Daniel Orr's Blog, page 109

January 22, 2020

January 23, 1991 – Rwandan Civil War: Rebels attack the northern town of Ruhengeri

On January 23, 1991, forces of the insurgent Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by Paul Kagame, attacked the northern town of Ruhengeri, where they

seized weapons from the local army barracks. They withdrew the next day when government forces arrived. Then for the next 18 months, Kagame used

guerilla tactics to elude the Rwandan Army, while staging pin-prick attacks on isolated military outposts, patrols, and convoys. Despite its superiority in personnel and weapons, the Rwandan Army was unable to inflict a decisive defeat on the rebels.

Africa showing location of Rwanda and nearby countries.

Then in June 1992, with mediation by the Organization of African Unity, or OAU, the government and Kagame signed a ceasefire agreement in Arusha, Tanzania. OAU officials arrived in Rwanda to monitor the ceasefire. Later in 1992,

the government and the rebels held peace talks which, however, failed to produce a clear settlement. Powerful Hutu radicals in the Rwandan government rejected the peace process, as they were opposed to making any deals with Tutsis. These radical Hutus formed civilian armed groups, the most notorious

being the “death squads” known as the Interahamwe, whose only motive was to kill Tutsis. Soon, the Interahamwe began attacking Tutsi civilians.

(Taken from Rwandan Civil War and Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Rwandan Genocide

On April 6, 1994, President Habyarimina and Burundi’s head of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira, were killed by undetermined assassins when their plane was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade as it was about to land in Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government took over power in Rwanda.

Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the new government unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murder Tutsis and

moderate Hutus on sight. Over the next several weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”, large numbers of civilians were murdered in Kigali and throughout the country. No place was

safe; in some instances, even Catholic churches were the scenes of the massacres of thousands of Tutsis where they had taken refuge.

The attackers used clubs, spears, firearms, and grenades, but their main weapon was the machete, with which they had trained extensively and which they used to hack away at their victims. At the urging of local officials, Hutu civilians joined in the killing frenzy, and turned against their Tutsi neighbors, acquaintances, and even relatives. In many cases, the threat of being killed for appearing sympathetic to

Tutsis forced many otherwise disinterested Hutus to participate.

The Rwandan Army provided the Interahamwe with a list of Tutsis to be killed, and raised road blocks to prevent any escape. The death toll in the Rwandan Genocide ranges from between 800,000 to one million; some 10% of the fatalities were moderate

Hutus. The genocide lasted for about 100 days, from between April 6 to July 15, producing a killing rate of 10,000 persons a day. The speed by which it was

carried out makes the Rwandan Genocide the fastest in history. (By comparison, the Holocaust in Europe during World War II, although producing a much

higher death toll, was carried out over a number of years.)

During the course of the genocide, the UN force in Rwanda was ordered not to intervene by the UN Secretary General. In any case, the UN force was seriously undermanned and only lightly armed to stop the widespread violence.

The UN peacekeepers, however, managed to protect the civilians inside their zone of authority.

Shortly after the violence began, foreign diplomats and their staff from the various embassies in Kigali

fled the country. Other civilian expatriates were evacuated as well. The international community, including the Western powers, chose not to intervene

in the genocide or misread the upsurge in violence as just another combat phase in the civil war.

January 21, 2020

January 22, 1981 – The start of the Paquisha War, when a Peruvian transport helicopter is attacked in the Comaina Valley

On January 22, 1981, the Paquisha War between Peru and Ecuador broke out when a Peruvian transport helicopter was fired upon in the Comaina Valley, in a Peruvian-controlled area that had been seized by Ecuadorian troops. Subsequently, Peruvian authorities discovered that the Ecuadorians had

constructed three outposts in the Comaina Valley along the eastern slope of the Condor. The Ecuadorians named their outposts Mayaicu, Machinaza, and Paquisha, with the latter for which

the coming war was named. In an Organization of American States (OAS) foreign ministers meeting held on February 2, 1981, the Peruvian representative denounced the Ecuadorian action. Then in the next few days, Peruvian forces attacked the outposts, forcing the Ecuadorians to withdraw to their side of the Condor Mountain Range. By February 5, Peru had regained control of the whole Comaina Valley and also seized Ecuadorian military supplies and equipment that had been abandoned.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, producing tensions and wars between the two countries.

(Taken from Paquisha War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

In July 1941, Ecuador and Peru (Map 38) fought a war for possession of disputed territory located in the

Amazon rainforest. After the war, both countries signed, in January 29, 1942, the Rio Protocol (officially called the Protocol of Peace, Friendship, and Boundaries), which called for establishing the international border between Ecuador and Peru. Four guarantor countries of the Rio Protocol, namely, the United States, Brazil, Argentina, and Chile, were tasked to under the border delineation process. Since much of the territory where the border would pass was thick Amazonian jungle, U.S. planes were brought in to undertake aerial surveys and thereby upgrade the existing Spanish colonial-era maps of the region. Consequently, the Mixed Border Commission, which was composed of technical teams from Ecuador, Peru, and the four guarantor countries, succeeded in plotting much of the 1,600 kilometers of the

Ecuador-Peru border.

The U.S. aerial maps, released in February 1947, showed an error in the technical descriptions used as the basis of the Rio Protocol in the watered areas adjoining the Condor Mountain Range (Spanish: Cordillera del Condor). In particular, the Cenepa River, situated between the Zamora and Santiago Rivers, was discovered to be much more extensive than previously thought. As a result of the flaw, Ecuador wanted to renegotiate the border along the 78-kilometer length of the Condor Mountain Range, a proposal that was rejected by Peru. Furthermore, the U.S. maps showed two divortium aquariums, and not just one, between the Zamora and Santiago Rivers, as indicated in Article VIII of the Rio Protocol, a discrepancy that eventually led the

Ecuadorian government to declare that the Protocol, being flawed, was impossible to implement.

Two years earlier, in July 1945, when the length of the Cenepa River was yet undetermined and only one divortium aquarium was thought to exist in

the Condor, the question of the placement of the border in the Condor Mountain Range was brought before Brazilian Naval Captain Braz Dias de Aguiar. The multinational guarantors of the Rio Protocol had tasked Captain Dias de Aguiar, a technical expert, to mediate on the disputes that should arise. In his

decision, Captain Dias de Aguiar, declared that the Condor Mountain Range was the border; this decision was accepted by Ecuador and Peru.

