Daniel Orr's Blog, page 104

March 12, 2020

March 13, 1979 – The New Jewel Movement (NJM), a Marxist-Leninist group, seizes power in a coup in Grenada

On March 13, 1979, the New Jewel Movement (NJM), a Marxist-Leninist group, seized power in Grenada, overthrowing the government of Prime Minister Eric Gairy in a nearly bloodless coup. The coup’s leader, Maurice Bishop, took over government authority, declared himself head of the “People’s Revolutionary Government”, suspended Grenada’s constitution, and thereafter ruled by decree in a dictatorship. The “Jewel” in New Jewel Movement is the acronym for “Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education, and Liberation”.

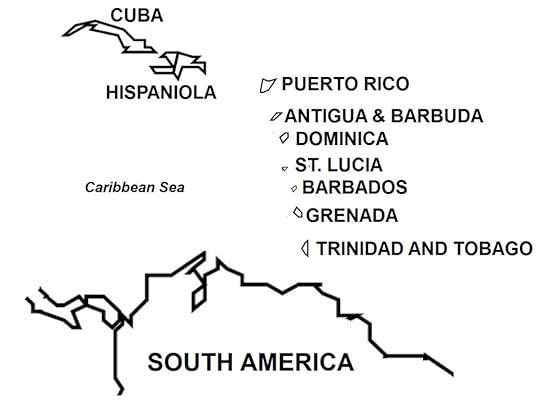

Diagram showing location of Grenada in the Caribbean Sea and just north of the South American mainland. Grenada consists of the main island (Grenada) and six very small islands located in its northern and southern ends.

(Taken from U.S. Invasion of Grenada – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

Grenada is a small island country located in the

southeastern section of the Caribbean Sea (Map

36). In 1974, the country gained its independence from the United Kingdom and thereafter experienced a period of political unrest starting with the contentious general elections of 1976. After the 1976 elections, a government was formed, which imposed repressive policies to curb political opposition and dissent. Then on March 13, 1979, communist politicians staged a coup that overthrew the government.

A socialist government was formed led by Maurice Bishop, who took the position of prime minister. The new government opened diplomatic relations with communist countries. In particular, Grenada became allied with Cuba and the Soviet Union, and supported their foreign policy initiatives. Prime Minister Bishop dissolved the Grenadian constitution, banned elections and multi-party

politics, and suppressed free expression and all forms of dissent.

The government began many social and economic projects, which ultimately proved successful. For

instance, sound financial policies allowed Grenada’s economy to grow and reduce the country’s dependence on imported goods. The government made major advances in upgrading the educational system, health care, and socialized housing programs. Public infrastructure projects were implemented.

Despite being officially socialist, the Grenadian government maintained its traditional ties to the West. Grenada retained its British Commonwealth membership, with Queen Elizabeth II as its symbolic head of state, and the British-inherited position of Governor General being maintained. Western foreign investments were encouraged, and investors from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada – among other countries – operated freely in the islands. Foreign tourists, who brought in substantial revenues to the local economy, were welcomed by the Grenadian government.

However, hardliners in Grenada’s communist party (called the New Jewel Movement) disagreed with Prime Minister Bishop’s double-sided policies. They demanded that he step down from office or agree to rule jointly with staunch communist party members. Prime Minister Bishop rejected both

suggestions. On October 12, 1983, the communist hardliners overthrew the government in a coup, and Prime Minister Bishop and other high-ranking government officials were arrested and jailed. A military council was formed to rule the country.

Widespread street protests and demonstrations broke out as a result of the coup, as Prime Minister Bishop was extremely popular with the people. The protesters demanded that Bishop be set free. Bishop’s military captors acquiesced, and released the ex-prime minister. But in the ensuing chaos, government troops opened fire on the protesters, killing perhaps up to a hundred persons. Bishop and other top government officials were rounded up and executed by firing squad.

The U.S. administration of President Ronald Reagan, following the events in Grenada with grave concern, believed that Cuba had planned the overthrow of Prime Minister Bishop’s moderately socialist government in order to install a staunchly communist regime. The United States believed that Cuba would then take full control of Grenada. Four years earlier in 1979, when the Grenadian communists took over power, U.S. president Jimmy Carter’s government had moved diplomatically to isolate Grenada by stopping U.S. military support and discouraging Americans from travelling there.

But President Reagan took an aggressive approach against Grenada: he ordered joint military exercises and mock amphibious operations in U.S.-allied countries in the Caribbean region. He also warned of Soviet-Cuban expansionism in the Western Hemisphere. Of particular concern to President Reagan was the construction of an airport at Point Salines at the southern tip of Grenada, which the U.S. military believed would be a Soviet airbase because its extended runway could land big, long-range Russian bombers. The U.S. government surmised that the Soviets planned to use Grenada as a forward base to supply communists in Central America, i.e. the Sandinista government in Nicaragua and the communist rebels in El Salvador and Guatemala. Increasing the Americans’ suspicion was the presence of Cuban construction workers at the Point Salines site – after the war, the U.S.

military learned that these were Cuban Army soldiers.

However, the Grenadian government insisted that the Point Salines facility would be used as an international airport for commercial airliners. As diplomatic relations deteriorated between the United States and Grenada, President Reagan ordered the evacuation of American citizens living in Grenada, the majority of whom were the 800 medical students enrolled at the American-owned St. George’s University. The U.S. government feared for the

safety of the students, as the Grenadian Army had posted soldiers at the school grounds and a nighttime curfew had been imposed on the island, with a shoot-to-kill order imposed against violators. As commercial flights to Grenada were cancelled already, President Reagan decided that the U.S. Armed Forces

should implement the evacuation.

On October 21, 1983, the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States asked the United States

to intervene militarily in Grenada, fearing that the political instability in that island could spread across the Caribbean region. The United States Armed Forces then revised its plan from an evacuation to include an invasion of Grenada.

Invasion

The United States identified three targets for the

invasion: Point Salines, Pearls Airport in Grenville, and St. George’s. Just before dawn on October 25, 1983, a battalion of U.S. Rangers was airdropped at the Point Salines Airport construction site. The soldiers

succeeded in taking control of the facility. The Rangers originally were planned to be landed by plane; the plan was aborted when U.S. reconnaissance detected that the airport runway was littered with obstacles. The anti-aircraft gunfire

from the Grenadian defenses was silenced by strikes from U.S. helicopter gunships. The U.S. Rangers soon secured and cleared the Point Salines Airport site, allowing American planes to land more troops, weapons, and supplies.

A few hours later, U.S. troops located St. George’s campus and evacuated the American students back to the United States. Advancing from Point Salines, U.S. forces met some sporadic resistance, including a Grenadian attack using Soviet armored carriers. By nightfall, the Americans were in control of much of the Point Salines outlying areas and had captured hundreds of Grenadian troops and the Cuban soldiers who had posed as construction workers. The prisoners were turned over to the Eastern Caribbean peacekeeping forces that had arrived to carry out policing duties.

Occurring simultaneously with the Point Salines invasion, U.S. Marines landed in Grenville, located east of the island (Map 37), which was taken with little opposition. Pearls Airport then came under American control, where more troops, weapons, and supplies were landed by U.S. planes. American forces then moved north and east from Grenville, extending the occupation zone.

At St. George’s, Grenada’s capital (Map 37), U.S.

helicopters carrying the American attack forces arrived in broad daylight and were met by heavy anti-aircraft fire from Grenadian ground forces that had been alerted by the landings earlier in other parts of the island. However, the American helicopters landed

successfully at St. George’s. There, U.S. Navy SEALs who were tasked to rescue Grenada’s Governor General at his residence were pinned down by enemy fire. A U.S. air attack on two Grenadian military garrisons in the capital suffered some helicopter gunship losses and many U.S. soldier casualties. That night, U.S. Marines were landed amphibiously north of St. George’s. The Marines soon relieved the beleaguered U.S. Navy SEALs and helped rescue the Governor General, who was flown out to safety.

By morning of the invasion’s second day, American air and ground attacks, including armored and artillery units that had been brought to the front, overcame fierce resistance from the two Grenadian garrisons at St. George’s. More American medical students were found at the Grand Anse campus located six kilometers south of the capital; they were

flown out to safety by U.S. military helicopters.

By the third day, Grenadian resistance had ceased, with fighting ending in all combat sectors.

The American operation to capture Caviligny Barracks, however, met a bizarre accident when four U.S. helicopters crashed, killing many soldiers on board.

March 11, 2020

March 12, 1970 – Cambodian Civil War: Prime Minister Lon Nol demands that Vietnamese forces leave Cambodian territory within 72 hours

In September 1969, conservative politicians, frustrated at the continuing Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia, made plans to overthrow

Sihanouk. Then in March 1970, while Sihanouk was on a trip outside the country, anti-Vietnamese demonstrations broke out in Phnom Penh. The protests turned violent, with mobs entering and looting the embassies of North Vietnam and Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (the Viet Cong’s government-in-exile).

