Aidan Moher's Blog, page 24

April 9, 2014

Elizabeth Bear announces The Lotus Kingdom trilogy, a sequel to The Eternal Sky

I’ve made no secret of my excitement for Elizabeth Bear’s The Eternal Sky trilogy. I recently sang my praise of the trilogy in a review of the final volume, Steles of the Sky, which was released yesterday:

Bear fills Steles of the Sky, and the entire trilogy, with a masterfully crafted meld of Asian and Middle Eastern mythology, legend and history with the wholly unique and deeply considered secondary world she has created. Shedding the tried and true landscapes and politics of faux-medieval western Europe, Bear introduces readers to a diverse world and political landscape that avoids feeling like the same ol’, same ol’, despite readers a story that uses many of the genre’s most recognizable tropes—ancient magic; an exiled youth of royal blood; a journey from one side of the map to the other; evil sorcerers; dragons; clashing armies.

So, it is with no small amount of enthusiasm that I pass along news that Bear has sold a sequel trilogy, The Lotus Kingdom, to Tor Books. “While Range of Ghosts, Shattered Pillars, and Steles of the Sky comprise a complete story arc in and of themselves,” said Bear, via The Big Idea on John Scalzi’s blog, “I can now reveal that Tor will be publishing at least three more books in this world.”

The Lotus Kingdoms, will follow the adventures of two mismatched mercenaries–a metal automaton and a masterless swordsman–who become embroiled in the deadly interkingdom and interfamilial politics in a sweltering tropical land.

The first volume of The Lotus Kingdom will be released in (*gasp*) 2017. Meanwhile, if you haven’t read The Eternal Sky trilogy, you should, starting with Range of Ghosts: Book/eBook.

April 8, 2014

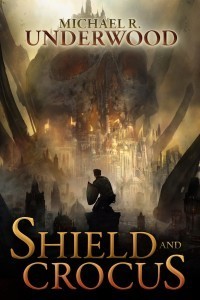

Michael R. Underwood discusses his first epic fantasy: Shield and Crocus

Michael R. Underwood might best be known to those of us in the SFF blogosphere as one of the main sales and marketing managers at Angry Robot Books. However, the really exciting thing about Underwood isn’t his role at the publisher, but his work on the other side of the table, as author of Geekomancy, Celebromancy, and upcoming releases like Attack of the Geek and Shield and Crocus, his first foray into epic fantasy.

And, my does it sound epic. I caught up with Underwood to chat about Shield and Crocus, the recently revealed cover art, and what it’s like working with 47North.

“This book has meant the world to me for so long, and it’s a dream come true to get to share it with readers,” he told me when I asked him about Shield and Crocus. “I can’t wait to invite people into Audec-Hal to meet the Shields and hear their story.”

Underwood might best be known for his urban fantasy, but “Shield and Crocus is a project that’s been with me for the better part of ten years,” he told me.

Shield and Crocus is the story of a desperate band of heroes trying to free Audec-Hal, a city wracked by magical storms and ruled by cruel oligarchs.

So how does that decade worth of writing and re-writing look? “Shield and Crocus is the story of a desperate band of heroes trying to free Audec-Hal, a city wracked by magical storms and ruled by cruel oligarchs,” Underwood described. “The Shields have fought for fifty years, buried friends and lovers along the way, and are are close to the point of no return. If they don’t turn the tide soon, they’ll be washed away, the Shield’s struggles forgotten as the oligarchs write the history of the city in their own images.”

The gorgeous cover for Shield and Crocus, which channels Castle Grayskull from the old Masters of the Universe, erm… universe, was painted by Stephan Martinière, a choice which pleased Underwood, a seasoned publishing industry marketer. “They secured Martinière to paint the cover, and even at the black-and-white stage, I was completely blown away by how amazingly he’d captured the scale, mood, and majesty I tried to impart to the city of Audec-Hal.”

Along with the cover, 47North released the first blurb for the novel, which contains more details about what readers can expect:

In a city built among the bones of a fallen giant, a small group of heroes looks to reclaim their home from the five criminal tyrants who control it.

The city of Audec-Hal sits among the bones of a Titan. For decades it has suffered under the dominance of five tyrants, all with their own agendas. Their infighting is nothing, though, compared to the mysterious “Spark-storms” that alternate between razing the land and bestowing the citizens with wild, unpredictable abilities. It was one of these storms that gave First Sentinel, leader of the revolutionaries known as the Shields of Audec-Hal, power to control the emotional connections between people—a power that cost him the love of his life.

Now, with nothing left to lose, First Sentinel and the Shields are the only resistance against the city’s overlords as they strive to free themselves from the clutches of evil. The only thing they have going for them is that the crime lords are fighting each other as well—that is, until the tyrants agree to a summit that will permanently divide the city and cement their rule of Audec-Hal.

It’s one thing to take a stand against oppression, but with the odds stacked against the Shields, it’s another thing to actually triumph.

“Readers can expect high heroism, transmogrifying storms, elaborate battles, and a city that’s a character unto itself,” said Underwood.

Underwood’s elevator pitch is enough to pique my interest, and likely the interest of fans of Mark Charan Newton, China Mieville, and Steph Swainston, in addition to the general epic fantasy audience. “Readers can expect high heroism, transmogrifying storms, elaborate battles, and a city that’s a character unto itself, all in service of a story about a family of choice that comes together in defense of their home,” Underwood said. “Shield and Crocus is my attempt to bring together the innovative worldbuilding and critical punch of the New Weird with the energetic action and optimism of Heroic Fantasy. I brought a lot of influences with me to the city of Audec-Hal, from China Mieville, KJ Bishop and Jeff VanderMeer to Scott Lynch and Warren Ellis.

