Aidan Moher's Blog, page 18

August 5, 2014

Attending LonCon 3? Come on out to Blogger Voltron!

Attending LonCon 3? Well, have I got a deal for you! It’s called Blogger Voltron, and it’s going to rock.!

You’ll get to meet me, and Justin Landon of Staffer’s Book Review, and Ana Grilo & Thea James of The Book Smugglers, Jared Shurin and Anne Perry, too! In fact, pretty much every cool blogger will be there, and, as everyone knows, we run the show, so it’s best to keep us feeling good about ourselves and our parties. It might be your only opportunity to meet some of us before our heads expand to the size of interstellar asteroids after the Hugo ceremonies the following evening.

Blogger Voltron

When: 9:00pm (21:00), Saturday, August 16th

Where: Fan Village (Excel Centre)

And, if you attend (yes, you specifically), Justin has promised that each guest will have the opportunity to each sushi off of his flexed biceps. You wouldn’t want to deprive the science fiction and fantasy fan community of that pleasure, would you?

If you come to Blogger Voltron, be sure to come on over and say, “hi!” One of the things I’m most excited about is being able to meet and socialize with all of my awesome readers. This will be a great opportunity to share a drink, some laughs, and hang out with some of the most passionate folk in fandom. Hope to see you there!

The post Attending LonCon 3? Come on out to Blogger Voltron! appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 31, 2014

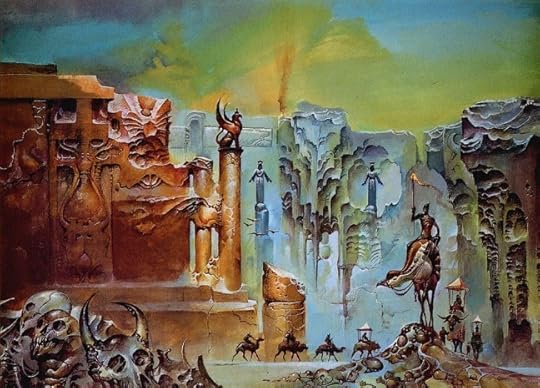

Visit the fascinating fantasy worlds of Li Shuxing

Each illustration is a portal into another world, a still life of a fantasy universe.

Sometimes an image is so arresting, you can’t help but stop and stare. I first discovered the artwork of Li Shuxing, a Chinese videogame concept artist and illustrator from Shanghai, through the image above. It’s enchanting, a whole fantasy world, with great depth and sorrow, perseverance and human courage, encapsulated in one image. The best paintings tell a story, and this image, replacing the long-in-the-tooth Smaug-style dragon with a traditional Chinese serpent, has a thousand stories to tell.

Then, I started digging around the Internet for more of Li Shuxing’s work, and found that each of his illustrations was a portal into another world, a still life of a fantasy universe. I couldn’t help but be lost in the details.

“What I typically do is, first, make a lot of small sketches,” Li told hxsd.com in an interview. “They don’t need to be very detailed or specific. Finally, I select the most satisfying one to serve as a base and merge best points of the other sketches into it. Continuing to improve the sketch defines its composition. Good composition needs to have a sure grasp of the combination of point, line, area, and volume. I don’t consider details at first. As long as the overall effect is good, that’s fine.”

Editor’s Note: Thanks to John Chu for providing an updated translation of the original simplified Chinese.

Li discusses the illustrations above, many of which were created for an illustration contest called “Unearthly Challenge 2013,” which Li won, in this interview with hxsd.com. Even if you can’t read Simplified Chinese (like me), it’s well worth pushing through the Google Translated interview to see some of the artist’s in progress sketches and to get an inside look at how he creates such wonderful fantasy worlds.

Li Shuxing also runs a busy blog under his online screenname, STAR, where he posts many more illustrations and sketches.

The post Visit the fascinating fantasy worlds of Li Shuxing appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 29, 2014

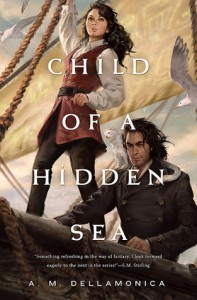

Child of a Well-traveled Sea

Tell if you’ve heard this one before:

A young, perky college student — a little lost as they search for a purpose in their terrifying maturation from youth to adulthood — is whisked away to a fantasy world, thrust into the middle of a crisis that, if they’re not complicit in finding a solution, will be disastrous for their newfound friends. By leveraging their otherworldly knowledge (and modern technology/understanding of medicine/science), they’re able to triumph over the bad guys and restore peace to the troubled fantasy land.

Got it?

You might be thinking of Guy Gavriel Kay’s Fionavar Tapestry, or Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series, Lev Grossman’s The Magicians, or Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice in Wonderland. You wouldn’t be wrong, all of these are popular examples of “portal fantasy.” Unlike protagonists in traditional epic fantasies, who at least understand most of the overarching societal values and some of the physical/metaphysical rules of the world, portal fantasies allow the author to cast a character who has no more understanding of the laws and societies of the fantasy land than the reader themselves (and often less, if the protagonist isn’t an avid fantasy fan who’s probably seen it all before). Over the course of the novel, the reader discovers the world, magic, etc. at the same rate as the protagonist. It’s a tried-and-true formula, but therein lies the issue with most portal fantasy: we have seen it all before.

Art by Sergey Likhachev

Along the way, Sophie, who’s intensely curious and fearless, unravels a plot that threatens the archipelago’s decades-long peace treaty

From the outside looking in, A.M. Dellamonica’s Child of A Hidden Sea isn’t much different than its compatriots. Sophie Hansa and her brother Bram are thrown into the world of Stormwrack, an archipelago-based society made up of over 200 countries, each confined to their own island. Along the way, Sophie, who’s intensely curious and fearless, unravels a plot that threatens the archipelago’s decades-long peace treaty, discovers her hidden heritage (natch), and whets her biologists’ appetite by cataloging every living specimen she can get her hands on (also whetting her biological appetites with a few of the locals, if you know what I mean…). Like I said, we’ve seen it all before.

However, every so often a book comes along that is more than a sum of its parts, and there’s no better way to describe Child of a Hidden Sea. Despite being full of easily recognized character archetypes, genre tropes, and plot devices, Child of a Hidden Sea rises above these factors that anchor down similar novels. Like Noah’s rising seas, Child of a Hidden Seas buries the chaff under miles of water, and lets only the tips of the tallest, most impressive mountains peek through to the surface. It’s not a perfect novel, but it’s so much fun to read, and exploring the world of Stormwrack is so fascinating, that it transcends those issues and exemplifies why they’ve become tropes in the first place.

Art by Justin Gerard

Stormwrack itself is a wonder of world building. Child of a Hidden Sea isn’t a long novel, clocking in at 336 pages, but Dellamonica fills every page with details about the world, its ecology, cultures, politics, and religions without ever falling back on tiring exposition or page-long infodumps. Instead, Sophie and Bram are constantly observing their surroundings, asking questions, and exploring, all the while interpreting and intuiting answers as they nurture their understanding of the world. Each little aspect about the world raises more questions about its origins, and allows the reader to interpret the signs alongside the siblings. Dellamonica weaves some tantalizing hints about the connection between Stormwrack and Erstwhile (the Stormwrackers’ name for Sophie’s home world), but reveals only enough to the reader that everyone will be left with a slightly different interpretation by the end of the book. This aspect above all others begs for Dellamonica to continue writing stories in Stormwrack and peeling back the layers of its twisted, fascinating origin.

The labyrinthine politics on Stormwrack are also handled elegantly by Dellamonica, mostly by virtue of the fact that she ignores the vast majority of the 200+ colonies on Stormwrack, and focuses Sophie’s adventures around three or four of the most extreme/influential societies/religions. Child of a Hidden Sea stands on its own, with its plot wrapped up nicely by the final pages, but along the fringes of Sophie’s story, the reader is shown glimpses of the vast diversity among Stormwrackers, and Dellamonica’s world has a lot of room to grow if she decides to write more novels in Stormwrack.

