Daniel Orr's Blog, page 103

March 22, 2020

March 23, 1901 – Philippine-American War: Filipino revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo is captured

On March 23, 1901, U.S. Army-recruited Filipino soldiers and their American officers captured Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela; the Filipino leader soon pledged allegiance to the United States and called on other revolutionaries to end hostilities and surrender. However, the war continued, since Aguinaldo had previously set up a line of succession to the revolutionary leadership, a post that was filled after his capture by General Miguel Malvar, who operated

mainly in Batangas, and also in nearby provinces.

Key areas during the Philippine-American War.

The year 1901 saw the most intense phase of the U.S. reconcentrado policy implemented in many areas held by the revolutionaries. In January of that year, interior villages in Marinduque were depopulated and their residents moved to coastal guarded camps before the U.S. Army launched inland operations

to flush out the insurgents. Three months later, in April, U.S. forces carried out similar operations in Abra in northern Luzon. Also in April, U.S. forces launched a scorched-earth sixty-mile wide destruction of villages and farmlands in Panay Island from Iloilo in the south to Capiz in the north. Then

in September, in the event known as the Balangiga Massacre, Filipino guerillas attacked an American garrison in Balangiga, Samar, killing nearly all the U.S.

soldiers. In reprisal, U.S. General Jacob Smith issued the following instructions to U.S. Marines who were tasked with pacifying Samar, “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and the more you burn, the more you will please me…The

interior of Samar must be made into a howling wilderness”. The age limit specified was ten, i.e. all

persons above this age was to be killed.

The Philippines in Southeast Asia.

(Taken from Philippine-American War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

Throughout the Spanish colonial rule (which began in 1565) over much of the archipelago that now comprises the country called the Philippines, the native inhabitants of the islands often offered resistance and launched scores of mostly local or

limited-scope rebellions, all of which generally failed to have a marked or long-lasting effect on Spain’s political and military control of the colony. Developments in the 19th century, however, sparked the emergence of a unified collective Filipino

consciousness among the separate islands’ numerous and diverse ethnic groups, which soon led to the development of a nationalist vision for the archipelago. Among these developments were the opening in 1834 of Manila (as well as other ports in the Philippine islands) to world trade, the entry of foreign firms (e.g. British, American, French, Swiss, and German) to compete with the erstwhile Spanish-owned commercial and trade monopolies, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 that accelerated European-Asian trade, and the 1868 Glorious Revolution in Spain that established a progressive government which in turn appointed a liberal,

democratic-minded Governor-General in the Philippines.

Traditional Philippine colonial society, which was

stratified into the peninsulares (Spanish nationals born in Spanish) and insulares (Spanish nationals born in the Philippines) upper ruling classes, the mestizo (descendants of Spanish-native unions) and pre-colonial native nobility lower ruling classes, and the masses of indios (natives) lower classes (comprising peasants, and rural and urban laborers), was transformed during the second half of the 19th century with the rise of the middle class, which

consisted of landed farmers, teachers, lawyers, physicians, and government workers. The members of this new social class, which emerged and benefited from the central government’s political and economic reforms, placed great emphasis on education and sent their children for advanced schooling in Manila and even in Spain and other European cities, thereby producing a second generation of the enlightened (i.e. educated) middle class, which was called the ilustrado class.

This ilustrado middle class, working together with political exiles from the islands, organized as the Propaganda Movement during the last decades of the 19th century and established its main base of activities in Spain, where progressive ideas were prevalent and generally tolerated, and not in their homeland, which although officially run by a civilian government under the Governor-General, was highly influenced by the powerful Catholic religious orders (Augustinians, Dominicans, and Franciscans), which held the real political power especially in the countryside where most of the natives resided. The Propaganda Movement pursued its ideological views through the fine arts (painting, sculpture, etc.) and

print (most notably the newspaper La Solidaridad and Jose Rizal’s two scathing novels against the Spanish colonial system in the Philippines). Politically, the movement did not seek independence and instead called on Spain to implement reforms including local representation in the Spanish parliament, civil and social reforms, and the end of the religious orders’ political and social domination of the colony. However, Spain was intransigent to change and by 1896, the Propaganda Movement had sputtered and

effectively ceased to exist.

In 1892, a reformist organization, La Liga Filipina (The Philippine League), was founded in Manila (by Rizal who had returned to the Philippines) which, in its brief existence that was cut short by Spanish

authorities and Rizal’s arrest and deportation, was crucial to advancing the nationalist cause because it had members from the lower social classes who

became exposed to liberal, progressive ideas. Then on La Liga Filipina’s dissolution, Andres Bonifacio, a Manila warehouse worker, and his other associates from the lower classes, secretly organized the Katipunan (Filipino: Samahang Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan; English: Supreme and Most Honorable Society of

the Children of the Nation), a militant mass-based radical movement that advocated the establishment of an independent Philippine state through violent revolution against Spain.

By 1896, the rebel movement numbered some 30,000 members, drawn mostly from the rural and urban lower class but also from nationalist-minded middle class leaders, professionals, and even local public officials, with the latter group heading many of the insurgent organization’s local and regional revolutionary councils. The movement spread throughout much of the archipelago with active

recruitment campaigns being carried out particularly in Manila’s nearby provinces including Manila (province), Bulacan, Pampanga, Nueva Ecija, Tarlac,

Cavite, Laguna, and Batangas, and also other parts of Luzon as well as the Visayan islands, and some Christian parts of Mindanao.

Spanish authorities soon learned of the clandestine organization and conducted widespread arrests of suspected members, which forced the as yet unprepared insurgents to commence hostilities with an attack on Manila in late August 1896 in an attempt to overthrow the Spanish government. The Spanish Army repulsed the attack and Bonifacio and his insurgent forces fell back to the hills east of Manila where they reorganized as a guerilla militia that engaged in hit-and-run warfare. Provincial rebel commands also initiated similar armed uprisings, which likewise were easily quelled by local Spanish

Army units, except in Cavite where the revolutionary leaders, most notably Emilio Aguinaldo (who later would play a major role in the Philippine-American War), defeated and expelled the Spanish forces and gained control of much of the province. Tensions soon developed between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo, which led to a power struggle. By March 1897, Aguinaldo had emerged as the organization’s de facto

leader, having executed his rival, although many provincial revolutionary commands operated as virtually independent commands and others, particularly in the Visayan islands, were distrustful of being ethnically dominated by revolutionaries from Luzon in the post-war period.

By May 1897, with the arrival of reinforcements and weapons from Spain, the Spanish Army launched a major offensive that gained back control of Cavite and many other insurgent-occupied areas, and Aguinaldo was forced to be constantly on the move until finding relatively safe refuge in the mountains north of Manila where he carried out a guerilla struggle. By this time, the Spanish authorities

realized the difficulty of capturing Aguinaldo and sought the mediation of influential Filipinos and mestizos (some of whom had been involved with the

rebel movement but had since been won over to Spain with the offer of amnesty). After several months, in December 1897, these mediation efforts led to the signing by Filipino and Spanish representatives of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, a peace treaty that ended hostilities.

The peace treaty stipulated that in exchange for Aguinaldo and other revolutionary leaders ending the rebellion, surrendering a pre-determined number of firearms, and going into voluntary exile abroad, Spain

would pay Aguinaldo and the revolutionary leadership a monetary indemnity (to be paid in three installments). The two sides did not fully comply with the treaty’s provisions, and much tension and mistrust persisted. On December 23, 1897, Aguinaldo and his party of revolutionaries did go to voluntary exile in Hong Kong where they plotted to renew hostilities with a cache of newly acquired weapons that were purchased using the indemnity money given by the Spanish government. In the islands, the Spanish Army continued to face sporadic local armed resistance and thus failed to fully pacify the archipelago, and consequently also could not implement amnesty.

