Aidan Moher's Blog, page 17

September 2, 2014

Cover Art for Half a War by Joe Abercrombie

And so ends the transformation of these miraculous weapons from a solid, to a liquid, and, finally, superheated gas. What comes next? No one knows.

Half a War is the concluding volume in Joe Abercrombie’s YA/sorta-YA fantasy the Shattered Sea trilogy, which began with 2014′s Half a King. The second volume in the trilogy, Half the World, will be published in February 2015, and Half a War is expected to be published in July 2015.

The post Cover Art for Half a War by Joe Abercrombie appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 28, 2014

Talkin’ Rockets, Hugo Awards and LonCon3 with Foz Meadows, Justin Landon, and the Rocket Talk Podcast

This week, I had the opportunity to join two good friends and fellow Hugo-nominees, Foz Meadows and Justin Landon (host), on Episode 24 of Rocket Talk. The three of us spent a lot of time together at LonCon 3, so we take the opportunity to discuss the convention, diversity in the fan community, the Hugo Awards, and even make a few book recommendations!

In this episode of Rocket Talk, Justin invites Hugo-nominated blogger Foz Meadows and Hugo-winning blogger Aidan Moher on the show to talk about their experience at Loncon3 and the Hugo Awards ceremony. Their conversation covers the convention itself, the winners and losers of the Hugo Award, the nature of fandom, how fandom is evolving, and finishes with a few book recommendations for the voracious genre reader.

Listen to Episode 24 of Rocket Talk on Tor.com

or

Subscribe on iTunes

Near the end of the episode, Justin, Foz, and I all recommended some novels. My recommendations were:

City of Stairs by Robert Jackson Bennett (my favourite novel of 2014 so far)

The Eternal Sky Trilogy (beginning with Range of Ghosts ) by Elizabeth Bear

The post Talkin’ Rockets, Hugo Awards and LonCon3 with Foz Meadows, Justin Landon, and the Rocket Talk Podcast appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 26, 2014

Kowal’s Hugo-winning Story Rises to the Stars

Editor’s Note: This review is spoiler-heavy. If this bothers you, please go read “The Lady Astronaut of Mars” on Tor.com, then return. Spoilers: it’s worth it.

Science fiction offers many things to readers. It allows them to be transported to another time, to wonder about the future, to see sights and visit worlds that are currently out of human reach. To writers, it provides a canvas that begs for speculation, to take issues that challenge us individually and as a society and examine them through a lens warped by time, imagination, and creative license.

Mary Robinette Kowal’s “The Lady Astronaut of Mars”, which recently won the Hugo Award for Best Novelette, is, on the surface, a wonderful and charming tale of an alternate history where NASA reached Mars during the ’50s. Peel back the layers, however, and Kowal’s Martian colony is alive with questions of aging, loyalty and family. Though she never quite provides answers, Kowal challenges readers to contemplate these themes that run through all our lives.

Time was when I couldn’t walk anywhere on Mars without being recognized as the Lady Astronaut. Now, thirty years after the First Expedition, I was just another old lady, whose small stature showed my origin on Earth. Elma, “The Lady Astronaut of Mars”

Art by William Smith

We rose to the stars.

Immediately, the charm of Kowal’s vision of an alternate history where the warm, fuzzy kitsch of the ’50s never wore off after punchcard-programmed intersolar space travel put humanity on Mars, is hard to resist. Rather than being locked in by science fiction’s traditional reliance on hyper-realistic and -progressive science, Kowal instead creates a unique setting that sets aside any expectations of buy-in from the reader. It’s zany, and cozy, and so absurdly adorable that Kowal immediately puts the reader at ease, and allows them to shift focus from the logistics of space travel to the interpersonal relationships that lie that at the heart of the narrator’s dilemma.

Elma, the famed “Lady Astronaut of Mars”, thinks her days of space travel and being the face of intersolar travel are far behind her. Doubly so as her beloved husband faces an inevitable fate, battling terminal illness. However, as is fate’s often cruel way, Elma is blessed/cursed with an opportunity to do what she’d dreamed of for decades — return to space — but at the cost of missing the final weeks and months of her husband’s life. Much of “The Lady Astronaut of Mars” explores this sophie’s choice, and, through Elma’s conversations with the other people in her life, with varying degrees of closeness to her and her husband, ultimately seeks out answers to understand how someone might face such a difficult fork in their lives.

