territories along the Adriatic coast; and link up with German forces for the

invasion of Greece.

On April 3, 1941, Yugoslavia

sent emissaries to Moscow to try and arrange a

mutual defense treaty with the Soviet Union. Instead, on April 5, the Soviet government

agreed only to a treaty of friendship and non-aggression with Yugoslavia,

which did not promise Soviet protection in case of foreign aggression. As a result, Hitler was free to invade Yugoslavia

without fear of Soviet intervention. On

April 6, 1941, Germany and Italy launched the invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece, discussed separately in the

next two chapters.

February 28, 2020

February 29, 1992 – The start of the two-day independence referendum in Bosnia and Herzegovina

On February 29 and March 1, 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina held a referendum to decide for independence or to remain as a constituent republic within Yugoslavia. The turn-out was 63.4%, of whom 99.7% voted for independence. The voters consisted mainly of Bosniak and Bosnian Croats who favored independence. Bosnian Serbs, who comprised about 30% of the population, largely boycotted the referendum or were prevented from voting by Bosnian Serb authorities.

Following the referendum, on March 3, 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence as

the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. On April 7,

1992, the United States and European Economic Community recognized the new state; other countries soon did the same. On May 22, 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina was admitted to the United Nations.

However, also on April 7, 1992, Bosnian Serbs declared a separate independence as the Republika Srpska, with its Assembly issuing a declaration on May 12, “Six Strategic Goals of the Serbian Nation”, notably, “The first such goal is separation of the two national communities – separation of states, separation from those who are our enemies and who have used every opportunity, especially in this century, to attack us, and who would continue with such practices if we were to stay together in the same state.”.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

(Taken from Bosnian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background

Bosnia-Herzegovina has three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), comprising 44% of the

population, Bosnian Serbs, with 32%, and Bosnian Croats, with 17%. Slovenia and Croatia declared their independences in June 1991. On October 15, 1991, the Bosnian parliament declared the independence of

Bosnia-Herzegovina, with Bosnian Serb delegates boycotting the session in protest. Then acting on a request from both the Bosnian parliament and the Bosnian Serb leadership, a European Economic Community arbitration commission gave its opinion, on January 11, 1992, that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence cannot be recognized, since no

referendum on independence had taken place.

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s northern regions. On January 5, 1992, Bosnian Serbs seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own country. Bosnian Croats, who also comprised a sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence.

Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented into three republics, formed along ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslav constituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretly agreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majority population of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbians and Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armed conflict between them. By this time, heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to open hostilities.

Mediators from Britain and Portugal made a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincing Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political power in a decentralized government. Just ten days later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejected the agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

War

At any rate, by March 1992, fighting had already broken out when Bosnian Serb forces attacked Bosniak villages in eastern Bosnia. Of the three sides, Bosnian Serbs were the most powerful early in the war, as they were backed by the Yugoslav Army. At their peak, Bosnian Serbs had 150,000 soldiers, 700 tanks, 700 armored personnel carriers, 3,000 artillery pieces, and several aircraft. Many Serbian militias also joined the Bosnian Serb regular forces.

Bosnian Croats, with the support of Croatia, had 150,000 soldiers and 300 tanks. Bosniaks were at a great disadvantage, however, as they were unprepared for war. Although much of Yugoslavia’s war arsenal was stockpiled in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the weapons were held by the Yugoslav Army (which became the Bosnian Serbs’ main fighting force in the early stages of the war). A United Nations (UN) arms embargo on Yugoslavia was devastating to Bosniaks, as they were prohibited from purchasing weapons

from foreign sources.

In March and April 1992, the Yugoslav Army and Bosnian Serb forces launched large-scale operations in eastern and northwest Bosnia-Herzegovina. These offensives were so powerful that large sections of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat territories were captured and came under Bosnian Serb control. By the end of 1992, Bosnian Serbs controlled 70% of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Then under a UN-imposed resolution, the Yugoslav Army was ordered to leave Bosnia-Herzegovina. However, the Yugoslav Army’s withdrawal did not affect seriously the Bosnian Serbs’ military capability, as a great majority of the Yugoslav

soldiers in Bosnia-Herzegovina were ethnic Serbs. These soldiers simply joined the ranks of the Bosnian Serb forces and continued fighting, using the same

weapons and ammunitions left over by the departing Yugoslav Army.

