Aidan Moher's Blog, page 23

April 23, 2014

More Details on The Last King of Osten Ard by Tad Williams, including a UK publisher

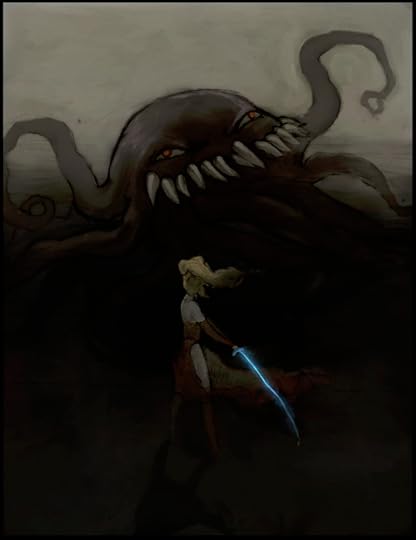

Art by Kerem Beyit

News broke earlier this month that after a 21 year absence, Tad Williams is returning to Osten Ard, the fantastical world that put him on the fantasy map, with The Last King of Osten Ard, a sequel trilogy to his enormously popular and influential epic fantasy, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn.

“I believe I can now write a story worthy of those much-loved settings and characters,” Williams said, explaining the origins of the unlikely sequel. “One that people who haven’t read the originals can enjoy, but which will of course mean more to those who know the original work. More than that, I feel I can do something that will stand up to the best books in our field. I have very high hopes. I’m excited by the challenge. And I’ll do my absolute best to make all the kind responses I’ve already had justified.”

Though the news was released earlier than Williams originally hoped, he’s only a few chapters into writing the first volume, he’s not shy on providing details of what fans can expect from the new trilogy.

“[The Last King of Osten Ard] is going to be at least as bursting-at-the-seams as the first one,” he said. “Since the originals are already written, I’m not going to spend anywhere near so much time setting up the world. Stuff is going to be happening from pretty much go. And one thing I can definitely tell you. LOTS of Norns. A much closer look at the Norns, collectively and individually, then we had in the first books. Much like what we learned of the Sithi in Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn.”

The title of the trilogy already has fans speculating about the fate of the first trilogy’s hero, the kitchen boy, Simon. Williams, however, is coy, and happy to play with those speculating. “You’ve already met the Last King of Osten Ard,” he teased. “If I explain who the king is, you’ll start to get ideas about why that would be the “last king”. So I’m not going in that direction. It’s something that will only become clear in the final volume.”

Williams also addressed Chronicle in Stone, the long-rumoured Osten Ard short story collection. “Most of the ideas that were going to turn into stories (in other words, which were intrinsically interesting in and of themselves) have worked their way into the new books,” he said. “Off the top of my head, I can’t think of any that haven’t. Which doesn’t mean there will never be a Chronicle in Stone, but this will certainly set it back. I still want to use that framing device, though.”

Hodderscape, the official blog of Hodder and Stoughton, announced that they will be bringing Williams’ new trilogy to the UK. From the release, “Hodder and Stoughton have acquired three books that are sequels to the New York Times bestselling sensation of the 1980s and 1990s, the Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn trilogy, which inspired George R R Martin to write A Song of Ice and Fire and launched Christopher Paolini’s writing career.

“The Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn books form some of my fondest memories of publishing,” said Oliver Johnson, Associate Publisher at Hodder and Stoughton. “[They] are as fresh and vibrant today as they were when I came across them in the 80s when I was lucky enough to be working on the Legend imprint which acquired them. So the news of this series seems like a beautiful homecoming to me and all the other fans of that classic series at Hodder.”

Though the UK editions of Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn are published by Orbit Books, Hodder and Stoughton currently publishes Williams’ urban fantasy series, Bobby Dollar. The Last King of Osten Ard will be published by DAW Books in North America. The first volume of the trilogy, The Witchwood Crown is due for release in 2015.

The post More Details on The Last King of Osten Ard by Tad Williams, including a UK publisher appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

April 21, 2014

“Of Better Worlds and Worlds Gone Wrong” by Katherine Addison

I was asked for this post to write about hope in fantasy. And that means I need to talk about grimdark.

I was asked for this post to write about hope in fantasy. And that means I need to talk about grimdark. (Definition from TV Tropes here, for those who need it.) And I need to say, before I start, that I am a practitioner of grimdark; the Doctrine of Labyrinths quartet (Melusine (2005), The Virtu (2006), The Mirador (2007), Corambis (2009)) can be nothing but. So I’m not speaking as someone who abhors grimdark, but as someone who loves it.

One of the things behind grimdark, I think–and it’s not just grimdark, either, but most of Anglophone literature since somewhere around World War I–is a conviction that being pessimistic, tragic, depressing, dark means that a text is more “realistic,” more “serious,” and therefore inherently “better” than it would be if it allowed optimism and hope. I’ll get into the issue of “realism” later, but I want to point out here that tragedy is not inherently “better” as a literary form than comedy and writing a tragedy does not demonstrate greater skill/talent/genius than writing a comedy. (Kind of the reverse, in fact. Comedy is hard.)

Art by David Wenzel

I’m not stumping for Pollyanna-ism. I don’t want to reverse the polarity and insist that sweetness and light is superior to gritty dystopianism. (I like grimdark, remember.) But dystopias that entirely deny the existence of virtues like compassion and altruism (1984, A Clockwork Orange, The Lord of the Flies) may be great literature, and great cautionary tales, but the more we accept and promote them as “more realistic” and “better,” the more we make it likely that they become more accurate mirrors of our species. If nobody models compassion, how is anyone supposed to learn to practice it?

I can feel the word escapism! loitering around the edges of this post and trying to shove its way in

I can feel the word escapism! loitering around the edges of this post and trying to shove its way in, because that is of course the way that followers of “serious,” “realistic” fiction denigrate any suggestion that not everything has to be one dreary disaster after another. Also, of course, escapism! is something that gets yelled at fantasy a lot (like albatross! in the Monty Python sketch) to beat it down and persuade us all that fantasy isn’t important and doesn’t matter, that it’s trivial and childish and unworthy of our attention.

J. R. R. Tolkien and Ursula K. Le Guin, two of the greatest fantasists of the twentieth century, had (have) strong opinions on the subject of escapism, which I’m just going to quote–Tolkien at great length, because he’s STILL NOT WRONG.

Tolkien, in “On Fairy-Stories”: “I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which ‘Escape’ is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds. Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.”

Le Guin, riffing off Tolkien in “Escape Routes”: “If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? The moneylenders, the knownothings, the authoritarians have us all in prison; if we value the freedom of the mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can.”

(Thank you to The Tolkienist for putting these two passages side-by-side.)

Art by Karl Kopinski

Tolkien and Le Guin are arguing that escape means hope, and hope is one of the great virtues of fantasy.

My point, aside from remarking that both Tolkien and Le Guin are arguing that escape means hope, and hope is one of the great virtues of fantasy, is what Tolkien says at the end of the passage: they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter. Because I think that’s exactly it. The denigration of “escapism” comes from an implicit belief that it is brave and necessary and heroic to face “reality,” where “reality” is grim and dark and nihilistic (“solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” as that tremendous pessimist Thomas Hobbes puts it), and that if you turn away from that “reality,” you are a deserter and therefore a coward.

There are a number of fallacies here, as Tolkien notes. One is the claim to the exclusive right to define “reality.” Second, if this is an accurate definition of “reality,” it is a fallacy to believe that it is even possible to desert from the front lines by anything short of suicide. Even if your consumption of fiction takes you away from “reality” for an hour or two, you’re always going to have to come back. Clearly, if we accept this definition of “reality,” “escapism” can only be the most tremendous blessing fiction has to offer.

But going back to that first fallacy . . . “Reality” is not simple to define (as my persistent use of quotes is meant to indicate), and just because a literary movement or several have chosen to privilege and valorize darkness and gritty brutality doesn’t actually mean that that represents “reality” any more than My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic or The Care Bears (that plague of my own childhood) does. (It’s completely unfair to pick animated TV shows for children as examples, since they’re not even pretending to be real, but–I note for the record–they are trying to model virtues like sharing and loyalty and kindness to their small viewers.) Representing reality in fiction is an oxymoron anyway (even though it’s one that I, like many other writers, strive to resolve as best I can in my work); there’s no need to compound the problem by artificially limiting what counts as “reality” and what doesn’t.