In Stephen R. Donaldon’s Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, its protagonist (I hesitate to call him a hero), Thomas Covenant, famously rejects the idea that he’s been transported to a fantasy world, and through most of the series the reader is left on their own to decide whether they side with Covenant’s belief, or whether he’s wrong and the fantasy land does exist in truth. It’s a fascinating exploration of the human mind’s insistence on understanding its surroundings. Sophie Hansa attacks the world in a different way: intellectual deconstruction.

Stormwrack, unlike Erstwhile, is filled with magic, and Sophie immediately begins to explore the origins, possibilities and limitations. This jumping-into-the-deep end approach is a natural and believable reaction to Sophie’s dramatic situation, and allows her to avoid the severe depression that follows Thomas Covenant through his own experiences in fantasy land.

What did magic mean, exactly? The ability to defy the laws of physics? To create little pockets of something—space, time, both?—where they didn’t apply? Or to access other universal rules that twenty-first-century science, at home, just hadn’t touched yet?

The spiderweb sail ruffled in the breeze, gaily defying common sense and physics.

I wonder what Bram will say about this?

Early in the novel, Sophie’s innate curiosity is confronted by one of the native Stormwrackers:

“But you seem possessed of a truly all-devouring curiosity—”

“That’s not a disease!” The words came out sounding braver than she felt. If they could teach her Fleetspeak in a matter of hours, they could certainly wipe her memories.

“Those who question find the ill in everything,” Annela said, in a tone that hinted it was a common saying.

Sophie argues with everyone she meets.

Sophie spends most of her time in Stormwrack arguing with everyone she meets. Unlike the average portal fantasy heroine, Sophie does not immediately begin seeking a way to restore the status quo (returning to her world), but instead jumps head first into Stormwrack, fascinated by its otherworldliness and the dense cultural-diversity of the archipelago. The people of Stormwrack, however, are, at best, ambivalent to her presence, and, at worst, actively trying to send her back to her home world — not because she’s fated for disaster (though Dellamonica does have fun with the outsider/prophecy trope), but because she’s a political inconvenience. Sophie spends most of the novel trying to convince the Stormwrackers to allow her to stay in the world.

Art by Adam Paquette

John Scalzi is (in)famous for writing whipcrack science fiction that embraces sharp, hyper-clever dialogue as a main narrative device for pushing a simple plot that relies on likeable characters and amusing situations to keep readers turning pages. It’s become something of a science for Scalzi, and Dellamonica applies the same methods to fantasy. By casting a contemporary heroine, Dellamonica is afforded an easy, modern narrative style that contrasts pleasantly with the Renaissance-era world of Stormwrack.

Unfortunately Sophie’s precocious personality encourages irritating verbal wordplay that can be, even at the best of times, amusing, and at the worst of times, exhausting. Her and her brother Bram are a mile-a-minute partnership:

Bram emerged from his room, looking rumpled and wholly alert. “Someone mentioned my favorite alkaloid.”

“Your caffeine delivery system’s coming. And the steward thinks the guy who attacked Gale might be from a place called Isle of Gold.”

“What are you wearing?”

“Conto gave me some stuff. It’s probably polite to wear it, right?”

“It’s optimal if you’re hoping to look like casual Friday in Alice in Wonderland.”

“If I wanted a lecture from Fashion Cop, I’d have brought Fashion Cop.”

“I’m a first-rate multitasker.”

Art by Nacho Molina

Dellamonica earns the rocky early pages by crafting a plot that naturally builds around Sophie’s personality.

Over time, however, Sophie’s personality begins to grow on the reader, and, like an unchallenged student pushed in educational directions that encourage growth, these irritations and quirks in her character are slowly revealed as strengths and endearing tools that help her navigate the Stormwrack’s labyrinthine political landscape. She continues to challenge everybody in sight, but toward a purpose that the reader is finally invested in (thanks, in part, to the death of one character who, at every corner, attempts to ground Sophie and keep her safe in an unpredictable and potentially volatile situation), and the verbal combat becomes as entertaining and suspenseful as any fireball-flinging, sword-clashing fight scene.

This narrative-style comes to a surprising and satisfying head during the novel’s untraditional climax. Admittedly, this approach might not work for all readers, and during the first chapters, I was worried it wouldn’t work for me, but Dellamonica earns the rocky early pages by crafting a plot that naturally builds around Sophie’s personality, and would play out much differently if Sophie was less confrontational, less clever, or, even, male. There’s a narrative balance to Sophie’s personality versus the accepted norm in Stormwrack that speaks to Dellamonica’s plot- and character-building.

What violence exists in Child of a Hidden Sea is used for great effect, and each violent encounter has consequences that ripple through the entirety of the plot.

What violence exists in Child of a Hidden Sea is used for great effect, and each violent encounter has consequences that ripple through the entirety of the plot. Without falling back on fantasy’s proclivity for resolving issues with violence, or creating character conflict and/or suspense through violence, Dellamonica relies on dialogue and character interactions to provide conflict that remains both tense and amusing throughout the many over-the-top situations that pop up along the way.

Plot contrivances are fairly common in Child of a Hidden Sea. Sophie’s an active character, who’s consistently engaged with moving the plot forward, which is a nice change from the average portal fantasy heroine, who is so often guided along by a hand from the local fantasylanders. However, a lot of the decisions she makes don’t always make sense, and usually lead to one of the two outcomes: a) creating a problem that didn’t need to exist, b) solving a problem in a way that isn’t always clear and/or telegraphed to the reader beforehand. Now, the core of fiction is to present the protagonist with problems, and watch as they strive to overcome them, but Sophie’s problems seem to occur as often because she makes out-of-left-field decisions, as much as because the novel’s working conflict (particularly the man named John Coine, referenced in the quote below) are actively getting in her way.

Take the quote below, for example:

“We were looking for someone who’d tell us what was up with the Ualtarites. A busy port…” She faltered. Why did all of her ideas sound so much better before she gave them voice?

You’re not a cop, Bram had said.

“Sorry,” she said. “Is this stupid?”

“It’s quite sound,” Parrish said. “Let them think we’re concerned enough to consider seeking the Heart.”

“We are concerned,” Bram said, coming up on deck. “We’re super concerned.”

Sophie pretended she hadn’t heard. “Okay. We’ll play-act at looking for the Heart and snoop around trying to figure out why the Ualtarites are helping John Coine.”

Buy Child of a Hidden Sea by A.M. Dellamonica: Book/eBook

Child of a Hidden Sea is portal fantasy at its best.

Despite having a plethora of options, many of which involve the aid of national authorities or police/military groups, Sophie’s solution for fooling John Coine and his partners is to wander around a port pretending to be searching for one thing, when she’s actually just snooping around for another. As a reader, I was screaming at Sophie with at least three more sensible options for entrapping Coine, but she couldn’t year my words through the pages of the book. It’s fun, and the plot gets moving again, but eye-rolling decisions (not only from Sophie, but most of the cast) and plot diversions are plentiful and require some suspension of belief on the part of the reader. Sophie’s tale will whip you around like a rollercoaster, so, just like those amusement park rides, you must let yourself be caught up in the momentum, give yourself over to the avalanche of plot twists and contrivances, and then you’ll have a blast just getting from the beginning of the journey to the end.

Child of a Hidden Sea is portal fantasy at its best. A.M. Dellamonica writes with a fresh voice, and the world of Stormwrack is filled with diverse characters and cultures, creating a genuine sense of empathy in readers as they travel alongside Sophie Hansa in her quest to maintain peace in the archipelago. By rising above its genre tropes, Child of a Hidden Sea proves that there’s still life in portal fantasy, just as long as the author breathes hard enough. Child of a Hidden Sea tells a complete story, but the top-notch worldbuilding, fun dialogue, and hints of future adventures ensure that fans will be clamouring for more stories in Stormwrack.