Taking advantage of the widespread anti-Vietnamese sentiment among Cambodians, Prime Minister Lon Nol closed down Sihanoukville to

communist-flagged vessels. Lon Nol also voided Sihanouk’s trade agreement with North Vietnam, and on March 12, 1970, he demanded that Vietnamese forces leave Cambodian territory within 72 hours.

Lon Nol initially was unwilling to support the plot to overthrow Sihanouk. But on March 18, 1970, he convened the National Assembly, which in a 92-0 non-confidence vote, declared its ceasing recognition of Sihanouk as Cambodia’s head of state, and

deposed him. Subsequently in October 1970, Lon Nol declared the end of the Kingdom of Cambodia. In its place, he formed the Khmer Republic, taking the position of president. The new regime was firmly pro-American, and U.S. advisers, weapons, and military equipment soon arrived.

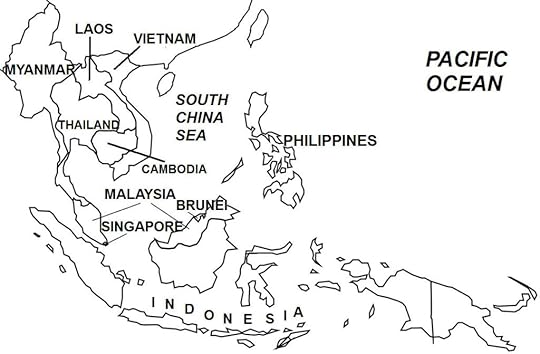

Southeast Asia in the 1960s.

(Taken from Cambodian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

Meanwhile in Cambodia, Sihanouk sought to stay away from the conflict in Vietnam by maintaining a policy of non-alignment (which he called “extreme neutrality”) for Cambodia. He took part in the 1955 Bandung Conference (in Bandung, Indonesia) which led to the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement.

But by the second half of the 1950s, Sihanouk had also established friendly ties with China,

particularly to serve as a deterrent against Cambodia’s historical ethnic enemies, the Thais and Vietnamese, and also because he viewed the U.S. presence in Indochina as temporary, when considered over the long term, just as it had been for the French.

In an agreement made in February 1956, Cambodia

received economic aid from China. In 1958, Cambodia and China established diplomatic relations. Two years later, 1960, they signed the Treaty of Friendship and Non-aggression.

Thailand and South Vietnam, Cambodia’s

neighbors on either side, viewed the Cambodian government with deep suspicion, believing Sihanouk to be aligning with the communists. Then when two attempts were made on Sihanouk (in January and August 1959), he accused South Vietnam of plotting his assassination.

Invariably intertwined with Cambodia’s foreign relations were the ancient Cambodians’ historical animosity with their neighbors, the Thais and Vietnamese. In particular, during the 1800s, the Vietnamese had sought to eradicate the Indian-influenced Cambodian culture and introduce the Chinese-influenced Vietnamese culture to the Cambodians. The Vietnamese also annexed a large section of Khmer territory, specifically the Mekong Delta of present-day Vietnam. As a result, later-day Cambodians viewed the Vietnamese with suspicion and resentment, and these sentiments would play a

part in the coming civil war.

While establishing diplomatic relations with China, Sihanouk also maintained friendly ties with the West, particularly the United States. In 1955, Cambodia and the United States signed a military agreement where the U.S. government provided weapons to Cambodia’s military (which was called FARK, Forces Armées Royales Khmères). By the early 1960s, the Americans were providing military support equivalent to 30% of Cambodia’s defense appropriations.

In the mid-1960s, Cambodia’s neutrality was increasingly being undermined, first because North Vietnam had extended the Ho Chi Minh Trail (its logistical route to South Vietnam) across eastern Cambodia, and second, to counteract this North Vietnamese action, U.S. planes conducted surveillance and bombing operations along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and South Vietnamese forces occasionally entered Cambodia to pursue the Viet Cong.

Sihanouk and his declared non-alignment also came under U.S. scrutiny when he signed agreements with China and North Vietnam. In these agreements, Cambodia allowed the following stipulations: that the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong could occupy eastern Cambodia; that the port of Sihanoukville (Figure 7) would be opened to communist bloc ships that supplied war materials for the Viet Cong; and that the North Vietnamese would be allowed to use a road network across Cambodia to transport the supplies from Sihanoukville to South Vietnam (this

route became known in the West as the Sihanouk Trail).

In the early 1960s, as Cambodia moved toward establishing closer ties with China and North Vietnam, so did its relations with the United States deteriorate. The decline in Cambodian-American relations resulted from a number of factors: First, Sihanouk began to fear that a stronger Cambodian military (which was supplied with U.S. weapons), would soon threaten his government; Second, he believed that the United States was involved in the assassination plots against him; and Third, he suspected that the U.S. military were supporting the Khmer Serei, a right-wing guerilla group that was fighting an insurgency war against the Cambodian government. In November 1963, Sihanouk cut U.S. aid to Cambodia, and in May 1965, diplomatic relations between the two countries broke down.

In the September 1966 Cambodian parliamentary elections, right-wing candidates of the ruling Sangkum party won most of the seats in the National Assembly, leading to the Cambodian government shifting to the right. Pro-U.S. General Lon Nol became the new Prime Minister. Also by the second half of the 1960s, Sihanouk again turned his foreign policy toward the West, for the following reasons: First, Cambodia’s relations with China and North Vietnam did not produce clear economic benefits to Cambodia; Second, the loss of American aid was negatively affecting the Cambodian economy; and Third, this new foreign policy would balance the rightist and leftist elements in Cambodia’s deeply politicized government. In June 1969, following the U.S. government’s promise to respect Cambodia’s

neutrality and sovereignty, diplomatic relations between Cambodia and the United States were restored.

By this time, the right-wing faction in the Cambodian government had lost confidence in Sihanouk’s capacity to resolve the country’s many political and economic problems. In September 1969, conservative politicians, frustrated at the continuing

Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia, made plans to overthrow Sihanouk. Then in March 1970, while Sihanouk was on a trip outside the country, anti-Vietnamese demonstrations broke out in Phnom Penh. The protests turned violent, with mobs

entering and looting the embassies of North Vietnam and Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (the Viet Cong’s government-in-exile).

Taking advantage of the widespread anti-Vietnamese sentiment among Cambodians, Prime Minister Lon Nol closed down Sihanoukville to

communist-flagged vessels. Lon Nol also voided Sihanouk’s trade agreement with North Vietnam, and on March 12, 1970, he demanded that Vietnamese forces leave Cambodian territory within 72 hours.

Lon Nol initially was unwilling to support the plot to overthrow Sihanouk. But on March 18, 1970, he

convened the National Assembly, which in a 92-0 non-confidence vote, declared its ceasing recognition of Sihanouk as Cambodia’s head of state, and

deposed him. Subsequently in October 1970, Lon Nol declared the end of the Kingdom of Cambodia. In its place, he formed the Khmer Republic, taking the position of president. The new regime was firmly pro-American, and U.S. advisers, weapons, and military equipment soon arrived.

Meanwhile, the deposed Sihanouk took up residence in Beijing, China, where Mao Zedong’s government granted him political asylum. In Phnom

Penh in the days after the coup, tens of thousands of Cambodians, mainly peasants with whom Sihanouk was extremely popular, launched large protest demonstrations in Kampong Cham, Takeo, and Kampot Provinces. Some 40,000 farmers marched on Phnom Penh demanding that Sihanouk be restored to power. The demonstrations turned violent when security forces dispersed the crowds, killing hundreds of protesters. Violence also broke out against ethnic Vietnamese living in Cambodia. In the countryside, Cambodians massacred hundreds of ethnic Vietnamese.

Lon Nol launched a program to strengthen Cambodia’s armed forces. Many civilians signed up

to join the military, with many recruits motivated by the sole desire to fight and expel the Vietnamese Army from eastern Cambodia. As a result of heavy recruitment, the Cambodian Army grew from 35,000 in early 1970, to a peak of 250,000 in 1974.

Sihanouk’s overthrow and the emergence of a pro-U.S. government would have profound effects for Cambodia, particularly with regards to the ongoing Vietnam War. The United States, long restrained by Cambodia’s official neutrality, increased bombing operations on North Vietnamese Army/Viet Cong bases in eastern Cambodia, this aerial campaign extending from May 1970 – August 1973. U.S. bombing had actually started one year earlier (under Operation Menu), in March 1969, in which Sihanouk may have given his tacit consent. The bombings were very intense, in total, over 500,000 tons of ordnance were dropped (equivalent to 30% of the 1.5 million tons of all bombs that U.S. planes dropped in Europe

during World War II). Various estimates place the number of Cambodian civilian casualties caused by American bombing at between 40,000 and 150,000 killed. The U.S. bombings, together with the ground

fighting, destroyed much of eastern Cambodia, forcing hundreds of thousands of civilians to flee to Phnom Penh, the capital. Phnom Penh soon grew to a population of 2 – 2½ million by 1975, from 600,000 in 1970.