As a result of the discrepancies in the Rio Protocol revealed by the U.S. aerial maps, the Ecuadorian government pulled out its representatives from the Mixed Border Commission in September 1948, and withdrew altogether from the Demarcation Committee in 1953. The demarcation of the border then stopped, with all but 78 kilometers of the whole

length left unsettled. In September 1960, Ecuador

declared the Rio Protocol as null and void, stating that the Ecuadorian government during the 1941 war, had been forced under duress to accede to the

Protocol, as Peruvian forces were occupying Ecuadorian territory at that time.

Consequently, no major diplomatic initiatives were made to resolve the disputed border area. For

the next several years, the heavily forested region was unexplored and unsettled, although a few indigenous tribes resided there. The area soon became militarized as Ecuador and Peru sent troops to stake claims, setting up bunkers and outposts, with the Ecuadorians positioned at the top and on the western slopes of the Condor Mountain Range and Peruvians along the eastern slopes and adjacent Comaina Valley areas. Supplies to these army positions were sent by helicopters, as the region practically did not have any roads.

January 20, 2020

January 21, 1995 – Cenepa War: Peru lands troops behind Ecuadorian outposts in the disputed Condor-Cenepa border region, triggering war

By early January 1995, the strong Peruvian presence was being felt with an increase in military activities near the Ecuadorian forward outposts. Ecuadorian and Peruvian patrols encountered each other on January 9 and January 11, with the latter

encounter leading to an exchange of gunfire. Then on January 21, 1995, Peruvian troops were landed by helicopter behind the Ecuadorian outposts in preparation for a Peruvian full offensive. The infiltration was discovered when an Ecuadorian patrol spotted some 20 Peruvian soldiers setting up a heliport. Ecuadorian Special Forces were called in; after a two days’ trek through the jungle, the Ecuadorians located the Peruvian camp. In the

ensuing firefight, the Ecuadorians dispersed the Peruvians. A number of Peruvians were killed, while the abandoned weapons and supplies in the camp were seized. The Cenepa War was on.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, producing tensions and wars between the two countries.

(Taken from Cenepa War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

The 1981 Paquisha War (previous article) between Ecuador and Peru left unsettled the border dispute regarding sovereignty over the Condor Mountain range and the Cenepa River system located inside the Amazon rainforest. Peruvian forces achieved a tactical victory by destroying three Ecuadorian forward outposts and re-established control over the whole eastern side of the Condor range, although the Ecuadorian government continued to claim ownership over the whole Condor-Cenepa region.

In the years following the Paquisha War, the two sides strengthened their areas of control in the region, with the Ecuadorians occupying the peaks

and western slope of the Condor range, and the Peruvians at the Condor’s eastern slope and Cenepa

Valley. Because of the thick forest cover, Ecuadorian

and Peruvian patrols often accidentally encountered each other, which at the very worst, led to exchanges of gunfire, but generally ended without incident, as the two sides had agreed to abide by the Cartillas de Seguridad y Confianza (Guidelines for Security and Trust), which lay down the rules to prevent unnecessary bloodshed.

In November 1994, a Peruvian army patrol came upon an enemy outpost and was told by the Ecuadorian commander there that the location was

situated inside the Ecuadorian Army’s area of control. The Peruvian Army soon learned that the outpost, which the Ecuadorians named “Base Sur”, was located on the eastern slope of the Condor, and therefore in the area traditionally under Peruvian control. Thereafter, the Ecuadorian and Peruvian local commanders met a number of times to try and work out a resolution, but nothing came out of the meetings.

With tensions rising by December 1994, Ecuador and Peru began sending reinforcements and large quantities of weapons and military equipment to the disputed zone, a difficult and hazardous operation

(particularly for Peru’s Armed Forces because of the greater distance) which required air transports because of the absence of roads leading to the Condor region.

Apart from “Base Sur”, the Ecuadorians had set up a number of other outposts, including “Tiwintza” and “Cueva de los Tayos”, and the larger “Coangos”, near the top of the Condor Mountain. The camps’ defenses were strengthened by new minefields laid out at the approaches, and the installation of anti-aircraft batteries and multiple-rocket launchers; a further boost was provided by the arrival of Ecuadorian Special Forces and specialized teams equipped with hand-held surface-to-air missile launchers to be used against Peruvian planes.

By early January 1995, the strong Peruvian presence was being felt with an increase in military activities near the Ecuadorian forward outposts. Ecuadorian and Peruvian patrols encountered each other on January 9 and January 11, with the latter

encounter leading to an exchange of gunfire. Then on January 21, Peruvian troops were landed by helicopter behind the Ecuadorian outposts in preparation for a Peruvian full offensive. The infiltration was discovered when an Ecuadorian patrol spotted some 20 Peruvian soldiers setting up a heliport. Ecuadorian Special Forces were called in;

after a two days’ trek through the jungle, the Ecuadorians located the Peruvian camp. In the ensuing firefight, the Ecuadorians dispersed the Peruvians. A number of Peruvians were killed, while the abandoned weapons and supplies in the camp were seized.

January 19, 2020

January 20, 1948 – Indian-Pakistani War of 1947: The UN Security Council passes Resolution 39

On January 20, 1948, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 39 where it offered to set up a UN Commission to assist in resolving the conflict in Kashmir. The proposed UN Commission was only realized with UNSC Resolution 47 passed on April 21, 1948. Resolution 47 recommended a three-step process to establish peace: that Pakistan withdraw its citizens from Kashmir, that India progressively reduce its forces there, and that a plebiscite be held in Kashmir to determine its political future. Through mediation efforts by the UN Commission, India and Pakistan agreed to the commission’s two resolutions, and a ceasefire was achieved in early 1949. But as hostility and distrust remained, in the end, the UN Commission declared that its mission in Kashmir had failed.

India and Pakistan. Diagram shows India and the two “wings” of Pakistan (West Pakistan and East Pakistan) on either side. Kashmir, the battleground during the Indian-Pakistani War of 1947, is located in the northern central section of the Indian subcontinent.