In mid-1992, a UN force arrived in Bosnia-Herzegovina that was tasked to protect civilians and refugees and to provide humanitarian aid. Fighting between Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats occurred in Herzegovina (the southern regions) and central Bosnia, mostly in areas where Bosnian Muslims formed a civilian majority. Bosnian Croat forces held the initiative, conducting offensives in Novi Travnik and Prozor. Intense artillery shelling reduced Gornji Vakuf to rubble; surrounding Bosniak villages also were taken, resulting in many civilian casualties.

In May 1992, the Lasva Valley came under attack

from the Bosnian Croat forces who, for 11 months, subjected the region to intense artillery shelling and ground attacks that claimed the lives of 2,000 mostly civilian casualties. The city of Mostar, divided into

Muslim and Croat sectors, was the scene of bitter fighting, heavy artillery bombardment, and widespread destruction that resulted in thousands of civilian deaths. Numerous atrocities were

committed in Mostar.

By July 1993, however, Bosniaks had formed a relatively competent military force that was armed with weapons produced from a rapidly growing local arms-manufacturing industry. Bosniaks, therefore, were better able to defend their territories, and even launch some of their own limited offensive operations.

Then in early 1994, with another Bosnian Serb general offensive looming, Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats found common ground. With the urging of the United States, on February 23, 1994, Bosniaks

and Bosnian Croats formed a unified government under the “Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina”. The civil war shifted to fighting between the combined Bosniak-Bosnian Croat forces against the Bosnian Serb Army.

In early 1994, Bosnian Serb forces laid siege to Sarajevo, Bosnia’s capital, relentlessly pounding the city with heavy artillery and inflicting heavy civilian casualties. The siege of the capital drew international condemnation, with the UN and the North Atlantic

Treaty Organization (NATO) becoming increasingly involved in the war. NATO declared Bosnia-Herzegovina a no-fly zone. On February 28, 1994, NATO warplanes downed four Serbian aircraft over Banja Luka.

Under a UN threat of a NATO airstrike, Bosnian Serbs were forced to lift the siege on Maglaj; supply convoys thus were able to reach the city by land, the first time in nearly ten months. In April 1994, NATO warplanes attacked Bosnian Serb forces that were threatening a UN-protected area in Gorazde. Later that month, a Danish contingent of the UN forces engaged Bosnian Serb Army units in the village of Kalesija. The NATO air strikes, which greatly contributed to ending the war, were conducted in coordination with the UN humanitarian and peacekeeping forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

With the US lifting its arms embargo on Bosnia-Herzegovina in November 1994, Bosniak forces

began to receive shipments of American weapons.

The UN was also alarmed at the increasing reports of atrocities being committed by Bosnian Serb forces. After Bosnian Serb artillery attacks killed 37 persons and 90 others in Sarajevo in August 1995, NATO launched a large airstrike on Bosnian Serb Army positions. Between August 30 and September 14, four hundred NATO planes launched thousands of attacks against key Bosnian Serb military units and installations in Sarajevo, Pale, Lisina, and other sites.

Meanwhile, starting in the summer of 1995, Bosnian Croat and Bosniak armies had begun to take the initiative in the ground war against the Bosnian Serbs. The combined allied armies launched a series of offensives against Bosnian Serbs in western Bosnia. By the end of July, the allies had captured

1,600 square kilometers of territory. In the Krajina region, a massive Bosnian Croat-Bosniak offensive involving 170,000 soldiers, 250 tanks, 500 artillery pieces, and 40 planes overwhelmed the Bosnian Serb forces of 30,000 troops, 300 tanks, 200 armored carriers, 560 artillery pieces, 135 anti-aircraft guns, and 25 planes.

By October 12, Bosnian Serb-held Banja Luka was in sight. The Bosnian Croat-Bosniak offensives had captured western Bosnia and 51% of the country, and threatened to advance further east. By this time, Bosnian Serb forces were on the brink of defeat.

Representatives from the three ethnic groups now met to negotiate an end to the war. On September 14, NATO ended its air strikes against Bosnian Serb forces. By month’s end, fighting was winding down in most sectors.

On November 21, 1995, high-level government officials from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, and Croatia

signed a peace agreement, bringing the war to an end. The reconstruction of the war-ravaged country

soon began.