Art by: Voila Vala | Jo Chen | Colin Foran

I wanted to. I wanted to get off the planet and back into space and not have to watch him die. Not have to watch him lose control of his body piece by piece.

And I wanted to stay here and be with him and steal every moment left that he had breath in his body.Elma, “The Lady Astronaut of Mars”

Most touching heartbreaking of all, are the moments the readers spends with Nathaniel, Elma’s dying husband, who himself is suffering through not only his illness, but also watching its tendrils wrap themselves around the dreams of the woman he loves. Nathaniel’s strength and perspective through the story is subtle but deeply pervasive. It waxes when Elma’s wanes, and in that interaction the reader is introduced to the genuine love of their marriage. Marriage is about mutual strength and respect between the two partners, and Kowal delicately reveals both their shared and individual hardships, and the extreme loyalty and love that binds their marriage.

I used to be a tall woman, you know.Elma, “The Lady Astronaut of Mars”

Art by Charles Silva

At the core of the story is Elma’s obsession with the past and Nathaniel’s pragmatic understanding that the future comes no matter what. While coming-of-age narratives are not uncommon, especially in genre fiction, Kowal swaps teenagers for characters in their sixties, and addresses that life doesn’t stop once you turn 40, or 50, or 60. No matter what life stage you’re in, decisions come up, and the remainder of a lifetime still awaits. As Teresa Frohock said, “People don’t cease to exist after thirty, nor do they turn into fountains of knowledge and wisdom.

“It’s easy become lost in the wonder of youth, but wonder does not automatically stop after a certain age. Even at fifty, I am still discovering new aspects of self and the world around me.”

As Elma muses about her diminished height, the idea that her beauty has been lost along with her youth, and her nostalgia for the days when her and Nathaniel were paving the road to Mars, the reader begins to understand the subtle ways that her husband’s illness has become a prison for her. It is a source of anxiety and depression that limits her future as much as it does his. Nathaniel on the other hand, has a perspective available only to those who have come to grips with their own mortality. While he resents the physical degradation of his body, he does not appear to fear death. Or the unknown — he was an astrophysicist who helped to put humankind on Mars, after all. Elma allows Nathaniel to dream of a future that is bright and hopeful, and he cannot stand the idea that his illness would also hold her back from achieving their shared dreams.

The lynchpin between them is the their new doctor, a young woman named Dorothy, who herself was inspired by Elma’s career as a female astronaut and martian colonist. Through Dorothy, both Elma and Nathaniel are able to perceive the thread that weaves through Elma’s past and future, and recognize that they are not two separate things to be regarded in a vacuum, but one continuous part of a person’s being. Dorothy, so passionate and caring, allows Elma to shed the demons that threaten to keep her on Mars and embrace the active future, and Nathaniel is given the grace of watching his wife soar again among the stars.

She’d come to Mars because of me. I could see that, clear as anything. Something I’d said or done back in 1952 had brought this girl out to the colony.Elma, “The Lady Astronaut of Mars”

“The Lady Astronaut of Mars” is a masterpiece of character, and a rich experience that begs to be read over and over again.

“The Lady Astronaut of Mars” is full of quaint and often beautiful vignettes as Elma’s friends and fellow martians help her navigate through her difficult situation. Dorothy and Nathaniel are the most prominent, but several other characters crop up throughout the story, such as Dorothy, and each of them sheds a different light on both Elma and the martian colony.

Kowal has the ability to imbue her stories with rich life, to tug on the reader’s empathetic heartstrings while still challenging them to consider the many themes that run like tendrils between the lines of the narrative. “The Lady Astronaut of Mars” is at once charming and heartbreaking, tragic and hopeful. The greatest stories are layered and nuanced, and Kowal continues to prove that she’s a master at painting life onto science fiction’s limitless canvas, and creating universes that beg to be explored — all within the tight limitations of short fiction. “The Lady Astronaut of Mars” is a masterpiece of character, and a rich experience that begs to be read over and over again.