(Taken from Indian-Pakistani War of 1947 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

On August 15, 1947, the new state of Kashmir (Map 1) found itself geographically located next to India and Pakistan, two rival countries that recently had gained their independences after the cataclysmic partition of the Indian subcontinent. Fearing the widespread violence that had accompanied the birth of India and Pakistan, the Kashmiri monarch, who was a Hindu, chose to remain neutral and allow Kashmir

to be nominally independent in order to avoid the same tragedy from befalling his mixed constituency of Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs.

Pakistan exerted diplomatic pressure on Kashmir, however, as the Pakistani government had significant strategic and economic interests in the former Princely State. Most Pakistanis also shared a common religion with the overwhelmingly Muslim Kashmiri population. India also nurtured ambitions on Kashmir and wanted to bring the former Princely

State into its sphere of influence. After Kashmir gained back its sovereignty, the British colonial troops departed; consequently, Kashmir was left only with a small native army to enforce peace and order.

On October 22, 1947, when rumors surfaced that Kashmir would merge with India, Muslim Kashmiris in the state’s western regions broke out in rebellion. The rebels soon were joined by Pakistani fighters who entered the Kashmiri border from Pakistan. The rebels and Pakistanis seized the towns of Muzzafarabad and Dommel (Map 1) where they disarmed the Kashmiri troops, who thereafter also joined the rebels.

Within a few days, the rebellion had spread to Baramula and threatened Srinagar, Kashmir’s

capital. The Kashmiri ruler fled to India, where he pleaded for military assistance with the Indian government. The Indians agreed on the condition that Kashmir be merged with India, to which the Kashmiri ruler gave his consent. Soon thereafter, Kashmir’s status as a sovereign state ended. On October 27, 1947, Indian forces arrived in Srinagar

and expelled the rebels, who by this time, had entered the capital.

Earlier, India and Pakistan had jointly agreed to a policy of non-intervention in Kashmir’s internal affairs. But with the territorial merger of India and Kashmir, Indian forces gained the legal authority to occupy the former Princely State. The Pakistani government now ordered its forces to invade Kashmir. The Pakistan Armed Forces chief of staff, however, who was also a British Army officer, refused to comply, since doing so would pit him against Lord

Mountbatten, the British Governor General of India, who had ordered the Indian troops to Kashmir. With the Pakistani military leadership in a crisis and its army placed on hold, the Indian Army virtually deployed unopposed in Kashmir and secured much of the state.

In early November 1947, the Gilgit Scouts, a civilian paramilitary based in the Gilgit region in northern Kashmir, broke out in rebellion over some disagreement with the Kashmiri government. The Gilgit Scouts soon were joined by tribal militias from Chitral in northern Pakistan. Together, they wrested control of the whole northern Kashmir.

By mid-November 1947, the Indian Army’s counter-attacks in the west had recaptured Uri and Baramula and had pushed back the coalition of Kashmir rebels and Pakistani fighters toward the

Pakistani border. Further Indian advances were stalled by the onset of winter, however, as the Indian troops were not prepared for fighting in the cold, high altitudes and were encountering logistical problems.

With the Indian forces settling down to a defensive position, the rebel coalition forces went on the attack and captured the towns of Kotli and Mirpur in the south, thereby extending the battle lines on the west to a nearly north to south axis. In

southwest Kashmir, the Indians took Chamb, and fortified the key city of Jammu, which remained in

their possession throughout the war.

With the arrival of spring weather in May 1948, the Indians launched a number of offensive operations in the west and retook the towns of

Tithwail, Keran, and Gurais. In the north, a daring Indian attack using battle tanks at high altitudes captured Ziji-La Pass and Dras. But later that year, the arrival of Pakistan Army units in rebel-held Kashmir in the west stopped further significant Indian advances.

Pakistan Army units also were deployed in Kashmir’s High Himalayas to augment the Gilgit-Chitral rebel coalition forces. Together, they advanced south and captured Skardu and Kargil, and threatened Leh. A counter-attack by the Indian Army in May 1948, however, stopped the Pakistan Army-led forces, which were pushed back north of Kargil.

In early 1948, the battle lines settled in northern and western Kashmir – these lines held for the

rest of the war. As the two sides prepared to settle down for the winter, the Indian government asked the United Nations (UN) to mediate in the war.

Meanwhile, the Pakistan Army launched a surprise offensive in the west which, however, did not significantly alter the front lines.

The UN released two previously approved resolutions for a ceasefire and the future of Kashmir, which were accepted by India and Pakistan. The war officially ended on December 31, 1948.

January 18, 2020

January 19, 1960 – Algerian War of Independence: French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle fires General Jacques Massu

French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle weakened the French Algerian Army’s radicalism when on January 19, 1960, he dismissed General Jacques Massu, victor of the Battle of Algiers, who had threatened insubordination by declaring that he and other officers may choose to not follow de Gaulle’s orders. Three months later, in April 1960, de Gaulle reassigned General Challe, commander-in-chief of the French Algerian Army, away from Algeria, just as the latter was on the verge of inflicting a decisive defeat on the FLN “internal” forces.

(Taken from Algerian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

General Massu’s dismissal sparked the “Week of Barricades” (French: La semaine des barricades) starting on January 24, 1960, where some 30,000 pieds-noirs took to the streets, seized government buildings, and set up barricades in an act of defiance against de Gaulle’s government.

Viewing these acts as a threat to his regime, de Gaulle, donning his World War II brigadier general’s uniform in a televised broadcast on January 29, 1960, appealed to the French people and armed forces to remain loyal to France. The French 10th Parachute Division, which had won the Battle of Algiers for France, did not launch suppressive action against the barricades, but the refusal of the French Army to join the protesters doomed the uprising. The French 25th Parachute Division finally broke up the barricades; casualties for the protesters were 22 dead and 147

wounded, and for the Algerian gendarmes (police), 14 dead and 123 wounded.

A further sign of de Gaulle’s shift in policy toward Algeria took place in June 1960 when he took up a truce offer by a regional leader of the National Liberation Front (FLN; French: Front de Libération Nationale) and negotiate a “warrior’s peace” (French: la paix des braves); however, peace talks held in Melun (in France) failed. Then by November 1960, de Gaulle had decided on Algeria’s fate. On November 4, he declared that “there will be an Algerian republic one day, which will not be France”. He further stated a “new course”, i.e. an “emancipated Algeria…which,

if the Algerians so desire…will have its own government, its institutions, and its laws”. De Gaulle then prepared a referendum for France and Algeria to determine whether Algeria should be given self-determination.