“It started as a short story at Clarion West in 2007, and grew into a novel after I got home from the workshop,” he revealed when I asked him about the origin of the project. He also admitted that despite his ties to Angry Robot Books, and a handful of other published novels, selling Shield and Crocus was a slow process.

“I worked and worked, revised and polished, and David Pomerico took it all the way to editorial board at Spectra in early 2011, but the book needed too much work, it just wasn’t ready. David gave me incredible feedback and I went on my way. I worked on the book for a while, then moved on, writing Geekomancy, which would become my first sale. In mid-2013, David emailed me and inquired after Shield and Crocus, since he was at a new posting at 47North and had regretted not being able to to pick up the book and nurture it to publication. I’d recently completed a major revision on spec, and so off it went. And this time, it was ready.”

Underwood is another name to the long list of exciting fantasy and science fiction authors that 47North, a genre imprint of Amazon.com, has been gathering. “Working with 47North has been an incredible experience” Underwood admitted. “They’re incredibly supportive and have given me many opportunities to be involved in the process, bringing my experience from working at Angry Robot into providing input on cover direction, positioning, and more.”

Shield and Crocus will be available from 47North on June 10th, 2014, and is available now for preorder: Book/eBook

April 3, 2014

Tad Williams returns to the world of Memory, Sorrow and Thorn after 21 year absence, in The Last King of Osten Ard

DAW Books announced today via press release that they have bought a new trilogy from Tad Williams, The Last King of Osten Ard. This is a notable event, as Williams returns to the series that launched him to stardom and influenced George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire. The Last King of Osten Ard is a direct sequel to Memory, Sorrow and Thorn.

Which just so happens to be my favourite completed fantasy trilogy of all time.

I’m chuffed.

The press release has the first details about the new trilogy:

In this new trilogy, Williams journeys back to the magical land of Osten Ard and continues the story of beloved characters King Simon and Queen Miriamele, married now for thirty years, and introduces newcomer Prince Morgan, their heir apparent. Also expanded is the story of the twin babies born to Prince Josua and Lady Vorzheva—a birth heralded by prophecy, which has been the subject of feverish fan speculation since the release of To Green Angel Tower in 1993.

In The Last King of Osten Ard, Williams returns with the ingenious worldbuilding, jaw dropping twists and turns, and unparalleled storytelling that have made him one of fantasy’s brightest stars for more thirty years.

The trilogy, The Witchwood Crown, Empire of Grass, and The Navigator’s Children, has no release date.

April 2, 2014

Let’s Celebrate: Final Fantasy VI is 20 years old!

Images via Gysahl Greens Tumblr

Yesterday, Final Fantasy VI (affectionately, and confusingly known as Final Fantasy 3 when it was first released in North America) turn 20 years old. The series changed significantly in the years that followed, so it’s fun to look back at this classic game and remember the impact it had on an entire generation of gamers.

Here’s a little bit of trivia: Scott Lynch named Locke Lamora, protagonist of his popular Gentleman Bastards series, after Locke Cole, one of the central characters in Final Fantasy VI!

What is your favourite memory from Final Fantasy VI?

April 1, 2014

The Way of Kings is paved with peril and many pages

Just one look at the cover of Brandon Sanderson’s The Way of Kings tells you everything you need to know about it. If you’re a fantasy virgin, a passerby in the grocery store, you can tell that it’s about knights and vivid fantastical set pieces. If you’re a long entrenched fantasy reader, you can see that, for all of publisher Tor Books’ will to make it so, the first volume of Brandon Sanderon’s The Stormlight Archives is the “next big fantasy, ” the heir apparent to Robert Jordan’s legendary and flawed opus, the Wheel of Time.

The Way of Kings is big. Thunderously huge. Sanderson might be best known for his work completing the late Robert Jordan’s series, but before that he was known to fantasy fans as one of the more exciting upcoming epic fantasists. His most popular work up to that point was the Mistborn trilogy, a self-contained series that, while applaudable for Sanderson’s eagerness to develop fascinating magic systems, suffered from poor pacing and bloat in both the second and third volumes. The longest of those volumes was two-thirds the length of The Way of Kings, the shortest about half.

Most writers are expected to write an epic fantasy in less than 200,000 words, The Way of Kings flirts with 400,000.

Since then, Sanderson’s star has risen to heights reached by few other working fantasy authors, and as a result the editorial department at Tor has slackened their reins, hoping to nurture the novelist as he attempts to fill the enormous hole left by Jordan’s passing. Even in the early pages The Way of Kings, while Sanderson is busy introducing readers to fallen gods, it’s easy to recognize his excitement at being given the reins to write an epic fantasy in the vein of Jordan, et al. Most writers are expected to write an epic fantasy in less than 200,000 words, yet The Way of Kings flirts with 400,000. Though this immense privilege and freedom for Sanderson’s ambitions hurts the novel, it also allows for a refreshing boldness and scope that the genre has been missing since the completion of the Wheel of Time and Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen.

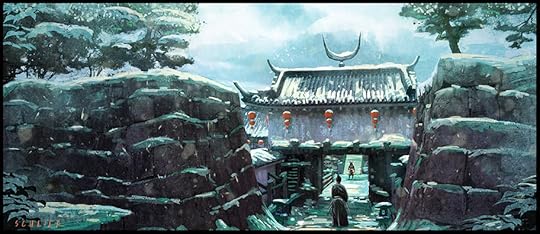

‘Before the Storm’ by Nickolas Russell

I found myself eagerly looking forward to every opportunity I had to crack open its many pages, to immerse myself in Roshar.

