Daniel Orr's Blog, page 110

January 12, 2020

January 13, 1935 – Interwar period: A plebiscite in the Saar region shows that 90% of residents desire re-integration with Nazi Germany

On January 13, 1935, a plebiscite conducted in the Saar region showed that 90% of residents desired to be reintegrated with Nazi Germany. The League of Nations, which had been mandated by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles to administer the Saar for 15 years, returned the territory to Germany following the plebiscite.

(Taken from Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Post-World War I Pacifism

Because World War I had caused considerable toll on lives and brought enormous political, economic, and social troubles, a genuine desire for lasting peace prevailed in post-war Europe, and it was hoped that the last war would be “the war that ended all wars”. By the mid-1920s, most European countries, especially in the West, had completed reconstruction and were on the road to prosperity, and pursued a policy of openness and collective security. This pacifism led to the formation in January 1920 of the League of Nations (LN), an international organization which had membership of most of the countries existing at that time, including most major Western Powers (excluding the United States). The League had the following aims: to maintain world peace through collective security, encourage general disarmament, and mediate and arbitrate disputes between member states. In the pacifism of the 1920s, the League resolved a number of conflicts (and had some failures as well), and by mid-decade, the major powers sought the League as a forum to engage in diplomacy, arbitration, and disarmament.

In September 1926, Germany ended its diplomatic near-isolation with its admittance to the League of Nations. This came about with the signing in December 1926 of the Locarno Treaties (in Locarno, Switzerland), which settled the common borders of Germany, France, and Belgium. These countries pledged not to attack each other, with a guarantee made by Britain and Italy to come to the aid of a party that was attacked by the other. Future disputes were to be resolved through arbitration. The Locarno Treaties also dealt with Germany’s eastern frontier with Poland and Czechoslovakia,

and although their common borders were not fixed, the parties agreed that future disputes would be settled through arbitration. The Treaties were seen as a high point in international diplomacy, and ushered in a climate of peace in Western Europe for the rest of the 1920s. A popular optimism, called “the spirit of Locarno”, gave hope that all future disputes could be settled through peaceful means.

In June 1930, the last French troops withdrew from the Rhineland, ending the Allied occupation five years earlier than the original fifteen-year schedule. And in March 1935, the League of Nations returned the Saar region to Germany following a referendum where over 90% of Saar residents voted to be

reintegrated with Germany.

In August 1938, at the urging of the United States and France, the Kellogg-Briand Pact (officially titled “General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy”) was signed, which

encouraged all countries to renounce war and implement a pacifist foreign policy. Within a year, 62 countries signed the Pact, including Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Soviet Union, and China. In February 1929, the Soviet Union, a signatory and keen advocate of the Pact, initiated a similar agreement, called the Litvinov Protocol, with its Eastern European neighbors, which emphasized the immediate implementation of the Kellogg-Briand Pact among themselves. Pacifism in the interwar period also manifested in the collective efforts by the major powers to limit their weapons. In February 1922, the five naval powers: United States, Britain, France, Italy,

and Japan signed the Washington Naval Treaty, which restricted construction of the larger classes of warships. In April 1930, these countries signed the London Naval Treaty, which modified a number of

clauses in the Washington treaty but also regulated naval construction. A further attempt at naval regulation was made in March 1936, which was

signed only by the United States, Britain, and France, since by this time, the previous other signatories, Italy and Japan, were pursuing expansionist policies that required greater naval power.

An effort by the League of Nations and non-League member United States to achieve general disarmament in the international community led to the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva in 1932-1934, attended by sixty countries. The talks

bogged down from a number of issues, the most dominant relating to the disagreement between Germany and France, with the Germans insisting on being allowed weapons equality with the great powers (or that they disarm to the level of the Treaty of Versailles, i.e. to Germany’s current military strength), and the French resisting increased German power for fear of a resurgent Germany and a repeat of World War I, which had caused heavy French

losses. Germany, now led by Adolf Hitler (starting in January 1933), pulled out of the World Disarmament Conference, and in October 1933, withdrew from the League of Nations. The Geneva disarmament conference thus ended in failure.

January 11, 2020

January 12, 1958 – Ifni War: Saharan Liberation Army (SLA) revolutionaries attack El-Aaiún

On January 12, 1958, Saharan Liberation Army (SLA) revolutionaries attacked El-Aaiún, the capital of Spanish Sahara, but were repulsed. The 13th Banderas, a battalion of the Spanish Legion, pursued the retreating revolutionaries from the city but was caught in an ambush at Edchera. Some of the war’s most intense fighting followed, with the Spanish fending off repeated enemy attacks and more units on both sides joining the battle. Ultimately, the revolutionaries withdrew into the night after sustaining some 240 killed. Spanish losses also were heavy, officially placed at 37 dead and 50 wounded, but perhaps higher and even as many as the number of enemy casualties.

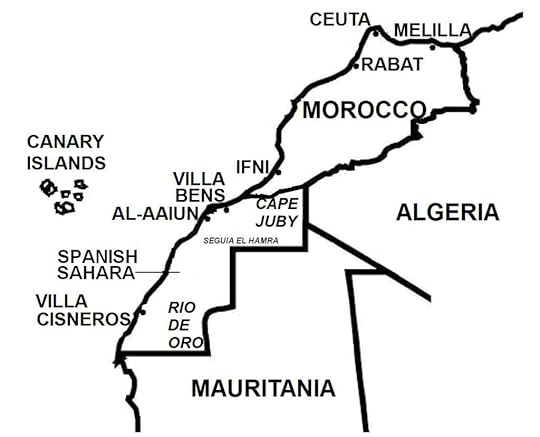

Spanish possessions in northwest Africa with adjacent countries.

(Taken from Ifni War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

In 1956, Morocco gained full independence after France and Spain ended their 44-year protectorate and returned political and territorial control to Mohammed V, the Moroccan Sultan. A period of rising tensions and violence had preceded Morocco’s independence which nearly broke out into open hostilities. While France fully ended its protectorate, Spain only did so with its northern zone, retaining control of the southern zone (consisting of Cape Juby

and the interior area called the Tarfaya Strip). At Morocco’s independence, apart from Morocco’s southern zone, Spain held a number of other territories in North Africa that the Spanish government viewed as integral parts of Spain (i.e. they were not colonies or protectorates); these included Ceuta and Melilla which Spain had controlled since the 1500s; Plazas de soberanía (English: Places of sovereignty), a motley of tiny islands and small areas bordering the Moroccan

Mediterranean coastline; and Spanish Sahara, a vast territory half the size of mainland Spain that the Spanish government had gained in 1884 as a result of

the Berlin Conference during the period known as the “Scramble for Africa”, where European powers wrangled for their “share” of Africa.