Buy The Goblin Emperor by Katharine Addison: Book/eBook

Cynicism is fashionable in the current grimdark era, the attitude that we are too smart to be taken in by idealism. And god knows it’s true that human beings are capable of evil–not only of committing atrocities, but of reifying atrocity into a cultural ethos. (I read a lot about Nazi Germany. Believe me, I have no illusions about human nature.) But human beings are also capable of breathtaking self-sacrifice and compassion and grace, and denying that gives as false a view of human nature as denying our capacity for evil.

And that, I think, is where hope comes in. If we understand “escapism” as the Escape of the Prisoner rather than the Flight of the Deserter, then surely what motivates it, more than anything else, is hope. The hope that the prison is not eternal. The hope of communicating with other prisoners. The hope that if you keep chipping away at the bars long enough, one of them will fall out. And I refuse utterly to classify that hope as weak or foolish.

“No live organism,” Shirley Jackson wrote at the start of The Haunting of Hill House, “can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute realism; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.” Fantasy allows us to dream–both of better worlds and of worlds gone wrong. And we need them both.

The post “Of Better Worlds and Worlds Gone Wrong” by Katherine Addison appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

Official Announcement: A Dribble of Ink nominated for two 2014 Hugo Awards

On Saturday, April 19th, the 2014 Hugo Award nominations were announced, and I’m proud to announce that A Dribble of Ink is represented in two categories: Best Fanzine and Best Related Work.

Best Fanzine

Alongside The Book Smugglers*, Elitist Book Review, Journey Planet and Pornokitsch*, A Dribble of Ink is in the running for Best Fanzine of 2013. If you’ve followed my writing for any time, you’ll know that I’ve long been critical of this category for dipping its pen into the same inkwell too often, so I’m thrilled to be included on a ballot that is guaranteed to see a new winner.

On that note, I expect to get crushed by Pornokitsch and/or The Book Smugglers, but it’ll be fun competition between these friends of mine regardless.

Also on the ballot are A Dribble of Ink’s contributing reviewers: Foz Meadows* (Best Fan Writer) and Justin Landon* (Best Related Work).

*On my nomination ballot

Best Related Work

Kameron Hurley’s epic essay, We Have Always Fought, was an out-of-control avalanche last year. As Hurley described, in her own reaction to the nomination:

We can chomp about the evils of the Internet, and how it’s used to manufacture bullshit messages about oppressing people. But I want you all think about this: “We Have Always Fought” is not about silencing others, telling women to get back into the kitchen, or a piece of Nazi sympathizing.

It’s a post that asks creators – fiction writers, screenwriters, game makers, every creative person telling stories – to rethink the tired old narrative that erases women from history, from the present, from the future. It’s a cry for change, and the resonance it generated within the community shocked me. I don’t have current stats, but six weeks after it came out last year, we were already at 50-70,000 hits. And the vast, vast VAST majority of the responses were overwhelmingly positive.

And when the Hugo nomination came out?

My friends, that shit is making the rounds again.

Can’t stop the fucking signal.

‘We Have Always Fought’ is currently sitting at 150,000+ views, so significantly beyond the numbers that Hurley reported in her post. To my knowledge, this is the first time that an individual blog post has been nominated for a Hugo Award. So, congrats to Hurley for making history.

Congratulations to the other nominees! And thank you to everyone who contributed to A Dribble of Ink in 2013, you make this editor look better than he deserves.

Cheers.

The post Official Announcement: A Dribble of Ink nominated for two 2014 Hugo Awards appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

Official Announcement: A Dribble of Ink nominated for two 2013 Hugo Awards

On Saturday, April 19th, the 2013 Hugo Award nominations were announced, and I’m proud to announce that A Dribble of Ink is represented in two categories: Best Fanzine and Best Related Work.

Best Fanzine

Alongside The Book Smugglers*, Elitist Book Review, Journey Planet and Pornokitsch*, A Dribble of Ink is in the running for Best Fanzine of 2013. If you’ve followed my writing for any time, you’ll know that I’ve long been critical of this category for dipping its pen into the same inkwell too often, so I’m thrilled to be included on a ballot that is guaranteed to see a new winner.

On that note, I expect to get crushed by Pornokitsch and/or The Book Smugglers, but it’ll be fun competition between these friends of mine regardless.

Also on the ballot are A Dribble of Ink’s contributing reviewers: Foz Meadows* (Best Fan Writer) and Justin Landon* (Best Related Work).

*On my nomination ballot

Best Related Work

Kameron Hurley’s epic essay, We Have Always Fought, was an out-of-control avalanche last year. As Hurley described, in her own reaction to the nomination:

We can chomp about the evils of the Internet, and how it’s used to manufacture bullshit messages about oppressing people. But I want you all think about this: “We Have Always Fought” is not about silencing others, telling women to get back into the kitchen, or a piece of Nazi sympathizing.

It’s a post that asks creators – fiction writers, screenwriters, game makers, every creative person telling stories – to rethink the tired old narrative that erases women from history, from the present, from the future. It’s a cry for change, and the resonance it generated within the community shocked me. I don’t have current stats, but six weeks after it came out last year, we were already at 50-70,000 hits. And the vast, vast VAST majority of the responses were overwhelmingly positive.

And when the Hugo nomination came out?

My friends, that shit is making the rounds again.

Can’t stop the fucking signal.

‘We Have Always Fought’ is currently sitting at 150,000+ views, so significantly beyond the numbers that Hurley reported in her post. To my knowledge, this is the first time that an individual blog post has been nominated for a Hugo Award. So, congrats to Hurley for making history.

Congratulations to the other nominees! And thank you to everyone who contributed to A Dribble of Ink in 2013, you make this editor look better than he deserves.

Cheers.

The post Official Announcement: A Dribble of Ink nominated for two 2013 Hugo Awards appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

April 19, 2014

Announcing the 2014 Hugo Award Nominees (guest starring… um, me!)

Via Tor.com, the list of nominees for the 2014 Hugo Award nominees (with added squee!):

2014 Hugo Award nominees

Best Novel (1595 ballots)

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie (Orbit)

Neptune’s Brood by Charles Stross (Ace / Orbit)

Parasite by Mira Grant (Orbit)

Warbound, Book III of the Grimnoir Chronicles by Larry Correia (Baen Books)

The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson (Tor Books)

Best Novella (847 ballots)

The Butcher of Khardov by Dan Wells (Privateer Press)

“The Chaplain’s Legacy” by Brad Torgersen (Analog, Jul-Aug 2013)

“Equoid” by Charles Stross (Tor.com, 09-2013)

Six-Gun Snow White by Catherynne M. Valente (Subterranean Press)

“Wakulla Springs” by Andy Duncan and Ellen Klages (Tor.com, 10-2013)

Best Novelette (728 ballots)

“Opera Vita Aeterna” by Vox Day (The Last Witchking, Marcher Lord Hinterlands)

“The Exchange Officers” by Brad Torgersen (Analog, Jan-Feb 2013)

“The Lady Astronaut of Mars” by Mary Robinette Kowal (Tor.com, 09-2013)

“The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling” by Ted Chiang (Subterranean Press Magazine, Fall 2013)

“The Waiting Stars” by Aliette de Bodard (The Other Half of the Sky, Candlemark & Gleam)

Best Short Story (865 ballots)

“If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love” by Rachel Swirsky (Apex Magazine, Mar-2013)

“The Ink Readers of Doi Saket” by Thomas Olde Heuvelt (Tor.com, 04-2013)

“Selkie Stories Are for Losers” by Sofia Samatar (Strange Horizons, Jan-2013)

“The Water That Falls on You from Nowhere” by John Chu (Tor.com, 02-2013)

Note: category has 4 nominees due to a 5% requirement under Section 3.8.5 of the WSFS constitution.

Best Related Work (752 ballots)

Queers Dig Time Lords: A Celebration of Doctor Who by the LGBTQ Fans Who Love It Edited by Sigrid Ellis & Michael Damien Thomas (Mad Norwegian Press)

Speculative Fiction 2012: The Best Online Reviews, Essays and Commentary by Justin Landon & Jared Shurin (Jurassic London)

We Have Always Fought: Challenging the Women, Cattle and Slaves Narrative by Kameron Hurley (A Dribble of Ink)*

Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction by Jeff VanderMeer, with Jeremy Zerfoss (Abrams Image)

Writing Excuses Season 8 by Brandon Sanderson, Dan Wells, Mary Robinette Kowal, Howard Tayler, Jordan Sanderson

Best Graphic Story (552 ballots)

Girl Genius Vol 13: Agatha Heterodyne & The Sleeping City written by Phil and Kaja Foglio; art by Phil Foglio; colors by Cheyenne Wright (Airship Entertainment)

“The Girl Who Loved Doctor Who” Written by Paul Cornell, Illustrated by Jimmy Broxton (Doctor Who Special 2013, IDW)

The Meathouse Man Adapted from the story by George R.R. Martin and Illustrated by Raya Golden (Jet City Comics)

Saga Vol 2 Written by Brian K. Vaughn, Illustrated by Fiona Staples (Image Comics )

Time by Randall Munroe (XKCD)

Best Dramatic Presentation (Long Form) (995 ballots)

Frozen Screenplay by Jennifer Lee; Directed by Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee (Walt Disney Studios)

Gravity Written by Alfonso Cuarón & Jonás Cuarón; Directed by Alfonso Cuarón (Esperanto Filmoj; Heyday Films; Warner Bros.)