The post Child of a Well-traveled Sea appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 28, 2014

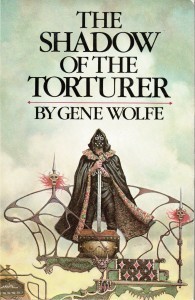

“Gene Wolfe: The Reliably Unreliable Author” by Chris Gerwel

Author’s Note:

This piece is meant to be a broad-ranging retrospective on the work of Gene Wolfe, one of the most significant authors of speculative fiction. As I imply in the essay below I think it is quite impossible to “spoil” a Gene Wolfe novel (each work is just too protean), but I do discuss both his plots and possible interpretations of several puzzles his books present. So if you haven’t read the books in question, you’ve been warned.

A good essay, like any good story, needs solid bones.

A good essay, like any good story, needs solid bones. It needs a foundation, a structure, a framework on which the subject can hang. When I sit down to write about a genre, or a story, or an author’s work I always start with that core: I try to find some central tenet, a grain of sand small and indivisible, some immutable truth inherent to the work around which my analysis can accrete. But trying to sift the work of Gene Wolfe – one of my favorite authors – I find that each grain becomes as mutable, as multifaceted, as slippery as his work itself. And maybe it is that slipperiness, that coy teasing play, that is itself the heart of Wolfe’s writing. Perhaps that is as good a place to start as any.

Gene Wolfe – as he has stated time and again – sets out to write books which can deliver a different kind of enjoyment each time they are read or re-read. He engineers his work from the very start to operate on multiple levels, to manipulate the reader using different levers.

From Genre Roots…

Art by Richard Bober

At first blush, Wolfe writes science fiction and fantasy. His work features alien planets (The Fifth Head of Cerberus), time travel (The Book of the New Sun), spaceships (The Book of the Long Sun), ghosts (Peace), alternate realities (There Are Doors), monsters and gods and demons (too many titles to list) – most every science fictional trope one could possibly name. Wolfe himself clearly self-identifies with the SF genre, and he is entirely unashamed of that association. Almost all of his stories purposefully rely on traditional science fictional tropes, recognizable to readers of the golden age sf that preceded Wolfe’s own work.

Wolfe got his start publishing in the late ’60s and early ’70s, a tumultuous time in the sf genre. His contemporaries were writers like Harlan Ellison, Samuel Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin, Michael Moorcock, J.G. Ballard, Joanna Russ – a generation of writers who were actively challenging the genre’s hard SF pulp roots, dragging it (kicking and screaming) towards literary complexity, depth of character, and breadth of style.

At various points in his life, Wolfe has given interviews where he either acknowledges his role in the New Wave movement, or disavows it. And this itself is another way in which Wolfe’s work and history is so multifaceted. When we look at his texts, we can see that Wolfe’s bifurcated self-characterization is exactly correct:

Along certain dimensions – authorial intention, philosophy of art, and narrative structure – Wolfe’s sensibilities align firmly with the New Wave (with notable stories in Ellison’s Again, Dangerous Visions and Moorcock’s New Worlds, both flagship publications of the New Wave movement). However, along other equally important dimensions – prose aesthetics, thematic motif, use of symbolism, and onomastics – he rejects much of the New Wave’s post-modern tendencies and instead applies the techniques of the literary modernists eschewed by most sf writers in general and the New Wave movement in particular.

…to Modernist Literary Branches…

It is difficult to read works like Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun and not think of James Joyce’s Ulysses or T.S. Elliot’s The Waste Land. Wolfe’s most significant (and arguably best-known) work, The Book of the New Sun is written in prose so dense with literary, historical, and religious allusion that its analysis has generated multiple significant books of criticism (a special mention should be made of Michael Andre-Driussi’s Lexicon Urthus – an impressive work of systematic scholarship).

These words themselves, and their etymology and the contexts in which they are used are themselves key to deciphering the symbolism at play throughout the text.

Ostensibly, The Book of the New Sun is a far-future dying earth novel in the mold of Jack Vance’s classic Dying Earth (an acknowledged and obvious influence on New Sun‘s aesthetics, structure, and world-building). We meet our narrator, the young Severian who is a member of a guild of torturers (whose job, naturally, it is to torture and execute criminals). We follow Severian’s transgression against his order, his punishment, and his journeys across his decaying and corrupt world which ultimately lead to his becoming Earth’s (at this point in our distant future called “Urth”) ruler, savior, and (eventually in The Urth of the New Sun which follows) destroyer, and re-creator.

Superficially, the setting is a classic dying earth environment, with the decadence, moral and political corruption, blurring of technology and magic, and mythologizing of the reader’s far-removed time period that Vance pioneered. However, the techniques through which Wolfe paints this fictional world are very different: For one, Wolfe eschews the use of neologism. The words that he uses – however strange they may seem – are real English, Greek, or Latinate words, however obscure. These words themselves, and their etymology and the contexts in which they are used are themselves key to deciphering the symbolism at play throughout the text.

This use of language is entirely Joycean in its approach, and its effect is to make the prose work on at least three different levels: There is a superficial meaning which can be taken at face value, interpreted simply as it is read to provide a clear chronicle of the narrative’s events. Below that, there is a deeper meaning which ties to one or another of the story’s central mysteries, and below still that there is an allusive layer to Wolfe’s word and name choices where referenced legends, myths, or texts provide further clues to the word or name’s significance as symbol within the novel’s underlying themes.

It is this density of language and its multiplicity of meanings which encourage close readings of Wolfe’s texts, and which encourage multiple re-readings of his work.

Though such multi-layered and allusive word choice is a common technique used by the modernists to powerful effect (making the likes of Joyce, Elliot, Yeats, Borges, and Faulkner the delight of modern lit professors), it is one rarely seen in speculative fiction. Though other authors – notably Tim Powers, Michael Swanwick, and Guy Gavriel Kay – have written multi-layered texts where each character or plot point corresponds structurally to other cultural touchstones, Wolfe is unique for the sheer density of such extra-textual allusion.

It is this density of language and its multiplicity of meanings which encourage close readings of Wolfe’s texts, and which encourage multiple re-readings of his work. Each time you come to a Gene Wolfe novel, you will discover new depths of hidden significance to (often) seemingly inconsequential details.

Art by David Grove

…which Obscure Mysteries…

Such layering of the narrative is not a technique unique to The Book of the New Sun. In fact, it is one of Wolfe’s consistent literary tricks which he applies across most of his work. In his third published novel, Peace, he does this even more subtly.

Such layering of the narrative [...] is one of Wolfe’s consistent literary tricks which he applies across most of his work [...] a puzzle which must be identified and then solved by the reader’s own effort from clues in the text.

That novel is – seemingly – a series of disjointed reminiscences told by an elderly man. However, what Wolfe never states explicitly – a puzzle which must be identified and then solved by the reader’s own effort from clues in the text – is that the narrator is dead (the story is told by his ghost), that the setting from which he is reminiscing is Purgatory in the form of a memory palace, and that he is in all probability a multiple murderer.

On a first reading, it is easy to miss almost all of the clues that lead the reader to such conclusions. In this, the novel brings to a mind a slightly less-aggressive (or at least less angsty) version of Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground. However, on re-reading Peace, the significance of individual words (such as a the first sentence “The elm tree planted by Eleanor Bold, the judge’s daughter, fell last night.”) suddenly becomes clear (when a connection is made to a different, single, and seemingly unrelated line of dialog in the novel’s latter third).

Art by Don Maitz

This technique fundamentally relies on the narrator’s unreliability, which philosophically Wolfe links to the fallibility of the human condition (or at least human cognition). The use of unreliable narrators is as consistent as Wolfe’s literary allusions throughout his oeuvre: Whether it is Alden Dennis Weer in Peace, Severian in The Book of the New Sun and The Urth of the New Sun, Patera Silk in The Book of the Long Sun, Horn in the The Book of the Short Sun, Mr. Green in There Are Doors, or perhaps most interestingly Latro in Soldier of the Mist and its sequels, the vast majority of Wolfe’s narrators and perspective characters are explicitly shown to be unreliable.

Consider Latro – the character (and as a perspective character, especially) who I consider to be Wolfe’s most fascinating construct. Ostensibly, he is an early Roman mercenary wounded in the Battle of Plataea (where he fought for Xerxes). Having received a nasty headwound, Latro begins to suffer from both retrograde and anterograde amnesia: every time he goes to sleep, he loses his memory of the last twenty four hours. To keep him functional, he is given scrolls to use as a diary (basically a “Read This First” type of document) to keep him grounded as he lives his life.