At this stage of political uncertainty, the Spanish-American War broke out on April 25, 1898, with hostilities centered mainly in Cuba, with the United States taking the side of the Cuban revolutionaries who had been engaged in a protracted independence war against colonial Spain for three years (since February 1895). The United States then sent a naval squadron to the Philippines, and on May 1, 1898 at the Battle of Manila Bay, the U.S. ships, commanded by Commodore George Dewey, dealt a crushing defeat on the Spanish Navy. Commodore Dewey then imposed a naval blockade of Manila Bay while awaiting the formation in the United States of ground troops to carry out the land war against the Spanish Army in Manila and the Philippines.

Meanwhile, U.S. consular officials in Singapore

met with Aguinaldo, these talks soon becoming a subject of great controversy, as the Filipino leader later asserted that these officials, ostensibly

representing the U.S. government, promised him that in exchange for the Filipino revolutionaries’ support to the United States in the war against Spain,

the U.S. government would recognize Philippine independence. However, the U.S. government declared that no such promise to Aguinaldo was made and that the U.S. consular officials were not in authority to enter into negotiations for and in behalf of the United States.

At any rate, the meetings brought about a tacit alliance between the Filipino revolutionaries and the United States, and a U.S. ship transported Aguinaldo and his party from Hong Kong to the Philippines, with the revolutionary leaders arriving in Manila on May 19, 1898 to restart the uprising against Spain. Aguinaldo’s return had a catalyzing effect, as the revolution, although not completely dying down during his absence, rose to such an intensity that within a short period, insurgent provincial commands

had seized control of much of the territories, including the provinces of Laguna, Batangas, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Tayabas, and Camarines. By July 1898, the Filipino insurgents controlled much of the archipelago, except Manila, which was surrounded and placed under siege by some 12,000 revolutionary troops. Sensing imminent victory, on June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines, which was followed six days later by the formation of a dictatorial government, with himself as the new country’s president. On June 23, he abolished the dictatorial government, instead creating a revolutionary government, also with himself as president.

Meanwhile, on June 30, 1898, the first of three batches of U.S. ground troops arrived and were landed in Cavite, south of Manila; by late July 1898, General Wesley Merritt, commander-in-chief of the Philippine Expeditionary Forces, had arrived and the total U.S. Army troop strength numbered 12,000 soldiers. Then as U.S. forces deployed closer to Manila, skirmishes began to break out, the most serious taking place on August 8, 1898 when eight American soldiers were killed or wounded. These incidents prompted the U.S. military command to suspect that the Filipino revolutionaries were passing on information to Spanish authorities about the American troop movement, highlighting the increasingly deteriorating relations between the two nominal allies.

Meanwhile, the anticipated showdown between U.S. and Spanish forces in the Philippines did not materialize, as the Spanish central government in Madrid realized imminent defeat in Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. On August 12, 1898 in

Washington, D.C., the United States and Spain signed the “Protocol of Peace” that ended hostilities between the two countries; this agreement did not reach the Philippines until August 16. However, U.S. and Spanish authorities in Manila also entered into secret negotiations, which led to the two sides agreeing to carry out a mock battle for control of Manila; the plan was aimed at preserving Spanish military honor that otherwise would be tarnished if the Spanish Army surrendered without a fight, and the two sides would be spared unnecessary loss of lives. More importantly for the two powers and in the context of regional and global rivalries (with the other European powers operating in the Asia-Pacific), Manila (and thus the Philippines) would be passed on from Spain to the United States, and without the

participation of the Filipino revolutionaries.

Without disclosing the plan, U.S. authorities warned Aguinaldo to keep his forces inside Filipino defensive

lines, and faced the risk of meeting U.S. fire if they advanced.

As agreed, on August 13, 1898, Spanish and American forces carried out the mock battle, which involved an assault by U.S. forces, some cursory exchange of gunfire, and a pre-determined signal to indicate that the Spanish Army was ready to

surrender and turn over Manila to the Americans. The battle ended successfully, with U.S. forces gaining control of the capital, although it was marred somewhat when, at the start of the American offensive, Filipino troops also advanced from their

lines, prompting an exchange of gunfire between the two sides that claimed six American and forty-nine Spanish troop casualties.

In the aftermath, Filipino forces gained control of sections of Manila and Aguinaldo insisted in joint Filipino-American occupation of the capital. On August 17, 1898, U.S. President William McKinley informed General Elwell Otis that only U.S. forces were to occupy Manila, thus indicating the United States’ intention to keep the Philippines. A few days earlier, August 14, the United States established a military government in the islands, with General Merritt taking the position of (the first) military Governor. U.S. authorities threatened the use

of armed force against Aguinaldo if the Filipino units were not withdrawn from the capital; on September 15, 1898, the latter reluctantly withdrew his forces

to a defensive line extending across the perimeter of the capital.

In late September 1898, American and Spanish representatives met in Paris to begin work on a treaty to officially end the war, particularly with regards to

the future of Spanish territories involved in the conflict. Negotiations were difficult with respect to

the Philippines, as the United States demanded possession of first only Luzon and later the whole archipelago, which Spain strongly opposed. Finally, however, on December 10, 1898, the two countries signed the Treaty of Paris, where Spain ceded Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States; with regards to the Philippines particularly, the U.S. government paid Spain the amount of U.S. $20 million for “Spanish improvements” made in the colony.

The treaty, which needed to be approved by the two countries, experienced considerable opposition in the U.S. and Spanish legislatures. On March 19, 1899, Spain ratified the treaty with the intervention of the Spanish monarchy. In the U.S. Senate, a vote on the treaty set for February 6, 1899 appeared to just fall short of the two-thirds majority needed for approval. However, developments in the Philippines

would influence the vote.

In early January 1899, U.S. ships trying to land American troops in Iloilo City were blocked by thousands of local Filipino troops. From Malolos (where the Filipino central government was headquartered), Aguinaldo threatened to use force if the Americans forced a landing. In the midst of rising tensions, on January 4, 1899, President McKinley’s “Benevolent Assimilation” policy of American annexation of the islands was released, generating even more discord.

March 21, 2020

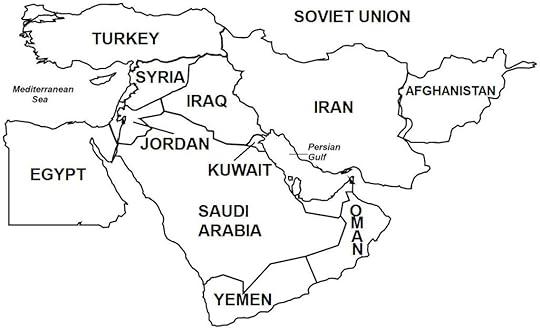

March 22, 1979 – Israel’s parliament approves the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty, ending the two countries’ state of war

Following the Yom Kippur War (October 1973), on January 18, 1974, Egypt and Israel signed a Disengagement of Forces Agreement (also known as the Sinai I Agreement). The agreement established a buffer zone between Egyptian and Israeli forces that was to be monitored by the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF). Only a limited amount of armament and forces were permitted inside the

buffer zone.

On September 4, 1975, Egypt and Israel signed the Sinai Interim Agreement (also known as Sinai II Agreement), where both sides pledged that conflicts between them “shall not be resolved by military force but by peaceful means.” A further withdrawal was agreed and a wider UN buffer zone was created.