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire Screenplay by Simon Beaufoy & Michael Arndt; Directed by Francis Lawrence (Color Force; Lionsgate)

Iron Man 3 Screenplay by Drew Pearce & Shane Black; Directed by Shane Black (Marvel Studios; DMG Entertainment; Paramount Pictures)

Pacific Rim Screenplay by Travis Beacham & Guillermo del Toro; Directed by Guillermo del Toro (Legendary Pictures, Warner Bros., Disney Double Dare You)

Best Dramatic Presentation (Short Form) (760 ballots)

An Adventure in Space and Time Written by Mark Gatiss; Directed by Terry McDonough (BBC Television)

Doctor Who: “The Day of the Doctor” Written by Steven Moffat, Directed by Nick Hurran (BBC)

Doctor Who: “The Name of the Doctor” Written by Steven Moffat, Directed by Saul Metzstein (BBC)

The Five(ish) Doctors Reboot Written & Directed by Peter Davison (BBC Television)

Game of Thrones: “The Rains of Castamere” Written by David Benioff & D.B. Weiss; Directed by David Nutter (HBO Entertainment)

Orphan Black: “Variations under Domestication” Written by Will Pascoe; Directed by John Fawcett (Temple Street Productions; Space/BBC America)

Note: category has 6 nominees due to a tie for 5th place.

Best Editor – Short Form (656 ballots)

John Joseph Adams

Neil Clarke

Ellen Datlow

Jonathan Strahan

Sheila Williams

Best Editor – Long Form (632 ballots)

Ginjer Buchanan

Sheila Gilbert

Liz Gorinsky

Lee Harris

Toni Weisskopf

Best Professional Artist (624 ballots)

Galen Dara

Julie Dillon

Daniel Dos Santos

John Harris

John Picacio

Fiona Staples

Note: category has 6 nominees due to a tie for 5th place.

Best Semiprozine (411 ballots)

Apex Magazine edited by Lynne M. Thomas, Jason Sizemore and Michael Damian Thomas

Beneath Ceaseless Skies edited by Scott H. Andrews

Interzone edited by Andy Cox

Lightspeed Magazine edited by John Joseph Adams, Rich Horton and Stefan Rudnicki

Strange Horizons edited by Niall Harrison, Brit Mandelo, An Owomoyela, Julia Rios, Sonya Taaffe, Abigail Nussbaum, Rebecca Cross, Anaea Lay and Shane Gavin

Best Fanzine (478 ballots)

The Book Smugglers edited by Ana Grilo and Thea James

A Dribble of Ink edited by Aidan Moher*

Elitist Book Reviews edited by Steven Diamond

Journey Planet edited by James Bacon, Christopher J Garcia, Lynda E. Rucker, Pete Young, Colin Harris and Helen J. Montgomery

Pornokitsch edited by Anne C. Perry and Jared Shurin

Best Fancast (396 ballots)

The Coode Street Podcast, Jonathan Strahan and Gary K. Wolfe

Doctor Who: Verity! Deborah Stanish, Erika Ensign, Katrina Griffiths, L.M. Myles, Lynne M. Thomas and Tansy Rayner Roberts

Galactic Suburbia Podcast, Alisa Krasnostein, Alexandra Pierce, Tansy Rayner Roberts (Presenters) and Andrew Finch (Producer)

SF Signal Podcast, Patrick Hester

The Skiffy and Fanty Show, Shaun Duke, Jen Zink, Julia Rios, Paul Weimer, David Annandale, Mike Underwood and Stina Leicht

Tea and Jeopardy, Emma Newman

The Writer and the Critic, Kirstyn McDermott and Ian Mond

Note: category has 7 nominees due to a tie for 5th place.

Best Fan Writer (521 ballots)

Liz Bourke

Kameron Hurley

Foz Meadows

Abigail Nussbaum

Mark Oshiro

Best Fan Artist (316 ballots)

Brad W. Foster

Mandie Manzano

Spring Schoenhuth

Steve Stiles

Sarah Webb

John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer (767 ballots)

Award for the best new professional science fiction or fantasy writer of 2012 or 2013, sponsored by Dell Magazines (not a Hugo Award).

Wesley Chu

Max Gladstone

Ramez Naam

Sofia Samatar

Benjanun Sriduangkaew

Congrats to all the nominees. Thoughts (many and sundry) to come.

*Um, holy crap.

The post Announcing the 2014 Hugo Award Nominees (guest starring… um, me!) appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

Announcing the 2013 Hugo Award Nominees (guest starring… um, me!)

Via Tor.com, the list of nominees for the 2013 Hugo Award nominees (with added squee!):

2014 Hugo Award nominees

Best Novel (1595 ballots)

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie (Orbit)

Neptune’s Brood by Charles Stross (Ace / Orbit)

Parasite by Mira Grant (Orbit)

Warbound, Book III of the Grimnoir Chronicles by Larry Correia (Baen Books)

The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson (Tor Books)

Best Novella (847 ballots)

The Butcher of Khardov by Dan Wells (Privateer Press)

“The Chaplain’s Legacy” by Brad Torgersen (Analog, Jul-Aug 2013)

“Equoid” by Charles Stross (Tor.com, 09-2013)

Six-Gun Snow White by Catherynne M. Valente (Subterranean Press)

“Wakulla Springs” by Andy Duncan and Ellen Klages (Tor.com, 10-2013)

Best Novelette (728 ballots)

“Opera Vita Aeterna” by Vox Day (The Last Witchking, Marcher Lord Hinterlands)

“The Exchange Officers” by Brad Torgersen (Analog, Jan-Feb 2013)

“The Lady Astronaut of Mars” by Mary Robinette Kowal (Tor.com, 09-2013)

“The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling” by Ted Chiang (Subterranean Press Magazine, Fall 2013)

“The Waiting Stars” by Aliette de Bodard (The Other Half of the Sky, Candlemark & Gleam)

Best Short Story (865 ballots)

“If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love” by Rachel Swirsky (Apex Magazine, Mar-2013)

“The Ink Readers of Doi Saket” by Thomas Olde Heuvelt (Tor.com, 04-2013)

“Selkie Stories Are for Losers” by Sofia Samatar (Strange Horizons, Jan-2013)

“The Water That Falls on You from Nowhere” by John Chu (Tor.com, 02-2013)

Note: category has 4 nominees due to a 5% requirement under Section 3.8.5 of the WSFS constitution.

Best Related Work (752 ballots)

Queers Dig Time Lords: A Celebration of Doctor Who by the LGBTQ Fans Who Love It Edited by Sigrid Ellis & Michael Damien Thomas (Mad Norwegian Press)

Speculative Fiction 2012: The Best Online Reviews, Essays and Commentary by Justin Landon & Jared Shurin (Jurassic London)

We Have Always Fought: Challenging the Women, Cattle and Slaves Narrative by Kameron Hurley (A Dribble of Ink)*

Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction by Jeff VanderMeer, with Jeremy Zerfoss (Abrams Image)

Writing Excuses Season 8 by Brandon Sanderson, Dan Wells, Mary Robinette Kowal, Howard Tayler, Jordan Sanderson

Best Graphic Story (552 ballots)

Girl Genius Vol 13: Agatha Heterodyne & The Sleeping City written by Phil and Kaja Foglio; art by Phil Foglio; colors by Cheyenne Wright (Airship Entertainment)

“The Girl Who Loved Doctor Who” Written by Paul Cornell, Illustrated by Jimmy Broxton (Doctor Who Special 2013, IDW)

The Meathouse Man Adapted from the story by George R.R. Martin and Illustrated by Raya Golden (Jet City Comics)

Saga Vol 2 Written by Brian K. Vaughn, Illustrated by Fiona Staples (Image Comics )

Time by Randall Munroe (XKCD)

Best Dramatic Presentation (Long Form) (995 ballots)

Frozen Screenplay by Jennifer Lee; Directed by Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee (Walt Disney Studios)

Gravity Written by Alfonso Cuarón & Jonás Cuarón; Directed by Alfonso Cuarón (Esperanto Filmoj; Heyday Films; Warner Bros.)