Spain declared having historical ties, by way of the Spanish Empire, to the Ifni region (traced incorrectly to Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña, a 15th century Spanish settlement which was actually located further south of Ifni), Villa Cisneros, founded in 1502 and located in Spanish Sahara, and the

Plazas de soberanía. In 1946, Spain merged the regions of Ifni, Cape Juby and Tarfaya Strip (southern zone of the Spanish protectorate), and Spanish Sahara into a single administrative unit called Spanish West Africa (Figure 13).

The Ifni region, which had at its capital the coastal city of Sidi Ifni, would become the focal point as well as lend its name to the coming war. After its defeat in the Spanish-Moroccan War in April 1860, Morocco ceded Ifni to Spain as a result of the Treaty of Tangiers.

Shortly after Morocco gained its independence, an ultra-nationalist movement, the Istiqlal Party led by Allal Al Fassi, advocated “Greater Morocco”, a political ideology that desired to integrate all

territories that had historical ties to the Moroccan Sultanate with the modern Moroccan state. As envisioned, Greater Morocco would consist of, apart from present-day Morocco itself, western Algeria, Mauritania, and northwest Mali – and all Spanish possessions in North Africa.

Officially, the Moroccan government did not subscribe to or espouse “Greater Morocco”, but did not suppress and even tacitly supported irredentist advocates of this ideology. As a result, the Moroccan Army did not actively participate in the coming war; instead, the Moroccan Army of Liberation (MAL), which was an assortment of several Moroccan militias that had organized and risen up against the French protectorate, carried out the war against the Spanish (and French).

Shortly after Morocco gained its independence, civil unrest broke out in Ifni, which included anti-Spanish protest demonstrations and violence targeting police and security forces. Infiltrators

belonging to MAL later began supporting these activities. The unrest prompted the central government in mainland Spain, led by General Francisco Franco, to send Spanish troops, including units of the Spanish Legion, to Spanish West Africa, whose security units until then consisted mostly of personnel recruited from the local population.

Meanwhile, MAL militias, comprising some 4,000–5,000 Moukhahidine (“freedom fighters”) and led by Ben Hamou, a Moroccan former mercenary officer of the French Foreign Legion, had deployed near southern Moroccan and Spanish Sahara, and soon were joined by Sahrawi Berber and Arab fighters; at their peak, some 30,000 revolutionaries would take part in the conflict.

January 10, 2020

January 11, 1923 – Interwar period: Troops from France and Belgium occupy the Ruhr region to force Germany to make World War I reparation payments

When Germany defaulted on war reparations in December 1922, French and Belgian forces

occupied the Ruhr region, Germany’s industrial heartland, to force payment. At the urging of the Weimar government, Ruhr authorities and residents launched passive resistance; shop owners refused to sell goods to the foreign troops, and coal miners and

railway employees did not work. Both Germany and France suffered financial losses as a result. Following United States intervention, in August 1924, the two sides agreed on the Dawes Plan , where German reparations payments were restructured, and the U.S.

and British government extended loans to help with Germany’s economic recovery. French troops then withdrew From the Ruhr region. Subsequently in August 1929, with the adoption of the Young Plan, Germany’s reparations obligations were reduced and payment was extended to a period of 58 years. As a result of these and other measures, including stronger fiscal control, introduction of a new currency, and easing bureaucratic hurdles, Germany’s economy recovered and expanded during the second half of the 1920s. Reparations were made, foreign investments entered the domestic market, and civil unrest declined.

(Taken from Weimar Republic – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Near the end of World War I, Germany was beset by severe internal tumult, as industrial workers, including those involved in war production, launched strike actions that were fomented by communist political and labor groups that long opposed Germany’s involvement in the war. Then in late

October-early November 1918 when German defeat in the war became imminent, German Navy sailors at the ports of Wilhelmshaven and Kiel mutinied, and refused to obey their commanders who had ordered them to prepare for one final decisive battle with the British Navy. Within a few days, the unrest had spread to many cities across Germany, sparking a full-blown communist-led revolt (the German Revolution) that peaked in January 1919, when democracy-leaning forces quelled the uprising. But in the chaos following German defeat in World War I, the monarchy under Kaiser (King) Wilhelm II ended, and was replaced by a social democratic state, the Weimar Republic (named after the city of Weimar, where the new state’s constitution was drafted).

The Weimar Republic, which governed Germany from 1919-1933, was permanently beset by fierce political opposition and also experienced two failed coup d’états. A full spectrum of opposition political parties, from the moderate to radical right-wing,

ultra-nationalist, and monarchist parties, to the moderate to extreme left-wing, socialist, and communist parties, wanted to put and end to the

Weimar Republic, either through elections or by paramilitary violence , and to be replaced by a political system suited to their respective ideologies. One radical political movement that emerged at this time was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, which came to be known in the West as the Nazi Party, and its members called Nazis, and led by

Adolf Hitler. The Nazis participated in the electoral process, but wanted to end the Weimar democratic system. Hitler denounced the Versailles treaty, advocated totalitarianism, held racial views that extolled Germans as the “master race” and disparaged

other races, such as Slavs and Jews, as “sub-humans”. The Nazis also were vehemently anti-communist

and advocated lebensraum (“living space”) expansionism in Eastern Europe and Russia.

A common theme among right-wing, ultra-nationalist, and ex-military circles was the idea that in World War I, Germany was not defeated on the battlefield. Rather, German defeat was caused by traitors, notably the workers who went on strike at a critical stage of the war and thus deprived soldiers at the front lines of their much-needed supplies. As well, communists and socialists were to blame, since they fomented civilian unrest that led to the revolution; Jews, since they dominated the

communist leadership; and the Weimar Republic since it signed the Versailles treaty. This concept, called the “stab in the back” theory, postulated that in 1918, Germany was on the brink of victory , but lost after being stabbed in the back by the “November criminals”, i.e. the communists, Jews, etc. After coming to power, the Nazis would appropriate the “stab in the back” theory to fit their political agenda in order to denounce the Versailles treaty, suppress opposition, and establish a dictatorship.

Germany, financially ravaged by the war, was hard pressed to meet its reparations obligations. The government printed enormous amounts of money to cover the deficit and also pay off its war debts, but this led to hyperinflation and astronomical prices of basic goods, sparking food riots and worsening the economy. Then when Germany defaulted on reparations in December 1922, French and Belgian forces occupied the Ruhr region, Germany’s industrial heartland, to force payment. At the urging of the Weimar government, Ruhr authorities and residents launched passive resistance; shop owners refused to sell goods to the foreign troops, and coal miners and railway employees did not work. Both Germany and France suffered financial losses as a result. Following United States intervention, in August 1924, the two sides agreed on the Dawes Plan , where German reparations payments were restructured, and the U.S.

and British government extended loans to help with Germany’s economic recovery. French troops then withdrew From the Ruhr region. Subsequently in August 1929, with the adoption of the Young Plan , Germany’s reparations obligations were reduced and payment was extended to a period of 58 years. As a result of these and other measures, including stronger fiscal control, introduction of a new currency, and easing bureaucratic hurdles, Germany’s economy recovered and expanded during the second half of the 1920s. Reparations were made, foreign investments entered the domestic market, and civil unrest declined.