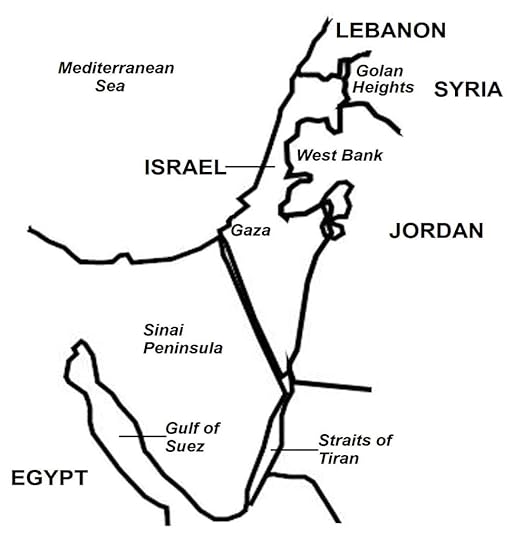

These agreements paved the way for the Camp David Accords (in Camp David, Maryland), which led to the signing of the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty on March 26, 1979. This landmark peace treaty ended their state of war and normalized relations, and Egypt became the first Arab state to officially recognize Israel. On March 22, 1979, Israel’s parliament (Knesset) approved the peace treaty.

Diplomatic relations between them came into effect in January 1980, with an exchange of ambassadors the following month. Israel withdrew from the Sinai, which Egypt reoccupied and promised to leave demilitarized. Israeli ships were allowed free passage through the Suez Canal, and Egypt recognized the Strait of Tiran and Gulf of Aqaba was international waterways.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

With its decisive victory in the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights were integral territories of Egypt and Syria, respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, together with other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”, that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant that only armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently was not received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egypt

carried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and government targets in the Sinai. In what is now known as the “War of Attrition”, Egypt was determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai. By way of retaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel, and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly became involved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israel and Egypt to agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passed away. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President Anwar Sadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchly hostile to Israel, President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeli conflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations (UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign a peace treaty with Israel and recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to negotiate. President Sadat, therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging the Israelis from the Sinai. He decided that an Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israel to see the need for negotiations. Egypt began preparations for war. Large amounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, but ineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number of ruses. The Egyptian Army constantly

conducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoric eventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the true strength of its armed forces. The government also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its war

equipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated military hardware. Furthermore, when President Sadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egypt in July 1972, Israel

believed that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakened seriously. In fact, thousands of Soviet

personnel remained in Egypt and Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syrian

counterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized for war.

Israel’s intelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the date of the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbers of Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egypt and Syria attacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiers and the entire Israeli Air Force.

However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting a war and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carrying out a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War) to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur (which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, when most Israeli soldiers were on leave.

March 20, 2020

March 21, 1975 – Ethiopian Civil War: The 3,000-year old monarchy of Ethiopia is abolished

On September 12, 1974, military officers belonging to the Derg organization overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia in a bloodless coup, leading away the frail, 82-year old ex-monarch to imprisonment.

The Derg gained control of Ethiopia but did not abolish the monarchy outright, and announced that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, Haile Selassie’s son who was currently abroad for medical treatment, was to succeed to the throne as the new “king” on his return to the country. However, Prince Wossen rejected the offer and remained abroad. The Derg then withdrew

its offer and in March 1975, abolished the monarchy altogether, thus ending the 3,000 year-old Ethiopian Empire. (On August 27, 1975, or nearly one year after his arrest, Haile Selassie passed away under mysterious circumstances, with Derg stating that complications from a medical procedure had caused his death, while critics alleging that the ex-monarch was murdered.)

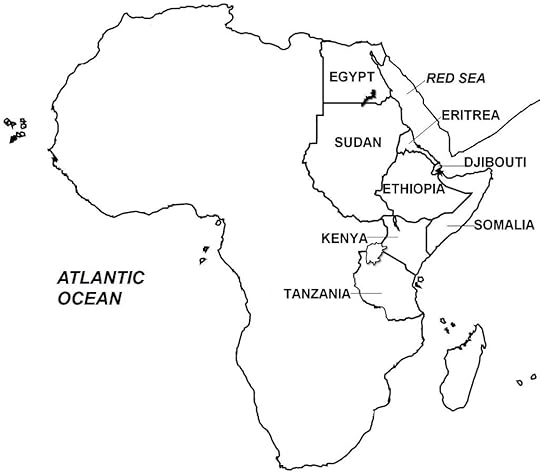

Ethiopia and nearby countries.

(Taken from Ethiopian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

The surreptitious means by which Derg, in a period of six months, gained power by progressively dismantling the Ethiopian Empire and ultimately deposing Haile Selassie, sometimes is referred to as the “creeping coup” in contrast with most coups, which are sudden and swift. On September 15, 1974, Derg formally took control of the government and renamed itself as the Provisional Military Administrative Council (although it would continue to be commonly known as Derg), a ruling military junta under General Aman Andom, a non-member Derg whom the Derg appointed as its Chairman; General Aman thereby also assumed the role of Ethiopia’s head of state.

At the outset, Derg had its political leanings embodied in its slogans “Ethiopia First” (i.e. nationalism) and “Democracy and Equality to all”. Soon, however, it abolished the Ethiopian parliament, suspended the constitution, and ruled by decree. In early 1975, Derg launched a series of broad reforms that swept away the old conservative order and began the country’s transition to socialism. In

January-February 1975, nearly all industries were nationalized. In March, an agrarian reform program

nationalized all farmlands (including those owned by the country’s largest landowner, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church), reduced farm sizes, and abolished

tenancy farming. Collectivized agriculture was introduced and farmers were organized into peasant

organizations. (Land reform was fiercely resisted in such provinces as Gojjam, Wollo, and Tigray, where most farmers owned their lands and tenant farming was not widely practiced.) In July 1975, all urban lands, houses, and buildings were nationalized and city residents were organized into urban dwellers’ associations, known as “kebeles”, which would play a major role in the coming civil war. Despite the

extensive nationalization, a few private sector industries that were considered vital to the economy were left untouched, e.g. the retail and wholesale trade, and import and export industries.

In April 1976, Derg published the “Program for the National Democratic Revolution”, which outlined the regime’s objectives of transforming Ethiopia into a socialist state, with powers vested in the peasants, workers, petite bourgeoisie, and anti-feudal and anti-monarchic sectors. An agency called the “Provisional Office for Mass Organization Affairs” was established to work out the transformative process toward socialism.

Ethiopian Civil War

The political instability and power struggles that followed the Derg’s coming to power, the escalation of pre-existing separatist and Marxist insurgencies (as

well as the formation of new rebel movements), and the intervention of foreign players, notably Somalia as well as Cold War rivals, the Soviet Union and United States, all contributed to the multi-party, multi-faceted conflict known as the Ethiopian Civil War.

The Derg government underwent power struggles during its first years in office. General Aman, the non-Derg who had been named to head the government, immediately came into conflict with Derg on three major policy issues: First, he wanted to reduce the size of the 120-member Derg; Second, as an ethnic Eritrean, he was opposed to the Derg’s use of force against the Eritrean insurgency; and Third, he opposed Derg’s plan to execute the imprisoned civilian and military officials associated with the former regime. In November 1974, Derg leveled charges against General Aman and issued a warrant

for his arrest. On November 23, 1974, General Aman was killed in a gunfight with government security personnel who had been sent to arrest him.