France’s possessions in Africa included the vast French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa (shaded on the left).

By the early 1960s, de Gaulle was shifting his foreign and economic priorities to Europe primarily by boosting France’s rapidly improving relations with Germany, which ultimately led to the signing, together with Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg, of the Treaty of Rome in March 1957 that established the European Economic Council (EEC, precursor of the European Union). Furthermore, in the context of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union, de Gaulle wanted to make France, despite its alignment with the West through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a political and military “third force” separate from the two superpowers.

De Gaulle’s plan to disengage from Algeria was merely one episode in the decolonization process that France had undertaken in Africa in 1960: by the end of that year, the once vast French West Africa had given way to 13 independent countries. Similarly, the British Empire (which together with France held the greatest colonial territorial share of

Africa) also had begun the process of decolonization in 1960 (apart from Ghana, which gained independence in 1957), having been triggered in February of that year when British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan issued his “Wind of Change”

speech, declaring that in Africa, “the wind of change is blowing” and “whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact”. Also in 1960, Belgium turned over political authority to a newly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo and would do the same to Rwanda and Burundi in 1962. Portugal and Spain tried to hold onto their African possessions, but in the ensuing years, became mired in long and bitter independence wars against indigenous nationalist movements.

Furthermore, on December 14, 1960, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) passed Resolution 1514 (XV) titled “Declaration of the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”, which established decolonization as a fundamental principle of the UN. Five days later, on December 19, the UN released UNGA Resolution 1573 that recognized the right of self-determination of the Algerian people.

On January 8, 1961, in a referendum held in France and Algeria, 75% of the voters agreed that Algeria must be allowed self-determination. The

French government then began to hold secret peace negotiations with the FLN. In April 1961, four retired French Army officers (Generals Salan, Challe, André Zeller, and Edmond Jouhaud, and assisted by radical elements of the pied-noir community) led the French command in Algiers in a military uprising that deposed the civilian government of the city and set up a four-man “Directorate”. The rebellion, variously known as the 1961 Algiers Putsch (French: Putsch d’Alger) or Generals’ Putsch

(French: Putsch des Généraux), was a

coup to be carried out in two phases: taking over authority in Algeria with the defeat of the FLN and establishment of a civilian government; and overthrowing de Gaulle in Paris by rebelling paratroopers based near the French capital.

De Gaulle invoked the constitution’s provision that gave him emergency powers, declared a state of emergency in Algeria, and in a nationwide broadcast on April 23, appealed to the French Army and civilian population to remain loyal to his government. The

French Air Force flew the empty air transports from Algeria to southern France to prevent them from being used by rebel forces to invade France, while the French commands in Oran and Constantine

heeded de Gaulle’s appeal and did not join the rebellion. Devoid of external support, the Algiers

uprising collapsed, with Generals Challe and Zeller being arrested and later imprisoned by military authorities, together with hundreds of other mutineering officers, while Generals Salan and Jouhaud went into hiding to continue the

struggle with the pieds-noirs against Algerian independence.

On April 28, 1961, in the midst of the uprising, French military authorities test-fired France’s first atomic bomb in the Sahara Desert, moving forward the date of the detonation ostensibly to prevent the

nuclear weapon from falling into the hands of the rebel troops. The attempted coup dealt a serious blow to French Algeria, as de Gaulle increased efforts to end the war with the Algerian

nationalists.

In May 1961, the French government and the GPRA (the FLN’s government-in-exile) held peace talks at Évian, France, which proved contentious and difficult. But on March 18, 1962, the two sides signed an agreement called the Évian Accords,

which included a ceasefire (that came into effect the following day) and a release of war prisoners; the agreement’s major stipulations were: French

recognition of a sovereign Algeria; independent Algeria’s guaranteeing the protection of the pied-noir community; and Algeria allowing French military

bases to continue in its territory, as well as establishing privileged Algerian-French economic and trade relations, particularly in the development

of Algeria’s nascent oil industry.

In a referendum held in France on April 8, 1962, over 90% of the French people approved of the Évian Accords; the same referendum held in Algeria on July 1, 1962 resulted in nearly six million voting in favor of the agreement while only 16,000 opposed it (by this time, most of the one million pieds-noirs had or were in the process of leaving Algeria or simply recognized

the futility of their lost cause, thus the extraordinarily low number of “no” votes).

However, pied-noir hardliners and pro-French Algeria military officers still were determined to derail the political process, forming one year earlier (in January 1961) the “Organization of the Secret

Army” (OAS; French: Organisation de l’armée secrète) led by General Salan, in a (futile) attempt to stop the 1961 referendum to determine Algerian self-determination. Organized specifically as a terror militia, the OAS had begun to carry out violent militant acts in 1961, which dramatically

escalated in the four months between the signing of the Évian Accords and the referendum on Algerian independence. The group hoped that its terror campaign would provoke the FLN to retaliate, which

would jeopardize the ceasefire between the government and the FLN, and possibly lead to a resumption of the war. At their peak in March 1962, OAS operatives set off 120 bombs a day in Algiers, targeting French military and police, FLN, and Muslim civilians – thus, the war had an ironic twist, as France and the FLN now were on the same side of the conflict against the pieds-noirs.

The French Army and OAS even directly engaged each other – in the Battle of Bab el-Oued, where French security forces succeeded in seizing the OAS stronghold of Bab el-Oued, a neighborhood in Algiers, with combined casualties totaling 54 dead and 140 injured. The OAS also targeted prominent Algerian Muslims with assassinations but its main target was

de Gaulle, who escaped many attempts on his life. The most dramatic of the assassination attacks on de Gaulle took place in a Paris suburb where a group of gunmen led by Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, a French

military officer, opened fire on the presidential car with bullets from the assailants’ semi-automatic rifles barely missing the president. Bastien-Thiry, who was not an OAS member, was arrested, put on trial, and later executed by firing squad.