The Versailles treaty was a heavy blow to the German national morale, and was seen as a humiliation to the Weimar state, which had been forced by the Allies to agree to it under threat of continuing the war. From the start, the Weimar government was determined to implement re-armament in violation of the Versailles treaty. Throughout its existence from 1919-1933, the Weimar Republic carried out small, clandestine, and subtle means to build its military forces, and was only restrained by the presence of Allied inspectors that regularly visited Germany to ensure compliance with the Versailles treaty. These methods included secretly reconstituting the German general staff, equipping and training the police for combat duties, and tolerating the presence of paramilitaries with an eye to later integrate them as reserve units in the regular army.

Also important to Germany’s secret rearmament was the Weimar government’s opening ties with the Soviet Union. Relations began in April 1922 with the

signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, which established diplomatic ties, and furthered in April 1926 with the Treaty of Berlin, where both sides agreed to remain neutral if the other was attacked by another country. In the aftermath of World War I, the Germans and Soviets saw the need to help each other, as they were outcasts in the international community: the Allies blamed Germany for starting the war, and also turned their backs on the Soviet Union for its communist ideology.

Military cooperation was an important component to German-Soviet relations. At the

invitation of the Soviet government, Weimar Germany built several military facilities in the

Soviet Union; e.g. an aircraft factory near Moscow,

an artillery facility near Rostov, a flying school near Lipetsk, a chemical weapons plant in Samara, a naval base in Murmansk, etc. In this way, Germany achieved some rearmament away from Allied detection, while the Soviet Union, yet in the process of industrialization from an agricultural economy, gained access to German technology and military theory.

January 9, 2020

January 10, 1966 – Indian-Pakistani War of 1965: The Tashkent Agreement is signed

On January 10, 1966, under mediation efforts by the Soviet Union, India and Pakistan signed the Tashkent Agreement (in Tashkent, Uzbek SSR; present-day Uzbekistan) that ended the Indian-Pakistani War of 1965. The agreement stipulated, among other things, that the armies of both sides return to their original positions along the ceasefire line before the start of the war. The two sides carried out the agreement’s stipulations. The 1965 war, therefore, achieved no territorial gains on either side. Furthermore, India’s overwhelming military superiority also fell short of achieving a total victory on the battlefield.

After the war, Pakistan and India began to distance themselves from the United States and other Western powers and looked toward other sources of military support. In particular, Pakistan

felt betrayed by the United States and drew closer to China and the Soviet Union. Similarly, India

established friendly relations with the Soviet Union

and soon began to purchase Russian-made weapons.

Armed clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces at Rann of Kutch in April 1965 were a precursor to a full-scale war in Kashmir five months later.

(Taken from Indian-Pakistani War of 1965 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

As a result of the Indian-Pakistani War of 1947 (previous article), the former Princely State of Kashmir was divided militarily under zones of occupation by the Indian Army and the Pakistani Army. Consequently, the governments of India

and Pakistan established local administrations in their respective zones of control, these areas ultimately becoming de facto territories of their respective

countries. However, Pakistan was determined to drive away the Indians from Kashmir and annex the whole region. As Pakistan and Kashmir had predominantly Muslim populations, the Pakistani government believed that Kashmiris detested being under Indian rule and would welcome and support

an invasion by Pakistan. Furthermore, Pakistan’s

government received reports that civilian protests in Kashmir indicated that Kashmiris were ready to revolt against the Indian regional government.

The Pakistani Army believed itself superior to its Indian counterpart. In early 1965, armed clashes broke out in disputed territory in the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat State, India (Map 3). Subsequently in 1968, Pakistan was awarded 350 square miles of the territory by the International Court of Justice. In 1965, India was still smarting from a defeat to China in the 1962 Sino-Indian War; as a result, Pakistan

believed that the Indian Army’s morale was low.

Furthermore, Pakistan had upgraded its Armed Forces with purchases of modern weapons from the United States, while India was yet in the midst of modernizing its military forces.

Indian-Pakistani War of 1965. As in the 1947-49 war, Kashmir was the battle ground for the two rival countries that wanted to annex the whole region.

In the summer of 1965, Pakistan made preparations for invading Indian-held Kashmir. To assist the operation, Pakistani commandos would penetrate Kashmir’s major urban areas, carry out sabotage operations against military installations and public infrastructures, and distribute firearms to civilians in order to incite a revolt. Pakistani military planners believed that Pakistan would have greater bargaining power with the presence of a civilian uprising, in case the war went to international arbitration.

January 8, 2020

January 9, 1995 – Cenepa War: Ecuador and Peru engage in border fighting, triggering war

By early January 1995, the strong Peruvian presence was being felt with an increase in military activities near the Ecuadorian forward outposts. Ecuadorian and Peruvian patrols encountered each other on January 9 and January 11, with the latter

encounter leading to an exchange of gunfire.

Then on January 21, Peruvian troops were landed by helicopter behind the Ecuadorian outposts in preparation for a Peruvian full offensive. The infiltration was discovered when an Ecuadorian patrol spotted some 20 Peruvian soldiers setting up a heliport. Ecuadorian Special Forces were called in;

after a two days’ trek through the jungle, the Ecuadorians located the Peruvian camp. In the ensuing firefight, the Ecuadorians dispersed the Peruvians. A number of Peruvians were killed, while the abandoned weapons and supplies in the camp were seized.

Both countries mobilized for war, massing their main forces along the border near the Pacific coast.

The war was confined to the Condor-Cenepa region, however, where the Peruvians launched many offensives aimed at destroying the Ecuadorian positions located at the eastern slope of the Condor.

On January 28, Peruvian ground forces, later backed by air cover, launched successive attempts on the Ecuadorian outposts. The ground attacks involved an uphill climb against well-entrenched positions. More

attacks were carried out the next day and into early February, with the Peruvians attempting to outflank the outposts but being met by strong resistance. On February 1, a Peruvian advance on Cuevas de los Tayos fell into a minefield, causing several

casualties.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, generating tensions and wars between the two countries.