In April 1970, in a major offensive known as the Cambodian Campaign, American and South Vietnamese forces crossed the border from South Vietnam into eastern Cambodia aimed at destroying North Vietnamese Army/Viet Cong military bases and supply depots along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The success of this operation was deemed crucial to the withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Vietnam in line with the American de-escalation from the Vietnam War. In the Cambodian Campaign, American and South Vietnamese forces killed some 10,000 North Vietnamese/Viet Cong troops, and destroyed enemy bases and captured large quantities of weapons and supplies in underground storage bunkers. Even then, the operation was only partially successful, as most of the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong forces had earlier fled deeper into Cambodia.

March 10, 2020

March 11, 1969 – Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Demonstrators in Beijing besiege the Soviet Embassy in protest for the attack on the Chinese Embassy in Moscow

Fighting broke out between Soviet and Chinese units on on Damansky/Zhenbao Island on March 2, 1969. Following this incident, sensationalist news reports by the media stirred up the general population in both countries. On March 3, 1969 in Beijing, large protests were held outside the Soviet Embassy, and Soviet diplomatic personnel were harassed. In the Soviet Union, demonstrations were held in Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. In Moscow,

angry crowds hurled stones, ink bottles, and paint at the Chinese Embassy.

On March 11, 1969 in Beijing, demonstrators besieged the Soviet Embassy in protest for the attack on the Chinese Embassy. Then when Soviet media

reported that captured Russian soldiers during the Damansky/Zhenbao incident had been tortured and executed, and their bodies mutilated, large demonstrations consisting of 100,000 people broke out in Moscow. Other mass assemblies also occurred in other Russian cities.

On March 15, 1969, a second (and larger) clash broke out in Damansky/Zhenbao Island, where both sides sent a force of regimental strength, or some 2,000-3,000 troops. The Chinese claimed that the Soviets fielded one motorized infantry battalion, one tank battalion, and four heavy-artillery battalions, or a total of over 50 tanks and armored vehicles, and scores of artillery pieces. The two sides again claimed victory in the 10-hour battle, and also accused the other side of firing the first shots. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

China had a long-standing border dispute with the Soviet Union, which was inherited by the Soviet Union’s successor states, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

(Taken from Sino-Soviet Border Conflict – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background

Historically, the communist parties of Russia and China had not had close ties, and were even hostile to each other. During the early years of the Chinese

Communist Party, in 1923, the Soviet government under Vladimir Lenin encouraged the Chinese communists to join the non-communist Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalists). Then in World War II, Stalin urged Mao to form an alliance with Chiang Kai-shek to fight the Japanese. In the 1930s, Mao began to view traditional Marxism, like that applied in the Soviet Union, as relevant only in the industrialized countries, and not consistent with China’s agricultural society. Mao soon developed a new branch of Marxism called Maoism, which stated that in agricultural societies, the revolutionary struggle should be led by the peasants.

In September 1963-July 1964, Mao published a series of papers condemning Khrushchev and Soviet policies. In October 1964, Leonid Brezhnev succeeded as the new leader of the Soviet Union, and

overturned some of the liberal reforms of his predecessor, although he generally continued to implement party policies. Brezhnev adopted a hard-line stance on the West, which did not lead to improved Sino-Soviet relations. Instead, ties between the two communist countries continued to decline. By 1963, the Sino-Soviet split involved the long-standing territorial dispute along the two countries’ poorly defined 4,380-kilometer shared border. In July 1964, Mao stated that the territory of the Soviet Union was excessive, and that Soviet regions of Lake Baikal, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, and Kamchatka formerly belonged to China. Mao then said that China had “not yet presented our bill for this list” to the Soviet Union.

China then declared that two 19th century treaties with the Soviet Union, the Treaty of Aigun (1858) and the Convention of Peking (1860), were “unequal treaties”, in that the then ruling powerful Russian Empire had forced the war-weakened Chinese Qing Dynasty to cede one million square kilometers of territory in Manchuria and Siberia to Russia. Mao’s government also stated that through

other “unequal treaties” which the Qing court was forced to sign in the 19th century, China lost some 500,000 square kilometers of land in its western

border, lands which now are part of the Soviet Union.

The Chinese government soon made the clarification that by bringing up the matter of “unequal treaties” with the Soviet Union, China did not seek to reclaim these territories, but that it wanted the Soviet Union to acknowledge that the treaties indeed were unjust, and that the two sides must negotiate a final border agreement on the basis of present-day boundaries. In this respect, for China, the disputed territory amounted to only 35,000 square kilometers along the common border. And of this figure, 34,000 square kilometers were located in the western side bordering the Soviet Socialist

Republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Another 1,000 square kilometers were located along the eastern side running along the length of three rivers: the Argun, Amur, and Ussuri (Figure 20).

Both the Treaty of Aigun and the Convention of Peking, which codified the border along the eastern side, stipulated that the Sino-Russian border was located on the Chinese side running the whole length of the three rivers, thus giving the Russians full sovereignty along these rivers, including the many hundreds of islands located therein. China

wanted to negotiate a readjustment of this river border, and proposed that the new border line be placed at the midpoint of the rivers. The Soviet Union rejected any readjustments, stating that the existing treaties had already fixed the border.

Furthermore, the Soviet Union denied that the 19th century treaties were “unequal treaties”, and countered by stating that the Chinese rulers themselves were territorially ambitious at that

time. The Soviets also stated that in recently signed land treaties between China and the Soviet Union, Mao’s government had not brought up the matter of the earlier “unequal treaties” in these areas, and

thus constituted a tacit acknowledgment of Soviet sovereignty of these areas. In February 1964, the two sides held border talks, which collapsed later that year when Mao raised new criticisms against the Soviet government.

Both sides now increased their forces at the border, raising tensions. The Soviet government also

strengthened its relations with Mongolia (a socialist client state of the Soviet Union). In January 1966, the two countries signed a military alliance that allowed Soviet troops to deploy in Mongolia to help defend the country against a possible Chinese attack.

In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, where he purged his political rivals and took full control of the Chinese Communist Party. But the Cultural Revolution brought widespread turmoil in China, and also exacerbated the ideological clash between China and the Soviet Union, increasing tensions between them.

In August 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, and overthrew the socialist government there that had tried to implement liberal reforms. Mao saw this aggression as one which the Soviets could potentially undertake against China. By the mid-1960s, the Soviet-Chinese border was heavily militarized, and hundreds of skirmishes took place, which increased in frequency in 1968 in the highly volatile eastern border region. Soviet soldiers used physical force to remove Chinese fishermen and worker groups, as well as Chinese military patrols, which had entered the river islands. In January 1968, China filed a diplomatic protest when Soviet troops attacked and killed Chinese workers in Qiliqin Island.

March 9, 2020

March 10, 1979 – Uganda-Tanzania War: Libyan forces repel an attack by the Tanzanian Army near the Lukaya Swamps

Ugandan leader General Idi Amin pleaded for assistance from

his friend, Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader.

Gaddafi responded by dispatching 3,000 Libyan soldiers, supported with

tanks, artillery, and some planes. On

their arrival in Uganda,

the Libyan force was sent directly to battle.

On March 10, 1979, the Libyans threw back a Tanzanian force that was

advancing toward the Lukaya Swamps. The

following day, two Tanzanian brigades attacked the Libyans from the north and

south of Lukaya. Caught by surprise, the

Libyans were routed and broke out in a run.

The Tanzanians advanced unopposed through the Masaka-Kampala Road

and passed through towns and villages where large crowds welcomed them as

liberators. The Tanzanians captured

Mpigi, as well as Entebbe,

where the Libyans were overwhelmed after initially putting up some resistance.

On April 10, 1979, the Tanzanian Army entered and occupied Kampala, Uganda’s

capital, practically ending the war except for some small-scale fighting that

would continue for the next few months.

General Amin earlier had fled into exile, first to Libya, and then Saudi Arabia, where he was welcomed

as a guest by his friend, King Faisal I.

General Amin would live in Saudi Arabia until his death in

2003.

After the war, the remaining Libyan forces were allowed to

leave Uganda, and departed

by way of Kenya. For a time, the Tanzanian Army remained in Uganda to carry

out peace-keeping duties until security was restored, and to oversee the

Ugandan political system’s return to democracy.

However, Uganda’s

transition to democracy was turbulent and wracked by bitter in-fighting and a

power struggle among factions of the coalition that had helped to overthrow

General Amin. Uganda, a country traditionally

divided by ethnic loyalties, saw the re-emergence of regional political

affiliations at the expense of a collective Ugandan nationalism.