Latro is unreliable on many levels, not least because of the explicitly present holes in his memory. But at the same time, he is an otherwise uneducated mercenary with limited ability to write (per the “translator” of the found scrolls), with the largely unscientific worldview of his time, and who would have been writing his recollections in haste in often difficult circumstances (being a soldier in the field and all).

This poses a central unresolved (and largely unresolvable) mystery for the reader: What is the reality of Latro’s story? When Latro interacts with the gods, monsters, and demons of ancient Greece, are these hallucinations brought on by his all-too-real injuries? Are they factual experiences, interpreted through a haze of mysticism brought on by the narrator’s limited vocabulary and understanding? Or should they instead be interpreted exactly as they are presented, as real magic in the world?

The centrality of such puzzles – to which Wolfe often gives equally plausible “solutions” – is a hallmark of his novels, and appears in almost all of them. And when we consider Wolfe’s work as a whole, the puzzles only deepen: the Latro sequence, for example, can be read as a inversion of the Book of the New Sun. At the most basic level, Severian has a stated inability to forget anything, though he can choose to lie and is inconsistent in his narrative. While Latro, by contrast, has an inability to remember anything, yet his narrative is consistent throughout. Which story, then, is the more stable? Which narrator the more trustworthy? And how does that reliability (or equal unreliability) affect our exploration of each texts’ other mysteries?

Art by Bruce Pennington

…but Still Remain Problematic…

Despite (or because of) the intellectual complexity of Gene Wolfe’s work, I find it quite enjoyable. However, his texts remain problematic in one fundamental way: It is hard to provide any kind of comprehensive look at Wolfe’s work without discussing the treatment of women in his fiction.

And here, I find myself cringing.

Wolfe has a tendency to portray women in positions of either subjugation (particularly in The Book of the New Sun), villainy (There Are Doors, Peace), or otherwise to consign them to a status subservient to his male characters.

Considering the fictional environments of Wolfe’s stories, and the (often dark) motifs his stories explore, it is tempting to excuse his fictional portrayal of women as being in service to the themes of his fiction. It’s a very tempting excuse, especially when we consider Wolfe’s control of craft and attention to detail. Surely, one might think, a writer so technically proficient as Wolfe would be aware of problematic material and only apply it purposefully in support of his art.

Surely, one might think, a writer so technically proficient as Wolfe would be aware of problematic material and only apply it purposefully in support of his art.

Unfortunately, when we consider the way Wolfe discusses women in his numerous essays, interviews, and public speeches, we can find that his problematic (by modern standards) views extend beyond his fiction. Such attitudes lead me to believe that excuses for the treatment of women in Wolfe’s fiction are merely an exculpatory fig leaf.

If Wolfe’s attitudes towards women are problematic, however, I believe they stem from a combination of the standards of his youth (Wolfe was born in 1931), his background, and his perception of the relationship between gender and human nature (where Wolfe seems to perceive a fundamental link between the two). This is not an excuse – I (strongly) disagree with such views, and I am uncomfortable when they are articulated by a writer whose work I so admire. But like all readers, I suppose I contain multitudes.

And if Gene Wolfe can write such significant works with so many layers to them, then as a reader I can respect his artistry while disagreeing with his attitudes.

…and (Possibly?) Influential on the Genre

Gene Wolfe’s best-known work is undoubtedly The Book of the New Sun, with other titles like Peace probably a close second (especially following the effusive praise offered it by authors such as Neil Gaiman). In general, I find that sooner or later at every con I go to, or every time I’m in a bar with some writers of science fiction or fantasy, Gene Wolfe’s name (or the name of a character, or the title of a book) comes up.

Gene Wolfe is – first and foremost – a writer’s writer. Any writer of fiction who reads his work with an eye for detail can spot his techniques. And yet very few can emulate them. Some have come close – for example, Jeffrey Ford’s Well-built City trilogy shares many structural similarities to Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun (while nevertheless being entirely its own fascinating and beautiful work), yet I am hard-pressed to think of any examples who equal him.

His style, his structure, and his aesthetics are uniquely suited to critical analysis and the close reading beloved of so many genre fans and critics.

Secondly, I believe he is a critic’s writer – particularly given his penchant for literary allusion and modernist techniques. His style, his structure, and his aesthetics are uniquely suited to critical analysis and the close reading beloved of so many genre fans and critics. However, even though Wolfe applies modernist techniques with aplomb, his work has gone largely unnoticed outside of genre criticism. Genre critics such as John Clute have written extensively and eloquently about Wolfe’s work, but outside of genre criticism the academy has been relatively quiescent. Clute himself mentions this fact in his entry on Wolfe in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, where he posits that this is due to Wolfe’s fundamental reliance on science fictional plot devices and tropes. Perhaps, one might think, Wolfe is too rooted in science fiction for the wider literary environment to recognize his significance. If so, that is a shame. Because Wolfe brings two notable innovations to the modernist toolkit: Plot (those very same science fictional tropes that the academy neither understands nor respects), and optimism. In this, Wolfe maintains a stance of being neither one nor the other.

While Wolfe’s prose techniques are modernist in nature (and so reject the largely post-modern tendency of his New Wave contemporaries), the thematic thrust of Wolfe’s novels stands in sharp contrast to typical modernist fare. This is because unlike most of the modernists (who tended towards a sense of bleak desolation and alienation following their experiences of the First World War), Wolfe’s often-bleak and often-desolate worlds are leavened through his Catholic faith, whose symbols when introduced into the text bring recurring themes of redemption, forgiveness, and rebirth.

Buy: Novels by Gene Wolfe

In all of this, one can rely on Gene Wolfe in one fundamental fashion: He is reliably an unreliable author. He toys with his readers, plays coyly with us. He makes us work at understanding his fiction, makes us study his texts and come back to them time and again. And each time we do, we find a different book, with a different interpretation, different meaning, and different significance.

Wolfe’s works are an intellectual challenge. They are (at least for me) more fun than similarly challenging work by writers like Joyce, Faulkner, or Elliott. But there is no question that Wolfe’s books take effort to read, and effort to enjoy. But the depth of enjoyment I have gotten from them has been well equal to the effort.

Related Reading

Lexicon Urthus by Michael Andre-Driussi

The Long and the Short of It: More Essays on the Fiction of Gene Wolfe by Robert Borski

Strokes by John Clute

Solar Labyrinth: Exploring Gene Wolfe’s “Book of the New Sun” by Robert Borski

Attending Daedalus: Gene Wolfe, Artifice, and the Reader by Peter Wright

The post “Gene Wolfe: The Reliably Unreliable Author” by Chris Gerwel appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 25, 2014

The Imagined Realms of Julie Dillon

It’s no secret that I’m a big fan of Julie Dillon’s artwork. In fact, when it came time to redesign A Dribble of Ink earlier this year, I knew I wanted to feature some gorgeous fantasy-inspired art in the header, and Julie, with her warm, colourful style, and ability to imbue her art with an otherworldliness without losing its grounded sense of wonder and emotion, was the perfect choice for the project. Luck was with me, and now A Dribble of Ink is graced with a beautiful original piece of Dillon’s artwork.

Dillon’s star is rising, perhaps most evidently by her nominations for the 2012 and 2013 Hugo Awards. In 2013, she became the first woman to be nominated in the Best Professional Artist category since Rowena Morrill in 1986 (1986! 28 years!).

Earlier this month, Julie Dillon launched a Kickstarter campaign for Imagined Realms: Book 1, which Dillon describes as “the first in a series of annual art books that I am illustrating and self-publishing.” Each annual volume of Imagined Realms will contain 10 exclusive illustrations, a pretty exciting proposition for Dillon’s growing legion of fans.

Back Imagined Worlds: Book 1 on Kickstarter

“Dillon, like John Picacio and Donato Giancola embraces that sense of concrete imagery without becoming literal,” Justin Landon said in his tribute to Dillon’s artwork, describing her talent for melding impressionistic vision and vast imagination.