Later that same day, in the event known alternatively as the “Massacre of the Sixty” or “Black Saturday”, Derg security units gathered a group of imprisoned high-ranking ex-government and ex-military officials and executed them at the Kerchele Prison in Addis Ababa. The Derg’s stated reasons for the executions were that these officials had made

“repeated plots … that might engulf the country into a bloodbath”, as well as “maladministration, hindering fair administration of justice, selling secret documents of the country to foreign agents and attempting to disrupt the present Ethiopian popular movement”.

Among those executed included Haile Selassie’s grandson, other members of the Ethiopian nobility, two ex-Prime Ministers, and seventeen army generals.

In late November 1974, Derg appointed General Tarafi Benti, also a non-Derg, to succeed as Derg Chairman and thus also became Ethiopia’s head

of state. At this time, Major Mengistu, Derg’s first vice-chairman, made attempts to expand his power base, which were countered by rival Derg factions allied with General Benti. For a time, the Benti faction appeared to have gained the upper hand, relegating Mengistu’s supporters outside key

government posts. However, in a decisive armed confrontation that took place between the two factions in early February 1977, General Benti was killed, along with some of his supporters, and Major

Mengistu emerged as the undisputed leader of Derg. Mengistu became Derg Chairman and the head of

government; thereafter, his authority would not be challenged and he would rule with dictatorial powers. In November 1977, the last remaining threat to Mengistu’s authority was eliminated when Major Atnafu, Derg’s vice-chairman, was executed.

Early on after Derg come to power, a number of

Marxist-Leninist groups, the two most prominent being the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP) and All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement (MEISON), competed for influence in Derg for the role of “vanguard party” which would provide direction for the country’s transition to socialism. EPRP opposed Derg’s military control and soon railed at the government for not carrying out a genuine “people’s revolution” along traditional Marxist lines; this criticism infuriated the Derg government. MEISON, however, was agreeable to a gradual

transitional period under a military regime, a position that found favor with Derg. Thereafter, Derg established a working relationship with MEISON and appointed a number of MEISON party members

to government positions.

Armed conflict soon broke out between Derg and MEISON on the one hand, and EPRP on the other hand. Starting in February 1977, in what the Derg regime called “White Terror”, EPRP militants assassinated Derg officials and MEISON members, and sabotaged government infrastructures. The Derg

government responded with its own, and much more brutal, campaign of violence against the EPRP called “Red Terror”. Local “kebeles” (urban residential associations) served as the government’s eyes and ears; suspected state enemies were arrested, tortured, and executed by government-sanctioned local “kebeles” death squads.

By December 1978, the government’s sustained repression had killed or imprisoned thousands of EPRP militants and supporters and had forced the EPRP to leave the cities and transfer to Agama

Province in northern Ethiopia where it reorganized as a rural guerilla militia. The Derg regime soon also came to distrust MEISON, its political mentor, as it saw the latter’s increasing autonomy as a potential threat. In mid-1977, the government launched a

campaign to eliminate MEISON, arresting and executing the group’s members and purging MEISON officials from government positions. In total, the Red Terror may have caused up to 250,000 – 500,000 deaths.

With the EPRP and MEISON eliminated by 1978, Derg merged a number of smaller socialist groups into the “Union of Ethiopian Marxist-Leninist Organization”, which became the new “vanguard party” to succeed MEISON under strict government oversight. Thereafter, Derg’s transitional process to

socialism met little internal opposition.

The country’s militarization alienated many of the

revolution’s early supporters, including teachers, students, and workers, while many officials of the previous regime who had not yet been arrested fled into exile abroad. Meanwhile, the regional ethnic insurgencies increased in magnitude under the Derg government. In Eritrea, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) had succeeded the ELF has the leading separatist movement, while in Tigray province, many armed groups also had organized, foremost of which was the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), whose (initial) goal was

secession of Tigray from Ethiopia. Both the Eritrean and Tigrayan insurgencies achieved considerable success, ultimately seizing control of some 90% of Eritrea and Tigray, respectively, mainly in rural and hinterland areas (government troops retained control of the major urban centers), and turning back repeated Ethiopian Army offensives.

March 19, 2020

March 20, 1951 – Korean War: General Douglas MacArthur is told that the United States would first offer peace to China and North Korea before allowing UN forces to cross the 38th parallel into North Korea

On March 20, 1951, General Douglas MacArthur received a communication from the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff stating that the U.S. government was ready to offer peace talks with China and North Korea, before President Truman would allow UN forces to cross the 38th parallel into North Korea. Instead, on March 24, General MacArthur announced an ultimatum, demanding that China withdraw its troops or face the consequences of UN forces advancing into North Korea. In early April 1951, with General MacArthur’s

approval, UN forces crossed the 38th parallel, and by April 10, had advanced some 10 miles north to a new line designated the “Kansas Line”.

On April 11, 1951, in a nationwide broadcast, President Truman relieved General MacArthur of his command in Korea, stating that a crucial objective of U.S. government policy in the Korean conflict was to avoid an escalation of hostilities which potentially could trigger World War III, and that “a number of events have made it evident that General MacArthur did not agree with that policy.” General MacArthur had openly advocated an escalation of the war, including directly attacking China, involving forces from Nationalist China (Taiwan), and using nuclear weapons.

General Ridgway, Eighth U.S. Army commander, was named to succeed as Supreme UN and U.S. Commander in Korea. Unlike his predecessor who desired nothing short of total victory, General Ridgway favored a limited war and accepted a

divided Korea, and thus worked closely with the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Truman administration.

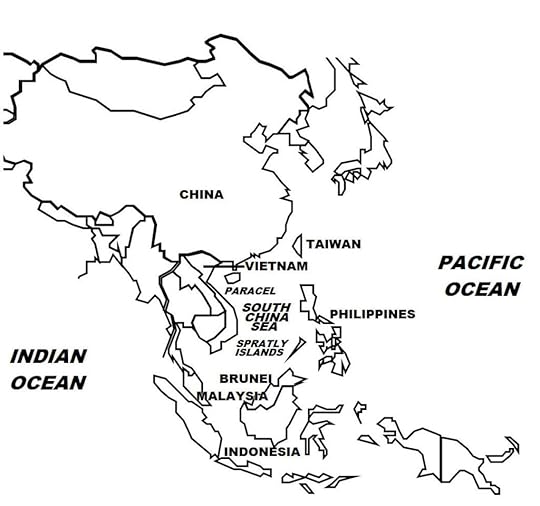

East Asia.

East Asia.(Excerpts taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background

During World War II, the Allied Powers met many times to decide the disposition of Japanese territorial holdings after the Allies had achieved victory. With regards to Korea, at the Cairo Conference held in November 1943, the United States, Britain, and Nationalist China agreed that “in due course, Korea shall become free and independent”. Then at the Yalta Conference of February 1945, the Soviet Union promised to enter the war in the Asia-Pacific in two or three months after the European theater of World War II ended.

Then with the Soviet Army invading northern Korea on August 9, 1945, the United States became concerned that the Soviet Union might well occupy the whole Korean Peninsula. The U.S. government, acting on a hastily prepared U.S. military plan to divide Korea at the 38th parallel, presented the proposal to the Soviet government, which the latter accepted.

The Soviet Army continued moving south and stopped at the 38th parallel on August 16, 1945. U.S. forces soon arrived in southern Korea and advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8, 1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S. and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in their respective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commands established military rule in their occupation zones.

As both the U.S. and Soviet governments wanted to reunify Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December 1945, the Allied Powers agreed to form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China) five-year trusteeship over Korea. During the five-year period, a U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission would work out the process of forming a Korean government. But after a series of meetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve

anything. In September 1947, the U.S. government referred the Korean question to the United Nations (UN). The reasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission’s failure to agree to a mutually acceptable Korean government are three-fold and

to some extent all interrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed U.S.-Soviet trusteeship; the struggle for power among the various ideology-based political factions; and most important, the emerging Cold War confrontation between the United States

and the Soviet Union.