It’s difficult to argue that any novel requires 400,000 words to tell its story. It’s an even tougher road to expect a series to need ten such volumes to reach its conclusion. On the surface, The Way of Kings should be enough in-and-of-itself to solidify any chance of anyone arguing successfully for behemoth-sized novels: it’s slow, plodding, over-complicated, and, even at the end of it’s final page, feels more like a prologue to a larger story than one of the longest published novels of the last decade. There’s a lot wrong with The Way of Kings, by all means, it’s a slog of a novel, but despite all of this, I found myself eagerly looking forward to every opportunity I had to crack open its many pages, to immerse myself in Roshar.

Why is that?

There’s a certain piece of every reviewer’s mind that likes to observe and cast a cold pall over fannish excitement, like an objective peanut gallery whose purpose isn’t to amuse with clever jokes, but to carefully cut into the author’s craft and lay it out bare—the novel’s triumphs all the more sweet and pronounced because its failures are exposed for all to see. And so that critic rears its head throughout most of this review. However, over the pitch of its screaming voice, also rises the tempestuous whispers of an unabashed, shameless fan of big, fat, hopelessly labyrinthine fantasy. That voice that has been around in this reviewer’s head since first picking up J.R.R. Tolkien and falling into the wonderful, limitless world of fantasy.

And if The Way of Kings lacks anything, it’s a respect for limitations.

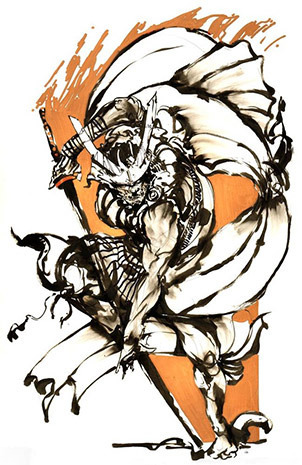

The Way of Kings (Chinese Edition) by Jian Guo

It’s difficult to read The Way of Kings and not be washed over by the love that the author has imbued in his work.

Sanderson is so earnest, so effusively enamoured with his fictional creations, that it’s difficult to read The Way of Kings and not be washed over by the love that the author has imbued in his work. It’s a love of his own creation, but also of the epic fantasy’s lauded history: the enormous scale of Robert Jordan; the worldbuilding and ethnic diversity of Ursula K. Le Guin; the clashing armies of Terry Brooks; the otherworldliness and humour of Jack Vance. The Way of Kings is an homage to ’80s and ’90s fantasy, and, for anyone who grew up reading the great authors of those eras, there’s an almost irresistible desire to forget the novel’s flaws and just enjoy the ride.

The Way of Kings has that same obsessive, addictive quality that makes all of Sanderson’s other works so effective. It’s not so much about what it offers readers, but about what it can offer readers. Promises abound, hints of world-changing events, and mind-bending character developments to come. Nobody does foreshadowing in epic fantasy as well as Brandon Sanderson, and, if his previous work is any indication, every small detail in this early book will have a ripple-like effect on the volumes that follow. Every chapter is full of questions, full of the type of plot developments and world building that fills chatter around water coolers or playgrounds.

“Oh my god, could you believe when Kaladin…”

“Man, I just can’t wait until Dalinar finally gets his revenge on…”

“Ten heartbeats? That character? Whaaaaat?”

It’s immensely easy to sink into Roshar, to feel the slow momentum of a diverse world on the edge of utter chaos. As Shallan feels slow goosebumps spread on her arms at a terrifying revelation, so do you. As Dalniar ponders the sociological, political, and ethical impacts on the slow genocide of his enemies, you feel his frustration flushing your cheeks. As Kaladin struggles against his own inner voice, you scream at him to push through, to live.

It’s so easy to give everything to the novel, to concede everything as a reader that epic fantasy asks for. To become invested in the fate of this new world.

But, then, with a sigh, the reviewer sits down to write a review, and that little critical voice in his head is just a little louder, a little more eloquent, than the fanboy.

While everyone agrees that Sanderson is among the best conceptual epic fantasy writers, crafting some of the genre’s most intricate and methodically developed magic systems, opinion on his characterization is split. As a reader who remembers Vin, Kelsier, Sazed, and the other characters from his Mistborn trilogy fondly, I was initially disappointed to find myself somewhat less attached to the three main protagonists of The Way of Kings: Kaladin, Dalinar, and Shallan.

Pinpointing the exact source of this detachment is difficult, but a major contributing factor is that the novel, for all of its pages, as mentioned above, feels more like a prologue to a larger series, an attempt by Sanderson to introduce readers to his world and his characters, without introducing them to the series’ overarching plotline until the very final pages. Even by the 1,000 page mark, it is difficult to recognize how each of the protagonists fits together into the large, puzzle-like plot of the series. Individually, each character struggles with intensely personal challenges, but Epic Fantasy is about the bigger picture, and in The Way of Kings it can sometimes be difficult to see the forest for the trees.