The post Kowal’s Hugo-winning Story Rises to the Stars appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 25, 2014

“What We Didn’t See: Power, Protest, Story*” by Kameron Hurley

My parents taught me not to stare.

My parents taught me not to stare.

As children, even as adults, prolonged staring at others is something we do when we first encounter difference. It’s a long, often critical or fascinated look at something to try and understand it, to gauge where it fits in our taxonomy of things. First: is this a threat? Should I respond with a fight…or flight? Second: where does this person fit within my existing boxes? Woman or man? Black or white? Friend or foe?

We have nice neat boxes for everything, boxes we learned in childhood which have been reinforced by stories, by media, by our peers, as we grow older. We stare longest when we cannot fit what we see into an existing box; when we cannot figure out if it’s dangerous, or merely different: which many of us, unfortunately, still feel are the same thing.

And, if after staring long enough, we decide that this different thing is dangerous: we kill it.

Art by James Eugene

I grew up in a town that was about 98% white. I would learn, decades later, that it was purposely constructed that way, as were many places in the U.S., including the western U.S. where I grew up (California went so far as to ban the immigration of free and enslaved blacks into the state, though that did not prevent those already there from continuing to eke out a living. Also see: the exclusion laws of Oregon).

When I was three or four years old, my family took me to Reno, Nevada. We stayed at the Circus-Circus hotel, and while my dad went downstairs to play cards, my mom ordered up a special treat: cheesecake, delivered in a way totally new to me – via room service.

The knock came on our door. My mom opened it. And there was a very dark man in a very white coat holding a silver-colored tray.

“Mom!” I said, three or four years old and having never seen anyone much browner than a pale person with a suntan. “Why is that man so black?”

My mom, mortified, laughed and hushed me and tipped generously, I learned later. These were not polite questions. They revealed where and how I’d grown up. The question revealed the constructed lie of how we lived.

When he was gone, she told me, simply, that some people were born with different colors of skin, like different colors of hair. Being three or four years old, I was perfectly contented with this answer, and went on to happily eat my cheesecake. It would be four or five years more before I realized that in our society, skin color was not seen in the same way hair color was, even if, in my kid’s view of the world, it made exactly the same amount of difference as blue eyes or brown, red hair or black.

Even a child cannot escape history. We can’t escape what came before us.

Looking back, the irony is not lost on me, of course: the irony that the first person of color I ever saw, as a white child, was a black man serving me cheesecake on a polished platter.

Statue by Ferri Farahmandi

Difference has been managed in a variety of ways, across times and cultures. Because difference is, of course, in the eye of the beholder. The Twilight Zone episode of the same name posits a world where beauty itself is interrogated as a construct. A female patient spends nearly the entire episode covered in bandages while her doctors converse with her, always with their own faces out of sight, in shadow. In the end, it’s revealed that the woman has a movie-star beauty of a face: pale skin, pale hair, sparkling eyes, pleasingly symmetric features.

Hollywood beauty. The beauty of our American culture, collectively, is told to strive for – even if it is so far beyond and outside what any of us actually look like.

Her doctors, nurses, the “normal” people in her world, are revealed to have the melted-looking faces of deformed pigs. They are the beautiful ones. She is the anomaly.

She is the difference.

In the end, she is shuttled off to a concentration camp. A ghetto created for people of her “kind.” They say she will be happier there, among those like her. Most importantly, though: she will be hidden from the eyes of those unlike her. They will be free from seeing her ugliness.

Her difference makes them uncomfortable, and for that grave crime, she must be locked away.

Sometimes difference from a culturally-defined norm has been celebrated – a mark of the gods, divine. Sometimes feared – a mark of evil. But most often, in the culture we call American, what we’ve done the last couple hundred years is lock up and shutter away and refuse to showcase all but the very narrow subset of humanity those in power would like us to believe are the true normal. This dangerous lie has led to the dehumanization of millions; and people who are dehumanized are not simply written out of the cultural narrative. They are, very often, utterly and literally removed from the face of the earth.

I have written before about how our broken sense of what is “normal” feeds into dangerous narratives, and how it limits the lives of women.

These stories – that there is this very narrow subset of “normal” people – upper middle class, white, women being women, men being men – serves to make the rest…not.

