April 16, 1945 – World War II: The start of the Battle of Berlin, with one million Soviet troops attacking the heavily fortified Seelow Heights

On April 16, 1945, the Soviet Red Army launched its offensive, opening a preliminary massive artillery bombardment that landed on the mostly undefended banks of the Oder River. Soviet ground forces then advanced, with much of the heaviest fighting centered on the strongly fortified Seelow Heights, where Marshal Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, comprising 1 million troops and 20,000 tanks advanced head on to German 9th Army’s 100,000 troops and 1,200 tanks. By the fourth day, the Soviets had broken through, sustaining heavy losses of 30,000 killed and 800 tanks destroyed, against 12,000 German casualties.

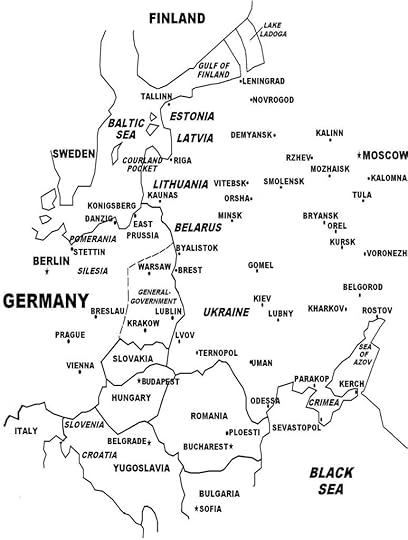

The series of massive Soviet Counter-Offensives recaptured lost Soviet territory and then swept through Eastern and Central Europe into Germany.

The series of massive Soviet Counter-Offensives recaptured lost Soviet territory and then swept through Eastern and Central Europe into Germany.(Taken from Soviet Counter-Attack and Defeat of Germany – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

Berlin and Defeat of

Germany The Soviet offensive into Germany centered on Stalin’s two main

objectives: that the Red Army was to rapidly push far to the west as possible

to beat the Western Allies into capturing as much German territory as possible;

and that Berlin was to fall into Soviet hands, first, to deal with Hitler and

second, to gain possession of Germany’s nuclear research program. For the campaign, Stalin tasked three Soviet

Army Groups, together with the Red Army’s best commanders: 1st Belorussian

Front led by Marshal Georgy Zhukov; 2nd Belorussian Front led by Marshal

Konstantin Rokossovsky, to the north of Zhukov’s forces; and 1st Ukrainian

Front led by Marshal Ivan Konev, to the south of Zhukov’s forces. The combined forces were massive: 2.5 million

troops, including 200,000 Polish soldiers, 6,200 tanks, 42,000 artillery

pieces, and 7,500 planes.

For the defense of outer Berlin, the Wehrmacht mustered 800,000

troops, 1,500 armored vehicles, 9,300 artillery pieces, and 2,200 planes. The main defensive lines for the eastern

approaches to the city were located 56 miles (90 km) at Seelow Heights

and manned by German 9th Army. The

German military had taken advantage of the delayed Soviet offensive on Berlin to construct

these defenses. The Germans positioned

these lines 10 miles (17 km) west of the Oder River,

which would prove significant in the coming battle.

On April 16, 1945, the Red Army launched its offensive,

opening a preliminary massive artillery bombardment that landed on the mostly

undefended banks of the Oder

River. Soviet ground forces then advanced, with much

of the heaviest fighting centered on the strongly fortified Seelow Heights,

where Marshal Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, comprising 1 million troops and

20,000 tanks advanced head on to German 9th Army’s 100,000 troops and 1,200

tanks. By the fourth day, the Soviets

had broken through, sustaining heavy losses of 30,000 killed and 800 tanks

destroyed, against 12,000 German casualties.

To the south, Marshal Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front also broke

through, with lead elements advancing through open country to the west which

would eventually meet up with U.S. Army troops at the Elbe

River, and armored units advancing

rapidly toward Berlin. A race now developed between Marshals Zhukov

and Konev on who would capture Berlin

first.

Marshall Konev’s offensive trapped German 9th Army in a

large pocket west of Frankfurt. In a pincers movement, forces of Zhukov and

Konev advanced through the periphery of Berlin,

closing shut to the rear and encircling the city on April 24. Meanwhile, Marshall Rokossovsky’s 2nd

Ukrainian Front positioned north of Berlin, thrusting on April 20, broke

through German 3rd Panzer Army at Stettin, and advanced rapidly west, soon

meeting up with elements of the British Army at Stralsund in the Baltic coast.