“Kaladin” by Kay Huang

Central to all plot lines in The Way of Kings is the social and civic relationship between the “darkeyes” and the “lighteyes”

Individually, each of the three protagonists is likeable in their own way, and their storylines, each of which crossover only slightly, are intriguing enough that you don’t mind spending so long at their side (notably, each of the three protagonist storylines, if the others were removed, would still be longer than many other novels.) Sanderson’s not subtle in the way he establishes the main characteristics that define Dalinar (patriotism), Kaladin (perseverance), and Shallan (naivety), or, the trait that ties them all together: obsession. By casting the three characters in such different life situations, with vastly different backgrounds, and levels of life experience and world-weariness, Sanderson does an effective, if surface-level, job of exposing readers to the idea that the truth of the world world is changes based on the perceptions of those whose eyes you’re looking through.

Central to all plot lines in The Way of Kings is the social and civic relationship between the “darkeyes” (slaves and poor working class) and the “lighteyes” (privileged nobles) of Alethkar. Presented as a fairly obvious analogue to slavery in post-Revolutionary War America, this exploration of institutionalized racism is present on nearly every page in the novel, used as a mechanism for separating the “good guys” from the “bad guys.” Dalinar is good, for instance, because he treats the darkeyes with slightly more respect than the other lighteyes, despite being viciously racist towards the Parshendi that he fights. Shallan, in all her naive charm, recognizes and acknowledges these issues very rarely, proving her innocence. Kaladin’s very existence and obsessions revolve around a violent past experience with a lighteyed noble, and results in drowning anger towards the noble class.

Add to this, Kaladin is not only a darkeyes, he’s a slave and sold into the Alethi army as a “bridgeman,” a team of humans whose sole purpose in the army is to run enormous, army-bearing bridges ahead of the army’s main forces to enable them to cross the enormous chasms that split the Shattered Plains, a contested zone that has seen war between the Alethi and the mysterious Parshendi. Kaladin is cast in a role that would not be out-of-place in the relentlessly grim work of authors like Joe Abercrombie or Mark Lawrence, but Sanderson’s slightly juvenile writing style is a somewhat uncomfortable partner for Kaladin’s hopeless situation.

However, despite their direct impact all of the novel’s various storylines, Sanderson never graduates past surface-level examinations of these themes. So, while they do a nice job of framing the narrative, and exposing readers to the high level concept that Alethkar is dominated by institutionalized racism, The Way of Kings never achieves the intellectual depth of Ursula K. Le Guin, the satirical elegance of Terry Pratchett, or the raw emotion of Nnedi Okorafor. Those are lofty names to place Sanderson beside, but Sanderson’s taken a big bite of a very serious matter, and if you join a hot dog eating competition, you’re going to be compared to Kobayashi.

Buy The Way of Kings by Brandon Sanderson: Book/eBook

The Way of Kings is very clearly the first chapter of a much larger tale.

One of The Way of Kings‘ greatest oddities, something I’m still contemplating midway through the second novel, is that, despite being 1,200 pages long, there are only four real distinct set pieces in the novel: the Palanaeum (a large library) where Jasnah and Shallan study, the Alethi war camps on the Shattered Plains, the bridgeman camps on the Shattered Plains, and the battlefields of the Shattered Plains. Epic fantasy often finds strength in its ability to offer enormous variety and opportunity to introduce readers to a large number of interesting locations and people. Throughout The Way of Kings, Sanderson hints at many other lands, and briefly exposes readers to these wonderful places in the novel’s various interludes, where they succeed in illustrate that Alethi culture is only one small corner of a diverse and thriving world, but each of the main storylines has a radius of only a few dozen kilometers. Whether this is a flaw or an interesting twist on convention is subjective, but this illustrates some unusual restraint for a novel that otherwise embraces self-indulgence.

The Way of Kings is very clearly the first chapter of a much larger tale. Despite its flaws, The Way of Kings proves that Sanderson has the ambition to fill the hole left after the conclusion of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time, and continue establish himself as one of the most successful and prolific young fantasy novelists. Like many opening volumes before it, The Way of Kings convinces readers that the best is yet to come.

March 31, 2014

“Broader Fantasy Foundations Pt IV: The Tale of Genji, and Building the World of the Shining Prince” by Max Gladstone

A young man of surpassing beauty who rises to a political and romantic career of power and renown mixed with disappointment, betrayal, and demonic possession. Also, he glows.

A minor noblewoman has a tragic love affair with an emperor. She dies, leaving behind her child — a young man of surpassing beauty who rises to a political and romantic career of power and renown mixed with disappointment, betrayal, and demonic possession. Also, he glows.

Welcome to the Tale of Genji, the Japanese story of romance, ghosts, poetry, and politics that has a good claim of being the world’s first novel. To clarify: Genji is a work of prose, not epic poetry, and written in the vernacular rather than the local courtly language (which, in early 11th century Heian Japan, would have been Chinese). It’s also, as far as we can tell, original, without folkloric or legendary precursor. The author, Lady Murusaki Shikibu, wove her hero and his, um, exploits out of whole cloth. And, while many other works deal with mythological high society—gods and demons and so forth—Murusaki seems to have cared a great deal about representing (idealistically but still) her social reality. Genji Monogatari is a work of beauty and passion and (to modern sensibilities) occasional utter weirdness, in which twenty chapters of plot turn on the accidental glimpse of one character by another through a paper screen, astrological prohibitions on travel are used to justify spending the night at a prospective lover’s house, titles take the place of names, violence is anathema, and a twenty-mile exile is worse than death.