But the reality is, this system of stories goes far beyond rewriting history to limit how we believe women fought, or lived. These stories – that there is this very narrow subset of “normal” people – upper middle class, white, women being women, men being men – serves to make the rest…not. Anyone who doesn’t fit is, of necessity, abnormal.

Abnormal often meaning not human.

And not human… well, we know what we do to things that aren’t human, don’t we?

The fastest way to dehumanize a person, or subset of people, is to make them invisible. To lock them away. To say, “This is the stuff of circuses and mistakes. This is the stuff of nightmares.”

It’s easier to reject,fear and destroy what we don’t understand.

It’s impossible to understand what we’re never allowed to see.

Even if, in many cases, what we never see is ourselves.

Art by Tomas Honz

There was an uncomfortable moment of silence from the father, and when he responded, I could hear the tension in his voice. “I don’t know,” he said.

I passed a man and his son headed to a football game the other day. The news is, at present, all about the protest and unrest in the city of Ferguson, Missouri, where peaceful protests in reaction to the shooting of an unarmed teenager were met with an increasingly violent police response.

One would think there would be a profound backlash against this militarized police response, no matter the race of the victim.

The boy and his father crossing the street to the stadium now were white; the boy was about eight or nine years old, and he asked, “Dad, what if it had been a black cop shooting a black kid? What about a white cop shooting a white kid? Why are people upset because it was a white cop shooting a black kid? Would it be different another way?”

There was an uncomfortable moment of silence from the father, and when he responded, I could hear the tension in his voice. “I don’t know,” he said.

I don’t know.

These two people, likely growing up in neighborhoods as artificially constructed as the one I lived in, had no reason to know. They had not spent their lives terrorized by police. Had not had loved ones shot in the street outside their homes. Had not grown up in neighborhoods where simply looking the way they did meant they were quite likely to spend a great deal of their time in prison. The statistics, for these two people – a white boy, a white man, were very different than for others.

Of course they don’t know.

People in power don’t want them to know. They want these people’s allegiance against the Other.

Divide and conquer is a time tested strategy. Divide and conquer works.

How do you explain four hundred years of prejudice, oppression, exclusion laws, terror, to an eight year old middle class white boy on the way to a football game?

The truth is, he will likely never see it. Never even notice it.

And that’s the fault of mainstream stories. It’s the fault of our laws. It’s the fault of the culture we call “ours” but isn’t really representative at all. It is the culture of a select few, assumed to be the culture of many.

But “us” is the fiction. “Ours” is the lie.

Who is “us”?

Art by Brenoch Adams

My academic advisor in graduate school was born with phocomelia. We went into town one day to print and bind copies of my hundred-and-some-odd-page thesis, and she popped into a fabric shop to run an errand before we went to the printer.

I remember seeing a young child at the counter, standing next to his mother, staring at my advisor. Big eyes. Staring. Forever and ever. No break. Goggle-eyed.

I remember being irrationally angry at this child for staring, and I stepped between him and my advisor to shield his view.

Now, I couldn’t tell you why I did it. She had to deal with these stares every day, and worse. It was me who was angry. It was me who was uncomfortable. It was me frustrated with how we notice and process difference.

My mother always told me not to stare. It was rude. It said, “You are different.” And difference, acknowledging difference, was bad. To acknowledge difference was to acknowledge everything that was broken. Yet…how was pretending not to see someone any better?

I feared that stare. Even from a child who knew nothing of its historical implications.

In truth, what was being protected by not seeing was my naïve 4-year-old question that revealed how I was raised, “Why is that man so black?” Staring said we were rural simpletons with a limited view of the world. It wasn’t the difference itself that was terrible to acknowledge, for my parents, I think: it was acknowledging the fact of our own ignorance.

But the gaze, the stare, as many women know, can also be seen as a prelude to an assault. We fear and sometimes covet what we see. And what we fear and covet, often, we will violently assault.

I feared that stare. Even from a child who knew nothing of its historical implications.

I saw myself in his stare.

And that made me angry.

So what is it that we don’t see? That we have stopped seeing? That we don’t want to see?

So what is it that we don’t see? That we have stopped seeing? That we don’t want to see?