In general elections held in December 1980, former President

Obote returned to power by winning the presidential race. But charges of election fraud, the fractious

political climate, and the continued militarized environment after the war, led

to the formation of many armed groups that would lead the country into a new

round of conflict, the Ugandan Bush War (next

article).

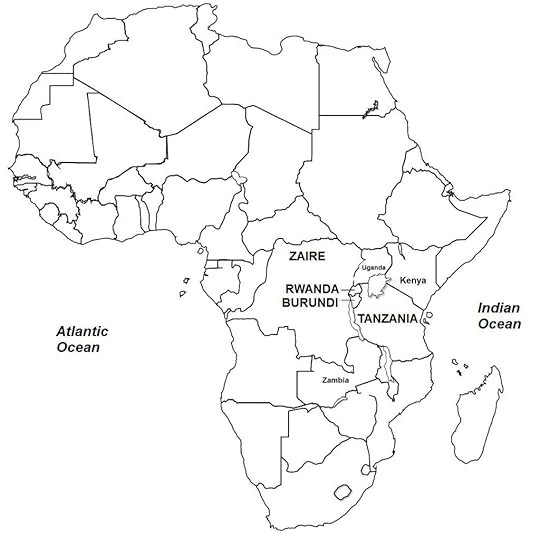

Uganda, Tanzania, and nearby countries.

Uganda, Tanzania, and nearby countries.(Taken from Uganda-Tanzania War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background In

January 1971, Ugandan President Milton Obote was overthrown in a military coup

while he was on a foreign mission.

Fearing for his safety, he did not return to Uganda

but flew to Tanzania, Uganda’s

southern neighbor, where Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere gave him political

sanctuary. President Nyerere’s action,

however, was not well received by General Idi Amin, the leader of the Ugandan

coup, and relations between the two countries deteriorated.

In Uganda,

General Amin took over power and established a military dictatorship, and named

himself the country’s president and head of the armed forces. He carried out a purge of military elements

that were perceived as loyal to the former regime. As a result, thousands of officers and

soldiers were executed. General Amin

then formed a clique of staunchly loyal military officers whom he promoted

based on devotion and subservience to his government rather than on merit and

competence. In lieu of local civilian

governments, General Amin set up regional military commands led by an army

officer who held considerable power.

Corruption and inefficiency soon plagued all levels of government.

Military officers who had been bypassed or demoted from

their positions became disgruntled. Many

of these officers, including thousands of soldiers, crossed the border to Tanzania and

met up with ex-President Obote and other exiled Ugandan leaders. Together, they formed an armed rebel group

whose aim was to overthrow General Amin.

The rebels were well received by the Tanzanian government, which

provided them with military and financial support.

In 1972, the rebels launched an attack in southern Uganda and came to within the town of Masaka where they tried

to incite the local population to revolt against the Ugandan government. No revolt took place, however. General Amin sent his forces to Masaka, and

in the fighting that followed, the rebels were thrown back across the border.

Ugandan planes pursued the rebels in northern Tanzania, but

attacked the Tanzanian towns of Bukoba and Mwanza, causing some

destruction. The Tanzanian government

filed a diplomatic protest and increased its forces in northern Tanzania. Tensions rose between the two countries.

Through mediation efforts of Somalia,

however, war was averted and the two countries agreed to deescalate the

tension, and withdrew their forces a distance of ten kilometers from their

common border.

The insurgency provoked General Amin into intensifying his

suppressive policies, especially against the ethnic groups of his political

enemies. All social classes from these

rival ethnicities were targeted, from businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and the

clergy, to workers, peasants, and villagers.

Even members of General Amin’s Cabinet and top military officers were

not spared. General Amin’s secret

police, called the State Research Bureau, carried out numerous summary

executions and forced disappearances, as well as tortures and arbitrary

arrests. During General Amin’s

eight-year reign in power, an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Ugandans were

killed.

General Amin also expelled the ethnic South Asian community

from Uganda. These South Asian Ugandans were the

descendants of contract workers from the Indian subcontinent who had been

brought to Uganda

during the British colonial period.

South Asians comprised only 1% of the total population but were

predominantly merchants, traders, landowners, and industrialists who held a

disproportionately large share of Uganda’s economy; other South

Asians were wealthy professionals, held clerical jobs, or were tradesmen.

After the expulsion, the South Asians’ businesses and

properties were seized by the government and distributed to the general

population in line with General Amin’s program of promoting the social and

economic advancement of black Ugandans.

However, many of the assets ended up being owned by General Amin’s

military and political associates, most of whom had no knowledge of running a

business. Soon, most of these operations

failed and closed down.

As a result, Uganda’s

economy deteriorated. Poverty and

unemployment soared, and basic commodities became non-existent or in very low

supply. Coffee beans, the country’s main

export product, were required by law to be sold to the government. But as the government failed to pay or

underpaid the farmers, the smuggling of coffee beans to nearby Kenya (where

prices were much higher) became widespread and carried out by farmers and

traders at the risk of a government-issued shoot-to-kill order against

violators. Eventually, however, coffee

bean smuggling operations came under the control of the army commanders

themselves.

Initially, the Western media was fascinated by General

Amin’s idiosyncratic behavior and outrageous statements, making the Ugandan

leader extremely popular in foreign news reports. But as his brutal regime and human rights

record became known, Britain

and the United States, both Uganda’s

traditional allies, distanced themselves and ended diplomatic relations with

General Amin’s government. Uganda then turned to the Soviet

Union, which soon became the Ugandan government’s main supplier of

weapons. Uganda

also strengthened military ties with Libya

and diplomatic relations with Saudi

Arabia.

By 1978, Uganda

had become isolated diplomatically from much of the international

community. Despite outward appearances,

the government was experiencing growing dissent from within. A year earlier, General Amin was nearly

ousted in a coup carried out by high-ranking government officials, underscoring

the growing political opposition to his rule.

Then in November 1978, Uganda’s Vice-President, Mustafa

Adrisi, was wounded in a car accident, which might have been an assassination

attempt on his life. Adrisi’s military

supporters, which included some elite units, broke out in mutiny.

March 8, 2020

March 9, 1978 – Ogaden War: As Ethiopian-Cuban forces advance into the Ogaden, the Somalis withdraw from the region

Ethiopian-Cuban forces advanced toward the strategic Kara Marda Pass, where the Somalis had built a defensive line. Bypassing the Pass through the north and then turning east, one Ethiopian-Cuban unit joined with another force approaching from the west to launch a pincers attack on the Somali defenders. By early March 1978, the Ethiopian-Cuban forces had captured the Kara Marda Pass and were moving rapidly east toward the Ogaden plains. As fears of an Ethiopian invasion of Somalia increased, on February 9, 1978, Somali President Barre issued a general mobilization and placed the country in a state of emergency. In early March 1978, Ethiopian-Cuban forces attacked Jijiga, where remnants of the Somali Army-WSLF forces had organized a last major defense of the Ogaden. But their lines quickly fell apart under the weight of the armored, artillery, and air attacks. The Battle of Jijiga was a crushing defeat for the Somali Army, with some 3,000 soldiers killed. On March 9, 1978, the Somali government ordered a general retreat from the Ogaden; by this time, however, the Somali Army, now abandoning their weapons and equipment in the field, and together with the WSLF fighters, and tens of thousands of civilians, were making a hasty, chaotic retreat toward the Somali border. Further Ethiopian-Cuban advances across the Ogaden recaptured other areas: Degehabur (March 6), Filtu (March 8), Delo (March 12), and Kelafo (March 13).

The Ethiopian government now faced the enticing prospect of advancing right into Somalia. Ultimately, the Soviet Union prevailed upon the Ethiopian Derg regime to stop at the border; on March 23, 1978, with much of the fighting dying down, Ethiopia declared victory and the war over.

Estimates of combat casualties are: over 6,000 killed and 10,000 wounded in the Ethiopian Army, and over 6,000 killed and 2,000 wounded in the Somali Army. Some 400 Cubans and 30 Soviets also lost their lives. A combined 50 planes and over 300 tanks and armored vehicles also were destroyed. Furthermore, some 750,000 Ogaden inhabitants (mainly ethnic Somali and Oromo) fled from their homes and ended up as refugees in Somalia.

(Excerpts taken from Ogaden War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

In December 1950, with Allied approval, the United Nations granted Italy a trusteeship over Italian Somaliland on the condition that Italy grants the territory its independence within ten years. On June 26, 1960, Britain granted independence to British Somaliland, which became the State of Somaliland, and a few days later, Italy also granted independence to the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland). On July 1, 1960, the two new states merged to form the Somali Republic (Somalia).