“Color is one of my primary focuses,” Dillon told Erin Stocks of Lightspeed Magazine in an interview. “I’m very easily distracted and won over by bright vivid color. I particularly like contrasting color schemes, and when I first begin coloring my sketches I’ll often start with a very strong complimentary color scheme (red and green, blue and orange, etc) as a base, and tone it down a little as I work on it further. I’ve been trying to reign in my color schemes a little bit more lately and try keeping things more muted, but I usually cave in and resort to adding in bolder colors by the time I’m finished.”

“I got into art because I love to create, to see the world in new ways, and to stir the imagination of others,” Dillon told Kickstarter backers. “I have long wanted to start putting together my own books and work on more personal projects. Imagined Realms gives me the opportunity to spend more time creating my own illustrations and projects, and also gives me the chance to create more illustrations that feature positive and diverse representations of women.”

If you enjoy Dillon’s art as much as I do, I hope you’ll consider taking the time to check out her Kickstarter and maybe pledge (there are some terrific rewards, including beautiful prints of the artwork feature in the book!) a few bucks in support.

Back Imagined Worlds: Book 1 on Kickstarter

View Julie Dillon’s Art:

Website

DeviantArt

Tumblr

The post The Imagined Realms of Julie Dillon appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 24, 2014

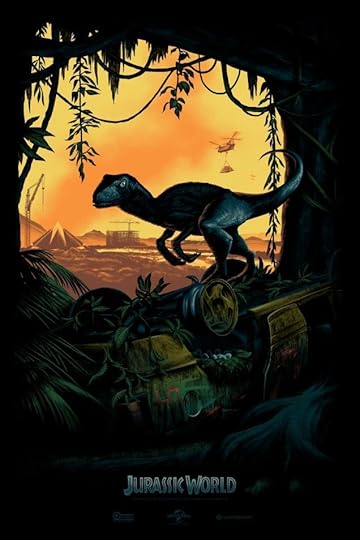

The drool-worthy SDCC teaser poster for Jurassic World

This teaser poster for Jurassic World, revealed today at San Diego Comic-Con, is a beautiful throwback to the original Jurassic Park, featuring the iconic Jurassic Park Tour Vehicle, and a theme park under construction. Full of dystopian symbology — ruined car, city/urban environment overrun by jungle/plant life — this poster is more than just a pretty bit of imagery, there’s a lot there to confirm the rumours that Jurassic World will feature a rundown, seen-better-days version of the Jurassic Park originally imagined by John Hammond in the original film/novel. The dino-nest in the vehicle’s wheel well suggests the decay and rampant dinoism has been going on for a long time.

This rundown of the leaked plot, also courtesy of io9, is suitable, entertaining camp:

Jurassic Park is back in business, but business appears to be flagging. So someone has the fantastic idea to start mixing dinosaur DNA together to create new dinosaurs. Somehow, they end up with a tyrannosaurus rex, a velociraptor, a snake and a cuttlefish — because of its camouflage abilities — that inadvertently creates a perfect killing machine that of course gets loose and starts eating people. It’s basically like evil dinosaur Predator.

How to stop a monster that was obviously going to murder everything it saw from day one? Good dinosaurs, trained by Chris Pratt’s characters, including a regular T.rex and velociraptor.

More about the leaked plot can be found on JoBlo.

My hype levels for Jurassic World are at a point where the movie can’t be anything but a disastrous disappointment, but I can’t help it. Over-the-top plot, Chris Pratt, gorgeous concept art/visual design, sexy throwback posters? Sign me up.

The post The drool-worthy SDCC teaser poster for Jurassic World appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 23, 2014

Melanie Rawn begins work on The Captal’s Tower

“Yes, I will write Captal’s Tower,” Mealnie Rawn revealed to her fans on Kate Elliott’s blog yesterday. Anyone who’s followed Rawn’s career knows what huge news this is, but for those that aren’t familiar with Rawn’s Exiles trilogy, know that the path to the trilogy’s conclusion has been slow and fraught with peril.

“I’m very sorry it’s taken so long. My sincere thanks to all of you who have been so patient,” Rawn told fans. “I’m currently writing the fifth book in the Glass Thorns series, and after that my plan is to get to work on Captal’s Tower.”

The Captal’s Tower is the final volume of Rawn’s Exiles trilogy, which began in 1994 with The Ruins of Ambrai. Fans have been waiting for the end of Collan Rosvenir’s tale since the 1997 release of the second volume, The Mageborn Traitor. Personal issues, including clinical depression, prevented Rawn from completing work on The Captal’s Tower in the late ’90s.

This is, of course, fantastic news for fans of the trilogy, who have been waiting for 17 years for its conclusion, and great news for Rawn, who begins work on a project that has long cast a shadow over her other works of fiction during the past two decades. Time is often the best and only medicine for such illness. Though work on The Captal’s Tower stalled, Rawn has been a productive author during that period of time, publishing six novels and several short stories.

In the author’s note for her novel, Spellbinder, published in 2007, Rawn addressed the issue surrounding To Captal’s Tower. “To those who are disappointed that this isn’t another book — The Captal’s Tower or an offering the Golden Key or Dragon Prince universes — well, what can I tell you?” she wrote. “Life happens. So does clinical depression. [...] When I was able to write again, I wanted — needed — to do something entirely different than anything I’d done before.”

As one can imagine, Rawn has faced criticism similar to that directed toward popular authors such as George R.R. Martin, Scott Lynch, and Patrick Rothfuss. However, the enthusiasm and hunger for The Captal’s Tower remains strong and speaks to the quality of the first two volumes in the trilogy. This seems as good a time as any to reread Neil Gaiman’s wonderful post about reader entitlement.

There is no release date for The Captal’s Tower, and Rawn has said on her website that it can take anywhere from “18 months to five years” for her to write a book. So, be excited, but also patient.

For more Melanie Rawn-goodness, Judith Tarr’s recently began a re-read of The Dragon Prince trilogy for Tor.com, which is a great way to revisit a genre classic.

The post Melanie Rawn begins work on The Captal’s Tower appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 21, 2014

“With Fist and Sword: Epic Fantasy and Shounen Anime Heroes” by Django Wexler

I’ve read an awful lot of fantasy, and watched an awful lot of anime, and both canvases are incredibly broad and notoriously hard to characterize.

When I began to contemplate an essay comparing and contrasting the traditional hero narrative in fantasy fiction and anime, I found myself in a bit of difficulty. I’ve read an awful lot of fantasy, and watched an awful lot of anime, and both canvases are incredibly broad and notoriously hard to characterize.

Fantasy, after all, includes classics like Lord of the Rings, heroic secondary-world epics like The Wheel of Time, wainscot fantasy like Harry Potter, and the magical realism of The City & The City, covering sub-genres like urban fantasy and steampunk in between. It’s very hard to write a coherent comparison that covers both C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia and Max Gladstone’s Three Parts Dead, for all that we shelve them in the same genre.

Similarly, anime is unbelievably diverse, more so than all but the most hardcore of fans realize. (Because the US translation companies skim the cream of the crop, picking the hit shows and often passing over the stuff with less broad appeal.) From staples like Dragonball, Sailor Moon, or Naruto, anime goes all the way to Revolutionary Girl Utena (which is so symbolic as to be almost abstract) and Non Non Biyori (which is about a bunch of girls in a rural village chatting about nothing in particular). It includes every genre of speculative fiction we have in the US, and some we don’t.

All this makes generalizations a bit difficult, so, for the purposes of this essay, we need to narrow the field a little. I’d like to compare a particular popular strain in epic fantasy with a particular style of shounen anime. On the fantasy side, you might think of it as the “farmboy who saves the world” story, though there’s usually more to it than that. It includes The Wheel of Time, The Belgariad, The Chronicles of Prydain, Harry Potter, and many, many others. Veteran fantasy readers should recognize the tropes more or less immediately.