Many atrocities and human rights violations were committed in the war, the great majority of which were perpetrated by Bosnian Serbs, but also by Bosnian Croats, and to a much lesser extent, by Bosniaks.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former

Yugoslavia (ICTY), established by the UN to prosecute war crimes, determined that Bosnian Serb atrocities committed in the town of Srebrenica, where 8,000 civilians were killed, constituted a genocide. Other

atrocities, such as the killing and wounding of over one hundred residents in Markale on February 5, 1994 and August 28, 1995 resulting from the Serbian

mortar shelling of Sarajevo, have been declared by the ICTY as ethnic cleansing (a war crime less severe than genocide).

Bosnian Croat forces also perpetrated many atrocities, including those that occurred in the Lasva

Valley, which caused the deaths and forced disappearances of 2,000 Bosniaks, as well as other violent acts against civilians. Bosniak forces also committed crimes against civilians and captured soldiers, but these were of much less frequency and severity.

About 90% of all crimes in the Bosnian War were attributed to Bosnian Serbs. The ICTY has convicted

and meted out punishments to many perpetrators, who generally were military commanders and high-ranking government officials. The war caused some 100,000 deaths, both civilian and military; over two million persons were displaced by the fighting.

After the war, Bosnia-Herzegovina retained its territorial integrity. As a direct consequence of

the war, Bosnia-Herzegovina established a decentralized government composed of two political and geographical entities: the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (consisting of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat majorities) and the Republic of Srpska (consisting of Bosnian Serbs). The president of Bosnian-Herzegovina is elected on rotation, with a Bosniak,

Bosnian Croat, and Bosnian Serb taking turns as the country’s head of state.

February 27, 2020

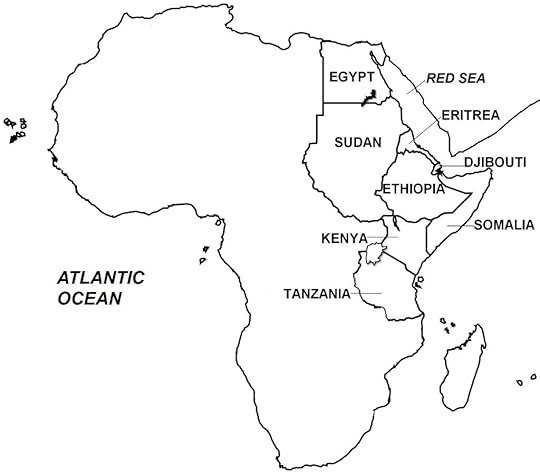

February 28, 1974 – Ethiopian Civil War: Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold resigns

In January 1974, in what became the first of a series of decisive events, soldiers stationed at Negele, Sidamo Province, mutinied in protest of low wages and other poor conditions; in the following days, military units in other locations mutinied as well. In February 1974, as a result of rising inflation and unemployment and deteriorating economic conditions resulting from the global oil crisis of the

previous year (1973), teachers, workers, and students launched protest demonstrations and marches in Addis Ababa demanding price rollbacks, higher labor wages, and land reform in the countryside. These protests degenerated into bloody riots. In the aftermath, on February 28, 1974, long-time Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold resigned and was replaced by Endalkachew Makonnen, whose government raised the wages of military personnel

and set price controls to curb inflation. Even so, the government, which was controlled by nobles, aristocrats, and wealthy landowners, refused or were unaware of the need to implement major reforms in the face of growing public opposition.

In March 1974, a group of military officers led by Colonel Alem Zewde Tessema formed the multi-unit “Armed Forces Coordinating Committee” (AFCC) consisting of representatives from different sectors of the Ethiopian military, tasked with enforcing cohesion among the various forces and assisting the government in maintaining authority in the face of growing unrest. In June 1974, reformist junior officers of the AFCC, desiring greater reforms and dissatisfied with what they saw was the AFCC’s close association with the government, broke away and formed their own group.

Ethiopia and nearby countries.

(Taken from Ethiopian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

This latter group, which took the name “Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army, soon grew to about 110 to 120 enlisted men and officers (none above the rank of major) from the 40 military and security units across the country, and elected Majors Mengistu Haile Mariam and Atnafu Abate as its chairman and vice-chairman, respectively. This group, which became known simply as Derg (an Ethiopian word meaning “Committee” or “Council”), had as its (initial) aims to serve as a conduit for various military and police units in order to maintain peace and order, and also to

uphold the military’s integrity by resolving grievances, disciplining errant officers, and curbing corruption in the armed forces.