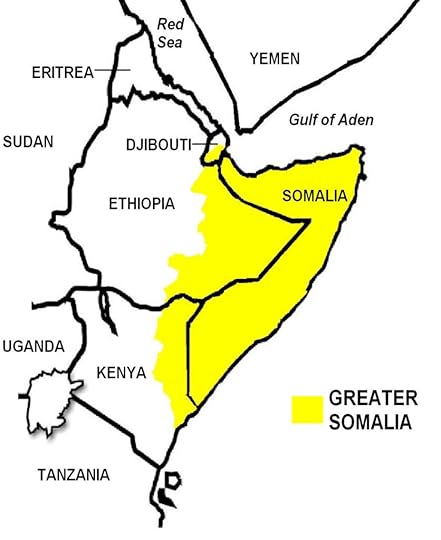

Greater Somalia.

Greater Somalia.The newly sovereign enlarged state had as its primary foreign affairs mission the fulfillment of “Greater Somalia” (also known as Pan-Somalism; Figure 29), an irredentist concept that sought to bring into a united Somali state all ethnic Somalis in the Horn of Africa who currently were residing in neighboring foreign jurisdictions, i.e. the Ogaden region in Ethiopia, Northern Frontier District (NFD) in Kenya, and French Somaliland. Somalia officially did not claim ownership to these foreign territories but desired that ethnic Somalis in these regions, particularly where they formed a population majority, be granted the right to decide their political future,

i.e. to remain with these countries or to secede and merge with Somalia.

Nationalist Somalis in Kenya and Ethiopia, desiring to be joined with Somalia, soon launched guerilla insurgencies. In the Ogaden region, many guerilla groups organized, the foremost of which was

the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), founded in 1960, just after Somalia gained its independence. The Somali government began to build its armed forces, eventually setting as a goal a force of about

20,000 troops that it deemed was powerful enough to realize the dream of Greater Somalia. But constrained by economic limitations, Somalia sought the assistance of various Western powers, particularly the United States, but the latter only promised to provide military resources for a 5,000-strong armed forces, which it deemed was sufficient for Somalia to defend its borders against external threats.

The Somali government then turned to communist states, particularly the Soviet Union; although these countries’ Marxist ideology ran

contrary to its own democratic institution, Somalia viewed this as a means to be political self-reliant and not be too dependent on the West, and to court

both sides in the Cold War. Thus, for nearly two decades after gaining its independence, Somalia received military support from both western and communist countries.

In 1962, the Soviet Union provided Somalia with a substantial loan under generous terms of repayment, allowing the Somali government to build in earnest an offense-oriented armed forces; subsequent Soviet loans and military assistance led to the perception in the international community that Somalia fell under the Soviet sphere of influence, bolstered further as Soviet planes, tanks, artillery pieces, and other military hardware were supplied in large quantities to the Somali Army Forces.

Tensions between Ethiopian security forces and the Ogaden Somalis sporadically led to violence that soon deteriorated further with Somali Army units intervening, leading to border skirmishes between Ethiopian and Somali regular security units. Large-scale fighting by both sides finally broke out in February 1964, which was triggered by a Somali revolt in June 1963 at Hodayo. Somali ground and air units came in support of the rebels but Ethiopian planes gained control of the skies and attacked frontier areas, including Feerfeer and Galcaio. Under mediation efforts provided by Sudan representing the Organization of African Unity (OAU), in April 1964, a

ceasefire was agreed that imposed a separation of forces and a demilitarized zone on the border. In the aftermath, in late 1964, Ethiopia entered into a mutual defense treaty with Kenya (which also was facing a rebellion by local ethnic Somalis supported by the Somali government) in case of a Somali invasion; this treaty subsequently was renewed in 1980 and then in 1987.

On October 21, 1969, a military coup overthrew Somalia’s democratically elected civilian government and in its place, a military junta called the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) was set up and led by General Mohamed Siad Barre, who succeeded as president of the country. The SRC suspended the constitution, banned political parties, and dissolved parliament, and ruled as a dictatorship. The country was renamed the Somali Democratic Republic. Exactly one year after the coup, on October 21, 1970, President Barre declared the country a Marxist state, although a form of syncretized ideology called “scientific revolution” was implemented, which combined elements of Marxism-Leninism, Islam, and Somali nationalism. The SRC forged even closer

diplomatic and military ties with the Soviet Union,

which led in July 1974 to the signing of the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, where the Soviets increased military support to the Somali Army. Earlier in 1972, under a Somali-Soviet agreement, the Russians developed the Somali port of Berbera,

converting it into a large naval, air, and radar and communications facility that allowed the Soviets to project power into the Middle East, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf. The Soviets also established many new military airfields, including those in Mogadishu, Hargeisa, Baidoa, and Kismayo.

Under pressure from the Soviet government to form a “vanguard party” along Marxist lines, in July 1976, President Barre dissolved the SRC which he replaced with the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), whose Supreme Council (politburo) formed the new government, with Barre as its Secretary General. The SRSP, as the sole legal party, was intended to be a civilian-run entity to replace the

military-dominated SRC; however, since much of the SRC’s political hierarchy simply moved to the SRSP, in practice, not much changed in governance and Barre

continued to rule as de facto dictator.

With a greatly enhanced Somali military capability, President Barre pressed irredentist aspirations for Greater Somalia, stepping up political rhetoric against Ethiopia and spurning third-party mediations to resolve the emerging crisis. Then in the mid-1970s, favorable circumstances allowed Somalia to implement its irredentist ambitions.

During the first half of 1974, widespread military and civilian unrest gripped Ethiopia, rendering the government powerless. In September 1974, a group of junior military officers called the “Coordinating

Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army”, which simply was known as “Derg” (an Ethiopian word meaning “Committee” or “Council”), seized power after overthrowing Ethiopia’s long-ruling aging monarch, Emperor Haile Selassie. The Derg succeeded in power, dissolved the Ethiopian parliament and abolished the constitution, nationalized rural and urban lands and most industries, ruled with absolute powers, and began Ethiopia’s gradual transition from an absolute monarchy to a Marxist-Leninist one-party state.

Ethiopia traditionally was aligned with the West, with most of its military supplies sourced from the United States. But with its transition toward socialism, the Derg regime forged closer ties with the Soviet Union, which led to the signing in December 1976 of a military assistance agreement. Simultaneously, Ethiopian-American relations

deteriorated, and with U.S. President Jimmy Carter criticizing Ethiopia’s poor human rights record, in April 1977, the Derg repealed Ethiopia’s defense treaty with the United States, refused further American assistance, and expelled U.S. military personnel from the country. At this point, both Ethiopia and Somalia lay within the Soviet sphere and thus ostensibly were on the same side in the Cold War, but a situation that was unacceptable to President Barre with regards to his ambitions for Greater Somalia.

In the aftermath of the Derg’s seizing power, Ethiopia experienced a period of great political and security unrest, as the government battled Marxist groups in the White Terror and Red Terror, regional

insurgencies that sought to secede portions of the country, and the Derg itself racked by internal power struggles that threatened its own survival. Furthermore, the Derg distrusted the aristocrat-dominated military establishment and purged the ranks of the officer corps; some 30% of the officers were removed (including 17 generals who were

executed in November 1974). At this time, the Ogaden insurgency, led by the WSLF and other groups, also increased in intensity, with Ethiopian military outposts and government infrastructures

subject to rebel attacks. Just a few years earlier, President Barre did not provide full military support to the Ogaden rebels, encouraging them to seek a negotiated solution through diplomatic channels and even with Emperor Haile Selassie himself. These efforts failed, however, and with Ethiopia sinking into crisis, President Barre saw his chance to step in.

March 8, 1978 – Ogaden War: Ethiopian-Cuban forces recapture Filtu

In March 1978, Ethiopian-Cuban forces continued their advance into the Ogaden region, recapturing other areas: Degehabur (March 6), Filtu (March 8), Delo (March 12), and Kelafo (March 13).

The Ethiopian government now faced the enticing prospect of advancing right into Somalia. Ultimately, the Soviet Union prevailed upon the Ethiopian Derg regime to stop at the border; on March 23, 1978, with much of the fighting dying down, Ethiopia declared victory and the war over.

Estimates of combat casualties in the Ogaden War are: over 6,000 killed and 10,000 wounded in the Ethiopian Army, and over 6,000 killed and 2,000

wounded in the Somali Army. Some 400 Cubans and 30 Soviets also lost their lives. A combined 50 planes and over 300 tanks and armored vehicles also were

destroyed. Furthermore, some 750,000 Ogaden inhabitants (mainly ethnic Somali and Oromo) fled from their homes and ended up as refugees in Somalia.