“Shounen,” in an anime context, describes a show primarily intended for a young male audience, or one deriving from comics running in magazines aimed at that same audience. They include a lot of the shows most familiar to American audiences: Dragonball is a classic shounen anime, as is Naruto, Bleach, Inuyasha, Hunter x Hunter, Rurouni Kenshin, and again too many others to list.

These two sub-genres have a great deal in common. They tell, in essence, similar stories: the tale of the rise of a hero and his (almost always his, which we’ll touch on later) growth in power and confidence. This growth is a critical component of the story arc; other genres may feature protagonists who get more powerful as the series goes along, but in this style of epic fantasy that journey is essentially the point of the series. (Note that this means The Lord of the Rings doesn’t qualify! Frodo grows as a character, but he’s still a hobbit; compare that to the arcs followed by Rand al’Thor or Harry Potter over the course of their series.)

The critical difference between the epic fantasy and the anime approach, however, has to do with the main character’s motivation. Epic fantasy protagonists almost always have their destiny imposed on them from the outside; left to themselves, they either would not want to be part of great events or are unaware that such things are even possible. (Rand and Harry, respectively.) The reason that the Beloved Peasant Village (and its subsequent destruction by the Forces of Evil) is a well-worn trope is that the epic fantasy protagonist needs a kick to get him moving on the greater things. Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey often describes this kind of story very well.

Shounen anime protagonists, on the other hand, tend to be self-motivated. If they start out in a peasant village, they’re almost always planning to escape from the confines of a provincial life and embark on an adventure. They have something they want — power, revenge, knowledge, riches — and it is this unstoppable drive that makes them the hero. While a large part of the arc is the same, this difference makes the ultimate story very different.

(Caveat: My conscience forces me to add that of course I am not describing all epic fantasy or all shounen anime here. Even sub-genres are huge, and counter-examples can be found to anything. I only want to talk in very general terms to illuminate a few interesting contrasts.)

Art by Giorgia Lenzi

Heroes: Where do they come from?

Both epic fantasy and shounen anime heroes are usually of humble origins, almost always in the lowest available position relative to his peers.

Both epic fantasy and shounen anime heroes are usually of humble origins. The epic fantasy hero is, in the classic version, the orphan farmboy unaware of his destiny, and sometimes of his own origins. Rand al’Thor grew up in a tiny village, and Harry Potter lived under the stairs. Other “orphans” turn out to be princes, scions of ancient dynasties, or heirs to great warrior traditions.

On the shounen anime side, the hero almost always begins in the lowest available position relative to his peers. Sometimes this is pretty similar to the fantasy style; Luffy from One Piece is a penniless vagabond, Goku from Dragonball is an orphan. Sometimes an ordinary human, like Ichigo from Bleach, gets sucked into a world where ordinary humans are cannon fodder. Naruto lives in a ninja village, but among ninja he’s still at the bottom of the pecking order, and similarly Inuyasha, as a half-demon, is reviled by humans and demons alike.

This makes a lot of sense, story-wise. Since the basic arc of the story is the character’s gain of power and ability, they need to start from a fairly low point. Because they also gain knowledge along with the viewer, they tend to start out being pretty ignorant of the “real world” in which the story takes place — either the world outside the village, the world of magic, or what have you. This also means they’re young (sometimes very young) and inexperienced. More on this below.

Who are they?

Buy the Song of the Lioness Quartet by Tamora Pierce: Book

Typically, the main characters of this kind of story are crafted to be easy for the audience to identify with. (This also means you can see the assumed audience by looking at the main character.) They tend to be in their late teens (though the anime heroes are younger), male, and not particularly distinguished in terms of skills or abilities. The age, as I mention above, is both to put them on a level with the reader and to provide a convenient reason why they don’t know anything about the world. Their lack of skill, like their lack of status, gives them a low base to begin their arc.

Shounen magazines are for boys, and clearly marked as such, while their counterpart shoujo (girls) magazines run very different stories.

It’s a bit harder to say why they tend to be male, since the answer has more to do with demographic trends among readers/viewers and institutional sexism in the industry, which is a bit outside the scope of this article. On the anime side, shows (and comics) are strongly segmented by their target demographic, especially for teens — so shounen magazines are for boys, and clearly marked as such, while their counterpart shoujo (girls) magazines run very different stories. In epic fantasy, the stranglehold of boys on this kind of story seems to be breaking up at last, but there’s a long way to go. Suffice to say, there’s no intrinsic reason why the hero should be male (since these are usually not stories about gender) but he traditionally has been, with a few welcome exceptions. (Tamora Pierce’s The Lioness Quartet springs to mind.)

What makes them special?

This is where we start to get at the essential contrast between the two sub-genres. In epic fantasy, the main character is almost always chosen in some way, shape, or form. Sometimes he is the unwilling recipient of power he doesn’t understand, sometimes he is the subject of a prophecy, sometimes he is marked from birth as special in the eyes of the gods. However it happens, the hero is in a class of his own from the beginning, although it may take some time to recognize it as such. This rarely provides any immediate benefit, however — any powers are unreliable or quixotic, and being prophesized to defeat the Dark Lord doesn’t make actually defeating him any easier.

The shounen anime protagonist, on the other hand, is usually not marked out, at least among his potential peers. He may have something that sets him apart from ordinary people, but so do many others, and there’s nothing that makes him particularly worthy of note. Instead, he is separated by his intrinsic drive, a goal that pushes him to work harder, train longer, and generally never give up.

Art by palnk

So Rand al’Thor is the Dragon Reborn whether he wants to be or not — he inherits a destiny, along with unbelievable power and a nasty set of problems.

So Rand al’Thor is the Dragon Reborn whether he wants to be or not — he inherits a destiny, along with unbelievable power and a nasty set of problems. Harry Potter is the Boy Who Lived, whether he knows it or not. Goku, by contrast, is an alien, but far from the biggest or baddest alien. Ichigo gains shinigami powers, but he’s still out-ranked by a whole organization. Maka from Soul Eater (a very rare female example, even if she has to share main character status) attends a whole school for Meisters. The anime characters almost always have the option to sit back, to not adventure, to let someone else handle it, while the epic fantasy characters are dragged kicking and screaming into their fates.

Who teaches them?

Mentors feature heavily in both epic fantasy and shounen anime, as one might expect of stories that are mostly about watching a character’s knowledge and power grow. Because of the difference in motivation, though, the mentors serve different roles in the story.

The epic fantasy mentor is usually the element that gets the story started. He or she arrives in town, often just ahead of the villains, and spirits the main character off to begin his quest. If these characters need to be dragged into their roles, it’s usually the mentor who does the dragging. As the quest goes on, the mentor teaches the hero; skills, certainly, but more importantly to believe in himself and in his destiny. Dumbledore serves this role for Harry Potter, of course, along with his fellow professors, while Lan and Moiraine get Rand out of the Two Rivers in The Eye of the World.

The anime hero comes by his mentor differently. Because he’s self-motivated, he doesn’t need someone to turn up at his humble village and drag him away. Rather, the mentor is often the object of a quest, usually the first quest the hero undertakes. Playing “Find the Mentor” can be an adventure in itself, as they like to live in inaccessible areas, and once found they usually impose tests and conditions before they agree to train the hero. Rather than the mentor convincing the hero of his destiny, it’s the hero who convinces the mentor that he is worthy of instruction, and is the one to solve whatever problem he’s set out to deal with.

Once acquired, the relationship between the hero and the mentor progresses similarly in both cases. The hero grows steadily in power, though he may not realize it while he under the mentor’s protection. At some point, though, that protection is stripped away, and the mentor leaves. Often — especially on the fantasy side — the mentor dies, though sometimes less than completely convincingly. (Gandalf the Grey being the archetypical example.) Either way, the hero is left to carry on alone, empowered by his training but vulnerable without the guidance of his teacher.

This is familiar but powerful story trope. The feeling of leaving the nest, of operating for the first time without guidance and supervision, is one that most of us have felt at one time or another, and it feels natural in a story centered around the gradual building of a fledgling into a hero. The mentor serves as a surrogate parent, since the actual parents are almost always either dead, absent, or left behind at the beginning of the quest. Surpassing this teacher, and moving on, is a key milestone on the road to heroism that marks the beginning of the transition to truly “adult” status.