What we don’t see has a great deal to do with who we are, how we grew up. It has to do with how our society manages the ebb and flow of people; what it considers different, undesirable.

Whether we believe we’re living in a dystopia today depends on where we’re sitting.

A banker’s utopia is a factory worker’s dystopia. Utoptic gated communities which do not permit low-income residents are utopic only for the few who live there. They do not fix the wider problem of crime and poverty. They simply push it out to the fringes, where they can’t see it.

But unseeing a thing doesn’t make it disappear.

In truth, pushing people aside, locking them away, putting them into ghettos, erasing them from stories, does far more harm than any amount of seeing will do.

Because what we see we actually have to acknowledge as a part of the wider story, the wider culture.

What we see is us.

Art by Olivier Malric

I write stories. It’s what I do. It’s what my colleagues do. By day I craft marketing and advertising copy that’s still mostly white, mostly ableist, mostly upper middle class, assumed heterosexual. Mostly male.

Heroes can have limitations of mind, of body, limitations imposed at birth, by circumstance, or by society, and still be heroes. They can be all of this and more.

But as the voices we see and hear every day become harder to ignore, harder to unsee, that is changing too. I can put different people onto the page, and use different language – not just at my day job, but my night job, too. My novels can give you a hero of either or other or no gender, from a variety of cultures of every type and hue and practice. My heroes can have limitations of mind, of body, limitations imposed at birth, by circumstance, or by society, and still be heroes. They can be all of this and more. They can be seen.

And publishers will buy them. And readers will read them.

My fear of being unpublished, pushed out, ignored, because of who or what I write about is fading.

This is changing not because the people themselves are there any more or less than they (we!) used to be. The world has always been a diverse and interesting place. But with the rise of social media and instant communication platforms, it’s easier to organize and speak out. It’s easier to come together. It’s easier to insist on being seen. It’s harder to forget or wipe away the history that brought us all to the places we started this life within, the cultural constructs that bound us. The constructs we are working so hard to unmake, refute, challenge.

So if you find yourself wondering why so many of us ask to be included now, and put ourselves and others into stories we’ve been written out of, perhaps, first ask why that inclusion is considered political, but the erasure was not: the laws, the asylums, the housing policies, the repression, the abuse.

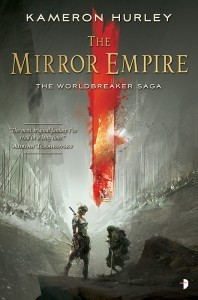

Buy The Mirror Empire by Kameron Hurley: Book/eBook

There is nothing more political than erasure. Than unseeing.

The world is not changing. It’s been this way all along. We have been here all along. All that’s changing is what you see. You just never saw us. I never saw us.

I, for one, have hungrily sought out that fuller picture, and am working hard to contribute to showcasing it. However fraught and horrifying it often is, it’s the one we live in. It’s the one we must work with.

It’s the one we must change.

But we can only reimagine the world if we see the one we’re actually living in.

* Further reading on the origin of this title choice.

The post “What We Didn’t See: Power, Protest, Story*” by Kameron Hurley appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 21, 2014

Cover Art for The Skull Throne by Peter V. Brett

I’m glad to see that artist Larry Rostant is giving Lara Croft some work while she’s in between installments of Tomb Raider. The Skull Throne will hit store shelves on March 24, 2015 from Del Rey.

The post Cover Art for The Skull Throne by Peter V. Brett appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 20, 2014

Chatting Hugos, LonCon 3, and Fandom on the Sword & Laser Podcast

So. Dream come true.

No, not the Hugo. Being invited by Veronica Belmont and Tom Merritt for an interview on the Sword & Laser podcast. I’m a huge fan of their work, and had a blast chatting with them about the Hugo Awards, LonCon 3, the SFF fan community, and working with Kameron Hurley on “We Have Always Fought”.

S&L Podcast – #187 – How to Win a Hugo

P.S. Sorry for the audio quality. iPhones aren’t great recording devices, apparently.

The post Chatting Hugos, LonCon 3, and Fandom on the Sword & Laser Podcast appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 19, 2014

A Dribble of Ink Wins 2014 Hugo Award

Wow.