Derg operated anonymously (e.g. its members were not publicly known initially), but worked behind such populist slogans as “Ethiopia First”, “Land to the Peasants”, and “Democracy and Equality to all” to gain

broad support among the military and general population. By July 1974, the Derg’s power was felt not only within the military but in the government itself, and Haile Selassie was forced to implement a number of political measures, including the release of

political prisoners, the return of political exiles to the country, passage of a new constitution, and more critically, to allow Derg to work closely with the

government. Under Derg pressure, the government of Prime Minister Makonnen collapsed; succeeding as Prime Minister was Mikael Imru, an aristocrat who held leftist ideas.

Haile Selassie’s concessions to the Derg included measures to investigate government corruption and mismanagement. In the period that followed, Derg arrested and imprisoned many high-ranking imperial, administrative, and military officials, including former Prime Ministers Habte-Wold and Makonnen, Cabinet

members, military generals, and regional governors. In August 1974, a proposed constitution that called for establishing a constitutional monarchy was set aside. Now operating virtually with impunity, the

Derg took aim at the imperial court, dissolving the imperial governing councils and royal treasury, and seizing royal landholdings and commercial assets. By this time, Haile Selassie’s government virtually had ceased to exist; de facto power was held by the military, or more precisely, by Derg.

The culmination of events occurred when Haile Selassie was accused of deliberately denying the existence of a widespread famine that

currently was ravaging Ethiopia’s Wollo province, which already had killed some 40,000 to 80,000 to as many as 200,000 people. Conflicting reports

indicated that Haile Selassie was not aware of the famine, was fully aware of it, or that government administrators withheld knowledge of its existence from the emperor. By August 1974, large protest demonstrations in Addis Ababa were demanding the emperor’s arrest. Finally on September 12, 1974, the Derg overthrew Haile Selassie in a bloodless coup, leading away the frail, 82-year old ex-monarch to imprisonment.

The Derg gained control of Ethiopia but did not abolish the monarchy outright, and announced that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, Haile Selassie’s son who was currently abroad for medical treatment, was to succeed to the throne as the new “king” on his return to the country. However, Prince Wossen rejected the offer and remained abroad. The Derg then withdrew

its offer and in March 1975, abolished the monarchy altogether, thus ending the 800 year-old Ethiopian Empire. (On August 27, 1975, or nearly one year after his arrest, Haile Selassie passed away under mysterious circumstances, with Derg stating that complications from a medical procedure had caused his death, while critics alleging that the ex-monarch was murdered.)

The surreptitious means by which Derg, in a period of six months, gained power by progressively dismantling the Ethiopian Empire and ultimately deposing Haile Selassie, sometimes is referred to as the “creeping coup” in contrast with most coups, which are sudden and swift. On September 15, 1974, Derg formally took control of the government and renamed itself as the Provisional Military Administrative Council (although it would continue to be commonly known as Derg), a ruling military junta under General Aman Andom, a non-member Derg whom the Derg appointed as its Chairman; General Aman thereby also assumed the role of Ethiopia’s head of state.

At the outset, Derg had its political leanings embodied in its slogans “Ethiopia First” (i.e. nationalism) and “Democracy and Equality to all”. Soon, however, it abolished the Ethiopian parliament, suspended the constitution, and ruled by decree. In early 1975, Derg launched a series of broad reforms that swept away the old conservative order and began the country’s transition to socialism. In January-February 1975, nearly all industries were nationalized. In March, an agrarian reform program

nationalized all farmlands (including those owned by the country’s largest landowner, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church), reduced farm sizes, and abolished

tenancy farming. Collectivized agriculture was introduced and farmers were organized into peasant

organizations. (Land reform was fiercely resisted in such provinces as Gojjam, Wollo, and Tigray, where most farmers owned their lands and tenant farming was not widely practiced.) In July 1975, all urban lands, houses, and buildings were nationalized and city residents were organized into urban dwellers’ associations, known as “kebeles”, which would play a major role in the coming civil war. Despite the extensive nationalization, a few private sector industries that were considered vital to the economy were left untouched, e.g. the retail and wholesale trade, and import and export industries.

In April 1976, Derg published the “Program for the National Democratic Revolution”, which outlined the regime’s objectives of transforming Ethiopia into a socialist state, with powers vested in the peasants, workers, petite bourgeoisie, and anti-feudal and anti-monarchic sectors. An agency called the “Provisional Office for Mass Organization Affairs” was established to work out the transformative process toward socialism.