In the end, the OAS plan to provoke the FLN into launching retaliation did not succeed, as the Algerian revolutionaries adhered to the ceasefire. On June 17, 1962, the OAS the FLN agreed to a ceasefire. The

eight-year war was over. Some 350,000 to as high as one million people died in the war; about two million Algerian Muslims were displaced from their homes, being forced by the French Army to relocate to guarded camps.

Aftermath of the Algerian War of Independence

On July 3, 1962, two days after the second referendum for independence, de Gaulle recognized the sovereignty of Algeria. Then on July 5, 1962, exactly 132 years after the French invasion in 1830, Algeria declared independence and in September 1962, was given its official name, the “People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria” by the country’s National Assembly.

In the months leading up to and after Algeria’s independence, a mass exodus of the pied-noir community took place, with some 900,000 (90% of the European population) fleeing hastily to France. The European Algerians feared for their lives despite a stipulation in the Évian Accords that independent Algeria must respect the rights and properties of the pied-noir community in Algeria. Some 100,000 would remain, but in the 1960s through 1970s, most were forced to leave as well, as the war had scarred

permanently relations between the indigenous Algerians and pieds-noirs, forcing the latter to abandon homes and properties under the threat of “the suitcase or the coffin” (French: “la valise ou le cercueil”). In France, the pieds-noirs experienced a difficult period of transition and adjustment, as many families had lived for many

generations in Algeria, which they regarded as their homeland. Moreover, they were criticized and held responsible by French mainlanders for the political, economic, and social troubles that the war had

caused to France. Algerian Jews, who feared persecution because of their opposition to Algerian independence, also fled Algeria en masse, with 130,000 Jews leaving for France where they held French citizenship; some 7,000 Jews also immigrated to Israel.

The harkis, or indigenous Algerians who had served in the French Army as regulars or auxiliaries, met a harsher fate. Disarmed after the war by their French military commanders and vilified by Algerians as traitors and French collaborators, the harkis and their families faced harsh retaliation by the FLN

and civilian mobs – some 50,000 to 100,000 harkis and their kin were killed, most in grisly circumstances. Some 91,000 harkis and their families did succeed in escaping to France under the aegis of their French commanders in violation of the orders of the French government.

The bitter effects of the war were felt in both countries for many years. Throughout the conflict,

France described its actions in Algeria as a “law and order maintenance operation”, and not war. Then in June 1999, thirty-seven years after the war ended, the French government admitted that “war” had indeed taken place in Algeria.

January 17, 2020

January 18, 1974 – Yom Kippur War: Egypt and Israel sign a Disengagement of Forces Agreement

On January 18, 1974, Egypt and Israel signed a Disengagement of Forces Agreement (also known as the Sinai I Agreement) following the Yom Kippur War. The agreement established a buffer zone between Egyptian and Israeli forces that was to be monitored by the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF). Only a limited amount of armament and forces were allowed inside the buffer zone.

On September 4, 1975, the two sides signed the Sinai Interim Agreement (also known as Sinai II Agreement), where they pledged that conflicts between them “shall not be resolved by military force but by peaceful means.” A further withdrawal was agreed and a bigger UN buffer zone was created.

These agreements paved the way for the Camp David Accords (in Camp David, Maryland), which led to the signing of the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty on March 26, 1979. This landmark peace treaty ended their state of war and normalized relations, and Egypt became the first Arab state to officially recognize Israel. Diplomatic relations between them came into effect in January 1980, with an exchange of ambassadors the following month. Israel withdrew from the Sinai, which Egypt promised to leave demilitarized. Israeli ships were allowed free passage through the Suez Canal, and Egypt recognized the Strait of Tiran and Gulf of Aqaba as international waterways.

(Taken from Wars of 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background of the Yom Kippur War

With its decisive victory in the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights were integral territories of Egypt and Syria, respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, together with other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”, that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant that only armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently was not received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egypt

carried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and government targets in the Sinai. In what is now known as the “War of Attrition”, Egypt was determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai. By way of retaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel, and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly became involved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israel and Egypt

to agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passed away. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President Anwar Sadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchly hostile to Israel, President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeli conflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations (UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign a peace treaty with Israel and recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to negotiate. President Sadat, therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging the Israelis from the Sinai. He decided that an Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israel to see the need for negotiations. Egypt began preparations for war. Large amounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, but ineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number of ruses. The Egyptian Army constantly

conducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoric eventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the true strength of its armed forces. The government also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its war

equipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated military hardware. Furthermore, when President Sadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egypt in July 1972, Israel

believed that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakened seriously. In fact, thousands of Soviet

personnel remained in Egypt and Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syrian

counterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized for war.

Israel’s intelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the date of the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbers of Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egypt and Syria attacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiers and the entire Israeli Air Force.

However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting a war and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carrying out a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War) to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur (which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, when most Israeli soldiers were on leave.

January 16, 2020

January 17, 1948 – Indonesian War of Independence: The signing of the Renville Agreement between the Netherlands and Indonesia

On January 17, 1948, representatives of the Netherlands and Indonesian revolutionaries signed the Renville Agreement (named after the USS Renville, a U.S. Navy ship where the

negotiations were held), which confirmed their respective territories in the Van Mook Line, and in the Dutch-held areas, a referendum would be held to

decide whether the residents there wanted to be under Indonesian or Dutch control. Furthermore, in exchange for Indonesian forces withdrawing from Dutch-held areas as stipulated in the Van Mook Line, the Dutch Navy would end its blockade of the ports.

Indonesia in Southeast Asia. During the colonial period, Indonesia was governed by the Netherlands and known as the Dutch East Indies.

The Indonesian Republic, already weakened politically and militarily, was undermined further when its Islamic supporters in now Dutch-controlled West Java objected to the Renville Agreement and broke away to form Darul Islam (“Islamic State”), with the ultimate aim of turning Indonesia into an Islamic country. It opposed both the Indonesian government and Dutch colonial authorities. Darul Islam subsequently would be defeated only in 1962, some 13 years after the war had ended.