(Taken from Cenepa War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background

The 1981 Paquisha War (previous article)

between Ecuador and Peru left unsettled the border dispute regarding sovereignty over the Condor Mountain range and the Cenepa River system located inside the Amazon rainforest. Peruvian forces achieved a tactical victory by destroying three

Ecuadorian forward outposts and re-established control over the whole eastern side of the Condor range, although the Ecuadorian government continued to claim ownership over the whole Condor-Cenepa region. In the years following the Paquisha War, the two sides strengthened their areas of control in the region, with the Ecuadorians occupying the peaks and western slope of the Condor range, and the Peruvians at the Condor’s eastern slope and Cenepa Valley. Because of the thick forest cover, Ecuadorian and Peruvian patrols often accidentally encountered each other, which at the

very worst, led to exchanges of gunfire, but generally ended without incident, as the two sides had agreed to abide by the Cartillas de Seguridad y Confianza (Guidelines for Security and Trust), which lay down the rules to prevent unnecessary bloodshed.

In November 1994, a Peruvian army patrol came upon an enemy outpost and was told by the Ecuadorian commander there that the location was

situated inside the Ecuadorian Army’s area of control. The Peruvian Army soon learned that the outpost, which the Ecuadorians named “Base Sur”, was located on the eastern slope of the Condor, and therefore in the area traditionally under Peruvian control. Thereafter, the Ecuadorian and Peruvian local commanders met a number of times to try and work out a resolution, but nothing came out of the meetings.

With tensions rising by December 1994, Ecuador and Peru began sending reinforcements and large quantities of weapons and military equipment to the disputed zone, a difficult and hazardous operation

(particularly for Peru’s Armed Forces because of the greater distance) which required air transports because of the absence of roads leading to the Condor region.

Apart from “Base Sur”, the Ecuadorians had set up a number of other outposts, including “Tiwintza” and “Cueva de los Tayos”, and the larger “Coangos”, near the top of the Condor Mountain. The camps’ defenses were strengthened by new minefields laid out at the approaches, and the installation of anti-aircraft batteries and multiple-rocket launchers; a further boost was provided by the arrival of Ecuadorian Special Forces and specialized teams equipped with hand-held surface-to-air missile launchers to be used against Peruvian planes.

By early January 1995, the strong Peruvian presence was being felt with an increase in military activities near the Ecuadorian forward outposts. Ecuadorian and Peruvian patrols encountered each other on January 9 and January 11, with the latter

encounter leading to an exchange of gunfire. Then on January 21, Peruvian troops were landed by helicopter behind the Ecuadorian outposts in preparation for a Peruvian full offensive. The infiltration was discovered when an Ecuadorian patrol spotted some 20 Peruvian soldiers setting up a heliport. Ecuadorian Special Forces were called in;

after a two days’ trek through the jungle, the Ecuadorians located the Peruvian camp. In the ensuing firefight, the Ecuadorians dispersed the Peruvians. A number of Peruvians were killed, while the abandoned weapons and supplies in the camp were seized.

January 7, 2020

January 8, 1987 – Iran-Iraq War: The start of the Battle of Basra

On January 8, 1987, Iran launched its long-anticipated offensive on Basra, which became the largest and bloodiest battle of the war. Some 600,000 Iranian soldiers took part and faced 400,000 Iraqi defenders. The seven-week offensive, which lasted until late February 1987, saw the Iranians launching successive assaults that succeeded in breaching four of the five Iraqi “dynamic defense” lines, including the modified barriers Fish Lake and Jasim River, and to come to within twelve kilometers of Basra, before being stopped. Iranian casualties were considerable– some 65,000 were killed; 20,000 Iraqi soldiers also perished.

The failure to capture Basra had a powerful demoralizing effect on Iran: in the aftermath, much fewer civilians volunteered to join the Revolutionary Guards and Basij, the general population became war-weary and felt the war was unwinnable, and even the Iranian leadership stopped plans for further major operations or “final offensives”.

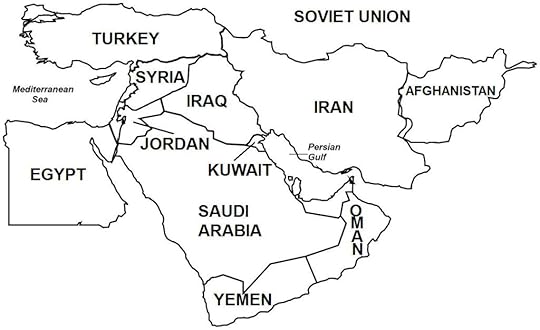

Iran, Iraq, and nearby countries.

(Excerpts taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

In 1937, the now independent monarchies of Iraq and Iran signed an agreement that stipulated that their common border on the Shatt al-Arab was located at the low water mark on the eastern (i.e. Iranian) side all across the river’s length, except in the cities of Khoramshahr and Abadan, where the border was located at the river’s mid-point. In 1958, the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown in a military coup. Iraq

then formed a republic and the new government made territorial claims to the western section of the Iranian border province of Khuzestan, which had a large population of ethnic Arabs.

In Iraq, Arabs comprise some 70% of the population, while in Iran, Persians make up perhaps 65% of the population (an estimate since Iran’s

population censuses do not indicate ethnicity).

Iran’s demographics also include many non-Persian ethnicities: Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchs, and

others, while Iraq’s significant minority group comprises the Kurds, who make up 20% of the

population. In both countries, ethnic minorities have pushed for greater political autonomy, generating unrest and a potential weakness in each government of one country that has been exploited by the other country.

The source of sectarian tension in Iran-Iraq relations stemmed from the Sunni-Shiite dichotomy.

Both countries had Islam as their primary religion, with Muslims constituting upwards of 95% of their total populations. In Iran, Shiites made up 90% of all Muslims (Sunnis at 9%) and held political power, while in Iraq, Shiites also held a majority (66% of all Muslims), but the minority Sunnis (33%) led by Saddam and his Baath Party held absolute power.

In the 1960s, Iran, which was still ruled by a

monarchy, embarked on a large military buildup, expanding the size and strength of its armed forces. Then in 1969, Iran ended its recognition of the 1937 border agreement with Iraq, declaring that the two countries’ border at the Shatt al-Arab was at the river’s mid-point. The presence of the now powerful Iranian Navy on the Shatt al-Arab deterred Iraq from

taking action, and tensions rose.

Also by the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurds were holding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the First Iraqi-Kurdish War, separate article); negotiations collapsed and fighting broke out in April 1974, with the Iraqi Kurds being supported militarily by Iran. In turn, Iraq incited Iran’s ethnic minorities to revolt, particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, Iranian Kurds, and Baluchs. Direct fighting between Iranian and Iraqi forces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iranians prevailing. Hostilities ended when the two countries signed the Algiers Accord in March 1975, where Iraq yielded to Iran’s demand that the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; in exchange, Iran ended its

support to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq was displeased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional military power, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues) during the second half of the 1970s. Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and even enjoyed a period of rapprochement. As a result of Iran’s assistance

in helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelled Ayatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iranian cleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.