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire Screenplay by Simon Beaufoy & Michael Arndt; Directed by Francis Lawrence (Color Force; Lionsgate)

Iron Man 3 Screenplay by Drew Pearce & Shane Black; Directed by Shane Black (Marvel Studios; DMG Entertainment; Paramount Pictures)

Pacific Rim Screenplay by Travis Beacham & Guillermo del Toro; Directed by Guillermo del Toro (Legendary Pictures, Warner Bros., Disney Double Dare You)

Best Dramatic Presentation (Short Form) (760 ballots)

An Adventure in Space and Time Written by Mark Gatiss; Directed by Terry McDonough (BBC Television)

Doctor Who: “The Day of the Doctor” Written by Steven Moffat, Directed by Nick Hurran (BBC)

Doctor Who: “The Name of the Doctor” Written by Steven Moffat, Directed by Saul Metzstein (BBC)

The Five(ish) Doctors Reboot Written & Directed by Peter Davison (BBC Television)

Game of Thrones: “The Rains of Castamere” Written by David Benioff & D.B. Weiss; Directed by David Nutter (HBO Entertainment)

Orphan Black: “Variations under Domestication” Written by Will Pascoe; Directed by John Fawcett (Temple Street Productions; Space/BBC America)

Note: category has 6 nominees due to a tie for 5th place.

Best Editor – Short Form (656 ballots)

John Joseph Adams

Neil Clarke

Ellen Datlow

Jonathan Strahan

Sheila Williams

Best Editor – Long Form (632 ballots)

Ginjer Buchanan

Sheila Gilbert

Liz Gorinsky

Lee Harris

Toni Weisskopf

Best Professional Artist (624 ballots)

Galen Dara

Julie Dillon

Daniel Dos Santos

John Harris

John Picacio

Fiona Staples

Note: category has 6 nominees due to a tie for 5th place.

Best Semiprozine (411 ballots)

Apex Magazine edited by Lynne M. Thomas, Jason Sizemore and Michael Damian Thomas

Beneath Ceaseless Skies edited by Scott H. Andrews

Interzone edited by Andy Cox

Lightspeed Magazine edited by John Joseph Adams, Rich Horton and Stefan Rudnicki

Strange Horizons edited by Niall Harrison, Brit Mandelo, An Owomoyela, Julia Rios, Sonya Taaffe, Abigail Nussbaum, Rebecca Cross, Anaea Lay and Shane Gavin

Best Fanzine (478 ballots)

The Book Smugglers edited by Ana Grilo and Thea James

A Dribble of Ink edited by Aidan Moher*

Elitist Book Reviews edited by Steven Diamond

Journey Planet edited by James Bacon, Christopher J Garcia, Lynda E. Rucker, Pete Young, Colin Harris and Helen J. Montgomery

Pornokitsch edited by Anne C. Perry and Jared Shurin

Best Fancast (396 ballots)

The Coode Street Podcast, Jonathan Strahan and Gary K. Wolfe

Doctor Who: Verity! Deborah Stanish, Erika Ensign, Katrina Griffiths, L.M. Myles, Lynne M. Thomas and Tansy Rayner Roberts

Galactic Suburbia Podcast, Alisa Krasnostein, Alexandra Pierce, Tansy Rayner Roberts (Presenters) and Andrew Finch (Producer)

SF Signal Podcast, Patrick Hester

The Skiffy and Fanty Show, Shaun Duke, Jen Zink, Julia Rios, Paul Weimer, David Annandale, Mike Underwood and Stina Leicht

Tea and Jeopardy, Emma Newman

The Writer and the Critic, Kirstyn McDermott and Ian Mond

Note: category has 7 nominees due to a tie for 5th place.

Best Fan Writer (521 ballots)

Liz Bourke

Kameron Hurley

Foz Meadows

Abigail Nussbaum

Mark Oshiro

Best Fan Artist (316 ballots)

Brad W. Foster

Mandie Manzano

Spring Schoenhuth

Steve Stiles

Sarah Webb

John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer (767 ballots)

Award for the best new professional science fiction or fantasy writer of 2012 or 2013, sponsored by Dell Magazines (not a Hugo Award).

Wesley Chu

Max Gladstone

Ramez Naam

Sofia Samatar

Benjanun Sriduangkaew

Congrats to all the nominees. Thoughts (many and sundry) to come.

*Um, holy crap.

The post Announcing the 2013 Hugo Award Nominees (guest starring… um, me!) appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

April 16, 2014

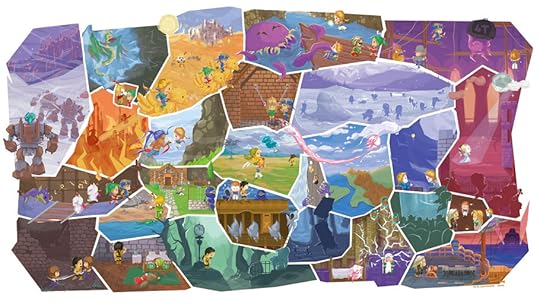

“Life… Dreams… Hope… Where do they come from?” – A Final Fantasy VI Retrospective

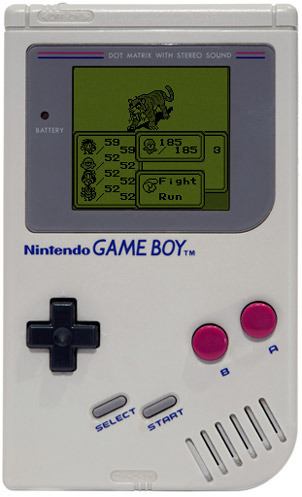

I still remember the first time that I saw a Japanese Roleplaying Game (JRPG). Like many people of my generation, it was a Final Fantasy game, though not one so obvious as Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy VI (or Final Fantasy 3, if you’re familiar with the North American naming scheme), or Final Fantasy VII. No, it was Final Fantasy Legend II in all of its monochromatic glory on the Nintendo Game Boy.

I was at a friend’s house, and his cousin was also visiting. I’d never met the cousin, but he had a Game Boy (like me), so I liked him almost instantly. But, where I was eradicating (or, more accurately, being eradicated by) the Footclan in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or dodging winged-Moai statues in Super Mario Land, he had this slow, boardgame-like game, with numbers, equipment, a map, and so many other elements that I was unfamiliar with. In particular, I remember a fight with a tiger. The one pictured here, in fact. As I think back on it, I can only assume that it’s a low level enemy, fought in one of the early game environments. At the time, however, it was something different. Something frightening.

If you do your homework, however, you’ll quickly discover that my first experience with Final Fantasy was, in fact, not with Final Fantasy at all, but with Akitoshi Kawazu’s infamous SaGa series. See, when Square the developer of the Final Fantasy series, wanted to bring over Kawazu’s zany Makai Toushi SaGa, the first in the SaGa series, to North American shores, they decided that it made more sense to release the title under a respected and successful brand, Final Fantasy, rather than attempting to sell something new. It was the right decision. Final Fantasy Legend II became Square’s first million-selling product.

My parents did the only thing they could: hired a cool, sixteen year-old babysitter. One evening, he brought over a copy of Final Fantasy VI.

At that point most of my roleplaying happened in my head, the sandpile in my backyard, or the forests surrounding my home. I didn’t have even the faintest understanding of numbers-based roleplaying—of dice hit, defense, or THAC0. Swing stick, beat bad guy—those were my rules. The rules of the fantasy worlds I played in bent to will. Final Fantasy Legend 2 wanted me to do math.

So, though my curiosity was piqued momentarily on that day at my friend’s house, I went back to playing character platformers and their instant satisfaction. I returned to adventuring through jungles, battling pirates, and exploring the cold depths of space, all in the safety of my backyard with my friends and brothers.

For a number of years after that, I forgot about Kawazu’s strange game, and the name Final Fantasy faded into a hazy memory. Until one evening…

Like any family of three young boys, my brothers and I were quite a handful. As the oldest, a ripe eleven years old, I led the charge. Vivid memories still fill my head of the time we were climbing up-and-down the ladder-like sides of a bookshelf in my living room, only to bring it crashing down to the floor, barely avoiding being crushed (and further embarrassment for my mother’s friend, who was babysitting.) After that incident, attempting to wrangle up three rambunctious boys, my parents did the only thing they could: hired a sixteen year-old dude with an SNES.