The Indonesian Republic also faced opposition from its other erstwhile allies, the communists (of the Indonesian Communist Party) and the socialists (of the Indonesian Socialist Party), who in September 1948, seceded and formed the “Indonesian Soviet Republic” in Madiun, East Java. Fighting in September-October and continuing until December 1948 eventually led to the Indonesian Republic

quelling the Madiun uprising, with tens of thousands of communists killed or imprisoned and their leaders executed or forced into exile. Furthermore, the Indonesian Army itself was plagued with internal problems, because the government, suffering from acute financial difficulties and unable to pay the soldiers’ salaries, had disbanded a number of military units.

Major islands of Indonesia.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Indonesian War of

Independence

Sukarno’s proclamation of Indonesia’s independence de facto produced a state of war with the Allied powers, which were determined to gain control of the territory and reinstate the pre-war Dutch government. However, one month would pass before the Allied forces would arrive. Meanwhile, the Japanese East Indies command, awaiting the arrival of the Allies to repatriate Japanese forces back to Japan, was ordered by the Allied high command to stand down and carry out policing duties to maintain law and order in the islands. The Japanese stance toward the Indonesian Republic varied: disinterested Japanese commanders withdrew their units to avoid confrontation with Indonesian forces, while those sympathetic to or supportive of the revolution provided weapons to Indonesians, or allowed areas to be occupied by Indonesians. However, other Japanese commanders complied with the Allied orders and fought the Indonesian revolutionaries, thus becoming involved in the independence war.

In the chaotic period immediately after Indonesia’s independence and continuing for several months, widespread violence and anarchy prevailed (this period is known as “Bersiap”, an Indonesian word meaning “be prepared”), with armed bands called “Pemuda” (Indonesian meaning “youth”) carrying out murders, robberies, abductions, and other criminal acts against groups associated with the Dutch regime, i.e. local nobilities, civilian leaders, Christians such as Menadonese and Ambones, ethnic Chinese, Europeans, and Indo-Europeans. Other armed bands were composed of local communists or Islamists, who carried out attacks for the same reasons. Christian and nobility-aligned militias also were organized, which led to clashes between pro-Dutch and pro-Indonesian armed groups. These so-called “social revolutions” by anti-Dutch militias, which occurred mainly in Java and Sumatra, were motivated by various reasons, including political, economic, religious, social, and ethnic causes. Subsequently when the Indonesian government began to exert greater control, the number of violent incidents fell,

and Bersiap soon came to an end. The number of fatalities during the Bersiap period runs into the tens of thousands, including some 3,600 identified and 20,000 missing Indo-Europeans.

The first major clashes of the war occurred in late August 1945, when Indonesian revolutionary forces clashed with Japanese Army units, when the latter tried to regain previously vacated areas. The Japanese would be involved in the early stages of Indonesia’s independence war, but were repatriated to Japan by the end of 1946.

In mid-September 1945, the first Allied forces consisting of Australian units arrived in the eastern regions of Indonesia (where revolutionary activity was minimal), peacefully taking over authority from the commander of the Japanese naval forces there. Allied

control also was established in Sulawesi, with the provincial revolutionary government offering no resistance. These areas were then returned to Dutch

colonial control.

In late September 1945, British forces also arrived in the islands, the following month taking control of key areas in Sumatra, including Medan, Padang, and Palembang, and in Java. The British also occupied Jakarta (then still known, until 1949, as Batavia), with Sukarno and his government moving the Republic’s capital to Yogyakarta in Central Java. In October 1945, Japanese forces also regained control of Bandung and Semarang for the Allies, which they turned over to the British. In Semarang, the intense fighting claimed the lives of some 500 Japanese and 2,000 Indonesian soldiers.

January 15, 2020

January 16, 1979 – Iranian Revolution: The Shah of Iran and his family leave Iran for exile abroad

On January 16, 1979, the Shah, his wife Queen Farah, and their family left Iran for exile abroad, this decision also made at the urging of Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar in an effort to make reconciliation with the revolutionaries. The official reasons given for the departure were for the Shah to take a “vacation” and for medical treatment. Celebrations broke out across the country, with millions pouring into the streets and destroying all remaining symbols of the monarchy. The Shah’s departure was not the end of the conflict, however, as the revolutionaries did not approve of the Bakhtiar regime, viewing the Prime Minister as another of the Shah’s figureheads.

In an effort to establish his regime, Prime Minister

Bakhtiar invited revolutionary leaders to form a government of national unity. He freed the remaining political prisoners and promised to hold elections. But he also invited Ayatollah Khomeini to return to Iran, a move that would have dire consequences for his government.

On February 1, 1979, using a chartered Air France commercial plane, Ayatollah Khomeini

arrived in Tehran in triumph, with several millions of his supporters welcoming him and bringing the whole country into frenzy. Immediately, he announced his rejection of the Bakhtiar regime and on February 5, formed a “Provisional Islamic Revolutionary Government” led by his appointee, Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan, a moderate leftist non-cleric. Two rival governments now existed, each denouncing the other, but with Bakhtiar’s regime hopelessly isolated and desertions rife, receiving virtually no popular support, and propped up only by the military.

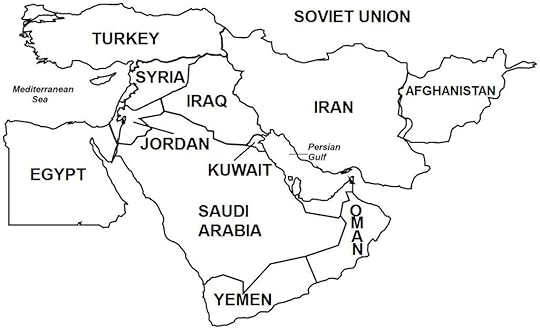

Iran in the Middle East.

(Taken from Iranian Revolution – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background of the

Iranian Revolution

Under the Shah, Iran developed close political, military, and economic ties with the United States, was firmly West-aligned and anti-communist, and received military and economic aid, as well as purchased vast amounts of weapons and military hardware from the United States. The Shah built a powerful military, at its peak the fifth largest in the world, not only as a deterrent against the Soviet

Union but just as important, as a counter against the Arab countries (particularly Iraq), Iran’s traditional rival for supremacy in the Persian Gulf region. Local opposition and dissent were stifled by SAVAK (Organization of Intelligence and National Security;

Persian: Sāzemān-e Ettelā’āt va Amniyat-e Keshvar), Iran’s CIA-trained intelligence and security agency that was ruthlessly effective and transformed the country into a police state.