War

The political instability and power struggles that followed the Derg’s coming to power, the escalation of pre-existing separatist and Marxist insurgencies (as well as the formation of new rebel movements), and the intervention of foreign players, notably Somalia as well as Cold War rivals, the Soviet Union and United States, all contributed to the multi-party, multi-faceted conflict known as the Ethiopian Civil War.

The Derg government underwent power struggles during its first years in office. General Aman, the non-Derg who had been named to head the government, immediately came into conflict with Derg on three major policy issues: First, he wanted to reduce the size of the 120-member Derg; Second, as an ethnic Eritrean, he was opposed to the Derg’s use of force against the Eritrean insurgency; and Third, he opposed Derg’s plan to execute the imprisoned civilian and military officials associated with the former regime. In November 1974, Derg leveled charges against General Aman and issued a warrant

for his arrest. On November 23, 1974, General Aman was killed in a gunfight with government security personnel who had been sent to arrest him.

February 26, 2020

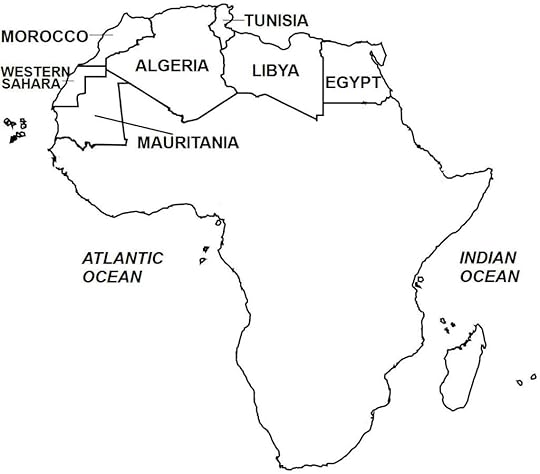

February 27. 1976 – Western Sahara War: The Polisario Front declares independence as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from Spanish Sahara, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would

include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

Map showing location of Western Sahara.

(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

On December 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292 declaring the UN’s interest in evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawis in the Spanish

territory. For this purpose, the UN formed the UN Decolonization Committee, which in May – June 1975, carried out a fact-finding mission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15,

1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the general population in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara, however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under the leadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy such

support. In Algeria, the UN Committee found strong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self- determination.

Algeria previously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an Arab League summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria was openly defending the Polisario Front’s struggle for independence, a support that later would include military and economic aid and would have a crucial effect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of King Mohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claim

and asked Spain to postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish government granted the Moroccan request. In June 1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UN Decolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision, which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers to Spanish Sahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Mauritanian entity”;

3. There existed “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance between the Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara. They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating to

the land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and the territory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJ concluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorial

sovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Morocco or the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such a nature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular, … the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvement radicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of the court’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respective claims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish any tie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing the post-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri and Polisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers,

Algeria to negotiate the transfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economic

concessions to Spain, particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did not prosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greater pressures exerted by the other competing parties.

Shortly after the ICJ decision was released, King Hassan II announced that Morocco would hold the “Green March”, set for November 6, 1975, and called on Moroccans to march to and occupy Spanish Sahara. On that date, the Green March (the color

green symbolizing Islam) was carried out, with some 350,000 Moroccan civilians, protected by 20,000 soldiers, crossed the border from Tarfaya in southern

Morocco and occupied some border regions in northern Spanish Sahara. Under instructions from the Spanish central government in Madrid, Spanish troops did not resist the incursion. On November 9, the marchers returned to Morocco, on orders of King Hassan II who declared the action a success.

On October 31, 1975, six days before the Green March began, units of the Moroccan Army entered Farsia, Haousa and Jdiriya in northeast Saharan territory to deter Algerian intervention. Spain had protested the Moroccan action to the UN in a futile attempt to have the international body stop the march; instead, the United Nations Security Council

(UNSC) passed Resolution 380 that deplored the march and called on Morocco to withdraw from the territory.