Historically, Korea for many centuries had been a politically and ethnically integrated state, although its independence often was interrupted by the invasions by its powerful neighbors, China and Japan. Because of this protracted independence, in the immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, and viewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run their own affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’s political climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, from right-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashed with each other for political power. As a result of Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were the unrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and a communist-allied anti-Japanese

partisan militia led by Kim Il-sung. Both men would play major roles in the Korean War. At the same time, tens of thousands of Koreans took part in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese

Civil War, joining and fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces, or for Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japanese resistance movement, which operated mainly out of Manchuria, was divided along ideological lines. Some groups advocated

Western-style capitalist democracy, while others espoused Soviet communism. However, all were strongly anti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria, China, and Korea.

On their arrival in the southern Korean zone in September 1948, U.S. forces imposed direct rule through the United States Army Military Government

In Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members of the Korean Communist Party in Seoul (the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeated

Japanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Korean peninsula. Then two days before U.S. forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee”

proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under the auspices of a U.S. military agent, Syngman Rhee, the former

president of the “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” arrived in Seoul. The USAMGIK refused to recognize the communist Korean People’s Republic, as well as the pro-West “Provisional Government”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form a political coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S.

sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. However, this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wing

and right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S. authorities’ breaking up the communists’ “people’s committees” violence broke out in the southern zone during the last months of 1946. Called the Autumn Uprising, the unrest was carried out by left-aligned workers,

farmers, and students, leading to many deaths through killings, violent confrontations, strikes, etc. Although in many cases, the violence resulted from non-political motives (such as targeting Japanese collaborators or settling old scores), American authorities believed that the unrest was part of a communist plot. They therefore declared martial law in the southern zone. Following the U.S. military’s crackdown on leftist activities, the communist militants went into hiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would play

a role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, Soviet commanders initially worked to form a local administration under a coalition of nationalists,

Marxists, and even Christian politicians. But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who also was a Soviet Red Army officer, quickly became favored by Soviet authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’s Committee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by Kim Il-sung who soon consolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christian leaders), and nationalized industries, and launched centrally planned economic and reconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model emphasizing heavy

industry.

By 1947, the Cold War had begun: the Soviet Union tightened its hold on the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United States announced a new foreign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed at stopping the spread of communism. The United States also implemented the Marshall Plan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which was condemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed at

dividing Europe. As a result, Europe became divided into the capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting these developments, in Korea

by mid-1945, the United States became resigned to the likelihood that the temporary military partition of the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel would become a permanent division along ideological grounds. In September 1947, with U.S. Congress

rejecting a proposed aid package to Korea, the U.S.

government turned over the Korean issue to the UN. In November 1947, the United Nations General

Assembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’s sovereignty and called for elections throughout the Korean peninsula, which was to be overseen by a newly formed body, the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Soviet government rejected the UNGA resolution, stating that the UN had no jurisdiction over the Korean issue, and prevented

UNTCOK representatives from entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were held only in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experienced widespread violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, a

legislative body. Two months later (in July 1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitution which established a presidential form of government. Syngman Rhee, whose party won the most number of legislative seats, was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southerners proclaimed the birth of the Republic

of Korea (soon more commonly known as South Korea), ostensibly with the state’s sovereignty covering the whole Korean Peninsula.

A consequence of the South Korean elections was the displacement of the political moderates, because of their opposition to both the elections and the division of Korea. By contrast, the hard-line anti-communist Syngman Rhee was willing to allow the (temporary) partition of the peninsula. Subsequently, the United States moved to support the Rhee regime, turning its back on the political moderates whom USAMGIK had backed initially.

Meanwhile in the Soviet-controlled northern zone, on August 25, 1948, parliamentary elections were held to the Supreme National Assembly. Two weeks later (on September 9, 1948), the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as North Korea) was proclaimed, with Kim Il-Sung as (its first) Prime Minister. As with South Korea, North Korea declared its sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula

The formation of two opposing rival states in Korea, each determined to be the sole authority, now set the stage for the coming war. In December 1948, acting on a report by UNTCOK, the UN declared that the Republic of Korea (South Korea) was the legitimate Korean polity, a decision that was rejected by both the Soviet Union and North Korea. Also in December 1948, the Soviet Union withdrew its forces from North Korea. In June 1949, the United States

withdrew its forces from South Korea. However, Soviet and American military advisors remained, in the North and South, respectively.

In March 1949, on a visit to Moscow, Kim Il-sung asked Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, for military assistance for a North Korean planned invasion of South Korea. Kim Il-sung explained that an invasion would be successful, since most South Koreans opposed the Rhee regime, and that the communist insurgency in the south had sufficiently weakened the South Korean military. Stalin did not give his consent, as the Soviet government currently was pressed by other Cold War events in Europe.

However, by early 1950, the Cold War situation had been altered dramatically. In September 1949,

the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, ending the United States’ monopoly on nuclear

weapons. In October 1949, Chinese communists, led by Mao Zedong, defeated the West-aligned Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek in the Chinese Civil War, and proclaimed the People’s

Republic of China, a socialist state. Then in 1950, Vietnamese communists (called Viet Minh) turned the First Indochina War from an anti-colonial war against France into a Cold War conflict involving the Soviet Union, China, and the United States. In February 1950, the Soviet Union and China signed the Sino-Soviet Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance Treaty, where the Soviet government would provide military and financial aid to China.

Furthermore, the Soviet government, long wanting to gauge American strategic designs in Asia, was encouraged by two recent developments:

First, the U.S. government did not intervene in the Chinese Civil War; and second, in January 1949, the United States announced that South Korea was not part of the U.S. “defensive perimeter” in Asia, and U.S. Congress rejected an aid package to South Korea. To Stalin, the United States was resigned to the whole northeast Asian mainland falling to communism.

In April 1950, the Soviet Union approved North Korea’s plan to invade South Korea, but subject to two crucial conditions: Soviet forces would not be involved in the fighting, and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA, i.e. the Chinese armed forces) must agree to intervene in the war if necessary. In May 1950, in a meeting between Kim Il-sung and Mao Zedong, the Chinese leader expressed concern that the United States might intervene if the North Koreans attacked South Korea. In the end, Mao agreed to send Chinese forces if North Korea was invaded. North Korea then hastened its invasion plan.

The North Korean armed forces (officially: the Korean People’s Army), having been organized into its present form concurrent with the rise of Kim Il-sung, had grown in strength with large Soviet support. And in 1949-1950, with Kim Il-sung emphasizing a massive military buildup, by the eve of the invasion, North Korean forces boasted some 150,000–200,000 soldiers, 280 tanks, 200 artillery pieces, and 200 planes.

By contrast, the South Korean military (officially: Republic of Korea Armed Forces), which consisted

largely of police units, was unprepared for war. The United States, not wanting a Korean war, held back from delivering weapons to South Korea, particularly since President Rhee had declared his intention to invade North Korea in order to reunify the peninsula. By the time of the North Korean invasion, South Korean weapons, which the United States had limited to defensive strength, proved grossly inadequate. South Korea had 100,000 soldiers (of whom only 65,000 were combat troops); it also had no tanks and possessed only small-caliber artillery pieces and an assortment of liaison and trainer aircraft.