However, Iranian-Iraqi relations turned for the worse towards the end of 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini was proclaimed as Iran’s absolute ruler. Each of the two rival countries resumed secessionist support for the various ethnic groups in the other

country. Iran’s transition to a full Islamic State was opposed by the various Iranian ethnic minorities, leading to revolts by Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchs. The

Iranian government easily crushed these uprisings, except in Kurdistan, where Iraqi military support allowed the Kurds to fend off Iranian government

forces until late 1981 before also being put down.

Ayatollah Khomeini, in line with his aim of spreading Islamic revolutions across the Middle East, called on Iraq’s Shiite majority to overthrow Saddam and his “un-Islamic” government, and establish an

Islamic State. In April 1980, a spate of violence attributed to the Islamic Dawa Party, an Iran- supported militant group, broke out in Iraq,

where many Baath Party officers were killed and other high-ranking government officials barely escaped assassination attempts. In response, the Iraqi government unleashed repressive measures against radical Shiites, including deporting thousands who were thought to be ethnic Persians, as well as executing Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, which drew widespread condemnation from several Muslim countries as the religious cleric was highly regarded in the wider Islamic community.

Throughout the summer of 1980, many border clashes broke out between forces of the two countries, increasing in intensity and frequency by

September of that year. As to the official start of the war, the two sides have different interpretations. The Iraqis cite September 4, 1980, when the Iranian Army carried out an artillery bombardment of Iraqi border towns, prompting Saddam two weeks later to unilaterally repeal the 1975 Algiers Accord and declare that the whole Shatt al-Arab lay within the territorial limits of Iraq.

September 22, 1980, however, is generally accepted as the start of the war, when Iraqi forces launched a full-scale air and ground offensive into Iran. Saddam believed that his forces were capable

of achieving a quick victory, his confidence borne by the following factors, all resulting from the Iranian Revolution. First, as previously mentioned, Iran

faced regional insurgencies from its ethnic minorities that opposed Iran’s adoption of Islamic fundamentalism. Second, Iran further was wracked by violence and unrest when secularist elements of the revolution (liberal democrats, communists, merchants and landowners, etc.) opposed the

Islamist hardliners’ rise to power. The Islamic state subsequently marginalized these groups and suppressed all forms of dissent. Third, the revolution

seriously weakened the powerful Iranian Armed Forces, as military elements, particularly high-ranking officers, who remained loyal to the Shah, was purged

and repressive measures were undertaken to curb the military. Fourth, Iran’s newly established Islamic

government, because it rejected both western democracy and communist ideology, became isolated internationally, even among Arab and Muslim countries.

January 6, 2020

On January 7, 1979 – Cambodian-Vietnamese War: Vietnamese forces capture Phnom Penh

On January 7, 1979, the Vietnamese Army captured the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh

in a blitzkrieg campaign and overthrew the Khmer Rouge regime. Pol Pot and his staff, together the bulk of the Khmer Rouge Army, made a strategic withdrawal to the jungle mountains of western Cambodia near the Thai border, where they set up a resistance government.

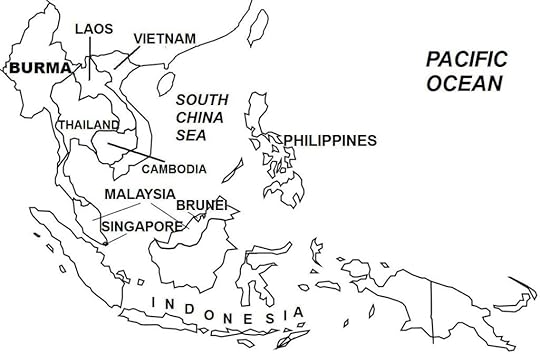

Southeast Asia during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War.

(Taken from Cambodian-Vietnamese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background

The revolutionary movements that eventually prevailed in Vietnam and Cambodia (as well as in Laos) trace their origin to 1930 when the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) was formed. VCP soon reorganized itself into the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) to include membership to Cambodian and

Laotian communists into the Vietnamese-dominated movement. The great majority of ICP Khmers were not indigenous to Cambodia; rather they consisted mostly of ethnic Khmers who were native to southern Vietnam, and ethnic Vietnamese living in Cambodia.

In 1951, the ICP split itself into three nationalist

organizations for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos respectively, i.e. Workers Party of Vietnam, Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (KPRP), and Neo Lao Issara. In December 1946, the Viet Minh (or League for the Independence of Vietnam), a Vietnamese nationalist group that was formed in World War II to fight the Japanese, began an independence war against French rule (First Indochina War, separate article). The Viet Minh prevailed in July 1954. The 1954 Geneva Accords, which ended the war, divided Vietnam into two military zones, which became

socialist North Vietnam and West-aligned South Vietnam. War soon broke out between the two Vietnams, with North Vietnam supported by China

and the Soviet Union; and South Vietnam supported by the United States. This Cold War conflict, called the Vietnam War (separate article) and which included direct American military involvement in 1965-1970, ended in April 1975 with a North Vietnamese victory. As a result, the two Vietnams

were reunified, in July 1976.

Meanwhile in Cambodia, the local revolutionary struggle ended with the 1954 Geneva Accords, which gave the country, led by King Sihanouk, full independence from France. The Accords also ended both French rule and French Indochina, and independence also was granted to Laos and Vietnam. Following the First Indochina War, most of the Khmer communists moved into exile in North Vietnam, while those who remained in Cambodia formed the Pracheachon Party, which participated in the 1955 and 1958 elections. However, government repression forced Pracheachon Party members to go into hiding in the early 1960s.

By the late 1950s, the Cambodian communist movement experienced a resurgence that was spurred by a new generation of young, Paris-education communists who had returned to the country. In September 1960, ICP veteran communists and the new batch of communists met and elected a Central Committee, and renamed

the KPRP (Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Party) as the Worker’s Party of Kampuchea (WPK).

In February 1963, following another government suppression that led to the arrest of communist leaders, the WPK soon came under the control of the younger communists, led by Saloth Sar (later known as Pol Pot), who sidelined the veteran communists whom they viewed as pro-Vietnamese. In September 1966, the WPK was renamed the Kampuchean Communist Party (KCP).

The KCP and its members, as well its military wing, were called “Khmer Rouge” by the Sihanouk government. In January 1968, the Khmer Rouge launched a revolutionary war against the Sihanouk regime, and after Sihanouk was overthrown in March 1970, against the new Cambodian government. In April 1975, the Khmer Rouge triumphed and took over political power in Cambodia, which it renamed Democratic Kampuchea.