One evening, he brought over a copy of Final Fantasy VI.

Early in Final Fantasy VI, Locke and Terra escape their pursuers by fleeing through the Narshe Mines. Watching my babysitter play through this scene — crawling through the dank mines, Nobuo Uematsu’s haunting music filling our living room — my imagination soared. Enemies around every corner, a labyrinth before us. I still remember the wave of relief I felt when we found the first save point, the screen flashing bright as we stepped onto the safe haven. Then, a tent, where we rested for the night, restoring hit points, and giving us a fighting chance through the rest of the mines.

Like no game before it, Final Fantasy VI helped me to realize that videogames were not limited to diversionary tests of hand-eye coordination and patience, but could also be portals to smaller universes — other worlds as vibrant and exciting as my favourite books.

Graphics

While the complexity of Final Fantasy VI‘s graphics would later be trumped by titles like Chrono Trigger and Star Ocean, at the time of its release, there was little on the market that managed to capture its atmosphere and mise en scène. There were many titles that accurately reflected traditional Dungeons & Dragons-esque fantasy worlds, but Final Fantasy VI‘s steampunk world was a breath of fresh air for the RPG genre.

The squished spritework characters couldn’t capture the full beauty of Yoshitaka Amano’s concept art, and clashed with the more faithful, but static, enemy portraits, but they also gave the series a charm and immense sense of character above and beyond even past Final Fantasy titles.

Creative Limitations

Looking back on development of Final Fantasy VI, co-writer/director Yoshinori Kitase said, “I supposed that action games, for example, relied on sense and instinct while RPGs appealed more to reason and logic.”

Final Fantasy VI was Kitase’s first opportunity to head Square’s mainline franchise, and his enthusiasm shows in all of its loving touches and commitment to the ideals that ensured that the game would not only be successful at the time of its release, but be considered a genre classic in the years to come.

“It’s maybe strange to say [this], but I miss the limitations of making games in those days,” Kitase acknowledged. “The cartridge capacity was so much smaller, of course, and therefore the challenges were that much greater. But nowadays you can do almost anything in a game. It’s a paradox, but this can be more creatively limiting than having hard technical limitations to work within. There is a certain freedom to be found in working within strict boundaries, one clearly evident in Final Fantasy VI.”

Those limitations, and the freedoms that Kitase attrubutes to them, had a profound impact on creating the passion-filled sixth entry in the series, and none moreso than the remarkable fact that development of Final Fantasy VI took only a year. By contrast, development of Final Fantasy XIII took five years. Conceptual design began immediately after the release of Final Fantasy V in December 1992, and production/development of the game occurred during 1993. Final Fantsy VI was released in Japan on April 2nd, 1994, just 16 months after the creators sat down to begin sketching their first ideas on paper.

“It was a hybrid process,” explained Kitase. “[Hironobu] Sakaguchi came up with the story premise, based on a conflict with imperial forces. As the game’s framework was designed to provide leading roles to all the characters in the game, everyone on the team came up with ideas for character episodes.”

It was a truly collaborative effort, as Kitase is quick to point out. “I can’t say that I conceived the complete story,” he told Edge Magazine. “Locke and Terra, for example, are greatly coloured by Sakaguchi’s influence. Meanwhile, the background and in-game episodes for Shadow and Setzer were mainly devised by Tetsuya Nomura, while Kaori Tanaka provided suggestions for Edgar and Sabin, among others. I devoted my time and effort to creating Celes and Gau.”

“Celes, child… You alone are special. Why don’t I give you and Kefka the task of creating progeny to populate my new Magitek Empire?”

- Emperor Gestahl

The Women of FFVI

At that time, JRPGs, at least those that made it to North American shores, lacked the emotional sophistication of even the most rudimentary novels. Even the Final Fantasy series was filled with stock storylines, puddle-deep character relationships, and dialogue that did no favours to anyone. Final Fantasy VI isn’t perfect in this regard, but at the time, Hironobu Sakaguchi and Yoshinori Kitase’s story, along with Ted Woolsey’s (doomed form the get-go, but) competent translation, opened up a grim world full of adult themes and situation, such as genocide, the effects of colonialism, and suicide. On top of this, the Steampunk aesthetic was a kick in the pants for a genre that spent (and still spends) too much time emulating juvenile Dungeons & Dragons campaigns.

At the emotional core of Final Fantasy VI are two women: Terra Branford and Celes Chere.

Final Fantasy VI was a step ahead of the genre, and, frankly, the popular fantasy genre in its entirety, by framing its narrative around two women. And not just female characters as voiceless avatars for the player, but genuinely powerful and authoritative women around whom the world is shaped. Celes is a high-ranking and powerful general in the Gestahlian Empire, and Terra is the Empire’s greatest weapon. Together, they have the power to reshape the world.

Throughout the game’s narrative, layers are peeled back from each of their respective lives and it becomes evident that in the hands of the Gestahlian Empire, the two women, from two very different origins, suffer under similar threats and expectations from those they have grown up with and lived beside their entire lives. Two powerful women, one naturally gifted with magic, the other imbued with the power through Gestahl’s ghastly exploitation of Esper magic, are both trapped by circumstance and the lies that surround them. This theme of captivity runs in parallel through the storyline of both women, and they each find their own method for coping with the trauma that they have faced, and the conflicts they must overcome.

Art by じゅ

Born to a human mother, Madonna, and an Esper father, Maduin, Terra Branford is both a symbol for the conflict between the two races, and the lynchpin of Emperor Gestahl’s war, and Kefka’s subsequent reign. Snatched from her mother’s arms as a child, and endowed with a gift for magic not seen since the War of the Magi, Terra is raised by Gestahl to serve as an obedient and deadly weapon.

As the Final Fantasy series is wont to do, players are introduced to Terra as a amnesiac protagonist, her memory stolen by the slave crown she wears on her brow. Final Fantasy VI begins with Terra on a mission outside of Narshe, a neutral coal mining community, where, alongside two other imperial soldiers, Biggs and Wedge, she is ordered to find Tritoch, a frozen esper. Gestahl hopes to abuse the power of the espers, and regain a magic that has been missing from the world for a millennium. Against her will, Terra leads an assault on the innocent citizens in Narshe, running them down and killing them for no other reason than that stand between her and the esper. By placing the player in control of Terra as she does these horrible things, Final Fantasy VI immediately engaged with the player’s sense of revulsion and self-preservation. Even as Terra is discovering the truth about herself, about the horrors that she has committed, the player themselves want to be distanced from their own actions early in the game, a parallel of emotions that has helped Terra Branford to become one of the most beloved characters among Final Fantasy fans.

While Terra loses her memory, a mechanism in part to defend herself against the travesties of her past, Celes carries the weight of her actions openly, fresh scars visible to all. Celes must make a conscious decision early in Final Fantasy VI to cast aside her people, the safety of her authority, and join her enemies, a mercenary group called the Returners. Proud and cunning, Celes’s power comes from her ability to adapt, to funnel her passion and belief into a perseverance that symbolizes the Returners’ ideals.

Celes’s strength is challenged in one of the 16-bit era’s most surprising and emotionally nuanced moments: her suicide. Midway through Final Fantasy VI, Celes becomes stranded on a small island with Cid, another member of the Gestahlian Empire, and one of the few to show kindness to the espers. The world around them is dying, the result of Kefka’s actions when he usurped power from Emperor Gestahl and threw the World of Balance into ruin. Cid falls ill, and it is up to Celes (and, by proxy, the player) to keep him alive. While it’s possible to keep Cid alive by feeding him only healthy fish, with no instructions (or GameFAQs), it was almost impossible for gamers to know this on their first play through of the game. When Cid passes away from his illness, Celes, overcome with grief, throws herself from the island’s highest peak.

She wakes, miraculously alive, and, as if a message from god, finds a wounded bird wrapped in a bandana much like one that belonged to her lover, Locke. With it, she again finds her strength, and the will to push forward and reunite with her friends. Without her perseverance, there’s little doubt that Kefka would stand unopposed on his throne atop the world.

God of Power

Several hours into Final Fantasy VI, Kefka succeeds in his plans to usurp control over his empire, break the alignment of the Warring Triad, and rain destruction down on the world. Many RPG villains seek to change the world, to, in their own eyes, create a world better than what currently exists. They lust for power, to right a wrong done to them, or to redraw existence as they choose. Kefka’s ambitions, however, are a more terrifying smorgasbord: chaos, ruin, and discord.