North Korea had envisioned its invasion as a concentration of forces along the Ongjin Peninsula. North Korean forces would make a swift assault on Seoul to surround and destroy the South Korean forces there. Rhee’s government then would collapse, leading to the fall of South Korea. Then on June 21, 1950, four days before the scheduled invasion, Kim Il-sung believed that South Korea had become aware of the invasion plan and had fortified its defenses. He revised his plan for an offensive all across the 38th parallel. In the months preceding the war, numerous border skirmishes had begun breaking out between the two sides.

March 18, 2020

March 19, 1982 – Falklands War: Argentinean workers raise the Argentine flag in South Georgia Island

By March 1982, the Argentinean military had completed its invasion plan. Occasionally, Argentinean officials made hinted references to the invasion, which apparently were overlooked by the British government.

The invasion plan called for Argentine forces first seizing South Georgia Island, located northwest of the South Sandwich Islands. On March 19, 1982, Argentinean contract workers in South Georgia

Island raised the Argentine flag. On April 3, fighting

broke out between the Argentinean invasion force and the small British garrison defending the island. The British inflicted some material damage to the invaders, but were overwhelmed and forced to surrender. South Georgia Island then came under Argentinean control.

The invasion of the Falklands began on April 2, 1982, with 100 Argentinean commandos landing at Port Stanley, the capital, ahead of the main force of 2,000 soldiers who later were landed amphibiously. After some skirmishes, the island’s British garrison of 60 soldiers surrendered, and the Falklands came under Argentine control.

In 1982, Argentina and Britain went to war for possession of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

(Taken from Falklands War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background

In early 1982, Argentina’s ruling military junta, led by General Leopoldo Galtieri, was facing a crisis of

confidence. Government corruption, human rights violations, and an economic recession had turned initial public support for the country’s military regime into widespread opposition. The pro-U.S. junta had come to power through a coup in 1976, and had crushed a leftist insurgency in the “Dirty War” by

using conventional warfare, as well as “dirty” methods, including summary executions and forced disappearances. As reports of military atrocities became known, the international community

exerted pressure on General Galtieri to implement reforms.

In its desire to regain the Argentinean people’s moral support and to continue in power, the military government conceived of a plan to invade the Falkland Islands, a British territory located about 700 kilometers east of the Argentine mainland. Argentina

had a long-standing historical claim to the Falklands,

which generated nationalistic sentiment among Argentineans. The Argentine government was determined to exploit that sentiment. Furthermore,

after weighing its chances for success, the junta concluded that the British government would not likely take action to protect the Falklands, as the

islands were small, barren, and too distant, being located three-quarters down the globe from Britain.

The Argentineans’ reasoning was not without merit. Britain under current Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was experiencing an economic recession, and in 1981, had made military cutbacks that would have seen the withdrawal from the Falklands of the HMS Endurance, an ice patrol vessel and the British Navy’s only permanent ship in the southern Atlantic

Ocean. Furthermore, Britain had not resisted when in 1976, Argentinean forces occupied the uninhabited Southern Thule, a group of small islands that forms a part of the British-owned South Sandwich Archipelago, located 1,500 kilometers east of the Falkland Islands.

In the sixteenth century, the Falkland Islands first came to European attention when they were signed by Portuguese ships. For three and a half centuries thereafter, the islands became settled and controlled at various times by France, Spain, Britain, the United States, and Argentina. In 1833, Britain gained uninterrupted control of the islands, establishing a permanent presence there with settlers coming mainly from Wales and Scotland.

In 1816, Argentina gained its independence and, advancing its claim to being the successor state of the former Spanish Argentinean colony that had included “Islas Malvinas” (Argentina’s name for the Falkland Islands), the Argentinean government declared that the islands were part of Argentina’s

territory. Argentina also challenged Britain’s account of the events of 1833, stating that the British Navy gained control of the islands by expelling the Argentinean civilian authority and residents already present in the Falklands. Over time, Argentineans perceived the British control of the Falklands as a misplaced vestige of the colonial past, producing successive generations of Argentineans instilled with anti-imperialist sentiments. For much of the twentieth century, however, Britain and Argentina maintained a normal, even a healthy, relationship, although the Falklands issue remained a thorn on both sides.

After World War II, Britain pursued a policy of decolonization that saw it end colonial rule in its vast territories in Asia and Africa, and the emergence of many new countries in their places. With regards to the Falklands, under United Nations (UN) encouragement, Britain and Argentina met a number of times to decide the future of the islands. Nothing substantial emerged on the issue of sovereignty, but the two sides agreed on a number of commercial ventures, including establishing air and sea links between the islands and the Argentinean mainland, and for Argentinean power firms to supply energy to the islands. Subsequently, Falklanders (Falkland

residents) made it known to Britain that they wished to remain under British rule. As a result, Britain

reversed its policy of decolonization in the Falklands

and promised to respect the wishes of the Falklanders.

March 17, 2020

March 18, 1962 – Algerian War of Independence: France and Algerian revolutionaries sign the Évian Accords

In May 1961, the French government and the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA; French: Gouvernement Provisionel de la République Algérienne) held peace talks in Évian, France, which proved contentious and difficult. But on March 18, 1962, the two sides signed an agreement called the Évian Accords, which included a ceasefire (that came into effect the following day) and a release of war prisoners; the agreement’s major stipulations were: French recognition of a sovereign Algeria; independent Algeria’s guaranteeing the protection of the pied-noir community; and Algeria allowing French military bases to continue in its territory, as well as establishing privileged Algerian-French economic and trade relations, particularly in the development of Algeria’s nascent oil industry. Pied-Noirs were Algeria-born people of French and other European origin.

In a referendum held in France on April 8, 1962, over 90% of the French people approved of the Évian Accords; the same referendum held in Algeria on July 1, 1962 resulted in nearly six million voting in favor of the agreement while only 16,000 opposed it (by this time, most of the one million pieds-noirs had or were in the process of leaving Algeria or simply recognized

the futility of their lost cause, thus the extraordinarily low number of “no” votes).

Map showing location of Algeria in North Africa.

(Taken from Algerian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

The first half of the twentieth century saw the rise of Algerian nationalism led by indigenous socio-political movements. Among these were the Algerian Communist Party, religious-based Association of Algerian Muslim Clerics, and the successive organizations led by Ferhat Abbas and Ahmed Messali Hadj, two nationalists who played major roles in the early independence struggles as well as in the forthcoming war of independence.

At the global stage, a number of events helped to spur the growth of nationalism in colonial territories worldwide. United States President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” speech to U.S. Congress, which became the basis for peace that ended World War I, contained a stipulation (point 5) on self-determination, i.e. “free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims…in determining all such questions of sovereignty, the interests of the population concerned must have equal weight…” Then in the midst of World War II, the so-called “Atlantic Charter” issued by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill stipulated that “all people have a right to self-determination.”

Furthermore, World War II politically weakened the French colonial empire, particularly France’s humiliating defeat to Germany and the destabilized political structure that emerged, with two rival regimes, Vichy France (under Marshall Philippe Pétain) and Free France (under General Charles de Gaulle), both vying for political legitimacy. The early Algerian nationalist movements used peaceful means to achieve their goals, participated in the electoral process, and for the most part, did not seek outright independence but worked to achieve political autonomy within the French system, greater representation, or more recognition of indigenous religious, cultural, and social rights. For instance, in March 1943, Algerian nationalists led by Abbas, presented France with the “Manifesto of the Algerian People”, which called for greater Algerian Muslim political participation and equality of indigenous peoples under the law.

Radicalization of Algerian nationalists occurred after World War II when French authorities, who had promised to take up Algeria’s self-determination in exchange for the Algerian Muslims’ support for France during the world war, reneged on their word and were determined to hold onto Algeria. Algerian nationalists were greatly disappointed, as thousands of Algerians had fought for France in both world wars.