Iran, the world’s fourth largest oil producer, achieved phenomenal economic growth in the 1960s and 1970s and more particularly after the 1973 oil crisis when world oil prices jumped four-fold, generating huge profits for Iran that allowed its government to embark on massive infrastructure construction projects as well as social programs such as health care and education. And in a country where society was both strongly traditionalist and religious (99% of the population is Muslim), the Shah led a government that was both secular and western-oriented, and implemented programs and policies that sought to develop the country based on western technology and some aspects of western culture. Iran’s push to westernize and secularize would be major factors in the coming revolution. The initial signs of what ultimately became a full-blown uprising took place sometime in 1977.

At the core of the Shiite form of Islam in Iran is the ulama (Islamic scholars) led by ayatollahs (the top clerics) in a religious hierarchy that includes other orders of preachers, prayer leaders, and cleric authorities that administered the 9,000 mosques around the country. Traditionally, the ulama was apolitical and did not interfere with state policies, but occasionally offered counsel or its opinions on government matters and policies.

In January 1963, the Shah launched sweeping major social and economic reforms aimed at shedding off the country’s feudal, traditionalist culture and to modernize society. These ambitious reforms, known as the “White Revolution”, included programs that

advanced health care and education, and the labor and business sectors. The centerpiece of these reforms, however, was agrarian reform, where the government broke up the vast agriculture landholdings owned by the landed few and distributed the divided parcels to landless peasants who formed the great majority of the rural population. While land reform achieved some measure of success with about 50% of peasants acquiring land, the program failed to win over the

rural population as the Shah intended; instead, the deeply religious peasants remained loyal to the clergy. Agrarian reform also antagonized the clergy, as most clerics belonged to wealthy landowning families who now were deprived of their lands.

Much of the clergy did not openly oppose these reforms, except for some clerics in Qom led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who in January 22, 1963 denounced the Shah for implementing the White Revolution; this would mark the start of a long

antagonism that would culminate in the clash between secularism and religion fifteen years later. The clerics also opposed other aspects of the White Revolution, including extending voting rights to women and allowing non-Muslims to hold government office, as well as because the reforms would reduce the cleric’s influence in education and family law. The Shah responded to Ayatollah Khomeini’s attacks by rebuking the religious establishment as being old-fashioned and inward-looking, which drew outrage from even moderate

clerics. Then on June 3, 1963, Ayatollah Khomeini launched personal attacks on the Shah, calling the latter “a wretched, miserable man” and likening the monarch to the “tyrant” Yazid I (an Islamic caliph of the 7th century). The government responded two days later, on June 5, 1963, by arresting and jailing

the cleric.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s arrest sparked strong protests that degenerated into riots in Tehran, Qom, Shiraz, and other cities. By the third day, the violence had been quelled, but not before a disputed number of protesters were killed, i.e. government cites 32 fatalities, the opposition gives 15,000, and other sources indicate hundreds.

Ayatollah Khomeini was released a few months later. Then on October 26, 1964, he again denounced the government, this time for the Iranian parliament’s recent approval of the so-called “Capitulation” Bill, which stipulated that U.S.

military and civilian personnel in Iran, if charged with committing criminal offenses, could not be prosecuted in Iranian courts. To Ayatollah Khomeini, the law was evidence that the Shah and the Iranian government were subservient to the United States. The ayatollah again was arrested and imprisoned; government and military leaders deliberated on his fate, which included execution (but rejected out of concerns that it might incite more unrest), and finally decided to exile the cleric. In November 1964, Ayatollah Khomeini was forced to leave the country; he eventually settled in Najaf, Iraq, where he lived for the next 14 years.

While in exile, the cleric refined his absolutist version of the Islamic concept of the “Wilayat al Faqih” (Guardianship of the Jurisprudent), which stipulates that an Islamic country’s highest spiritual and political authority must rest with the best-qualified member (jurisprudent) of the Shiite clergy, who imposes Sharia (Islamic) Law and ensures that state policies and decrees conform with this law.

The cleric formerly had accepted the Shah and the monarchy in the original concept of Wilayat al Faqih; later, however, he viewed all forms of royalty incompatible with Islamic rule. In fact, the ayatollah would later reject all other (European) forms of

government, specifically citing democracy and communism, and famously declared that an Islamic government is “neither east nor west”.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s political vision of clerical rule was disseminated in religious circles and mosques throughout Iran from audio recordings that

were smuggled into the country by his followers and which was tolerated or largely ignored by Iranian government authorities. In the later years of his exile, however, the cleric had become somewhat forgotten in Iran, particularly among the younger age groups.

January 14, 2020

January 15, 1975 – Angolan War of Independence: The signing of the Alvor Agreement, where Angola gains independence from Portugal

In January 1975, the Portuguese government met with the leaders of the three Angolan nationalist movements in a series of negotiations in Alvor, Portugal. These negotiations resulted in the signing of the Alvor Agreement on January 15, 1975, which contained several provisions. First, Angola’s

independence was set for November 11, 1975.

Second, during the ten-month interim period before independence, the three nationalist movements would form a power-sharing government to lead the

country, with the local Portuguese High Commissioner acting as the mediator for disputes. Third, a national constitution would be drafted, and parliamentary elections would be held in October

1975. Fourth, the nationalist groups’ armed wings would be integrated into the Portuguese colonial army; after the Portuguese had withdrawn from Angola, the core of Angola’s Armed Forces would have been formed.

Africa showing location of present-day Angola and other African countries that were involved in the Angolan War of Independence. South-West Africa (present-day Namibia) was then under South African rule.

Consequently, the Angolan nationalists formed a coalition government which, however, proved ineffective and barely functioned. Furthermore, none of the other provisions of the Alvor Agreement was truly implemented. And just as the Alvor Agreement ended Portugal’s war in Angola, it also sparked the so-called “decolonization war” (the hostilities during the interim period before Angola’s independence) among the three Angolan nationalist movements, particularly between FNLA and MPLA. Shortly after Portugal had set the date for Angola’s independence, the Angolan nationalist movements began aggressive recruitment campaigns and sought more weapons deliveries from their foreign backers.