Who helps them?

Both the shounen anime hero and the epic fantasy hero usually acquire companions as they go about their quests. This entourage helps the hero through their trials, provide commentary and specialized knowledge, and serve as plot hooks to keep things moving. In most ways they function similarly across the two genres, and in particular, the relationship of the skills of the companions to the skills of the hero is similar.

Roughly speaking, the hero is rarely particularly good at anything. In epic fantasy, the hero begins as a callow youth, without much in the way of knowledge of power, whereas his companions are often either more obviously talented or already have considerable achievements in their fields. The companions will thus fill roles like “the skilled ranger”, “the smart one”, “the healer”, “the swordmaster”, and so on, while the hero doesn’t have anything particularly going for him other than the destiny that makes him the hero.

A shounen hero, on the other hand, usually has at least the potential to be very powerful, and the will to keep on going no matter what. Frequently, though, he can’t harness that power effectively, because he’s a novice at whatever skill it uses. His companions, on the other hand, are talented in some field, but invariably need the protagonist to ultimately solve their problems. This often takes the form of the companions being convinced that the problem is impossible, and ready to give up, while the hero refuses to surrender with the implacable grit that is the essential attribute of the shounen hero.

Returning to our examples, Rand al’Thor takes a lot longer to come into his power than even the other characters who accompany him from the Two Rivers, and initially people like Lan do most of the fighting. It’s only as the story develops, and his power increases, that he outstrips them. (Rand is actually unusual among epic fantasy protagonists in that he spends a lot longer at full power than usual; more typically, the hero achieves his full strength only just before the Final Battle.) Harry Potter immediately acquires Hermione, who is better than him at everything academic or magical, and Ron, who can explain the wizarding world and provide exposition.

Shounen heroes often have much larger entourages, sometimes well into the double-digits of secondary characters. In epic fantasy, companions can be acquired in a variety of ways, but the shounen hero gets his (except for perhaps a few who come with him from home) almost exclusively by fighting them. In the land of the shounen heroes, fighting someone and defeating them is a sure-fire way to get them to join your team, provided you’re generally honorable about it and act kindly towards them afterward. Dragonball alone provides endless examples of this, to the point where Goku’s crew has a majority of former villains.

Who Do They Fight?

This is one area where the two genres differ wildly. Epic fantasy protagonists, going all the back to mythology and The Lord of the Rings, tend to be matched against villains who are the incarnation of pure evil. Creatures like Sauron or The Dark One are the standard here — forces of nature, outside of conventional motivations, who pursue their dark agendas because causing evil is their very nature. Even in Harry Potter, where Voldemort has a human(-ish) face, there isn’t a real attempt to humanize him or provide justification for his actions.

Much more dangerous, and more central to the plot, are the villains who have a coherent(-ish) philosophy and a reason for what they do, although often an ugly one.

The shounen hero, on the other hand, is almost never confronted with pure or mindless evil. The closest he comes to it is villains who are obviously corrupt, greedy, or venal, but those are usually easily disposed of. Much more dangerous, and more central to the plot, are the villains who have a coherent(-ish) philosophy and a reason for what they do, although often an ugly one. Battles between the hero and the villain thus become a comparison of competing ideologies, where the victor is the one who breaks his opponent’s spirit by demolishing his philosophical position. (This is one reason many shounen anime are very “talky”; the other is that talking is cheap to animate.) After the hero is victorious, this often results in the villain joining his team, as discussed above, because he has now been convinced the hero’s philosophy is superior.

Epic fantasy generally retains a fairly clear-cut notion of good and evil as objective, abstract constructs, often physically embodied in the universe. This allows the destiny of the hero to make some kind of sense — a Chosen One who was unsure if he’d been chosen by the right side would not be terribly effective. The readers are rarely intended to be unsure who is in the wrong in any given conflict, at least if the ultimate villain is somehow involved. (This tendency is almost completely reversed in more recent, “grimdark” fantasy and its related sub-genres.)

The shounen world rarely has such obvious moral touchstones, because the point of the hero’s journey is to establish and prove the dominance of his particular set of morals and ideas. This makes it sound more sophisticated than it often is; shounen philosophy is usually pretty basic, and breaks down into things like “you should always help people” vs. “the ends justify the means”. The villains often believe things like “sacrifices are necessary for the greater good” and need to be convinced otherwise by force.

One exception to the rule that shounen villains are humanized and complicated comes at the very end of the story, where the final villain is revealed. Then, sometimes, the previous head villain will join the hero’s side, only to reveal some actual force of “pure” destruction standing behind him. This is convenient, because it allows the hero to fight all-out without moral qualms.

How does it all end?

Art by コロッケ・オムラシウ

In epic fantasy, a number of endings are possible. The first is the heroic sacrifice — the hero dies, or is otherwise lost to the world, in order to prevent the final victory of evil. This fits very well into the epic hero’s character arc, since he’s gone from being skeptical of his destiny to accepting it over the course of the story, and his self-sacrifice is the ultimate proof of his acceptance.

If he survives, the hero is changed by his experiences. Joseph Campbell says the hero should return home, but not quite the same as when he left, and that fits the epic fantasy hero’s story nicely. Sometimes he retires, concealing his awesome power and leading a quiet life. Other times, he finds that his newfound knowledge and skill makes him fit to rule his people, particularly if his quest involved overthrowing the previous ruler.

The world needs saving, and at the end of the story it’s been saved, leaving the hero with his destiny discharged.

The unifying factor is that there is an ending, because the epic fantasy hero’s goal is externally imposed and quantifiable. The world needs saving, and at the end of the story it’s been saved, leaving the hero with his destiny discharged. The shounen hero, on the other hand, starts with a self-imposed goal, so his ending is a bit more ambiguous. Sometimes he doesn’t get an ending; he may defeat the primary villain, but that doesn’t mean his story doesn’t at least theoretically go on, questing eternally with his companions.

On the other hand, the shounen hero with a specific goal, like “get revenge for my family”, often finds that completing it is unsatisfying. He may conclude that the goal was never worthwhile in the first place, or that his true objective was something else entirely. Many shounen heroes find that their true happiness comes from the friendship of their companions on the journey, so they may decide to extend things and continue onward.

What Does It All Mean?

The details vary, and the plots vary, but these two genres in essence revolve around some very simple themes. At the root, they are both wish-fulfillment fantasies, but they are constructed in slightly different ways.

The epic fantasy embodies the fantasy of being chosen, being special, being unique. The hero is plucked out of his mundane life to do battle on a larger plane; he struggles there, but eventually proves himself worthy of it.

Buy The Shadow Throne by Django Wexler: Book/eBook

The shounen hero, on the other, gives us the fantasy that never giving up, never abandoning a goal, will eventually see us through. His determination and faith in himself is his most important attribute, ultimately more powerful than sword-fighting or martial arts.

The common element, the thing that makes these fantasies so powerful and relevant, is that it’s easy for the audience to place themselves at the fantasy’s heart. Very few of us are the sons of kings, after all, or world-renowned swordsmen. But anyone can be plucked from obscurity by destiny. Similarly, while few of us are expert martial artists, we all would like to believe that, if it really came down to it, we could believe in ourselves and our cause and never give up. This is why the hero rarely has extraordinary skills of his own — it would impede our ability to identify with the character. By keeping the hero’s key characteristics to the intangible, his indomitable will or the hand of fate, the fantasy is preserved, and we’re able to slip ourselves into the central role.

The post “With Fist and Sword: Epic Fantasy and Shounen Anime Heroes” by Django Wexler appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 18, 2014

Cover Art for Gemini Cell by Myke Cole

I’ll admit, this cover is totally against my type, but… I can’t stop drooling over it. It’s aggressive and flashy, more Hollywood than Rivendell, but equally arresting and difficult to ignore. Myke’s had some great covers in the past, and artist Larry Rostant is one of the few photographic illustrators that I trust to work on SF book covers. He’s got another winner here.