During its revolutionary struggle, the Khmer Rouge obtained support from North Vietnam,

particularly through the North Vietnamese Army’s capturing large sections of eastern Cambodia,

which it later turned over to its Khmer Rouge allies. But the Khmer Rouge held strong anti-Vietnamese sentiment, and deemed its alliance with North Vietnam only as a temporary expedient to combat a common enemy – the United States in particular, Western capitalism in general. The Cambodian communists’ hostility toward the Vietnamese resulted from the historical domination by Vietnam of Cambodia during the pre-colonial period, and the perception that modern-day Vietnam wanted to

dominate the whole Indochina region.

Soon after coming to power, the Khmer Rouge launched one of history’s most astounding social revolutions, forcibly emptying cities, towns, and all urban areas, and sending the entire Cambodian population to the countryside to become peasant workers in agrarian communes under a feudal-type

forced labor system. All lands and properties were nationalized, banks, schools, hospitals, and most industries, were shut down. Money was

abolished. Government officials and military officers of the previous regime, teachers, doctors, academics,

businessmen, professionals, and all persons who had associated with the Western “imperialists”, or were deemed “capitalist” or “counter-revolutionary” were

jailed, tortured, and executed. Some 1½ – 2½ million people, or 25% of the population, died under the Khmer Rouge regime (Cambodian Genocide, previous article).

In foreign relations, the Khmer Rouge government isolated itself from the international community, expelling all Western nationals, banning the entry of nearly all foreign media, and closing down all foreign embassies. It did, however, later allow a number of foreign diplomatic missions (from communist countries) to reopen in Phnom Penh. As well, it held a seat in the United Nations (UN).

The Khmer Rouge was fiercely nationalistic and xenophobic, and repressed ethnic minorities, including Chams, Chinese, Laotians, Thais, and

especially the Vietnamese. Within a few months, it had expelled the remaining 200,000 ethnic Vietnamese from the country, adding to the 300,000 Vietnamese who had been deported by the previous

Cambodian regime.

January 5, 2020

January 6, 1921 – Turkish War of Independence: Greek forces attack the town of Eskişehir

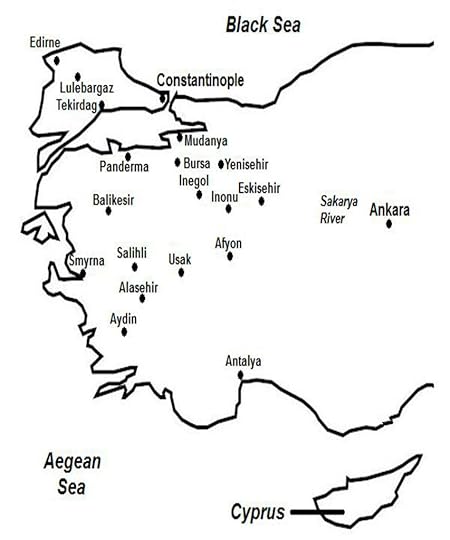

On January 6, 1921, the Greek Army attacked in the direction of the strategic town of Eskişehir,

but was repulsed at the First Battle of Inonu. The battle was downplayed by the Greeks as a minor setback, but it considerably raised the morale of the Turks, who for the first time, had turned back the enemy. Because of this development, the Allied Powers (Britain, France, and Italy) met with

representatives of the Ottoman government and Turkish nationalists in London (known as the Conference of London) in February-March 1921 in order to negotiate changes to the Treaty of Sevres, which by this time was impossible to implement. However, the Turkish nationalists were unyielding in their position that Turkey’s territorial integrity was

non-negotiable and that the Allies must withdraw. As a result, the conference ended without reaching a settlement.

In early March 1921, with the arrival of reinforcements, the Greeks attacked again, but were defeated at the Second Battle of Inonu, and forced to return to Bursa. The Greeks’ southern advance captured Afyon, but a Turkish attempt to cut the railway line between Afyon and Usak forced the

Greeks to meet and contain the threat, and then withdraw to Usak.

The Western Front in the Turkish War of Independence.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Western Front

Greece had entered World War I on the side of the Allies because of Britain’s promise to reward Greece

with a large territorial concession of Ottoman Anatolia at the end of the war. Greece particularly was interested in the Ottoman territories that contained a large ethnic Greek population, notably Smyrna, which had a sizable to perhaps even a majority Greek population and was the Greeks’

cultural and economic center in Anatolia, and Eastern Thrace, as well as the islands of Imbros and Tenedos on the Aegean Sea.

As the Ottoman government had repressed ethnic Greeks in Anatolia during the war, the Allied Powers invoked a stipulation in the Armistice of Mudros to allow Greek forces to occupy Smyrna.

The presumption was that despite the Ottoman capitulation, ethnic Greeks continued to be threatened by the Ottomans with massacres and dispossession of properties, which were reported to have taken place extensively during the war.

A post-war complication arose since Britain, France, and Italy previously had signed a treaty (Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne of April 1917), whereby Smyrna and western Anatolia were to be allocated to the Italians. At the Paris Peace Conference held after the war, both the Italian and Greek delegations lobbied hard for Smyrna; in the end, the other Allied powers (led by Britain) voted in favor of Greece.

Then in the Treaty of Sevres of 1920, Italy was granted southern Anatolia centered in Antalya, while Greece was given western Anatolia around Smyrna (as well as most of Eastern Thrace). The Italians, however, felt that they had received the short end of the deal without Smyrna, a resentment that would influence the outcome of the western front.

On May 16, 1919, with Allied approval, 20,000 Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna, where they were greeted as liberators by a large crowd of ethnic Greeks. A commotion broke out when a Turkish gunman fired at the Greek Army, killing one soldier.

The Greek Army then opened fire, triggering a spate of violence across the city. When order later was restored, some 300 Turkish and 100 Greek civilians had been killed; many incidents of lootings, beatings, rapes, and other crimes also took place.

War

Of the Allied occupations, the Greek entry in Smyrna greatly provoked the Turks. As a result, many Turkish guerilla groups formed, while it was at this time that Kemal began

organizing his revolutionary nationalist government. The western front (more commonly known as the

Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922) began in earnest in mid-1920 (eleven months after the initial Greek landing) as a result of Britain’s attempt to implement the newly released Treaty of Sevres. The treaty was presented to and signed by the Ottoman government, but was not ratified; Ottoman authorities insisted that the treaty must be concurred to also by Kemal, who clearly would not agree to it. In fact, Kemal’s nationalist forces, by this time, were fighting the

French in the southern front and were preparing a major offensive against the Armenians in the eastern front.