The timing of the escalating crisis could not have come at a worse time for Spain. In late October 1975, General Francisco Franco, Spain’s dictator, was terminally ill and soon passed away on November 20, 1975. In the period before and after his death, Spain

underwent great political uncertainty, as the sudden void left by General Franco, who had ruled for 40 years, threatened to ignite a political power struggle. The tenuous government, now led by King Juan Carlos as head of state, was unwilling to face a potentially ruinous war. World-wide colonialism was

at its twilight– just one year earlier, Portugal, one of the last colonial powers, had agreed to end its long colonial wars against African nationalist movements, eventually leading to the independences in 1975 of its African possessions of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea (since 1973), Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

By late October 1975, Spanish officials had begun to hold clandestine meetings in Madrid with representatives from Morocco and Mauritania. As a precaution for war, in early November 1975, Spain

carried out a forced evacuation of Spanish nationals from the territory. On November 12, further negotiations were held in the Spanish capital, culminating two days later (November 14) in the

signing of the Madrid Accords, where Spain ceded the administration (but not sovereignty) of the territory, with Morocco acquiring the regions of El-Aaiún,

Boujdour, and Smara, or the northern two-thirds of the region; while Mauritania the Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros) region, or the southern third; in exchange for Spain acquiring 35% of profits from the territory’s phosphate mining industry as well as off-shore fishing rights. Joint administration by the three parties through an interim government (led by the territory’s Spanish Governor-General) was undertaken in the transitional period for full transfer to the new Moroccan and Mauritanian authorities. (The Madrid Accords was not, and also since has not, been recognized by the UN, which officially continued to regard Spain as the “de jure”, if not “de facto”, administrative authority over the territory;

furthermore, the UN deems the conflict region as occupied territory by Morocco and, until 1979, also by Mauritania.)

On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from the territory, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would

include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

February 25, 2020

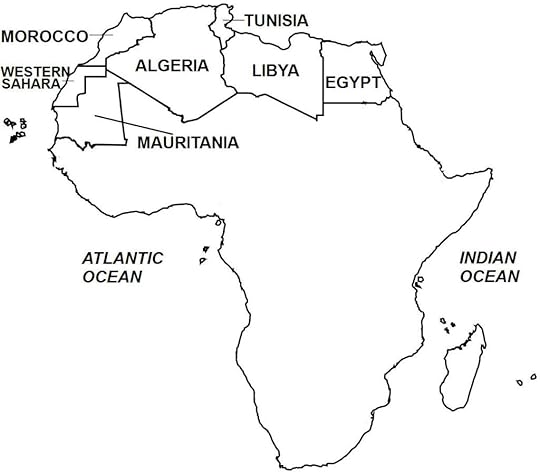

February 26, 1976 – Western Sahara War: Spain withdraws from Western Sahara

On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from Spanish Sahara, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would

include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

Map showing location of Western Sahara.

(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

On December 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292 declaring the UN’s interest in evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawis in the Spanish territory. For this purpose, the UN formed the UN

Decolonization Committee, which in May – June 1975, carried out a fact-finding mission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15,

1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the general population in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara, however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under the leadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy such

support. In Algeria, the UN Committee found strong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self-determination.

Algeria previously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an Arab League summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria was openly defending the Polisario Front’s struggle for independence, a support that later would include military and economic aid and would have a crucial effect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of King Mohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claim

and asked Spain to postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish government granted the Moroccan request. In June 1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UN Decolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision,

which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers to Spanish Sahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the

Mauritanian entity”;

3. There existed “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance between the Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara. They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating to

the land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and the territory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJ concluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorial

sovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Morocco or the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such a nature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular, … the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine

expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvement radicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of the court’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respective claims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish any tie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing the post-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri and Polisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers,

Algeria to negotiate the transfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economic

concessions to Spain, particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did not prosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greater pressures exerted by the other competing parties.

Shortly after the ICJ decision was released, King Hassan II announced that Morocco would hold the “Green March”, set for November 6, 1975, and called on Moroccans to march to and occupy Spanish Sahara. On that date, the Green March (the color

green symbolizing Islam) was carried out, with some 350,000 Moroccan civilians, protected by 20,000 soldiers, crossed the border from Tarfaya in southern

Morocco and occupied some border regions in northern Spanish Sahara. Under instructions from the Spanish central government in Madrid, Spanish troops did not resist the incursion. On November 9, the marchers returned to Morocco, on orders of King Hassan II who declared the action a success.

On October 31, 1975, six days before the Green March began, units of the Moroccan Army entered Farsia, Haousa and Jdiriya in northeast Saharan territory to deter Algerian intervention. Spain had protested the Moroccan action to the UN in a futile attempt to have the international body stop the march; instead, the United Nations Security Council

(UNSC) passed Resolution 380 that deplored the march and called on Morocco to withdraw from the territory.