Granted, Genji is less core epic fantasy than the tales on which my previous articles on this theme have focused: Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, the Mahabharata, all these are expansive stories of magic, politics, and warfare that could put any doorstopper of your choice to shame. Genji, by contrast, is more contained and elegant. Yet the world it draws is so expansive, so similar to and different from our own at once, that the mind reels to conceive it, making it in a way more alien and fantastical and essential than the million-man wars of the other works.

By that I mean that in the fantasy genre we’re used to the stakes of battle—even those of us who aren’t soldiers have been told, often, that people die in war, it hurts, and ground is gained or lost with blood. This is easy to understand. (Or we so often assume it is, a point for a future essay.) More alien are the wages and risks and glories of love and friendship in different nations at different times. The sword elides cultural diversity; men and women are never more kin than when they face death at an enemy’s hand. It’s in comfort that difference emerges. And the Heian court is… different.

Art by Kekai Kotaki

When Genji Monogatari was written, Japan had been at peace for centuries. The Heian empire was, at this point, not militarized as we understand it, and as a result martial virtue does not seem to have been seen as a component of masculinity. Poets were lionized; swordsmen were regarded as dangerous deviants, and martial bearing and ability were signs of lower-class, if not criminal, status. The capital was a few miles across, but travel from one end to another could take hours due to the poor condition of the roads and the nobility’s reliance on heavy, ceremonially adorned ox-carts. There was an imperial examination system, copied (like much of Imperial tradition) from the Tang dynasty that ruled China a few centuries previously, but nobody seems to have paid it much attention. Corruption was rampant but not vicious. Noble residents of the capital derived their income from massive land holdings, but strived to avoid ever seeming to manage these holdings. The capital city was half-overgrown with vines and fallen into decay; at one point Genji has an assignation with a noblewoman who happens to live in an unfashionable district; she’s presented as if she lived in the most rube-ish of hinterlands, when in fact she’s maybe half a mile distant from his own house. We’re talking about an imperial capital that was once successfully invaded by a bunch of drunken monks from a neighboring mountain. With its lionization of perception, artistic accomplishment, romance, and ennui, the Heian court of Genji Monogatari seems at once alien and familiar—for all the costumes and the astrological prohibitions, the monastic retreats and the ghost possessions, Genji sometimes seems to be set in Hannah Horvath’s Brooklyn.

In form, Genji Monogatari is a chronicle of romance. After the book treats us to the story of the titular Hikaru Genji’s birth and childhood, we meet him as a young court nobleman obsessed with beauty and sadness. Chapter by chapter we receive the chronicle of his romantic adventures—sexy, hilarious, and painful by turns, replete with poetry and details of courtly life and behavior. But Genji’s exploits have consequences, both political (he’s punished with demotion and exile when his less honorable flings are revealed) and, in one of the book’s most haunting subplots, demonic.

You see, in Heian Japan people believed that jealousy and strong emotions could become demons—a soul overcome with jealousy might actually take leave of its body, flow out over the world, and possess or haunt the object of jealousy or longing. While few characters in Genji Monogatari qualify as simple “antagonists”—the novel’s too subtle for that—one constant menace is the Rokujo Lady, who was betrayed by Genji in his youth, and never forgot him. She doesn’t plot revenge like a Child ballad villain. Her soul merely takes leave of her body to make life living hell for Genji and his paramours, two of whom die in the process.

“The Duel” by Jason Scheier

Ghosts and demons and gods are edge cases of Genji’s reality, but they’re not any less real than the people he encounters on a day to day basis.

The best part about this is that the novel never bothers to explain what’s going on. Demonic possession is referred to as such, and ghosts are identified when they appear—but readers are left to deduce the pattern, and its connection to the Rokujo Lady, on their own. These happenings are unexplained, but they’re not treated as explicitly supernatural within the narrative, since we’re talking about a time before Enlightenment nature-supernature distinctions arose. Ghosts and demons and gods are edge cases of Genji’s reality, but they’re not any less real than the people he encounters on a day to day basis.

While the ghosts and the like are a sideline to the Genji Monogatari‘s romantic plots, they’re a great examples of two concepts key to modern fantasy: first, worldbuilding through glimpses, that skill which so distinguishes the fiction of Roger Zelazny, John M. Ford, and Gene Wolfe. People who exist in a fantastical setting and tell stories there don’t bother to call out their setting’s fantasticality; we the readers are left up to our own devices to determine that, to take an example from Wolfe, a destrier isn’t just a big horse, but a big sharp-toothed armorplated horse that hits 60 mph at a gallop.

Sidebar

Notably, the reaction to a hole in one’s world system varies widely even within the modern age. Folks who just live in the modern world system tend to have the Lovecraft reaction to the holes they discover; scientists, though—and philosophers—respond, or should respond, by examining the edges of the hole and trying to peer through. I can think of two great examples of this in modern fantasy: in Elizabeth Bear’s Eternal Sky novels, the wizards of Tsarepeth are presented as scientists and scholars with a near-modern understanding of the spread of disease. When they discover a demon plague that spreads through miasma, they’re initially flummoxed—since they’ve long known miasma theory to be false. Facts force them to revise their theory, in proper fashion. The Myth of the Man-Mother in Pat Rothfuss’s The Wise Man’s Fear is another example, played for humor—hyper-rational Kvothe fails to convince a friend of his that men have any role in the conception of children, since his arguments all devolve to an appeal to authority. The best part about this: it’s entirely possible that pregnancy just works differently in the Four Corners universe—or works differently among different peoples there.1

The second concept is that the fantastical does not seem fantastical to locals. Genji’s reaction to a ghost, or to a demonic possession, is not the Lovecraftian narrator’s “THAT IS UNPOSSIBLE” followed by a prolonged paragraph on circles of firelight, mad dancing beyond the edges of reality, etc., so much as “HOLY SHIT, GHOST!” He—and the other people in his world—are afraid of ghosts because they are dangerous and terrifying, not because they represent a hole in a world system that does not incorporate them.