Furthermore, by the time of the Treaty of Sevres, divisions caused by competing interests had developed among the Allies: France resented Britain’s

domineering position; Italy wanted to curb British and French domination and Greek expansionism; and the

French-Armenian alliance was faltering.

January 5, 1992 – Bosnian War: Bosnian Serbs secede from Bosnia-Herzegovina

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s

northern regions. On January 5, 1992, Bosnian Serbs seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own country. Bosnian Croats, who also

comprised a sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented into three republics, formed along ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslav constituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretly agreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majority population of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbians and Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armed conflict between them. By this time, heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to open hostilities.

Mediators from Britain and Portugal made a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincing Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political power in a decentralized government. Just ten days later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejected the agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

Yugoslavia comprised six republics, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, and Macedonia, and two autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

(Taken from Bosnian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

Background

Bosnia-Herzegovina has three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), comprising 44% of the

population, Bosnian Serbs, with 32%, and Bosnian Croats, with 17%. Slovenia and Croatia declared their independences in June 1991. On October 15, 1991, the Bosnian parliament declared the independence of

Bosnia-Herzegovina, with Bosnian Serb delegates boycotting the session in protest. Then acting on a request from both the Bosnian parliament and the Bosnian Serb leadership, a European Economic Community arbitration commission gave its opinion, on January 11, 1992, that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence cannot be recognized, since no

referendum on independence had taken place.

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s

northern regions. On January 5, 1992, Bosnian Serbs seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own country. Bosnian Croats, who also

comprised a sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented into three republics, formed along ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslav constituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretly agreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majority population of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbians and Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armed conflict between them. By this time, heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to open

hostilities.

Mediators from Britain and Portugal made a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincing Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political power in a decentralized government. Just ten days later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejected the agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

War

At any rate, by March 1992, fighting had already broken out when Bosnian Serb forces attacked Bosniak villages in eastern Bosnia. Of the three sides, Bosnian Serbs were the most powerful early in the war, as they were backed by the Yugoslav Army. At their peak, Bosnian Serbs had 150,000 soldiers, 700 tanks, 700 armored personnel carriers, 3,000 artillery pieces, and several aircraft. Many Serbian militias also joined the Bosnian Serb regular forces.

Bosnian Croats, with the support of Croatia, had

150,000 soldiers and 300 tanks. Bosniaks were at a great disadvantage, however, as they were unprepared for war. Although much of Yugoslavia’s war arsenal was stockpiled in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the weapons were held by the Yugoslav Army (which became the Bosnian Serbs’ main fighting force in the early stages of the war). A United Nations (UN) arms embargo on Yugoslavia was devastating to Bosniaks, as they were prohibited from purchasing weapons

from foreign sources.

In March and April 1992, the Yugoslav Army and Bosnian Serb forces launched large-scale operations in eastern and northwest Bosnia-Herzegovina. These offensives were so powerful that large sections of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat territories were captured and came under Bosnian Serb control. By the end of 1992, Bosnian Serbs controlled 70% of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Then under a UN-imposed resolution, the Yugoslav Army was ordered to leave Bosnia-Herzegovina. However, the Yugoslav Army’s withdrawal did not affect seriously the Bosnian Serbs’ military capability, as a great majority of the Yugoslav

soldiers in Bosnia-Herzegovina were ethnic Serbs. These soldiers simply joined the ranks of the Bosnian Serb forces and continued fighting, using the same

weapons and ammunitions left over by the departing Yugoslav Army.

In mid-1992, a UN force arrived in Bosnia-Herzegovina that was tasked to protect civilians and refugees and to provide humanitarian aid. Fighting between Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats occurred in Herzegovina (the southern regions) and central Bosnia, mostly in areas where Bosnian Muslims formed a civilian majority. Bosnian Croat forces held the initiative, conducting offensives in Novi Travnik and Prozor. Intense artillery shelling reduced Gornji Vakuf to rubble; surrounding Bosniak villages also were taken, resulting in many civilian casualties.

In May 1992, the Lasva Valley came under attack

from the Bosnian Croat forces who, for 11 months, subjected the region to intense artillery shelling and ground attacks that claimed the lives of 2,000 mostly civilian casualties. The city of Mostar, divided into

Muslim and Croat sectors, was the scene of bitter fighting, heavy artillery bombardment, and widespread destruction that resulted in thousands of civilian deaths. Numerous atrocities were committed in Mostar.

January 3, 2020

January 4, 1918 – Finland’s independence is recognized by Soviet Russia, Sweden, Germany, and France

On January 4, 1918, Finland’s independence was recognized by Soviet Russia (officially: Russian

Soviet Federative Socialist Republic), Sweden, Germany, and France, the first countries to do so. Finland had declared independence from Russia

on December 6, 1919.

Finland in Europe.

(Taken from Finnish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background

With no fighting taking placing place on its soil, the Grand Duchy of Finland largely was spared the ravages brought about during the 1914-1917 period of World War I. By 1917, because of the February Revolution and imminent Russian defeat in World War I, Finland experienced deterioration in its security climate, foremost because the Russian Army in Finland had broken down in discipline and morale, and verged on mutiny, with soldiers refusing to obey and even attacking their superiors. Police forces also largely had disintegrated.

In July 1917, the Social Democratic Party, which held a majority in the Finnish Parliament, proposed a bill to add more power to Parliament, increase Finland’s autonomy, and restrict Russia’s authority on Finland to defense and foreign affairs. The proposal resulted from the end of the Russian monarchy, and thus the Russian tsar’s personal union with the Grand Duchy of Finland, as well as the Russian provisional government’s acceding to the restoration of Finland’s

autonomy. The bill, which came into law as the “Power Act”, was passed with the support of the Social Democratic Party, Agrarian League, and others, but was opposed by conservatives and non-socialist

parties. The Russian government, however, made a turn around and rejected Finland’s “Power Act”, intervened militarily and dissolved the Finnish Parliament, and called for new legislative elections.

In parliamentary elections held in October 1917 which were bitterly contested and where violence broke out between socialist and non-socialist supporters, the Social Democratic Party lost its majority in Parliament (although it still held more seats among individual parties); parliament came under the control of the conservative and non-socialist bloc. These events were bitterly felt by the

political left, which began to believe that its plans for labor and civil reforms could not be achieved through democratic means. These feelings further were aggravated when the conservatives formed a government under Pehr Evind Svinhufvud that

consisted solely of conservatives (whereas previous governments were all-inclusive and had members from socialist and non-socialist parties).