The timing of the escalating crisis could not have come at a worse time for Spain. In late October 1975, General Francisco Franco, Spain’s dictator, was terminally ill and soon passed away on November 20, 1975. In the period before and after his death, Spain underwent great political uncertainty, as the sudden void left by General Franco, who had ruled for 40 years, threatened to ignite a political power struggle. The tenuous government, now led by King Juan

Carlos as head of state, was unwilling to face a potentially ruinous war. World-wide colonialism was at its twilight – just one year earlier, Portugal, one of the last colonial powers, had agreed to end its long colonial wars against African nationalist movements, eventually leading to the independences in 1975 of its African possessions of Angola, Mozambique,

Portuguese Guinea (since 1973), Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

By late October 1975, Spanish officials had begun to hold clandestine meetings in Madrid with representatives from Morocco and Mauritania. As a precaution for war, in early November 1975, Spain

carried out a forced evacuation of Spanish nationals from the territory. On November 12, further negotiations were held in the Spanish capital, culminating two days later (November 14) in the

signing of the Madrid Accords, where Spain ceded the administration (but not sovereignty) of the territory, with Morocco acquiring the regions of El-Aaiún,

Boujdour, and Smara, or the northern two-thirds of the region; while Mauritania the Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros) region, or the southern third; in exchange for Spain acquiring 35% of profits from the territory’s phosphate mining industry as well as off-shore fishing rights. Joint administration by the three parties through an interim government (led by the territory’s Spanish Governor-General) was undertaken in the transitional period for full transfer to the new Moroccan and Mauritanian authorities. (The Madrid Accords was not, and also since has not, been recognized by the UN, which officially continued to regard Spain as the “de jure”, if not “de facto”, administrative authority over the territory;

furthermore, the UN deems the conflict region as occupied territory by Morocco and, until 1979, also by Mauritania.)

On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from the territory, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

February 24, 2020

February 25, 1991 – Gulf War: An Iraqi Scud missile strike kills 28 American soldiers in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia

During the Gulf War, Iraq fired Scud missiles into Saudi Arabia, the deadliest occurring on February

25, 1991 when a missile struck a U.S. Army barracks in Dhahran, killing 28 American soldiers and wounding 100 others. During the war, Iraq fired a total of 88 Scud missiles, 46 against Saudi Arabia and 42 against Israel. The missile attacks on Israel also

caused a number of casualties, but were generally ineffective because of the projectiles’ reduced accuracy resulting from the great distances involved.

The U.S. Air Force increased its efforts to find the Iraqi mobile Scud launchers inside Iraq, at its peak allocating 40% of its resources to so-called “Scud hunts”. American and British Special Forces teams

also were inserted inside Iraq to locate missile sites for destruction by coalition aircraft. Soon, however, the U.S. military high command admitted difficulty finding the mobile Scud launchers, which evaded radar detection by seeking cover under man-made and natural protective formations; General Schwarzkopf likened the task of locating a mobile Scud launcher to “finding a needle in a haystack”. The Scud attacks continued, and post-war findings showed that much of Iraq’s Scud capabilities remained formidable. Because of the Scud attacks

as well as Iraqi artillery fire on coalition troops on the Saudi border, the Allied high command decided to launch the ground offensive.

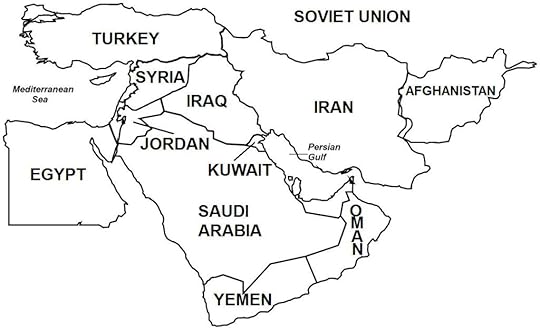

Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and other countries in the Middle East.

(Taken from Gulf War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

On August 2, 1990, Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait (previous article), overthrew the ruling monarchy and seizing control of the oil-rich country. A “Provisional Government of Free Kuwait” was established, and two days later, August 4, the Iraqi government, led by Saddam Hussein, declared Kuwait a republic. On August 8, Saddam changed his mind and annexed Kuwait as a “governorate”, declaring it Iraq’s 19th province.