On May 8, 1945, the day World War II ended in Europe, like many other locations around the world, Algeria celebrated Germany’s surrender to the Allied Powers. But in celebrations in Sétif, a town located 300 kilometers west of Algiers, commotion broke out when police authorities violently dispersed a crowd that was celebrating the Allied victory together with calls for Algerian independence. For three days thereafter, a full-scale uprising (which involved some

50,000 Algerians) took place that engulfed much of the territory, as armed bands roamed the countryside attacking European civilians, homes, and farms, and destroying government buildings and public infrastructures. French reprisal was vicious, with the French military using land, air, and sea counter-measures that, by June 1945, had decisively stamped out the rebellion. This incident, which was felt greatest at Sétif and Guelma and for which the event

derives its name, the “Sétif and Guelma Massacres”, caused over 100 Europeans killed and between 15,000 and 20,000 to as high as 45,000 Algerian Muslims killed.

As a result of these massacres as well as the post-World War II rise of nationalism among colonized peoples worldwide, Algerian nationalists became increasingly radicalized in their efforts to achieve

self-determination. In 1946, the Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifesto (UDMA; French: Union Démocratique du Manifeste Algérien), recently formed by Abbas, called on France to end the “department” status of Algeria and grant political autonomy to the territory. Also that year, the Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties

(MTLD; French: Mouvement pour le Triomphe des Libertés Démocratiques), led by Hadj, demanded France to grant outright independence to Algeria. These movements were deemed moderate as they

sought to achieve their objectives through peaceful, democratic means.

The Special Organisation (OS; French: Organisation Spéciale), however, which was a radical arm of the MTLD, was organized as a paramilitary that sought to achieve independence through armed rebellion; as with the other nationalist groups at that time, the OS disbanded without achieving its aims. Former elements of the OS and MTLD reorganized as the Revolutionary Committee of Unity and Action

(CRUA; French: Comité Révolutionnaire d’Unité et d’Action) that had similar revolutionary aspirations; after more changes, on October 14, 1954, CRUA

morphed into the National Liberation Front (FLN; French: Front de Libération Nationale). The FLN set November 1, 1954 as the start of the uprising which, unbeknown at that time, was the start of the eight-year Algerian War of Independence.

Early in the war, other Algerian nationalist groups were assimilated by the FLN in a common struggle to end French rule. Another independence organization, the Algerian National Movement (MNA; French: Mouvement National Algérien), led by Najh, also fought a revolutionary war separate from the FLN, generating a rivalry between the FLN and MNA for legitimacy and post-war supremacy. Armed confrontations between these two groups took place in Algeria, as well as France, which in the latter, the rivalry produced the so-called “Café Wars”, where each side carried out mafia-style shootings, disappearances, abductions, and bombings against the other side; some 5,000 people were killed in the Café Wars. In the end, the FLN prevailed and the war essentially was fought between the FLN, particularly its paramilitary wing called the National Liberation Army (ALN; French: Armée de Libération Nationale), which sought to end French rule and gain Algerian

independence; and France, which sought to suppress the insurgents’ separatist objectives.

March 16, 2020

March 17, 1988 – Eritrean War of Independence: The start of the Battle of Afabet between Eritrean revolutionaries and Ethiopian Army units

For Ethiopia’s Derg regime, the end of Soviet support augured not only at the loss of Eritrea but

more ominously, the end of its own existence. On March 17, 1988, Eritrean revolutionaries of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), anticipating a major Ethiopian offensive, struck first at Afabet, this pre-emptive attack dealing the Ethiopian Army a crushing defeat with 18,000 Ethiopian soldiers killed, wounded or captured; Ethiopia also lost some of its best-trained units. The EPLF also seized large stockpiles of weapons and ammunitions. By then, the rebels possessed tanks, armored carriers, and armed speedboats, and had advanced from guerilla warfare to openly fighting in pitched battles.

Ethiopia, Eritrea, and nearby countries.

(Taken from Eritrean War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

In September 1948, a special body called the Inquiry Commission, which was set up by the Allied Powers (Britain, France, Soviet Union, and United States),

failed to establish a future course for Eritrea and referred the matter to the United Nations (UN). The main obstacle to granting Eritrea its independence was that for much of its history, Eritrea was not a single political sovereign entity but had been a part of and subordinate to a greater colonial power, and as such, was deemed incapable of surviving on its own as a fully independent state. Furthermore, various

countries put forth competing claims to Eritrea. Italy

wanted Eritrea returned, to be governed for a pre-set period until the territory’s independence, an arrangement that was similar to that of Italian Somaliland. The Arab countries of the Middle East pressed for self-determination of Eritrea’s large Muslim population, and as such, called for Eritrea

to be granted its independence. Britain, as the current administrative power, wanted to partition Eritrea, with the Christian-population regions to be incorporated into Ethiopia and the Muslim regions to be assimilated into Sudan. Emperor Haile Selassie, the

Ethiopian monarch, also claimed ownership of Eritrea, citing historical and cultural ties, as well as the need for Ethiopia to have access to the sea through the Red Sea (Ethiopia had been landlocked after Italy established Eritrea).

Ultimately, the United States influenced the future course for Eritrea. The U.S. government saw Eritrea in the regional balance of power in Cold War politics: an independent but weak Eritrea could potentially fall to communist (Soviet) domination, which would destabilize the vital oil-rich Middle East. Unbeknown to the general public at the time, a U.S. diplomatic cable from Ethiopia to the U.S. State

Department in August 1949 stated that British officials in Eritrea believed that as much as 75% of the local population desired independence.

In February 1950, a UN commission sent to Eritrea to determine the local people’s political aspirations submitted its findings to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In December 1950, the UNGA, which was strongly influenced by U.S. wishes, released Resolution 390A (V) that called for establishing a loose federation between Ethiopia and Eritrea to be facilitated by Britain and to be realized no later than September 15, 1952. The UN plan, which subsequently was implemented, allowed Eritrea broad autonomy in controlling its internal affairs, including local administrative, police, and fiscal and taxation functions. The Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation would affirm the sovereignty of the Ethiopian monarch whose government would exert jurisdiction over Eritrea’s foreign affairs, including

military defense, national finance, and transportation.

In March 1952, under British initiative, Eritrea elected a 68-seat Representative Assembly, a legislature composed equally of Christians and

Muslim members, which subsequently adopted a constitution proposed by the UN. Just days before the September 1952 deadline for federation, the Ethiopian government ratified the Eritrean constitution and upheld Eritrea’s Representative Assembly as the renamed Eritrean Assembly. On September 15, 1952, the Ethiopian-Eritrean

Federation was established, and Britain turned over administration to the new authorities, and withdrew from Eritrea.

However, Emperor Haile Selassie was determined to bring Eritrea under Ethiopia’s full authority. Eritrea’s head of government (called Chief Executive who was elected by the Eritrean Assembly) was forced to resign, and successors to the post were appointed by the Ethiopian emperor. Ethiopians were appointed to many high-level Eritrean government posts. Many Eritrean political parties were banned and press censorship was imposed. Amharic, Ethiopia’s official language, was imposed, while

Arabic and Tigrayan, Eritrea’s main languages, were replaced with Amharic as the medium for education. Many local businesses were moved to Ethiopia, while local tax revenues were sent to Ethiopia. By the early 1960s, Eritrea’s autonomy status virtually had ceased to exist. In November 1962, the Eritrean Assembly, under strong pressure from Emperor Haile Selassie, dissolved the Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation and voted to incorporate Eritrea as Ethiopia’s 14th province.