On November 1, 1917, the Social Democrats launched the “We Demand” initiative, which called for the implementation of a wide range of reforms. But when parliament rejected these demands, on November 14, the labor movement carried out strike actions that disrupted the industrial sector and within two days had brought Finland to an economic standstill. The strike threatened to escalate into a full-blown uprising, as desired by radical labor

elements, but by November 20, it came to an end by the efforts of the Social Democrats, who as yet spurned violent methods to achieve their aims.

Meanwhile in Russia, the second revolution of 1917 occurred on November 7 (October 25 in the Julian calendar, thus the popular name “October Revolution” denoting this event), where the communist Bolshevik Party came to power by overthrowing the Russian Provisional Government in Petrograd, Russia’s capital. The two 1917 revolutions, as well as ongoing events in World War I, catalyzed ethnic minorities across the Russian Empire, resulting in the various regional nationalist movements pushing forward their objectives of seceding from Russia and forming new nation-states. In the western and northern regions of the empire, the territories of Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland moved toward self-determination.

Vladimir Lenin and his Bolshevik Party, on coming to power through the October Revolution, issued the “Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia” (on November 15, 1917), which granted all non-Russian peoples of the former Russian Empire the right to secede from Russia and establish their own separate states. Eventually, the Bolsheviks would renege on this edict and suppress secession from the Russian state (now known as Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, or RSFSR). The Bolsheviks, whose revolution had succeeded partly on their promises to a war-weary Russian citizenry to withdraw from World War I, declared its pacifist intentions to the Central Powers. A ceasefire agreement was signed on December 15, 1917 and peace talks began a few days later in Brest-Litovsk (present-day Brest, in Belarus).

Meanwhile in Finland, the emergence of the Bolshevik regime in Russia (as well as the impending tumult that soon would be generated by counter-revolutionary, i.e. anti-Bolshevik, White forces) led to the Finnish parliament working for full separation from Russia, not least because of the incompatibility between the socialist Russian and democratic Finnish political ideologies. On December 6, 1917, Svinhufvud’s government declared the independence of Finland. The Finnish Social Democrats opposed this declaration and instead carried out its own proclamation of independence which it then presented to the Bolshevik Russian government for approval. Similarly, the Svinhufvud government sought Soviet Russia’s recognition of Finland’s

independence.

Lenin, facing immense political and military pressures internally and externally, was in no position to take a hard-line stance, and was prepared to give up western territories of the former Russian Empire in

order to consolidate power at the core of the Russian heartland. Furthermore, he had unsuccessfully pressed the Finnish Social Democrats to launch a “proletariat revolution”, knowing that a pro-Russian socialist Finland would be geopolitically and strategically beneficial, even necessary, for the

defense of Petrograd, Russia’s capital, and the whole

northwest region. However, a great majority of the Finnish socialists only held moderate views, and an armed revolution called for by radical socialists on November 16, 1917 was cancelled due to lack of popular support. Thus, on December 31, 1917, Lenin recognized Finland’s independence.

Russia’s recognition of sovereign Finland

also gave legitimacy to Svinhufvud’s conservative government which on January 9, 1918 authorized the various conservative-organized armed groups around the country to carry out police and security duties. As in the 1905 Russian Revolution, the breakdown of government security infrastructures led to the rise all across Finland of numerous security groups, innocuously called “fire brigades”, organized by

various sectors, e.g. politicians, industrialists, landowners, labor and farmers’ associations, etc. These security groups soon became polarized and aligned along two ideological/political camps: non-socialists (conservatives, parliamentarians, liberals, etc.) and socialists. Security groups associated with the socialists/labor movement were known as “Red Guards” and “Workers’ Security Guards”, while those of non-socialists were called “Civil Guards” or

“White Guards”. In 1917, as in 1906, these groups soon turned into armed militias and engaged each other in gunfights and terror actions, e.g. assassinations, against their political and ideological enemies. The growing militarization of these groups became evident during the general labor strike of November 1917 when the Red Guards executed many conservative supporters, and street battles broke out between rival militias. The strike brought about an irreparable split between conservatives and socialists, and each side now was determined to

subdue the other, using force if necessary. By December 1917, Finland appeared ready to break out into open warfare, not unlike the revolutionary

“class struggle” that had taken place recently in Russia during the October Revolution.

By early January 1918, conservatives and revolutionary socialists were radicalized into opposite, hostile, and increasingly armed camps. On January 12, 1918, the Finnish government declared its intention to enforce the rule of law; two weeks later (on January 25), it appointed General Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, a Finnish former officer of the defunct Russian Imperial Army, as commander-in-chief of all military forces and to organize the country’s armed forces, initially using the White Guards to carry out security functions. As a result of mandatory conscription of all adult males, General Mannerheim organized a fledging army and was helped in large part by the arrival of the first batch of Finnish Jäger soldiers (of the elite Prussian 27th Jäger Battalion, a German Army-trained unit made up of

Finnish volunteers that had fought for Germany in the Eastern Front), as well as Swedish Army officers (Sweden became involved because of its determination to stop Bolshevik revolutionary ideas from entering its territory).

During the last week of January 1918, events rapidly unfolded that led to the outbreak of war. On January 25, 1918, the Finnish government issued orders to White forces to end the activities of hostile armed groups. Two days earlier and continuing thereafter, Finnish forces, with the collaboration of anti-Bolshevik Russian Army officers, disarmed Russian garrisons in Ostrobothnia and other locations, and seized large quantities of weapons and ammunitions to arm and supply the as yet poorly

equipped Finnish Army. On January 26, 1918, the Red Guards declared the start of the revolution by lighting the tower of the Helsinki Worker’s House. On January 26, the Red Guards, after winning over support of the Social Democratic Party, mobilized for war; four hours later, on January 28, the Finnish government announced its own mobilization. Shortly thereafter, all socialist and workers’ militias organized into a single unified Red Guards. The Red Guards’ uprising in Helsinki seized control of the capital, forcing the conservative government, first to go

into hiding in the city and then transferring the seat of government to Vaasa on the country’s west coast (Figure 25).

On January 29, 1918, the Social Democrats and Red Guards declared the Finnish Socialist Workers’ Republic, with Helsinki as its capital, and headed by a

government called the Finnish People’s Delegation. The Finnish socialist government did not emulate the Russian Bolsheviks’ soviet (council) model and instead envisioned a universal-suffrage, democratic, multi-party elective parliamentary system with constitutional guarantees of civil rights, including the freedom of speech, assembly, press, and religion. However, all lands would be nationalized and private ownership would be subject to state laws.

Thus by late January 1918, Finland had two rival

governments, each claiming sovereignty over the country, and differentiated as the conservative, anti-socialist “White Finland” with its forces consisting of

the Finnish Army, White Guards, and their allies; and socialist “Red Finland, with its forces consisting of the Red Guards and their allies.