Jaber III, Kuwait’s deposed emir who had fled to neighboring Saudi Arabia in the midst of the invasion, appealed to the international community. On August 3, 1990, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) issued Resolution 660, the first of many resolutions

against Iraq, which condemned the invasion and demanded that Saddam withdraw his forces from Kuwait. Three days later, August 6, the UNSC released Resolution 661 that imposed economic sanctions against Iraq, which was carried out through a naval blockade authorized under UNSC Resolution 665. Continued Iraqi defiance subsequently would

compel the UNSC to issue Resolution 678 on November 29, 1990 that set the deadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait on or before January 15, 1991 as well as authorized UN member states to enforce the withdrawal if necessary, even through the use of force. The Arab League, the main regional organization, also condemned the invasion, although Jordan, Sudan, Yemen, and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) continued to support Iraq.

Iraq’s annexation of Kuwait upset the political, military, and economic dynamics in the Persian Gulf region, and by possessing the world’s fourth largest armed forces, Iraq now posed a direct threat to Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. The United States

announced that intelligence information detected a build-up of Iraqi forces in Kuwait’s southern border with Saudi Arabia. Saddam, however, declared that Iraq had no intention of invading Saudi Arabia, a

position he would maintain in response to allegations of his territorial ambitions.

Meeting with U.S. Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney who arrived in Saudi Arabia shortly after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, Saudi King Fahd requested U.S. military protection. U.S. President George H.W. Bush accepted the invitation, as doing so would not only defend an important regional ally, but prevent Saddam from gaining control of the oil fields of Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest petroleum producer. With its conquest of Kuwait, Iraq now held 20% of the world’s oil supply, but annexing Saudi Arabia would allow Saddam to control 50% of the global oil reserves. By September 18, 1990, the U.S. government announced that the Iraqi Army was massed in southern Kuwait, containing a force of 360,000 troops and 2,800 tanks.

U.S. military deployment to Saudi Arabia, codenamed Operation Desert Shield, was swift; on August 8, just six days after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait,

American air and naval forces, led by two aircraft carriers and two battleships, had arrived in the Persian Gulf. Over the next few months, Iraq offered the United States a number of proposals to resolve the crisis, including that Iraqi forces would be withdrawn from Kuwait on the condition that Israel also withdrew its troops from occupied regions in Palestine (West Bank, Gaza Strip), Syria (Golan Heights, and southern Lebanon. The United States

refused to negotiate, however, stating that Iraq must withdraw its troops as per the UNSC resolutions before any talk of resolving other Middle Eastern

issues would be discussed. On January 9, 1991, as the UN-imposed deadline of January 15, 1991 approached, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker and Iraq’s Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz held last-minute talks in Geneva Switzerland (called the Geneva Peace Conference). But the two sides refused to tone down their hard-line positions, leading to the breakdown of talks and the imminent outbreak of war.

Because Mecca and Medina, Islam’s holiest sites, were located in Saudi Arabia, King Fahd received strong local and international criticism from other Muslim states for allowing U.S. troops into his country. At the urging of King Fahd, the United States organized a multinational coalition consisting of armed and civilian contingents from 34 countries which, apart from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait’s (exiled forces), also included other Arab and Muslim countries (Egypt, Syria, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, Turkey, Morocco, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). A force of about 960,000 troops was assembled, with U.S. soldiers accounting for 700,000 or about 70% of the total; Britain and France also sent sizable contingents, some 53,000 and 18,000 respectively, as well as large amounts of military equipment and supplies.

In talks with Saudi officials, the United States stated that the Saudi government must pay for the greater portion of the cost for the coalition force, as the latter was tasked specifically to protect Saudi Arabia. In the coming war, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and

other Gulf states contributed about $36 billion of the $61 billion coalition total war cost; as well, Germany and Japan contributed a combined $16 billion,

although these two countries, prohibited by their constitutions from sending armies abroad, were not a combat part of the coalition force.

President Bush overcame the last major obstacle to implementing UNSC Resolution 678 – the U.S. Congress. The U.S. Senate and House of Representatives were held by a majority from the opposition Democratic Party, which was opposed

to the Bush administration’s war option and instead believed that the UNSC’s economic sanctions against Iraq, yet barely two months in force, must be given

time to work. On January 12, 1991, a congressional joint resolution that authorized war, as per President Bush’s request, was passed by the House of Representatives by a vote of 250-183 and Senate by a vote of 52-47.

One major factor for U.S. Congress’ approval for war were news reports of widespread atrocities and human rights violations being committed by Iraq’s