Eritreans were outraged by these developments. Civilian dissent in the form of rallies and demonstrations broke out, and was dealt with

harshly by Ethiopia, causing scores of deaths and injuries among protesters in confrontations with

security forces. Opposition leaders, particularly those calling for independence, were suppressed, forcing many to flee into exile abroad; scores of their supporters also were jailed. In April 1958, the first organized resistance to Ethiopian rule emerged with the formation of the clandestine Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM), consisting originally of Eritrean exiles in Sudan. At its peak in Eritrea, the ELM had some 40,000 members who organized in cells of 7 people and carried out a campaign of destabilization, including engaging in some militant actions such as assassinating government officials, aimed at forcing the Ethiopian government to reverse some of its centralizing policies that were undercutting Eritrea’s autonomous status under the federated arrangement with Ethiopia. By 1962, the government’s anti-dissident campaigns had weakened the ELM, although the militant group continued to exist, albeit

with limited success. Also by 1962, another Eritrean nationalist organization, the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), had emerged, having been organized in July

1960 by Eritrean exiles in Cairo, Egypt which in contrast to the ELM, had as its objective the use of armed force to achieve Eritrean’s independence.

In its early years, the ELF leadership, called the “Supreme Council”, operated out of Cairo to more effectively spread its political goals to the international community and to lobby and secure military support from foreign donors.

March 15, 2020

March 16, 1979 – Sino-Vietnamese War: Chinese forces withdraw from Vietnam

Chinese forces of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) attacked Lang Son, taking the city on March 4, 1979 after bitter house-to-house fighting. The following day, the Chinese government, declaring that it had sufficiently punished Vietnam, ordered its forces to withdraw from Vietnam. On their withdrawal, the PLA carried out a scorched-earth campaign, destroying buildings, properties, and farmlands, before crossing into China on March 16, 1979. But the PLA did not cede the 60 km2 strip of disputed border territory which it had captured during the invasion. The continued hold by the

Chinese of this territory would become a source of dispute in the ensuing decade.

The Sino-Vietnamese War was over. No official casualty figures exist, as China and Vietnam have not released their battlefield human losses incurred during the war. But perhaps the PLA suffered some 60,000 troops killed or wounded, with Vietnamese forces suffering a nearly equivalent number of casualties.

China and Vietnam, and other countries in Southeast Asia.

(Taken from Sino-Vietnamese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background

In late December 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia,

and within two weeks, its forces toppled the Khmer Rouge government, and set up a new Cambodian government that was allied with itself (previous article). The Khmer Rouge had been an ally of China,

and as a result, Chinese-Vietnamese relations deteriorated. In fact, relations between China and Vietnam had been declining in the years prior to the invasion.

During the Vietnam War (separate article), North Vietnam received vital military and economic support from China, and also from the Soviet Union. But as Chinese-Soviet relations had been declining since the early 1960s (with both countries nearly going to war in 1969), North Vietnam was forced to maintain a delicate balance in its relations between its two patrons in order to continue receiving badly needed weapons and funds. But after the communist victory

in April 1975, the reunified Vietnam had a gradual falling out with China over two issues: the persecution of ethnic Chinese in Vietnam, and a disputed border.

Following the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese central government in Hanoi launched a campaign to break down the free-market economic system in the former South Vietnam to bring it in line with the country’s centrally planned socialist economy. Ethnic Chinese in Vietnam (called Hoa), who controlled the South’s economy, were subject to severe economic measures. Many Hoa were forced to close down their businesses, and their assets and properties were seized by the government. Vietnamese citizenship to the Hoa was also voided. The government also forced tens of thousands of Hoa into so-called “New Economic Zones”, which were located in remote mountainous regions. There, they worked as peasant farmers under harsh conditions. The Hoa also were suspected by the government of plotting or carrying out subversive activities in the North.

As a result of these repressions, hundreds of thousands of Hoa (as well as other persecuted ethnic minority groups) fled the country. The Hoa who lived in the North crossed overland into China, while those in the South went on perilous journeys by sea using only small boats across the South China Sea for Southeast Asian countries. Vietnam also initially refused to allow Chinese ships that were sent by the Beijing government to repatriate the Hoa back to China. The Hanoi government also denied that the persecution of Hoa was taking place. Then when the Hanoi government allowed the Hoa to leave the

country, it imposed exorbitant fees before granting exit visas. Furthermore, North Vietnamese troops in the northern Vietnamese frontier regions forced ethnic Chinese who lived there to relocate to the Chinese side of the China-Vietnam border.

Vietnam and China also had a number of long-standing territorial disputes, including over a piece of land with an area of 60 km2, but primarily in the Gulf

of Tonkin, and in the Spratly and Paracel Islands

in the South China Sea. The dispute over the Spratly and Paracel Islands became even more pronounced

after it was speculated that the surrounding waters potentially contained large quantities of petroleum resources.

The Vietnamese also generally distrusted the Chinese for historical reasons. The ancient Chinese

emperors had long viewed Vietnam as an integral part of China, and brought the Vietnamese under direct Chinese rule for over a millennium (111 B.C.–938 A.D.). Then during the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese accepted Chinese military support with some skepticism, and later claimed that China provided aid in order to bring Vietnam under the Chinese sphere of influence. Furthermore, China’s improving relations with the United States following U.S. President Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijing in 1972 also was viewed by North Vietnam as a betrayal to its reunification struggle during the Vietnam War. In May 1978, with Cambodian-Vietnamese relations almost at the breaking point, China cut back on economic aid to Vietnam; within two months, it was ended completely. Also in 1978, China closed off its side of the Chinese-Vietnamese land border.

Meanwhile, just as its ties with China were breaking down, Vietnam was strengthening its relations with the Soviet Union. In 1975, the Soviets provided large financial assistance to Vietnam’s post-war reconstruction and five-year development program. Two events in 1978 brought Vietnam firmly

under the Soviet sphere of influence: in June, Vietnam became a member of the Soviet-led Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) and in November, Vietnam and the Soviet Union signed the “Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation”, a mutual defense pact that stipulated Soviet military and economic support to Vietnam in exchange for the Vietnamese allowing the Soviets to use air and naval facilities in Vietnam. The treaty also formalized the Soviet and Chinese domains in Indochina, with Vietnam aligned with the Soviet Union, and Cambodia aligned with China.

China now saw itself surrounded by the Soviet Union to the north and Vietnam to the south. But Vietnam also saw itself threatened by hostile forces in the north (China) and southwest (Cambodia). Vietnam then made its move in late December 1978, when it invaded Cambodia and conquered the country in a lightning offensive. Chinese authorities were infuriated, as their ally, the Khmer Rouge regime, had been toppled by the Vietnamese invasion. Since one year earlier (1978), tensions between China and Vietnam had been rising, causing

many incidents of armed clashes and cross-border raids. In January 1979, the Hanoi government accused China of causing over 200 violations of Vietnamese territory.

By February 1979, 30 divisions of the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA (China’s armed forces) were massed along the border. On February 15, 1979, China announced its plan to attack Vietnam. Also on that day, China’s 1950 “Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance” with the Soviet Union ended, thus freeing China from its obligation to pursue non-aggression against a Soviet ally. Because of the threat of Soviet intervention from the north, on February 16, Chinese authorities declared that it was also prepared to go to war with the Soviet Union. By this time, the bulk of Chinese forces (some 1.5 million troops) were concentrated along the northern border, while 300,000 Chinese civilians in these border regions were evacuated.

March 14, 2020

March 15, 1991 – Gulf War: Sheikh Jaber III returns to Kuwait