If you’ve seen the results, or watched the Hugo Awards ceremony on Sunday, you’ll know that A Dribble of Ink won the Hugo Award for Best Fanzine. I seriously have no words. Thank you to everyone who has supported A Dribble of Ink throughout the years. If you’re interested, you can watch my acceptance speech, which has been described to me as “adorable” by several people.

In addition to the award for Best Fanzine, A Dribble of Ink also published Kameron Hurley’s We Have Always Fought: Challenging the “Women, Cattle and Slaves Narrative”, which took home the trophy for Best Related Work. She also won for Best Fan Writer. Kameron posted her acceptance speeches for the award on her blog, and they are well worth a read.

I’d also like to extend congratulations to all of the other winners, and, most specifically, to the lovely Mary Robinette Kowal, who was a lifesaver in the craziness that followed the award ceremony, and my LonCon3 roommate John Chu, author of “The Water that Falls on You from Nowhere”.

And, finally, if you’re not already reading my co-balloters, The Book Smugglers and Pornokitsch, please go check them out. They’re terrific blogs, even more wonderful people, and I expect them to be on the Hugo Ballot for years to come.

Thank you.

The post A Dribble of Ink Wins 2014 Hugo Award appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 8, 2014

Explore the vast corners of the universe with Kuldar Leement

Feeling a little cabin-fevery stuck here on Earth? Not rocket ship to take you to the stars and beyond? Estonian illustrator and graphic designer Kuldar Leement can help you out. His gorgeous science fiction art mixes startling imagery with bold, high-contrast colours, and the ability to transport you to the furthest edges of the universe, where boundless imagination lives. The first image, titled “Curiosity” is particularly striking. Leement created as an homage to NASA.

You can find more of Leement’s art on his online portfolio and his DeviantArt gallery.

The post Explore the vast corners of the universe with Kuldar Leement appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

Cover Art for Nemesis Games by James S.A. Corey

Artist Daniel Dociu, designer Kirk Benshoff and Orbit Books keep knocking it out of the park with this series. Gorgeous, iconic. *drools*

Nemesis Games is the fifth volume in Corey’s popular science fiction series, The Expanse. It is due for release in 2015.

The post Cover Art for Nemesis Games by James S.A. Corey appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

August 6, 2014

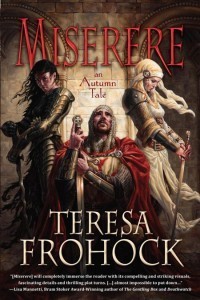

“Women Made of Chrome” by Teresa Frohock

“Jane Navio was a chrome-assed bitch … but she was right.” Up Against It, M. J. Locke

I wish there were more Jane Navios in fantasy. Oh, you see them in science fiction and horror, but not in fantasy. There is an unwritten code that women in fantasy novels must not be older than thirty, or they’re all the grandmotherly types over sixty, but rarely are there any in the forty to fifty range. There are a few exceptions to this rule, but since the 1990s, female characters over forty seem to have faded into the background scenery, and very few are protagonists.

Art by Alexandra Douglass

Part of this is our current culture. I see it every time I go online. So-and-so actress is aging well, but only because she appears as if she is ten or twenty years younger. Helen Mirren and Dame Judi Dench are the exceptions to this rule. Both of these ladies have played chrome-assed bitches in their films. They don’t waffle or give long, righteous speeches about women and what they need. They wade right into a situation and get the job done.

The genre community talks about writing worlds that are a clearer reflection of the world in which we live, yet no one talks about the need for older protagonists. People don’t cease to exist after thirty, nor do they turn into fountains of knowledge and wisdom. Old bearded men, who guide young men, or ancient wise women, who are kind and giving, simply don’t exist in abundance in the real world. It’s easy become lost in the wonder of youth, but wonder does not automatically stop after a certain age. Even at fifty, I am still discovering new aspects of self and the world around me.

Like everyone else, older people like to see themselves reflected in the fiction they read. When I posed the question on Twitter one day, people were quick to mention George R.R. Martin’s Catelyn and Cersei as good examples of mature women in current literature, and I can’t disagree. Of the two, I’d say that Cersei falls closer to chrome than Catelyn. They are the biggest reasons I’ve stuck with the series as long as I have.