Don’t come to The Tale of Genji for swordfights and magical struggles with ancient evil, but if your taste runs to the subtle—if you’re fascinated by court politics, by love and loss, prophecy and dream, ghosts and spirits and duels of poetry—if the court chapters of Tigana were your particular poison—then do yourself a favor. Find a copy of Genji, and on an appropriately rainy day, sit down to read.

Destroying Fantasy Special Edition

The Tale of Genji has a very strong claim to the title of “world’s first novel.” It was written by a woman, in the vernacular of her time, while contemporary “high art” tended to be written in Chinese. It was distributed one chapter at a time, and historically each page has featured a detailed illustration, with dialogue bubbles. Oh, and since all this is happening before “industry” as commonly conceived, she’s basically self-publishing this book.

Meanwhile, contemporary Northern Europe was basically full of Vikings and fire.2

Finding Genji

We’re blessed in having an excellent current translation by Royall Tyler. Tyler’s language is beautiful, and / but he preserves an aspect of the original language that some might find confusing: its tendency to refer to key figures by title or by some significant detail rather than by name (think “the Breaker of Horses” rather than “Hector”). In fact, most characters are never referred to by name, and their appellations change over time as they move, gain new titles, and fall in and out of love. Tyler, thankfully, includes a short introduction to each chapter listing the most common appellations for the characters. If you find yourself struggling still, take heart: earlier translations, while still good, tend to gloss over this allusive element of the text and just refer to everyone by their critically-determined name all the time.

As for adaptations, those are harder to track down, partly due to the enormous and discursive nature of the novel: adapting it would be like adapting Proust. (Also, while the book is hardly Jin Ping Mei, the centrality of sex to the plot means that it’s easy for adaptations to, well, “descend” is editorializing a bit, but let’s just say they can veer in a porny direction.) If you’re interested in a shorter introduction to Heian Japan, though, so you can hit the ground running, may I recommend:

The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon — Everyone should read this at least once in their life. A Pillow Book was a diary kept under the pillow, for recording random thoughts—as often lists or snatches of poetry or ruminations on a theme as tales of daily life. Basically, this is the Tumblr of a noblewoman from 10th century Japan, complete with reaction gifs, and it is AMAZING. What are you still doing here? Go read!

The Diary of Lady Murasaki — This is the diary of Genji Monogatari‘s author, or at least appears to be; some scholarship was inconclusive on this point when last I checked. It’s more narrative than the Pillow Book, which is both good and bad—you get more of a sense of what people were doing in this world, but reading the Diary, I miss Sei’s lists and antics.

Buy The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu: Book/eBook

The World of the Shining Prince — Ivan Morris, gifted and brilliant scholar and translator, realized some of his students were bouncing off Genji Monogatari like a wren off Neal Stephenson’s patio door, and so wrote this detailed introduction to the world and its customs. This book is basically a statblockless sourcebook for roleplaying in Heian Japan, exhaustively researched and carefully developed. It’s mid-century scholarship, so watch out for various pitfalls and essentialist assumptions—but it’s good mid-century scholarship, so there aren’t many.

NB: This sidebar was inspired heavily by Rothfuss’s Guest of Honor speech at Vericon, of which I wish I had a recording—he spun an audience question into a great ten minute riff on science, epistemology, and worldbuilding along these lines.

Yes, my medievalist friends, I know there was more going on in the late 10th and early 11th centuries than Vikings and fire. But come on. Murasaki wrote The Tale of Genji when Western poets and illuminators were writing the first version of the Song of Roland and composing the Domesday Book. Both of which are awesome. But still.

March 28, 2014

Speculative Fiction 2014 editors announced

With the release of Speculative Fiction 2013 looming, editors Ana Grilo and Thea James have announced the duo responsible for assembling the 2014 volume of the non-fiction essay collection: Renay and Shaun Duke. Excellent choices, if I do say.

One of the major components to the SpecFic collection series, as originally envisioned by creators Justin Landon and Jared Shurin, was to ensure a fresh take on online SFF conversation by featuring rotating editors every year. Renay and Duke mark the third pair of editors to work on the series. Grilo and James feel that their unique backgrounds offer a compelling opportunity for the series. “We strongly believe that Renay and Shaun’s different backgrounds – fandom and academia – can make for a really interesting editorial dynamic,” they said in the announcement.

Renay has been writing SF and fantasy fan fiction, criticism, and commentary since the early 1990s. She serves as staff within the Organization for Transformative Works, co-edits a media criticism blog, Lady Business, and writes columns for speculative fiction magazine Strange Horizons.

Shaun Duke is an SF/F writer, a critic, and a PhD. student at the University of Florida studying science fiction, Caribbean literature, and postcolonialism. He currently blogs at The World in the Satin Bag, and is a host on The Skiffy and Fanty Show, an SF/F podcast which is currently running its World SF Tour.

“We selected Renay and Shaun as editors for several reasons that go beyond their awesome bios,” said The Book Smugglers, editors of the 2013 volume. “Namely, we admire their writing and the thoughtful ways that they engage with the speculative fiction community. We’ve been following Renay’s online endeavors for years and it’s safe to say that she’s been an incredible source of inspiration for The Book Smugglers and the way we engage in criticism. Similarly, Shaun never fails to impress us with his thoughtful, well-researched and articulate take on SFF books, films, and his contributions to important SFF community discussions.”