A Gestahlian general, and the first experimental Magitek Knight, Kefka’s history and storyline hold many parallels to Celes and Terra, making for the perfect symbolic villain as the two women seek to overcome their external and internal challenges. Unbalanced in mind, Kefka strives to see a similarly unsettled world, and his jester-like makeup and attire embody the ideals that drive his ambitions. Adage tells us that everybody is the hero in their own mind’s eye, yet Kefka is the exception that proves the rule. He’s no hero, even in his own mind.

There are hints that Kefka was once a sane and respected general in the Gestahlian army. By the time of Final Fantasy VI, however, his capacity for human empathy is gone, replaced by a socio- and psychopathic desire to demonstrate his power through the destruction of everything weak and hopeful. As he poisons the water supply of a nearby kingdom, Kefka is easy to loathe. He is terrifying for his lack of remorse — the complete and utter absence of empathy. He cackles with delight as the water turns purple, and it’s at that moment that the player recognizes that there is no hope for Kefka. He must be destroyed.

Art by 網干

World in Ruins

At a point in the game when most JRPGs have the player traipsing through caves, Final Fantasy VI pits them against the apocalypse.

Think about that for a moment. The world is destroyed. At a point in the game when most JRPGs have the player traipsing through caves, sneaking into castles, and fighting rats, Final Fantasy VI pits them against a remorseless enemy who succeeds in bring about the apocalypse. It’s not pre-apocalyptic, or post-apocalyptic, it’s the end of the world in real time. So much of the early game is spent building belief in the vision of the Returners, a vigilante group that is set on bringing down Gestahl’s empire, that the pain and disbelief is palpable when Kefka, not Gestahl, is revealed to be the true antagonist.

At the time of Final Fantasy VI‘s release, few games had the courage and foresight to so dramatically subvert players’ expectations. We’re a merry gang of heroes, right? Sure, things will go wrong, but we’re out to save the day, to stop the bad guys. Nope. Full stop. You’re wrong. A year passes in the game, then, after the Floating Continent has crashed into the sea, the World of Balance has been upset by ruin, you’re back at square one: a single character, no party, no airship.

Every legendary story has the single moment when the reader/viewer/player realizes that they’re participating in something special, something beyond the bounds of the average. From George R.R. Martin’s Red Wedding, to Frodo’s claiming of the Ring, to Rosebud, that moment transcends the medium and cements itself in the participant’s memory, never to be forgotten, with a feeling never to be recaptured. Kefka’s triumph is the moment when Final Fantasy VI goes from being an interesting, progressive mid-90s JRPG, to one of the most iconic and important videogames of the decade. Since then, videogames have grown up, and shocking twists aren’t quite so unexpected anymore, but at the time, the courage of Sakaguchi and Kitase was unprecedented.

“Perhaps you’ve heard this story? Once, when people were pure and innocent, there was a box they were told never to open. But one man went and opened it anyway. He unleashed all the evils of the world: envy… greed… pride… violence… control… All that was left in the box was a single ray of light: Hope.”

- Banon

Art by Elaine Ho

The Music

It’s impossible to discuss Final Fantasy VI without reflecting on its groundbreaking score by Nobuo Uematsu. Final Fantasy VI‘s iconic tracks, such as Terra, The Day After, and the Opera Scene, Aria de Mezzo Caraterre, whose melody and digitized vocals are imprinted forever into videogame canon, established Uematsu as a legend. Many would argue that he has never matched the near-perfection of Final Fantasy VI‘s score, even 20 years later.

http://aidanmoher.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/01-Terra.mp3

“If you look at the songs in Final Fantasy, a lot of them have a very gentle, soothing, kind melody,” Uematsu told 1UP.com in a 2012 interview. “Usually, in the music for towns, if there’s a girl character, you’d have really gentle, kind music. I wanted to make music that had that kind of melody to it.”

A Cast of Thousands

Beyond the three standouts, Final Fantasy VI offered a diverse and interesting cast of characters, both playable and not playable. Ask any player who their favourite character was, or which four comprised the perfect party (Locke, Celes, Terra, Edgar, thank you very much), and you’ll get a different answer every time. While future RPGs, such as the Suikoden series, would usurp Final Fantasy VI‘s throne in terms of playable party members (Suikoden features 101 recruitable characters), there’s a balance to Final Fantasy VI‘s party that ensures each playthrough is unique. No character is wasted, everyone has the potential to be a valuable party member.

Coming off of Final Fantasy V, which featured a robust and a nearly unrivalled job system, which allowed the player to customize their party of four in hundreds of unique combinations, Final Fantasy VI reduced the system complexity by creating the esper system, which allowed characters to equip magical shards that taught them magic spells and provided a unique bonuse to certain statistics when they levelled up. In addition to the esper system, each playable character had their own special ability: Sabin’s Blitz mimicked the martial arts and complex button sequences of arcade fighters, Cyan’s Bushido rewarded player patience, Celes’ Runic put players one step ahead of their opponent’s magic spells, and Gau’s Rage could mimic the attack of nearly any enemy in the game.

All of a sudden, players were able to form a party that was unique to their play-style, but also ensured that every character was powerful across the board. Sabin, for instance, is a martial arts master, and has a bodybuilder’s physique, but intrepid and creative players discovered that he made a great healing and support mage, thanks to his high speed and resiliency. The freedom afforded by this enormous cast of interesting characters ensured that there was a little bit of something for everyone. Trading stories on the playground, every kid had a different argument about how their unique mix of characters was the one to beat.

In addition to their unique abilities in battle, all of the fourteen playable characters, along with many of the non-playable characters, had rich backstories and side-quests that encouraged players to dig into their history and discover more about the various interlinking relationships that brought everyone to the Returners’ cause.

“The idea was to transform the Final Fantasy characters of the time from mere ciphers for fighting into true characters with substance and backstories who could evoke more interesting or complex feelings in the player,” said Kitase. “Since the scale of each character’s individual story was expanding, I began linking this to the concept of different dramas developing, according to the player’s choice of character in the game.”

“Maintaining a careful equilibrium between all the characters was probably the greatest challenge I faced,” he continued. “However, I ended up so involved with each personality while scripting the scenarios that there were points where, looking back at the game today, it’s clear that I somewhat lost this balance. For example, as the scenes featuring Celes and Kefka progress, these characters (while not directly playable in the game) became far greater and more influential than originally intended when development began.”

Like any great story, Final Fantasy VI grew in its telling, and Kitase was unable to ignore the gravitas of the game’s greatest characters.

It’s going to make me sound like an old man, but the whole package of FFVI was just so startling to me, as a console gamer in 1994. Here was a game that opened like a movie, slowly and dramatically, actually rolling credits over a stylized introductory sequence. The frozen wasteland, the Yoshitaka Amano aesthetic, the Nobuo Uematsu score… right from the start, this was a game that proclaimed its own hugeness, its ambition and scope. The SNES had had three years to mature as a platform, and the artists and programmers on FFVI seized every scrap of potential the system had and brought it to the fore. It looked, sounded, and played like nothing else available at the time.

Here was a game about the blending of magic and technology, about the justice and injustice of empires, about preventable apocalypse, about love and loss and rebuilding from the ashes of former lives. Here was a game where your characters actually lost the goddamn war halfway through the play experience, and kept fighting in a vastly changed world. A game with magic airships and mecha. A game with an opera interlude! I still love it, twenty years on, and I’ll keep homaging it until someone casts Ultima on me.

- Scott Lynch, author of The Lies of Locke Lamora

Fun Fact: Scott Lynch named Locke Lamora after Final Fantasy VI‘s ubiquitous treasure hunter: Locke Cole.

Art by Nick Black

Full Bloom

Final Fantasy VII, released three years after Final Fantasy VI changed the landscape of gaming. Like an earthquake of unimaginable magnitude, Cloud Strife and his misfit band of revolutionaries took the groundwork laid by its predecessors and, through sheer cinematic indulgence and grandiosity, opened the world of JRPGs to the masses.

Final Fantasy VI established a lot of the new traditions that would define the Final Fantasy series through the late ’90s and into the early ’00s, including darker narratives, morally ambiguous characters, sci-fi/steampunk aesthetics, and, perhaps most importantly, the first signs of the cinematic storytelling methods that would help Final Fantasy VII turn the industry on its head in 1997.