There were chrome-assed bitches in the days before chrome.

The younger women in the series don’t interest me as much, because they are still at the point of their lives where they feel locked into their circumstances by virtue of their gender. By the time most women hit forty, they are just ready to kick ass.

There is something freeing about being forty. For a woman who has reached emotional maturity, she no longer cares what people think of her. There is no “leaning in.” Women over forty know how to navigate conventional prejudices and will subvert those biases with a word. A woman over forty will speak her mind.

Ah, but people will say, because there are those who say these things as if saying them over and over will somehow make them true: Ah! But fantasy is like history and in history, women only existed to be saved or raped or murdered.

I call bullshit. Women ruled not just kingdoms but their homes as well. There were chrome-assed bitches in the days before chrome.

Remember their names, these women who lived and fought and taught:

Art by Chester Ocampo

Hatshepsut was a chromed-assed bitch who ruled first as regent, then as a pharaoh;

Athaliah got her chrome as the queen of Judah, she ruled for seven bloody years;

Artemisia I commanded five ships during the Battle of Salamis. She didn’t get that command by being demure;

Gaohou seized power from her son to become China’s first woman ruler, which is not the first time such a woman has decided her son or husband is incompetent to rule (see Catherine the Great);

Queen Sondok, ruled the Korean kingdom of Silla and led her country through a conflict with a neighboring kingdom;

‘A’ishah, Muhammad’s widow, rebelled against the caliph ‘Ali at the Battle of the Camel at Basra.

The second Council of Nicaea was convened by the Byzantine ruler Irene;

And let us all pay homage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, who accompanied King Louis VII on the Second Crusade, and when their marriage collapsed, she wed Henry II, the future king of England.

The older the woman, the more dangerous she becomes. Chrome-assed bitches don’t need guns or swords, they have their brains.

The older the woman, the more dangerous she becomes. Older women didn’t need weapons to take the world down; they changed the course of history with a whisper. A word in the right ear brought down kings and queens, or maneuvered their kin into power. Chrome-assed bitches don’t need guns or swords, they have their brains.

Fantasy tends to be marketed toward the younger generation, and that’s okay, but often that very marketing pushes the older people away. We never stop loving fantasy or believing in wondrous tales. We do, however, like you, move away from literature that refuses to see us as we are.

Older women are not all sweet mentors, who are patient and gentle and good. Some of us are chrome-assed bitches who know how to get things done. I wanted to see stories about people like me, so I wrote two chrome-ass bitches of my own.

Art by: Kattevoer| Chase Stone | Matthew Stewart

These women don’t have time for lamentations. They are also intensely self-aware, which is something that comes with age.

Rachael is forty and Catarina forty-four. Both are chrome-assed bitches of the highest order. These women don’t have time for lamentations. They are also intensely self-aware, which is something that comes with age.

Lucian might think he is the prize between his sister and his lover, but Rachael and Catarina have other concerns. They know the bastion with him within their ranks has the greatest edge. All three adults have personal stakes in the game, but Rachael and Catarina are also seeing the big picture. They both want power and make no secret of it.

Rachael will drive the youth of the bastion into war. She will sacrifice the few to save the many, because she has been to Hell and knows what awaits them if they fail. While some readers might think that Catarina lost the game in Miserere, they too fail to see the big picture. For it is only through death that she can find eternal life and reign as the Queen of Hell.

Buy Miserere by Teresa Frohock: Book/eBook/Audio

Art by klaatu81

Older women are much more fun to write. They’ve reached an emotional maturity that is not about blame, but about responsibility. They do not perceive the world strictly in shades of good and evil. They view each problem as unique, and they measure the situation by its own merits. Emotional maturity is an insidious thing. It robs our sight of black and white and blurs issues into shades of gray, but chrome-assed bitches can see through the fog to get things done.

I dream of the day when I can locate mature female characters that aren’t ancient wizards or wise old seers and side props to speed little children to their destinies. I want to read about diplomats and intrigues, not another child who wars her way to power. Just like you, I want to read about people like me in the genre that I love.

The post “Women Made of Chrome” by Teresa Frohock appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.