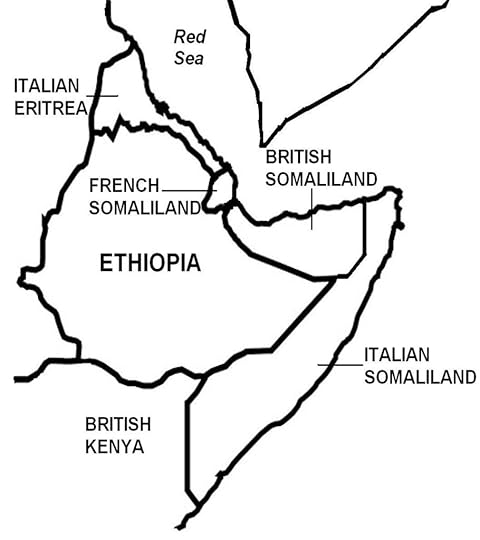

French Somaliland, British Somaliland, and Italian Somaliland.

(Excerpts taken from Ogaden War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

In December 1950, with Allied approval, the United Nations granted Italy a trusteeship over Italian Somaliland on the condition that Italy grants the territory its independence within ten years. On June 26, 1960, Britain granted independence to British Somaliland, which became the State of Somaliland, and a few days later, Italy also granted independence to the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland). On July 1, 1960, the two new states merged to form the Somali Republic (Somalia).

Greater Somalia.

The newly sovereign enlarged state had as its primary foreign affairs mission the fulfillment of “Greater Somalia” (also known as Pan-Somalism; Figure 29), an irredentist concept that sought to bring into a united Somali state all ethnic Somalis in the Horn of Africa who currently were residing in neighboring foreign jurisdictions, i.e. the Ogaden region in Ethiopia, Northern Frontier District (NFD) in Kenya, and French Somaliland. Somalia officially did not claim ownership to these foreign territories but desired that ethnic Somalis in these regions, particularly where they formed a population majority, be granted the right to decide their political future,

i.e. to remain with these countries or to secede and merge with Somalia.

Nationalist Somalis in Kenya and Ethiopia, desiring to be joined with Somalia, soon launched guerilla insurgencies. In the Ogaden region, many guerilla groups organized, the foremost of which was

the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), founded in 1960, just after Somalia gained its independence. The Somali government began to build its armed forces, eventually setting as a goal a force of about 20,000 troops that it deemed was powerful enough to realize the dream of Greater Somalia. But constrained by economic limitations, Somalia sought the assistance of various Western powers, particularly the United States, but the latter only promised to provide military resources for a 5,000-strong armed forces, which it deemed was sufficient for Somalia to defend its borders against external threats.

The Somali government then turned to communist states, particularly the Soviet Union; although these countries’ Marxist ideology ran contrary to its own democratic institution, Somalia viewed this as a means to be political self-reliant and not be too dependent on the West, and to court

both sides in the Cold War. Thus, for nearly two decades after gaining its independence, Somalia received military support from both western and communist countries.

In 1962, the Soviet Union provided Somalia with a substantial loan under generous terms of repayment, allowing the Somali government to build in earnest an offense-oriented armed forces; subsequent Soviet loans and military assistance led to the perception in the international community that Somalia fell under the Soviet sphere of influence, bolstered further as Soviet planes, tanks, artillery pieces, and other military hardware were supplied in large quantities to the Somali Army Forces.

Tensions between Ethiopian security forces and the Ogaden Somalis sporadically led to violence that soon deteriorated further with Somali Army units intervening, leading to border skirmishes between Ethiopian and Somali regular security units. Large-scale fighting by both sides finally broke out in February 1964, which was triggered by a Somali revolt in June 1963 at Hodayo. Somali ground and air units came in support of the rebels but Ethiopian planes gained control of the skies and attacked frontier areas, including Feerfeer and Galcaio. Under mediation efforts provided by Sudan representing the Organization of African Unity (OAU), in April 1964, a

ceasefire was agreed that imposed a separation of forces and a demilitarized zone on the border. In the aftermath, in late 1964, Ethiopia entered into a mutual defense treaty with Kenya (which also was facing a rebellion by local ethnic Somalis supported by the Somali government) in case of a Somali invasion; this treaty subsequently was renewed in 1980 and then in 1987.

On October 21, 1969, a military coup overthrew Somalia’s democratically elected civilian government and in its place, a military junta called the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) was set up and led by General Mohamed Siad Barre, who succeeded as president of the country. The SRC suspended the constitution, banned political parties, and dissolved parliament, and ruled as a dictatorship. The country was renamed the Somali Democratic Republic. Exactly one year after the coup, on October 21, 1970, President Barre declared the country a Marxist state, although a form of syncretized ideology called “scientific revolution” was implemented, which combined elements of Marxism-Leninism, Islam, and Somali nationalism. The SRC forged even closer

diplomatic and military ties with the Soviet Union,

which led in July 1974 to the signing of the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, where the Soviets increased military support to the Somali Army. Earlier in 1972, under a Somali-Soviet agreement, the Russians developed the Somali port of Berbera,

converting it into a large naval, air, and radar and communications facility that allowed the Soviets to project power into the Middle East, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf. The Soviets also established many new military airfields, including those in Mogadishu, Hargeisa, Baidoa, and Kismayo.

Under pressure from the Soviet government to form a “vanguard party” along Marxist lines, in July 1976, President Barre dissolved the SRC which he replaced with the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), whose Supreme Council (politburo) formed the new government, with Barre as its Secretary General. The SRSP, as the sole legal party, was intended to be a civilian-run entity to replace the

military-dominated SRC; however, since much of the SRC’s political hierarchy simply moved to the SRSP, in practice, not much changed in governance and Barre

continued to rule as de facto dictator.

With a greatly enhanced Somali military capability, President Barre pressed irredentist aspirations for Greater Somalia, stepping up political rhetoric against Ethiopia and spurning third-party mediations to resolve the emerging crisis. Then in the mid-1970s, favorable circumstances allowed Somalia to implement its irredentist ambitions.

During the first half of 1974, widespread military and civilian unrest gripped Ethiopia, rendering the government powerless. In September 1974, a group of junior military officers called the “Coordinating

Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army”, which simply was known as “Derg” (an Ethiopian word meaning “Committee” or “Council”), seized power after overthrowing Ethiopia’s long-ruling aging monarch, Emperor Haile Selassie. The Derg succeeded in power, dissolved the Ethiopian parliament and abolished the constitution, nationalized rural and urban lands and most industries, ruled with absolute powers, and began Ethiopia’s gradual transition from an absolute monarchy to a Marxist-Leninist one-party state.

Ethiopia traditionally was aligned with the West, with most of its military supplies sourced from the United States. But with its transition toward socialism, the Derg regime forged closer ties with the Soviet Union, which led to the signing in December 1976 of a military assistance agreement. Simultaneously, Ethiopian-American relations

deteriorated, and with U.S. President Jimmy Carter criticizing Ethiopia’s poor human rights record, in April 1977, the Derg repealed Ethiopia’s defense treaty with the United States, refused further American assistance, and expelled U.S. military personnel from the country. At this point, both Ethiopia and Somalia lay within the Soviet sphere and thus ostensibly were on the same side in the Cold War, but a situation that was unacceptable to President Barre with regards to his ambitions for Greater Somalia.

In the aftermath of the Derg’s seizing power, Ethiopia experienced a period of great political and security unrest, as the government battled Marxist groups in the White Terror and Red Terror, regional

insurgencies that sought to secede portions of the country, and the Derg itself racked by internal power struggles that threatened its own survival. Furthermore, the Derg distrusted the aristocrat-dominated military establishment and purged the ranks of the officer corps; some 30% of the officers were removed (including 17 generals who were

executed in November 1974). At this time, the Ogaden insurgency, led by the WSLF and other groups, also increased in intensity, with Ethiopian military outposts and government infrastructures

subject to rebel attacks. Just a few years earlier, President Barre did not provide full military support to the Ogaden rebels, encouraging them to seek a negotiated solution through diplomatic channels and even with Emperor Haile Selassie himself. These efforts failed, however, and with Ethiopia sinking into crisis, President Barre saw his chance to step in.

March 6, 2020

March 7, 1945 – World War II: U.S. forces seize the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine River

General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Allied High Command believed that attempting to cross the Rhine on a broad front would lead to heavy losses in personnel, and so they planned to concentrate Allied resources to force a crossing on the north in the British sector. Here also lay the shortest route

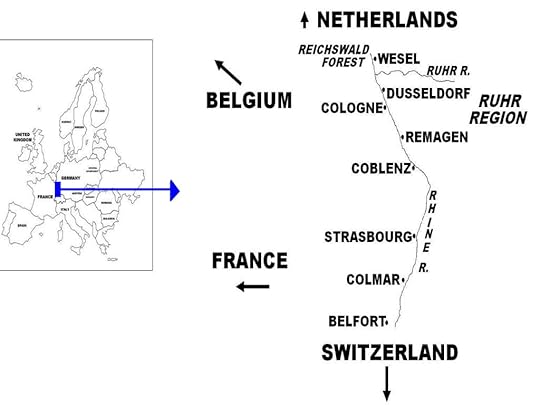

to Berlin, whose capture was definitely the greatest prize of the war. Beating out the Soviets to Berlin was greatly desired by Prime Minister Churchill and the British High Command, which at this point, the British and American planners believed could be achieved. With Allied focus on the British sector in the north, U.S. 12th and 6th Army Groups to the south were tasked with making secondary attacks in their sectors, tying down German troops there and thus aiding the British offensive.