On April 24, the battle for the inner city of Berlin began,

with some 1.5 million Soviet troops facing Berlin Defence Area units, a motley

of Wehrmacht units (45,000 troops), Berlin police, Hitler Youth, and the Nazi

Party’s Home Guard “Volkssturm” militia (40,000 armed civilians). Hitler, who directed the battle from his

underground bunker in Berlin, and who yet believed that the war was not lost,

ordered German 12th Army (deployed to confront the Western Allies) to head for

Berlin and link up with the trapped German 9th Army, and for the combined units

to encircle and destroy the two Soviet Army Groups in Berlin, which was an

utterly impossible task. German 12th

Army ran into a Soviet stonewall and was forced back, but battered elements of

German 9th Army (some 30,000 of the original 200,000 troops) maneuvered through

gaps in the Soviet cordon, and both formations retreated to the west and

surrendered to the Western Allies.

By late April 1945, for the Germans, the battle of Berlin and the wider war in Europe

and World War II were lost. On April 30,

Hitler took his own life in his underground bunker below the Reich Chancellery

in Berlin

just as Soviet troops were closing in.

On May 2, Berlin

fell as the city’s garrison surrendered to the Red Army.

Admiral Karl Doenitz, head of the German Navy, took over as

head of state and president of Germany, succeeding as such as mandated in

Hitler’s last will and testament. With

the Third Reich falling apart and the Wehrmacht defeated, Admiral Doenitz was

determined to end the war – as quickly as possible with the Western Allied

Powers, but to delay as much with the Soviet Union. The idea was to allow the many scattered

German units in the east and facing the Red Army to turn around and make a

fighting retreat to surrender to the Western Allies. Also, troops and civilians along the Baltic

coastal areas would be allowed time to evacuate to Germany. Immediately, a spate of partial capitulations

occurred in the west: on May 2 (signed on April 29), German forces (1 million

troops) in Italy and western Austria surrendered to British forces; on May 4,

German forces (1 million troops) in northwest Germany, the Netherlands, and

Denmark surrendered to British and Canadian forces; on May 5, German forces in

Bavaria and southwest Germany surrendered to U.S. forces. At the same time, fighting continued in the

east, although encircled German forces in Breslau

surrendered on May 6, ending a nearly three-month siege.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, then

saw through the German ploy, and being greatly concerned that the Soviets might

suspect that Germany wanted to make a separate peace with the Western Allies

(which in fact was what Admiral Doenitz intended), ordered that no partial

capitulations would be accepted, and Germany must unconditionally surrender all

its forces.

On May 7, 1945, on Admiral Doenitz’s order, General Alfred

Jodl, the German Armed Forces Chief of Operations, signed the instrument of

unconditional surrender of all German forces at Allied headquarters in Reims, France. A few hours later, Stalin expressed his

disapproval of certain aspects of the surrender document, as well as its

location. At his insistence, another

signing of Germany’s

unconditional surrender was held in Berlin

by General Wilhelm Keitel, head of German Armed Forces, with particular

attention placed on the Soviet contribution, and in front of General Zhukov,

whose forces had captured the German capital.

Shortly thereafter, most of the remaining German units

surrendered to nearby Allied commands, including German Army Group Courland in

the “Courland Pocket”, Second Army Heiligenbeil and Danzig beachheads, German

units on the Hel Peninsula in the Vistula delta, Greek islands of Crete,

Rhodes, and the Dodecanese, on Alderney Island in the English Channel, and in

Atlantic France at Saint-Nazaire, La Rochelle, and Lorient.

Some units defied the surrender order for a few more days,

including German Army

Group Center

(with some 600,000 troops) in Bohemia and Moravia, which since May 5 had been trying to put down an

uprising by the Czech resistance in Prague. But with the Red Army (comprising 1.7 million

troops) soon joining the battle, the Germans made a futile attempt to fight its

way to the west to surrender to U.S. forces.

However, German Army Group E in Croatia,

along with the collaborationist Chetnik militia, succeeded in breaking through

Tito’s Yugoslav Partisan lines to reach Italy, where they surrendered to

the British command.