One has to look only so far as the Opera Scene, famous among gamers and Final Fantasy fans for its iconic music and unique place in the series’ history, to see the first signs of this change. All of the Final Fantasy instalments before Final Fantasy VI were full of dramatic plot points: heroic sacrifices, personal triumphs, feats of strength and perseverance. In so many ways, those narratives were the perfect culmination of imaginary childhood adventures. Elves and dwarves, evil to banish, and squeaky-clean kingdoms to save. Final Fantasy VI was dirty and unpredictable, and the Opera Scene asked players to take a step back, and recognize that even during those dire times, there was some hope, some beauty still left in the crumbling world. The Opera Scene wasn’t powerful for its bravado, but for its delicacy and tenderness. For a generation of gamers accustomed to blasting away enemies with their BFG 9000s, Final Fantasy VI captured minds and hearts with a Disney-esque musical interlude.

Such storytelling techniques were abused to great effect in the following entries in the franchise — big, dramatic CGI cutscenes interrupting gameplay with (at the time) mind-blowing action scenes that helped pull the gamer into the game world in a way that static text and small, barely animated sprites never could. There’s a scene in Final Fantasy VII that features Cloud, the spiky-haired protagonist, riding a motor cycle down a set of a stairs. I remember exclaiming to my friend that that was the pinnacle of videogames, graphics could get no better. (I was 14 years old, it was cool, okay?) But, hindsight being 20/20, I now look back on that scene and laugh, realizing that Square was never able to recapture the naive creativity that led to the Opera Scene.

Art by Carlos F. Villa

Final Fantasy VI set the groundwork for the cinematic future of Final Fantasy games, but later entries in the series, especially the most recent, like the lamentable Final Fantasy XIII, seem to have forgotten so much of what made the final 16-bit entry so timeless. Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy VIII continued with the tradition of establishing an interesting world where fantasy clashes with modern technology, but they both faced issues that seemed to grow out of Square’s inability to balance ambition with solid game design and storytelling. Final Fantasy VII was bogged down by a near incomprehensible translation, and graphics that lacked the innate charm of its predecessor. Final Fantasy VIII featured contemptible characters, and introduced players to the Draw system, which relied on too much repetitive grinding and lacked the simple elegance of the Esper and Materia systems before it. Even Final Fantasy IX, a personal favourite, and clear homage to Final Fantasy games of past, tossed away the blazing-fast battle system from Final Fantasy VI for a slower experience, and forced players through most of the game with a set group of characters, each strictly adhering to a particular class archetype.

The Final Fantasy series is rightfully lauded for its courage to experiment and evolve its formula from entry-to-entry. However, this innovation must be practiced carefully, as too much experiment, not properly weighed against fan expectations, have been damaging to the series. At their core, each game in the series features familiar concepts, such as world elements (moogles, cactuars, summonable eidolons/espers), characters (most notably, Cid), themes (magic vs. science, imperialism, human purity), and naming conventions (for magic spells, abilities, etc.). These elements, along with the series’ recognizable visual identity, help gamers, both committed and casual fans, identify the series and feel comfortable with each new entry. Striking this balance between established traditions and trailblazing concepts helped to keep the series fresh for nearly two decades. However, in recent years, with the release of both Final Fantasy XIII and Final Fantasy XIV, there is worry among critics and fans that Square Enix has forgotten or lost the ability to understand what made their earlier games so successful and enduring.

Art by Mikaël Aguirre

“What made the Final Fantasy series so innovative was the emotion realised from drama within the game in addition to those other elements,” said Kitase.

In the two decades since its release, Final Fantasy VI has remained one of the most beloved and universally praised videogames among fans of all ages. For those who discovered it upon its release, it is a nostalgic reminder of a time when passion filled the industry, and the JRPG genre was still ripe with potential and full of brave new adventures and ideas (and not yet weighed down by corporate expectation and pressure). For those who discovered it through re-releases, from the PlayStation, to the Gameboy Advance or, *shudder*, the iOS and Android versions, it has become a beacon of the heights that videogames can reach when they push through hardware limitations, and fuel development with thoughtful innovation.

“What made the Final Fantasy series so innovative was the emotion realized from drama within the game in addition to those other elements,” said Kitase, thinking back on the early days of the series. “I believe this innovation was more apparent than ever before in the sixth game. This game really brought that creative goal into full bloom.”

For twenty years, we’ve plumbed its depth, and for twenty years the hard-fought adventure of Terra, Celes, and Locke, and the terrifying behaviour Kefka has won our hearts and proven that some things only grow finer with age.

Fin.

The post “Life… Dreams… Hope… Where do they come from?” – A Final Fantasy VI Retrospective appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

April 15, 2014

Welcome to the new A Dribble of Ink!

As you’ve no doubt noticed, things look a little different around here today.

For the past several weeks, I’ve been hard at work designing, developing, and building a brand new look and feel for A Dribble of Ink. 2014 promises a big transitional year for me, both personally and here at A Dribble of Ink, and I felt like there was no better way to celebrate that than to apply a fresh coat of paint, introduce some features I’ve been excited about, and, generally, increase the level of the site to bring it a few steps closer to the vision I have for it moving forward.

I think this is the best, cleanest, and most professional iteration of A Dribble of Ink yet, and hope that it encourages you to visit more often, join the conversation, and spread word to your friends, families, co-workers (and anyone else you chat to about science fiction and fantasy.)

In addition to the visual overhaul, there are a couple of things that I’d like to draw attention to.

Julie Dillon’s Header Artwork

I approached Hugo Award-nominated artist Julie Dillon with a hope, a prayer, and an idea. It’s no secret that I’m an enormous fan of her work, so when she agreed to provide artwork for the new design, I was through the roof. When she provided me with the final version, I was floored.

Artwork by Julie Dillon

Julie’s evocative use of colour brings life and magic to the site, and perfectly capture what I first envisioned when I named the site, nearly seven years ago. I’m a lucky editor.

For a little fun, click the small arrow icon in the header to see Julie’s beautiful work in full.

Advertising

Advertising has come to A Dribble of Ink.

When this site first began life as a pet project, I had little inclination to try to make money off of it. In the intervening years, however, the site has grown larger than I’d ever imagined and takes more of my time than is probably healthy. This advertising opportunity is a move to help me transition A Dribble of Ink from a hobby, to a part of my career. In terms of traffic and presence, A Dribble of Ink is comparable to many popular online magazines, such as Clarkesworld and Lightspeed, and this change will allow some freedoms that did not exist before.

It’s important for me to note that I will be curating the advertising that appears on A Dribble of Ink, rather than using ad services that manage advertising without my direct control. I want to advertise products/services that I feel are relevant and desirable to my audience, ads that I think they will actually click on, rather than gloss over.

If you’re interested in advertising on A Dribble of Ink, you can find all the information you need on the new Advertise page.

Feedback

As always with these redesigns, I’d love to hear your feedback in the comments below. Creating a well-running, beautiful site is always a moving target, so I’m interested in friendly and thoughtful feedback from all of you readers.

And now, onwards!

The post Welcome to the new A Dribble of Ink! appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

April 14, 2014

“Unconventional Publishing” by Michael J. Sullivan

If it wasn’t for unconventional publishing, that would have been the end of the road for Hollow World.

Publishing today is a complicated business full of many options and proponents on different sides vocalizing their path is “the right one” with full-throated conviction. For the record, I see the advantages (and disadvantages) of each. I also don’t think there is a “universal right choice,” just a choice that is going to best fit on an author by author basis.

Currently I’m a ‘hybrid author‘ because I have works available both through self-publishing and traditional routes. What’s more, my traditional routes include both big-five and small presses and there is a world of difference between them.

I think Hollow World, my latest novel, was probably produced in one of the most unconventional ways possible. First it was submitted to my publisher, Orbit. My editor loved the book, but the marketing department didn’t. They need to focus on what sells (and I don’t begrudge this mindset) and currently they think that means military science-fiction and space operas. A classic-style, social science fiction novel such as those written by Asimov or Wells just didn’t fit the bill.

If it wasn’t for unconventional publishing, that would have been the end of the road for Hollow World, and I know far too many authors who have shelved books because they couldn’t get them picked up (or were offered too little). But from past experience, I knew a closed door just means I should look around for an open window.

Art by Marc Simonetti

The first step was Kickstarter.

The first step was Kickstarter. It was my wife’s idea, and for the most part done as an experiment. We saw some promising results from authors such as Chuck Wendig, Tobias Buckell, Bradley P. Beaulieu, and Matt Forbeck, but for the most part few authors give this try, which is a shame.