(Taken from Angolan War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background

By the 1830s, Portugal had lost Brazil and had abolished its transatlantic slave trade. To replace these two valuable sources of income, Portugal

turned to develop its African possessions, including their interior lands. In Angola, agriculture was developed, with the valuable export crops of coffee and cotton being grown in vast plantations. The mining industry was expanded.

Portugal’s development of the local economy, including the construction of public infrastructures such as roads and bridges, was carried out using forced labor of black Africans, a system that was so harsh, ruthless, and akin to slavery. Consequently,

thousands of natives fled from the colony. Indigenous lands were seized by the colonial government. And while Angola’s economy grew, only the colonizers benefited, while the overwhelming majority of natives were neglected and deprived of education, health care, and other services.

After World War II, thousands of Portuguese immigrants settled in Angola. The world’s prices of coffee beans were high, prompting the Portuguese government to seek new white settlers in its African

colonies to lead the growth of agriculture. However, many of the new arrivals settled in the towns and cities, instead of braving the harsh rural frontiers. In urban areas, they competed for jobs with black Angolans who likewise were migrating there in large numbers in search of work. The Portuguese, being

white, were given employment preference over the natives, producing racial tension.

The late 1940s saw the rapid growth of nationalism in Africa. In Angola, three nationalist movements developed, which were led by “assimilados”, i.e. the few natives who had acquired the Portuguese language, culture, education, and

religion. The Portuguese officially designated “assimilados” as “civilized”, in contrast to the vast majority of natives who retained their indigenous lifestyles.

The first of these Angolan nationalist movements was the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola or MPLA (Portuguese: Movimento

Popular de Libertação de Angola) led by local communists, and formed in 1956 from the merger of the Angolan Communist Party and another nationalist movement called PLUA (English: Party of the United Struggle for Africans in Angola). Active in Luanda and other major urban areas, the MPLA drew its support from the local elite and in regions populated by the Ambundu ethnic group. In its formative years, it

received foreign support from other left-wing African nationalist groups that were also seeking the independences of their colonies from European rule. Eventually, the MPLA fell under the influence of the Soviet Union and other communist countries.

The second Angolan nationalist movement was the National Front for the Liberation of Angola or FNLA (Portuguese: Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola). The FNLA was formed in 1962 from the merger of two Bakongo regional movements that had as their secondary aim the resurgence of the once powerful but currently moribund Kingdom of Congo. Primarily, the FNLA wanted to end forced labor, which had caused hundreds of thousands of Bakongo natives to leave their homes. The FNLA operated out of Leopoldville (present-day Kinshasa) in the Congo from where it received military and financial support from the Congolese government. The FNLA was led by Holden Roberto, whose authoritarian rule and one-track policies caused the movement to experience changing fortunes during the coming war, and also bring about the formation of the third of Angola’s nationalist movements, UNITA.

UNITA or National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (Portuguese: União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola) was founded

by Jonas Savimbi, a former high-ranking official of the FNLA, over disagreements with Roberto. Unlike the

FNLA and MPLA, which were based in northern Angola, UNITA operated in the colony’s central and southern regions and gained its main support from the Ovibundu people and other smaller ethnic groups. Initially, UNITA embraced Maoist socialism

but later moved toward West-allied democratic Africanism.

January 13, 2020

January 14, 1943 – World War II: The start of the Casablanca Conference

On January 14, 1943, the Western Allies, United States and Great Britain, met at the Casablanca Conference to discuss planning and strategy, particularly for the ongoing European theatre of World War II. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill led the delegations of their respective countries. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin declined to attend, stating that the ongoing Battle of Stalingrad required his presence in the Soviet Union. A delegation of the Free French forces also attended, led by Generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud.

The conference produced the Casablanca Declaration, which contained the stipulation that the Allies would accept only the “unconditional surrender” of Germany and Japan.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

“Big Three” Allied War Conferences

The United States, Britain, and Soviet Union, the so-called “Big Three” Powers, met in two major war-time conferences, at Tehran (November 28 – December 1, 1944) and Yalta (February 4-11, 1945), and in the immediate post-war period, at Potsdam (July 17-August 2, 1945). At the Tehran (Iran) Conference, the Big Three agreed to align military strategy. At the Yalta Conference (Yalta, Crimea, USSR) which was attended by U.S. President Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Churchill, and Soviet leader Stalin, the Allies, now in an overwhelming military position, agreed on the disposition of post-war Germany and Europe. By then, Stalin was negotiating in a superior position, as his Red Army was only 40 miles (65 km) from Berlin. Stalin agreed to join the war in the Asia-Pacific against Japan, and become a member of the United Nations (both requested by the United States), but in return persuaded Roosevelt and Churchill to allow the following: that the Soviet-Polish border be moved to the Curzon Line, that the Soviets gain the South Sakhalin and Kuril Islands from Japan, that the Port Arthur lease be restored to the Soviets, and that Mongolia (a Soviet satellite polity since 1924) been detached from China.

Of major contention at Yalta was the issue of Poland, as Roosevelt and Churchill wanted to return the Polish government-in-exile (in London) to power, while Stalin insisted on installing the pro-Soviet government already operating in recaptured Polish territories In fact, Poland formed only part of the

larger issue regarding the political future of Eastern Europe, where Stalin wanted to impose a Soviet sphere of influence to safeguard against another

invasion from the West, while Roosevelt and Churchill wanted democratic governments to be established there. Instead, the Big Three signed the “Declaration of Liberated Europe”, where they agreed that European nations must be allowed “to create democratic institutions of their own choice” and to “the earliest possible establishment through free elections [of] governments responsive to the will of the people”. Free elections were to be conducted in Poland as well, and the Soviet-sponsored provisional government, while remaining predominant, would be encouraged to include non-communists “on a broad

democratic basis”.

In the Potsdam agreement, the “Big Three”, now led by U.S. President Harry Truman (succeeding Roosevelt), British Prime Minister Clement Atlee (succeeding Churchill), and Stalin reaffirmed previous agreements with regards to dealing with post-war Germany and the territorial changes demanded

by Stalin. As well, Germany was required to pay war

reparations, and ethnic Germans were to be expelled from the former German lands and forced to move to within the new German borders. As Soviet domination of Poland was now a fait accompli, the

Western Allies acquiesce to the authority of the pro-Soviet Polish government in that country.