Then on March 7, 1945, elements of U.S. 1st Army (part of U.S. 12th Army Group), upon reaching the Rhine’s west bank at Remagen, came upon a railroad bridge that was still standing and undefended. The Americans, taking advantage of this unexpected opportunity, rushed 25,000 troops in six divisions and large numbers of tanks and artillery pieces to the other side before the bridge collapsed on March 17. By then, U.S. 1st Army had built two tactical bridges, and had established a secure bridgehead on the eastern side some 40 km wide and 15 km long. The Germans, during their retreat, had systematically destroyed the fifty bridges across the whole length of the Rhine, but had failed to detonate the charges on the Remagen Bridge.

Battle for the Rhine River.

(Taken from Defeat of Germany in the West: 1944-1945 – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

On March 22, 1945, U.S. Third Army also crossed the Rhine, at Oppenheim and soon at two other points further north. General Patton, the U.S. 3rd Army commander, had rushed the crossings with little preparations, purposely to deny his rival General Montgomery the honor of being the first to force an opposed crossing of the Rhine. To the south, U.S. 7th Army crossed at Worms and the French at Germersheim.

On March 23, 1945, General Montgomery and 21st Army Group launched Operation Plunder, the forcing of the Rhine at Rees, Wesel, and south of the Lippe River. As was typical with General Montgomery, the operation was launched after thorough preparation and heavy concentration of

forces. The offensive was made with the largest airborne assault in history (Operation Varsity, involving 16,000 Allied paratroopers in 3,000 planes and gliders), and massive air and artillery bombardment of German positions before the amphibious crossing of the Rhine by the ground forces. The operation was a great success, overwhelming the German defenders. By late March 1945, the Allies had established a chain of bridgeheads on the Rhine’s eastern bank and were threatening to break out into the German heartland.

On March 28, 1945, General Eisenhower announced that the capture of Berlin was not anymore the main goal of the Western Allies, for the following reasons. First, the Soviet Red Army would clearly reach Berlin first, as it was poised at the Oder River just 30 miles (48 km) of the German capital, while the Western Allies at the Rhine were over 300 miles (480 km) from Berlin. Second, the breakthrough in the south would allow the Western Allies, particularly the U.S. forces, to rapidly fan out into the heart of Germany, which would break German morale and bring a quick end to the war.

Third, SHAEF priority was now to capture the Ruhr region, Germany’s industrial heartland, to destroy

German’s weapons production facilities and incapacitate Germany’s ability to continue the war.

Under these revised objectives, the three Allied Army Groups advanced into Germany and then into Central Europe. In the north, the British advanced toward Hamburg and the Elbe River, and met up with Soviet forces at Wismar in the Baltic coast on May 2, 1945, while the Canadians secured the Netherlands

and northern German coast. To the south of the British, on March 7, U.S. 9th and 1st Armies attacked the Ruhr region in a pincers movement, leading to the last large-scale battle in the Western Front. On April 4, the pincers closed, and U.S. forces systematically destroyed the trapped German Army Group B inside the Ruhr pocket. On April 21, the pocket was cleared and the Americans captured over 300,000 German

soldiers, this unexpected massive German defeat surprising the Allied High Command. As a result of this catastrophe, German Army Group B commander General Walther Model committed suicide, while concerted German defense of the Western Front effectively ceased. Other elements of U.S. 9th and 1st Armies had also advanced further east, and on April 25, 1945, contact was made between American and Soviet forces at the Elbe River.

Further to the south, General Patton’s 3rd Army advanced into western Czechoslovakia and southeast for eastern Bavaria and northern Austria. U.S.

6th Army Group (U.S. 7th Army and the French Army) turned south into Bavaria, Austria, and northern Italy, with the isolated German garrisons at Heilbronn, Nuremberg, and Munich putting up some stiff resistance before surrendering.

On April 30, 1945, Hitler committed suicide, and three days later, Berlin fell to the Red Army. As per Hitler’s last will and testament, governmental powers of the now crumbling German state passed on to Admiral Karl Doenitz, head of the German Navy, who at once took steps to end the war. On May 2, German forces in Italy and western Austria surrendered to the British, and two days later, the Wehrmacht in northwest Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark surrendered, also to the British, while

on May 5, German forces in Bavaria and southwest Germany surrendered to the Americans. At this time, isolated German units facing the Soviets were desperately trying to fight their way to Western Allied lines, hoping to escape the punitive wrath of the

Russians by surrendering to the Americans or British.

On May 7, 1945, General Alfred Jodl, German Armed Forces Chief of Operations, signed the instrument of unconditional surrender of all German forces at Allied headquarters in Reims, France. A few hours later, Stalin expressed his disapproval of certain aspects of the surrender document, as well as its

location, and on his insistence, another signing of Germany’s unconditional surrender was held in Berlin by General Wilhelm Keitel, chief of German Armed

Forces, with particular attention placed on the Soviet contribution, and in front of General Zhukov, whose forces had captured the German capital.

Shortly thereafter, most of the remaining German units surrendered to nearby Allied commands, including Army Group Courland in the “Courland Pocket”, Second Army Heiligenbeil and Danzig beachheads, German units on the Hel Peninsula in the Vistula delta, Greek islands of Crete, Rhodes, and

the Dodecanese, on Alderney Island in the English Channel, and in Atlantic France at Saint-Nazaire, La Rochelle, and Lorient.

March 5, 2020

March 6, 1975 – Iran-Iraq War: The Algiers Accord is signed, where Iran and Iraq settle their border dispute

By the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurds were holding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the First Iraqi-Kurdish War, separate article); negotiations collapsed and fighting broke out in April 1974, with the Iraqi

Kurds being supported militarily by Iran. In turn, Iraq incited Iran’s ethnic minorities to revolt, particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, Iranian Kurds, and Baluchs. Direct fighting between Iranian and Iraqi forces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iranians prevailing. Hostilities ended when the two countries signed the Algiers Accord on March 6, 1975, where Iraq yielded to Iran’s demand that the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; in exchange, Iran ended its support to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq was displeased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional military power, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues) during the second half of the 1970s. Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and even enjoyed a period of rapprochement. As a result of Iran’s assistance

in helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelled Ayatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iranian cleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.

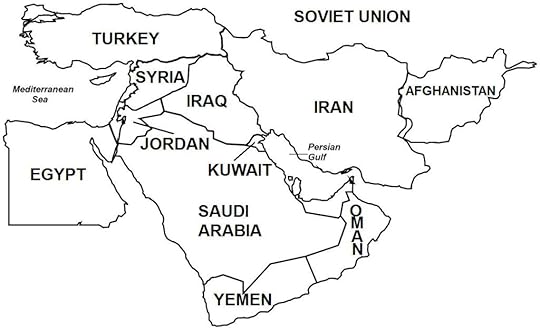

Iran, Iraq, and nearby countries.

(Taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

(continued)

However, Iranian-Iraqi relations turned for the worse towards the end of 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini was proclaimed as Iran’s absolute ruler. Each of the two rival countries resumed secessionist support for the various ethnic groups in the other country. Iran’s transition to a full Islamic State was opposed by the various Iranian ethnic minorities, leading to revolts

by Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchs. The Iranian government easily crushed these uprisings, except in Kurdistan, where Iraqi military support allowed the Kurds to fend off Iranian government forces until late 1981 before also being put down.

Ayatollah Khomeini, in line with his aim of spreading Islamic revolutions across the Middle East, called on Iraq’s Shiite majority to overthrow Saddam and his “un-Islamic” government, and establish an

Islamic State. In April 1980, a spate of violence attributed to the Islamic Dawa Party, an Iran-supported militant group, broke out in Iraq, where many Baath Party officers were killed and other high-ranking government officials barely escaped assassination attempts. In response, the Iraqi government unleashed repressive measures against radical Shiites, including deporting thousands who

were thought to be ethnic Persians, as well as executing Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, which drew widespread condemnation from several Muslim countries as the religious cleric was highly regarded in the wider Islamic community.

Throughout the summer of 1980, many border clashes broke out between forces of the two countries, increasing in intensity and frequency by

September of that year. As to the official start of the war, the two sides have different interpretations. The Iraqis cite September 4, 1980, when the Iranian Army carried out an artillery bombardment of Iraqi border towns, prompting Saddam two weeks later to unilaterally repeal the 1975 Algiers Accord and declare that the whole Shatt al-Arab lay within the territorial limits of Iraq.