Since Hollow World, would signal my return to self-publishing it was essential that it was indistinguishable from my traditionally published works. This meant using the same editors and cover designers used by the big-five. For cover, I selected Marc Simonetti, who has done such wonderful work for my French editions of The Riyria Revelations as well as amazing artwork for Patrick Rothfuss’s French edition of his Kingkiller Chronicles, and George R.R. Martin’s Mexican edition of Game of Thrones. Betsy Mitchell, would do the structural editing. She was editor-in-chief at Del Rey for over a decade and has edited hundreds of books over the years. For copy editors I picked two people. The first has two master’s degrees in writing, and has been nominated for multiple awards. The second worked on several New York Times bestsellers, and both came highly recommended. These people are exceptional, but not cheap. And I figured it would cost me about $6,000 to employ them. With that in mind I set my Kickstarter at $3,000 figuring I would contribute half and hope that my backers would kick in the other half. I was wrong. By the time all was said and done (a number of people funded after the Kickstarter ended) I raised $32,000.

Somewhere along the way, there was some confusion between me and my agent, and they submitted the book to another publisher. They also loved the story, and wasn’t concerned with the marketability of the book. They made a nice five-figure advance, that in the past I would have jumped at. The problem is, like almost all contracts these days, they wanted print, ebook, and audio rights.

Selling the ebook rights is problematic because there are things that publishers can’t (or won’t) do. Some examples:

Removing DRM – which aside from a few publishers such as Tor (and I think Angry Robot) is still on virtually all published books. I think DRM does nothing to prevent piracy (it is so easy to strip off) and for legitimate buyers it prevents reading on multiple devices.

Bundling ebooks with print versions – Up until recently there was no easy way to do this, but in September 2013, Amazon announced MatchBook, where publishers can make the ebook available for $2.99, $1.99, or free if the customer previously bought the print copy. The day the program was announced, I wrote to Orbit asking to have my books placed in the program. They haven’t. Bundling, is something I feel strongly about. I’d rather have a reader buy more books (by me or other authors) than have to pay twice for something they already purchased.

Netflix for Books – Subscription models for books is really heating up. There are three major players now: Entitle, Oyster, and Scrid, and Audible has been very successful selling titles this way. Hollow World is in all of these programs, but if I had signed over the ebook right it would be in none. We are still in the infancy when it comes to subscription book buying, but I think it is an area that will eventually take root and grow…and I want my books available when it does.

Book Bundles – Story Bundle & Humble Bumble offers a great way to provide exceptional value for readers, and have authors pool their audiences to increase exposure. Hollow World was in the Sci-Fi Saturday Night bundle where for as little as $10 readers could receive 7 books. Again, if it had been published conventionally I couldn’t have taken advantage of creative offers like this.

Customized Content – Another cool thing about retaining my ebook is the ability to be experimental with the book itself. My Riyria books are remarkably free of swearing. It’s not that I object, it’s just that I didn’t think it fit that story. In Hollow World, it would go against character if Warren Eckard didn’t swear like a sailor. Still, I knew that I would alienate some of my readers, and it be difficult for parents to share the book with their children. The answer…make two versions. The commercially available copy of Hollow World has both an explicit language version and a swearing free version. Readers can pick which one they want, if they desire a copy that doesn’t contain both, for instance to give to their kids, they can just request a free one from me.

Because I wanted to do all these things, I turned down the five-figure advance and continued on my path to self-publication. But then another idea came to Robin…sure it would be impossible for a mid-list author like myself to get a print-only deal with a major publisher, but a smaller press might be more flexible…enter Tachyon Publications.

Art by Marc Simonetti

After reading the book, they, too, wanted to add Hollow World to their roster, and were willing to accept our condition of print-only. Being a small press, they couldn’t offer a huge advance, and to be honest, I could have cared less about the money offered. I already made a good “advance” by the over funding of the Kickstarter, and since I earn out my advances anyway, it just means get money sooner rather than later. What I cared about is Tachyon’s reputation for picking stellar projects (as evidenced by their nominations and wins for the Nebulas and Hugo) and their distribution network. Going self-published was great for my ebook readers, but those who prefer paper would have great difficulty finding my books in their libraries or bookstores. By signing a print-only deal with Tachyon that problem was solved.

For audio rights, the publishing landscape is even more revolutionary. Historically, publishers sign audio as a subsidiary right and collect 50% of any revenue that it brings in. When audio book sales were low, this wasn’t a problem. The author and publisher generally made only a few thousand dollars, but nowadays audio sales are huge. In fact, my recent royalties show 11% print, 47% ebook and 42% audio. With the growth in audio, the landscape is more competitive, and I’m finding several organizations vying for my audio rights. Today the author has several options including: self (through Amazon’s ACX), direct with Audible (who is being very aggressive about acquiring titles directly), through audio producers (such as Recorded Books, Brilliance, and Tantor), and of course through the traditional route of signing those rights to their ebook/print publishers. For Hollow World, I chose to go through Recorded Books, because they have done such an amazing job with my Riryia stories, but in retrospect I would have made much more if I had gone with ACX, especially considering it would have been released under the old royalty scale which gave 50% – 90% to the author (current ACX royalties are 40% – which is still good, just not as profitable as it once was).

Buy Hollow World by Michael J. Sullivan: Book/eBook

Having Hollow World as a hybrid book (ebook-self, print & audio traditional) hasn’t impacted its ability for foreign language sales. We already have translation deals for Portuguese and German and I expect there will be more contracts coming soon. But since we are talking about unconventional publishing here I should mention Bablecube, a service where authors can post their books, translators do their magic, and Bablecube publishes in various countries. Bablecube takes 15% of any sales made, and remaining is split between the author and translator. At the lower ranges, the translator receives the highest percentage, so they can recoup the cost of their labor, if more than $8,000 worth of books are sold, the sharing switches and the author earns 75% and the translator just 10%. I think it is a brilliant idea, and I’m enrolling both Hollow World and some of my Riyria works for languages I’ve not sold rights to.

So as you can see, there are a lot of different ways of getting your books out these days other than just through a big-traditional publisher, who is going to insist on acquiring all the major rights. What I hope, is that authors will consider ALL their options rather than just publishing the way they have always done, or the way others have told them it should be done. By picking and choosing, you can maximize the income you receive from your book, and hopefully that will mean more authors quitting their day jobs and writing full-time. After all that means more great books for readers and ultimately that is the goal we all are trying to reach.

April 10, 2014

Pixel Art Perfection: Heart Machine’s Hyper Light Drifter

Explore a beautiful, vast and ruined world riddled with unknown dangers and lost technologies. Inspired by nightmares and dreams alike.

Every so often, a project, whether it’s a book, a film, a videogame, or whatever, crosses my path and I can’t help but stop to stare. The first time I laid eyes on Hyper Light Drifter‘s protagonist, a nameless Drifter, lounging beside a pixel-perfect fire pit, I fell in love. When I read a description of the game’s ambitions, I knew it was true love. Hyper Light Drifter is a “2D Action RPG in the vein of the best 8-bit and 16-bit classics, with modernized mechanics and designs on a much grander scale.”

“Miyazaki films have taught me that beautiful animation and design add life to a world,” described Hyper Light Drifter Lead Designer, Alex Preston in the game’s Kickstarter campaign. “From characters to background elements, everything is lovingly crafted while I hum show-tunes and squint suspiciously at the flickering pixels until they perform as intended.

“I want it all to be as beautiful as possible, forging color with the dark and eerie wastes and intimidating landscapes.”

Like many passion projects, Hyper Light Drifter has an unusual origin, Preston’s experience in living with a genetic heart condition. “It goes into everything I do, really,” Preston told Rock Paper Shotgun in a 2013 interview. “My maladies have always been my art. Especially in this game, the story revolves around an ailing drifter. He’s coping with his own set of problems, but he’s still managing to live his life and do his job, essentially. There’s definitely some autobiographical elements in the story.”

“Visions for this game have been fluttering in my skull for ages,” Preston explains on the official website for Hyper Light Drifter. “Something dark and fantastic, with giant forests to navigate, huge floating structures to explore, deep crumbling ruins to loot, massive throngs of enemies to rend, and behemoths both flesh and mechanical to overcome.”

Hyper Light Drifter wears its inspirations on its sleeve, as Preston is quick to point out. “It plays like the best parts of A Link to the Past and Diablo, evolved: lightning fast combat, more mobility, an array of tactical options, more numerous and intelligent enemies, and a larger world with a twisted past to do it all in.”

Preston’s Kickstarter campaign is long over, having raised a whopping $645,158 (of a proposed $27,000 goal), ensuring that Hyper Light Drifter will be released on PC, Mac, Linux (DRM-Free or Steam), PS4, Vita, Wii U, and OUYA. The game’s developer/publisher, Heart Machine, is aiming for release sometime in 2014. If you’d like to support the project, or preorder a copy of the game, check out the official website.