March 27, 2014

These Game of Thrones portraits by Olly Moss are too adorable (*Spoilers*)

Has death and destruction ever been so cherubic? These men of Westeros are another reason that I think Olly Moss deserves a spot on this year’s Hugo ballot.

Olly Moss is an English artist known for his inventive re-imaginings of famous movie posters, and his involvement with Campo Santo, a videogame development studio whose first game, Firewatch, was recently announced.

March 26, 2014

In the Grim Darkness of the Far Future, there is only… The Goblin Emperor

Once upon a time there was a book. In the first twenty pages it had like a bajillion names, several dozen instances of archaic speech patterns, and quite a bit of moping. I was instantly willing to hate it. But, because I’m a true critic of the arts, I continued. Also, because I can’t really beat a book up unless I finish it, right? I admit to doing this on occasion. However, as I continued to read Katherine Addison’s The Goblin Emperor, I became enthralled. What was off-putting became second nature and beneath it was revealed a gorgeous narrative, a lush world, and dozens of fascinating characters. While there remains an absurd indulgence in complicated naming mechanisms, Addison’s fantasy novel rates among the best I’ve read.

Katherine Addison is a genius

Every book has a story, and The Goblin Emperor‘s begins long before it was published. Katherine Addison is actually Sarah Monette, a critically acclaimed author of four novels for Ace Books. Unfortunately, those books didn’t sell very well. The Goblin Emperor was submitted to Ace and rejected, forcing Monette to shop the project elsewhere. Purchased by the Jim Frankel (who has had some problems subsequently) at Tor, the novel found a home. Monette became Katherine Addison because bookstores aren’t big fans of authors who don’t sell real well, but are easily mollified with byline changes. I mention this because I have no idea whether Monette can write her way out of a paper bag, but Katherine Addison is a genius and Ace should be totally bummed they didn’t buy The Goblin Emperor.

As for the story in the novel, well, that’s something else entirely. Maia is the youngest son to the Emperor of the Elflands. His dad hates him because Maia’s mom, the former Empress, was a goblin. Their marriage was for political expedience and she was quickly put aside for a more appropriate elf bride. With his mom dead for many years, Maia has been repeatedly abused by his guardian for a decade. After all, what are the odds the Emperor and his three sons would all die and leave a half-breed screw-up in charge?

But, because Addison has a novel to write, that’s exactly what happens. When the Emperor and his three sons are killed in an airship accident, Maia finds himself on the throne. Lacking any knowledge of court politics or decorum, friendless and scared, he has to discover how to run an Empire on his own, survive the intrigue that may have killed his estranged family, and escape his father’s shadow.

He’s scared and desperately in need of a friend, but then… the Emperor can’t have friends. Can he?

Admittedly, the plot isn’t going to bowl anyone over with its intricacies. Things progress more or less as they are wont to do in these kinds of situations, with a few pleasant twists. But, as all know, novels rarely stand out for their plots. The Goblin Emperor excels for two reasons. One, the prose is pretty brilliant and the characters are, for lack of a more descriptive term, incredible. It begins with Maia, the novel’s sole point of view character. For a modern fantasy protagonist, Maia is astonishingly nice, and well mannered, and genuine. He didn’t aspire to be Emperor and somewhat resents the restrictions the office has placed on him. He’s scared and desperately in need of a friend, but then… the Emperor can’t have friends. Can he?

It might seem odd to make a note of Maia’s disposition as though it’s something unique, but isn’t it? How often are we treated to a protagonist who’s actually just a good person? While we are always given heroes, don’t they also often come across as self interested and glory hungry and violent? The protagonist who does heroic things by resisting those very impulses seems exceedingly rare to me. More rare is an author capable of maintaining interest without relying on them. Instead, Addison trades in feelings, and emotion, and soul.

His mother had been the world to him, and although she had done her best to prepare him, he had been too young to fully understand what death meant–until she was gone, and the great, raw, gaping hole in his heart could not be patched or mended. He looked for her everywhere, even after he had been shown her body–looked and looked and she could not be found.

Buy The Goblin Emperor by Katharine Addison: Book/eBook

All around Maia, and his struggle to stay afloat, are a host of side characters. His guards whose lives are bonded to his, his secretary who only wants Maia to succeed, a Chancellor who loved the last Emperor and is loathe to see his policies corrupted, a former-Empress who wants nothing more than to hold on to the power she lost when her husband died, and dozens of others, all of whom seem compelling and alive in Addison’s hands. They orbit around the narrator, but possess narratives of their own that interweave into a tapestry that pulses on the page.

Give it patience and I dare you to not to fall in love with Maia’s reign as The Goblin Emperor.

It is rare to find a novel in today’s market that will resonate with such a hopeful tone. The Goblin Emperor is the antithesis of the grimdark movement. It is uplifting and hopeful and full of joy without being reliant on the kinds of serotonin inducing nostalgia that genre so often falls back on. Give it patience and I dare you to not to fall in love with Maia’s reign as The Goblin Emperor.

March 24, 2014

“The Strange, the Lovely, and the Queer” by David Edison

I would see queer romance in a different, more nuanced light, complete with a historical perspective that both undercut Card’s work and crystallized the notion of real-world men who loved each other with their bodies as well as their minds.