US Navy SEAL Jim Schweitzer is a consummate professional, a fierce warrior, and a hard man to kill. But when he sees something he was never meant to see on a covert mission gone bad, he finds himself – and his family – in the crosshairs. Nothing means more to Jim than protecting his loved ones, but when the enemy brings the battle to his front door, he is overwhelmed and taken down. It should be the end of the story. But Jim is raised from the dead by a sorcerer and recruited by a top secret unit dabbling in the occult, known only as the Gemini Cell. With powers he doesn’t understand, Jim is called back to duty – as the ultimate warrior. As he wrestles with a literal inner demon, Jim realises his new superiors are determined to use him for their own ends and keep him in the dark – especially about the fates of his wife and son…

Gemini Cell is the first volume in a new follow-up trilogy to Cole’s popular Shadow Ops series. It will be released on January 27th, 2015 by Ace Books.

The post Cover Art for Gemini Cell by Myke Cole appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

July 14, 2014

“Writing in Ink to Samarkand” by Paul Weimer

You can hear a distant thunder of hoofbeats, steadily growing louder as it approaches. It is a stratum of fantasy that looks beyond the boundary.

You can hear a distant thunder of hoofbeats, steadily growing louder as it approaches. It is a stratum of secondary world fantasy that looks beyond the boundary, the Great Wall of Europe. Secondary world fantasy that is inspired by Byzantium and the Silk Road, all the way to the western borders of China. Characters, landscapes, cultural forms derived from the Abbasid Caliphate, the Taklamakan Desert, and the Empires of Southeast Asia much more than Lancashire.

Thanks to the rising popularity of fantasy fiction, riding, in part, on the wave of Game of Thrones‘ massive success, many of science fiction and fantasy’s old paradigms and forms of have gotten a new look by virtue of new and diverse styles and varieties of stories, new and formerly inhibited voices (primarily women, genderqueer, and minorities), and new or formerly under-utilized wellsprings of inspiration. Elizabeth Bear, one of the many authors at the center of this paradigm shift, calls this “Rainbow SF.” As Science fiction readies its generation ship to move beyond the white-heteronormative-males-conquer-the-galaxy pastiche, popular fantasy is beginning to look beyond the faux-medieval western European that remained so popular throughout the genre’s formative decades. And this doesn’t even include the rise of World SF, as fiction from markets and voices beyond North America and England begin to be heard in the field.

I call such books “Silk Road Fantasy.”

Silk Road Fantasy is hardly a new idea, and can be traced to the works of early 20th century writer Harold Lamb, and even more specifically to Khlit the Wolf, the Cossack, who wanders from China to Russia in the course of his adventures in the 1600s. Stories like “Tal Taluai Khan” set Khilit on the road to adventure, and bring him traveling companions and temporary allies ranging from Afghanistan to China. Most notable of these, Abdul Dost, a Muslim in contrast to Khilit’s Eastern Orthodox Christianity, himself becomes the narrator of several of the stories. Those who champions Lamb’s fiction, like Harold Andrew Jones, have done excellent work in introducing a new generation of readers to these classic, formative novels. However, in my opinion, the real genesis of Silk Road Fantasy as well as the term itself, comes from the works of Susan Shwarz and Judith Tarr.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, Schwarz wrote several series of novels exploring the Silk Road. In the Heirs of Byzantium trilogy, an alternate magical Byzantium is the base setting for intrigue and adventure. Empire of the Eagle follows the imagined adventures of the survivors of the defeated Roman Legions of the battle of Carrhae, sent further and further east, far away from the world they knew. Imperial Lady, co-written with Andre Norton, explores the other end of the Silk Road, featuring a former princess of the Han Court as its protagonist, exiled to the steppes. And, notably, Silk Roads and Shadows, the trope namer, wherein a princess of Byzantium heads east in search of the secret of silk.

As wonderful as their work was, Tarr and Schwarz were among only a few lonely voices in a field not yet ready for exploration.

Judith Tarr’s role skews slightly more historical in flavor than Schwarz, and with slightly different interests and locations, focusing on the diversity of Silk Road Fantasy in terms of geography and ethnogeography, and a strong focus on the Crusades. A Wind in Cairo features a protagonist transformed into a stallion during the wars between Saladin and the Christian Crusaders. Similarly, Alamut (and its sequel The Dagger and the Cross) revolve around a prince of Elfland who gets caught up in events like the battle of Hattin and falls for a deathless fire spirit. The cultures, societies and vistas of her Avaryan novels, too, range from the Mediterranean to Tibet in their inspiration and wellsprings.

However, as wonderful as their work was (and still worth tracking down decades later), Tarr and Schwarz were among only a few lonely voices in a field not yet ready for exploration. The ’80s and ’90s were fascinated with faux-medieval worlds — the Four Lands, Midkemia, Osten Ard, and endless celtic fantasy trilogies — meant that the voices drawing on the Silk Road were few and far between. Drowned out. Nearly forgotten.

In the last few years, with the rise of other diversity in fantasy, Silk Road fantasy has returned to prominence. Among the foremost explorers of this long dormant sub-genre is the aforementioned Elizabeth Bear and the Eternal Sky trilogy. In his review of the first volume, Aidan Moher, editor of A Dribble of Ink, said, “Range of Ghosts is wonderful and compelling, a truly great novel that moves the genre forward by challenging and embracing its history all at once.” Bear brings a stunning variety of cultures, terrain,and indelibly memorable characters to Silk Road Fantasy, illustrating the potential for fantasy liberated from the strict terrestrial and historical influences embraced by a large portion of the genre, and fully embracing the potential for secondary world fantasy.

Art by: Frank Hong | Kyu Seok Choi | Daniel Kvasznicza | Alex Tooth

Elizabeth Bear may be the leading light of Silk Road Fantasy, but many others are beside her as she explores a ethnic and geographical history that remains elusive and unknown to many western readers. Mazarkis Williams’ Tower and Knife trilogy borrows on the Middle East and Central Asia in the sensibilities of the Cerani Empire. K.V. Johansen explores the deep, expansive history and mythology of a world inspired by landscapes and peoples of central Asia and Siberia, complete with a trade road that connects them all. Chris Willrich’s second Gaunt and Bone novel, The Silk Map, takes his heroes west out of a China-like realm onto a Central Asian-like deserts and steppe in a poetically intimate story of family in the midst of looming conflicts and events to shape the future of the world, with magical guardians, trade cities, and and airship flying steppe nomads.

As alluring as the idea of fantasy inspired by lands outside Europe is, there is, as always, the danger of cultural appropriation when dealing with cultures, peoples and societies far outside one’s own. Taking merely a veneer or slapdash borrowing of the hard-won heritage of people with a history and concerns of their own is more than just impolite, it’s a real problem. Just as the ’80s and ’90s had a torrent of fantasy novels whose careless borrowings of Celtic mythology and culture frustrate historians and experts in that field, readers must be wary of encouraging Silk Road Fantasy that uses similar appropriations to give its world and air of mysticism and otherliness. Approached with respect, care and careful research, these settings and histories provide wonderful and fresh things for fantasy.

Buy The Grace of Kings by Ken Liu: Book/eBook

Is Silk Road Fantasy the next big thing? Some upcoming releases certainly indicate that its a booming sub-genre of secondary world fantasy. Ken Liu is publishing his first novel, The Grace of Kings, and Elizabeth Bear is working on three more novels set in her Eternal Sky universe. The vast potential of fantasy’s creative potential, Silk Road Fantasy and beyond, remains full of limitless potential. Consider a sword and sorcery novel set in a city inspired by Samarkand, or a secondary world road trip fantasy novel in the vein of Michael Chabon’s Gentlemen of the Road. How about more novels that are inspired by the Mongols, the Tibetan Empire, the shamans of the Siberian steppe, the Moghuls, and others along the branches of that fabled trade route. I look forward to many other writers exploring the Silk Road, with careful respect and care to the source cultures, and writing in ink to Samarkand.

The post “Writing in Ink to Samarkand” by Paul Weimer appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.