September 22, 1980, however, is generally accepted as the start of the war, when Iraqi forces launched a full-scale air and ground offensive into Iran. Saddam believed that his forces were capable

of achieving a quick victory, his confidence borne by the following factors, all resulting from the Iranian Revolution. First, as previously mentioned, Iran

faced regional insurgencies from its ethnic minorities that opposed Iran’s adoption of Islamic fundamentalism. Second, Iran further was wracked by violence and unrest when secularist elements of the revolution (liberal democrats, communists, merchants and landowners, etc.) opposed the Islamist hardliners’ rise to power. The Islamic state subsequently marginalized these groups and suppressed all forms of dissent. Third, the revolution

seriously weakened the powerful Iranian Armed Forces, as military elements, particularly high-ranking officers, who remained loyal to the Shah, was purged

and repressive measures were undertaken to curb the military. Fourth, Iran’s newly established Islamic

government, because it rejected both western democracy and communist ideology, became isolated internationally, even among Arab and Muslim countries.

Because of the United States’ support for Iran’s previous regime and in response to the U.S. government’s allowing the ailing Shah to seek medical treatment in the United States, hundreds of radical Iranian students broke into the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979 and took hostage over sixty American diplomatic personnel and citizens. (This event, known as the Iran hostage crisis, ended on January 20, 1981 when the 52 remaining hostages were released.) In response, the United States ended diplomatic, economic, and later, military relations with Iran, and imposed economic sanctions and military restrictions. These U.S. sanctions were detrimental to Iran, in particular with regards to the coming war with Iraq, as the weapons and military hardware of the Iranian Armed Forces were sourced

from the United States.

Saddam wanted to make Iraq the dominant power in the Middle East, a position traditionally held by Egypt but which Egyptian President Anwar Sadat

had yielded politically after signing a peace agreement with Israel in March 1979. Iraq’s military buildup had, by the start of the war, boasted some 200,000 soldiers, 2,700 tanks, 1,000 artillery pieces, and 330 planes. By contrast, Iranian forces consisted of 150,000 soldiers, 1,700 tanks, 1,000 artillery

pieces, and 440 planes.

Foreign Support

The war saw the involvement of the two major superpowers, as both the United States and the Soviet Union, in the Cold War context, sought to gain favorable political, military, and economic outcomes from the conflict. The Soviet Union, long a supplier of military weapons to Iraq, backed Saddam, and also sought (unsuccessfully) to establish close ties with Iran. The United States initially was averse to both sides of the war, viewing Iraq as a Soviet satellite and an enemy of Israel, and Iran as an anti-American fanatical Islamic state. With the breakdown of relations with Iran resulting from the Tehran hostage crisis, the United States threw its support (somewhat

ambivalently) behind Iraq.

Like the United States, Persian Gulf monarchies were disinclined toward either side in the war,

opposing Iraq’s power ambitions and loathing Iran

even more, because of Ayatollah Khomeini’s view that monarchical governments were un-Islamic, and encouraged their overthrow. But with Iran taking the military initiative by 1982, the Gulf monarchies, particularly Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates, became alarmed at a potential Iranian victory and released large sums of money, by way of loans, to Iraq. Israel also was averse to either side, as both countries held anti-Zionist policies, but ultimately supported Iran, viewing the Iraqi government’s more pronounced military involvement in the Arab-Israeli wars as the bigger threat.

Very few other countries were inclined to support Iran, which was considered an outcast in the international community and, throughout the coming

war, would experience difficulty procuring weapons and spare parts for its American-made military equipment. Most Arab League states backed predominantly Arab Iraq against “Persian” (i.e. non-Arab) Iran. However, two Arab countries, Syria and Libya, backed and militarily supported Iran. Syria

and Iraq had a long history of mutual distrust, while Libya, an enemy of Iran’s deposed Shah, had welcomed the Iranian Revolution and established close ties with Iran’s Islamic government. North

Korea also sold weapons to Iran. Many other countries (e.g. China, the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Portugal, etc.), directly or through third-party arms dealers, sold weapons to both sides of the war.

Between 1985 and 1987, in an elaborate clandestine transaction, the United States

provided weapons to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages in Lebanon. This event, known as the Iran-Contra Affair, generated a breach in U.S.

laws and led to a number of United States Congressional investigations involving high-level U.S. administration officials.

War

An escalation of hostilities, including artillery exchanges and air attacks, took place in the period preceding the outbreak of war. On September 22, 1980, Iraq opened a full-scale offensive into Iran

with its air force launching strikes on ten key Iranian airbases, a move aimed at duplicating Israel’s devastating and decisive air attacks at the start of the Six-Day War in 1967. However, the Iraqi air attacks

failed to destroy the Iranian air force on the ground as intended, as Iranian planes were protected by reinforced hangars. In response, Iranian planes took to the air and carried out retaliatory attacks on Iraq’s

vital military and public infrastructures.

Throughout the war, the two sides launched many air attacks on the other’s economic infrastructures, in particular oil refineries and depots, as well as oil transport facilities and systems, in an attempt to destroy the other side’s economic capacity. Both Iran and Iraq were totally dependent on their oil industries, which constituted their main source of revenues. The oil infrastructures were nearly totally destroyed by the end of the war, leading to the near collapse of both countries’ economies. Iraq was much more vulnerable, because of its limited outlet to the sea via the Persian Gulf, which served as its only maritime oil export route.

Iran, which possessed a powerful navy, imposed a naval blockade around the Persian Gulf, effectively land-locking Iraq, while Syria, Iran’s ally, closed down the Kirkuk-Banias oil pipeline, through which Iraq

exported its petroleum via Syria. Iraq was left with the Kirkuk-Ceyhan outlet through Turkey, which also became vulnerable to attack later in the war when Iraqi Kurds of northern Iraq rose up in rebellion and became allied with Iran in the war.

Together with its air attacks on the first day of the war, Iraqi ground forces launched simultaneous offensives along three fronts: north, central, and south. The northern front advanced east of Sulaymaniyah, aimed at protecting northern Iraq’s vital installations, including the Kirkuk oil fields and

Darbandikhan Dam. The central front also was strategically defensive and consisted of two operations, one in the north that advanced and successfully took Qasr-e Shirin toward the approaches of the Zagros Mountains, intended to guard the Baghdad-Tehran Highway; and one in the

south that occupied Mehran, an important junction in Iran’s north-south road near the border with Iraq.

The southern front was the focus of the invasion, where five Iraqi divisions attacked the petroleum resource-rich Iranian province of Khuzestan, which generated 90% of Iran’s oil production. Iraqi forces used bridging equipment to cross the Shatt al-Arab and once on the Iranian side of the river, met little opposition and thus made rapid progress toward

Khoramshahr and Susangerd. Iran was caught off-guard by the invasion and had stationed only an undermanned force to defend Khuzestan.

March 4, 2020

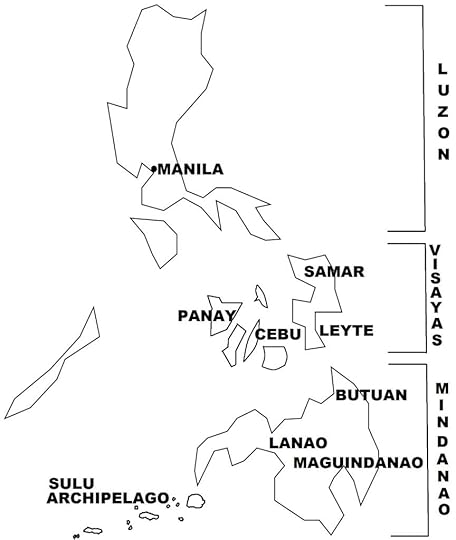

March 5, 1906 – Moro Rebellion: U.S. forces storm Moro fortresses in the Battle of Bud Dajo

In Jolo, thousands of Moros, including women and children, and led by a fugitive named Pala (who was wanted by British authorities in Borneo) set up fortifications at Bud (Mount) Dajo, an extinct volcano five miles south of Jolo. In March 1906, U.S. forces stormed these fortresses in the encounter known as the Battle of Bud Dajo, resulting in perhaps all 900–1,000 Moros killed; U.S. Army casualties were 21 killed and 75 wounded.

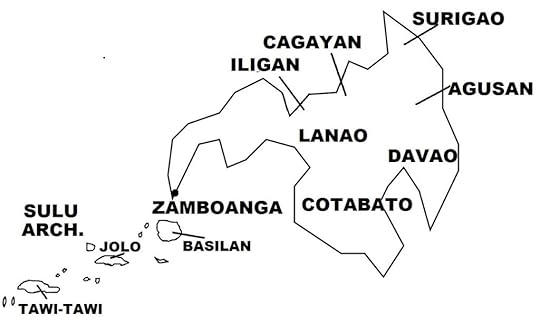

The Philippines in Southeast Asia.