Hello A Dribble of Ink! I am David Edison, author of The Waking Engine and editor of GayGamer.net, and I am dribbling my ink all over you. Aidan has asked me to talk about my experiences with inclusivity in the gaming world, which is a great chance to look at the differences and similarities with the equivalent challenge in the world of speculative fiction. I’ll apologize in advance for being unscholarly and scatterbrained: these are, of course, sprawling and complex dynamics, and a genuine analysis is beyond both the scope of a blog post and the capabilities of yours truly.

Let’s start with the idea of finding yourself reflected in the creative works you consume. From my personal experience: I encountered a representation of my own queerness in speculative fiction well before I encountered it anywhere else in our culture, especially games. Orson Scott Card’s Songmaster hit me like a ton of bricks at nine, maybe ten years of age. (There is irony to be found there, of course, which is its own post, methinks.) The pedophilia went right over my young head (paging Alanis Morissette and her 10,000 not-actually-ironic spoons, and yet another blog post), but what mattered to me then, as now, was the love. Only a few years later, when I read Mary Renault’s stunning historical novels like Fire from Heaven, The Mask of Apollo, and The Persian Boy, I would see queer romance in a different, more nuanced light, complete with a historical perspective that both undercut Card’s work and crystallized the notion of real-world men who loved each other with their bodies as well as their minds.

For a young queer man, especially a reader, discovering multiple sources of my own nature (which I had realized at a much younger age than 9 years old, though I did not have the words for it) was a lifeline: suddenly I was a part of the world. Moreover, I could decide between different representations of myself and begin building an identity in concert with reality, rather than wondering if perhaps, to my horror, I might be the only one.

Then came Mercedes Lackey, and Ellen Kushner, and Richard Bowes, and my one true lifesaver, Storm Constantine, whose Wraeththu trilogy did far more than represent my sexual identity: it handed me the keys to writing my own entry into this strange, lovely, queer canon.

Meanwhile, at the very same ages, I was rescuing Princess Peach from Bowser’s castle. Aside from Samus Aran’s hair-flip in Metroid, there was very little representation of anything remotely feminist, queer, or nonwhite in that video game life. This disparity between book and game would become the reason I sought to help create a space in the gaming world for queer men, and GayGamer.net is the result of the frustration a generation of young queer men felt at their invisibility within the medium they loved.

“We do not want “Grand Theft Auto: Fabulous,” I say here, “We only want the opportunity to be ourselves while playing Grand Theft Auto.”

Not for nothing did I end up on MTV News, a hundred million years ago, asking to see myself represented in the games I loved in the same (small, very small) way I had found myself in speculative fiction. “We do not want “Grand Theft Auto: Fabulous,” I say here, “We only want the opportunity to be ourselves while playing Grand Theft Auto.”

Did Sam Houser, head of Rockstar Games, see that clip? Yes. Did my entreaty have anything to do with the release, several years later, of Grand Theft Auto: The Ballad of Gay Tony? Unlikely—Rockstar has made a fortune pushing the boundaries. That said, it didn’t hurt: not because I am anything particularly special, but because I made myself visible. You can’t achieve equality if you are unseen, unheard, unnoticed. You must stand up and ask for what you want.

In the modern speculative fiction world, we have luminaries like Samuel R. Delany, who have been visibly queer and nonwhite since video games were little more than Pong. We have Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward, who literally wrote the book on writing the inclusive book. Their sensitive, insightful, instructive missive, Writing the Other, was given to me by mentors who think it mightily important that writers learn how to include a diversity of characters in their work. This is something that many spec-fic writers think is crucial to understand before we try to broaden the inclusivity of our genres, which is something we already want to do.

Not so, in video games. Not only was there an absence of queer representation in the medium, but there was a thoughtless lack of understanding (from both game devs and gamers) of why we would want to see ourselves in games, period. I spent most of 2006 explaining that while Mario and Duke Nuke’em were great, queers and women and people of color were not, in fact, satisfied with being nearly invisible in the industry to which they dedicated their time and dollars.

Yes, video games have always had their advocates. Brenda Romero, whose excellent book Sex In Video Games did wonders to further certain conversations, remains a strong voice for inclusive-thinking in games. Ditto Ian Bogost, Leigh Alexander, Mattie Brice, and many more. But the facts on the ground for the video game industry remain bleak: the developer demographic skews strongly toward white men, mostly straight, and when you go to a video game convention, you will see that lack of diversity on the creator side quite starkly. On the consumer side? Women and people of color and queers are as present-and-voting as we are in the rest of society! The demographic who creates games lacks diversity, and this translates directly to a lack of diversity in the medium, despite the obvious diversity of gamers ourselves.

Buy The Waking Engine by David Edison: Book/eBook

This has begun to change, painfully slowly. People of color and women are half of the playable characters in the Left 4 Dead series, and The Last of Us tells the story of a tautly-wound father-daughter relationship and features some queer representation. Left 4 Dead 2 has a female woman of color as a player-character, which made me happier than I can say.

The bottom line, however, is that neither industry is doing this well enough. Video games need more advocacy and, frankly, a hiring revolution. Speculative fiction needs to continue its good work, and we need more books written by women and people of color, reviewed-by, celebrated-by. We may have centuries of inclusivity behind us (hello, Mary freaking Shelley), but both books and games stand in a similar position in our current era of rapidly-evolving social justice: we can, and must, do better. Much better.

The differences between the two media are vast, and beyond the scope of this rambling post, but and of course the two industries are not the same. And yet, in so many ways that matter to so many less-visible people, we are.